Quinolizidine alkaloids (QAs) are specialized metabolites found mostly in the Leguminosae. This study identifies lysine/ornithine decarboxylases involved in the first step of QA biosynthesis, highlighting the occurrence of lysine decarboxylase in QA-producing plants with regulation and evolution of QA biosynthesis.

Abstract

Lysine decarboxylase (LDC) catalyzes the first-step in the biosynthetic pathway of quinolizidine alkaloids (QAs), which form a distinct, large family of plant alkaloids. A cDNA of lysine/ornithine decarboxylase (L/ODC) was isolated by differential transcript screening in QA-producing and nonproducing cultivars of Lupinus angustifolius. We also obtained L/ODC cDNAs from four other QA-producing plants, Sophora flavescens, Echinosophora koreensis, Thermopsis chinensis, and Baptisia australis. These L/ODCs form a phylogenetically distinct subclade in the family of plant ornithine decarboxylases. Recombinant L/ODCs from QA-producing plants preferentially or equally catalyzed the decarboxylation of l-lysine and l-ornithine. L. angustifolius L/ODC (La-L/ODC) was found to be localized in chloroplasts, as suggested by the transient expression of a fusion protein of La-L/ODC fused to the N terminus of green fluorescent protein in Arabidopsis thaliana. Transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) suspension cells and hairy roots produced enhanced levels of cadaverine-derived alkaloids, and transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing (La-L/ODC) produced enhanced levels of cadaverine, indicating the involvement of this enzyme in lysine decarboxylation to form cadaverine. Site-directed mutagenesis and protein modeling studies revealed a structural basis for preferential LDC activity, suggesting an evolutionary implication of L/ODC in the QA-producing plants.

INTRODUCTION

Alkaloids are one of the most diverse groups of natural products and are found in ~20% of plant species. Many of the ~12,000 known alkaloids produced by plants display potent pharmacological activities and several are widely used as pharmaceuticals (Croteau et al., 2000; De Luca and St Pierre, 2000). Alkaloids are derived from the products of primary metabolism with amino acids such as Phe, Tyr, Trp, Orn, and Lys serving as their main precursors (Facchini, 2001). Quinolizidine alkaloids (QAs) are derived from cadaverine, and several hundred structurally related compounds have been identified that are distributed mostly within the Leguminosae (Ohmiya et al., 1995; Michael, 2008). Some QAs exhibit beneficial pharmacological properties, such as cytotoxic, antiarrhythmic, oxytocic, hypoglycemic, and antipyretic activities, and thus can be used as drugs (Ohmiya et al., 1995). They can therefore serve as potential starting compounds in the development of new drugs and in pest control for plants (Saito and Murakoshi, 1995).

QAs are synthesized through the cyclization of the cadaverine unit (Golebiewski and Spenser, 1988), which is produced through the action of Lys decarboxylase (LDC; EC 4.1.1.18) (Figure 1), via a postulated enzyme-bound intermediate (Saito and Murakoshi, 1995). The various skeletons of QAs [e.g., bicyclic alkaloids such as (−)-lupinine and (+)-epilupinine or tetracyclic alkaloids such as (+)-multiflorine, (+)-lupanine, and (+)-matrine] are then further modified by tailoring reactions (e.g., dehydrogenation, oxygenation, esterification, and glycosylation) to yield hundreds of structurally related alkaloids (Ohmiya et al., 1995).

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic Pathway of QAs.

Biosynthetic pathway of QAs from l-Lys via cadaverine. LDC is responsible for the first step of biosynthesis.

However, the molecular mechanism underlying QA biosynthesis is poorly understood, unlike the mechanisms of biosynthesis of other plant alkaloids, such as tropane, isoquinoline, and indole alkaloids (De Luca and St Pierre, 2000; Facchini, 2001; Sato et al., 2007; Kutchan et al., 2008). Very few studies have aimed to characterize the enzymes and regulatory mechanisms involved in QA biosynthesis. These include some preliminary biochemical characterizations performed using crude cell-free extracts (Strack et al., 1991; Saito et al., 1993; Hirai et al., 2000) or purified preparations from Lupinus plants (Suzuki et al., 1994) and the identification of the gene for an acyltransferase that catalyzes the final step of QA biosynthesis (Okada et al., 2005).

LDC and Orn decarboxylase (ODC; EC 4.1.1.17) are key enzymes involved in the formation of cadaverine and putrescine by the decarboxylation of Lys and Orn, respectively. Putrescine is also synthesized by an additional pathway via Arg decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.19) as elucidated in Arabidopsis thaliana (Hanfrey et al., 2001). ODC is closely related to cell proliferation and is essential for normal cell growth (Pegg, 1988). Cadaverine and putrescine, and other aliphatic polyamines, such as spermidine and spermine, are known to be involved in a number of growth and developmental processes (Bagni and Tassoni, 2001). Cadaverine is implicated as a precursor not only in the biosynthesis of QAs but also of piperine, lobeline, and other types of alkaloids having piperidine or pyridine rings (Leistner and Spenser, 1973). Unlike plant ODCs, plant LDCs have not been well studied at the molecular level despite their important role in the synthesis of a broad range of alkaloids. It has been suggested that ODC may also have LDC activity in plants that make these types of alkaloids (Sinclair et al., 2004). There are a few studies on crude protein extracts or partially purified LDC from soybean (Glycine max) (Kim et al., 1998; Ohe et al., 2009) and garden lupin (Lupinus polyphyllus) (Hartmann et al., 1980), but no molecular information is available so far for plant LDC.

In this study, we cloned and characterized Lys/Orn decarboxylases (L/ODCs) from QA-producing plants and provide evidence from in vitro and in vivo experiments in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and Arabidopsis that these enzymes are involved in the first step of QA biosynthesis. In addition, we identified an important residue for LDC activity (substantiated by protein modeling and mutation studies), implying an adaptive evolutionary link between the production of QAs and the occurrence of LDC in plants. This research is a breakthrough in the understanding of QA biosynthesis, a topic that has not received much attention, despite the importance of QAs as a large class of plant alkaloids.

RESULTS

Cloning of cDNAs Encoding LDC from QA-Producing Plants

To isolate cDNAs involved in QA biosynthesis, we conducted a differential PCR-select subtraction analysis using cDNAs from the seedlings of two different Lupinus angustifolius cultivars: a QA-producing bitter cultivar (cv Fest) and a sweet cultivar that does not produce QA (cv Uniharvest) (Bunsupa et al., 2011). The bitter and sweet cultivars are similar in flowering time and pod shattering but differ in alkaloid contents and the colors of the flower and seed coat (Oram, 1983). We obtained 71 cDNA fragments specifically expressed in the bitter cultivar and 43 fragments from the sweet cultivars. Among those fragments specifically expressed only in the QA-producing bitter cultivar, three exhibited sequence similarity with plant ODC and were identified as putative LDCs. A full-length cDNA clone L. angustifolius L/ODC (La-L/ODC) was obtained by 5′- and 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends. The L/ODC cDNA contained an open reading frame (ORF) of 1320 bp encoding 440 amino acids.

On the basis of the sequence homology between La-L/ODC and other plant ODCs, additional L/ODC cDNAs were isolated from four other QA-producing Leguminosae plants, namely, Sophora flavescens, Echinosophora koreensis, Thermopsis chinensis, and Baptisia australis (hereafter referred to as Sf-L/ODC, Ek-L/ODC, Tc-L/ODC, and Ba-L/ODC, respectively) using degenerate primers (see Supplemental Table 1 online). We obtained full-length clones of Sf-L/ODC and Ek-L/ODC and partial-length clones of Tc-L/ODC and Ba-L/ODC (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). The deduced amino acid sequences of La-L/ODC, Sf-L/ODC, and Ek-L/ODC were highly similar to one another (81% identity between La-L/ODC and Sf-L/ODC, 82% identity between La-L/ODC and Ek-L/ODC, and 98% identity between Sf-L/ODC and Ek-L/ODC). Somewhat lower sequence identities were observed to ODCs from other plants: 71 to 78% for soybean (Delis et al., 2005), 60 to 61% for devil’s trumpet (Datura stramonium) (Michael et al., 1996), and 58 to 63% for tobacco (Nicotiana glutinosa) (Lee and Cho, 2001). Furthermore, Tc-L/ODC and Ba-L/ODC also showed high amino acid sequence identities with La-L/ODC, Sf-L/ODC, and Ek-L/ODC (87 to 99% identities) and lower identities with other plant ODCs, with 63 to 77% identities.

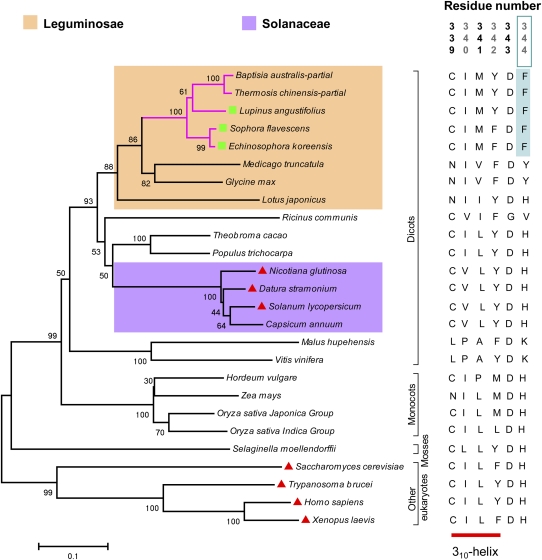

A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method for plant L/ODCs and ODCs from bakers’ yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (Fonzi and Sypherd, 1987), human (Homo sapiens) (Dufe et al., 2007), frog (Xenopus laevis) (Bassez et al., 1990), and a protist (Trypanosoma brucei) (Grishin et al., 1999). All plant L/ODCs were in the same branch, which was further divided into three subgroups: L/ODCs from mosses, monocots, and dicots. La-L/ODC and other L/ODCs from QA-producing plants are closely related to one another and form a distinct clade inside ODCs from other Leguminosae (Figure 2; see Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Data Set 1 online), suggesting a close evolutionary relationship between L/ODCs from QA-producing plants.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic Tree of Eukaryotic L/ODCs.

Unrooted neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of selected eukaryotic L/ODCs. The active-site amino acid residues that differ between LDC and ODC proteins are indicated for each sequence of the tree. Residue number is based on La-L/ODC numbering. Green boxes and red triangles indicate L/ODC and ODC enzymes, respectively, whose biochemical properties have been investigated. Magenta lines indicate quinolizidine alkaloid–producing plants. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are shown above each branch. Accession numbers of enzymes are listed in Supplemental Table 2 online.

L/ODC from QA-Producing Plants Exhibit L/ODC Activity in Vitro

To determine the biochemical function of La-L/ODC, Sf-L/ODC, and Ek-L/ODC, the ORFs of these genes were inserted into a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tag Escherichia coli expression vector as an N-terminal fusion. The observed molecular masses of tag-purified/cleaved recombinant proteins on SDS-PAGE matched well with the predicted 47-, 49-, and 49-kD sizes for La-L/ODC, Sf-L/ODC, and Ek-L/ODC, respectively (see Supplemental Figure 2A online). Decarboxylation activities were assayed with these recombinant proteins using l-Orn and l-Lys as substrates. The optimal pH for both ODC and LDC activities was evaluated, and pH 7.5 was determined to be the optimal value for both reactions.

The three recombinant L/ODCs exhibited decarboxylase activities using both substrates with relatively similar kinetic properties. This is in contrast with the reported decarboxylase activity of N. glutinosa, which exhibits an extremely low activity to l-Lys (Lee and Cho, 2001). The apparent kcat values ranged from 0.73 to 1.16 s−1 for l-Orn and 1.18 to 2.32 s−1 for l-Lys, while the Km values ranged from 1.05 to 1.53 mM for l-Orn and 2.10 to 3.85 mM for l-Lys (Table 1). Comparison of the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of these L/ODCs with respect to the substrates revealed that they preferentially or equally catalyzed the decarboxylation of l-Lys over l-Orn.

Table 1.

Kinetic Parameters of L/ODCs and La-L/ODC Mutant Proteins

| Protein | Km (mM) | Vmax (nmol min−1μg−1 | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | LDC/ODC Ratio of kcat/Km | ||||

| LDC | ODC | LDC | ODC | LDC | ODC | LDC | ODC | ||

| La-L/ODC_wild type | 2.37 | 1.05 | 1.49 | 1.14 | 1.180 | 0.91 | 433 | 859 | 0.500 |

| Sf-L/ODC | 2.10 | 1.53 | 2.94 | 1.46 | 2.320 | 1.16 | 1108 | 755 | 1.470 |

| Ek-L/ODC | 3.85 | 1.32 | 2.42 | 0.76 | 1.910 | 0.73 | 469 | 454 | 1.030 |

| Ng-ODCa | 1.59 | 0.56 | 1.52 × 10−4 | 1.25 × 10−2 | 0.007 | 0.58 | 4.4 | 1035 | 0.004 |

| La-L/ODC-M341L | 2.49 | 1.04 | 4.90 | 0.37 | 3.880 | 0.29 | 1558 | 279 | 5.580 |

| La-L/ODC-F344Y | 5.26 | 1.59 | 7.99 | 0.51 | 6.330 | 0.40 | 1203 | 253 | 4.750 |

| La-L/ODC-F344H | 97.84 | 1.53 | 181.82 | 2.90 | 143.980 | 2.29 | 1471 | 1496 | 0.980 |

All experiments were performed in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. Kinetic parameters were calculated from mean values (n = 3 to 4).

Recalculated from reported values for N. glutinosa L/ODC (Lee and Cho, 2001).

Because the results of our previous experiment showed that La-L/ODC possesses decarboxylase activity toward both l-Lys and l-Orn, we asked if they compete with each other. A competitive assay was performed by varying the concentrations of l-Lys (0.5 to 3.0 mM) in the presence (2mM) and absence of l-Orn. The double-reciprocal plots of 2.0 mM l-Orn intersect at 1/Vmax on the y axis, showing a competitive reaction pattern (see Supplemental Figure 3A online). In addition, we also tested if the decarboxylase activity of La-L/ODC was inhibited by α-difluoromethylornithine (α-DFMO), an ODC suicide inhibitor. The observed LDC activity was distinctly inhibited by α-DFMO in a dose-dependent manner (see Supplemental Figure 3B online). These results demonstrate that the catalytic site of La-L/ODC for the two substrates is identical.

To obtain kinetic information on ODCs from non-QA-producing leguminous plants, recombinant proteins Gm-ODC from soybean and Lj-ODC from Lotus japonicus were assayed for L/ODC activity. The recombinant Gm-ODC and Lj-ODC exhibited ODC and LDC activities with optimal pH at 7.5 to 8.0. However, Lj-ODC exhibited very weak LDC activity. The activities of Gm-ODC and Lj-ODC were very low compared with La-L/ODC, presumably because of the insoluble nature of the recombinant proteins.

Site-Directed Mutation and Protein Modeling Locates a Critical Amino Acid Residue for Substrate Specificity

Sequence alignment of eukaryotic L/ODCs indicated that the amino acid sequences (positions 339 to 344) of presumable substrate binding sites responsible for holding the substrate/product were completely conserved in L/ODCs from QA-producing plants (Figure 2; see Supplemental Figure 1 online). Three-dimensional structures of ODCs and earlier site-directed mutation studies (Grishin et al., 1999; Lee and Cho, 2001; Jackson et al., 2004) suggested the catalytic mechanism and substrate binding sites. Two amino acid residues (Met-341 and Phe-344) that are conserved within L/ODCs from QA-producing plants were characteristically altered from the consensus residues of other eukaryotic ODCs. These two amino acid residues of La-L/ODC were mutated to the other eukaryotic ODC consensus ones, thus generating the mutants La-L/ODC-M341L, La-L/ODC-F344H, and La-L/ODC-F344Y (Figure 2). The purified mutant proteins (see Supplemental Figure 2B online) were tested for decarboxylase activity (Table 1). Of these, the mutation of Phe-344 proved to be the most critical for substrate binding. The mutations of La-L/ODC-F344H resulted in an increase of Km for l-Lys by 41-fold (97.84 mM/2.37 mM) and only by 1.5-fold (1.53 mM/1.05 mM) for l-Orn, whereas the mutation of La-L/ODC-F344Y resulted in an increased of Km for l-Lys by 2.2-fold (5.26 mM/2.37 mM) and by 1.5-fold (1.59 mM/1.05 mM) for l-Orn compared with the wild-type La-L/ODC, indicating the importance of Phe-344 for acceptance of l-Lys as the substrate. The mutations of La-L/ODC-M341L caused only minor changes to the Km for both substrates (Table 1). Interestingly, the mutation of La-L/ODC-F344H not only increased Km value but also the turnover number for l-Lys. The mutation in this position may affect the overall structure of La-L/ODC protein, thus leading to changes in overall enzymatic properties, especially in the catalytic step, of which the precise mechanism(s) still needs to be clarified.

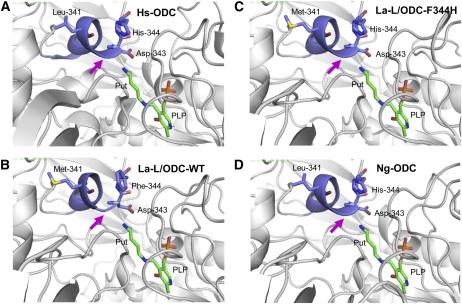

The tertiary structure of La-L/ODC was predicted by SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/) using human ODC (Hs-ODC) (Dufe et al., 2007), with 45% amino acid identity to La-L/ODC as a template for protein modeling. Overall, the predicted protein structure of La-L/ODC was similar to the eukaryotic ODC structures that have been determined previously, including T. brucei (Tb-ODC) (Jackson et al., 2000) and mouse (Mus musculus) (Kern et al., 1999). The predicted La-L/ODC structure was a symmetrical homodimer, formed by a head-to-tail interaction between the barrel of one domain and the sheet domain of the other (see Supplemental Figure 4A online). Conserved amino acid residues of the binding sites of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) and the substrate were superimposed well on to the Hs-ODC crystal structure with the exception of the 310-helix at the active site, which is responsible for holding the PLP-bound putrescine/cadaverine (see Supplemental Figure 4B online). This 310-helix was slightly shorter in the La-L/ODC structure compared with Tb-ODC and Hs-ODC (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the Human ODC (Hs-ODC) Structure with Predicted Protein Structures of La-L/ODC, La-L/ODC Mutant, and Ng-ODC with the Schiff Base Intermediate of Putrescine with PLP at the Active Site.

Hs-ODC (A) was used as a template for protein modeling. Models are for La-L/ODC-WT (wild-type protein) (B), La-L/ODC-F344H (a site-directed mutant protein) (C), and Ng-ODC (D). The magenta arrows indicate the critical structural change regarding the extension of 310-helix, which could be responsible for accepting cadaverine and putrescine. The picture was created by PyMOL. Put, putrescine.

We also generated a structural model of the La-L/ODC mutants and N. glutinosa ODC (Ng-ODC) (Lee and Cho, 2001) by the same method. The predicted La-L/ODC-F344H and Ng-ODC protein structures showed a longer 310-helix like Hs-ODC, while the other two mutants showed a shorter 310-helix as for the wild-type La-L/ODC (Figures 3C and 3D; see Supplemental Figure 4C online). These results suggest a critical role for the length of the 310-helix in accepting l-Lys as the substrate. The length of the 310-helix is determined by the residue at 344, and it presumably changes the cavity size of the substrate binding pocket (see Discussion).

Tissue-Specific and Cultivar-Specific Expression of L. angustifolius L/ODC

The L/ODC transcript level was examined in different tissues (young and mature leaves, cotyledons, hypocotyls, and roots) of bitter and sweet cultivars of L. angustifolius using quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 4A). In the bitter cultivar, the L/ODC transcript level was the highest in the young leaves and was barely detected in other organs. No detectable level of expression was observed in the tissues of the sweet cultivar (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Molecular Analysis of L. angustifolius L/ODC.

(A) Accumulation of La-L/ODC mRNA in various tissues of two cultivars, bitter (cv Fest) and sweet (cv Uniharvest), of L. angustifolius plants by quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

(B) Genomic PCR analysis of La-L/ODC. DNA was extracted from young leaves of both cultivars and subjected to genomic PCR analysis using the same primer pair that was used for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Lane M, λPstI marker.

(C) DNA gel blot analyses of La-L/ODC. Fifteen micrograms of genomic DNA of both cultivars was digested with EcoRI (lane I), EcoRV (lane II), and HindIII (lane III). The La-L/ODC ORF was used as a probe for hybridization. In both cultivars, at least one EcoRI- and HindIII-digested band was hybridized at 4.4 and 4.2 kb, respectively.

A genomic PCR was performed using the genomic DNA extracted from young leaves of both bitter and sweet cultivars of L. angustifolius using the same specific primers used for quantitative RT-PCR. The fragment obtained from genomic PCR was ~1.3 kb in both the bitter and sweet cultivars, indicating that there is no intron inside the L/ODC gene in the L. angustifolius genome (Figure 4B). The sequences of these genomic fragments from both the bitter and sweet cultivars were identical with that of the cDNA from the bitter cultivar. A DNA gel blot analysis to look for nucleotide identities showed that there is at least one copy of L/ODC with identical nucleotide sequence (of at least 1.3-kb span) in both bitter and sweet cultivars of L. angustifolius (Figure 4C).

L/ODC Is Targeted to Plastids

The probable localization of L. angustifolius L/ODC protein was analyzed using the program WoLF PSORT (http://wolfpsort.org/), which predicted that this protein is most likely found in the chloroplast (probability score for chloroplast: 10.0, nucleus; 2.0, cytosol; 2.0). However, analysis of the N-terminal sequence for chloroplast targeting using ChloroP v1.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/), SignalP v3.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/), and TargetP v1.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/) programs showed that no transit peptides were present.

To determine the subcellular localization of L/ODC, we examined the transient expression of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused with the N-terminal 100 amino acids of L. angustifolius L/ODC protein (La-L/ODC100-GFP) in Arabidopsis plants using the particle bombardment method. Two plastid-targeting fusion proteins, a fusion of ribulose-1,5-bis-phosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) transit peptide (Krebbers et al., 1988) with GFP (Rubisco-TP-GFP) and a fusion of transit peptide of rice (Oryza sativa) Waxy (Kitajima et al., 2009) with red fluorescent protein from Discosoma sp (DsRed) (Wx-TP-DsRed), were used as references for plastid localization. A Bsas 3:1 (spinach mitochondrial β-substituted Ala synthase) transit peptide fused to GFP (Bsas 3:1-TP-GFP) (Noji et al., 1998) and the pTH2 vector (Chiu et al., 1996) were used as references for mitochondrion and cytosol localizations, respectively. L/ODC100-GFP and Rubisco-TP-GFP were simultaneously expressed with Wx-TP-DsRed in Arabidopsis leaves. As shown in Figure 5A, L/ODC100-GFP fluorescence overlapped with the plastid fluorescence visualized by Wx-TP-DsRed. This localization pattern was identical with Rubisco-TP-GFP, which overlapped with Wx-TP-DsRed (Figure 5B). Thus, the N-terminal 100 amino acids of L/ODC was capable of translocating the passenger protein to plastids, indicating the plastidic localization of L/ODC, in agreement with the previous study of localization of LDC enzymatic activity in L. polyphyllus (Hartmann et al., 1980).

Figure 5.

Plastid Localization of L. angustifolius L/ODC N-Terminal 100 Amino Acids Fused with GFP in Arabidopsis Leaves.

(A) Arabidopsis leaves expressing L. angustifolius L/ODC100-GFP and Wx-TP-DsRed. L/ODC100-GFP, green (left); Wx-TP-DsRed, red (middle); GFP and DsRed merged image (right).

(B) Control experiments. Rubisco-TP-GFP (left), Wx-TP-DsRed (middle), and GFP and DsRed merged image (right).

Bars = 10 μm.

Overexpression of L. angustifolius L/ODC Enhances Production of Cadaverine-Derived Alkaloids in Tobacco Hairy Roots and BY-2 Cells

To confirm whether L/ODC functions as an LDC in alkaloid production in vivo, we overexpressed L. angustifolius L/ODC in stable transformants under the control of the 35S promoter in tobacco hairy root cultures and BY-2 suspension cells. RT-PCR analysis confirmed the expression of L/ODC in all overexpressing lines. The alkaloid levels in the transgenic tobacco lines expressing La-L/ODC were analyzed by HPLC-photodiode array detection and HPLC–mass spectrometry (MS). In the hairy roots, the contents of anabasine and anatalline (Figure 6) increased by 28.9% (P = 0.023) and 25.1% (P = 0.015), respectively, compared with the corresponding levels in the control lines (β-glucuronidase [GUS]-expressing lines). By contrast, the level of nicotine remained constant or even decreased slightly (Figure 6). In addition, the amounts of l-Lys, l-Orn, cadaverine, and putrescine in the hairy roots of transgenic tobacco expressing La-L/ODC were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis (CE)-MS. The levels of cadaverine and putrescine slightly increased in the transgenic lines by 24.1% (P = 0.126) and 12.1% (P = 0.098), respectively (see Supplemental Figure 5 online).

Figure 6.

Overexpression of L. angustifolius L/ODC in Tobacco Hairy Roots and BY-2 Suspension Cells.

Biosynthetic pathway of tobacco alkaloids with the average contents of tobacco alkaloids in La-L/ODC–overexpressing (LDC) hairy roots and BY-2 cells and compared with the corresponding levels in the control lines expressing a bacterial GUS gene. For hairy roots, each bar represents the mean ± se of average contents of tobacco alkaloids in six independent L/ODC-overexpressing lines (biological replicates; n = 4 for each line) and four independent GUS-expressing lines (biological replicates; n = 4 for each line). For tobacco BY-2 cells, each bar shows the mean ± se of average contents of tobacco alkaloids in eight independent L/ODC-overexpressing BY-2 cells and five independent control lines expressing GUS gene; for BY-2 cells, both cell lines were treated with methyl jasmonate. Student’s one-tailed t test, *P value < 0.05. Broken lines indicate unresolved reactions. DW, dry weight; FW, fresh weight.

The alkaloid levels in the transformed tobacco BY-2 suspension cells expressing La-L/ODC were determined after treatment with methyl jasmonate. Compared with the levels of anabasine and anatalline in the control lines, the levels in the La-L/ODC expressing cells increased by 102.9 and 66.4% (P = 0.0437), while the those of nicotine even decreased by 29.1% (Figure 6).

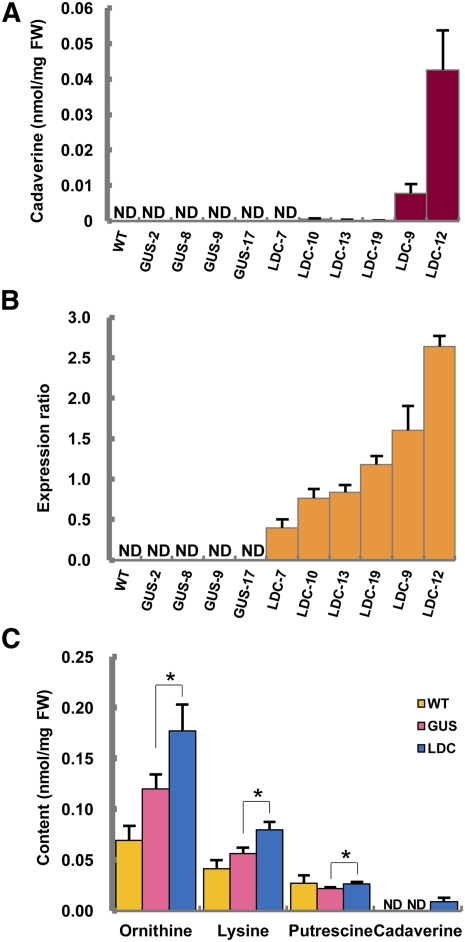

Expression of L. angustifolius L/ODC in Arabidopsis Promotes Production of Cadaverine

In transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing L. angustifolius L/ODC, the contents of l-Lys, l-Orn, cadaverine, and putrescine were analyzed by CE-MS. Ectopic expression in several overexpressing lines of La-L/ODC Arabidopsis showed the accumulation of cadaverine, which was not detected in the control plants (wild-type and GUS-overexpressing lines) (Figure 7A). La-L/ODC expression was positively correlated with the levels cadaverine (P = 0.000015 and r = 0.745) but showed no correlation with putrescine (P = 0.316 and r = 0.103) (Figures 7A and 7B; see Supplemental Figures 6A and 6B online). The levels of l-Lys and l-Orn were negatively correlated with the expression levels of La-L/ODC (P = 0.008, r = −0.485 and P = 0.030, r = −0.388, respectively) (see Supplemental Figures 6C and 6D online). Furthermore, the levels of l-Lys and l-Orn in the La-L/ODC–overexpressing lines were substantially higher than the corresponding levels in the control (Figure 7C). No other remarkable changes were observed in the rest of metabolites detected by CE-MS (see Supplemental Figure 7 online)

Figure 7.

Overexpression of L. angustifolius L/ODC in Arabidopsis Plants.

(A) The contents of cadaverine in wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing GUS or L/ODC (LDC). FW, fresh weight.

(B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of La-L/ODC transcript in wild-type (WT), GUS-expressing (GUS), and La-L/ODC–overexpressing (LDC) Arabidopsis plants.

(C) The average contents of Lys, Orn, cadaverine, and putrescine in wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing GUS or La-L/ODC (LDC). Expression of La-L/ODC was measured by quantitative RT-PCR, and the expression ratio was calculated based on the β-tubulin gene.

For (A) and (B), each bar represents the mean ± se of four to six biological replicates for each independent line. For (C), each bar represents the mean ± se of the wild type (biological replicate; n = 4), six independent La-L/ODC–overexpressing lines (biological replicates; n = 4 to 6 for each line), and four independent GUS-expressing lines (biological replicates; n = 6 for each line). Student’s one-tailed t test, *P value < 0.05. ND, not detected.

The Patterns of Cadaverine-Related Metabolites Differ in the Bitter and the Sweet Cultivars of L. angustifolius

A study by Hirai et al. (2000) showed no QAs in young leaves (3 weeks old, at the same stage used in this study) of the sweet cultivar of L. angustifolius. In this study, we set out to investigate the contents of l-Lys and l-Orn, the potential biosynthetic precursors of QAs, and putative cadaverine conjugates (their storage form) in the sweet and bitter cultivars. To reveal the relationship between l-Lys and cadaverine and the production of QAs, the contents of l-Lys, l-Orn, putrescine, and cadaverine were determined by CE-MS in both the bitter and sweet cultivars of L. angustifolius. The amounts of l-Lys and l-Orn in the bitter cultivar were ~1.6 and 1.8 times higher than those of sweet cultivar (Table 2). By contrast, the sweet cultivar contained ~1.7 times more putrescine than the bitter one. It is noteworthy that cadaverine was not found in either the bitter or the sweet cultivars; however, the content of putative cadaverine conjugates in the bitter cultivar was 3.2 times higher than in the sweet cultivar, while the amount of putative putrescine conjugates was similar in both cultivars. It is evident that the bitter cultivar more actively accumulated the potential biosynthetic precursor (l-Lys) and its storage form (the cadaverine conjugates) than the sweet cultivar along with the production capability of QAs.

Table 2.

Levels of Polyamines and QAs in Leaves of the Bitter and Sweet Cultivars of L. angustifolius

| Compound | Content (μM FW−1) | |

| Bitter Cultivar | Sweet Cultivar | |

| l-Orn | 4.91 ± 0.12 | 2.79 ± 0.15 |

| l-Lys | 220.53 ± 10.02 | 141.18 ± 12.44 |

| Putrescine | 5.28 ± 0.46 | 9.04 ± 0.74 |

| Cadaverine | ND | ND |

| Putrescine conjugatesa | 9.84 ± 7.51 | 10.62 ± 6.24 |

| Cadaverine conjugatesb | 13.34 ± 1.81 | 4.17 ± 1.03 |

| QAsc | 1218 (μg g−1 FW−1) | <1.0 (μg g−1 FW−1) |

Data represent means ± sd the polyamines in the mixture of leaves from 10 L. angustifolius plants (3 weeks old) in each cultivar (analytical replicate; n = 5). FW, fresh weight; ND, not detected.

Putative putrescine conjugates are predicted based on mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) from CE-MS, including cinnamoyl-, caffeoyl-, dicumaroyl-, dicaffeoyl-, and diferuloyl-putrescine with the corresponding m/z 219.15, 251.15, 381.18, 413.18, and 441.19, respectively. The total amount is calculated on the mass response factor of putrescine as the standard.

Putative cadaverine conjugates are predicted based on m/z from CE-MS, including cinnamoyl-, coumaroyl-, sinapoyl-, dicumaroyl-, dicaffeoyl-, and diferuloyl-cadaverine with the corresponding m/z 233.16, 249.15, 309.18, 395.19, 427.19, and 455.24, respectively. The total amount is calculated on the mass response factor of cadaverine as the standard.

Reported values of QAs in leaves of the bitter and sweet cultivars of L. angustifolius (3 weeks old) from a previous study (Hirai et al., 2000).

DISCUSSION

Physiological Roles of LDC in QA-producing Plants

In this study, we identified three L/ODCs from QA-producing plants and found that these L/ODCs show similar LDC and ODC activities, unlike the known ODCs that accept only Orn (Boeker and Fischer, 1983). Although these L/ODCs from QA-producing plants could catalyze the decarboxylation of both l-Lys and l-Orn with a nearly equal efficiency in vitro, the availability of substrates and their compartmentalization might explain the in vivo function of this enzyme as an LDC. The amount of l-Lys is 45 times higher than l-Orn in L. angustifolius (Table 2). Since protein–amino acid biosynthesis is strictly regulated in the plant cell (Saito et al., 1993; Stepansky et al., 2006), the controlled high content of l-Lys in the bitter cultivar of L. angustifolius may facilitate an efficient formation of cadaverine leading to alkaloid biosynthesis in vivo.

Our results indicate that L. angustifolius L/ODC is localized in the chloroplast, where diaminopimelate decarboxylase, the enzyme involved in the last step of Lys biosynthesis, is thought to be localized (Mazelis et al., 1976). This result is in concurrence with previous studies in Lupinus plants showing that the activity of LDC is associated with chloroplasts (Wink and Hartmann, 1982) and that the majority of QAs are synthesized in shoot tissues (Lee et al., 2007a). This localization of La-L/ODC is in agreement with the localization of ODC in chloroplasts (at least partial) (Andreadakis and Kotzabasis, 1996; Tassoni et al., 2003), supporting a hypothesis that L/ODC evolved from an ancestor ODC (as discussed below). Additionally, it was reported that the metabolic action of bacterial LDC in transgenic plants was improved by its fusion to a chloroplast-targeting signal sequence (Herminghaus et al., 1996).

The ODC transcript levels in plants such as tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (Kwak and Lee, 2001), soybean (Delis et al., 2005), and devil’s trumpet (Michael et al., 1996) showed high transcript levels in developing tissues and expanding cells, such as those in hypocotyls and roots. The transcripts of L. angustifolius L/ODC accumulated coincidently with the production of QAs, exclusively in the young leaves of the bitter cultivar (Figure 4A); this suggests that L/ODC is specifically involved in the biosynthesis of QAs. Genomic PCR and DNA gel blot analyses indicated the presence of a single L/ODC in the genomes of both the bitter and sweet cultivars of L. angustifolius (Figures 4B and 4C); however, the transcript was expressed only in the bitter cultivar. Therefore, the expression of L/ODC, and thus the subsequent biosynthesis of QAs themselves, may be regulated at a steady state mRNA level by transcription factor(s). By PCR-select subtraction, the fragments of the candidate transcription factors that might regulate the expression of the genes in the QA biosynthesis were obtained; these include DNA binding protein EREBP-3, Leu zipper protein, and coronatine-insensitive 1 (Bunsupa et al., 2011). Since the enzyme activity and the transcript level of an acyltransferase committed in the terminal step of QA biosynthesis do not differ in bitter and sweet cultivars (Hirai et al., 2000; Okada et al., 2005), this finding is interesting in terms of the regulation of the whole biosynthetic pathway.

The in vivo experiment with Arabidopsis plants expressing L. angustifolius L/ODC showed the accumulation of cadaverine, which was not detected in the control plants, thus confirming the involvement of this enzyme in Lys decarboxylation to form cadaverine. In the literature (Shoji and Hashimoto, 2008; and references cited therein), anabasine has been confirmed to be derived from cadaverine. The in vivo experiments with transgenic tobacco (hairy roots and BY-2 suspension cells) showed the enhanced production of anabasine in the LDC-overexpressing tobacco cells, clearly indicating that L/ODC acts as an LDC to produce cadaverine from l-Lys in vivo, thus leading to the formation of cadaverine-derived alkaloids.

Taken together, these results support the conclusion that the identified L/ODC catalyzes the decarboxylation of l-Lys to form cadaverine leading to the synthesis of QAs in Lupinus plants.

Substrate Preference and Active Site Structure

The competition and inhibition studies suggest that the catalytic site of L/ODC for the recognition of both substrates is identical (see Supplemental Figure 3 online). The evidence for both LDC and ODC activities being ascribed to the same active site have also been reported in a L/ODC from the bacterium Selenomonas ruminantium, which is capable of decarboxylating both l-Lys and l-Orn with similar kinetic properties, and in the ODC from N. glutinosa (Takatsuka et al., 1999; Lee and Cho, 2001). Unlike other eukaryotic ODCs that are almost exclusively specific for l-Orn over l-Lys (Lee et al., 2007b), the three L/ODCs from QA-producing plants proteins exhibited decarboxylase activities toward both l-Lys and l-Orn, with similar kinetic properties. These results imply that the active site of L/ODC is relatively tolerant to variable side chains of substrate (C5 for Lys and C4 for Orn) for the intermediary Schiff-base formation.

Evaluation of the L/ODC-F344H mutant enzyme activity points out that Phe-344 residue is essential for the expansion of substrate acceptability to l-Orn and l-Lys. Phe-344 is positioned next to the essential Asp-343 residue, which interacts with N(ε) of PLP-bound putrescine as indicated in the human ODC (Grishin et al., 1999). In the authentic ODCs accepting only Orn, this Phe-344 is replaced with His (Figure 2). Because the decarboxylation reaction needs a fixed quinoid intermediate, the size and polarity of the cavity of the reaction intermediate is very important in forming the correct C(α)-N configuration (Grishin et al., 1999). The amino acid residue (Phe or His-344) adjacent to the Asp-343 responsible for the correct positioning of the quinoid intermediate must have a critical role for the substrate acceptability (i.e., Lys and Orn). In fact, our results show that the mutation of L/ODC-F344H resulted in a remarkable increase of Km for l-Lys but only in a minimal change for l-Orn, indicating the importance of Phe-344 for the acceptance of l-Lys as a substrate. However, the L/ODC-F344Y mutant has a lesser effect on the Km values for these two substrates. Interestingly, Gm-ODC has Tyr instead of His at position 344 (La-L/ODC numbering). This suggests that Gm-ODC might catalyze both l-Lys and l-Orn with similar extent. Indeed, this speculation is supported by the study of recombinant Gm-ODC protein, which exhibits both LDC and ODC activities. By contrast, another leguminous plant enzyme Lj-ODC having His-344 exhibited only ODC activity, indicating the diversification of L/ODC in Leguminosae plants.

The molecular modeling data further explain why L/ODCs from QA-producing plants are able to efficiently catalyze the reaction for l-Lys. Predicted protein structures of the L/ODCs showed that the length of the 310-helix of La-L/ODC-WT is shorter than those of La-L/ODC-F344H, Ng-ODC, and Hs-ODC (Figure 3; see Supplemental Figure 4C online). The 310-helix is critical in determining the size of the cavity of catalytic site because Asp-343 adjacent to the 310-helix forms a hydrogen bond with the putrescine bound to PLP. Phe-344 does not form an extra helix next to the 310-helix as His-344 does, thereby accommodating the one-carbon larger side chain of l-Lys. The La-L/ODC-F344H mutant, as with Hs-ODC and Ng-ODC, has a longer 310-helix and was incapable of accepting l-Lys, but had a minimal effect on ODC activity. A similar mechanism of acceptance of substrates by varied cavity size of substrate pocket was reported by x-ray crystal structure studies in Vibrio vulnificus L/ODC (Vv-L/ODC), which decarboxylases both l-Lys and l-Orn with similar Km and Vmax values (Lee et al., 2007b). The ability of Vv-L/ODC to interact with l-Orn appears to be due to the positioning of a bridging water molecule that participates in the binding of the shorter putrescine ligand, but this water molecule is absent in the cadaverine-bond structure. A similar situation may be conceivable for La-L/ODC to accept both Lys and Orn substrates. Further studies on x-ray structural analysis of La-L/ODC should provide more precise insight into the structural basis for this dual function.

The results of the mutation study indicate that Phe-344 is a key residue for L. angustifolius L/ODC to exhibit substrate promiscuity for Lys and Orn. These results reveal how plants have been opportunistic in adapting primary metabolic processes to permit the diversification of secondary metabolism, in this case, substrate promiscuity. Accordingly, the mutation in this position might possibly be found not only in QA-producing Leguminosae plants but also in other plant species that produce a variety of cadaverine-derived alkaloids, such as pomegranate (Punica granatum), lobelia (Lobelia inflata), and black pepper (Piper nigrum), which produce pelletierine, lobeline, and piperine, respectively. This is an interesting question on possible convergent evolution of plant species modifying their synthesis of specialized metabolites for adaptation to their environment (as discussed in Pichersky and Lewinsohn, 2011) and needs to be addressed in future studies.

Evolution of LDC in QA-Producing Plants

Identification of the La-L/ODC answers a longstanding question about the molecular entity of LDC activity in plants. There was only a speculation that a member of group IV of PLP-dependent amino acid decarboxylases might be responsible for the production of cadaverine from Lys (Sandmeier et al., 1994). Our study provides the evidence for the molecular entity of plant LDC from several QA-producing plants.

QAs are typically found in some phylogenetically related tribes of the Leguminosae (Wink, 1992), but they have also been found in unrelated genera of Chenopodiaceae, Berberidaceae, Ranunculaceae, Scrophulariaceae, and Solanaceae (Kinghorn and Balandrin, 1984). The occurrence of LDC in the plant species of this study coincides with the production of QAs. Many studies have reported that duplication of essential genes of primary metabolism is an important basis for gene recruitment in secondary metabolism (Nakajima et al., 1993; Hashimoto et al., 1998; Ober and Kaltenegger, 2009; Teuber et al., 2007; de Kraker and Gershenzon, 2011). A good example would be the identification of the enzyme homospermidine synthase, which is involved in pyrrolizidine alkaloid biosynthesis, as a modified version of deoxypusine synthase, an enzyme that is involved in the primary metabolism of translational regulation (Ober and Hartmann, 1999). The results of this study (i.e., no indication of the presence of an additional paralogous gene of L/ODC in the genome of L. angustifolius) indicate that the novel L/ODCs have presumably been derived from common plant ODCs with a slight modification as an adaptation aimed at broadening substrate specificity under a certain environmental stress as discussed in other organisms (Ganfornina and Sánchez, 1999; Harlin-Cognato et al., 2006). The second possible scenario is that gene duplication took place from an ancestor ODC, one of the duplicated genes having original ODC activity was deleted, and the other gene evolved to L/ODC by expanding substrate acceptability, as often reported in the evolution of plant genes (Simillion et al., 2002; Blanc and Wolfe, 2004). ODC is not an enzyme absolutely necessary in plants as Arabidopsis does not have ODC (Hanfrey et al., 2001). Further research is required to address the evolutionary consequence of how specialized secondary metabolism has evolved to expand plants’ chemical diversity.

In this context, it is worthwhile noting that the changes in the possible first amino acid (from His-344 in common ODC to Tyr-344 in soybean ODC) and the second amino acid (from Tyr-344 to Phe-344 in QA-producing LDC) were a result of a single nucleotide replacement (a C-to-T transition in the former and an A-to-T transversion in the latter). Such a critical mutation might take place just at two subsequent minimal nucleotide replacements during the evolution. It is less likely but possible that the changes from His to Tyr and His to Phe independently evolved during evolution. The change from His to Phe needs two nucleotide replacements at the same time, but only one nucleotide replacement is needed for the change from Tyr to Phe. A similar change in substrate specificity attributable to a single amino acid difference was reported in the O-methyltransferases involved in isoquinoline alkaloid and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (Frick and Kutchan, 1999; Gang et al., 2002).

In this study, we demonstrated that the isolated LDC genes are involved in the decarboxylation of l-Lys, which is the first step of QA biosynthesis in QA-producing plants. In addition, we also demonstrated a point mutation responsible for substrate promiscuity that is supposed to have occurred via adaptive evolution of LDC within the QA-producing plants. These findings can serve as the basis for future research on not only QA biosynthesis but also on the control of plant alkaloid production. Since cadaverine-derived alkaloids have potential applications in the development of new drugs and in pest control in plants, a further trial for metabolic engineering by combinatorial biochemistry (Oksman-Caldentey and Inzé, 2004) should use the LDC genes.

METHODS

Plant Materials

Seeds of Lupinus angustifolius cv Fest (QA-producing bitter cultivar) and cv Uniharvest (sweet cultivar that does not produce QAs) were from Colin G. Smith (The Australian Lupin Collection Crop Improvement Institute, Australia). Seeds of soybean (Glycine max; B01151) and Lotus japonicus (Gifu) were from National BioResource Project (Japan) and Hiroshi Sudo (Hoshi University, Japan), respectively. Sophora flavescens, Echinosophora koreensis, Thermopsis chinensis, and Baptisia australis were obtained from the Medicinal Plant Gardens of the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Chiba University, Japan.

Cloning of L/ODC cDNA from QA-Producing Plants

The bitter cultivar–specific cDNA fragments were profiled by PCR-select cDNA subtraction (Clontech; PCR-Select cDNA Subtraction Kit) between bitter and sweet cultivars in L. angustifolius. Among 71 bitter-specific cDNA fragments, three fragments showed homology to ODC in deduced amino acid sequences. The cDNA encoding La-L/ODC was isolated by primers that were designed from the nucleotide sequence of these three fragments (see Supplemental Table 1 online for the primers used in this study). Sf-L/ODC, Ek-L/ODC, Tc-L/ODC, and Ba-L/ODC cDNAs were isolated by PCR using degenerate primers designed based on the La-L/ODC and other plants ODC sequences. Each cDNA fragment was obtained with the first-strand cDNA prepared from young leaves as the template and the full-length cDNAs were obtained using 5′- and 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (TaKaRa).

Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogeny and amino acid alignments and phylogenetic data were performed using MEGA version 4 (Tamura et al., 2007). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method. Boot strap values were statistically calculated with the default sets of the MEGA program at 1000 replicates and seed = 44,251. The accession numbers of the L/ODC amino acid sequences used for comparison are listed in Supplemental Table 2 online.

Gene Expression Analysis

Expression Analysis of L/ODC in L. angustifolius

Total RNA was prepared from mature leaves, young leaves, cotyledons, hypocotyls, and roots in both bitter and sweet forms of L. angustifolius using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen). To avoid the contamination of DNA, DNase treatment of total RNA solution was performed. Each total RNA sample (1 μg) was subjected to reverse transcription as described before. PCR was performed using primers LaDC-full-F and LaDC-full-R for L/ODC and primers Tub-F and Tub-R for β-tubulin. The exponential ranges of the PCRs were determined by removing 5 μL of PCR product every three cycles in the range of 24 to 30 cycles to allow quantitative comparisons. We selected 26 cycles for L/ODC and 24 cycles for β-tubulin, so that the amplified products are clearly visible on an agarose gel, but also so that amplification is in the exponential range and has not reached a plateau yet. PCR conditions for L/ODC consisted of 26 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1.5 min and for β-tubulin consisted of 24 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1.5 min. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis using 1.5% gel at 100 V, and gel was further stained by SYBR Green I nucleic acid gel stain (Invitrogen).

Gene Expression Analysis of La-L/ODC–Overexpressing Lines

Total RNA were extracted (RNeasy kit; Qiagen) and reverse transcribed to cDNA as described previously from shoots of each transgenic line. PCR was performed using LaDC-exF and LaDC-exR primers. PCR conditions consisted of 28 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. β-Tubulin was used as a control with the primer pairs as described previously with PCR conditions of 24 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis using 1.5% gel at 100 V, and gel was further stained by SYBR Green I nucleic acid gel stain (Invitrogen). The stained gel was scanned by Storm 860 image analyzer (GE Healthcare). The scanned images were visualized and analyzed using Image Quant (GE Healthcare). The La-L/ODC expression ratio was calculated by comparing with β-tubulin expression.

Genomic PCR

Genomic PCR of La-L/ODC was performed using Ex Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa) with specific primers LaDC-full-F and LaDC-full-R (see Supplemental Table 1 online). PCR was performed with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, then 25 cycles each at 95°C for 30 s, at 55°C for 30 s, and at 72°C for 1.5 min.

DNA Gel Blot Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted by the standard cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide method (Sambrook and David, 2001). Aliquots of 15 μg of genomic DNA were digested with EcoRI, EcoRV, and HindIII and separated under denaturing conditions on a 0.8% agarose gel. After transfer to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham), hybridization was performed with the 32P-labeled probe prepared from the ORF of La-L/ODC cDNA using the Random Primer DNA labeling kit, version 2.0 (TaKaRa). Hybridization signals were detected with a Storm 860 image analyzer (Amersham).

Heterologous Expression of Recombinant L/ODCs

The ORFs of La-L/ODC, Sf-L/ODC, and Ek-L/ODC were amplified by PCR using KOD polymerase (Toyobo) with gene-specific primers overhung with a restriction site (see Supplemental Table 1 online). The La-L/ODC mutants were prepared by PCR-based mutagenesis (Higuchi et al., 1988). PCR was conducted with KOD polymerase (Toyobo) using primers listed in Supplemental Table 1 online. The amplified fragments were inserted in frame into the same restriction site of the expression vector pGEX-6P-2 (Amersham) for Sf-L/ODC, Ek-L/ODC, and La-L/ODC mutants, and pGEX-6P-3 (Amersham) for La-L/ODC, which gives a recombinant gene product with an N-terminal GST protein tag. Complete constructs were sequenced to confirm correct orientation.

The constructs were then introduced into Escherichia coli BL21 competent cells. The E. coli cells harboring designated gene constructs were precultured in Luria-Bertani broth containing 100 μL/mL ampicillin at 37°C overnight. This culture was diluted 1/100 into new Luria-Bertani medium (containing 100 μL/mL ampicillin) and cultured at 37°C until the OD600 reached to 0.4 to 0.6. Then, isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration 0.1 mM and cells were cultured at 20°C for 6 h. The cells were collected and suspended in 1× PBS (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.3). Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and pepstatin A were added to the cell suspension, which was then disrupted by sonication. The disrupted proteins were centrifuged and the supernatants were used as a crude protein extract. Further purification by affinity chromatography was performed with a GSTrap column (Amersham) using AKTA prime purification system (Amersham) according to the manufacturing’s protocol. GST tags were removed from GST fusion recombinant proteins by in-column digestion using protease enzyme (PreScission protease; Amersham). The eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 10% polyacrylamide gels. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay, and BSA was used as a standard.

The full-length soybean and L. japonicus ODC sequences, namely, Gm-ODC and Lj-ODC, respectively, were cloned using the primers designed from Gm-ODC (AJ563382) and Lj-ODC (AJ575746) sequences from GenBank. The ORFs of these genes were cloned and expressed in E. coli and purified as same as the method described for La-L/ODC expression and purification.

LDC and ODC Activity Assays

The activity of LDC and ODC was determined by the measurement of CO2 release from 14C-l-Lys and 14C-l-Orn, respectively (Gaines et al., 1988). Decarboxylase activities were assayed in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 4 mM DTT, 0.3 mM PLP, 0.5 to 3.0 mM l-[1-14C] Lys (40 μCi) or l-[1-14C] Orn (40 μCi) and 0.5 to 1.0 μg purified enzyme to a final volume of 500 μL. Each reaction was performed at 37°C for 30 min. Activities of ODC and LDC were determined by measurement of 14CO2 release from l-[1-14C] Orn and l-[1-14C] Lys, respectively. The kinetics of decarboxylation of both l-Lys and l-Orn were analyzed by measuring initial velocities over the range of substrate concentrations (0.5 to 2.0 mM). Inhibitor assays were conducted using 2 mM l-Orn, 10 μM α-DFMO, and 20 μM α-DFMO.

Molecular Modeling

Three-dimensional model structures of La-L/ODC and its mutants were predicted by SWISS-MODEL (Arnold et al., 2006) using the published Hs-ODC-putrescine complex (Protein Data Bank entry 2OO0) as the template (Dufe et al., 2007). The modeled proteins were visualized by PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

Protein Localization Analysis

The chimeric gene construct of 35Spro:La-L/ODC:GFP was created as follows. The 300 bp from start codon of La-L/ODC was amplified by PCR (for primer sequences, see Supplemental Table 1 online) and was cloned to pTH2 vector (Chiu et al., 1996). Plasmids Rubisco-TP-GFP and Wx-TP-DsRed, carrying transit peptide sequence obtained from the Rubisco small subunit polypeptide of Arabidopsis thaliana (Krebbers et al., 1988) fused to GFP (Noji et al., 1998) and the rice (Oryza sativa) Waxy gene fused to Discosoma sp (DsRed) (Kitajima et al., 2009), were used as a positive control for localization to plastids. The plasmid Bsas3:1-TP-GFP, containing the transit peptide sequence of spinach mitochondrial β-substituted Ala synthase (Bsas3:1) (Noji et al., 1998), fused to GFP, was used as a positive control for localization in mitochondria. Plasmid pTH2 without any fusion protein was used as a positive control for localization in cytosol and partly in nuclei as intrinsic nature of GFP. Resulting plasmids were coated onto 1-μm gold particles (Bio-Rad) and then used to bombard the rosette leaves of 4-week-old Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia plants using a Helios gene gun (Bio-Rad). After bombardment, Arabidopsis plants were cultivated for 20 h under illumination at 22°C. The cobombarded Arabidopsis leaves expressing GFP and/or red fluorescent protein fusion proteins were mounted in distill water on slide glass. Leaves on the slide glass were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscopy system (LSM510 META, Axioplan2 Imaging; Carl Zeiss) with a Plan-Apochromat lens (×40 1.2 water differential interference contrast; optical slices of 2 μm). We used a 25-mW argon laser (power, 5%) with 488-nm excitation and a 505- to 530-nm band-pass filter for GFP. A 560- to 600-nm band-pass filter and 1 mW He-Ne laser at 80% power with 543-nm excitation was used for red fluorescent protein. Crosstalk was prevented using a multitrack configuration with line sequential scanning. Composite figures were prepared using Zeiss LSM Image Browser software.

Plasmid Construction and Plant Transformation

The full-length ORF of La-L/ODC was transferred to the binary expression vector pGWB2 (Nakagawa et al., 2007) via Gateway technology (Invitrogen) to provide pGWB2-La-L/ODC (35Spro:La-L/ODC). Subsequently, an electroporation method was used to introduce pGWB2-La-L/ODC into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 for the generation of transgenic tobacco BY-2 suspension cells (Nicotiana tabacum cv Bright Yellow-2) and Arabidopsis plants, and into Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain 15834 for generation of tobacco hairy root.

Tobacco BY-2 cells suspensions were maintained as described (Nakagawa et al., 2007). Transgenic tobacco BY-2 cells harboring pGWB2-La-L/ODC were generated by A. tumefaciens–mediated transformation according to the protocol (Häkkinen et al., 2007). Transformed colonies were picked and transferred to fresh plates, and their transgenic nature was confirmed by PCR. The transformed calli were subsequently suspended in liquid medium containing 50 ppm of kanamycin and hygromycin to keep selection pressure. Multiple independent transgenic lines were selected for metabolites measurement. These cells were elicited by methyl jasmonate for alkaloid production as described (Häkkinen et al., 2007).

The transgenic tobacco (N. tabacum cv Petit Havana line SR1) hairy roots were generated as described (Shoji and Hashimoto, 2008). The transformed tobacco hairy roots were subcultured in Gamborg B5 medium with 2% Suc every 2 weeks. For metabolite analysis, hairy root were inoculated in 20 mL medium and cultivate in rotary shaker (55 rpm, 25°C) in liquid Gamborg B5 medium with 2% Suc for 2 weeks.

Transgenic Arabidopsis harboring pGWB2-La-L/ODC were generated via A. tumefaciens–mediated transformation by floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). The seeds were collected from the dipped plants and selected in Murashige and Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing 50 ppm of kanamycin and hygromycin. T2 seeds were growth on Murashige and Skoog medium containing 1% (w/v) Suc, 50 ppm of kanamycin, and hygromycin. Plates were incubated at 22°C in a growth chamber with 16/8-h light/dark cycle. After 14 d, all shoots from each transgenic line and wild-type line were pooled separately, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –70°C to perform analysis of gene expression and metabolites.

Measurement of Alkaloids and Amines

Alkaloids of the transformed tobacco BY-2 cells were extracted as described (Häkkinen et al., 2007). For transgenic tobacco hairy roots, fresh samples were homogenized and 25 mg of ground sample was dissolved in extraction solution (methanol containing 250 ng/μL of 2,4’-dipyridyl as internal standard). After sonication in an ultrasonic bath for 2 h, the sample was centrifuged (8000 rpm, 5 min). Supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22-μm polyvinylidene difluoride filter. The samples were stored at –20°C until analysis. Quantitative analysis was performed based on the internal standard method by the HPLC/diode array detection (DAD) system (binary pump, L-7100; DAD, L-7455; autosampler, L-7200; Hitachi) using the same column and chromatographic conditions as described (Häkkinen et al., 2007). Alkaloids were also identified by liquid chromatography–photodiode array detection–electrospray ionization/MS consisting of an Agilent 6120 single quadrupole liquid chromatography/MS and an Agilent HPLC 1100 series (Agilent technologies) using the same column and chromatographic condition as HPLC/DAD. Nitrogen gas was used as a sheath gas for positive ion electrospray ionization/MS performed at a capillary temperature and voltage of 250°C and 4 kV, respectively. The tube lens offset was set at 2.0 V. Full-scan mass spectra were acquired from 100 to 700 mass-to-charge ratio at one scan s−1. Identification of alkaloids was made by comparison with the authentic compounds, such as nicotine (Nacalai Tesque), (±) anabasine (Alfa Aesar), and (±) anatalline (Toronto Research Chemicals). Amines and amino acids of the transformed tobacco hairy root and Arabidopsis plants were extracted and analyzed by CE-MS as described (Ohkama-Ohtsu et al., 2008).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) data library under the following accession numbers: La-L/ODC, L. angustifolius (DDBJ, AB560664); Sf-L/ODC, S. flavescens (DDBJ, AB561138); Ek-L/ODC, E. koreensis (DDBJ, AB561139); Tc-L/ODC, T. chinenesis (DDBJ, AB647178); and Ba-L/ODC, B. australis (DDBJ, AB647177).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Alignment of La-L/ODC, Sf-L/ODC, and Ek-L/ODC Amino Acid Sequences with Other Eukaryotic ODCs.

Supplemental Figure 2. SDS-PAGE of the Recombinant La-L/ODC, Sf-L/ODC, Ek-L/ODC, and La-L/ODC Mutant Proteins in E. coli.

Supplemental Figure 3. Inhibition Study of La-L/ODC by l-Orn and α-DFMO.

Supplemental Figure 4. Comparative Protein Modeling of La-L/ODC and La-L/ODC Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 5. The Contents of Orn, Lys, Putrescine, and Cadaverine in Transgenic Tobacco Hairy Root Expressing GUS or La-L/ODC.

Supplemental Figure 6. Relative Expression between La-L/ODC Expression and Polyamines in Wild-Type, GUS-, and La-L/ODC–overexpressing Lines in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Supplemental Figure 7. Metabolite Profiles of La-L/ODC–Overexpressing Arabidopsis by CE-MS.

Supplemental Table 1. List of Primers Used in This Study.

Supplemental Table 2. Accession Numbers of Genes Used for Phylogenetic Analysis.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Text File of Alignment Used to Generate Phylogenetic Tree in Figure 2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shoko Shinoda (RIKEN Plant Science Center, Japan) for her excellent technical support for CE-MS analysis; Colin G. Smith (The Australian Lupin Collection Crop Improvement Institute, Australia) for kind supply of the seeds of L. angustifolius; Toshiyuki Nagata and Seiichiro Hasezawa (University of Tokyo) for their kind supply and advice on BY-2 cells; Tsuyoshi Nakagawa (Shimane University, Japan) for providing the destination vector pGWB2; Toshiaki Mitsui (Niigata University, Japan) for providing pWx-TP-DsRed vector; Kousuke Hanada (RIKEN Plant Science Center) for comments on evolution; and Anthony J. Michael (University of Texas) for critical comments on the manuscript. This study was supported in part by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and by Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology of the Japan Science and Technology.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.S. and M.Y. designed the research. S.B., K.K., E.I., K.T., and A.O. performed the experiments. S.B., A.O., and M.Y. analyzed the data. S.B. and K.S. wrote the article.

References

- Andreadakis A., Kotzabasis K. (1996). Changes in the biosynthesis and catabolism of polyamines in isolated plastids during chloroplast photodevelopment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 33: 163–170 [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. (2006). The SWISS-MODEL workspace: A web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22: 195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni N., Tassoni A. (2001). Biosynthesis, oxidation and conjugation of aliphatic polyamines in higher plants. Amino Acids 20: 301–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassez T., Paris J., Omilli F., Dorel C., Osborne H.B. (1990). Post-transcriptional regulation of ornithine decarboxylase in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Development 110: 955–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G., Wolfe K.H. (2004). Widespread paleopolyploidy in model plant species inferred from age distributions of duplicate genes. Plant Cell 16: 1667–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeker E.A., Fischer E.H. (1983). Lysine decarboxylase (Escherichia coli B). Methods Enzymol. 94: 180–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunsupa S., Okada T., Saito K., Yamazaki M. (2011). An acyltransferase-like gene obtained by differential gene expression profiles of quinolizidine alkaloid-producing and nonproducing cultivars of Lupinus angustifolius. Plant Biotechnol. 28: 89–94 [Google Scholar]

- Chiu W., Niwa Y., Zeng W., Hirano T., Kobayashi H., Sheen J. (1996). Engineered GFP as a vital reporter in plants. Curr. Biol. 6: 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau R., Kutchan T., Lewis N. (2000). Natural products (secondary metabolites). In Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants, B. Buchanan, W. Gruissem, and R. Jones, eds (Rockville, MD: American Society of Plant Physiologists), pp 1250–1318 [Google Scholar]

- de Kraker J.W., Gershenzon J. (2011). From amino acid to glucosinolate biosynthesis: Protein sequence changes in the evolution of methylthioalkylmalate synthase in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 38–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis C., Dimou M., Efrose R.C., Flemetakis E., Aivalakis G., Katinakis P. (2005). Ornithine decarboxylase and arginine decarboxylase gene transcripts are co-localized in developing tissues of Glycine max etiolated seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43: 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca V., St Pierre B. (2000). The cell and developmental biology of alkaloid biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 5: 168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufe V.T., Ingner D., Heby O., Khomutov A.R., Persson L., Al-Karadaghi S. (2007). A structural insight into the inhibition of human and Leishmania donovani ornithine decarboxylases by 1-amino-oxy-3-aminopropane. Biochem. J. 405: 261–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchini P.J. (2001). Alkaloid biosynthesis in plants: Biochemistry, cell biology, molecular regulation, and metabolic engineering application. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52: 29–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonzi W.A., Sypherd P.S. (1987). The gene and the primary structure of ornithine decarboxylase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 262: 10127–10133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick S., Kutchan T.M. (1999). Molecular cloning and functional expression of O-methyltransferases common to isoquinoline alkaloid and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant J. 17: 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines D.W., Friedman L., McCann P.P. (1988). Apparent ornithine decarboxylase activity, measured by 14CO2 trapping, after frozen storage of rat tissue and rat tissue supernatants. Anal. Biochem. 174: 88–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganfornina M.D., Sánchez D. (1999). Generation of evolutionary novelty by functional shift. Bioessays 21: 432–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gang D.R., Lavid N., Zubieta C., Chen F., Beuerle T., Lewinsohn E., Noel J.P., Pichersky E. (2002). Characterization of phenylpropene O-methyltransferases from sweet basil: Facile change of substrate specificity and convergent evolution within a plant O-methyltransferase family. Plant Cell 14: 505–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golebiewski W.M., Spenser I.D. (1988). Biosynthesis of the lupine alkaloids. II. Sparteine and lupanine. Can. J. Chem. 66: 1734–1748 [Google Scholar]

- Grishin N.V., Osterman A.L., Brooks H.B., Phillips M.A., Goldsmith E.J. (1999). X-ray structure of ornithine decarboxylase from Trypanosoma brucei: The native structure and the structure in complex with alpha-difluoromethylornithine. Biochemistry 38: 15174–15184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häkkinen S.T., Tilleman S., Swiatek A., De Sutter V., Rischer H., Vanhoutte I., Van Onckelen H., Hilson P., Inzé D., Oksman-Caldentey K.M., Goossens A. (2007). Functional characterisation of genes involved in pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis in tobacco. Phytochemistry 68: 2773–2785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanfrey C., Sommer S., Mayer M.J., Burtin D., Michael A.J. (2001). Arabidopsis polyamine biosynthesis: Absence of ornithine decarboxylase and the mechanism of arginine decarboxylase activity. Plant J. 27: 551–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlin-Cognato A., Hoffman E.A., Jones A.G. (2006). Gene cooption without duplication during the evolution of a male-pregnancy gene in pipefish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 19407–19412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann T., Schoofs G., Wink M. (1980). A chloroplast-localized lysine decarboxylase of Lupinus polyphyllus: The first enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of quinolizidine alkaloids. FEBS Lett. 115: 35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T., Tamaki K., Suzuki K., Yamada Y. (1998). Molecular cloning of plant spermidine synthases. Plant Cell Physiol. 39: 73–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herminghaus S., Tholl D., Rügenhagen C., Fecker L.F., Leuschner C., Berlin J. (1996). Improved metabolic action of a bacterial lysine decarboxylase gene in tobacco hairy root cultures by its fusion to a rbcS transit peptide coding sequence. Transgenic Res. 5: 193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi R., Krummel B., Saiki R.K. (1988). A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: Study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 16: 7351–7367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai M.Y., Suzuki H., Yamazaki M., Saito K. (2000). Biochemical and partial molecular characterization of bitter and sweet forms of Lupinus angustifolius, an experimental model for study of molecular regulation of quinolizidine alkaloid biosynthesis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 48: 1458–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L.K., Baldwin J., Akella R., Goldsmith E.J., Phillips M.A. (2004). Multiple active site conformations revealed by distant site mutation in ornithine decarboxylase. Biochemistry 43: 12990–12999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L.K., Brooks H.B., Osterman A.L., Goldsmith E.J., Phillips M.A. (2000). Altering the reaction specificity of eukaryotic ornithine decarboxylase. Biochemistry 39: 11247–11257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern A.D., Oliveira M.A., Coffino P., Hackert M.L. (1999). Structure of mammalian ornithine decarboxylase at 1.6 A resolution: Stereochemical implications of PLP-dependent amino acid decarboxylases. Structure 7: 567–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Kim B.H., Cho Y.D. (1998). Purification and characterization of monomeric lysine decarboxylase from soybean (Glycine max) axes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 354: 40–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinghorn A.D., Balandrin M.F. (1984). Quinolizidine alkaloids of the Leguminosae: Structural types, analysis, chemotaxonomy, and biological activities. In Alkaloids: Chemical and Biological Perspectives, W.S. Pelletier, ed (New York: Wiley/Interscience), pp 105–148 [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima A., Asatsuma S., Okada H., Hamada Y., Kaneko K., Nanjo Y., Kawagoe Y., Toyooka K., Matsuoka K., Takeuchi M., Nakano A., Mitsui T. (2009). The rice α-amylase glycoprotein is targeted from the Golgi apparatus through the secretory pathway to the plastids. Plant Cell 21: 2844–2858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebbers E., Seutinck J., Herdies L., Cashmore A.R., Timko M.P. (1988). Four genes in two diverged subfamilies encode the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase small subunit polypeptides of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 11: 745–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutchan T.M., Frick S., Weid M. (2008). Engineering plant alkaloid biosynthetic pathways: Progress and prospects. In Advances in Plant Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, H.J. Bohnert, H. Nguyen, and N.G. Lewis, eds (Amsterdam: Elsevier), pp. 283–310 [Google Scholar]

- Kwak S.H., Lee S.H. (2001). The regulation of ornithine decarboxylase gene expression by sucrose and small upstream open reading frame in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill). Plant Cell Physiol. 42: 314–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Michael A.J., Martynowski D., Goldsmith E.J., Phillips M.A. (2007b). Phylogenetic diversity and the structural basis of substrate specificity in the beta/alpha-barrel fold basic amino acid decarboxylases. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 27115–27125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.J., Pate J.S., Harris D.J., Atkins C.A. (2007a). Synthesis, transport and accumulation of quinolizidine alkaloids in Lupinus albus L. and L. angustifolius L. J. Exp. Bot. 58: 935–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.S., Cho Y.D. (2001). Identification of essential active-site residues in ornithine decarboxylase of Nicotiana glutinosa decarboxylating both L-ornithine and L-lysine. Biochem. J. 360: 657–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leistner E., Spenser I.D. (1973). Biosynthesis of the piperidine nucleus. Incorporation of chirally labeled (1-3H)cadaverine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95: 4715–4725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazelis M., Miflin B.J., Pratt H.M. (1976). A chloroplast-localized diaminopimelate decarboxylase in higher plants. FEBS Lett. 64: 197–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael A.J., Furze J.M., Rhodes M.J., Burtin D. (1996). Molecular cloning and functional identification of a plant ornithine decarboxylase cDNA. Biochem. J. 314: 241–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J.P. (2008). Indolizidine and quinolizidine alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 25: 139–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T., Kurose T., Hino T., Tanaka K., Kawamukai M., Niwa Y., Toyooka K., Matsuoka K., Jinbo T., Kimura T. (2007). Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104: 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K., Hashimoto T., Yamada Y. (1993). Two tropinone reductases with different stereospecificities are short-chain dehydrogenases evolved from a common ancestor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90: 9591–9595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noji M., Inoue K., Kimura N., Gouda A., Saito K. (1998). Isoform-dependent differences in feedback regulation and subcellular localization of serine acetyltransferase involved in cysteine biosynthesis from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 32739–32745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober D., Hartmann T. (1999). Homospermidine synthase, the first pathway-specific enzyme of pyrrolizidine alkaloid biosynthesis, evolved from deoxyhypusine synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 14777–14782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober D., Kaltenegger E. (2009). Pyrrolizidine alkaloid biosynthesis, evolution of a pathway in plant secondary metabolism. Phytochemistry 70: 1687–1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohe M., Scoccianti V., Bagni N., Tassoni A., Matsuzaki S. (2009). Putative occurrence of lysine decarboxylase isoforms in soybean (Glycine max) seedlings. Amino Acids 36: 65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkama-Ohtsu N., Oikawa A., Zhao P., Xiang C., Saito K., Oliver D.J. (2008). A gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase-independent pathway of glutathione catabolism to glutamate via 5-oxoproline in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 148: 1603–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmiya S., Saito K., Murakoshi I. (1995). Lupine alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology. Vol. 47, G.A. Cordell, ed (London: Academic Press), pp 1–114 [Google Scholar]

- Okada T., Hirai M.Y., Suzuki H., Yamazaki M., Saito K. (2005). Molecular characterization of a novel quinolizidine alkaloid O-tigloyltransferase: cDNA cloning, catalytic activity of recombinant protein and expression analysis in Lupinus plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 46: 233–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksman-Caldentey K.M., Inzé D. (2004). Plant cell factories in the post-genomic era: New ways to produce designer secondary metabolites. Trends Plant Sci 9: 433–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oram R.N. (1983). Selection for higher seed yield in the presence of the deleterious low alkaloid allele Iucundus in Lupinus angustifolius L. Field Crops Res. 7: 169–180 [Google Scholar]

- Pegg A.E. (1988). Polyamine metabolism and its importance in neoplastic growth and a target for chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 48: 759–774 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichersky E., Lewinsohn E. (2011). Convergent evolution in plant specialized metabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62: 549–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K., Koike Y., Suzuki H., Murakoshi I. (1993). Biogenic implication of lupin alkaloid biosynthesis in bitter and sweet forms of Lupinus luteus and L. albus. Phytochemistry 34: 1041–1044 [Google Scholar]

- Saito K., Murakoshi I. (1995). Chemistry, biochemistry and chemotaxonomy of lupine alkaloids in the Leguminosae. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Vol. 15, Structure and Chemistry (Part C), A.U. Rahman, ed (Amsterdam: Elsevier), pp 519–550 [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., David W. (2001). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press) [Google Scholar]

- Sandmeier E., Hale T.I., Christen P. (1994). Multiple evolutionary origin of pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent amino acid decarboxylases. Eur. J. Biochem. 221: 997–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato F., Inai K., Hashimoto T. (2007). Metabolic engineering in alkaloid biosynthesis: Case studies in tyrosine- and putrescine-derived alkaloids. In Applications of Plant Metabolic Engineering, R. Verpoorte, A.W. Alfermann, and T.S. Johnson, eds (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer), pp 145–173 [Google Scholar]

- Shoji T., Hashimoto T. (2008). Why does anatabine, but not nicotine, accumulate in jasmonate-elicited cultured tobacco BY-2 cells? Plant Cell Physiol. 49: 1209–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simillion C., Vandepoele K., Van Montagu M.C., Zabeau M., Van de Peer Y. (2002). The hidden duplication past of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 13627–13632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S.J., Johnson R., Hamill J.D. (2004). Analysis of wound-induced gene expression in Nicotiana species with contrasting alkaloid profiles. Funct. Plant Biol. 31: 721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepansky A., Less H., Angelovici R., Aharon R., Zhu X., Galili G. (2006). Lysine catabolism, an effective versatile regulator of lysine level in plants. Amino Acids 30: 121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack D., Becher A., Brall S., Witte L. (1991). Quinolizidine alkaloids and the enzymatic syntheses of their cinnamic and hydroxycinnamic acid ester in Lupinus angustifolius and L. luteus. Phytochemistry 30: 1493–1498 [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Murakoshi I., Saito K. (1994). A novel O-tigloyltransferase for alkaloid biosynthesis in plants. Purification, characterization, and distribution in Lupinus plants. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 15853–15860 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatsuka Y., Onoda M., Sugiyama T., Muramoto K., Tomita T., Kamio Y. (1999). Novel characteristics of Selenomonas ruminantium lysine decarboxylase capable of decarboxylating both L-lysine and L-ornithine. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63: 1063–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]