Abstract

Various genetic conditions produce dysfunctional osteoclasts resulting in osteopetrosis or osteosclerosis. These include human pycnodysostosis, an autosomal recessive syndrome caused by cathepsin K mutation, cathepsin K-deficient mice, and mitf mutant rodent strains. Cathepsin K is a highly expressed cysteine protease in osteoclasts that plays an essential role in the degradation of protein components of bone matrix. Cathepsin K also is expressed in a significant fraction of human breast cancers where it could contribute to tumor invasiveness. Mitf is a member of a helix–loop–helix transcription factor subfamily, which contains the potential dimerization partners TFE3, TFEB, and TFEC. In mice, dominant negative, but not recessive, mutations of mitf, produce osteopetrosis, suggesting a functional requirement for other family members. Mitf also has been found—and TFE3 has been suggested—to modulate age-dependent changes in osteoclast function. This study identifies cathepsin K as a transcriptional target of Mitf and TFE3 via three consensus elements in the cathepsin K promoter. Additionally, cathepsin K mRNA and protein were found to be deficient in mitf mutant osteoclasts, and overexpression of wild-type Mitf dramatically up-regulated expression of endogenous cathepsin K in cultured human osteoclasts. Cathepsin K promoter activity was disrupted by dominant negative, but not recessive, mouse alleles of mitf in a pattern that closely matches their osteopetrotic phenotypes. This relationship between cathepsin K and the Mitf family helps explain the phenotypic overlap of their corresponding deficiencies in pycnodysostosis and osteopetrosis and identifies likely regulators of cathepsin K expression in bone homeostasis and human malignancy.

Bone resorption is a pivotal process for normal growth and homeostasis and is defective in a variety of human diseases including osteoporosis and osteopetrosis. Bone resorbing osteoclasts are multinucleated hematopoietic cells with abundant mitochondria and ruffled borders, which resorb calcified bone through resorption pits (Howship's lacunae) (1, 2). Osteoblastic stromal cells are involved in bone formation and can regulate osteoclast function. Defects in osteoclast function resulting in osteopetrosis have been described in several mitf mutant rodent strains (3–5). The Mitfmi/mi mouse was described in the 1940s and contains a mutation, now known to affect a basic/helix–loop–helix/leucine-zipper transcription factor, resulting in severe osteopetrosis (marble bone disease), absence of neural crest-derived pigment cells, and mast cell defects (6). Mitf subsequently was found to belong to a family of transcription factors, which includes Mitf, TFE3, TFEB, and TFEC. All members of this Mitf family of transcription factors are capable of forming homodimers or heterodimers and bind an E-box consensus sequence CA[C/T]GTG (7–9). Both Mitf and TFE3 are abundantly expressed in osteoclasts (5) and have been linked to changes in osteoclast function with age (5, 10, 11).

There is a phenotypic similarity between microphthalmia Mitfmi/mi mutant mice and cathepsin K null mice (12, 13) as well as the human disease pycnodysostosis caused by cathepsin K deficiency (14). Cathepsin K is a cysteine protease from the papain family of proteases and plays an important role in osteoclast function (14). This enzyme has been shown to cleave a number of bone matrix proteins including collagen type I, II, and osteonectin. Both the Mitfmi/mi and cathepsin K mutant mice develop osteopetrosis due to defective osteoclasts. Osteoclasts derived from the Mitfmi/mi mutant mice are primarily mononuclear, do not form ruffled borders, and resorb bone poorly (3, 4, 15). In addition, they contain decreased levels of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) consistent with the finding that Mitf regulates TRAP expression in osteoclasts (16). Osteoclasts from cathepsin K mutant mice are multinucleated and can demineralize bone, but cannot degrade the protein matrix of bone. These osteoclasts contain abnormal cytoplasmic vacuoles filled with bone collagen fibrils, and whereas the resorption pit area is larger compared with wild type, these pits are much more shallow (12–14). Pycnodysostosis is a human disease caused by congenital cathepsin K deficiency (14). The characteristic features of pycnodysostosis are short stature and skeletal abnormalities such as unclosed cranial sutures, apoplastic mandible, and double rows of teeth. Pycnodysostotic osteoclasts are able to demineralize bone but cannot degrade the organic matrix. Their morphology is similar to the osteoclasts from murine cathepsin K null animals. Although once thought to reside exclusively in osteoclasts, cathepsin K expression has been discovered in a significant fraction of human breast cancers (17). Cathepsin K is an attractive potential target for the treatment of osteoporosis and also could play a role in breast cancer invasiveness. Studies of cathepsin K inhibitors are thus underway as therapeutic agents.

Cathepsin K mRNA and protein have not been characterized in the Mitfmi/mi mouse. This study identifies cathepsin K as a target of the Mitf transcription factor family. Cathepsin K protein and mRNA levels are decreased in Mitfmi/mi mouse osteoclasts. The cathepsin K promoter contains four E-boxes, putative Mitf binding sites, three of which respond to the Mitf family in transactivation assays. Electrophoretic mobility-shift studies show that the same three sites are bound by Mitf derived from osteoclast nuclear extracts. Osteopetrotic mouse mitf alleles [mitf oakridge (mitfor) and mitf microphthalmia (mitfmi delR217) (8, 9)] disrupt cathepsin K promoter activity in the presence of wild-type Mitf or TFE3 whereas the nonosteopetrotic recessive allele mitf cloudy eyes (mitfce) (8, 9) does not interfere with wild-type Mitf function, thus recapitulating a key genetic feature of Mitf-dependent osteopetrosis. This study also shows that endogenous cathepsin K mRNA levels are up-regulated upon overexpression of Mitf in primary human osteoclasts and thus identifies cathepsin K as a transcriptional target of the Mitf transcription factor family.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Cell Lines.

C57BL/6J mice ages 6–8 weeks and heterozygous +/Mitf (B6C3Fe-a/a-mitfmi) breeding pairs were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories. MCF-7 (American Type Culture Collection) and ST2 (Riken Cell Bank, Tsukuba, Japan) cells were grown in DMEM/10% FBS supplemented with 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Mouse Osteoclasts.

Mouse spleen cells were cultured in MEM (Cellgro, Herndon, VA)/10% FBS (HyClone), 100 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (R & D Systems), 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin, and varying receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) concentrations. Cells were refed with RANKL containing media every 3 days. At day 8–10 the cells were stained for TRAP (Sigma).

Human Osteoclasts.

Human osteoclasts were cultured as described (18). Normal adult human bone marrow cells isolated by Ficoll-Paque (Amersham Pharmacia) were plated at 1 × 106 cells/ml in 6-well plates in MEM (Cellgro), 20% horse serum (HyClone), 10−8 M vitamin D (generous gift of M. Uskokovic, Hoffman-LaRoche, Nutley, NJ). Cells were refed by replacing half of the media every 7 days. At day 14, half of the culture media was replaced with MEM, 20% horse serum, 10−8 M vitamin D, and 50 ng/ml recombinant M-CSF (R & D Systems) and refed with this medium every 3 days.

Human Osteoclast Nuclear Extract.

Day 21 human osteoclasts (one 6-well plate) were extracted in 400 μl of ice-cold buffer A (10 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.9/1.5 mM MgCl2/10 mM KCl/0.5 mM DTT/2 mM PMSF/20 mM sodium pyrophosphate/10 mM NaF/1 mM Na3VO4), incubated on ice for 10 min, vortexed 10 s, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 s. The pellet was extracted in 60 μl of ice-cold buffer C (20 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.9/25% glycerol/420 mM NaCl/1.5 mM MgCl2/0.2 mM EDTA/0.5 mM DTT/2 mM PMSF/20 mM sodium pyrophosphate/10 mM NaF/1 mM Na3VO4). After a 20-min incubation, the nuclear extract was vortexed for 15 s and spun at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 2 min, and the supernatant was stored at −80°C.

Gel-Shift Assay.

Probes/competitor double-stranded oligonucleotides were 23–25 bp and spanned the individual E-boxes with wild-type or double point mutations as indicated in Fig. 2B. Probes were labeled by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs), and binding reactions (20 μl) contained 50,000 cpm labeled probe, 0.1 μg poly (dI-dC) (Amersham Pharmacia), 5% glycerol, 0.1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 0.2 mM DTT, 3 μl human osteoclast nuclear extract, and 5 μl D5 anti-human Mitf mAb culture supernatant (19). Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and resolved on 6% polyacrylamide TBE (45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA) nondenaturing gels. For competition studies, 10 and 50 molar excess of unlabeled wild-type or mutant probes were included in the binding reaction.

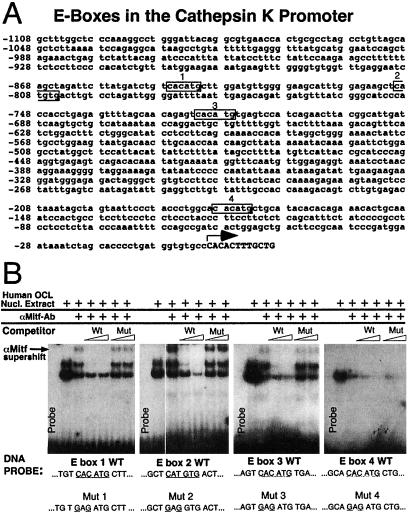

Figure 2.

(A) The cathepsin K promoter contains four potential Mitf-binding E-boxes. Four CA[C/T]GTG E-box elements in the human cathepsin K promoter fragment −928 bp to +2 bp (25, 26) used in this study are indicated in black boxes and numbered 1–4. The transcription start site is indicated by an arrow and capital letters. (B) Sequence-specific recognition of three E-boxes by Mitf. DNA fragments spanning each of the four E-boxes in the human cathepsin K promoter were used as probes for electrophoretic mobility-shift assay. Human osteoclast nuclear extract was used as a source of the Mitf protein. Anti-Mitf mAb D5 was added (as indicated by arrow) to supershift Mitf specific protein:DNA complexes. Specificity of binding was determined by cold competition using titrations (10- and 50-fold molar excess) of unlabeled wild type (Wt) or double point mutant (Mut) probes as indicated (sequences are listed at the bottom). Selective loss of the supershifted Mitf complex by wild type, but not mutant, competitors suggests specific recognition of E-boxes 1, 2, and 3, whereas no specific supershift was seen for E-box 4.

Cathepsin K Promoter Luciferase Constructs.

The cathepsin K promoter −928 to +2 bp was amplified from human genomic DNA by using PCR and the following primers: 5′ primer, CGGGGTACCCCGTCTCCTTCCCCACATCTGTTTATGG; 3′ primer, CTTCTAGAAGCAGCAAAGTGTGGGCACACCATCAG, cloned into a pCR-blunt vector by using a Zero-Blunt Cloning Kit (Invitrogen), retrieved by using KpnI and BglII, and cloned into the pGL2.basic luciferase vector (Promega). Point mutations in the cathepsin K promoter were made by PCR, incorporating the same double mutants as in the binding studies (see Fig. 2B). Deletion of E-boxes 1–3 in the Cathepsin K promoter (del1–3.luc) was performed by HindIII cleavage of the full-length, wild-type promoter fragment, followed by Klenow treatment, KpnI cleavage, and ligation into pGL2.basic.

Transfections.

Transfection experiments were performed in MCF-7 cells by using Lipofectamine/Plus reagent (GIBCO/BRL) (see Fig. 3). Individual wells of a 24-well plate (1 × 104 cells) received 0.1 μg cathepsin K promoter, 0.1 μg sea pansey luciferase plasmid (Promega), and 0.7 μg Mitf.pEBB expression vector (19), TFE3.pSV2A (20), or vector controls. Cells were harvested after 24 h of transfection in 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase assays were read in a Monolight 2010 luminometer (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory, San Diego) by using Luciferase assay reagent II and Stop & Glo (Promega). Luciferase values were normalized to sea pansey luciferase in each well. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data from three separate experiments were used. Transfection was performed in MCF-7 cells by using Lipofectamine/Plus (GIBCO/BRL) or Fugene 6 transfection reagents (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions (see Fig. 5). Individual wells in a 24-well plate received 0.1 μg cathepsin K promoter, 0.1 μg sea pansey luciferase plasmid, and 0.7 μg pCDNA3 vector control or Mitf.pCDNA3 expression vectors: wild-type Mitf.pCDNA3, Mitfor.pCDNA3, Mitfmi delR217.pCDNA3, or Mitfce.pCDNA3 (see Fig. 5A). Individual wells in a 24-well plate received 0.1 μg cathepsin K promoter, 0.1 μg sea pansey luciferase plasmid, and 0.7 μg pCDNA3 vector control or wild-type Mitf.pCDNA3 expression vector (see Fig. 5B) or TFE3.pSV2A (see Fig. 5C). Where indicated, 0.2 μg of Mitfor.pCDNA3, Mitfmi delR217.pCDNA3, Mitfce.pCDNA3, or empty pCDNA3 vector was added. All Mitf constructs in pCDNA3 vectors were subcloned from in vitro expression vectors (8). Cells were harvested after 24 h of transfection in 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase assays were read in a Microplate Luminometer LB 96V (MicroLumat Plus, EG&G Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany) by using Luciferase assay reagent II and Stop & Glo (Promega). Experiments were performed in triplicate, and luciferase values were normalized to sea pansey luciferase in each well. The data (see Fig. 5 B and C) are presented as % wild-type Mitf or TFE3 activity on the human cathepsin K promoter after subtracting vector only control. The statistical analysis was performed by using statview (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with an unpaired t test.

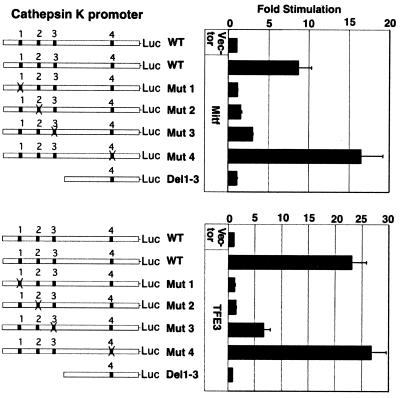

Figure 3.

Transactivation of cathepsin K promoter constructs by Mitf and TFE3. The wild-type (WT) human cathepsin K promoter −928 bp to +2 (25, 26), mutant cathepsin K constructs with individual E-boxes mutated, and a deletion construct without the upstream three E-boxes were transfected into MCF-7 cells in the presence of Mitf, TFE3, or vector controls. The data are combined from three separate transfection experiments each performed in triplicates with bars indicating standard errors.

Figure 5.

(A) The wild-type (wt) Mitf protein up-regulates the human cathepsin K promoter whereas Mitfmi, Mitfor, or Mitfce mutant proteins have no significant transactivation activity. The wild-type human cathepsin K promoter −928 bp to +2 luciferase reporter was transfected into MCF-7 cells in the presence of wild-type Mitf, Mitfor, Mitfmi, Mitfce, or a vector control. The transfections were performed in triplicate with bars indicating standard errors. (B and C) Mitf mutants, Mitfor, and Mitfmi, which cause osteopetrosis in animal models, decrease the ability of wild-type Mitf (B) and TFE3 (C) to transactivate the cathepsin K promoter. The wild-type human cathepsin K promoter −928 bp to +2 luciferase reporter was transfected into MCF-7 cells in the presence of wild-type Mitf (B) or TFE3 (C) plus mutant Mitf (Mitfor, Mitfmi, or Mitfce), or vector controls. The transfections were performed in triplicate with bars indicating standard errors. The data are presented as % wild-type Mitf or TFE3 activity on the human cathepsin K promoter after subtracting vector only control. * indicates statistically significant repression of wild-type Mitf or TFE3 function by mutant Mitfor and Mitfmi (P < 0.04), whereas the nonosteopetrotic allele Mitfce did not affect wild-type Mitf and TFE3 activities.

RANKL Bacterial Expression and Purification.

Mouse RANKL DNA (coding for extracellular region D76-D316 (21–23) was reverse transcription–PCR-amplified by using RNA from the ST2 osteoblast cell line (NdeI-containing primers: 5′ mouse RANKL primer, 5′-CTGGAATTCCATATGGATCCTAACAGAATATCAGAAGAC; 3′ mouse RANKL primer, 5′-CGTCTAGACCATATGTCAGTCTATGTCCTGAACTTTGAAAG) followed by blunt cloning into pCR-blunt vector (Invitrogen), NdeI restriction, and ligation into NdeI-cleaved pET-15b, followed by expression in Gold BL21(DE3)pLys-competent bacteria (Stratagene). Recombinant His-tagged RANKL was prepared by native lysis, Ni-chelate chromatography (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and elution in imidazole. RANKL was used in osteoclast cultures at 100–200 ng/ml media (determined empirically for each recombinant preparation, based on optimizing formation of TRAP-positive murine osteoclasts in splenocyte cultures).

Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting.

Total protein from day 10 osteoclast cultures of wild-type or Mitfmi/mi osteoclasts was subjected to Western blotting with anticathepsin K (SmithKline Beecham) and antitubulin (Sigma) antibody. Samples were applied to 12% SDS/PAGE gels and run at 30 mA/gel. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose, blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS/Tween 20 (PBST), and probed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to mouse cathepsin K (1:1,000) in PBST containing 0.1% BSA for 2 h. The membrane was washed three times for 15 min with PBST, probed with a secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (ICN), washed three times for 15 min in PBST, and developed by ECL (Amersham Pharmacia). A separate membrane processed under identical conditions was probed with mouse antitubulin primary antibody (Sigma) and goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (ICN) as described (5).

Adenoviral Infection of Human Osteoclasts.

Human osteoclasts [day 11 of culture (see Fig. 4A) or days 11 and 14 (see Fig. 4B)] were washed with PBS and infected with E1A- and E1B-deleted adenovirus type 5 expressing either wild-type Mitf, mutant Mitfmi (delR217), or green fluorescent protein (GFP) (control) (24) in serum-free MEM media supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2 for 30 min at 3.75 × 10−4 OD260 units/cell of cesium chloride gradient purified virus. After the incubation, the media were replaced with MEM, 20% horse serum, and 10−8 M vitamin D, and infected cells were harvested at 46 or 67 h after infection. Total RNA was isolated by using the Trizol reagent (GIBCO/BRL). Samples for Western blot were harvested in an SDS/DTT lysis buffer and subjected to Western blotting with anti-Mitf mAb (C5) as described (5).

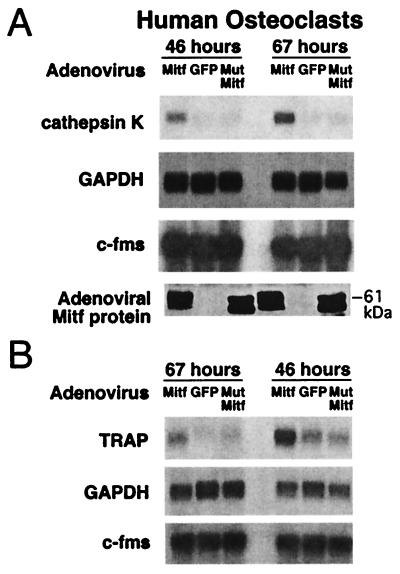

Figure 4.

(A) Mitf regulates endogenous cathepsin K mRNA expression in human osteoclasts. Primary human osteoclasts cultured from bone marrow were infected at day 11 with adenoviruses encoding wild-type Mitf, GFP, and mutant Mitf followed by harvesting total RNA after 46 and 67 h. Northern blots were probed for cathepsin K, GAPDH, and c-fms. Comparable overexpression of wild-type and mutant Mitf proteins was verified by Western blot (Bottom) with anti-Mitf antibody. (B) TRAP mRNA levels also increase upon overexpression of wild-type Mitf. Day 14 and day 11 primary human osteoclasts were infected with adenoviruses encoding wild-type Mitf, GFP, and mutant Mitf followed by harvesting total RNA after 67 and 46 h, respectively.

RNA Preparation and Northern Blots.

Total RNA was isolated from human osteoclasts by using the Trizol reagent (GIBCO/BRL). Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from wild-type and Mitfmi/mi day 10 mouse osteoclasts by using the QuickPrep Micro mRNA Purification Kit (Amersham Pharmacia). A total of 2.3 μg RNA or 0.8 μg poly(A)+ RNA (per lane) then was resolved by Northern gel/blotting by using a 1% agarose gel, Hybond-N membrane (Amersham Pharmacia), and crosslinked in the GS Gene Linker (Bio-Rad). Probes were prepared with the Prime-It Random Primer Labeling Kit (Stratagene) by using reverse transcription–PCR-derived cDNA fragments (from mouse or human osteoclast mRNA) for the human cathepsin K, mouse cathepsin K, mouse RANK, human and mouse c-fms, human TRAP, and mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) genes (primer sequences for probe construction are available as supplemental Materials and Methods on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). Probe for human GAPDH was prepared by a restriction digestion of the full-length GAPDH cDNA.

Results and Discussion

Cathepsin K mRNA and Protein Levels Are Decreased in Mitfmi/mi Osteoclasts.

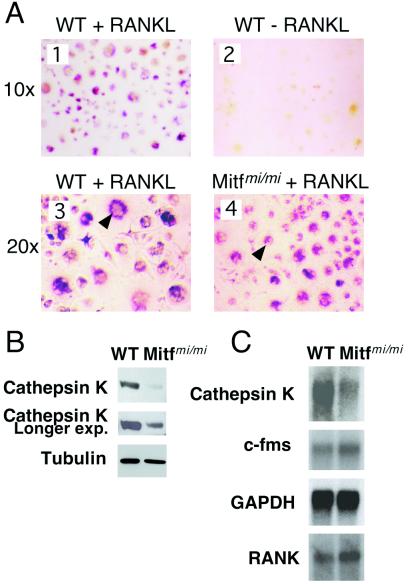

To examine cathepsin K expression in the setting of Mitf mutation, murine osteoclasts were prepared from primary cultures of splenocytes derived from wild-type or osteopetrotic Mitfmi/mi mice. TRAP-positive osteoclasts were generated from spleen cells grown for 9 days in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL, but not when RANKL was excluded from culture medium (Fig. 1A 1 and 2). Although Mitfmi/mi osteoclasts display a fusion defect and fail to form bone resorption pits (4), TRAP-positive osteoclasts could be generated from Mitfmi/mi splenocytes (Fig. 1A 3 and 4). TRAP staining was typically somewhat weaker in younger (day 7) Mitfmi/mi osteoclasts (data not shown), consistent with evidence that TRAP is a transcriptional target gene of Mitf (16), and some bi- or tri-nucleated cells were observed by day 9. Both wild-type and Mitfmi/mi osteoclasts expressed osteoclastic factors such as the M-CSF receptor c-fms, and the RANKL receptor (RANK) as assessed by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1C). However, the Mitfmi/mi osteoclasts expressed significantly less cathepsin K protein (Fig. 1B) and cathepsin K mRNA (Fig. 1C) than wild type, consistent with the possibility that this gene might serve as a transcriptional target of Mitf. The decrease in cathepsin K protein levels by Western blotting is comparable to the decrease of cathepsin K mRNA on Northern blot (see Fig. 1B, longer exposure). Of note, cathepsin K protein and mRNA were not entirely absent in the Mitfmi/mi osteoclasts (Fig. 1 B and C), suggesting the possibility that factors other than Mitf (such as other Mitf family members) are likely to contribute to regulation of its expression. This observation, while suggestive of a connection between Mitf and cathepsin K expression, does not address the directness of this relationship, because indirect effects (such as global effects on differentiation) could produce similar observations.

Figure 1.

(A) TRAP stain of wild-type (WT) and Mitfmi/mi mouse osteoclasts. Wild-type mouse osteoclasts were grown from spleen in the presence of serum, M-CSF, and 150 ng/ml RANKL (panel 1) or without RANKL (panel 2). At day 9 of culture the cells were stained for TRAP. TRAP-positive cells failed to form in the absence of RANKL. Day 9 wild-type (panel 3) and Mitfmi/mi (panel 4) mouse osteoclasts grown in complete medium (containing RANKL) and stained for TRAP. TRAP-positive osteoclasts were successfully generated from Mitfmi/mi splenocytes, although TRAP intensity and number of nuclei per cell were somewhat diminished. (B) Mitfmi/mi mutant osteoclasts contain decreased levels of cathepsin K protein. Total protein from day 10 osteoclast cultures of wild-type or Mitfmi/mi osteoclasts was subjected to Western blotting with anti-cathepsin K (2-min and a longer 10-min Western blot exposures are shown) and antitubulin antibodies. (C) Mitfmi/mi mutant osteoclasts contain decreased levels of cathepsin K mRNA. Poly(A)+ RNA from day 10 osteoclast cultures of wild-type or Mitfmi/mi osteoclasts was analyzed by Northern blotting using probes for mouse cathepsin K, c-fms, RANK, and GAPDH.

Cathepsin K Is a Transcriptional Target of Mitf and TFE3 via Three Consensus Elements in the Cathepsin K Promoter.

To examine whether Mitf is directly involved in cathepsin K regulation in osteoclasts, a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments was performed. Examination of the human cathepsin K promoter (25, 26) revealed four E-boxes that match the consensus to which the Mitf family may bind, located between −928 to +2 bp (Fig. 2A). Gel-shift assays were performed to determine whether Mitf can bind these E-boxes in the cathepsin K promoter. Endogenous Mitf from nuclear extract of cultured human osteoclasts was found to bind E-boxes 1, 2, and 3 as shown by supershift by using a mAb against Mitf (Fig. 2B). Specificity of binding was shown by cold competition studies by using wild-type vs. double point mutant competitor probes. In contrast, binding was not observed for E-box 4. Interestingly, E-box 4 lacks a 5′ flanking T, which has been suggested to be required for recognition of this hexanucleotide core sequence by Mitf (27). For E-boxes 1–3, one or possibly two nonsupershifted bands demonstrate specific DNA recognition as well, consistent with the possibility that factors in addition to Mitf are capable of interacting with E-box elements within the cathepsin K promoter.

Because TFE3 has been found to reside within osteoclasts (5), and thereby could potentially compensate in the setting of Mitf deficiency, both Mitf and TFE3 were assessed for cathepsin K promoter activation in reporter assays. Transient transfections were carried out to assess transactivation of the cathepsin K promoter encompassing base pairs −928 to +2. These studies were carried out in nonosteoclasts (MCF-7 cells) because cathepsin K-expressing primary osteoclasts are poorly transfectable (data not shown). The wild-type cathepsin K promoter was substantially up-regulated by both Mitf (8.6-fold) and TFE3 (22.9-fold) compared with vector controls (Fig. 3). To determine which potential binding sites are important in this regulation, individual E-box mutants were examined (Fig. 3). When E-boxes 1 or 2 were mutated, the cathepsin K promoter was no longer up-regulated by Mitf or TFE3. E-box 3 also contributed measurably to cathepsin K promoter activity, because its mutation caused a substantial decrease in promoter activation. In contrast, mutation of E-box 4 did not diminish Mitf or TFE3 responsiveness of the cathepsin K promoter (in fact, modestly enhancing responsiveness). It is possible that a component of transcriptional cooperativity operates at this promoter, because all three upstream sites can be bound, but mutation of any single site significantly affects the transcriptional response. The DNA binding and transcriptional reporter results thus demonstrate a consistent ability of either Mitf or TFE3 to modulate the cathepsin K promoter via three upstream E-box elements.

Mitf Up-Regulates Expression of Endogenous Cathepsin K in Cultured Human Osteoclasts.

To examine whether overexpression of Mitf regulates expression of endogenous cathepsin K, human osteoclasts were infected with replication incompetent adenoviruses containing wild-type Mitf, mutant Mitfmi (delR217) (7, 8), or GFP as a vector control. Adenoviral infection was optimal (>95% infection) at day 11 of the osteoclast culture, a stage when endogenous cathepsin K expression has not yet reached its maximum (data not shown). Later culture stages were substantially less infectable. Northern blot analysis demonstrated that wild-type Mitf up-regulated the expression of cathepsin K mRNA at both 46 h (4-fold) and 67 h (6-fold) postinfection as compared with GFP control (Fig. 4A). Endogenous cathepsin K signal was very weak in these young osteoclasts and was not affected by overexpression of mutant Mitf. TRAP, previously shown to be regulated by Mitf (16), also was up-regulated upon wild-type Mitf overexpression in primary human osteoclasts (Fig. 4B), showing that the effect of Mitf is not limited to cathepsin K. The protein levels of adenovirus-encoded wild-type and mutant Mitf were comparable in the infected osteoclasts (Fig. 4A). There were no recognizable morphological effects attributable to wild-type or mutant Mitf overexpression in these experiments. Mitf protein migrates as a doublet, reflecting presence or absence of a mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation that triggers both activation (19) and degradation (24, 28) of Mitf. Thus the endogenous cathepsin K promoter in primary human osteoclasts appears to be regulated by Mitf.

Cathepsin K Promoter Activity Is Disrupted by Osteopetrotic, but Not Nonosteopetrotic, Mouse Alleles of mitf.

The association of osteopetrosis with the mitf alleles mitfmi and mitfor, but not mitfce, was next examined by analysis of their effects on cathepsin K promoter activity in the presence of wild-type Mitf or TFE3. Wild-type Mitf protein up-regulated the human cathepsin K promoter whereas Mitfmi, Mitfor, or Mitfce mutant proteins had no significant transactivation activity (Fig. 5A). Mitfmi and Mitfor mutant proteins both interfered with cathepsin K promoter activation by wild-type Mitf (Fig. 5B) or TFE3 (Fig. 5C). For both of the osteopetrotic mutants, cathepsin K promoter activity was repressed in a statistically significant fashion (P < 0.04). In contrast, the nonosteopetrotic Mitf mutant Mitfce did not disrupt cathepsin K promoter activation by wild-type Mitf (Fig. 5B) and TFE3 (Fig. 5C).

The behavior of these mitf mutant alleles at the cathepsin K promoter recapitulates the osteoclast phenotype in the corresponding mouse strains. Structurally, these osteopetrotic mouse mutants, Mitfmi/mi and Mitfor/or, disrupt the basic domain of Mitf (8, 9), a short α-helical motif essential for DNA contact by the transcription factor dimer. Because both Mitfmi and Mitfor mutant proteins contain intact dimerization helix–loop–helix/leucine zipper (HLH-ZIP) motifs, these proteins retain the ability to dimerize with wild-type partners and sequester them in complexes incapable of binding DNA due to basic region disruption in the mutant partner (8). In contrast, the nonosteopetrotic mutation Mitfce contains a mutation that ablates the leucine zipper component of the HLH-ZIP region and produces a protein incapable of either dimerization or DNA binding (8, 9). As demonstrated previously, this allele does not disrupt DNA binding by wild-type Mitf protein (8), and as demonstrated here it is null with respect to transactivation potential at a target promoter as well. Pigment cell phenotypes are apparent for dominant negative mitf alleles in heterozygotes. However, no Mitf heterozygotes display osteopetrosis, probably due to dosage/compensation by TFE3.

These observations suggest that three E-box elements in the cathepsin K promoter are targeted by the Mitf family of basic/ helix–loop–helix/leucine zipper transcription factors to regulate cathepsin K expression in osteoclasts. Mitf and TFE3 share identical basic domain amino acid sequences (7, 20) and appear to recognize identical DNA elements as either homodimers or heterodimers (8). Because TFEB and TFEC also share these DNA recognition and dimerization specificities (8), it will be important to determine whether they also may produce overlapping transcriptional regulation in osteoclasts. Whereas genetic evidence clearly implicates Mitf in osteoclast function, genetic evidence of roles for the related family members still awaits analysis. Only murine TFEB knockouts have been described to date (29), and these display embryonic lethality due to a placental defect. Nonetheless, these data are consistent with the osteopetrotic phenotypic overlap of Mitf deficiency and cathepsin K mutation as seen in mice and humans. Although cathepsin K may play a role in the osteopetrosis of the Mitfmi/mi mice, it is unlikely to account for their fusion or mineral resorption defects.

Mitf or its related family members also are expressed in a variety of nonosteoclast cell types including melanocytes, mast cells, and retinal pigment epithelium (7). In melanocytes, cathepsin K mRNA does appear to be regulated in an Mitf-dependent fashion (M.H. and D.E.F., unpublished observations), which theoretically could impact on the aggressive behavior of melanomas, which typically express Mitf (30). Breast carcinomas also have been reported to express cathepsin K (17) and some also may express Mitf (30). It remains to be seen whether the Mitf family modulates cathepsin K expression in these tumors in a manner similar to cathepsin K regulation in osteoclasts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Kadesch for providing the expression vector for TFE3, Dr. M. Uskokovic of Hoffman-LaRoche for generous supply of vitamin D, Wade Huber for virus preparations, Dr. Ruth Halaban for 501mel cells, Drs. Maxine Gowen, Ian James, Pamela Yelick, Sonja Hicks, Armen Tashjian, Christine Hershey, Hans Widlund, Scott Schuyler, and members of the Fisher lab for helpful discussions, Jenny Liu for help with statistical analysis, and Ying Xu for technical assistance. G.M. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Predoctoral Fellowship and Harvard-Massachusetts Institute of Technology Health Sciences and Technology Research Assistantships. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (to D.E.F.). D.E.F. is the Jan and Charles Nirenberg Fellow at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- TRAP

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- M-CSF

macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- RANKL

receptor activator of NF-κB ligand

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

See commentary on page 5385.

References

- 1.Chambers T J. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38:241–252. doi: 10.1136/jcp.38.3.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suda T, Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Jimi E, Gillespie M T, Martin T J. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:345–357. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker D G. Science. 1975;190:784–785. doi: 10.1126/science.1105786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thesingh C W, Scherft J P. Bone. 1985;6:43–52. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(85)90406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weilbaecher K N, Hershey C L, Takemoto C M, Horstmann M A, Hemesath T J, Tashjian A H, Fisher D E. J Exp Med. 1998;187:775–785. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertwig P. Z Indukt Abstammungs-Vererbungsl. 1942;80:220–246. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgkinson C A, Moore K J, Nakayama A, Steingrimsson E, Copeland N G, Jenkins N A, Arnheiter H. Cell. 1993;74:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90429-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemesath T J, Steingrimsson E, McGill G, Hansen M J, Vaught J, Hodgkinson C A, Arnheiter H, Copeland N G, Jenkins N A, Fisher D E. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2770–2780. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steingrimsson E, Moore K J, Lamoreux M L, Ferre-D'Amare A R, Burley S K, Zimring D C, Skow L C, Hodgkinson C A, Arnheiter H, Copeland N G, et al. Nat Genet. 1994;8:256–263. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cielinski M J, Marks S C., Jr Bone. 1995;16:567–574. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00080-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nii A, Steingrimsson E, Copeland N G, Jenkins N A, Ward J M. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1871–1882. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saftig P, Hunziker E, Wehmeyer O, Jones S, Boyde A, Rommerskirch W, Moritz J D, Schu P, von Figura K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13453–13458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowen M, Lazner F, Dodds R, Kapadia R, Feild J, Tavaria M, Bertoncello I, Drake F, Zavarselk S, Tellis I, et al. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1654–1663. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.10.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelb B D, Shi G P, Chapman H A, Desnick R J. Science. 1996;273:1236–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy H M. Calcif Tissue Res. 1973;13:19–26. doi: 10.1007/BF02015392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luchin A, Purdom G, Murphy K, Clark M Y, Angel N, Cassady A I, Hume D A, Ostrowski M C. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:451–460. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Littlewood-Evans A J, Bilbe G, Bowler W B, Farley D, Wlodarski B, Kokubo T, Inaoka T, Sloane J, Evans D B, Gallagher J A. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5386–5390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarma U, Flanagan A M. Blood. 1996;88:2531–2540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemesath T J, Price E R, Takemoto C, Badalian T, Fisher D E. Nature (London) 1998;391:298–301. doi: 10.1038/34681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckmann H, Su L K, Kadesch T. Genes Dev. 1990;4:167–179. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson D M, Maraskovsky E, Billingsley W L, Dougall W C, Tometsko M E, Roux E R, Teepe M C, DuBose R F, Cosman D, Galibert L. Nature (London) 1997;390:175–179. doi: 10.1038/36593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Mochizuki S, Tomoyasu A, Yano K, Goto M, Murakami A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacey D L, Timms E, Tan H L, Kelley M J, Dunstan C R, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, et al. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu M, Hemesath T J, Takemoto C M, Horstmann M A, Wells A G, Price E R, Fisher D Z, Fisher D E. Genes Dev. 2000;14:301–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rood J A, Van Horn S, Drake F H, Gowen M, Debouck C. Genomics. 1997;41:169–176. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelb B D, Shi G P, Heller M, Weremowicz S, Morton C, Desnick R J, Chapman H A. Genomics. 1997;41:258–262. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aksan I, Goding C R. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6930–6938. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.6930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu W, Gong L, Haddad M M, Bischof O, Campisi J, Yeh E T, Medrano E E. Exp Cell Res. 2000;255:135–143. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steingrimsson E, Tessarollo L, Reid S W, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:4607–4616. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King R, Weilbaecher K N, McGill G, Cooley E, Mihm M, Fisher D E. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:731–738. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65172-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.