Abstract

Context:

In this study, we assessed the relation of possible risk factors with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the survivors of December 2004 tsunami in Kanyakumari district.

Materials and Methods:

We identified cases (n=158) and controls (n=141) by screening a random sample of 485 tsunami survivors from June 2005 to October 2005 using a validated tool, “Impact of events scale-revised (IES-R),” for symptoms suggestive of PTSD. Subjects whose score was equal to or above the 70th percentile (total score 48) were cases and those who had score below or equal to 30th percentile (total score 33) were controls. Analysis was done using statistical package for the social sciences to find the risk factors of PTSD among various pre-disaster, within-disaster and post-disaster factors.

Results:

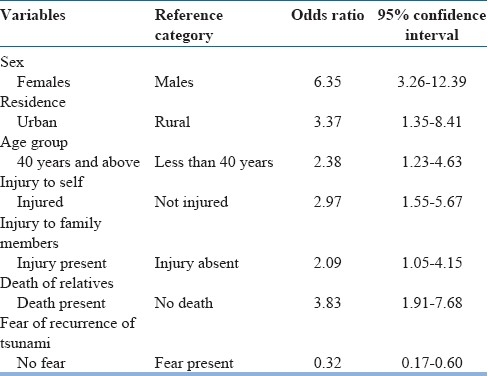

Multivariate analysis showed that PTSD was related to female gender [odds ratio (OR) 6.35, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.26-12.39], age 40 years and above (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.23-4.63), injury to self (OR 2.97, 95% CI 1.55-5.67), injury to family members (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.05-4.15), residence in urban area (area of maximum destruction) (OR 3.37, 95% CI 1.35-8.41) and death of close relatives (OR 3.83, 95% CI 1.91-7.68). Absence of fear of recurrence of tsunami (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.17-0.60), satisfaction of services received (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.36-0.92) and counseling services received more than three times (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26-0.78) had protective effect against PTSD.

Conclusions:

There is an association of pre-disaster, within-disaster and post-disaster factors with PTSD, which demands specific interventions at all phases of disaster, with a special focus on vulnerable groups.

Keywords: Post-traumatic stress disorder, risk factors, tsunami

INTRODUCTION

The tsunami waves that devastated the shorelines of several countries of South and Southeast Asia were triggered by a massive undersea earthquake of magnitude 9 in the Richter scale, off the west coast of northern Sumatra, Indonesia, on December 26, 2004.[1] This tsunami, the worst ever in human history, decimated Southeast Asia, killing more than 300,000 people in 12 countries and leaving more than 1 million people homeless.[2] In India, the devastating tidal waves lashed several coastal districts of Andhra Pradesh, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry. Of these, the worst hit regions were the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, followed by the state of Tamil Nadu.[3] Kanyakumari district was the second most affected district in Tamil Nadu in terms of population affected and lives lost.[3]

Many studies suggest the occurrence of specific mental health disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), grief, depression, anxiety and substance abuse following disasters.[4–8] PTSD was the most commonly found psychological problem in 81% of investigations from developing countries following natural disasters.[9] The risk factors for PTSD can be grouped into pre-disaster, within disaster and post-disaster factors.[10] Since there are only limited data on PTSD and related factors from developing countries, more evidence is required to assist in the development of culturally sensitive strategies to combat the mental health problems. The present study was based on a community sample survey of tsunami survivors in selected villages of Kanyakumari district. Since all the people in the selected area were victims of the tsunami, this population can be thought of as a cohort of tsunami survivors. We did a further case-control analysis on a subsample of subjects, comparable to a nested case-control design. This paper presents the findings of the case-control study in relation to the risk factors of PTSD in the tsunami survivors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

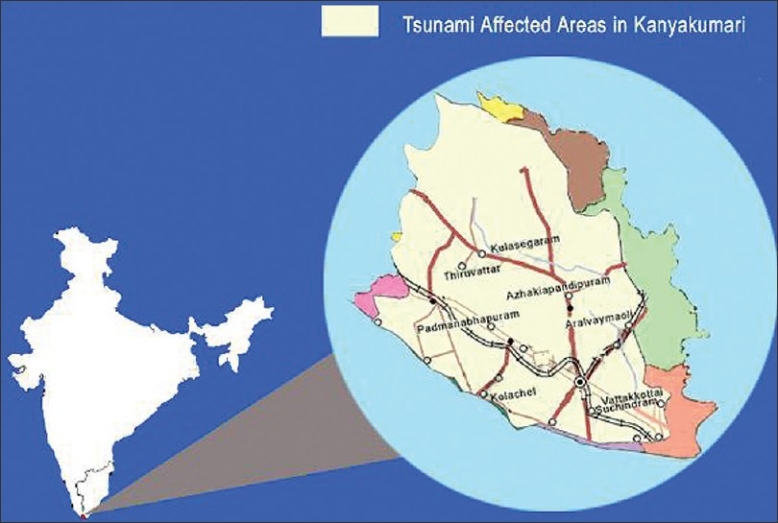

The study was conducted from June 2005 to October 2005, 6 months after the disaster. The cases in the study population were defined as survivors of tsunami, who had PTSD as evidenced by a total score of 48 or more on administration of an instrument, Impact of events scale-revised (IES-R),[11] in Kanyakumari. In order to facilitate easy identification of the cases, we did a cross-sectional survey in four villages in Kanyakumari [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Tsunami affected areas in Kanyakumari

The number of cases required for this study was calculated as 153, after assuming alpha error at 0.05, power at 80% and odds ratio (OR) at 2. The number of subjects to be screened for identifying 153 cases in this population was estimated to be 437, based on the prevalence estimates of PTSD (35%) in samples from other disaster studies.

Hence, after allowing for a shortfall in response rate, a random sample of 485 subjects above the age of 18, living along the sea shore of the urban and rural villages in Kanyakumari, was screened using a locally validated tool, IES-R. Listings of the subjects were obtained from the electoral roll in which the deceased were deleted. The dwellings of most of these subjects were damaged, and hence they had moved to the nearby temporary shelters or relocated to other areas. Since about 25% of the subjects in the study area were displaced, the next person in the electoral roll was considered sequentially to complete the sample. All subjects consented to participate after having been explained the aims of the study, procedures involved, and time required for participation. Informed written consent was obtained by the investigator just before the interview from the subject.

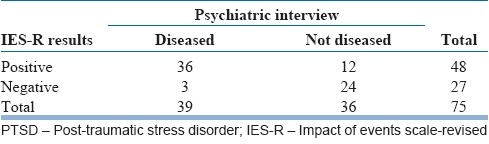

The IES-R was selected as the tool to measure Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM IV) PTSD symptoms. The tool was first translated to Tamil (the local language) and then translated back to English independently. This back-translated version was compared to the original English questionnaire to ensure validity. The tool was suitably modified for Tamil speaking population. The questionnaire was pilot tested before the study. Though the IES-R is a self-administered questionnaire, bearing in mind the low literacy levels of the local population and lack of familiarity with questionnaires, IES-R was used as an interviewer administered questionnaire in this study. A single interviewer read out the questions to each of the subjects in a subsample of this study population and recorded their oral response. A psychiatrist who was blinded about the PTSD symptom score conducted psychiatric interview of each of these subjects in their houses. After completing the data collection, the psychiatric diagnosis was compared with the corresponding PTSD symptom score using IES-R. To determine the accuracy of IES-R in detecting PTSD symptoms, sensitivity and specificity were calculated against the psychiatric diagnosis. The sensitivity and specificity of IES-R were found to be 0.92 and 0.67, respectively, after validation in a subsample of 75 subjects [Table 1].

Table 1.

Diagnosis of PTSD by IES-R

Creamer et al. report that a total score of 33 on the IES-R is a predictor of PTSD.[12] In our study, subjects whose score was equal to or above the 70th percentile (total score 48) were taken as cases and those with a score below or equal to 30th percentile (total score 33) were treated as controls. From the screened subjects, 158 cases and 141 controls were selected as per defined criteria for PTSD, and a total sample size of 299 was made available for the case-control analysis.

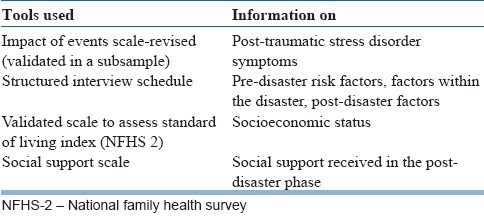

Three interviewers were trained for administering the instruments. The Principal Investigator used to accompany them in the field for data collection. Data were collected using the instruments as given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Instruments

All subjects diagnosed with psychological illness during the study were referred to the nearby private hospital or to the Department of Psychiatry of the nearest Government Medical College for treatment as preferred by the patients and their family. The Principal Investigator, a trained doctor, gave counseling to the participants during the interview, whenever required.

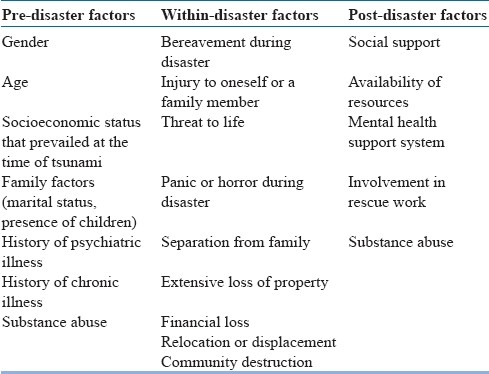

The entire data were analyzed using software Epi info and statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 17. The risk factors of PTSD were grouped into pre-disaster factors, within-disaster factors and post-disaster factors in this study [Table 3]. Unmatched analysis was done to arrive at bivariate ORs and 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates. For multivariate analysis, multiple binary logistic regression analysis was done using SPSS.

Table 3.

Independent variables

RESULTS

In this study, the age group of the participants ranged from 19 to 81 years. We used national family health survey (NFHS-2)[13] methodology for calculating the standard of life (SLI) index as proxy for socioeconomic status. The demographic details of the study subjects are depicted in Table 4.

Table 4.

Profile of the study subjects

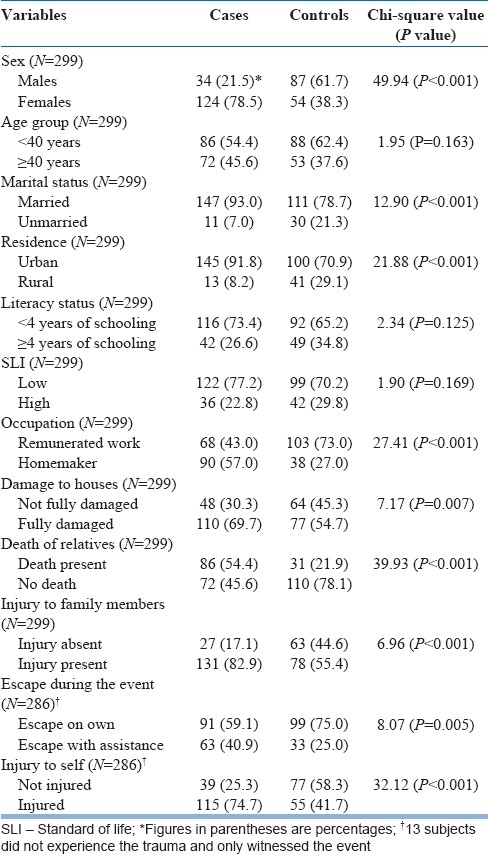

There were more women (78.5%) among cases, whereas men (61.7%) were more in number among controls. A greater proportion of subjects were under 40 years of age among both cases and controls [Table 5].

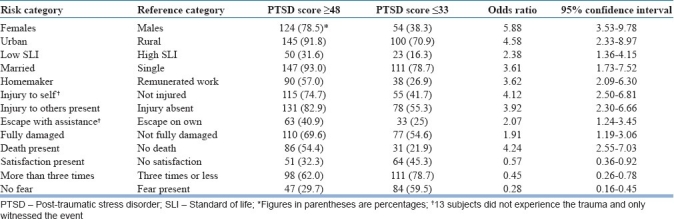

Table 5.

Bivariate analysis showing odds ratio and confidence intervals for the risk factors of PTSD within the study population of tsunami survivors

The odds of having PTSD among the urban residents (men OR 7.20, 95% CI 1.61-32.64; women OR 3.60, 95% CI 1.51-8.57) and those belonging to low SLI (men OR 1.64, 95% CI 0.52-5.21; women OR 5.85, 95% CI 1.58-23.57) were influenced by gender. We could not analyze the influence of gender in the odds of occupation and PTSD, as all homemakers were exclusively women. Contrary to the fact that men in urban areas were at increased risk for PTSD, it was found that women in the rural areas had higher odds for PTSD than those in the urban areas (OR 10.61, 95% CI 2.06-54.63 vs. OR 5.30, 95% CI 3.02-9.27). Analysis of the influence of socioeconomic status on other risk factors showed that there was higher risk for PTSD for women of low SLI than those of high SLI (OR 15.04, 95% CI 4.27-52.95 vs. OR 4.23, 95% CI 1.62-11.02). So also, urban residents with high SLI had higher odds for PTSD than those with low SLI (OR 12.42, 95% CI 1.52-101.77 vs. OR 5.05, 95% CI 0.85-29.92). Other factors like separation from the family and substance abuse (alcohol and tobacco) did not have significant association with PTSD. In short, analysis of risk factors among various strata also vindicates the higher risk of PTSD among women, people belonging to poor socioeconomic background and those who suffered maximum loss during tsunami.

Multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression was done relating case-control status to variables like sex, place of residence, marital status, occupation, age group, SLI, injury to self, injury to family members, escape during the event, death of relatives, fully damaged house, satisfaction of services received, counseling services received and fear of recurrence of tsunami. In the study population, female gender and risk factors such as residence in urban area, persons aged 40 and above, injury during the event, injury to family members, and death of relatives had significant association with PTSD when adjusted for other variables. Absence of fear of recurrence of tsunami was found to have protective effect against PTSD [Table 6].

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis – Results of multiple binary logistic regression analysis (stepwise forward regression)

DISCUSSION

In this study sample, women had 6.35 times higher risk of having PTSD as compared to men, when adjusted for other variables. The higher risk of PTSD among homemakers also strongly supports the vulnerability of women to PTSD as all homemakers were women in our study population. Studies on Oklahoma City bombing survivors and earthquake survivors in Turkey have shown an increased risk of PTSD among women than men.[14,15] The experiences of Oxfam, a non-governmental organization (NGO) which had worked in tsunami affected areas in South India, highlight the gender-specific problems and their role in increasing the stress of women.[16] Other studies related to tsunami and PTSD also emphasize the strong association of female gender as a risk factor of PTSD.[17,18]

During tsunami, there was maximum destruction in the urban area in terms of death and property loss. This study shows that the residents of urban area had higher risk of PTSD as compared to the residents of rural area. This finding is consistent with increased risk of PTSD in areas of maximum destruction.[19,20] Contrary to this, a study of earthquake related PTSD in North China has reported that the village with lower initial exposure had a higher PTSD rate.[21] Another important finding in our study is that the effect of all the protective factors against PTSD was low for the residents of urban area as compared to those in the rural area. This reminds that disasters impact whole communities, not selected individuals. In this study sample, subjects belonging to low SLI had significant risk of PTSD. This is consistent with the finding from several other studies, which shows that lower socioeconomic status is associated with poor mental health outcomes.[22,23] On the contrary, there are some data from India in a disaster setting, suggesting that people of all the socioeconomic strata were equally affected by PTSD.[24]

Tsunami had caused community destruction of enormous magnitude and had created panic along the coastline. The experience had been the same for all the study participants. Hence, it was difficult to analyze the association of factors such as panic or horror during the event and community destruction with PTSD. All the survivors experienced financial loss and property loss, which made the assessment of association of these factors with PTSD difficult.

Among our study subjects, death of a relative and injury to self or family members were significantly associated with PTSD as in other previous reports.[17,25–27] It cuts across gender, SLI and place of residence. Factors like absence of fear of recurrence of tsunami, counseling received more than three times and satisfaction of services received had protective effect for PTSD. Family is often considered as the unit of coping in stressful situations. In our study, 80% of the families were nuclear. Hence, we had not included the impact of family structure as a predictor of PTSD.

Some limitations of our study need to be mentioned. The selection of cases and controls in this study reflects the difficulties in sampling in communities affected by disasters. It was extremely difficult to trace out the displaced tsunami survivors immediately after such a disaster. The only information regarding them was that they had taken asylum in their relatives’ houses. However, the results would have been different if we had included the displaced tsunami survivors in our sample. This means that our case selection procedure could only have pushed the OR toward the null value. The possibility of inter-observer variation in our study has to be considered since the data were collected by three interviewers. Inter-rater reliability could have been assessed, but we had not done this in our study. Though the cut-off score on the IES-R was pegged at 70th percentile, possible overlap of co-morbid conditions and lack of clinical diagnosis has made the sample selection vulnerable.

Implications of our study for prevention of mental health problems can be described in terms of interventions that can be done before, during and after disasters. The marginalized, vulnerable sections in the community (women, people of low socioeconomic status, those who suffered maximum loss) were at higher risk of PTSD in our study. Hence, interventions should be planned in areas prone to natural disasters to protect the disadvantaged against the risk of mental health problems. Disaster workers and officials should acknowledge the vulnerable status of women and specific relief efforts to respond to it. The high death toll and injuries afflicted during the event also contributed to the risk of PTSD. This learning has strong policy implications. All health institutions in disaster-prone areas should be equipped with emergency care facilities to provide care, if needed. The absence of such facilities was one of the reasons for a high death toll in our study area. In the post-disaster phase, rehabilitation activities should be done with community participation and there is evidence to support the role of psychosocial care in reducing the emotional distress for women survivors of tsunami.[28] The results of our study hint that the interventions designed to reduce PTSD in natural disasters like tsunami in developing countries should be targeted toward income generation activities and psychosocial care with special focus on women, people of lower socioeconomic strata and individuals who reside in areas of maximum damage. This study, as in other disaster studies, underscores the rationale for incorporating mental health services as an integral component of disaster policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Sundari Ravindran, the participants and all others who have helped in conducting this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Indian Ocean: Earth quakes and tsunamis; [accessed on 2009 Aug 21]. United States Agency for International Development. Available from: http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/humanitarian_assistance/disaster_assistance/countries/indian_ocean/fy2005/indianocean_et_fs38_05-06-2005.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender E. Psychiatrists find Tsunami mental health consequences severe. [accessed on 2005 Oct 15];International news. Psychiatric News. 2005 40:11–3. Available from: http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content . [Google Scholar]

- 3.No.32-5/2004-NDM-I Government of India Ministry of Home Affairs; Special Sitrep -32. [accessed 2005 Jan 14]. Available at: http://www.tsunami@nic.in .

- 4.Gerrity TE, Flynn BW. Mental Health consequences of disasters. In: Noji EK, editor. Public Health Consequences of Disasters. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 101–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murthy RS. Psycho-social consequences. In: Parasuraman S, Unnikrishnan PV, editors. India Disasters Report: Towards a Policy Initiative. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 54–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bland SH, O’Leary ES, Farinaro E, Jossa F, Trevisan M. Long-term Psychological effects of natural disasters. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:18–24. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Effects of Traumatic Stress in a Disaster Situation: A National Center for PTSD Fact Sheet. [accessed 2005 Mar 2]. Available from: http://www.ncptsd.va.gov .

- 8.Kar GC. Disaster and Mental Health. Presidential Address. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:3–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norris FH. Psychosocial consequences of natural disasters in developing countries: What does past research tell us about the potential effects of the 2004 Tsunami. National Center for PTSD Fact Sheet. [accessed on 2005 Mar 25]. Available from: http://www.ncptsd.va.gov/

- 10.Freedy JR, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG. Conceptual framework for evaluating disaster impact: Implications for clinical intervention. In: Austin LS, editor. Responding to disaster: A guide for mental health professionals. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1992. pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomat Med. 1979;41:209–18. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale-revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2) India: Mumbai 1998-99. 2000:41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, Mallonee S, McMillen C, Spitznagel EL, et al. Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City Bombing. JAMA. 1999;282:755–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.8.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basoglu M, Salcioglu E, Livanou M. Traumatic stress responses in earthquake survivors in Turkey. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15:269–76. doi: 10.1023/A:1016241826589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donald RM. How Women were affected by the tsunami: A perspect. Oxfam. PloS Med. 2005;2:e178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar MS, Murhekar MV, Hutin Y, Subramanian T, Ramachandran V, Gupte MD. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in a coastal fishing village in Tamil Nadu, India, after the December 2004 Tsunami. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:99–101. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frankenberg E, Freidman J, Gillespie T, Ingwersen N, Pynoos R, Rifai U, et al. Mental Health in Sumatra after the Tsunami. Am J of Public Health. 2008;98:1671–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armenian HK, Morikawa M, Melkonian AK, Hovanesian AP, Haroutunian N, Saigh PA, et al. Loss as a determinant of PTSD in a cohort of adult survivors of the 1988 earthquake in Armenia: Implications for policy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:58–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geonjian AK, Najarian LM, Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Manoukian G, Tavosian A, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in elderly and younger adults after the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:895–901. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Gao L, Shinfuku N, Zhang H, Zhao C, Shen Y. Longitudinal study of earthquake related PTSD in a randomly selected community sample in North China. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1260–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foa EB, Stein DJ, Stein DJ, McFarlene AC. Symptomatology and psychopathology of mental health problems after disaster. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 2):15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao S. Managing Impact of natural disasters: Some mental health issues. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:289–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kar N, Jagadisha, Sharma, Murali, Mehrotra S. Mental health consequences of the trauma of super-cyclone 1999 in Orissa. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:228–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griensven F, Chakkraband S, Theinkrua W, Pengjuntr W, Cardozo BL, Tantipiwatanaskul P, et al. Mental health problems among adults in Tsunami affected areas in southern Thailand. JAMA. 2006;296:537–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geongian AK, Najarian LM, Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Manoukian G, Tavosian A, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in elderly and younger adults after the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:895–901. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acharya N. Double victims of Latur earthquake. Indian J Soc Work. 2000;61:558–64. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker SM. Psychosocial care for women survivors of the tsunami disaster in India. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:654–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]