Abstract

Background

Aphasia affects one third of acute stroke patients. There is a considerable spontaneous recovery in aphasia, but impaired communication ability remains a great problem. Communication difficulties are an impediment to rehabilitation. Early treatment of the language deficits leading to increased communication ability would improve rehabilitation. The aim of this study is to elucidate the efficacy of very early speech and language therapy (SLT) in acute stroke patients with aphasia.

Methods

A prospective, open, randomized, controlled trial was carried out with blinded endpoint evaluation of SLT, starting within 2 days of stroke onset and lasting for 21 days. 123 consecutive patients with acute, first-ever ischemic stroke and aphasia were randomized. The SLT treatment was Language Enrichment Therapy, and the aphasia tests used were the Norsk grunntest for afasi (NGA) and the Amsterdam-Nijmegen everyday language test (ANELT), both performed by speech pathologists, blinded for randomization.

Results

The primary outcome, as measured by ANELT at day 21, was 1.3 in the actively treated patient group and 1.2 among controls. NGA led to similar results in both groups. Patients with a higher level of education (>12 years) improved more on ANELT by day 21 than those with <12 years of education (3.4 vs. 1.0, respectively). In 34 patients in the treatment group and 19 in the control group improvement was ≥1 on ANELT (p < 0.05). There was no difference in the degree of aphasia at baseline except for fluency, which was higher in the group responding to treatment.

Conclusions

Very early intensive SLT with the Language Enrichment Therapy program over 21 days had no effect on the degree of aphasia in unselected acute aphasic stroke patients. In aphasic patients with more fluency, SLT resulted in a significant improvement as compared to controls. A higher educational level of >12 years was beneficial.

Key Words: Acute stroke, Aphasia, Language Enrichment Therapy, Speech and language therapy

Introduction

Aphasia affects one third of acute stroke patients [1, 2, 3]. In a majority of them, there is a considerable spontaneous recovery in aphasia during the first months after stroke onset, but half of the patients still have aphasia at 18 months, although in a milder form [1]. Aphasia secondary to intracerebral hemorrhage usually has a better recovery rate than aphasia due to cerebral infarcts of similar size [4]. The four major components of the classic aphasic syndromes are: comprehension, repetition, naming, and fluency. Comprehension usually shows earlier and complete recovery and is essential for basic communication. Nevertheless, persistent, even if less pronounced, impaired communication ability remains a great problem for the individual aphasic patient.

Speech and language therapy (SLT) in patients with aphasia has been recommended [5]. The most recent Cochrane systematic review suggests that SLT might be of some benefit in patients with aphasia following stroke [6]. This review included a study by Wertz et al. [7] which showed a small effect. However, almost all patients in these studies had chronic aphasia, i.e. with a duration of >3 months after stroke onset. Furthermore, intensive SLT over a short period of time proved to provide a better outcome than less intensive regimens over a longer period [6, 8]. New therapies like constraint-induced therapy, suppressing non-verbal communication in favor of verbal communication, and transcranial magnetic stimulation to cortical language areas have shown positive outcomes for a specific treatment target item, but the improvement could not be generalized to other language domains [9, 10].

Communication difficulties, especially comprehension deficit, are an impediment to rehabilitation. Very early mobilization is suggested to be one reason for the positive effect of stroke unit care. Early treatment of the language deficits leading to an increased communication ability would improve the whole rehabilitation process [11].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of very early SLT in acute aphasic stroke patients in a randomized controlled trial.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Design

This is a prospective, randomized, controlled trial with blinded endpoint evaluation of very early SLT for 21 days compared to a control group. Patients with acute, first-ever ischemic stroke and any degree of aphasia according to the Norsk grunntest for afasi (NGA) [12] and the possibility to start treatment within 2 days of stroke onset were eligible for inclusion. Consecutive, unselected acute stroke patients in our community-based Stroke Unit were screened for inclusion. To avoid imbalance in stroke severity between the two study groups, the patients were stratified according to the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) [13] (table 1). Exclusion criteria were rapid regression, dementia, drug abuse, and severe illness. Randomization was performed centrally by an independent statistician using consecutive sealed envelopes. Both groups were given information on aphasia, prognosis, and support. The patients were tested with aphasia tests, NIHSS, and Activities of Daily Living at baseline, after 3 weeks, and at 6 months. Educational level was assessed as more or less than 12 years at school, which is equivalent to a high-school degree. More details of the design of the study have been described earlier [14]. The Regional Ethics Committee approved the study, and patients or relatives gave their written informed consent.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Training (n = 62) | Control (n = 61) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (range) | 76 (38–94) | 79 (39–94) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 33 (58) | 23 (41) |

| Living alone, n (%) | 28 (46) | 29 (48) |

| Education >12 years, n (%) | 21 (42) | 20 (37) |

| Delay to inclusion, days | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| Stratification group, n | ||

| NIHSS<10 | 34 | 33 |

| NIHSS 11–19 | 13 | 13 |

| NIHSS >20 | 15 | 15 |

| NIHSS points | 9 (4–19) | 8 (5–19) |

| ADL index points | 25 (5–85) | 45 (5–85) |

| TOAST stroke types, n | ||

| Large vessel | 9 | 14 |

| Cardiac embolic | 26 | 26 |

| Unknown | 27 | 21 |

| OCSP stroke types, n | ||

| TACI | 7 | 10 |

| PACI | 55 | 51 |

| ANELT | 1 (0–1.4) | 1 (0–1.4) |

| Coeff | 10.5 (4–33) | 13 (4–33) |

| Fluency | 31 (1.5–47) | 33 (1.5–49) |

| Comprehension | 10 (4–22) | 9 (4–20) |

| Repetition | 1 (0–11) | 0 (0–7) |

| Naming | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–7) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 26 (41) | 25 (41) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 35 (56) | 33 (54) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 8 (13) | 11 (18) |

| History of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 14 (23) | 3 (5) |

| Angina pectoris, n (%) | 10 (16) | 9 (15) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 37 (69) | 27 (50) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 15 (25) | 8 (13) |

| Peripherial artery disease, n (%) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 9 (15) | 7 (11) |

| Carotic stenosis (>50%), n (%) | 5 (15) | 7 (18) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 143 (130–160) | 150 (140–165) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 80 (74–86) | 80 (70–85) |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 76 (64–85) | 76 (64–80) |

| Blood glucose, mmol/l | 6.6 (5.8–7.3) | 6.4 (5.8–7.3) |

| S-creatinine, (μmol/1 | 86 (74–100) | 88 (77–107) |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/l | 4.9 (4.1–5.8) | 4.8 (4.1–5.3) |

| LDL-cholesterol, mmol/l | 3.1 (2.4–3.9) | 2.8 (2.3–3.4) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/1 | 6 (4–18) | 9 (4–15) |

Data are presented as median values and quartiles, if not otherwise stated. ADL = Activities of Daily Living, Barthel Index; TOAST = Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment [18]; OCSP = Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project [19]; TACI = total anterior circulation infarct; PACI = partial anterior circulation infarct; LDL = low density lipoprotein.

Aphasia Tests

Two tests for aphasia were used. A short adjusted version of NGA was employed, which is a valid and reliable standard test to assess the degree and the type of aphasia by measuring fluency, comprehension, repetition, and naming [12]. The sum of the scores of comprehension, repetition, and naming yields the aphasia coefficient (Coeff), which is equivalent to the degree. Coeff has a range of 0–59, where a value of 59 is normal. Percentile values give each patient's raw score for the variables naming, repetition, and comprehension in relation to the score of the whole group of these aphasic subjects. The relation between the percentile value of three parameters and fluency, measured as words per minute, estimated from spontaneous speech gives the type of aphasia. Fluency was tape recorded. The second test for aphasia used was the Amsterdam-Nijmegen everyday language test (ANELT), a functional test, though verbal [15]. ANELT is a valid, reliable test for aphasia. The testing procedure with ANELT was also tape recorded. ANELT measures the degree of aphasia on a 1–5 point scale, where 5 equals normal. A score of 0 was given when the patient, due to severe aphasia, was incapable of taking instructions and/or producing an answer. The NGA and ANELT tests have been described in detail elsewhere [16]. All tests for aphasia were performed by three speech pathologists who had been trained together and blinded as to the randomization. The tapes were assessed by yet another speech pathologist with great experience with these tests and unaware of randomization and any of the previous test results.

Therapy

The SLT treatment used was Language Enrichment Therapy (LET) [17]. The LET program focuses on exercise in comprehension and to some extent in naming in a hierarchic edified program. This is the most commonly used SLT in the clinical setting in Scandinavia (with the exception of computerized programs). The LET program describes exactly how to do the exercises and is therefore easily reproducible. Nothing in the LET program resembles the ANELT test. LET was carried out by five co-trained speech pathologists. The therapy consisted of 45-min long sessions every weekday over 21 days. Treatment per protocol in the active treatment arm was defined as at least 600 min of therapy (maximum 720 min), while in the control group no SLT was given during the same period. All patients were encouraged to communicate with relatives and staff.

Following the 21-day intervention period, all patients could receive SLT at the discretion of the responsible physician. However, the number of subsequent SLT treatment sessions performed was reported and counted.

Statistical Methods

As previously described, the primary outcome was the difference in the degree of aphasia between the two study groups measured by the ANELT score at day 21. The secondary measure of outcome was the difference in the recovery rate in Coeff between the two groups at day 21 (Diff Coeff) [14]. A predetermined improvement on the ANELT scale of ≥1 at day 21 was considered clinically relevant, whereas 0.5 was considered too small to be clinically relevant [14]. The power was set at 90% and the two-sided level of significance at 5%. With 52 patients in each group, a difference of at least 0.75 in ANELT, considered clinically worthwhile, was secured. The primary analysis was conducted in accordance with intention-to-treat.

Data are presented as median values and quartiles, if not otherwise stated. Contingency tables were evaluated by the χ2 test. Statistical comparisons between groups were made by the Wilcoxon signed rank test. For multivariate regression analyses, multivariate analysis of variance was used. All analyses were carried out with the JMP, version 7.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

General Results

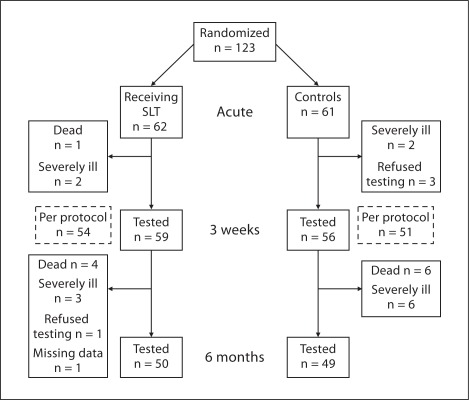

We randomized 123 aphasic patients of which 114 (93%) completed the study and could be tested on day 21 (fig. 1). Follow-up at 6 months could be performed in 99 patients (80%). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the study groups, except for a history of myocardial infarction, which was more frequent in the intervention group (table 1). At the follow-up at 6 months, 5 patients in the intervention group and 6 in the control group had died. Five patients in each group had recurrent stroke. All recurrent strokes occurred beyond the 3 weeks of intervention.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for randomized patients.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome in the whole group as measured by ANELT by day 21 was 1.3 among the SLT-treated patients and 1.2 among the controls (table 2). The Diff Coeff was 8.5 in the SLT group and 9 in the control group. Also, per protocol analyses of ANELT by day 21 and for Diff Coeff revealed no statistical difference between the two study groups (table 2).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes

| Training group | Control group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | |||

| ANELT by day 21, intention-to-treat, n | 59 | 55 | |

| Median | 1.3 (1–4.1) | 1.2 (0–3.6) | 0.37 |

| ANELT by day 21, per protocol, n | 54 | 49 | |

| Median | 1.5 (1–4.1) | 1.0 (0–3.6) | 0.16 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Difference in coefficient at baseline and day 21, intention-to-treat, n | 58 | 56 | |

| Median | 8.5 (1–17) | 9 (3.3–16.8) | 0.86 |

| Difference in coefficient at baseline and day 21, per protocol, n | 53 | 48 | |

| Median | 9 (1.5–17.5) | 8.5 (2.3–16) | 0.62 |

| Follow-up at 6 months | |||

| ANELT, n | 50 | 49 | |

| Median | 1.8 (1–4.6) | 3 (1–4.6) | 0.49 |

| Coefficient, n | 50 | 49 | |

| Median | 40 (25–57) | 49 (17–58) | 0.62 |

Data are presented as median values and quartiles.

Patients with a higher level of education (>12 years) improved more in ANELT by day 21 than those with <12 years of education [3.4 (1.0–4.8) vs. 1.0 (1.0–2.7); p < 0.01]. Diff Coeff improved more in patients with >12 years of education than in those with <12 years of education [13 (8–26) vs. 8 (1–16); p < 0.01].

Higher values of ANELT, Coeff, fluency, and comprehension at baseline had a positive effect on ANELT by day 21 (p < 0.01), while worse neurological performance as indicated by higher NIHSS values at baseline and longer delay to inclusion had a negative effect on ANELT by day 21 (p < 0.01) and on Diff Coeff (p < 0.05).

A multivariate analysis including baseline ANELT, Coeff, fluency, and NIHSS at baseline, as well as age, gender, delay to inclusion, intervention group, and level of education, confirmed that initial ANELT and length of education had an independent, significant impact on the primary outcome (i.e. ANELT by day 21). For secondary outcome (i.e. Diff Coeff), the impact of the initial NIHSS and educational level were significant.

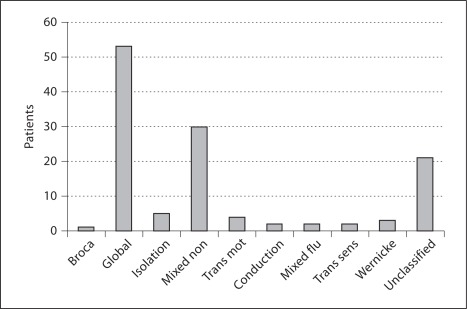

The types of aphasia are shown in figure 2. There were no differences in aphasia types between the two groups. Only 9 patients had a fluent type of aphasia at baseline, and there were no differences in fluent/non-fluent types of aphasia between the two groups. Best outcome according to ANELT at 3 weeks was seen in transcortical sensory aphasia, followed by isolation, conduction, and Wernicke type of aphasia. Patients with global aphasia had the poorest outcome.

Fig. 2.

Types of aphasia at baseline. Mixed non = Mixed non-fluent, Trans mot = transcortical motor, Mixed flu = mixed fluent, Trans sens = transcortical sensory.

Follow-Up at 6 Months

At 6 months, ANELT and Coeff were similar in the two study groups (table 2). The number of non-study SLT sessions after day 21 was 15 (4–38) in the treatment group and 10 (5–20) in the control group (p = 0.3).

ANELT at 6 months of follow-up was 4.5 (1.9–5.0) among those with an education of >12 years and 1.5 (1.0–3.6) among those with less education (p < 0.01). For Coeff at 6 months, the corresponding results were 57 (39–59) and 39 (17–55) (p < 0.01).

Subgroup Analyses, Responders versus Non-Responders

These analyses were performed post hoc. Results in the 53 aphasic stroke patients who improved ≥1 on ANELT (i.e. an improvement which was predetermined to be clinically relevant; responders) are presented in table 3. The 34 responders in the SLT treatment group were compared to those 25 patients who improved <1 on ANELT (non-responders). NIHSS at baseline was lower in the responder group than in the non-responder group [5 (2–12) vs. 11 (7–20); p < 0.01]. Aphasia tests showed no difference at baseline except for fluency, which was 37 (30–64) words/min in the responder group and 8 (1.5–30) words/min in the non-responder group (p < 0.001). There were no differences in types of aphasia. The responders improved in all three parts of the NGA (comprehension, naming, and repetition), as compared to the non-responders (all p < 0.01). At 6 months of follow-up, a difference in ANELT remained between responders and non-responders [2.7 (1.2–4.9) vs. 1.1 (0.8–1.6); p < 0.01]. Among those with a fluency of >30 words/min (n = 51), more patients improved >1 on ANELT in the intervention group than among controls (18 vs. 6 patients; p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Effects of SLT at day 21 according to ANELT

| SLT group (n=59) | Control group (n=55) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with a difference in ANELT | |||

| ≥1 from baseline to day 21 | 34 responders | 19 | <0.01 |

| <1 from baseline to day 21 | 25 non-responders | 36 |

Discussion

This randomized controlled trial revealed that very early SLT with the LET program does not affect the primary and secondary outcomes of the degree of aphasia in unselected patients with aphasia after first-ever ischemic stroke. The study had an adequate statistical power, and the tests used for primary and secondary outcomes are robust and measure the total degree of aphasia. Only ischemic stroke patients were included, since patients with intracerebral hemorrhage are often more affected in the acute stage and have a higher mortality rate. Compared to our previous findings in aphasic patients [1, 18], the subjects in the present study were more affected regarding the severity of the stroke and the degree of aphasia. As there is a rapid early spontaneous improvement, this can be due to the much shorter time from symptom onset in the present study [1, 18]. The participants in the current study compare well to the average patient with aphasia very early after an acute ischemic stroke. Accordingly, we regard the results as externally valid.

The potential for improvement is greatest for those patients with the most severe degree of aphasia. The possibility to reach the best results, however, is greatest for patients with mild aphasia. The most important factors for improvement are the initial degree of aphasia and the degree of neurological deficit at baseline [1].

Comprehension is the base for communication and a prerequisite to assimilate rehabilitation. Thus, we used the well-defined and easily reproducible LET program, which first of all examines comprehension [17]. For patients with good comprehension, the LET program can concentrate more on naming exercises.

In patients with more fluency, SLT showed significant improvement at day 21, resulting in a milder degree of aphasia; these favorable effects remained at 6 months. The aphasic patients with more fluency and less paresis (probably reflecting a posterior lesion) seemed to be those who benefited most from SLT. However, these findings were performed post hoc and must be interpreted with caution. Further studies need to verify these observations.

In this study, the educational level had an independent impact on the recovery of aphasia both in short- and long-term outcome. There was no difference in stroke severity or degree of aphasia at baseline between those with an education of more or less than 12 years. Others have found no correlation between educational level and functional outcome for aphasic patients [19]. A possible explanation of our findings is that patients with a higher educational level may have a greater potential for learning during the recovery period and that their premorbid personality may reflect a greater learning capacity.

Conclusions

Very early intensive SLT with the LET program does not improve outcome in unselected acute ischemic stroke patients with aphasia. An educational level of more than 12 years was beneficial. However, a post hoc analysis showed that a group of patients with more fluency seemed to improve significantly, primarily due to comprehension exercise, with the possible benefit effect lasting for 6 months after stroke onset. Thus, very early intensive SLT cannot generally be recommended in acute aphasic patients. The findings of improvement in patients with more fluency warrant further investigation and evaluation of the efficacy of alternative treatments.

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Peter Bornstein, Skene, Sweden, for the Swedish version of NGA and ANELT, and for fruitful suggestions and advice. The study was supported by the Stockholm County Council Foundation (Expo-95), AFA Insurances, Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, and Karolinska Institute.

References

- 1.Laska AC, Hellblom A, Murray V, Kahan T, von Arbin M. Aphasia in acute stroke and relation to outcome. J Intern Med. 2001;249:413–422. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engelter ST, Gostynski M, Papa S, et al. Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke. 2006;37:1379–1384. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221815.64093.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bejot Y, Rouaud O, Jacquin A, Osseby GV, Durier J, Manckoundia P, Pfitzenmeyer P, Moreau T, Giroud M. Stroke in the very old: incidence, risk factors, clinical features, outcomes and access to resources – a 22-year population-based study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:111–121. doi: 10.1159/000262306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basso A. Prognostic factors in aphasia. Aphasiology. 1992;6:337–348. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cicerone K, Dahlberg C, Malec J, Langenbahn D, Felicetti T, Kneipp S, Ellmo W, Kalmar K, Giacino J, Harley P, Laatsch L, Morse P, Catanese J. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: updated review of the literature from 1998 through 2002. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1681–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly H, Brady MC, Enderby P. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD000425. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wertz RT, Weiss DG, Aten JL, Brookshire RH, Garcia-Bunuel L, Holland AL, Kurtzke JF, LaPointe LL, Milianti FJ, Brannegan R, Greenbaum H, Marshall RC, Vogel D, Carter J, Barnes NS, Goodman R. Comparison of clinic, home, and deferred language treatment for aphasia. A Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:653–658. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520070011008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhogal SK, Teasell R, Speechley M. Intensity of aphasia therapy, impact on recovery. Stroke. 2003;34:987–993. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000062343.64383.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meinzer M, Djundja D, Barthel G, Elbert T, Rockstroh B. Long-term stability of improved language functions in chronic aphasia after constraint-induced aphasia therapy. Stroke. 2005;36:1462–1466. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000169941.29831.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naeser MA, Martin PI, Nicholas M, Baker EH, Seekins H, Kobayashi M, et al. Improved picture naming in chronic aphasia after TMS to part of right Broca's area: an open-protocol study. Brain Lang. 2005;93:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paolucci S, Matano A, Bragoni M, Coiro P, De Angelis D, Fusco FR, Morelli D, Pratesi L, Venturiero V, Bureca I. Rehabilitation of left-damaged ischemic stroke patients: the role of comprehension language deficits. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20:400–406. doi: 10.1159/000088671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinvang I. Aphasia and Brain Organisation. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brott T, Adams HP, Olinger C, Marler JR, Barsan WG, Biller J, Spilker J, Holleran R, Eberle R, Hertzberg V, Rorick M, Moomaw CJ, Walker M. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20:864–870. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laska AC, Kahan T, Hellblom A, Murray V, von Arbin M. Design and methods of a randomized controlled trial on early speech and language therapy in patients with acute stroke and aphasia. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2008;15:256–261. doi: 10.1310/tsr1503-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blomert L, Kean ML, Koster C, Schokker J. Amsterdam-Nijmegen everyday language test: construction, reliability and validity. Aphasiology. 1994;8:381–407. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laska AC, Bartfai A, Hellblom A, Murray V, Kahan T. Clinical and prognostic properties of standardized and functional aphasia assessments. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39:387–392. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salonen L. Sarno M, Höök O. Aphasia, Assessment and Treatment. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell; 1980. The language enriched individual therapy program for aphasic patients. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laska AC, von Arbin M, Kahan T, Hellblom A, Murray V. Long-term antidepressant treatment with moclobemide for aphasia in acute stroke patients: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:125–132. doi: 10.1159/000083256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazar RM, Speizer AE, Festa JR, Krakauer JW, Marshall RS. Variability in language recovery after fist-time stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:530–534. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.122457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]