Abstract

The development of immunosuppressive drugs to control adaptive immune responses has led to the success of transplantation as a therapy for end-stage organ failure. However, these agents are largely ineffective in suppressing components of the innate immune system. This distinction has gained in clinical significance as mounting evidence now indicates that innate immune responses play important roles in the acute and chronic rejection of whole organ allografts. For instance, whereas clinical interest in natural killer (NK) cells was once largely confined to the field of bone marrow transplantation, recent findings suggest that these cells can also participate in the acute rejection of cardiac allografts and prevent tolerance induction. Stimulation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), another important component of innate immunity, by endogenous ligands released in response to ischemia/reperfusion is now known to cause an inflammatory milieu favorable to graft rejection and abrogation of tolerance. Emerging data suggest that activation of complement is linked to acute rejection and interferes with tolerance. In summary, the conventional wisdom that the innate immune system is of little importance in whole organ transplantation is no longer tenable. The addition of strategies that target TLRs, NK cells, complement, and other components of the innate immune system will be necessary to eventually achieve long-term tolerance to human allograft recipients.

Keywords: innate immunity, tolerance, transplantation, allografts, rejection

Introduction

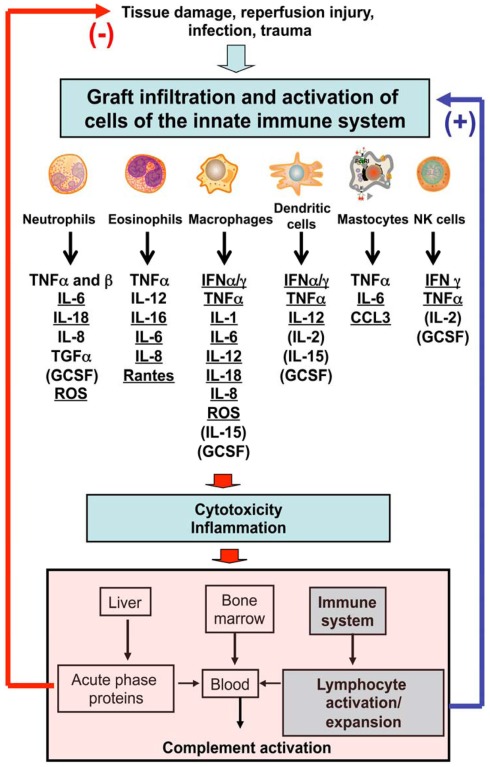

Colossal advances over the past decades with the use of immunosuppressive drugs have significantly enhanced the early survival of allogeneic organs and tissues in clinical transplantation (Cecka, 1998; Opelz et al., 1999; Opelz and Dohler, 2008a,b). Nevertheless, longer term success rates remain disappointing due to treatment-related complications and chronic allograft rejection, a process characterized by perivascular inflammation, tissue fibrosis, and luminal occlusion of graft blood vessels (Hayry et al., 1993; Hosenpud et al., 1997; Russell et al., 1997; Kean et al., 2006). This stresses the need for the development of selective immune-therapies designed to achieve transplantation tolerance defined as indefinite graft survival in the absence of immunosuppression and graft vasculopathy (Billingham et al., 1953; Owen et al., 1954). While tolerance to some solid organ allografts has been accomplished in several experimental rodent models, consistent establishment of tolerance in patients still remains an elusive goal. It is firmly established that the potent adaptive immune responses initiated by pro-inflammatory T cells activated via direct and indirect pathways in the host’s secondary lymphoid organs are both necessary and sufficient to ensure acute rejection of most allografts (Benichou et al., 1992, 1999; Fangmann et al., 1993; Sayegh et al., 1994; Auchincloss and Sultan, 1996; Lee et al., 1997; Waaga et al., 1997). At the same time, it is now firmly established that the presence of alloreactive memory T cells or donor-specific antibodies in so-called sensitized recipients represents a formidable barrier to transplant tolerance induction (Adams et al., 2003a; Taylor et al., 2004; Valujskikh, 2006; Koyama et al., 2007; Weaver et al., 2009; Nadazdin et al., 2010, 2011; Yamada et al., 2011). Indeed, much effort is currently devoted to the elimination or inhibition of donor-specific memory T cells (TMEM) in primates, which, unlike laboratory mice, display high frequencies of alloreactive TMEM prior to transplantation (Nadazdin et al., 2010, 2011). Altogether, the majority of transplant immunologists have focused their efforts on the deletion and/or inactivation of alloreactive T and B cells, pre-transplantation. On the other hand, recent studies have proven beyond doubt that innate immunity is also an essential element of both acute and chronic rejection of allo- and xenografts (LaRosa et al., 2007; Alegre et al., 2008a,b; Alegre and Chong, 2009; Li, 2010; Goldstein, 2011; Murphy et al., 2011). Innate immune responses are initiated as a consequence of reperfusion injury, inflammation, tissue damage, and presumably microbial infections occurring at the time of transplantation (Figure 1). Different cells of the innate immune system can contribute to the rejection process both directly via secretion of soluble factors and destruction of donor grafted cells as well as indirectly by initiating or enhancing adaptive immune alloresponses while impairing the activation/expansion of protective regulatory T cells (Figure 1). At the same time, there is increasing evidence suggesting that different cells and molecules associated with innate immunity can hinder tolerance induction to allografts and xenografts (LaRosa et al., 2007; Alegre et al., 2008b; Wang et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2011). At first glance, it can be speculated that all cells and molecules mediating graft rejection can potentially prevent tolerogenesis. However, immune rejection and tolerance resistance do not necessarily involve the same mechanisms and these two processes are likely to differ in nature and magnitude. This article reviews some of the mechanisms by which innate immunity can interfere with establishment or maintenance of tolerance to allogeneic transplants, an issue that is essential to the design of novel tolerance strategies in transplantation.

Figure 1.

Leukocytes and major cytokines involved in the innate immune response after allotransplantation.

Receptors and Soluble Mediators of the Innate Immune System

Toll-like receptors

Lymphocytes recognize exquisitely a vast array of molecular motifs via their antigen receptors generated through somatic recombination of gene segments during development. In contrast, cells of the innate immune system interact with a few conserved molecules expressed by microorganisms referred to as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs; Medzhitov, 2001; Medzhitov and Janeway, 2002). Among these pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs; Medzhitov, 2001; Elmaagacli et al., 2006; Uematsu and Akira, 2007), the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) have been extensively characterized and studied for their role in the initiation and amplification of innate immune responses (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2004; Pasare and Medzhitov, 2005). In addition, there is increasing evidence that tissue injury is associated with the delivery of signal delivered through TLRs by so-called damage-associated molecular patterns or DAMPs (Alegre et al., 2008a,b).

Until now, 10 different TLRs have been identified in humans (13 in mice), including TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 expressed on the cell surface and TLRs 3, 7, 8, and 9 found in endosomal compartments (Rehli, 2002; Akira and Takeda, 2004; Akira et al., 2006). TLR1 is ubiquitously expressed while the other TLRs exhibit different expression patterns depending upon the type of leukocyte (Muzio et al., 2000; McCurdy et al., 2001; Hornung et al., 2002; Zarember and Godowski, 2002; Bourke et al., 2003; Caramalho et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2003; Nagase et al., 2003; Hart et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006). On the other hand, all TLRs are expressed by epithelial cells while TLRs 5–10 are found in endothelial cells (Frantz et al., 1999) and other graft parenchymal cells depending upon the nature of the organ. All TLRs transduce their signal though the adapter-protein MyD88 (Barton and Medzhitov, 2003; Akira and Takeda, 2004) with the exception of TLR3 which uses the Toll-IL-1R (TIR) inducing IFNβ protein, TRIF (Frantz et al., 1999, 2001; Faure et al., 2000; Tsuboi et al., 2002; Harada et al., 2003; Mempel et al., 2003; Sukkar et al., 2006). TLR4 uses both MyD88 and TRIF during cell activation (Sakaguchi et al., 2003; Goriely et al., 2006; Molle et al., 2007). While the primary functions of TLRs is to ensure early detection of microbes and their products, these receptors have been shown to recognize autologous molecules expressed during the course of inflammatory processes such as nucleic acids released by necrotic cells, products of degraded extracellular matrices, heat shock proteins (HSP60 and HSP70 via TLR2 and TLR4; Asea, 2008), high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 (TLRs 2, 4, and 9), and hyaluronan (TLR signaling via TIRAP; Mollen et al., 2006; Tesar et al., 2006; Ivanov et al., 2007; Kanzler et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2007). Transplant surgical procedures, which are associated with tissue damage and reperfusion injury trigger inflammatory reactions engaging the delivery of signals through TLRs and subsequent initiation of potent innate immune responses at the graft site. In addition, maturation and activation of donor and recipient dendritic cells (DCs) and other cells of the innate immune system via TLR ligation is essential to their ability to initiate and amplify adaptive immunity. This process involves the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Shimamoto et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2007a) and subsequent activation of antigen processing pathways and the expression of costimulation and MHC molecules by APCs involved in antigen presentation to T and B lymphocytes (Bluestone, 1996). Therefore, TLRs are considered to be an essential link between innate and adaptive immunity. These observations suggest that TLRs play a key role in the initiation of innate immune responses and the recruitment and activation of alloreactive lymphocytes associated with allograft rejection. In support of this view, absence of MyD88 adaptor-protein in both donor and recipient mice has led to acceptance of minor antigen-mismatched skin allografts and prolonged survival of fully allogeneic heart and skin transplants (Goldstein et al., 2003; Tesar et al., 2004). Furthermore, combined deficiencies of MyD88 and TRIF and expressions in donors have been shown to significantly extend the survival of MHC-mismatched allografts. At the same time, there is accumulating evidence showing that TLR-mediated responses can hinder tolerance induction to allotransplants. First, it has been reported that long-term survival of skin allografts can be achieved in mice through costimulation blockade but only upon inhibition of TLR signaling in both donors and recipient mice (Chen et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2006). In another study, tolerance to cardiac allografts induced via donor-specific transfusion (DST) combined with anti-CD40L mAb-mediated costimulation blockade was prevented by injection of the TLR9 agonist, CpG as well as the TLR2 ligand, Pam3CysK. In this study, tolerance resistance was attributed to increased γIFN production and inhibition of graft infiltration by regulatory T cells (Chen et al., 2006). Similarly, administration of CpG, LPS, or poly I:C which activate TLR 9, 4, and 3, respectively, prevented tolerance induction to skin allografts induced via DST + anti-CD40L mAbs. In this model, it was observed that TLR engagement prevented the deletion of some effector donor-specific CD8+ T cells (Thornley et al., 2006), a process relying on type I interferon production (Thornley et al., 2007). Finally, Turka’s group recently reported that spontaneous tolerance to MHC class II-mismatched skin heart allografts as well as long-term acceptance of skin allografts mediated via anti-CD40L mAb and rapamycin cotreatment in the B6-bm12 mouse combination were both prevented by CpG administration (Porrett et al., 2008). In this study, prevention of tolerance was dependent on IL-12 production by APCs, which is critical to the differentiation of pro-inflammatory type 1 (Th1/CT1) immunity. Therefore, engagement of certain TLRs at the time of transplantation can hinder tolerance induction to allografts via concomitant enhancement of pro-inflammatory T cell responses and impairment of regulatory T cell functions.

Inflammatory cytokines

Certain pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by cells of the innate immune system can prevent tolerance induction to alloantigens or abrogate established tolerance of an allograft. For instance, IL-6 and TNFα deficiency has been shown to render mice susceptible to transplant tolerance induction via costimulation blockade (Walker et al., 2006; Shen and Goldstein, 2009). Apparently, IL-6 and TNFα contributed to prevent tolerogenesis by enhancing pro-inflammatory immunity while rendering T cells resistant to suppression by Tregs (Walker et al., 2006; Shen and Goldstein, 2009). Likewise, type 1 interferons have been shown to confer tolerance resistance of skin allografts mediated via anti-CD154 mAb treatment in mouse models (Thornley et al., 2007). Tolerance resistance to vascularized allografts induced via costimulation blockade following Listeria monocytogenes infection has been shown to rely on IFN α and β productions. In another study, evidence was provided that IL-6 could prevent transplant tolerance to cardiac allografts induced through the disruption of CD40/CD40L interactions, by promoting the differentiation and activation of CD8+ TH17 cells (Burrell et al., 2008).

IL-1α is produced constitutively and at low levels by many epithelial cells but it is found in substantial amounts in the epidermis where its secretion by keratinocytes is thought to play a key role in the immune defense against microorganisms (Palmer et al., 2007; Arend et al., 2008; Dinarello, 2009; Gabay et al., 2010). In addition, during inflammation and sepsis, activated macrophages, and polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) produce large amounts of IL-1α which is known to cause smooth muscle cell proliferation, secretion of TNFα by endothelial cells, the synthesis of acute phase proteins, and amplify antigen-specific and alloreactive T and B cell responses (Rao et al., 2007, 2008; Rao and Pober, 2008; Dinarello, 2011a). IL-1β, also called lymphocyte activating factor (LAF), is primarily released by activated macrophages during inflammation (Rao et al., 2007; Netea et al., 2010; Dinarello, 2011b,c). It is involved in a variety of cellular activities, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The induction of cyclooxygenase 2 (PTGS2/COX2) by this cytokine in various tissues including the central nervous system (CNS) is found to contribute to hypersensitivity reactions and pain. IL-1α and β play a role in mediating acute inflammation during ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury after transplantation (Suzuki et al., 2001). Ischemia and hyperoxia/anoxia both contributes to the release of IL-1 by macrophages (from the NALP-3 inflammasome), a process leading to both necrosis and apoptosis of transplanted cells, neutrophilic inflammation and initiation, and amplification of adaptive immune responses (Wanderer, 2010). Indeed, it has been shown that overexpression of IL-1R antagonist (IL-1Ra) can confer cardioprotection against I/R injury associated with reduction in cardiomyocyte apoptosis and decrease of neutrophil infiltration and myocardial myeloperoxidase activity in heart-transplanted rats (Suzuki et al., 2001).

There are a few reports showing that IL-1 can prevent tolerance induction to allografts. IL-1β is known to contribute to the breakdown of self-tolerance to pancreatic autoantigens resulting in type 1 diabetes in NOD mice (Bertin-Maghit et al., 2011). This effect is mediated via both induction of TH17 autoimmunity and concomitant impairment of Treg differentiation and functions. Likewise, it has been shown that IL-1 can prevent the induction of tolerance to islet allografts (Sandberg et al., 1993). This is supported by studies showing that continuous infusion of diabetic mice with an IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) can restore normoglycemia and facilitate tolerance to islet allografts (Sandberg et al., 1993). Similarly, alpha-1 anti-trypsin therapy (AAT) has been shown to promote donor-specific tolerance to islet allografts in mice via a process relying on the presence of immature DCs (iDCs) and Tregs in the graft associated with the presence of IL-1Ra (Lewis et al., 2008; Shahaf et al., 2011). In another set of studies by Holan (1988), it was observed that transplantation tolerance induced via inoculation of newborn mice with semi-allogeneic hematopoietic cells was abolished via administration of IL-1 given at the time of placement of skin allografts (Holan, 1988). Finally, a series of studies from Dana and Streilein’s groups have shown that IL-1Ra-based therapy can restore anterior chamber-associated immune deviation (ACAID) type tolerance associated with immune privilege in the eye and acceptance of allogeneic corneal transplants (Dana et al., 1997, 1998; Yamada et al., 1998, 2000; Dekaris et al., 1999). Interestingly, IL-1Ra treatment in this model was shown to abolish donor-specific DTH, reduce corneal graft infiltration by recipient Langerhans cells and abrogate second set rejection of skin allografts suggesting an impaired antigen presentation and a lack of systemic priming of alloreactive T cells through the indirect allorecognition pathway in draining lymph nodes (Dana et al., 1997, 1998; Yamada et al., 1998, 2000; Dekaris et al., 1999).

Chemokines

Chemokines represent an extensive family of proteins whose function was initially associated with leukocyte chemotaxis. It is now clear that these molecules are also involved in a variety of biological processes including angiogenesis and hematopoiesis (Sallusto et al., 2000). There is ample evidence showing that chemokines play a key role in the initiation of alloantigen-dependent and alloantigen-independent reactions associated with transplant injury as well as acute and chronic rejection of allografts (DeVries et al., 2003). Likewise, many studies have shown that absence (KO mouse models) or in vivo neutralization of various chemokines or chemokine receptors, usually combined with short-term or suboptimal calcineurin inhibitory treatment, results in prolonged and sometimes indefinite survival of allografts in animal models (Gao et al., 2000, 2001; Hancock et al., 2000a,b; Fischereder et al., 2001; Abdi et al., 2002). These observations suggest that chemokine release as well as leukocyte activation and migration following chemokine receptor signaling should represent a barrier to transplant tolerance induction and/or maintenance. On the other hand, a number of chemokines have been associated with Treg activation and graft infiltration and are clearly necessary for tolerance induction in transplantation (DeVries et al., 2003).

The complement system

The complement system is comprised of a variety of small proteins including serum proteins, serosal proteins, and cell surface receptors (over 25 proteins and protein fragments, 5% of serum globulin fraction) present in the blood, generally synthesized by the liver, and normally circulating as inactive precursors (pro-proteins; Carroll, 1998; Kang et al., 2009).

When stimulated, the proteases in the system cleave specific proteins and subsequent cytokine release thus initiating an amplifying cascade of further cleavages. The end-result of this activation cascade is a massive amplification of the response and activation of the cell-killing membrane attack complex or MAC (Peitsch and Tschopp, 1991). Three distinct pathways are involved in complement activation: the classical pathway, the alternative pathway, and the mannose-binding lectin pathway (Sacks et al., 2009). All of these pathways converge on C3 whose cleavage leads to the release of soluble C3a and C5a. It is noteworthy that while 80% of C3 is synthesized in the liver, 20% of C3 is of extra hepatic origin and produced by resident parenchymal cells and infiltrating leukocytes (Naughton et al., 1996; Tang et al., 1999; Li et al., 2007). C3a and C5a have anaphylatoxin properties and trigger directly mast cell degranulation and increase vascular permeability and smooth muscle contraction. Most importantly, the complement has opsonizing and chemotactic functions in that it enhances antigen phagocytosis and attracts macrophages and PMNs at the site of inflammation. The complement system represents an essential component of the inflammatory cascade and a major link between innate and adaptive immunity. Likewise, there is now a body of evidence showing that the complement is an essential element of the inflammatory process as well as the immune response associated with the rejection of allogeneic transplants (Zhou et al., 2007; Raedler et al., 2009; Raedler and Heeger, 2010; Vieyra and Heeger, 2010). First, many studies have demonstrated the contribution of the complement to I/R injury following transplantation of a variety of organs including liver, kidney, and lungs (Weisman et al., 1990; Ikai et al., 1996; Eppinger et al., 1997; Huang et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 2000; Chan et al., 2006; Farrar et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2006). Remarkably, mice lacking complement have been shown to be unable to make high affinity anti-MHC antibodies after skin transplantation. This was due to the lack of CR2 expression, a coreceptor that is required for antigen retention by follicular DCs (Fearon and Carroll, 2000; Marsh et al., 2001; Pratt et al., 2002). On the other hand, the complement plays an important role in the antigen processing presentation by DCs and controls their ability to activate T cells in antigen-specific fashion. Finally, elegant studies from the Heeger’s group and others have demonstrated the role of C3 in the activation and expansion of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells presumably by limiting antigen-induced apoptosis (Fearon and Carroll, 2000; Marsh et al., 2001; Pratt et al., 2002; Peng et al., 2006, 2008; Zhou et al., 2006; Lalli et al., 2008; Strainic et al., 2008). Altogether, these studies suggest that activation of the complement cascade following transplantation should render tolerance difficult to induce. In support of this view, it has been shown that blockade of complement activation on DCs results in an increase of Treg expansion and favors tolerance induction (Sacks et al., 2009).

Cells of the Innate Immune System

NK cells

Natural killer (NK) cells contribute to the innate immune response through their ability to recognize and destroy foreign cells in the absence of antigen-specific recognition (Hamerman et al., 2005). However, although NK cells lack expression of germline-encoded antigen receptors, they can discriminate between self- and foreign cells via clonotypic receptors recognizing self-MHC class I molecules. NK cell interacting with self-MHC class I expressed on autologous cells become inactivated while lack or suboptimal recognition of self-MHC class I molecules (missing self phenomenon) on allogeneic cells results in NK cell stimulation associated with release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and cytotoxicity (Karre et al., 1986; Ljunggren and Karre, 1990; Ljunggren et al., 1990). This type of allorecognition has been shown to ensure the destruction of skin grafts from donors lacking self-MHC class I expression (b2m KO) as well as bone marrow transplants from semi-allogeneic donors and parental donors to F1 recipients (hybrid resistance; Karlhofer et al., 1992, 2006). In addition, recent evidence has been provided showing that NK cells also contribute to the rejection of solid organs transplants (Oertel et al., 2000, 2001; Kitchens et al., 2006; McNerney et al., 2006; van der Touw and Bromberg, 2010). NK cells participate in acute allograft rejection either directly by killing donor cells through perforin, granzymes, FasL, and TRAIL pathways (Biron et al., 1999; Smyth et al., 2001; Takeda et al., 2001; Trapani and Smyth, 2002) or indirectly by promoting alloantigen processing and presentation by DCs and B cells (Boehm et al., 1997) and by enhancing Type 1 T cell adaptive alloimmunity primarily though their secretion of γIFN and TNFα (Martin-Fontecha et al., 2004; Yoshida et al., 2008). Furthermore, NK cells have been shown to contribute to the rejection process by killing regulatory T cells (Roy et al., 2008). Finally, some recent studies have demonstrated the pivotal role of NK cells in chronic rejection of cardiac allografts through a process involving CD4+ T cell activation (Uehara et al., 2005a,b). Altogether, these studies support the view that NK cells represent an essential link between innate and adaptive immune responses leading to acute and chronic rejection of allogeneic transplants. On the other hand, a study from Szot et al. (2001) has demonstrated that NK cells can also impair tolerance induction to a solid organ transplant. In this model, injection of recipient CD28-deficient mice with anti-CD154 antibodies failed to accomplish indefinite survival of cardiac allografts. However, tolerance to heart allografts was restored upon in vivo depletion of NK cells or inhibition of the NK activating receptor, NKGD. Apparently, NK cells activated consequently to the absence of self-MHC class I molecules on transplanted cells could provide help (otherwise missing in CD28KO mice) to CD8+ T cells and thereby prevented tolerance induction (Maier et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2007).

Dendritic cells

Dendritic cells are considered as the primary link between innate and adaptive immunity based on their ability to prime naïve T cells owing to: (1) efficient processing and presentation of antigen peptides in association with self-MHC molecules and, (2) the delivery of key costimulation signals (Steinman and Cohn, 1973; Austyn et al., 1983, 1988; Banchereau and Steinman, 1998; Lanzavecchia and Sallusto, 2000, 2001; Steinman et al., 2000). Actually, the T cell alloresponse is primarily initiated through the recognition of intact donor-MHC molecules on donor DCs infiltrating the recipient’s secondary lymphoid organs (direct allorecognition; Steinman and Witmer, 1978; Lechler and Batchelor, 1982; Larsen et al., 1990a,b,c,d; Lechler et al., 1990; Larsen and Austyn, 1991). The direct alloresponse is believed to represent the driving force behind acute allograft rejection. Alternatively, some alloreactive T cells become activated after recognition of donor peptides (MHC and minor antigens) presented by self-MHC molecules on recipient DCs (indirect allorecognition; Benichou et al., 1992, 1999; Dalchau et al., 1992; Fangmann et al., 1992; Liu et al., 1996; Sayegh and Carpenter, 1996). The mechanisms by which recipient DCs acquire donor alloantigens are still unknown. The direct alloresponse is believed to be short-lived due to the rapid elimination of donor DCs, while the indirect alloresponse may be perpetuated by continuous presentation of donor peptides by recipient APCs. While it is clear that indirect alloreactivity is sufficient to trigger vigorous rejection of skin allografts, whether this response plays a significant role in acute rejection of vascularized solid organ transplants is still open to question (Auchincloss et al., 1993; Lee et al., 1994, 1997; Illigens et al., 2002). On the other hand, maintenance of indirect alloresponses via continuous presentation of allopeptides by recipient DCs and endothelial cells is clearly associated with alloantibody production, chronic inflammation, and allograft vasculopathy (Suciu-Foca et al., 1996, 1998; Shirwan, 1999; Baker et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2001; Najafian et al., 2002; Shirwan et al., 2003; Yamada et al., 2003; Illigens et al., 2009). Finally, some recent studies show that recipient DCs can capture donor-MHC molecules and presumably other donor proteins from donor DCs and endothelial through a process called trogocytosis (Joly and Hudrisier, 2003; Aucher et al., 2008). Theoretically, presentation of intact allo-MHC molecules by host professional APCs could activate some alloreactive T cells, a mechanism referred to as semi-direct allorecognition. While, it has been shown that DCs having acquired donor-MHC molecules can activate T cells in vitro and in vivo, the actual contribution of semi-direct alloreactivity to the alloresponse and allograft rejection is still unknown (Herrera et al., 2004; Smyth et al., 2006, 2007).

Dendritic cells consist of a diverse population of cells characterized by a few common surface markers and some functional characteristics (Banchereau and Steinman, 1998; Liu et al., 2009). In addition, DC functions can differ dramatically depending upon their degree of maturation (Steinman et al., 2003; Wilson and Villadangos, 2004). Myeloid iDCs, which have not yet encountered antigens or become activated via PAMPs or cytokine exposure, express low levels of MHC class II and costimulatory receptors and are poor APCs. Presentation of alloantigens by these iDCs has been associated with peripheral tolerance induction (Fu et al., 1996; Dhodapkar et al., 2001; Roncarolo et al., 2001) and immune privilege (Stein-Streilein and Streilein, 2002; Streilein et al., 2002; Masli et al., 2006) presumably via T cell anergy (Fu et al., 1996; Dhodapkar et al., 2001; Roncarolo et al., 2001). In contrast, DCs (mDCS) which underwent maturation following antigen uptake and processing in an inflammatory cytokine environment or exposure to PAMPs and presumably DAMPs express high levels of MHC class II and costimulation receptors are potent inducers of type 1 alloimmunity after transplantation (Rogers and Lechler, 2001). Alternatively, plasmocytoid DCs (pDCs), which represent a small population of DCs mostly located in the peripheral blood, are thought to contribute to tolerance induction via IL-10 secretion following ICOS costimulation and presumably induction of regulatory T cell responses (Abe et al., 2005; Liu, 2005; Ochando et al., 2006; Ito et al., 2007; Tokita et al., 2008; Matta et al., 2010). Finally, seminal studies by Thomson and others have shown that physical or chemical modifications of DCs can render them tolerogenic (Bacci et al., 1996; Kurimoto et al., 2000; Lu and Thomson, 2002; Thomson, 2002; Morelli and Thomson, 2003; Turnquist et al., 2007) and ensure long-term survival to allografts upon their in vivo transfer to recipients (Lu and Thomson, 2002; Thomson, 2002; Morelli and Thomson, 2003; Turnquist et al., 2007).

Altogether, these studies emphasize that DCs represent an essential link between innate and adaptive alloimmunity by serving as APCs for alloantigen presentation to T cells, by providing critical costimulation signals, and by secreting cytokines both at the site of grafting and in the host’s lymphoid tissues and organs. At the same time, it has become evident that the role of DCs in the alloimmune response and rejection process is extremely complex and depends on many factors including the origin (recipient or donor) of the DCs, the nature of the DCs, their level of maturation, and the environment in which they become activated. It was initially assumed that donor or recipient DCs might hinder tolerance induction to allografts owing to their contribution to the priming of alloreactive T cells and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Based upon this principle, many attempts have been made to deplete DCs from transplanted tissues or from the host prior to tolerance induction. Actually, DC depletion has led to various and sometimes opposite outcomes depending upon the nature of the tissue transplanted, the site of graft placement, the method utilized to induce tolerance. For instance, depletion of different DCs from skin transplants such as Langerhans cells or dermal DCs can lead to opposite effects on allograft rejection (Bobr et al., 2010; Igyarto and Kaplan, 2010; Igyarto et al., 2011).

On the overall, most studies showed that absence of DCs, either from recipients or donors in studies using CD11C KO mice, graft parking protocols, or antibody-mediated cell depletion, not only regularly failed to significantly prolong graft survival but it often prevented tolerance induction. This further supports the view that DCs are necessary for antigen presentation during tolerogenesis via their ability to trigger some regulatory mechanisms resulting in graft protection. Further studies will be needed to discriminate between the DCs, which promote or hinder tolerance to allografts and the mechanisms by which they determine the fate of regulatory T cell responses. Gaining insights into these questions will be necessary to delete or inactivate selectively the DCs associated with tolerance resistance in transplantation.

Granulocytes, mastocytes, and monocytes/macrophages

Granulocytes, mastocytes, and monocytes/macrophages are traditionally considered as key players in both early innate alloimmune response and in the actual destruction of donor cells after transplantation. However, the mechanisms by which they contribute to alloimmunity and the actual nature of their contribution to allograft rejection have not been thoroughly investigated. Likewise, little is known regarding the impact of these cells in transplantation tolerance. This section reviews some of the few studies that have tackled these questions.

Granulocytes are the most abundant leukocytes in the blood of mammals and an essential part of the innate immune system. Among them, PMNs migrate within hours to the site of acute inflammation after transplantation following chemical signals such as IL-8, C5a, and Leukotriene B4 in a process called chemotaxis. However, they survive only 1–3 days at the graft site where they undergo degranulation and release reactive oxygen species (ROS), a process involving the activation of NADPH oxidase and the production of superoxide anions and other highly reactive oxygen metabolites which cause tissue damage (Jaeschke et al., 1990). There is ample evidence showing that PMNs contribute to donor tissue destruction and graft rejection in skin transplantation, solid organ transplantation, and bone marrow transplantation (Buonocore et al., 2004; Surquin et al., 2005). Studies from the Fairchild’s group have demonstrated that Abs directed to KC/CXCL1 can prolong cardiac allograft survival by preventing PMNs from graft infiltrating the graft (Morita et al., 2001; LaRosa et al., 2007). Additionally, the potential role of PMNs in the prevention of tolerance induction has been examined in two recent studies, only. First, it has been reported that peritransplant elimination of PMNs facilitated tolerance to fully mismatched cardiac allografts induced via costimulation blockade (El-Sawy et al., 2005; Mollen et al., 2006; LaRosa et al., 2007). Most interestingly, another study from Wood’s group shows that prevention of accelerated rejection of skin allografts by CD8+ effector memory T cells could be achieved by Tregs but only following depletion of PMNs (Jones et al., 2010). It is likely that elimination of PMNs created a window of opportunity that permitted Treg-mediated suppression of graft rejection. Indeed, it well established that early activation of pre-existing alloreactive memory T cells represents a formidable barrier to tolerance induction in transplantation (Valujskikh et al., 2002; Adams et al., 2003b; Valujskikh and Heeger, 2003; Weaver et al., 2009; Nadazdin et al., 2011). In the model described above, PMNs did not prevent tolerance induction directly but indirectly by hindering the suppression of memory T cells by Tregs. It is possible that this phenomenon represents a general mechanism by which innate immunity prevent transplant tolerance induction through the potentiation of alloreactive memory T cells. This implies that blocking innate immune responses at the time of graft placement may impair the development of anamnestic alloresponses by T cells and render allograft susceptible to tolerogenesis by regulatory responses induced after costimulation blockade or mixed hematopoietic chimerism induction, a hypothesis that requires further investigation.

Eosinophils play a key role in the pathogenesis associated with allergic reactions through their production of inflammatory cytokines and cationic proteins (Capron and Goldman, 2001). These cells can drive the differentiation of T cells to TH2 immunity essentially via IL-4 and IL-5 cytokine release (Sanderson, 1992; Kay et al., 1997). TH2 cells that exert antagonist properties toward their pro-inflammatory TH1 counterparts were initially thought to be potential contributors to tolerogenesis in autoimmune diseases and transplantation (Charlton and Lafferty, 1995; Goldman et al., 2001). Indeed, TH2 polarization has been demonstrated to be essential in neonatal tolerance induction and in some allotransplant models (Hancock et al., 1993; Forsthuber et al., 1996; Onodera et al., 1997; Yamada et al., 1999; Kishimoto et al., 2000; Waaga et al., 2001; Fedoseyeva et al., 2002). However, it became rapidly evident that this concept is over simplistic and that eosinophils either directly or via the activation of TH2 cells can trigger the rejection of allografts in various models (Illigens et al., 2009). First, there is ample evidence showing that adoptively transferred allospecific TH2 cells can ensure on their own the rejection of skin and cardiac allogeneic transplants (Piccotti et al., 1996, 1997; VanBuskirk et al., 1996; Shirwan, 1999). Second, IL-4 and IL-5 neutralization has been shown to delay the rejection of allografts in several models (Chan et al., 1995; Simeonovic et al., 1997; Matesic et al., 1998; Le Moine et al., 1999; Braun et al., 2000; Honjo et al., 2000; Goldman et al., 2001; Surquin et al., 2005). In the B6-bm12 MHC class II classical skin graft model, rejection has been associated with a massive infiltration by eosinophils (Le Moine et al., 1999; Goldman et al., 2001). IL-5 blockade delayed the rejection process by preventing eosinophilic infiltration, but these allografts were ultimately rejected via a mechanism involving PMNs (Le Moine et al., 1999; Goldman et al., 2001). In another study from the Martinez’s group, the existence of a non-classical pathway of liver allograft rejection was shown to involve IL-5 and graft infiltrating eosinophils secreting a series of cytotoxic mediators including eosinophil peroxidase, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, eosinophil cationic protein, and major basic protein (MB; Martinez et al., 1993). In addition, a number of studies from us and others have provided direct evidence demonstrating that alloreactive TH2 cells activated through the indirect allorecognition pathway can trigger chronic allograft vasculopathy and tissue fibrosis in MHC class I-mismatched transplanted hearts (Shirwan, 1999; Mhoyan et al., 2003; Koksoy et al., 2004; Illigens et al., 2009). At the same time, it has been reported that, in models in which acute rejection had been suppressed, eosinophilic graft infiltration could induce fibrosis through their production of TGF-β, a key mediator of extracellular matrix remodeling (Goldman et al., 2001). It is noteworthy that eosinophils are likely to play a prominent role in heart and lung transplantation through their cooperation with activated mast cells associated with IL-9 release (Dong et al., 1999; Marone et al., 2000; Suzuki et al., 2000; Cohn et al., 2002; Poulin et al., 2003; Steenwinckel et al., 2007). Interestingly, it has been observed that depletion of CD8+ CT1 cells and subsequent deprivation of γIFN production or IL-12 antagonism can result in a polarization of the T cell response toward TH2 alloimmunity and cause eosinophilic rejection of cardiac allografts primarily driven by IL-4 and IL-5 cytokines (Noble et al., 1998; Foucras et al., 2000; Goldman et al., 2001). This further illustrates the complexity of the alloimmune response and the multiplicity of the mechanisms potentially involved in the rejection process. Indeed, as often observed in autoimmune disease models, blocking a known deleterious type of alloimmunity can often uncover a different type of response also leading to allograft rejection.

Mastocytes were originally described by Paul Ehrlich in his 1878 doctoral thesis on the basis of their unique staining characteristics and large granules (Alvarez-Errico et al., 2009; Barnes, 2011). These cells typically found in mucosal and connective tissues (skin, lungs, and intestines) are characterized by their high expression of IgE high affinity Fc receptor (FcR) and IgG1 (in mice) FcR. Mast cells are known for their pivotal role in immunity against parasitic worms and their contribution to allergic reactions (asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis, and conjunctivitis). This phenomenon is mediated mainly through degranulation of serine proteases, histamine, and serotonin and through recruitment of eosinophils at the site of inflammation via the secretion of eosinophil chemotactic factors (Alvarez-Errico et al., 2009; Barnes, 2011). Mast cells are also essential to the recruitment of T cells to the skin and joints in autoimmune disorders including rheumatoid arthritis, bullous pemphigoid, and multiple sclerosis (Sayed and Brown, 2007; Sayed et al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2010). The role of mastocytes in allotransplantation was actually described in seminal studies for the Voisin’s laboratory more than 40 years ago. It was observed that non-complement fixing anaphylactic IgG1 and IgE antibodies directed to donor-MHC molecules can cause rejection of skin allografts through a process called alloantibody-induced anaphylactic degranulation (DAAD; Daeron et al., 1972, 1975, 1980; Le Bouteiller et al., 1976; Daeron and Voisin, 1978, 1979; Benichou and Voisin, 1987). Hyperacute rejection of skin allografts was induced through bipolar bridging of mastocytes (through their FcR) and donor-MHC molecules on grafted cells, a process leading to a massive anaphylactic reaction leading to allograft rejection (Daeron et al., 1972, 1975, 1980; Le Bouteiller et al., 1976; Daeron and Voisin, 1978, 1979). This type of “allergic transplant rejection” discovered during the 1960s has been largely forgotten through the years and would deserve to be revisited using newly developed immunological models. More recently, it has been shown that degranulating mastocytes can contribute to allograft rejection by causing the loss of Tregs and thereby prevent tolerance induction in a skin allograft model (de Vries et al., 2009a; Murphy et al., 2011). While Tregs can induce the maturation and growth of mastocytes through IL-9 production, this process seems rather to contribute to tolerance induction (Lu et al., 2006; Murphy et al., 2011). In addition, sequestration of pro-inflammatory IL-6 cytokines by mastocytes through MCP6 receptors has also been shown to promote establishment of tolerance to lung and cardiac allografts via costimulation blockade (de Vries et al., 2009a,b, 2010; de Vries and Noelle, 2010; Murphy et al., 2011). Therefore, the role of mastocytes in alloimmunity is more complex than initially anticipated and further studies will be required to determine how these cells can prevent or promote tolerance induction in skin and presumably lung transplantation.

Different macrophages derived from monocyte differentiation are present in various tissues and organs including Kupffer cells in the liver, microglial cells in the CNS, alveolar macrophages in the lungs, and intraglomerular mesangial cells in the kidney (Lu and Unanue, 1982; Unanue, 1984; Yan and Hansson, 2007; Varol et al., 2009; Geissmann et al., 2010; Yona and Jung, 2010). These cells are characterized by the surface expression of CD14, CD11b, F4/80 (mice)/EMR1 (humans) as well as MAC1/3 and CD68. Macrophages and monocytes rapidly infiltrate inflammation sites and are typically found in large numbers within allografts (Geissmann et al., 2010). Upon activation, they release large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-12 IL-1, and IL-6, which promote both innate and adaptive immune responses (Geissmann et al., 2010). Macrophages play a key role in the induction of antibody dependent cellular cytotoxic (ADCC) reactions leading to the phagocytosis of opsonized allogeneic target cells (Unanue and Allen, 1986; Rocha et al., 2003; Li, 2010). During acute inflammation, while PMNs are typically the first phagocytes infiltrating allografts, macrophages are usually involved in secondary stages of inflammation during which they remove aged PMNs via a mechanism involving PECAM-1 (CD31) as well as necrotic cells and cellular debris (Davies et al., 1993; Wu et al., 2007b; Roh et al., 2010; Wu and Madri, 2010). Macrophages have also been shown to be essential to the maintenance of chronic inflammatory processes (Yan and Hansson, 2007; Geissmann et al., 2010). Likewise, some evidence has been provided suggesting that macrophages contribute to transplant vasculopathy and fibrosis (Davies et al., 1993; Kitchens et al., 2007; Yan and Hansson, 2007; Bani-Hani et al., 2009; Dinarello, 2011b; Kamari et al., 2011). In addition to their role in innate immunity, macrophages process, and present alloantigens to CD4+ T cells in a MHC class II context thus initiating T cell-mediated responses and rejection (Beller and Unanue, 1980; Lu et al., 1981; Unanue and Allen, 1986; Unanue, 2002; Calderon et al., 2006). Some observations indicate that, in stable transplants, macrophages can convert otherwise harmless lymphocytes into aggressive ones and cause rejection, thereby controlling the cytopathic features of cellular infiltrates in solid organ transplants (Li, 2010). Likewise, some studies have shown the beneficial effects of blockage of the macrophage-migration inhibitory factor (MIF) on the pathogenesis of allografts including the reduction of obstructive bronchiolitis after lung transplantation (Fukuyama et al., 2005; Javeed and Zhao, 2008). A study from Heeger’s group has shown that in vivo blockade of MIF could prevent the rejection of MHC class II KO skin allografts in mice mediated through the indirect allorecognition pathway (Hou et al., 2001; Demir et al., 2003). In this model, neutralization of MIF resulted in reduced DTH response while it did not affect γIFN production by activated T cells (Hou et al., 2001; Demir et al., 2003). It is, however, noteworthy that different types of macrophages can be found in kidney allografts, some of which being involved in attenuation of inflammation, activation of Tregs, and tolerance induction (Lu et al., 2006; Brem-Exner et al., 2008; Hutchinson et al., 2011). Recently, macrophages have been shown to be involved in self-non-self discrimination, i.e., self-awareness via interaction between the innate inhibitory receptor SIRPα expressed on their surface and CD47. This type of recognition, which is reminiscent of the missing self-model described with NK cells, has been shown to play a role in xenograft rejection by macrophages (Ide et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; van den Berg and van der Schoot, 2008). However, it is still unclear whether some degree of CD47 polymorphism within a given species exists and whether it could be involved in allorecognition.

Concluding Remarks

It is now firmly established that innate immune responses triggered after transplantation as a consequence of tissue damage, infections, and reperfusion injury are an essential element of the inflammatory process leading to early rejection of allografts. In addition, there is accumulating evidence showing the contribution of innate immunity to chronic rejection of allogeneic transplants. On the other hand, this review supports the view that activation of virtually any of the cells of the innate immune system can prevent transplant tolerance induction. This process is essentially mediated via signaling of various receptors including TLRs (via DAMPS and PAMPS) and the secretion of several key pro-inflammatory cytokines (primarily IL-1, IL-6, TNFα, and type I interferons) and chemokines. Activated cells of the innate immune system can prevent tolerogenesis directly via cytokine secretion, activation of the complement cascade, and killing of donor cells or indirectly by promoting and amplifying deleterious inflammatory adaptive immune responses while preventing the activation of protective regulatory mechanisms. In addition, innate immune responses can alter the immune privileged nature of the tissue transplanted or the site of graft placement as evidenced by studies in corneal transplantation. While, it is clear that innate immunity represents a major barrier to tolerogenesis in allotransplantation, this phenomenon is presumably even more relevant to xenotransplantation due to the involvement of natural antibodies, CD47/SIRPα-mediated interactions, and presumably many other still unknown factors. In addition, it is likely that activation of innate type of immunity can abrogate formerly established tolerance to an allograft as suggested by some studies involving microbial infections (Miller et al., 2008; Ahmed et al., 2011a,b). Taken together, these studies imply that the design of future successful tolerance protocols in transplantation will require the administration of agents capable of suppressing innate immunity. However, a number of cells of the innate immune system such as NK cells and DCs have been shown to be required for transplant tolerance induction. This apparent contradiction may be explained by the fact that different cell subsets and mediators of the innate immune system are involved in tolerance vs. rejection. Alternatively certain cells or mediators may play opposite roles depending upon the context in which they are activated. For instance, γIFN and IL-2 have been shown to be essential cytokines in both rejection and tolerance of allografts. It is likely that their dual role depends upon their concentration at a given time point and the cells they are activating in a particular physiological context. These observations illustrate the complexity of the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which innate immunity can influence alloimmunity toward rejection or tolerance. Further dissection of the innate immune response will be required to grasp some of this complexity, at least enough to be able to manipulate this type of immune response to our advantage.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the MGH ECOR and NIAID AI066705 grants to Gilles Benichou and NIH U191066705, PO1HL18646, and ROTRF 313867044 to Joren C. Madsen.

References

- Abdi R., Tran T. B., Sahagun-Ruiz A., Murphy P. M., Brenner B. M., Milford E. L., McDermott D. H. (2002). Chemokine receptor polymorphism and risk of acute rejection in human renal transplantation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 754–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe M., Wang Z., de Creus A., Thomson A. W. (2005). Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors induce allogeneic T-cell hyporesponsiveness and prolong heart graft survival. Am. J. Transplant. 5, 1808–1819 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams A. B., Pearson T. C., Larsen C. P. (2003a). Heterologous immunity: an overlooked barrier to tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 196, 147–160 10.1046/j.1600-065X.2003.00082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams A. B., Williams M. A., Jones T. R., Shirasugi N., Durham M. M., Kaech S. M., Wherry E. J., Onami T., Lanier J. G., Kokko K. E., Pearson T. C., Ahmed R., Larsen C. P. (2003b). Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1887–1895 10.1172/JCI17477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed E. B., Wang T., Daniels M., Alegre M. L., Chong A. S. (2011a). IL-6 induced by Staphylococcus aureus infection prevents the induction of skin allograft acceptance in mice. Am. J. Transplant. 11, 936–946 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03476.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed E. B., Daniels M., Alegre M. L., Chong A. S. (2011b). Bacterial infections, alloimmunity, and transplantation tolerance. Transplant. Rev. (Orlando) 25, 27–35 10.1016/j.trre.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S., Takeda K. (2004). Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 499–511 10.1038/nri1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. (2006). Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124, 783–801 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegre M. L., Chong A. (2009). Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in transplantation. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed) 1, 36–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegre M. L., Goldstein D. R., Chong A. S. (2008a). Toll-like receptor signaling in transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 13, 358–365 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283061149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegre M. L., Leemans J., Le Moine A., Florquin S., De Wilde V., Chong A., Goldman M. (2008b). The multiple facets of toll-like receptors in transplantation biology. Transplantation 86, 1–9 10.1097/01.tp.0000332696.91906.c3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Errico D., Lessmann E., Rivera J. (2009). Adapters in the organization of mast cell signaling. Immunol. Rev. 232, 195–217 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00834.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend W. P., Palmer G., Gabay C. (2008). IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol. Rev. 223, 20–38 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A. (2008). Heat shock proteins and toll-like receptors. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 111–127 10.1007/978-3-540-72167-3_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aucher A., Magdeleine E., Joly E., Hudrisier D. (2008). Capture of plasma membrane fragments from target cells by trogocytosis requires signaling in T cells but not in B cells. Blood 111, 5621–5628 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss H., Jr., Lee R., Shea S., Markowitz J. S., Grusby M. J., Glimcher L. H. (1993). The role of “indirect” recognition in initiating rejection of skin grafts from major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3373–3377 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss H., Jr., Sultan H. (1996). Antigen processing and presentation in transplantation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8, 681–687 10.1016/S0952-7915(96)80086-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austyn J. M., Steinman R. M., Weinstein D. E., Granelli-Piperno A., Palladino M. A. (1983). Dendritic cells initiate a two-stage mechanism for T lymphocyte proliferation. J. Exp. Med. 157, 1101–1115 10.1084/jem.157.4.1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austyn J. M., Weinstein D. E., Steinman R. M. (1988). Clustering with dendritic cells precedes and is essential for T-cell proliferation in a mitogenesis model. Immunology 63, 691–696 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacci S., Nakamura T., Streilein J. W. (1996). Failed antigen presentation after UVB radiation correlates with modifications of Langerhans cell cytoskeleton. J. Invest. Dermatol. 107, 838–843 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12330994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R. J., Hernandez-Fuentes M. P., Brookes P. A., Chaudhry A. N., Cook H. T., Lechler R. I. (2001). Loss of direct and maintenance of indirect alloresponses in renal allograft recipients: implications for the pathogenesis of chronic allograft nephropathy. J. Immunol. 167, 7199–7206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J., Steinman R. M. (1998). Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392, 245–252 10.1038/32588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bani-Hani A. H., Leslie J. A., Asanuma H., Dinarello C. A., Campbell M. T., Meldrum D. R., Zhang H., Hile K., Meldrum K. K. (2009). IL-18 neutralization ameliorates obstruction-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 76, 500–511 10.1038/ki.2009.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P. J. (2011). Pathophysiology of allergic inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 242, 31–50 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01020.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton G. M., Medzhitov R. (2003). Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science 300, 1524–1525 10.1126/science.1085536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beller D. I., Unanue E. R. (1980). IA antigens and antigen-presenting function of thymic macrophages. J. Immunol. 124, 1433–1440 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichou G., Takizawa P. A., Olson C. A., McMillan M., Sercarz E. E. (1992). Donor major histocompatibility complex (MHC) peptides are presented by recipient MHC molecules during graft rejection. J. Exp. Med. 175, 305–308 10.1084/jem.175.1.305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichou G., Valujskikh A., Heeger P. S. (1999). Contributions of direct and indirect T cell alloreactivity during allograft rejection in mice. J. Immunol. 162, 352–358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichou G., Voisin G. A. (1987). Antibody bipolar bridging: isotype-dependent signals given to guinea pig alveolar macrophages by anti-MHC alloantibodies. Cell. Immunol. 106, 304–317 10.1016/0008-8749(87)90174-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin-Maghit S., Pang D., O’Sullivan B., Best S., Duggan E., Paul S., Thomas H., Kay T. W., Harrison L. C., Steptoe R., Thomas R. (2011). Interleukin-1beta produced in response to islet autoantigen presentation differentiates T-helper 17 cells at the expense of regulatory T-cells: implications for the timing of tolerizing immunotherapy. Diabetes 60, 248–257 10.2337/db10-0104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingham R. E., Brent L., Medawar P. B. (1953). Activity acquired tolerance of foreign cells. Nature 172, 603–606 10.1038/172603a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron C. A., Nguyen K. B., Pien G. C., Cousens L. P., Salazar-Mather T. P. (1999). Natural killer cells in antiviral defense: function and regulation by innate cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 189–220 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone J. A. (1996). Costimulation and its role in organ transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 10, 104–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobr A., Olvera-Gomez I., Igyarto B. Z., Haley K. M., Hogquist K. A., Kaplan D. H. (2010). Acute ablation of Langerhans cells enhances skin immune responses. J. Immunol. 185, 4724–4728 10.4049/jimmunol.1001802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm U., Klamp T., Groot M., Howard J. C. (1997). Cellular responses to interferon-gamma. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 749–795 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke E., Bosisio D., Golay J., Polentarutti N., Mantovani A. (2003). The toll-like receptor repertoire of human B lymphocytes: inducible and selective expression of TLR9 and TLR10 in normal and transformed cells. Blood 102, 956–963 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M. Y., Desalle F., Le Moine A., Pretolani M., Matthys P., Kiss R., Goldman M. (2000). IL-5 and eosinophils mediate the rejection of fully histoincompatible vascularized cardiac allografts: regulatory role of alloreactive CD8(+) T lymphocytes and IFN-gamma. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 1290–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem-Exner B. G., Sattler C., Hutchinson J. A., Koehl G. E., Kronenberg K., Farkas S., Inoue S., Blank C., Knechtle S. J., Schlitt H. J., FŠndrich F., Geissler E. K. (2008). Macrophages driven to a novel state of activation have anti-inflammatory properties in mice. J. Immunol. 180, 335–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore S., Surquin M., Le Moine A., Abramowicz D., Flamand V., Goldman M. (2004). Amplification of T-cell responses by neutrophils: relevance to allograft immunity. Immunol. Lett. 94, 163–166 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell B. E., Csencsits K., Lu G., Grabauskiene S., Bishop D. K. (2008). CD8+ Th17 mediate costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection in T-bet-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 181, 3906–3914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon B., Suri A., Unanue E. R. (2006). In CD4+ T-cell-induced diabetes, macrophages are the final effector cells that mediate islet beta-cell killing: studies from an acute model. Am. J. Pathol. 169, 2137–2147 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capron M., Goldman M. (2001). The eosinophil, a cell with multiple facets. Therapie 56, 371–375 10.1016/S0093-691X(01)00570-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramalho I., Lopes-Carvalho T., Ostler D., Zelenay S., Haury M., Demengeot J. (2003). Regulatory T cells selectively express toll-like receptors and are activated by lipopolysaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 197, 403–411 10.1084/jem.20021633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M. C. (1998). The role of complement and complement receptors in induction and regulation of immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16, 545–568 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecka M. (1998). Clinical outcome of renal transplantation. Factors influencing patient and graft survival. Surg. Clin. North Am. 78, 133–148 10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70639-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R. K., Ibrahim S. I., Takahashi K., Kwon E., McCormack M., Ezekowitz A., Carroll M. C., Moore F. D., Jr., Austen W. G., Jr. (2006). The differing roles of the classical and mannose-binding lectin complement pathways in the events following skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion. J. Immunol. 177, 8080–8085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. Y., DeBruyne L. A., Goodman R. E., Eichwald E. J., Bishop D. K. (1995). In vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells results in Th2 cytokine production and alternate mechanisms of allograft rejection. Transplantation 59, 1155–1161 10.1097/00007890-199502150-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton B., Lafferty K. J. (1995). The Th1/Th2 balance in autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7, 793–798 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Wang T., Zhou P., Ma L., Yin D., Shen J., Molinero L., Nozaki T., Phillips T., Uematsu S., Akira S., Wang C. R., Fairchild R. L., Alegre M. L., Chong A. (2006). TLR engagement prevents transplantation tolerance. Am. J. Transplant. 6, 2282–2291 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn L., Whittaker L., Niu N., Homer R. J. (2002). Cytokine regulation of mucus production in a model of allergic asthma. Novartis Found. Symp. 248, 201–213; discussion 213–220, 277–282. 10.1002/0470860790.ch13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeron M., Duc H. T., Kanellopoulos J., Le Bouteiller P., Kinsky R., Voisin G. A. (1975). Allogenic mast cell degranulation induced by histocompatibility antibodies: an in vitro model of transplantation anaphylaxis. Cell. Immunol. 20, 133–155 10.1016/0008-8749(75)90092-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeron M., Kinsky R. G., Voisin G. A. (1972). In vitro anaphylactic degranulation of mast cells by transplantation antibodies in mice. C.R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. Ser. D Sci. Nat. 275, 2571–2573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeron M., Prouvost-Danon A., Voisin G. A. (1980). Mast cell membrane antigens and Fc receptors in anaphylaxis. II. Functionally distinct receptors for IgG and for IgE on mouse mast cells. Cell. Immunol. 49, 178–189 10.1016/0008-8749(80)90067-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeron M., Voisin G. A. (1978). H-2 antigens, on mast cell membrane, as target antigens for anaphylactic degranulation. Cell. Immunol. 37, 467–472 10.1016/0008-8749(78)90214-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeron M., Voisin G. A. (1979). Mast cell membrane antigens and Fc receptors in anaphylaxis. I. Products of the major histocompatibility complex involved in alloantibody-induced mast cell activation. Immunology 38, 447–458 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalchau R., Fangmann J., Fabre J. W. (1992). Allorecognition of isolated, denatured chains of class I and class II major histocompatibility complex molecules. Evidence for an important role for indirect allorecognition in transplantation. Eur. J. Immunol. 22, 669–677 10.1002/eji.1830220309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dana M. R., Dai R., Zhu S., Yamada J., Streilein J. W. (1998). Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist suppresses Langerhans cell activity and promotes ocular immune privilege. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 39, 70–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dana M. R., Yamada J., Streilein J. W. (1997). Topical interleukin 1 receptor antagonist promotes corneal transplant survival. Transplantation 63, 1501–1507 10.1097/00007890-199705270-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. J., Gordon J. L., Gearing A. J., Pigott R., Woolf N., Katz D., Kyriakopoulos A. (1993). The expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PECAM, and E-selectin in human atherosclerosis. J. Pathol. 171, 223–229 10.1002/path.1711710311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries V. C., Elgueta R., Lee D. M., Noelle R. J. (2010). Mast cell protease 6 is required for allograft tolerance. Transplant. Proc. 42, 2759–2762 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries V. C., Noelle R. J. (2010). Mast cell mediators in tolerance. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 22, 643–648 10.1016/j.coi.2010.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries V. C., Wasiuk A., Bennett K. A., Benson M. J., Elgueta R., Waldschmidt T. J., Noelle R. J. (2009a). Mast cell degranulation breaks peripheral tolerance. Am. J. Transplant. 9, 2270–2280 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02675.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries V. C., Pino-Lagos K., Elgueta R., Noelle R. J. (2009b). The enigmatic role of mast cells in dominant tolerance. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 14, 332–337 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32832ce87a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekaris I. J., Yamada J. J., Streilein W. J., Dana R. M. (1999). Effect of topical interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) on corneal allograft survival in presensitized hosts. Curr. Eye Res. 19, 456–459 10.1076/ceyr.19.5.456.5292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir Y., Chen Y., Metz C., Renz H., Heeger P. S. (2003). Cardiac allograft rejection in the absence of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Transplantation 76, 244–247 10.1097/01.TP.0000067241.06918.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries M. E., Hosiawa K. A., Cameron C. M., Bosinger S. E., Persad D., Kelvin A. A., Coombs J. C., Wang H., Zhong R., Cameron M. J., Kelvin D. J. (2003). The role of chemokines and chemokine receptors in alloantigen-independent and alloantigen-dependent transplantation injury. Semin. Immunol. 15, 33–48 10.1016/S1044-5323(02)00126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhodapkar M. V., Steinman R. M., Krasovsky J., Munz C., Bhardwaj N. (2001). Antigen-specific inhibition of effector T cell function in humans after injection of immature dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 193, 233–238 10.1084/jem.193.2.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello C. A. (2009). Interleukin-1beta and the autoinflammatory diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 2467–2470 10.1056/NEJMe0811014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello C. A. (2011a). Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 117, 3720–3732 10.1182/blood-2010-07-273417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello C. A. (2011b). A clinical perspective of IL-1beta as the gatekeeper of inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 1203–1217 10.1002/eji.201141550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello C. A. (2011c). Blocking interleukin-1beta in acute and chronic autoinflammatory diseases. J. Intern. Med. 269, 16–28 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02313.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q., Louahed J., Vink A., Sullivan C. D., Messler C. J., Zhou Y., Haczku A., Huaux F., Arras M., Holroyd K. J., Renauld J. C., Levitt R. C., Nicolaides N. C. (1999). IL-9 induces chemokine expression in lung epithelial cells and baseline airway eosinophilia in transgenic mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 2130–2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmaagacli A. H., Koldehoff M., Hindahl H., Steckel N. K., Trenschel R., Peceny R., Ottinger H., Rath P. M., Ross R. S., Roggendorf M., Grosse-Wilde H., Beelen D. W. (2006). Mutations in innate immune system NOD2/CARD 15 and TLR-4 (Thr399Ile) genes influence the risk for severe acute graft-versus-host disease in patients who underwent an allogeneic transplantation. Transplantation 81, 247–254 10.1097/01.tp.0000188671.94646.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sawy T., Belperio J. A., Strieter R. M., Remick D. G., Fairchild R. L. (2005). Inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte-mediated graft damage synergizes with short-term costimulatory blockade to prevent cardiac allograft rejection. Circulation 112, 320–331 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.516708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger M. J., Deeb G. M., Bolling S. F., Ward P. A. (1997). Mediators of ischemia-reperfusion injury of rat lung. Am. J. Pathol. 150, 1773–1784 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fangmann J., Dalchau R., Fabre J. W. (1992). Rejection of skin allografts by indirect allorecognition of donor class I major histocompatibility complex peptides. J. Exp. Med. 175, 1521–1529 10.1084/jem.175.6.1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fangmann J., Dalchau R., Fabre J. W. (1993). Rejection of skin allografts by indirect allorecognition of donor class I major histocompatibility complex peptides. Transplant. Proc. 25, 183–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar C. A., Zhou W., Lin T., Sacks S. H. (2006). Local extravascular pool of C3 is a determinant of postischemic acute renal failure. FASEB J. 20, 217–226 10.1096/fj.05-4747com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure E., Equils O., Sieling P. A., Thomas L., Zhang F. X., Kirschning C. J., Polentarutti N., Muzio M., Arditi M. (2000). Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates NF-kappaB through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) in cultured human dermal endothelial cells. Differential expression of TLR-4 and TLR-2 in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 11058–11063 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon D. T., Carroll M. C. (2000). Regulation of B lymphocyte responses to foreign and self-antigens by the CD19/CD21 complex. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 393–422 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoseyeva E. V., Kishimoto K., Rolls H. K., Illigens B. M., Dong V. M., Valujskikh A., Heeger P. S., Sayegh M. H., Benichou G. (2002). Modulation of tissue-specific immune response to cardiac myosin can prolong survival of allogeneic heart transplants. J. Immunol. 169, 1168–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischereder M., Luckow B., Hocher B., Wüthrich R. P., Rothenpieler U., Schneeberger H., Panzer U., Stahl R. A., Hauser I. A., Budde K., Neumayer H., Krämer B. K., Land W., Schlöndorff D. (2001). CC chemokine receptor 5 and renal-transplant survival. Lancet 357, 1758–1761 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04898-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsthuber T., Yip H. C., Lehmann P. V. (1996). Induction of TH1 and TH2 immunity in neonatal mice. Science 271, 1728–1730 10.1126/science.271.5256.1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucras G., Coudert J. D., Coureau C., Guéry J. C. (2000). Dendritic cells prime in vivo alloreactive CD4 T lymphocytes toward type 2 cytokine- and TGF-beta-producing cells in the absence of CD8 T cell activation. J. Immunol. 165, 4994–5003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz S., Kelly R. A., Bourcier T. (2001). Role of TLR-2 in the activation of nuclear factor kappaB by oxidative stress in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5197–5203 10.1074/jbc.M009160200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz S., Kobzik L., Kim Y. D., Fukazawa R., Medzhitov R., Lee R. T., Kelly R. A. (1999). Toll4 (TLR4) expression in cardiac myocytes in normal and failing myocardium. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 271–280 10.1172/JCI6709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu F., Li Y., Qian S., Lu L., Chambers F., Starzl T. E., Fung J. J., Thomson A. W. (1996). Costimulatory molecule-deficient dendritic cell progenitors (MHC class II+, CD80dim, CD86-) prolong cardiac allograft survival in nonimmunosuppressed recipients. Transplantation 62, 659–665 10.1097/00007890-199609150-00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama S., Yoshino I., Yamaguchi M., Osoegawa A., Kameyama T., Tagawa T., Maehara Y. (2005). Blockage of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor expression by short interference RNA inhibited the rejection of an allogeneic tracheal graft. Transpl. Int. 18, 1203–1209 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay C., Lamacchia C., Palmer G. (2010). IL-1 pathways in inflammation and human diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6, 232–241 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Faia K. L., Csizmadia V., Smiley S. T., Soler D., King J. A., Danoff T. M., Hancock W. W. (2001). Beneficial effects of targeting CCR5 in allograft recipients. Transplantation 72, 1199–1205 10.1097/00007890-200110150-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Topham P. S., King J. A., Smiley S. T., Csizmadia V., Lu B., Gerard C. J., Hancock W. W. (2000). Targeting of the chemokine receptor CCR1 suppresses development of acute and chronic cardiac allograft rejection. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 35–44 10.1172/JCI8126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F., Manz M. G., Jung S., Sieweke M. H., Merad M., Ley K. (2010). Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science 327, 656–661 10.1126/science.1178331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M., Le Moine A., Braun M., Flamand V., Abramowicz D. (2001). A role for eosinophils in transplant rejection. Trends Immunol. 22, 247–251 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)01893-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein D. R. (2011). Inflammation and transplantation tolerance. Semin. Immunopathol. 33, 111–115 10.1007/s00281-011-0251-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein D. R., Tesar B. M., Akira S., Lakkis F. G. (2003). Critical role of the toll-like receptor signal adaptor protein MyD88 in acute allograft rejection. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1571–1578 10.1172/JCI17573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goriely S., Molle C., Nguyen M., Albarani V., Haddou N. O., Lin R., De Wit D., Flamand V., Willems F., Goldman M. (2006). Interferon regulatory factor 3 is involved in Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)- and TLR3-induced IL-12p35 gene activation. Blood 107, 1078–1084 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamerman J. A., Ogasawara K., Lanier L. L. (2005). NK cells in innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17, 29–35 10.1016/j.coi.2004.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock W. W., Gao W., Faia K. L., Csizmadia V. (2000a). Chemokines and their receptors in allograft rejection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 511–516 10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock W. W., Lu B., Gao W., Csizmadia V., Faia K., King J. A., Smiley S. T., Ling M., Gerard N. P., Gerard C. (2000b). Requirement of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 for acute allograft rejection. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1515–1520 10.1084/jem.192.10.1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock W. W., Sayegh M. H., Kwok C. A., Weiner H. L., Carpenter C. B. (1993). Oral, but not intravenous, alloantigen prevents accelerated allograft rejection by selective intragraft Th2 cell activation. Transplantation 55, 1112–1118 10.1097/00007890-199305000-00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada K., Ohira S., Isse K., Ozaki S., Zen Y., Sato Y., Nakanuma Y. (2003). Lipopolysaccharide activates nuclear factor-kappaB through toll-like receptors and related molecules in cultured biliary epithelial cells. Lab. Invest. 83, 1657–1667 10.1097/01.LAB.0000097190.56734.FE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart O. M., Athie-Morales V., O’Connor G. M., Gardiner C. M. (2005). TLR7/8-mediated activation of human NK cells results in accessory cell-dependent IFN-gamma production. J. Immunol. 175, 1636–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F., Means T. K., Luster A. D. (2003). Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood 102, 2660–2669 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayry P., Isoniemi H., Yilmaz S., Mennander A., Lemstrom K., Raisanen-Sokolowski A., Koskinen P., Ustinov J., Lautenschlager I., Taskinen E., Krogerus L., Aho P., Paavonen T. (1993). Chronic allograft rejection. Immunol. Rev. 134, 33–81 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1993.tb00639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera O. B., Golshayan D., Tibbott R., Salcido Ochoa F., James M. J., Marelli-Berg F. M., Lechler R. I. (2004). A novel pathway of alloantigen presentation by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 173, 4828–4837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holan V. (1988). Modulation of allotransplantation tolerance induction by interleukin-1 and interleukin-2. J. Immunogenet. 15, 331–337 10.1111/j.1744-313X.1988.tb00436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo K., Xu X. Y., Bucy R. P. (2000). Heterogeneity of T cell clones specific for a single indirect alloantigenic epitope (I-Ab/H-2Kd54-68) that mediate transplant rejection. Transplantation 70, 1516–1524 10.1097/00007890-200011270-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V., Rothenfusser S., Britsch S., Krug A., Jahrsdšrfer B., Giese T., Endres S., Hartmann G. (2002). Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1-10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Immunol. 168, 4531–4537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosenpud J. D., Mauck K. A., Hogan K. B. (1997). Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: IgM antibody responses to donor-specific vascular endothelium. Transplantation 63, 1602–1606 10.1097/00007890-199706150-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou G., Valujskikh A., Bayer J., Stavitsky A. B., Metz C., Heeger P. S. (2001). In vivo blockade of macrophage migration inhibitory factor prevents skin graft destruction after indirect allorecognition. Transplantation 72, 1890–1897 10.1097/00007890-200112270-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Kim L. J., Mealey R., Marsh H. C., Zhang Y., Tenner A. J., Connolly E. S., Pinsky D. J. (1999). Neuronal protection in stroke by an sLex-glycosylated complement inhibitory protein. Science 285, 595–599 10.1126/science.285.5427.595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson J. A., Riquelme P., Sawitzki B., Tomiuk S., Miqueu P., Zuhayra M., Oberg H. H., Pascher A., Lutzen U., Janssen U., Broichhausen C., Renders L., Thaiss F., Scheuermann E., Henze E., Volk H. D., Chatenoud L., Lechler R. I., Wood K. J., Kabelitz D., Schlitt H. J., Geissler E. K., Fandrich F. (2011). Cutting Edge: immunological consequences and trafficking of human regulatory macrophages administered to renal transplant recipients. J. Immunol. 187, 2072–2078 10.4049/jimmunol.1100762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]