Abstract

Human genetic defects in the growth hormone (GH)–IGF-I axis affecting the IGF system present with growth failure as their principal clinical feature. This is usually associated with GH insensitivity (GHI) presenting in childhood as severe or mild short stature. Dysmorphic features and metabolic abnormalities may also be present. The field of GHI due to mutations affecting GH action has evolved rapidly since the first description of the extreme phenotype related to homozygous GH receptor (GHR) mutations in 1966. A continuum of genetic, phenotypic, and biochemical abnormalities can be defined associated with clinically relevant defects in linear growth. The mechanisms of the GH–IGF-I axis in the regulation of normal human growth is discussed followed by descriptions of mutations in GHR, STAT5B, IGF-I, IGFALS, IGF1R, and GH1 defects causing bio-inactive GH or anti-GH antibodies. These GH–IGF-I axis defects are associated with a range of clinical, and hormonal characteristics. An up-dated approach to the clinical assessment of the patient with GHI focusing on investigation of the GH–IGF-I axis and relevant molecular studies contributing to the identification of causative genetic defects is also discussed.

Keywords: genetic defects, childhood linear growth, growth hormone insensitivity, growth hormone–IGF-I axis mutations

Introduction

Human genetic defects in the growth hormone (GH) – IGF-I axis causing disruption of the IGF system are usually associated with GH insensitivity (GHI) due to the essential role of this system in the regulation of GH action. GHI (OMIM #262500 and #245590) was first described in a pediatric setting by Laron et al. (1966), with the description of extreme growth failure in siblings in a consanguineous Jewish family who had the phenotype of hypopituitarism with high serum GH concentrations (Laron, 2004). For many years this disorder was referred to as Laron syndrome and was eventually shown to be caused by a defect in the GH receptor (GHR) resulting in deficient binding of 125I-GH to GHRs prepared from the patients’ liver membranes (Eshet et al., 1984). This striking but very rare phenotype, which was also untreatable at that time, became synonymous with the diagnosis of GHI, a perception that remained largely unchallenged for over 20 years. In the late 1980s two pivotal developments brought key changes to the field. The first was the synthesis and availability of recombinant human IGF-I for therapy (Laron et al., 1988; Walker et al., 1991), and the second was the advent of molecular techniques, which led to the cloning, and characterization of the human GHR, thus initiating the understanding of the pathophysiology of GHI (Amselem et al., 1989; Godowski et al., 1989). The subsequent study of genetic abnormalities in the GH–IGF axis has provided invaluable information on the physiology of human linear growth.

In medicine, scientific advances often move more rapidly than the practices of clinicians, who may remain attached to the recognized, and trusted view of a certain disorder, particularly if it is rare. This has been the case with GHI, which is now known not to be a single entity, but a broad diagnostic category comprising a range of defects affecting the function of the IGF system. These abnormalities may involve genes coding for proteins that regulate GH binding or signal transduction and IGF-I synthesis, transport, or action and are associated with a variety of phenotypes and biochemical abnormalities presenting to the pediatric endocrinologist. This review will describe the individual mutations and discuss the investigation of the child with short stature who has features suggesting the presence of a causative genetic defect.

Previous reviews have often described the characteristics of the extreme phenotype (Rosenfeld et al., 1994; Laron, 2004; Savage et al., 2006), however we concentrate on defects illustrating the range of phenotypes. The article discusses the genetic causes of GHI, also referred to as primary IGF deficiency. We aim also to up-date and orientate clinicians in the appropriate diagnostic approach to children with growth failure.

The GH–IGF Axis in Human Growth

Physiology of GH and the IGF-I system in relation to linear growth

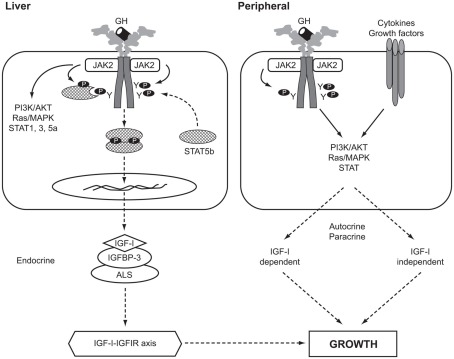

The actions of GH are mediated by a combination of components of the IGF system, including IGF-I, IGF-binding proteins (IGFBPs), the IGF-I receptor (IGFIR), and IGF-independent effects through direct GH action. A diagram of the GH–IGF axis is shown in Figure 1. The original “somatomedin hypothesis” proposed that GH binding to its receptor stimulated IGF-I production, which independently affected growth (Salmon and Daughaday, 1957). Green et al. (1985) then proposed the “dual effector hypothesis” suggesting that GH regulates the expression of locally produced IGF-I, which then acts in an autocrine/paracrine manner. Expression of the IGF1 gene was found in multiple tissues throughout embryonic and post-natal development (Roberts et al., 1987; Han et al., 1988) and injection of GH into hypophysectomized rats increased IGF1 mRNA in numerous non-hepatic tissues (Lowe et al., 1987, 1988). Direct injection of GH into the cartilage growth plate of hypophysectomized rats also resulted in significantly increased longitudinal bone growth (Isaksson et al., 1982). These and other studies suggested that GH has local effects, independent of those mediated by circulating “endocrine” IGF-I. This hypothesis was extended by Isaksson and others (Nilsson et al., 1986; Isaksson et al., 1987) who demonstrated that GH stimulated differentiation of preadipocytes and chondrocytes in the growth plate, while IGF-I stimulated their clonal expansion.

Figure 1.

The GH–IGF-I axis in human growth. Solid arrows, activation processes; dashed arrows, translocation processes. P, phosphorylated residue; Y, tyrosine; AKT, v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog, also known as PKB, protein kinase B; ALS, acid-labile subunit; IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein-3; IGFIR, IGF-I receptor; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

In a comprehensive review of the roles of GH and IGF-I, Le Roith et al. (2001) presented a revised somatomedin hypothesis, taking account of gene deletion experiments in mice that questioned the role of liver IGF-I and its circulating endocrine form in controlling post-natal growth and development (Sjögren et al., 1999; Yakar et al., 1999). Liver-specific Igf1 knock-out mice continued to grow normally despite reduction in circulating IGF-I, indicating that locally produced IGF-I was an important growth mediator (Yakar et al., 1999). Le Roith has recently modified his conclusions following data showing that when the hepatic Igf1 transgene was able to elevate serum IGF-I levels growth was largely restored (Wu et al., 2009). Kaplan and Cohen (2007) further proposed the apparent paradox that GH exerts its effects through IGFs, some of which oppose the known actions of GH.

Studies using Igf1 knock-out mouse models have shown that GH stimulates bone growth by IGF-I-independent and IGF-I-dependent mechanisms. Some 75% of serum IGF-I is liver-derived, while the remainder originates from non-hepatic tissues (Sjögren et al., 1999; Yakar et al., 1999). In addition, serum levels of the acid-labile subunit (ALS) and IGFBP-3 are important in maintaining circulating IGF-I (Ohlsson et al., 2009). The importance of ALS was shown in the Igfals knock-out mouse model (Ueki et al., 2000) and by Domené et al. (2004) who reported the first homozygous mutation in human IGFALS causing severe IGF-I deficiency.

Effects of human GH–IGF axis mutations on linear growth

Normal GH secretion and the functional integrity of the IGF system are essential for normal linear growth. Defects that have been identified to cause impaired growth are shown in Table 1. A summary of phenotypic and biochemical features in the range of GH–IGF-I axis defects is given in Table 2. Human pre-natal growth is regulated principally by nutritional supplies, which influence fetal IGF-I and, perhaps, IGF-II (Derr et al., 2011). Targeted disruption of either Igf1 or Igf2 in mice led to 40% reduction in fetal growth (Milward et al., 2004). The importance of normal IGF-I production in humans was confirmed by the pre-natal growth failure reported in patients with IGF1 mutations (Jin et al., 2008; Rowlinson et al., 2008). IGF-I action is also essential as demonstrated by IGFIR rodent knock-out studies (Igf1r−/−) resulting in 55% reduction in fetal size (Milward et al., 2004), an effect also present in humans with mutations of IGF1R (Barclay et al., 2010). Post-natal growth may be disrupted by mutations that disturb the functional integrity of the cascade of GH–GHR interaction, GH signal transduction, and IGF-I production, transport, and action (Rosenfeld et al., 1994; Savage et al., 2006). In states of GHI resulting from impaired GH–GHR function, IGF-I deficiency is the cardinal biochemical feature. In mutations specifically involving the IGF1 or IGF1R, GHR function remains intact resulting in possible accentuation of IGF-I-independent GH effects and causing insulin resistance (Rowlinson et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Genetic defects involving the IGF system and disrupting linear growth.

| Defects of the GH–IGF-I axis |

|---|

| GH receptor defects |

| Extracellular mutations |

| Transmembrane mutations |

| Intracellular mutations |

| GH signal transduction defects (STAT5b) |

| Mutations of SHP-2 (encoded by PTPN11) |

| IGF1 mutations or deletions |

| Defects causing IGF-I deficiency |

| Bio-inactive IGF-I |

| Acid-labile subunit gene defects |

| IGF-I receptor (IGFIR) gene mutations |

| GH neutralizing antibodies in patients with GH gene deletion |

PTPN11, protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 11; SHP-2, Src-homology region 2-domain phosphatase-2; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

Table 2.

Summary of phenotypic and biochemical features in the range of GH–IGF-I axis defects.

| Gene defect phenotype | GHR | STAT5b | PTPN11 | IGF-I | IGFALS | IGFIR | Bio-inactive GH | GH1 with anti-GH antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe growth failure | +/− | + | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Mild growth failure | −/+ | − | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| Mid-face hypoplasia | +/− | +/− | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Other facial dysmorphism | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| Deafness | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Microcephaly | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Intellectual delay | − | − | −/+ | + | − | +/− | − | − |

| Puberty delay | +/− | +/− | +/− | − | + | − | − | − |

| Immune deficiency | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hypoglycemia | + | −/+ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hyperinsulinemia | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| IGF-I deficiency | + | + | −/+ | +/− | + | − | + | + |

| IGFBP-3 deficiency | + | + | −/+ | − | + | − | + | + |

| ALS deficiency | + | + | −/+ | − | + | − | + | + |

| GH excess | + | + | − | +/− | + | − | − | − |

| GHBP deficiency | +/− | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations | + | + | − | + | + | − | −/+ | + |

| Heterozygous mutations | − | − | + | − | − | + | +/− | _ |

+, positive; −, negative; +/−, predominantly positive; −/+, predominantly negative; ALS, acid-labile subunit; IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein-3; GHBP, growth hormone binding protein.

Molecular Defects Disrupting the IGF System and Causing Growth Failure

The GH receptor

The GHR protein mediates the effects of GH on linear growth and metabolism. It is present ubiquitously, being most abundantly expressed in the liver (Chia et al., 2010) and is composed of a large extracellular domain involved in GH binding and GHR dimerization, a single transmembrane domain that anchors the receptor to the cell surface and an intracellular domain involved in GH signaling. GH binding activates its receptor by inducing a conformational change in a pre-existing GHR dimer (Adams et al., 2000; Wang and Jiang, 2005), which promotes the binding of Janus tyrosine kinase 2 (JAK2) to a proline-rich Box 1 region located in the proximal intracellular portion of the GHR (Fowden, 2003) and initiates intracellular signaling.

Since 1966, more than 250 patients with genetic GHI have been identified worldwide (Lupu et al., 2001; Savage et al., 2006). The most severe phenotype was described by Laron et al., 1966; OMIM #262500; Laron, 2004). Most GHI cases have autosomal recessive inheritance and in the vast majority a molecular defect has been identified involving homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations (Lupu et al., 2001). Over 70 mutations of GHR have been identified to date ranging from deletions to point mutations including missense, nonsense, and splice mutations (Woods et al., 1996a; Lupu et al., 2001; Savage et al., 2006). Among the defects causing aberrant GHR splicing, an intronic base change leading to the activation of a pseudoexon sequence and insertion of 36 new amino acids within the receptor extracellular domain was first reported in a consanguineous Pakistani family with mild GHI (Metherell et al., 2001). This mutation leads to recognition of the pseudoexon and inclusion of an additional 108 bases between exons 6 and 7 leading to impaired function of the mutant protein (Maamra et al., 2006). Intronic mutations resulting in pseudoexon activation are rare in genetic diseases (Akker et al., 2007). The phenotypes occurring with this mutation range from severe to mild growth failure (David et al., 2007). A mild phenotype of GHI is also associated with heterozygous GHR mutations causing a dominant-negative effect (Ayling et al., 1997; Iida et al., 1998). These splice site mutations (c.876 − 1G > C) and (c.945 + 1G > A) form heterodimers with the wild-type GHR and exert a dominant-negative effect on the normal protein.

Differing phenotypes within the same family may also occur, as reported with one sibling having extreme growth failure (adult height –8.7 SDS) and a second a milder phenotype (adult height –6.0 SDS; Milward et al., 2004). Both siblings had the same homozygous 22-bp deletion in the cytoplasmic domain of the GHR, resulting in a frameshift and premature stop codon The resultant GHR was truncated at amino acid 449 (GHR1-449) after Box 1, the JAK2 binding domain of the receptor, and functional studies in HEK293 and Chinese hamster ovary cells showed a selective loss of STAT5 signaling in cells expressing GHR1-449 (Milward et al., 2004).

A mild phenotype was also reported in two patients with compound heterozygous mutations (Fang et al., 2007). Both had undisputed GHI but functional studies suggested incomplete GHR defects that determined the phenotype by an additive effect of each heterozygous mutation. A recent report described a child and his mother with short stature and elevated GH binding protein (GHBP) levels associated with a novel heterozygous C → A transversion at position c.785-3 at the acceptor site of intron 7 (Aalbers et al., 2009).

STAT5B mutations

STAT5B mutations present a characteristic phenotype combining GHI and immunodeficiency (OMIM #245590). The binding of GH to the GHR activates signaling cascades that include a number of STAT pathways (STAT1, STAT3, STAT5a, and STAT5b). Molecular defects in GH signal transduction pathways appear to be very rare but recent identification of human STAT5B mutations causing severe growth failure, IGF-I deficiency, and GHI, demonstrated that STAT5b signaling is critical for GH-induced IGF-I production and normal linear growth (Rosenfeld et al., 2007).

In 2003, the first STAT5B mutation was identified in a 16-year-old female from a consanguineous Argentine family (Kofoed et al., 2003). Subsequent reports confirmed that birth weight in affected patients is generally normal, but is followed by severe post-natal growth failure, with resistance to GH therapy (Hwa et al., 2005, 2007; Bernasconi et al., 2006; Vidarsdottir et al., 2006). The biochemical profile shows normal or elevated GH secretion, normal GHBP values, and severe deficiencies of IGF-I, IGFBP-3, and ALS which fail to increase on GH stimulation (Hwa et al., 2005, 2007; Bernasconi et al., 2006; Vidarsdottir et al., 2006). A key feature in all but one reported case (Vidarsdottir et al., 2006) was immune dysfunction. In several patients, repeated pulmonary infections occurred from infancy, including episodes of lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (Kofoed et al., 2003; Hwa et al., 2007), a condition associated with autoimmune disease. Interestingly, interferon-gamma (IFNγ), a cytokine that signals predominantly through the STAT1 pathway, could also up-regulate IGF-I expression but only when STAT5b was present and fully functional (Hwa et al., 2004).

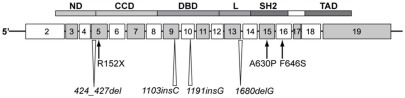

The unusual combination of GHI and immune dysfunction in the patient from Argentina led to the identification of a homozygous, missense, mutation in Exon 15 of the STAT5B gene (Kofoed et al., 2003). The single G to C transversion at nucleotide 1888 of the STAT5B mRNA resulted in an Ala630 (GCT) to Pro (CCT) substitution. Homology modeling with the solved structure of STAT1 (Chen et al., 1998) showed that this mutation was within the critical SH2 domain, a well-characterized, conserved, regulatory module that functions by interacting with high affinity to phosphotyrosine-containing target peptides. The Ala630Pro (A630P) substitution was predicted to cause loss of thermodynamic stability as well as aberrant folding and aggregation of the mutant STAT5b protein (Chia et al., 2006). It is of note that pathogenic mutations in the SH2 domain of a number of cytoplasmic signaling peptides, including STAT1, have been associated with immuno-deficiencies, but none, except STAT5b, has been associated with severe growth retardation and IGF-I deficiency. Details of the human STAT5B mutations reported to date are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Homozygous STAT5B mutations identified in patients with GH insensitivity, IGF-I deficient, severely growth retarded, and immune compromised. Schematic of the STAT5b protein modular structure encoded by corresponding exons is as indicated. CCD, coiled-coiled domain; DBD, DNA binding domain; L, linker; ND, N-terminal domain; SH2, Src-homology 2-domain; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TAD, transactivation domain.

Since the first report, six other human STAT5B mutations have been documented, with several found in siblings (Pugliese-Pires et al., 2010). In contrast to mutations in IGF1 (see below), brain development, and cognitive functions appeared to be normal. The seven STAT5B mutations, located in different domains of the STAT5b protein, comprise two missense mutations, p.A630P and p.F646S, a nonsense mutation, p.R152X, single nucleotide insertions, c.1191insG and c.1103insC, nucleotide deletions c.1680delG and c.424_427del. The insertion/deletion mutations result in frameshifts and truncation of the STAT5b protein. All reported mutations were homozygous and autosomal recessive. The phenotype of STAT5b-deficient patients includes profound short stature and delayed puberty in the older subjects. The only patient without obvious immune deficiency, the first reported male proband, contracted hemorrhagic varicella at 16 years of age and had congenital ichthyosis, but, otherwise, appeared healthy (Vidarsdottir et al., 2006) One other patient was diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis at the young age of 2 years. Immunological evaluations reported for one of the patients carrying p.R152X, indicated lymphopenia and abnormally low regulatory T cells, similar to the proband carrying the p.A630P mutation (Cohen et al., 2006). It is also of note that STAT5b deficiency was associated with abnormally high levels of circulating prolactin in six of the cases. It remains unclear whether the hyperprolactinemia is a direct or indirect consequence of STAT5B mutations.

IGF1 mutations

The first human IGF1 defect was described by Woods et al., 1996b; OMIM #608747). Features of patients with IGF-I defects are shown in Table 3. The first patient, a male, was born by Caesarian section because of poor fetal growth. Placental weight was diminished (350 g) and he had severe intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) with a birth weight of 1.4 kg (–3.9 SDS), birth length of 37.8 cm (–5.4 SDS), and microcephaly (head circumference 27 cm, –4.9 SDS). His growth failure worsened post-natally and at 15.8 years, his height was 119.1 cm (–6.9 SDS), and his weight was 23.0 kg (–6.5 SDS). He had delayed psychomotor development and sensorineural deafness. During adolescence he became insulin resistant. No IGF-I was detected in the serum even after 4 days of stimulation with GH in an IGF-I generation test (IGFGT). Spontaneous 12-h GH secretion showed abnormally elevated baseline and peaks. ALS and IGFBP-3 values were normal. Molecular analysis revealed a homozygous deletion of exons 4 and 5 of the IGF1 gene. If translated, the resulting protein would be severely truncated, lacking 45 of the 70 IGF-I amino acids (Woods et al., 1996b). At 16.1 years (bone age, 14.2 years), recombinant IGF-I therapy was initiated and resulted in beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity, body composition, bone size, and linear growth (Camacho-Hübner et al., 1999; Woods et al., 2000).

Table 3.

Characteristics of six cases with IGF1 defects.

| Woods et al. (1996b) | Bonapace et al. (2003) | Walenkamp et al. (2005) | Netchine et al. (2009) | van Duyvenvoorde et al. (2010) | van Duyvenvoorde et al. (2010) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBSERVATION | ||||||

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male |

| Consanguinity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Birth weight (SDS/g) | −3.9/1400 | −4.0/1480 | −2.5/1420 | −2.5/2350 | −2.9/2300 | −1.2/3300 |

| Birth length (SDS/cm) | −5.4/37.8 | −6.5/41 | −3/39 | −3.7/44 | −3.8/44.0 | −1.0/50.0 |

| Cranial circumference (SDS/cm) | −4.9/27 | −7.5/26.5 | −8.0/44.2 | −2.5/32 | −2.4/47.8 | −1.6/49.0 |

| Growth (SDS) | −6.9 at 16 years | −6.2 at 1.6 years | −9 at 55 years | −4.5 at 3 years | −4.1 at 8.2 years | −4.6 at 6.2 years |

| Microcephaly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mild |

| Development delay | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mild | Yes | No |

| Deafness | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Adiposity | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| HORMONAL EVALUATION | ||||||

| IGF-I levels | Undetectable | 1.0 ng/mL | +7.3 SDS | Variable | −2.3 SDS | −2.6 SDS |

| IGFBP-3 levels | 3.3 mg/L | 3.6 mg/L | 1.98 mg/L (+0.1 SDS) | 4.3 mg/L | +1.2 SDS | +0.1 SDS |

| Molecular defect | Hom p.? (Del ex 4–5) | Hom p.? ** | Hom p.V44M | Hom p.R36Q | Het c.243−246dupCAGC | Het c.243−246dupCAGC |

| IGF1R affinity | Zero | Not studied | Extremely low | Partially reduced | Not studied | Not studied |

IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein-3; SDS, standard deviation score; Hom, homozygous defect; Het, single heterozygous defect.

**This mutation is localized within the polyadenylation site and alters mRNA splicing. The 3′ end of the resulting aberrant IGF-I transcript contains a partial sequence from the downstream gene KIAA0537.

Features of IUGR, microcephaly, retarded intellectual development and severe post-natal growth failure were present in the other cases with homozygous IGF1 mutations (Bonapace et al., 2003; Walenkamp et al., 2005; Netchine et al., 2009). Deafness was present in all the cases except the child with the mildest phenotype (Netchine et al., 2009). The microcephaly shown by these patients, is a cardinal feature of the phenotype and allows a distinction with Russell–Silver syndrome patients, who have a relative macrocephaly (Netchine et al., 2007). There has been some variation of serum IGF-I levels in the reported IGF1 mutation cases. The third case to be described (Walenkamp et al., 2005) shared an identical clinical phenotype with the index case (Woods et al., 1996b), and had a younger brother with similar features who died in childhood. This patient had a serum IGF-I level that was significantly increased (+7.3 SDS), explained by the fact that the patient’s homozygous missense mutation of IGF1, a G → A nucleotide substitution at position 274, changing valine at position 44 in the A domain of the mature IGF-I protein to methionine (p.V44M), resulted in a recombinant protein (IGF1 V44M) which allowed normal binding to IGFBP-3 but decreased affinity (90-fold) for its receptor, IGF1R. This patient therefore had bio-inactive IGF-I caused by an IGF1 mutation. Serum IGF-I levels in the fourth patient who had a relatively mild phenotype were also variable and not severely decreased (Netchine et al., 2009). In all reported subjects serum IGFBP-3 and ALS levels have been normal or elevated.

Genetic analysis of IGF1 in the second case (Bonapace et al., 2003) showed a homozygous T → A transversion in exon 6, that would result if translated into an altered E domain of the IGF-I precursor. It has been argued that this variant may be a polymorphism and thus not causative of the patient’s phenotype, which was nevertheless strikingly similar to the other cases. In the patient with the mild phenotype, sequencing of IGF1 revealed a homozygous missense mutation resulting in the change of a highly conserved arginine located in the C domain of the protein into a glutamine (p.R36Q). Affinity for the IGF1R decreased two to threefold, resulting in decreased IGF1R autophosphorylation. This partially diminished IGF-I activity had marked consequences for fetal growth and development (Netchine et al., 2009).

IGFALS mutations

IGFALS mutations are associated with GHI and severe ALS and IGF-I deficiencies (OMIM #601489). The ALS is a soluble protein and member of the leucine-rich repeat family, and is expressed by hepatocytes and secreted into the blood stream (Leong et al., 1992). GH is the main inducer of ALS synthesis (Ooi et al., 1997) and in the circulation ALS can be found free or bound to IGF-I or -2 and IGFBP-3 or -5, to form a ternary complex (Baxter, 1994), which prevents IGFs, free or bound to IGFBPs, from leaving the circulation, thus prolonging their half-lives and decreasing their availability at a tissue level. ALS is encoded by the IGFALS, located on chromosome 16p13.3 and spanning 3.3 Kb. Inactivation of the IGFALS in mice results in absence of circulating ALS but only modest growth failure despite marked reduction of serum IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels (Ueki et al., 2000).

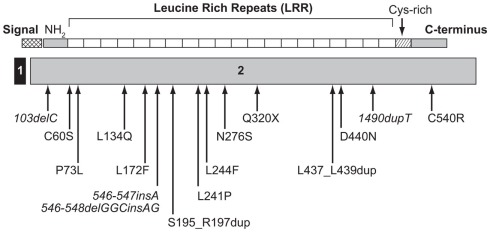

The first patient with a homozygous mutation of IGFALS was reported by Domené et al. (2004) and presented a new combination of genetic, biochemical, and phenotypic data. The most striking feature of this genetic defect causing GHI was a mis-match between extreme deficiencies of circulating IGF-I, IGFBP-3, and ALS and relatively mild growth failure, even leading to a normal adult height in some patients (Domené et al., 2007). A recent review of published cases confirms these features (Domené et al., 2009). Sixteen different mutations of the human IGFALS gene (Figure 3) have been identified in 21 cases (Domené et al., 2009). Eleven were homozygous and six were compound heterozygous with autosomal recessive inheritance. IGFALS mutations have included missense and nonsense mutations, deletions, duplications, and insertions resulting in frameshift and premature stop codons and in-frame duplication mutations leading to insertion of extra amino acid residues (Domené et al., 2009). In all cases, there was extreme deficiency of circulating ALS, with inability to form the ternary complex (Domené et al., 2009; David et al., 2010). Whereas circulating levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 are severely reduced, due to their rapid clearance, local production of IGF-I in peripheral tissues, notably the growth plate, appears to be preserved or even increased due to up-regulation of GH secretion (Domené et al., 2004). Insulin resistance, with hyperinsulinemia and low IGFBP-1, has also been described in these patients (Heath et al., 2008; Domené et al., 2009).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the ALS protein indicating the location of identified human IGFALS mutations. The IGFALS is composed of two exons, with five amino residues of the ALS signal peptide encoded by exon 1 and the first five amino residues of exon 2 and the remainder of the ALS protein encoded by exon 2. ALS, acid-labile subunit; NH2, N-terminal region.

Recently attention has focused on the possible effect of heterozygous IGFALS mutations on growth. An analysis of 21 patients with homozygous or compound heterozygous IGFALS mutations and their family members who were either heterozygous carriers or homozygous wild-type normal has recently been published (Fofanova-Gambetti et al., 2010). Mean height SDS was –2.31 ± 0.87 in the homozygous IGFALS mutation patients. Analyses within individual families showed that heterozygosity for IGFALS mutations resulted in approximately 1.0 SD height loss in comparison with wild-type, whereas homozygosity or compound heterozygosity resulted in a further loss of 1.0–1.5 SD, suggestive of a gene-dosage effect.

IGFIR mutations

IGFIR mutations are characterized by IGF-I resistance causing impaired fetal and post-natal growth (OMIM #270450). The IGF1R is a transmembrane receptor and belongs to the insulin receptor family, which includes the IGF2R and insulin receptor. The IGFIR is expressed widely and binds IGF-I and -2 with high affinity, mediating their biological actions by activating a complex intracellular signaling cascade leading to the transcription of IGF target genes. The IGF1R gene is located on chromosome 15q26.3 and spans 315 kb.

Mutations in IGF1R were first reported by Abuzzahab et al. (2003) following analysis of DNA from cohorts of children with short stature and unexplained IUGR. The first child was a compound heterozygote for point mutations in exon 2 of the IGFIR gene that altered the amino acid sequence to p.R108Q in one allele and p.K115N in the other. She had a birth weight of –3.5 SD with childhood short stature and an adult height of –4.8 SD. The second patient, a boy, had a heterozygous nonsense mutation (p.R59X) that reduced the number of IGF1Rs on fibroblasts. He also had low birth weight (–3.5 SD) and birth length (–5.8 SD) with microcephaly and post-natal growth failure (height –3.8 SD) at age 14 months and some additional dysmorphic features. Serum IGF-I levels were normal or elevated in both patients and GH secretion was within normal limits.

There have been several reports of familial short stature due to IGF1R mutations. A heterozygous mutation in the cleavage site of the proreceptor of IGF1R was reported in a 6-year-old Japanese girl and her mother (Kawashima et al., 2005) and the group of Wit in Leiden described a mother and daughter with a heterozygous missense mutation in the intracellular part of the IGF1R (Walenkamp et al., 2006). A 9-year-old male patient (height –3.6 SD), his sister (height –1.94 SD and IUGR), and his mother (height –4.6 SDS) carried the same IGF1R mutation which was a novel heterozygous 19-nucleotide duplication in exon 18 (Fang et al., 2009). Functional studies in primary dermal fibroblasts derived from the patient and family members indicated that IGF1R mRNA expressed from the mutant allele was degraded through the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway resulting in reduced amount of wild-type IGF1R protein and, subsequently, diminished activation of the IGF1R pathway. A further female child was reported with a heterozygous missense mutation in the highly conserved N-terminal fibronectin type III domain of IGF1R with functional studies demonstrating impaired post-receptor IGF-I signaling (Inagaki et al., 2007).

GH1 mutations causing biologically inactive GH

Certain GH1 mutations cause biologically inactive GH resulting in a form of GHI (OMIM #262650). A syndrome of biologically inactive GH causing GHI and short stature was first described by Kowarski et al. (1978). The molecular basis of this apparently rare cause of GHI was clarified by Takahashi et al. (1996, 1997) who reported two cases with heterozygous mutations in the GH1 gene. The first case was a boy with severe short stature (height −6.1 SD) who had increased immunoassayable GH and IGF-I deficiency, which responded, as did his growth, to exogenous hGH therapy. The mutation was a single-base missense substitution (p.R77G) in exon 4 of the GH1. However his normal stature father also had the same mutation. Functional studies demonstrated that the mutant GH molecule had higher binding affinity for the GHR and inhibited its activation by wild-type GH in a dominant-negative fashion, thus impairing GH bioactivity. The second case was a girl with similar endocrine features and short stature associated with a heterozygous single-base change (A → G) causing a p.D112G substitution in GH1. More recently, a child with short stature (height −3.6 SD at age 9 years) from a consanguineous Serbian family was reported to have a homozygous missense mutation, C53S, of GH1 leading to the absence of the disulfide bridge Cys-53 to Cys-165 in the GH molecule (Besson et al., 2005).

GH1 gene deletions (type IA GH deficiency) with anti-GH antibodies

A rare form of GHI occurs due to acquired GH-inhibiting antibodies in a category of children with familial isolated GH deficiency (IGHD; OMIM #262400; Cogan and Phillips, 2006). Autosomal recessive IGHD, caused by gross deletions of the GH1, result in severe IGHD (Type IA) with undetectable GH secretion (Phillips et al., 1981). Such patients have severe post-natal growth failure with height usually <−4.5 SD. Most of the GH1 deletions are 6.7, 7.0, or 7.6 kb in length, although several of 45 kb have been reported (Proctor et al., 1998). Microdeletions and frameshift mutations have also been reported (Baumann, 2002; Cogan and Phillips, 2006; Alatzoglou and Dattani, 2010). IGHD patients with homozygous deletions of the GH1 gene frequently develop anti-GH antibodies during treatment with GH due to immunological intolerance. However, variability of both antibody formation and response to GH therapy may occur, even within families (Proctor et al., 1998). Rare homozygous microdeletions and single base-pair substitutions in the GH1 coding region have also resulted in anti-GH antibody formation during GH therapy. The formation of anti-GH antibodies neutralizes the growth response to GH therapy, resulting in a state of GHI associated with severe short stature. Such patients may respond to therapy with recombinant human IGF-I, which becomes the only effective management for their growth failure (Riedl and Frisch, 2006).

The Investigation of GH–IGF-I Axis Mutations

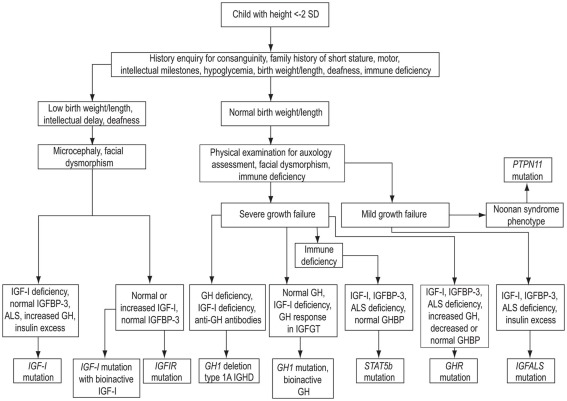

The evaluation of a child with short stature and a possible GH–IGF-I axis mutation should comply with the classical paradigm of clinical assessment followed by general (i.e., non-endocrine) investigations, hormonal assessment, and appropriate genetic analyses. An algorithm showing key steps in the investigation of genetic GH–IGF-I axis defects is shown in Figure 4. As advances in molecular endocrinology related to growth disorders progress, the crucial importance of detailed phenotypic evaluation and documentation becomes increasingly important. The urge to obtain a possible molecular diagnosis at the onset of the investigations should be resisted until detailed clinical and endocrine evaluation has been performed. Clinical assessment should include enquiries about family history of growth disturbance, consanguinity, birth weight and length, and recurrent infections (Savage et al., 2010). Examination should specifically assess the presence of possible facial dysmorphic features and microcephaly in addition to anthropometric evaluation (Cohen et al., 2008).

Figure 4.

Algorithm showing key steps in the investigation of genetic GH–IGF-I axis defects. SD, standard deviation; IGHD, isolated growth hormone deficiency; ALS, acid-labile subunit; IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein-3.

Investigations of the GH–IGF-I axis

Investigations of the GH–IGF-I axis consist of determination of GH secretion and exploration of the IGF system. A GH provocation test is recommended unless the child has normal auxology or a basal IGF-I level above the mean for age (Cohen et al., 2008). In a child with clinical criteria of GHD, a peak GH level of <10 ng/mL has traditionally been used to support this diagnosis (Growth Hormone Research Society, 2000). Basal IGF-I levels should also be determined, although these may be influenced by factors such as age, nutrition, chronic illness, and puberty. In the initial assessment, IGFBP-3 adds little, except in children under 3 years of age, where low IGFBP-3 is helpful in the diagnosis of GHD (Cianfarani et al., 2005). Reliable assay performance and appropriate normative data (Juul et al., 1994, 1995) are essential for the use of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 in clinical practice, and adjustment for sex, age, puberty, and nutritional status is recommended.

A diagnosis of GHI follows from the demonstration of abnormal auxology, normal GH secretion, and IGF-I deficiency. However, the pathogenesis will not have been elucidated from these investigations. The nature of the defect can often be defined by additional measurement of IGFBP-3, ALS, and GHBP (Savage et al., 2010). In GHR defects IGF-I, IGFBP-3, and ALS are decreased (Burren et al., 1999), although the degree of abnormality can vary with the type of mutation, which also influences GHBP levels. GH secretion is elevated in most patients with severe IGF-I deficiency.

The IGF-I generation test

The principle behind the design of the IGFGT was that repeated injections of GH induce measurable increases of IGF-I, IGFBP-3, and ALS secretion. However, in GH deficiency patients, the degree of IGF-I response did not convincingly predict the growth response to GH therapy (Rosenfeld et al., 1981). Normative data were not established and the test is not used for this purpose. Interest in the IGFGT was renewed when molecular evidence of GHI was demonstrated and subjects were selected for rhIGF-I therapy. Criteria for diagnosis of GHI were defined as: failure to increase IGF-I and IGFBP-3 by >15 and 400 ng/mL, respectively (Blum et al., 1994; Woods et al., 1997). However, as the spectrum of GHI disorders expanded, these criteria are now too strict for mildly affected subjects and even in severe GHI patients, post-GH increases of IGF-I ranged from <20 to 58 ng/mL and of IGFBP-3 from 95 to 1762 ng/mL (Rosenfeld, 2005). Attempts to refine the IGFGT for the diagnosis of milder GHI have demonstrated that patients with idiopathic short stature produced a subnormal response (Selva et al., 2003) and subjects with IGF-I deficiency and normal GH secretion also had subnormal ability to generate IGF-I (Midyett et al., 2010). However, additional sensitivity for the diagnosis of GH resistance was not seen with a low-dose GH protocol (Buckway et al., 2001). A lack of reproducibility of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 responses in the IGFGT has also been reported (Jorge et al., 2002). For this reason genetic analysis and assessment of the growth response to GH therapy, especially in patients without the classical GHI phenotype, should be performed to confirm GH resistance. The principal value of the IGFGT is the confirmation of extreme or severe GHI (Rosenfeld et al., 1994; Woods et al., 1997).

Genetic investigations

The discussions above have indicated that genetic mutations in the GH–IGF-I axis make a major contribution to the pathogenesis of GHI. Following clinical and biochemical assessment and where a genetic cause of short stature is expected from the family history, DNA analysis for key candidate genes can confirm a genetic diagnosis. A hierarchy and priority of molecular tests can be defined following careful clinical and biochemical assessment. Testing for molecular defects in the GH–IGF-I axis is not commercially available at the present time. However, there are a number of academic laboratories that perform DNA sequencing studies of the relevant candidate genes. In vitro functional studies may also be necessary to quantitate the degree of protein dysfunction, particularly in cases with a milder phenotype. There are many components of the GH and IGF signaling cascades that remain poorly understood and are legitimate candidates for harboring significant mutations and/or deletions. Thus the absence of identifiable mutations in the candidate genes described above cannot rule out the possibility of a molecular abnormality of the GH–IGF axis.

Ideally family members should also be tested. It is now clear that members of the same family with the same mutations may have differing phenotypes Milward et al., 2004). Additionally, for many of the autosomal recessive disorders described above, the issue of heterozygous expression remains of great interest and is worthy of further study (Fofanova-Gambetti et al., 2010; van Duyvenvoorde et al., 2010).

Conclusion

From the fundamental importance of the GH–IGF axis in human linear growth, it follows that defects at many points in this axis will result in growth impairment leading to short stature. The key defects leading to GHI have been described and the range of genetic, clinical, and biochemical abnormalities, both within each genetic disorder and within the spectrum of GHI disorders as a whole has been emphasized. GHI can no longer be considered to be a single clinical entity, as it was envisaged nearly 50 years ago. As new genetic defects leading to an expansion of the field of GHI are described, each new mutation will itself contribute to the genetic and phenotypic continuum. Although the precise etiology in many children with short stature remains uncertain, the investigation of patients with abnormal growth should be encouraged in order to improve diagnosis and contribute to science.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Martin O. Savage – Ipsen consultancy fees > $10k, Advisory Council < $10k, honoraria < $10k, Pfizer Inc honoraria < $10k. Vivian Hwa – Nothing to disclose. Alessia David – Nothing to disclose. Ron G. Rosenfeld – Ipsen consulting fees, Advisory Council > $10k, honoraria < $10k, Lilly consulting fees, Advisory Council < $10k. Louise A. Metherell – Nothing to disclose.

References

- Aalbers A. M., Chin D., Pratt K. L., Little B. M., Frank S. J., Hwa V., Rosenfeld R. G. (2009). Extreme elevation of serum growth hormone-binding protein concentrations resulting from a novel heterozygous splice site mutation of the growth hormone receptor gene. Horm. Res. 71, 276–284 10.1159/000208801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuzzahab M. J., Schneider A., Goddard A., Grigorescu F., Lautier C., Keller E., Kiess W., Klammt J., Kratzsch J., Osgood D., Pfäffle R., Raile K., Seidel B., Smith R. J., Chernausek S. D. (2003). IGF-I receptor mutations resulting in intrauterine and postnatal growth retardation. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 2211–2222 10.1056/NEJMoa010107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams T. E., Epa V. C., Garrett T. P., Ward C. W. (2000). Structure and function of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57, 1050–1093 10.1007/PL00000744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akker S. A., Misra S., Aslam S., Morgan E. L., Smith P. J., Khoo B., Chew S. L. (2007). Pre-spliceosomal binding of U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (RNP) and heterogenous nuclear RNP E1 is associated with suppression of a growth hormone receptor pseudoexon. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 2529–2540 10.1210/me.2007-0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alatzoglou K. S., Dattani M. T. (2010). Genetic causes and treatment of isolated growth hormone deficiency-an update. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 6, 562–576 10.1038/nrendo.2010.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amselem S., Duquesnoy P., Attree O., Novelli G., Bousnina S., Postel-Vinay M. C., Goossens M. (1989). Laron dwarfism and mutations of the growth hormone-receptor gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 321, 989–995 10.1056/NEJM198910123211501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayling R. M., Ross R., Towner P., Von Laue S., Finidori J., Moutoussamy S., Buchanan C. R., Clayton P. E., Norman M. R. (1997). A dominant-negative mutation of the growth hormone receptor causes familial short stature. Nat. Genet. 16, 13–14 10.1038/ng0597-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay J. L., Kerr L. M., Arthur L., Rowland J. C., Nelson C. N., Ishikawa M., d’Aniello E. M., White M., Noakes P. G., Waters M. J. (2010). In vivo targeting of the growth hormone receptor (GHR) Box1 sequence demonstrates that the GHR does not signal exclusively through JAK2. Mol. Endocrinol. 24, 204–217 10.1210/me.2009-0233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann G. (2002). Genetic characterization of growth hormone deficiency and resistance: implications for treatment with recombinant growth hormone. Am. J. Pharmacogenomics 2, 93–111 10.2165/00129785-200202020-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter R. C. (1994). Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in the human circulation: a review. Horm. Res. 42, 140–144 10.1159/000184186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi A., Marino R., Ribas A., Rossi J., Ciaccio M., Oleastro M., Ornani A., Paz R., Rivarola M., Zelazko M., Belgorosky A. (2006). Characterization of immunodeficiency in a patient with growth hormone insensitivity secondary to a novel STAT5b gene mutation. Pediatrics 118, e1584–e1592 10.1542/peds.2005-2882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson A., Salemi S., Deladoëy J., Vuissoz J-M., Eblé A., Bidlingmaier M., Bürgi S., Honegger U., Flück C., Mullis P. E. (2005). Short stature caused by a biologically inactive mutant growth hormone (GH-C53S). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 2493–2499 10.1210/jc.2004-1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum W. F., Cotterill A. M., Postel-Vinay M.-C., Ranke M. B., Savage M. O., Wilton P. (1994). Improvement of diagnostic criteria in growth hormone insensitivity syndrome: solutions and pitfalls. Pharmacia Study Group on insulin-like growth factor I treatment in growth hormone insensitivity syndromes. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 399, 117–124 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonapace G., Concolino D., Formicola S., Strisciuglio P. (2003). A novel mutation in a patient with insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) deficiency. J. Med. Genet. 40, 913–917 10.1136/jmg.40.12.913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckway C. K., Guevara-Aguirre J., Pratt K. L., Burren C. P., Rosenfeld R. G. (2001). The IGF-I generation test revisited: a marker of GH sensitivity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 5176–5183 10.1210/jc.86.10.4943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burren C. P., Wanek D., Mohan S., Cohen P., Gievara-Aguirre J., Rosenfeld R. G. (1999). Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in Ecuadorean children with, growth hormone insensitivity. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 88, 185–191 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb14387.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Hübner C., Woods K. A., Miraki-Moud F., Hindmarsh P. C., Clark A. J., Hansson Y., Johnston A., Baxter R. C., Savage M. O. (1999). Effects of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) therapy on the growth hormone-IGF system of a patient with partial IGF-I gene deletion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84, 1611–1616 10.1210/jc.84.5.1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Vinkemeier U., Zhao Y., Jeruzalmi D., Darnell J. E., Jr., Kuriyan J. (1998). Crystal structure of a tyrosine phosphorylated STAT-1 dimer bound to DNA. Cell 93, 827–839 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81443-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia D. J., Subbian E., Buck T. M., Hwa V., Rosenfeld R. G., Skach W. R., Shinde U., Rotwein P. (2006). Aberrant folding of a mutant STAT5b causes growth hormone insensitivity and proteasomal dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6552–6558 10.1074/jbc.M510903200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia D. J., Varco-Merth B., Rotwein P. (2010). Dispersed chromosomal Stat5b-binding elements mediate growth hormone-activated insulin-like growth factor-I gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17636–17646 10.1074/jbc.M110.117697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianfarani S., Liguori A., Boemi S., Maghnie M., Lughetti L., Wasniewska M., Street M. E., Zucchini S., Aimareti G. L., Germani D. (2005). Inaccuracy of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein (IGFBP-3 assessment in the diagnosis of growth hormone (GH) deficiency from childhood to young adulthood: association to low GH dependency of IGF-II and presence of circulating IGFBP-3 18-kilodalton fragment. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 6028–6034 10.1210/jc.2005-0721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogan J. D., Phillips J. A., III. (2006). GH1 gene deletions, and IGHD type 1A. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 3, 480–488 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. C., Nadeau K. C., Tu W., Hwa V., Dionis K., Bezrodnik L., Teper A., Gaillard M., Heinrich J., Krensky A. M., Rosenfeld R. G., Lewis D. B. (2006). Cutting edge: decreased accumulation and regulatory function of CD4+CD25high T cells in human STAT5b deficiency. J. Immunol. 177, 2770–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P., Rogol A. D., Deal C. L., Saenger P., Reiter E. O., Ross J. L., Chernausek S. D., Savage M. O., Wit J. M., on behalf of the 2007 ISS Consensus Workshop participants (2008). Consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of children with idiopathic short stature: a summary of the Growth Hormone Research Society, the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology Workshop. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 4210–4217 10.1210/jc.2008-0509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A., Camacho-Hübner C., Bhangoo A., Rose S. J., Miraki-Moud F., Akker S. A., Butler G. E., Ten S., Clayton P. E., Clark A. J. L., Savage M. O., Metherell L. A. (2007). An intronic growth hormone receptor mutation causing activation of a pseudoexon is associated with a broad spectrum of growth hormone insensitivity phenotypes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 655–659 10.1210/jc.2006-1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A., Rose S. J., Miraki-Moud F., Metherell L. A., Savage M. O., Clark A. J. L., Camacho-Hübner C. (2010). Acid-labile subunit deficiency and growth failure: description of two novel cases. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 73, 328–334 10.1159/000308164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derr M. A., Fang P., Sinha S. K., Ten S., Hwa V., Rosenfeld R. G. (2011). A novel Y332C missense mutation in the intracellular domain of the human growth hormone receptor (GHR) does not alter STAT5b signaling: redundancy of GHR intracellular tyrosines involved in STAT5b signaling. Horm. Res. Pediatr. 75, 187–199 10.1159/000320461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domené H. M., Bengolea S. V., Martínez A. S., Ropelato M. G., Pennisi P., Scaglia P., Heinrich J. J., Jasper H. G. (2004). Deficiency of the circulating insulin-like growth factor system associated with inactivation of the acid-labile subunit gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 570–577 10.1056/NEJMoa013100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domené H. M., Hwa V., Argente J., Wit J. M., Camacho-Hübner C., Jasper H. G., Pozo J., van Duyvenvoorde H. A., Yakar S., Fofanova-Gambetti O. V., Rosenfeld R. G., International ALS Collaborative Group (2009). Human acid-labile subunit deficiency: clinical, endocrine and metabolic consequences. Horm. Res. Pediatr. 72, 129–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domené H. M., Martínez A. S., Frystyk J., Bengolea S. V., Ropelato M. G., Scaglia P. A., Chen J. W., Heuck C., Wolthers O. D., Heinrich J. J., Jasper H. G. (2007). Normal growth spurt and final height despite low levels of all forms of circulating insulin-like growth factor-I in a patient with acid-labile subunit deficiency. Horm. Res. 67, 243–249 10.1159/000098479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshet R., Laron Z., Pertzelan A., Arnon R., Dintzman M. (1984). Defect of human growth hormone receptors in the liver of two patients with Laron-type dwarfism. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 20, 8–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang P., Riedl S., Amselem S., Pratt K. L., Little B. M., Haeusler G., Hwa V., Frisch H., Rosenfeld R. G. (2007). Primary growth hormone (GH) insensitivity and insulin-like growth factor deficiency caused by novel compound heterozygous mutations of the GH receptor gene: genetic and functional studies of simple and compound heterozygous states. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 2223–2231 10.1210/jc.2006-2624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang P., Schwartz I. D., Johnson B. D., Derr M. A., Roberts C. T., Jr., Hwa V., Rosenfeld R. G. (2009). Familial short stature caused by haploinsufficiency of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor due to nonsense-mediated messenger ribonucleic acid decay. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 1740–1747 10.1210/jc.2008-1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fofanova-Gambetti O. V., Hwa V., Wit J. M., Domene H. M., Argente J., Bang P., Högler W., Kirsch S., Pihoker C., Chiu H. K., Cohen L., Jacobsen C., Jasper H. G., Haeusler G., Campos-Barros A., Gallego-Gómez E., Gracia-Bouthelier R., van Duyvenvoorde H. A., Pozo J., Rosenfeld R. G. (2010). Impact of heterozygosity for acid-labile subunit (IGFALS) gene mutations on stature: results from the international acid-labile subunit consortium. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 4184–4191 10.1210/jc.2010-0489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden A. L. (2003). The insulin-like growth factors and feto-placental growth. Placenta 24, 803–812 10.1016/S0143-4004(03)00080-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godowski P. J., Leung D. W., Meacham L. R., Galgani J. P., Hellmiss R., Keret R., Rotwein P. S., Parks J. S., Laron Z., Wood W. I. (1989). Characterization of the human growth hormone receptor gene and demonstration of a partial gene deletion in two patients with Laron-type dwarfism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 8083–8087 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H., Morikawa M., Nixon T. (1985). A dual effector theory of growth-hormone action. Differentiation 29, 195–198 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1985.tb00316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growth Hormone Research Society (2000). Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of growth hormone (GH) deficiency in childhood and adolescence: summary statement of the GH Research Society. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85, 3990–3993 10.1210/jc.85.11.3990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han V. K., Lund P. K., Lee D. C., D’Ercole A. J. (1988). Expression of somatomedin/insulin-like growth factor messenger ribonucleic acids in the human fetus: identification, characterization, and tissue distribution. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 66, 422–429 10.1210/jcem-66-2-422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath K. E., Argente J., Barrios V., Pozo J., Díaz-González F., Martos-Moreno G. A., Caimari M., Gracia R., Campos-Barros A. (2008). Primary acid-labile subunit deficiency due to recessive IGFALS mutations results in postnatal growth deficit associated with low circulating insulin growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3 levels, and hyperinsulinemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 1616–1624 10.1210/jc.2007-2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa V., Camacho-Hübner C., Little B. M., David A., Metherell L. A., El-Khatib N., Savage M. O., Rosenfeld R. G. (2007). Growth hormone insensitivity and severe short stature in siblings: a novel mutation at the exon 13-intron 13 junction of the STAT5b gene. Horm. Res. 68, 218–224 10.1159/000101334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa V., Little B., Adiyaman P., Kofoed E. M., Pratt K. L., Ocal G., Berberoglu M., Rosenfeld R. G. (2005). Severe growth hormone insensitivity resulting from total absence of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 4260–4266 10.1210/jc.2005-0515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa V., Little B., Kofoed E. M., Rosenfeld R. G. (2004). Transcriptional regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I by interferon-gamma requires STAT-5b. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2728–2736 10.1074/jbc.M310495200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida K., Takahashi Y., Kaji H., Nose O., Okimura Y., Abe H., Chihara K. (1998). Growth hormone (GH) insensitivity syndrome with high serum GH-binding protein levels caused by a heterozygous splice site mutation of the GH receptor gene producing a lack of intracellular domain. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 83, 531–537 10.1210/jc.83.2.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki K., Tiulpakov A., Rubtsov P., Sverdlova P., Peterkova V., Yakar S., Terekhov S., LeRoith D. (2007). A familial insulin-like growth factor-I receptor mutant leads to short stature: clinical and biochemical characterization. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 1542–1548 10.1210/jc.2006-2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaksson O. G., Jansson J. O., Gause I. A. (1982). Growth hormone stimulates longitudinal bone growth directly. Science 216, 1237–1239 10.1126/science.7079756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaksson O. G., Lindahl A., Nilsson A., Isgaard J. (1987). Mechanism of the stimulatory effect of growth hormone on longitudinal bone growth. Endocr. Rev. 8, 426–438 10.1210/edrv-8-4-426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H., Lanning N. J., Carter-Su C. (2008). JAK2, but not Src family kinases, is required for STAT, ERK, and Akt signaling in response to growth hormone in preadipocytes and hepatoma cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 1825–1841 10.1210/me.2008-0015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorge A. A., Souza S. C., Arbhold I. J., Mendonca B. B. (2002). Poor reproducibility of the IGF-I and IGF binding protein-3 generation test in children with short stature and normal coding region of the GH receptor gene. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 466–468 10.1210/jc.87.2.466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul A., Bang P., Hertel N. T., Main K., Dalgaard P., Jørgensen K., Müller J., Hall K., Skakkebaek N. E. (1994). Serum insulin-like growth factor-I in 1030 healthy children, adolescents and adults: relation to age, sex, stage of puberty, testicular size and body mass index. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 78, 744–752 10.1210/jc.78.3.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul A., Dalgaard P., Blum W. F., Bang P., Hall K., Michaelsen K. F., Müller J., Skakkebaek N. E. (1995). Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)- binding protein- 3 (IGFBP-3) in healthy infants, children and adolescents: the relation to IGF-I, IGF-II, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2, age, sex, body mass index and pubertal maturation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 80, 2534–2542 10.1210/jc.80.10.3059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S. A., Cohen P. (2007). The somatomedin hypothesis 2007: 50 years later. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 4529–4535 10.1210/jc.2006-1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima Y., Kanzaki S., Yang F., Kinoshita T., Hanaki K., Nagaishi J., Ohtsuka Y., Hisatome I., Ninomoya H., Nanba E., Fukushima T., Takahashi S. I. (2005). Mutation at cleavage site of insulin-like growth factor receptor in a short-stature child born with intrauterine growth retardation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 4679–4687 10.1210/jc.2004-1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoed E. M., Hwa V., Little B., Woods K. A., Buckway C. K., Tsubaki J., Pratt K. L., Bezrodnik L., Jasper H., Tepper A., Heinrich J., Rosenfeld R. G. (2003). Growth-hormone insensitivity associated with a STAT5b mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1139–1147 10.1056/NEJMoa022926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowarski A. A., Schneider J., Ben-Galim E., Weldon V. V., Daughaday W. H. (1978). Growth failure with normal serum RIA-GH, and low somatomedin activity: somatomedin restoration, and growth acceleration after exogenous GH. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 47, 461–464 10.1210/jcem-47-2-461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laron Z. (2004). Laron syndrome (primary growth hormone resistance or insensitivity): the personal experience 1958-2003. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89, 1031–1044 10.1210/jc.2003-031033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laron Z., Klinger B., Erster B., Anin S. (1988). Effect of acute administration of insulin-like growth factor I in patients with Laron-type dwarfism. Lancet 2, 1170–1172 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90236-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laron Z., Pertzelan A., Mannheimer S. (1966). Genetic pituitary dwarfism with high serum concentration of growth hormone – a new inborn error of metabolism? Isr. J. Med. Sci. 2, 152–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roith D., Bondy C., Yakar S., Liu J. L., Butler A. (2001). The somatomedin hypothesis: 2001. Endocr. Rev. 22, 53–74 10.1210/er.22.1.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong S. R., Baxter R. C., Camerato T., Dai J., Wood W. I. (1992). Structure and functional expression of the acid-labile subunit of the insulin-like growth factor-binding protein complex. Mol. Endocrinol. 6, 870–876 10.1210/me.6.6.870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe W. L., Jr., Lasky S. R., LeRoith D., Roberts C. T., Jr. (1988). Distribution and regulation of rat insulin-like growth factor I messenger ribonucleic acids encoding alternative carboxyterminal E-peptides: evidence for differential processing and regulation in liver. Mol. Endocrinol. 2, 528–535 10.1210/mend-2-6-528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe W. L., Jr., Roberts C. T., Jr., Lasky S. R., LeRoith D. (1987). Differential expression of alternative 5′ untranslated regions in mRNAs encoding rat insulin-like growth factor I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 8946–8950 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupu F., Terwilliger J. D., Lee K., Segre G. V., Efstratiadis A. (2001). Roles of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 in mouse postnatal growth. Dev. Biol. 229, 141–162 10.1006/dbio.2000.9975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maamra M., Milward A., Esfahami H. Z., Abbott L. P., Metherell L. A., Savage M. O., Clark A. J. L., Ross R. J. M. (2006). A 36 residues insertion in the dimerization domain of the growth hormone receptor results in defective trafficking rather than impaired signalling. J. Endocrinol. 188, 251–261 10.1677/joe.1.06252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metherell L. A., Akker S. A., Munroe P. B., Rose S. J., Caulfield M., Savage M. O., Chew S. L., Clark A. J. L. (2001). Pseudoexon activation as a novel mechanism for disease resulting in atypical growth hormone insensitivity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 641–646 10.1086/323266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midyett L. K., Rogol A. D., Van Meter Q. L., Frane J., Bright G. M., MS301 Study Group (2010). Recombinant insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I treatment in short children with low IGF-I levels: first-year results from a randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 611–619 10.1210/jc.2009-0570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milward A., Metherell L., Maamra M., Barahona M. J., Wilkinson I. D. R., Camacho-Hübner C., Savage M. O., Bidlingmaier M., Clark A. J. L., Ross R. J. M., Webb S. M. (2004). Growth hormone insensitivity syndrome due to a growth hormone receptor truncated after Box 1 resulting in Isolated failure of STAT 5 signal transduction. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89, 1259–1266 10.1210/jc.2003-031418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netchine I., Azzi S., Houang M., Seurin D., Perin L., Ricot J.-M., Daubas C., Legay C., Mester J., Herich R., Godeau F., Le Bouc Y. (2009). Partial primary deficiency of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I activity associated with IGF-1 mutation demonstrates its critical role in growth and brain development. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 3913–3921 10.1210/jc.2009-0452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netchine I., Rossignol S., Dufourg M. N., Azzi S., Rousseau A., Perin L., Houang M., Steunou V., Esteva B., Thibaud N., Demay M. C., Danton F., Petriczko E., Bertrand A. M., Heinrichs C., Carel J. C., Loeuille G. A., Pinto G., Jacquemont M. L., Gicquel C., Cabrol S., Le Bouc Y. (2007). 11p15 imprinting center region 1 loss of methylation is a common and specific cause of typical Russell-Silver syndrome: clinical scoring system and epigenetic-phenotypic correlations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 3148–3154 10.1210/jc.2007-0354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson A., Isgaard J., Lindahl A., Dahlstrom A., Skottner A., Isaksson O. G. (1986). Regulation by growth hormone of number of chondrocytes containing IGF-I in rat growth plate. Science 233, 571–574 10.1126/science.3523759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson C., Mohan S., Sjögren K., Tivesten A., Isgaard J., Isaksson O., Jansson J. O., Svensson J. (2009). The role of liver-derived insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocr. Rev. 30, 494–535 10.1210/er.2009-0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi G. T., Cohen F. J., Tseng L. Y., Rechler M. M., Boisclair Y. R. (1997). Growth hormone stimulates transcription of the gene encoding the acid-labile subunit (ALS) of the circulating insulin-like growth factor-binding protein complex and ALS promoter activity in rat liver. Mol. Endocrinol. 11, 997–1007 10.1210/me.11.7.997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. A., Hjelle B. L., Seeburg P. H., Zachmann M. (1981). Molecular basis for familial isolated growth hormone deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 6372–6375 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor A. M., Phillips J. A., III, Cooper D. N. (1998). The molecular genetics of growth hormone deficiency. Hum. Genet. 103, 255–272 10.1007/s004390050815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese-Pires P. N., Tonelli C. A., Dora J. M., Silva P. C. A., Czepielewski M., Simoni G., Arnhold I. J., Jorge A. A. (2010). A novel STAT5B mutation causing GH insensitivity syndrome associated with hyperprolactinemia and immune dysfunction in two male siblings. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 163, 349–355 10.1530/EJE-10-0272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl S., Frisch H. (2006). Effects of growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor-I therapy in patients with gene defects in the GH axis. J. Paediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 19, 229–236 10.1515/JPEM.2006.19.3.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C. T., Jr., Lasky S. R., Lowe W. L., Jr., Seaman W. T., LeRoith D. (1987). Molecular cloning of rat insulin-like growth factor I complementary deoxyribonucleic acids: differential messenger ribonucleic acid processing and regulation by growth hormone in extrahepatic tissues. Mol. Endocrinol. 1, 243–248 10.1210/mend-1-3-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld R. G. (2005). “The IGF system: new developments relevant to pediatric practice,” in IGF-I and IGF Binding Proteins: Basic Research and Clinical Management, Vol. 9, eds Cianfarani S., Clemmons D. R., Savage M. O. (Basel: Karger; ), 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld R. G., Belgorosky A., Camacho-Hübner C., Savage M. O., Wit J. M., Hwa V. (2007). Defects in growth hormone receptor signaling. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 18, 134–141 10.1016/j.tem.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld R. G., Kemp S. F., Hintz R. L. (1981). Constancy of somatomedin response to growth hormone treatment of hypopituitary dwarfism, and lack of correlation with growth rate. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 53, 611–617 10.1210/jcem-53-3-611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld R. G., Rosenbloom A. L., Guevara-Aguirre J. (1994). Growth hormone (GH) insensitivity due to primary GH receptor deficiency. Endocr. Rev. 15, 369–390 10.1210/edrv-15-3-369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlinson S. W., Yoshizato H., Barclay J. L., Brooks A. J., Behncken S. N., Kerr L. M., Millard K., Palethorpe K., Nielsen K., Clyde-Smith J., Hancock J. F., Waters M. J. (2008). An agonist-induced conformational change in the growth hormone receptor determines the choice of signalling pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 740–747 10.1038/ncb1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon W. D., Jr., Daughaday W. H. (1957). A hormonally controlled serum factor which stimulates sulphate incorporation by cartilage in vitro. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 49, 825–836 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage M. O., Attie K. M., David A., Metherell L. A., Clark A. J., Camacho-Hübner C. (2006). Endocrine assessment, molecular characterization and treatment of growth hormone insensitivity disorders. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2, 395–407 10.1038/ncpendmet0195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage M. O., Burren C. P., Rosenfeld R. G. (2010). The continuum of growth hormone-IGF-I axis defects causing short stature: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Clin. Endocrinol. 72, 721–728 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03775.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selva K. A., Buckway C. K., Sexton G., Pratt K. L., Tjoeng E., Guevarra-Aguirre J., Rosenfeld R. G. (2003). Reproducibility in patterns of IGF generation tests with special reference to idiopathic short stature. Horm. Res. 60, 237–246 10.1159/000074038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren K., Liu J. L., Blad K., Skrtic S., Vidal O., Wallenius V., LeRoith D., Tornell J., Isaksson O. G., Jansson J. O., Ohlsson C. (1999). Liver-derived insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is the principal source of IGF-I in blood but is not required for postnatal body growth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 7088–7092 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Kaji H., Okimura Y., Goji K., Abe H., Chihara K. (1996). Short stature caused by a mutant growth hormone. N. Eng. J. Med. 334, 432–436 10.1056/NEJM199602153340704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Shirono H., Arisaka O., Takahashi K., Yagi T., Koga J., Kaji H., Okimura Y., Abe H., Tanaka T., Chihara K. (1997). Biologically inactive growth hormone caused by an amino acid substitution. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 1159–1165 10.1172/JCI119627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki I., Ooi G. T., Tremblay M. L., Hurst K. R., Bach L. A., Boisclair Y. R. (2000). Inactivation of the acid labile subunit gene in mice results in mild retardation of postnatal growth despite profound disruptions in the circulating insulin-like growth factor system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6868–6873 10.1073/pnas.120172697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duyvenvoorde H. A., van Setten P. A., Walenkamp M. J., van Doorn J., Koenig J., Gauguin L., Oostdijk W., Ruivenkamp C. A., Losekoot M., Wade J. D., De Meyts P., Karperien M., Noordam C., Wit J. M. (2010). Short stature associated with a novel heterozygous mutation in the insulin-like growth factor 1 gene. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, E363–E367 10.1210/jc.2010-0511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidarsdottir S., Walenkamp M. J. E., Pereira A. M., Karperien M., van Doorn J., van Duyvenvoorde H. A., White S., Breuning M. H., Roelfsema F., Kruithof M. F., van Dissel J., Janssen R., Wit J. M., Romijn J. A. (2006). Clinical and biochemical characteristics of a male patient with a novel homozygous STAT5b mutation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 3482–3485 10.1210/jc.2006-0368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walenkamp M. J., van der Kamp H. J., Pereira A. M., Kant S. G., van Duyvenvoorde H. A., Kruithof M. F., Breuning M. H., Romijn J. A., Karperien M., Wit J. M. (2006). A variable degree of intrauterine and postnatal growth retardation in a family with a missense mutation in the insulin-like growth factor I receptor. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 3062–3470 10.1210/jc.2005-1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walenkamp M. J. E., Karperien M., Pereira A. M., Hilhorst-Hofstee Y., van Doorn J., Chen J. W., Mohan S., Denley A., Forbes B. E., van Duyvenvoorde H., van Thiel S. W., Sluimers C. A., Bax J. J., de Laat J. A. P. M., Breuning M. B., Romijn J. A., Wit J. M. (2005). Homozygous and heterozygous expression of a novel insulin-like growth factor-I mutation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 2855–2864 10.1210/jc.2004-1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. L., Ginalska-Malinovska M., Romer T. E., Pucilowska J. B., Underwood L. E. (1991). Effects of the infusion of insulin-like growth factor I in a child with growth hormone insensitivity syndrome (Laron dwarfism). N. Engl. J. Med. 324, 1483–1488 10.1056/NEJM199105233242107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Jiang H. (2005). Identification of a distal STAT-binding DNA region that may mediate growth hormone regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10955–10963 10.1074/jbc.M405287200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods K. A., Camacho-Hübner C., Bergman R. N., Barter D., Clark A. J. L., Savage M. O. (2000). Effects of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) therapy on body composition and insulin resistance in IGF-I gene deletion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85 1407–1411 10.1210/jc.85.4.1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods K. A., Dastot F., Preece M. A., Clark A. J. L., Postel-Vinay M. C., Chatelain P. G., Ranke M. B., Rosenfeld R. G., Amselem S., Savage M. O. (1997). Phenotype: genotype relationships in growth hormone insensitivity syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82, 3529–3535 10.1210/jc.82.5.1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods K. A., Fraser N. C., Postel-Vinay M.-C., Duquesnoy P., Savage M. O., Clark A. J. L. (1996a). A homozygous splice site mutation affecting the intracellular domain of the growth hormone receptor resulting in Laron syndrome with elevated growth hormone binding protein. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 81, 1686–1690 10.1210/jc.81.5.1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods K. A., Camacho-Hübner C., Savage M. O., Clark A. J. L. (1996b). Intrauterine growth retardation and post-natal growth failure associated with deletion of the insulin-like growth factor-I gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 335, 1363–1367 10.1056/NEJM199610313351805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Sun H., Yakar S., LeRoith D. (2009). Elevated levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I in serum rescue the severe growth retardation of IGF-I null mice. Endocrinology 150, 4395–4403 10.1210/en.2009-0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakar S., Liu J. L., Stannard B., Butler A., Accili D., Sauer B., LeRoith D. (1999). Normal growth and development in the absence of hepatic insulin-like growth factor I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 7324–7329 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]