Background: The essential protein Swd2 is in both H3K4 methyltransferase complex Set1C/COMPASS and transcription termination factor APT.

Results: Set1 deletion increases promoter cross-linking of the TFIIE large subunit and phosphorylated CTD, decreases COMPASS and Swd2, and suppresses lethality of Swd2 depletion.

Conclusion: Set1-COMPASS affects early transcription and creates a requirement for Swd2 in APT recruitment.

Significance: Swd2 may coordinate H3K4 methylation and early transcription termination.

Keywords: Histone Methylation, RNA Polymerase II, RNA Processing, Transcription Initiation Factors, Transcription Termination, APT, COMPASS, RNA Polymerase II CTD, TFIIE, snoRNA Termination

Abstract

The Set1 complex (also known as complex associated with Set1 or COMPASS) methylates histone H3 on lysine 4, with different levels of methylation affecting transcription by recruiting various factors to distinct regions of active genes. Neither Set1 nor its associated proteins are essential for viability with the notable exception of Swd2, a WD repeat protein that is also a subunit of the essential transcription termination factor APT (associated with Pta1). Cells lacking Set1 lose COMPASS recruitment but show increased promoter cross-linking of TFIIE large subunit and the serine 5 phosphorylated form of the Rpb1 C-terminal domain. Although Swd2 is normally required for bringing APT to genes, deletion of SET1 restores both viability and APT recruitment to a strain lacking Swd2. We propose a model in which Swd2 is required for APT to overcome antagonism by COMPASS.

Introduction

Eukaryotic genomic DNA is wrapped around histone proteins to form nucleosomes. The covalent modification of histones is important for establishment of static or dynamic chromatin domains, thereby providing an important step for regulation of gene expression. Most of these covalent modifications, which include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, have been mapped to the histone tails that extend outside of the core nucleosome structure. Particular modifications are preferentially localized in specific regions of the genome and confer the functional characteristics of different chromatin domains.

Methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4) was first correlated with active chromatin in Tetrahymena (1) but also later shown to be required for rDNA and telomeric silencing in yeast (2–4). The protein responsible for all H3K4 methylation in S. cerevisiae is Set1 (2), which associates with seven other proteins (Bre2/Cps60, Sdc1/Cps25, Shg1/Cps15, Spp1/Cps40, Swd1/Cps50, Swd2/Cps35, and Swd3/Cps30) to form a complex known as COMPASS or SET1C (5, 6). Although histone methylation activity resides in the SET domain of Set1, the other subunits of the complex influence the stability and activity of this methyltransferase (7–9). In addition to the role of H3K4 methylation in transcription, SET1 deletion causes pleiotropic defects in telomere length, DNA repair, chromosome segregation, and meiotic differentiation (8). The presence of two predicted RNA recognition motifs in Set1, one of which has been shown to bind RNA in vitro, also raises the possibility of COMPASS interacting with RNA (10, 11).

Genome-wide analyses show some H3K4 methylation at silenced loci but mostly reveal a strong correlation with active genes (12). Lysines can accept up to three methyl groups. Detailed analysis of H3K4 methylation along transcribing genes show that H3K4me3 is particularly enriched near promoters (13, 14), followed by a peak of H3K4me2 within the 5′ to middle region of genes, and highest levels of H3K4me1 are toward the 3′ region of longer genes (15–17). The recruitment of COMPASS to transcribing genes is dependent upon the PAF complex, ubiquitylation of histone H2B, and phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain (CTD)3 of the RNA polymerase II (RNApII) largest subunit by TFIIH (reviewed in Ref. 18).

H3K4 methylation is thought to affect gene expression by recruiting other factors, including several chromatin remodeling and modifying complexes. Many of these complexes recognize H3K4 methylation through one or more methyl-lysine-binding domains, such as the chromodomain and plant homeodomain finger (19). For example, the yeast Set3C histone deacetylase complex binds H3K4me2 (20), and in higher eukaryotes the Chd1 (21) and Taf3 (22) proteins interact with H3K4me3. The ING/Yng family contains plant homeodomain finger proteins that also recognize methylated H3K4 (23). The yeast NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex contains the plant homeodomain finger protein Yng1, which is thought to recognize H3K4me3, as well as the Eaf3 chromodomain protein, which binds methylated H3K36 (24, 25).

Of all the COMPASS subunits, Swd2 is the only one that is essential for viability. This WD repeat protein is also a component of the RNA 3′ end processing and termination complex called APT, for associated with Pta1 (26–29). Although APT purifies as a subcomplex of the mRNA cleavage and polyadenylation factor, mutations in APT subunits lead to termination defects at nonpolyadenylated yeast snoRNAs (28–30). Only some of the APT subunits are essential for viability; in addition to Swd2, they include Pti1 and the phosphatases Glc7 and Ssu72. We show here that Swd2 is normally required to bring APT to snoRNA genes. This recruiting function likely contributes to the requirement for Swd2 because swd2Δ lethality can be suppressed by overexpression of the APT subunit Ref2 (26). Termination at snoRNAs and other cryptic, noncoding transcripts is primarily mediated by the Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 complex (31, 32), which is recruited co-transcriptionally to the 5′ end of genes by interactions with serine 5 phosphorylated CTD of RNApII (33), as well as through recognition of specific RNA sequences. Termination is presumed to be mediated by the helicase activity of Sen1. Interestingly, swd2Δ lethality is also suppressed by expression of a Sen1 fragment that lacks Sen1 helicase activity (30), perhaps because of titration of an inhibitor. The relationship between APT and the Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 complex remains unclear.

Here we probe the role of COMPASS and Swd2 in modulating early events during transcription that affect the APT complex and usage of the early snoRNA termination pathway. Although deletion of SET1 does not cause major changes in recruitment of the RNApII initiation complex, chromatin immunoprecipitation shows higher cross-linking levels of CTD serine 5 phosphorylation and the large subunit of TFIIE. Cells lacking SET1 are also defective in recruitment of COMPASS, including the Swd2 component. Despite the reduction of Swd2 levels, other components of the APT and Nrd1 complexes are recruited normally. Surprisingly, the Swd2 protein is no longer required for viability or for recruitment of the APT complex in the absence of Set1. We propose a model in which COMPASS and the APT complex, both aided by Swd2, may sequentially occupy overlapping space.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

This study used anti-H3 (Abcam Ab1791), anti-H3K4me2 (Upstate 06-030), anti-H3K4me3 (Upstate 07-473), and anti-Rpb3 from Neoclone; anti-TFA1 and anti-TFA2 (34), anti-Sua7, anti-TBP, anti-Kin28, anti-Tfb1, anti-HA (12CA5), anti-Myc (9E10), and anti-NAB3 from Jeff Corden; anti-RPB1 CTD Ser5P (3E8) and Ser7P (4E12) from Dirk Eick (35); and anti-RPB1 CTD Ser2P (H5) from Warren et al. (36).

Yeast Strains and Plasmids

Yeast culture was performed using standard methods. Growth was in YPD or the indicated minimal media. Yeast strains used are listed in supplemental Table S1. Spotting analyses for sensitivity to 6-azauracil (6AU; 20 μg/ml) were performed as previously described (20). Swd2 degron strains were constructed as described (26).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitations

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were done as previously described (20). 0.5 μl of anti-H3, anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K4me2, or 5 μl of the other antibodies were used to precipitate 1 mg of chromatin with 10 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads. FLAG immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-FLAG-agarose beads, and TAP tag precipitation was performed using IgG-Sepharose beads. Binding was done overnight at 4 °C in FA lysis buffer containing 275 mm NaCl. Precipitates were washed with the same buffer, once with FA lysis buffer containing 500 mm NaCl, once with wash buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.25 m LiCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate), and once with TE (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mm EDTA). Precipitated DNA was analyzed for specific gene sequences by PCR. PCR conditions were 60 s at 94 °C, followed by 25 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C, followed by 2 min at 72 °C. The sequences of oligonucleotides used are listed in supplemental Table S2. Signals for histone modifications were normalized to total H3, and COMPASS complex component signals were normalized to untagged strains. In all other cases, signals were normalized to input samples and a nontranscribed control region. Where indicated, signals were expressed relative to Rpb3 ChIP levels.

RNA Analysis

RNA was extracted from cells with hot water-equilibrated phenol. First strand cDNA was prepared using 1 μg of total RNA treated with DNase I, Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and gene-specific primers (supplemental Table S3). One-quarter of the cDNA was used for quantitative PCR using a Roche Lightcycler 480 amplification or for standard PCR and analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Immunoblotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared from 50 ml of exponentially growing cultures. The cell pellets were resuspended in breaking buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 300 mm sorbitol, 600 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm EDTA) with the addition of protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin A, anti-pain, 1 mm PMSF). The cells were disrupted by vortexing with acid-washed glass beads for five 30-s pulses. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant (whole cell extract) was used for protein analysis. 20 μg of whole cell extract were resolved by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed for TAP tag or TBP as a loading control.

RESULTS

Recruitment of COMPASS

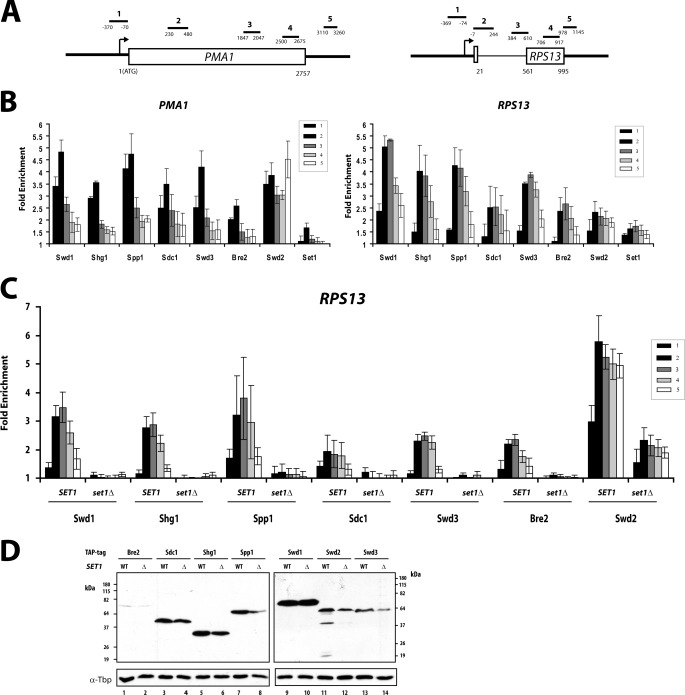

Chromatin immunoprecipitation of epitope-tagged COMPASS subunits was performed on the model genes PMA1 and RPS13 (Fig. 1A). As expected, all components of the COMPASS complex show a peak at the 5′ region of the gene (Fig. 1B). Consistent with H3 K4 methylation throughout the entire gene, ChIP signals above background for all components were seen with all PCR primers (Fig. 1B). However, the higher levels of H3K4 methylation (H3K4me3 and H3K4me2) correlated with the strongest cross-linking of COMPASS. It has been proposed that the peak of H3K4me3 at active promoters (supplemental Fig. S1A) is due to interaction of COMPASS with the CTD of the RNApII subunit Rpb1. More specifically, the basal transcription factor TFIIH phosphorylates the CTD at serine 5 of the YSPTSPS repeat at the promoter, and the TFIIH kinase is necessary for efficient COMPASS recruitment (13). Swd2, the COMPASS subunit that is also a component of the APT termination complex, continues to cross-link strongly downstream and has a second peak at the 3′ end (Fig. 1B and Ref. 28).

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment of COMPASS subunits is dependent upon Set1. A, schematic representation of primer pairs used throughout this paper for ChIP analysis of PMA1 and RPS13 genes. B, ChIP of COMPASS subunits to PMA1 and RPS13 genes. TAP-tagged versions of Swd1, Shg1, Spp1, Sdc1, Swd3, Bre2, and Swd2 or FLAG-tagged Set1 were analyzed by ChIP. The bars represent primer pairs as depicted in A, and fold enrichment was calculated after normalization against values for untagged strains. The error bars represent standard errors from biological triplicates. C, recruitment of TAP-tagged versions of COMPASS components to the RPS13 gene was analyzed in SET1 and set1Δ strains by ChIP as in B. D, protein levels of COMPASS components in SET1 and set1Δ backgrounds. 50 μg of whole cell extracts from exponentially growing cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot against TAP tag or TBP (used as a protein loading control).

The large Set1 protein has been proposed to be the platform upon which the other COMPASS components assemble. Consistent with this idea, deletion of Set1 eliminates the ChIP signal of all COMPASS components except for Swd2 (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S1B). This loss of cross-linking was not due to degradation of the proteins, because the levels of all the components were similar in SET1 and set1Δ cells (Fig. 1D). Although the levels of Spp1, Swd3, and some others do show a slight decrease in the set1Δ background, this was insufficient to explain their complete absence at transcribing genes. Therefore, Set1 is required both to methylate H3K4 and to recruit the other COMPASS subunits.

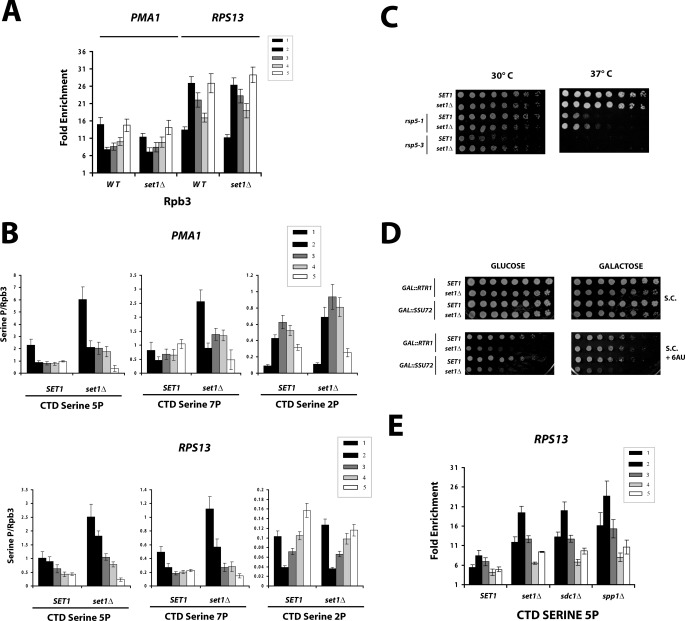

SET1 Deletion Causes Increased CTD Serine 5 Phosphorylation

Although cells lacking SET1 exhibit changes in the transcription levels of some genes (12, 37), they often show alterations in the induction or repression kinetics of regulated genes (13, 38, 39). Deletion of SET1 also confers sensitivity to the drug 6AU (20), which slows transcription elongation by depleting NTP pools. Therefore, we speculated that H3K4 methylation might be important for the correct kinetics of early transcription. To explore this possibility, ChIP against the Rpb3 subunit of RNApII was carried out. Overall levels of polymerase cross-linking were not strongly affected by set1Δ at the genes tested (Fig. 2A), showing only a modest reduction in the promoter signal in the PMA1 gene. In contrast, a significant increase in the ChIP levels of CTD phosphorylation was observed in set1Δ cells, particularly for serines 5 and 7 (Fig. 2B). These two modifications are strongest near the 5′ end of genes and are both deposited by the TFIIH-associated kinase Kin28 (40–42).

FIGURE 2.

Cells lacking Set1 have increased CTD phosphorylation. A, ChIP of RNApII subunit Rpb3 in SET1 and set1Δ cells. B, ChIPs of Rpb1 CTD phospho-epitopes using antibodies 3E8 (serine 5P), 4E10 (serine 7P), (35), or H5 (serine 2P) (36) were performed in SET1 and set1Δ strains. The values were normalized to Rpb3 ChIP values to control for total RNApII levels. C, suppression of rsp5 mutant phenotypes by set1Δ. Three-fold serial dilutions of indicated strains were spotted on synthetic media with required supplements at the indicated temperature. D, suppression of set1Δ 6AU sensitivity by overexpression of Rtr1 CTD phosphatase. The indicated cells were spotted on media containing glucose (repressing) or galactose (inducing overexpression of Rtr1 or Ssu72), with or without 20 μg/ml of 6AU. E, ChIP of serine 5 phosphorylated Rpb1 CTD (3E8 antibody) in SET1, set1Δ, sdc1Δ, or spp1Δ chromatin was carried out the RSP13 gene.

To test for biological relevance of the increased CTD serine 5 phosphorylation, several experiments were performed. Temperature-sensitive phenotypes caused by mutations in the ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 are suppressed by the overexpression of Kin28 (43). Rsp5 has been shown to mediate degradation of stalled RNApII dependent upon interactions with the CTD (44). Consistent with a model in which increased CTD phosphorylation compensates for insufficient Rsp5 activity, the absence of Set1 partially suppresses the slow growth of two RSP5 alleles (Fig. 2C): rsp5-1 and rsp5-3 (45, 46).

To test whether the 6AU sensitivity of set1Δ strains could be related to excessive CTD phosphorylation, the two known CTD serine 5 phosphatases Rtr1 (47) and Ssu72 (48, 49) were overexpressed from galactose-inducible promoters. Overexpression of Rtr1, but not Ssu72, was able to reverse the 6AU sensitivity of set1Δ (Fig. 2D). These results are consistent with the observation that RTR1 deletion increases CTD serine 5 phosphorylation throughout the gene (47), whereas SSU72 appears to act during termination (28).

To establish which level of H3K4 methylation is necessary for lower CTD serine 5 phosphorylation, strains lacking two other COMPASS subunits were tested. Deletion of SDC1, although not affecting the stability of Set1, abolishes H3K4me3 specifically (30). Deletion of SPP1 decreases the levels of the methylase, causing a partial decrease in the levels of H3K4me3 (7, 30). ChIP in these strains reveals an increase in CTD serine 5 phosphorylation similar to that observed in set1Δ cells (Fig. 2E).

SET1 Deletion Affects Interaction of TFIIE with Promoter

To investigate the mechanism connecting histone methylation and CTD phosphorylation, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation of several basal transcription initiation factors that could affect this process (Fig. 3). As expected, initiation factors cross-linked to the PMA1 and RPS13 promoters and were absent from coding regions. No significant differences were seen for TFIIB, TBP, or TFIIF in the SET1 deletion background. Furthermore, the recruitment of TFIIH components Rad3 and Kin28, the factor directly responsible for CTD phosphorylation, is unaffected in the deletion strain. Therefore, the increase in CTD phosphorylation in set1Δ is not due to increased recruitment of the CTD serine 5 kinase.

FIGURE 3.

Loss of Set1 does not affect recruitment of most transcription initiation factors. ChIP of transcription initiation factors in SET1 and set1Δ backgrounds. Sua7 (TFIIB), Tbp (TFIID), Tfg2 (TFIIF), Kin28 (TFIIK), and HA-tagged Rad3 (TFIIH) were analyzed on the PMA1 and RPS13 genes.

Several other factors known to associate with RNApII during elongation were also analyzed. These included the cap-binding complex (Sto1), the PAF complex (Paf1), Spt5, Bur1 kinase, and capping enzyme (supplemental Fig. S2 and data not shown). Again, there was no significant change in cross-linking levels in the absence of Set1. This lack of effect suggests that the 6AU sensitivity of set1Δ cells is not related to major disruption of elongation.

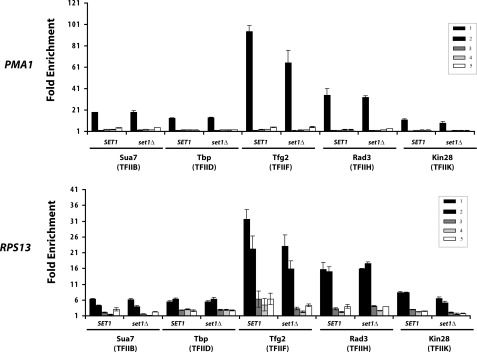

The basal initiation factor TFIIE is necessary for maximal activity of TFIIH in phosphorylating CTD serine 5 (50, 51). Yeast TFIIE is an essential initiation factor composed of two subunits: Tfa1 and Tfa2. Tfa2 can bind single-stranded DNA (34), and Tfa1 interacts with TFIIH to stimulate Kin28 activity (52). As expected for an initiation factor, TFIIE cross-links almost exclusively to the promoter region of genes (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, whereas the recruitment of Tfa2 is similar in a set1Δ background, a significant increase in Tfa1 cross-linking to promoters is observed. The same result was obtained whether we used an anti-Tfa1 polyclonal antibody (Fig. 4A) or a C-terminal epitope tag (data not shown). Given the recent finding that TFIIE occupies a similar location as the elongation factor Spt4/5 (53), we wondered whether the loss of Set1 could inhibit the exchange of Spt4/5 for TFIIE. However, no change in Spt5 cross-linking was seen in set1Δ cells (supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of SET1 deletion on TFIIE and CTD phosphorylation. A, ChIP of TFIIE subunits Tfa1 and Tfa2 were performed in SET1 and set1Δ cells on the PMA1 and RPS13 genes. B, SET1 interacts genetically with TFA1. Three-fold serial dilutions of strains with SET1 (WT) or set1Δ combined with temperature-sensitive (upper panels) or cold-sensitive alleles (lower panels) of TFA1 were spotted on synthetic media and grown for 3 days at the indicated temperatures. C, ChIP of Rpb3 in TFA1, tfa1(C152Y), or tfa1(C152Y) plus set1Δ cells was performed using cells grown at the permissive temperature of 30 °C. D, ChIP of Tfa1 and CTD serine 5 phosphorylation (3E8) were performed in TFA1, tfa1(C152Y), or tfa1(C152Y) plus set1Δ cells. The values were normalized relative to RNApII recruitment from C.

We noted that Tfa2 displays additional enrichment at the transcription termination region (Fig. 4A), a pattern resembling that of factors proposed to be involved in gene-looping (54, 55). However, TFIIE exists as a stable heterodimer of Tfa1 and Tfa2. Therefore, increased cross-linking of Tfa1 at the promoter suggests either binding of Tfa1 free of Tfa2 or, more likely, that some change upon SET1 deletion alters the ability of Tfa1 to cross-link or immunoprecipitate the associated DNA. Given the role of Set1 in histone modification, it seems possible that increased chromatin accessibility in set1Δ cells might cause differential interactions or cross-linking of Tfa1 with promoter DNA. We previously showed that set1Δ strains have increased histone acetylation and lower nucleosome density at promoters and 5′ regions of genes (20), which could increase DNA accessibility or perhaps affect DNA topology and promoter melting. If altered DNA accessibility in SET1 mutant strains is the cause of increased Tfa1 cross-linking, it must be specific for this protein because a similar effect was not seen for Tfa2 or other basal factors.

To further investigate the connection between Set1 and Tfa1, we combined a series of previously characterized Tfa1 mutants (34) with set1Δ (Fig. 4B). One class of cold-sensitive tfa1 alleles consists of truncations that remove an acidic C-terminal region that in mammals interacts with TFIIH (50). The growth rates of these strains were not affected by deletion of SET1 (Fig. 4B, lower panels). In contrast, point mutants in the Tfa1 zinc ribbon, which cause sensitivity to high temperatures, show synthetic lethality at 37 °C in combination with set1Δ (Fig. 4B, upper panels). tfa1(C152Y) has a synthetic slow growth phenotype with set1Δ even at the permissive temperature. These results indicate that, of the two genetically distinct functional domains in the large subunit of TFIIE, one may function together with Set1, and the other may function in a Set1-independent manner.

To explore the molecular basis for the genetic interaction between TFA1 and SET1, we performed ChIP of both Tfa1 and CTD serine 5 phosphorylation using the temperature-sensitive tfa1(C152Y) allele. This Tfa1 mutant shows markedly decreased cross-linking to the promoter region (Fig. 4D and supplemental Fig. S3) and a comparable decrease in the levels of CTD serine 5 phosphorylation. Although RNApII cross-linking is also decreased in the tfa1(C152Y) mutant (Fig. 4C), this does not account for the decrease observed for TFIIE and CTD phosphorylation because the effect is seen even after normalization for total polymerase levels (Fig. 4D and supplemental Fig. S3). When tfa1(C152Y) is combined with SET1 deletion, the previously observed increase (Fig. 2B) in Tfa1 and CTD Ser5P cross-linking is lost. Taken together, the data suggest that Set1 and H3K4 methylation can affect the interaction of Tfa1 with the promoter, which may in turn modulate CTD phosphorylation by TFIIH.

SET1 Deletion Bypasses Requirement for Swd2

The Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 complex functions together with APT in termination at yeast snoRNAs and other short nonpolyadenylated transcripts, targeted in part by CTD serine 5 phosphorylation (33, 56). COMPASS has also been genetically connected to this early termination pathway (57). The essential protein Swd2 is a subunit of both COMPASS and the APT termination complex, and SWD2 mutants cause defective snoRNA termination (26–29). How Swd2 contributes to snoRNA termination as a member of one or both complexes remains unclear.

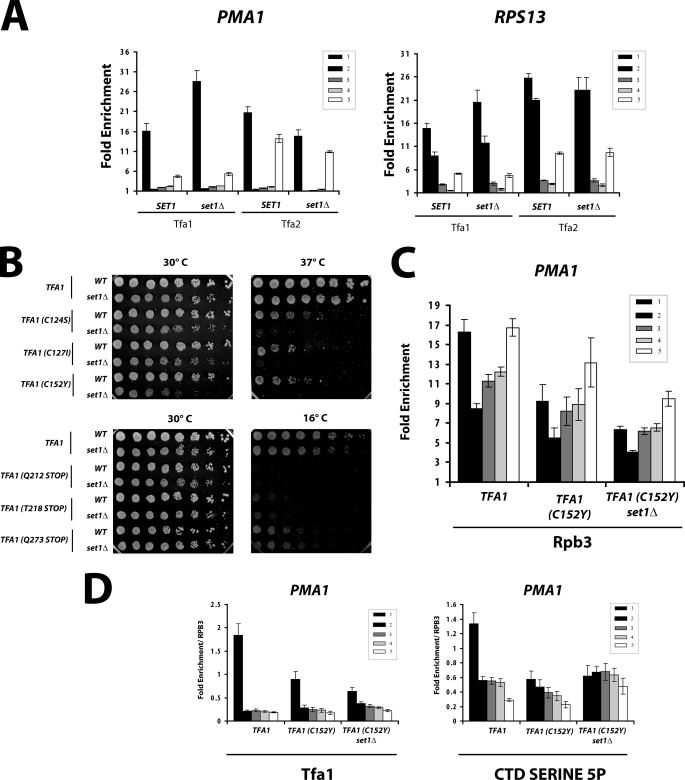

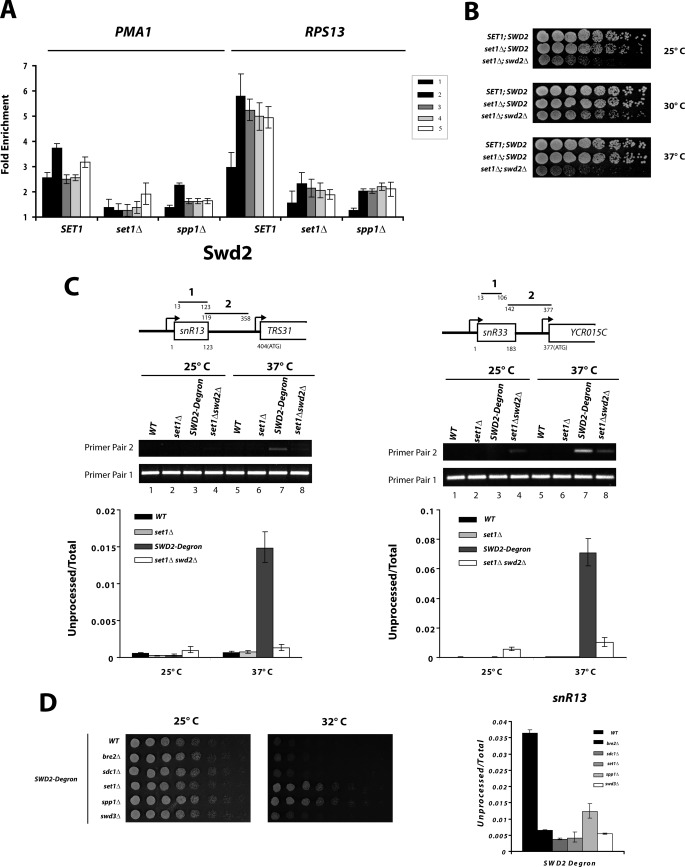

Like other COMPASS subunits, the recruitment of Swd2 is severely compromised when SET1 or SPP1 is deleted (Fig. 5A). However, low levels of Swd2 persist in transcribed and downstream regions of mRNAs. This remaining signal has at least two possible explanations. First, it may reflect Swd2 that is brought in with the APT complex, independently of COMPASS. Alternatively, Swd2 has been reported to independently interact with H2B K123 ubiquitylated nucleosomes before joining COMPASS (58). Deletion of the H2B ubiquitylating enzyme gene RAD6 results in the loss of nearly all Swd2 and Set1 recruitment (supplemental Fig. S4), even though RAD6 deletion retains H3K4 monomethylation. Although this result does not distinguish whether Swd2 and Set1 bind in sequence or together, it argues H3K4 monomethylation is not sufficient and that Set1 is important for Swd2 cross-linking. Dehé et al. (59) did not observe a similar loss of Set1 binding in the rad6Δ strain, but Vitaliano-Prunier et al. (60) reported that deletion of the Rad6 partner Bre1 partially reduced Swd2 recruitment without disrupting the association between Swd2 and Set1.

FIGURE 5.

Cells lacking Set1 no longer require Swd2 for viability or APT recruitment. A, ChIP of TAP-tagged Swd2 at PMA1 and RPS13 in SET1, set1Δ, or spp1Δ strains. Levels of Swd2 were normalized against untagged strain values. B, suppression of swd2Δ by deletion of SET1. Three-fold serial dilutions of strains with genotypes indicated on the left were spotted on YPD and grown for 3 days at the indicated temperatures. C, deletion of SET1 restores snoRNA termination in cells lacking Swd2. RNA was extracted from WT, set1Δ, SWD2 degron, and swd2Δ/set1Δ strains grown at 25 °C (permissive temperature) or after 45 min at 37 °C and analyzed by RT-PCR using primer pairs for total snR13 or snR33 RNA (primer pair 1) or unprocessed/readthrough snoRNA transcripts (primer pair 2). The upper panels show representative ethidium bromide stained agarose gels of RT-PCR samples after 21 cycles. The lower panels represent ratios between unprocessed (primer pair 2) and total (primer pair 1) snoRNA levels as quantified by quantitative PCR using three biological replicates. D, suppression of Swd2 depletion upon deletion of other COMPASS subunits. Left panels, strains containing a genomic integrated SWD2 degron allele (26) were deleted of the indicated COMPASS complex subunits. Three-fold serial dilutions were spotted in synthetic minimal media and incubated for 3 days at 25 °C (permissive temperature) or 32 °C (to induce degron degradation). Right panel, real time RT-PCR analysis was performed as in C using RNA extracted from the indicated strains after 1 h of incubation at nonpermissive temperature (37 °C).

Despite the fact that Swd2 cross-linking is abrogated by SET1 or RAD6 deletion, neither set1Δ nor rad6Δ exhibits the lethality caused by absence or depletion of Swd2 (26). Therefore, either the residual Swd2 still recruited is sufficient for viability or Swd2 is no longer essential for growth in the absence of Set1. To test this second hypothesis, the SWD2 gene was deleted in a set1Δ background. Surprisingly, the double deletion was viable at 30 °C, although growth was slowed and sensitive to higher temperatures (Fig. 5B). Similar bypass of the Swd2 requirement was seen with a Set1 catalytic mutant or histone H3 K4A mutation, although these mutations also reduce Set1 levels (data not shown). Therefore, the presence of Set1 creates a requirement for Swd2.

To investigate whether suppression of swd2Δ lethality in cells lacking Set1 might be related to snoRNA termination, RT-PCR was used to examine transcriptional readthrough at the SNR13 and SNR33 genes in strains lacking Set1, Swd2, or both. Although little readthrough was observed upon SET1 deletion, depletion of Swd2 using an inducible degron led to significant amounts of extended snR13 and snR33 transcripts (Fig. 5C) as previously reported (26). In accordance with the observed genetic suppression, termination was more efficient in the double deletion strain (Fig. 5C) or when the Swd2 degron is combined with set1Δ (Fig. 5D). Therefore, cells lacking Set1 no longer require Swd2 for viability or snoRNA termination.

To determine whether deleting other COMPASS components could bypass the requirement for Swd2, we analyzed snoRNA termination in strains lacking other COMPASS subunits known to reduce H3K4 methylation levels. Using the Swd2 degron strategy, not only set1Δ but also bre2Δ, sdc1Δ, spp1Δ, and swd3Δ could reverse the snR13 termination defect caused by the depletion of Swd2 (Fig. 5D). However, only set1Δ and spp1Δ suppressed the lethality of Swd2 depletion (Fig. 5D). This is surprising, given that cells lacking Spp1 retain partial COMPASS function (H3K4me1 and me2 are unaffected) whereas lack of Set1 or some other subunits leads to complete loss of K4 methylation (30).

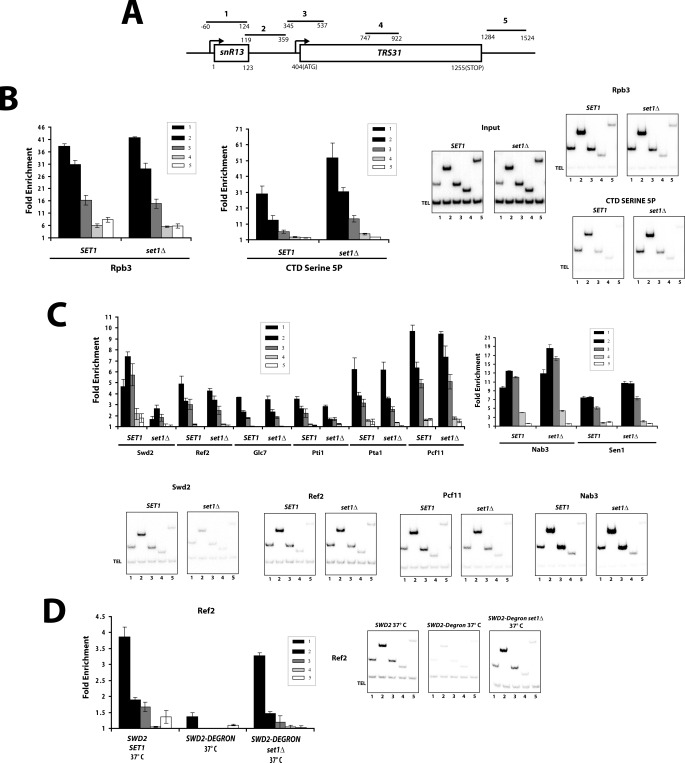

One possible mechanism for bypass of the Swd2 requirement by SET1 deletion is that increased CTD S5P improves recruitment of the Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 termination complex. CTD S5P levels are increased at SNR13 as previously seen for mRNA genes (Fig. 6, A and B). Nab3 and Sen1 cross-linking is slightly increased in set1Δ relative to SET1 (Fig. 6C), although it is unclear whether this effect can completely account for the dramatic improvement seen in termination in the absence of Swd2 (Fig. 5). In this model, Swd2 and other APT subunits would contribute to Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 recruitment either directly or indirectly, an idea supported by the fact that APT mutants show defects in snoRNA termination (27–30, 48).

FIGURE 6.

Deletion of SET1 bypasses the requirement for Swd2 in APT recruitment. A, schematic representation of the primer pairs used to analyze ChIP recruitment to snR13 gene. B, ChIPs for Rpb3 and CTD serine 5P (3E8) on snR13 using primers represented in A. At right are TBE polyacrylamide gels showing PCR products. Input shows amplification of chromatin before immunoprecipitation. TEL marks a nontranscribed telomeric region used as a normalization control. Quantitation of three biological replicates is shown in the graphs at left, with bars representing the standard error. C, recruitment of APT complex components in SET1 and set1Δ strains was assayed by ChIP using TAP-tagged versions of the APT subunits Swd2, Ref2, Glc7, Pti1, Pta1, and Pcf11. Also, ChIPs of two snoRNA termination factors, with anti-Nab3 antibody and Myc-tagged Sen1, were performed in parallel (right panels). Several representative gels are shown, and results from multiple biological replicates were quantitated as in B. D, recruitment of TAP-tagged Ref2 to snR13 was analyzed in wild-type (SWD2 and SET1) or SWD2 degron strains carrying SET1 or set1Δ. Chromatin was prepared after a 1-h temperature shift to nonpermissive temperature and assayed as in B.

Another possible (but not mutually exclusive) explanation for bypass of the Swd2 requirement in set1Δ cells is that recruitment of the termination factor APT is dependent upon Swd2, but only when COMPASS is also present. Recruitment of the APT subunit Ref2 to SNR13 is severely reduced upon Swd2 degron depletion in a SET1 background (Fig. 6D). In contrast, with the exception of Swd2, recruitment of APT complex subunits on SNR13 is unaffected by SET1 deletion (Fig. 6C). Remarkably, when Swd2 is depleted in a set1Δ background, recruitment of APT subunit Ref2 is almost normal. This result indicates that the essential function of Swd2 is to counteract some antagonistic function of COMPASS that inhibits recruitment of the APT complex. This model is consistent with the finding that Swd2 can also be bypassed by overexpression of Ref2, which cooperates with Swd2 in bringing APT to genes (30).

DISCUSSION

To better understand the role of H3K4 methylation in gene expression, we analyzed recruitment of the COMPASS complex. All of the components of COMPASS are recruited to transcribing genes dependent upon Set1 (Fig. 1). Cross-linking of the essential Swd2 protein showed a different pattern than other COMPASS subunits, with a higher signal persisting in downstream regions of genes (Figs. 1 and 5). Although the ChIP signal of Swd2 was significantly reduced in set1Δ cells, a low level of cross-linking was still observed. This is presumably because Swd2 is also recruited as part of the APT termination factor but may also represent binding of Swd2 to H2Bub as proposed by Lee et al. (58).

To address possible downstream effects of Set1, we examined recruitment of specific factors in cells lacking Set1. Although set1Δ did not affect most RNApII initiation and elongation factors tested, increased promoter cross-linking was seen for the Tfa1 subunit of TFIIE (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S2). In agreement, a genetic interaction between TFA1 and SET1 was observed. ChIP experiments also showed a general increase in the phosphorylation of the RNApII large subunit CTD, particularly for TFIIH-dependent phosphorylation near promoter regions (Fig. 2). Given the role of TFIIE in stimulating the TFIIH kinase activity (51), it is possible that the Tfa1 and CTD Ser5P increases are related, but it is not entirely clear whether these increases represent an actual increase in protein epitope levels or instead the ability of the proteins to be cross-linked. The fact that neither Tfa2 nor Rpb3 show increases may argue against the latter explanation. Furthermore, genetic suppression interactions of set1Δ with RPS5 mutants or RTR1 overexpression (Fig. 2) suggest that the increased CTD phosphorylation has functional consequences in vivo. It remains to be determined whether modulation of CTD phosphorylation is linked to effects connecting other histone modifications with polymerase processivity and elongation kinetics.

The most surprising results of this study relate to Swd2, the only essential subunit of COMPASS. Swd2 is also a component of APT, a factor essential for snoRNA termination (26–29). Therefore, the viability requirement for Swd2 is probably due either to its role in APT or to the fact that deletion of SWD2 simultaneously affects COMPASS and APT. Cells lacking Set1 have significantly reduced levels of Swd2 cross-linking (Fig. 1C), and depletion of Swd2 results in a loss of APT recruitment and defective termination at snoRNAs (Figs. 5C and 6D). Yet surprisingly, set1Δ cells have normal recruitment of APT subunits other than Swd2. This is not simply due to low residual levels of Swd2 recruitment, because deletion of SET1 actually restores viability to cells completely lacking Swd2 (Fig. 5). Remarkably, in the absence of Set1, recruitment of APT is independent of Swd2 (Fig. 6D).

Clearly, the double role of Swd2 is more complex than anticipated. The COMPASS and APT functions of Swd2 appear to be genetically separable (26, 27). Furthermore, Schizosaccharomyces pombe has two Swd2 homologues: one for COMPASS and one for APT. Although their functions appear to be nonredundant, neither pombe Swd2 is essential, and the double deletion is viable (61). These results argue that Swd2 can have completely independent functions within the two complexes but beg the question of why deleting Set1 bypasses the essential function of Swd2 in recruiting APT. Swd2 can also be bypassed by overexpressing Ref2 (a nonessential APT subunit) (26) or a nonfunctional C-terminal fragment of Sen1 (30). Ref2 appears to cooperate with Swd2 to localize the essential subunits of APT, and the Sen1 fragment may be titrating away a repressor of the snoRNA termination pathway (30). Therefore, the essential function of Swd2 is almost certainly recruitment of APT, yet it is only essential in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that contain COMPASS.

We propose the following model to explain the apparently inhibitory effect of Set1 on APT recruitment. Swd2 is a WD repeat domain protein, a feature that is typically used as a protein interaction surface. Both H3K4 methylation and the snoRNA termination pathway act early during transcription, so Swd2 may recognize a feature of early elongation complexes. Indeed, the mammalian Swd2 homologue WDR82 has been shown to specifically bind the serine 5-phosphorylated form of the Rpb1 CTD (62), the same CTD variant that targets COMPASS (13) and the snoRNA termination factor Nrd1 (33). Swd2 may recognize CTD Ser5P or some other feature of early elongation, in the context of both COMPASS and APT. If so, the two complexes may occupy nearby or overlapping locations during transcription, either simultaneously or sequentially. In this model, the role of Swd2 within APT is to stabilize its binding to early elongation complexes, perhaps competing with Swd2 within COMPASS. In cells lacking Set1, COMPASS is not assembled and so does not inhibit APT binding. In this case, other APT subunits such as Ref2 would be sufficient for proper placement of APT, thereby explaining why Swd2 is no longer essential for viability or snoRNA termination. In other organisms, divergent Swd2-like proteins might recognize different targets, or instead the target space may be larger (for example, most organisms have a longer CTD).

This model can also explain why certain mutations such as swd2-1 affect H3K4 methylation levels but do not display any strong snoRNA termination defects, whereas mutations such as swd2-5 that do not change this chromatin modification mark have strong termination defects that can be rescued by overexpression of REF2 (26). These mutants would presumably affect only the interactions within COMPASS or APT, respectively. It is also interesting to speculate that the effects of set1Δ on CTD phosphorylation could be related to APT, because the serine 5 phosphatase Ssu72 is also a subunit of this termination complex (28–30).

Overall, our results suggest cross-talk between the Set1-COMPASS complex and APT, mediated by their common subunit Swd2. It is interesting to note that deletion of SET1 affects two events required for proper snoRNA termination: binding of the Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 complex to the phosphorylated CTD and the recruitment of the APT. It is possible that by modulating both processes, the COMPASS complex helps ensure the correct sequence of events in the early transcription termination pathway. It would be particularly interesting to analyze whether the same mechanism plays a role also in other transcription-coupled events such as mRNA splicing, which can also be influenced by the levels of CTD phosphorylation and certain histone modifications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dirk Eick for antibodies against phosphorylated CTD, Dr. Jeff Corden for anti-Nab3 antibodies, Dr. Claire Moore for the Swd2 degron plasmid, Robin Buratowski for help with manuscript tables, and S. Marquardt and D. Hazelbaker for technical help.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM46498 and GM56663 (to S. B.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S4.

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- COMPASS

- complex associated with Set1

- RNApII

- RNA polymerase II

- 6AU

- 6-azauracil

- snoRNA

- small nucleolar RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Strahl B. D., Ohba R., Cook R. G., Allis C. D. (1999) Methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 is highly conserved and correlates with transcriptionally active nuclei in Tetrahymena. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14967–14972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Briggs S. D., Bryk M., Strahl B. D., Cheung W. L., Davie J. K., Dent S. Y., Winston F., Allis C. D. (2001) Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and required for cell growth and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 15, 3286–3295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fingerman I. M., Wu C. L., Wilson B. D., Briggs S. D. (2005) Global loss of Set1-mediated H3 Lys4 trimethylation is associated with silencing defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28761–28765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krogan N. J., Dover J., Khorrami S., Greenblatt J. F., Schneider J., Johnston M., Shilatifard A. (2002) COMPASS, a histone H3 (lysine 4) methyltransferase required for telomeric silencing of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10753–10755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller T., Krogan N. J., Dover J., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Johnston M., Greenblatt J. F., Shilatifard A. (2001) COMPASS. A complex of proteins associated with a trithorax-related SET domain protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12902–12907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nagy P. L., Griesenbeck J., Kornberg R. D., Cleary M. L. (2002) A trithorax-group complex purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for methylation of histone H3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 90–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dehé P. M., Dichtl B., Schaft D., Roguev A., Pamblanco M., Lebrun R., Rodríguez-Gil A., Mkandawire M., Landsberg K., Shevchenko A., Rosaleny L. E., Tordera V., Chávez S., Stewart A. F., Géli V. (2006) Protein interactions within the Set1 complex and their roles in the regulation of histone 3 lysine 4 methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35404–35412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dehé P. M., Géli V. (2006) The multiple faces of Set1. Biochem. Cell Biol. 84, 536–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schneider J., Wood A., Lee J. S., Schuster R., Dueker J., Maguire C., Swanson S. K., Florens L., Washburn M. P., Shilatifard A. (2005) Molecular regulation of histone H3 trimethylation by COMPASS and the regulation of gene expression. Mol. Cell 19, 849–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schlichter A., Cairns B. R. (2005) Histone trimethylation by Set1 is coordinated by the RRM, autoinhibitory, and catalytic domains. EMBO J. 24, 1222–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trésaugues L., Dehé P. M., Guérois R., Rodriguez-Gil A., Varlet I., Salah P., Pamblanco M., Luciano P., Quevillon-Cheruel S., Sollier J., Leulliot N., Couprie J., Tordera V., Zinn-Justin S., Chàvez S., van Tilbeurgh H., Géli V. (2006) Structural characterization of Set1 RNA recognition motifs and their role in histone H3 lysine 4 methylation. J. Mol. Biol. 359, 1170–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boa S., Coert C., Patterton H. G. (2003) Saccharomyces cerevisiae Set1p is a methyltransferase specific for lysine 4 of histone H3 and is required for efficient gene expression. Yeast 20, 827–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ng H. H., Robert F., Young R. A., Struhl K. (2003) Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell 11, 709–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Santos-Rosa H., Schneider R., Bannister A. J., Sherriff J., Bernstein B. E., Emre N. C., Schreiber S. L., Mellor J., Kouzarides T. (2002) Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature 419, 407–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu C. L., Kaplan T., Kim M., Buratowski S., Schreiber S. L., Friedman N., Rando O. J. (2005) Single-nucleosome mapping of histone modifications in S. cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 3, e328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pokholok D. K., Harbison C. T., Levine S., Cole M., Hannett N. M., Lee T. I., Bell G. W., Walker K., Rolfe P. A., Herbolsheimer E., Zeitlinger J., Lewitter F., Gifford D. K., Young R. A. (2005) Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell 122, 517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xiao T., Shibata Y., Rao B., Laribee R. N., O'Rourke R., Buck M. J., Greenblatt J. F., Krogan N. J., Lieb J. D., Strahl B. D. (2007) The RNA polymerase II kinase Ctk1 regulates positioning of a 5′ histone methylation boundary along genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 721–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hampsey M., Reinberg D. (2003) Tails of intrigue. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II mediates histone methylation. Cell 113, 429–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taverna S. D., Li H., Ruthenburg A. J., Allis C. D., Patel D. J. (2007) How chromatin-binding modules interpret histone modifications. Lessons from professional pocket pickers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 1025–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim T., Buratowski S. (2009) Dimethylation of H3K4 by Set1 recruits the Set3 histone deacetylase complex to 5′ transcribed regions. Cell 137, 259–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pray-Grant M. G., Daniel J. A., Schieltz D., Yates J. R., 3rd, Grant P. A. (2005) Chd1 chromodomain links histone H3 methylation with SAGA- and SLIK-dependent acetylation. Nature 433, 434–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vermeulen M., Mulder K. W., Denissov S., Pijnappel W. W., van Schaik F. M., Varier R. A., Baltissen M. P., Stunnenberg H. G., Mann M., Timmers H. T. (2007) Selective anchoring of TFIID to nucleosomes by trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4. Cell 131, 58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shi X., Kachirskaia I., Walter K. L., Kuo J. H., Lake A., Davrazou F., Chan S. M., Martin D. G., Fingerman I. M., Briggs S. D., Howe L., Utz P. J., Kutateladze T. G., Lugovskoy A. A., Bedford M. T., Gozani O. (2007) Proteome-wide analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies several PHD fingers as novel direct and selective binding modules of histone H3 methylated at either lysine 4 or lysine 36. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2450–2455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carrozza M. J., Li B., Florens L., Suganuma T., Swanson S. K., Lee K. K., Shia W. J., Anderson S., Yates J., Washburn M. P., Workman J. L. (2005) Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell 123, 581–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keogh M. C., Kurdistani S. K., Morris S. A., Ahn S. H., Podolny V., Collins S. R., Schuldiner M., Chin K., Punna T., Thompson N. J., Boone C., Emili A., Weissman J. S., Hughes T. R., Strahl B. D., Grunstein M., Greenblatt J. F., Buratowski S., Krogan N. J. (2005) Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell 123, 593–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheng H., He X., Moore C. (2004) The essential WD repeat protein Swd2 has dual functions in RNA polymerase II transcription termination and lysine 4 methylation of histone H3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2932–2943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dichtl B., Aasland R., Keller W. (2004) Functions for S. cerevisiae Swd2p in 3′ end formation of specific mRNAs and snoRNAs and global histone 3 lysine 4 methylation. RNA 10, 965–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nedea E., He X., Kim M., Pootoolal J., Zhong G., Canadien V., Hughes T., Buratowski S., Moore C. L., Greenblatt J. (2003) Organization and function of APT, a subcomplex of the yeast cleavage and polyadenylation factor involved in the formation of mRNA and small nucleolar RNA 3′-ends. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33000–33010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dheur S., Vo le T. A., Voisinet-Hakil F., Minet M., Schmitter J. M., Lacroute F., Wyers F., Minvielle-Sebastia L. (2003) Pti1p and Ref2p found in association with the mRNA 3′ end formation complex direct snoRNA maturation. EMBO J. 22, 2831–2840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nedea E., Nalbant D., Xia D., Theoharis N. T., Suter B., Richardson C. J., Tatchell K., Kislinger T., Greenblatt J. F., Nagy P. L. (2008) The Glc7 phosphatase subunit of the cleavage and polyadenylation factor is essential for transcription termination on snoRNA genes. Mol. Cell 29, 577–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steinmetz E. J., Conrad N. K., Brow D. A., Corden J. L. (2001) RNA-binding protein Nrd1 directs poly(A)-independent 3′-end formation of RNA polymerase II transcripts. Nature 413, 327–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vasiljeva L., Buratowski S. (2006) Nrd1 interacts with the nuclear exosome for 3′ processing of RNA polymerase II transcripts. Mol. Cell 21, 239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vasiljeva L., Kim M., Mutschler H., Buratowski S., Meinhart A. (2008) The Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 termination complex interacts with the Ser5-phosphorylated RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 795–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuldell N. H., Buratowski S. (1997) Genetic analysis of the large subunit of yeast transcription factor IIE reveals two regions with distinct functions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5288–5298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chapman R. D., Heidemann M., Albert T. K., Mailhammer R., Flatley A., Meisterernst M., Kremmer E., Eick D. (2007) Transcribing RNA polymerase II is phosphorylated at CTD residue serine-7. Science 318, 1780–1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Warren S. L., Landolfi A. S., Curtis C., Morrow J. S. (1992) Cytostellin. A novel, highly conserved protein that undergoes continuous redistribution during the cell cycle. J. Cell Sci. 103, 381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lenstra T. L., Benschop J. J., Kim T., Schulze J. M., Brabers N. A., Margaritis T., van de Pasch L. A., van Heesch S. A., Brok M. O., Groot Koerkamp M. J., Ko C. W., van Leenen D., Sameith K., van Hooff S. R., Lijnzaad P., Kemmeren P., Hentrich T., Kobor M. S., Buratowski S., Holstege F. C. (2011) The specificity and topology of chromatin interaction pathways in yeast. Mol. Cell 42, 536–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carvin C. D., Kladde M. P. (2004) Effectors of lysine 4 methylation of histone H3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are negative regulators of PHO5 and GAL1–10. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33057–33062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Muramoto T., Müller I., Thomas G., Melvin A., Chubb J. R. (2010) Methylation of H3K4 is required for inheritance of active transcriptional states. Curr. Biol. 20, 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Akhtar M. S., Heidemann M., Tietjen J. R., Zhang D. W., Chapman R. D., Eick D., Ansari A. Z. (2009) TFIIH kinase places bivalent marks on the carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell 34, 387–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glover-Cutter K., Larochelle S., Erickson B., Zhang C., Shokat K., Fisher R. P., Bentley D. L. (2009) TFIIH-associated Cdk7 kinase functions in phosphorylation of C-terminal domain Ser7 residues, promoter-proximal pausing, and termination by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 5455–5464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim M., Suh H., Cho E. J., Buratowski S. (2009) Phosphorylation of the yeast Rpb1 C-terminal domain at serines 2, 5, and 7. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26421–26426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Demae M., Murata Y., Hisano M., Haitani Y., Shima J., Takagi H. (2007) Overexpression of two transcriptional factors, Kin28 and Pog1, suppresses the stress sensitivity caused by the rsp5 mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277, 70–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Somesh B. P., Sigurdsson S., Saeki H., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Svejstrup J. Q. (2007) Communication between distant sites in RNA polymerase II through ubiquitylation factors and the polymerase CTD. Cell 129, 57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Helliwell S. B., Losko S., Kaiser C. A. (2001) Components of a ubiquitin ligase complex specify polyubiquitination and intracellular trafficking of the general amino acid permease. J. Cell Biol. 153, 649–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Neumann S., Petfalski E., Brügger B., Grosshans H., Wieland F., Tollervey D., Hurt E. (2003) Formation and nuclear export of tRNA, rRNA and mRNA is regulated by the ubiquitin ligase Rsp5p. EMBO Rep. 4, 1156–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mosley A. L., Pattenden S. G., Carey M., Venkatesh S., Gilmore J. M., Florens L., Workman J. L., Washburn M. P. (2009) Rtr1 is a CTD phosphatase that regulates RNA polymerase II during the transition from serine 5 to serine 2 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 34, 168–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ganem C., Devaux F., Torchet C., Jacq C., Quevillon-Cheruel S., Labesse G., Facca C., Faye G. (2003) Ssu72 is a phosphatase essential for transcription termination of snoRNAs and specific mRNAs in yeast. EMBO J. 22, 1588–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krishnamurthy S., He X., Reyes-Reyes M., Moore C., Hampsey M. (2004) Ssu72 Is an RNA polymerase II CTD phosphatase. Mol. Cell 14, 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ohkuma Y., Hashimoto S., Wang C. K., Horikoshi M., Roeder R. G. (1995) Analysis of the role of TFIIE in basal transcription and TFIIH-mediated carboxy-terminal domain phosphorylation through structure-function studies of TFIIE-α. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 4856–4866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ohkuma Y., Roeder R. G. (1994) Regulation of TFIIH ATPase and kinase activities by TFIIE during active initiation complex formation. Nature 368, 160–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sakurai H., Fukasawa T. (1998) Functional correlation among Gal11, transcription factor (TF) IIE, and TFIIH in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gal11 and TFIIE cooperatively enhance TFIIH-mediated phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9534–9538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grohmann D., Nagy J., Chakraborty A., Klose D., Fielden D., Ebright R. H., Michaelis J., Werner F. (2011) The initiation factor TFE and the elongation factor Spt4/5 compete for the RNAP clamp during transcription initiation and elongation. Mol. Cell 43, 263–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ansari A., Hampsey M. (2005) A role for the CPF 3′-end processing machinery in RNAP II-dependent gene looping. Genes Dev. 19, 2969–2978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. O'Sullivan J. M., Tan-Wong S. M., Morillon A., Lee B., Coles J., Mellor J., Proudfoot N. J. (2004) Gene loops juxtapose promoters and terminators in yeast. Nat. Genet. 36, 1014–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Buratowski S. (2009) Progression through the RNA polymerase II CTD cycle. Mol. Cell 36, 541–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Terzi N., Churchman L. S., Vasiljeva L., Weissman J., Buratowski S. (2011) H3K4 trimethylation by Set1 promotes efficient termination by the Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 3569–3583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee J. S., Shukla A., Schneider J., Swanson S. K., Washburn M. P., Florens L., Bhaumik S. R., Shilatifard A. (2007) Histone crosstalk between H2B monoubiquitination and H3 methylation mediated by COMPASS. Cell 131, 1084–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dehé P. M., Pamblanco M., Luciano P., Lebrun R., Moinier D., Sendra R., Verreault A., Tordera V., Géli V. (2005) Histone H3 lysine 4 mono-methylation does not require ubiquitination of histone H2B. J. Mol. Biol. 353, 477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vitaliano-Prunier A., Menant A., Hobeika M., Géli V., Gwizdek C., Dargemont C. (2008) Ubiquitylation of the COMPASS component Swd2 links H2B ubiquitylation to H3K4 trimethylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1365–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Roguev A., Wiren M., Weissman J. S., Krogan N. J. (2007) High-throughput genetic interaction mapping in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat. Methods 4, 861–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lee J. H., Skalnik D. G. (2008) Wdr82 is a C-terminal domain-binding protein that recruits the Setd1A Histone H3-Lys4 methyltransferase complex to transcription start sites of transcribed human genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 609–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.