Abstract

RNA is an important drug target, but it is difficult to design or discover small molecules that modulate RNA function. In the present study, we report that rationally designed, modularly assembled small molecules that bind the RNA that causes myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) are potently bioactive in cell culture models. DM1 is caused when an expansion of r(CUG) repeats, or r(CUG)exp, is present in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the dystrophia myotonica protein kinase (DMPK) mRNA. r(CUG)exp folds into a hairpin with regularly repeating 5′CUG/3′GUC motifs and sequester muscleblind-like 1 protein (MBNL1). A variety of defects are associated with DM1 including: (i) formation of nuclear foci, (ii) decreased translation of DMPK mRNA due to its nuclear retention, and (iii) pre-mRNA splicing defects due to inactivation of MBNL1, which controls the alternative splicing of various pre-mRNAs. Previously, modularly assembled ligands targeting r(CUG)exp were designed using information in an RNA motif-ligand database. These studies showed that a bis-benzimidazole (H) binds the 5′CUG/3′GUC motif in r(CUG)exp. Therefore, we designed multivalent ligands to bind multiple copies of this motif simultaneously in r(CUG)exp. Herein, we report that the designed compounds improve DM1-associated defects including improvement of translational and pre-mRNA splicing defects and the disruption of nuclear foci. These studies may establish a foundation to exploit other RNA targets in genomic sequence.

Genome sequencing studies have deposited a wealth of information in public databases.(1, 2) The ultimate use of such information is the development of pharmaceutical agents to treat diseases. Various approaches have validated many targets for small molecule drugs in genomic sequence.(3, 4) Genomic sequencing and functional genomics efforts have provided information on RNA as potential drug target. For example, non-coding RNAs have been shown to regulate cellular pathways and their disregulation can cause disease.(5, 6) Despite the great potential of RNA as a drug target for small molecules, the vast majority of RNA targets remain unexploited. This is mainly due to the difficulty in identifying lead ligands that target RNA with high affinity and specificity using standard high throughput screening approaches. In an effort to expedite the identification and design of selective and potent small molecules targeting RNA, a database of RNA motif-ligand interactions identified using a variety of methods (7–10) is being constructed. The database can serve as a rich source of lead small molecules that bind RNA.

During the course of studies aimed at populating the RNA motif-ligand database, it was determined that small molecules bind RNA internal loops that are present in repeat-containing transcripts that cause neurological diseases. These include the 5′CUG/3′GUC (Figure 1) and 5′CCUG/3′GUCC motifs present in myotonic dystrophy types 1 and 2 (DM1 and DM2), respectively.(11–13) Since each transcript with expanded repeats contains regularly repeating copies of the targetable motifs, modular assembly strategies were developed to bind multiple motifs simultaneously (Figure 1). (11, 13, 14) In order to target the 5′CUG/3′GUC motifs found in r(CUG)exp, we synthesized a series of compounds with different valenices (numbers) of a bis-benzamidazole using a peptoid backbone (Figure 2). The compounds bind r(CUG)exp with nanomolar affinities and inhibit the r(CUG)exp-MBNL1 complex in vitro with nanomolar IC50’s (Table 1).(13)

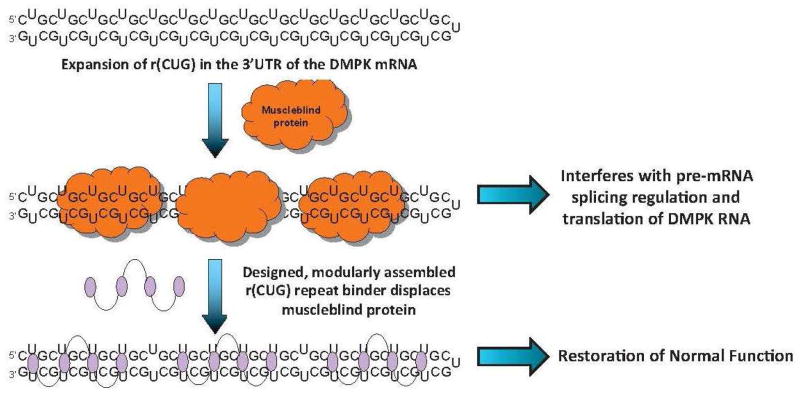

Figure 1.

A schematic for the molecular mechanism of DM1. An expanded r(CUG) repeat (r(CUG)exp) in the 3′UTR of the DMPK mRNA folds into a hairpin that binds to muscleblind-like 1 protein (MBNL1), a pre-mRNA splicing regulator. Sequestration of MBNL1 by r(CUG)exp causes disregulation of alternative splicing of genes controlled by MBNL1, decreased translation of the DMPK pre-mRNA, and formation of nuclear foci. Designed, modularly assembled ligands targeting the repeating transcript have potential to improve these defects.

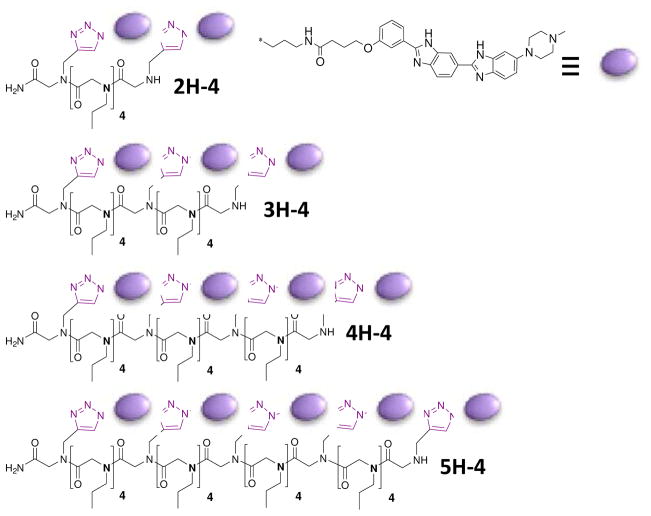

Figure 2.

The structures of the optimal modularly assembled, nH-4 (13) compounds that inhibit formation of the r(CUG)exp-MBNL1 interaction in vivo. The syntheses of the compounds were previously reported.(13) The synthesis of the 2H-4 compound was optimized, and the details can be found in the Supporting Information.

Table 1.

The binding affinities and potencies of rationally designed, modularly assembled small molecules targeting r(CUG)exp. The data were previously reported.(13)

| Compound | Kd (nM) | IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| MBNL1 | 250 | - |

| H | 150 | 110,000 |

| 2H-4 | 100 | 11,000 |

| 3H-4 | 65 | 410 |

| 4H-5 | 35 | 210 |

| 5H-4 | 13 | 77 |

In DM1, the expanded r(CUG) repeat, or r(CUG)exp, resides in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the dystrophia myotonica protein kinase (DMPK) mRNA. The expanded repeats cause disease by binding to muscleblind-like 1 protein (MBNL1). Sequestration of MBNL1 by the repeats causes defects in the alternative splicing of the cardiac troponin T (cTNT), the muscle-specific chloride ion channel, and the insulin receptor pre-mRNAs, among others.(15–17) In addition, a translational defect in DMPK is observed because the complex formed between r(CUG)exp with various proteins including MBNL1 leads to formation of nuclear foci and thus reduced nucleocytoplasmic transport of the DMPK mRNA.(18, 19)

Herein, we report that our designed compounds displaying multiple copies of a bis-benzimidazole (Figure 2) improve DM1-assoiated defects in cell culture models. In particular, they improve alternative splicing defects observed for the cTNT pre-mRNA, improve nucleocytoplasmic transport and hence translational levels, and disrupt nuclear foci to varying extents.

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

We previously reported that modularly assembled compounds containing multiple copies of a ligand that binds the 5′CUG/3′GUC bind r(CUG)exp and inhibit the r(CUG)exp-MBNL1 interaction in vitro (Table 1).(13) The compounds consist of a peptoid backbone that displays multiple copies of a bis-benzimidazole (H) separated by spacing modules (Figure 2).(13) The number of spacing modules has been optimized to span the two GC pairs that separate each of the 1×1 nucleotide UU internal loops in the DM1 RNA (Figure 1). The compounds have the general format nH-4 where n is the number of ligand modules, or valency, H indicates the RNA-binding ligand module (Hoechst-like, Figure 2), and 4 indicates the number of spacing modules between H’s (Figure 2). These optimized, designed compounds bind to r(CUG)exp with greater affinity and specificity than MBNL1.(13) They inhibit MBNL1 binding and displace MBNL1 from r(CUG)exp in vitro with nanomolar potencies (Table 1).(13)

nH-4 Compounds Improve Alternative Splicing Defects in a DM1 Cell Culture Model

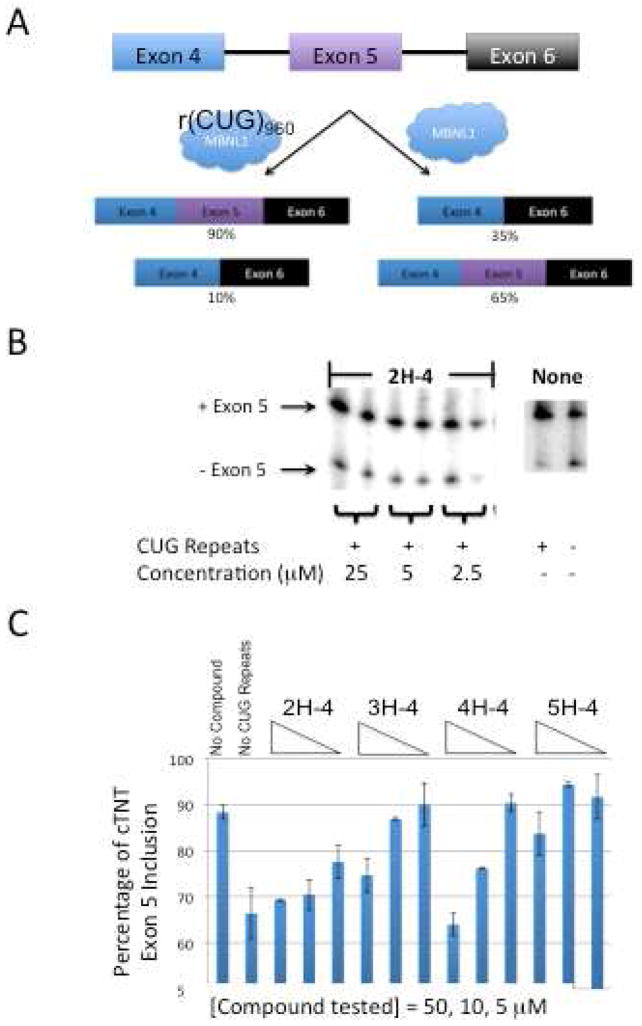

To assess the biological activity of the designer compounds, we determined whether they could improve pre-mRNA splicing defects that are associated with DM1 in a cell culture model. HeLa cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding a DM1 mini-gene that contains 960 interrupted CTG repeats and a cTNT mini-gene.(20, 21) cTNT pre-mRNA is mis-spliced in DM1 patients.(21–23) In normal cells, MBNL1 binds upstream of exon 5 in the cTNT pre-mRNA and represses its inclusion.(22, 24) After transfection, cells were treated with 2.5–25 μM of 2H-4 or 5–50 μM of 3H-4, 4H-4, or 5H-4. Their effects on splicing defects, indicative of the ability to displace MBNL1 from r(CUG)exp, was determined was determined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as previously described (20).

As shown in Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S-1, statistically significant improvement of splicing defects was observed for 2H-4, 3H-4, and 4H-4 while only minor improvement was observed for 5H-4, although it is not statistically significant. That is, splicing is improved to approximately wild type levels when cells are treated with 25 and 5 μM 2H-4 (with two-tailed p-values of 0.0014 and 0.0083, respectively), 50 μM 3H-4 (with a two-tailed p-value of 0.0412), and 50 and 10 μM 4H-4 (with two-tailed p-values of 0.0061 and 0.0035, respectively). Based on the corresponding in vitro potencies (Table 1), it was expected that the higher valency oligomers would be more effective at improving splicing defects. However, both 4H-4 and 5H-4 were not completely soluble in cell culture medium, with 5H-4 being less soluble than 4H-4. The H monomer was also tested in order to determine if it could restore splicing patterns in the DM1 cell culture model. No effect on splicing was observed when cells were treated with up to 100 μM H. Thus, modular assembly affords bioactive compounds even when the RNA-binding modules are not bioactive. It should be noted that no toxicity is observed in cell culture at concentrations of the ligands that are bioactive, as assessed by changes in cell morphology and cell death.

Figure 3.

nH-4 ligands improve DM1-associated pre-mRNA splicing defects. A, schematic of the pre-mRNA splicing pattern observed for the cTNT mini-gene (21) in the presence and absence of the DM1 mini-gene (21). B, representative gel autoradiogram to assess the effect of nH-4 compounds on the alternative splicing of the cTNT mini-gene. HeLa cells were transfected with either a DM1 mini-gene containing 960 interrupted CTG repeats and the cTNT mini-gene or a wild type (WT) mini-gene containing five CTG repeats and the cTNT mini-gene. After transfection, nH-4 compounds or water were added in growth medium to the cells. Total RNA was harvested 16–24 h later, and alternative splicing was assessed by RT-PCR using a radioactively labeled forward primer. The RT-PCR products were separated using a denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel. The size of the RT-PCR products was confirmed using a radioactively labeled 100 bp DNA ladder. C, plot of data obtained from RT-PCR analysis. Statistically significant improvement of splicing is observed when cells are treated with 2H-4, 3H-4, and 4H-4 while only modest improvement is observed for 5H-4. Each experiment was completed in at least duplicate and the errors are the standard deviations from replicate measurements. (Please see the text for two tailed p-values.)

Control experiments were also completed in which HeLa cells were co-transfected with a mini-gene containing only five CTG repeats (21) and the cTNT mini-gene.(21) The compounds do not affect cTNT splicing in the absence of r(CUG) repeats (Supplementary Figure S-2). Moreover, the nH-4 compounds have no effect on the alternative splicing of PLEKHH2 pre-mRNA, which is not controlled by MBNL1 (Supplementary Figure S-3). (The PLEKHH2 mini-gene is described in reference (20).)

Previously, the small molecule pentamidine was found to improve DM1-associated pre-mRNA splicing defects. The IC50 of pentamidine for improving cTNT splicing defects is ~50 μM,(20) which is 5-fold higher than the concentration of 2H-4 that improves splicing defects to approximately wild type levels (Figure 3). Thus, modular assembly provides designed compounds that are more bioactive than lower molecular weight compounds that are classically more “drug-like.”

nH-4 Compounds Improve DM1 Translation Defects in a Cell Culture Model

Next, compounds that improved splicing defects were tested for their ability to improve the DMPK translational defect observed in DM1-affected cells. A C2C12 cell line that stably expresses the firefly luciferase gene containing a (CTG)800 expansion in the 3′ UTR was employed for these studies. As in DM1-affected cells, the presence of r(CUG)800 causes nuclear retention of the luciferase mRNA and thus decreased expression of luciferase. If our compounds disrupt the r(CUG)800-MBNL1 interaction, then the luciferase mRNA will be more efficiently exported into the cytoplasm and translated, which is correlated to the luciferase activity in cell extracts (Figure 4).

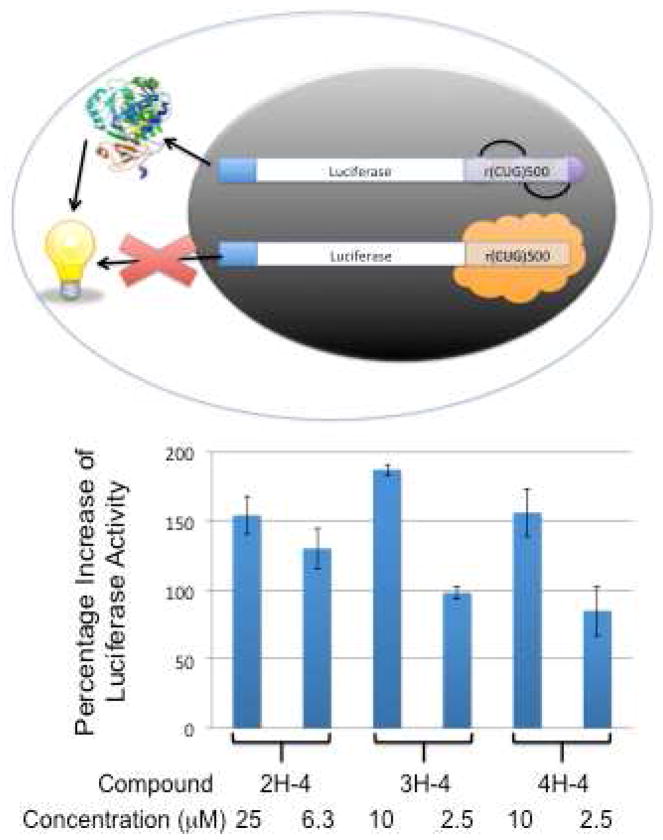

Figure 4.

Designed small molecules targeting r(CUG)exp improve DM1-associated translational defects in a cell culture model. Top, a schematic of the model cell-based system that was used to study the efficacy of the compounds. Briefly, a stably transfected C2C12 line was created that expresses firefly luciferase mRNA with r(CUG)800 in the 3′ UTR. In the absence of a small molecule that targets r(CUG)800, the transcript is mostly retained in the nucleus and thus it is not efficiently translated. If, however, a small molecule binds to the r(CUG)800 and displaces or inhibits MBNL1 binding, then the transcript is more efficiently exported from the nucleus and translated in the cytoplasm. Bottom, 2H-4, 3H-4, and 4H-4 improve translational defects associated with DM1. No effect on translation of firefly luciferase is observed when 50 μM of each compound is tested in a model system lacking r(CUG) repeats. Each experiment was completed in at least triplicate and the errors are the standard errors from replicate measurements. Please note that untreated cells have a “Percentage Increase of Luciferase Activity” value of 0.

Each of the three compounds, 2H-4, 3H-4, and 4H-4, stimulate production of luciferase when the transcript’s 3′UTR contains r(CUG)800 (Figure 4). There is at least a 150% increase in luciferase activity when cells are treated with 25 μM of 2H-4, or with 10 μM of 3H-4 or 4H-4. An μ100% increase is observed when cells are treated with 2.5 μM of 3H-4 or 4H-4. Increased luciferase activity is not observed when a stably transfected cell line expressing a luciferase construct that does not contain (CTG)800 is treated with 50 μM of 2H-4, 3H-4, or 4H-4. Thus, the effect of the compounds is specific to the presence of r(CUG)exp. That is, the compounds do not generally upregulate translation or specifically upregulate translation of the luciferase mRNA.

The bioactivity of a compound is affected by various properties including solubility, cellular permeability, cellular localization, stability, etc. In our previous studies, 3H-4, 4H-4, and 5H-4 are permeable to the C2C12 (mouse myoblast) cell line.(13) Valency increases cellular permeability at shorter incubation times (14 h) but has a lesser effect at longer incubation times (48 h).(13) The compounds mainly localize in the nucleus; the extent of nuclear localization increases with valency.(13)

Of the four compounds tested, 2H-4 most effectively improves pre-mRNA splicing defects while 3H-4 most effectively improves the DMPK mRNA translational defect. These differences may be traced to the synergistic ability of compounds to bind r(CUG)exp in vivo while simultaneously enabling the ligand-bound expanded repeat to be transported to the cytoplasm for translation. It could be that 2H-4 shows improved cellular permeability and nuclear localization, leading to disruption of the RNA-MBNL1 complex and restoration of MBNL1 activity. The extent of cytoplasmic transport may be greater with 3H-4 due to its ability to sequester a larger amount of the RNA’s surface area and prevent the binding of other proteins such as CUGBP1, MBNL2, and MBNL3.(25, 26)

nH-4 Compounds Disrupt Nuclear Foci

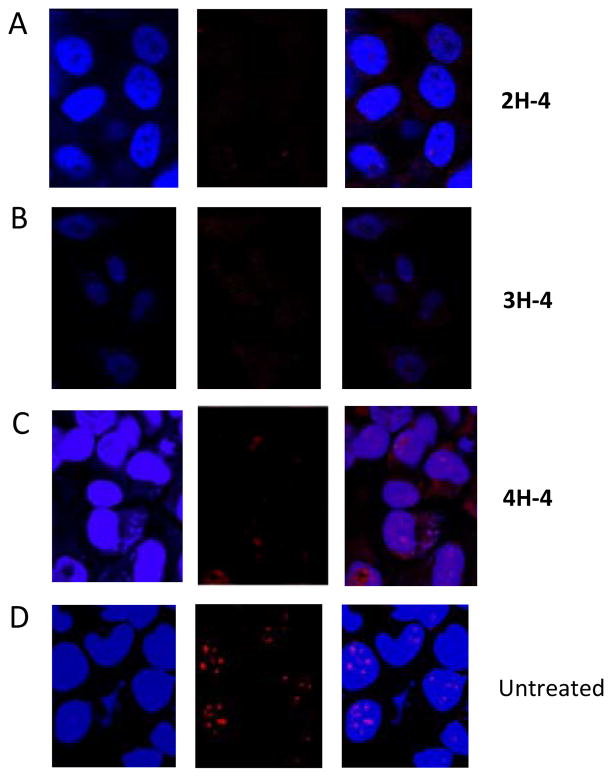

Another hallmark of DM1 is the presence of nuclear foci caused by aggregates of r(CUG)exp and various proteins including MBNL1.(26–31) Thus, it was determined if nH-4 compounds can disrupt formation of nuclear foci. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the DM1 mini-gene (21) and treated with an nH-4 modularly assembled compound. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was then used to visualize the r(CUG)exp. As shown in Figure 5, the number of foci is decreased and the foci are more diffuse when cells are treated with 25 μM of 2H-4 or 3H-4 and 50 μM of 4H-4.

Figure 5.

Disruption of nuclear foci by 2H-4, 3H-4, and 4H-4 as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). HeLa cells were transfected with a DM1 mini-gene containing 960 interrupted CTG repeats and then treated with the nH-4 compound.(21) After 16–24 h, the cells were fixed and the rCUG repeats were detected by FISH using DY547-2′OMe-(CAGCAGCAGCAGCAGCAGC). The cells were imaged by confocal microscopy. A, cells treated with 25 μM of 2H-4. B, cells treated with 25 μM of 3H-4. C, cells treated with 50 μM of 4H-4. D, untreated cells. For all panels: left, fluorescence in the DAPI channel indicating nuclei or nH-4 compound (nH-4 compounds have similar spectral properties as DAPI); middle, DY547 fluorescence indicating the presence of rCUG repeats; C, overlay of DY547 and DAPI/nH-4 images.

Summary

The biological efficacy of rationally designed compounds that bind the RNA that causes myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) was determined using cell culture models. The compounds display multiple copies of a ligand that was identified to bind the 5′CUG/3′GUC motif that periodically repeats in DM1-causing transcripts (Figure 1). The compounds improve alternative splicing defects, improve translational defects, and disrupt formation of nuclear foci to varying extents. It is likely that this approach can be applied to RNA transcripts containing other expanded repeats or other RNAs that contain multiple targetable motifs within relatively close proximity.

METHODS

Improvement of Splicing Defects in a Cell Culture Model Using RT-PCR

In order to determine if nH-4 compounds improve splicing defects in vivo, a previously reported method was employed.(20) Briefly, HeLa cells were grown as monolayers in 96-well plates in growth medium (1X DMEM, 10% FBS, and 1X GlutaMax (Invitrogen)). After the cells reached 90–95% confluency, they were transfected with 200 ng of total plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s standard protocol. Equal amounts of a plasmid expressing a DM1 mini-gene with 960 CTG repeats (21) and a mini-gene of interest (cTNT (21) or PLEKHH2 (24)) were used. Approximately 5 h post-transfection, the transfection cocktail was removed and replaced with growth medium containing the compound of interest. After 16–24 h, the cells were lysed in the well, and total RNA was harvested with a Qiagen RNAEasy kit. An on-column DNA digestion was completed per the manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

A sample of RNA was subjected to reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as previously described (24) except 5 units of AMV Reverse Transcriptase from Life Sciences were used. Approximately 300 ng were reverse transcribed, and 150 ng were subjected to PCR using a radioactively labeled forward primer. RT-PCR products were observed after 25–30 cycles of: 95 °C for 1 min; 55 °C for 1 min; 72 °C for 2 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The products were separated on a denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel and imaged using a Typhoon phosphorimager. The length of the RT-PCR products was confirmed by comparison to a 5′-32P end labeled 100 bp ladder. Differences in alternative splicing were evaluated by a t-test.

The RT-PCR primers for the cTNT mini-gene were: 5′GTTCACAACCATCTAAAGCAAGATG (forward) and 5′GTTGCATGGCTGGTGCAGG (reverse). The RT-PCR primers for the PLEKHH2 mini-gene were: 5′CGGGGTACCAAATGCTGCAGTTGACTCTCC (forward) and 5′CCGCTCGAGCCATTCATGAAGTGCACAGG (reverse).

Control experiments were also completed in which HeLa cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding a mini-gene with five CTG repeats in the 3′ UTR or with a mini-gene that encodes a pre-mRNA whose splicing is not controlled by MBNL1 (PLEKHH2).(24)

Generation of C1-S and C5-14 Cell Lines to Assess Improvement of Translational Defects

The pLLC14gpab plasmid contains a CMV/chicken beta-actin enhancer/promoter (a gift from Dr. J. Miyazaki) followed by a floxed EGFP-Puromycin gene fusion with a triple-stop SV40 transcription terminator followed by a firefly luciferase gene with the human DMPK (hDMPK) 3′ UTR. This design allows for conditional expression of the firefly transcript after Cre recombination by removal of the floxed EGFP-Puromycin-SV40 triple-stop. The hDMPK 3′ UTR contains a modified restriction site for the inclusion of CTG repeats. An uninterrupted CTG tract of ~500 repeats was generated by rolling circle amplification (RCA) of the repeat donor plasmid pDWD by Phi29 polymerase as previously described,(32) and then ligated into the hDMPK 3′ UTR of the pLLC14gpab plasmid. The ligation was used directly for transfection into C2C12 cells to prevent the inevitable CTG repeat truncation that occurs in the bacterial cloning process.(33)

C2C12 cells were co-transfected with ~100 ng pLLC14gpab (with or without 500 CTG repeats) and 5 μg of a pPhiC31o (34) expressing PhiC31 integrase, which yields efficient, site-specific, single copy integration of pLLC14gpab at its attB element.(35) Transfected cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS + 1% Penicillin/Streptomic + 3 μg/ml puromycin for ~10 days to select for clones with successful pLLC14gpab integration, and colonies were picked and expanded. Clones were then transfected with pHSVCreWT expressing Cre recombinase (a gift from Dr. W. Bowers) for the removal of the EGFP-Puromycin-SV40 triple stop, thus activating expression of the firefly luciferase transgene. A Cre-recombined no-CTG clone was identified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) by sorting for GFP negative cells. The Cre-recombined (CTG)500 clones were screened for CUG repeat RNA nuclear foci by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as previously described (36), and foci-positive cells were cloned by limiting dilution. The no-repeat, FACS sorted cells were designated C1-S and the CTG repeat-containing clone with bright, consistent CUG RNA foci was designated C5-14. Cre recombination for both cell lines was confirmed by PCR across the floxed region of the integrated pLLC14gpab construct, and both semi-quantitative RT-PCR and TaqMan real-time qRT-PCR analyses of the firefly luciferase transgene indicated strong and comparable expression in both C1-S and C5-14 cells. PCR analysis across the CTG repeat region of the C5-14 clone revealed an expansion of the CTG tract to ~800 CTG repeats, which was stable over the course of several passages.

Improvement of Translational Defects Using a Luciferase Assay

C2C12 cell lines expressing 800 (C5-14) or 0 (C1-S) CTG repeats in the 3′ UTR of luciferase were maintained as monolayers in growth medium (1X DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen), 1X Glutamax (Invitrogen), and 1X Penicillin/Streptomycin (MP Biomedicals, LLC)). The cells were plated in 96-well plates and allowed to grow for 24 h. The compound of interest was then added in 50 μL, and the cells were treated for 24 h.

The growth medium containing the compound of interest was removed and replaced with 100 μL of medium and 10 μL of WST-1 reagent (Roche). After 30 min, 60 μL aliquots were removed and placed into clear 96-well plates. The absorbance of the medium was measured at 450 nm and 690 nm. The corrected absorbance (Abs450 – Abs690) was used to normalize each well for cell count.

The remaining medium containing WST-1 reagent was removed, and 20 μL of 1X Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) was added to each well. The cells were placed at −20 °C for 15 min. After the buffer thawed, 100 μL of Luciferase Assay Substrate (Promega) were added to each well. Luminescence was immediately read on a SpectraMax M5 plate reader using an integration time of 5000 ms. The luminescence signal was normalized to the number of cells in the corresponding well using the results of the WST-1/cell proliferation assay.

Disruption of Nuclear Foci Using Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH).(20)

HeLa cells were grown as monolayers in Mat-Tek glass-bottomed, 96-well plates. After the cells reached 90–95% confluency, they were transfected with 200 ng of a plasmid encoding a DM1 mini-gene (21) using Lipfoectamine 2000 per the manufacturer’s standard protocol. The transfection cocktail was removed 5 h post-transfection, and the compound of interest was added in growth medium. Growth medium was added to untreated cells.

After 16–24 h, the cells were washed with 1X DPBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1X DPBS for 10 min at 37 °C. After washing with 1X DPBS, the cells were permeabilized with 1X DPBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed with 1X DPBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 three times and then with 30% formamide in 2X SSC Buffer (30 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl).

The cells were incubated in 1X FISH Buffer (30% formamide, 2X SSC Buffer, 66 μg/mL bulk yeast tRNA, 2 μg/mL BSA, 2 mM vanadyl complex (New England Bio Labs) and 1 ng/μL DY547-2′OMe-(CAGCAGCAGCAGCAGCAGC)) for 1.5 h at 37 °C. They were then washed with 30% formamide in 2X SSC for 30 min at 42 °C, 1X SSC for 30 min at 37 °C, and 1X DPBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were washed with 1X DPBS + 0.1% Triton X-100, and 100 μL of 1X DPBS were added to each well. Untreated cells were stained with 1 μg mL−1 DAPI for 5 min at room temperature, and then washed with 1X DPBS + 0.1% Triton X-100. The cells were imaged using an Olympus FluoView 1000 Confocal Microscope at 100X magnification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Matosevic for assistance with confocal microscopy. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (3R01GM079235-02S1 and 1R01GM079235-01A2 to MDD; AR049077 and U54NS48843 to CAT), by the Muscular Dystrophy Association (Grant# 158552 to MDD), and by The Scripps Research Institute. MDD is a Camille & Henry Dreyfus New Faculty Awardee, a Camille & Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar, and a Research Corporation Cottrell Scholar.

ABBREVIATIONS

- cTNT

cardiac troponin T pre-mRNA

- CUGBP1

CUG binding protein 1

- DM1

myotonic dystrophy type 1

- DM2

myotonic dystrophy type 2

- DMPK

dystrophia myotonica protein kinase

- MBNL1

muscleblind-like 1 protein

- MBNL2

muscleblind-like 2 protein

- MBNL3

muscleblind-like 3 protein

- PLEKHH2

Pleckstrin-2

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Full citations for references 1 & 2 and representative gel images. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides P, Ballew RM, Huson DH, Wortman JR, Zhang Q, Kodira CD, Zheng XH, Chen L, Skupski M, Subramanian G, Thomas PD, Zhang J, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson C, Broder S, Clark AG, Nadeau J, McKusick VA, Zinder N, Levine AJ, Roberts RJ, Simon M, Slayman C, Hunkapiller M, Bolanos R, Delcher A, Dew I, Fasulo D, Flanigan M, Florea L, Halpern A, Hannenhalli S, Kravitz S, Levy S, Mobarry C, Reinert K, Remington K, Abu-Threideh J, Beasley E, Biddick K, Bonazzi V, Brandon R, Cargill M, Chandramouliswaran I, Charlab R, Chaturvedi K, Deng Z, Di Francesco V, Dunn P, Eilbeck K, Evangelista C, Gabrielian AE, Gan W, Ge W, Gong F, Gu Z, Guan P, Heiman TJ, Higgins ME, Ji RR, Ke Z, Ketchum KA, Lai Z, Lei Y, Li Z, Li J, Liang Y, Lin X, Lu F, Merkulov GV, Milshina N, Moore HM, Naik AK, Narayan VA, Neelam B, Nusskern D, Rusch DB, Salzberg S, Shao W, Shue B, Sun J, Wang Z, Wang A, Wang X, Wang J, Wei M, Wides R, Xiao C, Yan C. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, Funke R, Gage D, Harris K, Heaford A, Howland J, Kann L, Lehoczky J, LeVine R, McEwan P, McKernan K, Meldrim J, Mesirov JP, Miranda C, Morris W, Naylor J, Raymond C, Rosetti M, Santos R, Sheridan A, Sougnez C, Stange-Thomann N, Stojanovic N, Subramanian A, Wyman D, Rogers J, Sulston J, Ainscough R, Beck S, Bentley D, Burton J, Clee C, Carter N, Coulson A, Deadman R, Deloukas P, Dunham A, Dunham I, Durbin R, French L, Grafham D, Gregory S, Hubbard T, Humphray S, Hunt A, Jones M, Lloyd C, McMurray A, Matthews L, Mercer S, Milne S, Mullikin JC, Mungall A, Plumb R, Ross M, Shownkeen R, Sims S, Waterston RH, Wilson RK, Hillier LW, McPherson JD, Marra MA, Mardis ER, Fulton LA, Chinwalla AT, Pepin KH, Gish WR, Chissoe SL, Wendl MC, Delehaunty KD, Miner TL, Delehaunty A, Kramer JB, Cook LL, Fulton RS, Johnson DL, Minx PJ, Clifton SW, Hawkins T, Branscomb E, Predki P, Richardson P, Wenning S, Slezak T, Doggett N, Cheng JF, Olsen A, Lucas S, Elkin C, Uberbacher E, Frazier M. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iorns E, Lord CJ, Turner N, Ashworth A. Utilizing RNA interference to enhance cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:556–568. doi: 10.1038/nrd2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Backer MD, Nelissen B, Logghe M, Viaene J, Loonen I, Vandoninck S, de Hoogt R, Dewaele S, Simons FA, Verhasselt P, Vanhoof G, Contreras R, Luyten WH. An antisense-based functional genomics approach for identification of genes critical for growth of Candida albicans. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:235–241. doi: 10.1038/85677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNAs and chromosomal abnormalities in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:6202–6210. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St Laurent G, 3rd, Faghihi MA, Wahlestedt C. Non-coding RNA transcripts: sensors of neuronal stress, modulators of synaptic plasticity, and agents of change in the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2009;466:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Childs-Disney JL, Wu M, Pushechnikov A, Aminova O, Disney MD. A small molecule microarray platform to select RNA internal loop-ligand interactions. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:745–754. doi: 10.1021/cb700174r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velagapudi SP, Seedhouse SJ, Disney MD. Structure-activity relationships through sequencing (StARTS) defines optimal and suboptimal RNA motif targets for small molecules. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:3816–3818. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velagapudi SP, Seedhouse SJ, French J, Disney MD. Defining the RNA internal loops preferred by benzimidazole derivatives via 2D combinatorial screening and computational analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10111–10118. doi: 10.1021/ja200212b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disney MD, Labuda LP, Paul DJ, Poplawski SG, Pushechnikov A, Tran T, Velagapudi SP, Wu M, Childs-Disney JL. Two-dimensional combinatorial screening identifies specific aminoglycoside-RNA internal loop partners. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11185–11194. doi: 10.1021/ja803234t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee MM, Childs-Disney JL, Pushechnikov A, French JM, Sobczak K, Thornton CA, Disney MD. Controlling the specificity of modularly assembled small molecules for RNA via ligand module spacing: targeting the RNAs that cause myotonic muscular dystrophy. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17464–17472. doi: 10.1021/ja906877y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Disney MD, Lee MM, Pushechnikov A, Childs-Disney JL. The role of flexibility in the rational design of modularly assembled ligands targeting the RNAs that cause the myotonic dystrophies. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:375–382. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pushechnikov A, Lee MM, Childs-Disney JL, Sobczak K, French JM, Thornton CA, Disney MD. Rational design of ligands targeting triplet repeating transcripts that cause RNA dominant disease: application to myotonic muscular dystrophy type 1 and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9767–9779. doi: 10.1021/ja9020149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MM, Pushechnikov A, Disney MD. Rational and modular design of potent ligands targeting the RNA that causes myotonic dystrophy 2. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:345–355. doi: 10.1021/cb900025w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Day JW, Ranum LP. RNA pathogenesis of the myotonic dystrophies. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanadia RN, Johnstone KA, Mankodi A, Lungu C, Thornton CA, Esson D, Timmers AM, Hauswirth WW, Swanson MS. A muscleblind knockout model for myotonic dystrophy. Science. 2003;302:1978–1980. doi: 10.1126/science.1088583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanadia RN, Shin J, Yuan Y, Beattie SG, Wheeler TM, Thornton CA, Swanson MS. Reversal of RNA missplicing and myotonia after muscleblind overexpression in a mouse poly(CUG) model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mastroyiannopoulos NP, Feldman ML, Uney JB, Mahadevan MS, Phylactou LA. Woodchuck post-transcriptional element induces nuclear export of myotonic dystrophy 3′ untranslated region transcripts. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarkar PS, Han J, Reddy S. In situ hybridization analysis of DMPK mRNA in adult mouse tissues. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warf MB, Nakamori M, Matthys CM, Thornton CA, Berglund JA. Pentamidine reverses the splicing defects associated with myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18551–18556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philips AV, Timchenko LT, Cooper TA. Disruption of splicing regulated by a CUG-binding protein in myotonic dystrophy. Science. 1998;280:737–741. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho TH, Charlet BN, Poulos MG, Singh G, Swanson MS, Cooper TA. Muscleblind proteins regulate alternative splicing. EMBO J. 2004;23:3103–3112. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nezu Y, Kino Y, Sasagawa N, Nishino I, Ishiura S. Expression of MBNL and CELF mRNA transcripts in muscles with myotonic dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warf MB, Berglund JA. MBNL binds similar RNA structures in the CUG repeats of myotonic dystrophy and its pre-mRNA substrate cardiac troponin T. RNA. 2007;13:2238–2251. doi: 10.1261/rna.610607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Timchenko NA, Cai ZJ, Welm AL, Reddy S, Ashizawa T, Timchenko LT. RNA CUG repeats sequester CUGBP1 and alter protein levels and activity of CUGBP1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7820–7826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fardaei M, Rogers MT, Thorpe HM, Larkin K, Hamshere MG, Harper PS, Brook JD. Three proteins, MBNL, MBLL and MBXL, co-localize in vivo with nuclear foci of expanded-repeat transcripts in DM1 and DM2 cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:805–814. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.7.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardani R, Mancinelli E, Rotondo G, Sansone V, Meola G. Muscleblind-like protein 1 nuclear sequestration is a molecular pathology marker of DM1 and DM2. Eur J Histochem. 2006;50:177–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fardaei M, Larkin K, Brook JD, Hamshere MG. In vivo co-localisation of MBNL protein with DMPK expanded-repeat transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2766–2771. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho TH, Savkur RS, Poulos MG, Mancini MA, Swanson MS, Cooper TA. Colocalization of muscleblind with RNA foci is separable from mis-regulation of alternative splicing in myotonic dystrophy. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2923–2933. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mankodi A, Urbinati CR, Yuan QP, Moxley RT, Sansone V, Krym M, Henderson D, Schalling M, Swanson MS, Thornton CA. Muscleblind localizes to nuclear foci of aberrant RNA in myotonic dystrophy types 1 and 2. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2165–2170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taneja KL, McCurrach M, Schalling M, Housman D, Singer RH. Foci of trinucleotide repeat transcripts in nuclei of myotonic dystrophy cells and tissues. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:995–1002. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osborne RJ, Thornton CA. Cell-free cloning of highly expanded CTG repeats by amplification of dimerized expanded repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang S, Jaworski A, Ohshima K, Wells RD. Expansion and deletion of CTG repeats from human disease genes are determined by the direction of replication in E. coli. Nat Genet. 1995;10:213–218. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raymond CS, Soriano P. High-efficiency FLP and PhiC31 site-specific recombination in mammalian cells. PLoS One. 2007;2:e162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thyagarajan B, Olivares EC, Hollis RP, Ginsburg DS, Calos MP. Site-specific genomic integration in mammalian cells mediated by phage phiC31 integrase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3926–3934. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.12.3926-3934.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamori M, Pearson CE, Thornton CA. Bidirectional transcription stimulates expansion and contraction of expanded (CTG)*(CAG) repeats. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:580–588. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.