Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate whether objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep disturbances persist among older adults in assisted living facilities (ALFs) and to identify predictors of sleep disturbance in this setting.

Design

Prospective, observational cohort study

Setting and Participants

121 residents, aged ≥ 65 years, in 18 ALFs in the Los Angeles area

Measurements

Objective (actigraphy) and subjective (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) sleep measures were collected at baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-up. Predictors of baseline sleep disturbance tested in bivariate analyses and multiple regression models included demographics, Mini-Mental State Examination score, number of comorbidities, nighttime sedating medication use, functional status (Activities of Daily Living, ADL; Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, IADL), restless legs syndrome, and sleep apnea risk.

Results

Objective and subjective sleep measures were similar at baseline, 3- and 6-month follow-up (objective nighttime total sleep (hours) 6.3, 6.5, and 6.4; objective nighttime percent sleep 77.2, 77.7, and 78.3; and PSQI total score 8.0, 7.8, and 7.7, respectively). The mean baseline nighttime percent sleep decreased by 2% for each additional unit increase in baseline comorbid conditions (measured as number of conditions) and increased by 4.5% for each additional unit increase in baseline ADLs (measured as number of ADLs), in a multiple regression model.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep disturbances are persistent among ALF residents and are related to greater number of comorbidities and poorer functional status at baseline. Interventions are needed to improve sleep in this setting.

Keywords: sleep, assisted living facilities, long-term care

As our population ages, an increasing number of Americans will enter assisted living facilities (ALFs), which serve individuals who need help with performing activities of daily living and who are no longer able to live independently in their own homes. The National Center for Assisted Living reports that most ALF residents have functional limitations and need assistance, for example, with medication administration and personal care.(1) Chronic conditions are also common among ALF residents – 33% have coronary heart disease, 30% have depression, and 38% have dementia.(1)

Although more than 500,000 Americans currently reside in an ALF (2), few studies have focused on sleep problems in this setting.(3) (4) (5) Prior research has demonstrated that sleep disturbances are pervasive and persistent among older adults residing in nursing homes, which differ from ALFs because they service more impaired residents and typically provide a higher level of care than ALFs. Previously, we reported that sleep disturbance is a common finding in older ALF residents and that poor sleep predicts declining functional status, worse quality of life, and greater depression over a six-month follow-up period.(5) We did not, however, examine whether sleep problems persisted over time among ALF residents. Although prior work suggests that sleep disturbance is persistent among older adults living independently at home (6), similar longitudinal sleep data have not been available for older adults living in ALFs. In addition, little is known about the potential predictors of sleep disturbance in ALFs.(7) Establishing whether sleep disturbances are persistent and identifying predictors of sleep disturbances are key steps to improving the sleep quality and sleep patterns of ALF residents.

A biopsychosocial framework of sleep disorders in late life developed by Reynolds and colleagues (8) synthesizes and broadly summarizes findings from existing studies to form a unifying framework for describing the challenges to sleep and circadian time-keeping across the life cycle (particularly later in life). Under this framework, negative changes in medical, physical (including cognitive impairment), functional burden, and life events lead to “decay” in sleep and sleep quality, a relationship that is also largely mediated by worsening mood and sleep-disordered breathing. This framework also states that characteristics such as gender, regular social interaction, and social support can attenuate this “decay.” Sleep disturbances, in turn, are also posited to affect physical and psychological adaptation to aging (i.e., sleep disturbances may, in turn, affect the very same factors that lead to sleep disturbances). We used this framework to guide hypothesis development for the current study.

OBJECTIVE

In this paper, we analyze data from a prospective, observational cohort study of older adults residing in Los Angeles-area ALFs. Our first objective was to determine whether objectively-and subjectively-measured sleep disturbances change over a six-month period. Since most sleep disturbance is chronic among older adults (6), we hypothesized that compared with baseline, mean objective and subjective measures of sleep disturbance would not be statistically different at three and six-month follow-up.

Our second objective was to identify predictors of objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep disturbances. Based on findings from other settings and the theoretical framework described above (8), we hypothesized (a priori) that worse medical/physical status (i.e., more comorbidity (9–13), worse cognition (14) (15), use of sedative/hypnotics (16)), greater functional burden (i.e., independence in fewer basic and instrumental activities of daily living (10,17,18)), depression (19–21), presence of primary sleep disorders (i.e., sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome), and other patient characteristics (i.e., advanced age, female gender (11), and non-white race/Hispanic ethnicity (22)) would predict worse objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep disturbance at baseline among ALF residents.

METHODS

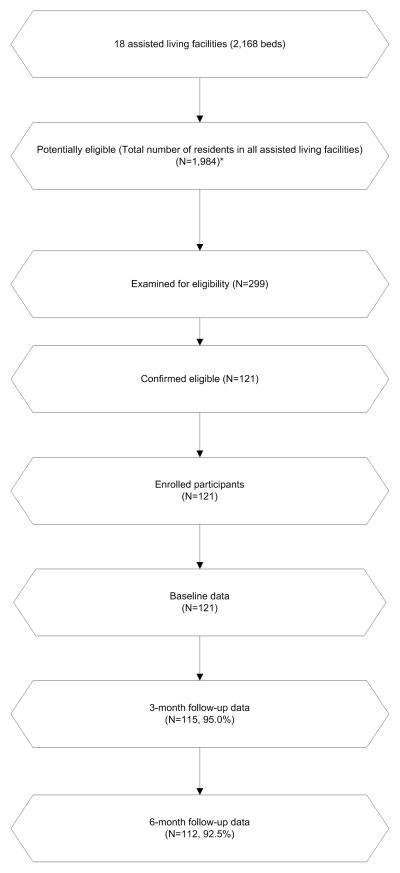

This was a prospective, observational cohort study among older people residing in 18 ALFs in Los Angeles County, California, recruited between April 2006 and March 2008 (see figure). The study methods have been reported in detail previously (5) and are summarized here. All but one facility was proprietary, and bed size ranged from 60–239. Although communal meal times may have been preset, residents, in general, had control over sleep schedules, including bedtime and wake up time.

Figure.

Participant Flow Chart

*Missing data for total number of residents at 6 facilities was imputed with the facility’s bedsize. Recruitment dates: 4/2006 to 3/2008. Follow-up dates: 7/2006 to 9/2008. Data collection dates: 4/2006 to 9/2008

The target sample size was 120 participants, which was calculated a priori based on the number of potential predictors we expected in our pre-specified multiple regression models.(23) Residents were invited to participate in the study following a 30-minute presentation about sleep research during which the principal investigator (CAA) described the study. Inclusion criteria for participants included age ≥ 65 years. Exclusion criteria included inability to communicate with research staff (due to aphasia or non-English-speaking) or inability of the participant to provide written informed consent (i.e., proxy consent was not pursued). The Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Institutional Review Board approved the project. No facilities were administered by the Veterans Administration. Trained research personnel performed all data collection. Data were collected at baseline and at three- and six-month follow-up, in person at the ALF where the participant resided.

Measures

Outcome Variables

Wrist actigraphy was used as an objective measure of sleep quality. Participants wore a wrist actigraph (Octagonal Sleep Watch-L, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc, (AMI) Ardsley, NY) on their dominant arm (except in cases of paralysis or other barriers to use of the dominant arm) for three consecutive days and nights. Research staff visually inspected the raw actigraphy data (one minute epoch) to identify technical and situational artifacts prior to scoring sleep. Sleep was scored using Action4 software (AMI), with default settings for automatic scoring of the Time Above Threshold channel. To facilitate actigraphy scoring, we employed a simple sleep diary we have used in prior research involving frail older adults.(24) Participants provided self-reported daily bedtime and rise times, which were used to determine nighttime and daytime periods for scoring and analysis of actigraphy data. We defined nighttime as the period between reported bedtime and rise time for each recorded night. We then computed the average nighttime total sleep time (TST) and nighttime percent sleep (hours asleep/nighttime period) over the three days of recording.(25) Prior studies have found strong correlations between actigraphy and polysomnography for TST (0.72 to 0.98) and nighttime percent sleep (0.82 to 0.96), whereas correlations are weaker for measures such as wake after sleep onset (0.49 to 0.87).(25)

Subjective sleep quality was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (26), an18-item questionnaire which queries about sleep over the past month (total possible score 0–21; scores > 5 suggest significant sleep disturbance).

Predictor Variables

We collected demographic data (age, gender, and ethnicity) for each participant. We used a Charlson comorbidity index-derived, self-report questionnaire (16 items; score range 0 [no comorbidity] to 32 [high comorbidity]) to assess comorbidity.(27) (28). Trained research staff recorded medication information through face-to-face interactions with participants that involved reviewing the participants’ actual pill bottles and asking participants when and if they took each medication each day over the actigraphy recording period. A composite dichotomous variable that indicated the use of nighttime sedating medications (benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, sedating antipsychotics, sedating antidepressants, and sedating antihistamines taken at night) was developed (any use versus non-use of nighttime sedating medication during the recording period).

The Mini-Mental State Examination (29) (MMSE; score range 0 to 30, score < 24 suggests cognitive impairment) provided a measure of cognitive functioning. Depression was assessed using the five-item Geriatrics Depression Scale (GDS-5; score range 0 to 5; scores ≥ 2 suggest depression).(30) We measured functional status using the self-reported Personal Self-Maintenance scale (activities of daily living [ADL] score range 0 to 7; instrumental activities of daily living [IADL] score range 0 to 8; higher numbers on both scales indicate better functional status).(31) We used the Berlin Sleep Apnea Questionnaire to estimate risk of sleep apnea (range 0 to 3, score ≥ 2 suggests high risk).(32) The Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) symptom questionnaire was used to estimate presence or absence of RLS (range 0 to 4, score = 4 suggests RLS).(33)

Procedures

Actigraphy and PSQI data and other measures described above were collected at baseline after enrollment, and participants were contacted at the ALF for follow-up three and six months from the date of enrollment. As described in our prior work (5), we collected baseline data for 121 participants. At three-month follow-up, two participants could not be reached, two participants were too ill to complete the assessments, one participant withdrew from the study, and one participant had died. At six-month follow-up, two participants refused to complete the assessment, three participants withdrew from the study, and four participants had died. Data collectors were blinded to study hypotheses, and the actigraphy scorer was blinded to other assessment data.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and Stata/SE 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). To determine whether objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep changed from baseline to three- and six-month follow-up, we calculated the change in each measure from baseline to three-month follow-up and from baseline to six-month follow-up, and formally tested for differences in these sleep measures between baseline and three- and six-month follow-up using paired t-tests. Our set of predictors for our bivariate analyses and multiple regression models predicting objective nighttime percent sleep and objective nighttime TST was based on our conceptual framework, clinical experience, and prior studies and included age, gender, ethnicity, comorbidity index, use of nighttime sedating medications, ADL and IADL scale scores, MMSE score, presence of RLS, sleep apnea risk, and GDS-5. The predictors for our bivariate analyses and multiple regression model predicting PSQI total score were the same as the aforementioned predictors, except that the variable, use of sedating medications, was excluded because the PSQI contains an item that pertains to the use of sleeping medications.

Due to the nesting of participants within a facility, it was possible that the observations for each outcome were more correlated within facilities than between facilities. To assess this, we calculated the intraclass correlation (ICC) for each outcome. Because the ICCs were substantially greater than zero for PSQI total score (one-way ANOVA F(dfbetween 17, dfwithin 103)=1.32, p=.20, ICC=.05) and nighttime TST (one-way ANOVA F(dfbetween 17, dfwithin 102)=1.07, p=.40, ICC=.06), we used clustered robust standard errors for analyses involving these outcomes. For nighttime percent sleep, the ICC was zero (one-way ANOVA F(dfbetween 17, dfwithin 102)=0.57, p=0.91, ICC=0.00), so we used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses for this outcome. To assess the possibility of multicollinearity, tolerance diagnostics were computed for each model. All tolerances were within acceptable limits (i.e., all VIF values were lower than 2), indicating no multicollinearity.

Because of the large number of pairwise comparisons that were performed (comparisons between 11 predictor variables and 3 outcome variables), Sidak adjusted p-values, in addition to unadjusted p-values, were generated for the bivariate analyses to minimize Type 1 error. For all statistical testing, we used two-tailed tests, with an alpha level of 0.05. No imputations were made for missing data, except in the case of the number of potentially eligible participants (i.e., number of residents living in the facility at the time of recruitment), which is shown in the figure. For this variable, we imputed the missing values of 6 facilities with each facility’s bedsize, which would have been the maximum number of potentially eligible participants at the facility if the facility had had 100% occupancy.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The mean age of the sample (n=121) was 85.3 years (SD 6.5). A majority of the participants was female (n=87, 86%) and of non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity (n=106, 88%). The average number of years of residence in the ALF was 2.6 years (SD 2.9). Most participants reported low comorbidity index scores (mean = 1.4, SD 1.6). The mean MMSE score was 26.4 (SD 3.1). The mean GDS-5 score was 1.1 (SD 1.2), and 30% of the sample had GDS-5 scores suggestive of depression. Most participants had mild to moderate functional impairment (mean ADLs = 6.3 (SD 0.7) and mean IADLs = 5.3 (SD 1.5)). Average time between baseline and final follow-up visit was 223 days (SD 45.3).

Approximately one-third of the sample used a nighttime sedating medication (n=39, 33.6%) at baseline, and 39 (32.5%) participants were high-risk for sleep apnea based on the Berlin Sleep Apnea Questionnaire. Fourteen participants (11.6%) reported symptoms suggestive of RLS. Complete data were available for all of the above variables except years of residence in the ALF (n=118), MMSE (n=120), sedating medications (n=126), and Berlin Sleep Apnea score (n=120).

Sleep Quality and Patterns

Persistence of objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep disturbances

TST, nighttime percent sleep, and PSQI total score at baseline, three-month follow-up, and six-month follow-up are summarized in Table 1. Paired t-tests demonstrated no statistically significant differences in any of these sleep measures between baseline and three- and six-month follow-up.

Table 1.

Objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep among ALF residents at baseline, 3- and 6-month follow-up (n=121)

| Baseline | 3-month follow-up | 6-month follow-up | Difference from baseline to 3-month follow-up | Difference from baseline to 6-month follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Objective Sleep Measures (Wrist actigraphy*) | |||||

| Nighttime total sleep time (hours) | 6.3 (1.6) | 6.5 (1.6) | 6.4 (1.8) | 0.1 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.1) |

| Missing | 2 (1.6%) | 16 (13.2%) | 22 (18.2%) | 16 (13.2%) | 22 (18.2%) |

| Nighttime percent sleep (hours asleep / hours from bedtime to rise time) | 77.2 (17) | 77.7 (15.6) | 78.3 (17.2) | −0.5 (10.2) | −0.4 (12.1) |

| Missing | 2 (1.6%) | 16 (13.2%) | 22 (18.2%) | 16 (13.2%) | 22 (18.2%) |

| Subjective Sleep Measure (Self-reported questionnaire) | |||||

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index total score (range=0–21) | 8.0 (4.3) | 7.8 (3.9) | 7.7 (3.9) | −0.2 (3.1) | −0.1 (3.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.8%) | 11 (9.1%) | 16 (13.2%) | 11 (9.1%) | 16 (13.2%) |

Nighttime defined as the interval from reported bedtime to reported rise time.

Bivariate relationships between objective and subjective sleep at baseline and participant characteristics

Bivariate testing showed no statistically significant relationships (using Sidak-corrected p-values for multiple comparisons) between objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep disturbances and participant characteristics (see Table 2, which shows correlations and t-tests between nighttime percent sleep and continuous and categorical patient characteristic variables, respectively, in addition to unadjusted and Sidak adjusted p-value). There also were no statistically significant relationships between objectively-measured sleep variables and PSQI total score.

Table 2.

Bivariable Relationships Between Demographic, Medical, Psychiatric, and Functional Status and Nighttime Percent Sleep

| Variable | Unadjusted p-value | Sidak- adjusted p- value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables: | r(n) | ||

| Age | −0.10 (120) | 0.292 | 1.000 |

| ADLs | 0.27 (120) | 0.003 | 0.167 |

| IADLs | 0.29 (120) | 0.001 | 0.081 |

| MMSE score | 0.19 (119) | 0.041 | 0.936 |

| GDS-5 | −0.09 (120) | 0.314 | 1.000 |

| Comorbidities | −0.17 (120) | 0.068 | 0.990 |

| Categorical variables: | t(df) | ||

| Female | −1.23 (118) | 0.221 | 0.893 |

| Non-Hispanic white | −0.97 (118) | 0.333 | 0.959 |

| Berlin score | −0.14 (117) | 0.892 | 1.000 |

| RLS score | 0.77 (118) | 0.445 | 0.982 |

| Use of nighttime sedating medication(s) | −1.00 (113) | 0.321 | 1.000 |

ADLs=Activities of daily living; IADLs=Instrumental activities of daily living; MMSE=Mini-Mental State Exam; GDS-5=Geriatric Depression Scale-5 item; RLS=Restless legs syndrome

Multiple regression models predicting objective and subjective sleep at baseline: Testing of Reynolds’ conceptual framework

In a multiple regression model, comorbidity and ADL score were significant independent predictors of nighttime percent sleep (see Table 3). In this model, the mean nighttime percent sleep at baseline decreased by 2% for each additional unit increase in baseline number of comorbid conditions (t(101) = −2.01, p=.048), and the mean nighttime sleep percent at baseline increased 4.5% for each additional unit increase (i.e., better) in baseline ADLs (t(101) = 2.05, p=.043) (See Table 3). In the other multiple regression models predicting PSQI total score and nighttime TST, none of the variables tested were statistically significant predictors (PSQI total score overall model F(10,17)=1.99, p=0.10; nighttime TST (overall model F(11,17) =1.50, p=0.22; not shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Results from Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Multiple Regression Model Relating Demographic, Medical, Psychiatric, and Functional Status with Nighttime Percent Sleep*

| Variable | B | Standard Error | t† | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.40 | 0.25 | −1.63 | 0.105 |

| Female | 2.05 | 3.53 | 0.58 | 0.563 |

| Non-Hispanic white | −1.79 | 5.36 | −0.33 | 0.739 |

| Comorbidities | −1.99 | 0.99 | −2.01 | 0.048 |

| Berlin score | −0.35 | 3.37 | −0.10 | 0.917 |

| RLS score | −4.24 | 4.92 | −0.86 | 0.390 |

| ADLs | 4.45 | 2.17 | 2.05 | 0.043 |

| IADLs | 2.26 | 1.17 | 1.92 | 0.057 |

| MMSE score | 0.64 | 0.60 | 1.08 | 0.283 |

| GDS-5 | 0.25 | 1.36 | 0.18 | 0.854 |

| Use of nighttime sedating medication(s) | 4.32 | 3.54 | 1.22 | 0.225 |

R-Squared 0.21, overall F test, F (11, 101)=2.50, p=.008

Significance evaluated with t-tests for each regression coefficient comparing it to 0 (df=101) RLS=Restless legs syndrome; ADLs=Activities of daily living; IADLs=Instrumental activities of daily living; MMSE=Mini-Mental State Exam; GDS-5=Geriatric Depression Scale-5 item

CONCLUSIONS

This study of sleep disturbance patterns and predictors of sleep disturbance among residents of ALFs in the Los Angeles area is the first study to characterize the persistence of sleep disturbances among this group of older adults and is one of the few studies to characterize predictors of sleep disturbances in this setting. We found that ALF residents had objectively-and subjectively-measured sleep disturbances that did not change significantly from baseline to three- and six-month follow-up. This finding is consistent with a prospective epidemiological study of older home-dwelling individuals, whose authors reported sleep disturbances that were less severe than we found in this ALF sample, but showed persistence of sleep disturbance at two-year follow-up.(6)

We also identified two important predictors of objectively-measured sleep disturbance in this population. As predicted by Reynolds’ conceptual framework(8), more medical burden (which we measured as number of comorbidities), was a significant predictor of worse objective nighttime percent sleep. This result is consistent with findings from a nation-wide study of community-dwelling adults, which found that nearly one in four older adults self-reported major comorbidity and that medical conditions such as heart disease were associated with more prevalent insomnia symptoms.(9) Similarly, another study found that hospitalized elderly patients with sleep problems scored significantly worse on the cumulative index rating scale severity index.(10) Another study that focused on insomnia in community-dwelling older adults found that more self-reported chronic medical conditions at baseline increased risk of new onset insomnia.(11) Conversely, in our model of PSQI total score, none of the predictors that were statistically significant in our model of objectively-measured nighttime percent sleep, including number of comorbidities, were found to be statistically significant. This finding contrasts with a prior study of nursing home residents, which identified more comorbidity as a predictor of worse PSQI scores.(34) Our finding that number of comorbidities was a predictor of objectively-measured sleep disturbance, but not subjectively-measured sleep disturbance is not surprising, given published reports showing inconsistent relationships between objective and subjective measures of sleep disturbances across age ranges and among older adults specifically (35) (36), which was demonstrated in our finding of no statistically significant correlation between objective and subjective measures of sleep disturbance in this study specifically.

The conceptual framework proposed by Reynolds and colleagues (8) also suggests that physical functional limitations would predict more sleep disturbance. We found that patients who were independent in fewer ADLs had worse objective nighttime percent sleep. One explanation is that participants who had more functional impairment may have had less daytime activity and less outdoor bright light exposure, which could have lead to impaired sleep patterns over time. These findings are consistent with studies of hospitalized elderly patients, which showed that sleep problems were significantly associated with worse functional status (ADLs).(10) Similarly, a study of older adults (one group from a memory clinic and another group from a longitudinal study of healthy aging) found that greater sleep disturbance correlated with more functional impairment.(17) A study of insomnia among community-dwelling older adults found that physical disability was associated with increased incidence of insomnia among individuals with medical conditions.(18)

Several other variables (e.g., cognitive functioning, sleep apnea risk, and depression) were not significant predictors of sleep disturbance in our analyses. Nursing home studies have identified worse MMSE as a predictor of sleep disturbance.(14) (15) One explanation for our negative finding may be that sleep disturbances typically worsen as dementia becomes more severe; our sample excluded enrollment of individuals with significant cognitive impairment who were unable to provide informed consent. Another explanation is that ALF residents may be more similar to community-dwelling elders than nursing home residents. For example, in a sample of community-dwelling adults recruited from a memory clinic, researchers found no significant difference in MMSE between patients with reported sleep disturbance and those without.(37) A prior study of insomnia among ALF residents found that residents with insomnia had better cognition than residents without insomnia, although the same study found that residents with daytime sleepiness had worse cognition.(3)

We also found that Berlin Sleep Apnea questionnaire score did not predict sleep disturbance in any of our multiple regression models. Lack of polysomnography may have limited our ability to identify sleep-disordered breathing, which we expected to be prevalent in the ALF setting based on the age group and the health status of the participants. We were surprised to find that depression was not a significant predictor in our multiple regression models. The lack of a statistically significant relationship between sleep disturbance and depression in our sample may be due to our sample selection methods (i.e., more severely depressed individuals may not have volunteered to participate). Studies of community-dwelling older adults have identified depression to be associated with worse PSQI scores.(19) (20) We did not find that participant demographics (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity) were significant predictors of sleep disturbance. However, we did not have information on social support or stability of social rhythms (19), which may be more important in this setting than demographics per se. Finally, we found that nighttime sedating medication use was not a predictor of sleep disturbance. This finding is consistent with two previous studies of individuals in other settings, including nursing home residents.(38) (39)

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep disturbance over time in ALF residents. This study shows that in the absence of an intervention to improve sleep, sleep disturbances persist in this setting. Documenting sleep patterns in this group of older adults from multiple ALF facilities is one of the first steps towards developing interventions to improve sleep in the ALF setting. This study is also the first to identify predictors of objectively-measured sleep disturbance in the ALF. Only with better understanding of the factors that contribute to poor sleep can we begin to provide assistance to these individuals.

The limitations of this study, which also limit generalizability of findings, include the relatively limited follow-up period and small number of participants at each study facility. In addition, while we adjusted for Type 1 errors in our analysis, this adjustment may increase the risk of Type II errors. This is particularly true, due to the small number of facilities (n=18), in the case of regression models that used clustered robust standard errors. Hierarchical and structural equation modeling (path analysis) were considered, but were not possible due to the nature of our sampling and modest sample size for such an approach. Our sample had few participants with symptoms of RLS, which may have limited our ability to detect this condition as a predictor of sleep disturbance. An additional caveat is that we used a self-report measure of comorbidity, which may have underestimated the true number of comorbid conditions. Unfortunately, detailed medical record data were not available, and a more comprehensive medical evaluation was not feasible due to funding limitations and increased participant burden.

In conclusion, we found that objectively- and subjectively-measured sleep disturbances are common, persistent and stable among ALF residents followed over a six-month period. We also identified two important predictors of sleep disturbances, including greater number of medical comorbidities and worse functional status. These findings suggest that interventions are needed to improve sleep among ALF residents, particularly among those who are most medically complex and require the most assistance.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the VA Advanced Geriatrics Fellowship Program; NIH NIA K23 AG028452, NIMH T32 MH 019925–11; UCLA Academic Senate Council on Research; VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center; VA Health Services Research and Development (IIR 04-321-2); and UCLA Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology. Additional financial support was provided by Sepracor Inc., Marlborough, MA. The authors thank the study project coordinators, Terry Vandenberg, MA and Rebecca Saia, the research staff, the staff at the participating facilities, and the ALF residents.

Sponsor's Role: The study sponsors had no input in the design, implementation, analysis or interpretation of this study.

Footnotes

Author's Contributions: Dr. Fung contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript. Dr. Martin and Ms. Josephson contributed to the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Mitchell contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Fiorentino and Ms. Jouldjian contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Chung contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. Dr. Alessi contributed to the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: Additional funding for this project was provided to Dr. Alessi from Sepracor Inc., Marlborough, MA. The authors have no other potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Osborne S. National trends and legislation in assisted living plus ethical marketing. National Center for Assisted Living; Apr, 2010. [Accessed August 1, 2011]. Available at: http://signup.oahcp.org/handouts/ALAdmNatlTrendsShaneOsborne.ppt. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawes C, Phillps CD, Rose M. [Accessed August 4, 2011];High service or high privacy assisted living facilities, their residents and staff: Results from a national survey. 2000 Jan; Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/hshp.htm.

- 3.Rao V, Spiro JR, Samus QM, et al. Sleep disturbances in the elderly residing in assisted living: findings from the Maryland Assisted Living Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20 (10):956–966. doi: 10.1002/gps.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JL, Alam T, Harker JO, et al. Sleep in assisted living facility residents versus home-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63 (12):1407–1409. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.12.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin JL, Fiorentino L, Jouldjian S, et al. Sleep quality in residents of assisted living facilities: effect on quality of life, functional status, and depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58 (5):829–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganguli M, Reynolds CF, Gilby JE. Prevalence and persistence of sleep complaints in a rural older community sample: the MoVIES project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44 (7):778–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.St George RJ, Delbaere K, Williams P, et al. Sleep quality and falls in older people living in self- and assisted-care villages. Gerontology. 2009;55 (2):162–168. doi: 10.1159/000146786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds CF, Dew MA, Monk TH, et al. Sleep disorders in late life: a biopsychosocial model for understanding pathogenesis and intervention. In: Cummings J, Coffey CE, editors. Textbook of geriatric neuropsychiatry. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. pp. 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, et al. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56 (5):497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaia G, Corsinovi L, Bo M, et al. Insomnia among hospitalized elderly patients: prevalence, clinical characteristics and risk factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52 (2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gureje O, Oladeji BD, Abiona T, et al. The natural history of insomnia in the Ibadan study of ageing. Sleep. 2011;34 (7):965–973. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ancoli-Israel S, Ayalon L. Diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14 (2):95–103. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000196627.12010.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaussent I, Dauvilliers Y, Ancelin ML, et al. Insomnia symptoms in older adults: associated factors and gender differences. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19 (1):88–97. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181e049b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fetveit A, Bjorvatn B. Sleep duration during the 24-hour day is associated with the severity of dementia in nursing home patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21 (10):945–950. doi: 10.1002/gps.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki R, Meguro M, Meguro K. Sleep disturbance is associated with decreased daily activity and impaired nocturnal reduction of blood pressure in dementia patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53 (3):323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seppala M, Rajala T, Sourander L. Subjective evaluation of sleep and the use of hypnotics in nursing homes. Aging (Milano ) 1993;5 (3):199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF03324155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tractenberg RE, Singer CM, Kaye JA. Symptoms of sleep disturbance in persons with Alzheimer's disease and normal elderly. J Sleep Res. 2005;14 (2):177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foley DJ, Monjan A, Simonsick EM, et al. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults: an epidemiologic study of 6,800 persons over three years. Sleep. 1999;22 (Suppl 2):S366–S372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao KW, Yu S, Cheng SP, et al. Relationships between personal, depression and social network factors and sleep quality in community-dwelling older adults. J Nurs Res. 2008;16 (2):131–139. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000387298.37419.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motivala SJ, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, et al. Impairments in health functioning and sleep quality in older adults with a history of depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54 (8):1184–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foley DJ, Vitiello MV, Bliwise DL, et al. Frequent napping is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, pain, and nocturia in older adults: findings from the National Sleep Foundation '2003 Sleep in America' Poll. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15 (4):344–350. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000249385.50101.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiter ME, Decoster J, Jacobs L, et al. Normal sleep in African-Americans and Caucasian-Americans: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2011;12 (3):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Matchar DB, et al. Regression models for prognostic prediction: advantages, problems, and suggested solutions. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69 (10):1071–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alessi CA, Martin JL, Webber AP, et al. More daytime sleeping predicts less functional recovery among older people undergoing inpatient post-acute rehabilitation. Sleep. 2008;31 (9):1291–1300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tryon WW. Issues of validity in actigraphic sleep assessment. Sleep. 2004;27 (1):158–165. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CFI, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, et al. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34 (1):73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D. Use of a self-repot-generated Charlson comorbidity index for predicting mortality. Med Care. 2005;43 (6):607–615. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163658.65008.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoyl MT, Alessi CA, Harker JO, et al. Development and testing of a five-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47 (7):873–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9 (3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, et al. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131 (7):485–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4 (2):101–119. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gentili A, Weiner DK, Kuchibhatil M, et al. Factors that disturb sleep in nursing home residents. Aging (Milano ) 1997;9 (3):207–213. doi: 10.1007/BF03340151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCrae CS, Rowe MA, Tierney CG, et al. Sleep complaints, subjective and objective sleep patterns, health, psychological adjustment, and daytime functioning in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60 (4):182–189. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.p182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gooneratne NS, Bellamy SL, Pack F, et al. Case-control study of subjective and objective differences in sleep patterns in older adults with insomnia symptoms. J Sleep Res. 2011;20 (3):434–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moran M, Lynch CA, Walsh C, et al. Sleep disturbance in mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Sleep Med. 2005;6 (4):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monane M, Glynn RJ, Avorn J. The impact of sedative-hypnotic use on sleep symptoms in elderly nursing home residents. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;59 (1):83–92. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Englert S, Linden M. Differences in self-reported sleep complaints in elderly persons living in the community who do or do not take sleep medication. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 (3):137–144. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]