Abstract

Identification of gene × environment interactions (GxE) for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a crucial component to understanding the mechanisms underpinning the disorder, as prior work indicates large genetic influences and numerous environmental risk factors. Building on prior research, children's appraisals of self-blame were examined as a psychosocial moderator of latent etiological influences on ADHD via biometric twin models, which provide an omnibus test of GxE while managing the potential confound of gene-environment correlation. Participants were 246 twin pairs (total n=492) ages 6–16 years. ADHD behaviors were assessed via mother report on the Child Behavior Checklist. To assess level of self-blame, each twin completed the Children's Perception of Inter-parental Conflict scale. Two biometric GxE models were fit to the data. The first model revealed a significant decrease in genetic effects and a significant increase in unique environmental influences on ADHD with increasing levels of self-blame. These results generally persisted even after controlling for confounding effects due to gene-environment correlation in the second model. Results suggest that appraisals of self-blame in relation to inter-parental conflict may act as a key moderator of etiological contributions to ADHD.

Keywords: Gene × environment interaction, Inter-parental conflict, Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most commonly diagnosed psychiatric disorders of childhood, affecting approximately 3–10% of school-aged children. Research regarding the etiology of ADHD has provided strong evidence of genetic influence, with heritability estimates ranging between 70 and 90% (Bergen et al. 2007; Burt 2009). In contrast to these high estimates of genetic influence, contributions from the environment appear to be much smaller (i.e., 10–30% of the variance; Burt 2009), and moreover, appear to be exclusively child-specific or non-shared environmental in origin (see meta-analyses by Bergen et al. 2007; Burt 2009; Nikolas and Burt 2010). As measurement error is also contained within the non-shared environmental proportion of variance, these environmental influences may or may not reflect actual environmental experiences that serve to differentiate siblings within a family. However, other work examining identical twin pairs discordant for ADHD found that the affected twin had significantly smaller caudate volume (Castellanos et al. 2003) and significantly lower birth weight and delayed physical and motor maturation compared to their unaffected co-twin (Lehn et al. 2007), suggesting that non-shared environmental influences on ADHD reflect more than simple errors of measurement.

A number of environmental variables have been identified as potentially important in this regard, including environmental toxicants, inter-parental conflict, parenting styles, and childhood maltreatment (Banerjee et al. 2007; Ellis and Nigg 2009; Nigg 2006; Nigg et al. 2010). That said, crucial questions remain regarding how to understand these relationships between environmental variables and ADHD within the context of large and robust estimates of genetic effects.

Gene × Environment Interactions and Behavioral Genetic Models

One possible answer involves gene × environment interactions (GxE), which involve modification of genetic influences by environmental risk and protective factors. That is, the genetic and biological processes involved in the development of ADHD may vary across different types of environmental exposures. These environments may then serve to “activate” the specific genetic and biological mechanisms underlying ADHD. Specifically, the effects of quantitative trait loci (QTL) involved in ADHD may be context-dependent, such that different loci, and/or the expression of genetic processes that influence the disorder vary across different environmental exposures, effectively resulting in environments “turning on and off” specific genetic mechanisms that increase liability for the disorder.

In line with this, recent theoretical advances within behavioral genetics (see Purcell 2002) have shown that the genetic (A) and non-shared environmental (E) variance components contain not only their respective main effects but also variance due to GxE effects. In particular, Purcell (2002) noted that there are two types of GxE interactions that are captured in the traditional behavioral genetic models. These include (1) genetic × shared environment interactions (or AxC), and (2) genetic × non-shared environment interactions (or AxE). Moreover, while the former are captured in the additive genetic variance term in traditional twin studies, the latter are captured in the non-shared environmental variance term.

The expansion of the traditional behavioral genetic biometric framework for understanding GxE has a number of key advantages. First, the application of this framework may be particularly relevant for ADHD, for which numerous environmental risk factors have been identified (Banerjee et al. 2007; Nigg 2006) even though the environmental component of variance in behavioral genetic studies is consistently small to moderate in magnitude. Second, it provides an omnibus test of GxE effects for a particular environmental variable, as genetic influences are examined at the latent or composite level of analysis. This advantage stands in contrast to the more specific molecular GxE analyses, which typically examine individual genetic polymorphisms (Langley et al. 2008; Waldman 2007) and are thus likely to be explaining only a very small part of the causal chain of polygenic disorders like ADHD. Finally, the biometric framework detailed above would provide critical new information regarding the specific manifestation of any GxE (i.e., AxC, AxE, or both) between the environmental moderator of interest and ADHD. In other words, if a given environmental variable is involved in the etiology of ADHD via GxE, the biometric framework would be able to clarify whether interactions occur at the family-level (e.g., AxC interactions) or at the child-specific level (e.g., AxE interactions) or both. Application of this methodology to ADHD can thus help us not only confirm the existence of GxE in ADHD, but also illuminate how environmental variables, interact with genetic risk for ADHD. With this methodology in mind, the next steps then involve selection of potential candidate moderators for tests of GxE effects on ADHD.

Selection of a Moderator

While numerous environmental variables have been identified for ADHD, those related to the family environment are of particular interest, given the key role of the family environment in the development of behavioral and emotional regulation capacities (Nigg et al. 2006). Marital conflict (or inter-parental conflict as it has been most recently termed) in particular has been shown to be a robust predictor of child adjustment and behavior problems (Buehler et al. 2007; Cummings and Davies 1994; Grych and Fincham 1990; Grych et al. 2000), including ADHD (Wymbs et al. 2008). Further, the topics of marital disputes are thought to be differentially related to children's reactions and behaviors, such that conflicts about the child are linked to greater behavioral dysregulation in the child than are other sources of inter-parental conflict (e.g., financial concerns; Cummings et al. 2002, 2004; Harold et al. 2004).

In line with this more child-centered perspective, it has also been suggested that youth perceptions and appraisals of inter-parental conflict play a critical determining role as to the effect of inter-parental conflict on youth behavior problems (Grych and Fincham 1990). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis examining the impact of youth appraisals of inter-parental conflict are significant predictors of both child internalizing and externalizing problems (Rhoades 2008). In regard to ADHD specifically, Counts and colleagues (2005) demonstrated that self-blame appraisals were robustly related to inattention and hyperactivity within a clinically-diagnosed sample of ADHD youth over and above a variety of other indicators of psychosocial risk, including parent psychopathology, socioeconomic status, and parenting stress.

Such findings thus provide a clear impetus for examining the relationship between self-blame and ADHD. Notably however, self-blame is conceptualized as a set of cognitive processes and may not therefore constitute purely “environmental” contributors (i.e., both genetic and environmental factors may be contributing to self-blame appraisals). In line with this, recent work has shown that many “environmental” variables implicated in psychopathology are, in part, influenced by genetic factors (Kendler and Baker 2007). Furthermore, examination of such “environmental exposures” have shown powerful GxE effects generally (i.e., stressful life events, see Caspi et al. 2003) and for ADHD specifically (i.e., psychosocial adversity, marital instability, see Retz et al. 2008; Waldman 2007). Self-blame then represents a potentially potent exposure that may interact with genetic risk in the development of ADHD.

The purpose of the current study was examine how youth appraisals of self-blame in relation to inter-parental conflict influence the magnitude of genetic and environmental contributions to ADHD. We specifically examined how the genetic, shared, and non-shared environmental variance components of ADHD shifted in magnitude as a function of the extent to which children blamed themselves for their parent's conflicts. Evidence of shifts in genetic and environmental contributions to ADHD by self-blame may provide some initial evidence regarding the role of self-blame in the underlying causes of ADHD behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants were child and adolescent twin pairs from the Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR), an ongoing project examining genetic and environmental contributions to internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (Klump and Burt 2006). Participants were recruited through state birth records in collaboration with the Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH) and the Michigan Bureau of Integration, Information, and Planning Services (MBIIP; for a full description of recruitment procedures for the MSUTR, see Klump and Burt 2006). Recruitment for the MSUTR is ongoing, but the current response rate is 61%. Parents gave informed consent for both themselves and their children and children provided informed assent. All research protocol was approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board.

The current sample consisted of 246 6- to 16-year-old child and adolescent monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs (total n=492 twins). This sample was composed of 120 MZ twin pairs (55 male-male, 65 female-female) and 126 DZ twin pairs (69 male-male, 57 female-female) that ranged in age from 5 to 16 years (M=10.2, SD= 2.6 years). Mothers ranged in age from 28 to 60 years (M= 41.7 years, SD=5.3 years). Participating families in the MSUTR were representative of individuals living in the mid-Michigan region in terms of racial identification (see Culbert et al. 2008). Gross annual income was coded on an ordinal scale and was distributed within the sample as follows: under $20,000 (8.5%), $20,000–$40,000 (13.4%), $40,000–$60,000 (17.9%), $60,000–%80,000 (17.1%), $80,000–$100,000 (13.8%), and $100,000 or over (29.3%).

Zygosity Determination

Zygosity was established using physical similarity questionnaires administered to the twins’ primary caregiver (Peeters et al. 1998), as well as a research assistant who independently evaluated the twins on physical similarity indices. Zygosities were then compared between the participant and research assistant reports. Discrepancies were resolved through review of questionnaire data and twin photographs (when available) by one of the MSUTR principal investigators (KLK or SAB) or by DNA markers. On average, the physical similarity questionnaires used by the MSUTR have accuracy rates of 95% or better when compared to other methods (Peeters et al. 1998). Because of their high validity in assigning zygosity and their low-cost and ease of administration to large samples, physical similarities questionnaires, like the one used in the current study, are one of the most common methods for determining zygosity within the field of behavioral genetics (Iacono et al. 1999; Kaprio et al. 1978; Levy et al. 1997; Lichentenstein et al. 2002; Rietveld et al. 2000). Importantly, misclassification of zygosity via physical similarities questionnaires would serve to decrease estimates of A and would thus attenuate all estimates of GxE effects.

ADHD Behaviors

Mothers of the twin participants completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) to assess behaviors relating to ADHD. Mothers rated how often particular behaviors occurred during the past 6 months in each twin using a 3-point Likert scale (0=never true; 1=sometimes/somewhat true; 2=often true). The 7-item DSM-oriented scale for ADHD was selected for our analyses since its items were chosen to closely map onto DSM-IV criteria for ADHD. The items included “fails to finish things he/she starts,” “can't sit still, restless or hyperactive”, “impulsive or acts without thinking”. The CBCL has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). Additionally, receiver-operator characteristic analyses have shown the CBCL to be a robust predictor of clinically-diagnosed ADHD (Hudziak et al. 2004). Internal consistency estimates in the current sample were adequate (α=0.88).

While age and sex based norms are available for CBCL scores, the raw scores for the DSM-ADHD scale were used in the current study, as recommended by the authors (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). Thus, the ADHD measure for each twin was the total raw score added across the seven ADHD items. The ADHD raw score was log-transformed prior to analysis in order to better approximately normality (skew following transformation=−0.13), as skewness may result in distorted estimates of moderation in the GxE analyses (Purcell 2002). Additionally, the current sample was underpowered to example estimates separately by age and sex. The ADHD scale was then regressed on age and sex prior to analyses. The final score (with age and sex covaried) were then used in all model-fitting analyses (McGue and Bouchard 1984).

Perceptions of Inter-parental Conflict

Appraisals of inter-parental conflict were assessed with the Children's Perception of Inter-parental Conflict scale (CPIC; Grych et al. 1992). Each twin completed a separate CPIC. The 48 CPIC items were rated by participating twins on a three-point scale (1–3: true, sort of true, and false). Children completed the CPIC if they either: (1) lived with both biological parents, (2) lived with one biological parent/guardian and a step-parent or other co-habitating adult, or (3) lived with one biological parent but had frequent contact with their other parent and often observed interactions between their parents to complete the CPIC. Children who had never lived with or interacted with a second parent or no longer had meaningful contact with a second parental figure were not included in the study (n=9 twin pairs). Of the included twin pairs, there were no differences between twins living in one-parent homes versus two-parent homes in terms of age, sex, or ethnicity (all ps>0.21) as well as in self-blame (p=0.38).

Because the CPIC was designed to be completed by school-aged children, the questionnaire was read to participating twins who were currently in the 5th grade or younger, or whose reading level was found to be lower than the 5th grade on a brief reading screen (Torgesen et al. 1999). Based on exploratory and confirmatory analysis (Nigg et al. 2009), four empirically derived scale scores were computed—the main scale of interest being the 9-item self-blame scale. Sample items from the CPIC self-blame scale include “My parents usually argue about something that I do” or “It is usually my fault when my parents argue.” Internal consistency measures were adequate (α=0.85).

Because our GxE analyses estimate genetic and environmental influences at each level of the moderator, small cell sizes across the range of continuous values of the moderator (i.e., self-blame scores ranged from 9 to 27) would result in imprecise estimates of genetic and environmental influences (Purcell 2002). As a result, several data preparation steps were necessary to complete the analyses. Data were first trichotomized into low, moderate, and high levels of self-blame, so as to more meaningfully estimate genetic and environmental effects at each broad level of self-blame. A trichotomized scale was favored here to maximize power for estimating genetic and environmental influences by placing a minimum of 100 twins within each level (low/medium/high). The lowest third of the distribution was assigned a score of zero (n=128, M self-blame score on floored scale=0); the middle third was assigned a score of 1 (n=156, M=2.1, SD=1.6), and the highest third was assigned a score of 2 (n=175, M=3.7, SD=1.9). This trichotomized self-blame variable was used in all model-fitting analyses.1

Data Analyses

Behavioral genetic analyses make use of the difference in the proportion of genes shared between reared-together siblings. Utilizing these differences, the variance within observed behaviors is partitioned into three components: additive genetic, shared environment, and non-shared environment plus measurement error. The additive genetic component (A) is the effect of individual genes summed over loci and any AxC, and acts to increase twin correlations relative to the amount of genes shared. The shared environment (C) is that part of the environment common to siblings that acts to make them similar to each other. The non-shared environment (E) encompasses environmental factors (and measurement error) differentiating twins within a pair, as well as any AxE.

GxE Models Whereas GxE may be characterized as psychosocial sensitivity to genetic risk, gene-environment correlation (rGE) represents genetic control of exposure to different environments. For example, a child with ADHD may be more likely to evoke conflict between his or her parents (Whalen and Henker 1999), and thus be more likely to attribute blame regarding this conflict to him or herself. Thus, a child's genetic proclivities could elicit an response that is consistent with his/her genetic make-up (referred to as an evocative rGE). rGE can resemble GxE in moderator models and represents an important confound (i.e., genetic influences on ADHD could vary across levels of self-blame because the “moderator” is correlated with genetic risk for ADHD).

Given this, Purcell (2002) proposed two GxE models: the first model examines GxE regardless of rGE (i.e., “straight” GxE model); the second model examines GxE in the presence of rGE. In order to test for GxE effects while also considering the possible impact of rGE, we conducted two sets of analyses. We first examined the univariate or “straight GxE” model to estimate genetic and environmental influences on ADHD at each level of the moderator. This model provides a test of GxE but does not allow us to consider possible genetic overlap between the moderator and the outcome. Next, we conducted the GxE in the presence of rGE model, thereby allowing us to both confirm the presence of GxE, and evaluate the impact of rGE on these effects. It is important to note that the “straight” GxE and the GxE in the presence of rGE models are not nested, and thus their results cannot be statistically compared. However, conceptual comparisons of the results could prove useful for furthering our understanding of the issues mentioned above.

The “straight” GxE model encompasses three nested moderator models. The first and least restrictive model allows for both linear and non-linear moderation of the genetic, shared, and non-shared environmental contributions (i.e., a, c, e) to ADHD. At each level of self-blame, linear (i.e., A1, C1, E1) and non-linear (i.e., A2, C2, E2) moderators are added to these genetic and environmental paths using the following equation: Unstandardized VarianceTotal = (a + A1(self – blame) + A2(self – blame2))2+(c + C1(self – blame) + C2(self – blame2))2 + (e + E1(self – blame) + E2(self – blame2))2. We then fit a series of more restrictive moderator models, constraining the moderators for each source of etiological influence to be zero and evaluating the reduction in model fit. As recommended (Purcell 2002), the current models were run a minimum of 5 times using multiple start values to ensure that all the estimates obtained minimized the −2lnL value.

We next evaluated GxE effects while accounting for rGE. This GxE in the presence of rGE model is essentially a reformulation of the standard behavioral genetic bivariate model, such that the moderator is entered twice—as a dependent variable and as a moderator variable. Influences on ADHD are then partitioned into two sources of genetic influence (as well as two sources of shared and two sources of non-shared environmental influence): (1) variance shared with the moderator, and (2) variance that is unique to ADHD (i.e., that residual variance in ADHD that does not overlap with self-blame). The moderator (i.e., self-blame) is then allowed to moderate both the genetic and environmental covariance paths between self-blame and ADHD as well as with the genetic and environmental paths unique to ADHD (Purcell 2002). Only the latter index “true” GxE (i.e., controlling for rGE).

Mx (Neale et al. 2003) was used to fit models to the transformed raw data. Because these interaction models effectively involve fitting a separate biometric model for each individual as a function of their self-blame score, they both require the use of Full-Information Maximum-Likelihood raw data techniques (FIML). Missing data was generally low for this sample (less than 6.8%). Morevoer, missingness (data coded as present versus absent for the ADHD and CPIC self-blame scores) was unrelated to family constellation, age of twins, age of mother, parental education, or parental income (all ps>0.31). FIML raw data techniques produce less biased and more consistent estimates than do other techniques, such as pairwise or listwise deletion (Little and Rubin 1987). FIML assumes that the data are missing at random and are thus ignorable.

When fitting models to raw data, variances, covariances, and means of those data are first freely estimated by minimizing minus twice the log-likelihood (−2lnL). For the “straight” GxE model, the minimized value of −2lnL in the full moderation model is compared with the −2lnL obtained in more restrictive moderator models to yield a likelihood-ratio χ2 test for the significance of the moderator effects. Non-significant changes in chi-square indicate that while both models fit the data equally well, preference is given to the more restrictive model (i.e., that model with fewer parameters and thus more degrees of freedom), as it does not result in a significant reduction in fit. The chi-square was then converted to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) so as to measure model fit relative to parsimony. The lowest BIC among a series of nested models is considered best. BIC was used to determine the best-fitting model as it is one of the most commonly used indices within the field of behavioral genetics (Markon and Krueger 2004) and because it weighs parsimony most heavily.

Results

Intraclass Correlations

Intraclass correlations were first compared across MZ and DZ pairs in order to preliminary gauge the relative influence of genetic and environmental influences on ADHD (see Table 1). For the overall sample, the MZ correlation was significantly greater than the DZ correlation and therefore highly suggestive of genetic influences on ADHD. In order to assess potential moderation of genetic and environmental influences on ADHD by self-blame, we also examined intraclass correlations at various levels of self-blame. To do so, we restricted analyses to those twin pairs who were concordant for moderator level; the sample sizes are thus small relative to the overall sample. Of note, while twins are required to be concordant on the moderator to examine potential etiological moderation using intraclass correlations, twins do not have to be concordant on the value of the moderator when using structural equation modeling techniques in Mx (and thus the full sample was used for all subsequent analyses).

Table 1.

Twin intraclass correlations for mother-rated CBCL ADHD score and self-blame: overall and by level of CPIC self-blame

| MZ | DZ | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||

| ADHD score | 0.55** | 0.15* |

| Self-blame | 0.32* | 0.17* |

| By Level of CPIC Self-Blame | ||

| CPIC Self-Blame: LOW (N=66) | 0.80** | 0.21* |

| CPIC Self-Blame: MODERATE (N=24) | 0.52* | 0.04 |

| CPIC Self-Blame: HIGH (N=36) | 0.10 | 0.01 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

Results indicate that when both twins reported low levels of self-blame, the MZ-DZ correlation difference, and thus the estimate of genetic influences, was large. As reports of self-blame increased, the DZ correlation dropped moderately, whereas the MZ correlation decreased substantially. The decreasing difference between the MZ and DZ correlations implies that genetic influences may decrease with increasing self-blame. Moreover, the decreasing MZ correlation implies that non-shared environmental influences increase with increasing levels of self-blame. Such results collectively suggest that self-blame may indeed act to moderate genetic and environmental influences on ADHD.

Additionally, cross-twin, cross-trait correlations were also computed to examine the overlap between self-blame and ADHD (which would point toward potential rGE). Results indicated small but significant cross-twin cross-trait correlations for both MZ (r=0.18, p<0.05) and DZ twins (r=0.15, p<0.05), indicating potential rGE effects.

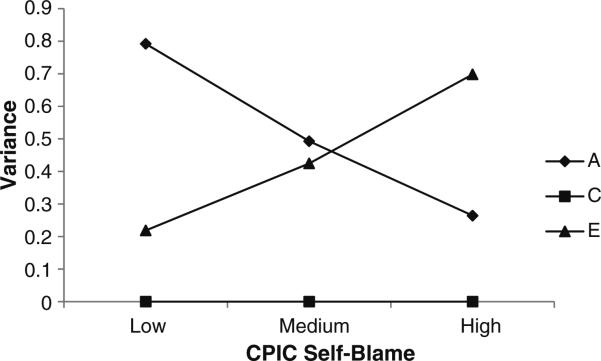

“Straight” GxE Analyses

Test statistics for the “straight” GxE analyses are reported in Table 2. Results indicated that the linear moderation model best fit the data. Thus, self-blame appears to be a significant linear moderator of the genetic and environmental contributions to ADHD. In order to examine the nature of this etiological moderation, we used the estimated paths and moderators from the best-fitting linear model (see Table 3) to calculate and plot the unstandardized genetic, shared, and non-shared environmental variance components at each level of self-blame. Unstandardized parameter estimates are favored here in order to examine absolute (rather than proportional) shifts in each parameter across each level of the moderator (as recommended by Purcell 2002). Figure 1 displays the unstandardized estimates of genetic, shared, and non-shared environmental variance components for ADHD at different levels of self-blame. As seen there, when self-blame scores are low, genetic influences on ADHD are quite large, with small to moderate contributions from the non-shared environment. As self-blame scores increase, however, the absolute genetic variance appears to decline sharply, whereas the unique environmental variance appears to increase substantially. Moreover, as indicated by moderator estimates whose confidence intervals do not overlap with zero (see Table 3), both the increase in non-shared environmental factors and the decrease in genetic factors were statistically significant.

Table 2.

Fit statistics for nested “straight” GxE models

| Model | –2lnL | df | Δ χ2 | Δ df | p | BIC | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-linear | 1143.019 | 413 | NA | NA | NA | –534.626 | 0.06 |

| Linear | 1143.604 | 416 | 0.585 | 3 | 0.90 | –550.374 | 0.04 |

| Main effects | 1154.187 | 419 | 10.58 | 3 | 0.014 | –542.368 | 0.06 |

In the main effects model, genetic, shared, and non-shared environmental parameter estimates do not vary by self-blame. In the linear model, genetic and environmental parameter estimates vary linearly. In the non-linear model, parameter estimates vary linearly and quadratically. Each model is compared with the preceding model when calculating the change in χ2 and degrees of freedom. Non-significant changes in chi-square indicate that the more restrictive model (i.e., that model with fewer estimated parameters and therefore more degrees of freedom) provides a better fit to the data. Lower or more negative values of BIC also indicate the best-fitting model. By these criteria, the linear moderation model fit the data best

Table 3.

Unstandardized path and moderator estimates in the best-fitting “Straight” GxE model

| Paths |

Linear |

Quadratic |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | c | e | A1 | C1 | E1 | A2 | C2 | E2 |

| ADHD | ||||||||

| 0.890* (0.634, 1.07) | 0.000 (–0.546, 0.546) | 0.468* (0.323, 0.673) | -0.188* (–0.369,–0.013) | 0.000 (–0.354, 0.354) | 0.184* (0.043, 0.301) | – | – | – |

Paths and moderators are presented; their 95% confidence intervals are presented below them in brackets. A, C, and E (both upper and lower case) represent genetic, shared, and non-shared environmental parameters, respectively. In the left portion of the table, the path estimates (i.e., a, c, and e) are presented. Because self-blame was trichotomized and those with scores within the lowest third of the distribution were coded as zero, these estimates function as intercepts. Accordingly, the genetic and environmental variance components at low levels of self-blame can be obtained simply by squaring these path estimates. At each subsequent level of self-blame, significant linear (i.e., A1, C1, E1) moderators were added to these genetic and environmental paths using the following equation: . The variance component estimates calculated this way are presented in Fig. 1. The quadratic moderation terms (e.g., A2, C2, E2) are not included as the linear model provided the best fit to the data (and are thus zero in the above equation).

indicates that the estimate is statistically significant at p<0.05

Fig. 1.

Unstandardized Genetic (A), Shared Environmental (C), and Non-Shared Environmental Variance Contributions to ADHD by Level of Self-Blame: “Straight” GxE Model. Note. Moderation analyses revealed that the increase in unique environmental contributions to the variance in ADHD (E) was significant. In addition, the decrease in genetic contributions to ADHD with increasing levels of self-blame was also significant

GxE in the Presence of rGE

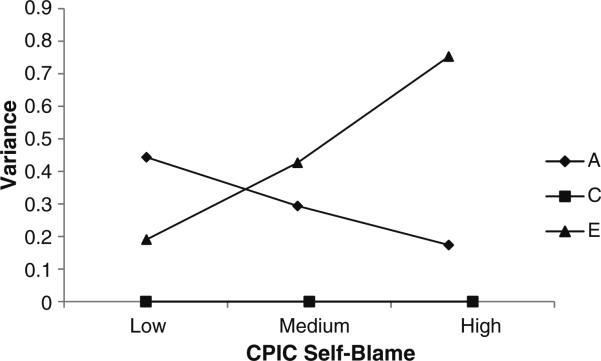

We next examined GxE while also considering potential rGE confounds. In this model, the moderator (self-blame) is entered twice so that it can be examined as both a dependent variable and as a linear moderator (see Fig. 2). Moderation is estimated for the genetic and environmental overlap between self-blame and ADHD (i.e., the covariance paths) as well as for the genetic and environmental contributions to ADHD that do not overlap with those for self-blame. The key estimates of interest in the current study involve the latter (i.e., those effects unique to ADHD).

Fig. 2.

Unstandardized Genetic (A), Shared Environmental (C), and Non-Shared Environmental Variance Contributions to ADHD by Level of Self-Blame: GxE in the Presence of rGE Model. Note. Moderation analyses revealed that the increase in unique environmental contributions to the variance in ADHD (E) was significant. The decrease in genetic contributions to ADHD with increasing levels of self-blame was only significant when all shared environmental paths (C) were constrained to be zero

The full ACE GxE in the presence of rGE model provided an adequate fit to the data (−2lnL=2109.682, df=831, BIC=−1170.821, RMSEA <0.001), as indicated by the negative BIC value. The resultant path estimates and moderators for this model are presented in Table 4. Importantly, self-blame was predominately influenced by non-shared environmental factors, accounting for 72% of the variance. The remaining variance was due to genetic factors, a portion of which overlapped with ADHD (path estimate=0.489, p<0.05). Such findings indicate that there is significant genetic overlap between self-blame and ADHD (i.e., rGE) which may be influencing our previously observed “GxE”.

Table 4.

Unstandardized path and moderator estimates for the GxE in the presence of rGE model

| Paths |

Linear moderation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | c | e | A1 | C1 | E1 |

| Covariance (or overlap) between ADHD and self-blame | |||||

| 0.489* (0.024, 0.798) | 0.325 (–0.715, 0.715) | 0.014 (–0.230, 0.205) | 0.003 (–0.289, 0.353) | –0.243 (–0.451, 0.451) | 0.101 (.–0.067, 0.273) |

| Variance unique to ADHD | |||||

| 0.636* (0.287, 0.886) | 0.000 (–0.663, 0.663) | 0.426* (0.303, 0.598) | –0.115 (–0.347, 0.347) | 0.000 (–0.335, 0.335) | 0.200* (0.079, 0.303) |

Paths and moderators are presented; their 95% confidence intervals are presented below them in brackets. A, C, and E (both upper and lower case) represent genetic, shared, and non-shared environmental parameters, respectively. In the left portion of the table, the path estimates (i.e., a, c, and e) are presented. Because self-blame was divided into tertiles and those with scores within the lowest third of the distribution were coded as zero, these estimates function as intercepts. Accordingly, the genetic and environmental variance components at low levels of self-blame can be obtained simply by squaring these path estimates. At each subsequent level of self-blame, significant linear (i.e., A1, C1, E1) moderators are added to these genetic and environmental paths using the following equation: . The variance component estimates calculated this way are presented in Fig. 2.

indicates that the estimate is statistically significant at p<0.05

In order to rule out this possibility, we next examined etiological moderation of that variance that is unique to ADHD. Importantly, results were generally similar to those reported above. Examination of the confidence intervals revealed significant contributions from both genetic and non-shared environmental factors to ADHD at low levels of self-blame. However, the more children blamed themselves for their parent's conflict, the more these genetic contributions decreased. Although this overall pattern replicates that from the prior model, the effect was clearly more muted than in the prior model (and was no longer significantly greater than zero, as seen by the non-significant A1 value in Table 4). Non-shared environmental influences on ADHD continued to increase substantially (and significantly so) with increasing levels of self-blame (see Fig. 2).

As can be seen in Fig. 2, the shared environmental path estimates as well as moderation paths of the shared environmental variance unique to ADHD were all estimated to be zero. Thus, we re-ran the rGE in the presence of GxE model fixing all the shared environmental paths to zero. Fixing these paths resulted in a slight improvement in fit, as indicated by the more negative BIC value (−2lnL=2119.733, df=836, BIC=−1179.328, RMSEA <0.001). Unsurprisingly, the moderation of E remained significant when C was constrained to be zero. However, moderation of the unique genetic variance in ADHD was once more statistically significant, results that are likely a function of the tightened confidence intervals following the dropping of five paths, especially given our small sample size. Such results indicate that there may be some (albeit small-to-moderate) moderation of genetic effects on ADHD by self-blame even after controlling for rGE.

Evaluating the Impact of Comorbidity

Due to the high rates of co-occurrence between ADHD and other child behavior disorders, additional analyses were conducted to examine the potential impact of comorbidity on the current findings. That is, we evaluated if the effects that emerged in the current study are specific to ADHD. Two strategies were implemented: first, we re-examined both GxE models after removing cases with CBCL scores in the clinical range (i.e., T>65) on the DSM-IV ADHD scale and an additional DSM-IV scale, including the DSM-IV Oppositional Defiant Disorder scale (ODD, n=24), Conduct Disorder scale (CD, n=22), and the Anxiety Disorder scale (n=3). Removal of these cases did not impact the model-fitting results or the pattern of GxE effects.

Secondly, we re-examined the GxE models after regressing the ADHD score on the other CD DSM-IV scale scores (i.e., ODD, CD, and Anxiety) in order to parse out the overlapping variance. Model results were largely similar, however, the decrease in genetic effects observed in both GxE models was no longer significant. However, the increase in non-shared environmental influences observed at high levels of self-blame remained significant, indicating that this effect may be specific to ADHD.

Discussion

Despite high estimates of genetic effects for ADHD, prior research has consistently demonstrated that the variables related to the family environment and particularly those regarding the role of inter-parental conflict, remain important predictors of ADHD. The aim of the current study was to investigate self-blame as a moderator of genetic and environmental influences on ADHD. Results indicated that non-shared environmental influences on ADHD increase with higher levels of self-blame, while genetic influences on ADHD decrease. These results persisted even when controlling for potential rGE effects. Results indicated that the contribution of non-shared environmental factors to ADHD continued to significantly and substantially increase with increasing levels of self-blame. The decrease in genetic contributions to ADHD with increasing levels of self-blame also persisted somewhat (although only significantly so when shared environmental effects were constrained to be zero).

This caveat regarding the significance of decreases in genetic effects in the rGE model deserves some additional comment. We suspect this difference is likely due to differences in the absolute value of genetic variance in ADHD across the two models. As can be seen from Figs. 1 and 2, the absolute level of genetic variance within ADHD appears to be smaller after accounting for genetic overlap between ADHD and self-blame (using a visual comparison only, since the two models are not nested and thus cannot be statistically compared). This conclusion is also bolstered by the bivariate results indicating significant genetic correlation between self-blame and ADHD. Importantly, however, even when taking into account this genetic overlap, the moderation on the unique environmental effects for ADHD by self-blame remained significant.

The notion of a risk factor reducing genetic effects on ADHD stands in contrast to many previous reports of GxE effects, which have reported increased risk for the disorder within particular environmental contexts (Todd and Neuman 2007; Waldman 2007). While it remains unclear what accounts for these discrepancies, one possibility is that self-blame simply functions differently than other risk factors. This possibility is bolstered by previous work on GxE in personality, which found that for some environmental risk factors, higher levels of risk may actually attenuate as opposed to enhance genetic influences (Burt 2008). That is, some (particularly potent) risk factors may act as etiological “main effects”, with relatively little or no contribution from genetic factors. This may be particularly true for psychosocial risk factors, like self-blame, which likely reflect the proximal end result of multiple risk processes.

While the notion of environmental “main effects” remains important, it is also noteworthy that even as non-shared environmental influences on ADHD increased at higher levels of self-blame, genetic contributions to ADHD behaviors remained significant. In short, even with higher levels of influence from non-shared environmental factors, the genetic contribution to ADHD behaviors remained significantly different from zero. This result may indicate that among the multiple genes influencing ADHD, some may be involved in GxE processes, whereas others may continue to exert a main effect on ADHD regardless of the level of environmental risk.

While our results require replication, the current project was strengthened by several factors. First, self-blame regarding inter-parental conflict was assessed from the child's perspective. This is advantageous both because the child's understanding of inter-parental conflict has been shown more predictive of child adjustment problems than parental report of inter-parental conflict (Cummings and Davies 1994; Cummings et al. 1994), but also because our use of child self-reports for the moderator allowed us to circumvent shared informant variance (since we examined maternal-reports of ADHD). Moreover, because each child reported on his or her own self-blame, the moderator was free to vary across twins, allowing us to examine and control for possible rGE. This explicit examination of rGE provides additional assurances that the GxE effects observed here are “real” (or at least not due to rGE). Similar analyses would not be possible if only parent report were used, as parental reports of their own conflict would not vary across twins. This represents an important step forward in behavioral genetic modeling of GxE effects.

Implications

The results of the current study demonstrate that when children blame themselves for their parent's conflict, genetic influences on ADHD are less important. This finding suggests that the large genetic influences previously reported for ADHD may vary, at least somewhat, as a function of the level of psychosocial risk. One possible explanation for these findings is that genetic influences are more likely to be expressed as main effects in the absence of psychosocial challenges (see Burt 2008). Future molecular GxE investigations of ADHD may thus benefit from examining the strength of association between genetic markers and ADHD in a low-risk environmental context.

Next, our results indicated that non-shared environmental influences on ADHD are enhanced when children blame themselves for their parents’ conflicts. Several potential processes may be underlying this result. First, this effect may reflect an overall increase in the importance of unique environmental factors on ADHD. This idea is consistent with prior work demonstrating that individual environmental risk factors are not as predictive of child psychopathology as are the aggregate of multiple environmental risk factors (Rutter 1999). For example, youth reporting higher levels of self-blame may also experience greater conflict with their parents as well as may experience more inconsistent discipline from parents, both of which have been linked to ADHD.

A second possible explanation for the increase in non-shared environmental variance is that contributions from AxE to ADHD are potentiated at high levels of self-blame. As illustrated earlier, AxE load on the unique environmental variance component. This increase in E may thus be signaling additional child-specific interactional processes that are influencing ADHD behaviors. This explanation is consistent with developmental and family process research that has documented biological, psychological, and emotional changes in children who report high levels of self-blame and threat in relation to inter-parental conflict (Rhoades 2008). Lastly, the increase in E observed at higher levels of self-blame may actually reflect an increase in measurement error of parent-reports of ADHD symptoms, as error also loads on the non-shared environmental variance term. While unlikely that all effects are solely due to measurement error, extension of findings to additional informants would aid in ruling-out this possibility.

Furthermore, due to the use of child-reports of self-blame, we were able to estimate and control for effects due to rGE, including potential evocative rGE (i.e., children with higher levels of ADHD behaviors may cause greater conflict among parents, which in turn, leads to higher levels of self-blame in children). Although we could not directly test this evocative process per se, the GxE in the presence of rGE model was able to control for any potential effects due to rGE in general, including effects that may be due to the evocative rGE process described above. In fact, we did find evidence of genetic overlap between self-blame and ADHD, indicating the potential possibility of evocative rGE. However, greater in-depth examination of the developmental relationships between self-blame appraisals and ADHD may be of particular importance given the current findings.

The findings of the current study also shed light on how “environmental” variables may be conceptualized in tests of GxE effects. Self-blame appraisals were predominately influenced by non-shared environmental factors (72%), with additional and significant genetic influences as well (28%). Such findings are in line with a recent review indicating that many “environmental” risk factors are, in part, influenced by genes (Kendler and Baker 2007). Future work examining the interplay of genetic and environmental factors thus has great potential to elucidate the mechanisms by which both biological and psychosocial processes contribute to the etiology of complex behavioral phenotypes, such as ADHD.

Lastly, study results point to a potentially important role of environmental factors in the etiology of ADHD. In line with previous work, we found negligible shared environmental main effects for ADHD (Bergen et al. 2007; Burt 2009, 2010; Nikolas and Burt 2010), but uncovered a potentially important role of non-shared environmental factors for the disorder. Despite the absence of shared environmental main effects, these variables may continue to operate for ADHD via AxC. Future GxE studies which examine the role of environmental factors (both shared and non-shared) via behavioral genetic modeling may offer great benefits for understanding the specific etiological function of different environmental exposures in the development of ADHD and other disorders.

Limitations

There are some limitations of the current work that are important to note. Our sample was underpowered to examine estimates of latent genetic and environmental influences by sex or by age. As a result, we regressed the effects of sex and age out of ADHD prior to analysis (a common practice in the field of behavioral genetics; see McGue and Bouchard 1984). Future work should seek to examine potential sex-specific and age-specific or developmental effects in a larger sample. Additionally, our analyses required categorization of self-blame into tertiles. Although results were consistent when using dichotomous and quartile parsings, our sample was underpowered to examine moderation at each individual self-blame score.

Further, our study examined the DSM-oriented ADHD scale on the CBCL rather than DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD. While high scores on DSM ADHD scale have been shown to align with diagnosis of ADHD (Hudziak et al. 2004), the use of the CBCL limited our ability to examine ADHD symptom dimensions separately (i.e., inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity). This may be of particular importance given recent findings signaling etiological differences between ADHD symptom dimensions (Martel and Nigg 2006; Nikolas and Burt 2010; Sonuga-Barke 2005). Additionally, our sample was restricted to the use of the DSM ADHD scale on the CBCL and therefore did not include comprehensive assessment of ADHD (e.g., use of multiple informants, evaluation of clinical comorbidities). Future work aiming to replicate these findings would benefit from the use of teacher ratings as well as examining whether GxE effects are specific to ADHD or common across a variety of clinical comorbidities. Parsing out the variance due to other symptom dimensions and disorders using regression prior to biometric model fitting may be particularly helpful in future behavioral genetic studies of GxE effects.

Similarly, the majority of our participants were Caucasian; thus, the generalizability of our findings regarding self-blame appraisals to other cultures and societies requires further investigation. Furthermore, our study, like all behavioral genetic investigations, relies on the Equal Environments Assumption, which posits that identical twins reared together are no more likely to share environments than are fraternal twins reared together. This assumption has been examined and validated for numerous phenotypes (Plomin et al. 2008), including ADHD (Cronk et al. 2002). Even so, the Equal Environments Assumption remains an assumption and thus a potential limitation to our findings.

Lastly, our study relied in part on the GxE in the presence of rGE model advanced by Purcell (2002). The mathematical accuracy of this model has recently been scrutinized by Rathouz and colleagues (2008), who suggested that a correlated factors model was more appropriate for examining GxE in the presence of high levels of rGE (although this model has yet to be thoroughly tested). At this time, it remains unclear whether small-to-moderate levels of rGE (such as those examined here) influence GxE estimates using the Purcell (2002) model (Rathouz, personal communication, July, 2009); future studies are planned to examine this possibility. Regardless, our results are not likely to be a function of any potential problems with the Purcell (2002) rGE model, as our conclusions extended to the univariate or “straight GxE” model results as well (which is not affected by the potential problems noted by Rathouz et al. 2008).

Conclusions

In sum, the data convincingly showed that negative cognitive appraisals (e.g. self-blame) made by children in relation to inter-parental conflict enhanced non-shared environmental contributions but reduced genetic contributions to ADHD. Such findings not only support additional examinations of family factors as moderators of genetic and environmental contributions to ADHD, but also highlight the need for an evaluation of self-blame as a moderator of genetic risk in molecular genetic GxE studies of ADHD.

Footnotes

Model fitting was examined using two additional data preparation strategies when parsing the CPIC self-blame scores (e.g., dichotomous, quartiles). In both cases, the same pattern of results emerged, indicating that findings are robust to data preparation strategy.

Contributor Information

Molly Nikolas, Department of Psychology, University of Iowa, E112 SSH, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA molly-nikolas@uiowa.edu.

Kelly L. Klump, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, 107B Psychology Building, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA klump@msu.edu

S. Alexandra Burt, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, 107D Psychology Building, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA burts@msu.edu.

References

- Achenbach T, Rescorla LA. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 2001 profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee TD, Middleton F, Faraone SV. Environmental risk factors for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96:1269–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen SE, Gardner CO, Kendler KS. Age-related changes in heritability of behavioral phenotypes over adolescence and young adulthood: a meta-analysis. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:423–433. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Lange G, Franck KL. Adolescents’ cognitive and emotional responses to marital hostility. Child Development. 2007;78:775–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Gene-environment interactions and their impact on the development of personality traits. Psychiatry. 2008;7:507–510. [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: a meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:608–637. doi: 10.1037/a0015702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Are there shared environmental influences on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? Reply to Wood, Buitelaar, Rijsdijk, Asherson, and Kuntsi (2010). Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:341–343. doi: 10.1037/a0019116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Sharp WS, Gottesman RF, Greenstein DK, Giedd JN, Rapoport JL. Anatomic brain abnormalities in monozygotic twins discordant for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1693–1696. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counts CA, Nigg JT, Stawicki JA, Rappley MD, Von Eye A. Family adversity in DSM-IV ADHD combined and Inattentive subtypes as associated disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:690–698. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000162582.87710.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronk NJ, Slutske WS, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Reich W, Heath AC. Emotional and behavioral problems among female twins: an evaluation of the equal environments assumption. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:829–837. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KC, Breedlove SM, Burt SA, Klump KL. Prenatal hormone exposure and risk for eating disorders: a comparison of opposite-sex and same-sex twins. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:329–336. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Children and marital conflict: The impact of marital dispute and resolution. The Guilford Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Simpson KS. Marital conflict, gender, children's appraisals, and coping efficacy as mediators of child adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM, Dukewich T. Children's responses to mother's and father's emotionality and tactics in marital conflict in the home. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:478–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM. Everyday marital conflict and child aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:191–202. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019770.13216.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis B, Nigg JT. Parenting practices and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: partial specificity of effects. Journalofthe American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:146–154. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819176d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children's adjustment: a cognitive contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Seid M, Fincham FD. Assessing marital conflict from the child's perspective: the Children's Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Development. 1992;63:558–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD, Jouriles EN, McDonald RN. Interparental conflict and child adjustment: testing the mediational role of appraisals in the cognitive-contextual framework. Child Development. 2000;71:1648–1661. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Shelton KH, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Marital conflict, child emotional security about family relationships, and child adjustment. Social Development. 2004;13:350–376. [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak JJ, Copeland W, Stanger C, Wadsworth M. Screening for DSM-IV externalizing disorders with the Child Behavior Checklist: a Receiver-Operating characteristic analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:1299–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J, Sarna S, Koskenvuo M, Rantasalo I. The Finnish Twin Registry: formation and compilation, questionnaire study, zygosity determination procedures, and research program. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1978;24:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Baker JH. Genetic influences on measures of the environment: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:615–626. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Burt SA. The Michigan State University Twin Registry: genetic, environmental, and neurobiological influences on behavior across development. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:971–979. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley K, Turic D, Rice F, Holmans P, van den Bree MB, Craddock N, et al. Testing for gene × environment effects in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated antisocial behavior. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part B Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2008;147B:49–53. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehn H, Derks EM, Hudziak JJ, Heutink P, van Beijsterveldt TC, Boomsma DI. Attention problems and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in discordant and concordant monozygotic twins: evidence of environmental mediators. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:83–91. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242244.00174.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy F, Hay D, McStephen M, Wood C, Waldman I. ADHD: a category or a continuum? Genetic analysis of a large-scale twin study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:737–744. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichentenstein P, DeFaire U, Floderus B, Svartengren W, Svedberg P, Pedersen NL. The Swedish Twin Registry: a unique resource for clinical, epidemiological, and genetic studies. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2002;252:181–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF. An empirical comparison of information-theoretic model selection criteria. Behavior Genetics. 2004;34:593–610. doi: 10.1007/s10519-004-5587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Nigg JT. Child ADHD and personality/temperament traits of reactive and effortful control, resiliency, and emotionality. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1175–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Bouchard TJ. Adjustment of twin data for the effects of age and sex. Behavior Genetics. 1984;14:325–343. doi: 10.1007/BF01080045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale M, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statisical modeling. 5th ed. Department of Psychiatry; Richmond: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. What causes ADHD? Understanding what goes wrong and why. The Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Hinshaw SP, Huang-Pollock C. Disorders of attention and impulse regulation. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, volume 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2nd ed. Wiley; Hoboken: 2006. pp. 358–403. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Nikolas MA, Miller T, Burt SA, Klump KL, von Eye A. Factor structure of the child perception of marital conflict scale for studies of youth with externalizing behavior problems. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:450–456. doi: 10.1037/a0016564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Nikolas M, Knotterus GM, Cavanagh K, Friderici K. Confirmation and extension of blood lead with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and ADHD symptom domains at population-typical exposure levels. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolas M, Burt SA. Genetic and environmental influences on ADHD symptom dimensions of inattention and hyperactivity: a meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:1–17. doi: 10.1037/a0018010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters H, Van Gestel S, Vlietinck R, Derom C, Derom R. Validation of a telephone zygosity questionnaire in twins of known zygosity. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:159–161. doi: 10.1023/a:1021416112215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, McClearn GE, McGruffin P. Behavioral Genetics. Rev. 5th Edition Worth Publishers and W.H. Freeman and Company; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. Variance component models for gene-environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Research. 2002;5:554–571. doi: 10.1375/136905202762342026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathouz PJ, Van Hulle CA, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID, Lahey BB. Specification, testing, and interpretation of gene-by-measured-environment interaction models in the presence of gene-environment correlation. Behavior Genetics. 2008;38:301–315. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retz W, Freitag CM, Retz-Junginger P, Wenzler D, Schneider M, Kissling C, et al. A functional serotonin transporter promoter gene polymorphism increases ADHD symptoms in delinquents: interaction with adverse childhood environment. Psychiatry Research. 2008;158:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades KA. Children's responses to interparental conflict: a meta-analysis of their associations with child adjustment. Child Development. 2008;79:1942–1956. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld MJ, van der Valk JC, Bongers IL, Stroet TM, Slagboom PE, Boomsma DI. Zygosity in young twins by parent report. Twin Research. 2000;3:134–141. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial adversity and child psychopathology. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:480–493. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.6.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS. Causal models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: from common simple deficits to multiple developmental pathways. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd RD, Neuman RJ. Gene-environment interactions in the development of combined type ADHD: development of a synapse-based model. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2007;144B:971–975. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA. Test of word reading efficiency. PRO-ED; Austin: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman ID. Gene-environment interactions re-examined: does mother's marital stability interact with the dopamine receptor D2 gene in the etiology of childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:1117–1128. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen CK, Henker B. The child with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in family contexts. In: Quay HC, Hogan AE, editors. Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders. Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York: 1999. pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wymbs BT, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM. Mother and adolescent reports of interparental discord among parents of adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2008;16:29–41. doi: 10.1177/1063426607310849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]