Abstract

Development of personalized treatment regimens is hampered by lack of insight into how individual animal models reflect subsets of human disease, and autoimmune and inflammatory conditions have proven resistant to such efforts. Scleroderma is a lethal autoimmune disease characterized by fibrosis, with no effective therapy. Comparative gene expression profiling showed that murine sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease (sclGVHD) approximates an inflammatory subset of scleroderma estimated at 17% to 36% of patients analyzed with diffuse, 28% with limited, and 100% with localized scleroderma. Both sclGVHD and the inflammatory subset demonstrated IL-13 cytokine pathway activation. Host dermal myeloid cells and graft T cells were identified as sources of IL-13 in the model, and genetic deficiency of either IL-13 or IL-4Rα, an IL-13 signal transducer, protected the host from disease. To identify therapeutic targets, we explored the intersection of genes coordinately up-regulated in sclGVHD, the human inflammatory subset, and IL-13–treated fibroblasts; we identified chemokine CCL2 as a potential target. Treatment with anti-CCL2 antibodies prevented sclGVHD. Last, we showed that IL-13 pathway activation in scleroderma patients correlated with clinical skin scores, a marker of disease severity. Thus, an inflammatory subset of scleroderma is driven by IL-13 and may benefit from IL-13 or CCL2 blockade. This approach serves as a model for personalized translational medicine, in which well-characterized animal models are matched to molecularly stratified patient subsets.

Scleroderma or systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a clinically heterogeneous rheumatologic disease characterized by tissue fibrosis of skin, internal organs, and blood vessels.1 Variants include i) diffuse systemic involvement (diffuse SSc), ii) limited cutaneous disease with more severe vascular insults (limited SSc), and iii) localized but disfiguring skin sclerosis (morphea). Therapeutic options for this disease are limited to medications that address only disease symptoms or end-organ manifestations, falling well short of the dramatic strides made in the treatment of other rheumatologic conditions. Discovery of new agents for SSc remains elusive, because the mechanisms underlying fibrosis in this disease are incompletely understood.1

A major factor hindering progress is lack of consensus on an animal model that accurately approximates the human disease. Given the clinical and molecular heterogeneity of SSc, however, it is unlikely that any one model will accurately reflect the entire spectrum of disease.2–4 For decades, murine graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) has been used as a model of SSc.3 In 2004, Ruzek et al5 described a modification of this model (sclGVHD) using immunodeficient Rag2−/− hosts. Although this model recapitulates the histological and serological features of SSc, including vasculopathy, it is unclear whether this is due to intrinsic similarities in disease pathogenesis or a confluence of tissue damage patterns occurring via disparate mechanisms. Disentangling these two possibilities is a common challenge facing all investigators using animals to model human disease. With the present study, a systematic approach to this challenge is implemented via cross-species expression profiling, followed by validation and mechanistic studies in the mouse model and in patient samples.

Expression profiling of SSc skin has documented distinct intrinsic gene expression signatures (namely, diffuse-proliferation, inflammatory, limited, and normal-like), identifying subsets of patients who develop fibrosis via different pathogenic mechanisms.4,6 Pathway analysis of these signatures can define the activation of specific signaling pathways in the context of disease.6,7 For example, the TGFβ pathway is activated in the SSc diffuse-proliferation subset but not in other groups,6 and data suggest that this subset may respond to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib.8 In contrast, the pathogenic mechanisms underlying the inflammatory, limited, and normal-like subsets have not been defined. Genome-wide expression profiling, which allows for direct comparison of molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypes in human diseases and mouse models, has been applied predominantly to oncologic disease.9–12 The identification of common deregulated pathways between human diseases and their models may point to therapeutic targets that can rapidly be evaluated in functional studies in the animal model and thus lead to clinical trials targeting specific patient subsets.

Using comparative gene expression profiling, we identified striking similarities between the sclGVHD model and the inflammatory subset of SSc patients, which represents 17% (3/17) and 36% (8/22) of diffuse disease patients in two published4,13 cohorts, as well as 28% (2/7) of patients with limited disease and all (3/3) patients analyzed with localized scleroderma (morphea).4 Both the inflammatory subset of SSc and murine sclGVHD display robust activation of IL-13 signaling, whose functional importance is validated using hosts deficient in either IL-13 or IL-4Rα, a required component of IL-13 signaling. We identified graft T cells and host dermal macrophages characterized by a mixed type I (M1) and type II (M2) activation profile as the cellular sources of IL-13. To identify downstream mediators of IL-13, we examined the overlap of multiple independent data sets and identified CCL2 as a key IL-13 regulated gene. Accordingly, therapeutic neutralization of CCL2 completely blocks sclGVHD. Last, we showed in a cohort of early SSc patients that IL-13 pathway activation correlates with modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) a clinical marker of disease. Our data indicate that inhibitors targeting IL-13 and CCL2 may be effective treatments for patients exhibiting the inflammatory gene signature.

Materials and Methods

Mice

BALB/c, B10.D2, BALB/c Rag2−/−, and BALB/c Il4ra−/−14 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Joan Stein-Streilein (Schepens Eye Research Institute, Boston, MA) provided BALB/c Il13−/− mice.15 All mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility at the Harvard School of Public Health, and studies were performed according to institutional and NIH guidelines. The drinking water of mice deficient for Rag2 was supplemented with co-trimoxazole (Sulfatrim).

sclGVHD Model

The sclGVHD model was established as described previously.5 Briefly, 20 to 40 million BALB/c (syngeneic) or B10.D2 (allogeneic) red-blood-cell-free splenocytes were transferred via tail-vein injection into host mice. Mice were scored biweekly by a blinded observer (M.B.G.) as follows: No evidence of disease (score = 0), fur ruffling or hunched posture (score = 1), alopecia <25% of body surface area (score = 2), alopecia >25% of body surface area (score = 3), and death or a veterinary order to euthanize (score = 4). One half a point was added for periorbital swelling. A mouse was deemed affected by sclGVHD for a score of ≥2. In the event of a death, the last observed clinical score was carried forward. An observer experienced in SSc pathology (R.L.) scored two H&E-stained back skin tissue samples per mouse for four parameters (fibrosis, inflammation, lipoatrophy, and epidermal hyperplasia), using a semiquantitative scale from 0 to 3. Values were averaged for each parameter and were summed to derive a combined pathological score. Centocor-Janssen Biotech (Horsham, PA) provided blocking antibodies to CCL2 and CCL12 and an isotype control.16

Microarray Procedures, Data Processing, and Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and further purified with RNeasy mini columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). One hundred to 300 ng of sample or reference total RNA [universal mouse reference; Stratagene (La Jolla, CA)] was amplified and labeled with Cy3 or Cy5 using Agilent low-input linear amplification protocols (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Microarrays were hybridized to 44K mouse whole-genome DNA microarrays (Agilent Technologies) in a common reference design and scanned using a dual-laser GenePix 4000B scanner (Axon Instruments; Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Pixel intensities were quantified using GenePix Pro 5.1 software (Axon Instruments). All microarrays were inspected for defects or artifacts, and spots of poor quality were excluded. Data were uploaded to the UNC Microarray Database (UMD; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) and downloaded as lowess-normalized log2 Cy5/Cy3 ratios. Only probes that passed a filter of intensity/background ratio ≥ 1.5 in one or both channels and for which ≥80% of the data were of sufficient quality were used. All data were multiplied by −1 thereby converting the log2 Cy5/Cy3 ratios to log2 Cy3/Cy5 ratios for all analyses. For interspecies comparisons, mouse genes were matched to human orthologs using the Mouse Genome Informatics database maintained by the Jackson Laboratory (available at http://www.informatics.jax.org).17 All human and mouse data sets were median centered and clustered using the Cluster 3.0 algorithm of Eisen et al,18 and heat maps were generated using TreeView version 1.0.13 according to the authors' recommendations.18 The Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) method19 was implemented to identify genes significantly differentially expressed in both human and sclGVHD data sets. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated and plotted in Microsoft Excel 2007. Pathway analysis was conducted with DAVID20 and Genomica software.21

Microarray Data Access

The 75 microarray human scleroderma data set, previously described,4 is publicly available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information GEO site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; accession GSE9285). All expression data sets generated for the present study are likewise available at the NCBI GEO site [human IL-13–responsive signature (GSE24403), IL-4–responsive signature (GSE24409), and sclGVHD microarray data sets (GSE17914)].

Generation of IL-13 and IL-4 Gene Expression Signatures in Dermal Fibroblasts

Adult dermal fibroblasts (Cambrex BioScience, Walkersville, MD) were cultured for 48 hours, brought to quiescence in 0.1% fetal bovine serum, and treated with 50 nmol/L of recombinant human IL-13 or IL-4 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Total RNA was collected at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24-hour time points, amplified, labeled, and hybridized to whole-genome microarrays in a common reference design. Eight microarrays were hybridized for each time course. For each time course, data were normalized by T0, transforming the data to the average of the triplicate baseline readings at 0 hours of either IL-13 or IL-4 exposure. Responsive genes for each cytokine were selected using a threshold cutoff of a ≥twofold change from T0.

Explant Cultures

At 2 weeks after splenocyte transfer, back skin was harvested, shaved, and cultured overnight in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. Supernatants were analyzed via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Cell Isolation and Sorting

At 2 or 3 weeks after cell transfer, back skin was isolated and digested with collagenase type XI (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 2 hours at 37°C. A single-cell suspension of liberated cells was stained with the antibodies indicated in the respective figures and sorted on a FACSAria II flow-activated cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). All antibodies were from BD Biosciences, except that anti-Foxp3 and anti-CD115 were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

T-Cell Restimulation Assays

CD4+ T cells were isolated from subcutaneous lymph nodes of sclGVHD mice via negative selection for CD11c+ and B220+ cells, followed by CD4+ selection using magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Alternatively, CD4+ T cells were FACS-sorted from lesional skin. Cells were plated in 96-well plates precoated with 2 mg/mL anti-CD3. Supernatants were harvested 12 hours later and analyzed for cytokine secretion by ELISA. Alternatively, cells were stained for Foxp3 using a Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience).

Collection of Normal Human and SSc Skin Samples

After informed consent had been given regarding the nature and possible consequences of the study, two 3-mm punch biopsies were obtained from SSc patients or normal control subjects. One biopsy was placed in formalin for histology and the other in RNAlater stabilization reagent (Qiagen) for RNA purification. Age, sex, and disease duration were noted at the time of the biopsy, and mRSS was obtained.22

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

For mRNA expression studies, cDNA was synthesized [Stratagene or Applied Biosciences (Foster City, CA)] and real-time PCR was performed using Brilliant II SYBR Green master mix (Stratagene) on a Mx3005P quantitative PCR system (Stratagene). CT values for duplicate samples were averaged, and the amount of mRNA relative to a housekeeping gene was calculated with the ΔCT method. Primer sequences are given in Table 1.23–25

Table 1.

qRT-PCR Primers Targeting Murine and Human Genes

| Primer set | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murine | |||

| Hprt | 5′-GTTAAGCAGTACAGCCCCAAA-3′ | 5′-AGGGCATATCCAACAACAAACTT-3′ | ⁎ |

| Hmbs | 5′-ATGAGGGTGATTCGAGTGGG-3′ | 5′-CAAACTGTATGCCAGGGTACAA-3′ | ⁎ |

| Il13 | 5′-CCTGGCTCTTGCTTGCCTT-3′ | 5′-GGTCTTGTGTGATGTTGCTCA-3′ | ⁎ |

| Cox2 | 5′-CTCCCTGAAGCCGTACACAT-3′ | 5′-ATGGTGCTCCAAGCTCTACC-3′ | Bachar et al24 |

| Sprr2a | 5′-GCCTTGTCGTCCTGTCATGT-3′ | 5′-GGCATTGCTCATAGCACACTAC-3′ | ⁎ |

| Nos2 | 5′-GTTCTCAGCCCAACAATACAAGA-3′ | 5′-GTGGACGGGTCGATGTCAC-3′ | ⁎ |

| Arg1 | 5′-ATGGAAGAGACCTTCAGCTAC-3′ | 5′-GCTGTCTTCCCAAGAGTTGGG-3′ | Brys et al25 |

| Chi3l3 (Ym1) | 5′-GGGCATACCTTTATCCTGAG-3′ | 5′-CCACTGAAGTCATCCATGTC-3′ | Brys et al25 |

| Ccl2 | 5′-TTAAAAACCTGGATCGGAACCAA-3′ | 5′-GCATTAGCTTCAGATTTACGGGT-3′ | ⁎ |

| Infg | 5′-GAACTGGCAAAAGGATGGTGA-3′ | 5′-TGTGGGTTGTTGACCTCAAAC-3′ | ⁎ |

| Il13ra1 | 5′-ATGCTGGGAAAATTAGGCCATC-3′ | 5′-ATTCTGGCATTTGTCCTCTTCAA-3′ | ⁎ |

| Il4Ra | 5′-TCTGCATCCCGTTGTTTTGC-3′ | 5′-GCACCTGTGCATCCTGAATG-3′ | ⁎ |

| Ccl12 | 5′-GGGAAGCTGTGATCTTCAGG-3′ | 5′-GGGAACTTCAGGGGGAAATA-3′ | † |

| Human | |||

| ADAM8 | 5′-GAGGGTGAGCTACGTCCTTG-3′ | 5′-CAGCCGTATAGGTCTCTGTGTA-3′ | ⁎ |

| GAPDH | 5′-ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG-3′ | 5′-GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA-3′ | ⁎ |

| HPRT | 5′-TGGACAGGACTGAACGTCTTG-3′ | 5′-CCAGCAGGTCAGCAAAGAATTTA-3′ | ⁎ |

| IL13RA1 | 5′-ACTCCTGCTTTACCTAAAAAGGC-3′ | 5′-GCACTACAGAGTCGGTTTCCT-3′ | ⁎ |

| IL4RA | 5′-TCATGGATGACGTGGTCAGT-3′ | 5′-CAGGTCAGCAGCAGAGTGTC-3′ | † |

| CCL2 | 5′-CAGCCAGATGCAATCAATGCC-3′ | 5′-TGGAATCCTGAACCCACTTCT-3′ | ⁎ |

| CXCL10 | 5′-GTGGCATTCAAGGAGTACCTC-3′ | 5′-GCCTTCGATTCTGGATTCAGACA-3′ | ⁎ |

| CCL4 | 5′-AAGCTCTGCGTGACTGTCCT-3′ | 5′-GCTTGCTTCTTTTGGTTTGG-3′ | † |

| TIMP1 | 5′-CTTCTGCAATTCCGACCTCGT-3′ | 5′-CCCTAAGGCTTGGAACCCTTT-3′ | ⁎ |

| COX2 | 5′-CTGGCGCTCAGCCATACAG-3′ | 5′-CCGGGTACAATCGCACTTATACT-3′ | ⁎ |

| ARG1 | 5′-CGCCAAGTCCAGAACCATAGG-3′ | 5′-TCTCAATACTGTAGGGCCTTCTT-3′ | ⁎ |

From the Center for Comparative and Integrative Biology Primer Bank, Harvard Medical School (Wang et al23). PrimerBank IDs: Hprt, 7305155a2; Hmbs, 387506a3; Il13, 6680403a1; Sprr2a, 31560549a1; Nos2, 6754872a1; Ccl2, 6755430a1; Ifng, 33468859a2; Il13ra1, 18204468a1; IL4Ra, 26329959a1; ADAM8, 4557253a1; GAPDH, 7669492a1; HPRT, 4504483a2; IL13RA1, 4504647a1; CCL2, 4506841a1; CXCL10, 4504701a1; TIMP1, 4507509a1; COX2, 24430028a2; and ARG1, 30582321a1. PrimerBank is available at http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank.

Designed with the online Primer 3 tool (available at http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3).

Immunohistochemistry

After heat-based antigen retrieval, sections were stained with mouse anti-human IL-13 (1:100; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or CD68 (1:50; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Primary antibodies were detected with donkey anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), followed by tyramide signal amplification (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (1:100), and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Statistical Analyses

Unpaired Student's t-tests were used for continuous variables, Mann-Whitney tests for categorical values, and log rank (Mantel-Cox) tests for Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Statistical and linear regression analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Error bars indicate standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Murine sclGVHD Approximates the Inflammatory Subset of SSc

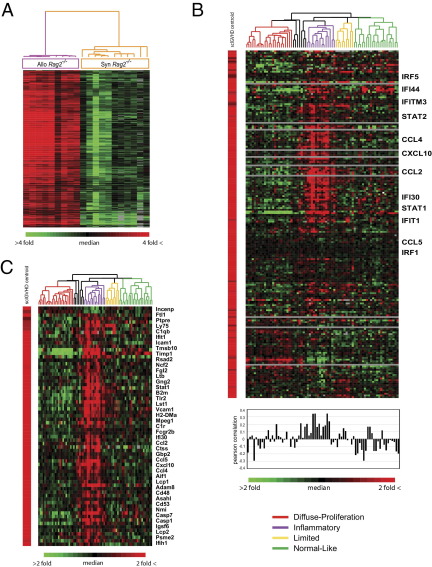

A murine sclGVHD-associated gene expression signature was identified by implementing SAM analysis19 to select genes differentially expressed in the skin of Rag2−/− mice that received either allogeneic (Allo Rag2−/−) or syngeneic (Syn Rag2−/−) splenocyte transfers 2 or 5 weeks earlier. Relative changes in gene expression between sclGVHD mice (Allo Rag2−/−) and controls (Syn Rag2−/−) were greatest at 2 weeks, whereas few differences were found between the 2-week and 5-week sclGVHD samples (J.L. Sargent, unpublished data). The overlap of two independent comparisons of sclGVHD and control mice 2 weeks after splenocyte transfer contained 371 probes, representing 291 unique annotated genes, all of which were up-regulated in diseased mice. These 291 genes were defined as the core sclGVHD signature (Figure 1A; see also Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Assessment of the core sclGVHD signature genes using DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery)20 showed an enrichment for gene GO terms (http://www.geneontology.org) associated with immune responses, antigen presentation and protein degradation (see Supplemental Table S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 1.

A sclGVHD-associated gene expression signature is enriched in the inflammatory subset of human SSc. A: Genes differentially expressed in skin of sclGVHD mice and syngeneic controls at 2 weeks were identified in two independent cohorts of mice. Allo Rag2−/−, n = 9 mice; Syn Rag2−/−, n = 8 mice + 3 technical replicates. B: The 291 genes in the sclGVHD signature were mapped to 204 human orthologs and expression was extracted from a data set of gene expression in SSc skin (Milano et al4). Samples are ordered by intrinsic SSc subsets (Milano et al4), and the genes are organized by hierarchical clustering. The centroid average of the sclGVHD-associated gene expression signature is shown on the left. Pearson's correlation coefficients between the sclGVHD centroid and each of the SSc samples are plotted below the heat map. The color of the dendrogram indicates statistically significant intrinsic patient subsets. Those patient samples with black dendrograms did not show an association with a specific group (grouped according to Milano et al4). Representative inflammatory subset genes are shown. C: Heat map of the core sclGVHD:inflammatory SSc genes. 1055 differentially expressed genes were identified in the inflammatory subset and compared with 204 human orthologs of the sclGVHD-associated gene signature in B, which resulted in 69 core genes differentially expressed in both diseases. Representative genes are shown.

To determine whether the changes in gene expression found in sclGVHD skin reflect those observed in SSc, expression of the core sclGVHD signature was assessed in the SSc intrinsic subsets described previously.4 Of the 291 sclGVHD signature genes (Figure 1A), 204 were matched to human orthologs using the Mouse Genome Informatics Database.17 Of these, 194 genes were present with data of sufficient quality in the human SSc skin data set. Samples were organized by intrinsic subset classification,4 and genes were clustered by their expression in SSc skin biopsies. This analysis revealed that the sclGVHD expression signature is closely reflected in the inflammatory subset of SSc (Figure 1B4). Mean Pearson's correlation coefficients with the sclGVHD expression signature were 0.144 ± 0.140 for the inflammatory subset, compared with −0.016 ± 0.103 for diffuse-proliferation, 0.022 ± 0.080 for limited, and −0.077 ± 0.123 for normal-like subsets.

Because sclGVHD demonstrates a gene expression pattern similar to the inflammatory SSc subset (Figure 1B), we reasoned that genes coexpressed in the model and in patient biopsies would be important for disease pathogenesis. SAM analysis19 was applied to the SSc data set of Milano et al4 to identify genes in the inflammatory subset differentially expressed relative to other subsets. The resulting 1055 genes obtained with a false discovery rate of <0.05% (see Supplemental Table S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org)4 were compared with the 194 human orthologs of the sclGVHD signature to identify genes in common between the two. Sixty-nine genes were present in both data sets, thereby defining the shared set of sclGVHD:inflammatory-SSc genes (Figure 1C; see also Supplemental Table S4 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org25). Of these, 67 showed a coordinate increase in expression in both sclGVHD and in the inflammatory SSc subset.

Murine sclGVHD and the Inflammatory Subset of SSc Display IL-13 Pathway Activation

Because the sclGVHD model approximates the inflammatory subset of SSc (Figure 1, B and C), we sought to identify common deregulated pathways. IL-13 is a 10-kDa cytokine produced by adaptive and innate immune cells and has been linked to fibroinflammatory diseases.27 Genetic and observational studies have associated IL-13 with SSc pathogenesis.28–31 To examine the contribution of this cytokine to gene expression in SSc, an IL-13–induced gene signature was derived in human dermal fibroblasts. Gene expression data for 491 probes induced or repressed twofold or more from baseline in fibroblasts treated with IL-13 (see Supplemental Table S5 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) were extracted from the SSc skin biopsy microarray data set.4 This analysis showed that the human IL-13–gene signature is enriched in the inflammatory subset of SSc but not in the diffuse-proliferation subset, and only weakly in the limited and normal-like groups (Figure 2A). The average Pearson's correlation coefficient for the IL-13–responsive signature in the inflammatory subset was 0.114 ± 0.047, compared with −0.113 ± 0.073 for the diffuse-proliferation group, 0.040 ± 0.072 for the limited group, and 0.020 ± 0.098 for the normal-like group. Thus, IL-13–activated gene expression is enriched in a subset of SSc patients that includes those with diffuse, limited, and localized disease.4

Figure 2.

The IL-13 pathway is activated in SSc and sclGVHD skin. A: Gene expression data for the 491 IL-13–responsive genes identified in human dermal fibroblasts were extracted from the SSc skin data of Milano et al.4 SSc skin biopsy samples are ordered by intrinsic subset and genes are organized by hierarchical clustering. The centroid average of the IL-13–responsive gene signature at maximal induction (12 and 24 hours) is shown to the left of the heat map. Pearson's correlation coefficients between the centroid and individual patient sample are plotted below each array. B: Expression data for the 734 genes reported by Fulkerson et al26 as IL-13–inducible genes in mouse lung were extracted from the sclGVHD microarray data set obtained 2 weeks and 5 weeks after splenocyte transfer (n = 4 per group). Genes and arrays were organized by hierarchical clustering. The relative expression of IL-13–inducible genes (centroid) in lungs is shown to the left of the heat map. C: Representative IL-13 IHC on skin biopsies obtained from an SSc patient and a normal control subject. Arrowheads indicate IL-13+ cells. Original magnification, ×400. D: Blinded quantification of the number of IHC IL-13+ cells per high-power field (×600) in skin biopsies from SSc patients and normal control subjects. SSc, n = 18; control, n = 6; P = 0.0037. E: IL-13 ELISA on the tissue culture supernatants of skin explants from BALB/c Rag2−/− mice that received either syngeneic BALB/c (n = 3) or allogeneic B10.D2 (n = 3) splenocytes 2 weeks earlier (P = 0.002).

To assess activation of the IL-13 pathway in sclGVHD skin, a previously published IL-13–induced gene signature from a murine model of pulmonary fibrosis was used. Fulkerson et al26 reported 734 genes with a ≥twofold increase in expression in lungs of IL-13 transgenic animals. These genes were extracted from skin expression data sets obtained from sclGVHD mice or controls 2 and 5 weeks after splenocyte transfer and were hierarchically clustered in the gene and array dimensions (Figure 2B). The murine sclGVHD samples could be clearly distinguished from syngeneic controls, based on their expression of IL-13–responsive genes (Figure 2B). The greatest Pearson's correlation coefficients were observed at 2 weeks, with an average of 0.1164 ± 0.03333 for the allogeneic mice (versus −0.08259 ± 0.02544 for the syngeneic controls), compared with 0.03451 ± 0.06087 for the allogeneic mice at 5 weeks (versus −0.09984 ± 0.06994 for the syngeneic controls).

Last, we confirmed IL-13 protein expression in SSc patients and in the sclGVHD model. In an independent set of SSc skin biopsies (see Supplemental Table S6 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), a significant increase in IL-13+ cells was observed by IHC, compared with control biopsies (Figure 2, C and D). Explant cultures of sclGVHD skin confirmed active secretion of IL-13 in lesional skin 2 weeks after induction of disease (Figure 2E). These data indicate that IL-13 is produced at the major site of pathology in both the inflammatory subset of SSc and the sclGVHD model, initiating changes in gene expression that likely contribute to disease pathogenesis.

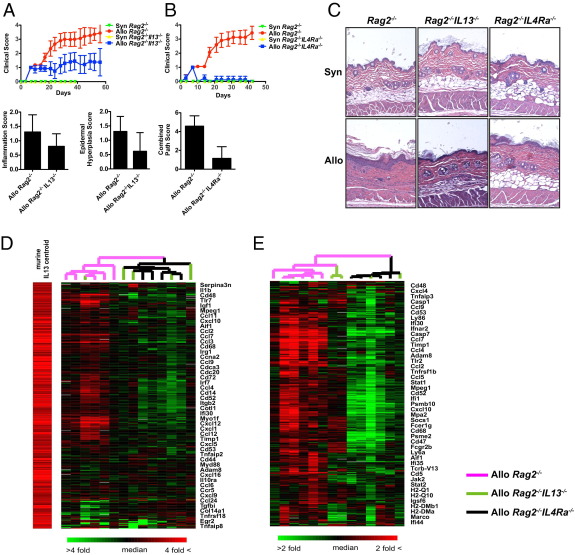

Host-Derived IL-13 Contributes to the Pathogenesis of sclGVHD

Both innate and adaptive immune cells produce pathologically relevant quantities of IL-13.27,32 To test the importance of IL-13 derived from host innate immune cells, Rag2−/−Il13−/− hosts were generated and found to be partially protected from the clinical and histological evidence of sclGVHD (Figure 3, A and C; see also Supplemental Figure S1, A, C, and D, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Although histological evidence of inflammation and epidermal hyperplasia was attenuated in IL-13–deficient hosts, subcutaneous fat loss appeared to be independent of host IL-13 status (Figure 3, A and C; see also Supplemental Figure S1A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Dermal fibrosis and combined total pathology score showed a nonsignificant trend toward reduction in Rag2−/−Il13−/− hosts (see Supplemental Figure S1A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Taken together, these data indicate that IL-13 derived from host innate immune cells contributes to the pathogenesis of sclGVHD.

Figure 3.

Host IL-13 and IL-4Rα are required for sclGVHD. A: Blinded biweekly clinical scoring (mean ± 95% CI) and pathological scoring for inflammation (P = 0.0291) or epidermal hyperplasia (P = 0.008) in BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/− hosts receiving either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes. Sample size for clinical score: Syn Rag2−/−, n = 4; Syn Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 2; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 25; Allo Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 20. Sample size for pathological score: Allo Rag2−/−, n = 13; Allo Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 13. B: Blinded biweekly clinical scoring (mean ± 95% CI) and combined pathological scoring (P < 0.0001) in BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts receiving either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes. Sample size for clinical score: Syn Rag2−/−, n = 6; Syn Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 3; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 16; Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 17. Sample size for pathological score: Allo Rag2−/−, n = 13; Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 17. C: Representative histological sections of back skin 6 weeks after the indicated hosts received either syngeneic or allogeneic splenocytes. Original magnification, ×100. Expression of IL-13–inducible genes26 (D) and the 371 core murine sclGVHD-associated genes (E) (Figure 1A) in expression data sets from BALB/c Rag2−/− (n = 5), BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/− (n = 4), and BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− (n = 4) hosts injected with allogeneic splenocytes 2 weeks earlier. The expression values of IL-13–inducible genes (centroid) in lungs (according to Fulkerson et al26) are shown to the left of the heat map in D. Genes and arrays are organized by hierarchical clustering and representative genes are shown. In E, an additional technical replicate for a BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/− is included.

The IL-13/IL-4 Receptor Complex Is Essential for the Development of sclGVHD

To determine whether the relevant cellular target of IL-13 signaling is host-derived or graft-derived, hosts lacking IL-4Rα, an essential component of the type II IL-13/IL-4 receptor complex, were tested in the sclGVHD model.33 In contrast to IL-13–deficient hosts, Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts were completely protected from sclGVHD (Figure 3, B and C; see also Supplemental Figure S1, B, C, and E, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Protection from disease conferred by either IL-4Rα or IL-13 deficiency was not due to a failure of cell engraftment, because hosts lacking these genes that received allogeneic splenocytes displayed early signs of disease, including ruffled fur and decreased activity (equaling a clinical score of 1) (Figure 3, A and B), as well as splenomegaly (see Supplemental Figure S1F at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These studies demonstrate that IL-13 signaling in the host is critical for the pathogenesis of sclGVHD.

To further define the contribution of IL-13/IL-4Rα signaling in sclGVHD, the IL-13 and the sclGVHD gene expression signatures were assessed in Rag2−/−, Rag2−/−Il13−/−, and Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts. As expected, 2 weeks after splenocyte transfer the expression of murine IL-13–inducible genes was highly expressed in Rag2−/− hosts and significantly attenuated in Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts (Figure 3D). Similarly, although Rag2−/− hosts demonstrated induction of the sclGVHD signature reported in Figure 1A, this expression profile was ablated in Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts (Figure 3E). In contrast to IL-4Rα–deficient hosts, clustering of the arrays from Rag2−/− Il13−/− sclGVHD mice was dispersed through samples from both Rag2−/− and Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts (Figure 3, D and E), likely a reflection of graft-derived IL-13 in these hosts and their partial protection from disease. Loss of the IL-13 signature in IL-4Rα–deficient hosts validates this signature and its relevance as a probe for IL-13 pathway activation.

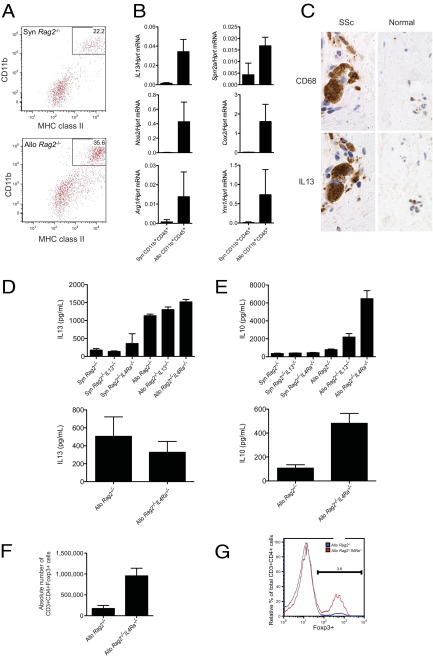

IL-13 Is Derived from Dermal Macrophages and T Cells in sclGVHD

To characterize the cellular source of IL-13 in sclGVHD, a single-cell suspension was prepared from the skin 2 weeks after allogeneic or syngeneic cell transfer and analyzed by flow cytometry for innate and adaptive immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, and T-lymphocytes (Figure 4A; see also Supplemental Figures S2, A–D, and S3, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). IL13 mRNA was dramatically up-regulated in a CD45+CD11b+MHC class II+CD115+CD11c− macrophage population (Figure 4, A and B; see also Supplemental Figure S2A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Although this population was present in mice that received either allogeneic or syngeneic transplants, its frequency was increased in allogeneic recipients (Figure 4A). Similarly, mice demonstrating alopecia at 3 weeks displayed higher levels of these cells, relative to those that failed to develop clinical disease (see Supplemental Figure S2B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In contrast, despite protection from sclGVHD, these cells could be identified in the skin of Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts receiving an allogeneic transplant (see Supplemental Figure S2C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In allogeneic Rag2−/− recipients, this population expressed markers of IL-13 activation (Sprr2a),34 both M1 (Nos2, Cox2) and M2 (Arg1, Ym1) macrophages (Figure 4B),35 and increased levels of Il4ra expression (see Supplemental Figure S2D at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts, this population had undetectable levels of Il4ra expression, indicating that this macrophage population is entirely host-derived (see Supplemental Figure S2D at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). To determine the cellular source of IL-13 in SSc skin, we costained serial sections for IL-13 and the macrophage marker CD68 (Figure 4C). IHC signals for IL-13 and CD68 colocalized to cells with similar morphology within the same inflammatory infiltrates; however, it was difficult to reliably distinguish identical cells on serial sections (Figure 4C). These data suggest that macrophages are a source of IL-13 in SSc skin.

Figure 4.

Characterization of the cellular immunology of sclGVHD. A: Flow cytometric analysis for CD11b and MHC class II on CD45+ cells liberated from the back skin of BALB/c Rag2−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier. B: Quantitative PCR analysis for the expression of the indicated genes from CD45+CD11b+ cells sorted from the skin of control or sclGVHD mice. Each sample represents a pooled value reflecting all Syn Rag2−/− and Allo Rag2−/− mice in an individual experiment. The number of experiments pooled to generate these data and the P values were as follows: IL13, n = 5 (Syn) and n = 6 (Allo), P = 0.0003; Sprr2a, n = 3 (Syn) and n = 4 (Allo), P = 0.012; Nos2, n = 6 (Syn) and n = 4 (Allo), P = 0.0042; Cox2, n = 3 (Syn) and n = 3 (Allo), P = 0.0368; Arg1, n = 5 (Syn) and n = 5 (Allo), P = 0.054; and Ym1, n = 6 (Syn) and n = 5 (Allo), P = 0.022. C: Representative CD68 and IL-13 IHC on skin biopsies obtained from an SSc patient and a normal control subject. Original magnification, ×400. ELISA for IL-13 (D) and IL-10 (E) on tissue culture supernatants of restimulated CD45+CD4+ T cells. CD45+CD4+ T cells were isolated from lymph nodes (upper panels, n = 3 per group) or skin (lower panels) of BALB/c Rag2−/−, BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/− (lymph nodes only), or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier. IL13: n = 3 (lymph nodes) and n = 4 (skin). IL10: n = 3 per group. The lack of a syngeneic control in the lower panels reflects the paucity of T cells infiltrating the skin of syngeneic controls (see Supplemental Figure S3A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Absolute numbers of CD3+CD4+Foxp3+ (P < 0.002) (F) and relative percentage of Foxp3 expression (G) within the CD3+CD4+ gate of cells isolated from the cutaneous lymph nodes of BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier (n = 4 per group).

T-cell infiltrates were also present in skin of Rag2−/− and Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− host mice after transfer of allogeneic but not syngeneic splenocytes (see Supplemental Figure S3A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), suggesting that host IL-4Rα signaling is not required for recruitment of T cells to the skin. We additionally examined the influence of host IL-13 or IL-4Rα on cytokine production by graft T cells by restimulating purified dermal or draining lymph node CD4+ T cells ex vivo. Restimulation elicited robust production of IL-13 by both dermal and subcutaneous lymph node CD4+ T cells isolated from allogeneic recipients (Figure 4D). This response was unaltered in CD4+ T cells from hosts deficient in either IL-13 or IL-4Rα (Figure 4D). This finding suggests that the increased protection from disease in IL-4Rα–deficient versus IL-13–deficient hosts may be due to production of IL-13 from graft-derived CD4+ T cells. Because a previous report suggested that mast cells drive fibrosis in GVHD,36 CD117+ FcεR+ mast cells were sorted from the skin of sclGVHD mice; however, these cells were not found to express appreciable levels of IL13 mRNA, compared with sorted dermal macrophages (see Supplemental Figure S3B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Taken together, our data indicate that IL-13 in sclGVHD skin is derived from host macrophages and graft T cells.

Host IL-4Rα Suppresses Regulatory Mechanisms in sclGVHD

Additional analysis of CD4+ T cells from draining lymph nodes demonstrated significant production of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-17 in cells isolated from Rag2−/− mice receiving allogeneic but not syngeneic splenocytes (see Supplemental Figure S3C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). CD4+ T cells from either IL-13–deficient or IL-4Rα–deficient hosts showed unaltered production of IFN-γ and IL-17 (see Supplemental Figure S3C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). However, CD4+ T cells isolated from IL-4Rα–deficient hosts did display a modest decrease in IL-2 production (see Supplemental Figure S3C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In contrast, a robust induction of IL-10 was observed in CD4+ T cells from either the skin or lymph nodes of IL-4Rα–deficient hosts (Figure 4E). CD4+ T cells from the lymph nodes of IL-13–deficient hosts displayed an intermediate phenotype for IL-10 production (Figure 4E). Furthermore, there was a large increase in regulatory T cells in the subcutaneous lymph nodes of Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, compared with Rag2−/− hosts receiving an allogeneic transplant (Figure 4, F and G; see also Supplemental Figure S3, D and E, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These data suggest that absence of IL-4Rα signaling in the host suppresses sclGVHD by activating anti-inflammatory T-cell mechanisms, including IL-10 production and regulatory T-cell differentiation.

Functional Redundancy of IL-13 and IL-4 Pathways in SSc Patients

Taken together, our results suggest that IL-13 derived from host and graft sources promotes sclGVHD through host IL-4Rα. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that defective IL-4 signaling contributes to the additional protection observed in IL-4Rα–deficient hosts, compared with those lacking IL-13 (Figure 3, A–E). To test for functional overlap of the IL-4/IL-13 pathways in SSc patients, we derived an IL-4-induced gene signature in human dermal fibroblasts as described under Materials and Methods (see Supplemental Table S7 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). When expression of the IL-4–responsive signature was examined in the SSc patient skin gene expression data set, this signature was also enriched in the inflammatory subset (see Supplemental Figure S4A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).4 Accordingly, this IL-4–responsive signature had an overlap of ∼60% with that of the IL-13–induced signature (see Supplemental Figure S4B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).21 Genomica21 pathway analysis demonstrated multiple shared pathways in the IL-13– and IL-4–responsive gene signatures. Biological processes, including inflammatory responses and cytokine activity, were coordinately increased, whereas processes associated with cell proliferation were coordinately decreased (see Supplemental Figure S4B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).21 These results suggest that IL-4 and IL-13 can act in a functionally redundant manner in SSc patients.

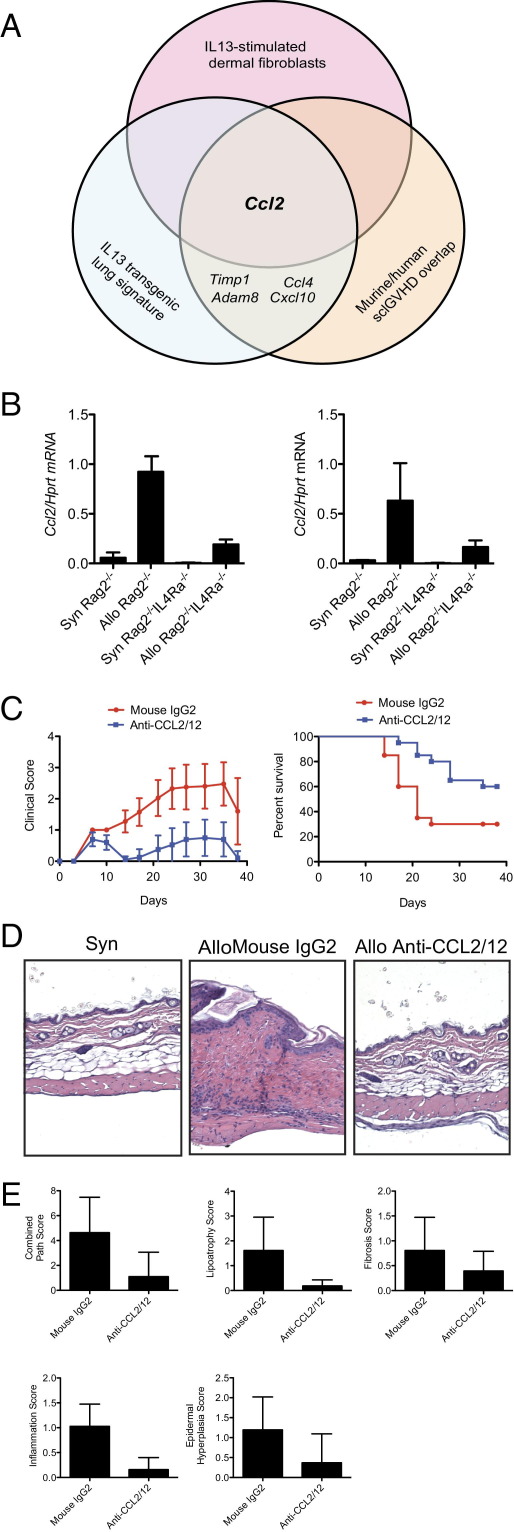

CCL2 Is Up-Regulated in IL-13–Stimulated Human Dermal Fibroblasts and Skin Biopsies of Both Inflammatory SSc Patients and sclGVHD Mice

Our finding that IL-4Rα is critical for sclGVHD and that an IL-13 gene expression signature is increased in the inflammatory subset of SSc suggests that exploration of this pathway could yield therapeutic targets. We reasoned that genes most central to disease pathogenesis would be found among the overlap of genes up-regulated within the core sclGVHD:inflammatory signature (Figure 1C), IL-13–treated human dermal fibroblasts, and the inflammatory subset of SSc (Figure 2A), as well as the lungs of IL-13–transgenic animals.26 The chemokine gene Ccl2 emerged as the sole gene present in all three of these data sets (Figure 5A). Expression analysis showed that both CD45+CD11b+MHC class II+ macrophages and nonhematopoietic CD45− cells from the skin of sclGVHD mice expressed Ccl2, indicating that this chemokine is derived from multiple cellular sources (Figure 5B). Consistent with Ccl2 being an IL-13 target gene, its expression was statistically reduced in the CD45+ subsets from IL-4Rα–deficient hosts, with a similar trend in the CD45− population (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

The overlap of multiple bioinformatics and experimental approaches identifies CCL2 as a mediator of sclGVHD downstream of IL-13. A: Schematic of how transcripts related to the IL-13 pathway in SSc and sclGVHD were identified from overlapping of the three indicated data sets. Complete lists of genes are given in Supplemental Tables S4, S5, and S8 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). B: Expression of Ccl2 by quantitative RT-PCR in CD45+CD11b+MHC class II+ (left panel) and CD45− (right panel) cells sorted from the skin of BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier (n = 3 per group). P = 0.001, Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− (CD45+CD11b+MHC class II+; left panel); P = 0.10, Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− (CD45−; right panel). C: Clinical scores versus time (mean ± 95% CI) and Kaplan-Meier survival curve (P < 0.02) for BALB/c Rag2−/− hosts that received allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes and randomized on day 0 to biweekly injections of either blocking antibodies to CCL2 (20 mg/kg) and CCL12 (10 mg/kg) (n = 20), or an isotype control antibody (30 mg/kg) (n = 20). D: Representative H&E-stained sections from the back skin of BALB/c Rag2−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 6 weeks earlier and treated with the indicated antibodies. Original magnification, ×100. E: Pathological scores for BALB/c Rag2−/− hosts that received allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes and treatment with either blocking antibodies to CCL2/CCL12 (n = 19) or an isotype control antibody (n = 18). P = 0.0003, combined pathological score; P = 0.0007, lipoatrophy; P = 0.0524, fibrosis; P = 0.0008, inflammation; and P = 0.0021, epidermal hypertrophy.

Blockade of CCL2 and CCL12 Prevents sclGVHD

Neutralizing antibodies were used to test the functional significance of CCL2 in sclGVHD. Because mice have a functionally redundant CCL2 ortholog, CCL12, we cotreated mice with blocking antibodies to both chemokines.16 Similar to host mice lacking IL-4Rα, sclGVHD mice treated with blocking antibodies to CCL2/12 developed early signs of disease, including hair ruffling and inactivity, but were almost completely protected from clinical and pathological disease manifestations (Figure 5, C, D, and E; see also Supplemental Figure S5, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These data indicate that the CCL2 axis is critical for the development of sclGVHD.

Expression of IL-13 Pathway Genes and CCL2 Correlate with mRSS

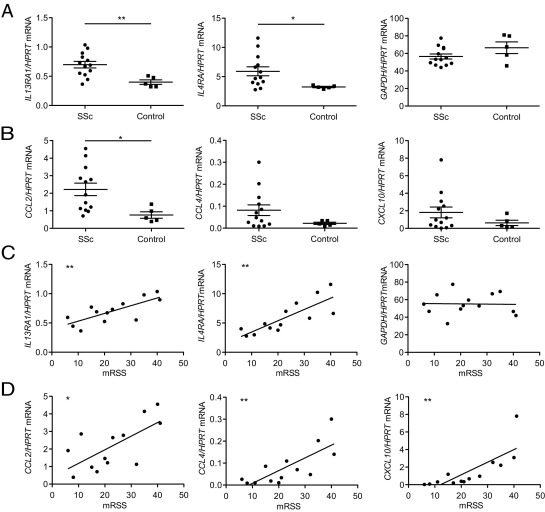

Because our data suggest that IL-13 plays a pathogenic role in SSc, we investigated whether the expression of genes associated with the IL-13 pathway was increased in skin biopsies from an independent cohort of early SSc patients with diffuse disease (average disease duration, 24.46 ± 10.6 months) versus normal control subjects (see Supplemental Table S9 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We then investigated whether expression levels of the genes identified correlated with mRSS. Transcripts encoding both IL-13 receptor components, IL-13RA1 and IL-4RA, were significantly increased in skin of SSc patients, and expression robustly correlated with mRSS (Figure 6, A and C). Moreover, expression levels of both transcripts tightly correlated with one another (see Supplemental Figure S6A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). As a control, GAPDH showed neither an increase in expression in SSc patients nor a correlation with either mRSS or IL-13RA1 (Figure 6, A and C; see also Supplemental Figure S6A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 6.

The expression of the IL-13 pathway genes correlates with mRSS in SSc patients. A and B: Quantitative RT-PCR analysis for the expression of the indicated genes in skin biopsies from diffuse SSc patients and normal control subjects. Data points represent individuals; error bars indicate means ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.007. C and D: Correlation of the expression of the indicated genes with mRSS obtained at the time of biopsy in SSc patients. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.007. R2 = 0.57, IL13RA1; 0.57; R2 = 0.66, IL4RA; R2 = 0.001, GAPDH; R2 = 0.45, CCL2; R2 = 0.59, CCL4; and R2 = 0.61, CXCL10.

To assess whether markers of IL-13 pathway activation correlate with mRSS, a subset of genes at the intersection of the IL-13–transgenic lung signature26 and the sclGVHD/human SSc overlap (Figure 1C) were evaluated. These included CCL2, CCL4, CXCL10, TIMP1, and ADAM8 (Figure 5A). Absolute levels of expression of CCL2 were higher in SSc patients and correlated significantly with mRSS and IL13RA1 (Figure 6, B and D; see also Supplemental Figure S6B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In contrast, although absolute expression levels of CCL4, CXCL10, TIMP1, and ADAM8 were not statistically higher in this cohort, those patients with increased levels of expression of these genes displayed higher mRSS (Figure 6, B and D; see also Supplemental Figure S6C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Our observation that expression of these markers correlates with mRSS without a statistically significant increase in absolute expression may reflect heterogeneity in our cohort, which likely contains patients with the inflammatory and diffuse-proliferation expression patterns.4 Other markers of immune system activation (ARG1, COX2) did not correlate with mRSS, suggesting specificity of our findings (see Supplemental Figure S6D at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Taken together, these data link expression of the IL-13 pathway with both the presence of SSc and a marker of skin disease severity. Furthermore, the finding that CCL2 expression correlates with both the diagnosis of SSc and mRSS validates our combined gene profiling and disease model approaches to identify therapeutic targets relevant to human disease.

Discussion

A major goal of modern medicine is the development of therapeutic regimens personalized to disease processes in individual patients to improve outcomes, reduce adverse events, and control costs. Although success has been obtained with more common diseases characterized by pathogenic genetic abnormalities, such as breast cancer and leukemia,37,38 autoimmune conditions have proven difficult, in large part because of a lack of insight into patient subsets and the animal models that might reflect them. This lack of accurate animal models precludes the identification of mechanism-based therapies for rare diseases such as SSc, a situation in which limited resources are best applied in high-yield trials that can be planned only with proper patient subsetting combined with strong preclinical data. Here, we address these challenges through a personalized translational medicine approach, combining the patient subsetting methods of personalized medicine with the use of translational animal models.

In particular, the sclGVHD model resembles a subset of SSc patients characterized by expression of inflammatory pathways. This subset represents 17% (3/17) and 36% (8/22) of diffuse disease patients in two published4,13 cohorts, as well as 28% (2/7) of patient s with limited disease and all (3/3) patients analyzed with localized scleroderma (morphea).4 In addition to the similarities at a global gene expression level, both sclGVHD mice and inflammatory SSc patients display IL-13 pathway activation. Confirming the molecular similarity between murine sclGVHD and inflammatory SSc patients validates the model as a platform to develop subset specific therapeutics. Indeed, our functional data indicate that the IL-13/IL-4Rα pathway is a high-yield target in this population. The enrichment of the IL-13 and IL-4 signatures in the limited SSc group of Milano et al4 suggests that blockade of these pathways may also be relevant for those with limited scleroderma. In contrast, the sclGVHD model does not appear to be an appropriate model for patients classified in the diffuse-proliferation or normal-like subsets. Other mouse models will need to be analyzed to identify the appropriate ones for these patients.

The data presented here are most relevant for patients with localized scleroderma (morphea), as well the estimated 28% of those with limited disease and the 17% to 36% of patients with diffuse SSc who map to the inflammatory subset. Identifying the inflammatory subset of patients by molecular methods, such as measuring gene expression in skin, would identify those patients likely to respond to therapeutic targeting of this pathway before clinical trials and thus would overcome a critical barrier to success.

Although a previous study examined gene expression changes in the skin of a variant of the sclGVHD model reported here,39 we present the first direct comparison with SSc and address how the sclGVHD expression signature relates to the heterogeneity among patients with this disease. Analysis of the core genes differentially expressed between the mouse and human tissues resulted in identification of 69 sclGVHD:inflammatory-SSc overlap genes, including robust chemokine and interferon signatures (see Supplemental Table S8 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Chemoattractants for activated T cells, basophils, neutrophils, and monocytes (CCL2, CCL5, CXCL10, CCL4) are highly represented in the overlap, suggesting that similar immune infiltrates contribute to both diseases. In addition, consistent with activation of IFN signaling, IFN-induced genes (eg, NMI, IFI30, IFI44, IFIH1, IFIT1), as well as a gene that transmits IFN signaling (STAT1), are also highly represented in this gene set. This latter observation supports previous work showing IFN-induced gene expression in SSc peripheral blood mononuclear cells and skin.4,40,41 Of the 69 sclGVHD:inflammatory-SSc core genes, nearly half (31/69, or approximately 45%) were also induced by IL-13 in the transgenic mouse lung model26 (see Supplemental Table S8 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).26 This constrained list of robustly expressed core sclGVHD:inflammatory-SSc overlap genes, of which many are IL-13–regulated, provides candidates for further therapeutic investigation.

In addition to demonstrating that the sclGVHD model and the inflammatory SSc subset4 display IL-13 pathway activation, functional evidence for the importance of this pathway is provided. Mice deficient in IL-13 or IL-4Rα displayed reduced sclGVHD incidence and severity, and our data indicate that IL-13 from host and graft-derived sources signals back to the host to drive disease. IL-13 production in the model was localized to two cell lineages: graft T cells and host macrophages that express both classical (M1) and alternative (M2) activation markers. In SSc skin biopsies, we identified an up-regulation of IL-13–expressing cells and localized expression to immune infiltrates containing CD68+ macrophages. Last, we found that expression levels of IL13RA1 and IL4RA, as well as IL-13 pathway genes such as CCL2 and CCL4, are increased in skin and correlate with mRSS, a marker of disease severity.

Previous studies support an important role for IL-13 and CCL2 in SSc. Others have demonstrated increased levels of IL-13 and IL-13–producing T cells in the blood of SSc patients.28,31,42 Moreover, polymorphisms in IL-13 are associated with incident SSc.30 Functional analysis of IL-13 in scleroderma models has been limited to bleomycin-induced fibrosis in skin43 and lung.44,45 However, the relevance of the bleomycin model to the human molecular SSc subsets is as of yet undefined. Thus, although these studies suggest an association between IL-13 and SSc, both functional evidence for the importance of IL-13 in a validated animal model of the disease and mechanistic insight into the sources and role of IL-13 have been lacking. Taking together these various considerations, the present study is the most comprehensive translational evaluation of the IL-13 pathway in SSc to date.

Although T cells are a well-established source of IL-13 in atopic and parasitic diseases,46 evidence for pathological production of IL-13 from macrophages is less well described. In a postinfectious model of chronic bronchopulmonary disease, IL-13–secreting macrophages were identified in later stages of disease, and IL-13 blockade prevented mucous cell metaplasia and airway hyperreactivity.32 This macrophage population demonstrated up-regulation of M2 markers. However, M1 markers were not reported, leaving open the possibility that these cells may also display a hybrid M1/M2 phenotype, as observed in the present study. An IL-13–secreting CD11b+IL-4Rα+ tumor-associated macrophage population expressing both M1 and M2 markers has been identified,47 similar to our population in sclGVHD skin. We speculate that macrophages programmed to secrete IL-13 cause tissue fibrosis across a variety of pathological conditions.

The finding that IL-4Rα–deficient hosts are protected from sclGVHD is in striking contrast to other disease models, such as schistosomiasis, in which deletion of Il4ra results in an exacerbated, lethal inflammatory response.48 Protection in the schistosomiasis model was linked to the ability of IL-4Rα to promote the differentiation of immunosuppressive M2 macrophages. Likewise, expression of IL-4Rα was important for the immunosuppressive capacity of the tumor-induced macrophages.47 In contrast, we observe that graft T cells isolated from the skin or draining lymph nodes of hosts deficient in IL-4Rα make more IL-10, a potent immunosuppressive cytokine. Moreover, a dramatic increase in regulatory T cells was observed in IL-4Rα–deficient hosts. Our studies support a model whereby the IL-13/IL-4Rα axis in the host is uncoupled from its typically described immunosuppressive role and instead subverts regulatory mechanisms in graft T cells, promoting inflammation and fibrosis.

We show that inhibition of CCL2 blocked sclGVHD and that, in SSc patients, expression levels of CCL2 in lesional skin strongly correlated with mRSS. Elevated levels of CCL2 have been previously documented in serum, skin, and fibroblasts from SSc patients, and CCL2 has been suggested as a disease progression biomarker.49–51 In lesional SSc skin, CCL2 is produced by numerous cell types, including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and mononuclear cells,49,50,52 consistent with our finding of CCL2 up-regulation in both CD45+ and CD45− populations in sclGVHD. In bleomycin models of skin and pulmonary fibrosis, genetic deficiency or pharmacological inhibition of CCL2, or its receptor, attenuates disease as well.16,53,54 The profibrotic activity of CCL2 has been linked to its ability to recruit monocytes, promote Th2 differentiation, and augment fibroblast responsiveness to TGFβ.54 Our findings complement these studies and establish a functional role for CCL2 in an animal model of SSc validated to represent a specific disease subset.

Our data indicate that SSc patients exhibiting an inflammatory gene expression signature, one that represents all patients with localized disease and a subset of patients with limited and diffuse SSc, can be modeled using murine sclGVHD and may be effectively treated with strategies targeting IL-13, IL-4Rα, or CCL2. Given that both biological and small-molecule antagonists targeting IL-1355 and CCL2 have been developed,56,57 we suggest that these agents be applied in a clinical trial of SSc patients with the inflammatory gene expression signature. Because patient stratification by degree of skin involvement is insufficient to identify the inflammatory subset, these patients should be identified by molecular means, such as gene expression profiling of skin biopsies.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the Scleroderma Research Foundation (M.L.W., A.O.A. and L.H.G.), a Hulda Irene Duggan Arthritis Investigator Award from the Arthritis Foundation (M.L.W.), a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (A.O.A.), by an NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant K08AR054859 (A.O.A), NIAMS grants U01AR055063 (R.L.) and R01AR051089 (R.L.), and by Scleroderma Foundation support (G.F.).

M.B.G. and J.L.S. contributed equally to the present work.

Disclosures: L.H.G. is a member of the board of directors of and holds equity in Bristol Myers Squibb and receives research funds from Merck & Co. M.L.W. is a scientific founder and holds a financial interest in Celdara Medical, LLC. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of NIAMS or the NIH.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.024.

Current address of J.L.S., NIH-NIAMS, Bethesda, Maryland; of L.H.G., Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

Contributor Information

Michael L. Whitfield, Email: michael.L.whitfield@dartmouth.edu.

Antonios O. Aliprantis, Email: aaliprantis@partners.org.

Supplementary data

Supplemental clinical and pathological data for Rag2−/−, Rag2−/−IL13−/−, and Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− sclGVHD mice. A: Histopathological scoring of back skin sections from BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 6 weeks earlier. Individual scores for fibrosis and lipoatrophy are shown, along with the cumulative pathological scoring. The other two components of the cumulative pathological score (inflammation and epidermal hyperplasia) are shown in Figure 3A. P values for Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−IL13−/− were as follows: P = 0.0063, lipoatrophy; P = 0.128, fibrosis; and P = 0.108, combined pathological score. Syn Rag2−/−, n = 4; Syn Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 2; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 13; Allo Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 13. B: Histopathological scoring of back skin sections from BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 6 weeks earlier. Individual scores are shown for components of the combined pathological score: lipoatrophy, epidermal hyperplasia, inflammation, and fibrosis. The cumulative pathological score is reported in Figure 3B. P values for Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− were as follows: P < 0.0004, fibrosis; P < 0.0001, inflammation; P < 0.0001, lipoatrophy; and P = 0.001, epidermal hyperplasia. Syn Rag2−/−, n = 6; Syn Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 3; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 13; Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 17. C: Terminal clinical scores obtained at 6 weeks for BALB/c Rag2−/−, BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/−, or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes. Each data point represents an individual mouse. P = 0.0014, Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−IL13−/− (left; Syn Rag2−/−, n = 4; Syn Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 2; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 25; Allo Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 20). P < 0.0001, Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− (right; Syn Rag2−/−, n = 6; Syn Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 3; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 16; Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 17). D and E: Kaplan-Meier survival curves depicting the percentage of mice unaffected by sclGVHD in groups of BALB/c Rag2−/−, BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/−, or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes. P = 0.0043, Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−IL13−/− (left; Syn Rag2−/−, n = 4; Syn Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 2; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 25; Allo Rag2−/−IL13−/−, n = 20). P < 0.0001, Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− (right; Syn Rag2−/−, n = 6; Syn Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 3; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 16; Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 17). F: Relative average spleen weights of BALB/c Rag2−/−, BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/−, or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier (n = 3 to 5 per group). Spleen weights were normalized to the lowest weight of a syngeneic control of the same host genotype. Data points represent individual mice; error bars indicate means ± SD.

Analysis of infiltrating cells in the skin of mice after the induction of sclGVHD. A: Expression of CD11c and CD115 (M-CSF receptor) in the CD45+CD11b+MHC class II+ population identified in Figure 4A. B: Flow cytometric analysis for CD11b and MHC class II on cells liberated from the back skin BALB/c Rag2−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 3 weeks earlier. Mice were sorted into groups based on the severity of clinical disease; the no-alopecia group had clinical scores ≤1.5 and the alopecia group had clinical scores ≥2. All plots were first gated on CD45+ cells. Note that the levels of CD45+CD11b+MHC class II+ macrophages track with disease severity. C: Flow cytometric analysis for CD11b and MHC class II on cells liberated from the back skin of BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes. All plots were first gated on CD45+ cells. D: Quantitative RT-PCR analysis for Il4ra expression in CD45+CD11b+MHC class II+ macrophages sorted from the skin of BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes. P = 0.009, Syn Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−; P = 0.006, Allo Rag2−/− versus Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−. Syn Rag2−/−, n = 4; Syn Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 4; Allo Rag2−/−, n = 4; Allo Rag2−/−Il4ra−/−, n = 3.

Analysis of CD4+ T cells and mast cells in sclGVHD mice. A: Flow cytometric analysis of skin-infiltrating CD45+CD4+ T cells from the back skin of BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier. All plots were first gated on CD45+ cells. B: Dermal mast cells do not produce IL-13 during sclGVHD. Mast cells were sorted from the skin as CD45+CD117+FcεR+ cells from BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis for the expression of IL13 in CD45+CD11b+MHC class II+ dermal macrophages and mast cells isolated from the same mice (n = 3 per group). C: ELISA for the cytokines IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-17 in tissue culture supernatants from restimulated CD4+ T cells isolated from subcutaneous lymph nodes of BALB/c Rag2−/−, BALB/c Rag2−/−IL13−/−, or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received either syngeneic BALB/c or allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier (n = 3 per group). D: Representative FACS plot of CD4 versus Foxp3 on CD3+ cells isolated from the cutaneous lymph nodes of BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier. E: Quantification of the percentage of CD4+Foxp3+ T cells relative to total number of T cells (left; P < 0.001) or the percentage of CD3+CD4+T cells expressing Foxp3 (right; P < 0.001) on cells isolated from the cutaneous lymph nodes of BALB/c Rag2−/− or BALB/c Rag2−/−Il4ra−/− hosts that received allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes 2 weeks earlier (n = 4 per group).

An IL-4–responsive signature is enriched in the inflammatory subset of SSc. A: Data for the 491 IL-4–responsive genes were extracted from the scleroderma skin biopsy gene expression data set of Milano et al.4 Expression of the experimentally derived IL-4–responsive gene expression signature from human dermal fibroblasts in the human scleroderma subsets (Milano et al4) was quantified by Pearson's correlation coefficient. The IL-4–responsive centroid is shown to the left of the heat map. Human skin samples are organized by intrinsic subsets and the Pearson's correlation coefficients are plotted below the heat map. B: Genomica20 pathway analysis of the IL-13– and IL-4–responsive gene signatures demonstrates that similar pathways are enriched in response to each cytokine in human dermal fibroblasts. A Venn diagram indicates the approximately 60% overlap of the signatures.

Additional analysis of anti-CCL2/12 treatment on the course of sclGVHD. Terminal clinical scores (A) and representative H&E-stained sections from back skin obtained at 6 weeks (B) for BALB/c Rag2−/− hosts that received allogeneic B10.D2 splenocytes, subsequently randomized to biweekly injections of either blocking antibodies to CCL2 and CCL12 (n = 20) or an isotype control antibody (n = 20). Individual mouse scores are shown. Error bars indicate mean ± SD. P = 0.0008, clinical score. Original magnification, ×100.

Evaluation of IL-13 pathway genes in human SSc patients. A and B: Correlation of IL13RA1 gene expression with IL4RA, GAPDH, CCL2, and CCL4 in skin biopsies from SSc patients. 0.79, IL13RA1 versus IL4RA; R2 = 0.02, IL13RA1 versus GAPDH; R2 = 0.45, IL13RA1 versus CCL2; and R2 = 0.76. *P < 0.015, IL13RA1 versus CCL4. C: Quantitative RT-PCR analysis (upper panels) for the expression of ADAM8 and TIMP1 in skin biopsies from diffuse SSc patients and unaffected controls (data points represent individuals; error bars indicate means ± SEM), and correlation of ADAM8 and TIMP1 expression (lower panels) with mRSS in diffuse SSc patients. *P < 0.015. R2 = 0.54, ADAM8; R2 = 0.52, TIMP1. (D) Correlation of ARG1 and COX2 expression with mRSS in diffuse SSc patients. R2 = 0.17, ARG1; R2 = 0.009, COX2. P values were not significant for either ARG1 or COX2.

References

- 1.Denton C.P., Black C.M., Abraham D.J. Mechanisms and consequences of fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:134–144. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu Y.S., Kong J., Cheema G.S., Keen C.L., Wick G., Gershwin M.E. The immunobiology of systemic sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;38:132–160. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogai V., Lories R.J., Guiducci S., Luyten F.P., Matucci Cerinic M. Animal models in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:941–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milano A., Pendergrass S.A., Sargent J.L., George L.K., McCalmont T.H., Connolly M.K., Whitfield M.L. Molecular subsets in the gene expression signatures of scleroderma skin. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002696. [Erratum appeared in PLoS One 2008, 3(10). doi: 10.1371/annotation/05bed72c-c6f6-4685-a732-02c78e5f66c2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruzek M.C., Jha S., Ledbetter S., Richards S.M., Garman R.D. A modified model of graft-versus-host-induced systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) exhibits all major aspects of the human disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1319–1331. doi: 10.1002/art.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sargent J.L., Milano A., Bhattacharyya S., Varga J., Connolly M.K., Chang H.Y., Whitfield M.L. A TGFbeta-responsive gene signature is associated with a subset of diffuse scleroderma with increased disease severity. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:694–705. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sargent J.L., Milano A., Connolly M.K., Whitfield M.L. Scleroderma gene expression and pathway signatures. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:205–211. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung L., Fiorentino D.F., Benbarak M.J., Adler A.S., Mariano M.M., Paniagua R.T., Milano A., Connolly M.K., Ratiner B.D., Wiskocil R.L., Whitfield M.L., Chang H.Y., Robinson W.H. Molecular framework for response to imatinib mesylate in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:584–591. doi: 10.1002/art.24221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellwood-Yen K., Graeber T.G., Wongvipat J., Iruela-Arispe M.L., Zhang J., Matusik R., Thomas G.V., Sawyers C.L. Myc-driven murine prostate cancer shares molecular features with human prostate tumors [Erratum appeared in Cancer Cell 2005, 8:485] Cancer Cell. 2003;4:223–238. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herschkowitz J.I., Simin K., Weigman V.J., Mikaelian I., Usary J., Hu Z., Rasmussen K.E., Jones L.P., Assefnia S., Chandrasekharan S., Backlund M.G., Yin Y., Khramtsov A.I., Bastein R., Quackenbush J., Glazer R.I., Brown P.H., Green J.E., Kopelovich L., Furth P.A., Palazzo J.P., Olopade O.I., Bernard P.S., Churchill G.A., Van Dyke T., Perou C.M. Identification of conserved gene expression features between murine mammary carcinoma models and human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweet-Cordero A., Mukherjee S., Subramanian A., You H., Roix J.J., Ladd-Acosta C., Mesirov J., Golub T.R., Jacks T. An oncogenic KRAS2 expression signature identified by cross-species gene-expression analysis. Nat Genet. 2005;37:48–55. doi: 10.1038/ng1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J.S., Chu I.S., Mikaelyan A., Calvisi D.F., Heo J., Reddy J.K., Thorgeirsson S.S. Application of comparative functional genomics to identify best-fit mouse models to study human cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1306–1311. doi: 10.1038/ng1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pendergrass S.A., Lemaire R., Francis I.P., Mahoney J.M., Jr, Lafyatis R., Whitfield M.L. Intrinsic gene expression subsets of diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis are stable in serial skin biopsies. J Investig Dermatol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noben-Trauth N., Shultz L.D., Brombacher F., Urban J.F., Jr, Gu H., Paul W.E. An interleukin 4 (IL-4) independent pathway for CD4+ T cell IL-4 production is revealed in IL-4 receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10838–10843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenzie G.J., Emson C.L., Bell S.E., Anderson S., Fallon P., Zurawski G., Murray R., Grencis R., McKenzie A.N. Impaired development of Th2 cells in IL-13-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;9:423–432. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray L.A., Argentieri R.L., Farrell F.X., Bracht M., Sheng H., Whitaker B., Beck H., Tsui P., Cochlin K., Evanoff H.L., Hogaboam C.M., Das A.M. Hyper-responsiveness of IPF/UIP fibroblasts: interplay between TGFbeta1, IL-13 and CCL2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2174–2182. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bult C.J., Eppig J.T., Kadin J.A., Richardson J.E., Blake J.A. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): mouse biology and model systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D724–D728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisen M.B., Spellman P.T., Brown P.O., Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tusher V.G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [Erratum appeared in Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001, 98:10515] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dennis G., Jr, Sherman B.T., Hosack D.A., Yang J., Gao W., Lane H.C., Lempicki R.A. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal E., Shapira M., Regev A., Pe'er D., Botstein D., Koller D., Friedman N. Module networks: identifying regulatory modules and their condition-specific regulators from gene expression data. Nat Genet. 2003;34:166–176. doi: 10.1038/ng1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clements P., Lachenbruch P., Siebold J., White B., Weiner S., Martin R., Weinstein A., Weisman M., Mayes M., Collier D. Inter and intraobserver variability of total skin thickness score (modified Rodnan TSS) in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1995:1281–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X., Seed B. A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bachar O., Rose A.C., Adner M., Wang X., Prendergast C.E., Kempf A., Shankley N.P., Cardell L.O. TNF alpha reduces tachykinin, PGE2-dependent, relaxation of the cultured mouse trachea by increasing the activity of COX-2. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:220–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brys L., Beschin A., Raes G., Ghassabeh G.H., Noël W., Brandt J., Brombacher F., De Baetselier P. Reactive oxygen species and 12/15-lipoxygenase contribute to the antiproliferative capacity of alternatively activated myeloid cells elicited during helminth infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:6095–6104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fulkerson P.C., Fischetti C.A., Hassman L.M., Nikolaidis N.M., Rothenberg M.E. Persistent effects induced by IL-13 in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:337–346. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0474OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wynn T.A. IL-13 effector functions. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasegawa M., Sato S., Nagaoka T., Fujimoto M., Takehara K. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-13 are elevated in patients with localized scleroderma. Dermatology. 2003;207:141–147. doi: 10.1159/000071783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGaha T.L., Bona C.A. Role of profibrogenic cytokines secreted by T cells in fibrotic processes in scleroderma. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:174–181. doi: 10.1016/s1568-9972(02)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granel B., Chevillard C., Allanore Y., Arnaud V., Cabantous S., Marquet S., Weiller P.J., Durand J.M., Harle J.R., Grange C., Frances Y., Berbis P., Gaudart J., de Micco P., Kahan A., Dessein A. Evaluation of interleukin 13 polymorphisms in systemic sclerosis. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:693–699. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuschiotti P., Medsger T.A., Jr, Morel P.A. Effector CD8+ T cells in systemic sclerosis patients produce abnormally high levels of interleukin-13 associated with increased skin fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1119–1128. doi: 10.1002/art.24432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim E.Y., Battaile J.T., Patel A.C., You Y., Agapov E., Grayson M.H., Benoit L.A., Byers D.E., Alevy Y., Tucker J., Swanson S., Tidwell R., Tyner J.W., Morton J.D., Castro M., Polineni D., Patterson G.A., Schwendener R.A., Allard J.D., Peltz G., Holtzman M.J. Persistent activation of an innate immune response translates respiratory viral infection into chronic lung disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:633–640. doi: 10.1038/nm1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hershey G.K. IL-13 receptors and signaling pathways: an evolving web. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:677–690. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1333. quiz 691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmermann N., Doepker M.P., Witte D.P., Stringer K.F., Fulkerson P.C., Pope S.M., Brandt E.B., Mishra A., King N.E., Nikolaidis N.M., Wills-Karp M., Finkelman F.D., Rothenberg M.E. Expression and regulation of small proline-rich protein 2 in allergic inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:428–435. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0269OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez F.O., Helming L., Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi K.L., Giorno R., Claman H.N. Cutaneous mast cell depletion and recovery in murine graft-vs-host disease. J Immunol. 1987;138:4093–4101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellsworth R.E., Decewicz D.J., Shriver C.D., Ellsworth D.L. Breast cancer in the personal genomics era. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:146–161. doi: 10.2174/138920210791110951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okimoto R.A., Van Etten R.A. Navigating the road toward optimal initial therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2011;18:89–97. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32834399a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou L., Askew D., Wu C., Gilliam A.C. Cutaneous gene expression by DNA microarray in murine sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease, a model for human scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:281–292. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.York M.R., Nagai T., Mangini A.J., Lemaire R., van Seventer J.M., Lafyatis R. A macrophage marker, Siglec-1, is increased on circulating monocytes in patients with systemic sclerosis and induced by type I interferons and Toll-like receptor agonists. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1010–1020. doi: 10.1002/art.22382. [Erratum appeared in Arthritis Rheum 2007, 56:1675] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farina G., Lafyatis D., Lemaire R., Lafyatis R. A four-gene biomarker predicts skin disease in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:580–588. doi: 10.1002/art.27220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riccieri V., Rinaldi T., Spadaro A., Scrivo R., Ceccarelli F., Franco M.D., Taccari E., Valesini G. Interleukin-13 in systemic sclerosis: relationship to nailfold capillaroscopy abnormalities. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:102–106. doi: 10.1007/s10067-002-0684-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aliprantis A.O., Wang J., Fathman J.W., Lemaire R., Dorfman D.M., Lafyatis R., Glimcher L.H. Transcription factor T-bet regulates skin sclerosis through its function in innate immunity and via IL-13. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2827–2830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700021104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fichtner-Feigl S., Strober W., Kawakami K., Puri R.K., Kitani A. IL-13 signaling through the IL-13alpha2 receptor is involved in induction of TGF-beta1 production and fibrosis. Nat Med. 2006;12:99–106. doi: 10.1038/nm1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belperio J.A., Dy M., Burdick M.D., Xue Y.Y., Li K., Elias J.A., Keane M.P. Interaction of IL-13 and C10 in the pathogenesis of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:419–427. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0009OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wynn T.A. Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:583–594. doi: 10.1038/nri1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallina G., Dolcetti L., Serafini P., De Santo C., Marigo I., Colombo M.P., Basso G., Brombacher F., Borrello I., Zanovello P., Bicciato S., Bronte V. Tumors induce a subset of inflammatory monocytes with immunosuppressive activity on CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2777–2790. doi: 10.1172/JCI28828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]