Background: GRKs phosphorylate activated GPCRs to terminate signaling.

Results: Disrupting residues required for GPCR phosphorylation and Gβγ and phospholipid binding eliminated Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function.

Conclusion: These interactions are required for Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo and support a recently proposed universal model for GRK activation.

Significance: This is the first study to systematically determine the residues required for GRK function in live animals.

Keywords: C. elegans, Cell Signaling, Chemotaxis, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), G Proteins, Receptor Serine Threonine Kinase, Signal Transduction, GRK, Chemosensation, Kinase

Abstract

G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) are key regulators of signal transduction that specifically phosphorylate activated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to terminate signaling. Biochemical and crystallographic studies have provided great insight into mammalian GRK2/3 interactions and structure. However, despite extensive in vitro characterization, little is known about the in vivo contribution of these described GRK structural domains and interactions to proper GRK function in signal regulation. We took advantage of the disrupted chemosensory behavior characteristic of Caenorhabditis elegans grk-2 mutants to discern the interactions required for proper in vivo Ce-GRK-2 function. Informed by mammalian crystallographic and biochemical data, we introduced amino acid substitutions into the Ce-grk-2 coding sequence that are predicted to selectively disrupt GPCR phosphorylation, Gαq/11 binding, Gβγ binding, or phospholipid binding. Changing the most amino-terminal residues, which have been shown in mammalian systems to be required specifically for GPCR phosphorylation but not phosphorylation of alternative substrates or recruitment to activated GPCRs, eliminated the ability of Ce-GRK-2 to restore chemosensory signaling. Disrupting interaction between the predicted Ce-GRK-2 amino-terminal α-helix and kinase domain, posited to stabilize GRKs in their active ATP- and GPCR-bound conformation, also eliminated Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function. Finally, although changing residues within the RH domain, predicted to disrupt interaction with Gαq/11, did not affect Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function, disruption of the predicted PH domain-mediated interactions with Gβγ and phospholipids revealed that both contribute to Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo. Combined, we have demonstrated functional roles for broadly conserved GRK2/3 structural domains in the in vivo regulation of organismal behavior.

Introduction

Caenorhabditis elegans gather chemical information about their surrounding environment primarily through G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)2 expressed by chemosensory neurons (1, 2). Animals move toward odorants that indicate a food source and away from chemicals that indicate a harmful or toxic environment. For example, the polymodal ASH sensory neurons detect a range of aversive stimuli, including olfactory (e.g. octanol) and gustatory (e.g. quinine) compounds, which animals avoid by rapidly initiating backward locomotion upon stimulus detection (2–4). Such behavioral responses are determined by both the cellular expression patterns of individual GPCRs and the invariant C. elegans neural circuitry (5, 6). Signaling components are highly conserved from yeast to mammals, and experiments from many systems have led to the following model for GPCR signal transduction (7–9). Signaling is initiated when an agonist (e.g. an odorant molecule) binds to the receptor. This interaction induces a conformational change in the receptor that causes the Gα subunit of the associated heterotrimeric G protein to exchange GDP for GTP and separate from the Gβ and Gγ subunits (Gβγ), thus becoming activated. The dissociated Gα and Gβγ subunits can then activate distinct signaling effectors, which themselves regulate the intracellular concentration of second messenger molecules that mediate the cellular response to the bound agonist.

G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) are serine/threonine kinases that specifically phosphorylate activated (agonist-bound) GPCRs to terminate signaling. There are seven mammalian GRKs, divided into three subfamilies (GRK1/7, GRK2/3, and GRK4/5/6) based on differences in structure and regulation (10, 11). Members of the GRK2/3 family of receptor kinases have an amino-terminal α-helix (αN) that stabilizes interaction with ligand-bound GPCRs, a regulator of G protein signaling homology (RH) domain that binds activated Gαq/11, and a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain that mediates membrane localization via Gβγ and phospholipid interactions (12–15). Although these GRK interactions have been defined and characterized biochemically, the physiological significance of each, in the context of a whole living organism, remains unknown.

Mammalian GRK2 and GRK3 are both ubiquitously expressed, but GRK3 is present at much higher levels in mouse olfactory epithelia (16–18). Although GRK2−/− homozygous knock-out mice are embryonic lethal because of cardiac failure, GRK2+/− heterozygous mice show enhanced cardiac contractility in response to isoproterenol (19, 20). This hypersensitivity is consistent with the classical role of GRKs in receptor desensitization. GRK3 knock-out mice are viable but have defects in olfactory signal transduction (17, 21). In olfactory epithelia isolated from wild-type animals, odorant stimulation causes a transient increase in cAMP levels that quickly returns to basal levels because of desensitization by GRK3 (17, 22, 23). However, olfactory epithelia isolated from GRK3 knock-out mice also showed a significantly reduced production of cAMP in response to odorants, in addition to a lack of desensitization (21). These data suggest that, although a loss of GRK function often leads to increased signaling and hypersensitivity in the absence of the negative regulator, there are unique situations in which loss of a particular GRK can lead to decreased signaling.

C. elegans have single orthologs of the GRK2/3 and GRK4/5/6 families, Ce-GRK-2 and Ce-GRK-1, respectively. Animals lacking Ce-GRK-2 function are not hypersensitive to chemosensory stimuli because of increased sensory signaling. Instead, a loss of Ce-GRK-2 function in adult sensory neurons broadly disrupts chemosensation (24). Although Ce-GRK-2 is expressed throughout the C. elegans nervous system, transgenic expression of Ce-GRK-2 in the bilaterally symmetric pair of ASH sensory neurons is sufficient to restore ASH-mediated aversive behavior (24). Furthermore, Ce-grk-2 animals show a decrease in stimulus-evoked calcium signaling in the ASH sensory neurons (24). Accordingly, when the chemosensory Gα ODR-3 (Gαi/o) was overexpressed to increase sensory signaling, it significantly restored the response of Ce-grk-2 mutant animals to the ASH-detected odorant octanol (24). Combined, a loss of Ce-GRK-2 function leads to decreased signaling in C. elegans sensory neurons, similar to the loss of mammalian GRK3 in olfactory epithelia (21, 24). Thus, behavioral analysis of C. elegans grk-2 mutant animals provides a unique opportunity to ask whether biochemically defined GRK2/3 interactions are required for function and cell signaling in vivo.

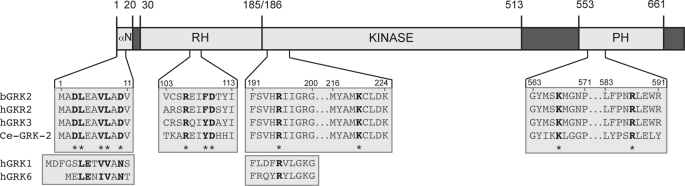

Because each of the key functional domains of mammalian GRK2/3 are conserved in Ce-GRK-2 (Fig. 1), we introduced amino acid substitutions into the Ce-grk-2 coding sequence that are predicted to selectively disrupt specific interactions and tested each for its ability to restore chemosensory behavior in animals lacking endogenous Ce-GRK-2 function. We found that changing the most amino-terminal residues, which have been shown in mammalian systems to be required specifically for effective GPCR phosphorylation but not phosphorylation of alternative substrates or recruitment to activated GPCRs (25, 26), eliminated the ability of Ce-GRK-2 to restore ASH-mediated chemosensory behaviors. In addition, disrupting interaction between the predicted Ce-GRK-2 amino-terminal α-helix and kinase domain, which likely stabilizes GRKs in the active, ATP- and GPCR-bound conformation (12, 13), also eliminated Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function. Finally, whereas changing residues within the RH domain, predicted to disrupt interaction with Gαq/11 (14, 27), did not diminish Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function, disruption of the predicted PH domain-mediated interactions with Gβγ and phospholipids (15) revealed that both contribute to Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo. Combined, our data suggest that the primary role of Ce-GRK-2 in chemosensory signal regulation is phosphorylation of putative chemosensory receptors to attenuate signaling. Our results reveal the key interactions required for Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo and support a recently proposed universal model for GRK activation wherein interaction between the GRK amino-terminal tail and small kinase lobe creates a GPCR docking site that, in concert with receptor binding, allosterically stabilizes the active conformation of the enzyme, stimulating efficient GPCR phosphorylation (12, 13, 28).

FIGURE 1.

Conserved structural domains in Ce-GRK-2. The predicted domain structures of bovine GRK2 (bGRK2), human GRK2 (hGRK2), human GRK3 (hGRK3), and C. elegans GRK-2 (Ce-GRK-2) are shown. Each of the biochemically defined/characterized domains of hGRK2/3 is conserved in Ce-GRK-2. Some key residues are also conserved in the GRK1 and GRK6 families, as shown by human GRK1 (hGRK1) and human GRK6 (hGRK6). Conserved amino acids targeted by site-directed mutagenesis in Ce-GRK-2 are shown in bold in the top boxes and indicated by asterisks. Amino acid position numbers refer to bGRK2. Residues 513–547 also form part of the RH domain (not shown) (41).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains

C. elegans strains were maintained under standard conditions (29). Strains used in this study include N2 Bristol wild-type and FG7 Ce-grk-2(gk268), which is outcrossed eight times to N2. gk268 is a deletion allele that removes 608 nucleotides of the 5′-untranslated region and the first three exons of Ce-grk-2 coding sequence (930 additional nucleotides); it is a predicted Ce-grk-2 null, and animals are phenotypically identical to the previously characterized Ce-grk-2(rt97) severe loss-of-function animals (24).

Plasmid Construction

Amino acid changes were incorporated into Ce-GRK-2 using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All of the constructs were sequenced following site-directed mutagenesis. The mutated Ce-grk-2 cDNAs were subcloned behind the ∼3-kb upstream promoter region of Ce-grk-2 (24). See the supplemental data for details and a complete list of plasmids.

Transgenic Strains

Germ line transformations were performed as previously described (30). All of the Ce-grk-2 constructs were injected along with 50 ng/μl of pJM67 elt-2::GFP (31) plus pBluescript (+KS) (Stratagene) to bring the final DNA concentration to 100 ng/μl. A complete list of transgenic strains is available upon request.

C. elegans Behavioral Assays

Well fed young adults were used for analysis. Behavioral assays were performed as previously described (32) on at least 3 separate days in parallel with controls. Briefly, the response to octanol was scored as the amount of time it took an animal to initiate backward locomotion after an octanol-dipped hair was placed in front of a forward moving animal (2, 33). Octanol avoidance assays were stopped at 20 s. Avoidance of the soluble tastant quinine was scored as the percentage of forward moving animals that initiated backward locomotion within 4 s of entering a drop of quinine placed on the agar plate (24, 34). For both assays, the animals were tested 10–20 min after transfer to nematode growth medium (NGM) plates lacking bacteria (“off food”). The data are presented as the standard errors of the mean, and the Student's two-tailed t test was used for statistical analysis.

Western Blotting

For each lane, 150 adult animals were washed three times in M9 (35) + 0.02% Tween 20 and incubated on ice for 1 h. The animals were boiled for 20 min in SDS-PAGE sample buffer + 100 mm DTT. Samples were run on 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Following blocking, the membranes were cut horizontally to allow for separate Western analysis of Ce-GRK-2 (∼80 kDa) and α-tubulin (∼55 kDa) from the same protein samples. Monoclonal primary antibodies anti-GRK2/3 (Millipore; clone C5/1.1) and anti-α-tubulin (Sigma; clone DM1A) were used at 1:2000 and 1:5000, respectively. Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Bio-Rad) used at 1:2000 for Ce-GRK-2 and donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Laboratories) used at 1:10000 for α-tubulin. Analysis was completed with SuperSignal West Femto and Pico chemiluminescent substrates (Thermo Scientific) for Ce-GRK-2 and α-tubulin, respectively. The bands were quantified using ImageQuant (Amersham Biosciences). The Ce-GRK-2 levels were normalized to tubulin for each sample. For each experiment/blot, endogenous Ce-GRK-2 levels in the wild-type N2 strain were set to “1,” and transgenic expression levels are reported relative to endogenous Ce-GRK-2. Pooled expression levels from all blots are shown.

RESULTS

Ce-GRK-2 Titration Curve

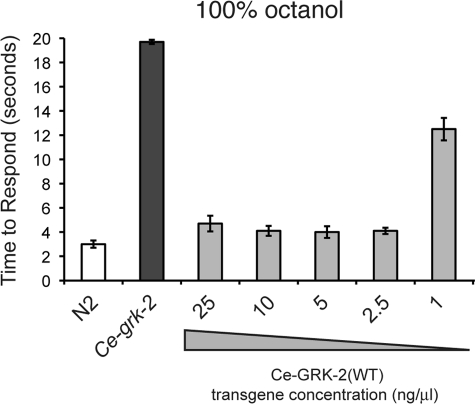

C. elegans lacking endogenous GRK-2 function display broad chemosensory defects that are rescued by transgenic expression of Ce-grk-2 (24). To assess the in vivo contribution of individual conserved amino acid residues within biochemically defined GRK2/3 functional domains and to avoid potential overexpression effects, we titrated wild-type Ce-grk-2 cDNA levels to the minimal injection concentration that rescued aversive behaviors in Ce-grk-2 mutant animals. Transgenic expression of Ce-grk-2 cDNA, under the control of the Ce-grk-2 promoter (24), restored avoidance of the olfactory stimulus 100% octanol across a range of injection concentrations, with the minimum rescuing concentration being 2.5 ng/μl (Fig. 2). Western blot analysis indicated that transgene expression from an injection concentration of 2.5 ng/μl closely reflected endogenous Ce-GRK-2 protein expression levels (n > 10, p > 0.1) (Fig. 3C). Accordingly, each of the mutant Ce-grk-2 cDNAs, also under the control of the Ce-grk-2 promoter (24), was injected at this concentration and tested for its ability to restore avoidance of the volatile odorant octanol and the bitter tastant quinine, both detected primarily by the ASH nociceptive sensory neurons (2–4).

FIGURE 2.

Ce-grk-2 cDNA titration curve. Although Ce-grk-2 mutant animals do not avoid the ASH-detected stimulus 100% octanol, expression of the wild-type (WT) Ce-grk-2 cDNA, under the control of the Ce-grk-2 promoter (24), restored avoidance across a range of injection concentrations. The minimum rescuing concentration was 2.5 ng/μl (p < 0.01 when compared with Ce-grk-2 animals). The time to respond is shown. The bars represent the combined data of at least three independent transgenic lines, n ≥ 49 transgenic animals. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean (S.E.). The allele used was Ce-grk-2(gk268). N2 is the wild-type C. elegans strain.

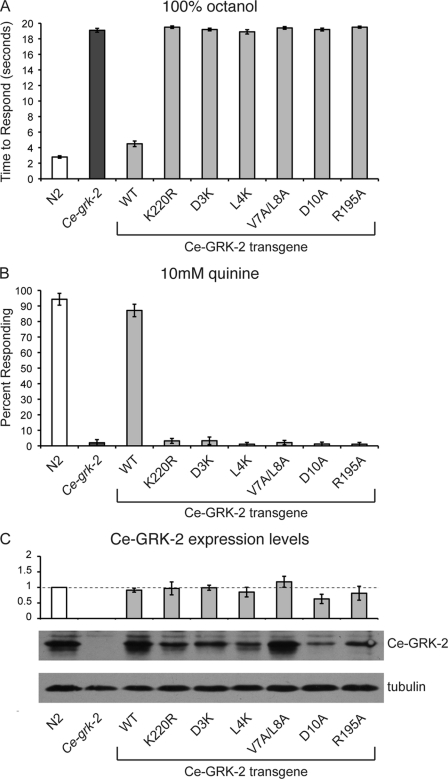

FIGURE 3.

Residues required for GPCR phosphorylation are necessary for Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function. The K220R mutation in the kinase domain of Ce-GRK-2 is predicted to create a kinase dead protein. The D3A, L4A, V7A/L8A, and D10A changes in Ce-GRK-2 are predicted to specifically block the phosphorylation of GPCRs, without disrupting catalytic activity. Each of these mutations disrupts Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function in vivo. A and B, expression of the mutated Ce-grk-2 cDNAs, under the control of the Ce-grk-2 promoter (24), did not restore Ce-grk-2 avoidance of the ASH-detected stimuli 100% octanol (A) or 10 mm quinine (B). p > 0.1 for each transgene when compared with Ce-grk-2 animals. The time to respond is shown in A, and the percentage of animals responding is shown in B. The bars represent the combined data of at least three independent transgenic lines, n ≥ 67 transgenic animals. C, Ce-GRK-2 protein levels were determined by Western blot using anti-GRK2/3 primary antibody. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean (S.E.). p > 0.05 for each when compared with expression of the wild-type Ce-GRK-2 rescuing transgene. The allele used was Ce-grk-2(gk268). N2 is the wild-type C. elegans strain. WT indicates the wild-type Ce-GRK-2 rescuing construct.

Ce-GRK-2 Kinase Activity Is Required for Chemosensory Function

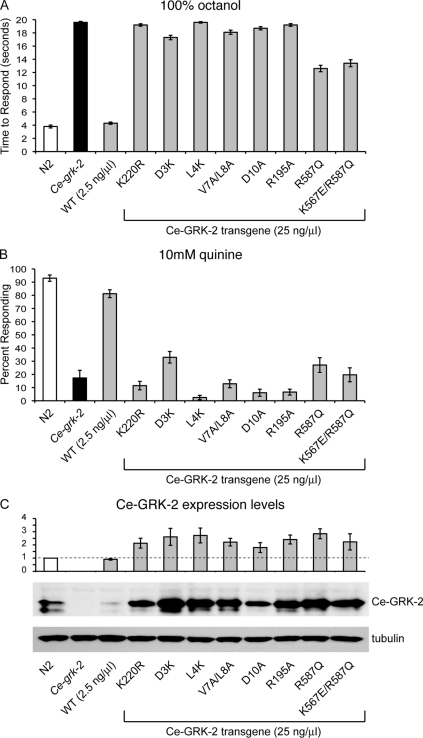

Although GRKs have classically been described to down-regulate GPCR signaling by phosphorylating activated receptors, studies of mammalian GRK2 demonstrated that it can also regulate signaling in a phosphorylation-independent manner (14, 36). This suggests that regions outside of the kinase domain are critical for GRK2 function. To determine whether Ce-GRK-2 catalytic activity is required for regulation of chemosensory signaling in C. elegans, we incorporated a point mutation (K220R) into the kinase domain of Ce-GRK-2. Based on mammalian studies, this change should result in a kinase-dead protein (37). We injected wild-type Ce-grk-2 cDNA and Ce-grk-2(K220R) cDNA into Ce-grk-2 mutant animals and assayed transgenic lines for rescue of chemosensory behavior. Although expression of wild-type Ce-GRK-2 restored the response of Ce-grk-2 mutant animals to both 100% octanol (Fig. 3A) and 10 mm quinine (Fig. 3B), Ce-grk-2 mutant animals expressing Ce-GRK-2(K220R) remained defective for response to both stimuli (Fig. 3, A and B). Because Ce-GRK-2(K220R) also fails to rescue chemosensory behavior when injected at a 10-fold higher concentration (see Fig. 6, A and B), we conclude that Ce-GRK-2 kinase activity is required for the regulation of chemosensory signaling.

FIGURE 6.

Expression of Ce-GRK-2 mutant constructs at 25 ng/μl does not restore Ce-grk-2 chemosensory responses. A and B, although Ce-grk-2 mutant animals do not avoid the ASH-detected stimulus 100% octanol, expression of the wild-type Ce-grk-2 cDNA restored chemosensory responses to the ASH-detected stimuli 100% octanol (A) and 10 mm quinine (B) when injected at 2.5 ng/μl. The K220R mutation in the kinase domain of Ce-GRK-2 is predicted to create a kinase dead protein. The D3A, L4A, V7A/L8A, and D10A changes in Ce-GRK-2 are predicted to specifically block the phosphorylation of GPCRs, without disrupting catalytic activity. Injection of these mutated Ce-grk-2 cDNAs at a 10-fold higher concentration (25 ng/μl) did not restore Ce-grk-2 avoidance of either 100% octanol (A) or 10 mm quinine (B). The K567E change is predicted to disrupt Ce-GRK-2 phospholipid binding, whereas the R587Q change is predicted to disrupt binding to Gβγ. Injection of these mutated Ce-grk-2 cDNAs at the 10-fold higher concentration (25 ng/μl) only modestly restored Ce-grk-2 avoidance of 100% octanol (A, p < 0.001 when compared with N2 or Ce-grk-2 mutant animals) and did not restore avoidance of 10 mm quinine (B, p > 0.1 when compared with Ce-grk-2 mutant animals). The bars represent the combined data of at least three independent transgenic lines, n ≥ 59 transgenic animals. C, Ce-GRK-2 protein levels were determined by Western blot using anti-GRK2/3 primary antibody. Each of the Ce-GRK-2 mutant constructs was expressed at a higher level (≥2-fold higher) than wild-type Ce-GRK-2. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean. p < 0.001 for each when compared with expression of the wild-type Ce-GRK-2 rescuing transgene. The allele used was Ce-grk-2(gk268). N2 is the wild-type C. elegans strain. WT indicates the wild-type Ce-GRK-2 rescuing construct. All of the transgenes were expressed under the control of the Ce-grk-2 promoter (24).

Amino-terminal Residues of Ce-GRK-2 Are Required for Chemosensory Function in Vivo

Although GRKs are classically described as negative regulators of agonist-bound GPCRs, mammalian GRKs have been shown to interact with and phosphorylate a wide variety of other proteins in addition to GPCRs, including signaling molecules (36). The inability of Ce-GRK-2(K220R) to function in chemosensation does not distinguish between a role for Ce-GRK-2 in receptor phosphorylation versus phosphorylation of alternative substrates. Similar to previous studies of mammalian GRK5 (25), recent work indicates that extreme amino-terminal residues of mammalian GRKs, including GRK2, form an amphipathic α-helix that contributes specifically to GPCR phosphorylation (12, 13, 26, 28). Mutation of mammalian GRK2 amino acids Asp-3, Leu-4, Val-7/Leu-8, or Asp-10 greatly reduces phosphorylation of GPCRs in vitro, although these changes do not disrupt tubulin phosphorylation or the ability of GRK2 to interact with GPCRs (26). Each of these residues is conserved in C. elegans GRK-2 (Fig. 1). To determine whether GPCR phosphorylation is required for Ce-GRK-2 function in chemosensation, we incorporated the D3K, L4K, V7A/L8A, and D10A changes into the Ce-grk-2 cDNA and assayed their ability to rescue the Ce-grk-2 ASH-mediated chemosensory defects. As shown in Fig. 3 (A and B), each of these changes also abrogates Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function in vivo. Animals expressing each of the mutant cDNAs failed to avoid the aversive compounds octanol and quinine, similar to Ce-grk-2 mutant animals. Injection of these constructs at a 10-fold higher concentration also failed to restore Ce-grk-2 chemosensory responses (see Fig. 6, A and B), suggesting that phosphorylation of putative chemosensory GPCRs is required for Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo.

Intramolecular Stabilizing Interactions Are Required for Ce-GRK-2 Function in Vivo

Recent reports have described a critical role for the extreme amino-terminal α-helix in stabilizing GRKs in their active GPCR- and ATP-bound conformation (12, 13, 28). Biochemical and structural characterization of bovine GRK1 and human GRK6, respectively, indicated that the amino-terminal α-helix stabilizes conformational changes required for effective substrate phosphorylation through interaction with amino acids in the kinase domain (12, 13, 28). Specifically, in the active conformation of the kinase, an exposed arginine residue on the small kinase lobe (Arg-190 in hGRK6) forms both hydrogen bonds and apolar contacts with the amino-terminal α-helix (13). This arginine is conserved among all GRKs (Fig. 1), and mutation in bGRK1 (Arg-191) and bGRK2 (Arg-195) severely compromised rhodopsin phosphorylation in vitro and β2AR phosphorylation in cell culture (12). In contrast to the amino-terminal α-helix mutants, changing bGRK1 Arg-191 also disrupted phosphorylation of off target substrates, suggesting that this residue is critical for mediating conformational changes required for overall GRK catalytic function (12, 26). To test whether such intramolecular stabilization is required for Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo, we assayed aversive behavioral rescue of Ce-grk-2 mutant animals expressing Ce-GRK-2(R195A). Animals expressing Ce-GRK-2(R195A) remained defective in their avoidance of octanol and quinine, similar to Ce-grk-2 mutant animals (Fig. 3, A and B, and see Fig. 6, A and B). Thus, disruption of predicted intramolecular stabilizing interactions, required for effective receptor phosphorylation by mammalian GRKs, also disrupts Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function.

RH Domain-mediated Interactions Are Not Required for Ce-GRK-2 Chemosensory Function

Although in vitro biochemical studies showed that mammalian GRK2 possesses weak GTPase-activating protein activity (38), mounting evidence suggests that the RH domain does not act as a classical GTPase-activating protein in vivo (36, 39). Instead, it may be involved in phosphorylation-independent regulation of GPCR signaling (39). As such, the RH domain likely interacts with both the receptor and the Gαq/11 subunit, in essence keeping the receptor and Gαq/11 physically separated to block subsequent rounds of activation, while also interfering with the ability of the Gαq/11 subunit to activate downstream effectors (14, 27, 40, 41). Consistent with the biochemical and cellular studies, the crystal structure of mammalian GRK2 in complex with Gαqβγ revealed that GRK2 residues Arg-106 and Asp-110 form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl group of Gαq-Tyr-261 (27).

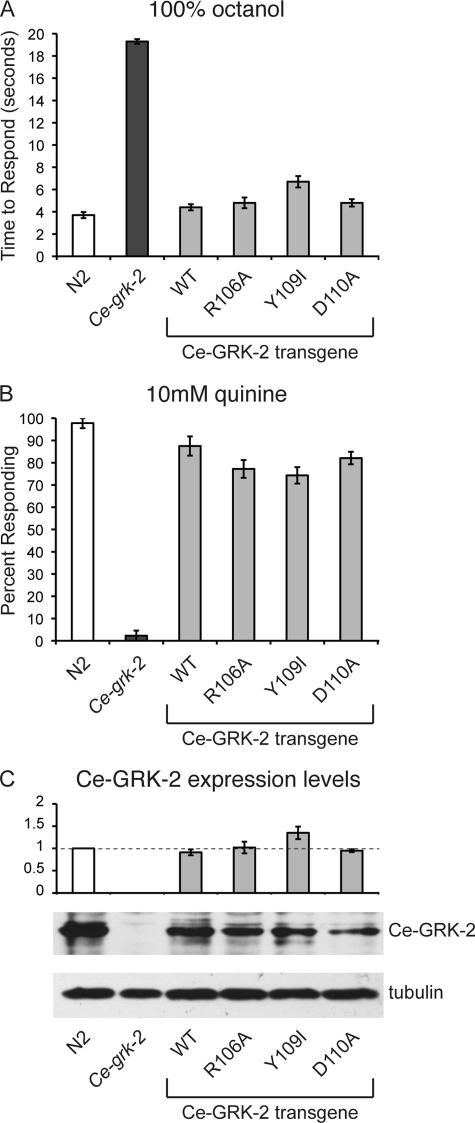

The ASH sensory neurons rely mainly upon two stimulatory Gαs, ODR-3 and GPA-3, which are both most similar to the Gαi/o family, to mediate aversion (3, 42–45). EGL-30 is the single C. elegans Gαq/11 ortholog, and it serves a modulatory role in aversive signaling (43). To determine whether the RH domain of Ce-GRK-2 mediates specific protein interactions that are necessary for its regulatory function in vivo, we introduced changes into Ce-GRK-2 (R106A, Y109I, and D110A) that correspond to mutations in the mammalian GRK2 RH domain that were previously shown to disrupt binding to Gαq/11 (14). Each mutant construct was injected into Ce-grk-2 mutant animals, and transgenic lines were assayed for rescue of ASH-mediated aversive chemosensory behaviors. Mutations that are predicted to disrupt Ce-GRK-2 binding to Gαq/11 subunits had no effect on the ability of Ce-GRK-2 to restore behavioral response to either octanol or quinine (Fig. 4, A and B). These results suggest that Gαq/11 binding or sequestration are not critical for Ce-GRK-2 function in chemosensory signaling and that other functional domains must be sufficient to target Ce-GRK-2 to activated receptors in the ASH sensory neurons. In addition, these results suggest that phosphorylation-independent desensitization of signaling through a Ce-GRK-2-Gαq/11 interaction is unlikely to contribute to the mechanism by which Ce-GRK-2 regulates chemosensory receptor signaling. This is consistent with our finding that the predicted kinase-dead Ce-GRK-2(K220R) mutant does not restore chemosensation to Ce-grk-2 mutant animals (Fig. 3, A and B).

FIGURE 4.

Interactions mediated by the RH domain are not required for Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function. The R106A, Y109I, and D110A changes in Ce-GRK-2 are predicted to disrupt Gαq/11 binding. Each of the mutated constructs, expressed under the control of the Ce-grk-2 promoter (24), restored chemosensory signaling in Ce-grk-2 animals. A, avoidance of 100% octanol. B, avoidance of 10 mm quinine. p < 0.001 for each transgene when compared with Ce-grk-2 animals. The bars represent the combined data of at least three independent transgenic lines, n ≥ 78 transgenic animals. C, Ce-GRK-2 protein levels were determined by Western blot using anti-GRK2/3 primary antibody. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean (S.E.). p ≥ 0.5 for Ce-GRK-2(R106A) and Ce-GRK-2(D110A) expression when compared with the wild-type Ce-GRK-2 rescuing transgene, whereas Ce-GRK-2(Y109I) was expressed at slightly higher levels (p < 0.05). The allele used was Ce-grk-2(gk268). N2 was the wild-type C. elegans strain. WT indicates the wild-type Ce-GRK-2 rescuing construct.

The PH Domain Contributes to Ce-GRK-2 Function in Vivo

Several studies have suggested that the PH domain of mammalian GRK2 and GRK3 mediates translocation to the cell membrane, and by extension activated GPCRs, via specific interactions with membrane phospholipids and Gβγ subunits (23, 36, 46, 47). For example, mammalian GRK2 PH domain interaction with acidic phospholipids increases the level of receptor phosphorylation in vitro (15), whereas PH domain-mediated interaction with Gβγ subunits stimulates GRK2 membrane association and enzymatic activity, enhancing phosphorylation of rhodopsin in rod outer segment preparations (48). Similarly, odorants stimulate the translocation of GRK3 from the cytoplasm to cell membranes in isolated rat olfactory epithelia (23). Expression of a peptide that blocks the GRK3-Gβγ interaction completely blocked the odorant-induced translocation of GRK3 to the membrane and significantly reduced 32Pi incorporation into cell membranes, which presumably correlates with reduced odorant receptor phosphorylation (23). Furthermore, expression of the “blocking” peptide eliminated the termination of cAMP signaling that is usually seen within ∼200 ms of receptor stimulation (23). However, GRK3 knock-out mice have not been examined in chemosensory behavioral assays; it is not known how a loss of mammalian GRK3 function affects the sensory responses of living animals.

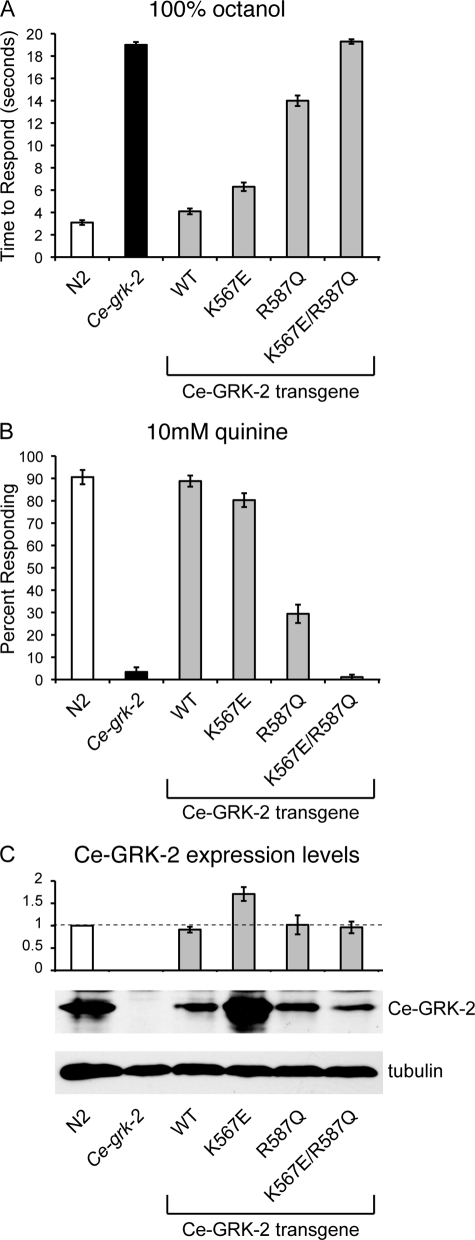

To determine whether phospholipid binding by the PH domain contributes to Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo, the K567E change, which significantly decreases mammalian GRK2 phospholipid binding (15), was incorporated into Ce-GRK-2. This change specifically decreases phosphorylation of activated GPCRs, without decreasing the catalytic activity of mammalian GRK2 (15). However, Ce-grk-2 mutant animals expressing Ce-GRK-2(K567E) showed significantly restored chemosensory avoidance of both octanol and quinine (Fig. 5, A and B), indicating that changing this residue alone is not sufficient to disrupt Ce-GRK-2 function. We do note that this construct is expressed at levels higher than endogenous Ce-GRK-2.

FIGURE 5.

The PH domain of Ce-GRK-2 contributes to its chemosensory function in vivo. The K567E change is predicted to disrupt Ce-GRK-2 phospholipid binding, whereas the R587Q change is predicted to disrupt binding to Gβγ. A and B, although Ce-GRK-2(K567E) retained significant function, Ce-GRK-2(R587Q) only partially restored Ce-grk-2 avoidance of the ASH-detected stimuli 100% octanol (A) and 10 mm quinine (B). Expression of Ce-GRK-2(K567E/R587Q) failed to restore either octanol or quinine avoidance in Ce-grk-2 mutant animals. p > 0.1 when compared with Ce-grk-2 mutant animals. The bars represent the combined data of at least three independent transgenic lines, n ≥ 77 transgenic animals. All of the transgenes were expressed under the control of the Ce-grk-2 promoter (24). C, Ce-GRK-2 protein levels were determined by Western blot using anti-GRK2/3 primary antibody. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean (S.E.). p > 0.5 for Ce-GRK-2(R587Q) and Ce-GRK-2(K567E/R587Q) expression when compared with the wild-type Ce-GRK-2 rescuing transgene, whereas Ce-GRK-2(K567E) was expressed at higher levels (p < 0.001). The allele used was Ce-grk-2(gk268). N2 was the wild-type C. elegans strain. WT indicates the wild-type Ce-GRK-2 rescuing construct.

The C. elegans genome encodes two Gβ (GPB-1 and GPB-2) and two Gγ (GPC-1 and GPC-2) subunits. GPB-1 is ubiquitously expressed and is broadly required for heterotrimeric G protein signaling, including sensory signaling (49–51). GPB-2 is similar to the novel vertebrate Gβ5 subunit (52–55). GPC-1 is expressed in a subset of sensory neurons and is required for response to quinine, as well as adaptation to a variety of attractants and repellents (56, 57), whereas no sensory function has been reported for GPC-2 (58).

In mammalian studies, the R587Q mutation disrupts GRK2 binding to Gβγ (15). We found that this change reduced the ability of Ce-GRK-2 to restore response to octanol and quinine (Figs. 5, A and B, and 6, A and B). This suggests that the GRK-2-Gβγ interaction contributes to Ce-GRK-2 regulation of chemosensory signaling, consistent with previous studies of GRK3 regulation of signaling in olfactory epithelia (23). However, Ce-GRK-2(R587Q) did retain some activity, indicating that other residues and/or functional domains are also critical for Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo. Because phospholipids and Gβγ binding may synergistically recruit GRK2 (and GRK3) to activated receptors (15), the K567E and R587Q mutations were tested in combination. Expression of Ce-GRK-2(K567E/R587Q) failed to restore either octanol or quinine avoidance in Ce-grk-2 mutant animals (Fig. 5, A and B). Injection of Ce-GRK-2(K567E/R587Q) at a 10-fold higher concentration had only a modest rescuing ability for Ce-grk-2 octanol avoidance and no effect on quinine avoidance (Fig. 6, A and B). Combined, our data suggest that the PH domain of Ce-GRK-2 utilizes both phospholipid and Gβγ interactions to mediate the regulation of chemosensory signaling in vivo. A summary of the sites required for Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function is shown in supplemental Fig. S1.

DISCUSSION

Chemosensory signaling is mediated by G protein-coupled receptor signaling cascades across species, including C. elegans (59, 60). The nematode provides a genetically tractable in vivo model that is manipulated in ways not easily accomplished in mammalian systems. Taken in combination with a sophisticated repertoire of reproducible chemosensory behaviors mediated by well characterized neuronal circuits, C. elegans is an ideal system in which to identify and functionally characterize molecular mechanisms that underlie neuronal signal transduction and regulation (59, 60). In particular, the chemosensory deficit characteristic of Ce-grk-2 mutant animals allowed us to selectively disrupt Ce-GRK-2 interactions and function, thereby testing which are required for proper in vivo Ce-GRK-2 regulation of chemosensory signaling. Because the two ASH sensory neurons are the primary sensors of both octanol and quinine (2–4), our studies using behavioral response to these stimuli as the read-out for in vivo function offers a cellular resolution of Ce-GRK-2 activity/interactions not accessible by direct biochemical approaches in the whole animal.

Because GRKs specifically phosphorylate ligand-bound GPCRs, a GRK activation mechanism that depends upon interaction with activated GPCRs would provide intrinsic substrate specificity among the milieu of membrane-bound and associated proteins. Recent reports provide strong evidence that the amino-terminal α-helix of bovine GRK1 and human GRK6, a region conserved among all GRKs, contacts a conserved arginine that is exposed on the small kinase lobe of these enzymes and that this intramolecular interaction is important for the enzymatic stabilization of the kinase domain that is required for effective receptor phosphorylation (12, 13). Interaction between an activated GPCR and the putative receptor docking site formed by the GRK amino-terminal α-helix contacting the small kinase lobe likely mediates both catalytic structure stabilization and proper GPCR phospho-acceptor site positioning in the active ATP-bound GRK catalytic cleft (12, 13). Such a mechanism of activation, incorporating substrate specificity and enzymatic efficiency, would explain why alteration of any of the conserved residues involved in this set of interactions disrupts effective receptor phosphorylation among all mammalian GRKs tested (GRK1, 2, 5, and 6) (12, 13, 25, 26, 28). To determine whether these described interactions are also required for proper GRK activity in vivo, we introduced the corresponding mutations into the Ce-GRK-2 amino-terminal α-helix and small kinase lobe and found that disruption of these stabilizing intramolecular interactions eliminated the ability of Ce-GRK-2 to restore chemosensation when expressed in Ce-grk-2 mutant animals (Figs. 3 and 6). Thus, our chemosensory behavioral results, informed by extensive biochemical and structural characterization of mammalian GRKs, provide corroborating in vivo evidence for this recently proposed universal mechanism of GRK activation (12). Additionally, because both of these regions are critical for receptor phosphorylation in vitro and the behavioral deficits of Ce-grk-2 mutant animals expressing the amino-terminal and small kinase lobe mutants are as severe as animals expressing the kinase dead K220R mutant, we suggest that the primary in vivo regulatory role of Ce-GRK-2 is phosphorylation of putative chemosensory receptors. However, the receptors that detect octanol and quinine in ASH remain unknown.

Mammalian GRK2 and GRK3 bind to GTP-bound Gαq/11 subunits in vitro, sequestering the G protein from activating its downstream effector, PLC-β (14, 38). Although the C. elegans Gαq/11 ortholog EGL-30 contributes to the modulation of ASH-mediated sensory signaling, the Gα subunits ODR-3 and GPA-3, which are more similar to the Gαi/o family, predominantly transduce ASH chemosensory signals (3, 42–44). We found that changing RH domain residues in Ce-GRK-2 that correspond to residues shown to mediate interaction between mammalian GRK2 and Gαq/11 did not disrupt the ability of Ce-GRK-2 to restore ASH-mediated chemosensory behaviors (Fig. 4). Although the residues in bGαq/11 that are required for binding to bGRK2 are completely conserved in EGL-30, they are not present in ODR-3 or GPA-3 (Ref. 27 and supplemental Fig. S2). Thus, although Ce-GRK-2 may interact with EGL-30, disrupting this interaction does not significantly affect Ce-GRK-2 chemosensory function in the ASH neurons. However, we do not rule out a more significant regulatory role for a possible Ce-GRK-2-EGL-30 interaction in different cells or physiological processes where EGL-30 is the primary signaling Gα protein, such as acetylcholine release at neuromuscular junctions, locomotion, or egg laying (52).

Although interaction with Gαq/11 contributes to mammalian GRK2 membrane localization in cell culture (14), our data suggest that this function is mediated primarily by the PH domain in C. elegans chemosensory neurons. Interestingly, changing residues in the Ce-GRK-2 PH domain that correspond to residues shown in vitro to mediate membrane localization differentially affected Ce-GRK-2 activity. Introducing the K567E change to disrupt Ce-GRK-2-phospholipid binding had only a modest effect on its ability to rescue the ASH-mediated chemosensory defects of Ce-grk-2 mutant animals (Fig. 5). Acidic phospholipids also stimulate mammalian GRK2 activity in vitro (15), and loss of this stimulatory effect could underlie the mild decrement in Ce-GRK-2(K567E) function in vivo. In contrast, introducing the R587Q change to disrupt Gβγ binding had a strong effect on Ce-GRK-2 function, and Ce-grk-2 animals expressing this construct remained quite defective in their chemosensory response to both octanol and quinine (Figs. 5 and 6). The functional contribution of the Gβγ interaction is likely to extend beyond recruitment of GRK2/3 family members to the plasma membrane. Upon binding Gβγ, the kinase domain of mammalian GRK2 rotates 10–15° away the membrane, positioning GRK2 for efficient GPCR binding and thus potentially enhancing receptor phosphorylation (61). Thus, it is likely that the loss of both membrane recruitment and optimal kinase domain positioning contributes to the strong decrement in Ce-GRK-2(R587Q) function. Additionally, consistent with the idea that phospholipids and Gβγ binding may synergistically recruit mammalian GRK2/3 to activated receptors (15), simultaneously changing both K567E and R587Q abolished the ability of Ce-GRK-2 to rescue the chemosensory defects of Ce-grk-2 mutant animals (Figs. 5 and 6).

Although mammalian GRK2 has been shown to interact with an array of signaling components with varied effects on function in vitro and in cell culture, a gap has remained in our knowledge of the physiological significance of these interactions in an organismal context (36). Importantly, changes in GRK activity and/or regulation have been linked to several human diseases (10, 62–66). Using C. elegans chemosensation as our read-out, we have identified key residues required for Ce-GRK-2 function in vivo. Moreover, a subset of these residues comprises highly conserved structural features proposed to couple enzymatic activation with GPCR interaction, providing in vivo support for a universal mechanism of GRK activation. Given the high degree of conservation in G protein-coupled signaling cascades between C. elegans and mammals, the studies presented here reflect the power of the simple nematode to provide important insights into the mechanisms used to regulate G protein-coupled signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Cullen, Keith Nehrke, Michael Yu, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for reagents.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0917896 (to D. M. F.). This work was also supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant GM44944 (to J. L. B.).

This article contains supplemental text, references, and Figs. S1 and S2.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

- GPCR kinase

- αN

- amino-terminal α-helix

- RH

- regulator of G protein signaling homology

- PH

- pleckstrin homology.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bargmann C. I. (October 25, 2006) WormBook, The C. elegans Research Community, doi/ 10.1895/wormbook.1.123.1, www.wormbook.org [DOI]

- 2. Troemel E. R., Chou J. H., Dwyer N. D., Colbert H. A., Bargmann C. I. (1995) Divergent seven transmembrane receptors are candidate chemosensory receptors in C. elegans. Cell 83, 207–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hilliard M. A., Bergamasco C., Arbucci S., Plasterk R. H., Bazzicalupo P. (2004) Worms taste bitter: ASH neurons, QUI-1, GPA-3 and ODR-3 mediate quinine avoidance in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 23, 1101–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chao M. Y., Komatsu H., Fukuto H. S., Dionne H. M., Hart A. C. (2004) Feeding status and serotonin rapidly and reversibly modulate a Caenorhabditis elegans chemosensory circuit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15512–15517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. White J. G., Southgate E., Thomson J. N., Brenner S. (1986) The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 314, 1–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sengupta P., Chou J. H., Bargmann C. I. (1996) odr-10 encodes a seven transmembrane domain olfactory receptor required for responses to the odorant diacetyl. Cell 84, 899–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gether U. (2000) Uncovering molecular mechanisms involved in activation of G protein-coupled receptors. Endocr. Rev. 21, 90–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bünemann M., Hosey M. M. (1999) G-protein coupled receptor kinases as modulators of G-protein signalling. J. Physiol. 517, 5–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oldham W. M., Hamm H. E. (2008) Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 60–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pitcher J. A., Freedman N. J., Lefkowitz R. J. (1998) G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 653–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferguson S. S. (2001) Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis. The role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol. Rev. 53, 1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang C. C., Yoshino-Koh K., Tesmer J. J. (2009) A surface of the kinase domain critical for the allosteric activation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17206–17215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boguth C. A., Singh P., Huang C. C., Tesmer J. J. (2010) Molecular basis for activation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases. EMBO J. 29, 3249–3259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sterne-Marr R., Tesmer J. J., Day P. W., Stracquatanio R. P., Cilente J. A., O'Connor K. E., Pronin A. N., Benovic J. L., Wedegaertner P. B. (2003) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2/Gαq/11 interaction. A novel surface on a regulator of G protein signaling homology domain for binding Gα subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6050–6058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carman C. V., Barak L. S., Chen C., Liu-Chen L. Y., Onorato J. J., Kennedy S. P., Caron M. G., Benovic J. L. (2000) Mutational analysis of Gβγ and phospholipid interaction with G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10443–10452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benovic J. L., Onorato J. J., Arriza J. L., Stone W. C., Lohse M., Jenkins N. A., Gilbert D. J., Copeland N. G., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1991) Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of β-adrenergic receptor kinase 2. A new member of the receptor kinase family. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 14939–14946 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schleicher S., Boekhoff I., Arriza J., Lefkowitz R. J., Breer H. (1993) A β-adrenergic receptor kinase-like enzyme is involved in olfactory signal termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 1420–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Benovic J. L., DeBlasi A., Stone W. C., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1989) β-Adrenergic receptor kinase. Primary structure delineates a multigene family. Science 246, 235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jaber M., Koch W. J., Rockman H., Smith B., Bond R. A., Sulik K. K., Ross J., Jr., Lefkowitz R. J., Caron M. G., Giros B. (1996) Essential role of β-adrenergic receptor kinase 1 in cardiac development and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12974–12979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rockman H. A., Choi D. J., Akhter S. A., Jaber M., Giros B., Lefkowitz R. J., Caron M. G., Koch W. J. (1998) Control of myocardial contractile function by the level of β-adrenergic receptor kinase 1 in gene-targeted mice. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 18180–18184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peppel K., Boekhoff I., McDonald P., Breer H., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1997) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 3 (GRK3) gene disruption leads to a loss of odorant receptor desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25425–25428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dawson T. M., Arriza J. L., Jaworsky D. E., Borisy F. F., Attramadal H., Lefkowitz R. J., Ronnett G. V. (1993) β-Adrenergic receptor kinase-2 and β-arrestin-2 as mediators of odorant-induced desensitization. Science 259, 825–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boekhoff I., Inglese J., Schleicher S., Koch W. J., Lefkowitz R. J., Breer H. (1994) Olfactory desensitization requires membrane targeting of receptor kinase mediated by βγ-subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 37–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fukuto H. S., Ferkey D. M., Apicella A. J., Lans H., Sharmeen T., Chen W., Lefkowitz R. J., Jansen G., Schafer W. R., Hart A. C. (2004) G protein-coupled receptor kinase function is essential for chemosensation in C. elegans. Neuron 42, 581–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Noble B., Kallal L. A., Pausch M. H., Benovic J. L. (2003) Development of a yeast bioassay to characterize G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Identification of an NH2-terminal region essential for receptor phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47466–47476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pao C. S., Barker B. L., Benovic J. L. (2009) Role of the amino terminus of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 in receptor phosphorylation. Biochemistry 48, 7325–7333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tesmer V. M., Kawano T., Shankaranarayanan A., Kozasa T., Tesmer J. J. (2005) Snapshot of activated G proteins at the membrane. The Gαq-GRK2-Gβγ complex. Science 310, 1686–1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang C. C., Orban T., Jastrzebska B., Palczewski K., Tesmer J. J. (2011) Activation of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 1 involves interactions between its N-terminal region and its kinase domain. Biochemistry 50, 1940–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brenner S. (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mello C. C., Kramer J. M., Stinchcomb D., Ambros V. (1991) Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans. Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10, 3959–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fukushige T., Hawkins M. G., McGhee J. D. (1998) The GATA-factor elt-2 is essential for formation of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Dev. Biol. 198, 286–302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ezak M. J., Hong E., Chaparro-Garcia A., Ferkey D. M. (2010) Caenorhabditis elegans TRPV channels function in a modality-specific pathway to regulate response to aberrant sensory signaling. Genetics 185, 233–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hart A. C., Kass J., Shapiro J. E., Kaplan J. M. (1999) Distinct signaling pathways mediate touch and osmosensory responses in a polymodal sensory neuron. J. Neurosci. 19, 1952–1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hilliard M. A., Bargmann C. I., Bazzicalupo P. (2002) C. elegans responds to chemical repellents by integrating sensory inputs from the head and the tail. Curr. Biol. 12, 730–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wood W. B. (1988) The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ribas C., Penela P., Murga C., Salcedo A., García-Hoz C., Jurado-Pueyo M., Aymerich I., Mayor F., Jr. (2007) The G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) interactome. Role of GRKs in GPCR regulation and signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768, 913–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kong G., Penn R., Benovic J. L. (1994) A β-adrenergic receptor kinase dominant negative mutant attenuates desensitization of the β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13084–13087 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carman C. V., Parent J. L., Day P. W., Pronin A. N., Sternweis P. M., Wedegaertner P. B., Gilman A. G., Benovic J. L., Kozasa T. (1999) Selective regulation of Gαq/11 by an RGS domain in the G protein-coupled receptor kinase, GRK2. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 34483–34492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pao C. S., Benovic J. L. (2002) Phosphorylation-independent desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors? Sci. STKE 2002, pe42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dhami G. K., Dale L. B., Anborgh P. H., O'Connor-Halligan K. E., Sterne-Marr R., Ferguson S. S. (2004) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 regulator of G protein signaling homology domain binds to both metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a and Gαq to attenuate signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16614–16620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lodowski D. T., Pitcher J. A., Capel W. D., Lefkowitz R. J., Tesmer J. J. (2003) Keeping G proteins at bay. A complex between G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and Gβγ. Science 300, 1256–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roayaie K., Crump J. G., Sagasti A., Bargmann C. I. (1998) The Gα protein ODR-3 mediates olfactory and nociceptive function and controls cilium morphogenesis in C. elegans olfactory neurons. Neuron 20, 55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Esposito G., Amoroso M. R., Bergamasco C., Di Schiavi E., Bazzicalupo P. (2010) The G protein regulators EGL-10 and EAT-16, the Giα GOA-1 and the Gqα EGL-30 modulate the response of the C. elegans ASH polymodal nociceptive sensory neurons to repellents. BMC Biol. 8, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jansen G., Thijssen K. L., Werner P., van der Horst M., Hazendonk E., Plasterk R. H. (1999) The complete family of genes encoding G proteins of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Genet. 21, 414–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hilliard M. A., Apicella A. J., Kerr R., Suzuki H., Bazzicalupo P., Schafer W. R. (2005) In vivo imaging of C. elegans ASH neurons. Cellular response and adaptation to chemical repellents. EMBO J. 24, 63–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Touhara K., Koch W. J., Hawes B. E., Lefkowitz R. J. (1995) Mutational analysis of the pleckstrin homology domain of the β-adrenergic receptor kinase. Differential effects on Gβγ and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17000–17005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Koch W. J., Inglese J., Stone W. C., Lefkowitz R. J. (1993) The binding site for the βγ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins on the β-adrenergic receptor kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 8256–8260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pitcher J. A., Inglese J., Higgins J. B., Arriza J. L., Casey P. J., Kim C., Benovic J. L., Kwatra M. M., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1992) Role of βγ subunits of G proteins in targeting the β-adrenergic receptor kinase to membrane-bound receptors. Science 257, 1264–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van der Voorn L., Gebbink M., Plasterk R. H., Ploegh H. L. (1990) Characterization of a G protein β-subunit gene from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mol. Biol. 213, 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zwaal R. R., Ahringer J., van Luenen H. G., Rushforth A., Anderson P., Plasterk R. H. (1996) G proteins are required for spatial orientation of early cell cleavages in C. elegans embryos. Cell 86, 619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Esposito G., Di Schiavi E., Bergamasco C., Bazzicalupo P. (2007) Efficient and cell specific knock-down of gene function in targeted C.elegans neurons. Gene 395, 170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bastiani C., Mendel J. (October 13, 2006) WormBook, The C. elegans Research Community, doi/ 10.1895/wormbook.1.75.1, www.wormbook.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53. Chase D. L., Patikoglou G. A., Koelle M. R. (2001) Two RGS proteins that inhibit Gαo and Gαq signaling in C. elegans neurons require a Gβ5-like subunit for function. Curr. Biol. 11, 222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Robatzek M., Niacaris T., Steger K., Avery L., Thomas J. H. (2001) eat-11 encodes GPB-2, a Gβ5 ortholog that interacts with Goα and Gqα to regulate C. elegans behavior. Curr. Biol. 11, 288–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van der Linden A. M., Simmer F., Cuppen E., Plasterk R. H. (2001) The G-protein β-subunit GPB-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans regulates the Goα-Gqα signaling network through interactions with the regulator of G-protein signaling proteins EGL-10 and EAT-16. Genetics 158, 221–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jansen G., Weinkove D., Plasterk R. H. (2002) The G protein γ subunit gpc-1 of the nematode C. elegans is involved in taste adaptation. EMBO J. 21, 986–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yamada K., Hirotsu T., Matsuki M., Kunitomo H., Iino Y. (2009) GPC-1, a G protein γ-subunit, regulates olfactory adaptation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 181, 1347–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gotta M., Ahringer J. (2001) Distinct roles for Gα and Gβγ in regulating spindle position and orientation in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Troemel E. R. (1999) Chemosensory signaling in C. elegans. Bioessays 21, 1011–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Prasad B. C., Reed R. R. (1999) Chemosensation. Molecular mechanisms in worms and mammals. Trends Genet. 15, 150–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Boughton A. P., Yang P., Tesmer V. M., Ding B., Tesmer J. J., Chen Z. (2011) Heterotrimeric G protein β1γ2 subunits change orientation upon complex formation with G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) on a model membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E667–E673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Métayé T., Menet E., Guilhot J., Kraimps J. L. (2002) Expression and activity of G protein-coupled receptor kinases in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 3279–3286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yamamoto S., Sippel K. C., Berson E. L., Dryja T. P. (1997) Defects in the rhodopsin kinase gene in the Oguchi form of stationary night blindness. Nat. Genet. 15, 175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yang W., Xia S. H. (2006) Mechanisms of regulation and function of G-protein-coupled receptor kinases. World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 7753–7757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu J. G., Anand K. J. (2001) Protein kinases modulate the cellular adaptations associated with opioid tolerance and dependence. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 38, 1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Coureuil M., Lécuyer H., Scott M. G., Boularan C., Enslen H., Soyer M., Mikaty G., Bourdoulous S., Nassif X., Marullo S. (2010) Meningococcus hijacks a β2-adrenoceptor/β-arrestin pathway to cross brain microvasculature endothelium. Cell 143, 1149–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.