Abstract

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), a prototypic heritable disorder with ectopic mineralization, manifests with characteristic skin findings, ocular involvement and cardiovascular problems, with considerable morbidity and mortality. The classic forms of PXE are due to loss-of-function mutations in the ABCC6 gene, which encodes ABCC6, a transmembrane efflux transporter expressed primarily in the liver. Several lines of evidence suggest that PXE is a primary metabolic disorder which, in the absence of ABCC6 transporter activity, displays reduced plasma anti-mineralization capacity due to reduced fetuin-A and matrix gla-protein (MGP) levels. MGP requires to be activated by γ-glutamyl carboxylation, a vitamin K-dependent reaction, to serve in anti-mineralization role in the peripheral connective tissue cells. While the molecules transported from the hepatocytes to circulation by ABCC6 in vivo remain unidentified, it has been hypothesized that a critical vitamin K derivative, such as reduced vitamin K conjugated with glutathione, is secreted to circulation physiologically, but not in the absence of ABCC6 transporter activity. As a result, activation of MGP by γ-glutamyl carboxylase is diminished, allowing slow, yet progressive, mineralization of connective tissues characteristic of PXE. Understanding of the pathomechanistic details of PXE provides a basis for development of targeted molecular therapies for this, currently intractable, disease.

Keywords: Heritable skin diseases, animal models, ectopic mineralization, ABC transporters, elastic structures

PXE – THE DIAGNOSTIC CHALLENGE

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), a multi-system heritable disorder characterized by ectopic mineralization of soft connective tissues, can pose a diagnostic challenge to practitioners, for several reasons (Neldner, 1988). From the historical perspective, the original descriptions of cutaneous manifestations in PXE, in association with elastic degeneration of the skin and heart, were given by French dermatologists under the general diagnosis of “xanthelasma” (Balzer, 1884; Chauffard, 1889). Subsequently, after extensive re-examination of the previously published cases, Darier, in 1896, proposed the name “pseudo-xanthome elastiqué” to differentiate this condition from xanthomas, hence “pseudoxanthoma” (Darier, 1896). In the late 1920's, Grönblad and Strandberg, an ophthalmologist and a dermatologist, both from Sweden, recognized the association of the characteristic skin manifestation with angioid streaks, thus establishing the eponym Grönblad-Strandberg Syndrome (Grönblad, 1929; Strandberg, 1929). The cardiovascular manifestations of PXE were not fully appreciated until some two decades later (Carlborg, 1944). More recently, identification of the gene defects underlying PXE has helped to clarify the clinical constellations and molecular genetics of this disorder (Chassaing et al., 2005; Miksch et al., 2005; Li et al., 2009a).

PXE is an autosomal recessive disorder, but its precise prevalence is currently unknown. The estimates vary widely, but those in the range of 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 70,000 may be representative of the actual incidence. PXE is encountered in all ancestral backgrounds without racial predilection. In some areas (such as South Africa) the prevalence may be higher due to consanguinity and/or the presence of a founder effect (Le Saux et al., 2002; Ramsey et al., 2009). There appears to be a slight female preponderance, but the reasons for this phenomenon in an autosomal recessive disease with apparently full penetrance are not clear. Furthermore, adding to the diagnostic difficulty is that the clinical findings of PXE are rarely present at birth and the skin findings usually become recognizable not until during the second or third decade of life (Neldner, 1988; Pfendner et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009a; Naorui et al., 2009). In many cases, the accurate diagnosis is not made until serious ocular or vascular complications develop in the third or fourth decade of life.

PHENOTYPIC SPECTRUM OF PXE

PXE is characterized by dystrophic mineralization of soft connective tissues in a number of organs, but the primary clinical manifestations in classic PXE center on three major organ systems, viz., the skin, the eyes, and the cardiovascular system (Neldner, 1988).

Skin Manifestations

The primary cutaneous lesions are small, discrete yellowish papules that appear initially in the flexural areas, including lateral neck, antecubital and popiliteal fossae. These primary lesions progressively coalesce into larger plaques of inelastic and leathery skin which progressively extends to involve non-flexural sites as well. In the most extensive cases, essentially all skin can be involved with loss of elasticity and recoil. Mucosal membranes, particularly the inner lower lip, can become involved in a similar manner with yellow papules. The cutaneous findings present primarily a cosmetic problem and do not interfere with normal life activities. However, the presence of characteristic skin lesions signifies the risk for development of ocular and vascular complications that can be quite debilitating with considerable morbidity and even mortality.

Eye Findings

The characteristic ophthalmologic finding in the majority of patients with PXE is angioid streaks, and after the age of 30 their prevalence approaches 100 percent (Neldner, 1988). While angioid streaks may be detected in some cases as early as in the first decade of life, they frequently become symptomatic later in life, particularly after trauma to the eye. Angioid streaks derive from breaks upon aberrant mineralization of the elastic lamina of Bruch's membrane which separates the pigmented layer of the retina from the choroid of the eye. These fractures can lead to neovascularization from choriocapillaries, and subsequent leakage of newly formed vessels leads to hemorrhage and scarring (Georgalas et al., 2009). Ultimately, these pathologic changes cause progressive loss of visual acuity and, relatively rarely, in central blindness. It should be noted, however, that angioid streaks, although characteristic for PXE, are not pathognomonic (Neldner, 1988). They can be encountered in a variety of metabolic and heritable disorders as well as in the setting of age-associated degenerative changes of the Bruch's membrane (Georgalas et al., 2009).

Cardiovascular Involvement

PXE affects the cardiovascular system primarily by mineralization of mid-sized arteries of the extremities where progressive calcification of the elastic media and intima inflicts the vessel damage (Mendelsohn et al., 1978; Kornet et al., 2004). As a result of these changes, clinical manifestations, including intermittent claudication, loss of peripheral pulses, reno-vascular hypertension, angina pectoris, and rarely, myocardial infarction, can result. There is an increased risk for cerebral ischemic attacks, and mineralized blood vessels of the gastric and intestinal mucosa can rupture leading to gastrointestinal bleeding (Goral et al., 2007). The vascular symptoms can cause significant morbidity and may even result in premature demise of the affected individual. Risk for cardiovascular complications is somewhat increased during pregnancy and labor. It should be noted, however, that in spite of extensive mineralization of placenta, PXE is not associated with markedly increased fetal loss or adverse obstetrical outcomes (Bercovitch et al., 2004; Tan and Rodeck, 2008). Thus, with appropriate counseling, there is no basis for advising women with PXE to avoid becoming pregnant.

While in most severe cases PXE is associated with considerable morbidity and occasional mortality from cardiovascular complications, the phenotypic spectrum of this disease is highly variable, with both inter- and intra-familial heterogeneity (Neldner, 1988; Sakata et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009a). In some families, involvement of a given organ system may be predominant, so that in some families the major findings are in the skin, while in other families the ocular findings predominate with little skin involvement. In other families, cardiovascular symptoms may be the major cause of morbidity, with relatively little skin or eye involvement.

The Mode of Inheritance

Adding to the complexity and diagnostic challenge of PXE were early suggestions that both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive forms of the disease exist (Pope, 1975). Recent advances of molecular genetics have established that PXE is exclusively an autosomal recessive disorder (Plomp et al., 2004; Ringpfeil et al., 2006). The early suggestions of the presence of autosomal dominant forms were based on clinical findings, mostly cutaneous, in individuals in two subsequent generations in some families, but this can in most cases be explained on basis of pseudo-dominance, often as a result of familial consanguinity (Ringpfeil et al., 2000, 2006; Chassaing et al., 2004). It should be noted that there are no fully documented reports of PXE in three subsequent generations, refuting the existence of classic Mendelian autosomal dominant inheritance. Obligate heterozygote carriers have essentially normal or very limited clinical phenotype but some cases have been reported to show microscopic changes of mineralization in the elastic fibers (Martin et al., 2007). A recent study has suggested that heterozygous carriers may occasionally have serious manifestations, particularly affecting the eyes (Martin et al., 2008). The carrier individuals may also be at increased risk for premature coronary artery disease (Trip et al., 2002). These observations may suggest a role for modifying genes or environmental factors in the mineralization processes.

MOLECULAR GENETICS OF PXE

Because the primary histopathology of the skin in PXE was noted to involve elastic fibers, the genes participating in the synthesis and assembly of the elastic fiber network were initially considered as a candidate gene/protein systems for mutations in this disease. These included elastin (ELN) on chromosome 7q, the elastin-associated microfibrillar proteins, such as fibrillin-1 and fibrillin-2 (FBN1 and FBN2) on chromosomes 15 and 5, and lysyloxidase (LOX), also on chromosome 15. However, with the cloning of the corresponding genes, genetic linkage analyses excluded these chromosomal regions as the sites of PXE associated genes (Christiano et al., 1992; Raybould et al., 1994). Subsequently, the positional cloning approaches provided strong evidence for linkage to the short-arm of chromosome 16, and refinement of the critical interval focused on an ~500 kb region that contained four genes, none of which had an obvious connection to the extracellular matrix of connective tissues in general or to the elastic fiber network in particular (Le Saux et al., 1999; Cai et al., 2000). Systematic sequencing of these candidate genes resulted in identification of the ABCC6 gene as the one harboring mutations in PXE (Ringpfeil et al., 2000; Le Saux et al., 2000; Bergen et al., 2000; Struk et al., 2000). This gene consists of 31 exons spanning approximately 75 kb of the human genome on chromosomal region 16p13.1 This region also contains two closely related, yet non-functional, 5’-pseudogenes which correspond to exons 1-9 and 1-4 of the coding gene, respectively (Pulkkinen et al., 2001). A close sequence similarity (over 99%) between the two pseudogenes and the coding gene complicates mutation detection at the 5’-end of the gene, although allele-specific primer sets have been designed for each exon of the coding gene, thus facilitating analysis without interference from the pseudogene sequences (Pfendner et al., 2007).

The ABCC6 Gene/Protein System

The ABCC6 gene is transcribed into an approximately 5 kb mRNA, and translated into a 165 kDa protein of 1,503 amino acids. This protein, ABCC6 (also known as multi-drug resistance associated protein 6 – MRP6) is a member of the C-family of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins (Borst and Elferink, 2002). ABCC6 has three hydrophobic transmembrane domains (TMD) consisting of 5, 6 and 6 transmembrane helices, as well as two intracellular nucleotide binding folds (NBFs) with highly conserved Walker motifs and ABC signature that are critical for the function of the protein in ATP-driven transmembrane transporters (Szakács et al., 2008). On the basis of sequence homology with other members of the C-family of the ABC proteins, particularly the prototype ABCC1, the ABCC6 has been postulated to function as an efflux transporter, and it has been shown to transport polyanionic, glutathione-conjugated molecules in an in vitro inside-out vesicle system (Iliás et al., 2002; Belinsky et al., 2002). The precise role of ABCC6 and the substrate specificity of this putative transporter in vivo are currently unknown. Nevertheless, the critical role of the ABCC6 gene in the pathogenesis of PXE has been confirmed by development of transgenic mice through targeted ablation of the corresponding mouse gene (Klement et al., 2005; Gorgels et al., 2005). The Abcc6-/- mice recapitulate the genetic, histopathologic and ultrastructural findings in patients with PXE, including progressive mineralization of connective tissues (Klement et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2007). Moreover, an alternative splice variant in Abcc6, leading to a 5-bp deletion, has been identified in dystrophic cardiac calcification (DCC) susceptible mouse strain C3H/HR, DBA/2Y and 1295S1/SVJ but not in DCC-resistant mouse C57BL/b, attesting to the role of the Abcc6 gene in mineralization processes (Aherrahrou et al., 2008).

ABCC6 Mutations in PXE

Well over 300 distinct mutations representing over 1000 mutant alleles have been encountered in the ABCC6 gene in patients with PXE (Miksch et al., 2005; Pfendner et al., 2007, 2008; Li et al., 2009a). The types of mutations include missense and nonsense mutations in 28 of the 31 exons of ABCC6, intronic mutations causing mis-splicing, small deletions or insertions resulting in frame shift of translation, as well as large deletions spanning part or the entire coding region of the gene and sometimes including flanking genes as well (Chassaing et al., 2007). Two recurrent mutations of high frequency have been identified: p.R1141X in exon 24 is the most common, particularly in Caucasian individuals, with a prevalence of approximately 30% of all pathologic PXE mutations (Pfendner et al., 2007). In addition, a recurrent AluI-mediated deletion of exons 23-29 (del23-29; p.A999-S1403del) has been found at least in one allele in up to 20% in US and 12% of European patients (Ringpfeil et al., 2001; Chassaing et al., 2004; Pfendner et al., 2007). Identification of additional recurrent nonsense mutations, as well as clustering of the missense mutations to exons 24 and 28 which code for the NBFs and on the domain-domain interfaces, have allowed the development of streamlined mutation detection strategies, with the overall detection rate of up to 99% (Hu et al., 2004; Pfendner et al., 2007; Fülöp et al., 2009). Thus, mutation analysis is now readily available for individuals suspected to have or to be at risk for PXE. As in the case of other heritable disorders with extensive mutation database, identification of mutations in the ABCC6 gene can be used for confirmation of the clinical diagnosis, carrier detection and presymptomatic identification of affected individuals. Although no specific treatment is presently available for PXE, early identification of the disease and increased surveillance for its sequela will undoubtedly improve the quality of life of the affected individuals.

PUTATIVE PATHOMECHANISMS OF PXE

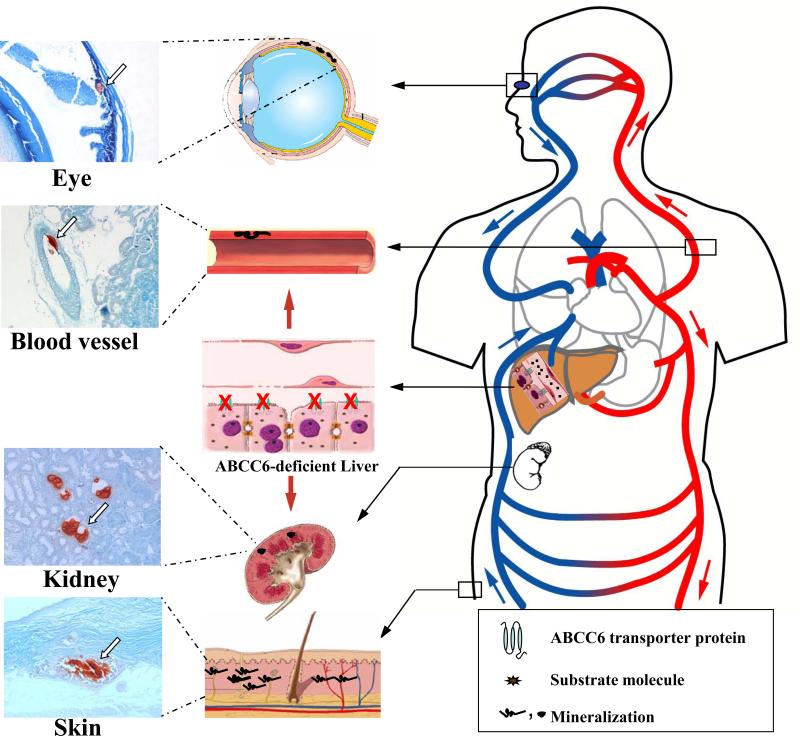

Histopathologic evaluation of skin and other affected tissues in PXE reveals progressive mineralization of connective tissues, particularly elastic structures, as the characteristic feature, and accumulation of calcium/phosphate in these lesions is apparently responsible for clinical manifestations in the skin, the eyes, and the cardiovascular system. As indicated above, the classic forms of PXE are caused by mutations in the ABCC6 gene, a putative efflux transporter. One of the early surprising observations was that this gene is primarily expressed in the liver, to a lesser extent in the proximal tubules of kidneys, and at very low level, if at all, in tissues clinically affected in PXE (Belinsky and Kruh, 1999; Scheffer et al., 2002). These observations raised an apparent dilemma concerning the pathomechanisms of PXE. Specifically, how do mutations in the gene expressed primarily in the liver result in mineralization of connective tissues in the skin, the eyes, and the blood vessels? To explain the potential mechanisms leading from ABCC6 mutations to ectopic mineralization in peripheral connective tissues in PXE, at least two general theories have been advanced. The “metabolic hypothesis” (Uitto et al., 2001) postulates that absence of ABCC6 activity primarily in the liver results in deficiency of circulating factors that are physiologically required to prevent aberrant mineralization under normal calcium and phosphate homeostatic conditions (Figure 1) (Li et al., 2009a). This postulate is predicated on previous identification of a number of proteins which serve as powerful anti-mineralization molecules in the circulation, including fetuin-A, matrix gla-protein (MGP), and ankylosis protein (ANK) (Jahnen-Dechent et al., 1997; Luo et al., 1997; Ryan et al., 2001). The “PXE cell hypothesis” postulates that lack of ABCC6 expression in the resident cells in clinically affected tissues, such as in skin fibroblasts or arterial smooth muscle cells, alters the biosynthetic expression profile and cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, associated with changes in the proliferative capacity of these cells. Specifically, cultured skin fibroblasts from patients with PXE have been shown to display enhanced synthesis of elastin and glycosaminoglycan/proteoglycan complexes, and they also demonstrate enhanced degradative potential because of elevated matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity (Passi et al., 1996; Quaglino et al., 2000, 2005). Finally, in support of this postulate are observations that the elastic structures in the skin that become mineralized in PXE do not appear morphologically normal, and they have been suggested to contain elastin which differs from elastin isolated from normal skin (Lebwohl et al., 1993; Sakuraoka et al., 1994).

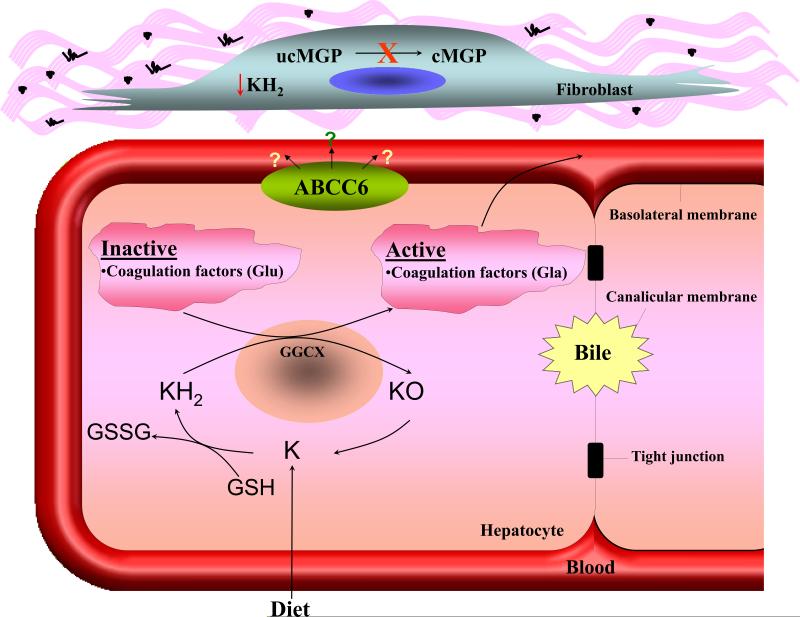

Figure 1. Illustration of the proposed “metabolic hypothesis” of PXE.

Under physiologic conditions, the ABCC6 protein is expressed in high levels in the liver and serves as an efflux pump on the baso-lateral surface of hepatocytes transporting critical metabolites from the intracellular milieau to the circulation (right side of the panel). In the absence of ABCC6 transporter activity in PXE, reduced concentrations of such substrate molecules, which may serve as physiologic anti-mineralization factors, are found in the circulation, resulting in mineralization of connective tissues in a number of organs, such as the eye, the arterial blood vessels, the kidneys and the skin (middle panel). The presence of mineralization is illustrated by histopathologic examination (Alizarin red stain) of tissues in Abcc6-/- mice that recapitulate the features of human PXE. (Modified from Jiang and Uitto, 2006, with permission).

In support of the “metabolic hypothesis,” it has been pointed out that clinical manifestations in patients with PXE are rarely present in early childhood, the onset of clinical findings is delayed, and the progression of the disease is slow, as reflected by accumulation of calcium/phosphate deposits in soft connective tissues of the affected organs. Serum from Abcc6-/- mice has been shown to lack the capacity to prevent calcium/phosphate precipitation in a cell-based in vitro assay (Jiang et al., 2007). Furthermore, serum from patients with PXE, when added to tissue culture medium of fibroblasts, has been shown to alter the expression of elastin, again suggesting the presence or absence of specific circulatory factors (Le Saux et al., 2006).

Grafting and Parabiotic Mouse Models

We have recently addressed the “metabolic hypothesis” by taking advantage of the Abcc6-/- mouse model that recapitulates features of human PXE, including late-onset (5-6 weeks after the birth), yet progressive, mineralization of connective tissues (Klement et al., 2005). In the first set of studies we performed skin grafting in which muzzle skin from Abcc6-/- (KO) mice or from their wild-type (WT) littermates, was grafted onto the back of Abcc6+/+ and Abcc6-/- mice (Jiang et al., 2009). The muzzle skin of mice contains vibrissae, and the connective tissue capsule surrounding the bulb of the vibrissae becomes reproducibly mineralized in Abcc6-/- mice at approximately 5 weeks, serving as an early and quantifiable biomarker of the mineralization process (Jiang et al., 2007). When muzzle skin from WT mice was grafted onto the back of KO mice at 4 weeks of age, mineralization ensued in subsequent two months. In contrast, no mineralization was observed in the muzzle skin from KO mice transplanted onto the back of WT mice. Since the capillaries in the graft regress while new vascular ingrowth occurs from the recipient wound bed to replace the regressing vessels, the survival of the skin graft is dependent on the re-establishment of circulation from the recipient animal, and the graft supplied by blood from the recipient mouse (Capla et al., 2006). As the Abcc6-/- mouse skin graft did not develop mineralization when placed on to Abcc6+/+ mouse, but the skin from WT mouse showed mineralization after grafting on to KO mouse, these findings suggest that circulating factors in the recipient's blood play an active role in the degree of mineralization of the graft, irrespective of the graft genotype (Jiang et al., 2009).

In another set of experiments, we have utilized parabiotic pairing, i.e., surgical joining of two mice to create a shared circulation between various Abcc6 genotypic mice (Jiang et al., 2010a). To prevent immune reaction between the parabiotic animals, all mice were bred to be Rag1-/-, i.e., these mice lacked mature T- and B-cells while granulocytes and macrophages were intact, resulting in “non-leaky” severe combined immune deficiency. Parabiotic pairing of mice was performed at 4 weeks of age, at the time of weaning and just before histologically detectable mineralization in the vibrissae of the Abcc6-/- mice takes place. Subsequent histopathological observations of the mineralization process at 8 weeks confirmed that KO mice, when paired with WT mice, developed much less mineralization than KO mice in KO+KO pairs. At the same time, WT or heterozygous mice either in homogenetic pairings or in heterogenetic pairing with KO mice developed no evidence of mineralization up to three months of age (Jiang et al., 2010a). Collectively, these experiments, combined with in vitro measurements of the anti-mineralization capacity of serum in KO mice, suggest that Abcc6-/- mice lack circulatory factors that in WT mice prevent precipitation of calcium/phosphate under normal homeostatic conditions.

PXE-LIKE CUTANEOUS FINDINGS AND VITAMIN K-DEPENDENT COAGULATION FACTOR DEFICIENCY

Adding to the diagnostic difficulties related to PXE, skin manifestations reminiscent of PXE can be found in a number of unrelated clinical conditions, both acquired and genetic (Neldner, 1988; Li et al., 2009a). For example, PXE-like cutaneous changes, even with ocular findings, can be found in a number of patients with beta-thalassemia and sickle cell anemia, yet these individuals do not harbor mutations in the ABCC6 gene (Baccarani-Conti et al., 2001; Hamlin et al., 2003). Recently, particularly intriguing observations with potential pathomechanistic implications for PXE have been made in patients with PXE-like cutaneous findings in association with vitamin K-dependent multiple coagulation factor deficiency (Vanakker et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009b,c). These patients demonstrate primary cutaneous lesions similar to those seen in PXE, i.e., small, yellowish papules and excessive folding and sagging of the skin with loss of recoil. These patients have been described as having combined clinical features of both PXE and cutis laxa (Vanakker et al., 2007). However, cutaneous lesions in these patients depict characteristic mineralization of elastic structures similar to PXE, findings that are not present in patients with cutis laxa (Uitto and Ringpfeil, 2007).

Mutations in the GGCX Gene

Molecular analysis of some of the patients with PXE-like cutaneous and bleeding disorder has revealed mutations in the GGCX gene which encodes an enzyme responsible for γ -glutamyl-carboxylation of proteins, such as the vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors and matrix gla-protein (Figure 2) (Berkner, 2005). Some of these patients demonstrate inactivating missense mutations in both alleles of GGCX, and clinically they demonstrate both the PXE-like cutaneous findings and the bleeding tendency (Vanakker et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009c). In some cases, the GGCX mutations are heterozygous in combination with a heterozygous ABCC6 mutation (Li et al., 2009b). In a particularly illustrative family, individuals were shown to be heterozygous for a nonsense mutation (p.R1141X) in ABCC6 and a missense mutation (p.V255M) in GGCX. These patients have cutaneous findings consistent with PXE but without any coagulation disorder, suggesting digenic inheritance of PXE in this family (Li et al., 2009b).

Figure 2. The role of vitamin K in activation of gla-proteins.

Vitamin K serves as a co-factor of activation of blood coagulation factors and matrix gla-protein (MGP) by γ-glutamyl carboxylase encoded by the GGCX gene. The γ-glutamyl carboxylase activates coagulation factors (Glu→ Gla), the carboxylated forms are secreted into circulation from hepatocytes and are required for normal blood coagulation (lower panel). In peripheral connective tissue cells, such as fibroblasts, similar activation of uncarboxylated MGP (ucMGP) normally takes place resulting in carboxylated matrix gla-protein (cMGP) which is required for prevention of unwanted mineralization of peripheral tissues under normal calcium and phosphate homeostatic conditions (upper panel). It has been postulated that ABCC6 serves as a transporter molecule transporting vitamin K derivatives, such as the reduced form (KH2) conjugated with glutathione (GSH). In the absence of ABCC6 transporter activity in PXE, the specific vitamin K co-factor concentrations in the serum and in fibroblasts are reduced resulting in deficient activation of MGP and allowing ectopic mineralization in the adjacent connective tissue to take place. (Modified from Li et al., 2009a, with permission).

The identification of missense mutations in GGCX, accompanied with PXE-like cutaneous changes and histopathologically demonstrable mineralization of elastic structures in the dermis, potentially provides insights into the pathomechanisms of classic PXE. One postulate revolves around vitamin K-dependent γ-glutamyl-carboxylation of matrix gla-protein (Shearer, 2000). This low-molecular weight protein has the capacity to prevent untowards mineralization under normal homeostatic levels of calcium and phosphorus, as demonstrated by development of the corresponding KO mouse, Mgp-/-, characterized by extensive mineralization of connective tissues (Luo et al., 1997). However, in order to be active in its anti-mineralization function, this protein has to be in a fully carboxylated form (cMGP), while under-carboxylated form of the protein (ucMGP) is inactive (Figure 2). Examination of cutaneous lesions in patients with PXE and in Abcc6-/- mice with specific antibodies that distinguish these two different forms of MGP has suggested that MGP is undercarboxylated in these clinical situations (Gheduzzi et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007). A potential explanation for under-carboxylation of MGP in classic PXE revolves around the possibility that the ABCC6 protein participates in transmembrane transport and redistribution of vitamin K derivatives, specifically its reduced form (KH2), an obligatory co-factor of γ-glutamyl-carboxylase (Borst et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009a). More precisely, one could postulate that KH2, especially when conjugated with glutathione which renders it soluble in aqueous environment, could serve as a transport substrate for ABCC6. In patients with PXE, the absence of ABCC6 transporter activity could result in reduced concentration of KH2 in circulation and in peripheral cells, such as dermal fibroblasts, leading to deficient γ-carboxylation of MGP and allowing subsequent mineralization of the adjacent connective tissues (Figure 2). Because the concentrations of KH2 inside the hepatocytes remain unaffected, the γ-carboxylation of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors remains unperturbed and no bleeding tendency accompanies PXE due to mutations in ABCC6. It should be noted that if this postulate is proven correct, it would raise the possibility that administration of the critical form of vitamin K or its derivatives directly into circulation, bypassing the liver, might counteract the progressive mineralization of connective tissues in PXE and might ameliorate, or even cure, this disease.

GENETIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL MODIFYING FACTORS

As indicated above, the classic forms of PXE are caused by mutations in the ABCC6 gene, and well over 300 distinct mutations have been disclosed in different families. Careful examination of the mutation database in the context of clinical manifestations and phenotypic variability in different families has not provided clear-cut genotype/phenotype correlations (Pfendner et al., 2007, 2008), and therefore, the reasons for the considerable phenotypic variability, both intra- and inter-familial, are not clear.

Genetic Modifiers

Recent studies examining the effects of different genetic backgrounds on the mineralization process in Abcc6-/- mouse model have shown that, besides the specific modulation by haploinsufficiency of the Ggcx gene, the general genetic background can delay the onset of the mineralization (Li and Uitto, 2010a). It is conceivable, therefore, that modifier genes may also exist in humans and that they modulate both the age of onset and the extent of mineralization in patients with PXE, providing partial explanation for the phenotypic variability. In addition to GGCX, recent studies have suggested genetic modulation of PXE in humans by a few other genes as well. For example, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the promoter region of the secreted phosphoprotein 1 gene (SPP1, also known as osteopontin) were shown to be associated with PXE, contributing to the susceptibility to this disease (Hendig et al., 2007). Osteopontin is a major local inhibitor of ectopic calcification that has been associated with Wnt signaling (Vattikuti and Towler, 2004). In other studies, polymorphisms of the xylosyltransferase genes were shown to be involved in the severity of the disease (Schön et al., 2006). Specifically, variations in the XYLT were associated with higher internal organ involvement, while a specific missense variation (p.A115S) in the XT-I gene resulted in high serum xylosyltransferase activity, potentially reflecting increased remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Specific SNPs in the vascular endothelial growth factor gene (VEGFA) are associated with severe retinopathy (Zarbock et al., 2009). Finally, genetic variations in the antioxidant genes are risk factors for early disease onset of PXE (Zarbock et al., 2007). This observation is in concurrence with previous demonstrations that oxidative stress may play a role in the development of PXE (Li et al., 2008; Pasquali-Ronchetti et al., 2006).

The Role of Diet

In addition to genetic modifiers, several lines of evidence suggest that diet may affect the severity of the disease in PXE. First, early retrospective surveys suggested that individuals with history of extensive intake of dairy products, rich in calcium and phosphate, may demonstrate relatively severe disease later in life (Neldner et al., 1988; Renie et al., 1984). More recently, genetically controlled studies utilizing Abcc6-/- mice as a model system have demonstrated that the mineral content of their diet can clearly modulate the ectopic mineralization process (LaRusso et al., 2008, 2009; Li et al., 2010b). Specifically, magnesium carbonate, when added to the mouse diet in amounts that increase the magnesium concentration by 5-fold over that in standard diet, is able to prevent the ectopic mineralization noted in Abcc6-/- mice (Li et al., 2010b). Conversely, an experimental diet with low magnesium was shown to accelerate the mineralization process in Abcc6-/- mice, as compared to the corresponding mice kept on a standard control diet (Li and Uitto, 2010a). These findings support the notion that changes in the diet can alter the age of onset and extent of mineralization in PXE. These observations also suggest that dietary magnesium might be helpful for treatment of patients with PXE, a notion that could be tested in carefully controlled clinical trials. Collectively, the evidence indicating modulation of the PXE phenotype by genetic factors and diet support the notion that PXE is a metabolic disease at the genome-environment interface (Uitto et al., 2001).

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE – TOWARDS TREATMENT AND CURE

As summarized above, tremendous progress has been made in understanding the molecular genetics of PXE since report of the first pathogenic mutations in the ABCC6 gene less than a decade ago (Ringpfeil et al., 2000). The information on specific mutations has been helpful in confirming the diagnosis which is sometimes questionable on the basis of clinical findings only. This information has also been helpful in providing genetic counseling on the risk of recurrence in families with PXE, and the mutation analysis can be used for identification of affected individuals prior to development of overt clinical signs in families with previous history of this condition. Finally, development of animal models, and particularly the Abcc6-/- mice, that recapitulate the features of PXE, has been extremely helpful towards understanding the pathomechanistic details leading from mutations in the ABCC6 gene to ectopic mineralization of peripheral connective tissues. In spite of this significant progress, however, the fact remains that there is no effective or specific treatment for PXE at the present.

Treatment of Ocular Neovascularization

Significant promise is offered by recent attempts to treat retinal manifestations of PXE. One of the most devastating complications of PXE is gradual loss of visual acuity which occasionally can lead to complete central blindness. These clinical symptoms are due to choroidal neovascularization secondary to the angiod streaks. Since vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a critical component of the neovascularization process in general, recent studies have tested the efficacy of intravitreal injection of pharmaceutical agents, such as bevacizumab (Avastin), an antagonist of VEGF and inhibitor of neovascularization. A number of preliminary reports have suggested that intravitreal bevacizumab may be a promising tool for the long-term control of choriod neovascularization in PXE (see Kovach et al., 2009; Sawa et al., 2009; Wiegand et al., 2009). At the same time, other modalities and different strategies to treat retinal manifestations are being developed, including thermal laser coagulation, photodynamic therapy, and intravitreal injections of other drugs inhibiting VEGF (Finger et al., 2009).

Development of Molecular Therapies

Different general approaches could be envisioned to be helpful towards finding a treatment, and perhaps cure, of PXE. For example, prevention of mineralization irrespective of its etiology could be helpful in lessening the clinical manifestations of PXE. It is apparent that the progressive mineralization of connective tissues, as for example, the mineralization of arterial blood vessels is responsible for the cardiovascular manifestations, and mineralization of the Bruch's membrane is the primary cause of the ocular findings. One potential way of preventing, and perhaps reversing, ectopic mineralization is the manipulation of diet. Specifically, experiments utilizing the Abcc6-/- animal model, have demonstrated that supplementation of the diet with magnesium is able to completely prevent the ectopic mineralization up to 6 months of age (LaRusso et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010b). Conversely, diet low in magnesium and high in phosphate, was shown to exacerbate the mineralization process in PXE mice (Li and Uitto, 2010a). Thus, further studies examining the precise role of different mineral components in the diet, using the preclinical animal models, might lead to clinical trials to test the feasibility of this approach towards treatment of PXE.

Another potentially effective way of preventing the ectopic mineralization revolves around the manipulation of anti-mineralization factors in the circulation. One of such molecules is fetuin-A, a powerful anti-mineralization factor that under normal physiologic calcium and phosphate homeostatic conditions is able to prevent aberrant mineralization. The concentrations of fetuin-A both in serum of patients with PXE as well as in the Abcc6-/- mouse have been shown to be reduced (Hendig et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2007). The concept of fetuin-A serving as an anti-mineralization factor has been derived from observations that genetic KO mouse developed by targeted ablation of the fetuin-A gene demonstrates extensive mineralization of connective tissues, particularly of the arterial blood vessels (Jahnen-Dechent et al., 1997). Furthermore, in an in vitro cell-based mineralization assay system, recombinant fetuin-A has been shown to prevent calcium/phosphate precipitation in a dose-dependent manner (Jiang et al., 2007). These observations then raise the possibility that increasing the fetuin-A concentrations in the patients’ blood may prevent excessive mineralization. This could be achieved by introduction of recombinant fetuin-A directly to the circulation of the patients with PXE. At this point, however, the half-life of fetuin-A is unknown, and other issues related to protein replacement therapy, such as antibody formation, need to be addressed in preclinical studies. Another potential approach to introduce fetuin-A to the circulation could utilize gene therapy or cell transfer approaches. For example, introduction of an expression vector containing a fetuin-A cDNA under liver specific promoter has been shown to increase the synthesis of fetuin-A with subsequent lessening of the mineralization in Abcc6-/- mice (Jiang et al., 2010b). Again, details of such approaches need to be worked out in preclinical model systems prior to initiating clinical trials in patients with PXE.

Finally, strategies aimed at regeneration of liver or introduction of stem-cells with capability to differentiate into hepatocytes, could potentially result in restoration of functional ABCC6 transporter activity. In a straightforward manner, one would envision that liver transplant or a partial lobar replacement could result in restoration of the ABCC6 function. In the case of stem-cell therapy, it appears that a significant portion of the hepatocytes need to be replaced in order to achieve a functional ABCC6 transport system in the liver. Consideration of all these options has to include extensive preclinical animal studies, which are currently ongoing in several laboratories, as well as careful consideration of the risk/benefit ratios. Nevertheless, development of molecular strategies, as exemplified by progress in treatment of other heritable skin disease (Tamai et al., 2009; Uitto, 2009), hopefully provides new avenues for treatment and eventually cure for PXE, a currently intractable disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors’ original studies were supported by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, NIH/NIAMS Grants R01 AR28450, R01 AR52627, and R01 AR55225, and by the Dermatology Foundation. GianPaolo Guercio assisted in preparation of this publication.

Abbreviations

- PXE

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- KO

knock-out

- WT

wild-type

- MGP

matrix gla-protein

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Aherrahrou Z, Doegring LC, Ehlers E-M, Liptau H, Depping R, Linsel-Nitschke P, et al. An alternative splice variant in Abcc6, the gene causing dystrophic calcification, leads to protein deficiency in C3H/He Mice. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7608–7615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccarani-Contri M, Bacchelli B, Boraldi F, Quaglino D, Taparelli F, Carnevali E, et al. Characterization of pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like lesions in the skin of patients with beta-thalassemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:33–39. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.110045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer F. Recherches sur les charactères anatomiques du xanthelasma. Arch Physiol. 1884;4:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Belinsky MG, Kruh GD. MOAT-E (ARA) is a full length MRP/cMOAT subfamily transporter expressed in kidney and liver. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1342–1349. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belinsky MG, Chen ZS, Shchaveleva I, Zeng H, Kruh GD. Characterization of the drug resistance and transport properties of multi-drug resistance protein 6 (MRP6, ABCC6). Cancer Res. 2002;62:6172–6177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercovitch L, Leroux T, Terry S, Weinstock MA. Pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1011–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen AA, Plomp AS, Schuurman EJ, Terry S, Breuning M, Dauwerse H, et al. Mutations in ABCC6 cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:228–231. doi: 10.1038/76109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkner KL. The vitamin K-dependent carboxylase. Ann Rev Nutr. 2005;25:127–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst P, Elferink RO. Mammalian ABC transporters in health and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:537–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.102301.093055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst P, van de Wetering K, Schlingemann R. Does the absence of ABCC6 (Multidrug Resistance Protein 6) in patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum prevent the liver from providing sufficient vitamin K to the periphery? Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1575–1579. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.11.6005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Struk B, Adams MD, Ji W, Haaf T, Kang HL, et al. A 500-kb region on chromosome 16p13.1 contains the pseudoxanthoma elasticum locus: high-resolution mapping and genomic structure. J Mol Med. 2000;78:36–46. doi: 10.1007/s001090000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capla JM, Ceradini DJ, Tepper OM, Callaghan MJ, Bhatt KA, Galiano RD, et al. Skin graft vascularization involves precisely regulated regression and replacement of endothelial cells through both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:836–844. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000201459.91559.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlborg U. Study of circulatory disturbances, pulse wave velocity and pressure pulses in large arteries in cases of pseudoxanthoma elasticum and angioid streaks: a contribution to the knowledge of function of the elastic tissue and the smooth muscles in larger arteries. Acta Med Scand. 1944;151:1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing N, Martin L, Mazereeuw J, Barrié L, Nizard S, Bonafé JL, et al. Novel ABCC6 mutations in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:608–613. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing N, Martin L, Calvas P, Le Bert M, Hovnanian A. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a clinical, pathophysiological and genetic update including 11 novel ABCC6 mutations. J Med Genet. 2005;42:881–892. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing N, Martin L, Bourthoumieu S, Calvas P, Hovnanian A. Contribution of ABCC6 genomic rearrangements to the diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum in French patients. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:1046. doi: 10.1002/humu.9509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauffard MA. Xanthelasma disséminé et symmétrique sans insufficiance hépatique. Bull Soc Med Hop Paris. 1889;6:412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Christiano AM, Lebwohl MG, Boyd CD, Uitto J. Workshop on pseudoxanthoma elasticum: molecular biology and pathology of the elastic fibers. Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:660–663. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12668156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darier J. Pseudo-xanthome élastique. IIIe Congrès Intern de Dermat de Londres. 1896;5:289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, Götting C, Szliska C, Scholl HP, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272–285. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fülöp K, Barna L, Symmons O, Závodszky P, Váradi A. Clustering of disease-causing mutations on the domain-domain interfaces of ABCC6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379:706–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgalas I, Papaconstantinou D, Koutsandrea C, Kalantzis G, Karagiannis D, Georgopoulos G, et al. Angioid streaks, clinical course, complications, and current therapeutic management. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5:81–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheduzzi D, Boraldi F, Annovi G, DeVincenzi CP, Schurgers LJ, Vermeer C, et al. Matrix Gla protein is involved in elastic fiber calcification in the dermis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum patients. Lab Invest. 2007;87:998–1008. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goral V, Demir D, Tuzun Y, Keklikci U, Buyulbayram H, Bayan K, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, as a repetitive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage cause in a pregnant woman. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3897–3899. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i28.3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgels TG, Hu X, Scheffer GL, van der Wal AC, Toonstra J, de Jong PT, et al. Disruption of Abcc6 in the mouse: Novel insight in the pathogenesis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1763–1773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönblad E. Angioid streaks – pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Acta Ophthalmol. 1929;7:329. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin N, Beck K, Bacchelli B, Cianciulli P, Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Le Saux O. Acquired pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like syndrome in beta-thalassaemia patients. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:852–854. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendig D, Schulz V, Arndt M, Szaliska C, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Role of serum fetuin-A, a major inhibitor of systemic calcification, in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Clin Chem. 2006;52:227–234. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.059253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendig D, Arndt M, Szliska C, Kleesiek K, Götting C. SPP1 promoter polymorphisms: identification of the first modifier gene for pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Clin Chem. 2007;53:829–836. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.083675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Plomp A, Gorgels T, Brink JT, Loves W, Mannens M, et al. Efficient molecular diagnostic strategy for ABCC6 in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Genet Test. 2004;8:292–300. doi: 10.1089/gte.2004.8.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliás A, Urban Z, Seidl TL, Le Saux O, Sinkó E, Boyd CD, et al. Loss of ATP-dependent transport activity in pseudoxanthoma elasticum-associated mutants of human ABCC6 (MRP6). J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16860–16867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110918200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnen-Dechent W, Schinke T, Trindl A, Müller-Esterl W, Sablitzky F, Kaiser S, et al. Cloning and targeted deletion of the mouse fetuin gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31496–31503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Li Q, Uitto J. Aberrant mineralization of connective tissues in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum: systemic and local regulatory factors. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1392–4102. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Matsuzaki Y, Li K, Uitto J. Transcriptional regulation and characterization of the promoter region of the human ABCC6 gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:325–335. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a metabolic disease? J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1440–1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Endo M, Dibra F, Wang K, Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a metabolic disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:348–354. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Oldenburg R, Otsuru S, Grand-Pierre AE, Horwitz EM, Uitto J. Parabiotic heterogenetic pairing of Abcc6-/-;Rag1-/- mice and their wild-type counterparts halts ectopic mineralization in a murine model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. 2010a. (submitted for publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jiang Q, Dibra F, Li MD, Uitto J. Over-expression of fetuin-A counteracts ectopic mineralization in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (Abcc6-/-). J Invest Dermatol. 2010b doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.423. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klement JF, Matsuzaki Y, Jiang Q-J, Terlizzi J, Choi HY, Fujimoto N, et al. Targeted ablation of the ABCC6 gene results in ectopic mineralization of connective tissues. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8299–8310. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8299-8310.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornet L, Bergen AA, Hoeks AP, Cleutjens JP, Oostra RJ, Daemen MJ, et al. In patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum a thicker and more elastic carotid artery is associated with elastin fragmentation and proteoglycans accumulation. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach JL, Schwartz SG, Hickey M, Puliafito CA. Thirty-two month follow-up of successful treatment of choroidal neovascularization from angioid streaks with intravitreal bevacizumab. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2009;40:77–79. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20090101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRusso J, Jiang Q, Li Q, Uitto J. Ectopic mineralization of connective tissue in Abcc6-/- mice: Effects of dietary modifications and a phosphate binder – a preliminary study. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:203–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRusso J, Li Q, Jiang Q, Uitto J. Elevated dietary magnesium prevents connective tissue mineralization in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (Abcc6-/-). J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1388–1394. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Saux O, Urban Z, Göring HH, Csiszar K, Pope FM, Richards A, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum maps to an 820-kb region of the p13.1 region of chromosome 16. Genomics. 1999;62:1–10. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Saux O, Urban Z, Tschuch C, Csiszar K, Bacchelli B, Quaglino D, et al. Mutations in a gene encoding an ABC transporter cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:223–227. doi: 10.1038/76102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Saux O, Beck K, Sachsinger C, Treiber C, Göring HH, Curry K, et al. Evidence for a founder effect for pseudoxanthoma elasticum in the Afrikaner population of South Africa. Hum Genet. 2002;111:331–338. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0808-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Saux O, Bunda S, VanWart CM, Douet V, Got L, Martin L, et al. Serum factors from pseudoxanthoma elasticum patients alter elastic fiber formation in vitro. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1497–1505. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebwohl M, Schwartz E, Lemlich G, Lovelace O, Shaikh-Bahai F, Fleischmajer R. Abnormalities of connective tissue components in lesional and non-lesional tissue of patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dermatol Res. 1993;285:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01112912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Schurgers LJ, Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: Reduced gamma-glutamyl carboxylation of matrix gla protein in a mouse model (Abcc6-/-). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum: Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Diet in a Mouse Model (Abcc6-/-). J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1160–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, Váradi A, Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: Clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Derm. 2009a;18:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Grange DK, Armstrong NL, Whelan AJ, Hurley MY, Rishavy MA. Mutations in the GGCX and ABCC6 genes in a family with pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2009b;129:553–563. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Schrugers LJ, Smith ACM, Tsokos M, Uitto J, Cowen EW. Co-existent pseudoxanthoma elasticum and vitamin K-dependent coagulation factor deficiency. Am J Pathol. 2009c;174:534–539. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Uitto J. The mineralization phenotype in Abcc6-/- mice is affected by Ggcx gene deficiency and genetic background – a model for pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Mol Med. 2010a doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0522-8. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, LaRusso J, Grand-Pierre AE, Uitto J. Magnesium carbonate-containing phosphate binder prevents connective tissue mineralization in Abcc6-/- mice – potential for treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. 2010b. (submitted for publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, Pinero GJ, Loyer E, Behringer RR, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386:78–81. doi: 10.1038/386078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Chassaing N, Delaite D, Esteve E, Maitre F, Le Bert M. Histological skin changes in heterozygote carriers of mutations in ABCC6, the gene causing pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Maître F, Bonicel P, Daudon P, Verny C, Bonneau D, et al. Heterozygosity for a single mutation in the ABCC6 gene may closely mimic PXE: consequences of this phenotype overlap for the definition of PXE. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:301–306. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn G, Bulkley BH, Hutchins GM. Cardiovascular manifestations of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1978;102:298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miksch S, Lunsden A, Guenther UP, Foernzler D, Christen-Zäch S, Daugherty C, et al. Molecular genetics of pseudoxanthoma elasticum: Type and frequency of mutations in ABCC6. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:235–248. doi: 10.1002/humu.20206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naorui M, Boisseau C, Bonicel P, Daudon P, Bonneau D, Chassaing N, et al. Manifestations of pseudoxanthoma elasticum in childhood. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:635–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neldner KH. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Clin Dermatol. 1988;6:1–159. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(88)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Garcia-Fernandez MI, Boraldi F, Quaglino D, Gheduzzi D, De Vincenzi Paolinelli C, et al. Oxidative stress in fibroblasts from patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum: possible role in the pathogenesis of clinical manifestations. J Pathol. 2006;208:54–61. doi: 10.1002/path.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passi A, Albertini R, Baccarani Contri M, de Luca G, de Paepe A, Pallavicini G, et al. Proteoglycan alterations in skin fibroblast cultures from patients affected with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Cell Biochem Funct. 1996;14:111–120. doi: 10.1002/cbf.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfendner EG, Vanakker OM, Terry SF, Vourthis S, McAndrew PE, McClain MR, et al. Mutation detection in the ABCC6 gene and genotype-phenotype analysis in a large international case series affected by pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Med Genet. 2007;44:621–628. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfendner E, Uitto J, Gerard GF, Terry SF. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: Genetic diagnostic markers. Exp Opinion Med Diagn. 2008;2:1–17. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp AS, Hu X, De Jong PT, Bergen AA. Does autosomal dominant pseudoxanthoma elasticum exist? Am J Med Genet. 2004;126:403–412. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope FM. Historical evidence for the genetic heterogeneity of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Br J Dermatol. 1975;92:493–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb03117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen L, Nakano A, Ringpfeil F, Uitto J. Identification of ABCC6 pseudogenes on human chromosome 16p: implications for mutation detection in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Hum Genet. 2001;109:356–365. doi: 10.1007/s004390100582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaglino D, Boraldi F, Barbieri D, Croce A, Tiozzo R, Pasquali-Ronchetti I. Abnormal phenotype of in vitro dermal fibroblasts from patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE). Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1501:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaglino D, Sartor L, Garbisa S, Boraldi F, Croce A, Passi A, et al. Dermal fibroblasts from pseudoxanthoma elasticum patients have raised MMP-2 degradative potential. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1741:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay M, Greenberg T, Lombard Z, Labrum R, Lubbe S, Aron S, et al. Spectrum of genetic variation at the ABCC6 locus in South Africans: pseudoxanthoma elasticum patients and healthy individuals. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;54:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould MC, Birley AJ, Moss C, Hultén M, McKeown CM. Exclusion of an elastin gene (ELN) mutation as the cause of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) in one family. Clin Genet. 1994;45:48–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1994.tb03990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renie WA, Pyeritz RE, Combs J, Fine SL. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: High calcium intake in early life correlates with severity. Am J Med Genet. 1984;19:235–244. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320190205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringpfeil F, Lebwohl MG, Christiano AM, Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: mutations in the MRP6 gene encoding a transmembrane ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6001–6006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100041297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringpfeil F, Nakano A, Uitto J, Pulkkinen L. Compound heterozygosity for a recurrent 16.5-kb Alu-mediated deletion mutation and single-base-pair substitutions in the ABCC6 gene results in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:642–652. doi: 10.1086/318807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringpfeil F, McGuigan K, Fuchsel L, Kozic H, Larralde M, Lebwohl M, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a recessive disease characterized by compound heterozygosity. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:782–786. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan LM. The ank gene story. Arthitis Res. 2001;3:77–79. doi: 10.1186/ar143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata S, Su JC, Robertson S, Win M, Chow C. Varied presentations of pseudoxanthoma elasticum in a family. J Pediatr Child Health. 2006;42:817–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuraoka K, Tajima S, Nishikawa T, Seyama Y. Biochemical analyses of macromolecular matrix components in patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Dermatol. 1994;21:98–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1994.tb01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa M, Gomi F, Tsujikawa M, Sakaguchi H, Tano Y. Long-term results of intravitreal bevacizumab injection for choroidal neovascularization secondary to angioig streaks. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.04.026. (in press: PMID: 19541288) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer GL, Hu X, Pijnenborg AC, Wijnholds J, Bergen AA, Scheper RJ. MRP6 (ABCC6) detection in normal human tissues and tumors. Lab Invest. 2002;82:515–518. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schön S, Schulz V, Prante C, Hendig D, Szliska C, Kuhn J. Polymorphisms in the xylosyltransferase genes cause higher serum XT-I activity in patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) and are involved in a severe disease course. J Med Genet. 2006;43:745–749. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.040972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer MJ. Role of vitamin K and Gla proteins in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis and vascular calcification. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2000;3:433–438. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Z Haut Geschlechtskr. 1929;31:689–694. [Google Scholar]

- Struk B, Cai L, Zäch S, Ji W, Chung L, Lumsden A, et al. Mutations of the gene encoding the transmembrane transporter protein ABCC6 cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Mol Med. 2000;78:282–286. doi: 10.1007/s001090000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szakács G, Váradi A, Ozvegy-Lacka C, Sarkadi B. The role of ABC transporters in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity (ASME-Tox). Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai K, Kaneda Y, Uitto J. Molecular therapies for heritable blistering diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan WC, Rodeck CH. Placental calcification in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Ann Acad Med Singapaore. 2008;37:598–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trip MD, Smulders YM, Wegman JJ, Hu X, Boer JM, ten Brink JB, et al. Frequent mutation in the ABCC6 gene (R1141X) is associated with a strong increase in the prevalence of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2002;106:773–775. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028420.27813.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto J. Progress in heritable skin diseases: translational implications of mutation analysis and prospects of molecular therapies. Act Derm Venereol. 2009;89:228–235. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto J, Pulkkinen L, Ringpfeil F. Molecular genetics of pseudoxanthoma elasticum – A metabolic disorder at the environment-genome interface? Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:13–17. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(00)01869-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto J, Ringpfeil F. Heritable diseases affecting the elastic fibers: cutis laxa, pseudoxanthoma elasticum and related disorders. In: Rimoin DL, Connor JM, Pyeritz RE, Korf BR, editors. Principles and practice of genetics. Fifth Ed Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 3647–3670. [Google Scholar]

- Vanakker OM, Martin L, Gheduzzi D, Leroy BP, Loeys BL, Guerci VI, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like phenotype with cutis laxa and multiple coagulation factor deficiency represents a separate genetic entity. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;27:581–587. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vattikuti R, Towler DA. Osteogenic regulation of vascular calcification: an early perspective. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E686–E696. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00552.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand TW, Rogers AH, McCabe F, Reichel E, Duker JS. Intravitreal bevacizumabf (Avastin) treatment of choroidal neovascularization in patients with angioid streaks. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:47–51. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.143461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbock R, Hendig D, Szliska C, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetic variations in antioxidant genes are risk factors for early disease onset. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1734–1740. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.088211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbock R, Hendig D, Szliska C, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms as prognostic markers for ocular manifestations in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3344–3351. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]