Abstract

Protein misassembly into aggregate structures, including cross-β-sheet amyloid fibrils, is linked to diseases characterized by the degeneration of post-mitotic tissue. While amyloid fibril deposition in the extracellular space certainly disrupts cellular and tissue architecture late in the course of amyloid diseases, strong genetic, pathological and pharmacologic evidence suggests that the process of amyloid fibril formation itself, known as amyloidogenesis, likely causes these maladies. It seems that the formation of oligomeric aggregates during the amyloidogenesis process causes the proteotoxicity and cytotoxicity characteristic of these disorders. Herein, we review what is known about the genetics, biochemistry and pathology of familial amyloidosis of Finnish Type (FAF) or gelsolin amyloidosis. Briefly, autosomal dominant D187N or D187Y mutations compromise Ca2+ binding in domain 2 of gelsolin, allowing domain 2 to sample unfolded conformations. When domain 2 is unfolded, gelsolin is subject to aberrant furin endoproteolysis as it passes through the Golgi on its way to the extracellular space. The resulting C-terminal 68kDa fragment (C68) is susceptible to extracellular endoproteolytic events, possibly mediated by a matrix metalloprotease, affording 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments of gelsolin. These amyloidogenic fragments deposit systemically, causing a variety of symptoms, including corneal lattice dystrophy and neurodegeneration. The first murine model of the disease recapitulates the aberrant processing of mutant plasma gelsolin, amyloid deposition, and the degenerative phenotype. We use what we have learned from our biochemical studies, as well as insight from mouse and human pathology to propose therapeutic strategies that may halt the progression of FAF.

Keywords: Familial amyloidosis of Finnish type, calcium binding, amyloidogenesis, aberrant proteolysis, furin, gelsolin amyloid disease

Introduction

There are as many as 50 human degenerative diseases linked to the aggregation of distinct proteins (Cohen and Kelly, 2003, Kelly, 1998, Dobson, 2003, Selkoe, 2003, Pepys, 2006). These maladies are referred to as amyloid diseases, so-named after the cross-β-sheet aggregates or amyloid structures that are found outside or within the cells of amyloid disease patients (Petkova et al., 2002, Shewmaker et al., 2009, Tycko, 2003, Luhrs et al., 2005, Nelson et al., 2005, Sawaya et al., 2007, Blake et al., 1996, Choo et al., 1996). Amyloid fibrils are just one of a spectrum of aggregate structures found in these patients (Lashuel et al., 2002, Lambert et al., 1998, Wang et al., 2002). Other aggregate morphologies include micelle-like spherical structures that form early in the process of amyloid fibril formation (Lomakin et al., 1997, Sabate and Estelrich, 2005, Lee et al., 2011).

Compelling evidence demonstrates that many of the mutations that predispose individuals to early onset amyloid disease function by increasing the probability of protein aggregation (Tanzi and Bertram, 2005, Selkoe, 2003, Hammarstrom et al., 2001, Hammarstrom et al., 2003, Kelly, 1996, Kelly, 1998). Most of these mutations either increase the concentration of an intrinsically disordered amyloidogenic protein, the concentration of a partially folded amyloidogenic intermediate, or the concentration of an amyloidogenic protein fragment (Sekijima et al., 2005, Tanzi and Bertram, 2005, Chen et al., 2001, Huff et al., 2003b, Page et al., 2004, Page et al., 2005, Selkoe, 2003). The concentration of the amyloidogenic conformation or disordered polypeptide is very important since aggregation often exhibits a high order concentration dependence (Powers and Powers, 2008, Ferrone, 1999). Amyloid promoting mutations can include gene duplication or gene triplication mutations, which proportionally increase the concentration of a wild-type amyloidogenic protein and thus increase the risk of diseases, like in Parkinson’s disease (Chartier-Harlin et al., 2004, Ibanez et al., 2004, Singleton et al., 2003). Point mutations generally destabilize normally folded proteins, leading to a higher concentration of partially denatured states that more efficiently aggregate, as in the transthyretin amyloid diseases (Kelly, 1996, Kelly, 1998, Sekijima et al., 2005, Hammarstrom et al., 2002, Hammarstroem et al., 2003, Hurshman Babbes et al., 2008, Booth et al., 1997, Jiang et al., 2001, Johnson et al., 2005). These partially folded states have aggregation-prone sequences that are exposed and have a high propensity to aggregate because of the high β-sheet propensity of the exposed residues, their hydrophobicity and/or their lack of charge (Chiti et al., 2003, Fernandez-Escamilla et al., 2004). In addition, point mutations can also destabilize normally folded proteins leading to a higher concentration of partially denatured protease-sensitive states, affording a higher concentration of an amyloidogenic protein fragment, as in the case of gelsolin amyloidosis—the subject of this review (Chen et al., 2001, Page et al., 2005, Kangas et al., 2002, Huff et al., 2003a, Huff et al., 2003b, Page et al., 2004, Ratnaswamy et al., 2001). Finally, point mutations in either a precursor protein endoprotease substrate or in the endoprotease itself that processes an intrinsically disordered protein can afford a higher concentration of an amyloidogenic fragment or generate alternative polypeptide fragments with increased amyloidogenic potential, as in the case of Alzheimer’s disease where mutations in APP or γ-secretase lead to more aggregation-prone Aβ1–42 relative to Aβ1–40 (Tanzi and Bertram, 2005, Selkoe, 2003).

Emerging evidence suggests that the process of amyloid fibril formation, known as amyloidogenesis, causes the degeneration of post-mitotic tissue characteristic of the amyloid diseases (Johnson et al., 2005, Bucciantini et al., 2002, Hammarstrom et al., 2001, Hammarstrom et al., 2003, Lashuel et al., 2002, Walsh et al., 2002, Walsh and Selkoe, 2007). While the amyloid fibrils in the extracellular space can certainly cause pathology by disrupting cellular and tissue architecture late in the course of an amyloid disease, most evidence suggests that it is the proteotoxicity of the oligomers formed in the process of amyloidogenesis that appears to be the main cause of cytotoxicity leading to these maladies (Bucciantini et al., 2002, Lashuel et al., 2002, Lambert et al., 1998, Wang et al., 2002, Walsh et al., 2002, Walsh and Selkoe, 2007). There is now good reason to believe that if the molecular underpinnings of the process of amyloidogenesis can be understood, that amyloidogenesis can be halted and disease progression arrested (Hammarstrom et al., 2001, Hammarstrom et al., 2003, Hurshman Babbes et al., 2008, Johnson et al., 2005, Sekijima et al., 2005). This has proven to be the case in the transthyretin amyloid diseases. In these diseases, pharmacologic treatment with the transthyretin kinetic stabilizer, Tafamidis, halts the progression of peripheral and autonomic neuropathy by inhibiting the process of amyloidogenesis (Coelho et al., 2011). There is also strong genetic evidence that the process of transthyretin amyloidogenesis causes the transthyretin amyloid diseases. Interallelic transsuppression in compound heterozygotes or the mixing of trans-suppressor subunits with destabilizing disease-associated transthyretin subunits also ameliorates transthyretin amyloid diseases in families with these mutations on distinct alleles—by making the kinetic barrier for tetramer dissociation, the rate limiting step of transthyretin amyloidogenesis, insurmountable (Hammarstrom et al., 2001, Hammarstrom et al., 2003).

It is highly desirable to understand how the process of amyloid fibril formation causes human amyloid diseases. However this is not understood for any human amyloid disease at this juncture, even though there are plenty of hypotheses about how the process of amyloidogenesis leads to cytotoxicity. One hypothesis suggests that the hydrophobic surfaces exposed in preamyloid intermediate aggregate structures sequester critical cellular proteins, compromising multiple cellular signaling pathways and physiological processes (Olzscha et al., 2011). The resulting loss of functions compromise the integrity of post-mitotic tissue that does not easily regenerate (Olzscha et al., 2011). Others hypothesize that amyloid and its precursors cause these diseases by the gain of a new aberrant cellular function, such as the formation of unregulated ion channels or by altering the regulation of cellular trafficking (Falzone et al., 2010, Her and Goldstein, 2008, Shah et al., 2009, Stokin and Goldstein, 2006). Still others believe that the displacement of tissue by amyloid fibrils leads to these maladies (Pepys, 2006). Of course, these proteotoxicity hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and much more work is required to better understand the etiology of these maladies.

A variety of different types of proteins can form amyloid fibrils in humans. Some amyloid precursors are intrinsically disordered proteins, such as the first domain of the Huntington protein. In contrast, other amyloidogenic proteins normally adopt well-defined folded tertiary and/or quaternary structures, such as transthyretin, which must undergo dramatic changes in its conformation to aggregate (Kelly, 1996, Kelly, 1998, Dobson, 2003, Selkoe, 2003, Cohen and Kelly, 2003, Fandrich et al., 2001). Amyloidogenesis by wild type proteins or their fragments appear to cause sporadic amyloid diseases. Aging is the most significant risk factor for both sporadic and inherited degenerative disorders (Cohen et al., 2009). This is most likely the result of aging-associated deficiencies in protein homeostasis (proteostasis) or age-associated deficiencies in the ability to activate stress-responsive signaling pathways that match proteostasis capacity with demand (Cohen et al., 2009, Balch et al., 2008).

Herein, we review the literature that leads to our understanding of the genetic and biochemical roots of gelsolin amyloidosis, or familial amyloidosis of Finnish Type (FAF). In this inherited monogenic disease, misfolding of mutated gelsolin in the Golgi compartment during cellular trafficking results in aberrant endoproteolysis that produces a gelsolin fragment that is cleaved again in the extracellular space, affording fragments that are amyloidogenic (Huff et al., 2003a). While FAF is a rare disease, advances in understanding its pathology and development of therapeutic interventions for it can have a broad impact in all amyloid diseases that affect post-mitotic tissue, including the neurodegenerative diseases of the brain such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, which represent some of the most daunting public health challenges of our era (Tanzi and Bertram, 2005, Selkoe, 2003).

History and Epidemiology of Gelsolin Amyloidosis

Familial amyloidosis of Finnish type was first reported by Jouko Meretoja in 1969. Ten patients, from three families of Finnish descent, were studied and shown to have similar symptoms that were dominantly inherited: lattice dystrophy of the cornea and a cranial and peripheral neuropathy (Meretoja, 1969). In subsequent years, additional FAF patients were identified—most were from isolated population groups from two geographical clusters in southeastern Finland (Meretoja, 1973). Historically, these population groups were largely immobile and experienced only modest immigration, and are therefore thought to be enriched for a number of rare disease causing genes. Today, there are estimated to be approximately 1000 carriers of FAF in Finland. Since the first report of the disease, patients have been found in many countries, including the United States, Japan, Portugal, England, Germany, Spain, France, Brazil, Sweden, Denmark, the Czech Republic, and Iran. (Conceicao et al., 2003, Pihlamaa et al., 2011, Huerva et al., 2007, Stewart et al., 2000, Ikeda et al., 2007, Tanskanen et al., 2007, Chastan et al., 2006, Contegal et al., 2006, Luettmann et al., 2010, Ardalan et al., 2007, Makioka et al., 2010, Kiuru, 1998, Carrwik and Stenevi, 2009, Felix et al., 2008, Plante-Bordeneuve and Said, 2011). Many of the patients studied had no Finnish ancestors, suggesting multiple founders of the disease. Therefore, there may be carriers of FAF in many families and ethnicities worldwide. As with most rare diseases lacking a therapeutic strategy, it is likely that the disease is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed.

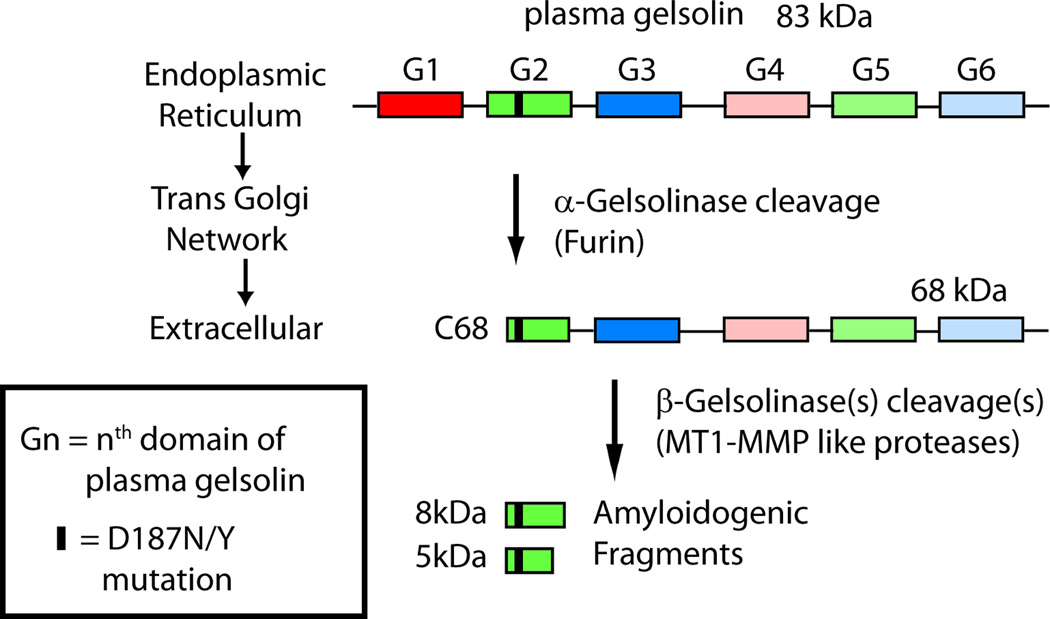

The amyloid deposits in FAF patients derive from the protein product of the gelsolin gene (Maury, 1991, Haltia et al., 1990). The gelsolin gene is alternatively spliced to form cytoplasmic and secreted variants, and it was discovered that the amyloidogenic fragments derive from aberrant processing of only the secreted form of gelsolin, also known as plasma gelsolin (Kangas et al., 1996). A G654A or G654T DNA mutation in the gelsolin coding area (q32–34) of chromosome 9, which changes an aspartate at position 187 in the gelsolin protein to an asparagine or tyrosine (D187N/Y) residue respectively, appears to cause FAF by leading to gelsolin fragment formation and amyloidogenesis (Figure 1) (de la Chapelle et al., 1992, Paunio et al., 1994). This mutation eliminates one of the four calcium binding ligands in the second domain of plasma gelsolin, substantially compromising calcium binding. This allows domain 2 of mutant plasma gelsolin to sample unfolded conformations, during which it can be aberrantly proteolytically processed, first in the Golgi and later outside the cell, to form 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments that deposit systemically (Figure 1) (Chen et al., 2001, Huff et al., 2003b, Page et al., 2004, Ratnaswamy et al., 2001, Page et al., 2005, Huff et al., 2003a). One copy of the mutant allele appears to result in complete penetrance of FAF. Therefore, FAF appears to be a gain-of-toxic-function disease.

Figure 1.

Scheme outlining the D187N/Y plasma gelsolin pathogenic proteolytic cascade. The 6 domains of gelsolin are depicted by rectangles with the D187N/Y mutation highlighted in red. A portion of the mutant gelsolin is cleaved within domain 2 by furin in the trans-Golgi network to generate a 68 kDa protein (C68). Upon secretion, the C68 is further cleaved by proteinases in the extracellular matrix, such as matrix metalloproteases, to produce the 8- and 5-kDa amyloidogenic gelsolin fragments that deposit systemically.

Clinical Presentations of Familial Amyloidosis of Finnish Type

The first sign of FAF, which often presents in the third decade of life, is corneal lattice dystrophy resulting from gelsolin amyloid deposition in the eye (Meretoja, 1973). Gelsolin fragment amyloid deposition can be detected by Congo red binding, which gives the amyloid fibrils a characteristic apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light. Congo red histopathology reveals deposition in the cornea (particularly in the anterior and middle stroma), conjunctiva, the sclera, and in the nerves and vessels of the eye. Because the amyloid is found in both vascular and avascular structures, it is thought that local synthesis and cleavage, most notably in the cornea, contributes to the eye pathology in FAF (Carrwik and Stenevi, 2009, Kivela et al., 1994).

As the disease progresses, amyloid begins to affect the cranial and peripheral nerves, causing a slowly progressive polyneuropathy. A peripheral paresis of the area innervated by the upper branch of the facial nerve, followed by a slow progression to the area innervated by the lower branches is almost universally found in FAF patients (Meretoja, 1973). In addition, other cranial nerves, including the trigeminal nerve, are also often affected, resulting in reduced sensation (Kiuru, 1998). Reduced sensation, along with the amyloid deposition in the cornea of the eye causes many FAF subjects to have severely decreased corneal sensitivity and a greatly reduced or absent corneal reflex (Carrwik and Stenevi, 2009, Rosenberg et al., 2001). With disease progression, involvement of the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves is often seen, resulting in tongue atrophy and fasciculations, dysarthria, and drooling (Kiuru, 1998). A peripheral, primarily sensory neuropathy is also observed, particularly in the lower extremities, and ischemia due to amyloid deposition in vasculature is apparently involved (Kiuru-Enari et al., 2002). Frequently, gelsolin fragment amyloid deposition in the autonomic nervous system causes autonomic dysfunction, which often presents as orthostatic hypotension (Kiuru et al., 1994, Makioka et al., 2010). It is likely that amyloid deposition in the vasculature also reduces arterial compliance, exacerbating dysregulation of blood pressure.

Gelsolin amyloid also deposits in the basement membrane of the skin, resulting in dermatologic abnormalities, including cutis laxa, or thickened and loosened skin with reduced elasticity and resilience (Kiuru-Enari et al., 2005). Additionally, loss of body hair, intracutaneous bleeding, and dry, itchy skin is often observed due to gelsolin fragment amyloid deposition in sweat glands and hair follicles. These symptoms, in conjunction with the facial paresis, often give the face a characteristic drooping, mask-like appearance (Kiuru-Enari et al., 2005).

In the later stages of the disease, proteinuria is often observed, indicating amyloid deposition in the glomeruli of the kidneys. In fact, patients homozygous for the amyloidogenic mutation of gelsolin develop a severe nephrotic syndrome and, ultimately, end stage renal failure (Maury, 1993). Cardiac involvement, including conduction abnormalities, is also sometimes seen (Chastan et al., 2006, Kiuru et al., 1994). Ultimately, further amyloid deposition in vital organs and microvasculature can become life threatening, and the primary causes of death are typically nephrotic syndrome, pneumonia from aspiration due to bulbar muscle dysfunction, or cerebral hemorrhage likely from cerebral angiopathy (Kiuru, 1998). The mortality rate of FAF patients is thought to be slightly higher than age-matched controls, but because the disease is so rare, conclusive epidemiological studies have not been performed. In addition, the natural history of the disease, including the frequency with which each of the described symptoms present is unknown because of the rarity of the disease. However, there is clearly a severe morbidity associated with FAF (Carrwik and Stenevi, 2009, Pihlamaa et al., 2011).

There is no cure for or treatment to ameliorate the underlying etiology of FAF currently. Management of FAF patients is mostly focused on alleviating symptoms as opposed to altering the underlying biochemistry leading to the pathology. Because many of the early symptoms are ocular, the ophthalmologist plays a vital role in detecting and managing the disease (Carrwik and Stenevi, 2009). Lubricating eye drops are often prescribed to reduce the risk of corneal erosions and abrasions, especially because of the reduced sensitivity of the cornea. Moreover, secondary glaucoma is often observed in FAF patients, so management of intraocular pressure is important (Carrwik and Stenevi, 2009). As the disease progresses, many patients opt to undergo plastic and reconstructive surgery to improve the facial appearance caused by amyloid deposition in the basement membrane of the skin. Brow lifts to alleviate brow ptosis and blepharoplasties to remove thickened skin in the eyelids are often performed, along with forehead lifts and face lifts (Pihlamaa et al., 2011). Multiple surgeries are often required as FAF progresses. The architecture of the skin is often disturbed, making fairly routine procedures challenging in FAF patients (Pihlamaa et al., 2011). There is currently no diagnostic test available for identifying FAF except for sequencing the gelsolin gene, a procedure not routinely performed if there is no familial history. Therefore, the diagnosis of gelsolin amyloidosis is probably often missed. However, good gelsolin antibodies exist which can be employed by experienced pathologists to make a preliminary diagnosis of FAF from a biopsy.

The Physiological Functions of Gelsolin

The amyloid that deposits in FAF derives from a secreted fragment of mutant plasma gelsolin (de la Chapelle et al., 1992, Maury, 1991). Gelsolin was discovered as a cytosolic calcium sensitive protein that regulates the gel-sol transition of actin required for macrophage locomotion, and hence its name (Yin and Stossel, 1979). There are both intracellular and secreted forms of human gelsolin, which both derive from the same gene product—a 70 kb gene on chromosome 9 that contains 14 exons. Alternative splicing leads to the formation of cytosolic and secreted forms of gelsolin (Kwiatkowski et al., 1988, Kwiatkowski et al., 1986, Yin et al., 1984). The 81 kDa intracellular splice variant lacks the leader sequence at the N-terminus that directs the 83 kDa secreted variant into the endoplasmic reticulum, where folding generally occurs leading to eventual secretion into the bloodstream (Kwiatkowski et al., 1986). Both the 81 and 83 kDa variants of gelsolin bind to actin to manipulate the transition from fibrillar to soluble actin. The binding of gelsolin to actin fibrils changes the conformation of actin, kinking the actin fibril and reducing intermolecular contacts between actin fibrils. The actin fibril is thus severed, and gelsolin binds to the severed end, capping it and preventing it from repolymerizing (Sun et al., 1999). The main function of intracellular gelsolin is to remodel the actin cytoskeleton, while the extracellular variant’s main role is to scan the bloodstream for actin fibrils that are released by injured tissue into the bloodstream and to bind them in a scavenger mode to prevent actin from increasing blood viscosity (Bucki et al., 2008b, Sun et al., 1999). In addition to being regulated by calcium binding, some bioactive lipids, including phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, have been demonstrated to bind to gelsolin. These lipids may insert into the actin-gelsolin interface, also regulating the activity of gelsolin (Liepina et al., 2003).

Gelsolin also seems to play a vital role in modulating inflammatory responses (Lee et al., 2007, Bucki et al., 2008a, Bucki et al., 2008b). Circulating actin fibrils are likely to be toxic and may be a marker for cellular injury in sepsis. Exogenous administration of plasma gelsolin reduces the mortality of septic mice. Plasma gelsolin’s protective effect may be due to reducing circulating actin fibrils and shifting cytokine profiles to an anti-inflammatory condition (Lee et al., 2007). Further, because of gelsolin’s ability to bind to bioactive lipids, it may bind other pro-inflammatory mediators and lipids from bacterial membranes. Once bound to gelsolin, these pro-inflammatory lipids are hypothesized to be less able to activate inflammatory responses. Moreover, because gelsolin is complexed with bioactive lipids, it is less able to bind to and sever actin fibrils, with the result of containing the inflammatory response (Bucki et al., 2008a, Bucki et al., 2010, Bucki et al., 2008b).

Even though gelsolin fragments are amyloidogenic, full length gelsolin has been hypothesized to play a role in binding to other amyloidogenic peptides, including amyloid β (Aβ), the amyloidogenic fragment of the amyloid precursor protein, whose aggregation apparently leads to Alzheimer’s disease. It was demonstrated that Aβ binds to both cytosolic and plasma gelsolin at two specific sites and that this complex can be immunoprecipitated from biological material (Chauhan et al., 2008, Chauhan et al., 1999, Ji et al., 2008). Additionally, gelsolin is able to inhibit fibrillization of both synthetic Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, as well as defibrillize preformed Aβ fibrils (Chauhan et al., 2008, Ray et al., 2000). Peripheral delivery of a plasmid containing a gene for plasma gelsolin has been demonstrated to reduce brain Aβ in two separate mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (Hirko et al., 2007). Interestingly, Alzheimer’s disease patients display 14 significantly lower plasma gelsolin levels compared to non-demented age-matched controls. Moreover, plasma gelsolin levels have been demonstrated to correlate with the rate of disease progression (Guentert et al., 2010). Overall, these results suggest that plasma gelsolin may play a role in protecting against non-gelsolin amyloid-related toxicity.

The normal concentration of plasma gelsolin in blood is 200–300 µg/mL. Although plasma gelsolin is secreted by several cell types, muscle cells appear to be the major source of plasma gelsolin, devoting 0.5 to 3% of their biosynthetic activity to producing plasma gelsolin (Kwiatkowski et al., 1988). Given that gelsolin makes up a large portion of the plasma proteome and seemingly has such critical biological functions (modulating the gel-sol transition both intra-and extracellularly), one would think that gelsolin would be a required protein. Curiously, however, gelsolin knockout mice exhibit a normal development and lifespan, exhibiting only a mild prolonged bleeding time phenotype and abnormally slowly migrating neutrophils and fibroblasts. The reason for the mild phenotype is likely due to the redundant functions of other proteins (Witke et al., 1995). In addition, some FAF patients are known to be homozygous for the D187N gelsolin mutation, and while disease progression in these patients occurred earlier and with more severe nephropathy, they did not seem to exhibit any unusual symptoms that could be attributed to a loss-of-function phenotype (Maury, 1993). Therefore, all evidence indicates that the symptoms of FAF described above appear to derive from a gain-of-toxic-function derived from mutant plasma gelsolin fragment aggregation.

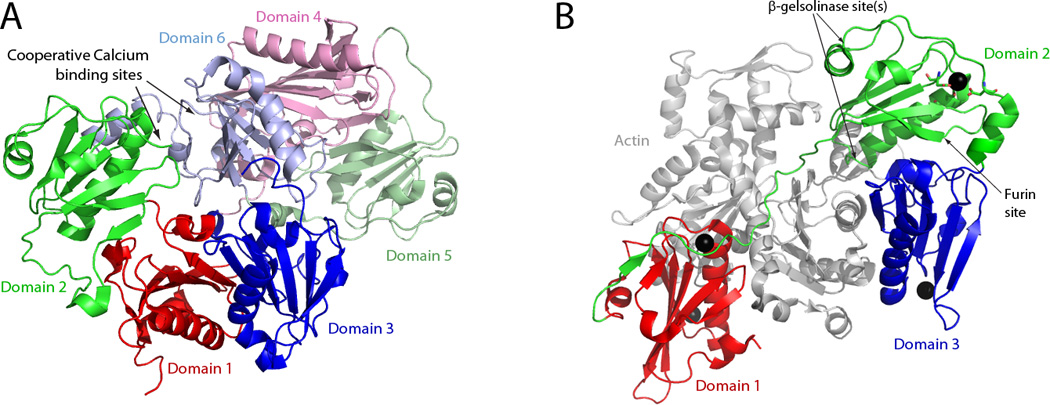

The Multiple Structures of Full-length Gelsolin

While the secreted variant of gelsolin has an N-terminal extension sequence, the overall structures of the intracellular and extracellular variants of gelsolin appear to be very similar. Gelsolin is a six domain protein (Figure 2) that appears to have evolved from a gene triplication process followed by an additional duplication (Kwiatkowski et al., 1986). Each of the domains of gelsolin (G1–G6) have a homologous structure featuring a β-sheet composed of five β-strands sandwiched between two α-helices (Figure 2) (Burtnick et al., 1997). A significant difference in the two gelsolin variants is that each of 5 cysteines present are in the free thiol form in the cytosolic variant, while only three are in the free thiol form in the secreted variant. The secreted variant has a disulfide bond comprising cysteines 188 and 201 in domain 2. In addition, the cytoplasmic and plasma forms exhibit slightly different protease sensitivities, suggesting that there may be some slight quaternary and/or tertiary structural differences between the two forms (Wen et al., 1996).

Figure 2.

Gelsolin structure and activation by calcium binding. (A) Structure of calcium-free human gelsolin (PDB: 3FFN). Domains 1, 2, and 3 are shown in red, green, and blue respectively, and domains 4, 5, and 6 are shown in light red, light green, and light blue respectively. All of the domains are arranged in a compact fashion around domain 6, which has a C-terminal helix that interacts with both domains 2 and 4. (B) Structure of domains 1–3 of calcium-activated human gelsolin with G1–G3 bound to actin (shown in grey) (PDB:3FFK). Domains 1, 2, and 3 are once again shown in red, green, and blue respectively. The binding of calcium by domain 2 of gelsolin alters its conformation to allow new interactions with domain 3 (cf. the orientation of the red, blue and green domains in A vs. B). The cleavage sites of furin and the β-gelsolinase(s) are indicated. The residues that coordinate calcium binding in domain 2 are shown in ball-and-stick format (see Figure 3A for an expanded view). The structures depicted are based on the crystal structures as described by (Nag et al., 2009).

Calcium binding plays a critical role in the activation and regulation of gelsolin. There are eight calcium binding sites in human plasma gelsolin. Two sites (in G1 and G4) are type 1 calcium binding sites because the calcium is coordinated by residues from both actin and gelsolin. The six other calcium binding sites (one in each domain) are of the type 2 variety, in that the calcium is coordinated by residues from gelsolin alone (Choe et al., 2002).

In the absence of calcium, domains G1–G5 are arranged in a compact fashion around domain G6 with all of the actin-binding sites obscured (Figure 2A). For gelsolin to bind actin and perform its capping and severing abilities, it must first be activated by calcium binding. Calcium binding causes gelsolin to undergo a structural change that increases its radius of gyration and maximum linear dimension, essentially opening it up (Figure 2B) (Ashish et al., 2007, Khaitlina and Hinssen, 2002, Robinson et al., 1999). In calcium-free gelsolin, a C-terminal helical “latch” in G6 is bent, allowing for interaction with G2 and G4 (Figure 2A) (Wang et al., 2009). At the interface of G2 and G6 in the calcium-free structure, there is a highly negatively charged patch that comprises the two cooperative type 2 calcium binding sites of these domains (Nag et al., 2009). These sites have the highest affinity for calcium. Calcium binding at these sites breaks the G2–G6 interface and also straightens the C-terminal helical latch in G6 (Figure 2B) (Choe et al., 2002, Wang et al., 2009). A series of conformational rearrangements then occurs: A continuous β-sheet between G1 and G3 is ruptured (cf. Figure 2A to 2B) and a strand from the β-sheet in G2 is removed with its subsequent reattachment to the β-sheet in G1, thus creating a new interface between G2 and G3 (Figure 2B) (Nag et al., 2009). Binding of calcium to the type 2 binding sites in the other domains stabilizes gelsolin in its open, active conformation (Figure 2B) (Ashish et al., 2007, Lueck et al., 2000, Roustan et al., 2007).

A G654A or G654T Mutation Causes FAF by Compromising Ca+2 Binding

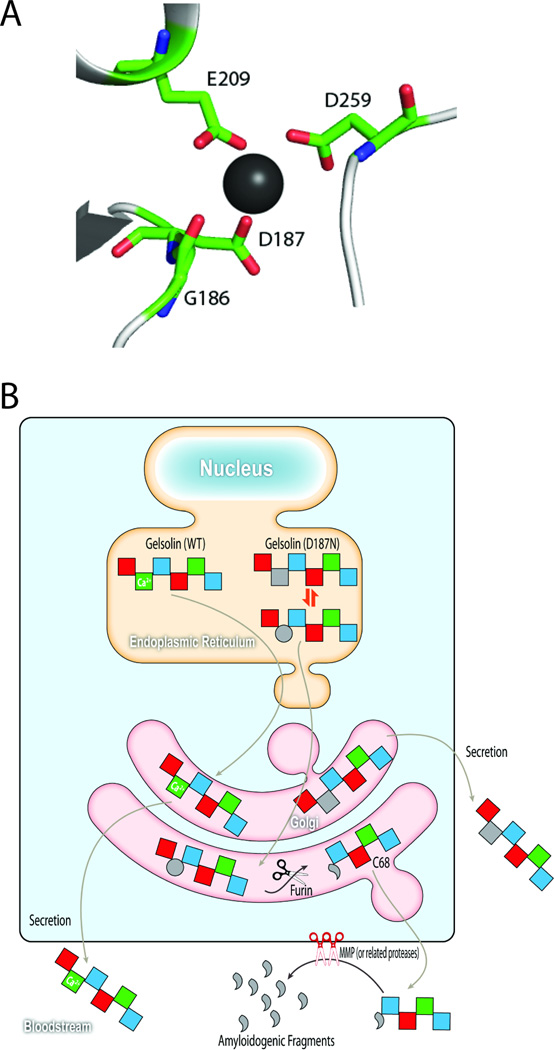

Calcium ions often bind to proteins at sites where they can be coordinated by backbone carbonyls and/or side chain carboxylates. The calcium binding site in the second domain of gelsolin is no exception (Figure 3A). Calcium is coordinated by the backbone carbonyl of glycine at position 186, and the side chain carboxylates of aspartates at positions 187 and 259, and the glutamate at position 209 (Figure 3A) (Kazmirski et al., 2002). The G654A or G654T DNA point mutations change the aspartate at position 187 to either an asparagine or tyrosine. As a result, domain 2 (G2) in the D187N/Y variants does not bind calcium at physiological calcium concentrations and therefore does not undergo the calcium-induced conformational changes discussed above as readily. Moreover, there is a loss of cooperativity with the sixth domain (Chen et al., 2001, Huff et al., 2003b, Kazmirski et al., 2002). Calcium is still able to bind to the other domains of D187N/Y gelsolin, ultimately allowing it to undergo the necessary conformational changes and arrive at its open, activated conformation (Nag et al., 2009). Therefore, D187N/Y gelsolin is able to retain its actin manipulating activity, but it is likely that without the cooperative binding of calcium to spring open the latch, D187N/Y gelsolin spends a longer time in an intermediate conformation between the compact calcium-free inactive state and the open, activated state.

Figure 3.

D187N/Y mutation compromises Ca+2 binding in domain 2, altering its conformation to become protease sensitive. (A) In domain 2 of plasma gelsolin, a calcium ion (depicted by the black sphere) is coordinated by the backbone carbonyl of G186, and the carboxylates from the side chains of D187, E209, and D259. The D187N/Y mutation removes one of these Ca+2-binding side chains, making calcium unable to bind at this site at physiological concentrations. (B) As D187N/Y plasma gelsolin travels through the secretory pathway to be secreted into the bloodstream, domain 2 samples intermediate conformations between the unfolded (grey circle) and folded states (grey square), with unfolded and partially folded states being susceptible to furin cleavage in the trans Golgi. Once cleaved by furin, the secreted C68 fragment is susceptible to metalloprotease cleavage or endoproteolysis by other related proteases in the extracellular matrix, generating the 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments. Wild type gelsolin retains its ability to bind calcium and is protected from furin cleavage.

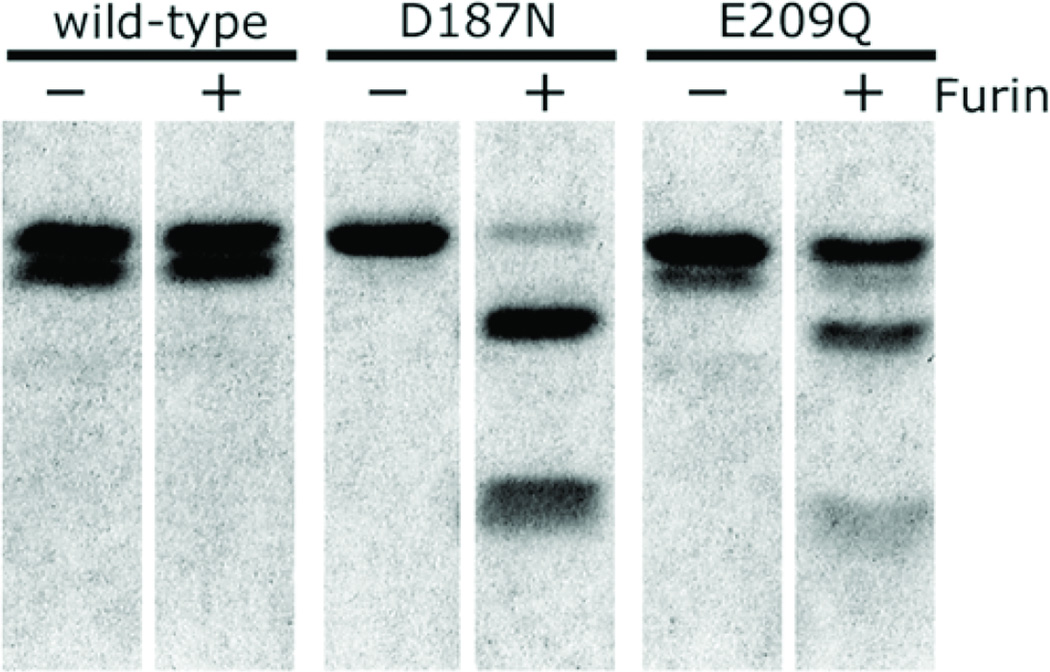

A furin cleavage site exists in the second domain of gelsolin and is C terminal to R169-V170-V171-R172 (Chen et al., 2001). In both the calcium-free compact inactive state and calcium-bound active state, the furin cleavage site within G2 is obscured. However, the furin cleavage site is accessible in the intermediate structure in which D187N/Y gelsolin spends a longer period of time. Thus, D187N/Y gelsolin is susceptible to aberrant furin cleavage as it passes through the trans Golgi as part of its progression through the secretory pathway (Figure 1 and 3B) (Chen et al., 2001, Nag et al., 2009, Kangas et al., 2002, Huff et al., 2003b). While no disease-associated mutations have been reported at positions Asp 259 or Glu 209, the other calcium-binding side chains, a recombinantly made E209Q G2, like D187N G2, is unable to bind to calcium and is proteolytically cleaved by furin in vitro (Figure 4) and in cell culture experiments (Huff et al., 2003b). Furin cleavage of D187N/Y gelsolin generates a C-terminal 68 kDa fragment (C68) that progresses through the secretory pathway and is secreted into the bloodstream (Figures 1 and 3B). The remainder fragment appears to be rapidly degraded, perhaps in the cell, precluding its release, or outside the cell.

Figure 4.

Cleavage of gelsolin domain 2 by furin in vitro. Wild type gelsolin domain 2, as well as the D187N and E209Q Ca+2-binding-compromised variants of domain 2 were incubated without (−) or with (+) one unit of furin. Cleavage at the 172–173 furin recognition site was observed with D187N and E209Q (an engineered mutant), but not with wild type gelsolin domain 2. Figure reproduced from Huff et al. 2003b.

Upon secretion, the C68 fragment is subsequently cleaved by proteases in the extracellular matrix, and perhaps by other proteases to create the 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments, corresponding to amino acids 173–243 and 173–225, respectively (Figures 1 and 3B). The 8 kDa fragment is the main component of gelsolin amyloid fibrils in human patients, while the 5 kDa fragment appears to be a minor component and is never observed in the absence of the 8 kDa fragment, suggesting the 5 kDa fragment is derived from the 8 Da fragment (Maury, 1991). Membrane type 1 matrix metalloprotease (MT1-MMP), a member of zinc-containing endopeptidases that function to remodel extracellular matrix components, is able to cleave C68 to form the amyloidogenic fragments, and appears to be the protease that performs this cleavage, at least in HT1080 cells (Figure 3B) (Page et al., 2005). Other proteases in the extracellular matrix may also contribute and this merits further investigation.

Interestingly, full length plasma gelsolin is a known substrate for the MMPs, being cleaved by MMP-3 most efficiently, followed by MMP-2, MMP-1, MT1-MMP, and MMP-9 (Park et al., 2006). Three MMP cleavage sites in full length plasma gelsolin were identified, and all were in unstructured regions. Two were in a linker region between G3 and G4 and one was in a region N-terminal to G1 (Park et al., 2006). While none of these cleavage sites match the cleavage sites within C68 that produce the 8 and the 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments, it may be because the C68 cleavage sites are obscured in normally folded G2. Furin cleavage of full length D187N gelsolin cleaves an internal β strand in G2 (Figure 2), almost certainly leading to unfolding of G2. Because G2 is likely largely unfolded, it is particularly susceptible to cleavage by proteases, including the MMPs in the extracellular matrix (Figures 2 and 3B), as proteases recognize largely extended conformations of proteins.

The 8 and 5 kDa Gelsolin Fragments, But Not the C68 Fragment, Form Amyloid in vitro

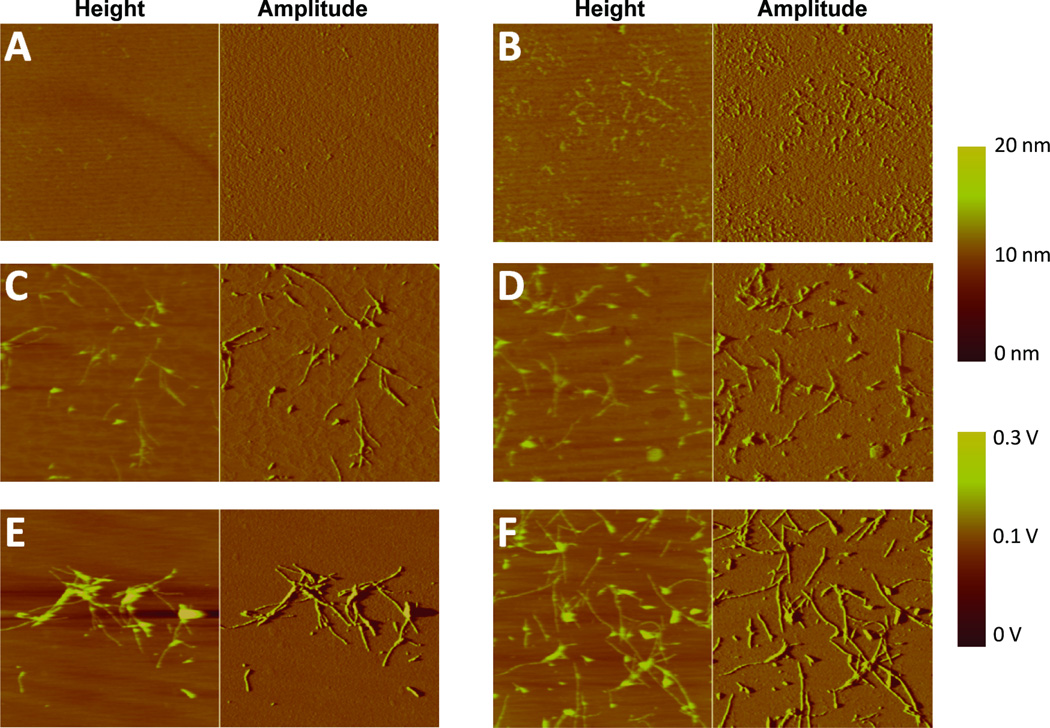

The recombinant 8 kDa fragment of gelsolin is able to form amyloid fibrils in vitro, although agitation is required (Figure 5) (Ratnaswamy et al., 1999, Suk et al., 2006). In addition, smaller fragments of plasma gelsolin containing the D187N/Y mutation were also demonstrated to be amyloidogenic. When a series of short synthetic peptides from 7 to 30 amino acids (containing the D187N or D187Y mutation) was examined for amyloidogenicity by Congo red and thioflavin T fluorescence, it was found that the shortest peptide that was still amyloidogenic was a nine-mer that contained the D187N mutation (Maury et al., 1994). Interestingly, the wild type nine-mer fragment did not form amyloid (Maury et al., 1994). It was determined that the amyloidogenic “core” of the 8 kDa fragment of gelsolin was the part of the fragment that corresponded to 179–194 (Maury et al., 1994).

Figure 5.

Atomic force microscopy images of 8 kDa gelsolin amyloidogenesis reactions. The 8 kDa gelsolin fragment was agitated via overhead rotation in the absence (A, C and E) or presence of heparin (10 µg/mL) (B, D and F), and the amyloidogenesis reaction was followed as a function of time. A and B reflect images recorded early in the amyloidogenesis time course (after 40 min of agitation). C and D reflect images recorded about halfway through the amyloidogenesis time course (after 100 min. for C; after 80 min. for D). E and F represent images at the completion of amyloidogenesis (after 180 min. of agitation). 8 kDa gelsolin fragment amyloidogenesis is accelerated in the presence of heparin. Figure reproduced from Solomon et al. 2011.

When the amyloidogenicity of full length gelsolin was compared to the relevant fragments (C68 and the 8 and 5 kDa fragments), it was demonstrated that the 8 kDa fragment formed amyloid more quickly than the 5 kDa fragment (Solomon et al., 2009), which is likely the reason that the 8 kDa gelsolin fragment is the main component of gelsolin amyloid fibrils in humans (Maury, 1991). The C68 fragment and full length plasma gelsolin did not form amyloid, rationalizing why they have never been observed in human gelsolin amyloid deposits, although C68 might form small soluble oligomers and there is a chance these could contribute to pathology by causing proteotoxicity within the secretory pathway (Solomon et al., 2009).

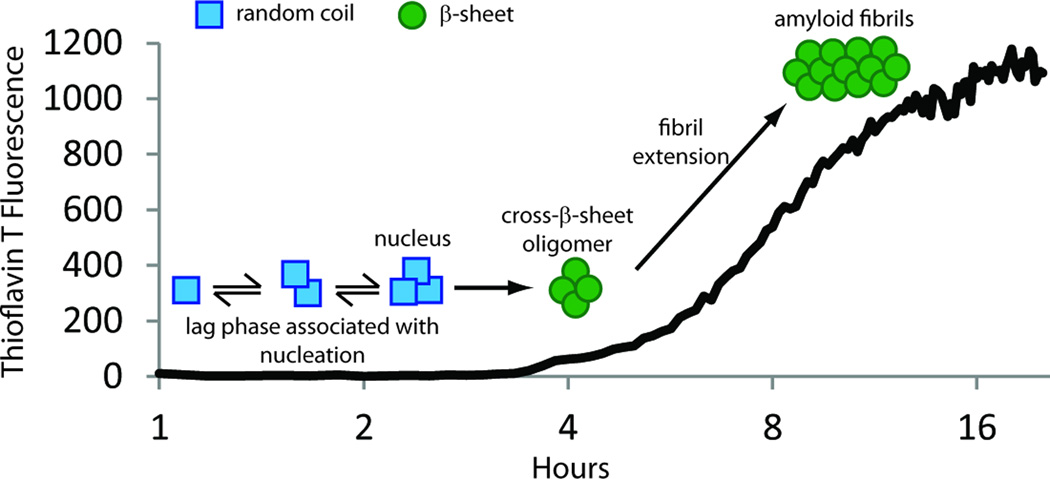

Biophysical experiments demonstrate that the 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments of gelsolin aggregate by a nucleated polymerization reaction (Solomon et al., 2009). This mechanism is characterized by a lag phase, during which a high energy oligomeric nucleus is formed, followed by a spontaneous growth phase, where amyloid fibrils rapidly grow and in a thermodynamically favorable manner (Figure 6) (Serio et al., 2000, Powers and Powers, 2008). The fluorescent dye, thioflavin T, can be used to monitor the nucleated polymerization reaction, as it increases its quantum yield when bound to the cross-β-sheet amyloid fibrils (Figure 6). The presence of fibrils at the conclusion of the reaction can be confirmed by direct visualization, such as by atomic force microscopy (Figure 5). It was demonstrated that increasing concentration of the 8 or 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments increases the rate at which the fibrils are formed. In addition, adding preformed amyloid fibrils to the amyloidogenesis reaction “seeds” the reaction, obviating the requirement for formation of the high energy nucleus, and thus, accelerating amyloidogenesis (Solomon et al., 2009). This mechanism has important implications in vivo because once 8 kDa gelsolin amyloid begins to form it accelerates the rate of 8 and 5 kDa gelsolin amyloidogenesis. Thus, the presence of amyloid seeds begets more 8 and 5 kDa gelsolin to deposit as amyloid, exacerbating disease.

Figure 6.

Gelsolin forms amyloid fibrils by way of a nucleated polymerization mechanism. This mechanism is characterized by a lag phase, during which a high energy oligomeric nucleus is formed, followed by a spontaneous growth phase, where amyloid fibrils grow rapidly, presumably by monomer addition to the nucleus or a growing fibril in a thermodynamically favorable manner. Amyloidogenicity can be monitored by thioflavin T binding-associated fluorescence. Thioflavin T is a dye that increases its fluorescence quantum yield upon binding to amyloid fibrils.

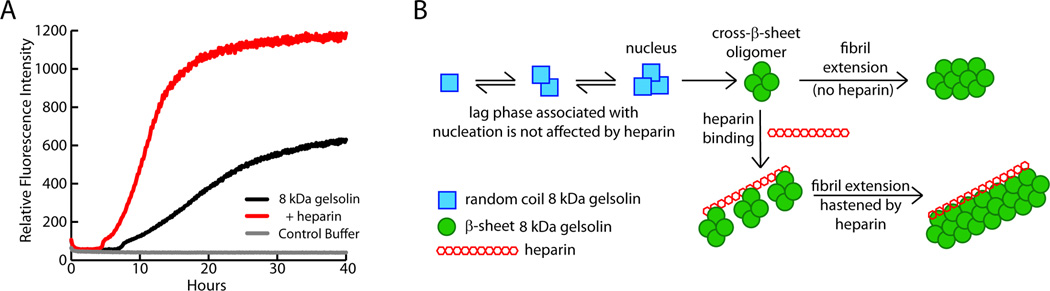

Because the gelsolin fragments are only formed upon C68 secretion from the cell, the extracellular matrix likely plays a key role in the formation of 8 and 5 kDa gelsolin amyloid. Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are linear sulfated polysaccharides prevalent in the extracellular matrix (Gandhi and Mancera, 2008) that have been found to associate with virtually all amyloid deposits in vivo (Snow et al., 1987). As expected, GAGs accelerate the rate at which the 8 kDa fragment of plasma gelsolin forms amyloid (Figure 7A) (Suk et al., 2006). It was recently demonstrated that while GAGs do not affect the secondary structure of the monomerized 8 kDa fragment and do not bind to it, GAGs do bind to cross-β-sheet oligomers through electrostatic interactions and hasten the fibril extension phase of the amyloidogenesis reaction (Figure 7B) (Solomon et al., 2011). Glycosaminoglycans have also been found to hasten the aggregation of other proteins, such as transthyretin, by a similar mechanism (Bourgault et al., 2011).

Figure 7.

Heparin accelerates 8 kDa fragment gelsolin amyloidogenesis by binding and orienting gelsolin fragment cross-β-sheet oligomers. (A) Aggregation of the 8 kDa fragment of gelsolin is faster in the presence of heparin (1 µg/mL) (red trace) than in its absence (black trace). (B) Cross-β-sheet oligomers of gelsolin (assembly of green circles) formed by a nucleated polymerization from monomers (blue squares) accumulate post-nucleation and then bind to heparin (assembly of red hexagons). 8 kDa gelsolin oligomer sequestration by heparin accelerates the fibril extension phase of the amyloidogenesis reaction by binding, concentrating, aligning, and allowing fusion of oligomers into amyloid fibrils. Adapted from Solomon et al. 2011.

In addition to the ability of extracellular matrix components to accelerate gelsolin fragment amyloidogenesis, oxidized small molecules and lipids have also been shown to have an accelerating effect on the amyloidogenesis of a gelsolin fragment, similar to previous studies with the amyloid-β peptide and α-synuclein (Bieschke et al., 2006, Bosco et al., 2006, Bieschke et al., 2005). FAF, like many amyloid diseases, is associated with oxidative stress, and when an oxidized zwitterionic lipid was added to the 179–194 fragment of gelsolin, it accelerated amyloidogenesis (Mahalka et al., 2011). Whether oxidized lipids or small molecules can accelerate the amyloidogenesis of the 8 kDa gelsolin fragment remains to be determined.

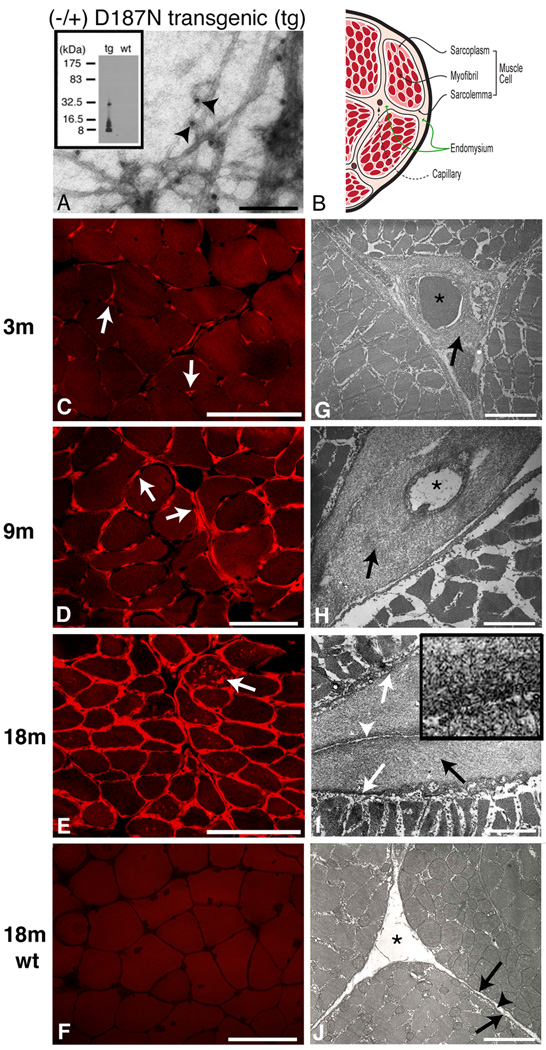

A Faithful Murine Model of FAF

A transgenic human D187N gelsolin murine model of FAF was recently reported featuring gelsolin synthesis in the secretory pathway of the muscle by taking advantage of a muscle-specific promoter to drive D187N gelsolin synthesis and secretion (Page et al., 2009). The mouse model exhibits the aging-associated extracellular amyloid deposition of human FAF (Figure 8) (Page et al., 2009). Interestingly, amyloidogenesis is observed only in tissues synthesizing human D187N gelsolin, despite the presence of the 68 kDa cleavage product circulating in the blood, suggesting that local synthesis is required for amyloid fragment formation and/or deposition (Page et al., 2009). The mouse model of D187N FAF faithfully recapitulates G2 misfolding in the Golgi and the aberrant endoproteolytic cascade (Figure 3B). Initial cleavage by furin in the Golgi produces the C68 fragment that is secreted. Subsequent proteolytic step(s) afford the 8 and 5 kDa fragments observed in the human disease. Thus, the FAF mouse model is exceptional for testing therapies that prevent G2 misfolding or the subsequent endoproteolytic cleavage events. FAF patients may have late-onset muscle weakness, while skin problems are common even earlier, and both of these symptoms are observed in the FAF mice. However, the mice also seem to develop a form of inclusion body myositis featuring intracellular gelsolin fragment deposition, and it is not yet clear whether human FAF patients exhibit this phenotype. Inclusion body myositis, the most common sporadic muscle disease in people over the age of 50, is characterized by intracellular deposition of numerous proteins in muscle fibers (Engel and Askanas, 2006).

Figure 8.

8- and, to a lesser extent, 5-kDa gelsolin amyloid deposition in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyloidosis of Finnish type (FAF). (A) Electron microscopy of amyloid isolated from 18-month old D187N gelsolin mouse. Fibrils are labeled with anti-FAF antibodies attached to 10 nm gold particles (indicated by arrowheads). (B) Schematic of a cross section of a muscle fiber with the same orientation as C–J. (C–J) Cross sections of muscle fibers were analyzed in D187N mice at 3 months (C,G), at 9 months (D,H) and at 18 months (E,I), and in 18-month wild-type controls (F,J). In 3-month mice, Congo red fluorescent deposits were localized exclusively around endomysial capillaries (C, arrows). By 9 months, Congo red fluorescence was present around endomysial capillaries but also extended into the endomysium surrounding muscle fibers (D, arrows). At 18 months, Congo red fluoresecence surrounded all myofibers with several fibers also showing internal sarcoplasmic deposits (E, arrow). By comparison, no Congo red positivity (F) was identified in 18-month wild-type mice. Electron micrographs confirmed fibrillar deposits in a pericapillary localization in 3-month D187N mice (G, arrow). At 9 months, more extensive fibrillar deposits surrounded capillaries (H, arrows) and also extended into the endomysium. Thick pericapillary and endomysial fibrillar deposits (I, black arrow) were found in 18-month D187N muscle. The large fibrillar deposits were between the sarcolemma (I, white arrows) of adjacent cells and the connective tissue of normal endomysium (I, white arrowhead) and were absent in wild-type siblings (J, sarcolemma (arrows); endomysium (arrowhead)). Capillaries indicated with *. The high magnification inset (I) shows the fibrillar nature of the deposits. Bar = 40 100nm for A, 100 µm for C–F, 3.3 µm for G, 2.2 µm for H, 2.0 µm for I, 0.3 µm for (I insert), 2.0 µm for J. Figure reproduced from Page et al. 2009.

Development of Therapeutic Strategies against Gelsolin Amyloidosis Based on our Knowledge of the Biochemistry and Pathology of this Malady

FAF appears to be caused by a gain-of-toxic function associated with gelsolin fragment amyloidogenesis (Page et al., 2009). There are no reports of a sporadic or wild-type form of gelsolin amyloidosis; hence the mutation appears to be critical. Because the 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments aggregate by a nucleated polymerization and their amyloidogenesis is accelerated by oxidized lipids as well as components of the extracellular matrix, it is likely that preventing their formation and reducing their concentration, rather than attempting to inhibit their amyloidogenesis, would represent the most promising therapeutic strategy.

While inhibiting the mutant gelsolin FAF proteolytic cascade remains a viable option for preventing the formation of the 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments, it does have its associated challenges. The first cleavage of mutant full-length plasma gelsolin leading to the C68 fragment is performed by furin (Chen et al., 2001, Huff et al., 2003a, Huff et al., 2003b, Kangas et al., 2002). Furin is a very important cellular protease that is required to cleave many proproteins into their mature forms within the cellular secretory pathway (Zhou et al., 1999). Thus, furin’s inhibition could have downstream toxic effects, analogous to those reported for γ-secretase inhibition as an approach to lower Aβ concentration to reduce aggregation propensity (Arumugam et al., 2011, Imbimbo and Giardina, 2011, Sambamurti et al., 2011, Schor, 2010). In addition, there are very few small molecule furin inhibitors available (Jiao et al., 2006). However, even with these difficulties, owing to the fact that approximately 70% of D187N full length gelsolin is not cleaved (Figure 3B), a modest reduction in cellular furin activity could reduce the concentration of C68 enough to significantly reduce amyloid deposition and delay onset of the disease, while not causing too many side effects.

It has been demonstrated that the second cleavage of the C68 fragment to form the 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments can be performed by MT1-MMP in cultured cells (Page et al., 2005). Because G2 in C68 is likely largely or completely unfolded, other MMPs and other classes of proteases could also cleave C68 into amyloidogenic fragments even if MT1-MMP is completely inhibited. Owing to the refractory nature of inhibiting MMPs for clinical benefit, inhibiting the second cleavage is not appealing to us because several proteases may need to be inhibited to block gelsolin amyloidogenesis by this route.

Instead of inhibiting furin or subsequent proteolytic steps, it may be possible to thermodynamically and/or kinetically stabilize the second domain of D187N/Y plasma gelsolin in the cellular secretory pathway employing a pharmacologic chaperone or a more specialized kinetic stabilizer (Baures et al., 1999, Baures et al., 1998, Johnson et al., 2005, Yu et al., 2007, Oza et al., 2002, Petrassi et al., 2000, Miller et al., 2004, Green et al., 2003, Kolstoe et al., 2010). Such a small molecule is envisioned to bind to plasma gelsolin in the cellular secretory pathway allowing pharmacologic chaperone binding-induced stabilization of mutant G2, partially making up for the loss of calcium binding, thus preventing aberrant furin endoproteolysis by keeping G2 folded. A similar strategy was recently used to kinetically stabilize the tetrameric protein transthyretin. Tafamidis, resulting from the transthyretin kinetic stabilizer program, is the first drug that halts the progression of a human amyloid disease(Coelho et al., 2011). As such, the European Medicines Agency recently approved Tafamidis for ameliorating all classes of familial amyloid polyneuropathy caused by amyloidogenic variants of transthyretin.

Finally, it may be possible to adapt the biology of proteome maintenance or proteostasis using small molecule proteostasis regulators to ameliorate FAF (Cohen et al., 2009, Wiseman et al., 2007, Balch et al., 2008, Hartl et al., 2011). The protein homeostasis or proteostasis network refers to the interacting and competing cellular pathways that regulate and affect protein synthesis, including folding, trafficking, and degradation (Balch et al., 2008, Hartl et al., 2011). Specific manipulation of the stress responsive signaling pathways that match proteostasis network capacity with demand (such as the unfolded protein response regulating secretory proteostasis or the heat shock response which regulates cytosolic proteostasis) employing small molecules or biologicals may increase the profolding capacity of the cell, enabling the second domain of gelsolin to remain folded through chaperone and trafficking receptor interactions to resist furin endoproteolysis (Balch et al., 2008). It was previously demonstrated that increasing ER calcium levels by inhibiting calcium efflux or promoting calcium influx enhanced the capacity of the cell to correctly fold and traffic mutant forms of glucocerebrosidase (Ong et al., 2010). Increasing calcium levels may also increase the cells’ capacity to correctly fold and traffic D187N gelsolin and protect it from furin cleavage, as both D187N/Y gelsolin and furin activity are regulated by ER calcium levels (Chen et al., 2001, Huff et al., 2003b, Page et al., 2004).

Summary and Conclusion

Familial amyloidosis of Finnish type is a monogenic autosomal dominant systemic amyloid disease characterized by corneal lattice dystrophy, neurodegeneration, and cutis laxa. It is caused by a D187N/Y point mutation in secreted gelsolin that eliminates a calcium binding site in the second domain of plasma gelsolin. Without the stability of calcium binding, the second domain can sample unfolded conformations rendering it susceptible to aberrant furin cleavage as it trafficks through the trans Golgi. The C-terminal 68 kDa fragment produced by furin cleavage is secreted, where it is cleaved by proteases such as membrane type 1 matrix metalloprotease in the extracellular matrix to form the 8 and 5 kDa amyloidogenic fragments that deposit systemically. Unfortunately there is currently no cure for FAF, nor is there a treatment that alters the underlying etiology of the disease. However, there is a mouse model that should be excellent for testing a subset of the therapeutic strategies outlined above to ameliorate gelsolin amyloidosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Colleen Fearns for help with manuscript preparation and many helpful discussions, as well as Dr. Jonathan Zhu, for help with figure production.

The authors thank the NIH (AG018917 to JWK and WEB), the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, and the Lita Annenberg Hazen Foundation for financial support.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Ardalan MR, Shoja MM, Kiuru-Enari S. Amyloidosis-related nephrotic syndrome due to a G654A gelsolin mutation: the first report from the Middle East. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:272–275. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Cheng Y-L, Choi Y, Choi Y-H, Yang S, Yun Y-K, Park J-S, Yang DK, Thundyil J, Gelderblom M, Karamyan VT, Tang S-C, Chan SL, Magnus T, Sobey CG, Jo D-G. Evidence that γ-secretase-mediated Notch signaling induces neuronal cell death via the nuclear factor-κB-Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death pathway in ischemic stroke. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:23–31. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashish, Paine MS, Perryman PB, Yang L, Yin HL, Krueger JK. Global structure changes associated with Ca2+ activation of full-length human plasma gelsolin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25884–25892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baures PW, Oza VB, Peterson SA, Kelly JW. Synthesis and evaluation of inhibitors of transthyretin amyloid formation based on the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug flufenamic acid. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baures PW, Peterson SA, Kelly JW. Discovering transthyretin amyloid fibril inhibitors by limited screening. Bioorg Med Chem. 1998;6:1389–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke J, Zhang Q, Bosco DA, Lerner RA, Powers ET, Wentworth P, Jr, Kelly JW. Small Molecule Oxidation Products Trigger Disease-Associated Protein Misfolding. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:611–619. doi: 10.1021/ar0500766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke J, Zhang Q, Powers ET, Lerner RA, Kelly JW. Oxidative metabolites accelerate Alzheimer's amyloidogenesis by a two-step mechanism, eliminating the requirement for nucleation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4977–4983. doi: 10.1021/bi0501030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CCF, Serpell LC, Sunde M, Sandgren O, Lundgren E. A molecular model of the amyloid fibril. Ciba Found Symp. 1996;199:6–12. doi: 10.1002/9780470514924.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth DR, Sunde M, Bellotti V, Robinson CV, Hutchinson WL, Fraser PE, Hawkins PN, Dobson CM, Radford SE, Blake CCF, Pepys MB. Instability, unfolding and aggregation of human lysosozyme variants underlying amyloid fibrillogenesis. Nature. 1997;385:787–793. doi: 10.1038/385787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco DA, Fowler DM, Zhang Q, Nieva J, Powers ET, Wentworth P, Lerner RA, Kelly JW. Elevated levels of oxidized cholesterol metabolites in Lewy body disease brains accelerate alpha-synuclein fibrilization. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nchembio782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgault S, Solomon JP, Reixach N, Kelly JW. Sulfated glycosaminoglycans accelerate transthyretin amyloidogenesis by quaternary structural conversion. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1001–1015. doi: 10.1021/bi101822y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciantini M, Giannoni E, Chiti F, Baroni F, Formigli L, Zurdo J, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM, Stefani M. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 2002;416:507–511. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucki R, Byfield FJ, Kulakowska A, Mccormick ME, Drozdowski W, Namiot Z, Hartung T, Janmey PA. Extracellular gelsolin binds lipoteichoic acid and modulates cellular response to proinflammatory bacterial wall components. J Immunol. 2008a;181:4936–4944. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucki R, Kulakowska A, Byfield FJ, Zendzian-Piotrowska M, Baranowski M, Marzec M, Winer JP, Ciccarelli NJ, Gorski J, Drozdowski W, Bittman R, Janmey PA. Plasma gelsolin modulates cellular response to sphingosine 1-phosphate. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C1516–C1523. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00051.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucki R, Levental I, Kulakowska A, Janmey PA. Plasma Gelsolin: Function, Prognostic Value, and Potential Therapeutic Use. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2008b;9:541–551. doi: 10.2174/138920308786733912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtnick LD, Koepf EK, Grimes J, Jones EY, Stuart DI, Mclaughlin PJ, Robinson RC. The crystal structure of plasma gelsolin: Implications for actin severing, capping, and nucleation. Cell. 1997;90:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrwik C, Stenevi U. Lattice corneal dystrophy, gelsolin type (Meretoja's syndrome) Acta Ophthalmologica. 2009;87:813–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier-Harlin M-C, Kachergus J, Roumier C, Mouroux V, Douay X, Lincoln S, Levecque C, Larvor L, Andrieux J, Hulihan M, Waucquier N, Defebvre L, Amouyel P, Farrer M, Destee A. α-synuclein locus duplication as a cause of familial Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2004;364:1167–1169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastan N, Baert-Desurmont S, Saugier-Veber P, Derumeaux G, Cabot A, Frebourg T, Hannequin D. Cardiac conduction alterations in a french family with amyloidosis of the Finnish type with the p.Asp187Tyr mutation in the GSN gene. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:113–119. doi: 10.1002/mus.20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan V, Ji L, Chauhan A. Anti-amyloidogenic, anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic role of gelsolin in Alzheimer's disease. Biogerontology. 2008;9:381–389. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9169-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan VPS, Ray I, Chauhan A, Wisniewski HM. Binding of gelsolin, a secretory protein, to amyloid beta-protein. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1999;258:241–246. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CD, Huff ME, Matteson J, Page LJ, Phillips R, Kelly JW, Balch WE. Furin initiates gelsolin familial amyloidosis in the Golgi through a defect in Ca2+ stabilization. EMBO J. 2001;20:6277–6287. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti F, Stefani M, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM. Rationalization of the effects of mutations on peptide and protein aggregation rates. Nature. 2003;424:805–808. doi: 10.1038/nature01891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H, Burtnick LD, Mejillano M, Yin HL, Robinson RC, Choe S. The calcium activation of gelsolin: Insights from the 3 angstrom structure of the G4–G6/actin complex. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:691–702. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo DW, Schneider JP, Graciani NR, Kelly JW. Nucleated antiparallel Œ≤-sheet that folds and undergoes self-assembly: a template promoted folding strategy toward controlled molecular architectures. Macromolecules. 1996;29:355–366. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho T, Maia L, Da Silva AM, Cruz MW, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Lozeron P, Suhr OB, Campistol J, Conceicao I, Schmidt H, Trigo P, Packman J, Grogan DR. A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Disease-Modifying Effects of Tafamidis in Patients with Transthyretin Type Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy. Neurology. 2011;76:A111–A111. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Paulsson JF, Blinder P, Burstyn-Cohen T, Du D, Estepa G, Adame A, Pham HM, Holzenberger M, Kelly JW, Masliah E, Dillin A. Reduced IGF-1 signaling delays age-associated proteotoxicity in mice. Cell. 2009;139:1157–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen FE, Kelly JW. Therapeutic approaches to protein-misfolding diseases. Nature. 2003;426:905–909. doi: 10.1038/nature02265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceicao I, Sales-Luis ML, De Carvalho M, Evangelista T, Fernandes R, Paunio T, Kangas H, Coutinho P, Neves C, Saraiva MJ. Gelsolin-related familial amyloidosis, Finnish type, in a Portuguese family: Clinical and neurophysiological studies. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:715–721. doi: 10.1002/mus.10474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contegal F, Bidot S, Thauvin C, Leveque L, Soichot P, Gras P, Moreau T, Giroud M. Finnish amyloid polyneuropathy in a French patient. Revue Neurologique. 2006;162:997–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(06)75110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Chapelle A, Tolvanen R, Boysen G, Santavy J, Bleekerwagemakers L, Maury CPJ, Kere J. Gelsolin-derived familial amyloidosis caused by asparagine or tyrosine substitution for aspartic acid at residue 187. Nat Genet. 1992;2:157–160. doi: 10.1038/ng1092-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson CM. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel WK, Askanas V. Inclusion-body myositis: Clinical, diagnostic, and pathologic aspects. Neurology. 2006;66:S20–S29. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192260.33106.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzone TL, Gunawardena S, Mccleary D, Reis GF, Goldstein LSB. Kinesin-1 transport reductions enhance human tau hyperphosphorylation, aggregation and neurodegeneration in animal models of tauopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4399–4408. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandrich M, Fletcher MA, Dobson CM. Amyloid fibrils from muscle myoglobin - Even an ordinary globular protein can assume a rogue guise if conditions are right. Nature. 2001;410:165–166. doi: 10.1038/35065514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix EPV, Jung LS, Carvalho GS, Oliveira ASB. Corneal lattic dystrophy type II: Familial amyloid neuropathy type IV (gelsolin amyloidosis) einstein. 2008;6:505–506. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Escamilla A-M, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Serrano L. Prediction of sequence-dependent and mutational effects on the aggregation of peptides and proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1302–1306. doi: 10.1038/nbt1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrone F. Amyloid, Prions, and Other Protein Aggregates. San Diego: Academic Press Inc; 1999. Analysis of protein aggregation kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi NS, Mancera RL. The structure of glycosaminoglycans and their interactions with proteins. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;72:455–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green NS, Palaninathan SK, Sacchettini JC, Kelly JW. Synthesis and Characterization of Potent Bivalent Amyloidosis Inhibitors That Bind Prior to Transthyretin Tetramerization. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13404–13414. doi: 10.1021/ja030294z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guentert A, Campbell J, Saleem M, O'brien DP, Thompson AJ, Byers HL, Ward MA, Lovestone S. Plasma Gelsolin is Decreased and Correlates with Rate of Decline in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2010;21:585–596. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltia M, Prelli F, Ghiso J, Kiuru S, Somer H, Palo J, Frangione B. Amyloid Protein In Familial Amyloidosis (Finnish Type) Is Homologous to Gelsolin, and Actin-binding Protein. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1990;167:927–932. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90612-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstroem P, Sekijima Y, White JT, Wiseman RL, Lim A, Costello CE, Altland K, Garzuly F, Budka H, Kelly JW. D18G Transthyretin Is Monomeric, Aggregation Prone, and Not Detectable in Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid: A Prescription for Central Nervous System Amyloidosis? Biochemistry. 2003;42:6656–6663. doi: 10.1021/bi027319b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstrom P, Jiang X, Hurshman AR, Powers ET, Kelly JW. Sequence-dependent denaturation energetics: A major determinant in amyloid disease diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(Suppl 4):16427–16432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202495199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstrom P, Schneider F, Kelly JW. Trans-suppression of misfolding in an amyloid disease. Science. 2001;293:2459–2462. doi: 10.1126/science.1062245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstrom P, Wiseman RL, Powers ET, Kelly JW. Prevention of transthyretin amyloid disease by changing protein misfolding energetics. Science. 2003;299:713–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1079589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Her L-S, Goldstein LSB. Enhanced sensitivity of striatal neurons to axonal transport defects induced by mutant huntingtin. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13662–13672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4144-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirko AC, Meyer EM, King MA, Hughes JA. Peripheral transgene expression of plasma gelsolin reduces amyloid in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1623–1629. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerva V, Velasc A, Sanchez MC, Mateo AJ, Matias-Guiu X. Lattice corneal dystrophy type II: Clinical, pathologic, and molecular study in a Spanish family. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17:424–429. doi: 10.1177/112067210701700326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff ME, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Pathological and functional amyloid formation orchestrated by the secretory pathway. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003a;13:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff ME, Page LJ, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Gelsolin domain 2 Ca2+ affinity determines susceptibility to furin proteolysis and familial amyloidosis of Finnish type. J Mol Biol. 2003b;334:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurshman Babbes AR, Powers ET, Kelly JW. Quantification of the Thermodynamically Linked Quaternary and Tertiary Structural Stabilities of Transthyretin and Its Disease-Associated Variants: The Relationship between Stability and Amyloidosis. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6969–6984. doi: 10.1021/bi800636q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez P, Bonnet AM, Debarges B, Lohmann E, Tison F, Pollak P, Agid Y, Durr A, Brice A. Causal relation between α-synuclein gene duplication and familial Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2004;364:1169–1171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Mizushima K, Fujita Y, Watanabe M, Sasaki A, Makioka K, Enoki M, Nakamura M, Otani T, Takatama M, Okamoto K. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy (Finnish type) in a Japanese family: Clinical features and immunocytochemical studies. J Neurol Sci. 2007;252:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbimbo BP, Giardina GaM. γ-Secretase inhibitors and modulators for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: disappointments and hopes. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:1555–1570. doi: 10.2174/156802611795860942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L, Chauhan A, Chauhan V. Cytoplasmic gelsolin in pheochromocytoma-12 cells forms a complex with amyloid beta-protein. Neuroreport. 2008;19:463–466. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f5f79a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Buxbaum JN, Kelly JW. The V122I cardiomyopathy variant of transthyretin increases the velocity of rate-limiting tetramer dissociation, resulting in accelerated amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14943–14948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261419998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao GS, Cregar L, Wang JZ, Millis SZ, Tang C, O'malley S, Johnson AT, Sareth S, Larson J, Thomas G. Synthetic small molecule furin inhibitors derived from 2,5-dideoxystreptamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19707–19712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606555104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Wiseman RL, Sekijima Y, Green NS, Adamski-Werner SL, Kelly JW. Native State Kinetic Stabilization As a Strategy To Ameliorate Protein Misfolding Diseases: A focus on the Transthyretin Amyloidoses. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:911–921. doi: 10.1021/ar020073i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangas H, Paunio T, Kalkkinen N, Jalanko A, Peltonen L. In vitro expression analysis shows that the secretory form of gelsolin is the sole source of amyloid in gelsolin-related amyloidosis. Human Molecular Genetics. 1996;5:1237–1243. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.9.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangas H, Seidan NG, Paunio D. Role of proprotein convertases in the pathogenic processing of the amyloidosis-associated form of secretory gelsolin. Amyloid. 2002;9:83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmirski SL, Isaacson RL, An C, Buckle A, Johnson CM, Daggett V, Fersht AR. Loss of a metal-binding site in gelsolin leads to familial amyloidosis-Finnish type. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nsb745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JW. Alternative conformations of amyloidogenic proteins govern their behavior. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JW. The alternative conformations of amyloidogenic proteins and their multi-step assembly pathways. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:101–106. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaitlina S, Hinssen H. Ca-dependent binding of actin to gelsolin. FEBS Letters. 2002;521:14–18. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02657-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuru-Enari S, Keski-Oja J, Haltia M. Cutis laxa in hereditary gelsolin amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:250–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuru-Enari S, Somer H, Seppalainen AM, Notkola IL, Haltia M. Neuromuscular pathology in hereditary gelsolin amyloidosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:565–571. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuru S. Gelsolin-related familial amyloidosis, Finnish type (FAF), and its variants found worldwide. Amyloid. 1998;5:55–66. doi: 10.3109/13506129809007291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuru S, Matikainen E, Kupari M, Haltia M, Palo J. Autonomic nervous system and cardiac involvement in familial amyloidosis, Finnish type (FAF) J Neurol Sci. 1994;126:40–48. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivela T, Tarkkanen A, Frangione B, Ghiso J, Haltia M. Ocular amyloid deposition in familial amyloidosis, Finnish: An analysis of native and variant gelsolin in Meretojas syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1994;35:3759–3769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolstoe SE, Mangione PP, Bellotti V, Taylor GW, Tennent GA, Deroo S, Morrison AJ, Cobb AJA, Coyne A, Mccammon MG, Warner TD, Mitchell J, Gill R, Smith MD, Ley SV, Robinson CV, Wood SP, Pepys MB. Trapping of palindromic ligands within native transthyretin prevents amyloid formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20483–20488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008255107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Mehl R, Izumo S, Nadalginard B, Yin HL. Muscle is the major source of plasma gelsolin. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8239–8243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Stossel TP, Orkin SH, Mole JE, Colten HR, Yin HL. Plasma and cytoplasmic gelsolins are encoded by a single gene and contain a duplicated actin-binding domain. Nature. 1986;323:455–458. doi: 10.1038/323455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel HA, Hartley D, Petre BM, Walz T, Lansbury PT. Neurodegenerative disease: Amyloid pores from pathogenic mutations. Nature. 2002;418:291. doi: 10.1038/418291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Culyba EK, Powers ET, Kelly JW. Amyloid-beta forms fibrils by nucleated conformational conversion of oligomers. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:602–609. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PS, Waxman AB, Cotich KL, Chung SW, Perrella MA, Stossel TP. Plasma gelsolin is a marker and therapeutic agent in animal sepsis. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35:849–855. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253815.26311.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepina I, Czaplewski C, Janmey P, Liwo A. Molecular dynamics study of a gelsolin-derived peptide binding to a lipid bilayer containing phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Biopolymers. 2003;71:49–70. doi: 10.1002/bip.10375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin A, Teplow DB, Kirschner DA, Benedek GB. Kinetic theory of fibrillogenesis of amyloid-beta protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7942–7947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueck A, Yin HL, Kwiatkowski DJ, Allen PG. Calcium regulation of gelsolin and adseverin: A natural test of the helix latch hypothesis. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5274–5279. doi: 10.1021/bi992871v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luettmann RJ, Teismann I, Husstedt IW, Ringelstein EB, Kuhlenbaeumer G. Hereditary amyloidosis of the Finnish type in a German family: Clinical and electrophysiological presentation. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:679–684. doi: 10.1002/mus.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhrs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Dobeli H, Schubert D, Riek R. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta (1–42) fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalka AK, Maury CPJ, Kinnunen PKJ. 1-Palmitoyl-2-(9 '-oxononanoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholline, an Oxidized Phospholipid, Accelerates Finnish Type Familial Gelsolin Amyloidosis in Vitro. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4877–4889. doi: 10.1021/bi200195s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makioka K, Ikeda M, Ikeda Y, Nakasone A, Osawa T, Sasaki A, Otani T, Arai M, Okamoto K. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy (Finnish type) presenting multiple cranial nerve deficits with carpal tunnel syndrome and orthostatic hypotension. Neurol Res. 2010;32:472–475. doi: 10.1179/174313209X409007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maury CPJ. Gelsolin-related amyloidosis: Identification of the amyloid protein in Finnish hereditary amyloidosis as a fragment of variant gelsolin. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1195–1199. doi: 10.1172/JCI115118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maury CPJ. Homozygous familial amyloidosis, Finnish type: Demonstration of glomerular gelsolin-derived amyloid and nonamyloid tubular gelsolin. Clin Nephrol. 1993;40:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maury CPJ, Nurmiaholassila EL, Rossi H. Amyloid fibril formation in gelsolin-derived amyloidosis: Definition of the amyloidogenic region and evidence of accelerated amyloid formation of mutant Asn-187 and Tyr-187 gelsolin peptides. Lab Invest. 1994;70:558–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meretoja J. Familial systemic paramyloidosis with lattice dystrophy of the cornea, progressive cranial neuropathy, skin changes and various internal symptoms. A previously unrecognized heritable syndrome. Ann Clin Res. 1969;1:314–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meretoja J. Genetic aspects of familial amyloidosis with corneal lattice dystrophy and cranial neuropathy. Clin Genet. 1973;4:173–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1973.tb01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SR, Sekijima Y, Kelly JW. Native state stabilization by NSAIDs inhibits transthyretin amyloidogenesis from the most common familial disease variants. Lab Invest. 2004;84:545–552. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag S, Ma Q, Wang H, Chumnarnsilpa S, Lee WL, Larsson M, Kannan B, Hernandez-Valladarez M, Burtnick LD, Robinson RC. Ca2+ binding by domain 2 plays a critical role in the activation and stabilization of gelsolin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13713–13718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812374106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Sawaya MR, Balbirnie M, Madsen AO, Riekel C, Grothe R, Eisenberg D. Structure of the cross-beta spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature. 2005;435:773–778. doi: 10.1038/nature03680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olzscha H, Schermann SM, Woerner AC, Pinkert S, Hecht MH, Tartaglia GG, Vendruscolo M, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU, Vabulas RM. Amyloid-like aggregates sequester numerous metastable proteins with essential cellular functions. Cell. 2011;144:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong DST, Mu TW, Palmer AE, Kelly JW. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ increases enhance mutant glucocerebrosidase proteostasis. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:424–432. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oza VB, Smith C, Raman P, Koepf EK, Lashuel HA, Petrassi HM, Chiang KP, Powers ET, Sachettinni J, Kelly JW. Synthesis, structure, and activity of diclofenac analogues as transthyretin amyloid fibril formation inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2002;45:321–332. doi: 10.1021/jm010257n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]