Abstract

Educational expansion has led to greater diversity in the social backgrounds of college students. We ask how schooling interacts with this diversity to influence marriage formation among men and women. Relying on data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (N = 3208), we use a propensity score approach to group men and women into social strata and multilevel event history models to test differences in the effects of college attendance across strata. We find a statistically significant, positive trend in the effects of college attendance across strata, with the largest effects of college on first marriage among the more advantaged and the smallest—indeed, negative—effects among the least advantaged men and women. These findings appear consistent with a mismatch in the marriage market between individuals’ education and their social backgrounds.

Keywords: demography, education, inequality, marriage, multilevel models, National Longitudinal Study of Youth (NLSY)

College has long been a key pathway to financial, physical, and social-psychological well-being (Brand & Xie, 2010; House, 2002; Hout, 1988), and its role in differentiating family patterns has grown (McLanahan, 2004). College graduates are on average more likely to get married and stay married than others, and they are more likely to have and raise their children in marriage (Ellwood & Jencks, 2004; Goldstein & Kenney, 2001; Martin, 2006; Raley & Bumpass, 2003). These differences coincide with fewer resources for families at the lower end of the educational distribution. A growing body of research has examined declines in marriage among the less advantaged (e.g., Edin & Kefalas, 2005), but few researchers have looked at variation within the “stable-marriage” pattern (Cherlin, 2009) characteristic of college graduates.

Increasing college enrollments, particularly among women (Buchmann & DiPrete, 2006), underscore the importance of better understanding variation in the effects of college attendance on family life. Educational expansion has led to greater diversity in the social backgrounds of college students—and to questions about heterogeneity in the meaning and rewards of schooling. Skeptics worry that increased accessibility dilutes the economic advantages of college by drawing in students who are less well-equipped to succeed (e.g., Steinberg, 2010), but evidence in sociology and economics has shown rather that men and women at the margin of college attendance, typically the least socially advantaged, have experienced the greatest economic gains from college (Brand & Xie, 2010; Card, 2001; see Hout, 2009, for a review). We expand this line of inquiry, shifting focus from how the effects of college vary in the labor market to how they vary in the marriage market. We examine variation in the effects of college on marriage among men and women from different social backgrounds.

What do we expect as to variation in the effects of college on marriage, that is, which segments of the college-going population should have greater or lesser effects? Research on the divergence of family patterns by education has emphasized the importance of financial resources for marriage formation, suggesting that those who stand to gain the most financially from college should likewise be in the best position to marry. If individuals with disadvantaged social origins stand to gain the most from college in the labor market, they may in turn gain the most from college in the marriage market. We argue, by contrast, that sociological and cultural factors may play a more influential role than labor market factors in differentiating marriage patterns among college-goers. Men and women assess potential mates not just on earning potential, but on shared values, beliefs, and lifestyles, which are shaped both by school and family environments (e.g., see Kalmijn, 1998, for a review). College-goers from less advantaged social backgrounds may be in a poor position to compete in the marriage market along these dimensions—and thus may be less likely to marry than their more advantaged college-going peers. We investigate this hypothesis with data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NSLY79), which allows us to observe the vast majority of first marriages for a relatively young cohort. We use a propensity score approach to group men and women into social strata (Xie, Brand, & Jann, 2011) and then apply multilevel event history models to test differences in the effects of college on marriage across strata.

In what follows, we review key findings on the (average) relationship between college education and marriage. We then draw from research on the educational divergence in marriage patterns and matching in the marriage market to elaborate how this relationship might vary by social background. In conclusion, we discuss the significance of our findings for understanding the relationship between education and family experiences.

Background

The (Average) Relationship Between Education and Marriage

Men have long translated good economic prospects into good marriage prospects (Cooney & Hogan, 1991; Easterlin, 1980; Goldscheider & Waite, 1986; Oppenheimer, 1994; Oppenheimer, Kalmijn, & Lim, 1997; Sassler & Schoen, 1999). For women, however, a college degree was associated with lower marriage chances for much of the twentieth century in the United States (Goldin, 2004). Among more recent cohorts of women, years of schooling have been found to increase the chances of ever marrying (Oppenheimer, 1994; Thornton, Axinn, & Teachman, 1995; Xie, Raymo, Goyette, & Thornton, 2003). This reversal in the relationship between women’s education and marriage signals a potential change in the meaning of marriage and has led to a shift in the dominant account of marriage from one emphasizing the advantages of differentiation in gender roles (e.g., Becker, 1973, 1974; Parsons, 1949) to one emphasizing the importance of men’s and women’s financial contributions (e.g., Oppenheimer, 1988, 1994; Sweeney, 2002).

Indeed, recent quantitative and qualitative accounts have converged around the importance of both partners’ financial stability as a prerequisite to marriage (Carlson, McLanahan, & England, 2004; Cherlin, 2009; Edin & Kefalas, 2005; Gibson-Davis, 2009; Gibson-Davis, Edin, & McLanahan, 2005; Smock, Manning, & Porter, 2005). Men’s economic prospects have remained more predictive of marriage (Carlson et al.; Smock & Manning, 1997; Smock et al., 2005; Sweeney, 2002; Xie et al., 2003). But evidence for an “affordability” model (Oppenheimer, 1994, p. 315) nonetheless appears strong. It suggests that couples perceive a financial bar to marriage, and that women’s economic prospects have emerged as a factor in overcoming it.

Variation in the Effects of College on Marriage

Estimates of the effect of college on marriage and family (as well as other domains of life) are averages of heterogeneous effects weighted across the college-going population (Brand, 2010; Brand & Davis, 2011; Brand & Xie, 2010; Card, 1999; Morgan & Winship, 2007). It stands to reason that not everyone gets the same things out of higher education, particularly as increasing enrollments have opened the ranks of college-goers to children from more heterogeneous family backgrounds. There has been some attention to how the effects of education on marriage vary by gender, race, and cohort (e.g., Goldstein & Kenney, 2001; Sweeney, 2002). But no demographic research to our knowledge has examined how the effects of college on marriage chances differ by background characteristics that make college attendance more or less likely. We outline below two possible scenarios for how the effects of college on ever marrying might differ by the likelihood of college attendance.

The first idea draws on the affordability model of marriage, which has emerged as a dominant account of the overall link between education and marriage. This model’s emphasis on the importance of men’s and women’s financial contributions to marriage implies that college should generate the greatest gains to marriage where it generates the highest rewards to earnings. Evidence, in turn, has suggested that college serves as the “great equalizer,” offering the highest economic rewards to those from the least advantaged backgrounds (Brand & Xie, 2010; Card, 2001; Hout, 1988, 2009). Synthesizing these strands of research, we might expect college to have the greatest positive effect on marriage among the least advantaged men and women. We emphasize that the least advantaged college-goers may not have the highest marriage rates by this logic, but that the boost to marriage they get from college—relative to the least advantaged who do not go to college—should exceed the boost to more advantaged college-goers.

An alternative way of thinking about variation in the effects of college attendance by social background draws on ideas about matching in the marriage market and places greater emphasis on the noneconomic factors that go into mate selection. Similarities in education and earnings potential have played important roles in marriage market matches, but so too have similarities in social origins, religion, and racial and ethnic background (Johnson, 1980; Kalmijn, 1991a, 1991b, 1998; Mare, 1991; Qian & Lichter, 2007; Schwartz & Mare, 2005). Marital “homogamy”—or this tendency to marry others with similar characteristics—implies social distance between groups and entails the reproduction of social inequalities from one generation to the next. Long-term trends have shown education to be an increasingly important factor in the matching process, with college graduates less likely to marry down and those with very low levels of education less likely to marry up (Blackwell, 1998; Kalmijn, 1991a; Mare, 1991; Schwartz & Mare, 2005). At the same time, similarity in ascriptive dimensions (e.g., social origins, religion, and racial and ethnic background) has declined in importance (Kalmijn, 1991a, 1991b; Lee & Edmonston, 2005), consistent with increasing secularization and openness in the social class structure (Kalmijn, 1991a; Hout, 1988).

Most research on marital homogamy examines matching on one social dimension at a time; there are a few exceptions. Kalmijn (1991a) examined trends in marital homogamy by education and social origins (measured by paternal occupation). He found that while social origins became less important in the matching process over time, they remained a significant factor, net of education. Blackwell (1998) examined the interaction between education and social origins (measured by paternal education). She speculated that more advantaged social origins would compensate for lower levels of education in the matching process (and vice versa), facilitating marriages across lines defined by education and social background. She found, rather, that pairings were more likely between men and women advantaged or disadvantaged on both education and social origins. When it comes to matching in the marriage market, limited quantitative evidence suggests that college does not completely level the playing field; that is, it does not eliminate the effects of social class distinctions on marriage prospects.

Qualitative work by Armstrong and Hamilton has illuminated the ways in which social origins may profoundly affect social life on campus (Armstrong, Hamilton, & Sweeney, 2006; Hamilton, 2007; Hamilton & Armstrong, 2009). In their study, women from less advantaged backgrounds lacked the clothes, money, and connections to fully participate in the mating and dating scene on campus, while at the same time many tried to distance themselves from their lower achieving friends—and especially romantic partners—from their home communities. Armstrong and Hamilton uncovered what is typically unobserved heterogeneity within education groups, showing that social class generates social distance between men and women with the same level of educational attainment. Despite greater diversity in college enrollments by socioeconomic status, college students remain a socioeconomically select group and the dominant social scene may continue to be heavily influenced by students with greater financial and cultural capital. The least advantaged students in particular may have difficulty finding others on campus with similar social class backgrounds, as well as trouble fitting in with higher status peers at school and lower achieving peers at home. According to this marriage market model, college will have the least positive effects, and perhaps even negative effects, on marriage among the least advantaged students.

In sum, we investigate two hypotheses for how the effects of college on marriage might vary by social background. The first, based on the affordability model, emphasizes the importance of financial resources for marriage and suggests that college should have the greatest positive effects where the financial gains are greatest, that is, among the least advantaged men and women. The second places greater emphasis on the social and cultural factors that influence matching in the marriage market. It predicts lower marriage chances among the least advantaged men and women as a result of their mismatched social origins and educational attainment.

Our analysis examines systematic variation in the effects of college on marriage for men and women from different social backgrounds. Effect heterogeneity related to selection is an important source of variation that tends to go unrecognized in empirical sociological research (Brand & Xie, 2010; Elwert & Winship, 2010; Morgan & Winship, 2007; Xie et al., 2011). We use a rich array of background factors known to be important to a child’s later-life success, including family background, early achievement, and social-psychological variables (Blossfeld & Shavit, 1993; Breen & Jonsson, 2005; Buchmann & DiPrete, 2006; Mare, 1981; Sewell & Hauser, 1975), to estimate an individual’s propensity for college. The estimated propensity for college can be thought of as a multidimensional summary measure of social background and early achievement. We stratify our sample according to estimated propensity scores and apply a multilevel event history model of marriage to examine variation in college effects across strata (for discussions of multilevel event history models see Barber, Murphy, Axinn, & Maples, 2000; Teachman, 2011). Conceptually, this strategy is similar to examining an interaction between the effects of college and earlier advantages that select men and women into college. It relies on the logic of propensity score matching to generate social strata based on these selection factors, reducing variation among men and women along multiple dimensions within the same strata.

Method

Analytic Strategy

We used multilevel event history models for estimating the heterogeneous effects of education on marriage by propensity score strata. Multilevel modeling provides a framework for testing differences in the effects of college across social strata. Event history models incorporate age patterns in the heterogeneous effects of college and account for censoring of respondents who either drop out of the survey prior to first marriage or marry after the final survey date. While they can also incorporate time-varying average effects, for example, measures of education that are updated to reflect changes as women age, models to incorporate time-varying heterogeneous education effects would add significant complication to our analyses. We thus focused on college attendance by age 19 in an effort to minimize problems associated with the potential reciprocity of the education–marriage relationship. We restricted all models to individuals “at risk” of a college degree, namely high school graduates, and conducted all analyses separately for men and women. Our restricted focus, while minimizing assumptions for estimating heterogeneous causal effects of education on marriage, limits the generalizability of our findings.

As a first step, we estimated the probability of college attendance for each individual in the sample, separately for men and for women, from a rich set of covariates measured prior to the transition to college. We generated propensity scores based on probit regression models of the following form (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983, 1984):

| (1) |

where Pi is the propensity score for the ith individual; di indicates whether individual i attended college; and X represents a vector of covariates observed prior to college. As Φ is the cumulative normal distribution, the β values are z-scores indicating the expected change in standard deviation units in the latent dependent variable for each covariate k.

Next, and most critically, we assessed heterogeneity in the effects of college. We generated levels of social background by grouping respondents into balanced propensity score strata. Balance is satisfied when the average values of the propensity score and each covariate are statistically indistinguishable within strata between the college- and noncollege-goers (p < .001) (Becker & Ichino, 2002). We then ran a two-level model using the publicly available Stata module –hte– (Jann, Brand, & Xie, 2008), nesting individuals within propensity score strata. In Level 1, we estimated propensity stratum-specific effects using a discrete-time logistic regression model on person-years of age from 19–46:

| (2) |

where f indicates the conditional probability of first marriage for the ith observation at age t in propensity score stratum s; di indicates whether an individual attended college; and A represents age (modeled as a quadratic). Men and women who have not married prior to age 19 enter the risk set and are censored at age of marriage, attrition from the survey, or final survey year (when the oldest respondents are 46).

In Level 2, we estimated the trend in the variation of effects using variance weighted least squares:

| (3) |

where Level 1 slopes (δ) are regressed on propensity score rank indicated by S. The parameter ζ represents the Level 2 slope and thus provides a summary indicator to test the direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of variation in the effects of college across propensity score strata. This approach is similar to propensity score matching, although with propensity score matching, comparison by “treatment status” (e.g., college vs. noncollege) is first made on an individual basis and then averaged over a population. Here, comparison by treatment status was first constructed for relatively homogeneous groups based on propensity scores and then examined across groups.

Finally, we generated model-based estimates to examine age patterns and proportions marrying by age 46. A simple transformation of the logit in equation (2) yields the estimated conditional probability of a first marriage at age t:

| (4) |

These age-specific conditional probabilities can in turn be averaged across individuals and multiplied to generate F, the estimated proportion entering a first marriage by age 46 by propensity score stratum and education level:

| (5) |

We compared the estimated proportions of college- and noncollege–going groups expected to marry across propensity score strata.

Data and Measures

We used panel data from the NLSY79, a national probability sample of 12,686 individuals born in 1957–1964 and living in the United States in 1979 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.). Respondents were 14–21 years old when first interviewed in 1979, and we relied on data through 2008 (the last available round of surveys). Interviews were conducted annually from 1979–1994 and have continued on a biennial basis. Personal interviewing was the primary contact method in all survey years except 1987, in which a limited phone interview was done. Attempts were made in each round to interview all sample members, regardless of whether they missed prior surveys and regardless of their current residence (whether in the United States or abroad). We used NLSY79 sample weights for our descriptive statistics, which adjust for oversampling and differential attrition. Men and women of the NLSY79 represent the late baby boom cohort, coming of age in a period characterized by increasing marital delay (Oppenheimer, 1994), high divorce rates (Martin, 2006), women’s educational expansion (Goldin, Katz, & Kuziemko, 2006), rising maternal employment (Bianchi, 2000), the decoupling of marriage and childbearing (Wu, 2008), and growing inequalities in income and family life (McLanahan, 2004). The NLSY79 have been used for studying heterogeneous effects of education (e.g., Brand, 2010; Brand & Davis, 2011; Brand & Xie, 2010) and the relationship between education and marriage (e.g., Sweeney, 2002; Oppenheimer et al., 1997).

Our sample was restricted to men and women who were 14–17 at the baseline survey in 1979 (n = 5,582) and who had completed at least the 12th grade as of age 19 (n = 3,995). These sample restrictions were set to ensure that all variables used to predict college (particularly ability) were measured before college and to compare college-goers to those who completed at least a high school education. We further excluded cases missing data on college enrollment or our background covariates, with two exceptions: parents’ income and enrollment in a college-preparatory curriculum in high school. Because these variables were missing data for more than 5% of the sample (n = 523 and 199, respectively), we imputed missing values based on all available covariates, running a single imputation using the multivariate normal approach (Little & Rubin, 1987). While there are limitations to single imputation (i.e., artificially low standard errors), the estimation of heterogeneous treatment effects (in Level 2) is complicated by multiple imputation. Nevertheless, we reconstructed our propensity score strata using multiple imputation, and our strata were essentially unchanged whether we used single or multiple imputation; thus, our final results should be largely unaffected. Finally, we excluded men and women who married prior to age 19 (n = 153). Our main samples included 1,574 men and 1,634 women, or 16,803 and 14,750 person-years, respectively.

We defined college attendance as having completed at least 13 years of schooling by age 19. This offers a marker of achievement at a relatively early stage in the life course. By this definition, 31% of our overall sample attended college, and of these, about three quarters were attending 4-year colleges and just over 70% ultimately completed college (both more common among higher strata men and women). Timely college attendees are on average more advantaged than those who attend at an older age (Rosenbaum, Deil-Amen, & Person, 2006). Restricting our sample to high school graduates unmarried by 19 and focusing on timely college attendance limits the extent to which marriage affects educational pursuits. As noted earlier, it also limits the generalizability of our results, in particular, to more advantaged men and women than the overall population.

We examined the timing and occurrence of marriage between the ages of 19 and 46. This age span captures the vast majority of first-marriage experiences (Goodwin, McGill, & Chandra, 2009); in our sample, 80% of men and 87% of women had married by their last observation in the data. The increased incidence of cohabitation has changed the union-formation process, and it has done so differentially by social class, with less advantaged women more likely to cohabit and have children in cohabitation (Furstenberg, 1996; Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008; Thornton et al., 1995). In results not shown (available upon request), we also examined whether the respondent’s first union began in marriage or cohabitation (we relied on a measure of union status at interview, as cohabitation dates were collected on respondent’s current spouse only as of 1990 and current partner as of 1994). We found little evidence of heterogeneity in the effects of college. In part because of these null findings, and in part because there is scant empirical or theoretical groundwork for understanding variation in education effects on union formation, we focus here on marriage.

We used a large set of covariates collected in the first two waves of the NLSY79 to generate our measure of the propensity for college. Family background characteristics included race and ethnicity, mother’s and father’s education, family income in 1979 (when respondents were 14–17), whether the respondent grew up with both biological parents, number of siblings, rural and southern residence, and religious affiliation. Indicators of early achievement included a dummy for whether the student was enrolled in a college-preparatory curriculum in high school and results of a cognitive ability test administered to respondents in 1980 (the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery [ASVAB], adjusted for age and standardized following Cawley, Conneely, Heckman, & Vytlacil, 1997). Social-psychological variables were measured by parents’ encouragement and friends’ plans in 1979. For parents’ encouragement, respondents indicated whether the most influential person in their life (in more than two thirds of cases, a parent) would disapprove if they did not go to college. For friends’ plans, respondents reported the highest level of schooling their best friend planned to obtain.

Table 1 reports variable means by college attendance and gender. Descriptive statistics on our precollege covariates were consistent with well-documented socioeconomic differences in educational attainment (e.g., Brand & Xie, 2010). With few exceptions, these differences were statistically significant at the p < .05 level. Those who attended college were more likely to come from families with highly educated parents, high incomes, both parents present, and fewer siblings. They also had higher average cognitive test scores and were more likely to have had college-preparatory classes, parental encouragement to go to college, and friends with high educational aspirations. The difference in college attendance by gender (shown at the bottom of the table) was statistically significant, with 28% of men versus 35% of women attending college by age 19.

Table 1.

Means of Precollege Covariates, NLSY79 (N = 3,208)

| Variables | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No College | College | No College | College | |

| Race | ||||

| Black (0/1) | .13 | .09** | .15 | .10*** |

| Hispanic (0/1) | .05 | .04 | .05 | .04** |

| Family background | ||||

| Father’s education (years) | 11.93 | 13.97*** | 11.60 | 13.79*** |

| Mother’s education (years) | 11.73 | 13.21*** | 11.51 | 13.09*** |

| Parents’ income (1979 dollars) | $20,255 | $27,628*** | $20,996 | $25,668*** |

| Both parents age 14 (0/1) | .77 | .85*** | .75 | .81* |

| Number of siblings | 3.04 | 2.52*** | 3.30 | 2.68*** |

| Rural residence age 14 (0/1) | .25 | .20* | .23 | .20 |

| Southern residence age 14 (0/1) | .29 | .27 | .31 | .34 |

| Catholic (0/1) | .32 | .33 | .33 | .35 |

| Jewish (0/1) | .01 | .03* | .00 | .04*** |

| Early achievement | ||||

| Cognitive ability (−1.84–2.59) | 0.27 | 0.86*** | 0.02 | 0.51*** |

| College preparatory (0/1) | .30 | .65*** | .26 | .56*** |

| Social-psychological | ||||

| Parents’ encouragement (0/1) | .65 | .89*** | .70 | .87*** |

| Friends’ plans (years schooling) | 13.90 | 15.35*** | 14.03 | 15.25*** |

| Weighted proportiona | .72 | .28 | .65 | .35 |

| Unweighted n | 1,176 | 398 | 1,134 | 500 |

Note. College attendance by age 19. Missing values are imputed on parents’ income and college-preparatory program. “Both parents,” “Rural residence,” and “Southern residence age 14” = living with both parents, in a rural area, or in the South when the young man or woman was age 14.

Cognitive ability is measured with a scale of standardized residuals of the ASVAB. All means are weighted by NLSY79 panel weights; n values are unweighted.

Gender difference in college attendance is statistically significant at p < .001.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. (two-tailed tests of college vs. no college attendance)

Results

We began by estimating probit regression models of college attendance for men and women from the precollege covariates described above. The propensity score estimated from these models serves as our summary measure of social background and early achievement. Results are shown in Table 2. Mother’s education, cognitive test scores, college-track classes, parents’ encouragement, and friends’ plans were all statistically significant predictors of timely college attendance for men and women. Parental income was positively signed and statistically significant for men, but somewhat surprisingly, insignificant for women. This estimate, net of a host of covariates, differed from the positive (and statistically significant) bivariate relationship between parental income and college attendance among women shown in Table 1. We tested the statistical significance of differences in coefficients across models for men and women, and the gender difference in parental income was the only one to attain significance at the p < .05 level.

Table 2.

Propensity Score Regression Models Predicting College Attendance by Age 19 (N = 3,208)

| Variables | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | |

| Black | −0.01 | 0.11 | −0.13 | 0.10 |

| Hispanic | −0.06 | 0.14 | −0.10 | 0.12 |

| Father’s education | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Mother’s education | 0.05* | 0.02 | 0.05* | 0.02 |

| Parents’ income (1979 $1,000s) | 0.99* | 0.38 | −0.14 | 0.36 |

| Both parents age 14 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.09 |

| Number of siblings | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.04* | 0.02 |

| Rural residence age 14 | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.09 |

| Southern residence age 14 | 0.15† | 0.09 | 0.19* | 0.08 |

| Catholic | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Jewish | 0.36 | 0.39 | 1.04* | 0.41 |

| Cognitive ability | 0.68*** | 0.07 | 0.62*** | 0.07 |

| College preparatory | 0.41*** | 0.08 | 0.34*** | 0.08 |

| Parents’ encouragement | 0.38*** | 0.10 | 0.28** | 0.09 |

| Friends’ plans | 0.08*** | 0.02 | 0.08*** | 0.02 |

| Constant | −3.48*** | 0.35 | −2.83*** | 0.33 |

| Wald χ2 | 417.33 | 362.00 | ||

| p > χ2 | .00 | .00 | ||

| n | 1,574 | 1,634 | ||

Note. Probit regression controlling precollege covariates. “Both parents,” “Rural residence,” and “Southern residence age 14” = living with both parents, in a rural area, or in the South when the young man or woman was age 14.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. (two-tailed tests)

We estimated the average effects of timely college attendance on marriage, net of the propensity to attend college (i.e., we ran discrete-time event history models of marriage for men and women on college attendance and our estimated propensity scores). Prior research has emphasized the average effects of completed education on marriage; we found null effects of both timely college attendance and the propensity to attend college (results available on request). From here, we investigated whether these null average effects conceal systematic variation in the effect of college by the probability that one attends college. We generated balanced propensity score strata, such that college- and noncollege-goers within each level shared similar values on our measure of the propensity for college, or social background. We collapsed the lowest two propensity score strata for women and the highest two for both genders (due to cell sizes less than 20) and we adjusted for the estimated propensity scores within the collapsed strata in all models. Men and women were each distributed across five propensity score strata.

Appendix Tables A1 and A2 (in the online version of this article) provide covariate means by propensity score strata and college attendance for men and women, respectively. The frequency distributions for the college and noncollege men and women ran in opposite directions within strata: for the college-educated, the frequency count increased with the propensity score, whereas for the noncollege-educated, the count decreased. Means demonstrate the characteristics of typical men and women within each stratum. In the lower strata, respondents tended to come from families with less education, lower incomes, and more children. They had lower test scores and were less likely to have had college-preparatory classes or friends with college plans.

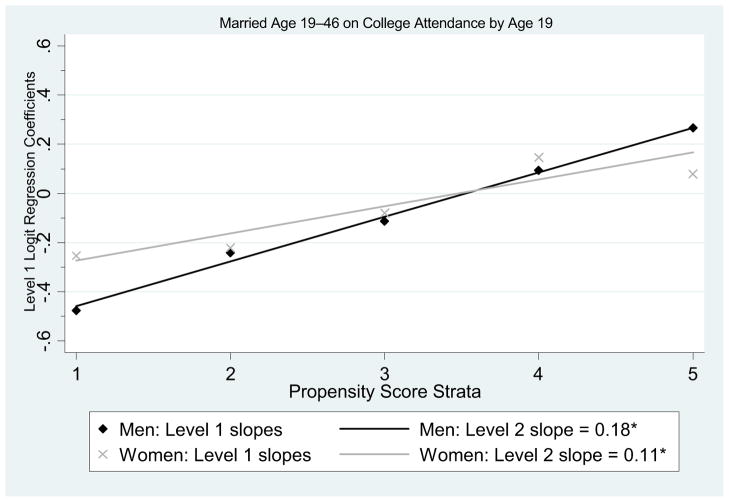

Applying the multilevel event history model described earlier, we estimated the effects of timely college attendance on marriage within propensity score or social strata (in Level 1), and we estimated the linear trend in these effects across strata (in Level 2). Table 3 shows the Level 1 stratum-specific discrete-time logistic regression coefficients and the Level 2 variance-weighted least squares slopes. The Level 1 coefficients were similarly patterned for men and women, increasing with propensity score strata from negative in stratum 1 to positive in stratum 5. Only coefficients in stratum one were statistically significant (p < .10). The exponentiated coefficients or odds ratios indicated a reduction in the age-specific odds of marriage by 38% (i.e., [0.62–1] × 100%) among college-going men and 22% among college-going women in the lowest stratum. Odds ratios in the highest stratum suggested a 31% and 8% increase in marriage among college-going men and women, respectively (although these were not statistically significant differences).

Table 3.

Heterogeneous Effects of College Attendance on Marriage Timing (N = 31,553 person-years)

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | OR | b | SE | OR | |

| Level 1 Slopes | ||||||

| Discrete-Time Event History | ||||||

| P-Score Stratum 1 | −0.48† | 0.27 | 0.62 | −0.25† | 0.14 | 0.78 |

| Men [0.0–0.1), Women [0.0–0.2) | ||||||

| P-Score Stratum 2 | −0.24 | 0.21 | 0.79 | −0.22 | 0.17 | 0.80 |

| Men [0.1–0.2), Women [0.2–0.3) | ||||||

| P-Score Stratum 3 | −0.11 | 0.14 | 0.89 | −0.08 | 0.15 | 0.92 |

| Men [0.2–0.4), Women [0.3–0.4) | ||||||

| P-Score Stratum 4 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 1.10 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 1.16 |

| Men [0.4–0.6), Women [0.4–0.6) | ||||||

| P-Score Stratum 5 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 1.31 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 1.08 |

| Men [0.6–1.0), Women [0.6–1.0) | ||||||

| Level 2 Slope | 0.18* | 0.07 | 0.11* | 0.05 | ||

| Variance Weighted Least Squares | ||||||

| n (person-years) | 16,803 | 14,750 | ||||

Note. OR = odds ratio. Baseline duration for the Level 1 hazard model is a quadratic function of age. Propensity scores generated by probit regression models of college attendance on precollege covariates (see Table 2). Propensity score strata balanced such that mean values of covariates do not significantly differ between college- and noncollege-goers.

p < .10.

p < .05. (two-tailed tests)

The Level 2 slope provides a summary of the direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of the trend in college effects across strata. For both men and women, the Level 2 slope was positive and statistically significant, indicating that college attendance exerted more positive effects on marriage as the level of social advantage increased (consistent with the patterning of Level 1 coefficients described above). For men, the Level 2 slope implied an increase of .18 in the effect of college on the age-specific log-odds of marriage for every 1-unit change in propensity score rank. For women, it implied an increase of .11 in the effect of college for every step up in strata.

Figure 1 summarizes the results presented in Table 3. The markers represent the Level1 stratum-specific discrete-time logistic regression coefficients of college attendance on marriage for men and women, respectively. The linear plots are the Level 2 variance-weighted least squares slopes. The figure clearly depicts the positive linear effect of college attendance on marriage with increasing social advantage. Indeed, the direction of the college effect depended on propensity score strata, with college deterring marriage for the least advantaged men and women and promoting it for the most advantaged. This heterogeneity in college effects on marriage—negative in the lower strata and positive in the higher strata was—consistent with the null average effects of timely college attendance on marriage noted above.

Figure 1.

HTE Multilevel Event History Models of College Effects on First Marriage

If we accept the conclusion of Brand and Xie (2010), these results are inconsistent with the idea that college has the greatest positive effect on marriage where the economic rewards are greatest, that is, among the least advantaged men and women. Rather, our results lend support to the theory of marriage market mismatch, or the idea that college-going men and women from disadvantaged social backgrounds fare more poorly in the marriage market.

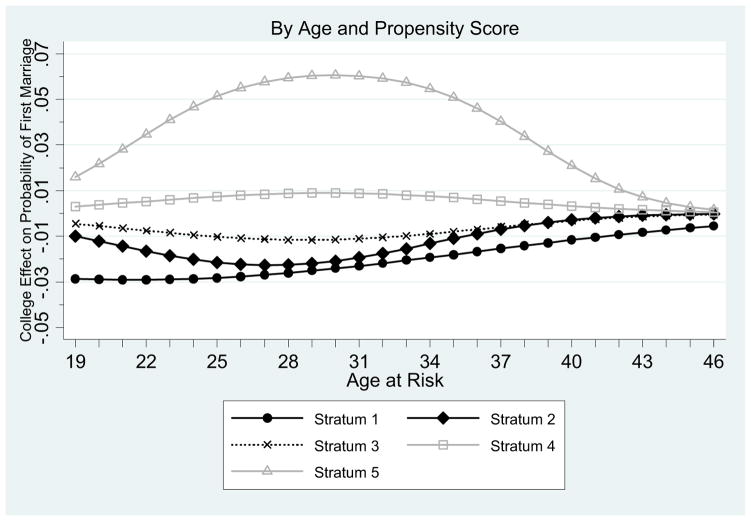

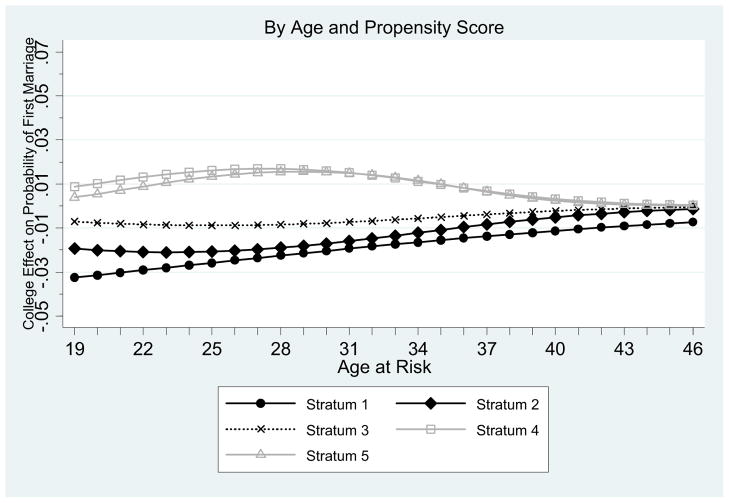

Estimates of Timing and Occurrence

We used the multilevel event history model results to estimate age-specific conditional marriage probabilities, allowing us to flesh out the implications of our models. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate college attendance effects on the probability of first marriage for men and women, respectively. These plot the difference in the age-specific conditional probabilities for college attendees versus non-attendees within each propensity score stratum. The curves are neatly ordered for men, with age-specific college attendance effects on marriage for the higher strata always above (more positive than) those for the lower strata. College appears to have had particularly strong, positive effects on marriage among the highest strata men, peaking around age 30; college effects for men in the lower 3 strata were negative across the life course. The picture for women was similarly patterned by propensity score strata, although the estimated effect of college among women in the highest stratum was on a smaller order of magnitude, very similar to the stratum just below. Recall that these are model-based estimates, and Level 1 college effects in the highest social strata were not statistically significant, although the trends in college effects across strata were.

Figure 2.

College Attendance Effect on Probability of First Marriage: Men By Age and Propensity Score

Figure 3.

College Attendance Effect on Probability of First Marriage: Women By Age and Propensity Score

Multiplying the age-specific conditional marriage probabilities (as in equation 5), we generated model-based estimates of proportions entering into a first marriage by age 46. These estimates are shown in Table 4, by college attendance and social strata. Proportions marrying generally increased across strata, although not monotonically. Estimated differences by college attendance in the proportions marrying were negative for the 3 lower strata and positive or null for the top 2 strata. In stratum 1 (where there were statistically significant differences in the Level 1 coefficients from which these proportions were derived), 79% of the noncollege- versus 63% of the college-going men married by age 46. For women, the analogous contrast was 93% versus 88% entering into a first marriage by age 46. In the highest stratum, virtually all men and women, irrespective of college attendance, were estimated to marry.

Table 4.

Estimated Proportions Marrying by Age 46 Based on Stratum-Specific Discrete-Time Event History Models (N = 31,553 person-years)

| No College Attendance by Age 19 | College Attendance by Age 19 | Difference: College - No College | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 16,803) | |||

| Stratum 1 | .79 | .63 | −.16 |

| Stratum 2 | .83 | .75 | −.08 |

| Stratum 3 | .87 | .84 | −.03 |

| Stratum 4 | .82 | .85 | .03 |

| Stratum 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .00 |

| Women (n = 14,750) | |||

| Stratum 1 | .93 | .88 | −.05 |

| Stratum 2 | .87 | .81 | −.06 |

| Stratum 3 | .90 | .89 | −.02 |

| Stratum 4 | .87 | .90 | .03 |

| Stratum 5 | .98 | .99 | .00 |

Note. Age-specific conditional probabilities of first marriage estimated from stratum-specific discrete-time hazard models. Conditional probabilities multiplied to generate estimated proportions entering first marriage by age 46.

Exploring Sensitivity to Alternative Specifications

We examined results based on alternative definitions of both education and marriage (results available upon request). College attendees, even timely attendees, are a heterogeneous group, differing across social strata in the types of colleges they attend and their chances of ultimately completing college. To narrow heterogeneity in the college-going group, we examined attendance at 4-year schools by age 19 and college completion by age 23 (in this case, limiting the sample to unmarried men and women at age 23). Focusing on these educational transitions generated a more homogeneous sample, but the more restricted scope further limits the generalizability of findings. With attendance at a 4-year school by age 19 or college completion by age 23 as our predictor, our multilevel event history models of marriage yielded similarly patterned results as those obtained for college attendance by age 19, but Level 2 slopes were not statistically significant. Focusing simply on the occurrence of marriage (not the timing), and estimating multilevel logit models of ever marrying in the observation period (as opposed to age-specific multilevel event history models), we found systematic variation in college effects across our three education measures. Level 2 slopes were statistically significant (and of a greater magnitude than in our main analysis), with college increasing marriage chances for the most advantaged men and women and reducing them for the least advantaged.

Exploring the Quality of Marriage Matches

Our results lend support to the hypothesis that college-going men and women from less advantaged social backgrounds do not fare as well in the marriage market as their more advantaged college-going peers. We have no direct evidence as to the barriers to marriage for these men and women. But we can look at those who do marry and make some inference about the quality of their matches. If college-going men and women from lower social-class backgrounds are disadvantaged in the marriage market, they should be both less likely to marry and less likely to marry well. In Table 5, we limited our sample to ever-married men and women and show the proportion with the same level of education as their spouse at the time of first marriage. Comparisons between respondent and spouse education were made across four categories: < 12, 12, 13–15, and 16 + years of education.

Table 5.

Proportion With Same Education as Spouse (Sample Restricted to Ever-Married Persons) (n = 2,474)

| No College Attendance by Age 19 | College Attendance by Age 19 | Difference College - No College | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 1,163) | |||

| Stratum 1 | .58 | .11 | −.47 |

| Stratum 2 | .49 | .37 | −.11 |

| Stratum 3 | .61 | .49 | −.12 |

| Stratum 4 | .60 | .60 | .00 |

| Stratum 5 | .66 | .75 | .09 |

| Women (n = 1,311) | |||

| Stratum 1 | .57 | .23 | −.34 |

| Stratum 2 | .50 | .43 | −.07 |

| Stratum 3 | .55 | .35 | −.20 |

| Stratum 4 | .44 | .44 | .00 |

| Stratum 5 | .60 | .69 | .09 |

Note. Own and spouse education are measured in the first year of the first marriage; education is categorized into 4 levels: < 12, 12, 13–15, and 16 + years. Proportions are weighted by NLSY79 panel weights.

These descriptive statistics show that for both men and women in the noncollege group, there appeared to be little difference in educational similarity between spouses across propensity score strata. But for the college groups, there appeared to be greater educational homogamy with increases in the propensity for college. For example, for male college attendees, the proportion marrying a same-education spouse increased steadily from 11% among those from the lowest social backgrounds (stratum 1) to 75% among those from the most advantaged social backgrounds (stratum 5). This pattern generally held for women, although the upward trend was not monotonic. To test the statistical significance of the trend in homogamy across strata, we estimated a logistic regression of marrying a same-education spouse on the interaction between college attendance and propensity score strata (results available upon request). The interaction was positive and statistically significant. Increasing homogamy with increasing social advantage among college-goers further supports the notion of mismatch in the marriage market. Less advantaged college-goers were both less likely to marry and less likely to marry fellow college-goers.

Discussion

While men’s good economic prospects have long been positively associated with marriage, the positive link between women’s education and marriage is more recent. There has been much interest, for good reason, in the changing nature of the relationship between education and marriage. This educational crossover (i.e., the shift from a negative to a positive association between women’s college education and marriage) signals important changes in the meaning of marriage and coincides with growing social class differences in other dimensions of family life (McLanahan, 2004). Recent research has emphasized the significance of both men’s and women’s financial stability as a prerequisite to marriage (Oppenheimer, 1988, 1994; Sweeney, 2002).

Nevertheless, previously reported college effects are averages of varying effects across men and women from different social backgrounds. Our goal here was to examine variation in the effects of college on marriage across population groups with different probabilities of attending college. The expansion of educational opportunity has increased the heterogeneity of the college-going population, and this has stimulated questions about how the meaning and rewards of college might differ for less advantaged men and women at the margin of college attendance. Evidence suggests that these men and women stand to gain the most from college in the labor market (e.g., Brand & Xie, 2010). We expanded this line of inquiry to investigate how the effects of college play out in the marriage market.

We used a propensity score approach to match men and women on a multidimensional measure of socioeconomic background and early achievement. We then estimated multilevel event history models to test differences in college effects on marriage across the propensity for college attendance. We focused on timely college attendance, a marker of educational attainment observable relatively early in life. For both men and women, we found a statistically significant increase in the effect of college attendance on marriage as the level of social advantage increased. Not only the magnitude but the direction of college effects depended on the propensity for college, with college deterring marriage for men and women from the least advantaged social backgrounds. The similarity in results for men and women is notable, given historical differences in the marriage process by gender.

We offered two ideas about how college effects on marriage might vary. The first, drawing on ideas about the affordability of marriage, emphasizes the importance of financial resources for marriage. It suggests that college should have the greatest positive effects on marriage among men and women for whom the economic rewards of college are highest, that is, among those from the least advantaged social backgrounds. Instead we found that college negatively affected marriage chances for the least advantaged men and women. Our results lend support to an alternative hypothesis that places greater weight on the social and cultural factors that influence matching in the marriage market. Despite declines over time, ascriptively based sorting has long been at play in matching men and women in the marriage market. And while college students are becoming more diverse in their social backgrounds, college-goers remain a socioeconomically select group. The notion of marriage market mismatch predicts lower marriage chances among college-going men and women from the least advantaged social backgrounds, whose limited access to social and cultural capital may restrict social interactions with their more advantaged college-going peers. Men and women with low social origins may be both disadvantaged in the college marriage market and disinclined to marry someone with similar social origins but less education.

We found further support for mismatch in the marriage market by exploring patterns of educational homogamy by social background. The mismatch hypothesis suggests that college-goers with low social origins will be disadvantaged in the marriage market, both less likely to marry and (for those marrying) more likely to marry down educationally. Limiting our sample to ever-married men and women, we found no systematic difference in educational homogamy by social strata among those who did not attend college. Among the college-goers, however, we found a pattern of increasing homogamy with increasing social advantage. In other words, consistent with a mismatch story, we found that the more disadvantaged college-goers were less likely to be matched on education with their spouse.

Our results appear consistent with marriage market mismatch, but our data allow us to assess this hypothesis only indirectly. What else might explain the empirical patterns reported here? Differences in the way family and career goals are balanced—or the extent to which they compete—could provide an alternative account. For example, it could be that low propensity college-goers are particularly motivated by upward mobility and economic rewards and especially willing to defer other goals, including family formation, to fulfill their ambitions in the labor market. Accordingly, they would be less likely to marry than their higher strata counterparts not because of marriage market forces, but because of stronger aspirations for career and economic advancement. This seems entirely plausible, although perhaps more so for women than men. Historically, men have been successful in “having it all,” that is, a career, marriage, and children (Goldin, 2004); indeed, marriage and children appear to boost, at least on average, men’s prospects in the labor market (Correll, Benard, & Paik, 2007; Korenman & Neumark, 1991). Despite the greater success of recent cohorts of women in balancing work and family, women continue to pay a price in the labor market for their roles at home (Correll et al.; Hochschild & Machung, 2003). Thus, if competition between work and family were driving variation in education effects on marriage by social strata, we would expect stronger effects for women; instead we found very similar results by gender. Our expectation of gender differences relies on the assumption that men with disadvantaged social origins behave similarly to average men, but future work may be needed to explore whether men from disadvantaged backgrounds who attain a college education believe they can successfully pursue both a career and family.

The present study has a few important limitations. First, there remains the possibility that omitted variables are correlated with both selection into college and marriage. For example, as just illustrated, low-propensity college-goers could differ in their family and career orientations. If selection bias in the effects of college on marriage were differential across strata, this would alter the pattern of effects found here. Second, there may be variation in our “treatment” across strata; that is, the college experience itself may differ by propensity score strata. For example, low-propensity college-goers are less likely to attend 4-year colleges and to complete college. When we restricted our analysis to 4-year college-goers, the positive trend in college effects across social strata was not statistically significant in our multilevel event history models (although it was significant in models predicting chances of ever marrying). Four-year and 2-year colleges may differ in the functioning of their peer and dating networks; additional work is needed to understand potential implications for marriage. Finally, we focus on the heterogeneous effects of timely college attendance among high school graduates marrying at 19 or older, limiting the extent to which marriage may be affecting educational pursuits, but also limiting the generalizability of our results to a more advantaged group than the overall population. Our understanding of the complex relationship between education and marriage would be advanced by a dynamic model of heterogeneity in the effects of education on family formation, with time-varying treatments that incorporate educational transitions from high school graduation to college completion.

This work expands inquiry into how the effects of college vary, shifting focus from how they vary in the labor market to how they vary in the marriage market. Educational differences in marriage formation are critical to understanding the nature and meaning of broader cleavages in family experiences. Recent research has shown that college-educated men and women are more likely to marry, a legal status that carries with it goods such as social recognition and health insurance (e.g., Musick & Bumpass, in press). We found that within the college-going population, men and women from the most advantaged social backgrounds were also the ones with the best marriage prospects. By revealing the heterogeneity underlying the average effects of college on marriage, this work suggests that college does not equalize the relationship between social origins and family formation patterns.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research made use of facilities and resources at the California Center for Population Research, University of California–Los Angeles, which receives core support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant R24HD041022. Versions of this paper were presented at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, the Minnesota Population Center Seminar, and the University of Pennsylvania Population Studies Center Colloquium. We are grateful to Paula England, Frank Furstenberg, Eric Grodsky, Michel Guillot, Dan Lichter, Carolina Milesi, Cynthia Osborne, Christine Schwarz, and Yu Xie for thoughtful comments on earlier drafts.

Contributor Information

Kelly Musick, Email: musick@cornell.edu, Department of Policy Analysis and Management, Cornell University, 254 Martha Van Rensselaer Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853-4401.

Jennie E. Brand, Department of Sociology, University of California–Los Angeles, 264 Haines Hall, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551

Dwight Davis, Department of Sociology, University of California–Los Angeles, 264 Haines Hall, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551.

References

- Armstrong EA, Hamilton L, Sweeney B. Sexual assault on campus: A multilevel, integrative approach to party rape. Social Problems. 2006;53:483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Barber J, Murphy S, Axinn W, Maples J. Discrete-time multilevel hazard analysis. Sociological Methodology. 2000;30:201–235. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy. 1973;81:813–846. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. A theory of marriage: Part II. Journal of Political Economy. 1974;82:S11–S26. [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Ichino A. Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. Stata Journal. 2002;2:358–377. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM. Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography. 2000;37:401–414. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell DL. Marital homogamy in the United States: The influence of individual and paternal education. Social Science Research. 1998;27:159–188. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H-P, Shavit Y. Persisting barriers: Changes in educational opportunities in thirteen countries. In: Shavit Y, Blossfeld H-P, editors. Persistent inequalities: A comparative study of educational attainment in thirteen countries. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1993. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brand JE. Civic returns to higher education: A note on heterogeneous effects. Social Forces. 2010;89:417–434. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand JE, Davis D. The impact of college education on fertility: Evidence for heterogeneous effects. Demography. 2011;48:863–887. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand JE, Xie Y. Who benefits most from college? Evidence for negative selection in heterogeneous economic returns to higher education. American Sociological Review. 2010;75:273–302. doi: 10.1177/0003122410363567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen R, Jonsson JO. Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann C, DiPrete TA. The growing female advantage in college completion: The role of family background and academic achievement. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:515–541. [Google Scholar]

- Card D. The causal effect of education on earnings. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D, editors. Handbook of labor economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1999. pp. 1801–1863. [Google Scholar]

- Card D. Estimating the return to schooling: Progress on some persistent econometric problems. Econometrica. 2001;69:1127–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, McLanahan S, England P. Union formation in fragile families. Demography. 2004;41:237–261. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley J, Conneely K, Heckman J, Vytlacil E. Cognitive ability, wages, and meritocracy. In: Devlin B, Feinberg SE, Resnick D, Roeder K, editors. Intelligence, genes, and success: Scientists respond to the bell curve. New York: Springer; 1997. pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in America today. New York: Knopf; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney TM, Hogan DP. Marriage in an institutionalized life course: First marriage among American men in the twentieth century. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:178–190. doi: 10.2307/353142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Correll SJ, Benard S, Paik I. Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:297–1338. doi: 10.1086/511799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA. Birth and fortune: The impact of numbers on personal welfare. University of Chicago Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood DT, Jencks C. The spread of single-parent families in the United States since 1960. In: Moynihan DP, Smeeding TM, Rainwater L, editors. The future of the family. New York: Sage; 2004. pp. 25–65. [Google Scholar]

- Elwert F, Winship C. Effect heterogeneity and bias in main-effects-only regression models. In: Dechter R, Geffner H, Halpern JY, editors. Heuristics, probability and causality: A tribute to Judea Pearl. London: College Publications; 2010. pp. 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF., Jr The future of marriage. American Demographics. 1996;18:34–37. 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis CM. Money, marriage, and children: Testing the financial expectations and family formation theory. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:146–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00586.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis CM, Edin K, McLanahan S. High hopes but even higher expectations: The retreat from marriage among low-income couples. Journal of arriage and Family. 2005;67:1301–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00218.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C. The long road to the fast track: Career and family. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;596:20–35. doi: 10.1177/0002716204267959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C, Katz LF, Kuziemko I. The homecoming of American college women: The reversal of the college gender gap. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20:133–156. doi: 10.1257/jep.20.4.133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK, Waite LJ. Sex differences in the entry into marriage. American Journal of Sociology. 1986;92:91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR, Kenney CT. Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:506–519. doi: 10.2307/3088920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin P, McGill B, Chandra A. Who marries and when? Age at first marriage in the United States, 2002 (NCHS Data Brief No. 19) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. pp. 1–8. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db19.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton L. Trading on heterosexuality. Gender and Society. 2007;21:145–172. doi: 10.1177/0891243206297604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton L, Armstrong E. Gendered sexuality in young adulthood: Double binds and flawed options. Gender and Society. 2009;23:589–616. doi: 10.1177/0891243209345829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR, Machung A. The second shift. New York: Penguin Books; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- House JS. Understanding social factors and inequalities in health: 20th century progress and 21st century prospects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:125–142. doi: 10.2307/3090192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hout M. More universalism, less structural mobility: The American occupational structure in the 1980s. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;93:1358–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Hout M. Rationing college opportunity. American Prospect. 2009 Nov;:A8–A10. [Google Scholar]

- Jann B, Brand JE, Xie Y. –hte– Stata module to perform heterogeneous treatment effect analysis. 2008 Retrieved from: http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457129.html.

- Johnson RA. Religious assortative marriage in the United States. New York: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. Shifting boundaries: Trends in religious and educational homogamy. American Sociological Review. 1991a;56:786–800. doi: 10.2307/2096256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. Status homogamy in the United States. American Journal of Sociology. 1991b;97:496–523. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:395–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Bumpass LL. Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1663–1692. doi: 10.4054/demres.2008.19.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenman S, Neumark D. Does marriage really make men more productive? Journal of Human Resources. 1991;26:282–307. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Edmonston B. New marriages, new families: U.S. racial and Hispanic intermarriages. Population Bulletin. 2005;60:3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mare RD. Change and stability in educational stratification. American Sociological Review. 1981;46:72–87. doi: 10.2307/2095027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mare RD. Five decades of educational assortative mating. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:15–32. doi: 10.2307/2095670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP. Trends in marital dissolution by women’s education in the United States. Demographic Research. 2006;15:537–560. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography. 2004;41:607–627. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SL, Winship C. Counterfactuals and causal inference: Methods and principles for social research. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, Bumpass LL. Re-examining the case for marriage: Union formation and changes in well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00873.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:563–591. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review. 1994;20:293–342. doi: 10.2307/2137521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK, Kalmijn M, Lim N. Men’s career development and marriage timing during a period of rising inequality. Demography. 1997;34:311–330. doi: 10.2307/3038286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons T. The social structure of the family. In: Anshen R, editor. The family: Its function and destiny. New York: Harper; 1949. pp. 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z, Lichter DT. Social boundaries and marital assimilation: Interpreting trends in racial and ethnic intermarriage. American Sociological Review. 2007;72:68–94. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Bumpass LL. The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research. 2003;8:245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1984;79:516–524. doi: 10.2307/2288398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JE, Deil-Amen R, Person AE. After admission: From college access to college success. New York: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, Schoen R. The effect of attitudes and economic activity on marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:147–159. doi: 10.2307/353890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CR, Mare RD. Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography. 2005;42:621–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell WH, Hauser RM. Education, occupation, and earnings. Achievement in the early career. New York: Academic Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD. Cohabiting partners’ economic circumstances and marriage. Demography. 1997;34:331–341. doi: 10.2307/3038287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, Porter M. Everything’s there except money”: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:680–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00162.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg J. Plan B: Skip college. New York Times. 2010 May 15; Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/16/weekinreview/16steinberg.html?sq=PlanB:Skipcollege&st=nyt&adxnnl=1&scp=2&adxnnlx=1313793260-uVMSvHw3MROrDL7FX5zBPw.

- Sweeney MM. Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review. 2002;67:132–147. doi: 10.2307/3088937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman J. Modeling repeatable events using discrete-time data: Predicting marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:525–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00827.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Axinn WG, Teachman JD. The influence of school enrollment and accumulation on cohabitation and marriage in early adulthood. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:762–774. doi: 10.2307/2096321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. NLSY79 user’s guide. n.d Retrieved from: http://www.nlsinfo.org/nlsy79/docs/79html/tableofcontents.html.

- Wu LL. Cohort estimates of nonmarital fertility for U.S. women. Demography. 2008;45:193–207. doi: 10.1353/dem.2008.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Brand JE, Jann B. Population Studies Center Research Report 11–729. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan; 2011. Estimating heterogeneous treatment effects with observational data. Retrieved from: http://www.psc.isr.umich.edu/pubs/pdf/rr11-729.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Raymo JM, Goyette K, Thornton A. Economic potential and entry into marriage and cohabitation. Demography. 2003;40:351–367. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.