Abstract

Objective To measure whether the benefits of a single education and self management structured programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus are sustained at three years.

Design Three year follow-up of a multicentre cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care, with randomisation at practice level.

Setting 207 general practices in 13 primary care sites in the United Kingdom.

Participants 731 of the 824 participants included in the original trial were eligible for follow-up. Biomedical data were collected on 604 (82.6%) and questionnaire data on 513 (70.1%) participants.

Intervention A structured group education programme for six hours delivered in the community by two trained healthcare professional educators compared with usual care.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels. The secondary outcomes were blood pressure, weight, blood lipid levels, smoking status, physical activity, quality of life, beliefs about illness, depression, emotional impact of diabetes, and drug use at three years.

Results HbA1c levels at three years had decreased in both groups. After adjusting for baseline and cluster the difference was not significant (difference −0.02, 95% confidence interval −0.22 to 0.17). The groups did not differ for the other biomedical and lifestyle outcomes and drug use. The significant benefits in the intervention group across four out of five health beliefs seen at 12 months were sustained at three years (P<0.01). Depression scores and quality of life did not differ at three years.

Conclusion A single programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus showed no difference in biomedical or lifestyle outcomes at three years although there were sustained improvements in some illness beliefs.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN17844016.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a serious, progressive condition presenting with chronic hyperglycaemia, and its prevalence is increasing globally. In the short term, type 2 diabetes may lead to symptoms and debility and in the long term to serious complications, including blindness, renal failure, and amputation.1 Furthermore, three quarters of people with type 2 diabetes will die from cardiovascular disease.2 Traditionally, treatment for the condition has centred on drug interventions to stabilise hyperglycaemia and to manage cardiovascular risk factors, including blood pressure and lipids, to prevent associated symptoms and reduce the risk of vascular complications over time.3 Long term follow-up data from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study has shown that despite early successes, metabolic control progressively worsens with time, warranting exploration of alternative approaches for long term management of type 2 diabetes.4

Anyone with diabetes, including type 2 diabetes, has to make multiple daily choices about the management of their condition, such as appropriate dietary intake, physical activity, and adherence to drugs, often with minimal input from a healthcare professional.5 In recent years, programmes to educate people about self management have become the focus of attention among healthcare professionals and are advocated for people with type 2 diabetes as a means to acquire the skills necessary for active responsibility in the day to day self management of their condition.6 7 8 9 10 In addition, it has been suggested that education on self management may play a pivotal role in tackling beliefs about health and so improve metabolic control, concordance with drug decisions, risk factors, and quality of life.11 12 13

Globally, self management education is recognised as an important component for the management of type 2 diabetes; the American Diabetes Association states that it should be offered from the point of diagnosis.14 Similarly in the United Kingdom, where this study was undertaken, the 2008 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines for diabetes,15 national service framework for diabetes,9 and the 2011 quality standards from NICE, advocate the provision of self management education from diagnosis. The diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) intervention was one of the first programmes to meet the quality criteria for education programmes that are listed by the Department of Health and Diabetes UK Patient Working Group, which are consistent with the American Diabetes Association criteria.16 DESMOND is currently available in 103 health organisations across the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Gibraltar, and Australia, with 735 trained educators.

The study design, baseline characteristics of the participants, and changes in biomedical, lifestyle, and psychosocial measures at 12 months have been reported and showed improvements in weight, smoking cessation, illness beliefs, depression, and cardiovascular risk scores in participants who received the intervention compared with standard care.17 18 19 The programme has recently been shown to be cost effective.20

Few self management education programmes have reported long term effects of the intervention.21 Self management education programmes, such as DESMOND, may incur benefits to participants in the longer term, as participants who successfully acquire, embrace, and maintain the necessary skills for the self management of their condition may gain further benefits in terms of biomedical and psychosocial outcomes. We evaluated whether the impact of a single structured self management education programme (DESMOND) with six hours contact time within six weeks of diagnosis was sustained at three years.

Methods

The study methods, intervention, and outcomes at 12 months have been reported in detail previously.18 19 Briefly, a robust cluster randomised controlled trial was undertaken to assess the effectiveness of a structured self management education programme that took place in 13 primary care sites (207 practices) across England and Scotland. Randomisation took place at the level of the general practice to minimise contamination between participants, with stratification by training status and type of contract with the primary care organisation (General Medical Services or Personal Medical Services). Randomisation was undertaken independently at the University of Sheffield using Random Log. At each site a local coordinator oversaw the trial, recruited and trained practices, and maintained contact with practice staff. Performance of the sites and local coordinators was monitored regularly, with each site receiving a visit before the trial and a minimum of one monitoring visit per year. Practice staff sent biomedical data to the local coordinator for forwarding to the central coordinating centre.

Individuals were referred within six weeks of diagnosis to the study, with those in the intervention arm attending a structured education programme within 12 weeks of diagnosis. Participants in the original trial were excluded if they were aged less than 18 years, had severe and enduring mental health problems, were not primarily responsible for their own care, were unable to participate in a group programme (for example, were housebound or unable to communicate in English), or were participating in another research study. Recruitment took place between October 2004 and January 2006. Everyone who consented to join the original trial was eligible for follow-up at three years unless they had withdrawn during the trial or their practice informed us they were no longer at the practice or that it would be inappropriate to contact them (for example, owing to serious illness).

The intervention

The structured group education programme is based on a series of psychological theories of learning: Leventhal’s common sense theory,22 dual process theory,23 and social learning theory.24 The philosophy of the programme was founded on patient empowerment, as evidenced in published work.25 26

The intervention was devised as a group education programme, with a written curriculum suitable for a wide range of participants, delivered in a community setting, and integrated into routine care. Registered healthcare professionals received formal training to deliver the programme and were supported by a quality assurance component of internal and external assessment to ensure consistency of delivery. The programme was six hours long, deliverable in either one full day or two half day equivalents, and facilitated by two educators. Learning was elicited rather than taught, with the behaviour of the educators promoting a non-didactic approach. Most of the curriculum focused on lifestyle factors, such as food choices, physical activity, and cardiovascular risk factors. The programme activates participants to consider their own personal risk factors and, in keeping with theories of self efficacy, to choose a specific achievable goal to work on.24 The broad content of the curriculum and an overview of the quality assurance have been reported elsewhere.17

The methods followed for the present study were similar to those of the original trial. Participants were sent a postal questionnaire two weeks before the three year follow-up date. A reminder letter and further copy of the questionnaire were sent if the original questionnaire was not returned within three weeks. Practices were contacted at the same time and asked to forward the most recent biomedical measurements on the participants to see if differences to biomedical and psychosocial outcomes could be sustained at three years. Given the nature of the original intervention, the study was not blinded.

Outcome variables

Follow-up took place at four, eight, and 12 months and at three years, with biomedical, lifestyle, and psychosocial data being collected. Biomedical outcomes included glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level, blood pressure, levels of total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, low density cholesterol, and triglycerides, body weight, and waist circumference. Questionnaires (described in detail in18) included lifestyle questions on smoking status and physical activity, as well as quality of life and health related quality of life. We used an illness perceptions questionnaire27 to assess people’s perception that they understood their diabetes (coherence), perception of the duration of their illness (timeline), and perception of their ability to affect the course of their diabetes (personal control). In addition, we collected data on perceived seriousness and perceived impact of diabetes, emotional distress specific to diabetes using the problem areas in diabetes questionnaire,28 and depression.

Statistical analysis

For the original study the sample size was calculated on the basis of a standard deviation of HbA1c levels of 2%, an intraclass correlation of 0.05, and an average of 18 participants per practice. We calculated that we needed 315 participants per study arm to detect a clinically relevant difference in HbA1c levels of 1% at 12 months, with 90% power at the 5% significance level. Assuming a failure to consent rate of 20% (not eligible as well as declining to participate) and a dropout rate of 20%, 1000 participants (500 in each arm) needed to be referred.

Statistical analysis was carried out by intention to treat. Continuous variables are given as means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges and categorical variables as counts and percentages. To adjust for cluster we used robust generalised estimating equations with an exchangeable correlation structure. For binary outcomes we used a logit link with a binomial distribution for the outcome, and for continuous outcomes we used an identity link with a normal distribution. Adjustment for baseline value was made in all models (apart from the problem areas in diabetes score, which was not recorded at baseline as it was inappropriate for participants with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes). We assumed data to be missing completely at random and they were not replaced or imputed. Statistical significance was set at 5%, with no adjustment for multiple testing, although all P values were interpreted in line with the pattern of the results. All analysis was carried out in Stata (version 10.0).

Results

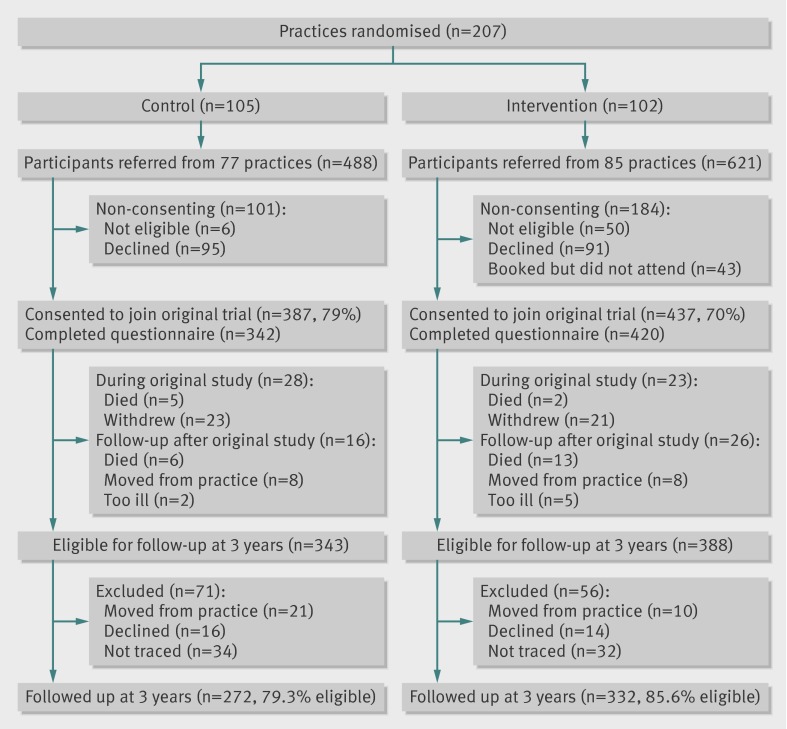

Of the 824 individuals who consented to take part from the 207 general practices (387 control and 437 intervention) to the original trial, 743 (90.2%) were eligible for follow-up at three years. Of those not eligible, 26 died, 44 withdrew from the study, 16 moved practice, and seven were identified by practices as being too ill to follow up (figure). Biomedical data were collected on 604 (82.6%) of those eligible. Biomedical data was provided for 332 (85.6%) participants in the intervention arm and 272 (79.3%) in the control arm. Postal questionnaires were completed by 536 (73.1%) of those eligible. The level of return for the questionnaires was 299 (75.3%) for the intervention arm and 237 (68.5%) for the control arm. Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics of those who were and were not successfully followed up at three years. The group on whom three year follow-up data were obtained were older (P=0.01) and had a lower weight (P=0.004), body mass index (P=0.004), waist circumference (P<0.001), and depression score (P<0.001). When taking into account the treatment group, no interactions between responders and group were found for these outcomes.

Flow of participants through trial

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants with type 2 diabetes who were or were not followed up at three years. Values are means (standard deviations) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Not followed up at 3 years | Followed up at 3 years | P values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=220) | Intervention (n=105) | Control (n=115) | Total (n=604) | Intervention (n=332) | Control (n=272) | Not followed up v responders | Group interaction | |

| Age (years) | 57.6 (12.5) | 57.8 (12.9) | 57.5 (12.2) | 60.1 (11.8) | 59.4 (11.6) | 61.01 (12.1) | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| No (%) female | 101 (45.9) | 53 (50.5) | 48 (41.7) | 271 (44.9) | 151 (45.5) | 120 (44.1) | 0.79 | 0.35 |

| No (%) white European ethnicity | 182 (95.3) | 91 (95.8) | 91 (94.8) | 543 (97.1) | 307 (97.2) | 236 (97.1) | 0.22 | 0.81 |

| No (%) smokers | 34 (17.9) | 15 (16.0) | 19 (19.8) | 76 (13.6) | 42 (13.3) | 34 (14.1) | 0.15 | 0.68 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.3 (2.2) | 8.3 (2.2) | 8.1 (2.1) | 8.0 (2.1) | 8.3 (2.2) | 7.7 (1.9) | 0.31 | 0.27 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.4 (1.3) | 5.3 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.3 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.4) | 5.3 (1.2) | 0.58 | 0.12 |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.3) | 0.86 | 0.29 |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.0) | 3.5 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.0) | 0.55 | 0.03 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 2.6 (2.0) | 2.3 (1.8) | 3.0 (2.1) | 2.5 (2.1) | 2.7 (2.6) | 2.3 (1.4) | 0.49 | 0.002 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 140.3 (19.0) | 142.1 (19.5) | 138.6 (18.3) | 140.6 (17.1) | 140.7 (18.1) | 140.5 (15.9) | 0.81 | 0.23 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 82.3 (11.0) | 83.0 (10.7) | 81.6 (10.4) | 81.6 (10.4) | 82.3 (10.5) | 80.7 (10.2) | 0.39 | 0.98 |

| Body weight (kg) | 95.0 (22.1) | 93.7 (21.6) | 96.2 (22.5) | 90.5 (18.6) | 91.2 (18.3) | 89.7 (18.9) | 0.004 | 0.2 |

| Body mass index | 33.4 (6.7) | 33.0 (6.4) | 33.8 (7.0) | 32.0 (6.0) | 32.1 (5.9) | 31.8 (6.1) | 0.004 | 0.3 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 108.4 (14.6) | 108.5 (14.8) | 108.3 (14.5) | 105.3 (13.9) | 104.8 (14.6) | 105.9 (13.1) | 0.008 | 0.59 |

| Illness beliefs: | ||||||||

| Coherence score | 14.5 (4.2) | 14.8 (4.3) | 14.2 (4.3) | 15.0 (4.2) | 14.5 (4.1) | 15.8 (4.2) | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| Timeline score | 19.7 (3.7) | 20.2 (3.6) | 19.3 (3.8) | 20.1 (4.0) | 20.4 (3.9) | 19.6 (4.1) | 0.31 | 0.94 |

| Responsibility score | 23.9 (3.5) | 23.8 (3.0) | 24.0 (4.0) | 24.4 (3.2) | 24.4 (3.4) | 24.5 (3.0) | 0.06 | 0.93 |

| Seriousness score | 16.6 (2.4) | 16.7 (2.4) | 16.5 (2.3) | 16.5 (2.7) | 16.4 (2.7) | 16.6 (2.7) | 0.53 | 0.99 |

| Impact score | 14.8 (3.9) | 14.8 (3.0) | 14.8 (4.2) | 14.2 (3.4) | 14.1 (3.4) | 14.4 (3.7) | 0.05 | 0.75 |

| HADS depression score | 4.4 (3.7) | 4.1 (3.4) | 4.6 (4.0) | 3.3 (3.3) | 3.2 (3.1) | 3.4 (3.1) | <0.001 | 0.59 |

HADS=hospital anxiety and depression scale.

Biomedical outcomes

Table 2 shows the mean (95% confidence interval) change in biomedical outcomes in the study groups at three years. Across all biomedical outcomes improvements were seen in both groups, with no significant differences between groups at three years. The primary outcome, HbA1c level, did not differ significantly between the groups. The observed difference between intervention groups was −0.02 (95% confidence interval −0.22 to 0.17) after adjusting for baseline and clustering. The intraclass correlation for HbA1c at three years was 0.02 (95% confidence interval 0.00 to 0.08).

Table 2.

Changes in biomedical outcomes at three years

| Variables | No (%) of participants | Change (95% CI) | Model summary, coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | ||||

| HbA1c (%) | 585 (96.9) | −1.32 (−1.57 to −1.06) | −0.81 (−1.02 to −0.50) | −0.02 (−0.22 to 0.17) | 0.81 |

| Body weight (kg) | 592 (98.0) | −1.75 (−2.48 to −1.03) | −1.44 (−2.42 to −0.45) | −0.20 (−1.33 to 0.93) | 0.73 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 589 (97.5) | −1.20 (−1.35 to −1.05) | −1.07 (−1.22 to −0.91) | −0.03 (−0.19 to 0.12) | 0.68 |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 367 (60.8) | 0.01 (0.002 to 0.11) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.11) | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.09) | 0.51 |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 248 (41.1) | −0.92 (−1.12 to −0.72) | −0.84 (−1.05 to −0.63) | −0.08 (−0.28 to 0.13) | 0.47 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 490 (81.1) | −0.37 (−0.94 to −0.40) | −0.37 (−0.56 to −0.18) | −0.06 (−0.27 to 0.15) | 0.56 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 595 (98.5) | −7.88 (−10.15 to −5.62) | −6.58 (−8.65 to −4.52) | −1.07 (−3.42 to 1.28) | 0.37 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 595 (98.5) | −6.03 (−7.27 to −4.79) | −4.45 (−5.81 to −3.10) | −0.68 (−2.20 to 0.83) | 0.38 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 264 (43.7) | −1.03 (−2.43 to 0.37) | −0.96 (−3.62 to 1.70) | −0.38 (−4.43 to 3.66) | 0.85 |

| Body mass index | 586 (97.0) | −0.61 (−0.87 to −0.36) | −0.54 (−0.90 to −0.18) | −0.03 (−0.45 to 0.39) | 0.88 |

| UKPDS 10 year coronary heart disease risk | 322 (53.3) | −7.80 (−9.80 to −5.80) | −6.49 (−8.62 to −4.36) | −1.67 (−3.91 to 0.57) | 0.14 |

| UKPDS 10 year cardiovascular disease risk | 322 (53.3) | −5.91 (−8.10 to −3.72) | −4.42 (−6.89 to −1.95) | −1.89 (−5.17 to 1.39) | 0.26 |

UKPDS=United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study.

At three years, no statistical difference was seen in 10 year coronary heart disease or cardiovascular risk (United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study) between the intervention and control groups, with reductions observed in both groups (table 2).

Lifestyle outcomes

A significant difference in the proportion of non-smokers was seen in favour of the intervention arm at 12 months. This difference was not maintained at three years. No difference in the level of physical activity between the groups was seen at three years (P=0.58, table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of lifestyle outcomes at three years

| Variables | No (%) of participants | Intervention group | Control group | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-smoker | 457 (85.3) | 253 (91.0) | 183 (86.7) | 2.07 (0.76 to 5.66) | 0.16 |

| Any level of physical activity | 419 (78.2) | 236 (92.9) | 197 (91.2) | 1.22 (0.60 to 2.48) | 0.58 |

Illness beliefs, depression, problem areas in diabetes, and quality of life

Table 4 shows the results for the psychosocial measures. After adjustment for baseline value and cluster, four of the five illness belief scores (coherence, timeline, personal responsibility, and seriousness) differed significantly at three years. The intervention participants had higher scores for all, showing that they had a greater understanding of their illness and its seriousness and a better perception of the duration of their diabetes and of their ability to affect the course of their disease. No difference was seen between the groups for depression, problem areas in diabetes scores, and quality of life at three years (see supplementary file on bmj.com for quality of life data).

Table 4.

Scores for illness beliefs and hospital anxiety and depression scale

| Variables | No (%) of participants | Median (interquartile range) | Model summary, coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | ||||

| Illness coherence | 409 (76.3) | 20 (16-20) | 19 (15-20) | 0.93 (0.20 to 1.65) | 0.01 |

| Timeline | 414 (77.2) | 22 (20-25) | 20 (19-25) | 0.87 (0.24 to 1.49) | 0.01 |

| Personal responsibility | 412 (76.9) | 24 (23-27) | 24 (23-26) | 0.49 (−0.004 to 0.99) | 0.005 |

| Impact | 413 (77.1) | 13 (12-15) | 13 (12-15) | 0.22 (−0.33 to 0.77) | 0.44 |

| Seriousness | 414 (77.2) | 17 (15-19) | 16 (15-18) | 0.77 (0.23 to 1.30) | 0.01 |

| Depression | 465 (86.8) | 2 (1-5) | 2 (1-6) | −0.29 (−0.74 to 0.15) | 0.19 |

| Problem areas in diabetes scale | 461 (86.0) | 10.0 (3.8-20.0) | 8.8 (2.5-21.3) | −0.69 (−3.45 to 2.07) | 0.63 |

Drugs

At three years the number of people taking oral antidiabetic agents as monotherapy or dual therapy or those taking insulin did not differ significantly between the groups (table 5).

Table 5.

Drugs used by participants with type 2 diabetes

| Drugs | Intervention group | Control group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antihypertensives | 235 (70.8) | 206 (76.9) | 0.09 |

| Lipid lowering | 266 (80.1) | 209 (78.0) | 0.52 |

| Antidepressants | 24 (8.9) | 18 (9.2) | 0.90 |

| Oral antidiabetics: | |||

| Monotherapy | 188 (56.6) | 107 (39.3) | 0.32 |

| Dual therapy | 59 (17.8) | 45 (16.5) | 0.69 |

| Insulin | 10 (3.0) | 7 (2.6) | 0.75 |

Discussion

After three years the impact of a single structured education intervention delivered to people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus was not sustained for biomedical and lifestyle outcomes, although some changes in illness beliefs were still apparent.

Previously we reported that compared with baseline at 12 months HbA1c levels decreased by −1.49% (95% confidence intervals −1.69% to −1.29%) in the intervention group and by −1.21% (−1.40% to −1.02%) in the control group.18 The present study showed a small increase in HbA1c levels from the 12 month data; however, overall the decreases in both the intervention group (−1.32%, −1.57% to −1.06%) and the control group (−0.81%, −1.02% to −0.59%) were sustained at three years.

Although this is reassuring compared with the long term follow-up results of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, which reported a 1% increase in HbA1c level over four years in a newly diagnosed cohort,4 this is not entirely unexpected in the context of the recent improvements to the management and quality of care of type 2 diabetes after the introduction of the quality outcomes framework.29 A pragmatic, cluster randomised study undertaken in primary care, ADDITION-Europe, was unable to detect cardiovascular benefit of multifactorial therapy compared with routine care in people with type 2 diabetes detected by screening. This is thought to be at least in part attributable to changes to national guidelines during the follow-up period of the trial, resulting in allocated treatments of the intervention and control group becoming more similar.30 The clear benefits of an intervention above routine care has become increasingly difficult to show in a setting where outcome measures are often successfully treated to target from diagnosis. However, other important aspects of diabetes management are not currently captured or incentivised by current targets, including self management skills and empowerment, which were evaluated in this study.29

A report of the best methods for evaluating diabetes education identified four key outcomes associated with optimal adjustment to living with diabetes, which comprised knowledge and understanding, self management, self determination, and psychological adjustment, two of which were assessed in this study.31 The significant improvements to four of the five illness beliefs were sustained at three years and indicate a greater understanding by the participants of their diabetes and of their ability to affect the course of their diabetes. Although participants from the intervention group believed their diabetes to be more serious and were more likely to agree that they would have diabetes for life, this had not caused them greater distress about their diabetes, as evidenced by responses to the problem areas in diabetes questionnaire. Further research is required to ascertain how to translate these into favourable biomedical outcomes in the longer term.

Since the launch of the DESMOND programme, numerous studies have aimed to improve self management in people with type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis assessing the impact of self management interventions in people with type 2 diabetes published before 2007 reported improvements to glycaemic control in people who received self management treatment, with a small advantage of an intervention with an educational approach.21 The results of the DESMOND intervention published in 2008 were not included in the meta-analysis. Of the studies included in the review, only eight reported follow-up results at greater than 12 months.

The DESMOND intervention for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes was always intended to be included within an ongoing model of education and clinical care, integrating life long learning, care planning, and treatment optimisation. However, a key aspect of the study design was to show at what point any benefits of intervention begin to diminish. Currently, our group are developing and implementing the DESMOND ongoing module to evaluate the long term effectiveness of an ongoing self management intervention in people with type 2 diabetes. The findings of these studies will help to determine the optimal contact time and frequency of education sessions required to sustain improvements to clinical outcomes through self management. The DESMOND intervention is likely to remain cost effective as the cost effectiveness analysis of the DESMOND intervention using 12 month data was based on the assumption that observed lifestyle changes and smoking cessation would not be sustained without an ongoing maintenance intervention.20 We have shown that delivery of the DESMOND intervention at diagnosis is beneficial for psychosocial outcomes. Although these benefits are important it remains uncertain at what stage, if ever, biomedical benefits emerge in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and whether in the longer term a relation between the two translates into more effective self management to maintain glycaemic control. Participants may need further education and ongoing support to successfully manage their condition and to achieve improvements to clinical outcomes and self management behaviours long term.

Comparison with other studies

Evidence of the long term impact of structured education interventions in people with diabetes is currently lacking. The dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) intervention delivered as a single structured education programme to a group of adults with type 1 diabetes showed clinically significant improvements to HbA1c levels without an increase in severe hypoglycaemia at two years.32 Quality of life and improvements to HbA1c levels were maintained at four years.33 The authors suggest that follow-up support for this population group may create additional benefits by helping people to identify routines to better integrate this regimen into their lives.

The expert patient education versus routine treatment (X-PERT) programme reported significant improvements to HbA1c level at 14 months (−0.6% v 0.1%) in a population with established type 2 diabetes, although long term results have not yet been reported.34 Participants of the X-PERT programme had a mean duration of 6.7 years, compared with our newly diagnosed cohort in whom additional benefits of an education programme were hard to show when medical outcomes were aggressively and successfully targeted. An additional dissimilarity is that the X-PERT intervention was delivered over six sessions with participants receiving double the contact time as those of the DESMOND intervention, which may confer additional benefits.

The rethink organisation to improve education and outcomes (ROMEO) intervention was delivered in a secondary care clinic setting in Italy as a continuous education programme. Long term outcomes at four years have reported favourable clinical, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in a cohort with established type 2 diabetes.35 The intervention comprised one hour education sessions delivered on a three monthly basis, whereas the DESMOND module was delivered as a single intervention involving six hours of contact time, with no further reinforcement of the messages delivered. The ROMEO intervention implies that an ongoing model of education and care can result in improvements to clinical outcomes. However, further research is required to ascertain whether these results are replicable out of the Italian secondary care clinical setting.

A self management intervention delivered in a primary care setting in Sweden showed an adjusted difference in HbA1c level of 1.37% (P<0.001) at five years between intervention and control groups.36 The intervention group received 10 group sessions, two hours long, over a period of nine months. The intervention did not have a curriculum or agenda, and whether the impressive study results can be replicated has yet to be determined.

As with all educational interventions, DESMOND is a complex intervention, which makes it difficult to ascertain the active components contributing to positive effects of the intervention.37 One aspect of the DESMOND intervention is goal setting, where the participant chooses one part of their care to work at. The relative success of this component, as with others, is currently unknown in the DESMOND intervention. A randomised controlled trial that evaluated the impact of goal setting in self management education in people with type 2 diabetes recently reported that at 12 months statistically significant favourable differences in HbA1c levels were seen in the intervention group.38

Strengths and limitations of the study

The original DESMOND trial has several strengths, which have been discussed at length previously.18 In brief, the trial had a robust cluster randomised design, with reasonably well matched participants in the control and intervention groups, and the study was successful in minimising contamination between practices. Importantly, the intervention was designed for consistent reproducibility of training and had a relatively low up-front training investment, enabling implementation across other sites. All educators participating in the intervention were fully trained and quality assured, ensuring generalisability of the findings in other DESMOND studies and out of the research setting.

Statistical analyses for this study were undertaken using intention to treat analysis, minimising bias in the reported findings. However, our study may have been underpowered to detect improvements in clinical outcomes and as a result some of our findings may be prone to type 2 error. Response rates of the study were higher than expected after three years of follow-up, with collection of biomedical data achieved by 83% of participants and questionnaire data by 70%, minimising missing data and the effect this may have had on the interpretation of the study results. This compares positively with other self management education interventions that obtained long term follow-up data from 63% to 85% of the original participants.33 35 36 Those who were followed up at three years were older, healthier, and less depressed at baseline than those who were not followed up. This selection bias should be considered when interpreting the results, although importantly there was no interaction with intervention group. Additionally, missing data on individuals may have less impact in a cluster randomised trial than in an individually randomised trial.

A weakness of our study was lack of power to find differences in hard end points and that significant differences in mortality or cardiovascular events were unlikely to be detected in this study. In reality, intervention studies that report decreases in cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in people with type 2 diabetes require longer follow-up.39 40 Studies designed with sufficient power to detect differences in these important outcomes will provide valuable information to shape the model of future diabetes care. A non-response bias was detected in this study, with responders being older, less overweight (according to body mass index and waist circumference), and reporting more depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

In a cohort of adults with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes a single, six hour structured programme in self management did not offer sustained benefits in biomedical outcome measures and lifestyle outcomes at three years, but some changes to illness beliefs were sustained. The results support a programme of an ongoing model of education, although the optimum interval and contact time needs further evaluation. However, we recognise that additional support through increased contact time and frequency may incur additional benefit through important improvements to biomedical outcomes, and further research to establish this is needed. Future studies need to incorporate a longer follow-up period to generate understanding of intervention effects over time.

What is already known on this topic

The diabetes national service framework and NICE quality standards promote structured education for all from diagnosis of diabetes

Until now no studies have evaluated the long term impact of attending an education intervention

What this study adds

Differences in biomedical and lifestyle outcomes at 12 months from a structured group education programme for patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes were not sustained at three years, although illness beliefs remained significant

The results support the model of an ongoing education programme, although the optimum interval and contact time needs further evaluation

We thank the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care—Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, and Rutland, and the Biomedical Research Unit.

Contributors: KK was the principal investigator of the three year follow-up study and drafted the paper. LG analysed the data and drafted the paper. TCS was involved in the conception of the DESMOND programme and reviewed the paper. MEC was the project manager of the 12 months DESMOND trial and reviewed the paper. KR collated the data. HD was senior researcher and collated data and drafted the paper. HF drafted the paper. MC was involved in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data. SH was involved in the conception of the DESMOND programme and reviewed the paper. MJD was the principal investigator for the DESMOND trial, designed the trial, and reviewed the paper.

Funding: This study was funded by a grant from Diabetes UK secured by a joint team from Leicester University and the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust. The writing of the report and the decision to submit the article for publication was entirely independent of the funder. The study funder had no input into the study design or analysis, nor the interpretation of data.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any company for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Huntingdon local research ethics committee and was carried out in accordance with the principles of the 1996 Helsinki declaration.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;344:e2333

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Quality of life data at three years

References

- 1.Massi-Benedetti M. The cost of diabetes type ii in Europe: the CODE-2 study. Diabetologia 2002;45:S1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tapp R, Shaw J, Zimmet P, eds. Complications of diabetes. In: International diabetes federation, ed. Diabetes atlas. 2nd ed.International Diabetes Federation, 2003.

- 3.Norris S, Nichols P, Caspersen C, Glasgow R, Engelgau M, Jack L. Increasing diabetes self management education in community settings. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2002;22:39-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998;352:837-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarvis J, Skinner T, Carey M, Davies M. How can structured self-management patient education improve outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes? Diabet Obes Metab 2010;12:12-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutten G. Diabetes patient education: time for a new era. Diabet Med 2005;22:671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of patient education models for diabetes (technology appraisal 60). NICE, 2003.

- 8.Department of Health. National service framework for diabetes: delivery strategy. Department of Health, 2002.

- 9.Department of Health. National service framework for diabetes: standards. Department of Health, 2001.

- 10.Audit Commission. Testing times. A review of diabetes services in England and Wales. Belmont Press, 2000.

- 11.Norris S, Lau J, Smith S, Schmid C, Engelgau M. Self management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1159-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skinner T, Cradock S, Arundel F, Graham W. Four theories and a philosophy: self management education for individuals newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum 2003;16:75-80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorig K. Partnerships between expert patients and physicians. Lancet 2002;359:814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association. Position statement: standards in diabetes care. Diabetes Care 2010;33:S11-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guidance 87. Type 2 diabetes: the management of type 2 diabetes (partial update). NICE, 2009.

- 16.Department of Health, Diabetes UK. Structured patient education in diabetes: report from the Patient Education Working Group. Department of Health, 2005.

- 17.Skinner T, Carey M, Cradock S, Daly H, Davies M, Doherty Y, et al. Diabetes education and self-management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND): process modelling of pilot study. Patient Educ Couns 2006;64:369-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies M, Heller S, Skinner T, Campbell M, Carey M, Cradock S, et al, on behalf of the Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed Collaborative. Effectiveness of the diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;336:491-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khunti K, Skinner T, Heller S, Carey M, Dallosso H, Davies M. Biomedical, lifestyle and psychosocial characteristics of people newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: baseline data from the DESMOND randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med 2008;25:1454-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillett M, Dallasso H, Dixon S, Brennan A, Carey M, Campbell M, et al. Delivering the diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minet L, Moller S, Vach W, Wagner L, Henrisken J. Mediating the effect of self-care management intervention in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of 47 randomised controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns 2010;80:29-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common-sense representation of illness danger. Contributions to medical psychology. Pergamon, 1980.

- 23.Chaiken S, Wood W, Eagly A. Principles of persuasion. In: Higgih EKA, ed. Social psychology: handbook of basic principles. Guilford Press, 1996.

- 24.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson R, Funnell M, Butler P, Arnold M, Fitzgerald J, Feste C. Patient empowerment. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 1995;18:943-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson R. Patient empowerment and the traditional medical model. A case of irreconcilable differences? Diabetes Care 1995;18:412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skinner T, Howells L, Greene S, Edgar K, McEvilly A, Johansson A. Development, reliability and validity of the diabetes illness representations questionnaire: four studies with adolescents. Diabet Med 2003;20:283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welch G, Jacobson A, Polonsky W. The problem areas in diabetes scale. An evaluation of its clinical utility. Diabetes Care 1997;20:760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alshamsan R, Millett C, Majeed A, Khunti K. Has pay for performance improved the management of diabetes in the United Kingdom? Primary Care Diabetes 2010;4:73-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin SJ, Borch-Johnsen K, Davies MJ, Khunti K, Rutten GEHM, Sandbæk A, et al. Effect of early intensive multifactorial therapy on 5-year cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes detected by screening (ADDITION-Europe): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2011;378:156-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egenmann C, Colagiuri R. Outcomes and indicators for diabetes education—a national consensus position. Diabetes Australia, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.The DAFNE Study Group. Training in flexible, intensive insulin management to enable dietary freedom in people with type 1 diabetes: dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002;325:746-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speight J, Amiel S, Bradley C, Heller S, Oliver L, Roberts S, et al. Long-term biomedical and psychosocial outcomes following DAFNE (Dose Adjustment for Normal Eating) structured education to promote intensive insulin therapy in adults with sub-optimally controlled type 1 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract 2010;89:22-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deakin T, Cade J, Williams R, Greenwood D. Structured patient education: the Diabetes X PERT Programme makes a difference. Diabet Med 2006;23:944-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trento M, Gamba S, Gentile L, Grassi G, Miselli V, Morone G, et al. Rethink Organisation to iMprove Education and Outcomes (ROMEO): a multicentre randomised trial of lifestyle intervention by group care to manage type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:745-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hornsten A, Stenlund H, Lundman B, Sandstom H. Improvements in HbA1c remain after 5 years—a follow up of an educational intervention focusing on patients’ personal understandings of type 2 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract 2008;81:50-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craig C, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidelines. BMJ 2008;337:1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naik A, Palmer N, Peters N, Street R, Rao R, Suarez-Almazor M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of goal setting in diabetes mellitus group clinics. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:453-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaede P, Lunde-Andersen H, Parving H-H, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:580-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holman R, Paul S, Bethel M, Matthews D, Neil H. 10-year follow-up of intensive blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1577-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quality of life data at three years