Abstract

Organ replacement regenerative therapy is purported to enable the replacement of organs damaged by disease, injury or aging in the foreseeable future. Here we demonstrate fully functional hair organ regeneration via the intracutaneous transplantation of a bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicle germ. The pelage and vibrissae are reconstituted with embryonic skin-derived cells and adult vibrissa stem cell region-derived cells, respectively. The bioengineered hair follicle develops the correct structures and forms proper connections with surrounding host tissues such as the epidermis, arrector pili muscle and nerve fibres. The bioengineered follicles also show restored hair cycles and piloerection through the rearrangement of follicular stem cells and their niches. This study thus reveals the potential applications of adult tissue-derived follicular stem cells as a bioengineered organ replacement therapy.

Bioengineered hair follicles can be produced from embryonic follicle germ cells, but whether these follicles can interact with the surrounding tissue and function normally is unknown. Here, bioengineered hair follicles transplanted into mouse dermis make connections with the surrounding tissue and show normal hair cycles.

Bioengineered hair follicles can be produced from embryonic follicle germ cells, but whether these follicles can interact with the surrounding tissue and function normally is unknown. Here, bioengineered hair follicles transplanted into mouse dermis make connections with the surrounding tissue and show normal hair cycles.

Organ replacement regenerative therapy is expected to provide novel therapeutic systems for donor organ transplantation, which is an approach to treating patients who experience organ dysfunction as the result of disease, injury or aging1. Concepts in current regenerative therapy include stem cell transplantation and two-dimensional uniform cell sheet technologies, both of which have the potential to restore partially lost tissue or organ function2,3,4. The development of bioengineered ectodermal organs, such as teeth, salivary glands, or hair follicles may be achieved by reproducing the developmental processes that occur during organogenesis5,6,7,8,9. Ectodermal organs have essential physiological roles and can greatly influence the quality of life by preventing the morbidity associated with afflictions such as caries and hypodontia in teeth10, hyposalivation in the salivary gland11, and androgenetic alopecia, which affects the hair12. Recently, it has been proposed that a bioengineered tooth can restore oral and physiological function through the transplantation of bioengineered tooth germ and a bioengineered mature tooth unit, which would represent a successful organ-replacement regenerative therapy13.

The hair coat has important roles in thermoregulation, physical insulation, sensitivity to noxious stimuli, and social communication14. In the developing embryo, hair follicle morphogenesis is regulated by reciprocal epithelial and mesenchymal interactions that occur in almost all organs9,15,16. The hair follicle is divided into a permanent upper region, which consists of the infundibulum and isthmus, and a variable lower region, which is the actual hair-shaft factory that contains the hair matrix, differentiated epithelial cells and dermal papilla (DP) cells15,16,17. DP cells are responsible for the production of dermal-cell populations such as dermal sheath (DS) cells18, and they generate dermal fibroblasts and adipocytes19,20. After morphogenesis, various stem cell types are maintained in certain regions of the follicle. For instance, follicle epithelial cells are found in the follicle stem cell niche of the bulge region21,22; multipotent mesenchymal precursors are found in DP cells18,19; neural crest-derived melanocyte progenitors are located in the sub-bulge region23,24,25, and follicle epithelial stem cells in the bulge region that is connected to the arrector pili muscle15,26. The follicle variable region mediates the hair cycle, which depends on the activation of follicle epithelial stem cells in the bulge stem cell niche during the telogen-to-anagen transition27,28. This transition includes phases of growth (anagen), apoptosis-driven regression (catagen)29 and relative quiescence (telogen)17, whereas the organogenesis of most organs is induced only once during embryogenesis16.

To achieve hair follicle regeneration in the hair cycle, it is thought to be essential to regenerate the various stem cells and their niches9,30. Many studies have attempted to develop technologies to renew the variable lower region of the hair follicle31,32, to achieve de novo folliculogenesis via replacement with hair follicle-inductive dermal cells33, and to direct the self-assembly of skin-derived epithelial and mesenchymal cells34,35,36,37,38,39. We have also reported that a bioengineered hair follicle germ, reconstituted from embryonic follicle germ-derived epithelial and mesenchymal cells, using our organ germ method, can generate a bioengineered hair follicle and shaft7. However, it remains to be determined whether the bioengineered hair follicle germ can generate a bioengineered hair follicle and shaft by intracutaneous transplantation to provide fully functional hair regeneration, including hair shaft elongation, hair cycles, connections with surrounding tissues, and the regeneration of stem cells and their niches9,30.

Here we demonstrate fully functional orthotopic hair regeneration via the intracutaneous transplantation of bioengineered hair follicle germ. The bioengineered hair has the correct structures of the naturally occurring hair follicle and shaft, and it forms proper connections with surrounding host tissues, such as the epidermis, arrector pili muscle and nerve fibres. The bioengineered hair follicles show full functionality, including the ability to undergo repeated hair cycles through the rearrangement of various stem cell niches, as well as responsiveness to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh). Our current study thus demonstrates the potential for not only hair regeneration therapy but also the realization of bioengineered organ replacement using adult somatic stem cells.

Results

Hair follicle regeneration from a bioengineered follicle germ

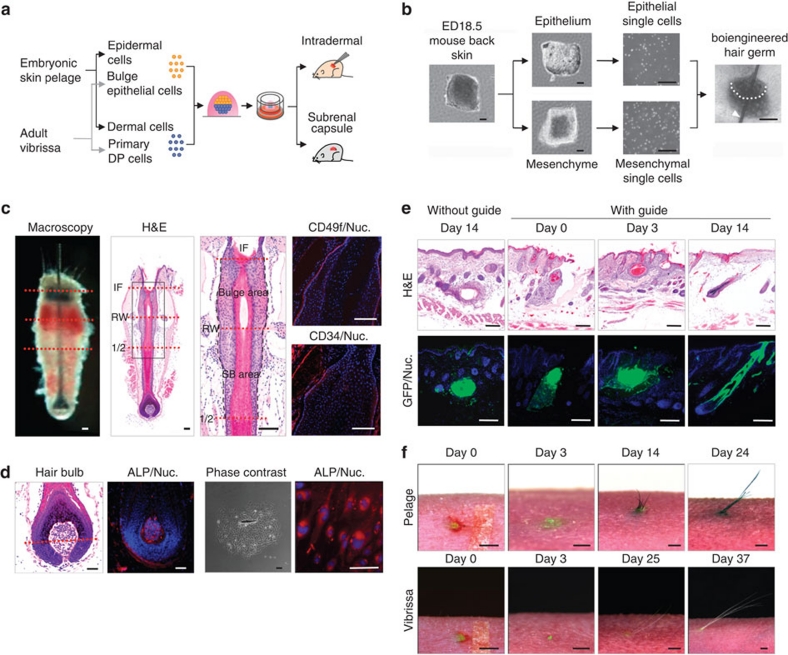

We first investigated whether bioengineered hair follicle germs, reconstituted by our previously developed organ germ method, could orthotopically erupt from a hair shaft with the proper tissue structure and skin connections in the cutaneous environment of an adult mouse (Fig. 1a). To regenerate a bioengineered pelage follicle germ, the bioengineered pelage follicle germ was reconstituted with E18 mouse embryonic back skin-derived epithelial and mesenchymal cells (Fig. 1b). The bioengineered vibrissa follicle germ was regenerated using dissociated epithelial cells (1×104 cells) isolated from the adult vibrissa-derived bulge region, which expressed CD49f and CD34 antigens (Fig. 1c), and primary cultured DP cells (3×103 cells; Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. Methods for hair follicle regeneration.

(a) Schematic representation of the methods used for the generation and transplantation of a bioengineered hair follicle germ. (b) Phase-contrast images of murine embryonic back skin, tissues, dissociated single cells and bioengineered hair follicle germ, which was reconstituted using the organ germ method, with a nylon thread guide (arrow head). Scale bars, 200 μm. (c) Histological analyses of a natural vibrissa isolated from an adult mouse. Macroscopic and H & E staining of whole vibrissa is shown in left two panels. Dashed lines (red) via macro-morphological observations (left) and H & E staining (right) indicate the interface of the bulge and SB region. Boxed area in the left panels that is H & E stained to indicate the bulge, and SB area is shown at a higher magnifi cation in the right panel. The bulge region was immune-stained with anti-CD49f (red, left) and anti-CD34 (red, centre) antibodies and with Hoechst 33258 dye (blue). Black broken lines in high-magnified H & E indicate the interface of epithelium of the hair follicle. IF, infundibulum; RW, ringwulst; 1/2, half portion of hair follicle. Scale bars, 100 μm. (d) Histological and ALP analyses of the bulb area of a natural vibrissa and of primary cultures of DP cells. Hair bulb (left two) and cultured DP cells (right two) were anlaysed via enzymatic staining of ALP. The red dashed line indicates Auber?s line. Scale bars, 100 μm. (e) Longitudinal sections of bioengineered pelage during eruption and growth processes mediated by an inter-epithelial tissue-connecting plastic device (with guide). The counterpart is shown as cyst formation with a bioengineered pelage follicle at 14 days after intracutaneous transplantation (without guide). H & E staining (upper) and fluorescent microscopy (lower) of the bioengineered hair follicles at 0, 3 and 14 days after transplantation. Scale bars, 100 μm. (f) Macro-morphological observations of the bioengineered hairs during the eruption and growth of bioengineered pelages (upper) and vibrissae (lower), including just after transplantation at day 0 (left), the healing of the wound at day 3 (centre), eruption of the hair shaft and growth at day 14 in the bioengineered pelage and 37 days in the vibrissa (right). Scale bars, 1.0 mm.

To prevent epithelial cyst formation and associations between the epithelium of the host skin and the bioengineered hair follicle germ, we developed an inter-epithelial tissue-connecting plastic device that used a nylon thread as a guide for the infundibulum direction via insertion into the bioengineered germ (Fig. 1b). Three days after transplantation, the epithelial layer of the bioengineered germ had extended along the guide to the host skin epithelium, and the resulting wound was allowed to heal by maintaining the eruption of the guide, whereas the sample without a guide formed an epithelial cyst (Fig. 1e). At 14 days after the transplantation of the bioengineered germ, with or without the nylon thread into the dermal layer, the eruption and growth of black hair shafts were observed at a frequency of 94% or 38% (n=78 or 8), respectively (Fig. 1e,f). The bioengineered vibrissa follicle germ was also erupted using the inter-epithelial tissue-connecting plastic device at 20.5±6.0 (n=46) days, with a resulting frequency of 74% (n=62; Fig. 1c). However, the bioengineered vibrissae produced unpigmented hairs with a frequency of 95.5% (n=46; Fig. 1f).

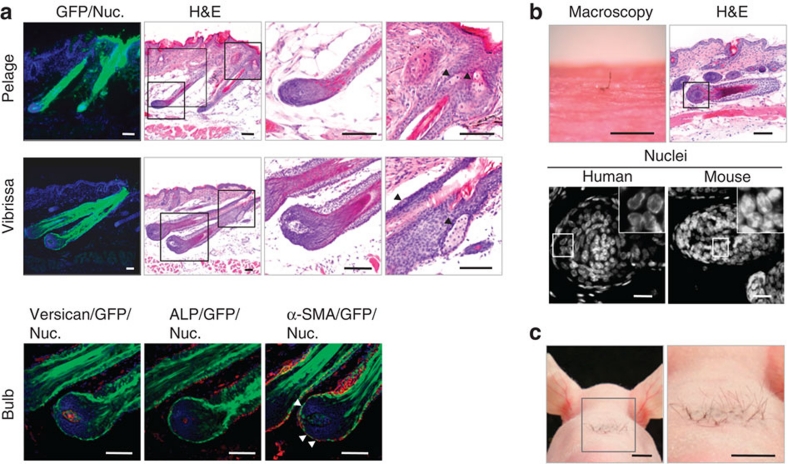

Both the bioengineered pelage follicle and the vibrissa follicle formed correct structures comprising an infundibulum and sebaceous gland in the proximal region as well as a hair matrix, hair shaft, inner root sheath, outer root sheath (ORS), DS and DP (Fig. 2a). Each natural and bioengineered vibrissa follicle contained 500~1,000 DP cells (Fig. 2a). The bioengineered vibrissa follicle germs generated not only hair follicles in the variable region but also infundibulum and sebaceous gland structures in the permanent region, and in contrast to the bioengineered pelage follicle, the follicle-derived cells did not distribute among the surrounding cutaneous tissues (Fig. 2a). DP cells in the bioengineered vibrissa follicle were also found to express alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and versican, and the thin outermost dermal layer of the hair bulb was observed to express α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; Fig. 2a). These results indicate that the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicle germs can regenerate structurally correct follicles and hair shafts following intracutaneous transplantation.

Figure 2. Hair follicle regeneration via the intracutaneous transplantation of a bioengineered hair follicle germ.

(a) Histological and immunohistochemical analyses of bioengineered pelage (upper) and vibrissa (middle) follicles. The boxed areas in the low-magnification H & E panels are shown at a higher magnification in the right panels. The arrowhead indicates a sebaceous gland. Scale bars, 100 μm. The hair bulb of a bioengineered hair follicle was immunostained with anti-versican (lower left) and α-SMA (arrowheads, lower right) antibodies and also enzymatically stained for ALP (lower centre). Scale bars, 50 μm. (b) Bioengineered human hair produced by the transplantation of a human bioengineered hair follicle germ was reconstituted by bulge-derived epithelial cells and the intact DPs of human scalp hair follicles. At 21 days after transplantation, the bioengineered human hair was photographed (microscopy) and analysed by H & E staining. The species identity of the bioengineered hair follicle was analysed, according to the nuclear morphological features (right panels)40. The boxed areas are shown at a higher magnification in the insets. Scale bar, 500 μm for microscopy, 100 μm for H & E, and 20 μm for nuclear staining. (c) High-density intracutaneous transplantation of the bioengineered follicle germs. A total of 28 independent bioengineered hair follicle germs were transplanted into the cervical skin of nude mice, and they displayed high-density hair growth at 21 days after transplantation. Scale bars, 5 mm.

Furthermore, the human bioengineered hair follicle germ, which was composed of the dissociated bulge region-derived epithelial cells and scalp hair follicle-derived intact DPs of an androgenetic alopecia patient, grew a pigmented hair shaft in the transplantation area within 21 days after intracutaneous transplantation into the back skin of nude mice (Fig. 2b). This bioengineered hair follicle formed the correct structures, that is, an infundibulum and sebaceous gland in the proximal region as well as a hair matrix, hair shaft, inner root sheath, ORS, DS, and a DP containing ~500 cells (Fig. 2b). By analysing the nuclear morphology with Hoechst staining40, we confirmed that the cells in the bioengineered hair follicle were of human origin (Fig. 2b).

It is preferable for a clinically applicable hair regeneration therapy to utilize autologous follicular unit transplantation (FUT), which is the most popular treatment for androgenic alopecia41. To achieve hair follicle regeneration at hair densities of 120 or 60–100 hair shafts cm−2 of normal scalp or in FUT treatment41, respectively, twenty-eight bioengineered hair germs were transplanted into a cervical skin circle with a diameter of 1 cm. At 14 to 21 days after transplantation, the bioengineered hairs were erupted at a high density of 124.0±17.3 hair shafts cm−2 (n=3; Fig. 2c). These results indicated that similar to FUT therapy, the transplantation of bioengineered hair follicle germs could be applied as a treatment for androgenic alopecia.

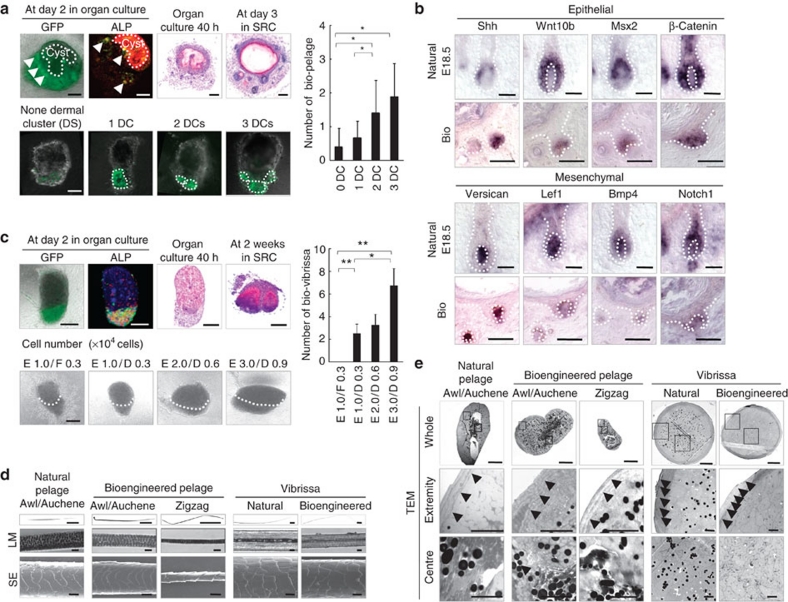

Regulation of hair follicle number and hair shaft features

We next analysed the formation of pelage follicles from the bioengineered follicle germ (Fig. 3a). These analyses demonstrated that the bioengineered pelage follicles, which contain EGFP-labelled mouse-derived mesenchymal cells, could be induced to form autonomously assembled cell aggregates with high-intensity green fluorescence and alkaline phosphatase expression at the boundary between epidermal and mesenchymal cell layers after 2 days in an organ culture (Fig. 3a). After 3 days in an SRC, the bioengineered pelage follicle germ faithfully reproduced the expression of required signalling network genes, such as Shh, Wnt10b, Msx2, β-catenin, Versican, Lef1, Bmp4 and Notch1, which have essential roles in early hair follicle development (Fig. 3a,b)15,17. After the isolation of the bioengineered pelage follicle germ with different numbers of condensed dermal cell aggregates, we found that the number of bioengineered pelage follicles was linearly correlated with that of the condensed dermal cell aggregates (Fig. 3a). These results also indicated that the condensed dermal cells and surrounding epithelial cells recapitulated hair follicle morphogenesis during embryonic organogenesis.

Figure 3. Control of the number and features of the bioengineered hairs.

(a) Analysis of EGFP fluorescence (green), ALP activity (red) and H&E staining in bioengineered pelage follicles reconstituted from normal epithelial cells and EGFP-labelled mesenchymal cells derived from embryonic skin at 2 days in organ culture (upper left) and subsequently transplanted into the subrenal capsule (SRC, upper left). Dermal cell clusters (DCs) in the bioengineered pelage germ were detected by EGFP fluorescence under confocal imaging (lower left). The number of bioengineered pelage follicles regenerated in vivo from the bioengineered hair follicle germ is shown in the lower left panels. The data are shown as the mean±s.d. (n>9). P<0.01 (*) and P<0.05 (**), analysed by t-test. Scale bars: 200 μm for H&E, 50 μm for immunofluorescent microscopy images, 1 mm for macroscopic images. (b) In situ hybridization analysis of the expression of regulatory genes during folliculogenesis in the natural and bioengineered pelage follicle in vivo. Dotted lines indicate the epithelial–mesenchymal boundary. Scale bars: 200 μm. (c) Analyses of EGFP fluorescence, enzymatic staining of ALP and H&E staining in adult vibrissa-derived bioengineered hair germ after 2 days in organ culture (upper left). Bioengineered vibrissa follicles regenerated in SRC for 2 weeks were also analysed using H&E staining. The bioengineered vibrissa germs were reconstituted using bulge epithelial cells (E) and primary culture DP cells (D) with various cell numbers (lower left), and murine sole skin dermis-derived fibroblasts (F) were used as a control for DP cells. The dotted lines in the lower left panels indicate the epithelial–mesenchymal boundary. The number of bioengineered vibrissa follicles regenerated from the in vivo transplantation of bioengineered hair follicle germ reconstituted under various conditions is described in the lower left. Data are shown as the mean±s.d. (n>4). P<0.01 (*) and P<0.05 (**) analysed by t-test. Scale bars, 100 μm. (d and e) Microscopic observation of the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa shafts. The hair shafts were analysed by using light microscopy (LM), SEM and TEM. Whole (TEM, upper), high-magnification extremity (middle), and central regions of the hair shaft (lower) are shown. Cuticle layers (arrowheads) and dense medullary granules (arrow) are shown in the fine TEM photographs of the extremity and centre regions. Scale bars, 1 mm for low magnification (LM), 20 μm for high magnification of LM and SEM, 10 μm for whole TEM and 2 μm for fine TEM.

We further observed the development of the bioengineered vibrissa follicle germ. The DP cells in the follicle germ were all observed to express ALP and form autonomous cell aggregates, and epithelial cyst formation was not detected after two days of culture (Fig. 3c). These results indicate that all of the adult vibrissa-derived bulge region epithelial cells and cultured DP cells can participate in bioengineered follicle formation. Furthermore, the number of the bioengineered vibrissa follicles also correlated with the number of bulge-derived epithelial and primary-cultured DP cells in the preparation of bioengineered follicle germs (Fig. 3c). These results suggest that the number of bioengineered vibrissa follicles depends on the quantity of follicle-forming cells in bulge-derived epithelial and primary-cultured DP cells, and they show that this procedure can provide a precise transplantation technology for future hair regeneration therapy.

The distinct hair follicle types, which are classified into awl/auchene, guard, zigzag and vibrissa hair shafts in murine skin based on properties such as length, thickness, kinks and hardness, are thought to be specified by DP cell types through the communication between DP cells and overlying epithelial cells34,42,43. The bioengineered pelage follicle germs were found to produce all types of pelage hairs in accordance with their follicle fate as determined during embryonic development (Fig. 3d). The bioengineered vibrissa follicle germ regenerated a vibrissa-type hair shaft (Fig. 3d). The bioengineered hair shafts had the correct morphological and histological structures, including the hair medulla, cortex and cuticle, as observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Fig. 3d). The pelage-type hair shafts were distinguishable from the vibrissa-type shafts by transmission electron microscopic analysis (TEM) of the cross-sectional shapes (Fig. 3e). The natural and bioengineered pelage hairs both had a central cavity corresponding to a ladder-like structure observed by light microscopy44, although these structures were not observed in the vibrissae (Fig. 3e). Dense medullary and melanin granules were present in the central cavity of natural and bioengineered pelages (Fig. 3e)43,44. The outermost layer of the natural and bioengineered pelage-type hair shafts were surrounded by a thin cuticle comprising two to four layers (Fig. 3e). The bioengineered vibrissae, which had a six-layer-thick cuticle, were similar to natural vibrissae (Fig. 3e). Melanin granules were found in the pigmented natural hairs. However, the unpigmented bioengineered vibrissa hair had no detectable melanin granules (Fig. 3e). These results indicate that our bioengineering method for hair follicle regeneration can reproduce all hair types with correct hair structures in accordance with the fate of their follicle, which is determined during embryonic development.

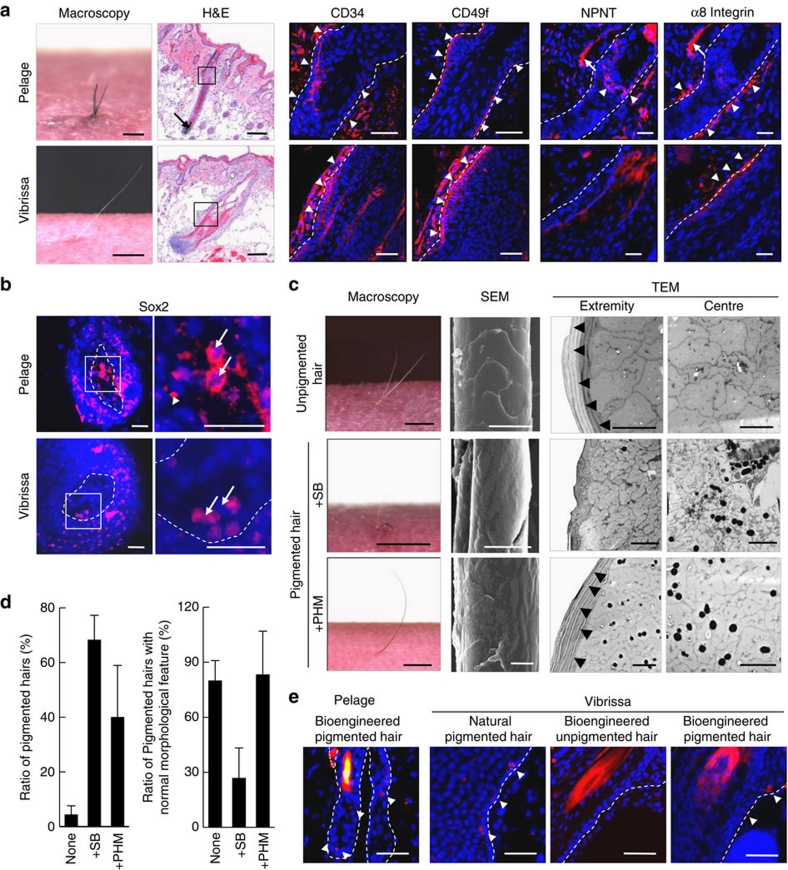

Hair follicle stem cell niches in the hair follicle

We next investigated whether various stem/progenitor cells and their niches were reconstructed in the bioengineered hair follicles. The bioengineered hair follicles were identified by their EGFP expression (Fig. 2a) and/or hair features such as black hair colour (Fig. 4a). These follicles were also identified based on the size of the hair bulbs of the bioengineered vibrissa follicles, which had a mean diameter of 251±32 μm (n=10) in contrast to the diameter of 84±19 μm (n=10; Fig. 4a) for the host pelages of nude mice. The epithelial stem cell markers, CD34 and CD49f, were observed in the bulge region of the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles (Fig. 4a). Nephronectin (NPNT), which is also expressed in follicle epithelial stem cells in the bulge region and provides the microenvironment for arrector pili muscle development by binding with the α8β1 integrin of mesenchymal progenitor cells26, was detected in the bulge region-epithelial stem cells of the bioengineered pelage follicle. In contrast, NPNT was not detected in the bulge region of the bioengineered vibrissae (Fig. 4a). The α8 integrin was distributed in the dermal cells in the bulge ORS layer of the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles (Fig. 4a). Sox2-positive DP cells (Sox2 is a mesenchymal stem cell marker), which retain multilineage differentiation potential in vivo42,43, were also detected in the DPs of the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Rearrangement of follicular stem cells and their niches in the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles. (a) Immunohistochemical analysis of the bulge region in a bioengineered pelage (upper) and vibrissa (lower) follicle.

Boxed areas in the left panels (H&E staining) are shown as immunofluorescent microscopy images in the right panels. The bulge region was analysed by immunostaining with specific antibodies for CD34, CD49f, NPNT and α8 integrin. The nuclei were stained using Hoechst 33258 (Nuc, blue). Broken lines indicate the outermost part of the hair follicle. Arrowheads indicate positively stained areas. Scale bars, 200 μm for H&E, 50 μm for immunofluorescent microscopy images, 1 mm for macroscopy. (b) Immunohistochemical analysis of the DP in a bioengineered pelage (upper) and vibrissa (lower) hair follicle with anti-Sox2 antibodies. Boxed areas in the left panel are shown at a higher magnification in the right panels. Nuclei were stained using Hoechst 33258 (Nuc, blue). Broken lines indicate the outermost limit of the hair follicle. Arrows indicate positively stained nuclei. Scale bars, 50 μm. (c) Analyses of hair pigmentation of the bioengineered vibrissae by various combinations with the bioengineered vibrissa follicle cell components. The bioengineered vibrissa follicle germ, which was reconstituted between the bulge region-derived epithelial stem cells and the primary cultured DP cells (upper), was combined with the sub-bulge (+SB; middle) or proximal region of the hair matrix (+PHM; lower). These bioengineered hair shafts were analysed by macroscopic (left), SEM (centre) and TEM (right 2 panels) observations. Scale bars, 1 mm for macroscopy, 20 μm for SEM and 2 μm for TEM. (d) The frequencies of pigmented hair shafts (left) and pigmented hairs with normal morphological features (right) were compared. The data are presented as the mean±s.e. from three individual experiments; n=5–12 and n=3–8 per experiment in the +SB and +PHM conditions, respectively. (e) In situ hybridization analysis of the sub-bulge region of natural and bioengineered hair follicles, using a specific antisense probe for Dct mRNA. The nuclei were stained using Hoechst 33258 (Nuc, blue). The arrowheads indicate Dct mRNA expression in the cells. The broken lines indicate the outermost limit of the hair follicle. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Hair shaft pigmentation is provided by neural crest-derived melanocyte progenitor cells associated with the hair follicle pigmentary unit in the sub-bulge region of vibrissa hair follicles at anagen phases23,24. The white hair shafts of the bioengineered vibrissae could be caused by the loss of neural crest-derived melanocyte stem/progenitor cells (Figs 1c, d, f and 4c). The addition of cells from the sub-bulge (SB) region (Fig. 1d)23,24, which contains melanoblasts in the ORS, caused the bioengineered vibrissae to be pigmented with a black colour at a frequency of 68.3% (n=26; Fig. 4c,d) at 3 weeks after transplantation. The shape, however, was normal with a frequency of 27.0% (n=17; Fig. 4c,d). In contrast, the bioengineered vibrissae derived from regenerated follicles with proximal hair matrix (PHM) region-derived cells (Fig. 2c), which contain immature melanocytes that are the progeny of melanoblasts23,24,25, were pigmented black with a frequency of 40.1% (n=19; Fig. 4c,d) and had the structural properties of natural vibrissae, as assessed by electron microscopy (83.3%, n=6; Fig. 4c,d). The fine structure of the bioengineered vibrissa harbouring PHM region cells was similar to that of natural vibrissae, but the hair that was bioengineered with SB region cells had an abnormal shape with regard to the structure of the cuticle layer and the cortex region (Fig. 4c). Dopachrome tautomerase (Dct) messenger RNA-positive cells, which are neural crest-derived melanocyte stem/progenitor cells23,24,25, were also detected in the SB region of pigmented bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles, but not the unpigmented bioengineered vibrissa follicle, by in situ hybridization (n=10, Fig. 4e). These results indicated that various follicle stem cells and their niches were successfully rearranged in the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles using appropriate epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations.

Bioengineered hair cycles

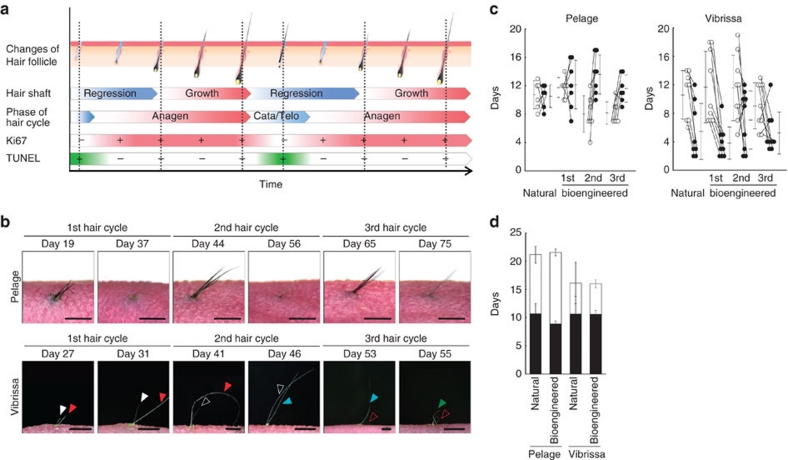

We further analysed the hair cycles, that is, the alternative growth (hair-growing) and regression (non-growing) phases (Fig. 5a), of the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa shafts that had erupted from bioengineered follicles for 80 days (Fig. 5b,c). The bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles repeated the hair cycle at least 3 times during the 80-day period (Fig. 5b,c). For natural pelage follicles transplanted into the back skin of nude mice, the average growth and regression periods were 10.7±2.0 and 10.5±1.6 days, respectively (Fig. 5c,d). For the bioengineered pelage follicles, these periods were 9.3±2.5 and 12.4±2.8 days, as calculated from 3 hair cycle periods (Fig. 5c,d). The growth and regression phases of the natural vibrissa follicles were 10.6±3.4 and 5.5±3.9 days, respectively, and those of the bioengineered vibrissa follicles were 10.7±4.3 and 5.4±3.3 days, respectively (Fig. 5c,d). No significant differences in the hair cycle periods were found between the natural and bioengineered follicles (both pelage and vibrissae; Fig. 5d).

Figure 5. Hair cycle analyses of bioengineered hair follicles.

(a) Schematic representation of the hair cycle defined by histological and macro-morphological observations of the hair shaft. (b) Macro-morphological observations of the hair cycles in a bioengineered pelage (upper panels) and vibrissa (lower panels). In the bioengineered vibrissa, arrowheads (open or closed white, red, blue and green) indicate individual hairs. Closed white and red arrowheads are identical to hairs indicated as opened ones, which erupted from the respective follicles. Scale bars, 1.0 mm. (c) Assessment of the hair growth (open circles) and regression (closed circles) phases of the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa up to 80 days after transplantation. Natural pelages and vibrissae that were transplanted onto the back skin of Balb/c nu/nu mice were also followed as a control. The data are presented as the mean±s.e.; n=5 for natural pelages, n=10 for the bioengineered pelages, n=6 for natural vibrissae, and n=8 for the bioengineered vibrissae. (d) Cycles of hair growth (dark bars) and regression (light bars) of a natural pelage and vibrissa (Natural), and of a bioengineered pelage and vibrissa (Bioengineered), up to 80 days after transplantation. The data are presented as the mean±s.e.; n=6 for natural pelages, n=7 for bioengineered pelages, n=8 for natural vibrissae, and n=9 for bioengineered vibrissae.

To demonstrate that hair growth and regression are dependent on the hair cycle, we performed hair cycle analysis by immunohistochemical detection of Ki67 and TUNEL assays29. To synchronize the hair cycle via hair depilation29, we examined the relationships between the growth and regression phases determined by the observations of hair shafts and hair cycles. The phases observed from hair shaft conditions were conventionally divided into 'Growth start', 'Growth' and 'Growth end' (Fig. 5a). In early anagen phases I-IV, tips of newly growing hair shafts were observed to grow in the skin layer and enter the hair canals. The newly growing hairs erupt and grow through the skin until the end of hair growth in anagen IV–VI. During the anagen phase, proliferation, but not apoptosis, was detected in cells of the hair matrix region in the hair bulb via the expression of Ki67 (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, apoptosis was immediately detected in cells of the hair matrix region during the catagen phase (Supplementary Fig. S1). The resulting retractions of the variable portion of the hair follicle were observed histologically via the appearance of TUNEL-positive cells and the reduction of the proximal tip (Supplementary Fig. S1). During the catagen to telogen phase, hair shafts are not produced and are lost from the hair follicle gradually. It has been indicated that the hair growth and regression phases of the bioengineered hairs were dependent on the histological changing of the bioengineered hair follicles according to the hair cycling (Supplementary Fig. S1). Thus, these results indicated that the bioengineered hair follicle could represent proper hair cycles according to the cell types of origin. It has been suggested that the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles could reproduce these hair cycles, which are maintained by stem cells and provide a stem cell niche.

Piloerection ability of the regenerated hair follicle

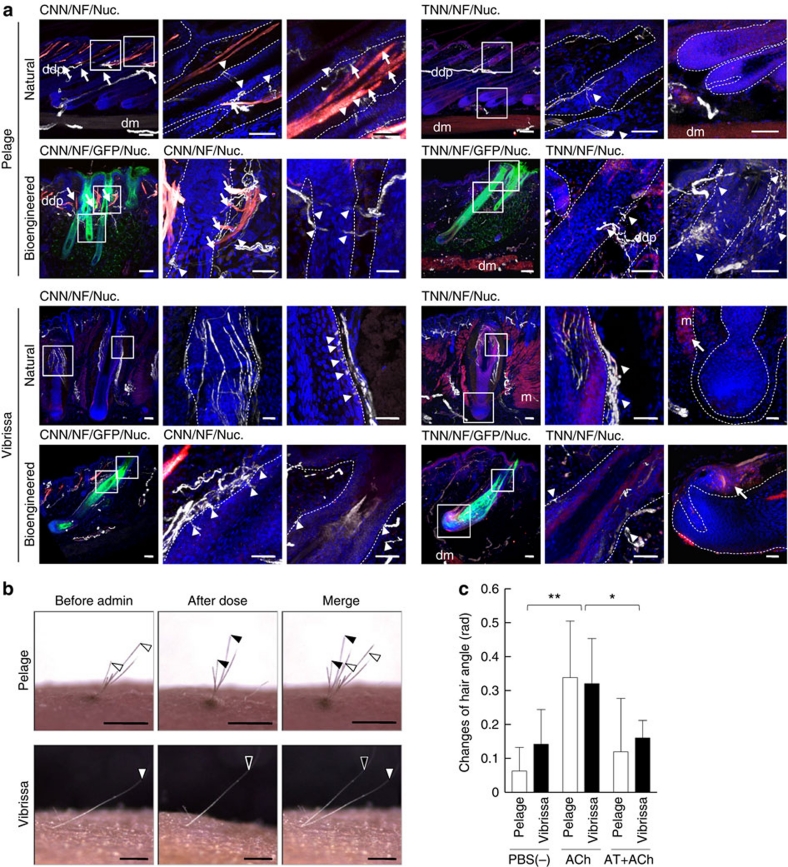

To achieve functional hair follicle regeneration, it is essential that the engrafted follicle be able to connect to the arrector pili muscle and nerve, and that the follicle has a piloerection capability45. The possibility of reconstituting the niche for arrector pili muscle development, in which the cells express NPNT, was demonstrated in the bulge region of the bioengineered pelage (Fig. 4a). The bulge region of a natural pelage follicle is connected to the arrector pili muscle, which is composed of calponin-positive smooth muscle, but not troponin-positive striated muscle, and is innervated through the development of neuromuscular junctions, which surround the arrector pili muscle with sympathetic nerve fibres that extend from a deep dermal nerve plexus (Fig. 6a). All bioengineered pelage follicles were observed to connect to the calponin-positive arrector pili muscle, but not the troponin-positive striated muscle, and to connect to the nerve fibres at the bulge region. These connections were also observed in the natural pelage follicle (n=10; Fig. 6a). The bioengineered vibrissa follicles were connected to the troponin-positive striated muscle cells at the hair bulb regions but not to calponin-positive smooth muscle, in any other areas, which is similar to the structure of the natural vibrissa follicle (Fig. 6a). The bioengineered vibrissa follicles were also connected to nerve fibres, and they formed neuron-follicular junctions in an ORS layer of the bulge region (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. Analyses of the connections to surrounding tissues and the piloerection capability of bioengineered hair follicles.

(a) The connections of the follicles of a natural and EGFP-labelled bioengineered pelage (upper two lines) and natural and EGFP-labelled bioengineered vibrissa (lower two lines) to arrector pili muscles and nerve fibres were analysed by immunohistochemical staining using specific antibodies against calponin for smooth muscle (CNN, red in the left three panels), troponin for striated muscle (TNN, red in the right three panels) and neurofilament H (NF, white). The nuclei were stained using Hoechst 33258 (Nuc, blue). The boxed areas in the left panel in each data set are shown at a higher magnification in the right two panels. The arrows and arrowheads indicate the muscle and nerve fibres connected with pelage follicles, respectively. Broken lines indicate the outermost limit of the hair follicle. Scale bars, 100 μm in low-magnification and 50 μm in high-magnification photographs. ddp, deep dermal plexus; dm, dermal muscle layer; m, muscle. (b) Analysis of the piloerection capability of bioengineered hair follicles following an intradermal injection of ACh. The positions of the hair shafts (black or white arrowheads in the left) moved after this treatment (centre) and merged (right). Scale bars, 1.0 mm. (c) Assessment of hair angle changes associated with the bioengineered pelage (light bars) and vibrissae (dark bars) before and after the administration of ACh, without or with atropine (AT+ACh). The data are shown as the mean±s.e.; n=10 for the bioengineered pelage and n=6 for the bioengineered vibrissa. P<0.01 (*) and P<0.05 (**) were defined as statistically significant, as analysed by t-test.

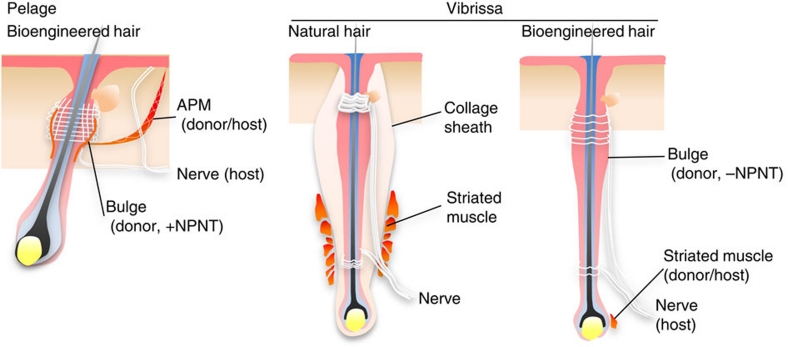

Finally, to investigate whether the bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles possessed the capacity for piloerection, 1 μg of ACh was administered intradermally in the vicinity of the engrafted follicles, and the angles of the hair shafts before and after this treatment were calculated (Fig. 6b,c). ACh exposure significantly increased the angle of piloerection in the bioengineered pelage and vibrissae compared with a control (Fig. 6b,c). In contrast, an anti-cholinergic agent, atropine (AT), inhibited this effect (Fig. 6c). These results indicate that the bioengineered hair follicles have a piloerection ability that is comparable to that of natural follicles45. These findings indicated that our bioengineered follicles could induce selective connections with the appropriate types of muscles and nerve fibres, and they showed that these follicles were able to achieve piloerection through the rearrangement of stem cells and their niches (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Model of the autonomous connections of the bioengineered hair follicles with surrounding tissues in adult skin.

The bioengineered pelage and vibrissa follicles were connected with other tissues such as nerve fibres, arrector pili muscles and striated muscle, which were derived from host and/or donor cells. The bioengineered pelage follicle autonomously connected with smooth muscle as a result of the reproduction of the NPNT-expressing bulge region in a manner similar to that of the natural pelage. Neither NPNT expression nor smooth muscle connection was detected in bulge regions of the natural and bioengineered vibrissa follicles.

Discussion

In this study, we successfully demonstrate fully functional bioengineered hair follicle regeneration that produces follicles that can repeat the hair cycle, connect properly with surrounding skin tissues and achieve piloerection. This regeneration occurs through the rearrangement of various follicular stem cells and their niches. These findings significantly advance the technological development of bioengineered hair follicle regenerative therapy.

Hair regeneration methods that rely on the reproduction of epithelial–mesenchymal interactions have been attempted in several previous studies31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. It was also reported that the aggregation of dissociated epithelial and mesenchymal cells induced to form hair follicle self-assemblies during embryonic hair follicle development could be reproduced34,35,36,37,38. The replacement of hair-inductive mesenchymal cells in an amputated hair follicle19,20 or in glabrous skin33 has also been reported as an analogy to the regeneration of the anagen phase in the adult hair cycle. In hair growth after birth, the position of the infundibular opening and hair shaft eruption are determined by the connection between the hair follicle and the interfollicular epidermis, and this position is maintained as a follicle-invariable region, during hair cycling16. Our bioengineered vibrissa follicle germ that was reconstituted using adult follicle-derived stem cells successfully regenerated the hair follicle following intracutaneous transplantation. Hair shafts also erupted from this bioengineered germ with the proper connections to the surrounding host tissues. Hence, our findings indicate that it is possible to not only restore a hair follicle but also to re-establish successful connections with the recipient skin by intracutaneous transplantation of the bioengineered follicle germ.

Stem cells with organ-inductive potential exist only during embryonic organogenesis and are maintained as tissue stem cells in the stem cell niche of each organ to enable tissue repair after birth17,46. It is well known that the hair follicle organ-inductive epithelial and mesenchymal stem cells provide a source of differentiated hair follicle cells that enable hair cycling to occur over the lifetime of a mammal16,47. Thus, it is logical for hair follicle regenerative therapy to utilize organ-inductive stem cells of epithelial and mesenchymal origin that are isolated from adult tissues34,35,36,37,38,39,48,49,50. It is also essential to rearrange these various stem cells and their niches in the bioengineered follicle to reproduce enduring hair cycles15,30,47. The sub-bulge, bulge and the bulge-to-sebaceous gland regions provide niches for epithelial stem cells and melanoblast stem cells21,22,23,24,25. In contrast, stem/progenitor cell populations that can differentiate into DS cells, adipocytes, cartilage cells and fibroblasts are found among the DP cells18,19,20,42. Our bioengineered hair follicle can regenerate and sustain hair cycles according to the origin of its cells (that is, pelage or vibrissa), which suggests that bioengineered follicles have the potential to maintain stem cells through the reconstitution of niches for epithelial stem cells and DP cells. These observations also provide insight into the formation and maintenance of stem cell niches in their microenvironments9,30,47.

For hair regenerative therapy, it is critical to consider whether bioengineered hair follicles can regenerate normal inherent traits41, physiological functions such as hair shaft types43, qualities30, and cooperation with host cutaneous tissues including the arrector pili muscle and nerve system26,51,52. Properties of the hair shaft, which reflect the function of the hair in the body region14,15,16, are regulated by hair follicle mesenchymal DP and DS cells and are also modulated by the expression of various genes in the epidermis15,16,17. It is also thought that hair pigmentation is controlled by melanocyte differentiation and the proliferation of melanocyte-lineage stem cells below the bulge region23,24,25. Thus, hair properties can be controlled by the arrangement of cell types during the regeneration of the bioengineered hair follicle germ34,30,47. We provide evidence for this arrangement by showing that bioengineered hair with a proper shape and colour can be generated through the appropriate cell populations, such as bulge-derived epithelial cells, DP cells, and the PHM region-derived cells, but not sebaceous gland region-derived cells. Our findings thus provide new insights into the regulation of hair properties and strongly suggest that these characteristics could be properly restored by cell processing for organ regeneration and by the transplantation of bioengineered hair follicle germ.

The peripheral nervous system has essential roles in organ function and the perception of noxious stimuli, such as pain and mechanical stress52,53. The restoration of the nervous system is thus a critical issue to be addressed by organ replacement regenerative therapy13,53. Previously, we demonstrated, in the successful regeneration of a tooth, the proper perception of noxious stimuli mediated by trigeminal innervation13,53. In the hair follicle, the follicles, pelage and vibrissae achieve piloerection using the surrounding arrector pili muscle through the activation of the sympathetic nerves26. The rodent vibrissa also functions as a sensory organ26,45,51,52. We also demonstrate that the nerve fibres and muscles can connect autonomously to the pelage and vibrissa follicle, and that the bioengineered follicles exhibit ACh-induced piloerection. Our findings suggest that the transplantation of a bioengineered hair follicle germ can restore natural hair function and re-establish the cooperation between the follicle and the surrounding recipient muscles and nerve fibres. Thus, the transplantation of bioengineered hair follicle germ is potentially applicable to the future surgical treatment of alopecia.

In conclusion, this study provides novel evidence of fully functional hair follicle regeneration through the rearrangement of various stem cells and their niches in bioengineered hair follicles. Our study provides a substantial contribution to the development of bioengineering technologies that will enable future regenerative therapy for hair loss caused by injury or by diseases such as alopecia and androgenic alopecia. Further studies on the optimization of human hair follicle-derived stem cell sources for clinical applications and further investigations of stem cell niches will contribute to the development of hair regenerative therapy as a prominent class of organ replacement regenerative therapy in the future.

Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 and Balb/c nu/nu mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). C57BL/6-TgN (act-EGFP) OsbC14-Y01-FM131 mice were obtained from Japan SLC and the RIKEN Bioresource Center (Tsukuba, Japan). The mouse care and handling conformed to NIH guidelines, and the requirements of the Tokyo University of Science Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation and dissociation of embryonic skin

E18 mouse embryonic back skin specimens were aseptically isolated in DMEM10/HEPES medium, which was prepared with DMEM (WAKO, Osaka, Japan) containing 10% fetal calf serum (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA), 100 U ml−1 penicillin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 100 mg ml−1 streptomycin (Sigma), and 20 mM HEPES (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on ice, treated with 4.8 U ml−1 dispase (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in PBS at 4 °C for 1 h, and then divided into epithelial and mesenchymal layers. To prepare the epithelial cells, the epithelial layer was treated with 100 U ml−1 collagenase (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) for 40 min at 37 °C, washed with PBS, and treated with 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 10 min. To prepare the mesenchymal cells, the dermal layer was treated with 10,000 U ml−1 collagenase (Worthington) for 1 h at 37 °C with shaking, followed by filtering through a cell strainer (35 μm mesh, BD).

Preparation of various cell populations from adult vibrissae

Adult vibrissa follicles of a1-5, b1-5 and E-H, as defined previously54, were removed from 7- or 8-week-old mice. The DP and other epithelial components were isolated from adult vibrissa follicles from which the collagen sheath was removed. DPs were isolated from anagen I–IV vibrissa follicles, explanted onto a plastic culture dish (BD), and maintained as primary cultures for 9 days, as described previously55. The cultured DP cells were collected with 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen), and single cells were isolated. The bulge region, which was defined as an area from below the sebaceous gland to above the ringwurst23,24, and the sub-bulge region (Fig. 2b), which was defined as the area from below the ringwurst to above the middle of the hair follicle23,24, were then treated for 4 min at 37 °C with PBS containing 4.8 U ml−1 dispase II (BD) and 100 U ml−1 collagenase (Worthington). The epithelial tissue was then treated for 1 hour with 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen), and single cells were isolated using a cell strainer (BD) with a 35 μm pore. The SB region-derived epithelial tissue, which was dissected at the end of the bulge region in the middle of the hair follicle, was also treated for 4 min, at 37 °C, in the dispase II/collagenase (Worthington) solution, as described above. The PHM region, which is located under the Auber's line and surrounds the papillary stalks, was isolated, as previously described56. The SB and PHM region-derived tissues were also treated for 1 hour with 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen), and single cells were then isolated.

Reconstitution of bioengineered murine hair follicle germ

The bioengineered murine hair follicle germs were reconstituted using mouse epithelial and dermal cells, according to the organ germ method reported previously7. The bioengineered pelage follicle germs were reconstituted using embryonic skin epithelial and mesenchymal cells (7.5×103 of each cell type). To analyse the follicle formation in the bioengineered pelage follicle, dermal cell aggregates with high-intensity green fluorescence, in the bioengineered pelage follicle germ, were dissected after 2 days in an organ culture. The bioengineered vibrissa follicle germs were regenerated from 7- to 8-week-old vibrissa-derived bulge region epithelial (1×104 cells) and primary cultured DP cells (3×103 cells). These bioengineered hair germs were then placed onto a cell culture insert (0.4 μm pore diameter; BD) and incubated at 37 °C, for two days, in DMEM10 medium. To investigate the formation of bioengineered vibrissae in the bioengineered germ, the bioengineered germs for the assay were regenerated with various numbers of epithelial and mesenchymal cells. To form inter-epithelial tissue connections between the host skin and the bioengineered hair follicle, a nylon thread guide (8–0 nylon surgical suture; Natsume, Tokyo, Japan) was appended into a bioengineered hair germ through the thrusting epithelial and mesenchymal portions.

Hair pigmentation assay with bioengineered vibrissa

The SB23,24 or PHM56 regions were isolated and trypsinized, as described above. For each of these regions, 200 cells, isolated from the region, were added to 104 bulge-derived epithelial cells and used to reconstitute the bioengineered vibrissa follicle germ, which consisted of 3,000 cultured DP cells. This preparation was intracutaneously transplanted into the backs of nude mice, as described above.

Engraftment of bioengineered hair follicle germ

For hair follicle regeneration, the bioengineered hair germs were ectopically engrafted into the subrenal capsules of 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice, as previously described7,13, or they were intracutaneously transplanted onto the back skin of 6-week-old Balb/c nu/nu mice. Shallow stab wounds, which were nearly parallel to the skin surface and ~0.4 mm vertical and 2.8 mm horizontal from the needle-stick point, were made in the back skin of nude mice with a 20-G Ophthalmic V-Lance (Alcon Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The bioengineered hair follicle germ, which contained a nylon guide, was arranged in the epithelial portion and above, and it was intradermally transplanted into the wounds. The nylon guide was held so that it protruded from the skin surface. The transplantation sites were then covered with surgical bandage tape (Nichiban, Tokyo, Japan). To examine the engraftment of the transplants and to study the hair cycles of the bioengineered hairs, all transplanted sites were observed using a SteREO Lumar V12 and AxioCam fluorescent stereoscopic microscope system (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Observations were made every 2–3 days.

Bioengineering of human hair follicle germ

This procedure was performed with the approval of the ethics board of the Tokyo University of Science and Tokyo Memorial Clinic. Small pieces (1.0–2.0 cm2) of occipital scalp skin were obtained from 39- and 63-year-old male donors, who provided informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The scalp samples were treated with povidone-iodine and 70% ethanol for 10 s, twice successively. The hair follicles in the anagen phase were then dissected at the upper end of the hair bulb, using a surgical knife. The intact DPs and bulge-derived epithelial cells were isolated as described above. The bioengineered hair follicles were then reconstituted using human intact DPs and the bulge region-derived epithelial cells, by using the organ germ method7. At 21 days after transplantation with the inter-epithelial tissue-connecting plastic device, the growth of pigmented hair shafts was observed underneath the epithelium of the host skin. The hair shafts were recovered by cutting into the host epithelium.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections (5 μm) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and observed, using an Axioimager A1 (Carl Zeiss) microscope and AxioCAM MRc5 (Carl Zeiss) camera. For fluorescent immunohistochemistry, frozen sections (10 and 100 μm) were prepared and immunostained, as previously described7,45,53. The primary antibodies were as follows: versican (1:100, rabbit, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA); α-SMA (1:500, rabbit, Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA); integrin α6 (1:500, CD49f; rat, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); CD34 (1:100, rat, eBioscience, California, USA); integrin α8 (1:50, goat, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA); Sox2 (1:250, Cell Signaling Technology Japan, Tokyo, Japan); NPNT (1:50 rabbit, Trans Genic, Kobe, Japan) neurofilament-H (1:500, rat, Chemicon, California, USA); calponin (1:250, rabbit, Abcam); and troponin (1:100, rabbit, Abcam), in blocking solution. The primary antibodies were detected using highly cross-adsorbed Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:500, Invitrogen) for 1 hour at room temperature, together with Hoechst 33258 dye (1:500, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). All fluorescence microscopy images were captured under a confocal microscope: the LSM 780 (Carl Zeiss).

Detection of human cells by nuclear staining

The human bioengineered hair follicles were dissected, fixed in 10% formalin, processed for standard paraffin embedding, and sectioned at 5 μm. Discrimination between mouse and human nuclei was performed as described previously40.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridizations were performed using 10-μm frozen sections. Digoxigenin-labelled probes for specific transcripts were prepared by PCR, with primers designed using published sequences (Supplementary Table S1). The mRNA-expression patterns were visualized by immunoreactivity with anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphatase-conjugated Fab-fragments (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Electron microscopy

For SEM observations, the hair shafts were dehydrated in 100% ethanol. After coating with platinum, the samples were examined with a Hitachi S-4700 SEM (Hitachi High-Tech, Tokyo, Japan) at 10–15 kV. SEM observations were performed mainly for the surfaces of the lower portion of the hair shafts57. For TEM analysis, the samples were embedded and fixed, as previously described58. Ultrathin sections were prepared, as previously described58, and examined using a Hitachi H-7600 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi) with an accelerating voltage of 75 kV.

Piloerection of bioengineered hair

To investigate whether bioengineered hairs could reproduce the piloerection ability, the effects of a neurotransmitter agent, 10 mg ml−1 acetylcholine (Sigma), and of a piloerection inhibitor, 1 μl of a 100 mg ml−1 atropine sulphate solution (Sigma), were examined, as described previously45,59,60. The piloerection angle was measured by microscopic image analysis and compared with the pre-injection angle as the reference point.

Author contributions

T. Tsuji and K.T. designed the research plan; K.T., K.A., H.T., N.I., T.H., M.O. and K.N. performed the experiments; T.I., and T. Tachikawa performed electron microscopic analyses; K.T., A.S., A.T. and T. Tsuji discussed the results; and K.T. and T. Tsuji wrote the paper.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Toyoshima, K.-e. et al. Fully functional hair follicle regeneration through the rearrangement of stem cells and their niches. Nat. Commun. 3:784 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1784 (2012).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Okabe (Osaka University) for providing the C57BL/6-TgN (act-EGFP) OsbC14-Y01-FM131 mice. We are grateful to Dr. Y Ishii (Skin clinic, Omiya, Japan) for advice about surgical techniques. We are also grateful to K. Isumi, C. Gotoh, T. Kanayama, F. Tobe, A. Iwadate, S. Noguchi and Y. Yuge for technical assistance.

References

- Sharpe P. T. & Young C. S. Test-tube teeth. Sci. Am. 293, 34–41 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González F., Boué S. & Belmonte J. C. Methods for making induced pluripotent stem cells: reprogramming à la carte. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 231–242 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya S. G., Jungvid H. & Kumar A. Skin tissue engineering for tissue repair and regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 14, 105–118 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida K. et al. Functional bioengineered corneal epithelial sheet grafts from corneal stem cells expanded ex vivo on a temperature-responsive cell culture surface. Transplantation 77, 379–385 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pispa J. & Thesleff I. Mechanisms of ectodermal organogenesis. Dev. Biol. 262, 195–205 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini C. et al. Use of autologous dermal graft in the treatment of parotid surgery wounds for prevention of neck scars: preliminary results. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 37, 174–178 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao K. et al. The development of a bioengineered organ germ method. Nat. Methods 4, 227–230 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman R. M. The pluripotency of hair follicle stem cells. Cell Cycle. 5, 232–233 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong C. M., Wu P., Plikus M., Jiang T. X. & Bruce Widelitz R. Engineering stem cells into organs: topobiological transformations demonstrated by beak, feather, and other ectodermal organ morphogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 72, 237–274 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen P. Genetic basis of tooth agenesis. J. Exp. Zool. B. Mol. Dev. Evol. 312, 320–342 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotti A. & Eisbruch A. Reducing xerostomia through advanced technology. Lancet Oncol. 12, 110–111 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall V. A. et al. Hormones and hair growth: variations in androgen receptor content of darmal papilla cells cultured from human and red deer (Cervus elaphus) hair follicles. J. Invest. Dermatol. 101, 114S–120S (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima M. et al. Functional tooth regeneration using a bioengineered tooth unit as a mature organ replacement regenerative therapy. PLoS One. 6, e21531 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong C. M. Molecular Basis of Epithelial Appendage Morphogenesis (ed. Chuong C. M.) (R.G. Landes Company: Austin, Texas, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. Scratching the surface of skin development. Nature. 445, 834–842 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy M. H The secret life of the hair follicle. Trends Genet. 8, 55–61 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenn K. S. & Paus R. Controls of hair follicle cycling. Physiol. Rev. 81, 449–494 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamao M. et al. Contact between dermal papilla cells and dermal sheath cells enhances the ability of DPCs to induce hair growth. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130, 2707–2718 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda C. A., Whitehouse J., Reynolds A. J. & Hole N. Hair follicle dermal cells differentiate into adipogenic and osteogenic lineages. Exp. Dermatol. 12, 849–859 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda C. A. & Reynolds A. J. Hair follicle dermal sheath cells: unsung participants in wound healing. Lancet 358, 1445–1448 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima H., Rochat A., Kedzia C., Kobayashi K. & Barrandon Y. Morphogenesis and renewal of hair follicles from adult multipotent stem cells. Cell 104, 233–245 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C., Lowry W. E., Geoghegan A., Polak L. & Fuchs E. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell 118, 635–648 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura E. K. et al. Dominant role of the niche in melanocyte stem-cell fate determination. Nature 416, 854–860 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura E. K., Granter S. R. & Fisher D. E. Mechanisms of hair graying: incomplete melanocyte stem cell maintenance in the niche. Science. 4, 720–724 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisada T. et al. Transgene expression of steel factor in the basal layer of epidermis promotes survival proliferation differentiation and migration of melanocyte precursors. Development. 125, 2915–2923 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H. et al. The basement membrane of hair follicle stem cells is a muscle cell niche. Cell 144, 577–589 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendl M., Polak L. & Fuchs E. BMP signaling in dermal papilla cells is required for their hair follicle-inductive properties. Genes Dev.. 22, 543–557 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco V. et al. A two-step mechanism for stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 4, 155–169 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner G. et al. Analysis of apoptosis during hair follicle regression (catagen). Am. J. Pathol. 151, 1601–1617 (1997). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong C. M., Cotsarelis G. & Stenn K. Defining hair follicles in the age of stem cell bioengineering. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 2098–2100 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda C. A., Horne K. A. & Oliver R. F. Induction of hair growth by implantation of cultured dermal papilla cells. Nature 311, 560–562 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda C. A., Oliver R. F., Reynolds A. J., Forrester J. C. & Horne K. A. Human hair follicle regeneration following amputation and grafting into the nude mouse. J. Invest. Dermatol. 107, 804–807 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenn K. et al. Bioengineering the hair follicle. Organogenesis 3, 6–13 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg W. C. et al. Reconstitution of hair follicle development in vivo: determination of follicle formation, hair growth, and hair quality by dermal cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 100, 229–236 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto J. et al. Selective activation of the versican promoter by epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during hair follicle development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 7336–7341 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichti U., Anders J. & Yuspa S. H. Isolation and short-term culture of primary keratinocytes, hair follicle populations and dermal cells from newborn mice and keratinocytes from adult mice for in vitro analysis and for grafting to immunodeficient mice. Nat. Protoc. 3, 799–810 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. et al. Organogenesis from dissociated cells: generation of mature cycling hair follicles from skin-derived cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 124, 867–876 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour S. K., Teti K. A., Wu K. Q. & Morris R. J. A simple in vivo system for studying epithelialization, hair follicle formation, and invasion using primary epidermal cells from wild-type and transgenic ornithine decarboxylase- overexpressing mouse skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 117, 1674–1676 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannik J., Alzayady K. & Ghazizadeh S. Regeneration of multilineage skin epithelia by differentiated keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130, 388–397 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris C., Bernard B. A. & Dhouailly D. Adult epidermal keratinocytes are endowed with pilosebaceous forming abilities. J. Invest. Dermatol. 3, 491–498 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger W., Shapiro R., Unger M. A. & Unger U. Hair Transplantation 5th edn (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Biernaskie J. et al. SKPs derive from hair follicle precursors and exhibit properties of adult dermal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 5, 610–623 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driskell R. R., Giangreco A., Jensen K. B., Mulder K. W. & Watt F. M. Sox2-positive dermal papilla cells specify hair follicle type in mammalian epidermis. Development 136, 2815–2823 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojiro O. Fine structure of the mouse hair follicle. J. Electron Microsc. 21, 127–138 (1972). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A. et al. Single follicular unit transplantation reconstructs arrector pili muscle- and nerve-connections and restores functional hair follicle piloerection in preparing,. J. Dermatol. 39, 1–6 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K. B. et al. Lrig1 expression defines a distinct multipotent stem cell population in mammalian epidermis. Cell Stem Cell 4, 427–439 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L. F. & Chuong C. M. Building complex tissues: high-throughput screening for molecules required in hair engineering. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 815–817 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudinot S., Nicolas M., Oshima H., Rochat A. & Barrandon Y. Long-term renewal of hair follicles from clonogenic multipotent stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14677–14682 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. J. et al. Capturing and profiling adult hair follicle stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 411–417 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti P. et al. Microenvironmental reprogramming of thymic epithelial cells to skin multipotent stem cells. Nature 466, 978–982 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant R. A., Mitchinson B., Fox C. W. & Prescott T. J. Active touch sensing in the rat: anticipatory and regulatory control of whisker movements during surface exploration. J. Neurophysiol. 101, 862–874 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E. M., Botchkarev V. A., Botchkareva N. V., Tobin D. J. & Paus R. Hair-cycle-associated remodeling of the peptidergic innervation of murine skin, and hair growth modulation by neuropeptides. J. Invest. Dermatol. 116, 236–245 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda E et al. Fully functional bioengineered tooth replacement as an organ replacement therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13475–13480 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim L. & Wright E. The growth of rats and mice vibrissae under normal and some abnormal conditions. J. Embryol. Exp. Morpho. 33, 831–844 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada A., Iwabuchi T., Kishimoto J., Hamazaki T. S. & Okochi H. Long-term culture of mouse vibrissal dermal papilla cells and de novo hair follicle induction. Tissue Eng. 13, 975–982 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A. J. & Jahoda C. A. Hair matrix germinative epidermal cells confer follicle-inducing capabilities on dermal sheath and high passage papilla cells. Development 122, 3085–3094 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton S., Wepf R. & Simon K. Roles for Rac1 and Cdc42 in planar polarization and hair outgrowth in the wing of drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 135, 1277–1289 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie T. et al. Intracellular transport of basement menbrane-type heparan sulphate proteoglycan in adenoid cystic carcinoma cells of salivary gland origin: an immunoelectron microscopic study. Virchows Arch. 433, 41–48 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann K. The isolated pilomotor muscle as an in vitro preparation. J. Physiol. 169, 603–620 (1963). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhouttec P. M. Inhibition by acetylcholine of adrenergic neurotransmission in vascular smooth muscle. Circ. Res. 34, 317–326 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1