Background: Alternative splicing of MYPT1 E23 defines fast versus slow smooth muscle.

Results: Tra2β is required for the splicing of Mypt1 E23 in fast smooth muscle.

Conclusion: Tra2β splicing factor confers unique contractile properties to fast smooth muscle.

Significance: This is the first identification of a gene regulatory pathway conferring sensitivity to cGMP signaling in smooth muscle.

Keywords: PP1, Protein Phosphatase, RNA Splicing, Smooth Muscle, Vascular Biology, cGMP Signaling, Myosin Phosphatase, Transformer

Abstract

Alternative splicing of the smooth muscle myosin phosphatase targeting subunit (Mypt1) exon 23 (E23) is tissue-specific and developmentally regulated and, thus, an attractive model for the study of smooth muscle phenotypic specification. We have proposed that Tra2β functions as a tissue-specific activator of Mypt1 E23 splicing on the basis of concordant expression patterns and Tra2β activation of Mypt1 E23 mini-gene splicing in vitro. In this study we examined the relationship between Tra2β and Mypt1 E23 splicing in vivo in the mouse. Tra2β was 2- to 5-fold more abundant in phasic smooth muscle tissues, such as the portal vein, small intestine, and small mesenteric artery, in which Mypt1 E23 is predominately included as compared with the tonic smooth muscle tissues, such as the aorta and inferior vena cava, in which Mypt1 E23 is predominately skipped. Tra2β was up-regulated in the small intestine postnatally, concordant with a switch to Mypt1 E23 splicing. Targeting of Tra2β in smooth muscle cells using SM22α-Cre caused a substantial reduction in Mypt1 E23 inclusion specifically in the intestinal smooth muscle of heterozygotes, indicating sensitivity to Tra2β gene dosage. The switch to the Mypt1 E23 skipped isoform coding for the C-terminal leucine zipper motif caused increased sensitivity of the muscle to the relaxant effects of 8-Br-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). We conclude that Tra2β is necessary for the tissue-specific splicing of Mypt1 E23 in the phasic intestinal smooth muscle. Tra2β, by regulating the splicing of Mypt1 E23, sets the sensitivity of smooth muscle to cGMP-mediated relaxation.

Introduction

Isoforms of many of the genes that are responsible for smooth muscle contractile diversity are generated by alternative splicing of exons (reviewed in Refs. 1–3). We have selected the myosin phosphatase in a model gene approach to the study of smooth muscle contractile diversity given the crucial role that it plays in regulating smooth muscle contraction and smooth muscle responses to contractile agonists and antagonists (reviewed in Refs. 4, 5). The cassette-type splicing of a 31-nt 3′ alternative exon of myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1 (Mypt1 E232) is evolutionarily conserved, tissue-specific, and developmentally regulated (reviewed in Ref. 3). Mypt1 E23 is predominately included in the phasic (or fast contractile) smooth muscle of the intestines and portal vein as well as in small mesenteric arteries and predominately skipped in the tonic (or slow contractile) smooth muscle of the large arteries and veins (6, 7). The initiation of Mypt1 E23 splicing in phasic smooth muscle tissues occurs in the perinatal period (6, 7) as these tissues develop their unique phasic contractile properties (8–10 and reviewed in Ref. 11). In animal models of portal hypertension (12), mesenteric ischemia (13), and hypertension of pregnancy (14), the fast smooth muscles revert toward the embryonic (slow) pattern of Mypt1 E23 skipping. The regulated splicing of MYPT1 E23 is also proposed to be of great functional importance (reviewed in Refs. 2, 3). The skipping of E23 codes for a MYPT1 isoform that contains a C-terminal leucine zipper motif that is thought to be essential for cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent kinase dimerization and activation of myosin phosphatase (15–17), resulting in smooth muscle relaxation through desensitization to activating concentrations of calcium.

The control mechanisms for tissue-specific splicing of exons in the generation of smooth muscle contractile diversity are not known (reviewed in Ref. 3, 18). In a previous study in rat and chicken, we observed a correlation between tissue-specific, developmentally regulated, and disease-modulating Mypt1 E23 inclusion and transformer 2β (Tra2β, also known as Sfrs10) expression in phasic smooth muscle tissues (19). We also showed sequence-specific binding of Tra2β to Mypt1 E23 and Tra2β activation of MYPT1 E23 splicing in transcripts generated from a mini-gene construct in vitro. Tra2α and β are atypical members of the SR family of RNA binding proteins (reviewed in Refs. 20, 21). Transformer proteins are master regulators of sexual determination in the fly through the regulated splicing of Fruitless and Doublesex alternative exons (reviewed in Ref. 22). The vertebrate homologues of the fly Tra-2, Tra-2α and Tra-2β, have been suggested to regulate the splicing of a number of vertebrate alternative exons on the basis of in vitro studies (reviewed in Refs. 20, 21). However, splicing targets of Transformer proteins have, with few exceptions, yet to be validated in higher organisms in vivo, and tissue-specific functions of Transformer proteins in higher organisms have yet to be defined. Conditional Cre-lox-mediated ubiquitous targeting of mouse Tra2β resulted in early failure of embryo development (E7.5) (23), whereas neuronal-specific targeting with Nestin-Cre resulted in lethality at postnatal day 1 (24), indicating an essential role for the splicing factor in mouse development. In this study we first defined the expression of Tra2β in relation to the developmentally regulated and tissue-specific splicing of Mypt1 E23 in mouse phasic and tonic smooth muscle tissues. We then used smooth muscle cell restricted Cre-lox targeting of Tra2β to test its role in the control of Mypt1 E23 tissue-specific splicing and smooth muscle contractile function in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Mice were maintained and experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Case Western Reserve University and the University of Nevada, Reno. Mice carrying Tra2β exon 4 homozygously floxed (Tra2βfl/fl, also termed Sfrs10fl/fl and described elsewhere (23)) were mated to SM22α-cre transgenic mice (described in Ref. 25) to target Tra2β specifically in all smooth muscle from early in development (E9.5). SM22α-cre is also active in cardiac muscle cells prenatally (25). The mice were maintained on a C57/Bl6NCrl genetic background. Mice were genotyped as described previously (23, 25).

PCR Assays

Total RNA was extracted from tissues using the Qiagen RNeasy mini kit. cDNA was synthesized in a 20-μl reaction using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligo(dT) primers. Splice variants of Mypt1 E23 were PCR-amplified using the oligonucleotide primers 5′-ATTCCTTGCTGGGTCGCTCTGC-3′ and 5′-ATCAAGGCTCCATTTTCATCC-3′ bracketing the alternative exon E23, separated by gel electrophoresis, and percent of Mypt1 product, with exon included, determined as described previously (13). We have demonstrated previously that this assay is highly accurate for determining ratios of exon-included versus exon-skipped transcripts over a wide range of input RNA. The same method was used to assay for splice variants of MLC17 E6 using the oligonucleotide primers 5′-GAATTCAAGGAGGCTTTCCAGCTGT-3′ and 5′-CCATTCAGCACCATCCGGAC-3′.

In real-time PCR assays, cDNA was added to a mixture containing 12.5 μl of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and 1 μl of each primer in a final volume of 25 μl. Tra2β was amplified with the oligonucleotide primers 5′-GAGGGTACGATCGGGGTTAT-3′ and 5′-CCTGTCTTGAGCTGCTCTCC-3′. PCR was performed using 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 30 s in a Stratagene Mx3000P system. Values were normalized to SRp20 mRNA with the oligonucleotide primers 5′-GCTAGATGGAAGAACACTATGTGG-3′ and 5′-AATCATCTCGAGGACGACGA-3′. Srp20 was invariant between samples. Relative mRNA levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Western Blot

Tissues were homogenized in 200 μl of lysis buffer containing 125 mm Tris HCl (pH 6.8), 20% sucrose, 10% SDS, and 1% proteinase inhibitor mixture. Proteins (10 μg) were separated on NuPAGE 3–8% Tris acetate or 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) at 50 mA for 1.5 h and transferred to PVDF membranes at 300 mA for 2.5 h. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal antibodies that specifically recognize the Mypt1 carboxy-terminus LZ-negative or LZ-positive sequence (1:3000) (7, 13, 26), non-isoform specific Mypt1 (Abcam), myosin heavy chain (Millipore), goat polyclonal antibody against Tra2β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-33318, 1:1000), Histone H3 (rabbit polyclonal IgG, Abcam, 1:3000, catalog no. ab1791), GAPDH (rabbit polyclonal IgG, Abcam, 1:3000, catalog no. ab9485). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used and detected by ECL chemiluminescence (Pierce). Bands were digitally captured and quantified using Image J software.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde for 3–4 h and soaked in 15% sucrose at 4 °C overnight, rinsed in PBS, and embedded in O.C.T. Compound (Tissue-Tek). Sections were cut at 10-μm thickness on a Leica CM 1850 cryostat. Sections were blocked in PBS containing 10% horse serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA at room temperature for 2 h and then incubated in primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. The antibodies used included a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Tra2β (Abcam, catalog no. Ab66901) at 1:200 dilution, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen) at 1:10,000 dilution, and monoclonal mouse antibody against smooth muscle α-actin conjugated with cy3 (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:1000 dilution. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images were captured using a Spot RT digital camera and Leica DMB microscope and optimized with Adobe Photoshop software.

RNA Immunoprecipitation

RIP was performed as described in Ref. 27, with minor modifications. Bladder tissue (500 mg) was minced on ice, cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, and resuspended in 4 ml of PBS. Glycine was added to a final concentration of 330 mm. Tissue fragments were resuspended in hypotonic buffer, and the nuclear fraction was extracted using the nuclear extract kit according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Active Motif). Samples were precleared with 40 μl of protein G plus agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h at 4 °C. 15 μl of antibodies (anti-Tra2β, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-33318, or normal goat IgG, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-2028, as a control) were bound to 20 μl of protein G plus agarose. Samples were incubated at 4 °C overnight with antibody-bound beads. Beads were washed once in 1 ml of binding buffer (50 mm Hepes, 0.5% Triton X-100, 25 mm MgCl2, 5 mm CaCl2, 20 mm EDTA), once in FA500 (50 mm Hepes, 500 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate), once in LiCl buffer (10 mm Tris, 250 mm LiCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA), and once in TES (10 mm Tris, 10 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA). 75 μl of RIP elution buffer (100 mm Tris (pH 7.8), 10 mm EDTA, 1% SDS) was added for 10-min incubations at 37 °C, repeated, and the eluates pooled. 150 μl of eluate was adjusted to 200 mm NaCl, 20 μg of proteinase K (Roche) was added, and samples were incubated for 1 h at 42 °C and then for 1 h at 65 °C. Phenol/chloroform 5:1 (pH 4.7) (Sigma) was used to extract RNA, which was precipitated with ethanol. 150 ng of RNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript III and oligo dT primer at 50 °C for 1 h. PCR was performed with one-fourth of the cDNA reaction. The forward primer was located within E23 5′- GTGGCCGGCAAGAGTCAGTAT-3′ and the reverse primer in the downstream intron 5′-CACACAATGTATTATTGCAGTGTCC-3′ (Fig. 5A), designed to generate a 150-bp PCR product. PCR products were detected by gel electrophoresis.

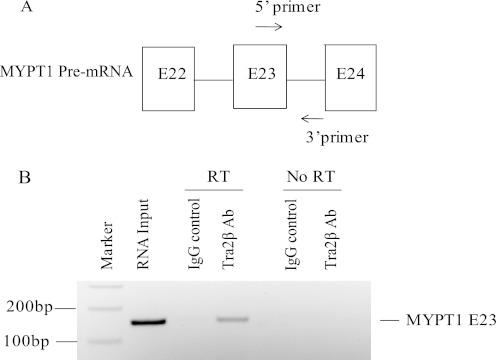

FIGURE 5.

Tra2β binds to Mypt1 E23. RIP was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures” with mouse bladder nuclear extracts reacted with goat polyclonal antibody against Tra2β or normal goat IgG as a control, conjugated to protein G-agarose. A, location of oligonucleotide primers used for PCR amplification of Mypt1 pre-mRNA. B, RT-PCR products were detected by gel electrophoresis. RT-PCR of the input RNA yielded the expected band of 150 bp. RT-PCR of the Tra2β antibody immunoprecipitate also yielded the 150-bp product. No RT-PCR product was obtained when the control IgG was used for immunoprecipitation. No PCR product was generated in control reactions omitting the reverse transcriptase enzyme (No RT). Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

Small Intestinal Smooth Muscle Contractility and Calcium Imaging

Male mice 6 to 8 weeks of age were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by decapitation. The duodenum (the 1-cm segment of small intestine immediately distal to the pyloric sphincter) was removed, and the mucosa and submucosa were removed by sharp dissection as described previously (26, 28). Contractile activity was measured using standard myobath techniques, with each duodenal smooth muscle strip attached to a Fort 10 isometric strain gauge (WPI, Sarasota, FL) in parallel with the circular muscles (28). All preparations contained 0.3 μm tetrodotoxin. A resting force of 0.6 g was applied, and tissues were equilibrated in oxygenated Krebs solution at 37 °C for at least 45 min prior to addition of 1 μmol L−1 carbachol (Cch). Cch was then washed out to allow each duodenal smooth muscle strip to return to its previous pattern of spontaneous phasic contractions. In one set of experiments, individual duodenal smooth muscle strips were incubated with the indicated concentration of 8-Br-cGMP for 20 min, at which time 1 μm Cch was added to the myobath. After 10 min, the Cch and 8-Br-cGMP were washed out, the tissue was allowed to recover, and 1 μm Cch was again added to ensure that the contractile response was unchanged. In another set of experiments, each duodenal smooth muscle strip was stimulated with 1 μm Cch and 8-Br-cGMP added after steady-state force was achieved. Responses were recorded and analyzed using Acqknowledge 3.2.7 software (BIOPAC Systems, Santa Barbara, CA). Contractile responses were measured by comparing the areas under the curves (gram-sec) and the amplitudes and frequencies of phasic contractions at 5 min of incubation of each smooth muscle strip with 1 μm Cch alone or with 1 μm Cch in the presence of the indicated concentrations of 8-Br-cGMP for 20 min. Tetrodotoxin, carbachol, and 8-Br-cGMP were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA).

For calcium measurements, the tissues were dissected as described earlier and pinned down onto a Sylgard-coated dish. After an equilibration period of 1 h, the preparation was loaded with Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 AM, 10 μg/ml (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in a solution of 0.02% dimethyl sulfoxide and 0.01% non-toxic detergent Cremophor EL for 30 min at 25 °C, followed by 15 min of incubation with wortmannin (10 μm) (Sigma-Aldrich) to restrict tissue movement during acquisition. After incubation, the preparation was perfused with warm Krebs solution at 37 °C for 30 min to allow for de-esterification of the dye. Preparations were imaged using an Eclipse E600FN microscope (Nikon, Inc., Melville, NY) equipped with a number of lenses at different magnifications (×20–40, Nikon Plan Fluor). The indicator dye was excited at 488 nm, and the fluorescence emission (> 515 nm) was detected using a cooled, interline transfer charge coupled device camera system (Imago, TILL Photonics, Grafelfing, Germany). Image sequences were collected after 4 × 4 binning of the 344 × 260 line image in TILLvisION software (T.I.L.L. Photonics GmbH, Grafelfing, Germany). Image sequences of Ca2+ activity in duodenal smooth muscle were analyzed and constructed using a custom software (Volumetry G7wv) (29). The average frequency of Ca2+ transients was calculated for a 60-s period after Cch application and under control conditions. The Ca2+ transient frequency was grouped for all experiments because of the infrequent appearances of spontaneous activity. The control Ca2+ transient frequency averaged 1.35 ± 1.2 cycles/min.

Intestinal Transit Time

Male mice 8–12 weeks of age deprived of food overnight were administrated 100 μl of charcoal test meal (10% charcoal, 10% gum Arabic, 80% water) by orogastric gavage the following morning. The mice were sacrificed 30 min after receiving the test meal, and the distance traveled by the black test meal was measured. Gastrointestinal transit was characterized by the transit index, defined as the ratio between the distance from the pylorus to the front of the charcoal divided by the total length of the small intestine (pylorus to cecum) multiplied by 100.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. Data were compared with one-way analysis of variance and Student's t test. Differences were considered statistically significant at a value of p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Tissue-specific Expression of Mypt1 Isoforms

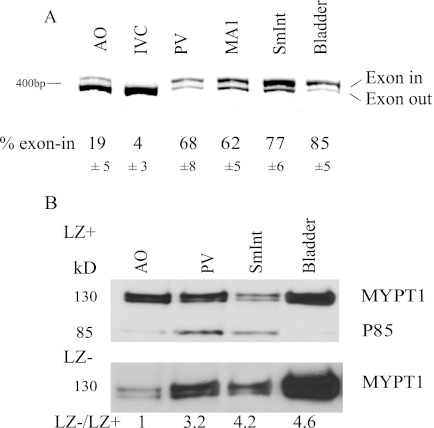

We first examined the expression of Mypt1 E23-included versus skipped isoforms in phasic versus tonic adult mouse smooth muscle tissues using our highly sensitive and accurate conventional PCR assay. Mypt1 E23 was predominately skipped in the tonic smooth muscle of the mouse aorta and inferior vena cava (Fig. 1A, IVC). Mypt1 E23 was predominately included in the phasic smooth of the portal vein, small intestine (duodenum), and bladder, as well as in a small resistance artery, the first branch of the superior mesenteric artery (MA1). A corresponding pattern of Mypt1 protein isoforms was observed using antibodies that recognize the unique Mypt1 C termini in the different isoforms. Mypt1 transcripts that skip E23 code for a protein that contains a C-terminal leucine zipper motif (LZ+), whereas inclusion of the 31-nucleotide exon shifts the reading frame and, thus, codes for a unique C-terminal sequence designated leucine zipper negative (LZ-). In aortic homogenates, the signal detected with the LZ+ antibody was significantly stronger than the signal detected with the LZ- antibody (Fig. 1B), consistent with the predominance of the Mypt1 E23 skipped transcript coding for the LZ+ isoform. The LZ+ antibody also detects the nearly identical C-terminal LZ sequence present in MYPT family members p85 (85-kDa band) and M21 (not shown). In the tissue homogenates from the phasic smooth muscle tissues, including the portal vein, small intestine, and bladder, the ratios of the LZ- to LZ+ signals were several-fold higher than that of the aorta. This observation is consistent with the predominance of the Mypt1 E23-included transcript coding for the Mypt1 LZ- isoform in these tissues. The doublet observed in the 130-kDa MYPT1 is generated by the invariant alternative splicing of exons 13 and 14 (7, 30).

FIGURE 1.

Mypt1 E23 included and skipped transcripts coding for the C-terminal LZ-negative and LZ-positive isoforms, respectively, in tonic versus phasic mouse smooth muscle tissues. A, oligonucleotide primers that flank E23 were used to amplify E23-included and E23-skipped transcripts in a single PCR. Amplified products were separated by gel electrophoresis and percent exon-included transcripts (Exon-in/total) calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures” (mean ± S.D., n = 3). In prototypical tonic smooth muscle tissues such as aorta (AO) and inferior vena cava (IVC), E23 skipping predominates. In the phasic or mixed tissues such as portal vein (PV), first-order mesenteric artery (MA1), small intestine, and bladder E23 inclusion predominates. B, anti-Mypt1 LZ+ (E23 skipped) or LZ- (E23 included) isoform-specific antibodies were used to define tissue-specific expression of Mypt1 subunit isoforms by Western blot analysis. Tissue lysates containing 10 μg of protein were run on duplicate gels, blotted, and probed with antibodies specific to LZ+ or LZ- antibodies as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Blots and quantification representative of three separate experiments are shown. The LZ+ antibody recognizes nearly identical LZ sequences present in MYPT family members Mypt1 (∼130 kDa), p85 (85 kDa), and M21. The LZ- antibody recognizes only Mypt1. The doublet at 130 kDa represents Mypt1 central alternative exon splice variant isoforms. MYPT1 LZ+ and LZ- bands were quantified as described under “Experimental Procedures” and are shown as the ratio of LZ-/LZ+ normalized to the aorta, which is assigned a value of 1. The relative abundance of the LZ- to LZ+ isoform is several-fold greater in the phasic smooth muscle as compared with the aorta, consistent with the increased E23 inclusion in these tissues.

Tra2β Expression Correlates with Mypt1 E23 Splice Variants

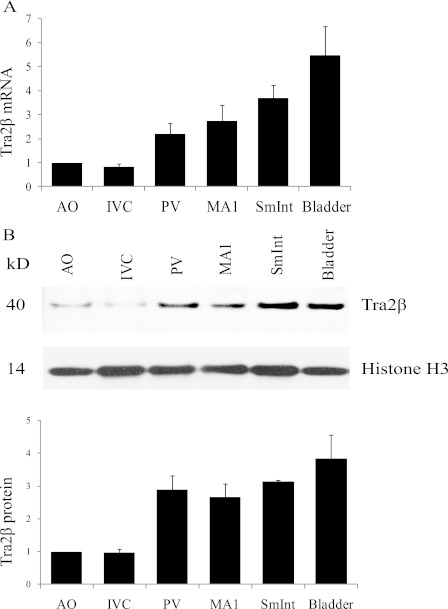

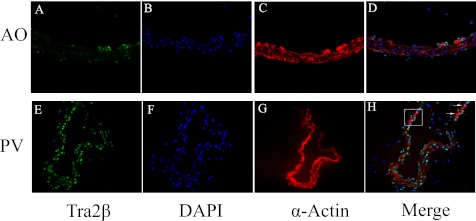

We next measured Tra2β expression levels to determine whether the association between its expression and MYPT1 E23 splice variants that we observed in other species (19) was also present in the mouse. As measured by real-time PCR, Tra2β mRNA was 2- to 5-fold more abundant in the phasic as compared with tonic smooth muscle tissues (Fig. 2A). Similarly, Tra2β protein was 3- to 5-fold more abundant in the phasic as compared with tonic smooth muscle tissues (Fig. 2B). The difference in Tra2β expression between the phasic and tonic smooth muscle was even more striking when examined in situ by immunohistochemistry. The smooth muscle cells of the adult mouse aorta were almost entirely negative for Tra2β staining (Fig. 3, A–D). The few nuclei that were positive for Tra2β resided outside of the medial smooth muscle, identified by α-actin staining, and likely represent endothelial and adventitial cells. In contrast, in the phasic portal vein, nearly all of the nuclei were positive for Tra2β (Fig. 3, E--H), and costaining for α-actin identified these as smooth muscle cells (H, inset).

FIGURE 2.

Tra2β expression in tonic versus phasic smooth muscle tissues. A, Tra2β mRNA was measured by real-time PCR and normalized to SRp20 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Tra2β mRNA was 2- to 5-fold more abundant in the phasic smooth muscle (portal vein (PV), first-order mesenteric artery (MA1), small intestine (SmInt), and bladder) as compared with the tonic smooth muscle (aorta (AO) and inferior vena cava (IVC)), whereas SRp20 was invariant. B, Tra2β protein was measured in tissue lysates by Western blot analysis and normalized to histone H3 on the same blot as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Tra2β protein was 3- to 4-fold more abundant in the phasic smooth muscle (PV, MA1, small intestine, and bladder) as compared with the tonic smooth muscle (AO, IVC), whereas histone H3 was invariant. Data are displayed as mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 3).

FIGURE 3.

Tra2β expression in phasic versus tonic smooth muscle demonstrated by immunohistochemistry. Adult mouse aorta (A–D) and portal vein (E–H) were processed as described under “Experimental Procedures” and stained with Tra2β rabbit polyclonal antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (A and E), DAPI to identify nuclei (B and F), and mouse monoclonal antibody against smooth muscle α-actin conjugated with cy3 (C and G). D and H, the merge of the images shows nuclear staining of Tra2β in α-actin positive smooth muscle of the portal vein but not the aorta. The inset in H shows Tra2β-positive smooth muscle cells. All magnifications were ×200 except for the inset (H), which was ×400.

Developmental Up-regulation of Mypt1 E23 Splicing and Tra2β in Phasic Smooth Muscle

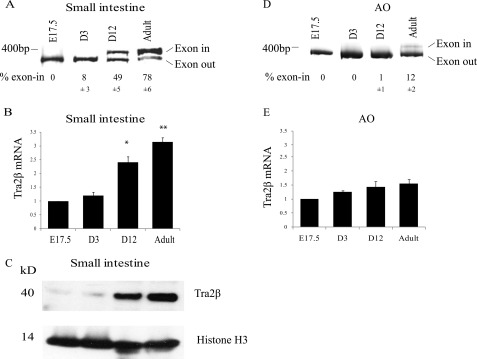

We next measured the expression of Tra2β in relation to Mypt1 E23 splicing during development to determine whether it is up-regulated at the appropriate time to mediate the tissue-specific initiation of Mypt1 E23 splicing as part of the implementation of the fast gene program. We observed a switch from skipping to inclusion of Mypt1 E23 in the mouse small intestine between postnatal day three (D3) and maturity (Fig. 4A). The switch to the MYPT1 E23-included splice variant was concordant with the up-regulation of Tra2β mRNA and protein (Fig. 4, B and C). The switch to Mypt1 E23 splicing and up-regulation of Tra2β was specific to the intestinal phasic smooth muscle, as in the aorta, Mypt1 E23 was always almost exclusively skipped, and Tra2β levels were unchanged through development (Fig. 4, D and E).

FIGURE 4.

Postnatal switch to Mypt1 E23 inclusion and up-regulation of Tra2β in mouse small intestine. Mypt1 E23 splice variants were measured as described in Fig. 1 and under “Experimental Procedures.” Tra2β mRNA was measured by real-time PCR and protein by Western blot analysis as described in Fig. 2 and under “Experimental Procedures.” A, small intestine switches from Mypt1 E23 skipping to E23 inclusion after postnatal Day 3 (D3). B, there was concordant up-regulation of Tra2β mRNA (B) and Tra2β protein (C), whereas SRp20 and histone H3, used for normalization, were unchanged. In contrast, Mypt1 E23 isoforms (D) and Tra2β mRNA levels (E) measured by real-time PCR were invariant throughout aortic development. Data are presented as mean ± S.D., n = 3. A Western blot representative of multiple experiments is shown. *, p < .01; **, p < .001 versus E17.5 and D3.

Tra2β Binds to Mypt1 E23 in Vivo

To determine whetherTra2β binds to Mypt1 E23 in vivo, we performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments incubating Tra2β antibody with mouse bladder nuclear extracts. The oligonucleotide primers were designed to hybridize with sequence within Mypt1 E23 and the downstream intron (Fig. 5A and “Experimental Procedures”). These primers amplified the expected 150-bp product when used in RT-PCR with the input nuclear fraction (Fig. 5B, RNA input). Mypt1 pre-mRNA was amplified by RT-PCR after RIP with Tra2β antibody but not when an IgG control antibody was used in the immunoprecipitation reaction (Fig. 5B). No product was obtained in control reactions in which the reverse transcriptase enzyme was omitted (No RT), demonstrating that the PCR product is generated from the input RNA.

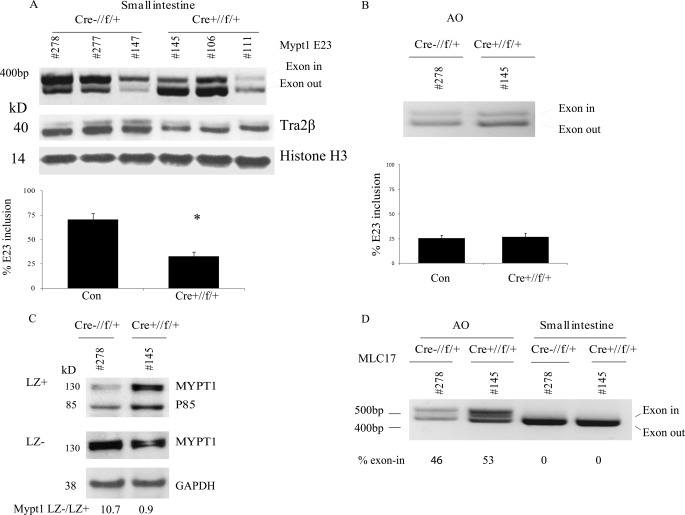

Tra2β Is Necessary for Mypt1 E23 Splicing in Intestinal Smooth Muscle

Tra2β was targeted in smooth muscle cells to determine whether it is required for Mypt1 E23 splicing in vivo. Mice carrying Tra2β alleles with loxP sites flanking exon 4 (23) were crossed with SM22α-cre transgenic mice (25). This Sm22α-cre line expresses Cre recombinase in visceral and vascular smooth muscle as early as embryonic day 9.5 and in embryonic cardiac muscle cells as well (25). The Tra2βflox allele, upon cre recombination, results in a null allele (23). Mice with the genotype SM22α-cre:Tra2bfl/fl were not recovered 21 days after birth (18 matings), nor at E17.5 (three matings), suggesting embryonic lethality. Mice with the genotype SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt were present at Mendelian frequencies 21 days after birth. These mice did not exhibit any obvious phenotypical abnormalities up to 6 months of age. The SM22α-Cre:Tra2βfl/wt mice had ∼50% reduction of Tra2β protein in smooth muscle tissues, demonstrating efficient SM22α-cre-mediated recombination (Fig. 6A). This reduction in Tra2β expression caused a significant reduction in Mypt1 E23-included transcripts in the small intestine of adult mice (Fig. 6A). Twenty-five percent of transcripts in the SM22α-Cre:Tra2βfl/wt mouse small intestine had E23-included compared with 70% of transcripts in Cre-negative littermates. The latter was not different from wild-type mice (Fig. 1) nor from mice that only expressed the Cre transgene (data not shown). The level of E23 inclusion in the small intestine of the Tra2β-targeted mice was similar to that of the aorta, the prototypical tonic smooth muscle. Mypt1 E23 inclusion was unchanged in the aorta of the SM22αCre:Tra2βfl/wt mice (Fig. 6B). Mypt1 E23 inclusion was also reduced in SM22α-Cre:Tra2βfl/wt stomach (17 + 3% versus 37 + 5%, n = 9, p < 0.01) but was unchanged in the bladder (73 + 12 versus 81 + 5, n = 9, p > 0.05).

FIGURE 6.

Tra2β is required for Mypt1 E23 inclusion specifically in the phasic intestinal smooth muscle. To specifically target Tra2β in smooth muscle cells, Tra2β-floxed mice were mated to SM22α-cre (SMcre) transgenic mice. A, Mypt1 E23 splice variants were measured by conventional RT-PCR as described in Fig. 1 and under “Experimental Procedures.” A representative gel is shown displaying PCR products from the small intestines of three control and three experimental mice, below which is a graph of the quantification from all of the mice assayed (n = 13; *, p < .001). The SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt mouse small intestine showed a significant reduction of Mypt1 E23 inclusion as compared with Cre-negative littermate controls (Tra2βfl/wt). The abundance of Tra2β protein, normalized to histone H3 protein, was reduced by ∼50% in the cKO mice small intestines as measured by Western blot analysis. B, no change in Mypt1 E23 inclusion was observed in the aorta (AO) of these mice. C, Mypt1 LZ+ (E23 skipped) or LZ- (E23 included) isoform-specific antibodies were used to quantify Mypt1 subunit isoforms by Western blot analysis as described in Fig. 1 and under “Experimental Procedures.” Representative blots and their quantification comparing cKO versus control samples are shown (mice listed in A, n = 3). The LZ+ antibody recognizes nearly identical LZ sequences present in Mypt family members Mypt1 (∼130 kDa) and p85 (85 kDa). The ratio of the Mypt1 LZ- to LZ+ signals is reduced in the SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt mouse small intestine as compared with the Cre-negative littermate control (Tra2βfl/wt). D, a conventional RT-PCR assay was used to measure myosin light chain 17 (MLC17) E6 splice variants. A representative gel is shown. E9 is entirely skipped in the small intestinal smooth muscle and included in approximately one-half of the transcripts from the aortic smooth muscle. There was no change in MLC17 E9 inclusion in the aorta or small intestine of the SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt mice.

The reduction in Mypt1 E23 inclusion in the small intestine of the SM22αCre:Tra2βfl/wt mice was reflected at the protein level by an increase in the Mypt1 LZ+ signal and a reduction in the ratio of the Mypt1 LZ- to LZ+ signal (Fig. 6C). There was no change in the abundance of p85 normalized to GAPDH (1.2 + 0.3-fold, n = 3, p > 0.05). There also was no change in the total abundance of Mypt1 or smooth muscle myosin heavy chain proteins (data not shown).

To determine whether this effect of Tra2β targeting was specific to MYPT1 E23, we examined MLC17 E6 splice variants, which also undergo developmentally regulated and tissue-specific (phasic versus tonic smooth muscle) exon splicing but in a pattern opposite to that of MYPT1 E23 (reviewed in Ref. 3). The ratios of exon-included to exon-skipped MLC17 transcripts was unchanged in the small intestine or aorta of the SM22αCre:Tra2βfl/wt mice (Fig. 6D).

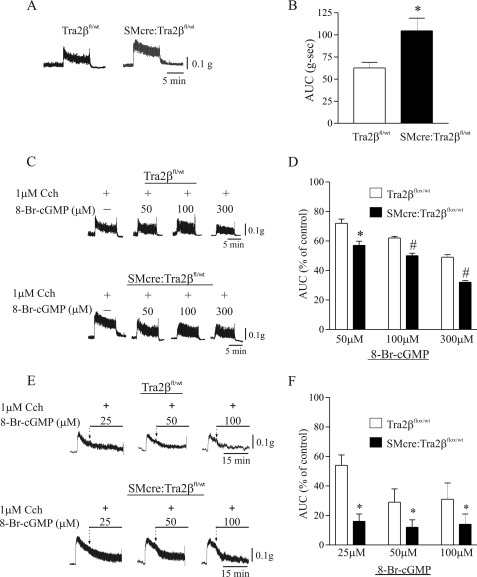

Smooth Muscle Function in SM22αCre:Tra2βfl/wt Mice

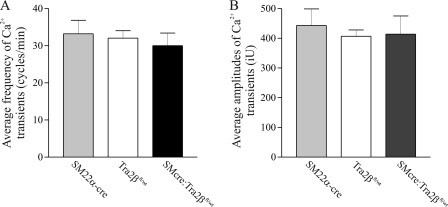

In previous studies we have demonstrated that the expression of the Mypt1 E23 included/LZ- isoform in phasic smooth muscle is associated with a relative inability of cGMP to activate myosin phosphatase and desensitize the muscle to calcium relative to tonic smooth muscle expressing the MYPT1 E23-skipped/LZ+ isoform (6, 7). The increase in the Mypt1 E23-skipped/LZ+ isoform in the SM22α-Cre:Tra2βfl/wt mouse small intestine is predicted to increase the sensitivity of the smooth muscle to cGMP-mediated relaxation (reviewed in Ref. 3). To test this model, contractile function of the circular muscle layer of the duodenal small intestine was tested in mature SM22α-Cre:Tra2βfl/wt male mice. The small intestinal smooth muscle from the SM22α-Cre:Tra2βfl/wt mice generated ∼50% greater total force than that of the Tra2βfl/wt littermates after activation of force with Cch (1 μm) ex vivo under isometric conditions (Fig. 7, A and B). The small intestinal smooth muscle from the SM22αCre:Tra2βfl/wt mice were also more sensitive to 8-Br-cGMP at concentrations of 50–300 μm. Preincubation of the muscle with 8-Br-cGMP at each of these concentrations caused greater inhibition of force production to 1 μm Cch as compared with Tra2bfl/wt littermates (Fig. 7, C and D). 8-Br-cGMP also caused greater relaxation of the cKO mice small intestine when added at concentrations of 25–100 μm after Cch-induced contractions (Fig. 7, E and F). The relaxation to 8-Br-cGMP was not different between Cre-positive and Cre-negative mice (data not shown). There was no difference in the frequency or amplitude of the calcium transients after Cch activation (Fig. 8). In vivo, the intestinal transit index, a measure of the distance traveled by charcoal through the small intestine, was reduced (SM22αCre:Tra2βfl/wt 57.8 ± 7.8 versus Tra2βfl/wt 87.7 ± 2.4; n = 5, p < 0.05). These results provide the first genetic evidence that expression of the MYPT1 E23-/LZ+ isoform determines smooth muscle sensitivity to cGMP signaling.

FIGURE 7.

Switch to the Mypt1 LZ+ isoform in SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt small intestine circular smooth muscle increases contractile force and sensitivity to cGMP. Duodenal smooth muscle was isolated from adult SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt mice and Cre-negative littermate controls (Tra2βfl/wt) and mounted in a wire myograph as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A and B, force is reported as the total force (area under curve (AUC) after activation with carbachol (1 μm). Representative force tracings are shown. The SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt mouse circular smooth muscle generated significantly more force after activation than did the littermate controls (Tra2βfl/wt) (n = 3; p < 0.01). C and D, muscles were preincubated with increasing concentrations of 8-Br-cGMP prior to activation with carbachol (1 μm). Force is reported as the percent of total force obtained relative to that in the absence of 8-Br-cGMP (% of control). Representative force tracings are shown. The SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt mouse circular smooth muscle had greater reductions in force at all concentrations of 8-Br-cGMP as compared with Tra2βfl/wt littermate controls (n = 3; *, p < 0.05; #, p < 0.01). E and F, muscles were incubated with carbachol (1 μm) and the increase in tone allowed to reach a plateau level before adding the indicated concentration of 8-Br-cGMP. Force is reported as the percent of force obtained in the presence of 8-Br-cGMP relative to that in the absence of 8-Br-cGMP (% of control). Representative force tracings are shown. The SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt mouse circular smooth muscle had greater reductions in force at all concentrations of 8-Br-cGMP as compared with Tra2βfl/wt littermates (n = 3; *, p < 0.01).

FIGURE 8.

Carbachol induced Ca2+ transients are not changed in SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt small intestine circular smooth muscle cells. Duodenal smooth muscle was isolated from adult SM22α-cre mice, SM22α-cre:Tra2βfl/wt mice, and Cre-negative littermate controls (Tra2βfl/wt), and Ca2+ transients visualized and analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The average (A) frequencies and (B) amplitudes of Ca2+ transients were calculated for 60-s periods during carbachol (1 μm) activation (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Although it is now well accepted that a great deal of the diversity in muscle is generated by alternative splicing of exons, there remains limited understanding of the control mechanisms. Some investigations have examined splicing control in the differentiation or developmental maturation of smooth, cardiac, or skeletal muscle (reviewed in Refs. 18, 31), but the control mechanisms for splicing-dependent generation of muscle functional diversity remain unexplained. This contrasts with the well developed understanding of transcriptional control mechanisms for muscle diversity (reviewed in Refs. 32–34).

In this study we show that the splicing of MYPT1 E23 is highly tissue-specific and developmentally regulated in the mouse. It is predominately included in the mature phasic (fast) contractile smooth muscle and predominately skipped in the mature tonic (slow) smooth muscle. Developmentally, the phasic smooth muscle undergoes a complete switch from exon skipping to inclusion in the postnatal period. This binary system of exon inclusion versus exon skipping provides a relatively simple system for the study of smooth muscle phenotypic specification. That this pattern of splicing is highly conserved in other mammals (although it has yet to be examined in humans) and chicken (19) suggests an evolutionarily conserved control mechanism(s).

We have provided several lines of evidence that support Tra2β as a tissue-specific regulator of MYPT1 E23 splicing and, by extension, smooth muscle phenotype (discussed further below). The first line of evidence is the concordance of Tra2β expression with Mypt1 E23 inclusion during development and across tissues. This is specific, as the expression of the classic SR proteins is invariant in these contexts, and conserved in chicken and rat (19). Tra2β has been described as ubiquitously expressed, predominately on the basis of limited in vivo analysis (35–38) and the erroneous approach of analysis of cell lines, as demonstrated by McKee et al. (39) with respect to splicing factors and the brain. Tra2β expression in vivo is high in other cell types, e.g. mouse male germ cells and neural cells (40), in which it is also proposed to regulate tissue-specific activation of splicing of weak exons (41). The full spectrum of its developmental and tissue-specific expression and activity remains to be determined.

The most direct evidence supporting the necessity of Tra2β in the tissue-specific splicing of Mypt1 E23 is the substantial loss of splicing with SM22α-cre-mediated targeting of Tra2β in smooth muscle. That this loss of E23 splicing occurs in heterozygotes suggests that this splicing is highly sensitive to Tra2β gene dosage. The absence of an effect in the tonic smooth muscle of the aorta in which Tra2β expression is low supports a tissue-specific function for Tra2β and supports the functional importance of the several-fold increased expression of Tra2β in the phasic relative to tonic smooth muscle tissue. Of note the difference in Tra2β expression between phasic and tonic smooth muscle in chicken and rat tissues was 5- to 10-fold, much greater than that reported here in mouse tissues and more in line with the differences observed in the mouse in situ by immunohistochemistry in this study.

These observations are consistent with a model derived from in vitro studies in which mammalian Tra2β binds with low affinity but functions as a strong trans-activator of exon splicing (19, 42). This model of Tra2β functioning as a dosage-sensitive, tissue-specific activator of splicing of weak exons is consistent with the specialized role of Tra homologues in Drosophila, where loss of function mutation results in altered sexual differentiation, whereas the flies are otherwise phenotypically normal (reviewed in Ref. 43). It is also consistent with the initial characterization of Tra2β in higher organisms in which it was shown to be required for enhancer-dependent but not constitutive splicing in vitro (44).

Tra2β was detected bound to MYPT1 E23 in vivo. In vitro Tra2β binding to E23 was dependent upon the sequence GCAAGAG within the E23 (19), a good match to the recently defined consensus sequences for mammalian Tra2β RNA binding defined by in vivo (24) and in vitro experiments (41, 45). In toto, these results are consistent with Tra2β directly binding and activating Mypt1 E23 splicing in vivo, as we showed previously in vitro using splicing of a mini-gene transcript (19). A limitation of the binding assay used in this study is the possibility that Tra2β binds to the MYPT1 pre-mRNA after cell disruption. This can be addressed in future studies using the more laborious cross-linking and immunoprecipitation assay, in which proteins are fixed to their RNA targets prior to cell disruption. This assay, in conjunction with a more comprehensive analysis of altered splice variants with loss of function, will more comprehensively determine the direct targets of Tra2β in phasic smooth muscle. Whether Tra2β is sufficient for splicing of MYPT1 E23 in vivo can be tested in future experiments by forcing its expression in tonic smooth muscle, where its endogenous level and MYPT1 E23 splicing are low.

The homozygous targeting of Tra2β in heart and smooth muscle mediated by SM22α-cre resulted in early embryonic lethality. Because the switch in Mypt1 E23 splicing occurs postnatally, at least in the smooth muscle tissues examined to date, it seems unlikely that it is due to an effect on Mypt1 E23 splicing. We did not recover these embryos and so cannot comment on the cause of the early lethality, which is beyond the scope of this study. Prior studies of these same Tra2β floxed mice also observed early embryonic lethality in non-tissue-restricted homozygous mutants (23) and neonatal lethality in neural cell restricted homozygous mutants (24). The nature of the requirement for Tra2β in these cell types and its role in prenatal development of these tissues will require further study. It is reasonable to hypothesize that Tra2β will have different target exons depending on the level of expression and the affinity of cis-binding elements within the pre-mRNA, the cell type, and the stage of development.

The shift to the MYPT1 E23-skipped/LZ+ isoform in small intestinal smooth muscle of Tra2β-targeted mice resulted in increased sensitivity of the muscle to the relaxant effects of the cGMP analog 8-Br-cGMP. This supports the model, derived from association between tissue-specific and developmentally regulated MYPT1 LZ isoform expression and sensitivity to cGMP, in which the relative expression of the E23-skipped/Mypt1 LZ+ isoform determines the sensitivity of the smooth muscle to nitric oxide/cGMP-mediated relaxation (6, 7, 16, 46). The increased sensitivity to cGMP could reflect an inhibition of calcium flux or a reduction in calcium sensitivity of the myofilaments because of activation of myosin phosphatase. We did not observe any change in the calcium transients measured with a fluorescent indicator in the small intestinal smooth muscle of the SM22αCre:Tra2βfl/wt mice. This is consistent with the increased sensitivity to cGMP being due to an effect on MP activity, i.e. calcium desensitization. These findings are also consistent with a prior study showing that cGMP relaxes the mouse small intestinal smooth muscle through activation of MP, whereas in large intestinal smooth muscle, the relaxation is predominately via reduced calcium flux (47). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate a regulatory pathway that determines the sensitivity of smooth muscle to this signaling pathway. This increased sensitivity to cGMP-mediated relaxation ex vivo correlated with prolonged intestinal transit times. That switching of Mypt1 isoforms is causal in these changes in organ system function will require genetic manipulation of Mypt1 isoform expression in vivo. The circular muscle from the small intestine of these mice also generated greater force in response to the cholinergic agonist carbachol. This increased force production argues against a nonspecific effect of Cre expression on smooth muscle contractile function, and indeed, none was observed in SM22Cre positive mice. Currently we have no mechanistic explanation for this observation. A number of proteins in the agonist-mediated calcium sensitization pathway have isoforms generated by alternative splicing, including CPI-17 (reviewed in Ref. 48) and myosin phosphatase rhointeracting protein (49). More generally, as noted above, most proteins have isoforms generated by alternative splicing of exons. The patterns of expression and functional significance of these protein isoforms with respect to control of smooth muscle force production remains largely unknown. This study establishes Tra2β as a critical regulator of MYPT1 E23 splicing and sensitivity to cGMP in the phasic intestinal smooth muscle. How much of the diversity in smooth muscle contractile function is generated through alternative splicing of exons, and how much of this gene program is under the control of Tra2β? This will be best addressed through continued use of conditional gain and loss of function approaches coupled with higher throughput analyses of gene expression tailored to discovery of splice variants, as for example through deep sequencing of RNA derived from phenotypically diverse smooth muscle tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica Jenkins for maintaining the mouse colony and Dr. Kent Sanders (University of Nevada, Reno) for help with the calcium measurements.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 HL-66171 (to S. A. F.), GM103513 (to B. A. P.), and CMMC D7 (to B. W.).

- E23

- exon 23

- E7.5

- embryonic day 7.5

- RIP

- RNA immunoprecipitation

- Cch

- carbachol

- LZ

- leucine zipper

- cGMP

- cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)

- Mypt

- myosin phosphatase targeting subunit

- SR

- serine-arginine rich.

REFERENCES

- 1. Somlyo A. P., Somlyo A. V. (1994) Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature 372, 231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ogut O., Brozovich F. V. (2003) Regulation of force in vascular smooth muscle. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 35, 347–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fisher S. A. (2010) Vascular smooth muscle phenotypic diversity and function. Physiol. Genomics 42, 169–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartshorne D. J., Ito M., Erdödi F. (2004) Role of protein phosphatase type 1 in contractile functions. Myosin phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37211–37214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grassie M. E., Moffat L. D., Walsh M. P., MacDonald J. A. (2011) The myosin phosphatase targeting protein (MYPT) family. A regulated mechanism for achieving substrate specificity of the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase type 1δ. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 510, 147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khatri J. J., Joyce K. M., Brozovich F. V., Fisher S. A. (2001) Role of myosin phosphatase isoforms in cGMP-mediated smooth muscle relaxation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37250–37257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Payne M. C., Zhang H. Y., Prosdocimo T., Joyce K. M., Koga Y., Ikebe M., Fisher S. A. (2006) Myosin phosphatase isoform switching in vascular smooth muscle development. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 40, 274–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ts'ao C. H., Glagov S., Kelsey B. F. (1971) Structure of mammalian portal vein. Postnatal establishment of two mutually perpendicular medial muscle zones in the rat. Anat. Rec. 171, 457–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ljung B., Lundberg J. M., Dahlström A., Kjellstedt A. (1979) Structural and functional ontogenetic development of the rat portal vein after neonatal 6-hydroxydopamine treatment. Acta Physiol. Scand. 106, 271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ogut O., Brozovich F. V. (2000) Determinants of the contractile properties in the embryonic chicken gizzard and aorta. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C1722-C1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gabella G. (2002) Development of visceral smooth muscle. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 38, 1–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Payne M. C., Zhang H. Y., Shirasawa Y., Koga Y., Ikebe M., Benoit J. N., Fisher S. A. (2004) Dynamic changes in expression of myosin phosphatase in a model of portal hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286, H1801-H1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang H., Fisher S. A. (2007) Conditioning effect of blood flow on resistance artery smooth muscle myosin phosphatase. Circ. Res. 100, 730–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu Y., Zhang H., Gokina N., Mandala M., Sato O., Ikebe M., Osol G., Fisher S. A. (2008) Uterine artery myosin phosphatase isoform switching and increased sensitivity to SNP in a rat L-NAME model of hypertension of pregnancy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C564-C571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Surks H. K., Mochizuki N., Kasai Y., Georgescu S. P., Tang K. M., Ito M., Lincoln T. M., Mendelsohn M. E. (1999) Regulation of myosin phosphatase by a specific interaction with cGMP-dependent protein kinase Iα. Science 286, 1583–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang Q. Q., Fisher S. A., Brozovich F. V. (2004) Unzipping the role of myosin light chain phosphatase in smooth muscle cell relaxation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 597–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yuen S., Ogut O., Brozovich F. V. (2011) MYPT1 protein isoforms are differentially phosphorylated by protein kinase G. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37274–37279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gooding C., Smith C. W. (2008) Tropomyosin exons as models for alternative splicing. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 644, 27–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shukla S., Fisher S. A. (2008) Tra2β as a novel mediator of vascular smooth muscle diversification. Circ. Res. 103, 485–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matlin A. J., Clark F., Smith C. W. (2005) Understanding alternative splicing. Towards a cellular code. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 386–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Black D. L. (2003) Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 291–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Verhulst E. C., van de Zande L., Beukeboom L. W. (2010) Insect sex determination. It all evolves around transformer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 20, 376–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mende Y., Jakubik M., Riessland M., Schoenen F., Rossbach K., Kleinridders A., Köhler C., Buch T., Wirth B. (2010) Deficiency of the splicing factor Sfrs10 results in early embryonic lethality in mice and has no impact on full-length SMN/Smn splicing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2154–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grellscheid S., Dalgliesh C., Storbeck M., Best A., Liu Y., Jakubik M., Mende Y., Ehrmann I., Curk T., Rossbach K., Bourgeois C. F., Stévenin J., Grellscheid D., Jackson M. S., Wirth B., Elliott D. J. (2011) Identification of evolutionarily conserved exons as regulated targets for the splicing activator tra2β in development. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lepore J. J., Cheng L., Min Lu M., Mericko P. A., Morrisey E. E., Parmacek M. S. (2005) High-efficiency somatic mutagenesis in smooth muscle cells and cardiac myocytes in SM22α-Cre transgenic mice. Genesis. 41, 179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bhetwal B. P., An C. L., Fisher S. A., Perrino B. A. (2011) Regulation of basal LC20 phosphorylation by MYPT1 and CPI-17 in murine gastric antrum, gastric fundus, and proximal colon smooth muscles. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 23, e425-e436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Gorman W., Thomas B., Kwek K. Y., Furger A., Akoulitchev A. (2005) Analysis of U1 small nuclear RNA interaction with cyclin H. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36920–36925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qureshi S., Song J., Lee H. T., Koh S. D., Hennig G. W., Perrino B. A. (2010) CaM kinase II in colonic smooth muscle contributes to dysmotility in murine DSS-colitis. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 22, 186–195, e64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park K. J., Hennig G. W., Lee H. T., Spencer N. J., Ward S. M., Smith T. K., Sanders K. M. (2006) Spatial and temporal mapping of pacemaker activity in interstitial cells of Cajal in mouse ileum in situ. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C1411-C1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dirksen W. P., Vladic F., Fisher S. A. (2000) A myosin phosphatase targeting subunit isoform transition defines a smooth muscle developmental phenotypic switch. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 278, C589-C600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kalsotra A., Cooper T. A. (2011) Functional consequences of developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 715–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schiaffino S., Sandri M., Murgia M. (2007) Activity-dependent signaling pathways controlling muscle diversity and plasticity. Physiology 22, 269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2006) Signaling pathways in skeletal muscle remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 19–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Braun T., Gautel M. (2011) Transcriptional mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle differentiation, growth and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 349–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nayler O., Cap C., Stamm S. (1998) Human transformer-2-β gene (SFRS10). Complete nucleotide sequence, chromosomal localization, and generation of a tissue-specific isoform. Genomics 53, 191–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen X., Guo L., Lin W., Xu P. (2003) Expression of Tra2β isoforms is developmentally regulated in a tissue- and temporal-specific pattern. Cell Biol. Int. 27, 491–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Venables J. P., Bourgeois C. F., Dalgliesh C., Kister L., Stevenin J., Elliott D. J. (2005) Up-regulation of the ubiquitous alternative splicing factor Tra2β causes inclusion of a germ cell-specific exon. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 2289–2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stoilov P., Daoud R., Nayler O., Stamm S. (2004) Human tra2-β1 autoregulates its protein concentration by influencing alternative splicing of its pre-mRNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 509–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McKee A. E., Minet E., Stern C., Riahi S., Stiles C. D., Silver P. A. (2005) A genome-wide in situ hybridization map of RNA-binding proteins reveals anatomically restricted expression in the developing mouse brain. BMC Dev. Biol. 5, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hofmann Y., Lorson C. L., Stamm S., Androphy E. J., Wirth B. (2000) Htra2-β 1 stimulates an exonic splicing enhancer and can restore full-length SMN expression to survival motor neuron 2 (SMN2). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9618–9623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grellscheid S. N., Dalgliesh C., Rozanska A., Grellscheid D., Bourgeois C. F., Stévenin J., Elliott D. J. (2011) Molecular design of a splicing switch responsive to the RNA binding protein Tra2β. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 8092–8104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sciabica K. S., Hertel K. J. (2006) The splicing regulators Tra and Tra2 are unusually potent activators of pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 6612–6620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shirangi T. R., McKeown M. (2007) Sex in flies. What “body-mind” dichotomy? Dev. Biol. 306, 10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tacke R., Tohyama M., Ogawa S., Manley J. L. (1998) Human Tra2 proteins are sequence-specific activators of pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 93, 139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cléry A., Jayne S., Benderska N., Dominguez C., Stamm S., Allain F. H. (2011) Molecular basis of purine-rich RNA recognition by the human SR-like protein Tra2-β1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Karim S. M., Rhee A. Y., Given A. M., Faulx M. D., Hoit B. D., Brozovich F. V. (2004) Vascular reactivity in heart failure. Role of myosin light chain phosphatase. Circ. Res. 95, 612–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Frei E., Huster M., Smital P., Schlossmann J., Hofmann F., Wegener J. W. (2009) Calcium-dependent and calcium-independent inhibition of contraction by cGMP/cGKI in intestinal smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 297, G834-G839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eto M. (2009) Regulation of cellular protein phosphatase-1 (PP1) by phosphorylation of the CPI-17 family, C-kinase-activated PP1 inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35273–35277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Surks H. K., Richards C. T., Mendelsohn M. E. (2003) Myosin phosphatase-Rho interacting protein. A new member of the myosin phosphatase complex that directly binds RhoA. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51484–51493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]