Abstract

Objectives To estimate the cost effectiveness of alternative planned places of birth.

Design Economic evaluation with individual level data from the Birthplace national prospective cohort study.

Setting 142 of 147 trusts providing home birth services, 53 of 56 freestanding midwifery units, 43 of 51 alongside midwifery units, and a random sample of 36 of 180 obstetric units, stratified by unit size and geographical region, in England, over varying periods of time within the study period 1 April 2008 to 30 April 2010.

Participants 64 538 women at low risk of complications before the onset of labour.

Interventions Planned birth in four alternative settings: at home, in freestanding midwifery units, in alongside midwifery units, and in obstetric units.

Main outcome measures Incremental cost per adverse perinatal outcome avoided, adverse maternal morbidity avoided, and additional normal birth. The non-parametric bootstrap method was used to generate net monetary benefits and construct cost effectiveness acceptability curves at alternative thresholds for cost effectiveness.

Results The total unadjusted mean costs were £1066, £1435, £1461, and £1631 for births planned at home, in freestanding midwifery units, in alongside midwifery units, and in obstetric units, respectively (equivalent to about €1274, $1701; €1715, $2290; €1747, $2332; and €1950, $2603). Overall, and for multiparous women, planned birth at home generated the greatest mean net benefit with a 100% probability of being the optimal setting across all thresholds of cost effectiveness when perinatal outcomes were considered. There was, however, an increased incidence of adverse perinatal outcome associated with planned birth at home in nulliparous low risk women, resulting in the probability of it being the most cost effective option at a cost effectiveness threshold of £20 000 declining to 0.63. With regards to maternal outcomes in nulliparous and multiparous women, planned birth at home generated the greatest mean net benefit with a 100% probability of being the optimal setting across all thresholds of cost effectiveness.

Conclusions For multiparous women at low risk of complications, planned birth at home was the most cost effective option. For nulliparous low risk women, planned birth at home is still likely to be the most cost effective option but is associated with an increase in adverse perinatal outcomes.

Introduction

Since the early 1990s, government policy on maternity care in England has moved towards policies designed to give women with straightforward pregnancies a choice of settings for birth.1 2 In this context, freestanding midwifery units, midwifery units located in the same building or on the same site as an obstetric unit (hereafter referred to as alongside midwifery units), and home birth services have increasingly become relevant to the configuration of maternity services under consideration in England.3 The relative benefits and risks of birth in these alternative settings have been widely debated in recent years.4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lower rates of obstetric interventions and other positive maternal outcomes have been consistently found in planned births at home and in midwifery units, but clear conclusions regarding perinatal outcome have been lacking. Moreover, robust evidence on the cost effectiveness of birth in alternative settings is a priority, as was highlighted by the recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical guidance on intrapartum care.11 The Birthplace in England research programme was designed to fill gaps in research evidence about the processes and outcomes associated with different settings for birth in the NHS in England. The results of the safety outcomes generated by the Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study (hereafter referred to as the cohort study) are reported elsewhere.12 We report on the cost effectiveness of alternative planned places of birth based on data collected by the research programme.

Methods

Study population

The study population included all “low risk” women who participated in the cohort study, as described elsewhere.12 In brief, the cohort study was designed to compare outcomes in women judged to be at low risk of complications before the onset of labour. Outcomes were compared by planned place of birth: at home, in freestanding midwifery units, in alongside midwifery units, or in obstetric units. The cohort study aimed to collect data in every NHS trust in England that provides home birth services, every free standing midwifery unit, every alongside midwifery unit, and a random sample of obstetric units, stratified by unit size and geographical region, over varying periods of time within the study period (1 April 2008 to 31 April 2010). The target sample size was at least 57 000 women: 17 000 planned home births, 5000 planned births in free standing midwifery units, 5000 planned births in alongside midwifery units, and 30 000 planned births in obstetric units, of which we estimated 20 000 would be low risk. The definition of low risk used in the cohort study was based on criteria contained in the NICE Intrapartum Care Guidelines.11 The primary clinical outcome was a composite measure of adverse perinatal outcomes encompassing perinatal mortality and specified neonatal morbidities (box). Other outcomes considered were adverse maternal morbidity and “normal birth” (box). Further design details for the cohort study, including the eligibility criteria, sample size calculations, derivation of risk status, outcome measures, and ethical procedures, are reported elsewhere.13

Definitions of key variables

Adverse perinatal outcome: a composite of perinatal mortality and specified neonatal morbidities: stillbirth after the start of care in labour, early neonatal death, neonatal encephalopathy, meconium aspiration syndrome, brachial plexus injury, fractured humerus, or fractured clavicle

Adverse maternal morbidity: defined as at least one of: general anaesthetic; instrumental birth; caesarean section; third or fourth degree perineal trauma; blood transfusion; admission to an intensive treatment unit, high dependency unit, or specialist unit; or maternal death (within 42 days after giving birth)

Normal birth: defined by the Maternity Care Working Party14 as birth without any of: induction of labour; epidural or spinal analgesia; general anaesthetic; episiotomy; forceps, ventouse, or caesarean section

Complicating conditions identified at the start of care in labour: prolonged rupture of membranes (>18 hours), meconium stained liquor, proteinuria (1+ or more), hypertension, abnormal vaginal bleeding, non-cephalic presentation, abnormal fetal heart rate, or other complications.

Type of economic evaluation, study perspective, and time horizon

The economic evaluation took the form of a cost effectiveness analysis in which we estimated the incremental costs (ΔC) and incremental effects (ΔE) attributable to planned birth at home, in a free standing midwifery unit, or in an alongside midwifery unit, with reference to planned birth in an obstetric unit, and expressed each in terms of an incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER; ΔC/ΔE). The obstetric unit group contained the largest number of eligible births and was therefore used as the reference to maximise statistical efficiency. Estimates of cost effectiveness were made for the primary clinical outcome—adverse perinatal outcome—and for two secondary outcomes—namely, adverse maternal morbidity and normal birth. The economic evaluation was conducted from a health system perspective and consequently we have included only direct costs to the NHS.15 The time horizon primarily mirrored the duration of follow-up of the cohort study, which identified women at the start of their care in labour and was completed when the intrapartum and immediate after birth care for both mother and baby ended, be it at home or at discharge from a midwifery unit or hospital. If higher level care after the birth was required for the mother or the baby, or both, this was included in the economic evaluation.

Measurement of resource use

Individual data collection forms, designed as part of the cohort study, documented duration of labour, mode of delivery, some forms of pain relief, active management of the third stage of labour, whether an episiotomy was performed, clinical complications, length of stay for both mother and baby by type of ward and level of care, and transfers by duration and mode.

To estimate additional resource use not captured on an individual level in the cohort study, we developed supplemental data collection forms after five focus groups held with midwives from all parts of England early in the project. These forms were designed to capture the pathways of care experienced by individual women progressing through the stages of labour and care after birth and their associated resource inputs. For the purposes of this economic evaluation, the forms were initially used in a related study funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) research for patient benefit programme “assessing the impact of a new birth centre on choice and outcome of maternity care in an inner city area,” which will be reported in full elsewhere, comparing the costs of care in a free standing midwifery unit with care in an obstetric unit in the same trust.16 The data collected included details of staffing levels, treatments, surgeries, diagnostic imaging tests, scans, drugs, and other resource inputs associated with each stage of the pathway through intrapartum and after birth care. Interviews with senior midwives from different geographical regions in England were then conducted to standardise the supplemental resource profiles.

Unit cost estimation

Unit cost estimation involved a combination of bottom-up and top-down costing methods and followed guidance on costing healthcare services as part of an economic evaluation.15 17 Detailed unit costs, derived from the finance departments of participating trusts and information provided by senior midwives, were estimated for resource inputs into the following components of intrapartum and after birth care for all settings: homebirth delivery packs; NHS reimbursement for midwifery travel; some forms of pain relief; alternative modes of delivery; active management of the third stage of labour; suturing for episiotomy; suturing third and fourth degree perineal tears; manual removal of the placenta; blood transfusions; and care after a stillbirth or neonatal death. Unit overheads were estimated through the same finance departments for all settings and covered management and administrative costs, operational costs (including heating and lighting, training, building maintenance), indirect overheads (including personnel and finance functions), and capital costs based on the new build and land requirements of NHS facilities, accounting for unit occupancy rates. These data were used to generate an overheads cost per place of birth per hour. Midwifery staffing and attributable on-costs, with the addition of contributions to the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trust (CNST), were derived from national sources and were weighted for length of labour care for all planned places of birth.18 19 These midwifery costs were considered to be a major cost driver across all settings for birth and were allocated directly to the duration (hours) of the labour episode per woman. This included the midpoint salary for a band 6 or 7 midwife, including salary on-costs, direct and indirect overheads, and contributions to qualifications, adjusted for working hours a week and study and leave days. Drug costs were supplemented with data from the British National Formulary, number 61.20 Similarly, the costs of medical supplies were supplemented with data from the NHS Supply Chain Catalogue, April 2009 version.21 Costs per day for each level of neonatal care, as well as high dependency or intensive care for the mother, were derived from national reference costs from the Department of Health.22 Costs of emergency and non-emergency transfers were derived from secondary sources but weighted by individual level data on duration and mode of transport.22 All unit costs in this study were expressed in pounds sterling (£) and valued at 2009-10 prices.

Cost effectiveness analytical methods

We estimated differences in resource use and costs with the independent samples t test procedure and differences in effects with odds ratios and weighted incidence rates from the cohort study. Cost effectiveness was expressed as incremental cost per adverse perinatal outcome avoided, per maternal morbidity avoided, and per additional “normal birth.” For reasons explained in the cohort study report, obstetric units contained more women in whom complicating conditions were an unexpected observation, which suggests that the risk profile of low risk women varied between the settings. To ensure that women we compared had comparable risk status, we repeated all of these analyses for low risk women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour (see box for the list of complicating conditions).12 13 We used non-parametric bootstrapping, involving 1000 bias corrected replications of each of the incremental cost effectiveness ratios, to calculate uncertainty around all cost effectiveness estimates.23 24 This was represented on four quadrant cost effectiveness planes. Though cost effectiveness estimates were weighted, neither costs nor effects were adjusted for potential confounders in the baseline analyses. Weighting accounted for each unit’s duration of participation in the study and took into account the clustered nature of the data within the cohort study. Probability weights were incorporated in the analysis to adjust for the probability of selection of each woman. The weight applied to each observation was inversely proportional to the probability of selection of the unit and the duration of data collection in that unit. The weights were recalculated for each bootstrapped sample. Decision uncertainty was examined by estimating net benefit statistics and constructing cost effectiveness acceptability curves across cost effectiveness threshold values of between £0 and £100 000 for the health outcomes of interest.

In a series of subgroup analyses we repeated all analyses by parity subgroup for the primary cost effectiveness outcome—namely, incremental cost per adverse perinatal outcome avoided. In addition, we undertook a series of sensitivity analyses to explore the implications of uncertainty surrounding key drivers of cost in intrapartum care and the variables for which there was the most uncertainty surrounding the resource use parameters. These included varying the overheads, occupancy rates, and staffing costs attributed to the duration of labour care. We recalculated the incremental cost effectiveness ratios after these sensitivity analyses.

We used multiple regression to estimate the differences in total cost between the settings for birth and to adjust for potential confounders, including maternal age, parity, ethnicity, understanding of English, marital status, BMI, index of multiple deprivation score, parity, and gestational age at birth, which could each be associated with planned place of birth and with adverse outcomes.12 For the generalised linear model on costs, we selected a γ distribution and identity link function in preference to alternative distributional forms and link functions on the basis of its low Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) statistic. All analyses were performed with Stata version 11, SPSS version 17 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) 2010 software.

Results

The cohort study recruited 79 774 eligible women, 64 538 of whom were at low risk of complications before the onset of labour. The women were recruited from 142 of 147 trusts providing home birth services, 53 of 56 freestanding midwifery units, 43 of 51 alongside midwifery units, and a stratified random sample of 36 of 180 obstetric units. Analyses reported in detail elsewhere12 found that, overall, there were no significant differences in the odds of adverse perinatal outcome for planned births in any of the non- obstetric unit settings compared with the obstetric units. Complicating conditions identified at the start of care in labour, however, were more common among low risk women in the planned obstetric unit group, suggesting that the groups were not homogeneous with regard to risk. In further analyses restricted to women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour, the adjusted odds of adverse perinatal outcomes were higher for births planned at home compared with those planned in obstetric units (adjusted odds ratio 1.59, 95% confidence interval 1.01 to 2.52). In the restricted analyses, we did not find an increase in adverse perinatal outcomes for births planned in either free standing midwifery units or alongside midwifery units. Subgroup analyses by parity showed a significantly increased adjusted odds of adverse perinatal outcome for nulliparous women for births planned at home compared with those planned in obstetric units (1.75, 1.07 to 2.86); the strength of this association increased among women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour (2.80, 1.59 to 4.92). The adjusted odds of the secondary maternal outcomes—namely, maternal morbidity avoided and “normal birth”—were significantly increased for planned births in all three non-obstetric unit settings compared with those planned in obstetric units. Further details on the characteristics of the recruited women, and their clinical and safety outcomes, are reported in the cohort paper and the fuller report.12 13

Profiles of resource use, and their associated unit costs, for each planned place of birth are reported in detail in appendices 1 and 2 on bmj.com.25 The total mean costs per low risk woman planning birth in the various settings at the start of care in labour were £1631 (€1950, $2603) for an obstetric unit, £1461 (€1747, $2332) for an alongside midwifery unit, £1435 (€1715, $2290) for a free standing midwifery unit, and £1067 (€1274, $1701) for the home (table 1). Unit overheads and staffing costs were the key drivers of cost in these analyses. Restriction of the analyses to low risk women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour narrowed the cost differences between planned places of birth: total mean costs were £1511 for an obstetric unit, £1426 for an alongside midwifery unit, £1405 for a free standing midwifery unit, and for £1027 the home (table 2). The generalised linear model on costs showed that, even after adjustment for clinical and sociodemographic confounders, planned birth in settings other than obstetric units remained cost saving compared with the reference category of the obstetric unit: savings averaged £134, £130, and £310 for planned births in alongside midwifery units, free standing midwifery units, and at home, respectively (P<0.001) (see appendix 3 on bmj.com). This model also showed that being multiparous or married was associated with reduced costs, while birth after 40 weeks’ gestation, being overweight or obese, and maternal age of 30 or more were each associated with increased costs.

Table 1.

Mean cost (£) per woman according to planned place of birth for all women at low risk of complications (2009-10 prices)

| Cost category | Mean (SE) cost (£) | P value* | Bootstrap mean difference (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetric unit (OU) | Home | Free standing midwifery unit (FMU) | Alongside midwifery unit (AMU) | |||||

| OU−home | OU−FMU | OU−AMU | ||||||

| Overheads | 569 (2.9) | 93 (1.9) | 426 (3.1) | 451 (2.8) | <0.001 | −475.6 (−482.0 to −468.8) | −143.3 (−152.2 to −134.9) | −118.7 (−126.9 to −110.6) |

| Midwifery staffing | 472 (2.4) | 581 (2.8) | 578 (3.8) | 611 (3.4) | <0.001 | 108.1 (100.2 to 116.4) | 105.2 (95.9 to 114.4) | 138.7 (130.4 to 147.2) |

| Homebirth resources | 0 (0) | 112 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | <0.001 | 111.7 (111.2 to 112.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Transfers | 0 (0) | 34 (0.7) | 49 (1.0) | <0.01 (0.0) | <0.001 | 33.7 (32.4 to 35.1) | 49.1 (46.9 to 51.2) | 0.0036 (0.0034 to 0.0037) |

| Procedures after transfer | 0 (0) | 53 (0.9) | 36 (0.7) | 43 (0.6) | <0.001 | 53.0 (51.2 to 54.8) | 36.4 (34.9 to 37.8) | 42.9 (41.8 to 44.2) |

| Birth | 207 (2.5) | 77 (1.5) | 94 (2.1) | 114 (1.9) | <0.001 | −130.1 (−135.8 to −124.7) | −113.4 (−119.9 to −107.2) | −92.9 (−99.2 to −86.6) |

| Procedures during labour care | 174 (1.9) | 50 (1.3) | 65 (1.7) | 84 (1.5) | <0.001 | −122.8 (−127.1 to −118.2) | −109.3 (−114.2 to −104.4) | −89.9 (−94.9 to −85.1) |

| Postnatal care | 122 (0.6) | 18 (0.4) | 127 (0.9) | 102 (0.6) | <0.001 | 104.3(−105.9 to −102.5) | 5.1 (2.7 to 7.6) | −20.1 (−22.1 to −18.3) |

| Higher care-mother | 22 (0.9) | 8 (0.8) | 9 (0.9) | 11.8 (0.6) | <0.001 | −13.2 (−15.5 to −10.8) | −11.9 (−14.3 to −9.8) | −9.6 (−11.8 to −7.6) |

| Admission to higher care-baby | 64 (5.2) | 42 (4.3) | 50 (7.5) | 45 (6.2) | 0.037 | −21.9 (−36.6 to −9.4) | −15.0 (−32.8to −3.7) | −19.6 (−35.6 to −1.9) |

| Total cost | 1631 (10.1) | 1067 (8.9) | 1435 (13.5) | 1461 (11.1) | <0.001 | −564.6 (−591.7 to −533.9) | −195.4 (129.1 to −157.4) | −169.5 (−199.7 to −137.4) |

*Estimated though analysis of variance.

Table 2.

Mean cost (£) per woman according to planned place of birth for women at low risk and without complicating conditions at start of care in labour (2009-10 prices)

| Cost category | Mean (SE) cost (£) | P value* | Bootstrap mean difference (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetric unit (OU) | Home | Free standing midwifery unit (FMU) | Alongside midwifery unit (AMU) | |||||

| OU−home | OU−FMU | OU−AMU | ||||||

| Overheads | 545 (3.1) | 81 (1.8) | 420 (3.2) | 442 (2.8) | <0.001 | −463.2 (−473.6 to −453.8) | −125.2 (−138.8 to −111.5) | −103.2 (−115.7 to −90.2) |

| Midwifery staffing | 452 (2.6) | 574 (2.9) | 573 (3.9) | 603 (3.5) | <0.001 | 121.9.0 (109.8 to 133.3) | −120.9 (107.7 to 137.6) | 151.1 (136.9 to 165.2) |

| Homebirth resources | 0 (0) | 112 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | 111.7 (111.2 to 112.1) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) |

| Transfers | 0 (0) | 32 (0.7) | 46 (1.0) | <0.01 (0.0) | <0.001 | 31.6 (29.1 to 33.8) | 46.2 (42.2 to 49.2) | 0.0036 (0.0034 to 0.0037) |

| Procedures after transfer | 0 (0) | 49 (0.9) | 34 (0.7) | 40 (0.6) | <0.001 | 49.4 (47.6 to 51.2) | 33.9 (32.5 to 35.4) | 40.2 (38.9 to 41.5) |

| Birth | 175 (2.5) | 71 (1.5) | 89 (2.1) | 108 (1.9) | <0.001 | −104.4 (−113.3 to −95.8) | −86.2 (−95.9 to −76.2) | −67.4 (−76.1 to −56.1) |

| Procedures during labour care | 152 (2.0) | 46 (1.2) | 62 (1.7) | 80 (1.5) | <0.001 | −105.3 (−112.7 to −96.1) | −90.1 (−98.2 to −82.4) | −71.8 (−78.9 to −63.3) |

| Postnatal care | 114 (0.7) | 16 (0.4) | 126 (0.9) | 100 (0.6) | <0.001 | −98.8 (−101.3 to −96.1) | 11.5 (7.63 to 14.9) | −14.23 (−17.7 to −11.7) |

| Admission to higher care-mother | 19 (0.9) | 7 (0.8) | 9 (0.9) | 11 (0.6) | <0.001 | −11.3 (−15.3 to −7.6) | −9.6 (−15.4 to −5.1) | −7.6 (−10.8 to −4.5) |

| Admission to higher care-baby | 54 (5.8) | 38 (4.3) | 47 (7.8) | 43 (6.4) | 0.037 | −16.9 (−39.5 to 5.5) | −7.02 (−38.9 to −35.1) | −11.7 (−27.1 to 20.3) |

| Total cost | 152 (10.1) | 1027 (8.8) | 1405 (13.7) | 1426 (11.3) | <0.001 | −483.8 (−537.5 to −435.6) | −105.1 (−165.4 to −45.6) | −84.0 (−114.4 to −55.2) |

*Estimated though analysis of variance.

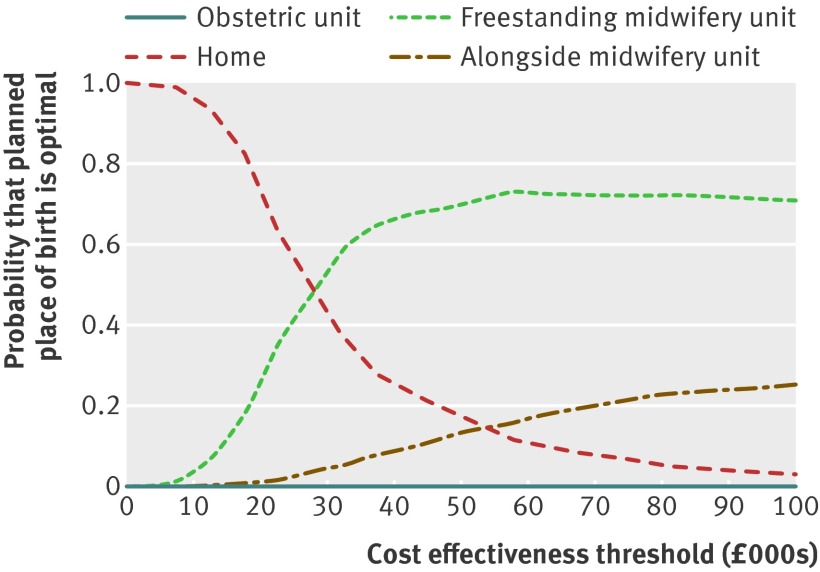

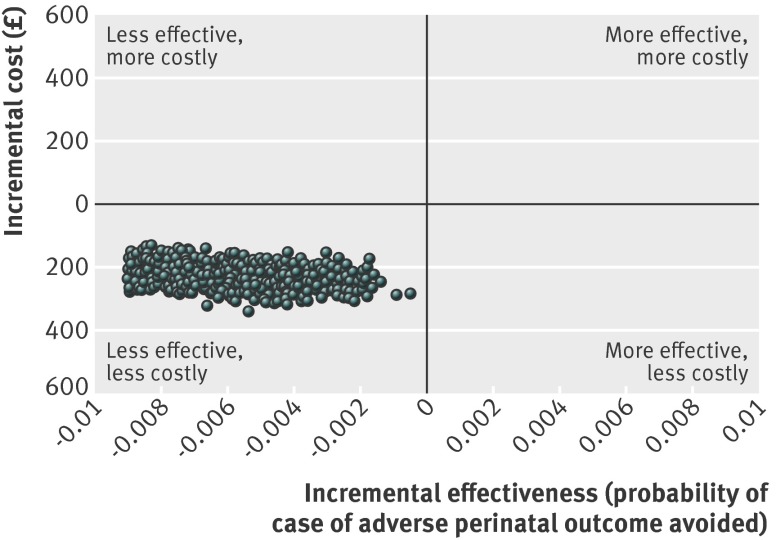

Table 3 presents incremental cost effectiveness ratios and net benefit statistics for the primary clinical outcome—namely, adverse perinatal outcome avoided for low risk women. For all low risk women, bootstrapped estimates showed that planned birth in settings other than an obstetric unit was associated with cost savings and considerable stochastic uncertainty surrounding adverse perinatal outcomes. Consequently, for all shifts to settings other than an obstetric unit from planned birth in obstetric units, the bootstrapped incremental cost effectiveness ratios fell across both the south east (representing reduced costs and improved outcomes) and south west (representing reduced costs and worse outcomes) quadrants of the cost effectiveness plane.25 Switching from planned birth in an obstetric unit to home birth was on average cost saving, while the average increase in adverse perinatal outcomes was not significant. Switching from planned birth in an obstetric unit to midwifery units was on average cost saving and associated with a non-significant decrease in adverse perinatal outcomes. Differences in perinatal effects were small; however these are magnified in the incremental cost effectiveness ratio calculations, as the mean differences in effects are used as the denominators of the incremental cost effectiveness ratios. Thus, the mean incremental cost effectiveness ratios ranged from −£296 400 to £7 950 356, reflecting sizable reductions in cost and small changes in perinatal outcome when assessing shifts from planned birth in obstetric unit to settings other than an obstetric unit. When the cost effectiveness outcomes were analysed by parity, planned birth at home in nulliparous low risk women was associated with significant cost savings and a significant increase in adverse perinatal outcomes; bootstrapped incremental cost effectiveness ratios largely fell in the south west quadrant of the cost effectiveness plane (representing, on average, reduced costs and worse outcomes).25 There was a 0.63 probability of home birth being the most cost effective option and a 0.35 probability of free standing midwifery units being the most cost effective option at a £20 000 cost effectiveness threshold for avoiding an adverse perinatal outcome (fig 1). This decision uncertainty surrounding the most cost effective option was not found for place of birth in multiparous low risk women, on whom planned home birth had a 100% probability of being the most cost effective option across all cost effectiveness thresholds between £0 and £100 000 (table 3).

Table 3.

Incremental cost effectiveness ratios and net benefit statistics for primary outcome (adverse perinatal outcome avoided) for all women at low risk of complications according to planned place of birth: home, freestanding midwifery unit (FMU), or alongside midwifery unit (AMU) with obstetric unit (OU) as reference

| Home | FMU | AMU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All low risk women | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −565 (−591 to −538) | −196 (−229 to −163) | −170 (−199 to −141) |

| Difference in adverse perinatal outcome* avoided (95% CI) | −0.00007 (−0.0014 to 0.0013) | 0.0004 (−0.0010 to 0.0019) | 0.0005 (−0.0007 to 0.0019) |

| Mean ICER† | 7 950 356 | −431 873 | −296 400 |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South west | South east | South east |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)‡ | 592 (547 to 639) | 263 (211 to 315) | 167 (111 to 224) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)§ | 593 (535 to 654) | 270 (205 to 334) | 174 (99 to 244) |

| Nulliparous low risk women | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −281 (−343 to −217) | −163 (−217 to −108) | −92 (−142 to −33) |

| Difference in adverse perinatal outcome* avoided (95% CI) | −0.004 (−0.008 to −0.00001) | 0.0008 (−0.002 to 0.003) | 0.0005 (−0.003 to 0.003) |

| Mean ICER† | 69761 | −98136 | −47995 |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South west | South east | South east |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)‡ | 204 (77 to 319) | 179 (98 to 259) | 103 (9 to 189) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)§ | 165 (−2 to 321) | 188 (87 to 289) | 110 (−10 to 217) |

| Multiparous low risk women | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −362 (−390 to −335) | −173 (−208 to −139) | −151 (−184 to −117) |

| Difference in adverse perinatal outcome* avoided (95% CI) | 0.001 (−0.0004 to 0.0025) | 0.0005 (−0.0015 to 0.0024) | 0.0007 (−0.001 to 0.003) |

| Mean ICER† | −323 037 | −128 134 | −119 618 |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South east | South east | South east |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)‡ | 382 (336 to 427) | 182 (120 to 244) | 165 (115 to 222) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)§ | 391 (335 to 451) | 186 (107 to 267) | 172 (108 to 244) |

*Composite of perinatal mortality and specified neonatal morbidities: stillbirth after start of care in labour, early neonatal death, neonatal encephalopathy, meconium aspiration syndrome, brachial plexus injury, fractured humerus, or fractured clavicle.

†95% CI not provided because bootstrapped replicates of incremental cost effectiveness ratios fell across more than one quadrant of cost effectiveness plane.

‡Estimated at £20 000 cost effectiveness threshold.

§Estimated at £30 000 cost effectiveness threshold.

Fig 1 Cost effectiveness acceptability curves for planned place of birth for all low risk nulliparous women for adverse perinatal outcome avoided. At all £10 000 intervals, obstetric units were dominated by other settings and were found to have zero probability of cost effectiveness

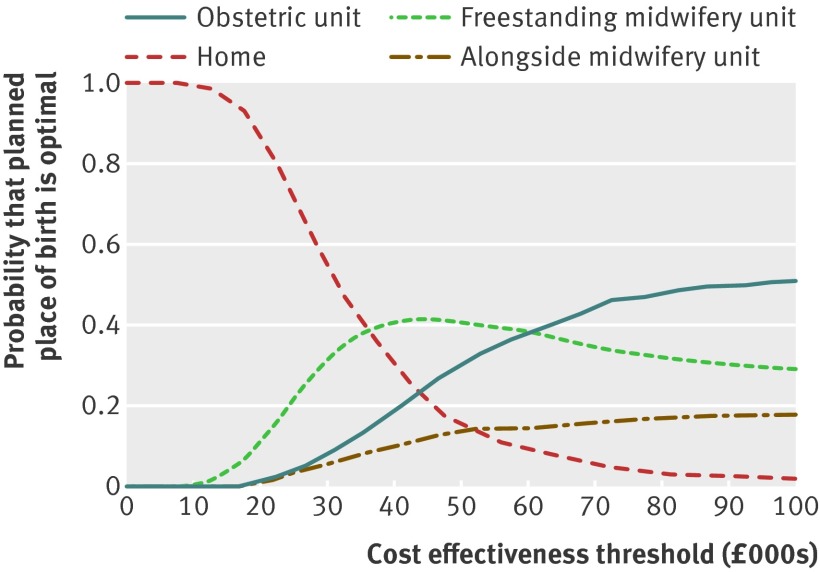

For low risk women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour, the mean incremental cost effectiveness ratios associated with switches from planned birth in obstetric unit to non-obstetric unit settings fell in the south west quadrant of the cost effectiveness plane (representing, on average, reduced costs and worse outcomes).25 The mean incremental cost effectiveness ratios ranged from £143 382 (alongside midwifery units) to £497 595 (home) (table 4). Planned birth at home in low risk women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour was associated with significant cost savings and a significant decrease in adverse perinatal outcomes avoided. Differences in adverse perinatal outcome were not significant for planned births in midwifery units. When we analysed the cost effectiveness outcomes by parity, all bootstrapped incremental cost effectiveness ratios for planned birth at home in nulliparous low risk women without complicating conditions fell in the south west quadrant of the cost effectiveness plane (less costly, less effective) (fig 2). At a £20 000 cost effectiveness threshold for avoiding an adverse perinatal outcome, there was a 0.80 probability of home birth being the most cost effective option and a 0.16 probability of free standing midwifery units being the most cost effective option (fig 3). This decision uncertainty surrounding the most cost effective option was not found for place of birth in multiparous low risk women without complicating conditions, in whom planned home birth had a 100% probability of being the most cost effective option across all thresholds of cost effectiveness (table 4).

Table 4.

Incremental cost effectiveness ratios and net benefit statistics for primary outcome (adverse perinatal outcome avoided) in women without complications at start of care in labour according to planned place of birth: home, freestanding midwifery unit (FMU), or alongside midwifery unit (AMU) with obstetric unit (OU) as reference

| Home | FMU | AMU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All low risk women without complicating conditions | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −484 (−511 to −456) | −105 (−139 to −71) | −84 (−115 to −53) |

| Difference in adverse perinatal outcome* avoided (95% CI) | −0.0009 (−0.0023 to −0.0003) | −0.0003 (−0.0017 to 0.0011) | −0.0005 (−0.0019 to 0.0007) |

| Mean ICER† | 497 595 | 313 886 | 143 382 |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South west | South west | South west |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)‡ | 483 (434 to 534) | 143 (92 to 193) | 58 (5 to 114) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)§ | 473 (410 to 536) | 140 (74 to 200) | 53 (−13 to 121) |

| Nulliparous low risk women without complicating conditions | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −222 (−281 to −157) | −598 (−117 to −3) | −8 (−61 to 48) |

| Difference in adverse perinatal outcome* avoided (95% CI) | −0.006 (−0.011 to −0.002) | −0.001 (−0.004 to 0.0012) | −0.00099 (−0.0041 to 0.0013) |

| Mean ICER | 39 178 (16 734 to 103 511) | 30 169† | 1631† |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South west | South west | South west |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)‡ | 98 (−35 to 210) | 35 (−34 to 127) | −13 (−99 to 64) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)§ | 38 (−142 to 180) | 23 (−85 to 135) | −22 (−138 to 73) |

| Multiparous low risk women without complicating conditions | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −311 (−340 to −285) | −124 (−158 to −88) | −98 (−64 to −132) |

| Difference in adverse perinatal outcome* avoided (95% CI) | 0.0005 (−0.0008 to 0.0019) | 0.0003 (−0.0015 to −0.0020) | −0.00009 (−0.00196 to 0.00162) |

| Mean ICER† | −315420 | −92180 | 47222 |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South east | South east | South west |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)‡ | 321 (271 to 367) | 128 (71 to 183) | 98 (41 to 151) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)§ | 327 (262 to 384) | 132 (59 to 200) | 97 (24 to 165) |

*Composite of perinatal mortality and specified neonatal morbidities: stillbirth after start of care in labour, early neonatal death, neonatal encephalopathy, meconium aspiration syndrome, brachial plexus injury, fractured humerus, or fractured clavicle.

†95% CI not provided because bootstrapped replicates of incremental cost effectiveness ratios fell across more than one quadrant of cost effectiveness plane.

‡Estimated at £20 000 cost effectiveness threshold.

§Estimated at £30 000 cost effectiveness threshold.

Fig 2 Cost effectiveness plane: planned birth at home compared with planned birth in obstetric units for nulliparous low risk women without complicating conditions at start of care in labour

Fig 3 Cost effectiveness acceptability curves for planned place of birth for nulliparous low risk women without complicating conditions at start of care in labour for adverse perinatal outcome avoided

When we analysed the effects of planned place of birth on maternal outcomes, all shifts to non-obstetric unit settings were associated with significant cost savings and significant improvements in terms of maternal morbidity avoided (table 5) or additional normal birth (table 6). This was replicated for women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour. The mean net monetary benefit associated with shifts to non-obstetric unit settings varied from £2486 (£2259 to £2692) (alongside midwifery units) to £4498 (£4306 to £4669) (home) at a £20 000 cost effectiveness threshold for avoiding a maternal morbidity (table 5), and from £3828 (£3600 to £4052) (alongside midwifery units) to £6609 (£6411 to £6810) (home) at a £20 000 cost effectiveness threshold for achieving an additional normal birth (table 6). Birth at home generated the greatest mean net monetary benefit with a 100% probability of being the optimal setting across all thresholds of cost effectiveness (varied between £0 and £100 000 for the maternal outcomes of interest).

Table 5.

Incremental cost effectiveness ratios and net benefit statistics for maternal morbidity avoided in women at low risk of complications according to planned place of birth: home, freestanding midwifery unit (FMU), or alongside midwifery unit (AMU) with obstetric unit (OU) as reference

| Home | FMU | AMU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All low risk women | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −590 (−618 to −563) | −247 (−280 to −211) | −154 (−190 to −118) |

| Difference in maternal morbidity* avoided (95% CI) | 0.195 (0.187 to 0.204) | 0.172 (0.168 to 0.182) | 0.116 (0.106 to 0.126) |

| Mean ICER (95% CI) | −3024 (−3138 to −2912) | −1442 (−1600 to −1284) | −1322 (−1572 to −1049) |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South east | South east | South east |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)† | 4498 (4306 to 4669) | 3683 (3451 to 3904) | 2486 (2259 to 2692) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)§ | 6451 (6175 to 6705) | 5403 (5068 to 5716) | 3651 (3322 to 3950) |

| Low risk women without complicating conditions | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −504 (−535 to −474) | −150 (−186 to −115) | −69 (−105 to −36) |

| Difference in maternal morbidity* avoided (95% CI) | 0.165 (0.156 to 0.174) | 0.139 (0.131 to 0.149) | 0.088 (0.078 to 0.098) |

| Mean ICER (95% CI) | −3052 (−3215 to −2902) | −1075 (−1285 to −843) | −782 (−1130 to −431) |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South east | South east | South east |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)† | 3808 (3620 to 4012) | 2942 (2743 to 3166) | 1828 (1605 to 2059) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)§ | 5459 (5181 to 5754) | 4340 (4051 to 4658) | 2706 (2382 to 3040) |

*Defined as at least one of: general anaesthetic; instrumental birth; caesarean section; third or fourth degree perineal trauma; blood transfusion; admission to intensive treatment unit, high dependency unit, or specialist unit; and maternal death (within 42 days of giving birth). This is composite measure and was also secondary outcome of interest in cohort study.

†Estimated at £20 000 cost effectiveness threshold.

§Estimated at £30 000 cost effectiveness threshold.

Table 6.

Incremental cost effectiveness ratios and net benefit statistics for normal birth outcome in women at low risk of complications according to planned place of birth: home, freestanding midwifery unit (FMU), or alongside midwifery unit (AMU) with obstetric unit (OU) as reference

| Home | FMU | AMU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All low risk women | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −590 (−618 to −563) | −247 (−280 to −211) | −154 (−190 to −118) |

| Difference in normal birth* (95% CI) | 0.300 (0.290 to 0.310) | 0.256 (0.245 to 0.268) | 0.184 (0.173 to 0.194) |

| Mean ICER (95% CI) | −1960 (−2034 to −1890) | −956 (−1076 to −847) | −836 (−1002 to −664) |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South east | South east | South east |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)† | 6609 (6411 to 6810) | 5377 (5133 to 5618) | 3828 (3600 to 4052) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)‡ | 9618 (9334 to 9909) | 7941 (7585 to 8298) | 5663 (5332 to 5992) |

| Low risk women without complicating conditions | |||

| Cost difference (95% CI) | −504 (−535 to −474) | −150 (−187 to −116) | −69 (−105 to −36) |

| Difference in normal birth* (95% CI) | 0.266 (0.256 to 0.275) | 0.218 (0.207 to 0.229) | 0.149 (0.138 to 0.160) |

| Mean ICER (95% CI) | −1897 (−1985 to −1812) | −689 (−823 to −538) | −464 (−685 to −254) |

| Quadrant on cost effectiveness plane | South east | South east | South east |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)† | 5822 (5612 to 6036) | 4507 (4285 to 4766) | 3042 (2812 to 3307) |

| Mean net benefit (95% CI)‡ | 8483 (8178 to 8788) | 6688 (6367 to 7057) | 4526 (4188 to 4911) |

*Normal birth defined by Maternity Care Working Party as birth without any of induction of labour; epidural or spinal analgesia; general anaesthetic; episiotomy; forceps, ventouse, or caesarean section.

†Estimated at £20 000 cost effectiveness threshold.

‡Estimated at £30 000 cost effectiveness threshold.

Finally, sensitivity analyses showed that the mean incremental cost effectiveness ratios remained relatively robust to variations in overheads and staffing costs attributed to labour care but were sensitive to unit occupancy rates.25

Discussion

Summary of main findings

In this study of the cost effectiveness of alternative planned places of birth in England in women at low risk of complications before the onset of labour, we found that the cost of intrapartum and after birth care, and associated related complications, was less for births planned at home, in a free standing midwifery unit, or in an alongside midwifery unit compared with planned births in an obstetric unit. The total mean unadjusted costs per low risk woman before the onset of labour varied between £1066 for births planned at home and £1631 for births planned in obstetric units. Cost differences between alternative planned places of birth narrowed when we restricted the study population to women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour or to nulliparous women. Overall, and for multiparous women, planned birth at home generated the greatest mean net benefit with a 100% probability of being the optimal setting across all thresholds of cost effectiveness when perinatal outcomes were considered. There was, however, an increased incidence of adverse perinatal outcomes associated with planned birth at home in nulliparous low risk women, resulting in the probability of it being the most cost effective option at a threshold of £20 000 declining to 0.63. With regards to maternal outcomes, planned birth at home generated the greatest mean net benefit with a 100% probability of being the optimal setting across all cost effectiveness thresholds.

Strengths and weaknesses

This economic evaluation was based on a rigorously conducted cohort study of sufficient size to detect clinically important differences in adverse perinatal outcomes. Other strengths of the underpinning cohort study include high participation by midwifery units and trusts in England; the minimisation of selection bias through achievement of a high response rate and absence of self selection bias because of non-consent; and the ability to compare groups that were similar in terms of identified clinical risk.12 The economic evaluation was conducted according to nationally agreed design and reporting guidelines.15 26 Collection of primary unit cost data was thorough and accounted for regional differences in care patterns. We had a comprehensive strategy for handling uncertainty surrounding individual parameters and the value of the cost effectiveness threshold.

The study does have limitations. Firstly, some components of the unit cost data collection were based on limited returns from finance departments and had to be modelled with data from secondary sources.25 Nevertheless, with the exception of variations in unit occupancy rates, sensitivity analyses that varied the values of key cost drivers had little effect on the results. Secondly, the limited time horizon of the study meant that the follow-up of outcomes for both mother and baby did not extend beyond the time period of labour and care immediately after birth, or higher level postnatal or neonatal care when this was received. Perinatal events can result in associated longer term health and broader societal costs, as shown by the size of damages paid in obstetric litigation cases, which represent a substantial cost to the NHS.27 Follow-up over weeks or longer to monitor recovery, or a future assessment of the outcomes for mothers and babies at a later date, would act as a vehicle for estimating costs and consequences beyond the perinatal period and shed more light on long term cost effectiveness. Thirdly, this study used only clinically defined outcomes to determine the cost effectiveness of planned place of birth. A broader economic approach to the measurement of outcomes, such as stated preference discrete choice modelling, might have captured women’s preferences for alternative attributes of planned place of birth and might have been more informative to decision makers,28 but this was not practically possible given the anonymity involved in the study design and the available resources. Fourthly, and related, an attempt to value outcomes in terms of quality adjusted life years (QALYs) in preference to clinical endpoints should make the findings of this cost effectiveness research more relevant to decision makers for obstetric care in the NHS. The paucity of evidence for the longer term consequences of adverse events and other health outcomes after birth for both mother and baby remains and further research to generate combined QALY estimates for the linked mother-baby dyad should be a priority for research in this specialty. Finally, the remit of our research covered only intrapartum and immediate after birth care. Midwifery units also provide important aspects of antenatal care and postnatal care in the community, the cost effectiveness of which was not examined in our study.

Interpretation

Our economic evaluation broadly supports a policy of choice of planned place of birth for low risk women. This cost effectiveness information, however, should be considered in the light of an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcome associated with planned home birth in low risk nulliparous women. Our cost calculations are likely to be susceptible to changes in unit occupancy rates and relative cost effectiveness might alter accordingly. Moreover, the analysis presented here reflects cost effectiveness at the time of the Birthplace national prospective cohort study and the context of the NHS during that period. Should changes to the configuration of maternity services be planned to optimise cost effectiveness, then commissioners would have to consider the resource and related cost implications for the maternity services as a whole. This would require comprehensive economic assessments of the opportunity costs (that is, foregone benefits) associated with investments and disinvestments in alternative forms of provision of maternity services; this in turn will probably require economic modelling and forecasting of occupancy rates, overheads, patients’ safety, and transfer in view of fixed and variable costs.

What is already known on this topic

Robust evidence on the cost effectiveness of planned birth in alternative settings is lacking

What this study adds

Planned birth at home, in a free standing midwifery unit, or in an alongside midwifery unit generates incremental cost savings compared with planned birth in an obstetric unit

For nulliparous low risk women, planned birth at home generates incremental cost savings but increases adverse perinatal outcomes

For multiparous low risk women, planned birth at home generates incremental cost savings with no significant effect on adverse perinatal outcomes

For maternal outcomes, planned birth at home was the most cost effective option

The Birthplace in England Collaborative Group includes the wider group of coinvestigators, researchers, project staff, and coordinating midwives who contributed to the research programme. Members are listed in the cohort paper.12

Contributors: LS undertook all the economic analyses and contributed to the writing of the paper. SP led the study design and writing of the paper. NP collected the bulk of the unit cost data. JH was the Birthplace lead researcher who led the cohort study team and contributed to the study design, analyses, writing, and revisions of the paper. DP, PB, and MR contributed to the study design and the writing of the paper. PB was the chief investigator for Birthplace in England and had overall responsibility for the research programme. All members of the Birthplace in England Co-investigators Group contributed at various stages to the design and conduct of the economic evaluation and drafts of the paper. SP is guarantor.

Funding: This study was part of a larger study jointly funded by the Department of Health’s Policy Research Programme and the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme. The related study formed part of a project funded by the National Institute for Health Research Research for Patient Benefit Programme through grant PB-PG-0107-12209. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the funders.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;344:e2292

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: Resource use during intrapartum care

Appendix 2: Unit costs per resource item

Appendix 3: Cost per woman adjusted for sociodemographic and other factors: generalised linear regression

References

- 1.Campbell R, Macfarlane A. Where to be born? The debate and the evidence. 2nd ed. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, 1994.

- 2.Department of Health. National service framework for children, young people and maternity services. Standard 11: maternity services. Department of Health, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Department of Health. Improvement, expansion and reform—the next 3 years: priorities and planning framework 2003-2006. Department of Health, 2002.

- 4.De Jonge A, van der Goes BY, Ravelli AC, Amelink-Verburg MP, Mol BW, Nijhuis JG, et al. Perinatal mortality and morbidity in a nationwide cohort of 529,688 low-risk planned home and hospital births. BJOG 2009;116:1177-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen PA, Saxell L, Page LA, Klein MC, Liston RM, Lee SK. Outcomes of planned home birth with registered midwife versus planned hospital birth with midwife or physician. CMAJ 2009;181:377-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindgren HE, Radestad IJ, Christensson K, Hildingsson IM. Outcome of planned home births compared to hospital births in Sweden between 1992 and 2004. A population-based register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:751-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori R, Dougherty M, Whittle M. An estimation of intrapartum-related perinatal mortality rates for booked home births in England and Wales between 1994 and 2003. BJOG 2008;115:554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wax JR, Lucas FL, Lamont M, Pinette MG, Cartin A, Blackstone J. Maternal and newborn outcomes in planned home birth vs planned hospital births: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:243,e1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodnett ED, Downe S, Walsh D, Weston J. Alternative versus conventional institutional settings for birth. Cochrane Collaboration. Wiley, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gyte G, Dodwell M, Newburn M, Sandall J, Macfarlane A, Bewley S. Estimating intrapartum-related perinatal mortality rates for booked home births: when the “best” available data are not good enough. BJOG 2009;116:933-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NICE. Intrapartum care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health, RCOG, 2007.

- 12.Birthplace in England Collaborative Group. The Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study: perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth in “low risk” women. BMJ 2011;343:d7400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollowell J, Puddicombe D, Rowe R, Linsell L, Hardy P, Stewart M, et al. The birthplace national prospective cohort study: perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth. Birthplace in England research programme. Final report part 4. NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme, 2011.

- 14.Maternity Care Working Party. Making normal birth a reality. NCT, RCM, RCOG, 2007.

- 15.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. NICE, 2008. [PubMed]

- 16.Macfarlane A, Rocca L, Patel N, Schroeder L, Turner, et al. Assessing the impact of a new birth centre on choice and outcome of maternity care in an inner city area. Final report. NIHR Research for Patient Benefit Programme grant PB-PG-0107-12209. City University London, 2011.

- 17.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- 18.Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2010. Personal Social Services Research Unit, 2010.

- 19.National Health Service Litigation Authority. NHSLA factsheet 5. NHSLA, 2010.

- 20.British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British National Formulary. No 61. BMA, 2011.

- 21.National Health Service Supply Chain. NHS supply chain catalogue 2009. 2009. https://my.supplychain.nhs.uk/catalogue/browse/1/medical.

- 22.Department of Health. NHS reference costs 2008-2009. Appendix 4, NHS trusts and PCTs combined. Gateway reference 13456. Department of Health, 2010.

- 23.Thompson SG, Barber JA. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed? BMJ 2000;320:1197-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon PM. The bootstrap and the jackknife: describing the precision of ecological indices. In: Scheiner SM, Gurevitch J, eds. Design and analysis of ecological experiments. Chapman and Hall, 1993:290-318.

- 25.Schroeder L, Petrou S, Patel N, Hollowell J, Puddicombe D, Redshaw M, et al. Birthplace cost-effectiveness analysis of planned place of birth: individual level analysis. Final report part 5. NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme, 2011.

- 26.Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. The BMJ Economic Evaluation Working Party. BMJ 1996;313:275-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ungar W, ed. Economic evaluation in child health.Oxford University Press, 2009.

- 28.Petrou S, Henderson J. Preference-based approaches to measuring the benefits of perinatal care. Birth 2003;30:217-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Resource use during intrapartum care

Appendix 2: Unit costs per resource item

Appendix 3: Cost per woman adjusted for sociodemographic and other factors: generalised linear regression