Abstract

Atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), also known as atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), is an endogenous and potent hypotensive hormone that elicits natriuretic, diuretic, vasorelaxant, and anti-proliferative effects, which are important in the control of blood pressure and cardiovascular events. One principal locus involved in the regulatory action of ANP and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A (GC-A/NPRA). Studies on ANP, BNP, and their receptor, GC-A/NPRA, have greatly increased our knowledge of the control of hypertension and cardiovascular disorders. Cellular, biochemical, and molecular studies have helped to delineate the receptor function and signaling mechanisms of NPRA. Gene-targeted and transgenic mouse models have advanced our understanding of the importance of ANP, BNP, and GC-A/NPRA in disease states at the molecular level. Importantly, ANP and BNP are used as critical markers of cardiac events; however, their therapeutic potentials for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, heart failure, and stroke have just begun to be realized. We are now just at the initial stage of molecular therapeutics and pharmacogenomic advancement of the natriuretic peptides. More investigations should be undertaken and ongoing ones be extended in this important field.

Keywords: atrial natriuretic factor/peptide, guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A, gene-targeting, high blood pressure, cardiac hypertrophy

1. Introduction

The pioneering discovery by (de Bold et al., 1981) that atrial extracts contain natriuretic and diuretic activity, led them to identify and characterize atrial natriuretic factor/peptide (ANF/ANP). The natriuretic peptides (NPs) are a group of hormones that have critical functions in the control of renal, cardiovascular, endocrine, and skeletal homeostasis (Brenner et al., 1990; Drewett & Garbers, 1994; McGrath et al., 2005; Pandey, 2005a, 2008). ANP, the first described member of the natriuretic peptide hormone family, elicits natriuretic, diuretic, and vasorelaxant effects, all of which are directed to the reduction of body fluid and the maintenance of blood pressure homeostasis (McGrath et al., 2005). Subsequently, two other members, B-type, or brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and C-type, natriuretic peptide (CNP), were identified (LaPointe, 2005; Schulz, 2005). A family of endogenous peptide hormones, including ANP, BNP, CNP, and urodilatin, are considered to have an integral role in hypertension and cardiovascular regulation (Brenner et al., 1990; de Bold, 1985; Levin et al., 1998; Pandey, 2005a). Interestingly, it has been suggested that the natriuretic peptides not only regulate blood pressure, but also maintain antagonistic action to renin and angiotensin II (ANG II), exert an anti-mitogenic effect, and inhibit myocardial hypertrophy, as well as acting in endothelial cell function, cartilage growth, immunity, and mitochondrial biogenesis (Garbers et al., 2006; Gardner, 2003; Pandey, 2008; Richards, 2007). ANP and BNP are also increasingly used to screen and diagnose cardiac etiologies of shortness of breath and congestive heart failure in emergency conditions (Vasan et al., 2002).

Three subtypes of natriuretic peptide receptors have been identified: NP receptor-A (NPRA), NP receptor-B (NPRB), and NP receptor-C (NPRC). Interestingly, both ANP and BNP activate NPRA, which produces second messenger cGMP in response to hormone binding. CNP activates NPRB, which also produces cGMP, but all three natriuretic peptides indiscriminately bind to NPRC, which does not produce cGMP (Koller & Goddel, 1992). The discovery of structurally related natriuretic peptides indicated that the physiological control of blood pressure and body fluid homeostasis is complex. A combination of biochemical, molecular, and pharmacological aspects of NPs and their prototype receptors has demonstrated hallmark functions of physiological and pathophysiological importance, including renal, cardiovascular, neuronal, skeletal, and immunological effects in health and disease (Kuhn, 2005; Pandey, 2005a; Vollmer, 2005).

Receptor guanylyl cyclase-A (GC-A), also designated as GC-A/NPRA, is a principal locus involved in the regulatory action of ANP and BNP (Lucas et al., 2000; Pandey, 2005a; Tremblay et al., 2002). Gaining insight into the intricacies of ANP/NPRA signaling is pivotal for understanding both receptor biology and the disease state arising from abnormal hormone-receptor interaction. It has been postulated that binding of ANP to the extracellular domain of the receptor causes a conformational change, thereby transmitting the signal to the intracellular domain, which then generates cGMP (Pandey & Singh, 1990). Recent works have focused on elucidating, at the molecular level, the nature and mode of functioning of GC-A/NPRA. Both cultured cells in vitro and gene-targeted (gene-knockout and gene-duplication) mouse models in vivo have been used to gain understanding of the normal and abnormal control of cellular and physiological processes. Although there has been a great deal of appreciation of the functional roles of natriuretic peptides and their cognate receptors in renal, cardiovascular, endocrine, and skeletal homeostasis, in-depth research is still needed to fully delineate their potential molecular targets in diseases states. It is expected that studies on the natriuretic peptides and their receptors will yield new therapeutic targets and novel loci for the control and treatment of hypertension and cardiovascular disorders.

2. Background of Natriuretic Peptides

ANP, the first member of the natriuretic peptide hormone family, is primarily synthesized in the heart atrium. The primary structure deduced from cDNAs suggested that ANP is synthesized as the 152-amino acid prepro-ANP molecule, which contains sequences of active peptides in its carboxyl-terminal region, and that the major form of circulatory ANP is a 28-residue circulating hormone (Flynn et al., 1983; Maki et al., 1984). Different lengths of sequences of ANP were synthesized for studies of the structure-activity relationship. It was found that a 17-residue ring conformation of ANP molecule with a disulfide-bonded loop is essential for its activities (Brenner et al., 1990). Both BNP and CNP also exhibit biochemical and structural similarities to ANP but each of the three peptides is derived from a separate gene (Rosenzweig & Seidman, 1991). Although ANP, BNP, and CNP have homologous structure, they bind to specific cell-surface receptors and elicit discrete biological functions (Brenner et al., 1990; Koller et al., 1992).

BNP is synthesized as a 134-amino acid preprohormone, which yields a 108-amino acid prohormone molecule. Processing of the proBNP molecule yields a 75-residue amino-terminal-BNP and a 32-residue biologically active circulating BNP (Seilhamer et al., 1989; Sudoh et al., 1988). CNP, which is thought to be synthesized as a 103-amino acid prohormone, is cleaved to a 53-residue peptide by the protease furin, and subsequently is processed to yield a 22-amino-acid biologically active molecule (C. Wu et al., 2003). The amino acid sequence of ANP is almost identical across the mammalian species except for position 10, which is isoleucine in rats, mice, and rabbits. However, in humans, dogs, and bovines, ANP has methionine in this position. BNP and CNP were both isolated from porcine brain extracts on the basis of their potent relaxant effects (Sudoh et al., 1988, 1990). Soon it was established that BNP is predominantly synthesized and secreted from the heart (Philips et al., 1991). CNP, which is localized in the central nervous system and endothelial cells, is considered to be a noncirculatory hormone (Suga, Nakao, Kishimoto, et al., 1992). Like ANP, both BNP and CNP are synthesized from large precursor molecules. The mature bioactive peptides contain a 17-residue loop bridged by an intramolecular disulfide bond (Fig.1). In essence, 11 of these amino acids are identical in ANP, BNP, and CNP; however, the amino- and carboxyl-terminus vary in length and composition. Among the species, ANP and BNP exhibit the most variability in primary structure, while CNP is highly conserved across the species. In addition, a 32-amino acid peptide, urodilatin (URO) was discovered, which is present in urine (Feller et al., 1990; Schulz-Knappe et al., 1988). URO is not detected in the circulation and appears to be a unique intrarenal natriuretic peptide with unexplored physiological functions (Saxenhofer et al., 1990). D-type natriuretic peptide (DNP) is an additional member in the NP hormone family, which was initially isolated from venom of the green mamba, Dendroaspis angusticeps. as a 38-amino acid peptide molecule (Schweitz et al., 1992). Biochemical, immunohistochemical, and molecular studies have suggested that three specific natriuretic peptides and their three distinct receptor subtypes have widespread tissue and cell distributions, indicating pleotropic actions at both systemic and local levels (Table 1).

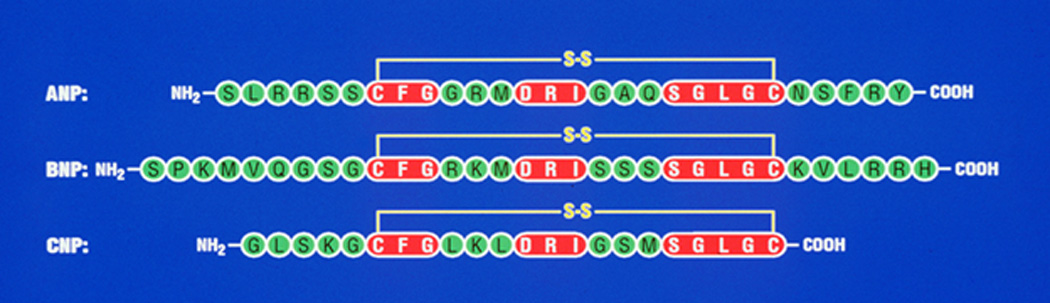

Figure 1. Comparison of amino acid sequence of the natriuretic peptide hormone family.

Comparison of amino-acid sequence of human ANP, BNP, and CNP with conserved amino acid residues, which are represented by shaded boxes. The lines between two cysteine residues in ANP, BNP, and CNP indicate a 17-amino acid disulfide bridge, which is essential for the biological activity of three natriuretic peptide hormones. ANF, atrial natriuretic peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; and CNP, C-type natriuretic peptide.

Table 1.

The cell and tissue distributions and gene-knockout phenotypes of natriuretic peptides and their receptors.

| Ligand/ Receptor |

Cell distribution | Tissue distribution | Gene-knockout phenotype in mice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nppa | Myocytes, Leydig cells, granulosa-lutean cells | Atrium, ventricle, brain, kidney, testis, ovary | High blood pressure, hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy |

| Nppb | Myocytes, ventricular cells | Atrium, ventricle, brain | Ventricular fibrosis, skeletal abnormalities, vascular complications |

| Nppc | Endothelial Cells | Vascular endothelium, aorta, brain, heart, testis | Inhibition of long bone growth, dwarfism, abnormal chondrocyte differentiation |

| NPRA/GC-A | Renal epithelial and mesangial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, Leydig cells, granulosa cells, fibroblasts, Neuroblastoma, LLCPk-1, MDCK cells | Kidney, adrenal glands, brain, heart, liver, lung, olfactory, ovary, pituitary gland, placenta, testis, thymus, vascular beds, liver, ileum, and other tissues | High blood pressure, hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, inflammation, volume overload, reduced testosterone |

| NPRB/GC-B | Vascular smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, chondrocytes | Adrenal glands, brain, cartilage, fibroblast, heart, lung, ovary, pituitary gland, placenta, testis, thymus, vascular beds, and other tissues | Dwarfism, decreased adiposity, female sterility, seizures, vascular complication |

| NPRC | Vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, mesangial cells, fibroblasts | Kidney, heart, brain liver, vascular bed, intestine, and other tissues | Bone deformation, skeletal over-growth, long bone overgrowth |

The abbreviation used are; GC-A/NPRA, guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A; GC-B/NPRB, guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-B; NPRC, natriuretic peptide clearance receptor; ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CNP, C-type natriuretic peptide.

ANP is usually characterized as having a fast clearance rate in the circulation; its half-life ranges from 0.5 to 4.0 min in experimental animals (Nakao et al., 1986; Ruskoaho, 1992; Yandle et al., 1986). However, the half-life of ANP in human subjects ranges between approximately 2 and 2.5 min (Nakao et al., 1986). The clearance of BNP in humans occurs with both short and long half-life, including approximately 3–4 min and 20–23 min, respectively (Holmes et al., 1993; Mukoyama et al., 1991). On the other hand, CNP has been reported to have a half-life of 2–3 min in humans and approximately 1.6 min in experimental animals (Charles et al., 1995; Hunt et al., 1994). Interestingly, the design and synthesis of chimeric natriuretic peptides has produced biologically active molecules, which represent single-chemical entities with combined structural and functional properties of different natriuretic peptides (Lisy et al., 2008). The chimeric natriuretic peptides exert the actions of at least two different natriuretic peptide molecules and often reduce undesirable adverse effects. One such chimeric molecule is CD-NP, produced by a fusion of 22-amino acid CNP with the 15-amino-acid C-terminus of DNP. Thus, CD-NP has vasorelaxant properties, effectively reduces cardiac volume overload, and exerts renoprotective effects. At the same time, the 15-amino-acid C-terminus of DNP is highly resistant to neutral endopeptidase (NEP), making CD-NP a more stable molecule than are naturally occurring natriuretic peptides (Lee et al., 2009; Lisy et al., 2008).

3. Primary Structure and Sequence Domains of NPRA

GC-A/NPRA has been cloned and sequenced from rat brain (Chinkers et al., 1989), human placenta (Chang et al., 1989), and mouse testis (Pandey & Singh, 1990). Three different sub-types of NP receptors (NPRA, NPRB, and NPRC) constitute the natriuretic peptide receptor family; however, these receptors are variable in their ligand specificity and signal transduction activity. Both GC-A/NPRA and GC-B/NPRB are 135-kDa transmembrane proteins; ligand binding to these receptors generates the second messenger cGMP (Garbers, 1992; Khurana & Pandey, 1993; Koller et al., 1992; Pandey & Singh, 1990; Schulz et al., 1989). NPRC lacks the intracellular catalytic domain and has been termed a natriuretic peptide clearance receptor (Fuller et al., 1988). Both ANP and BNP selectively stimulate NPRA, whereas CNP primarily activates NPRB. All three NPs indiscriminately bind to NPRC (Khurana & Pandey, 1993; Koller et al., 1991; Suga, Nakao, Itoh, et al., 1992). It has been suggested that in vivo ANP binding to its receptor requires chloride, which exerts a chloride-dependent feedback-control mechanism on receptor function (Misono, 2000).

The general topological structure of NPRA is consistent with that in the GC receptor family, containing at least four distinct regions: an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a single transmembrane spanning region, an intracellular protein kinase-like homology domain (protein-KHD), and a GC catalytic domain (Fig 2). NPRB has an overall domain structure similar to that of NPRA, with binding selectivity for CNP (Schulz, 2005; Schulz et al., 1989). The dominant form of the natriuretic peptide receptors is NPRA, which is found in peripheral organs and mediates most of the known actions of ANP and BNP. Using a homology-based cDNA library screening system, additional members of the GC-receptor family have also been identified, but their specific ligands and/or activators are not yet known (Drewett & Garbers, 1994; Garbers, 1992; Pandey, 2008). The intracellular region of NPRA is divided into two domains: the protein-KHD is the 280-amino acid region immediately following the transmembrane domain distal to this is the GC catalytic domain of the receptor. More than 80% of the conserved amino acid residues that have been found in all protein kinases are considered to be present in NPRA (Hunter, 1995). It has been suggested that the GC catalytic domain of NPRA has been consists of a 250-amino acid region at the carboxyl-terminal end of the molecule. Deletion of the carboxyl-terminal region of NPRA resulted in a protein that bound to ANP but did not contain GC activity (Koller et al., 1992; Pandey & Kanungo, 1993; Pandey et al., 2000).

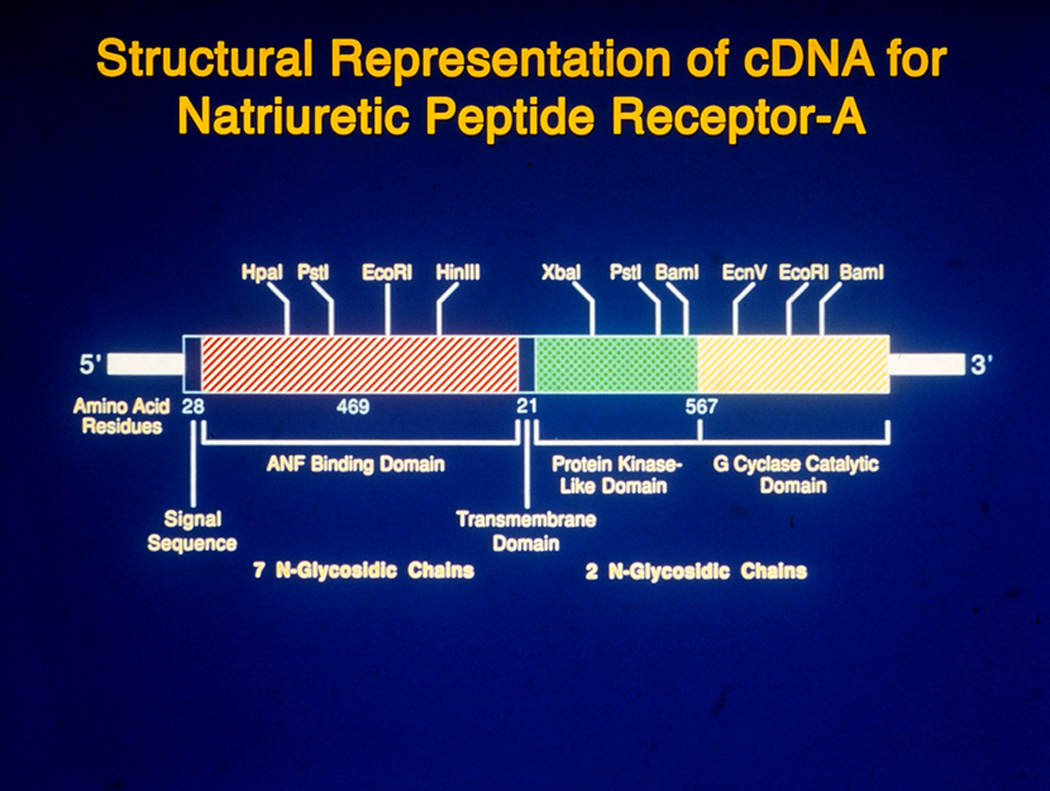

Figure 2. Diagrammatic representation of the structural features of guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A cDNA sequence.

The hutched portions of the bar represent the coding region of murine cDNA sequence and the solid areas of the bar represent the untranslated regions at the 5'- and 3'- ends, respectively. The major restriction sites are shown above the hatched bar, representating the coding region of cDNA sequence. The brackets at the bottom of hatched portions of coding region, indicate the extracellular ANP binding domain (469 amino acids) and intracellular protein kinase-like domain as well as guanylyl cyclase catalytic domain (567 amino acids). The solid portions at beginning of coding region represents 28 amino acid signal sequence and in the middle of the coding region it represents 21 amino acid transmembrane domain. Seven glycosylation sites are present in the extracellular domain and two glycosylation sites are present in the intracellular domain of the receptor.

Modeling studies based on the crystal structure of the adenylyl cyclase II C2 (AC II C2) homodimer (Liu et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1997) predicted that the active site of guanylyl and adenylyl cyclases are closely related (Sunahara et al., 1998; Tucker et al., 1998). Based on those predictions, the GC catalytic active site of murine NPRA includes a 31-amino-acid sequence (974–1,004 residues) at the carboxyl-terminal end of the receptor molecule. The crystal structure of the soluble guanylyl cyclase (CYG12) catalytic domain from unicellular green algae, Chlamydomonas renharditi, has been reported to contain a 188-amino acid catalytic core (Winger et al., 2008). Similarly, a 202-amino-acid catalytic core of membrane-bound guanylyl cyclase (Cya2) has also been shown to be present in prokaryotic cyanobacterium, Synechocysts (Rauch et al., 2008). Those findings, for the first time, showed the structure of the catalytic domain of any guanylyl cyclase after the adenylyl cyclase structure, which was reported almost ten years before the crystal structures of GYG12 and Cya2. It is predicted that guanylyl cyclase and all known adenylyl cyclases belong to the class-III nucleotide cyclase family of receptors and share a high sequence similarity. Based on the comparisons of amino acid sequence, the CYG12 seems to be homologous with mammalian soluble cyclases. However, Cya2 is homologous with particulate guanylyl cyclases.

The transmembrane GC-A/NPRA contains a single cyclase catalytic active site per polypeptide molecule; however, based on modeling data, two polypeptide chains are required to activate the functional receptor molecule (van den Akker et al., 2000). The transmembrane GC receptors are predicted to function as homodimers (De Lean et al., 2003; Misono et al., 2005). It has been suggested that the dimerization region of NPRA is located between the KHD and GC catalytic domains. IT is predicted to form an amphipathic alpha helix structure (Misono et al., 2005). NPRB is mainly localized in the brain and vascular tissues, and is thought to mediate the actions of CNP in vascular beds and the central nervous system (Schulz, 2005). The third member of the natriuretic peptide receptor family, NPRC, consists of a large extracellular domain of 496-amino acids, a single transmembrane domain, and a very short 37-amino-acid cytoplasmic tail that bears no homology to any other known receptor protein domain.

4. Internalization and Down-Regulation of NPRA

The specific binding of 125I-ANP to plasma membranes of various types of cells and tissues indicates that NPRA is a high-affinity receptor species with a kd value of 1×10−10 – 1×10−9 M thag is present in different cell types (Table 2). NPRA is internalized and redistributed into subcellular compartments in a ligand-dependent manner (Pandey, 1993, 2001, 2002, 2005b; Pandey et al., 1986; Pandey et al., 1988; Rathinavelu & Isom, 1991). The ligand-dependent endocytosis and sequestration of NPRA involves a series of sequential sorting steps through which ligand-receptor complexes are eventually degraded, receptor recycles back to the plasma membrane, and intact ligand is released into the cell exterior (Pandey, 1993, 2002; Pandey et al., 2000). The recycling of endocytosed receptor to the plasma membrane and the release of intact ANP into the cell exterior occur simultaneously, with the processes leading to degradation of the majority of ligand-receptor complexes into lysosomes with a half-life of 7.5 min (Pandey, 1993; Pandey et al., 2000; Pandey et al., 2005). Concurrently, this process lead to degradation of the majority of ligand-receptor complexes into lysosomes (Pandey et al., 2000; Pandey et al., 2005). These findings provided direct evidence that treatment of cells with unlabeled ANP accelerates the disappearance of surface receptors, indicating that ANP-dependent down-regulation of GC-A/NPRA involves internalization of the receptor (Pandey et al., 2005).

Table 2.

ANP-dependent binding parameters of GC-A/NPRA and intracellular accumulation of cGMP in different cell types.

| Cells | GC-A/NPRA binding parameters | Intracellular cGMP (fold stimulation) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| kd value (Molar) |

Bmax (receptor site/cell) |

||

| Recombinant 293 cells | 1 × 10−10 – 1 × 10−9 | 1.2 × 106 | 1,500 |

| MA-10 cells | 1 × 10−10 – 1 × 10−9 | 1 × 106 | 1,200 |

| Glomerulosa cells | 1 × 10−10 – 1 × 10−9 | 2 × 105 | 50 |

| Primary Ledig cells | 1 × 10−11 – 1 × 10−10 | 0. 5 × 105 | 40 |

| Granulosa cells | 1 × 10−11 – 1 × 10−10 | 0.5 × 105 | 30 |

| MDCK cells | 1 × 10−11 – 1 × 10−10 | 0.5 × 105 | 25 |

| N4TG1 cells | 1 × 10−11 – 1 × 10−10 | 0.5 × 105 | 20 |

| RTASM cells | 1 × 10−11 – 1 × 10−10 | 0.25 × 105 | 15 |

kd, dissociation constant; Bmax, receptor density; MA-10 cells, Leydig tumor cells; MDCK cells, Maiden -Darby kidney epithelial cells; N4TG1 cells, neuroblastoma cells; RTASM, rat thoracic aortic smooth muscle cells.

Early studies found that the GDAY sequence motif in the carboxyl terminal domain of GC-A/NPRA serves as an internalization signal for endocytosis (Pandey et al., 2005). The residues Gly920 and Tyr923 are the important elements in the GDAY internalization signal motif of NPRA. However, it is thought that the residue Asp921 provides an acidic environment for efficient signaling of the GDAY motif during the internalization process. The mutation of Asp921 to alanine did not have a major effect on receptor internalization, but did significantly attenuate the recycling of internalized receptors to plasma membranes (Pandey et al., 2005). The mutations of Gly920 and Tyr923 to alanine inhibited the internalization of NPRA, although these residues had no discernible effect on the recycling process. It was suggested that the tyrosine-based sequence modulates the early internalization of NPRA, whereas Asp921 in the GDAY motif mediates recycling or later sorting of the receptor. Thus, two overlapping motifs within the GDAY sequence in the carboxyl-terminal domain of NPRA exert different but specific effects on endocytosis and trafficking of the receptor. Internalization and sequestration of hormone receptors have been implicated as having important roles in desensitization and down-regulation processes (Barak et al., 1994). Furthermore, it has been shown that guanylyl cyclase-B/natriuretic peptide receptor-B (GC-B/NPRB) is internalized and recycled (Brackmann et al., 2005). The trafficking of NPRB occurs ligand-dependently in response to C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) stimulation. The trafficking of NPRB has been suggested to involve a clathrin-dependent mechanism. Similarly, the internalization of NPRA involves clathrin-dependent pathways (Somanna et al., 2007).

mRNA levels of NPRA are regulated by glucocorticoids (Nuglozeh et al., 1997), transforming growth factor-β (Fujio et al., 1994), chorionic gonadotropin (Gutkowska et al., 1999), ANG II (Arise & Pandey, 2006; Garg & Pandey, 2003), and retinoic acid (P. Kumar et al., 2010). Endogenous transcription factors such as Ets-1 and p300 exert remarkable stimulating effects on Npr1 (coding for NPRA) gene transcription and expression (P. Kumar et al., 2009; P. Kumar & Pandey, 2009). At the protein level, ANG II inhibits the GC activity of NPRA (Arise & Pandey, 2006; Bottari et al., 1992; Haneda et al., 1991). Similarly, at the receptor level, NPRA is down-regulated by ANP or 8-bromo-cGMP (Liang et al., 2001; Pandey, 2010; Pandey et al., 2000; Pandey et al., 2005; Pandey et al., 2002). However, a complete understanding of the mechanisms of internalization and down-regulation of NPRA in physiological and pathological states remains to be established.

5. Transmembrane Signaling Mechanisms of NPRA

ANP markedly increases cGMP in target tissues in a dose-related manner (Pandey et al., 2002; Pandey et al., 1988). The production of cGMP is mediated by ligand binding to the extracellular domain of receptor, which probably allosterically regulates increased specific activity of the cytoplasmic guanylyl cyclase catalytic domain (Burczynska et al., 2007; Garbers & Lowe, 1994; Pandey, 2008; Pandey et al., 2000). The nonhydrolyzable analogs of ATP mimicked ANP effect and suggested that ATP can allosterically regulate the GC catalytic activity of NPRA (Chinkers & Garbers, 1989; Kurose et al., 1987; R. K. Sharma, 2002, 2010). Previous findings suggested that under natural conditions the protein-KHD acts as a negative regulator of the catalytic moiety of NPRA. Initially, this model was the standard in explaining the signal transduction mechanism of GC-coupled natriuretic peptide receptors (Foster & Garbers, 1998). However, the model has not been supported by the studies of other investigators, suggesting that deletion of the protein-KHD did not increase basal GC activity. Nevertheless, ATP was predicted to be obligatory for the transduction activities of both NPRA and NPRB (Burczynska et al., 2007; Duda et al., 1993; R. K. Sharma, 2010). It has been suggested that NPRA exists in the phosphorylated form in the basal state and that the binding of ANP causes a decrease in phosphate content, as well as a reduction in ANP-dependent GC activity (Potter & Garbers, 1994). This apparent mechanism of desensitization of NPRA is in contrast to that of many other cell-surface receptors, which appear to be desensitized by phosphorylation (Huganir & Greengard, 1990; Kurose & Lefkowitz, 1994; Langlet et al., 2005). It has also been suggested that GC activity may, in fact, be regulated by receptor phosphorylation (Ballermann et al., 1988; Duda & Sharma, 1990; Larose et al., 1992; Pandey, 1989).

Earlier, it was suggested that glycosylation is essential for the ligand binding activity of NPRA (Fenrick et al., 1997; Fenrick et al., 1996; Lowe & Fendly, 1992). The glycosylation sites in GC-coupled receptors appear to be important for proper folding and stability of the receptor proteins (Heim et al., 1996; Koller et al., 1993; Lowe & Fendly, 1992). However, the exact role of glycosylation sites in ligand binding of the receptor has not yet been defined. It should be noted that there is no appreciable conservation of the precise position of glycosylation sites within members of the GC receptor family. Overall, the signaling of ANP, BNP, and their receptors leads to combined physiological functions, which together provide renoprotection, cardioprotection, and vascular protection (Fig. 3). The binding of ANP and BNP to GC-A/NPRA increases intracellular second messenger cGMP, which stimulates three known cGMP effector molecules: cGMP-dependent protein kinases (PKGs), cGMP-dependent phosphodiesterases (PDEs), and cGMP-dependent ion channels (Kaupp & Seifert, 2002; Maurice et al., 2003; Pandey, 2008; Pfeifer et al., 1998; Reinhart et al., 2006; Rybalkin et al., 2003; Schlossmann et al., 2005).

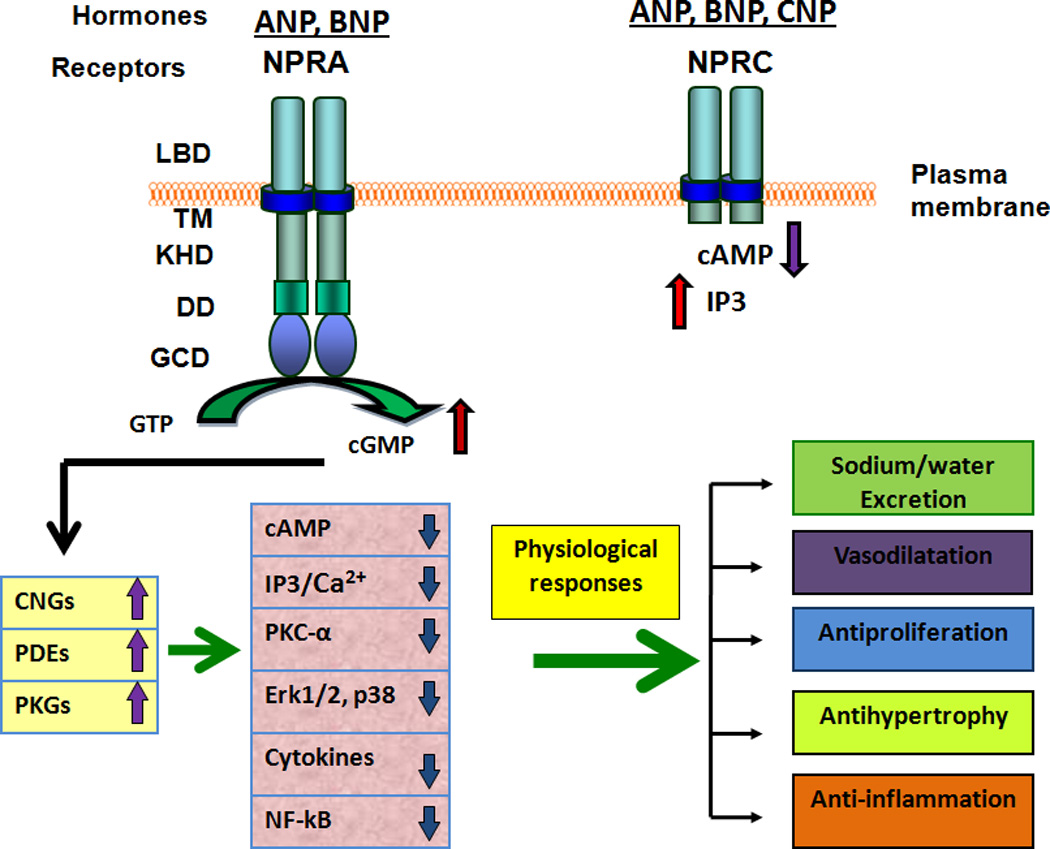

Figure 3. Representation of hormone specificity and physiological and pathophysiological function(s) of GC-A/NPRA.

After ligand-binding, GC-A/NPRA is shown to generate second messenger cGMP from the hydrolysis of GTP. An increased level of intracellular cGMP stimulates and activates three known cGMP effecter molecules namely; cGMP-dependent protein kinases (PKGs), cGMP-dependent phosphodiesterases (PDEs), and cGMP-dependent ion-gated channels (CNGs). The cGMP-dependent signaling may antagonize a number of pathways including; intracellular Ca2+ release, IP3 formation, activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and production of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (Il-6). The resulting cascade can mimic ANP/NPRA/cGMP-dependent responses in both physiological and pathophysiological environments. The activation of NPRC may lead to a decrease in cAMP levels and an increase in IP3 production. The extracellular ligand binding domain (LBD), transmembrane region (TM), and intracellular protein kinase-like homology domain (KHD) and guanylyl cyclase catalytic domain (GCD) of GC-A/NPRA are shown. DD, represents the dimerization domain of NPRA. The ligand binding domain, transmembrane region, and small intracellular tail of NPRC are also indicated.

6. Regulation of Blood Pressure Homeostasis by NPRA

A combination of hemodynamic effects and tubular transport processes are responsible for ANP/NPRA-induced natriuresis and diuresis. ANP/NPRA signaling promotes the excretion of salt and water and enhances the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and renal plasma flow (RPF) in the kidneys (Brenner et al., 1990; Levin et al., 1998; Pandey, 2008; Shi et al., 2003). ANP action in the kidney includes the inner medullary collecting duct, glomerulus, and mesangial cells (Cermak et al., 1996; Light et al., 1989; Nonoguchi et al., 1987; Pandey et al., 2000). It is thought that ANP/NPRA signaling exerts both direct and indirect effects on tubules, including the proximal tubules, as well as cortical and innermedullary collecting ducts (Brenner et al., 1990; Sonnenberg et al., 1986). In large measure, ANP induces diuresis by increasing GFR, which is hemodynamic in nature (Bianchi et al., 1986; Cogan et al., 1986; Fried et al., 1986). However, it has been suggested that ANP-induced natriuresis is also caused by direct inhibition of tubular transport processes, independent of the alterations in GFR (Sonnenberg et al., 1986). Interestingly, it is thought that ANP-induced natriuresis and diuresis favor a combination of hemodynamic and tubular effects (Meyer et al., 1997). The increased production of cGMP at ANP concentrations affecting renal function correlates with the effects of dibutyryl-cGMP, which prevents mesangial cell contraction in response to ANG II effects (Appel, 1992). ANP markedly lowers renin secretion and plasma renin concentrations (Burnett et al., 1984; Kurtz et al., 1986; Shi et al., 2001). The function of ANP in mediating renal and vascular effects was also demonstrated with selective NPRA antagonists to eliminate the effect of ANP (R. Kumar et al., 1997; von Geldern et al., 1990). The intrarenal actions of ANP/NPRA signaling at various nephron sites exerts a combined effect, leading to increased excretion of sodium and water and enhanced renal hemodynamic functions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Intrarenal action of ANP/NPRA signaling at different nephron sites in the kidney.

| Nephron Sites | Biological Parameters | Signaling action |

|---|---|---|

| Glomerulus | Glomerular filtration rate | Increase |

| Renal artery | Renal blood flow | Increase |

| Proximal tubule | Na+ and water transport | Decrease |

| Proximal tubule | Angiotensin II-induced Na+ absorption | Decrease |

| Inner medullary collecting duct | Amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel | Decrease |

| Inner medullary collecting duct | Na+ -K+-2Cl− co-transporter | Decrease |

| Cortical collecting duct | Vasopressin-induced hydrosmosis | Decrease |

| Juxtaglomerulus | Renin secretion | Decrease |

| Renal medulla | Solute concentration | Decrease |

| Vasorecta | Blood flow, hydraulic pressure | Increase |

The ANP/NPRA action in the kidney includes multiple pathways to achieve the renal function. These include; 1) increase in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and renal blood flow (RBF), 2) decrease in sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubules and collecting ducts, 3) decrease in hydrosmosis in cortical collecting duct, 4) decrease solute concentration in medulla, 5) decrease Na+-K+-2cl− co-transporter in the inner medullary collecting duct, 6) decrease renin secretion in juxtaglomerular cells, and 7) increase in blood flow and hydraulic pressure.

ANP increases cGMP in intact aortic segments and cultured vascular smooth-muscle cells (VSMCs). The correlative evidence of ANP-induced cGMP accumulation has suggested its role in dilatory responses in cultured VSMCs (Cao et al., 1995; R. Kumar et al., 1997; G. D. Sharma et al., 2002). ANP, as well as cGMP analogs, reduce agonist-dependent increases in cytosolic Ca2+ and inositol trisphosphate (Khurana & Pandey, 1996; Lincoln et al., 2001). ANP acts as a growth suppressor in a variety of tissue types including vasculature, kidney, heart, and neurons (Cao et al., 1995; Levin & Frank, 1991; Pandey et al., 2000; Pandey et al., 2005; G. D. Sharma et al., 2002). ANP inhibits mitogen-activation of fibroblasts (Chrisman & Garbers, 1999) and induces cardiac myocyte apoptosis (C. F. Wu et al., 1997). However, the cellular mechanisms involved in the effects of ANP are not yet completely understood. ANP is considered to be a direct smooth-muscle relaxant and a potent regulator of cell growth and proliferation. The anti-growth paradigm could potentially work through negative regulation of the activities of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Pandey et al., 2000; G. D. Sharma et al., 2002). ANP has been reported to antagonize growth-promoting effects in target cells, but there is controversy about the mechanism of the anti-growth paradigm of ANP and the involvement of specific ANP receptor subtypes (NPRA and/or NPRC) in target cells (Anand-Srivastava, 2005; Hutchinson et al., 1997; Pandey et al., 2000; Prins et al., 1996; Rose & Giles, 2008).

ANP/NPRA signaling lowers blood volume and blood pressure by releasing salt and water through the kidneys, as well as vasorelaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Various genetically engineered mouse models have been produced to delineate the functions of ANP, BNP, and NPRA in physiological and phathophysiological conditions of hypertension and cardiovascular complications. The genetic defects that reduce the signaling of ANP/NPRA can be considered candidate contributors to essential hypertension and cardiovascular homeostasis (Pandey, 2008). John et al. (1995) (John et al., 1995), using ANP-deficient mice, demonstrated that a defect in proANP synthesis can increase blood pressure and cause hypertension. Thus, genetic mouse models with disruption of the Nppa gene, which codes for proANP, have provided strong support for the central role of ANP in regulating hypertension. The blood pressure of Nppa homozygous null mutant (Nppa−/−) mice was elevated by 8–10 mmHg when they were fed standard or intermediate salt diets. Heterozygous (Nppa+/−) mice on a standard salt diet showed a normal amount of ANP and normal blood pressure. However, Nppa+/− mice on a high-salt diet were hypertensive; their blood pressure was elevated 27 mmHg. These early findings indicated that mutation in the Nppa allele can lead to salt-sensitive hypertension even when the plasma ANP level is not significantly decreased. Transgenic mice overexpressing ANP developed sustained hypotension; their arterial pressure (25–30 mmHg) was lower than that of their nontransgenic siblings (Melo et al., 1999; Steinhelper et al., 1990). Somatic delivery of the ANP gene in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) induced a sustained reduction in systemic blood pressure (Lin et al., 1995). Overexpression of ANP in hypertensive mice lowered systolic blood pressure, suggesting the use of ANP gene therapy for the treatment of human hypertension (Schillinger et al., 2005). Functional alterations of the Nppa promoter are linked to cardiac hypertrophy in the progeny of rats generated by crossing Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and Wistar Kyoto-derived hypertensive (WKYH) rats (Deschepper et al., 2001).

Disruption of the Npr1 gene increases blood pressure by 35–40 mmHg in Npr1−/− (0-copy) mice as compared with wild-type (Npr1+/+ or 2-copy) mice (Oliver et al., 1997; Shi et al., 2001; Vellaichamy et al., 2005). In contrast, increased expression of NPRA in gene-duplicated (3-copy and 4-copy) mutant mice significantly reduces blood pressure, corresponding to the increasing number of Npr1 gene copies (Oliver et al., 1998; Pandey et al., 1999; Shi et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2007). Our studies have examined the possible mechanisms mediating the responses of varying numbers of Npr1 gene copies by determining RPF, GFR, urine flow, and sodium excretion after blood volume expansion in a gene-dose-dependent manner (Shi et al., 2003). During the volume expansion with whole blood infusion, the mean arterial pressure increased in Npr1 gene-disrupted (0-copy), wild-type (2-copy), and gene-duplicated (4-copy; Npr1++/++) mice. However, mean arterial pressures were always significantly higher in gene-disrupted mice and significantly lower in gene-duplicated mice than in wild-type mice. The GFR was 25%–35% lower in 0-copy mice and 35%–45% higher in 4-copy mice than in control mice (Shi et al., 2003). Similarly, RPF was 25%–30% lower in 0-copy mice and 45%–70% higher in 4-copy mice than RPF levels in 2-copy control mice. Homozygous null mutant mice also retained significantly higher levels of sodium and water than did wild-type and gene-duplicated mice. These findings demonstrated that the ANP/NPRA signaling axis is primarily responsible for mediating the renal hemodynamic and sodium excretory responses to intravascular blood volume expansion. The complete absence of NPRA in mice also leads to altered renin, ANG II, and aldosterone (ALDO) levels (Oliver et al., 1997; Schreier et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2001; Shi et al., 2003; Vellaichamy et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2007). Our recent studies have shown that disruption of the Npr1 gene in mice provokes kidney fibrosis, remodeling, and significant expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines (Das et al., 2010). Significant increases in plasma creatinine concentrations and urinary albumin excretion, together with a reduced creatinine clearance rate, suggested renal insufficiency in Npr1 null mutant mice.

Interestingly, ANP/NPRA signaling inhibits ALDO synthesis and release from adrenal glomerulosa cells (Atarashi et al., 1984; Brenner et al., 1990; Shi et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2007), which may account for its natriuretic and diuretic effects in the kidney. Furthermore, studies with Npr1 gene-disrupted mice suggested that at birth, the absence of NPRA allows greater renin and ANG II levels and increased renin mRNA expression than occurs in wild-type mice (Shi et al., 2001). However, at 3–16 weeks of age, circulating renin and ANG II levels were dramatically decreased in Npr1 null mutant mice as compared with wild-type mice. The decrease in renin activity in adult Npr1 null mutant mice is likely due to progressive elevation of arterial pressure leading to inhibition of renin synthesis and release from kidney juxtaglomerular cells (Shi et al., 2003). On the other hand, adrenal renin content and renin mRNA levels, as well as ANG II and ALDO concentrations, were elevated in adult homozygous null mutant mice as compared with wild-type mice (Shi et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2007). Indeed, ANP/NPRA signaling appears to oppose almost all actions of ANG II in both physiological and disease states (Pandey, 2005a).

Initially, it was suggested that the blood pressure of homozygous Npr1 null mutant mice remained elevated and unchanged in response to either minimal or high-salt diets (Lopez et al., 1995). In contrast, we and others have reported that disruption of the Npr1 gene results in chronic elevation of blood pressure in mice fed high-salt diets (Oliver et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 2007). However, adrenal ANG II and ALDO levels were decreased in Npr1 gene-duplicated mice fed a high salt-diet, whereas a low-salt diet stimulated adrenal ANG II and ALDO levels in both gene-disrupted and gene-duplicated mice. That diet suppressed adrenal ANG II and ALDO levels in Npr1 gene-disrupted mice and wild-type mice, but not in Npr1 gene-duplicated (3-copy and 4-copy) mice. Our findings indicated that NPRA signaling has a protective effect against high salt in Npr1 gene-duplicated mice as compared with Npr1 gene-disrupted mice (Zhao et al., 2007). Indeed, more studies are needed to clarify the relationship between salt-sensitivity and blood pressure in Npr1 gene-disrupted and gene-targeted mice.

7. Regulation of Cardiac Homeostasis by NPRA

Both ANP and BNP appear to reduce the preload and after oad of the heart. Expression of these peptide hormones is significantly increased in proportion to the severity of cardiac remolding and dysfunction in both humans and animal models (Chen & Burnett, 1999; Ellmers et al., 2007; Nakao et al., 1996; Pandey, 2008; Reinhart et al., 2006). The concentrations of both ANP and BNP are markedly increased in the cardiac tissues and plasma of patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) (Chen & Burnett, 1999; Felker et al., 2006; Reinhart et al., 2006). In humans, high plasma levels of ANP/BNP tend to predict heart failure (Chen & Burnett, 1999; Tsutamoto et al., 1993). In patients with severe CHF, concentrations of both ANP and BNP increase, but the BNP concentration rises 10- to 50-fold higher than does the increase in ANP (Mukoyama et al., 1991). ANP and BNP genes are overexpressed in hypertrophied hearts, suggesting that the autocrine and/or paracrine effects of natriuretic peptides predominate and might endogenously protect against maladaptive pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Ellmers et al., 2007; Felker et al., 2006; Knowles et al., 2001; Vellaichamy et al., 2005; Vellaichamy et al., 2007; Xue et al., 2008). Plasma levels of both ANP and BNP are markedly elevated under the pathophysiological conditions of cardiac dysfunction, including diastolic dysfunction, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and cardiac hypertrophy (Felker et al., 2006; Jaffe et al., 2006; Reinhart et al., 2006; See & de Lemos, 2006; Vellaichamy et al., 2005). There are indications that ventricular expression of ANP and BNP is more closely associated with local cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis than are plasma ANP levels and systemic blood pressures (Vellaichamy et al., 2005; Vellaichamy et al., 2007). Because the half-life of BNP is greater than that of ANP, diagnostic evaluations of natriuretic peptides have favored BNP, which is considered to be an important indicator in CHF patients (Reinhart et al., 2006). However, NT-proBNP seems to be a stronger indicator of the risk of cardiovascular events (Doust et al., 2005; Khan et al., 2006). The expression of Nppa and Nppb (coding for proBNP) genes is greatly stimulated in hypertrophied hearts, suggesting that autocrine and/or paracrine effects of NPs predominate and serve as an endogenous protective mechanisms against maladaptive cardiac events (Knowles et al., 2001; Vellaichamy et al., 2005; Zahabi et al., 2003).

Disruption of Npr1 in mice increases their cardiac mass and greatly increases the incidence of cardiac hypertrophy (Ellmers et al., 2002; Nakanishi et al., 2005; Oliver et al., 1997; Scott et al., 2009; Vellaichamy et al., 2005; Vellaichamy et al., 2007). Other studies have demonstrated that Npr1 gene disruption in mice not only increases the expression of hypertrophic marker genes, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinases, but also enhances activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB), which seem to be associated with cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling (Ellmers et al., 2007; Vellaichamy et al., 2005; Vellaichamy et al., 2007). Interestingly, the expression of sarcolemal or endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase-2a (SERCA-2a) is progressively decreased in the hypertrophied hearts of Npr1 null mutant mice (Vellaichamy et al., 2005). Expression of both angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and ANG II receptor type A (AT1a) is greatly increased in Npr1 null mutant mice compared with that in wild-type control mice (Vellaichamy et al., 2007). NPRA signaling antagonizes ANG II and AT1a receptor-mediated cardiac remodeling and provides an endogenous protective mechanism in failing hearts (Kilic et al., 2007; Li et al., 2002; Vellaichamy et al., 2007). Arteries from smooth muscle and endothelial cell-specific Npr1 knockout mice exhibited significant arterial hypertension (Sabrane et al., 2005). Moreover, the Npr1 gene is a potential locus for susceptibility to atherosclerosis (Alexander et al., 2003). Introduction of the NPRA transgene did not alter blood pressure or heart rate in transgenic mice, but did reduce the size of cardiac myocytes, while both ANP mRNA and peptide levels were significantly decreased (Kishimoto et al., 2001). When the Npr1 gene in cardiomyocytes was selectively inactivated by homologous lox/Cre-mediated recombination, mice with cardiomyocyte-restricted deletion of Npr1 exhibited mild cardiac hypertrophy but increased ANP levels (Holtwick et al., 2003).

Levels of circulating ANP and BNP are dramatically elevated in the initial stage of myocardial infarction (Morita et al., 1993; Phillips et al., 1989; Tomoda, 1988). In experimental myocardial infarction in Npr1 gene-disrupted mice, levels of both ANP and BNP were markedly elevated in Npr1−/− mice, which had a higher incidence of heart failure and significantly greater mortalitty than did wild-type mice (Nakanishi et al., 2005). (Yamahara et al., 2003) found that activation of ANP/cGMP signaling enhanced recovery of vascular blood flow. (Park et al., 2008) found that intraperitoneal injection of recombinant ANP (carperitide) accelerated the recovery of blood flow with increasing capillary density in ischemic conditions. Laser Doppler perfusion imaging experiments have shown that the recovery of blood flow in ischemic limbs is significantly inhibited in Npr1 gene-disrupted mice as compared with wild-type mice (Tokudome et al., 2009). Moreover, vascular regeneration in response to critical hind limb ischemia was severely impaired in Npr1 gene-disrupted mice (Kuhn et al., 2009). The physiological and pathophysiological functions of NPRA signaling are associated with various organ systems, including the kidneys, heart, lungs, central nervous system, gonads, adrenal glands, and vasculature (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of physiological and pathophysiological effects associated with the activation of GC-A/NPRA signaling in different target organs.

| Organs | Functional parameters |

Effect of GC-A/NPRA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | |||

| Natriuresis | ↑ | Increase | |

| Diuresis | ↑ | Increase | |

| Hypertrophy | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Remodeling | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Renin release | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Heart | |||

| Cardiomyocyte size | ↓ | Decrease | |

| LVDS | ↓ | Decrease | |

| LVDD | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Fractional shortening | ↑ | Increase | |

| Cardiac hypertrophy | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Fibroblast growth | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Lung | |||

| Smooth muscle relaxation | ↑ | Increase | |

| CNS | |||

| Thrust | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Sympathetic activity | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Vasculature | |||

| Smooth muscle relaxation | ↑ | Increase | |

| Endothelial permeability | ↑ | Increase | |

| Intravascular volume | ↓ | Decrease | |

| Gonads | |||

| Testosterone | ↑ | Increase | |

| Estradiol | ↑ | Increase | |

| Adrenal Glands | |||

| Aldosterone | ↓ | Decrease |

GC-A/NPRA, guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A; LVDS, Lift ventricular dimension systolic; LVDD, left ventricular dimension diastolic; and CNS, central nervous system. Up arrow indicates increase and down arrow indicates decrease of functional parameters.

8. Human Genetics of ANP and NPRA

It has been suggested that patients with monogenic forms of hypertension have rare genetic mutations (Ji et al., 2008; Lifton et al., 2001). Recent genetic and clinical studies have indicated an association of Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 gene polymorphisms with hypertension and cardiovascular events in humans (Newton-Cheh et al., 2009; Rubattu et al., 2006; Webber & Marder, 2008; Xue et al., 2008). Various pathways, including natriuretic peptides, RAAS, and the adrenergic system, are considered to regulate blood pressure. Nevertheless, the genetic determinants in these pathways contributing to inter-individual differences in blood pressure have been linked with only the natriuretic peptide system (Newton-Cheh et al., 2009). A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at Nppa-Nppb locus was associated with increased concentrations of plasma ANP and BNP and lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures. An association between Nppa promoter polymorphism (-C66UG) and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) has been demonstrated in Italian hypertensive patients, indicating that individuals carrying a copy of the Nppa variant allele exhibit marked decreases in proANP levels associated with LVH (Rubattu et al., 2006). Interestingly, an association between a microsatellite marker in Npr1 promoter and LVH has indicated that ANP/NPRA signaling contributes to ventricular remodeling in essential hypertension in humans (Rubattu et al., 2006). The relationship between high blood pressure and cardiovascular risk is continuous; thus, in the absence of ANP/NPRA signaling, even small increases in blood pressure confer excessive and detrimental effects. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that a substantial heritability of blood pressure and cardiovascular risks indicates a role for genetic factors (Levy et al., 2000). (Nakayama et al., 2000) found that a single allele mutation in the human Npr1 gene decreased the receptor expression by almost 70%. They also found that the single allele mutation was associated with increased susceptibility to hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Interestingly, it has been shown that in humans a “4-minus” haplotype in the 3’-untranslated region of the Npr1 gene is associated with an increased level of N-terminal-proBNP (NT-proBNP) (Webber & Marder, 2008). The “4-minus” haplotype constitutes 4C repeats at nucleotide position 14,319 and a 4-bp deletion of AGAA at nucleotide position 14,649 of the Npr1 gene. It has been speculated that the causal mechanism for high blood pressure could be Npr1 mRNA instability, leading to decreased translational products of receptor protein (Knowles et al., 2003). This could elicit a feedback mechanism whereby diminished function of NPRA/cGMP signaling caused by the defect in the Npr1 gene provokes compensatory enhanced expression and release of ANP and/or BNP. Taken together, a positive association exists among Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 gene polymorphisms, essential hypertension, and left ventricular mass index. It is predicted that human subjects carrying certain variants of Nppa, Nppb, and/or Npr1 gene are particularly susceptible to hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and congestive heart failure. Furthermore, it has been reported that allelic variations in Nppa, Nppb, and the Npr1 gene in humans are associated with a family history of hypertension and cardiovascular disorders, including myocardial infarction, left ventricular mass index, and septal wall thickness. Studies are needed to characterize the most functionally significant markers of Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 variants in a large human population.

9. Future Perspectives

In the past thirty years, a large body of literature has provided a unique perspective for delineating cellular, biochemical, and genetic information on the regulation and function of ANP, BNP, and NPRA in relation to hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Recent studies have used molecular approaches to delineate the genomic functions affected by decreasing and/or increasing numbers of Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 gene copies as achieved by gene targeting, such as gene disruption (knockout) and/or duplication (gene dosage) in mice. Comparative analyses of the biochemical and physiological phenotypes of Npr1 gene-disrupted and gene-duplicated mutant mice have enormous potential to answer fundamental questions about the importance of ANP/NPRA signaling in disease states by genetically altering Npr1 gene copy numbers and product levels in intact animals in vivo with otherwise identical genetic background.

Future studies will lead to a better understanding of the genetic basis of Npr1 gene function in regulating high blood pressure, strokes, and cardiovascular events. Currently, ANP and BNP are considered to be markers of congestive heart failure; however, we still need to determine their therapeutic potentials for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac hypertrophy, congestive heart failure, and stroke. It also remains to be seen whether the continuing research on ANP, BNP, and GC-A/NPRA can facilitate the rapid clinical use of these agents to treat patients with high blood pressure and cardiovascular disorders. The results of future investigations of natriuretic peptides and their receptors should be of great value in resolving the genetic complexities related to hypertension and heart failure. Overall, future studies should be directed to provide a unique perspective for delineating the genetic and molecular basis of Npr1 gene expression, regulation, and function in both normal and disease states. The resulting knowledge should yield new therapeutic targets for treating hypertension and preventing hypertension-related cardiovascular diseases and other pathological conditions.

Acknowledgements

I thank the members of my laboratory for their contributions and my wife Kamala Pandey for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. My special thanks are due to Dr. Bharat B. Aggarwal, Department of Experimental Therapeutics and Cytokine Research Laboratory, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX; and to Dr. Susan L. Hamilton, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX for providing their facilities during our displacement period due to Hurricane Katrina. The research work in the author's laboratory was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants (HL-57531 and HL-62147).

References

- Alexander MR, Knowles JW, Nishikimi T, Maeda N. Increased atherosclerosis and smooth muscle cell hypertrophy in natriuretic peptide receptor A−/−apolipoprotein E−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(6):1077–1082. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000071702.45741.2E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand-Srivastava MB. Natriuretic peptide receptor-C signaling and regulation. Peptides. 2005;26(6):1044–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel RG. Growth-regulatory properties of atrial natriuretic factor. Am J Physiol. 1992;262(6 Pt 2):F911–F918. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.6.F911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arise KK, Pandey KN. Inhibition and down-regulation of gene transcription and guanylyl cyclase activity of NPRA by angiotensin II involving protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349(1):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atarashi K, Mulrow PJ, Franco-Saenz R, Snajdar R, Rapp J. Inhibition of aldosterone production by an atrial extract. Science. 1984;224(4652):992–994. doi: 10.1126/science.6326267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballermann BJ, Marala RB, Sharma RK. Characterization and regulation by protein kinase C of renal glomerular atrial natriuretic peptide receptor-coupled guanylate cyclase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;157(2):755–761. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak LS, Tiberi M, Freedman NJ, Kwatra MM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. A highly conserved tyrosine residue in G protein-coupled receptors is required for agonist-mediated beta 2-adrenergic receptor sequestration. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(4):2790–2795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi C, Gutkowska J, Thibault G, Garcia R, Genest J, Cantin M. Distinct localization of atrial natriuretic factor and angiotensin II binding sites in the glomerulus. Am J Physiol. 1986;251(4 Pt 2):F594–F602. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.251.4.F594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottari SP, King IN, Reichlin S, Dahlstroem I, Lydon N, de Gasparo M. The angiotensin AT2 receptor stimulates protein tyrosine phosphatase activity and mediates inhibition of particulate guanylate cyclase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;183(1):206–211. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackmann M, Schuchmann S, Anand R, Braunewell KH. Neuronal Ca2+ sensor protein VILIP-1 affects cGMP signalling of guanylyl cyclase B by regulating clathrin-dependent receptor recycling in hippocampal neurons. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 11):2495–2505. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner BM, Ballermann BJ, Gunning ME, Zeidel ML. Diverse biological actions of atrial natriuretic peptide. Physiol Rev. 1990;70(3):665–699. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burczynska B, Duda T, Sharma RK. ATP signaling site in the ARM domain of atrial natriuretic factor receptor guanylate cyclase. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;301(1–2):93–107. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett JC, Jr, Granger JP, Opgenorth TJ. Effects of synthetic atrial natriuretic factor on renal function and renin release. Am J Physiol. 1984;247(5 Pt 2):F863–F866. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1984.247.5.F863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Wu J, Gardner DG. Atrial natriuretic peptide suppresses the transcription of its guanylyl cyclase-linked receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(42):24891–24897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak R, Kleta R, Forssmann WG, Schlatter E. Natriuretic peptides increase a K+ conductance in rat mesangial cells. Pflugers Arch. 1996;431(4):571–577. doi: 10.1007/BF02191905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MS, Lowe DG, Lewis M, Hellmiss R, Chen E, Goeddel DV. Differential activation by atrial and brain natriuretic peptides of two different receptor guanylate cyclases. Nature. 1989;341(6237):68–72. doi: 10.1038/341068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles CJ, Espiner EA, Richards AM, Nicholls MG, Yandle TG. Biological actions and pharmacokinetics of C-type natriuretic peptide in conscious sheep. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(1 Pt 2):R201–R207. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.1.R201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Burnett JC., Jr The natriuretic peptides in heart failure: diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111(5):406–416. doi: 10.1111/paa.1999.111.5.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkers M, Garbers DL. The protein kinase domain of the ANP receptor is required for signaling. Science. 1989;245(4924):1392–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.2571188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkers M, Garbers DL, Chang MS, Lowe DG, Chin HM, Goeddel DV, et al. A membrane form of guanylate cyclase is an atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Nature. 1989;338(6210):78–83. doi: 10.1038/338078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisman TD, Garbers DL. Reciprocal antagonism coordinates C-type natriuretic peptide and mitogen-signaling pathways in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(7):4293–4299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogan MG, Huang CL, Liu FY, Madden D, Wong KR. Effect of atrial natriuretic factor on acid-base homeostasis. J Hypertens Suppl. 1986;4(2):S31–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Au E, Krazit ST, Pandey KN. Targeted disruption of guanylyl cyclase-A/natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene provokes renal fibrosis and remodeling in null mutant mice: role of proinflammatory cytokines. Endocrinology. 2010;151(12):5841–5850. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bold AJ. Atrial natriuretic factor: a hormone produced by the heart. Science. 1985;230(4727):767–770. doi: 10.1126/science.2932797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bold AJ, Borenstein HB, Veress AT, Sonnenberg H. A rapid and potent natriuretic response to intravenous injection of atrial myocardial extract in rats. Life Sci. 1981;28(1):89–94. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lean A, McNicoll N, Labrecque J. Natriuretic peptide receptor A activation stabilizes a membrane-distal dimer interface. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(13):11159–11166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschepper CF, Masciotra S, Zahabi A, Boutin-Ganache I, Picard S, Reudelhuber TL. Function alterations of the Nppa promoter are linked to cardiac ventricular hypertrophy in WKY/WKHA rat crosses. Circ. Res. 2001;88:223–228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doust JA, Pietrzak E, Dobson A, Glasziou P. How well does B-type natriuretic peptide predict death and cardiac events in patients with heart failure: systematic review. BWJ. 2005:330–625. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7492.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewett JG, Garbers DL. The family of guanylyl cyclase receptors and their ligands. Endocr Rev. 1994;15(2):135–162. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-2-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda T, Goraczniak RM, Sharma RK. Core sequence of ATP regulatory module in receptor guanylate cyclases. FEBS Lett. 1993;315(2):143–148. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81151-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda T, Sharma RK. Regulation of guanylate cyclase activity by atrial natriuretic factor and protein kinase C. Mol Cell Biochem. 1990;93(2):179–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00226190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellmers LJ, Knowles JW, Kim HS, Smithies O, Maeda N, Cameron VA. Ventricular expression of natriuretic peptides in Npr1(−/−) mice with cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283(2):H707–H714. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00677.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellmers LJ, Scott NJ, Piuhola J, Maeda N, Smithies O, Frampton CM, et al. Npr1-regulated gene pathways contributing to cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;38(1–2):245–257. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felker GM, Petersen JW, Mark DB. Natriuretic peptides in the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Cmaj. 2006;175(6):611–617. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller SM, Mägert HJ, Schulz-Knappe P, Forssmann WG. Urodilatin (hANF 95–126) -Characteristics of a new atrial natriuretic factor peptide. In: Struthers AD, editor. Atrial Natriuretic Factor. Oxford: UK Blackwell; 1990. pp. 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fenrick R, Bouchard N, McNicoll N, De Lean A. Glycosylation of asparagine 24 of the natriuretic peptide receptor-B is crucial for the formation of a competent ligand binding domain. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;173(1–2):25–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1006855522272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenrick R, McNicoll N, De Lean A. Glycosylation is critical for natriuretic peptide receptor-B function. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;165(2):103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00229471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn TG, de Bold ML, de Bold AJ. The amino acid sequence of an atrial peptide with potent diuretic and natriuretic properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;117(3):859–865. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DC, Garbers DL. Dual role for adenine nucleotides in the regulation of the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor, guanylyl cyclase-A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(26):16311–16318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried TA, McCoy RN, Osgood RW, Stein JH. Effect of atriopeptin II on determinants of glomerular filtration rate in the in vitro perfused dog glomerulus. Am J Physiol. 1986;250(6 Pt 2):F1119–F1122. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.250.6.F1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujio N, Gossard F, Bayard F, Tremblay J. Regulation of natriuretic peptide receptor A and B expression by transforming growth factor-beta 1 in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 1994;23(6 Pt 2):908–913. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller F, Porter JG, Arfsten AE, Miller J, Schilling JW, Scarborough RM, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide clearance receptor. Complete sequence and functional expression of cDNA clones. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(19):9395–9401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbers DL. Guanylyl cyclase receptors and their endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine ligands. Cell. 1992;71(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90258-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbers DL, Chrisman TD, Wiegn P, Katafuchi T, Albanesi JP, Bielinski V, et al. Membrane guanylyl cyclase receptors: an update. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17(6):251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbers DL, Lowe DG. Guanylyl cyclase receptors. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(49):30741–30744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DG. Natriuretic peptides: markers or modulators of cardiac hypertrophy? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14(9):411–416. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R, Pandey KN. Angiotensin II-mediated negative regulation of Npr1 promoter activity and gene transcription. Hypertension. 2003;41(3 Pt 2):730–736. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000051890.68573.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutkowska J, Jankowski M, Sairam MR, Fujio N, Reis AM, Mukaddam-Daher S, et al. Hormonal regulation of natriuretic peptide system during induced ovarian follicular development in the rat. Biol Reprod. 1999;61(1):162–170. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haneda M, Kikkawa R, Maeda S, Togawa M, Koya D, Horide N, et al. Dual mechanism of angiotensin II inhibits ANP-induced mesangial cGMP accumulation. Kidney Int. 1991;40(2):188–194. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim JM, Singh S, Gerzer R. Effect of glycosylation on cloned ANF-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Life Sci. 1996;59(4):PL61–PL68. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SJ, Espiner EA, Richards AM, Yandle TG, Frampton C. Renal, endocrine, and hemodynamic effects of human brain natriuretic peptide in normal man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76(1):91–96. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.1.8380606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtwick R, van Eickels M, Skryabin BV, Baba HA, Bubikat A, Begrow F, et al. Pressure-independent cardiac hypertrophy in mice with cardiomyocyte-restricted inactivation of the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor guanylyl cyclase-A. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(9):1399–1407. doi: 10.1172/JCI17061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huganir RL, Greengard P. Regulation of neurotransmitter receptor desensitization by protein phosphorylation. Neuron. 1990;5(5):555–567. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90211-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PJ, Richards AM, Espiner EA, Nicholls MG, Yandle TG. Bioactivity and metabolism of C-type natriuretic peptide in normal man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78(6):1428–1435. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.6.8200946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80(2):225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson HG, Trindade PT, Cunanan DB, Wu CF, Pratt RE. Mechanisms of natriuretic-peptide-induced growth inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35(1):158–167. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AS, Babuin L, Apple FS. Biomarkers in acute cardiac disease: the present and the future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W, Foo JN, O'Roak BJ, Zhao H, Larson MG, Simon DB, et al. Rare independent mutations in renal salt handling genes contribute to blood pressure variation. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):592–599. doi: 10.1038/ng.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John SW, Krege JH, Oliver PM, Hagaman JR, Hodgin JB, Pang SC, et al. Genetic decreases in atrial natriuretic peptide and salt-sensitive hypertension. Science. 1995;267(5198):679–681. doi: 10.1126/science.7839143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(3):769–824. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan IA, Fink J, Nass C, Chen H, Christenson R, deFilippi CR. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and B-type natriuretic peptide for identifying coronary artery disease and left ventricular hypertrophy in ambulatory chronic kidney disease patients. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1530–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana ML, Pandey KN. Receptor-mediated stimulatory effect of atrial natriuretic factor, brain natriuretic peptide, and C-type natriuretic peptide on testosterone production in purified mouse Leydig cells: activation of cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme. Endocrinology. 1993;133(5):2141–2149. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8404664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana ML, Pandey KN. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits the phosphoinositide hydrolysis in murine Leydig tumor cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;158(2):97–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00225834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic A, Bubikat A, Gassner B, Baba HA, Kuhn M. Local actions of atrial natriuretic peptide counteract angiotensin II stimulated cardiac remodeling. Endocrinology. 2007;148(9):4162–4169. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto I, Rossi K, Garbers DL. A genetic model provides evidence that the receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide (guanylyl cyclase-A) inhibits cardiac ventricular myocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(5):2703–2706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051625598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles JW, Erickson LM, Guy VK, Sigel CS, Wilder JC, Maeda N. Common variations in noncoding regions of the human natriuretic peptide receptor A gene have quantitative effects. Hum Genet. 2003;112(1):62–70. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0834-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles JW, Esposito G, Mao L, Hagaman JR, Fox JE, Smithies O, et al. Pressure-independent enhancement of cardiac hypertrophy in natriuretic peptide receptor A-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(8):975–984. doi: 10.1172/JCI11273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller KJ, de Sauvage FJ, Lowe DG, Goeddel DV. Conservation of the kinaselike regulatory domain is essential for activation of the natriuretic peptide receptor guanylyl cyclases. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(6):2581–2590. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller KJ, Goddel DV. Molecular biology of the natriuretic peptides and their receptors. Circulation. 1992;86:1081–1088. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller KJ, Lipari MT, Goeddel DV. Proper glycosylation and phosphorylation of the type A natriuretic peptide receptor are required for hormone-stimulated guanylyl cyclase activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(8):5997–6003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller KJ, Lowe DG, Bennett GL, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, et al. Selective activation of the B natriuretic peptide receptor by C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) Science. 1991;252(5002):120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1672777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M. Cardiac and intestinal natriuretic peptides: insights from genetically modified mice. Peptides. 2005;26:1078–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M, Volker K, Schwarz K, Carbajo-Lozoya J, Flogel U, Jacoby C, et al. The natriuretic peptide/guanylyl cyclase--a system functions as a stress-responsive regulator of angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(7):2019–2030. doi: 10.1172/JCI37430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Bolden G, Arise KK, Krazit ST, Pandey KN. Regulation of natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene expression and stimulation of its guanylate cyclase activity by transcription factor Ets-1. Biosci Rep. 2009;29(1):57–70. doi: 10.1042/BSR20080094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Garg R, Bolden G, Pandey KN. Interactive roles of Ets-1, Sp1, and acetylated histones in the retinoic acid-dependent activation of guanylyl cyclase/atrial natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(48):37521–37530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.132795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Pandey KN. Cooperative activation of Npr1 gene transcription and expression by interaction of Ets-1 and p300. Hypertension. 2009;54(1):172–178. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.133033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Cartledge WA, Lincoln TM, Pandey KN. Expression of guanylyl cyclase-A/atrial natriuretic peptide receptor blocks the activation of protein kinase C in vascular smooth muscle cells. Role of cGMP and cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Hypertension. 1997;29(1 Pt 2):414–421. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.1.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurose H, Inagami T, Ui M. Participation of adenosine 5'-triphosphate in the activation of membrane-bound guanylate cyclase by the atrial natriuretic factor. FEBS Lett. 1987;219(2):375–379. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurose H, Lefkowitz RJ. Differential desensitization and phosphorylation of three cloned and transfected alpha 2-adrenergic receptor subtypes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(13):10093–10099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz A, Della Bruna R, Pfeilschifter J, Taugner R, Bauer C. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits renin release from juxtaglomerular cells by a cGMP-mediated process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(13):4769–4773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlet C, Langer I, Vertongen P, Gaspard N, Vanderwinden JM, Robberecht P. Contribution of the carboxyl terminus of the VPAC1 receptor to agonist-induced receptor phosphorylation, internalization, and recycling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(30):28034–28043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPointe MC. Molecular regulation of the brain natriuretic peptide gene. Peptides. 2005;26:944–956. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larose L, Rondeau JJ, Ong H, De Lean A. Phosphorylation of atrial natriuretic factor R1 receptor by serine/threonine protein kinases: evidences for receptor regulation. Mol Cell Biochem. 1992;115(2):203–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00230332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Lieu H, Burnett JC., Jr Designer natriuretic peptides. J Investig Med. 2009;57(1):18–21. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e3181946fb2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER, Frank HJ. Natriuretic peptides inhibit rat astroglial proliferation: mediation by C receptor. Am J Physiol. 1991;261(2 Pt 2):R453–R457. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.2.R453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. Natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):321–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, DeStefano AL, Larson MG, O'Donnell CJ, Lifton RP, Gavras H, et al. Evidence for a gene influencing blood pressure on chromosome 17. Genome scan linkage results for longitudinal blood pressure phenotypes in subjects from the framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2000;36(4):477–483. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kishimoto I, Saito Y, Harada M, Kuwahara K, Izumi T, et al. Guanylyl cyclase-A inhibits angiotensin II type 1A receptor-mediated cardiac remodeling, an endogenous protective mechanism in the heart. Circulation. 2002;106(13):1722–1728. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029923.57048.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F, Schaufele F, Gardner DG. Functional interaction of NF-Y and Sp1 is required for type a natriuretic peptide receptor gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(2):1516–1522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell. 2001;104(4):545–556. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light DB, Schwiebert EM, Karlson KH, Stanton BA. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits a cation channel in renal inner medullary collecting duct cells. Science. 1989;243(4889):383–385. doi: 10.1126/science.2463673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KF, Chao J, Chao L. Human atrial natriuretic peptide gene delivery reduces blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1995;26(6 Pt 1):847–853. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.6.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln TM, Dey N, Sellak H. Invited review: cGMP-dependent protein kinase signaling mechanisms in smooth muscle: from the regulation of tone to gene expression. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(3):1421–1430. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisy O, Huntley BK, McCormick DJ, Kurlansky PA, Burnett JC., Jr Design, synthesis, and actions of a novel chimeric natriuretic peptide: CD-NP. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ruoho AE, Rao VD, Hurley JH. Catalytic mechanism of the adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases: modeling and mutational analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(25):13414–13419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MJ, Wong SK, Kishimoto I, Dubois S, Mach V, Friesen J, et al. Salt-resistant hypertension in mice lacking the guanylyl cyclase-A receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide. Nature. 1995;378(6552):65–68. doi: 10.1038/378065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe DG, Fendly BM. Human natriuretic peptide receptor-A guanylyl cyclase. Hormone cross-linking and antibody reactivity distinguish receptor glycoforms. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(30):21691–21697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]