Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with alterations in bile acid (BA) signaling. The aim of our study was to test whether pancreatic β-cells contribute to BA-dependent regulation of glucose homeostasis. Experiments were performed with islets from wild-type, farnesoid X receptor (FXR) knockout (KO), and β-cell ATP-dependent K+ (KATP) channel gene SUR1 (ABCC8) KO mice, respectively. Sodium taurochenodeoxycholate (TCDC) increased glucose-induced insulin secretion. This effect was mimicked by the FXR agonist GW4064 and suppressed by the FXR antagonist guggulsterone. TCDC and GW4064 stimulated the electrical activity of β-cells and enhanced cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c). These effects were blunted by guggulsterone. Sodium ursodeoxycholate, which has a much lower affinity to FXR than TCDC, had no effect on [Ca2+]c and insulin secretion. FXR activation by TCDC is suggested to inhibit KATP current. The decline in KATP channel activity by TCDC was only observed in β-cells with intact metabolism and was reversed by guggulsterone. TCDC did not alter insulin secretion in islets of SUR1-KO or FXR-KO mice. TCDC did not change islet cell apoptosis. This is the first study showing an acute action of BA on β-cell function. The effect is mediated by FXR by nongenomic elements, suggesting a novel link between FXR activation and KATP channel inhibition.

During the last decade, it became evident that bile acids (BAs) have much more physiological significance than to simply act as fat and vitamin solubilizers in the gut. They interact with several signaling/response pathways including membrane-associated BA receptors and the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) that is involved in the regulation of glucose, lipid, and BA metabolism and transport (1).

In healthy individuals, the plasma concentrations of BAs significantly increase after an oral glucose tolerance test (2,3). Thus, the increase of BAs during a meal may constitute a signal that coordinates the response of different organs to food intake. Interestingly, human and animal studies suggest that disruption of BA signaling is linked to impaired glucose metabolism (4). The increase in plasma BAs in response to an oral glucose tolerance test is reduced in prediabetics with high fasting insulin concentrations (3). In patients with morbid obesity, postprandial augmentation of plasma BA concentration is much lower than in lean controls (5), and in patients with overt type 2 diabetes mellitus, the bile ejection volume after a meal is reduced (6). Moreover, bile composition and size of the BA pool are changed in diabetic patients, and these alterations may be involved in the pathogenesis of the disease (7,8). In that line, it is interesting to note that BA sequestrants improve glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (9–11). However, it remains unclear how this glucose-lowering effect of BA sequestrants is achieved, and it is currently not possible to predict which BA profiles are beneficial or detrimental in humans.

Animal studies allow deeper insights into this problem. In diabetic mice, BAs can restore glucose homeostasis (12). Metabolomics analysis of mice fed with a high-fat diet that developed insulin resistance revealed diminished concentration of taurocholate in liver and plasma (13). Most animal studies in this field concentrated on the role of the BA receptor FXR in liver and other insulin-sensitive peripheral organs. FXR deficiency leads to insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance in mice (14–16). Accordingly, FXR activation promotes insulin sensitivity (16,17). FXR mRNA levels vary with the nutritional status: fasting increases hepatic FXR expression, whereas high-carbohydrate refeeding reduces expression (18,19). As FXR expression is induced by glucose and decreased by insulin (20,21), a prediabetic status with high insulin output per se may alter BA signaling by changing FXR concentration. Indeed, liver FXR expression is diminished in animal models of diabetes (21). So far, it is not known whether BA signaling in β-cells contributes to glycemic control; however, very recent studies suggest a role for BAs in β-cell function (22,23). These studies demonstrate the presence of FXRs in human and rodent β-cells and β-cell lines. Glucose-induced insulin secretion is enhanced in vitro in human islets and betaTC6 cells after an 18-h incubation with the synthetic FXR ligand 6 alpha-ethyl-chenodeoxycholic acid. The effect is reversed by silencing FXR with small interfering RNA. In vivo administration of BAs delays the onset of diabetes in NOD mice (22). Another study describing FXR expression in β-cells revealed that in lean mice, FXR is predominantly localized in the cytosol but translocates in the nucleus in obese mice (23). FXR-knockout (KO) mice display normal islet architecture and β-cell mass, but the expression of several islet-specific genes is altered. The authors demonstrate that glucose-induced insulin secretion is impaired in FXR-KO islets compared with wild-type (WT) islets; however, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Interestingly, FXR is present in human islets, and the authors suggested that FXR activation protects against lipotoxicity (23).

BAs affect cell viability, but the results are controversial (24,25). For hepatocytes, both induction of apoptosis and prevention against cell damage have been described as depending on the hydrophobicity profile of the BAs. Blocking FXR activation interferes with the cytotoxicity of H2O2 in pheochromocytoma PC12 cells (26). One study performed with RINm5F and β-cells provides evidence that an FXR antagonist prevents cytokine-induced cell damage (27).

The current study was undertaken to test the effect of the BA sodium taurochenodeoxycholate (TCDC) on β-cell stimulus-secretion coupling and viability. Our study shows that BAs exert rapid effects on stimulus-secretion coupling that includes activation of FXR and inhibition of ATP-dependent K+ (KATP) channels.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Cell and islet preparation.

The details are described in (28). FXR-KO mice were described earlier (29) and bred in the animal facility in the Department of Pharmacology, University of Tübingen. Principles of laboratory animal care (National Institutes of Health publication number 85-23, revised 1985) and German laws were followed.

Solutions and chemicals.

The bath solution for electrophysiology and determination of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) was as follows (in mmol/L): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.5 or 20 CaCl2, glucose as indicated, and 10 N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N´-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.4), adjusted with NaOH. For recording of voltage-dependent K+ channel (Kv) currents, 100 μmol/L tolbutamide was added. Pipette solution was (in mmol/L) as follows: 10 KCl, 10 NaCl, 70 K2SO4, 4 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N´N´-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 10 HEPES (pH 7.15), and amphotericin B 250 μg/ml. Pipette solution for inside-out patches and standard whole-cell configuration was (in mmol/L) as follows: 130 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 EGTA, 0.65 Na2ATP, and 20 HEPES (pH 7.15). Bath solution for inside-out patches was (in mmol/L) as follows: 130 KCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 0.5 glucose (pH 7.2). Incubation medium for insulin secretion was (in mmol/L) as follows: 122 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 0.5% BSA (pH 7.4).

Fura-2 AM was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). RPMI 1640 medium was from PromoCell (Heidelberg, Germany), penicillin/streptomycin from GIBCO/BRL (Karlsruhe, Germany), TCDC from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany), and GW4064 from Biozol (Eching, Germany). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) in the purest form available.

Patch-clamp recordings.

Membrane potential and currents were recorded with an EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier using Pulse software (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Single-channel activity was measured at −50 mV. Point-by-point analysis of the currents reveals an open probability (Po) owing to all active channels (N) in the patch and is thus given as NPo. Whole-cell KATP current was evoked by 300-ms voltage steps from −70 to −60 mV. Under these conditions, the current is completely inhibitable by KATP channel inhibitors (30). Kv current was measured by 150-ms voltage steps from −70 to 0 mV. (The protocol for determination of Kslow currents is described in Ref. 31.).

Measurement of [Ca2+]c.

Details are described in (28). β-Cells were loaded with 5 μmol/L Fura-2 (30 min, 37°C). Fluorescence was excited at 340 and 380 nm, and fluorescence emission was filtered (LP515) and measured by a digital camera. Recordings with HEK293 cells stably transfected with Myc-TRPM3alpha2-YFP were performed exactly as reported in Ref. 32.

Measurement of insulin secretion.

Details for steady-state incubations are described in Ref. 28. For perifusions, 50 islets were placed in a bath chamber and perifused with 3 mmol/L glucose for 60 min prior to the experiment.

Immunohistology.

Pancreata and livers were removed and thereafter fixed in paraformaldehyde (2%, 12 h for immunofluorescence; 4%, 48 h for 3.3′-diaminobenzidine [DAB] staining), dehydrogenized by ethanol/xylol, and embedded in paraffin. Pancreas sections (8 µm) were deparaffinized with xylol and rehydrated through gradient-ethanol immersion. Sections were incubated in 0.3% Triton X-100 (30 min) and washed three times with PBS. For antigen retrieval, the sections were incubated in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6) for 15 min before heating them on a hotplate. For DAB staining, sections were directly heated in the microwave (15 min). For immunofluorescence, after washing, slices were blocked with 5% normal goat serum (1 h, room temperature), incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-FXR antibody (1:1000; Perseus Proteomics), followed by 1-h incubation with Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). After washing, sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum (1 h, room temperature) in the dark and incubated with anti-insulin antibody (polyclonal guinea pig anti-insulin, 1:1500; DakoCytomation) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the sections were incubated for 1 h with Cy2-conjugated anti-guinea pig antibody (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at room temperature in the dark. For immunodetection of nuclei, sections were mounted with PermaFluor Aqueous Mounting Medium (ThermoFisher Scientific) containing 1 μg/ml Hoechst dye 33258 (Sigma-Aldrich) on coverslips.

DAB staining.

To reduce background and nonspecific staining, a diluted M.O.M. Kit (Vector Laboratories) was used. Thereafter, anti-FXR antibody (Wako Chemicals; 1:1000 in M.O.M. diluent from Vector Laboratories) was applied at 4°C overnight. Biotinylated secondary antibody (1:250) was added, and immunocomplexes were visualized by the avidin-biotin method (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories) with DAB as chromogen. Sections were mounted in DePeX (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). FXR staining in the liver is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Determination of apoptotic islet cells.

Islet cells were seeded on glass coverslips and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium for 18 h or 7 d with or without TCDC. A minimum of 1,000 cells from three to five different isolations was counted for each condition. Pancreatic islet cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde at 20–25°C for 1 h and washed afterward with PBS. Thereafter, β-cells were permeabilized for 2 min on ice (0.1% Triton X-100 in sodium citrate solution) and washed again. Each sample with fixed islet cells was covered with 50 μl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling (TUNEL) reaction mixture (fluorescein deoxyuridine triphosphate and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and incubated in a humidified atmosphere (1 h, 37°C) in the dark. Islet cells were monitored under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 100; wavelength of excitation 480 nm, emitted fluorescence was filtered by a 515-nm long-pass filter). Nuclei were stained by Hoechst dye 33258 (excitation at 380 nm).

Statistics.

Each series of experiments was performed with islets or islet cells of at least three independent preparations. Means ± SEM are given for the indicated number of experiments. Statistical significance of differences was assessed by a Student t test for paired values. Multiple comparisons were made by ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test. The P values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

TCDC stimulates insulin secretion by activation of FXR.

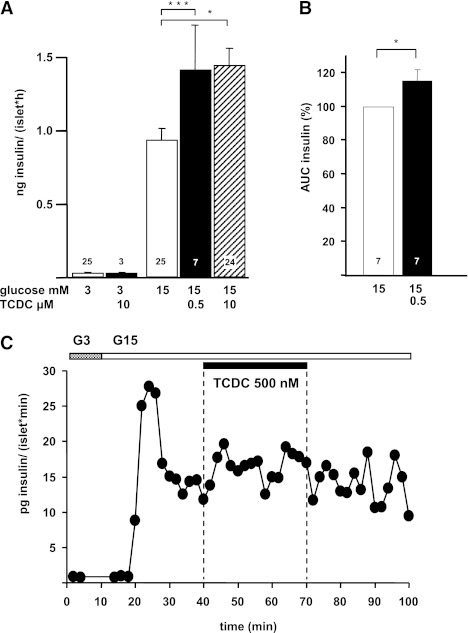

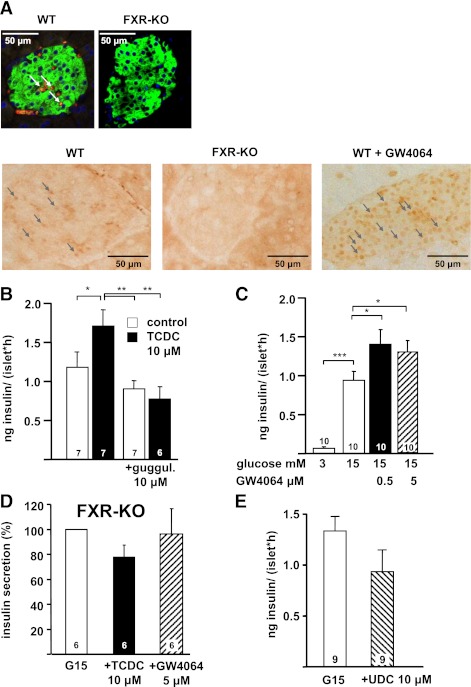

In mouse islets, 500 nmol/L and 10 μmol/L TCDC augmented insulin secretion induced by 15 mmol/L glucose (60 min, steady-state incubation) to the same extent (Fig. 1A). Likewise, islets perifused with 15 mmol/L glucose showed an increase in the second phase of insulin secretion in the presence of 500 nmol/L TCDC (Fig. 1B and C). A total of 50 nmol/L TCDC had no effect on insulin release (15 mmol/L glucose: 0.8 ± 0.1 ng/islet · h, + TCDC: 1.0 ± 0.2 ng/islet · h; n = 4). Because FXR is a target for specific BAs and expressed in pancreatic islets (Fig. 2A) (22,23), guggulsterone was used as a selective receptor antagonist (33). Guggulsterone alone did not alter insulin release but completely antagonized the effect of TCDC (Fig. 2B). In addition, the effect of TCDC was prevented in islets of FXR-KO mice (insulin release in 3 mmol/L glucose: 0.03 ± 0.01 ng/islet · h, stimulation by 15 mmol/L glucose: 4.9 ± 0.7 ng/islet · h, + TCDC: 3.5 ± 0.4 ng/islet · h; P not significant; n = 6) (Fig. 2D). To further evaluate the role of FXR, we used the specific FXR agonist GW4064 (34). This drug mimicked the effect of TCDC on glucose-induced insulin secretion and elevated insulin release to the same extent as TCDC in WT islets (compare Figs. 2C and 1A). Similar to TCDC, stimulation of insulin release by GW4064 does not show any concentration dependence. As expected, GW4064 had no effect in FXR-KO islets (Fig. 2D), ensuring that the drug is highly specific for FXR activation. Sodium ursodeoxycholic acid (UDC; 10 μmol/L) that has only a marginal affinity to FXR (35) did not augment insulin secretion (Fig. 2E). In summary, these data clearly point to an involvement of FXR in the action of TCDC on β-cell function.

FIG. 1.

Effects of TCDC on glucose-induced insulin secretion from mouse islets. A: Insulin release was measured in steady-state incubations (60 min). n is given within each bar. B: Islets were perifused with 3 mmol/L glucose for 10 min. White bars: Glucose-induced insulin release. Black and hatched bars: Insulin secretion in the presence of TCDC (glucose and TCDC concentrations as indicated). Thereafter, glucose was increased to 15 mmol/L. TCDC was added after 30-min glucose stimulation. C: Representative experiment with perifused islets. *P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.001.

FIG. 2.

FXR expression in pancreatic islets (A) and effects of FXR agonism and antagonism on insulin secretion (B–E) are shown. A (top): immunofluorescence staining of FXR protein. Green: insulin-positive islet cells; red: FXR-positive islet cells (colocalization of insulin and FXR is indicated by the arrows); blue: nuclear staining. Right: same protocol with a section of FXR-KO pancreas to exclude nonspecific binding of the FXR antibody. Bottom: DAB staining of FXR protein. Left: WT islets; arrows denote positive FXR staining; middle: FXR-KO islets, same protocol; right: WT islets after incubation with GW4064 for 2 h. Note that after incubation with GW4064, nuclear staining for FXR is markedly increased. Arrows exemplarily show FXR-positive areas. B: Suppression of the stimulatory effect of TCDC by addition of the FXR antagonist guggulsterone (guggul.) in the presence of 15 mmol/L glucose (control). White bars: Incubation without TCDC. Black bars: Incubation with TCDC. C: Effects of GW4064 (black and hatched bars) on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. D: Ineffectiveness of TCDC (black bar) and GW4064 (hatched bar) in glucose-stimulated islets of FXR-KO mice. Data obtained with islets from FXR-KO mice are expressed as percentage of secretion in 15 mmol/L glucose. E: UDC (hatched bar) does not increase glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (white bar). n is given within each bar. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

FXR activation increases [Ca2+]c.

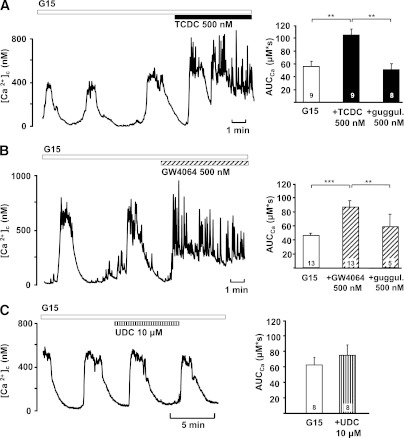

Because an increase in [Ca2+]c triggers insulin secretion, we evaluated the effect of TCDC on this parameter. Experiments were performed in single cells or small clusters of mouse β-cells. The potentiating effect of 500 nmol/L TCDC on glucose-induced Ca2+ oscillations is shown in Fig. 3A. Under these conditions, even 250 nmol/L TCDC altered [Ca2+]c. The area under the curve (AUC) increased from 58 ± 7 μmol/L · s to 89 ± 14 μmol/L · s (n = 9; P ≤ 0.05, not shown). With 1 μmol/L TCDC, the AUC was elevated from 66 ± 8 μmol/L · s to 96 ± 12 μmol/L · s (n = 6; P ≤ 0.05, not shown). GW4064 mimicked the action of TCDC on [Ca2+]c (Fig. 3B). The effects of both TCDC and GW4064 were antagonized by guggulsterone (Fig. 3A and B, right) that was applied for ∼10 min before the addition of TCDC and GW4064, respectively. Importantly, UDC had no effect on glucose-induced Ca2+ oscillations (AUC control: 57 ± 9 μmol/L · s, + 500 nmol/L UDC: 53 ± 10 μmol/L · s; n = 7; P not significant, not shown). Even at a concentration of 10 μmol/L, UDC did not significantly increase the AUC (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Effects of TCDC and GW4064 on [Ca2+]c. A: TCDC increased [Ca2+]c in the presence of 15 mmol/L glucose. To quantify the data, the AUC was calculated for a time interval of 300 s before and during addition of TCDC. Preincubation with guggulsterone blunted the stimulatory effect of TCDC (right). B: GW4064 had similar stimulatory effects on [Ca2+]c that were suppressed by guggulsterone (guggul., right). C: UDC did not alter the AUC in the presence of 15 mmol/L glucose. Representative experiments at left. The diagrams at right summarize the data and illustrate the AUC in the presence of 15 mmol/L glucose (G15, white bars), with TCDC or TCDC + guggulsterone (black bars in A), GW4064, or GW4064 + guggulsterone (hatched bars in B) or UDC (striped bar in C). n is given within each bar. **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

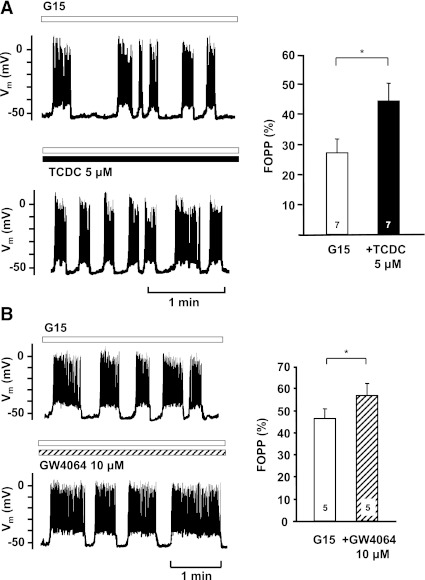

Electrical activity is enhanced by FXR activation.

In β-cells, membrane depolarization is the main trigger that increases [Ca2+]c. Therefore, we investigated whether TCDC influences electrical activity. In accordance with the effects on [Ca2+]c, membrane potential (Vm) was depolarized by TCDC. The fraction of plateau phase (FOPP; percentage of time with spike activity) increased (Fig. 4A). This change was due to an increase in the average length of burst phases (control: 10 ± 4 s; TCDC: 33 ± 22 s; n = 7; P not significant) and a decrease in the average length of interburst phases (control: 15 ± 4 s; TCDC: 12 ± 4 s; n = 7; P ≤ 0.05). GW4064 mimicked the effect of TCDC on the FOPP (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Effects of FXR activation on Vm. A and B: Effects of TCDC and GW4064 on the fraction of plateau-phase FOPP. FOPP was calculated at a time interval of 5 min before and during addition of the drugs. To obtain regular oscillations, these experiments were performed with 20 mmol/L Ca2+ in the bath solution. Left: typical experiment; bottom: continuation of the top trace. Right: summary of all experiments. The diagrams show evaluation of the FOPP in the presence of 15 mmol/L glucose (G15, white bars) and in the presence of G15 + TCDC (black bar in A) or G15 + GW4064 (hatched bar in B). n is given within each bar. *P ≤ 0.05.

TCDC influences β-cell function at threshold glucose concentrations.

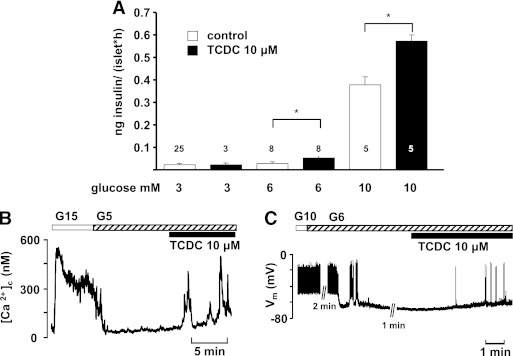

To elucidate whether TCDC also affects β-cell function at lower glucose concentrations, insulin release was determined in the presence of 3, 6, and 10 mmol/L glucose (Fig. 5A). TCDC had no effect in 3 mmol/L glucose. With 6 mmol/L glucose, 10 μmol/L TCDC increased insulin release in eight experiments (Fig. 5A). In five experiments, TCDC was ineffective (0.04 ± 0.01 vs. 0.03 ± 0.01 ng/[islet · h]). With 10 mmol/L glucose, insulin secretion was stimulated by TCDC in five of seven experiments. In agreement with these results, TCDC affected Vm and [Ca2+]c in the presence of a glucose concentration close to the threshold for stimulation of electrical activity (5 to 6 mmol/L). At these glucose concentrations, [Ca2+]c remains at basal levels, and Vm is close to the threshold potential for the opening of L-type Ca2+ channels. TCDC induced an increase in [Ca2+]c with oscillations in 7 of 11 experiments (Fig. 5B) and depolarized Vm above the threshold for action potentials in 8 of 13 cells tested (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Glucose-dependent effects of TCDC on insulin release. A: TCDC does not stimulate insulin release in 3 mmol/L glucose. Bars for 6 and 10 mmol/L glucose summarize those preparations that responded to TCDC with an increase in secretion. n is given within each bar. B and C: Stimulatory effect of TCDC at threshold glucose concentrations on [Ca2+]c and Vm, respectively. n is given in the text. *P ≤ 0.05.

FXR activation leads to closure of KATP channels and reduces the slowly developing K+ current.

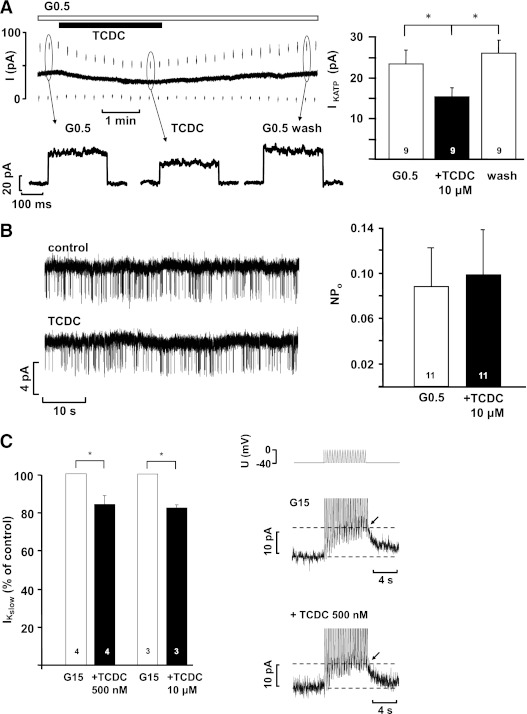

Closure of KATP channels is the key event that induces membrane depolarization. TCDC reduced the KATP whole-cell current measured in the perforated-patch configuration (Fig. 6A). A clear effect was reached within 2.4 ± 0.5 min after addition of the drug (n = 9). These experiments were performed in 0.5 mmol/L glucose, as with higher glucose concentrations, KATP current is too small to detect subtle changes. The inhibitory action of TCDC on KATP current was completely suppressed in cells pretreated with guggulsterone (control current in 0.5 mmol/L glucose: 45 ± 8 pA; 10 μmol/L guggulsterone: 45 ± 10 pA; guggulsterone plus 10 μmol/L TCDC: 42 ± 11 pA; n = 10; P not significant, not shown). In excised inside-out patches, TCDC did not alter the single-channel activity, calculated as NPo (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

A: KATP whole-cell current measured in the perforated-patch configuration in the presence of 0.5 mmol/L glucose and after addition of TCDC. The lower dashed line indicates zero current at −80 mV. At the marked time points, whole-cell currents are shown in higher resolution below the current trace. B: KATP single-channel activity registered in excised inside-out patches. Representative experiments at left. The diagrams at right summarize the data. n is given within each bar. C: Reduction of IKslow by TCDC. The pulse protocol used for these experiments is illustrated above the current traces. White bars: Control condition, glucose concentrations as indicated. Black bars: Respective glucose concentration + TCDC. In the current traces, the peak of IKslow is marked by the arrows. The diagram at left summarizes the data. n is given within each bar. *P ≤ 0.05.

For regulation of membrane potential oscillations, a slowly developing K+ current, termed IKslow, which is comprised of KATP and Ca2+-dependent K+ current, is very important (31). Therefore, we tested whether TCDC influences IKslow, which is activated in β-cells during Ca2+ action potential firing. Cells were stimulated by 15 mmol/L glucose, and a burst of Ca2+ action potentials was imitated by a pulse protocol. Compared with control, 10 μmol/L TCDC reduced IKslow to 82 ± 2% (15 mmol/L glucose: 5.3 ± 0.4 pA; plus TCDC: 4.3 ± 0.3 pA; n = 3; P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 6C). Similar results were obtained with 500 nmol/L TCDC that reduced IKslow to 84 ± 4% compared with control (n = 4; P ≤ 0.05).

Influence of BAs on Kv and transient receptor potential melastatin 3 channels.

Kv channels regulate action potential repolarization and can thereby affect Vm and, finally, insulin release. Effects of TCDC on Kv channels were investigated in the standard whole-cell configuration. 500 nmol/L TCDC did not alter Kv current (control: 452 ± 156 pA; plus TCDC: 443 ± 129 pA, n = 3, P not significant). With 10 μmol/L TCDC Kv current was reduced by ∼20% (control: 559 ± 101 pA, + TCDC 430 ± 94 pA; n = 6; P ≤ 0.001).

BAs share structural similarities with steroid hormones. In β-cells, the transient receptor potential melastatin 3 (TRPM3) subtype of transient receptor potential ion channels acts as steroid receptor for which activation increases [Ca2+]c (32). Therefore, we tested whether TRPM3 activity is altered by BAs. Changes in [Ca2+]c were measured in trpm3-transfected HEK293 cells. Even at a very high concentration of 50 μmol/L, TCDC did not activate TRPM3 channels (F340/F380 under control conditions: 0.28 ± 0.01; after addition of TCDC: 0.28 ± 0.01; n = 30; not shown).

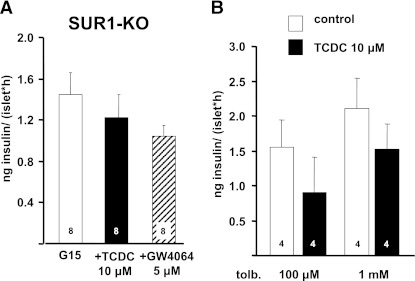

TCDC and GW4064 do not alter insulin secretion in islets of SUR1-KO mice or in islets treated with tolbutamide.

We have shown that TCDC stimulates FXR and inhibits KATP currents. This raises the question whether the rapid inhibition of KATP channels by TCDC is only an epiphenomenon or is linked to FXR activation. To further evaluate this point, we studied the effect of TCDC and GW4064 in SUR1-KO mice lacking functional KATP channels due to the knockout of the regulatory KATP channel subunit SUR1. Even high concentrations of the FXR activators inhibited rather than stimulated insulin secretion induced by 15 mmol/L glucose in SUR1-KO islets (Fig. 7A). This result clearly points to KATP channels as the major targets for stimulation of insulin release by FXR activators. Accordingly, there was no additional stimulation of glucose-induced insulin secretion in these islets by GW4064 (Fig. 7A). To confirm that KATP channel inhibition is the underlying mechanism for TCDC-mediated insulin release, KATP channels of WT islets were inhibited by the sulfonylurea tolbutamide. Similar to the experiments with SUR1-KO islets, 10 μmol/L TCDC did not stimulate insulin secretion in the presence of tolbutamide (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Insulin secretion from islets of SUR1-KO mice and tolbutamide (tolb.)-treated WT islets. A: TCDC and GW4064 did not augment glucose-induced secretion in islets from SUR1-KO mice. Islets were incubated in the presence of 15 mmol/L glucose (G15), with G15 + TCDC (black bar) or G15 + GW4064 (hatched bar). B: TCDC was without effect on insulin release in WT islets in the presence of the KATP channel blocker tolbutamide. n is given within each bar. Islets were incubated in the presence of 15 mmol/L glucose, the indicated concentration of tolbutamide (control, white bars) and tolbutamide + TCDC (black bars).

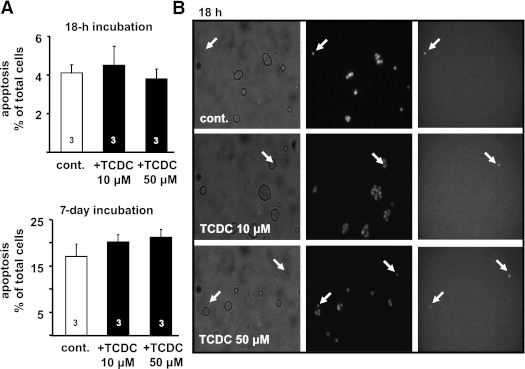

BAs do not induce apoptosis in islet cells.

The results suggest that TCDC may be an appropriate tool to improve glucose homeostasis. However, such a tool should not increase the rate of apoptosis as described for certain BAs (24). Islet cells were incubated for 18 h and 7 days in the presence of 10 and 50 μmol/L TCDC, respectively. The rate of apoptosis was determined by counting TUNEL-positive islet cells. Application of TCDC for 18 h was without effect (Fig. 8). After 7 days, the rate of apoptosis in untreated cells was approximately fourfold higher compared with 18 h, but even the high concentration of TCDC did not increase apoptosis when applied for 1 week.

FIG. 8.

Effect of TCDC on apoptosis. A: The bars summarize the results for TUNEL-positive cells without (cont., white bars) and with treatment with TCDC (black bars) for 18 h and 7 days in medium with 11.1 mmol/L glucose. B: Images of islet cells after 18-h incubation. Transmitted light (left); 380-nm excitation wavelength, nuclei staining with Hoechst dye 33258 (middle); and TUNEL-positive cells (right) are shown. Fluorescence images were obtained at 480-nm excitation wavelength. Arrows denote dead cells. n is given within each bar.

DISCUSSION

BAs exert multiple physiological effects by binding to membrane-associated or nuclear receptors. The action of BAs is not restricted to the liver. Because concentrations up to 15 μmol/L can be found in systemic blood after a meal (36), BAs can activate BA receptors expressed in other tissues including kidney, gall bladder, intestine, brain, heart, and pancreas (37). In our experiments, TCDC induced similar effects over a large concentration range (250 nmol/L to 10 μmol/L). This suggests that the influence of BAs on β-cell function is not restricted to maximal plasma concentrations. The rapid onset of the TCDC effects in β-cells (Fig. 3) suggests involvement of a membrane receptor rather than of a nuclear receptor. Recently, TRPM3 was found to act as a steroid receptor in β-cells (32). Application of the TRPM3 agonist Preg-S increases glucose-induced insulin secretion. Thus, it was obvious to test whether TRPM3 is stimulated by BAs. However, TCDC was without direct effect on TRPM3 channels. Our results clearly show that the TCDC effect is mediated by FXR. This conclusion is based on the facts that the effects of TCDC are mimicked by the FXR agonist GW4064 and antagonized by the FXR antagonist guggulsterone. The lack of effect of GW4064 on insulin secretion in FXR-KO islets proves that GW4064 is specific for FXR in β-cells and does not exert its effects at other targets. The finding that the TCDC action is completely suppressed in FXR-KO islets suggests that the stimulatory effect of TCDC on insulin secretion is solely mediated by FXR, thus excluding a major role for other BA receptors. For an effect mediated by a nuclear receptor, it is unexpected to observe such a rapid onset, as it was revealed by online measurements of [Ca2+]c, KATP whole-cell currents, and Kslow. However, estrogens can mediate rapid, nongenomic effects by binding to nuclear receptors, and the estrogen/estrogen receptor complex can translocate to the plasma membrane and interact with membrane proteins (reviewed in Ref. 38). 17-Beta-estradiol inhibits K+ currents from parabrachial nucleus cells, and this effect is significantly reduced by a selective estrogen antagonist (39). Our results suggest a similar mechanism for FXR that might directly or indirectly interact with KATP channels. The reduction of KATP current is only moderate. Consequently, the efficacy of the BA is most profound when KATP current is already low (i.e., at a high glucose concentration), and, in contrast to sulfonylureas, TCDC did not induce insulin secretion at 3 mmol/L glucose. Nevertheless, at glucose concentrations close to the threshold for opening of L-type Ca2+ channels, TCDC increased β-cell activity in the majority of experiments. The antagonism by guggulsterone in the online registrations of [Ca2+]c and KATP currents corroborates the idea that BAs exert acute, nongenomic effects on β-cell stimulus-secretion coupling via FXR. Other groups that have studied the effects of FXR activation in β-cells may have missed the rapid onset of the effects because they pretreated β-cells with FXR activators for several hours (18–48 h) before they evaluated the effects of FXR stimulation on insulin secretion (22,23).

The involvement of FXR in the TCDC-induced closure of KATP channels is documented by the fact that guggulsterone antagonizes the effect. Moreover, we can exclude a direct effect of TCDC on KATP channels because intact-cell metabolism is necessitated. As TCDC increased the FOPP one should expect that the BA affects IKslow, which is known to regulate oscillations of Vm (31). Indeed, TCDC reduced IKslow by ∼17%. In agreement with the lack of any concentration dependence of the BA with respect to [Ca2+]c or insulin release, 500 and 10 μmol/L TCDC had similar effects on IKslow. In addition to the KATP channel inhibition, 10 μmol/L TCDC reduced Kv currents under conditions without intact-cell metabolism pointing to a direct interaction between Kv channels and the BA at high concentrations. The disappearance of the stimulatory effect of TCDC in SUR1-KO islets and in tolbutamide-treated WT islets implies that KATP channel inhibition is not an epiphenomenon but occurs downstream to FXR activation and finally results in stimulation of insulin secretion.

Renga and coworkers (22) have proposed that nongenomic effects, besides genomic, contribute to enhanced insulin secretion after FXR activation. Their observations were explained by a nongenomic effect of FXR on Akt phosphorylation stimulating translocation of the glucose transporter Glut-2 to the plasma membrane. Increased glucose uptake is assumed to enhance insulin secretion. However, this interpretation is in conflict with the fact that intracellular glucose concentration in β-cells rapidly follows changes in blood glucose concentration (40). Glucose uptake seems not to be the rate-limiting step because the glucose transport capacity of the β-cell is 50–100 times higher than the capacity to phosphorylate glucose (41,42).

Our results show that FXR activation by TCDC has beneficial effects on β-cell function. These findings support suggestions of others who proposed FXR as a useful target to interfere with disturbances of glycemic control. Importantly, stimulation of insulin release by TCDC is glucose-dependent, which might avoid severe hypoglycemic excursions that complicate the therapeutic use of drugs directly acting on KATP channels. Treatment of obese and diabetic mice with tauroursodeoxycholic acid resulted in normalization of hyperglycemia, restoration of systemic insulin sensitivity, and enhancement of insulin action in liver, muscle, and adipose tissue (12). The positive effects were attributed to the reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Accordingly, obese humans treated with tauroursodeoxycholic acid showed improved insulin sensitivity of liver and muscle (43). Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (GB) surgery leads to weight loss and improved metabolism in patients with morbid obesity (44). Total serum concentrations of several BAs including TCDC were higher in GB than in both overweight and severely obese subjects, and total BAs were inversely correlated with 2-h postmeal plasma glucose concentration. The authors conclude that altered BA levels and composition may contribute to improved glucose and lipid metabolism in patients who have had GB. Of note, recent reports showed that permanent activation of FXR by GW4064 accelerates weight gain and reduces glycemic control in mice fed with a high-fat diet, whereas FXR-KO seems to be beneficial under these conditions (45,46). This contrasts with observations with genetic animal models for diabetes (16,17) in which treatment with GW4064 or certain BAs beneficially affects glucose homeostasis. Our data suggest that among others, changes in the BA pattern may improve the secretory capacity of β-cells and contribute to normoglycemia.

If one suggests BAs as pharmacological tools to treat glucose intolerance in patients at risk for diabetes, one has to consider that BAs can induce apoptosis (24). BAs can promote the generation of reactive oxygen species and induce the large conductance state of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (24) or may activate the inflammasome via reduction of K+ outflux (47), processes tightly linked to induction of apoptosis. In our experiments, TCDC did not alter the rate of apoptosis of islet cells even when applied for 7 days in a high concentration (50 μmol/L). Our data suggest that targeting FXR of pancreatic β-cells may constitute a pharmaceutical strategy for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (48).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to M.D. and G.D.) and Emmy Noether-programme (to J.O.).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

M.D. researched data and wrote the manuscript. K.H., R.W., B.S., S.P., T.F.J.W., and R.L. researched data. J.O. and P.K.-D. contributed to discussion and edited the manuscript. F.J.G. kindly provided the FXR-KO mice and edited the manuscript. G.D. wrote and edited the manuscript and contributed to discussion. G.D. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors thank Isolde Breuning, University of Tübingen, Institute of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacology, Tübingen, Germany, for skillful technical assistance.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db11-0815/-/DC1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fiorucci S, Mencarelli A, Palladino G, Cipriani S. Bile-acid-activated receptors: targeting TGR5 and farnesoid-X-receptor in lipid and glucose disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2009;30:570–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao X, Peter A, Fritsche J, et al. Changes of the plasma metabolome during an oral glucose tolerance test: is there more than glucose to look at? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2009;296:E384–E393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaham O, Wei R, Wang TJ, et al. Metabolic profiling of the human response to a glucose challenge reveals distinct axes of insulin sensitivity. Mol Syst Biol 2008;4:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, Staels B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev 2009;89:147–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glicksman C, Pournaras DJ, Wright M, et al. Postprandial plasma bile acid responses in normal weight and obese subjects. Ann Clin Biochem 2010;47:482–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Güliter S, Yilmaz S, Karakan T. Evaluation of gallbladder volume and motility in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients using real-time ultrasonography. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;37:288–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersén E, Karlaganis G, Sjövall J. Altered bile acid profiles in duodenal bile and urine in diabetic subjects. Eur J Clin Invest 1988;18:166–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennion LJ, Grundy SM. Effects of diabetes mellitus on cholesterol metabolism in man. N Engl J Med 1977;296:1365–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen A, Bouscarel B. Bile acids and signal transduction: role in glucose homeostasis. Cell Signal 2008;20:2180–2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staels B, Handelsman Y, Fonseca V. Bile acid sequestrants for lipid and glucose control. Curr Diab Rep 2010;10:70–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinton EA. Novel pathways for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: focus on bile acid modulation. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008;10:1004–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, et al. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science 2006;313:1137–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li LO, Hu YF, Wang L, Mitchell M, Berger A, Coleman RA. Early hepatic insulin resistance in mice: a metabolomics analysis. Mol Endocrinol 2010;24:657–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cariou B, van Harmelen K, Duran-Sandoval D, et al. The farnesoid X receptor modulates adiposity and peripheral insulin sensitivity in mice. J Biol Chem 2006;281:11039–11049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma K, Saha PK, Chan L, Moore DD. Farnesoid X receptor is essential for normal glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1102–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Lee FY, Barrera G, et al. Activation of the nuclear receptor FXR improves hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:1006–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cipriani S, Mencarelli A, Palladino G, Fiorucci S. FXR activation reverses insulin resistance and lipid abnormalities and protects against liver steatosis in Zucker (fa/fa) obese rats. J Lipid Res 2010;51:771–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duran-Sandoval D, Cariou B, Percevault F, et al. The farnesoid X receptor modulates hepatic carbohydrate metabolism during the fasting-refeeding transition. J Biol Chem 2005;280:29971–29979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Castellani LW, Sinal CJ, Gonzalez FJ, Edwards PA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha) regulates triglyceride metabolism by activation of the nuclear receptor FXR. Genes Dev 2004;18:157–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claudel T, Staels B, Kuipers F. The Farnesoid X receptor: a molecular link between bile acid and lipid and glucose metabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:2020–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duran-Sandoval D, Mautino G, Martin G, et al. Glucose regulates the expression of the farnesoid X receptor in liver. Diabetes 2004;53:890–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renga B, Mencarelli A, Vavassori P, Brancaleone V, Fiorucci S. The bile acid sensor FXR regulates insulin transcription and secretion. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1802:363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popescu IR, Helleboid-Chapman A, Lucas A, et al. The nuclear receptor FXR is expressed in pancreatic beta-cells and protects human islets from lipotoxicity. FEBS Lett 2010;584:2845–2851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez MJ, Briz O. Bile-acid-induced cell injury and protection. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:1677–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monte MJ, Marin JJ, Antelo A, Vazquez-Tato J. Bile acids: chemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:804–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu HB, Li L, Liu GQ. Protection against hydrogen peroxide-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells by guggulsterone. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2008;43:1190–1197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lv N, Song MY, Kim EK, Park JW, Kwon KB, Park BH. Guggulsterone, a plant sterol, inhibits NF-kappaB activation and protects pancreatic beta cells from cytokine toxicity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2008;289:49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gier B, Krippeit-Drews P, Sheiko T, et al. Suppression of KATP channel activity protects murine pancreatic beta cells against oxidative stress. J Clin Invest 2009;119:3246–3256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinal CJ, Tohkin M, Miyata M, Ward JM, Lambert G, Gonzalez FJ. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell 2000;102:731–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garrino MG, Plant TD, Henquin JC. Effects of putative activators of K+ channels in mouse pancreatic beta-cells. Br J Pharmacol 1989;98:957–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Düfer M, Gier B, Wolpers D, Krippeit-Drews P, Ruth P, Drews G. Enhanced glucose tolerance by SK4 channel inhibition in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 2009;58:1835–1843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner TF, Loch S, Lambert S, et al. Transient receptor potential M3 channels are ionotropic steroid receptors in pancreatic beta cells. Nat Cell Biol 2008;10:1421–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urizar NL, Liverman AB, Dodds DT, et al. A natural product that lowers cholesterol as an antagonist ligand for FXR. Science 2002;296:1703–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willson TM, Jones SA, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. Chemical genomics: functional analysis of orphan nuclear receptors in the regulation of bile acid metabolism. Med Res Rev 2001;21:513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lew JL, Zhao A, Yu J, et al. The farnesoid X receptor controls gene expression in a ligand- and promoter-selective fashion. J Biol Chem 2004;279:8856–8861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houten SM, Watanabe M, Auwerx J. Endocrine functions of bile acids. EMBO J 2006;25:1419–1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai SY, Xiong L, Wray CG, Ballatori N, Boyer JL. The farnesoid X receptor FXRalpha/NR1H4 acquired ligand specificity for bile salts late in vertebrate evolution. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007;293:R1400–R1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornil CA, Charlier TD. Rapid behavioural effects of oestrogens and fast regulation of their local synthesis by brain aromatase. J Neuroendocrinol 2010;22:664–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fatehi M, Kombian SB, Saleh TM. 17beta-estradiol inhibits outward potassium currents recorded in rat parabrachial nucleus cells in vitro. Neuroscience 2005;135:1075–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson JH, Newgard CB, Milburn JL, Lodish HF, Thorens B. The high Km glucose transporter of islets of Langerhans is functionally similar to the low affinity transporter of liver and has an identical primary sequence. J Biol Chem 1990;265:6548–6551 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heimberg H, De Vos A, Vandercammen A, Van Schaftingen E, Pipeleers D, Schuit F. Heterogeneity in glucose sensitivity among pancreatic beta-cells is correlated to differences in glucose phosphorylation rather than glucose transport. EMBO J 1993;12:2873–2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tal M, Liang Y, Najafi H, Lodish HF, Matschinsky FM. Expression and function of GLUT-1 and GLUT-2 glucose transporter isoforms in cells of cultured rat pancreatic islets. J Biol Chem 1992;267:17241–17247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kars M, Yang L, Gregor MF, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid may improve liver and muscle but not adipose tissue insulin sensitivity in obese men and women. Diabetes 2010;59:1899–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patti ME, Houten SM, Bianco AC, et al. Serum bile acids are higher in humans with prior gastric bypass: potential contribution to improved glucose and lipid metabolism. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1671–1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prawitt J, Abdelkarim M, Stroeve JH, et al. Farnesoid X receptor deficiency improves glucose homeostasis in mouse models of obesity. Diabetes 2011;60:1861–1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe M, Horai Y, Houten SM, et al. Lowering bile acid pool size with a synthetic FXR agonist induces obesity and diabetes through reduced energy expenditure. J Biol Chem 2011;286:26913–26920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science 2010;327:296–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, Edwards PA. FXR signaling in metabolic disease. FEBS Lett 2008;582:10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]