Abstract

Vibrio parahaemolyticus, a marine bacterium, is the causative agent of gastroenteritis associated with the consumption of seafood. It contains a homologue of the toxRS operon that in V. cholerae is the key regulator of virulence gene expression. We examined a nonpolar mutation in toxRS to determine the role of these genes in V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633, an O3:K6 isolate, and showed that compared to the wild type, ΔtoxRS was significantly more sensitive to acid, bile salts, and sodium dodecyl sulfate stresses. We demonstrated that ToxRS is a positive regulator of ompU expression, and that the complementation of ΔtoxRS with ompU restores stress tolerance. Furthermore, we showed that ToxRS also regulates type III secretion system genes in chromosome I via the regulation of the leuO homologue VP0350. We examined the effect of ΔtoxRS in vivo using a new orogastric adult murine model of colonization. We demonstrated that streptomycin-treated adult C57BL/6 mice experienced prolonged intestinal colonization along the entire intestinal tract by the streptomycin-resistant V. parahaemolyticus. In contrast, no colonization occurred in non-streptomycin-treated mice. A competition assay between the ΔtoxRS and wild-type V. parahaemolyticus strains marked with the β-galactosidase gene lacZ demonstrated that the ΔtoxRS strain was defective in colonization compared to the wild-type strain. This defect was rescued by ectopically expressing ompU. Thus, the defect in stress tolerance and colonization in ΔtoxRS is solely due to OmpU. To our knowledge, the orogastric adult murine model reported here is the first showing sustained intestinal colonization by V. parahaemolyticus.

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio parahaemolyticus, a Gram-negative bacterium, is commonly isolated from coastal and estuarine waters worldwide (31, 32, 54, 87). This organism can accumulate to high numbers in shellfish and, as a result, is frequently associated with gastroenteritis in humans following shellfish consumption (5, 46). Disease caused by the ingestion of V. parahaemolyticus results in transient diarrhea and abdominal pain. In addition, septicemia and mortality have been reported in cases following bacterial exposure to open wounds or in immunocompromised individuals (11, 23–25, 27, 53).

Several studies have compared clinical and environmental isolates of V. parahaemolyticus to determine pathogenicity in humans (5, 6, 29, 41, 80). Strains isolated from clinical samples are frequently associated with the ability to cause hemolysis on Wagatsuma blood agar, while environmental isolates rarely produce hemolysis (23, 53). This phenotype, known as the Kanagawa phenomenon (KP), is attributed to the production of a specific hemolysin, the thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) (26). Gastrointestinal (GI) disease is also associated with KP-negative strains from which a second hemolysin, termed the TDH-related hemolysin (TRH), was identified. The production of these hemolysins was believed to be the primary cause of virulence by V. parahaemolyticus (1, 21, 23, 27, 45, 51, 61, 74).

The examination of the completed genome sequence of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633, an O3:K6 serotype currently associated with worldwide outbreaks of food-borne gastroenteritis, has led to the identification of several additional virulence genes (40, 52). The type III secretion system (T3SS) genes are found in each chromosome (designated T3SS-1 and T3SS-2, respectively) (40). The T3SS-2 gene cluster is located alongside two copies of the tdh gene (tdhA and tdhS) within an 80-kb pathogenicity island (VPA1312 to VPA1396) named VPaI-7, a region that is predominantly associated with clinical isolates (6, 29, 30, 40). More recently, a third gene cluster, encoding a T3SS, has been identified in a tdh-negative, trh-positive V. parahaemolyticus strain (56). Several functional T3SS effector proteins have been identified (2, 21, 34, 45, 60, 65, 76), including the T3SS-1 effectors VopQ (VP1680), VopR (VP1683), VopS (VP1686), VP1659, and VPA0450. It has been found that the production of these effector proteins by V. parahaemolyticus induces autophagy, cell rounding, cell lysis, and cell death in vitro in a variety of different eukaryotic cell types (7–9, 36, 39, 76). Each T3SS in V. parahaemolyticus has been shown to be functional, although data suggest that the contribution of each to virulence differs markedly (21, 61, 65, 85). The regulation of the T3SS-1 system was shown to fall under the control of the ExsACDE system, with ExsA and ExsD acting as positive and negative regulators of T3SS-1 gene expression, respectively. Recently, Gode-Potratz and colleagues demonstrated that V. parahaemolyticus possesses an additional T3SS-1 negative regulator encoded by VP0350 (19). The VP0350 gene encodes a LysR-family transcriptional regulator that is annotated as an LeuO homologue, but it was named CalR in their study as it was shown to respond to extracellular calcium levels (19). In the study of Gode-Potratz et al., a VP0350 deletion mutant exhibited increased cytotoxicity and T3SS-1 expression and is believed to act upstream of the ExsACDE system (19).

The mechanisms controlling global virulence gene regulation in V. parahaemolyticus are still poorly understood. The two-component regulator ToxRS has been shown to be essential for bacterial persistence and virulence during host infection with Vibrio cholerae (10, 49, 50, 75). ToxRS in V. cholerae controls the expression of several outer membrane proteins (Omp), namely, OmpU and OmpT, as well as enhancing the expression of ToxT, a transcription factor that is crucial for the regulation of the expression of the virulence factors toxin coregulated pilus and cholera toxin (37, 66–69). ToxRS also plays some role in V. cholerae survivability in the face of gastrointestinal barriers, such as bile salts, antimicrobial peptides, and acid stress, which are mediated by the ToxR activation of the expression of OmpU (43, 47, 67, 68). In V. cholerae the OmpU protein forms a multimeric porin in the outer membrane. OmpU has been implicated as an important stress response protein in response to extracellular stresses, such as organic acids, antimicrobial peptides, and anionic detergents (43, 47, 48, 67–69). There is some evidence suggesting that OmpU acts as a signal in the activation of RpoE, an alternative sigma factor that is important for the membrane stress response (42). The role of OmpU in in vivo survival is not entirely known, as V. cholerae ompU deletion mutants exhibit only a slight decrease in colonization (67, 68). OmpU has been shown, however, to play an important role in host colonization in Vibrio splendidus (16, 17). Vibrio parahaemolyticus contains a ToxRS homologue, but the role ToxRS plays in the pathogenicity of this organism has not been fully elucidated (38, 67, 68). Data suggesting that ToxRS is involved in regulating TDH expression (38) have been confounded by evidence suggesting that two ToxR-like regulators, vtrA and vtrB (located within VPaI-7), control the levels of TDH expressed in V. parahaemolyticus (33).

The aim of this study was to determine the function of ToxRS in V. parahaemolyticus. To accomplish this, we examined the effects of a nonpolar in-frame mutation in toxRS compared to those for the wild type under a number of stress conditions. We determined whether or not defects in the stress tolerance response were due to the ToxRS regulation of OmpU. In addition, we developed an adult murine model whereby animals were stably colonized by V. parahaemolyticus following orogastric inoculation. Here, we show that adult animals are susceptible to bacterial colonization following a single oral dose of antibiotic. We examined V. parahaemolyticus colonization throughout the intestine and monitored the adult mice by tracking bacterial shedding in fecal samples and determining V. parahaemolyticus CFU in the intestine. The effect of the deletion of the global regulator ToxRS on the ability of V. parahaemolyticus to colonize the intestine was also examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

Studies utilized a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant mutant of the clinical isolate V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633, an O3:K6 serotype, as a wild-type strain as described previously (44). Briefly, the strain was grown aerobically (250 rpm) at 37°C for 12 h in 5 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) containing 3% NaCl. This 5 ml of overnight culture was centrifuged for 10 min at 4,000 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of LB, 3% NaCl and plated onto LB, 3% NaCl plates containing 1 mg/ml of streptomycin (Fisher Scientific). Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and streptomycin-resistant colonies were further plated on LB, 3% NaCl plates containing 200 μg/ml of streptomycin. In addition, some experiments utilized a ΔtoxRS derivative of this streptomycin-resistant RIMD2210633 strain, generated through splicing by overlap extension (SOE) PCR in a previous study (79). Two additional strains used in this study, ΔvscN1 and ΔvscN2, are T3SS-1 and T3SS-2 defective, respectively, and were previously constructed from RIMD2210633 using SOE PCR and allelic exchange (44). All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All genetic manipulations utilized Escherichia coli strain DH5α λpir and the diaminopimelic acid (DAP) auxotroph β2155 λpir. Unless otherwise stated, bacteria were grown on LB broth containing 3% NaCl at 37°C with aeration. An E. coli β2155 DAP auxotroph was cultured on media containing 0.3 mM DAP (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Antibiotics were added to the LB broth at the following concentrations: streptomycin, 200 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml; ampicillin, 25 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains | ||

| RIMD2210633 | O3:K6 clinical isolate | 40 |

| ΔtoxRS | RIMD2210633 ΔtoxRS(VP0819-0820) | 79 |

| WBW2467 | RIMD2210633 ΔtoxRS pWBW2467 | This study |

| WBW0350 | RIMD2210633 ΔtoxRS pWBW0350 | This study |

| WBW0819-0820 | RIMD2210633 ΔtoxRS pWBW0819-0820 | This study |

| ΔleuO | RIMD2210633 ΔleuO (VP0350) | This study |

| ΔvscN1 | RIMD2210633 ΔVP1668, T3SS-1 mutant | 44 |

| ΔvscN2 | RIMD2210633 ΔVPA1338, T3SS-2 mutant | 44 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD33 | Expression vector, araC promoter, Cmr | 20 |

| pWBW2467 | pBAD33 harboring ompU gene | This study |

| pWBW0350 | pBAD33 harboring leuO gene | This study |

| pWBW0819-0820 | pBAD33 harboring toxRS genes | This study |

| pJet1.2/blunt | Cloning vector | |

| pJet1.2-2403SOE | V. parahaemolyticus VP2403 SOE product | This study |

| pJet1.2-VclacZ | V. cholerae β-galactosidase (lacZ) gene | This study |

| pJET1.2-VclacZ | V. choleraelacZ flanked by VP2403AB and VP2403CD | This study |

| pDS132 | Suicide plasmid; Cmr; SacB | 64 |

| pDS1VpVclacZ | V. choleraelacZ flanked by VP2403AB and VP2403CD | This study |

| pDSΔleuO | pDS132 harboring truncated leuO (VP0350) | This study |

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from V. parahaemolyticus strains grown for 4 h in LB containing 3% NaCl using the RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) by following the manufacturer's protocols. The RNA samples were quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and subsequently treated with Turbo DNase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), per the manufacturer's protocol, to remove any contaminating genomic DNA from the samples. cDNA was synthesized using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol, using 500 ng of RNA as a template and priming with 200 ng of random hexamers. cDNA samples were then diluted 1:250 and used for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Real-time PCRs used the HotStart-IT SYBR green qPCR master mix (USB, Santa Clara, CA) and were run on an Applied Biosystems 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Foster City, CA). Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer 3 software according to the real-time PCR guidelines and are listed in Table 2. Data were analyzed using Applied Biosystems 7500 software. Expression levels of each gene, as determined by their threshold cycle (CT) values, were normalized using the 16S rRNA gene to correct for sampling errors. Differences in the ratio of gene expression were determined using the ΔΔCT method. All assays were performed in duplicate, and all experiments were repeated.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Use and name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Melting temp (°C) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complementation | |||

| OmpU For | GAG CTC TGA TTA TGG ACA GCT AAC TA | 57 | 1,045 |

| OmpU Rev | AAG CTT TTA GAA GTC GTA ACG TAG AC | 59 | |

| VP0350 For | GAG CTC CTT TTG TGC GAG ATG GGA TT | 61 | 1,047 |

| VP0350 Rev | AAG CTT TTA TTT TGA TGC GAC CAC TTC | 61 | |

| ToxRS For | GAG CTC TCA CCA TAA TTA CAA CAT CAT CCA | 58 | 1,485 |

| ToxRS Rev | AAG CTT CAT CTT GCC CCC TTA TCA CT | 60 | |

| Splice overlap extension | |||

| SOEvp0350A | GCA TGC GGT GGG GTA AAT GTG TTT CG | 62 | 497 |

| SOEvp0350B | GTG TGC TGC ACG AGT GAT AT | 55 | |

| SOEvp0350C | ATA TCA CTC GTG CAG CAC ACG AAA ATG CGG TGA ACA GTG A | 67 | 455 |

| SOEvp0350D | GAG CTC CCT TTT GGC TTA CAG GCG TA | 62 | |

| SOEvp0350FlFor | TGG GAT TCG CAA GAA GAA CT | 54 | 2,038 |

| SOEvp0350FlRev | AAT ACC TTG CCA TGC TCC TG | 55 | |

| VPLacZA | TCT AGA CTC TGT ACG CGT GAT GCA GT | 61 | 603 |

| VPLacZB | GGA TCC GGT ACC GAA TTC CGA ACC GAG TTG ATG TTG TG | 67 | |

| VPLacZC | GAA TTC GGT ACC GGA TCC ACG TTT GGG AAT GGT GTG AT | 67 | 546 |

| VPLacZD | GAG CTC GGC TTT CTT CAA GCA CCA AG | 62 | |

| VCLacZForEcoRI | GAA TTC TGA TCT GAA GTC ATC CGT AAT CA | 56 | 3,454 |

| VCLacZRevBamHI | GGA TCC TTA TTG TGG GGA TGA CGC TT | 61 | |

| RT-PCR | |||

| OmpUQPCRFor | GTT GGT TTC TGG GAA GGT GA | 55 | 109 |

| OmpUQPCRRev | CAA GAC CAG CGT ATG CGT AA | 55 | |

| VP1680For | TCA AGT CGA GAT GCG TTT TG | 53 | 186 |

| VP1680For | CCG ATT TGG AAC AGT TTC GT | 53 | |

| vp1656For | CAC TTG GTA AAG CAG CGT CA | 55 | 196 |

| vp1656Rev | TCA ATT AGA TGG GCC GAA AG | 52 | |

| vp1694 For | ACC ACC GAC CAT TTG TTG AT | 54 | 176 |

| vp1694Rev | TCA TTT TAC GAT GCG ACC AA | 52 | |

| vp1695For | TGG TTA CGT CCT GAC ATC CA | 55 | 180 |

| vp1695Rev | GTA TTT TAT CCG GCG TGC AT | 53 | |

| LeuOQPCRFor | GCT GTG ATG CAA GAG CAA AA | 54 | 175 |

| LeuOQPCRRev | GGA TAG GGC CAA ACA GTT GA | 55 |

Complementation of ΔtoxRS.

The ΔtoxRS strain was complemented with the ompU gene (VP2467), the leuO gene (VP0350), or the toxRS operon (VP0819-20) using the pBAD33 vector. PCR primers were designed to amplify a promoterless copy of VP2467 encoding OmpU (Table 2). Briefly, the ompU gene was cloned into vector pJet2.1/blunt and transformed into E. coli DH5α λpir. The fragment was then subcloned into the vector pBAD33, resulting in pWBW2467, and subsequently transformed into E. coli β2155 λpir. The E. coli β2155 λpir strain harboring pWBW2467 was cross-streaked with the ΔtoxRS strain onto LB plates containing 0.3 mM DAP, which allows for the conjugative transfer of pWBW2467. The resulting growth was streaked onto LB, 3% NaCl plates containing chloramphenicol and streptomycin (but no DAP) to positively select for ΔtoxRS cells harboring pWBW2467 and to negatively select against E. coli β2155 λpir. To induce the expression of the complemented genes, strains harboring pWBW2467 were grown in the presence of 0.05% arabinose. This protocol was repeated for the gene VP0350 (leuO) and the toxRS operon.

Construction of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 VP0350 deletion mutant.

An in-frame deletion mutant was created in VP0350, which carries a homologue of leuO, using SOE PCR and allelic exchange (28). Primers were designed using the V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 genome sequence (40) as the template and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). These primers were used to perform SOE PCR and obtain a 303-bp truncated version of the VP0350 gene. The ΔVP0350 PCR fragment was cloned into the suicide vector pDS132 (28), which was designated pDSΔVP0350. pDSΔVP0350 was subsequently transformed into the E. coli strain β2155 λpir. pDSΔVP0350 was conjugated into V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 via cross-streaking on LB plates containing 0.3 mM DAP. Growth from these plates was transferred to LB plates containing 3% NaCl, streptomycin, and chloramphenicol. The 3% NaCl allowed for optimal V. parahaemolyticus growth. The absence of DAP from these plates, plus the addition of chloramphenicol, selected only for V. parahaemolyticus cells that harbored pDSΔVP0350. Exconjugate colonies were cultured overnight in LB, 3% NaCl without chloramphenicol and subsequently serially diluted and plated on LB, 3% NaCl, 10% sucrose to select for cells which had lost pDSΔVP0350. Double-crossover deletion mutants were screened by PCR using the SOEFLVP0350F and SOEFLVP0350R primers and sequenced for verification.

Construction of β-galactosidase-expressing RIMD strain.

To coculture mutant strains with the isogenic wild-type strain for competition assays, we developed a blue-white screening assay for V. parahaemolyticus. To accomplish this, we cloned the V. cholerae β-galactosidase gene lacZ into the V. parahaemolyticus genome, with the cryptic beta-d-galactosidase subunit alpha gene (VP2403) as our chromosomal insertion point, using a modified SOE PCR protocol. Two regions of VP2403 were amplified using 2 sets of primer pairs (Table 2). These products were then spliced together by homologous EcoRI-KpnI-BamHI sequences incorporated into the 3′ end of the reverse primer in pair 1 and the 5′ end of the forward primer in pair 2. The resulting single product was cloned into the vector pJET1.2 (pJet1.2-VP2403SOE) and transformed into E. coli DH5α λpir. Primers were also designed to amplify a region in the V. cholerae N16961 genome which encompasses the β-galactosidase gene plus 380 bases of upstream sequence to include a putative σ70 promoter. The 5′ V. cholerae primer contains an EcoRI site and the 3′ V. cholerae primer contains a BamHI site, allowing for insertion into the VP2403 SOE product. The V. cholerae β-galactosidase product was also cloned into pJET1.2 (pJet1.2-VclacZ) and transformed into E. coli DH5α λpir. Both plasmids were extracted from their host strains, and the EcoRI and BamHI fragments from pJEt1.2-VplacZ were digested and ligated into the similarly digested pJet1.2-VP2403SOE, resulting in the plasmid pJET1.2-VpVclacZ, and transformed back into E. coli DH5α λpir. This plasmid was then extracted and digested with XbaI and SacI to completely excise the V. parahaemolyticus-V. cholerae lacZ fragment, which was then subcloned into the suicide vector pDS132 (named pDSVpVclacZ), transformed into E. coli β2155 λpir, and transferred to V. parahaemolyticus via conjugation. Transconjugates containing the pDSVpVclacZ plasmid were selected by plating on LB, 3% NaCl containing streptomycin and chloramphenicol. Exconjugate colonies were cured of the pDSVpVclacZ plasmid by replating onto LB, 3% NaCl plates containing 10% sucrose and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal), with double-crossover mutants appearing blue due to the functional activity of the β-galactosidase gene.

Growth and survival analysis.

Wild-type V. parahaemolyticus, ΔtoxRS, and ΔtoxRS complemented with either leuO or toxRS (strains WBW2467 and WBW0819-820, respectively) were examined for survival in 4 mM acetic acid, sodium cholate (bile salts) (Sigma), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). For survival assays, strains were first grown overnight in LB broth containing 3% NaCl with aeration at 37°C. Following overnight growth, 100 μl of each culture was inoculated into 5 ml of fresh LB, 3% NaCl and allowed to grow to mid-exponential phase. The cultures were then pelleted and resuspended in LB, 3% NaCl with the pH adjusted to 5.5 with HCl and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After 30 min, the cultures were pelleted again and subsequently resuspended in fresh LB, 3% NaCl, supplemented with 4 mM acetic acid, and allowed to incubate for an additional 60 min. At specified time points, cultures were serially diluted and plated for CFU to determine surviving bacteria. This protocol was repeated for conditions of bile stress (15% deoxycholate) or SDS stress (0.5% SDS), with the exception that no preadaption phase was used for these conditions.

Animals and inoculations.

Male C57BL/6 mice, aged 6 to 10 weeks, were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in standard cages under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Mice were caged in groups (3 to 5 per group) and provided standard mouse feed and water ad libitum. All experiments involving mice were approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Twenty-eight hours prior to orogastric inoculation, food and water were withdrawn from the animals. Four hours later, mice were orogastrically administered 100 μl of either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or streptomycin solution (200 mg/ml in PBS) with a sterile 18-gauge gavage needle (Roboz Surgical Instrument Co., Gaithersburg, MD), and food and water were immediately returned. After 20 h, mice were fasted again for 4 h, following which all animals were orogastrically dosed with 100 μl of bacterial suspension in PBS using a sterile gavage needle without anesthetization.

Bacterial inocula of wild-type or mutant strains of V. parahaemolyticus were prepared as follows. Glycerol stocks were streaked onto LB media supplemented with NaCl (final concentration of 3%) and streptomycin and grown at 37°C. Streptomycin was included in media at a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. A single colony was used to inoculate 10 ml of LB, 3% NaCl plus streptomycin and grown overnight at 37°C with agitation (230 rpm). The following day, 25 ml of LB, 3% NaCl plus streptomycin was inoculated with a 2% inoculum of overnight culture and incubated for 4 h at 37°C with agitation (230 rpm). The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured on a 1:10 dilution of bacterial culture to verify that growth was within an expected range, as previously determined by plating cultures to determine CFU per ml (data not shown). Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 5 min, washed once with PBS, and centrifuged again. The bacterial cell pellets were resuspended in PBS to a concentration between 5 × 109 and 1 × 1010 CFU/ml. Serially diluted inoculum was plated for each experiment to determine the actual dose administered. Water was provided to animals immediately following orogastric inoculation, with food returned 2 h postinoculation.

Determination of V. parahaemolyticus CFU in intestinal tissues.

Forty-eight h postinfection, mice were sacrificed by carbon dioxide asphyxiation and tissues were aseptically removed. For total intestinal CFU determination, the entire intestine (encompassing the duodenum to the descending colon) was placed in 4 ml of PBS and mechanically disrupted with a Tissue Tearor (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK). Homogenized samples were serially diluted, plated on LB, 3% NaCl plus streptomycin, and incubated at 37°C. In indicated experiments, the gastrointestinal tracts from individual animals were analyzed as separate sections of tissue to elucidate regions of the intestine preferentially colonized by bacteria. Here, the intestine was separated into the small intestine (duodenum to ileum), the cecum, and the large intestine. Tissue sections were flushed with PBS to remove the fecal contents, homogenized in 4 ml of PBS, serially diluted, plated on LB, 3% NaCl plus streptomycin, and incubated at 37°C.

Determination of bacterial CFU shed in fecal samples.

Fresh fecal pellets were collected from individual animals (2 to 4 pellets per animal) at 24-h intervals. Pellets were weighed and placed in 2 ml of sterile PBS for mechanical disruption by homogenization. All samples were serially diluted in PBS, plated on LB, 3% NaCl plus streptomycin, and incubated at 37°C. For each experiment, randomly selected colonies were patched onto the highly selective vibrio medium thiosulfate citrate bile salts sucrose (TCBS) agar (Fisher Scientific) and incubated overnight at 37°C to confirm that the counts were of V. parahaemolyticus and not due to the outgrowth of other intestinal microflora.

In vivo colonization competition assay.

The inocula for competition assays were prepared as outlined above, with the following modifications. Overnight cultures of the wild-type, WBWlacZ, ΔtoxRS, ΔvscN1, and ΔvscN2 strains were diluted 1:50 into 25 ml LB, 3% NaCl with streptomycin and grown for 4 h. Four-hour cultures of WBWlacZ, wild-type RIMD2210633, ΔtoxRS, ΔvscN1, and ΔvscN2 strains were pelleted by centrifugation, washed in PBS, and centrifuged again. The resulting bacterial pellet was resuspended in PBS to a concentration of approximately 1 × 1010 CFU based on the culture OD600. A 1-ml aliquot of each mutant and the wild-type strain WBWlacZ was combined in fresh PBS, yielding an inoculum of 1 × 1010 CFU, with a ratio of 1:1 mutant cells to WBWlacZ cells. A portion of the inoculum was serially diluted and plated onto LB, 3% NaCl plates with streptomycin (Sm) and X-Gal to determine the exact ratio of CFU in the inoculum. A 100-μl aliquot of the inoculum was added to 5 ml of LB for in vitro competition assays. The cultures were grown overnight at 37°C with aeration. Serial dilutions were plated on LB-Sm supplemented with 40 μg/ml X-Gal (Fischer), and recovered CFU were counted for the in vitro competitive index (CI). The in vitro experiments were performed in triplicate at least twice. Mice were prepared by following the streptomycin-treated adult mouse protocol outlined above. Twenty-four hours after infection, mice were sacrificed and the entire gastrointestinal tract was harvested. Samples were placed into 8 ml of PBS, mechanically homogenized, and serially diluted in PBS. Samples were then plated on plates of LB, 3% NaCl with streptomycin and X-Gal to determine the output CFU for both strains. The CI was determined using the following formula: CI = ratio out(mutant/wild-type)/ratio in(mutant/wild-type).

Statistical analysis.

Data from replicate experiments were analyzed using either a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Dunn's multiple comparison posttest or unpaired Student's t test, where indicated, using GraphPad Prism version 5. Differences were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

ToxRS controls the expression of ompU in V. parahaemolyticus.

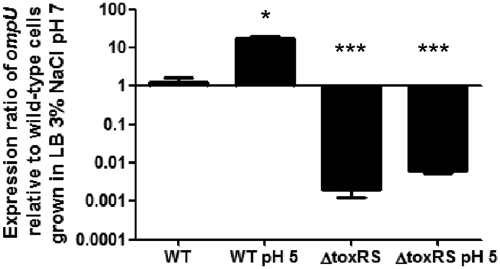

In V. cholerae, ToxRS directly regulates the expression of the outer membrane proteins OmpU and OmpT (37, 66–69). Vibrio parahaemolyticus contains an OmpU homologue (VP2467) but not an OmpT homologue. We performed real-time PCR to explore whether the ToxRS system controls the expression of ompU in V. parahaemolyticus. RNA was extracted from the ΔtoxRS and isogenic wild-type strains grown under standard (pH 7) and low-acid (pH 5) conditions. Low pH stress was previously demonstrated to induce the expression of toxR in V. parahaemolyticus (79). In our study, in wild-type cells grown in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 5 (low pH), ompU showed a significant increase in expression of approximately 17-fold (P < 0.01) compared to that of wild-type cells grown in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7 (neutral pH) (Fig. 1). When ΔtoxRS cells were grown at pH 7, the expression ratios of ompU to those of wild-type cells grown under the same condition were −500-fold, a highly significant decrease (P < 0.001). Similarly, when ΔtoxRS cells were grown at pH 5, ompU expression was −160-fold (P < 0.001) compared to that of the wild-type strain grown under the same conditions (Fig. 1). No statistically significant difference in ompU expression was found between growth at pH 7 and that at pH 5 in the ΔtoxRS strain. These results indicate that the deletion of toxRS significantly decreased ompU expression and thus plays a role as a positive regulator of ompU expression.

Fig 1.

Relative expression of ompU in wild-type and ΔtoxRS strains. Wild-type and ΔtoxRS cells were grown for 4 h in either LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7 or LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7 plus 30 min in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 5. Bars represent the relative expression of ompU normalized to 16S rRNA and relative to expression levels found in wild-type V. parahaemolyticus grown for 4 h in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7. RNA was extracted for each condition on two separate occasions, and qPCR was performed in duplicate for each sample. Error bars indicate standard deviations. An unpaired Student's t test was used to compare differences in ompU expression under acid conditions and in the ΔtoxRS strain to expression in wild-type cells grown in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

ΔtoxRS controls the expression of T3SS-1 genes via regulation of leuO.

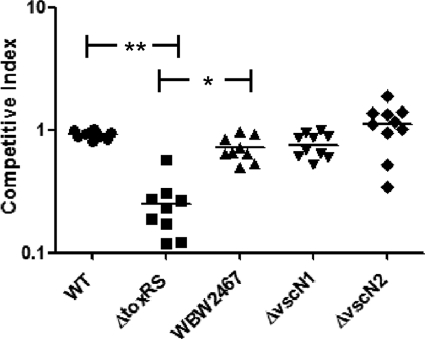

It has previously been demonstrated that the V. parahaemolyticus ΔtoxRS strain is more cytotoxic than the wild-type strain toward Caco-2 cells (79). Similarly, it has been demonstrated that the type III secretion system (T3SS-1) in chromosome I plays a major role in cytotoxicity and virulence in the intraperitoneal mouse model (21). Therefore, we wanted to explore the possibility that T3SS-1 is regulated by the ToxRS system in V. parahaemolyticus. To examine this, we performed quantitative real-time PCR to examine the expression of two genes that encode known T3SS-1 substrates (VopQ and VopD) (8, 62) and two genes that encode T3SS-1 structural components (VP1694 and VP1695) (40) in both wild-type cells and ΔtoxRS cells grown under optimal growth conditions (LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7). Under such conditions, it has been previously demonstrated that wild-type cells do not express T3SS-1 genes (86). We first examined VP1680, which encodes the effector protein VopQ that is secreted via T3SS-1 and plays an important role in cytotoxicity as well as in the host immune response (8, 44, 60, 73). We found an approximately 3-fold increase in VP1680 expression in the ΔtoxRS background compared to that in wild-type cells (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). We then examined VP1656, which encodes a protein, VopD, that shares homology with the type III secreted proteins PopD and YopD of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Yersinia enterocolitica, respectively. PopD and YopD act as translocators that transport effector proteins across the eukaryotic membrane (62). In the ΔtoxRS mutant, the expression of VP1656 was not significantly higher than that in wild-type cells (Fig. 2A). VP1694 and VP1695 encode T3SS structural proteins with similarity to the MxiH T3SS secretion needle protein superfamily and the YscD T3SS inner membrane secretion protein superfamily, respectively (14). In the ΔtoxRS mutant, the expression levels of VP1694 and VP1695 were 2.55- and 2.1-fold higher, respectively, compared to those of wild-type cells (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that genes associated with the T3SS-1 in chromosome I show increased expression in the ΔtoxRS mutant and that ToxRS plays a role in their regulation.

Fig 2.

ToxRS regulates the expression of T3SS-1 genes and leuO (VP0350). (A) The expression levels of two genes encoding T3SS-1 substrates (VP1680 and VP1656) and two genes encoding T3SS structural proteins (VP1694 and VP1695) were examined in the ΔtoxRS and isogenic wild-type strains. An unpaired Student's t test was used to compare differences in gene expression in the ΔtoxRS strain to expression in wild-type cells. *, P < 0.05. (B) The expression of gene VP0350, which encodes a LysR-family transcriptional regulator, was examined in the ΔtoxRS and wild-type strains and was grown under standard conditions as well as ToxR-inducing conditions (pH 5). An unpaired Student's t test was used to compare differences in VP0350 expression under acid conditions and in the ΔtoxRS strain to expression in wild-type cells grown in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. (C) The expression of VP1680, which encodes the T3SS-1 effector protein VopQ, was examined in the ΔtoxRS, ΔVP0350, and WBW0350 strains. An unpaired Student's t test was used to compare differences in VP1680 expression in the ΔtoxRS strain, ΔVP0350, and WBW0350 strains to expression in the wild type. *, P < 0.05. WBW0350 is a ΔtoxRS strain that ectopically expressed VP0350. Bars represent the relative expression of the given gene normalized to the 16S rRNA gene and compared to expression in wild-type cells grown in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7. RNA was extracted for each condition on two separate occasions, and qPCR was run in duplicate for each sample. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Because the ΔtoxRS strain shared a similar phenotype with the recently described VP0350 deletion mutant with regard to cytotoxicity and T3SS-1 expression (19), we hypothesized that ToxRS indirectly regulates T3SS expression via the regulation of the leuO homologue VP0350. To address this, we examined the expression of VP0350 in the ΔtoxRS strain as well as in the isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 2B). We found that in wild-type cells that were subjected to 30 min in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 5, the expression of VP0350 increased 2.8-fold (P < 0.05) compared to that in wild-type cells grown under standard conditions (LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7) (Fig. 2B). However, the expression of VP0350 was significantly decreased (P < 0.001) in the ΔtoxRS strain grown in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 7 compared to that of the isogenic wild-type cells examined under the same conditions (Fig. 2B). Similarly, we found that in ΔtoxRS cells that were subjected to 30 min in LB, 3% NaCl, pH 5, the expression of VP0350 was significantly decreased (P < 0.001) compared to that of wild-type cells examined under the same conditions (Fig. 2B). Additionally, no significant difference in VP0350 expression was observed between the ΔtoxRS strain in neutral and pH 5 conditions. This indicates that the expression of VP0350 does indeed fall under the regulation of the ToxRS system.

Lastly, we hypothesized that the lack of VP0350 expression seen in the ΔtoxRS strain was the cause of the increased expression of the T3SS-1 genes. To examine this, we constructed a VP0350 deletion mutant and also complemented the ΔtoxRS strain with the VP0350 gene cloned into the expression vector pBAD33. As expected, the ΔVP0350 mutant demonstrated an increase in the expression of the T3SS-1 effector gene VP1680 compared to that of the isogenic wild-type strain (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2C). When the ΔtoxRS strain was complemented with the VP0350 gene, the expression of VP1680 was reduced to levels not significantly different from those of the isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results indicate that the increase in T3SS-1 expression seen in the ΔtoxRS strain is due to its regulation of the leuO gene carried by VP0350.

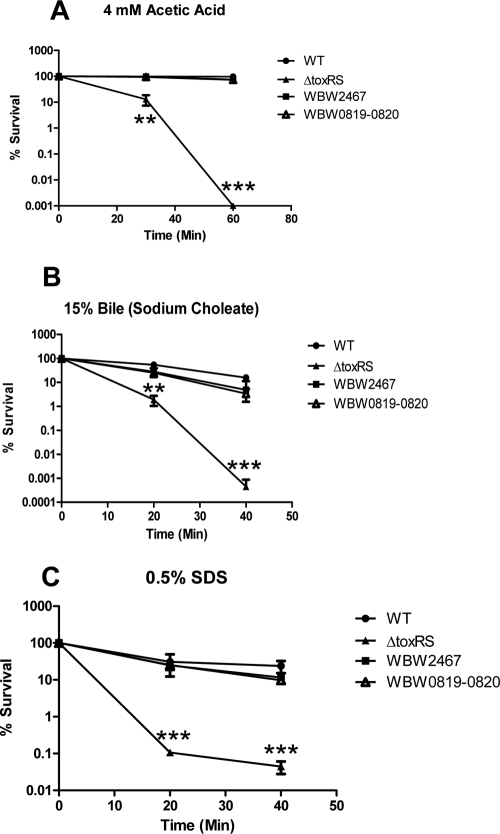

OmpU is important for survival under extracellular stress conditions.

ToxRS has been shown previously to be an important stress response regulator in V. cholerae (43, 47, 48, 67–69). Additionally, we previously demonstrated that the ToxRS system in V. parahaemolyticus plays an important role in the organism's ability to elicit a successful acid tolerance response (79). Provenzano and Klose demonstrated that ToxRS was important for growth in bile salts and SDS (69); however, a mechanism for how ToxRS protects V. parahaemolyticus in the face of these stresses has yet to be determined. Because organic acids as well as bile and other detergents are believed to act on the bacterial cell membrane, we aimed to determine if the regulation of OmpU by ToxRS was the mechanism for stress tolerance. Therefore, we examined the role of ToxRS in the cell stress response to organic acid and anionic detergents, such as bile and SDS. When the ΔtoxRS strain and the wild-type strain were preadapted in 1 mM acetic acid and then subjected to 4 mM acetic acid, there was a significant defect in the survival of the ΔtoxRS strain after 30 min (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). After 60 min, there were no detectable viable ΔtoxRS cells, whereas the wild-type strain exhibited nearly 100% survival throughout the 60 min in acetic acid (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A). However, when ompU was ectopically expressed in the ΔtoxRS background (designated strain WBW2467), the ability to mount a successful adaptive acid tolerance response was restored, and this strain exhibited 97 and 75% survival after 30 and 60 min, respectively (Fig. 3A). The ΔtoxRS strain also exhibited a defect in the ability to survive in the presence of 15% bile, demonstrating 0.1 and 0.04% survival after 20 and 40 min, respectively (Fig. 3B). This was a significantly lower level of survival than that of the isogenic wild-type strain, which exhibited 31% (P < 0.001) and 24% (P < 0.0001) survival during 20 and 40 min in bile, respectively. WBW2467 exhibited no significant differences in survival compared to that of the wild-type strain for both 20 and 40 min in the presence of 15% bile, indicating that ectopically expressing ompU was enough to restore survival in bile to the ΔtoxRS strain. The ΔtoxRS strain phenotype was similar when subjected to 0.5% SDS stress. The ΔtoxRS strain exhibited 2 and 0.0005% survival in 0.5% SDS, which was significantly lower than that of the wild-type strain for both time points (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3C). Similarly, WBW2467 showed no significant difference between itself and the wild-type strain, again indicating that the ectopic expression of ompU was enough to rescue the sensitive phenotype of ΔtoxRS. We also complemented our in-frame ΔtoxRS mutation with a functional copy of toxRS (strain WBW0819-0820) to confirm that it has no polar effects, and as expected under all stress conditions examined, the survival of WBW0819-0820 was not significantly different from that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). These results indicate that ToxRS is an important stress response regulator in V. parahaemolyticus through its regulation of OmpU.

Fig 3.

Effect of organic acid, bile, and SDS stress on the survival of the ΔtoxRS deletion mutant. Wild-type (closed circles), ΔtoxRS (closed triangles), WBW2467 (closed squares), or WBW0819-0820 (open triangles) cells were grown in LB with 3% NaCl and subjected to (A) 60 min of organic (4 mM acetic acid, pH 4.5) stress after preadaptation for 30 min in 1 mM acetic acid adjusted to pH 5.5 (HCl), (B) 40 min in 15% sodium cholate, or (C) 40 min in 0.5% SDS. Survival was determined by dividing the surviving population at various time points by the initial population. All cultures were grown in triplicate, and each experiment was performed at least twice. Error bars indicate standard deviations. P values were calculated using an unpaired Student's t test with a 95% confidence interval. Asterisks denote significant differences between groups. **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001. WT, wild-type V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633; WBW2467, a ΔtoxRS strain that ectopically expressed ompU.

ToxRS is an important mediator of the colonization of the streptomycin-treated adult mouse model.

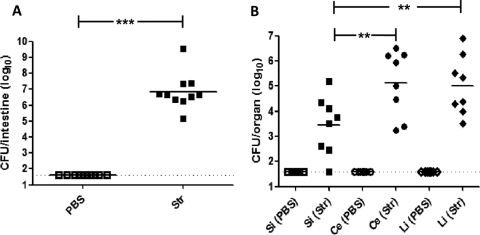

Adult C57BL/6 mice were given an orogastric dose of either PBS or streptomycin (20 mg/animal) 24 h prior to orogastric inoculation with V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633. Two days postinfection, total intestinal tissues were isolated and assessed for weight and bacterial content. The average intestinal weights in V. parahaemolyticus-infected animals pretreated with streptomycin were significantly higher than those from the control V. parahaemolyticus-infected mice pretreated with PBS (P < 0.05) (data not shown). Importantly, when these intestinal samples were examined to determine bacterial burdens, tissues from animals pretreated with PBS did not contain detectable levels of V. parahaemolyticus, while those pretreated with streptomycin contained significantly higher V. parahaemolyticus bacterial loads (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4A). These results demonstrate that the administration of a single antibiotic treatment to mice prior to orogastric challenge with V. parahaemolyticus allows for successful colonization. Having observed that V. parahaemolyticus persists in the murine intestine after orogastric challenge only after streptomycin administration, we next assessed whether the organism was distributed equally throughout the gastrointestinal tract or if it preferentially localized to discrete segments of the intestine. Mice given an orogastric dose of either PBS or streptomycin were subsequently infected with V. parahaemolyticus. Two days postinfection, the intestinal tissues were removed and fecal contents cleared, with the small intestine, cecae, and large intestine independently homogenized and plated to determine the tissue-associated bacterial burdens (Fig. 4B). As we observed initially, V. parahaemolyticus was not detected in tissues from animals pretreated with PBS prior to infection (Fig. 4B), while mice given an orogastric dose of streptomycin were found to have V. parahaemolyticus in all of the intestinal segments tested (Fig. 4B). Within an individual animal, the levels of V. parahaemolyticus were typically more than 1-log lower in the small intestine compared to those found in either the cecum or large intestine (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). We also examined both the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes from both PBS- and streptomycin-treated infected mice and recovered no V. parahaemolyticus CFU from either.

Fig 4.

Successful colonization of the murine gastrointestinal tract by V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 requires antibiotic pretreatment. (A) C57BL/6 mice were orally dosed with PBS (open squares) or streptomycin (Str; 20 mg/animal; filled squares) 1 day prior to oral infection with V. parahaemolyticus. At 48 h postinfection, the entire gastrointestinal tracts (small intestine to the descending colon) were isolated from infected animals. The entire gastrointestinal tracts then were homogenized in PBS and plated on LB agar containing 3% NaCl and 200 μg/ml streptomycin. (B) Tissues of the GI tract were also separated into the small intestine (filled squares), cecum (filled circles), and large intestine (filled diamonds), gently flushed of fecal content, and homogenized in PBS. Samples were serially diluted and plated on LB agar containing 3% NaCl and 200 μg/ml streptomycin to determine the numbers of tissue-associated V. parahaemolyticus cells. Data are pooled results from two separate experiments (n = 10 for each treatment). In both panels the solid line indicates the means and the dashed line indicates the limit of detection. P values were calculated using an unpaired Student's t test with a 95% confidence interval. Asterisks denote significant differences between groups for data under the bracket. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001. Si, small intestine; Ce, cecum; Li, large intestine.

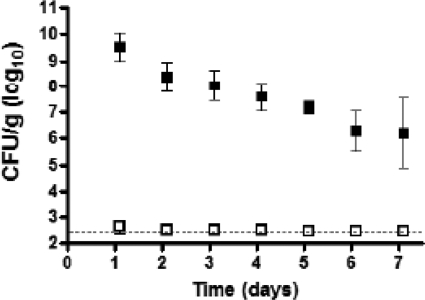

The persistence of intestinal colonization with V. parahaemolyticus was examined by measuring the bacterial loads in fecal samples from infected animals. Animals pretreated with either PBS or streptomycin were infected with V. parahaemolyticus, and fresh fecal pellets were collected at daily intervals and plated to determine V. parahaemolyticus CFU in the fecal content. High levels of V. parahaemolyticus were observed only in those samples collected from mice that were treated with streptomycin prior to infection compared to mice treated only with PBS. The bacterial numbers decreased slowly over time but remained above 106/g in all streptomycin-treated animals for 7 days (Fig. 5). Colonized mice displayed no overt signs of morbidity during the course of infection. We next examined whether or not variation in the inoculum dose affects the establishment of colonization. To accomplish this, we examined mice pretreated with streptomycin in groups (3 to 5 mice/group) given a range of doses orogastrically (1.5 × 109, 5 × 108, 1.5 × 108, and 1.7 × 107 CFU). Fecal pellets were collected 24 and 72 h postinfection, and V. parahaemolyticus CFU counts were determined. All mice were colonized to the same extent for all doses examined (data not shown).

Fig 5.

Oral infection of mice with wild-type V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 results in prolonged intestinal colonization and shedding in feces. Groups of C57BL/6 mice were orally dosed with PBS (open squares) (n = 5/group) or streptomycin (filled squares) (n = 6/group) 1 day prior to oral infection with V. parahaemolyticus. At the indicated intervals postinfection, fecal pellets were collected from mice, weighed, and homogenized in PBS. Samples were serially diluted and plated on LB agar containing 3% NaCl and 200 μg/ml streptomycin to determine the number of V. parahaemolyticus cells per gram of fecal material. The dotted line indicates the limit of detection for the assay. Error bars indicate ± standard deviations.

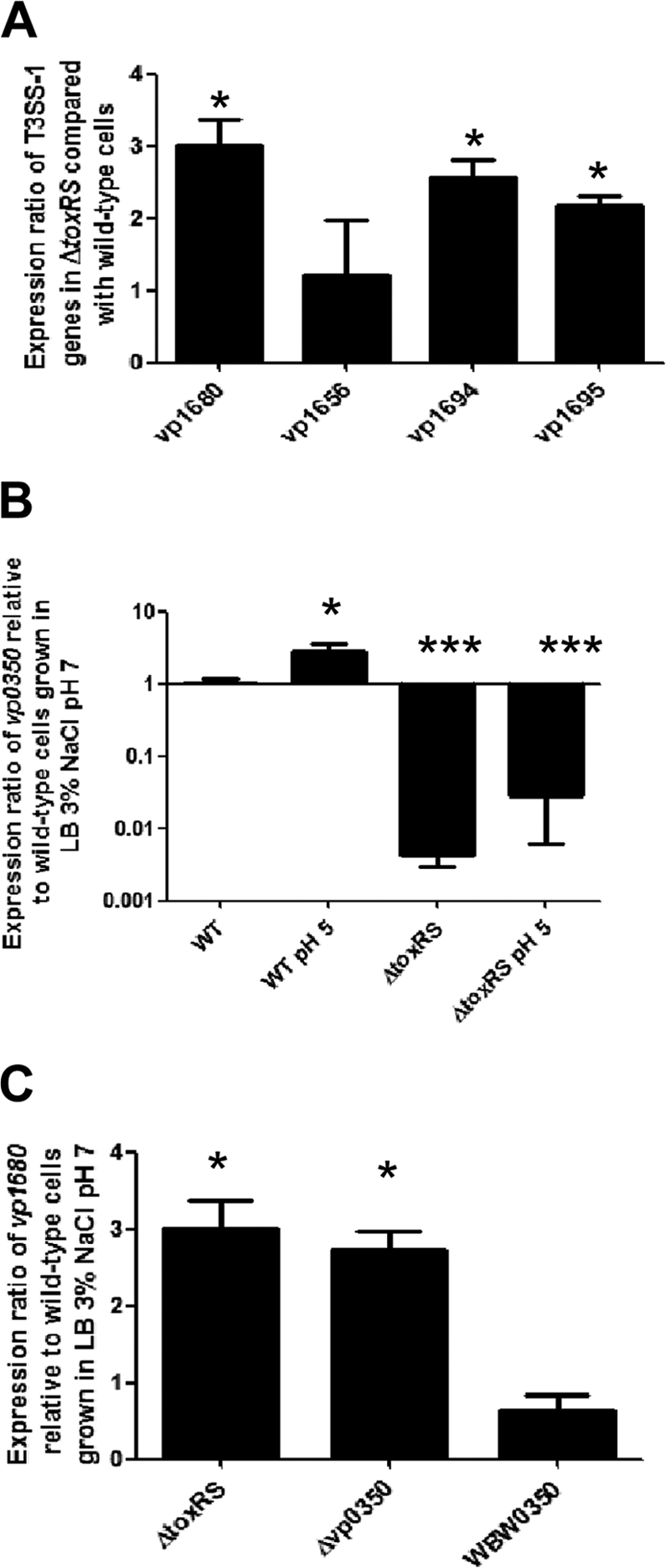

To directly assess the importance of the ToxRS system in the colonization of the host and to increase the utility of our colonization model, we developed a competition assay by creating a β-galactosidase-positive wild-type strain of V. parahaemolyticus, named WBWlacZ. To confirm that WBWlacZ grows similarly to the wild type, we compared growth rates in LB, 3% NaCl at 37°C overnight and found no difference in growth rates between the two strains (data not shown). In addition, we performed in vitro competition assays, including growth overnight in LB, 3% NaCl at 37°C of mixed cultures of WBWlacZ and the test strains, and we found no difference in the CFU counts between the strains examined (data not shown). By using the streptomycin mouse model and a mixed culture of the WBWlacZ and ΔtoxRS strains, we can directly measure CFU using a blue/white screen in vivo. Equal volumes of WBWlacZ and the test strains were inoculated into streptomycin-treated adult mice. After 24 h postinfection, the entire gastrointestinal tract of each mouse was removed, homogenized, and plated for CFU to assay for the presence of both strains. We first compared WBWlacZ and the wild-type strains in coculture in vivo to confirm that they behave similarly and found no difference in the competitive index between the two strains. We next examined a coculture of WBWlacZ and ΔtoxRS and determined that after 24 h postinfection the ΔtoxRS strain is significantly (P < 0.001) outcompeted (4-fold) by the WBWlacZ strain (mean competitive index of 0.25 ± 0.13) (Fig. 6). These results indicate that ToxRS is important for colonization, probably as a positive regulator of the stress response for the in vivo survival of V. parahaemolyticus. We also examined the fitness of ΔvscN1 (T3SS-1 mutant) and ΔvscN2 (T3SS-2 mutant) versus WBWlacZ in our colonization model. Both secretion systems are well-characterized virulence factors; however, their role in colonization has thus far not been determined. Using the streptomycin-treated adult mouse model and the WBWlacZ strain, we found no significant difference in the competitive index for either of the T3SS mutants compared to that of the isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

V. parahaemolyticus ToxRS system is important for colonization of the adult mouse. A 1:1 mixed culture (1 × 109 CFU total) of WBWlacZ and a test strain were used to orogastrically infect streptomycin-treated adult mice. At 24 h postinfection, the entire gastrointestinal tracts were harvested, homogenized in PBS, and plated for CFU counting on LB plates containing 3% NaCl, streptomycin, and X-Gal. Data are reported as competitive index (CI), which is calculated as CI = ratio out(test strain/WBWlacZ)/ratio in(test strain/WBWlacZ). The solid line indicates the means. P values were calculated using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA followed a Dunn's multiple-comparisons posttest. Asterisks denote significant differences between groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001. WBW2467, ΔtoxRS strain ectopically expressing ompU (VP2467); ΔvscN1, T3SS-1 null mutant; ΔvscN2, T3SS-2 null mutant.

To assess whether or not the defect in the ΔtoxRS mutant colonization in the streptomycin-treated adult mouse model is due to ompU, we performed a competition assay examining the ΔtoxRS mutant complement with ompU (WBW2467) compared to the wild type (Fig. 6). We found that WBW2467 had a competitive index of 0.72 ± 0.18, which, while significantly higher than that of the ΔtoxRS mutant (P < 0.05), was not significantly different from that of the isogenic wild-type strain. These results indicate that the deficiency in colonization exhibited by the ΔtoxRS strain can be alleviated by ectopically expressing the ompU gene.

DISCUSSION

The consumption of V. parahaemolyticus-contaminated seafood is the leading cause of seafood-associated bacterial gastroenteritis in the United States and Asia (5, 12, 13, 46). To date, relatively little is known about the bacterial mechanisms responsible for colonization following its entry into the human host. In an effort to begin investigating genes necessary for the colonization, survival, and proliferation of V. parahaemolyticus within the gastrointestinal tract, we examined the global regulator ToxRS. Similarly to what has previously been shown for V. cholerae, our ΔtoxRS mutant is sensitive to a number of stress conditions that the bacterium encounters in vivo, such as acid and bile salt stresses. Our data suggest that the defect in stress tolerance is due to the ToxRS regulation of ompU, which encodes a major outer membrane protein found in a wide range of enteric bacteria.

In V. cholerae, the ToxRS regulon is essential for virulence and has previously been shown to control the expression of a cascade of genes involved in bacterial pathogenesis (cholera toxin and toxin coregulated pilus), along with several outer membrane proteins (OmpU and OmpT), which enhance the resistance of the organism to antimicrobial compounds in the intestine (reviewed in references 10, 15, and 63). Our results show that a V. parahaemolyticus mutant of ToxRS does not colonize the mouse intestine as well as the wild type does. The role of ToxRS in the pathogenesis of V. parahaemolyticus has not been defined, even though there is evidence that it controls the expression of outer membrane proteins and bacterial resistance to membrane disruption by intestinal detergents (bile salts) (67). In the V. parahaemolyticus ΔtoxRS mutant, we observed a 500-fold decrease in the expression of ompU (VP2467) relative to that of the wild type by quantitative real-time PCR analysis (Fig. 1). We previously showed that under acidic conditions V. parahaemolyticus expression of toxRS is induced, and in the absence of ToxRS the organism has a significantly reduced ability to survive at low pH (79). In this study, we have demonstrated that the ΔtoxRS strain was also deficient in survival in high concentrations of bile and SDS. These defects, along with the defect in organic acid survival, were shown to be due to this strain's inability to express the ompU gene, which would implicate OmpU as playing an important role in protection from extracellular stresses. Interestingly, following the coinfection of streptomycin-treated animals with both the V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 ΔtoxRS and WBWlacZ strains, we observed a significant (P < 0.001) reduction in the ability of the ΔtoxRS mutant to colonize the intestine. Thus, in addition to demonstrating that ToxRS and OmpU are important stress response systems, our results show that both proteins are important for colonization as well.

We have also previously shown that the ΔtoxRS strain exhibits increased cytotoxicity in vitro (79). In an effort to further characterize this phenotype, we have demonstrated in this study that the V. parahaemolyticus ToxRS system is a negative regulator of the type III secretion system found in chromosome I. This regulation is indirect and is mediated by the LeuO transcription factor homologue encoded by VP0350. ToxRS is a positive regulator of leuO expression, and LeuO is a negative regulator of T3SS-1 gene expression. This ToxRS pathway is unique to any Vibrio species thus far described. Previously, Call and colleagues demonstrated that the genes VP1699, VP1698, and VP1701 are homologues of Pseudomonas genes exsA, exsD and exsC, are found at the terminus of the T3SS-1 cluster, and are regulators of T3SS-1 genes (84, 86). They showed that the environmental regulation of T3SS-1 genes is through ExsA, which acts as a positive transcriptional regulator of the T3SS-1 gene cluster. Call et al. found that under T3SS-1 noninducing conditions (growth in LB, NaCl), ExsD binds to ExsA and prevents the transcriptional activity of this protein. However, under inducing conditions (cell culture media), ExsC is expressed and binds to ExsD. This prevents ExsD from binding ExsA and thus allows for the transcription of the T3SS-1 genes (84). Kodama and colleagues also demonstrated the regulation of T3SS-1 genes by ExsA and proposed that H-NS is a negative regulator of exsA (35). To add to this regulatory pathway, we have demonstrated that ToxRS and LeuO act as upstream regulators of T3SS-1 expression.

The streptomycin treatment of animals prior to their orogastric infection resulted in the recovery of substantial numbers of V. parahaemolyticus from gastrointestinal tissues 2 days postinfection and high levels of fecal shedding starting day 1 postinfection, whereas no V. parahaemolyticus was detectable in the tissues or stools from similarly infected PBS-treated animals. Vibrio parahaemolyticus was typically found throughout the gastrointestinal tracts of treated mice; however, higher bacterial burdens were observed in the cecum and large intestines. Following the establishment of colonization, the organism was maintained within intestinal tissues, as fecal pellets shed by infected animals contained high levels of V. parahaemolyticus for greater than 1 week postinfection. Interestingly, our histological assessment of tissues of the large intestine 7 days postinfection indicated that there were no overt signs of pathology, such as the disruption of colonic crypt structure or epithelial or brush border degradation (data not shown).

The use of murine models to assess V. parahaemolyticus pathogenesis has been frequently reported in the literature (3, 21, 22, 26, 51, 78, 81–83). Several of these studies utilized intraperitoneal inoculation for bacterial delivery, an infectious route that mimics septicemic infection, to determine and compare the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of strains. In some cases, the LD50 of strains following the orogastric inoculation of untreated animals was determined (3, 22, 78). However, our initial attempts to reproduce these orogastric challenge experiments for the characterization of mutant strains of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 failed to elicit mortality or observable morbidity in animals at any time postinfection. The examination of several parameters, including the use of either inbred (C57BL/6 and BALB/c) or outbred (CD-1) animals as well as infant mice, the type of bacterial growth media (LB versus brain heart infusion broth), or the growth phase of the inoculum (log-phase versus stationary-phase cultures), still did not result in the productive infection of animals (data not shown). Interestingly, a recent study by Call's group suggests that previously reported orogastric rabbit and mouse models that produced septicemia are inadvertent pulmonary models (65). This study also described two novel animal models, an orogastric piglet model and an intrapulmonary inoculated mouse model, to examine the role of the two T3SSs in V. parahaemolyticus pathogenesis (65), and although useful models, neither addresses the most common route of infection. To our knowledge, the colonization model system we report here is the first allowing for the carriage of V. parahaemolyticus in the gastrointestinal tract of adult mice after oral inoculation.

Conventionally reared mice are resistant to gastrointestinal infection following oral challenge with a number of enteric pathogens, and therefore the pretreatment of animals with antibiotics to initiate the development of a productive infection has frequently been utilized to overcome the inability to infect adult animals (18, 70, 72, 77). The orogastric administration of streptomycin to mice has been shown to alter many of the normal physiological parameters of the intestine, rapidly resulting in shifts in the microbial flora, luminal pH, and the types of short-chain volatile fatty acids present, which, in combination, presumably play a role in removing barriers that might prohibit pathogen colonization (18, 70, 72, 77). For example, the antibiotic pretreatment of mice has been shown to result in a rapid increase in cecal weights owing to fluid accumulation, with an obvious enlargement of tissue upon gross morphological examination (4, 71). Two separate studies have recently described models in which adult mice were orogastrically infected by V. cholerae, resulting in productive infections with intestinal colonization lasting for several days (55, 57–59). In these studies, the method by which mice were infected differs substantially from the protocol described here, with one requiring the use of ketamine/xylazine and the other isoflurane (55, 57–59). In the system described here, anesthesia was not utilized.

In summary, our aim was to characterize the ToxRS system in V. parahaemolyticus and to develop a murine model allowing for the colonization of adult mice following orogastric infection with V. parahaemolyticus, which is the typical route for bacterial entry into the host. We demonstrated that ToxRS is an important regulator of the stress response protein OmpU, and that this regulation is important for survival in a number of stress conditions commonly encountered in the human host. We have demonstrated that the ToxRS system also plays a role in the regulation of the T3SS-1 through its regulation of VP0350, a transcription regulator homologous to LeuO. This branch of the ToxRS regulon is thus far unique to V. parahaemolyticus. To our knowledge, the orogastric murine model presented in this study is the first for this particular species of Vibrio, and it provides a valuable new tool for studies to begin dissecting both the bacterial and host parameters that are crucial for the bacterial colonization of the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, we have generated a β-galactosidase-expressing strain of V. parahaemolyticus, which for the first time will allow the coinfection of animal models to directly compare the effects of gene deletion in vivo. Through the use of this model, we have demonstrated that V. parahaemolyticus ToxRS and OmpU are important mediators of colonization. In summary, our data show a practical application for this new streptomycin-treated murine model for orogastric colonization by V. parahaemolyticus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by funding from the United States Department of Agriculture, NRI CSREES grant 2008-35201-04535.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 March 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Akeda Y, Nagayama K, Yamamoto K, Honda T. 1997. Invasive phenotype of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Infect. Dis. 176:822–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akeda Y, et al. 2009. Identification and characterization of a type III secretion-associated chaperone in the type III secretion system 1 of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 296:18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baffone W, et al. 2003. Retention of virulence in viable but non-culturable halophilic Vibrio spp. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 89:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barthel M, et al. 2003. Pretreatment of mice with streptomycin provides a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis model that allows analysis of both pathogen and host. Infect. Immun. 71:2839–2858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blackstone GM, et al. 2003. Detection of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in oyster enrichments by real time PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 53:149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boyd EF, et al. 2008. Molecular analysis of the emergence of pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus. BMC Microbiol. 8:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Broberg CA, Zhang L, Gonzalez H, Laskowski-Arce MA, Orth K. 2010. A Vibrio effector protein is an inositol phosphatase and disrupts host cell membrane integrity. Science 329:1660–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burdette DL, Seemann J, Orth K. 2009. Vibrio VopQ induces PI3-kinase-independent autophagy and antagonizes phagocytosis. Mol. Microbiol. 73:639–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burdette DL, Yarbrough ML, Orth K. 2009. Not without cause: Vibrio parahaemolyticus induces acute autophagy and cell death. Autophagy 5:100–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Childers BM, Klose KE. 2007. Regulation of virulence in Vibrio cholerae: the ToxR regulon. Future Microbiol. 2:335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daniels NA, et al. 2000. Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in the United States, 1973–1998. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1661–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DePaola A, Nordstrom JL, Bowers JC, Wells JG, Cook DW. 2003. Seasonal abundance of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Alabama oysters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1521–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DePaola A, et al. 2003. Molecular, serological, and virulence characteristics of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from environmental, food, and clinical sources in North America and Asia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3999–4005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diepold A, et al. 2010. Deciphering the assembly of the Yersinia type III secretion injectisome. EMBO J. 29:1928–1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DiRita VJ, et al. 2000. Virulence gene regulation inside and outside. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355:657–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duperthuy M, et al. 2010. The major outer membrane protein OmpU of Vibrio splendidus contributes to host antimicrobial peptide resistance and is required for virulence in the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Environ. Microbiol. 12:951–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duperthuy M, et al. 2011. Use of OmpU porins for attachment and invasion of Crassostrea gigas immune cells by the oyster pathogen Vibrio splendidus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2993–2998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garner CD, et al. 2009. Perturbation of the small intestine microbial ecology by streptomycin alters pathology in a Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium murine model of infection. Infect. Immun. 77:2691–2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gode-Potratz CJ, Chodur DM, McCarter LL. 2010. Calcium and iron regulate swarming and type III secretion in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 192:6025–6038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hiyoshi H, Kodama T, Iida T, Honda T. 2010. Contribution of Vibrio parahaemolyticus virulence factors to cytotoxicity, enterotoxicity, and lethality in mice. Infect. Immun. 78:1772–1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoashi K, et al. 1990. Pathogenesis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: intraperitoneal and orogastric challenge experiments in mice. Microbiol. Immunol. 34:355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Honda T, Iida T. 1993. The pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and the role of the thermostable direct heamolysin and related heamolysins. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 4:106–113 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Honda T, Ni Y, Miwatani T, Adachi T, Kim J. 1992. The thermostable direct hemolysin of Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a pore-forming toxin. Can. J. Microbiol. 38:1175–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Honda T, Ni YX, Miwatani T. 1988. Purification and characterization of a hemolysin produced by a clinical isolate of Kanagawa phenomenon-negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related to the thermostable direct hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 56:961–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Honda T, et al. 1976. Identification of lethal toxin with the thermostable direct hemolysin produced by Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and some physicochemical properties of the purified toxin. Infect. Immun. 13:133–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hondo S, et al. 1987. Gastroenteritis due to Kanagawa negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Lancet i:331–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hurley CC, Quirke A, Reen FJ, Boyd EF. 2006. Four genomic islands that mark post-1995 pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates. BMC Genomics 7:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Izutsu K, et al. 2008. Comparative genomic analysis using microarray demonstrates a strong correlation between the presence of the 80-kilobase pathogenicity island and pathogenicity in Kanagawa phenomenon-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains. Infect. Immun. 76:1016–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Joseph SW, Colwell RR, Kaper JB. 1982. Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related halophilic vibrios. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 10:77–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaneko T, Colwell RR. 1973. Ecology of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Chesapeake Bay. J. Bacteriol. 113:24–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kodama T, et al. 2010. Two regulators of Vibrio parahaemolyticus play important roles in enterotoxicity by controlling the expression of genes in the Vp-PAI region. PLoS One 5:e8678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kodama T, et al. 2007. Identification and characterization of VopT, a novel ADP-ribosyltransferase effector protein secreted via the Vibrio parahaemolyticus type III secretion system 2. Cell Microbiol. 9:2598–2609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kodama T, et al. 2010. Transcription of Vibrio parahaemolyticus T3SS1 genes is regulated by a dual regulation system consisting of the ExsACDE regulatory cascade and H-NS. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 311:10–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Laskowski-Arce MA, Orth K. 2008. Acanthamoeba castellanii promotes the survival of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7183–7188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li CC, Crawford JA, DiRita VJ, Kaper JB. 2000. Molecular cloning and transcriptional regulation of ompT, a ToxR-repressed gene in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 35:189–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin Z, Kumagai K, Baba K, Mekalanos JJ, Nishibuchi M. 1993. Vibrio parahaemolyticus has a homolog of the Vibrio cholerae toxRS operon that mediates environmentally induced regulation of the thermostable direct hemolysin gene. J. Bacteriol. 175:3844–3855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liverman AD, et al. 2007. Arp2/3-independent assembly of actin by Vibrio type III effector VopL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:17117–17122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Makino K, et al. 2003. Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V. cholerae. Lancet 361:743–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martinez-Urtaza J, et al. 2004. Characterization of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus Isolates from clinical sources in Spain and comparison with Asian and North American pandemic isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4672–4678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mathur J, Davis BM, Waldor MK. 2007. Antimicrobial peptides activate the Vibrio cholerae sigmaE regulon through an OmpU-dependent signalling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 63:848–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mathur J, Waldor MK. 2004. The Vibrio cholerae ToxR-regulated porin OmpU confers resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 72:3577–3583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Matlawska-Wasowska K, et al. 2010. The Vibrio parahaemolyticus type III secretion systems manipulate host cell MAPK for critical steps in pathogenesis. BMC Microbiol. 10:329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Matsuda S, et al. 2010. Association of Vibrio parahaemolyticus thermostable direct hemolysin with lipid rafts is essential for cytotoxicity but not hemolytic activity. Infect. Immun. 78:603–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McLaughlin JB, et al. 2005. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus gastroenteritis associated with Alaskan oysters. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:1463–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Merrell DS, Bailey C, Kaper JB, Camilli A. 2001. The ToxR-mediated organic acid tolerance response of Vibrio cholerae requires OmpU. J. Bacteriol. 183:2746–2754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Merrell DS, Camilli A. 1999. The cadA gene of Vibrio cholerae is induced during infection and plays a role in acid tolerance. Mol. Microbiol. 34:836–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Miller VL, Mekalanos JJ. 1984. Synthesis of cholera toxin is positively regulated at the transcriptional level by ToxR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81:3471–3475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miller VL, Taylor RK, Mekalanos JJ. 1987. Cholera toxin transcriptional activator ToxR is a transmembrane DNA binding protein. Cell 48:271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nagayama K, Yamamoto K, Mitawani T, Honda T. 1995. Characterisation of a haemolysin related to Vp-TDH produced by a Kanagawa phenomenon-negative clinical isolate of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Med. Microbiol. 42:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nair G, et al. 2007. Global dissemination of Vibrio parahaemolyticus serotype O3:K6 and its serovariants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20:39–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nishibuchi M, et al. 1989. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene (trh) encoding the hemolysin related to the thermostable direct hemolysin of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Infect. Immun. 57:2691–2697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nordstrom JL, DePaola A. 2003. Improved recovery of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus from oysters using colony hybridization following enrichment. J. Microbiol. Methods 52:273–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nygren E, Li BL, Holmgren J, Attridge SR. 2009. Establishment of an adult mouse model for direct evaluation of the efficacy of vaccines against Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 77:3475–3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Okada N, et al. 2009. Identification and characterization of a novel type III secretion system in trh-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus strain TH3996 reveal genetic lineage and diversity of pathogenic machinery beyond the species level. Infect. Immun. 77:904–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Olivier V, Haines GK, III, Tan Y, Satchell KJ. 2007. Hemolysin and the multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin are virulence factors during intestinal infection of mice with Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 strains. Infect. Immun. 75:5035–5042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Olivier V, Queen J, Satchell KJ. 2009. Successful small intestine colonization of adult mice by Vibrio cholerae requires ketamine anesthesia and accessory toxins. PLoS One 4:e7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Olivier V, Salzman NH, Satchell KJ. 2007. Prolonged colonization of mice by Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 depends on accessory toxins. Infect. Immun. 75:5043–5051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ono T, Park KS, Ueta M, Iida T, Honda T. 2006. Identification of proteins secreted via Vibrio parahaemolyticus type III secretion system 1. Infect. Immun. 74:1032–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Park KS, et al. 2004. Cytotoxicity and enterotoxicity of the thermostable direct hemolysin-deletion mutants of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Microbiol. Immunol. 48:313–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Park KS, et al. 2004. Functional characterization of two type III secretion systems of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Infect. Immun. 72:6659–6665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peterson KM. 2002. Expression of Vibrio cholerae virulence genes in response to environmental signals. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 3:29–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Philippe N, Alcaraz JP, Coursange E, Geiselmann J, Schneider D. 2004. Improvement of pCVD442, a suicide plasmid for gene allele exchange in bacteria. Plasmid 51:246–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pineyro P, et al. 2010. Development of two animal models to study the function of Vibrio parahaemolyticus type III secretion systems. Infect. Immun. 78:4551–4559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Prouty MG, Osorio CR, Klose KE. 2005. Characterization of functional domains of the Vibrio cholerae virulence regulator ToxT. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1143–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Provenzano D, Klose KE. 2000. Altered expression of the ToxR-regulated porins OmpU and OmpT diminishes Vibrio cholerae bile resistance, virulence factor expression, and intestinal colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10220–10224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Provenzano D, Lauriano CM, Klose KE. 2001. Characterization of the role of the ToxR-modulated outer membrane porins OmpU and OmpT in Vibrio cholerae virulence. J. Bacteriol. 183:3652–3662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Provenzano D, Schuhmacher DA, Barker JL, Klose KE. 2000. The virulence regulatory protein ToxR mediates enhanced bile resistance in Vibrio cholerae and other pathogenic Vibrio species. Infect. Immun. 68:1491–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Que JU, Casey SW, Hentges DJ. 1986. Factors responsible for increased susceptibility of mice to intestinal colonization after treatment with streptomycin. Infect. Immun. 53:116–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Savage DC, Dubos R. 1968. Alterations in the mouse cecum and its flora produced by antibacterial drugs. J. Exp. Med. 128:97–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sekirov I, et al. 2008. Antibiotic-induced perturbations of the intestinal microbiota alter host susceptibility to enteric infection. Infect. Immun. 76:4726–4736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Shimohata T, et al. 2011. Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection induces modulation of IL-8 secretion through dual pathway via VP1680 in Caco-2 cells. J. Infect. Dis. 203:537–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Takahashi A, Kenjyo N, Imura K, Myonsun Y, Honda T. 2000. Cl(-) secretion in colonic epithelial cells induced by the Vibrio parahaemolyticus hemolytic toxin related to thermostable direct hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 68:5435–5438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Taylor RK, Miller VL, Furlong DB, Mekalanos JJ. 1987. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84:2833–2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Trosky JE, et al. 2004. Inhibition of MAPK signaling pathways by VopA from Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51953–51957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Valdez Y, et al. 2009. Nramp1 drives an accelerated inflammatory response during Salmonella-induced colitis in mice. Cell. Microbiol. 11:351–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Vongxay K, et al. 2008. Pathogenic characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates from clinical and seafood sources. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126:71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Whitaker WB, et al. 2010. Modulation of responses of Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 to pH and temperature stresses by growth at different salt concentrations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4720–4729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Williams TL, Musser SM, Nordstrom JL, DePaola A, Monday SR. 2004. Identification of a protein biomarker unique to the pandemic O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1657–1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wong H, et al. 2005. Characterization of new O3:K6 strains and phylogenetically related strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated in Taiwan and other countries. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98:572–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wong HC, Lee YS. 1995. Effect of iron on the recovery of viable bacteria from the cardiac blood in an experimental mouse model and on the serum resistance and macrophage phagocytosis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 13:219–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wong HC, Peng PY, Han JM, Chang CY, Lan SL. 1998. Effect of mild acid treatment on the survival, enteropathogenicity, and protein production in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Infect. Immun. 66:3066–3071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhou X, Konkel ME, Call DR. 2010. Regulation of type III secretion system 1 gene expression in Vibrio parahaemolyticus is dependent on interactions between ExsA, ExsC, and ExsD. Virulence 1:260–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zhou X, Konkel ME, Call DR. 2009. Type III secretion system 1 of Vibrio parahaemolyticus induces oncosis in both epithelial and monocytic cell lines. Microbiology 155:837–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zhou X, Shah DH, Konkel ME, Call DR. 2008. Type III secretion system 1 genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus are positively regulated by ExsA and negatively regulated by ExsD. Mol. Microbiol. 69:747–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zimmerman AM, et al. 2007. Variability of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus densities in Northwest Gulf of Mexico water and oysters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7589–7596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]