Abstract

Heavy metal toxicity is a worldwide problem which is associated with the metal’s high affinity for thiolate rich proteins. Despite the tremendous toxicity concern, the mode of binding of As(III) and Pb(II) to proteins is poorly understood. To clarify the requirements for toxic metal binding to metalloregulatory sensor proteins such as As(III) in ArsR/ArsD and Pb(II) in PbrR or replacing Zn(II) in δ-aminolevulinc acid dehydratase (ALAD), we have employed computational and experimental methods examining these heavy metals binding to designed peptide models. The computational results show that the mode of coordination of As(III) and Pb(II) is greatly influenced by the steric bulk within the second coordination environment of the metal. The proposed basis of this selectivity is the large size of the ion and, most important, the influence of the stereochemically active lone pair in hemi-directed complexes of the metal ion as being crucial. The experimental data show that switching a bulky leucine layer above the metal binding site by a smaller alanine residue enhances the Pb(II) binding affinity by a factor of five supporting experimentally this lone pair steric hindrance hypothesis. These complementary approaches demonstrate the potential importance of a stereochemically active lone pair as a metal recognition mode in proteins and, specifically, how the second coordination sphere environment affects the affinity and selectivity of protein targets by certain toxic ions.

Keywords: Arsenic, heavy metal toxicity, lead, lone pair, selective binding

1. Introduction

Heavy metal ion (e.g. As(III), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Hg(II)) poisoning is occurring worldwide, with about 5% of the children in the United States estimated to be affected by lead poisoning.[1] Millions of people in South Asian countries are affected by arsenic poisoning through drinking ground water (>10 μg/L(10 ppb)).[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that 1 of 10 deaths in Bangladesh could be from arsenic triggered cancers.[2a] Heavy metal ion toxicity may arise from the production of highly reactive oxygen species (ROS),[3] reaction with sulfhydryl group of cysteines[4] at the actives site of many enzymes[5] and subsequent inhibition of enzymatic activity,[5b, c, 6] inhibition of DNA repair enzymes,[7] apoptosis,[8] or perturbation of DNA methylation.[9] Due to their ubiquities in the environment, most organisms, from bacteria to humans, have evolved several heavy metals detoxification pathways. For example, the arsenic resistance (ars) operon of the Escherichia coli conjugal plasmid R773 encodes 5 structural genes, arsRDABC, for arsenic detoxification.[10] Arsenic is bioavailable in two oxidation states: AsO43− (arsenate, As(V)) and AsO2− (arsenite, As(III)). Arsenate is transported to cells via the phosphate transport system, probably due to the similar structure with phosphate, whereas arsenite is acquired through aquaglyceroporins (GlpF in E.coli, Aqp7 & Aqp9 in mammals).[11] As(V) is reduced to the more toxic As(III) by arsenic reductase (ArsC) prior to extrusion or sequestration. The extrusion of reduced As(III) can either occur by efflux via an arsenite carrier protein or sequestration as thiol conjugates within the cell organelles.[11–12] ArsD is an arsenic metallochaperone that delivers As(III) to ArsA. ArsA (an ATPase) forms a complex with ArsB yielding an ArsAB extrusion pump that catalyzes the ATP-driven As(III) efflux.[13] In eukaryotic cells, a transmembrane protein, MRP1, serves this function.[14]

Similarly, to survive the toxic effects of Pb(II), the bacterial species Ralstonia metallidurans CH34 utilizes a MerR family protein, PbrR. The lead resistance operon (pbr) of R. metallidurans encodes structural resistance genes: pbrT (Pb(II) uptake), pbrA (ATPase dependent efflux), pbrB, pbrC, and pbrD (Pb(II) sequestration).[15] Recent spectroscopic studies by He and coworkers[16] showed the specificity and selectivity of Pb(II) binding with the PbrR2 protein (also called pbrR691) from Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 which was over-expressed in E. coli. This protein binds Pb(II) almost 103-fold more selectively than other metal ions such as Hg(II), Cd(II), Zn(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(I), Ag(I). The Hg(II)-binding MerR protein utilizes three conserved cysteine residues for the selective binding of Hg(II) in a trigonal planar geometry.[17] A sequence alignment of MerR and PbrR691 shows that these three cysteine residues are highly conserved in PbrR691 for Pb(II) binding.[18] It is well known that soft metal ions such as As(III), Pb(II), Hg(II), and Cd(II) have high affinity for sulfur containing molecules like cysteine,[19] glutathione, and metallothionein.[20] It is not surprising that all heavy metal ions have high affinity with cysteine, but how these proteins selectively bind one ion from another is not fully understood. There is still a debate as to whether protein folding imposes unusual coordination geometries on the metals which enable the metalloregulatory proteins to differentiate ions or whether metal binding geometry preference controls the protein folding. It has been speculated that the ligand pre-organization is the deciding factor for the metal recognition.[18]

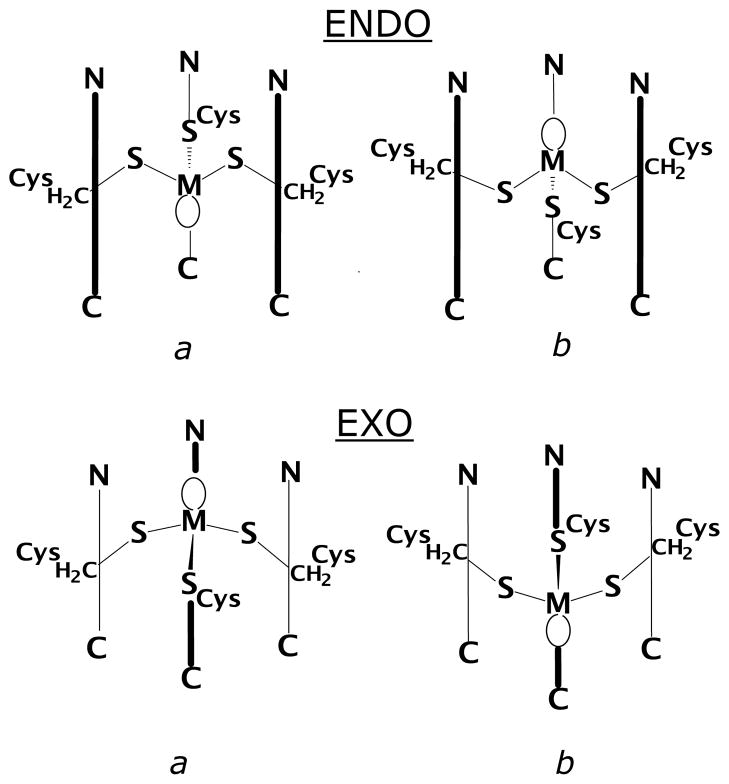

Recent EXAFS spectroscopic studies for arsenic[21] and lead[22] bound to regulatory proteins, ArsC and PbrR691 respectively, reveal that As(III) and Pb(II) are coordinated in hemidirected trigonal-pyramidal geometries. Depending on its coordination number, Pb(II) can have a hemidirected (ligands directed only over part of the surface) or a holodirected (ligands directed throughout the surface) geometry.[23] Pb(II) compounds are hemidirected in low coordination numbers (2–4) and holodirected in high coordination number (9–10).[23] Since both As(III) and Pb(II) have stereochemically active lone pairs, they can adopt unique coordination geometries compared with other metal ions.[24] The preference of trigonal-pyramidal thiolate structures by As(III) with small molecules[24e, 25] and in proteins[26] is further proven by a recent crystal structure of the designed three-stranded coiled coil As(CSL9C)3 by Touw et al.[26–27] Crystal structures of ArsD and ArsR have not yet been reported to explain the exact mode of As coordination, however, an exo-conformation (shown in scheme 1)1 of AsS3 was speculated based on the crystal structure of synthetic small molecules with aromatic rings or chelated alkyl dithiolates.[25] In contrast, Johnson and coworkers (using small molecules)[28] and Pecoraro and coworkers (using designed 3-strand coiled coil peptides)[27] discovered that the orientation of the lone pair could influence the As(III) to adopt an endo conformation. The As(CSL9C)3 [PDB code 2JGO] was the first example that directly mimicked the coordination environment of As(III) in ArsR and ArsD. Therefore, we believe that arsenic may be bound in an endo fashion in both ArsR and ArsD proteins.

Scheme 1.

In general, the role of the lone pair for protein recognition of Pb(II) or As(III) has not been considered. Recently, Raymond and coworkers have explored stereognostic recognition of oxo anion of uranyl,[29] vanadyl[30] and osmyl[31] by using appended H-bond donors in synthetic chelators. In our case, by analogy, one can imagine two distinctly different processes whereby the lone pair could influence metal affinity at a site. The first is in a stereognostic sense in which the lone pair might serve as a hydrogen bond acceptor with a second coordination sphere residue. This interaction would be stabilizing for the ion at this binding site. Alternatively, a large, diffuse lone pair could suffer from steric clashes with bulky hydrophobic residues that are proximal to the metal binding site. This type of interaction would be destabilizing.

A recent analysis of the X-ray crystal structures of the apo and As(III) bound forms of CSL9C directly addressed this latter point.[32] It was found in the apo protein that the leucine layer on the side of the cysteines which would allow complexation of As(III) as the exo isomer (5th position of the sequence) was well packed, leaving little room for the lone pair of this ion. In contrast, the layer of leucines at position 12 were oriented in such a way as to leave a pocket that could accommodate the As(III) lone pair if the ion bound in the endo conformation. The metallated As(III)(CSL9C)3 adopted the endo structure with the lone pair oriented toward the C-termini of the helices exploiting this preassembled cavity. In related studies, it was demonstrated that Cd(II), which is thought to form a mixture of trigonal planar Cd(II)S3 and 4-coordinate, pseudotetrahedral exo CdS3(OH2) with TRIL16C could be biased to form exclusively exo Cd(II)S3(OH2) if the leucine in the 12th position was altered to the less sterically demanding alanine residue. In contrast, the substitution of d-leucine for l-leucine at the 12th position of the sequence (TRIL12dLL16C) caused bound Cd(II) to adopt exclusively a trigonal planar structure. These observations suggest that metal binding to the CoilSer and TRI designed peptides may be controlled by modifying the second coordination sphere environment.

In this article we adopt an experimental and computational strategy to assess the viability of the lone pair steric hindrance hypothesis in order to understand the role of the second sphere coordination environment on metal binding affinities of Pb(II) and As(III) in detail. These studies were performed utilizing three stranded coiled coil peptide families TRI and Coil Ser. The sequences of the specific peptides are provided in Table 1. We find that steric factors significantly influence metal ion stability and preferred coordination geometries.

Table 1.

Peptide Sequences used in this study.

| Peptide | Sequence

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a b c d e f g | a b c d e f g | a b c d e f g | a b c d e f g | ||

| CoilSer | Ac-E | WEALEKK | LAALESK | LQALEEK | LEALEHG-NH2 |

| CSL9C | Ac-E | WEALEKK | CAALESK | LQALEEK | LEALEHG-NH2 |

| CSL16C | Ac-E | WEALEKK | LAALESK | CQALEEK | LEALEHG-NH2 |

| CSL12AL16C | Ac-E | WEALEKK | LAAAESK | CQALEEK | LEALEHG-NH2 |

| TRI | Ac-G | LKALEEK | LKALEEK | LKALEEK | LKALEEK G-NH2 |

| TRIL16C | Ac-G | LKALEEK | LKALEEK | CKALEEK | LKALEEK G-NH2 |

| TRIL12AL16C | Ac-G | LKALEEK | LKAAEEK | CKALEEK | LKALEEK G-NH2 |

| TRIL2WL16C | Ac-G | WKALEEK | LKALEEK | CKALEEK | LKALEEK G-NH2 |

| TRIL2WL12AL16C | Ac-G | WKALEEK | LKAAEEK | CKALEEK | LKALEEK G-NH2 |

| ACA | ALAAACAALA | ||||

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and Methods

Fmoc (N-α-(9-Fluorenyl methyloxycarbonyl)) protected amino acids, MBHA Rink Amide resin, N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) and 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) were purchased from AnaSpec, diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), acetic anhydride, pyridine were purchase from Aldrich, and N-methylpyrrolidinone (NMP) was supplied from Fisher Scientific. N-terminus of all amino acids were protected by Fmoc whereas side group are protected as follows: Cys(Trt), Glu(OtBu), Lys(Boc), Trp(Boc). There were no side protecting group for Ala and Leu. All chemicals were used as received without any further purification.

2.2. Peptide Synthesis and Purification

All peptides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 433A peptide synthesizer by using standard Fmoc/tBu-based protection strategies on Rink Amide MBHA resin (0.25 mmole scale) with HBTU/HOBt/DIEPA coupling methods,[33] and purified and characterized as described previously.[34]

2.3. Electronic Absorption and CD Spectroscopic Studies

All UV/Vis absorption measurements were carried out on Cary 100 using quartz cuvette (1 cm path lengths), 100 mM Tris.HCl buffer at pH 8.0. All reagents or buffer solutions were degassed with argon for at least 30 min before the preparation of any solution. The stock solution concentrations were determined by using Ellman’s test.[35] A 60 μM peptide monomer (20 uM peptide trimer) was prepared and 1/3 equiv of Pb(NO3)2 per monomer was added to the peptide solution at pH 8.0. The pH of the metallopeptides was readjusted by the addition of small aliquots of dil. HCl or NaOH. The spectra were recorded in the range of 200 nm to 450 nm. Metal binding titrations of the peptides were carried out by adding small aliquots of Pb(NO3)2 into a peptide solution (3.0 mL; 60 μM monomer) in 100 mM TrisHCl buffer at pH 8.0. The absorbance due to the peptide was subtracted from each spectrum so that the observed spectrum is due to the formation of metallopeptide only. The binding constant was calculated by fitting the data to a 1:1 binding model (trimer/metal ion) as previously reported by Matzapetakis et al.[36]

All CD experiments were carried out on an Aviv model 202 circular dichroism spectrometer, equipped with an automated titration assembly. CD spectra of peptides and metallopeptides were recorded in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) at 25 °C. Mean residue ellipticities, [θ], were calculated using the equation [θ] = θobs/(10lcn), where θobsd is the ellipticity measured in millidegrees, l is the cell path length in centimeters, c is the molar concentration of peptide, and n is the number of residues in the peptide. To examine the unfolding of the peptide by GdnHCl, two stock solutions containing 10 μM peptide monomer in 10 mM Tris.HCl buffer (pH 8.0) were prepared, one with 8.5 M GdnHCl (15 mL, final GdnHCl conc ~7.6) and one without (2 mL). The solutions were mixed in various proportions to produce samples with different Gdn.HCl concentrations, and after equilibration for 2 minutes, the ellipticity at 222 nm was measured. Percentage helicity was calculated by assuming ellipticity of a 100% helical peptide [θ]222 = −35,500 deg cm2 dmol−1.[37]

2.4. Trp Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Fluorescence quenching experiments were carried out on a Fluorimax-2 Spectrophotometer with an excitation wavelength set at 280 nm and emission range from 295 to 450 nm. The excitation and emission bandwidth were adjusted to 10 nm. The fluorescence spectra were recorded in 10 mM TrisHCl buffer (pH 7.5) using a 1 cm path length fluorescent quartz cuvette. Pb(II) quenching studies was performed by adding 0.1 equiv of a concentrated solution of Pb(NO3)2 (0.5 to 1 μL at each addition) to a 90 nM peptide monomer (30 nM peptide trimer, 3 mL) and stirred for 3 min followed by a 2 min equilibration time. All fluorescence intensities were normalized so that 100 normalized unit of fluorescence intensity corresponds to 30 nM of unquenched peptide trimer. Then the fluorescence quenching was measured. The binding constants were calculated using a nonlinear least squares fit to the following equation[38] assuming a 1:1 peptide trimer/metal binding model [Pb(II) + 3 Peptide ⇄ Pb(Peptide)3].

| (1) |

where, I is the observed fluorescence intensity, IML is the limiting value below which the fluorescence will not decrease due to the saturation, K is the Pb(II) binding constant, CL and CM are the total molar concentration of peptide and added metal ions respectively.

2.5. 207Pb NMR Spectroscopy

All NMR samples were prepared by dissolving ~ 25 mg of the pure lyophilized and degassed peptide in 500 μL of 10% D2O/90%H2O under a nitrogen atmosphere. The peptide concentration was determined by using Ellman’s test.[35] Metallopeptides were prepared by the addition of a calculated amount of isotopically enriched 207Pb(NO3)2 (92.4%, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, TN). The pH of the metallopeptide solutions were adjusted by the addition of KOH/D2O and HCl/D2O. All 207Pb NMR spectra were recorded at frequency of 104.31 MHz on a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer at room temperature (25°C) using 60° pulses, a 20 ms relaxation delay, and a 20 ms acquisition time (spectral width 166.6 KHz). A linear prediction was performed to remove the noise, and the real FID was determined before the data processing. After zero-filling, the data (16 K data points) were processed with an exponential line broadening of 200–250 Hz using the software MestRe-C.[39] The 207Pb NMR chemical shifts are reported downfield from tetramethyllead (δ = 0 ppm; toluene) using 1.0 M Pb(NO3)2 salt (natural) as an external standard (δ = −2990 ppm, D2O, 25°C; relative to PbMe4). Therefore, the reported 207Pb signals are the results of observed signals plus 2990 ppm.

2.6. Computational Methods

DFT has been employed to investigate the coordination properties of the As(III) and Pb(II) ions in a trigonal pyramidal sulfur environment. The design of simplified models of the [As(III)(CSL9C)3] and [Pb(II)(CSL9C)3] systems for DFT calculations was driven by the kind of processes occurring within the three-strand coiled coil that were investigated in this study: preference for endo or exo coordination of As(III) and Pb(II) ions. Due to the very large size of the systems, (762 atoms, excluding ions and water molecules), a simplified peptide model had to be used to perform QM calculations. In particular, the side chains of the coordinating core portion - ALEKKCAALE- in the X-ray [As(III)(CSL9C)3] structure have been replaced with ALAAACAALA (hereafter referred to as ACA). In this way the features of the original coiled coil which are relevant for the purposes of the present study have been preserved. In fact, the charged side chains of E and K residues in CSL9C are oriented outside the peptide envelope and are important for inter-coil interactions and aggregation.[27] Therefore, the substitutions E,K→A are not expected to affect the structural properties of regions embedded inside the coiled coil, where ion coordination occurs. Peptidic ends have been kept neutrally charged (i.e., N-terminal= H2N-; C-terminal= HOOC-) in order to prevent artificial interactions between opposite charged regions. Moreover, alanine side-chains are known to favor the alpha-helix conformation and therefore the introduced substitutions are not expected to affect the outer framework of the coiled coil. The selected model preserves the chemical features of the first coordination sphere of As(III) and Pb(II) ions, and includes all Leu residues that might be involved in secondary bond interactions.

The generalized gradient approximated (GGA) B-P86 functional[40] has been selected for its widespread use in computational investigations of bio-inorganic systems and for its capability, when coupled to the Resolution of Identity method,[41] of significantly reducing computational costs without reducing accuracy. Two basis sets have been used to study the peptide systems:

triple-ζ valence plus a double polarization function (TZVPP) on As, Pb and S atoms (i.e. all atoms defining the first coordination sphere of the cation). In Pb containing structures a relativistic effective-core potential (RECP: ecp-78-mwb; 78 core electrons; lmax=3) has been used to model the inner and inert core electrons of Pb, whereas the TZVPP basis set has been used for Pb valence electrons.

double-ζ plus a polarization functions (DZP) for all C, O, N and H atoms, which form all the remainder of the peptide envelope.

The dual quality basis set choice is motivated by the large size of the peptide systems, which feature up to 364 atoms and 3669 contracted basis functions for the SCF calculations. In addition, a DZP basis set is known to be an acceptable compromise between accuracy and efficiency.[42] Solvent contributions to the energy difference between the endo and the exo coordination modes have not been taken into account. In fact, the As(III) system has a neutral global charge and there are no charged amino acids outside the first coordination sphere. Concerning the Pb(II) system, even though it is anionic, it should be noted that the negative charge is spread over a wide molecular volume. More importantly, the hydrophobic nature of the coiled coil inner environment should exclude the presence of water molecules from the region where metal coordination takes place. This assumption is confirmed by the X-ray structures of the apo and metallated forms of these peptides.[27, 32] No atom of the model has been constrained or fixed to its initial X-ray position during the energy minimization process. Small models (vide infra) have been optimized using a triple-ζ basis set plus a double polarization function (TZVPP).

3. Results

3.1. Spectroscopic Studies

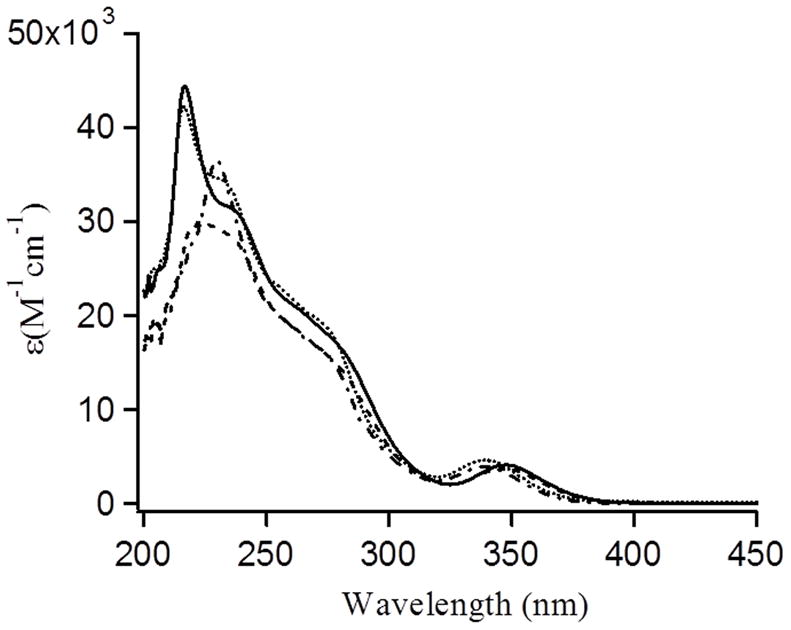

3.1.1. Pb(II)-thiolate Charge Transfer Complexes

Each peptide was synthesized in good yield using standard solid phase peptide synthesis followed by HPLC purification and lyophilization.[43] Addition of 1.0 equivalent of Pb(NO3)2 to monosubstituted TRI peptides (100 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0) gave rise to several well-resolved bands due to the ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) excitations [S(3p) → Pb(6p)(II) transitions].[36, 44] The bands around ~345 nm and two prominent shoulders at ~ 278 nm and 235 nm are consistent with the general absorption profiles for PbS3 geometry in the Pb-bound TRI peptide family and related Pb(II) protein complexes.[36] All metallopeptides studied in this paper, Pb(TRIL16C)3, Pb(TRIL12AL16C)3, Pb(TRIL2WL16C)3, Pb(TRIL2WL12AL16C)3 produced similar LMCT bands at pH 8.0 (100 mM TrisHCl buffer) indicating a similar PbS3 coordination environment (Figure 1, Table 2).[36, 44a] The metal binding stoichiometry of TRIL12AL16C was monitored by the addition of a small aliquots of Pb(NO3)2 into a 60 μM solution of TRIL12AL16C (20 μM trimer) in TrisHCl buffer at pH 8.0. From titration experiments, it was observed that the addition of 1 equivalent of Pb(II) affords complete coordination of Pb(II) to TRIL12AL16C peptide trimer indicating 1:1 Pb(II)/trimer stoichiometries. The titration curves were fit to a 1:1 metal/trimer binding model[36] and the fit yielded the binding constants Ka of 5.6(±1)×108M−1 (see Figure S1). In a previous study by Matzapetakis, an ~ 40 fold lower Pb(II) binding constant was estimated for TRIL16C (Ka = 1.2 ×107M−1) using UV/Vis spectroscopy.[45] These values were known to be at the edge of the sensitivity for determination of accurate binding constants so establish the binding constants precisely, we utilized the more sensitive Trp fluorescence quenching experiments described here (vide infra).

Figure 1.

UV/Vis spectra of Pb(TRIL16C)3 (solid line); Pb(TRIL12AL16C)3 (dot line); Pb(TRIL2WL16C)3 (dash line) and Pb(TRIL2WL12AL16C)3 (dash-dot line) at pH 8.0 in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (20 μM Pb(NO3)2 was added to the 60 μM peptide monomer solution).

Table 2.

UV-Vis data of Pb-Pep3.

| Metallopeptides | λ, nm (ε, M−1cm−1) |

|---|---|

| Pb(TRIL16C)3 | 348 (4,200)p; 275 (18,020)s; 240 (30,300)s; 217 (44,400)p |

| Pb(TRIL12A.L16C)3 | 340 (4,650)p; 275 (18,670)s; 235 (33,650)s; 217 (42,200)p |

| Pb(TRIL2WL16C)3 | 345 (3,740)p; 275 (15,750)s; 225 (29935)p |

| Pb(TRIL2WL12AL16C)3 | 340 (3,940)p; 275 (15,800)s; 230 (36,535)p |

p = peak, s = soulder

3.1.2. Circular Dichroism spectroscopy

The impact of replacing a leucine by alanine at the 12th position of TRIL16C (TRIL12AL16C) has previously been described[46] whereas the peptides with tryptophan substituted in the 2nd position are newly reported. These tryptophan containing constructs more closely resemble the CoilSer peptide family whose cysteine substituted derivatives are known to bind As(III), Pb(II), Cd(II) and Hg(II), in a similar manner as the TRI peptides.[27, 34, 47] Analysis of the CD spectra indicate that the structures of TRIL16C and TRIL2WL16C are similar,[37] that both peptides are nearly fully folded (Figure S2) and that TRIL2WL12AL16C is similarly stable based on guanidinium hydrochloride (GdnHCl) denaturation titrations which exhibit well-defined unfolding transition at [Gdn.HCl]1/2 ≈ 2.5 M by TRIL2WL16C versus [GdnHCl]1/2 ≈ 1.0 M for TRIL12AL16C and TRIL2WL12AL16C. As previously reported, the Leu→Ala substitution destabilized the peptide folding; however, the substitution of Leu at the 2nd position by a Trp does not significantly destabilize the peptide folding/stability. Therefore, we were able to incorporate Trp into the TRI peptide in order to complete Trp quenching experiments.

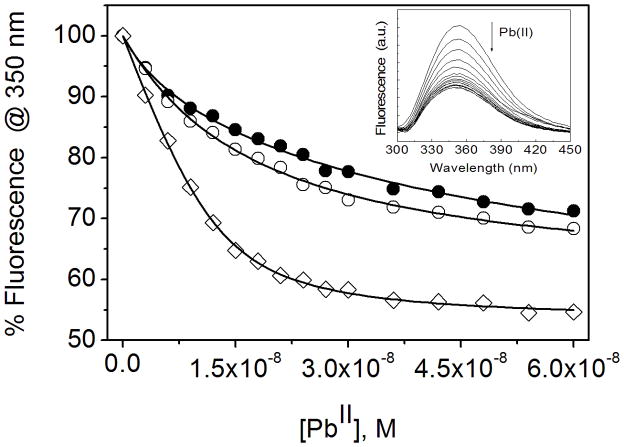

3.1.3. Trp Fluorescence Quenching and Binding Constants

The presence of Trp in these peptides allowed us to determine the relative metal binding affinity by using Trp fluorescence quenching. Trp quenching is due to the non-radiative energy transfer from the excited state of Trp to the ligand field manifold of the bound Pb(II). The fluorescence spectra of 90 nM peptide monomer solution (30 nM trimer) in 10 mM TrisHCl buffer at pH 7.5 shows a broad emission band with the maximum fluorescence centered at ~ 350 nm (Figure 2). The fluorescence intensity decreases upon the addition of small aliquots of Pb(NO3)2 and become saturated after the addition of 1 equivalent of Pb(II) per trimer of peptide. The binding constant was determined by fitting the data in equation 1 (experimental section). The binding constant of Pb(II) for CSL12AL16C (Ka = 1.1(0.2) × 109 M−1) is ~ 4–5 fold higher than that of CSL9C (Ka = 2.1(0.4) × 108 M−1) and CSL16C (Ka = 3.1(0.6) × 108 M−1). Similarly, TRIL2WL12AL16C (Ka = 8.1(1) × 108 M−1) has ~ 5 fold higher affinity than that of TRIL2WL16C (Ka = 1.7(0.6) × 108 M−1) (Table 3, Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Change in fluorescence intensity upon binding of Pb(II) to the peptide CSL9C (filled circle), CSL16C (open circle) and CSL12AL16C (open square) (30 nM trimer). The Trp was excited at 280 nm and the fluorescence quenching was traced at 350 nm. The curves represent the best fit to the Equation 1 by a non linear least squares analysis using ORIGIN software. In inset fluorescence quenching spectra were shown for the addition of Pb(II) to CSL12AL16C.

Table 3.

Pb(II) binding constants obtained from the tryptophan fluorescence quenching experiments for the peptides with or without a hole above the metal binding site.

| Peptide | Pb(II) Binding constant (Ka) |

|---|---|

| CSL9C | 1.1(0.2) × 109 M−1 |

| CSL16C | 3.1(0.6) × 108 M−1 |

| CSL12AL16C | 1.1(0.2) × 109 M−1 |

| TRIL2WL16C | 1.7(0.6) × 108 M−1 |

| TRIL2WL12AL16C | 8.1(1) × 108 M−1 |

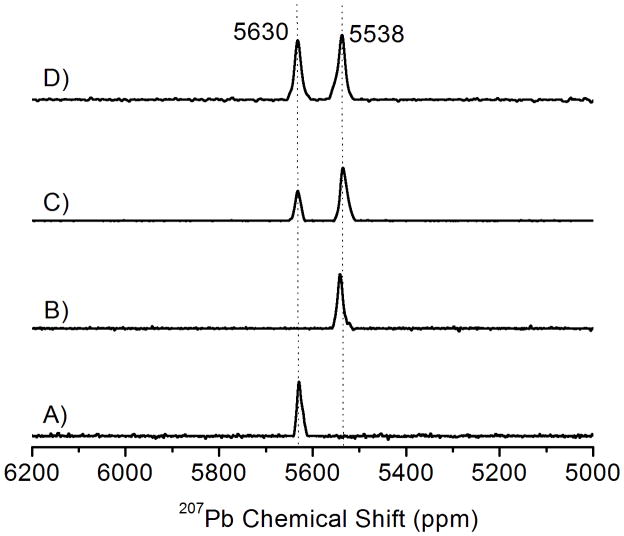

3.1.4. 207Pb NMR Spectroscopy

The higher binding affinity and the selective binding of Pb(II) with the a site (a sites are the first residue of each heptad and d sites are the fourth, the sulfur atoms in an a site are oriented towards the interior of the coiled coil and preorganized for metal binding whereas the sulfur atoms in d sites are more aligned with the helical interface) peptide with a hole above is further assessed by 207Pb NMR spectroscopy. Previously, we reported 207Pb NMR in a homoleptic thiol environment of a designed protein,[34] in glutathione and in zinc fingers.[48] As shown in Figure 3 (spectra A and B), both Pb(CSL9C)3− and Pb(TRIL12AL16C)3 display a sharp Pb-NMR signal at 5630 and 5538 ppm respectively which are characteristic Pb-signals for a PbS3 environment in the a site and a site with a hole above the metal binding site.[34] The chemical shift observed for Pb(CSL9C)3− is similar with that of Pb(CSL16C)3− (δ = 5612 ppm).[34] When 1 equivalent of Pb(NO3)2 was added to the mixture of CSL9C and TRIL12AL16C, two peaks with different intensities are observed. The peak at 5630 ppm corresponds CSL9C (a site) and the peak at 5538 ppm corresponds for TRIL12AL16C (a site with a hole above). As shown in Figure 3C, only about 33% of Pb(II) binds with CSL9C and about 66% Pb(II) binds with TRIL12AL16C. After the addition of another equivalent (2 equivalent in total) of Pb(II), the Pb-signal for both sites increases and become virtually equal intensity (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

207Pb NMR Spectra of Pb(II) bound peptides showing the selective binding of Pb(II) to the peptide with a hole above the metal binding site. (A) Pb(CSL9C)3−, (B) Pb(TRIL12AL16C)3, (C) Equimolar ratio of CSL9C and TRIL12AL16C with 1 equivalent of Pb(NO3)2, (D) Equimolar ratio of CSL9C and TRIL12AL16C with 2 equivalent of Pb(NO3)2. The concentration of metallopeptides used is ~ 5 mM. All spectra were recorded at room temperature (25°C) for 2 hr by using isotopically enriched Pb(NO3)2 (pH =7.45 (±0.05).

3.2. Computational Study

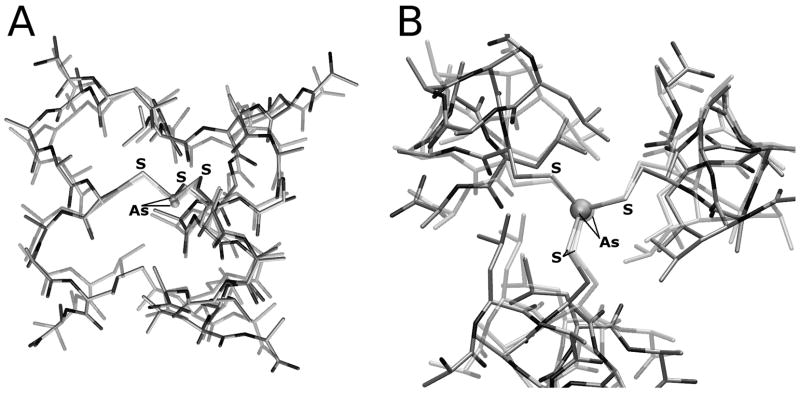

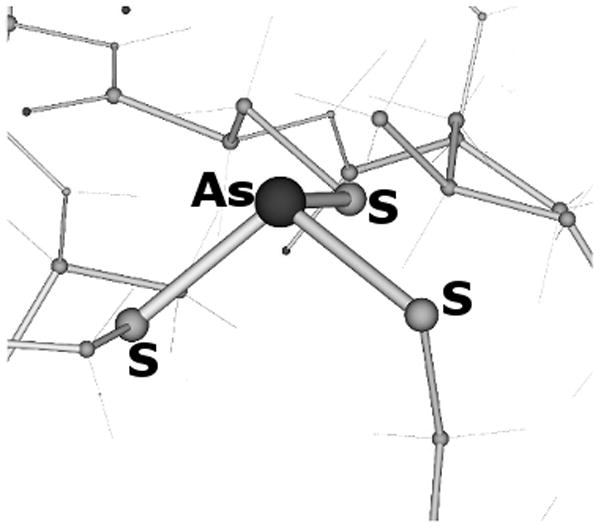

3.2.1. As(III) coordination

The first step of our computational study was the validation of the adopted model (referred to as [As(III)(ACA)3] in the following, see Computational Methods) and level of theory used to describe the experimental [As(III)(CSL9C)3] system. The DFT optimized structure of an [As(III)(ACA)3] model characterized by endo coordination of the As(III) ion, as observed in [As(III)(CSL9C)3], is very similar to the corresponding experimental structure (RMSD computed on heavy atoms common to X-ray and DFT systems = 0.095 nm; Figure 4). In particular, a very good matching between the DFT and X-ray As(III) coordination environment was observed (average DFT As-S bond distance = 2.289 Å versus 2.28 Å in the X-ray structure; average S-As-S angle = 95° versus 90° in the X-ray structure).

Figure 4.

Side view (A) and top-down view (B) of the [As(III)(ACA)3] optimized structure (opaque) overlaid with the corresponding region of [As(III)(CSL9C)]3 (transparent).

After validation of the computational protocol, we have studied [As(III)(ACA)3] structures in which the As(III) ion binds in a fashion different from that observed in the [As(III)(CSL9C)3] X-ray structure (Scheme 1). It must be noted that in the configurations labeled b, the cysteine side chains involved in As(III) binding have a conformation which is known to be disfavored.[43] Nonetheless, the exo and endo b configurations are relevant in the context of the present investigation since they feature a different orientation of the As(III) lone pair with respect to the endo a (which corresponds to the X-ray structure) and exo a configurations (Scheme 1).

It turned out that both [As(III)(ACA)3] models characterized by the endo b or exo a configurations are 4.5 kcal/mol higher in energy relative to the structure observed experimentally. In addition, it is worth noting that the [As(III)(ACA)3] optimization started from the exo a configuration converged to an optimum geometry in which two out of three cysteine residues bind As(III) in an endo fashion (Figure 5 and Figure S4).

Figure 5.

As(III) coordination environment of the [As(III)(ACA)3] complex, as obtained after DFT optimization started from a structure featuring the exo a coordination geometry.

DFT optimization of a [As(III)(ACA)3] model featuring the exo b configuration resulted in large and unrealistic distortion of the structure, mainly due to strong repulsion between the As(III) lone pair and the leucine layer located at the C terminus of the coiled coil.

To evaluate quantitatively the role played by the leucine residues on the binding mode of the As(III) lone pair in [As(III)(ACA)3], we have studied a [As(III)(ACA)3] variant in which the Leu residue closer to the N-terminus of the ALAAACAALA peptide (corresponding to the residue forming the leucine 5 layer in [As(III)(CSL9C)3]), has been replaced with Ala. It turned out that in the L→A system the favored structure is characterized by exo a coordination of the As(III) ion, which becomes 4.9 kcal/mol lower in energy than the endo a coordination mode.

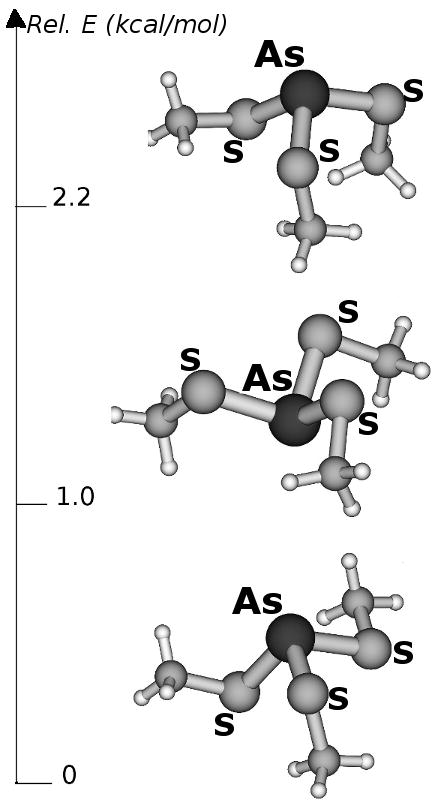

With the aim of further studying factors affecting As(III) coordination geometry, we have also studied smaller model systems. The DFT structures of [As(III)(CH3S)3], which is the simplest conceivable model of the [As(III)-(Cys)3] coordination environment observed in [As(III)(CSL9C)3], are shown in Figure 6. The [As(III)(CH3S)3] isomers differ for the relative orientation of the methyl groups. We observe that the isomer featuring three axial methyl groups does not correspond to an energy minimum, whereas the rotamer featuring one exo and two endo methyl groups is the lowest energy structure of the set.

Figure 6.

Computed energy differences (kcal/mol) and structures of [As(III)(CH3S)3] isomers.

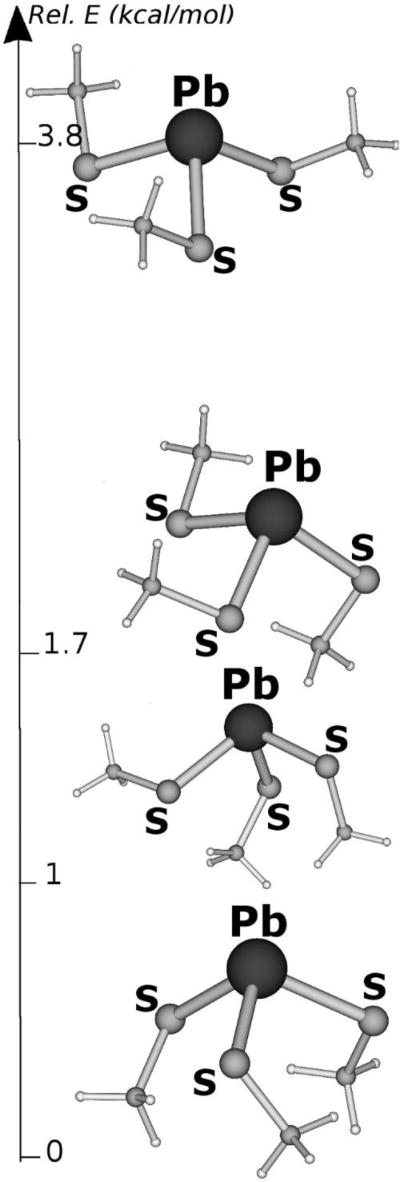

3.2.2. Pb(II) coordination

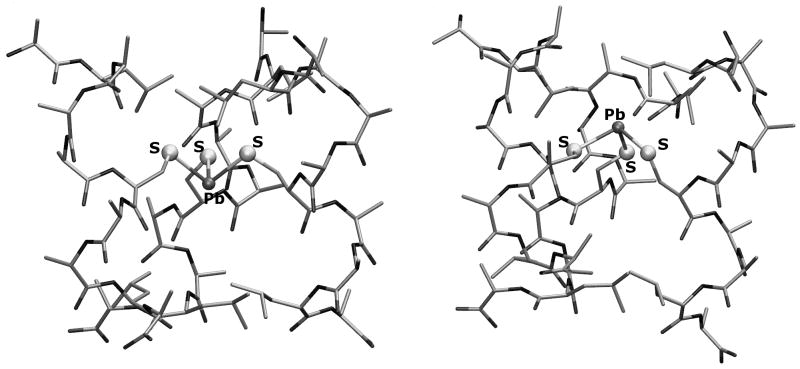

The same computational protocol used for the As(III)-containing systems has been used to investigate the [Pb(II)(ACA)3]− model. DFT results indicate that the structure characterized by the endo a coordination mode is preferred over the exo a configuration by 3.3 kcal/mol (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

DFT optimized geometries of [Pb(II)(ACA)3]− isomers characterized by endo a (left) and exo a (right) Pb(II) coordination environment.

The mean value of the Pb-S bond distances is 2.715 Å both in the endo a and exo a configurations which compares to 2.64 Å for model compounds and EXAFS data on Pb(II) bound to TRI peptides.[36, 49] The mean value of the S-Pb-S valence angle in the [Pb(II)(ACA)3] endo a configuration is 94°, whereas in the exo a form the corresponding angle is 98°. Notably, differently from the corresponding As(III) system, during optimization of the exo a isomer, no rearrangement of the cysteine side chains from exo to endo orientation was observed. DFT optimization of [Pb(II)(ACA)3]− structures characterized by the endo b or exo b configurations (see Scheme 1) led to large distortions of the coiled coil structure (data not shown).

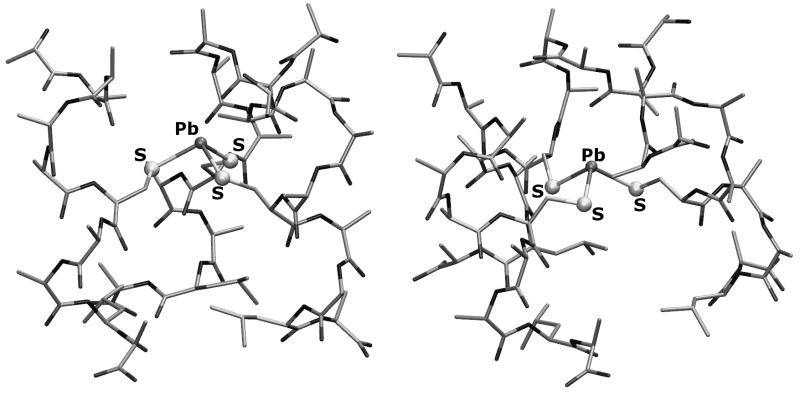

In order to evaluate the role of the leucine side chains on the Pb(II) coordination mode in [Pb(II)(ACA)3] quantitatively, we have also studied a [Pb(II)(ACA)3] variant in which the Leu residue which is closer to the N-terminus of the ALAAACAALA peptide was replaced with Ala. In the L→A variant the only stable low energy structures correspond to the exo a and endo b configurations (Figure 8; see Scheme 1 for exo and endo labelling). In these two structures, which differ by less than 0.4 kcal/mol (in favor of the former), the stereochemically active lone pair of Pb(II) is directed toward the N-terminus of the three-stranded coiled coil.

Figure 8.

Exo a (left) and endo b (right) configurations in the optimized [Pb(II)(ACA)3]− structure in which Leu residues have been replaced with Ala.

In analogy with the As(III) models, the small [Pb(II)(CH3S)3]− system has been investigated to explore which coordination mode is preferred by the [Pb(II)-S3]− moiety in absence of the peptide environment. The DFT optimized structures and relative stability of [Pb(II)(CH3S)3]− isomers are shown in Figure 9. It turned out that isomers characterized by exo orientation of the methyl groups are favored, with the isomer featuring all exo methyl groups corresponding to the lowest energy structure.

Figure 9.

Lowest energy structures of [Pb(II)(CH3S)3]−. Energies are expressed in kcal/mol.

4. Discussion

The present investigation was specifically aimed at evaluating the importance of the second sphere coordination environment of As(III) and Pb(II), bound to the cysteine residues, for defining the recognition of these ions within designed three stranded coiled coil peptides.[27, 34] More generally our study is a contribution to highlight and rationalize further subtle factors affecting the coordination geometry of heavy main group elements in proteins and supramolecular systems. Indeed, in the process of developing new supramolecular coordination compounds, Johnson and collaborators have already thoroughly explored the role played by weak attractive forces, such as As···π interactions and secondary bonding interactions, in trigonal-pyramidal As(III) complexes,[28b] demonstrating that such interactions can dramatically affect the coordination geometry of As(III) in thiolate complexes.[28a, 50] In particular, while exohedral coordination is generally observed in As(III) compounds, the intramolecular As···π interactions in As2(L)3 and As2(L)2Cl2 complexes in which L is an aromatic ligand was shown to induce endohedral directionality of the As(III) stereochemically active lone pair.[51] The nature and strength of the interaction between the stereochemically active lone pairs of As(III) (and other heavier main group elements) with aromatic rings was also studied using quantum chemical methods.[28b, 52] Moreover, secondary bonding interactions between main group elements and heteroatoms such as O, N, S or halogens have also been shown to affect coordination geometry.[53]

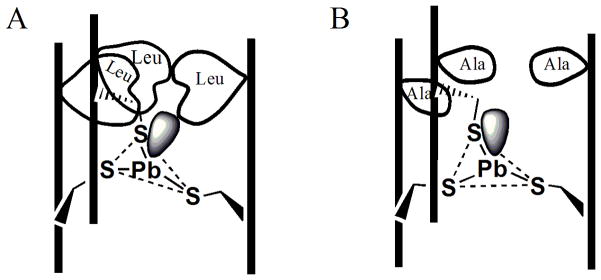

Unlike these supramolecular systems, π or secondary bonding interactions cannot take place in the hydrophobic inner core of the [As(CSL9C)3] and [Pb(CSL9C)3] systems. Nevertheless, using X-ray crystallography, As(III) was proven to be coordinated in an endohedral fashion in such peptide systems, leading to the proposal that the steric repulsion between the stereochemically active lone pair of As(III) or Pb(II) and the bulky side chain of a layer of leucine residues can affect the ion coordination geometry.[27, 32, 34] Furthermore, it is reasonable that such steric encumbrance could serve as a contributing factor to heavy metal recognition in proteins. As determined in these studies, the binding constant (Table 3) of Pb(II) for CSL12AL16C is ~ 4–5 fold higher than that of CSL9C and CSL16C. Similarly, TRIL2WL12AL16C has ~ 5 fold higher affinity than that of TRIL2WL16C. The enhanced stability constant of Pb(II) to TRIL12AL16C as compared with TRIL16C is consistent with the easier accommodation of the stereochemically active lone pair of Pb(II) into the vacant hole above the cysteine layer (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram showing how the substitution of a Leu layer at position 12 by Ala (Leu → Ala) creates a hole above the cysteine layer. (A) Leucine side chain and Pb(II) lone pair steric encumbrance tilts the plane so that lone pair can fit within the three stranded coiled coil (3SCC). (B) Leu → Ala substitution added a space to accommodate a lone pair of Pb(II). The vertical lines represent the peptide backbone of 3SCC.

We already have shown the site selectivity of Pb(II) between a peptide with an a site with a hole vs a d site using the peptide Grand-L12AL16C.L26C (see Table 1 for the location of a and d sites in each peptide).[34] Furthermore, 207Pb-NMR experiments for TRIL12C + TRIL12A.L16C show when a half equivalent of Pb(II) was added, it completely binds to the a site with a hole, and addition of a second half equivalent goes in the d site (after the a site with a hole is saturated).[54] Site selectivity was independently assessed for competition with a site peptides using 207Pb NMR (Figure 3) by generating a mixture between a regular a site peptide and an a site peptide with a hole above the sulfur layer. Addition of 1 equivalent of 207Pb(II) to 1 equivalent of (CSL9C)3 yielded a single resonance at 5630 ppm for Pb(CSL9C)3− Using the same stoichiometry, a significant upfield shift (5538 ppm) was observed when Pb(TRIL12AL16C)3− was examined. As previous studies have shown that combinations of two different TRI peptides with a site cysteines form statistical mixtures of 3-stranded coiled coils,[47] we have chosen the CoilSer (CS) and TRI peptides for these studies as the formation of heteromeric 3-stranded coiled coils are avoided when these peptides are mixed. When equimolar solution of (CSL9C)3 and (TRIL12AL16C)3 was probed using enough 207Pb(II) to fill only half of the available protein binding sites, a mixture of these two resonances was observed (Figure 3C); however, the spectrum shows a marked preference (> 5-fold at equilibrium) for Pb(II) complexation to the peptide containing the alanine layer. When sufficient Pb(II) was added to fill all available protein binding sites, equivalent signals for both complexes were obtained. These experiments indicate that Pb(II) preferentially binds with the site in which the lone pair can be accommodated without steric encumbrance. One might expect similar behavior for As(III), although such measurements have not been completed due to the slow kinetics of binding which make stability constant determination difficult.

Metal ions that do not have a lone pair, such as Cd(II), but which have a fourth ligand that occupies the space where the lone pair would be found also exhibit site selectivity. We have shown that analogous behavior by coordinating one exogenous water molecule yielding a fully 4-coordinated species in TRIL12AL16C, in contrast to a mixture of 3 and 4-coordinate species in TRIL16C, which does not feature a hole above the metal binding site.[55] This Cd-O bond length is estimated to be ~2.45 Å. Penicilamine, when incorporated in the 16 position (TRIL16Pen), causes a change in the packing of the leucine layer in the 12 position that completely blocks the fourth water ligand from binding to Cd(II).[55–56] This observation led to the successful preparation of heterochromic peptides that contained two Cd(II) ions with the first Cd in a fully four coordinate environment and the second in a fully three coordinate environment.[57] It was also shown that there was a >10-fold preference for Cd(II) to enter the four coordinate site rather than the three coordinate position. These observations emphasize the importance of the fourth polyhedral position when a ligand is bound. The work presented here with Pb(II) demonstrates that a similar selectivity is operative when a stereochemically active lone pair is present, even if an additional ligand does not occupy the physical space.

The data presented above demonstrate that whether one considers a lone pair (As(III), Pb(II)) or a small ligand (water on Cd(II)) the second coordination sphere surrounding the ion can define the coordination preference. The 207Pb NMR data convincingly demonstrate the affinity ordering a site with a hole > d site > a site for Pb(II); however, the data do not demonstrate conclusively that the origin of this preference is the accommodation of the lone pair/size of the metal. To test the hypothesis that the interaction between the As(III) or Pb(II) lone pair with the leucine residues in CSL9C is a key factor that affects coordination geometry further, we have carried out a DFT investigation of complexes between As(III) or Pb(II) and a computational model of the peptide CSL9C (ALAAACAALA; referred to as ACA). In addition, we examined a variant in which the Leu residue closer to the peptide N-terminal has been replaced with Ala.

The structure of the computational [As(III)(ACA)3] model is a parallel three-stranded coiled coil which, similarly to the experimental [As(III)(CSL9C)3] system, features two layers of leucine residues. The orientation of the leucine residues in the two layers (referred to as layers 5 and 12 for consistency with previous works) differ, with those in layer 5 more directed toward the center of the coiled coil than those in layer 12.

As(III) binding in [As(III)(ACA)3] and related systems can be characterized either by endohedral or exohedral coordination geometry. Indeed, depending from the cysteine side chains orientation, two endo and two exo binding modes might be envisioned. However, it turned out that lowest energy structures always corresponded to the a endo or exo forms (see Scheme 1), which are characterized by side chain orientation of the cysteine residues observed in analogous protein systems.[43]

The computed energy difference observed comparing different As(III) coordination geometries in [As(III)(ACA)3] is consistent with the experimental observation indicating endo coordination in [As(III)(CSL9C)3]. An iso-energy mapping surface for the appropriate As(III)s,p orbitals in the lowest energy endo configuration is shown as Figure S4. Interestingly, while there are not evident stabilizing factors which favor the As(III) endo form in [As(III)(ACA)3], some unfavorable interactions affecting the exo form are present, due to the peculiar environment of the coiled coil core. In particular, the preference for endo coordination stems from the collision of the stereochemically active As(III) lone-pair onto the leucine layer at the peptide N-terminus (Leu 5 in [As(III)(CSL9C)3]), which occurs only when the As(III)-S3 moiety has an exo configuration. Such an unfavorable interaction is so pronounced that during DFT optimization the As(III)-S3 fragment rotates around an axis which passes through two of the sulfur atoms forming the first coordination sphere of the ion. Nevertheless, such a rearrangement cannot fully relieve the repulsion between the lone pair and the leucine layer.

The influence of the N-terminal leucine layer on the orientation of the stereochemically active As(III) lone-pair, and consequently for the preference of endo binding mode in [As(III)(CSL9C)3], was further supported by the DFT investigation of the variant in which the N-terminal Leu residue of the ACA peptide was replaced with Ala. In fact, in the Leu→Ala variant, exo coordination of the As(III) ion becomes preferred, due to the possibility of accommodating the As(III) lone pair within the cavity formed by the Leu→Ala replacement. The closest As(III)-H-C contacts are shown as Figure S5. In all cases, the interaction is >3.2 Å, with two of the three distances >4 Å. It is possible that there is a very weak stabilizing interaction between the As lone pair and the shorter distance hydrogen atom on alanine; however, it is unlikely that this contributes significantly to the preferred exo configuration. These DFT results show how the coordination geometry of the As(III) ion in a trigonal sulfur based environment can be tailored by the second sphere coordination environment. Exo coordination is preferred when no bump between the As(III) lone pair and aminoacids side chains is present, whereas endo orientation can be obtained when “exo-destabilizing” factors are present, as in the case of the CSL9C system. To enhance the integration in a general conceptual framework the conclusions obtained from the DFT investigation of the [As(III)(ACA)3] systems, the smaller [As(III)(CH3S)3] complex was also studied by DFT. Two main factors, in decreasing order of importance, turned out to affect the As(III) coordination geometry in [As(III)(CH3S)3]: steric interaction between methyl groups and repulsion between the lone pairs of sulfur atoms. In the lowest energy [As(III)(CH3S)3] isomer (Figure 6), the two methyl groups that are oriented in an endo fashion contribute to minimize the CH3-CH3 steric clashing, whereas the repulsive interaction between the sulfur lone pairs is relieved by the exo orientation of the remaining methyl group. The isomer characterized by endo arrangement of all methyl groups pays a moderate energetic penalty due to the orientation of the lone pairs of the three sulfur atoms, which points toward the same region of space. Therefore, even though in the latter [As(III)(CH3S)3] isomer the three methyl groups do not clash, repulsion among the sulfur lone pairs is maximized. In the other [As(III)(CH3S)3] isomers steric clashing between methyl groups becomes even more evident, resulting in higher energy structures. In summary, results obtained studying [As(III)(CH3S)3] show that its conformational properties do not depend significantly from the As(III) lone pair, but instead from steric and electronic interactions involving the ligands. On the other hand, in the [As(III)(CSL9C)3] peptide systems the interaction between the As(III) lone pair and groups outside the ion coordination sphere becomes predominant over inter-ligand interactions.

The effect of the stereochemically active lone pair is even more evident in the model. In fact, endo coordination is also preferred in this system due to the [Pb(II)(ACA)3]− presence of the bulky N-terminal leucine layer, as demonstrated by the observation that in the variant, in which the leucine sidechains closer to the N-terminus have been [Pb(II)(ACA)3]− replaced with alanine residues, the exo binding geometry becomes preferred. In this case, the closest contacts between the Pb(II) ion and the alanine H-atoms are 3.4 to 3.6 Å (shown in Figure S5) with none of these contacts providing stabilization to the configuration. The larger diffusion of the Pb(II) 4p lone pair, relative to the 3p orbital of the As(III) ion, also affects dramatically the coordination geometry of small Pb(II) complexes, such as [Pb(II)(CH3S)3]−. Indeed, the effects of the repulsion between the Pb(II) lone pair and its ligands is well documented by the observation that compounds with low coordination number are generally characterized by hemidirected geometries, in which all ligands are oriented toward one region of a ideal globe centered on the ion. The comparison between DFT results obtained investigating [As(III)(CH3S)3] and [Pb(II)(CH3S)3]− reveals that the repulsion between the lone pair and the ligands in [Pb(II)(CH3S)3]− overcomes all other effects, such as steric clashing between the methyl groups and unfavorable electrostatic interaction among the lone pairs on sulfur atoms, which are operative both in [As(III)(CH3S)3] and [Pb(II)(CH3S)3]−. In other words, the 6p electrons on Pb(II) are so diffuse that they also repel groups belonging to the Pb(II) second sphere of coordination, i.e, methyl groups of thiolate ligands, pushing them toward the same region of space. To emphasize this point, the lowest energy [Pb(II)(CH3S)3]− isomer has all methyl group oriented in an exo fashion.

5. Conclusions

In this study we utilized computational and spectroscopic methods to probe Pb(II) binding to designed three-stranded coiled coil peptides. We also examined the smaller As(III) peptide and small molecule systems using computational methods to resolve the issue of As(III) coordination in proteins raised by our lab recently.[27] The data presented here are in good agreement with the previous studies by us and others. Both As(III) and Pb(II) bind in trigonal pyramidal coordination environments within peptidic frameworks using cysteinate thiolate ligands. In the presence of steric constraints above the lone pair, As(III) found in an exo-mode is destabilized by 4.5 kcal/mol in energy with respect to the endo-binding conformation. This is due to the repulsion between the As(III) lone pair and the layer of bulky Leu residues above the cysteine layer. A 5-fold higher binding affinity of Pb(II) was observed when the steric conflict of Leu was substituted by Ala. This is because more room is accessible to fit the larger diffused Pb(II) lone pair. By showing how secondary bonding interactions (SBIs) and lone pair interaction influence the coordination geometry and binding affinity of the heavy metal ions such as As(III) and Pb(II), we hope to influence the thinking on how proteins such as ALAD and the metalloregulatory protein PbrR691 recognize these main group ions. In general, this work suggests that both ions, when bound to sulfur rich sites, prefer environments that can more easily accommodate the lone pair and can suggest that native proteins that provide this stabilization could have an enhanced affinity on the order of a factor of five to ten. Both ion size and lone pair extension of As(III) and Pb(II) contribute to the ion selectivity. Therefore, this study deepens the understanding of molecular recognition processes involved in human heavy metal toxicity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Virginia Cangelosi and Professor Nathaniel Szymczak for helpful discussion and the National Institute of Health for support of this research (R01 ES0 12236).

Footnotes

An exo coordination mode occurs when the β-carbon of cysteine is located below the plane of the three bound sulfur atoms with respect to the position of the metal as shown in Scheme 1. The endo conformation orients both the β-carbon and the toxic ion on the same side of the three atom sulfur plane. This designation can be applied to each β-carbon such that an individual coordination environment may be referred to as endo, endo, exo when two β-carbons are on the same side of the 3 atom sulfur plane as As(III) and one carbon is on the opposite face. In a simplified nomenclature, one may refer to the ion as being exo or endo when the majority of carbon atoms match the specific designation. Thus for the example given, one would call the As(III) orientation endo since two of the three β-carbon atoms are in the endo conformation.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2000;49:1133–1137. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Rahman MM, Sengupta MK, Ahamed S, Chowdhury UK, Lodh D, Hossain A, Das B, Roy N, Saha KC, Palit SK, Chakraborti D. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:49–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) WHO. Guideline for Drinking Water Quality Recommendation. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Chou WC, Jie C, Kenedy AA, Jones RJ, Trush MA, Dang CV. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4578–4583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306687101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Szivak I, Behra R, Sigg L. J Phycol. 2009;45:427–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2009.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spouches AM, Kruszyna HG, Rich AM, Wilcox DE. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:2964–2972. doi: 10.1021/ic048694q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Godwin HA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:223–227. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Simons TJB. Neurotoxicology. 1993;14:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Warren MJ, Cooper JB, Wood SP, Shoolingin-Jordan PM. Trend Biochem Sci. 1998;23:217–221. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Cullen WR, Styblo M, Serves SV, Thomas DS. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:27–33. doi: 10.1021/tx960139g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lin S, Cullen WR, Thomas DJ. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:924–930. doi: 10.1021/tx9900775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Petrick JS, Bhumasamudram J, Mash EA, Aposhian HV. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:651–656. doi: 10.1021/tx000264z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Simons TJB. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.178_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNeill DR, Narayana A, Wong HK, Wilson DM. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:799–804. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller WH, Schipper HM, Lee JS, Singer J, Waxman S. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3893–3903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Takiguchi M, Achanzar WE, Qu W, Li G, Waalkes MP. Exp Cell Res. 2003;286:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhao CQ, Young MR, Diwan BA, Coogan TP, Waalkes MP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10907–10912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CM, Misra T, Silver S, Rosen BP. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15030–15038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Z, Shen J, Carbrey JM, Mukhopadhyay R, Agre P, Rosen BP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6053–6605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092131899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Rosenberg H, Gerdes RG, Chegwidden K. J Bacteriol. 1977;131:505–511. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.2.505-511.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sanders OI, Rensing C, Kuroda M, Mitra B, Rosen BP. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3365–3367. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3365-3367.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen BP. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:86–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Gyurasics A, Varga F, Gregus Z. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:465–468. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90306-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kala SV, Neely MW, Kala G, Prater CI, Atwood DW, Rice JS, Lieberman MW. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33404–33408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borremans B, Hobman JL, Provoost A, Brown NL, d Lelie Dv. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5651–5658. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5651-5658.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen P, Greenberg B, Taghavi S, Romano C, van der Lelie D, He CA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:2715–2719. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Helmann JD, Ballard BT, Walsh CT. Science. 1990;247:946–948. doi: 10.1126/science.2305262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wright JG, Tsang HT, Penner-Hahn JE, O’Halloran TV. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2434–2435. [Google Scholar]; c) Zeng QD, Stalhandske C, Anderson MC, Scott RA, Summers AO. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15885–15895. doi: 10.1021/bi9817562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen PR, He C. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson JM, Voegtlin C. J Biol Chem. 1930;89:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Delnomdedieu M, Basti MM, Otvos JD, Thomas DJ. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:598–602. doi: 10.1021/tx00035a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cruse WBT, James MNG. Acta Cryst. 1972;B28:1325–1331. [Google Scholar]; c) Polec-Pawlak K, Ruzika R, Lipiec E. Talanta. 2007;72:1564–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Rosen BP. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21084–21089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen PR, Wasinger EC, Zhao J, van der Lelie D, Chen LX, He C. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12350–12351. doi: 10.1021/ja0733890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimoni-Livny L, Glusker JP, Bock CW. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:1853–1867. [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Parr J. Polyhedron. 1997;16:551–566. [Google Scholar]; b) Abu-Dari K, Hahn FE, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:1519–1524. [Google Scholar]; c) Abu-Dari K, Karpishin TB, Raymond KN. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:3052–3055. [Google Scholar]; d) Rupprecht S, Franklin SJ, Raymond KN. Inorg Chim Acta. 1995;235:185–194. [Google Scholar]; e) Rupprecht S, Langemann K, Lugger T, McCormick JM, Raymond KN. Inorg Chim Acta. 1996;243:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaikha TA, Bakus RC, Parkina S, Atwood DA. J Organomet Chem. 2006;691:1825–1833. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrer BT, McClure CP, Penner-Hahn JE, Pecoraro VL. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:5422–5423. doi: 10.1021/ic0010149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Touw DS, Nordman CE, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11969–11974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701979104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.a) Carter TG, Healey ER, Pitt MA, Johnson DW. Inorg Chem. 2004;44:9634–9636. doi: 10.1021/ic051522o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vickaryous WJ, Herges R, Johnson DW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:5831–5833. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.a) Franczyk TS, Czerwinski KR, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:8138–8146. [Google Scholar]; b) Walton PH, Raymond KN. Inorg Chim Acta. 1994;240:593–601. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borovik AS, Dewey TM, Raymond KN. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:413–421. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borovik AS, Bois JD, Raymond KN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1995;34:1359–1362. [Google Scholar]; Angrw Chem. 1995;107:1473–1476. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakraborty S, Touw DS, Peacock AFA, Stuckey J, Pecoraro VL. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13240–13250. doi: 10.1021/ja101812c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan WC, White PD. Fmoc Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neupane KP, Pecoraro VL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8177–8180. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2010;122:8353–8356. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellman GL. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1958;74:443–450. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(58)90014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matzapetakis M, Ghosh D, Weng TC, Penner-Hahn JE, Pecoraro VL. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:876–890. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.a) Chen YH, Yang JT, Chau KH. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3350–3359. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) O’Shea EK, Rutkowski R, Kim PS. Science. 1989;243:538–542. doi: 10.1126/science.2911757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan DK, Weber JH. Anal Chem. 1982;54:986–990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cobas C, Cruces J, Sardina FJ. MestRe-C version 2.3. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela; Spain: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.a) Becke AD. Phys Rev A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Perdew JP. Phys Rev B. 1986;33:8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eichkorn K, Weigend F, Treutler O, Ahlrichs R. Theor Chem Acc. 1997;97:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koch W, Holthausen MC, Baerends EJ. A Chemist’s Guide to Density Functional Theory. Wiley-VCH and John-Wiley & Son; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dieckmann GR, McRorie DK, Lear JD, Sharp KA, DeGrado WF, Pecoraro VL. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:897–912. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.a) Magyar JS, Weng TC, Stern CM, Dye DF, Rous BW, Payne JC, Bridgewater BM, Mijovilovich A, Parkin G, Zaleski JM, Penner-Hahn JE, Godwin HA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9495–9505. doi: 10.1021/ja0424530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jarzecki AA. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:7509–7521. doi: 10.1021/ic700731d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matzapetakis M. PhD thesis. University of Michigan; 2004. Use of heavy metal binding de novo designed alpha-helical peptides as models for understanding metalloproteins; pp. 1–249. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iranzo O, Jakusch T, Lee KH, Hemmingsen L, Pecoraro VL. Eur J Chem. 2009;15:3761–3772. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iranzo O, Ghosh D, Pecoraro VL. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9959–9973. doi: 10.1021/ic061183e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neupane KP, Pecoraro VL. J Inorg Biochem. 2011;105:1030–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christou G, Folting K, Huffman JC. Polyhedron. 1984;3:1247–1253. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pitt MA, Zakharov LN, Vanka K, Thompson WH, Laird BB, Johnson DW. Chem Commun. 2008:3936–3938. doi: 10.1039/b806958a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cangelosi VM, Zakharov LN, Crossland JL, Franklin BC, Johnson DW. Cryst Growth Des. 2010;10:1471–1473. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Auer AA, Mansfeld D, Nolde C, Schneider W, Schurmann M, Mehring M. Organometallics. 2009;28:5405–5411. [Google Scholar]

- 53.a) Starbuck J, Norman NC, Orpen AG. New J Chem. 1999;23:969–972. [Google Scholar]; b) Szymczak NK, Han FS, Tyler DR. Dalton Trans. 2004:3941–3942. doi: 10.1039/b415259j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Barucki H, Coles SJ, Costello JF, Gelbrich T, Hursthouse MB. Dalton Trans. 2000:2319–2325. [Google Scholar]; d) Landrum GA, Hoffmann R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1887–1890. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 1998;110:1989–1992. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neupane KP, Pecoraro VL. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee KH, Cabello C, Hemmingsen L, Marsh ENG, Pecoraro VL. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2006;45:2864–2868. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2006;118:2930–2934. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peacock AFA, Iranzo O, Pecoraro VL. Dalton Trans. 2009:2271–2280. doi: 10.1039/b818306f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iranzo O, Cabello C, Pecoraro VL. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2007;46:6688–6691. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2007;119:6808–6811. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.