Abstract

Renal microvascular (MV) damage and loss contribute to the progression of renal injury in renovascular disease (RVD). Whether a targeted intervention in renal microcirculation could reverse renal damage is unknown. We hypothesized that intrarenal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy will reverse renal dysfunction and decrease renal injury in experimental RVD. Unilateral renal artery stenosis (RAS) was induced in 14 pigs, as a surrogate of chronic RVD. Six weeks later, renal blood flow (RBF) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) were quantified in vivo in the stenotic kidney using multidetector computed tomography (CT). Then, intrarenal rhVEGF-165 or vehicle was randomly administered into the stenotic kidneys (n = 7/group), they were observed for 4 additional wk, in vivo studies were repeated, and then renal MV density was quantified by 3D micro-CT, and expression of angiogenic factors and fibrosis was determined. RBF and GFR, MV density, and renal expression of VEGF and downstream mediators such as p-ERK 1/2, Akt, and eNOS were significantly reduced after 6 and at 10 wk of untreated RAS compared with normal controls. Remarkably, administration of VEGF at 6 wk normalized RBF (from 393.6 ± 50.3 to 607.0 ± 45.33 ml/min, P < 0.05 vs. RAS) and GFR (from 43.4 ± 3.4 to 66.6 ± 10.3 ml/min, P < 0.05 vs. RAS) at 10 wk, accompanied by increased angiogenic signaling, augmented renal MV density, and attenuated renal scarring. This study shows promising therapeutic effects of a targeted renal intervention, using an established clinically relevant large-animal model of chronic RAS. It also implies that disruption of renal MV integrity and function plays a pivotal role in the progression of renal injury in the stenotic kidney. Furthermore, it shows a high level of plasticity of renal microvessels to a single-dose VEGF-targeted intervention after established renal injury, supporting promising renoprotective effects of a novel potential therapeutic intervention to treat chronic RVD.

Keywords: angiogenesis, renal artery stenosis, microcirculation, imaging

renal artery stenosis (RAS) is a major cause of chronic renovascular disease (RVD), whose incidence increases with age and currently affects 18% of individuals between the ages of 65 and 74 yr, and over 40% of those older than 75 (9). Moreover, RVD is often progressive and may account for up to 16% of all cases of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease (9, 13). As the US population continues to age, RVD will increasingly represent a major health problem and economic burden. Hence, identification of potential therapeutic targets to modify the progressive nature of renal injury in RVD could provide significant benefit.

The microcirculation is a vital component of the normal functioning of any organ. Emerging evidence supports microvascular (MV) disease as a contributor to progressive renal injury (15, 26). Glomerular and peritubular MV damage and loss have been linked to renal functional impairment and progression of renal damage in chronic renal disease (11) and renal graft function (28). Furthermore, we have previously shown in a model of chronic RAS (as a surrogate of chronic RVD) that MV density and function are significantly reduced in the stenotic kidney (6, 15, 32) and that these changes are evident as early as 6 wk after initiation of RAS (15) and accompanied by a significant deterioration in renal function and marked renal fibrosis. However, the underlying mechanisms are unknown and targeted interventions are scarce.

We have recently shown that preservation of the renal microvasculature in the stenotic kidney can greatly attenuate the loss of renal function and the development of renal fibrosis (3, 15). In this proof-of-concept study using a model of chronic RAS, a single intrarenal administration of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was performed at the onset of RAS and before development of renal damage. We demonstrated that endogenous levels of VEGF decreased significantly in the stenotic kidney (6, 15, 32) as RAS and renal damage evolve and that intrarenal administration of this cytokine was effective in preserving renal hemodynamics, function, and MV density (15). However, whether using this approach at a later stage could reverse the progression of disease in the stenotic kidney and the mechanisms involved is still unclear.

The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that intrarenal VEGF therapy will reverse established renal dysfunction and decrease renal injury in a model of chronic RAS that mimics RVD. We determined 1) whether intrarenal VEGF administration could slow down or reverse the progression of renal injury in the stenotic kidney and therefore whether VEGF therapy could provide a novel clinical approach in the treatment of RVD; and 2) the mechanisms behind the progressive decrease in renal VEGF and its effects in the stenotic kidney. We used a well-established swine model that mimics human chronic RVD (4, 5, 17). VEGF was administered intrarenally in the stenotic kidney after 6 wk of RAS and established renal injury, to closely reproduce a therapeutic approach that could be used in patients. Furthermore, in vitro studies were performed by exposing proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTEC; one of the main sources of VEGF in the kidney) to chronic hypoxia to elucidate the potential causes of the progressive decrease in VEGF and deterioration of the angiogenic signaling in the stenotic kidney.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In Vivo and Ex Vivo Studies: Stenotic Kidney

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Mississippi Medical Center approved all the procedures. Twenty-one prejuvenile domestic pigs (60–65 kg) were observed for 10 wk. In 14 pigs, unilateral RAS (a surrogate and cause of RVD) was induced at baseline, as previously shown (4, 5, 17). Additional animals were used as normal controls (normal; n = 7). Blood pressure was chronically measured and recorded at 5-min intervals and averaged for each 24-h period using a telemetry system (PhysioTel, Data Sciences International) (4, 5, 15, 17).

Six weeks after induction of RAS, all pigs underwent renal angiography to quantify the degree of renal artery stenosis. The pigs were anesthetized with intramuscular telazol (5 mg/kg) and xylazine (2 mg/kg), intubated, and mechanically ventilated on room air. Anesthesia was maintained with a mixture of ketamine (0.2 mg·kg−1·min−1) and xylazine (0.03 mg·kg−1·min−1) in normal saline and administered via an ear vein cannula (0.05 mg·kg−1·min−1). Under sterile conditions and fluoroscopic guidance, renal angiography was performed and stenosis was quantified as previously described (15). After angiography, the catheter was positioned in the superior vena cava, and in vivo helical multidetector computer tomography (MDCT) flow studies were performed for quantification of single-kidney renal blood flow (RBF; ml/min), perfusion (ml·min−1·g tissue−1), and glomerular filtration rate (GFR; ml/min), as previously validated (4, 8, 16).

After completion of the MDCT in vivo studies, the pigs were randomized into two groups: those that received vehicle (RAS, n = 7) and those treated with a single intrarenal infusion of rhVEGF (0.05 μg/kg, RAS+EGF, n = 7), as described recently (3, 15). Pigs were then observed for 4 additional wk, and in vivo studies were repeated at 10 wk.

Renal vascular resistance was calculated at 6 and 10 wk by dividing the mean arterial pressure (measured during the in vivo studies) and MDCT-derived RBF. Blood from the inferior vena cava and renal veins (from the stenotic kidney) were collected at 6 and 10 wk to measure plasma renin activity (PRA) and serum creatinine (SCr), as described (4, 15).

Upon completion of all the 10-wk in vivo studies, the pigs were allowed 2 days to recover and then euthanized by an intravenous overdose of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg). The kidneys were immediately removed using a retroperitoneal incision and immersed in heparinized saline (10 units/ml). One lobe was used for micro-computed tomography (CT) reconstruction. Another lobe was removed from one end of the kidney, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C to quantify the protein expression of the angiogenic and survival factors hypoxia-induced factors (HIF)-1α, VEGF, total and phosphorylated ERK 1/2, angiopoietin (Ang)-1, and the specific Ang-1 receptor Tie-2, phosphorylated (p)-Akt, and phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (p-eNOS). Finally, another portion of the kidney was preserved in 10% formalin and used to investigate renal morphology in midhilar renal cross sections stained with trichrome (3, 15).

MDCT analysis.

Manually traced regions of interest were selected in MDCT images in the aorta, renal cortex, medulla, and papilla, and their densities were sampled. Time-density curves were generated and fitted with extended γ-variate curve fits. The area under each segment of the curve and its first moment were calculated using curve-fitting parameters and used to calculate single-kidney RBF (ml/min), GFR (ml/min), and regional perfusion (ml·min−1·g tissue−1) using previously validated methods (8, 16).

Micro-CT.

The stenotic kidney was perfused (Syringe Infusion Pump 22, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) with an intravascular contrast agent (Microfil MV122, Flow Tech, Carver, MA). The kidney samples were scanned at 0.3° increments using a micro-CT scanner and reconstructed at 9-μm resolution for subsequent analysis using the Analyze software package (Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), as previously described (15). The cortex was tomographically divided, and the spatial density and distribution of microvessels (diameters 0–500 μm) and vascular volume fraction (the ratio of the sum of cross-sectional areas of all vessels and the total area of the region of interest) were calculated, as previously described (15).

Western blotting.

Standard blotting protocols in renal cortical tissue homogenates were followed, as previously described (5), using specific polyclonal antibodies against HIF-1α (1:1,000, Cell Signaling, Boston, MA), VEGF, phosphorylated (p)-ERK-1, p-Akt, Ang-1, and Tie-2, and p-eNOS (1:200 for all, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). β-Actin (1:500, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used as a loading control. Protein expression (1 band/animal) was quantified using densitometry and averaged in each group.

Histology.

Midhilar 5-μm paraffin-embedded cross sections of each kidney (1/animal) stained with trichrome were examined, and staining was semiautomatically quantified (NIS Element 3.0, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) and expressed as the percentage of staining of total surface area, as described (4, 15). A glomerular score (percentage of sclerotic glomeruli) was assessed by recording the number of sclerotic glomeruli in 100 counted glomeruli as previously described (4, 15). Furthermore, immunoreactivity against VEGF and its specific receptor Flk-1 (1:50 for both, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was determined in renal cross sections (1/animal) following standard procedures.

In Vitro Studies: PTEC Exposed to Chronic Hypoxia

All the in vitro experiments were performed in duplicate.

Cell culture.

Proximal tubular porcine LLC-PK1 cells (PTEC) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). All cells were cultured in Medium 199 with low glucose, supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 50 U of penicillin/ml, 50 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 3% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. Cells were passed with TrypLE Select (Invitrogen) after they reached 80% confluence and utilized between passages 7 and 10 for all of the studies.

Hypoxic injury.

Cells (1.5 × 105) cells were seeded in each well of a six-well plate and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day, the plates were washed twice with PBS to remove any nonadhered cells. The plates were assigned randomly to either a control group or a hypoxic group. Three milliliters per well of fresh complete media was added to the control group and 3 ml/well of complete media that was preconditioned in the hypoxic chamber overnight was added to the hypoxic group. Plates were placed in a water-jacketed triple gas incubator at either 20% oxygen for normoxic conditions, or at 0.25% oxygen for hypoxic conditions by nitrogen purging. One plate for each group was incubated for 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h, and 2, 3, 4, and 7 days. At the end of each time point, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and total cell lysates were collected with fresh RIPA Lysis Buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were frozen in liquid nitrogen and saved for immunoblotting.

Cell viability and protein expression.

The plates were washed twice with PBS, and cells were detached with TrypLE Select (Invitrogen) and centrifuged at 125 g for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in 100-μl serum-free complete medium, and 10 μl of 0.4% Trypan Blue was added to the cell suspension. The mixture was allowed to incubate for 3 min, and cells were counted on a hemacytometer within 5 min to avoid reduced viability counts. Cell homogenates were obtained at each time point, and Western blotting was performed following standard procedures to measure the expression of HIF-1α (1:1,000, Cell Signaling), VEGF, p-ERK 1/2, and p-Akt (1:200 for all, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). β-Actin (1:500, Sigma) was used as a loading control.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons within groups were performed using paired Student's t-tests and among groups using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was accepted for P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

In Vivo Studies

General characteristics.

Blood pressure and the angiographic degree of stenosis were similar in RAS and RAS +VEGF-treated animals after 6 and 10 wk of observation (Tables 1 and 2, respectively, P < 0.01 vs. normal). PRA was similar among the groups after 6 (Table 1) and 10 wk (Table 2), as we have previously shown (4, 15) in chronic experimental renovascular hypertension. RVR was increased after 6 wk of RAS (Table 1), as we have previously shown (15), and remained elevated at 10 wk. However, RVR was normalized in RAS after VEGF administration (Table 2).

Table 1.

Mean arterial pressure, degree of stenosis, plasma renin activity, serum creatinine, and basal single-kidney hemodynamics and function after 6 wk of observation in normal, renovascular disease (renal artery stenosis, and renal artery stenosis pigs before treatment with intrarenal VEGF

| Parameter | Normal | RAS | RAS Before VEGF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 89.5 ± 2.1 | 128.7 ± 2.0* | 125.2 ± 3.7* |

| Plasma renin activity, ng·ml−1·h−1 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.03 |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/l | 87.9 ± 4.8 | 103.2 ± 2.1* | 101.3 ± 4.0* |

| Renal vascular resistance, mmHg·ml−1·min | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 0.4 ± 0.03* | 0.32 ± 0.07* |

| Renal volume, ml | |||

| Cortex | 114.6 ± 10.2 | 69.9 ± 6.5* | 74.4 ± 4.4* |

| Medulla | 35.5 ± 2.7 | 24.8 ± 2.5* | 26.5 ± 2.3* |

| Renal blood flow, ml/min | 522.5 ± 40.9 | 321.2 ± 68.3* | 393.6 ± 50.3* |

| Perfusion, ml·min−1·ml−1 | |||

| Cortex | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 0.6 |

| Medulla | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.4 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, ml/min | 54.3 ± 3.9 | 42.8 ± 7.2* | 43.4 ± 3.4* |

Values are means ± SE; n = 7/group.

RAS, renal artery stenosis.

P < 0.05 vs. normal.

†P < 0.05 vs. RAS.

Table 2.

Mean arterial pressure, degree of stenosis, plasma renin activity, serum creatinine, and basal single-kidney hemodynamics and function after 10 wk, in normal, renal artery stenosis, and renal artery stenosis pigs treated with intrarenal VEGF at 6 wk

| Parameter | Normal | RAS | RAS+VEGF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 88.1 ± 2.9 | 126.4 ± 6.1* | 121.7 ± 7.0* |

| Degree of stenosis, % | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 75.4 ± 6.7* | 73.6 ± 5.2* |

| Plasma renin activity, ng·ml−1·h−1 | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.4 ± 0.08 | 0.4 ± 0.09 |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/l | 88.3 ± 3.5 | 142.6 ± 12.2* | 103.3 ± 7.5* |

| Renal vascular resistance, mmHg·ml−1·min | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.46 ± 0.11* | 0.20 ± 0.04† |

| Renal volume, ml | |||

| Cortex | 109.7 ± 3.1 | 70.5 ± 9.0* | 108.0 ± 4.2† |

| Medulla | 35.1 ± 0.8 | 24.6 ± 2.0* | 36.5 ± 2.3† |

| Renal blood flow, ml/min | 543.5 ± 20.5 | 337.3 ± 80.1* | 607.0 ± 45.3† |

| Perfusion, ml·min−1·ml−1 | |||

| Cortex | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.3† |

| Medulla | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.4*† |

| Glomerular filtration rate, ml/min | 73.3 ± 3.9 | 44.0 ± 6.9* | 66.6 ± 10.3† |

Values are means ± SE; n = 7/group.

P < 0.05 vs. normal.

P < 0.05 vs. RAS.

MDCT-derived single-kidney hemodynamics and function.

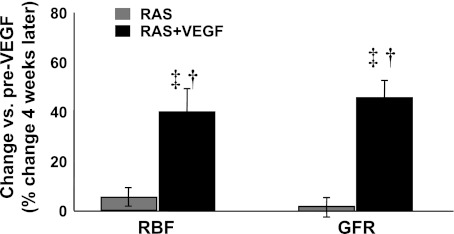

Stenotic kidney basal RBF and GFR were similarly reduced in all RAS animals at 6 wk, as we have observed in previous studies (15), accompanied by elevated SCr (Table 1). However, while in RAS RBF and GFR remained attenuated and SCr further increases at 10 wk, both were normalized in RAS +VEGF-treated pigs (Table 2) as a result of a significant increase in RBF and GFR compared with pre-VEGF data (Fig. 1). We observed a similar trend for cortical and medullary perfusion in RAS +VEGF kidneys (Tables 1 and 2). These improvements after VEGF administration were accompanied by a significantly lower SCr (albeit not normalized) compared with RAS (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Paired comparisons of basal renal blood flow (RBF) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) before (6 wk) and after intrarenal VEGF administration (10 wk). Intrarenal VEGF in renal artery stenosis (RAS) significantly improved renal hemodynamics and filtration function in the stenotic kidney. †P < 0.05 vs. RAS. ‡P < 0.05 vs. 6 wk pre-VEGF administration.

Ex Vivo Studies in the Stenotic Kidney

MV 3D architecture.

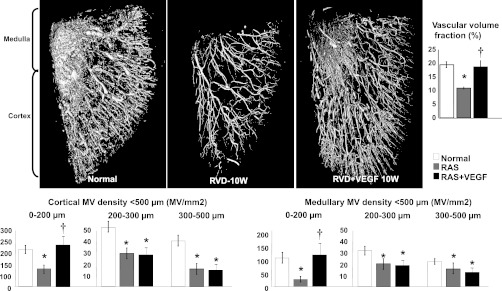

The density of microvessels with diameters <200 μM in the stenotic kidney (which includes interlobar, arcuate, radial, and smaller microvessels) were significantly decreased throughout the renal cortex and medulla in untreated RAS after 10 wk (P < 0.05 vs. normal, Fig. 2). Remarkably, VEGF administration at 6 wk led to a significant increase in cortical and medullary MV density, which was mainly due to a distinct increase in the density of MV with diameters <200 μM. The density of MV with diameters between 200 and 500 μM remained similarly attenuated, suggesting increased MV sprouting in RAS+VEGF-treated kidneys (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Representative 3-dimensional micro-computed tomography (CT) reconstruction and quantification of the cortical and medullary microvascular (MV) density and vascular volume fraction (top) in normal, RAS, and RAS+VEGF kidneys. Intrarenal VEGF administration after 6 wk of RAS led to a significant MV sprouting, reflected in the restored cortical and medullary MV density of microvessels between 0 and 200 μM. Restoration of renal hemodynamics and function (as shown in Table and Fig. 1) supports the notion that these new vessels were also functional. *P < 0.05 vs. normal. †P < 0.05 vs. RAS.

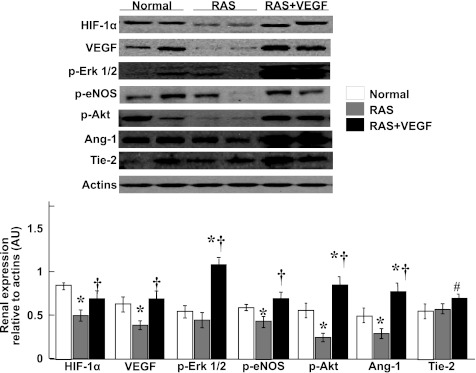

Angiogenic factors.

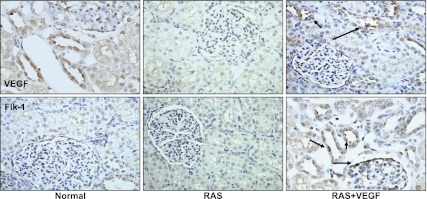

VEGF administration in the stenotic kidney restored its renal expression at the MV, tubular, and glomerular compartments (Figs. 3 and 4). Furthermore, intrarenal VEGF augmented the expression of HIF-1α, p-ERK 1/2, p-Akt, p-eNOS, and Ang-1/Tie-2 (Fig. 3), which are key mediators of VEGF effects.

Fig. 3.

Representative renal protein expression (n = 7/group, 2 representative bands shown) and quantification of hypoxia-induced factor (HIF)-1α, VEGF, phosphorylated (p)-ERK 1/2, p-Akt, p-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and angiotensinogen (Ang)-1/Tie-2. Intrarenal administration of VEGF restored renal expression of VEGF and angiogenic mediators. *P < 0.05 vs. normal. †P < 0.05 vs. RAS. #P = 0.08 vs. RAS.

Fig. 4.

Representative renal cross sections showing immunostaining (×40) against VEGF and its specific Flk-1 receptor in normal, renal artery stenosis (RAS), and RAS+VEGF kidneys. The blunted expression of VEGF and Flk-1 in RAS was augmented mainly in the glomerular and tubular compartments of the stenotic kidney after VEGF administration.

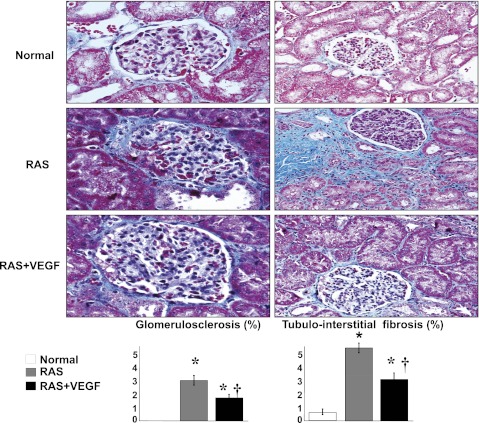

Renal fibrosis in the stenotic kidney was evident in the cortex, while no significant changes were observed in the renal medulla. As we previously showed (4), the stenotic kidney showed glomerulosclerosis, perivascular, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. RAS+VEGF-treated kidneys showed a decrease in the overall renal fibrosis (P < 0.05 vs. RAS) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Representative glomeruli (×40) and tubulointerstitial region (×20) shown as examples to illustrate fibrosis and quantification in normal, RAS, and RAS+VEGF kidneys. VEGF administration after 6 wk attenuated renal fibrosis, but did not fully reversed renal damage. *P < 0.05 vs. normal. †P < 0.05 vs. RAS.

In Vitro Studies in PTEC

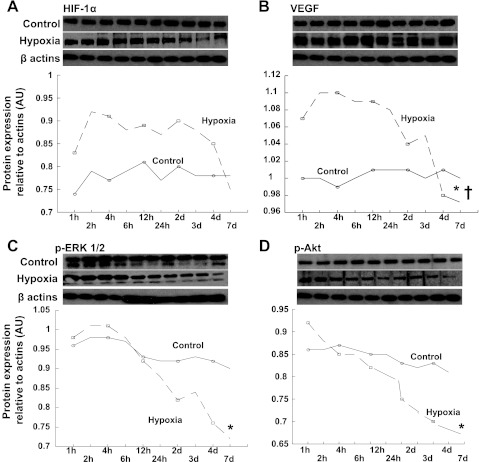

Cell viability was similar in controls and PTEC exposed to severe hypoxia during the first 6 h of observation (99.2 ± 0.4 vs. 99.1 ± 0.3%, P = not significant). Then, cell viability started to decrease and was significantly reduced after 7 days of exposure to severe hypoxia compared with controls (91.2 ± 2.4 vs. 96.1 ± 0.6%, P = 0.02). The hypoxic cells showed sustained increased expression of HIF-1α compared with controls (Fig. 6A) that started to decrease (albeit not significantly) after 4 days. On the other hand, PTEC showed an early increased expression of VEGF that peaked after 6 h of hypoxia, then reached a plateau and decreased progressively from 24 h to 7 days (Fig. 6B). This was accompanied by a significant and progressive decrease in expression of p-ERK 1/2 and p-Akt (Fig. 6, C and D), which concurred with the findings in the stenotic kidney. Interestingly, decreases in p-ERK 1/2 and p-Akt started within one h of hypoxia, preceding the decrease in VEGF and progressing thereafter.

Fig. 6.

Full blot and quantification of protein expression of HIF-1α (A), VEGF (B), p-ERK1/2 (C), and p-Akt (D) in control (solid lines) and hypoxic PTEC (dotted lines) at sequential time points. HIF-1α showed a sustained increased expression during the first 72 h and then started to decrease after 4 days of hypoxia. However, expression of VEGF showed an early peak at 6 h, which then reached a plateau and started to decrease after 24 h, whereas phosphorylated ERK 1/2 and Akt progressively decreased from the beginning, and this was accentuated as chronic hypoxia evolved. *P < 0.05 vs. measurement at 1 h, †P < 0.05 vs. measurement at peak.

DISCUSSION

The current study supports the potential and feasibility of a novel therapeutic approach to treat the stenotic kidney in chronic experimental RVD. A single intrarenal infusion of VEGF after 6 wk of RAS and established renal damage largely reversed renal dysfunction by restoring RBF, GFR, and perfusion in the stenotic kidney. These beneficial effects were accompanied by a significant expansion of the renal cortical and medullary MV bed likely via sprouting from preexisting vessels. The results therefore suggest not only that VEGF can promote neovascularization in the stenotic kidney but also that the newly formed blood vessels were functional.

Vascular nephropathies in humans can compromise renal function and promote progressive renal injury. Although the obstruction of large vessels in organs such as the heart and kidneys could be accurately identified and promptly resolved by catheter-based interventions, established pathological changes in the smaller vessels within the organ are difficult to target. Furthermore, the role that MV disease may play in the progression of renal tissue injury in RVD is unclear, and the availability of targeted interventions to protect the microvasculature is still in the experimental stages. For these reasons, a better mechanistic understanding of new therapeutic approaches for the treatment of renal MV disease is needed, and advances in this field could have a significant impact clinically.

VEGF is a prominent angiogenic cytokine that plays a crucial role in maintaining MV networks, including those in the kidney. By stimulating the migration of endothelial cell progenitors (19, 33), VEGF promotes vascular proliferation and repair during developmental phases and also in ischemic or hypoxic tissues. A decrease in renal VEGF and its signaling pathways has been observed in progressive kidney disease (23). We have recently shown that VEGF levels progressively decrease in the stenotic kidney of our model of chronic RAS (6, 15, 32). This decrease in VEGF parallels MV damage and loss and deterioration of renal function, and all these deleterious changes in the stenotic kidney are evident as early as after 6 wk of RAS (15). The decrease in renal VEGF was puzzling, since hypoxia is a powerful stimulus for VEGF secretion, as has been shown in vitro (21). Nevertheless, it has also been suggested that long-term exposure to a hypoxic insult may decrease VEGF at a later stage (22), suggesting a possible biphasic regulation of VEGF. To investigate whether this may occur in the stenotic kidney, we exposed PTEC (one of the main sources of VEGF in the kidney) (25) to chronic hypoxia and determined the viability of the cells and changes in the expression of VEGF at sequential time points. We observed similar cell viability with an early peak in VEGF expression after 6 h of hypoxia. Cell viability started to decrease after 6 h in hypoxic PTEC, as an expression of VEGF entered in a plateau phase until 24 h and then progressively and rapidly decreased thereafter, going below control levels after 7 days of hypoxia. Furthermore, the decrease in VEGF was preceded and followed by a progressive decrease in the expression of downstream mediators such as p-Akt and p-ERK 1/2, which started to decrease within the first hour of hypoxia and progressed afterward. It is interesting that these changes in hypoxic PTEC were accompanied by increased expression of HIF-1α, one of the most potent upstream transcription factors stimulating VEGF, which started to decrease after 4 days. Although we are aware that cells were likely exposed to a more severe hypoxia in vitro than what we may observe in vivo in our model or in a clinical scenario, this observation suggests that there is likely a progressive disruption of VEGF signaling in renal cells as hypoxia advances. Furthermore, it also shows that the accompanying early and evolving loss of downstream mediators of VEGF combined with a progressive loss of sources and altered VEGF transcriptional mechanisms (10, 14) may have contributed to the decrease in renal VEGF bioavailability and signaling, consequently blunting MV repair and favoring MV loss.

We have recently shown that preventing the decrease in VEGF in the stenotic kidney via an intrarenal administration of this cytokine at the onset of RAS preserved MV density and function and decreased renal injury (3, 15). The current study extends these observations by demonstrating that an intrarenal administration of VEGF at a later stage of RAS and established renal injury can largely reverse renal dysfunction in the stenotic kidney. Because this model of therapy mimics the clinical situation where the initial time point of RVD cannot be exactly determined, we can propose intrarenal administration of VEGF as a potential therapeutic approach to treat chronic RVD.

VEGF has a short half-life and despite some retention in the kidney after infusion, it is unlikely that all the effects we observed 4 wk later were driven by this mechanism. A single dose of VEGF significantly increased renal p-ERK 1/2, indicating augmented activity of this factor that plays a crucial role in stabilizing and prolonging the mRNA half-life of VEGF (10). ERK 1/2 is also a powerful stimulus for differentiation of multipotent progenitor cells into an endothelial phenotype (30). In turn, VEGF can promote sustained phosphorylation of ERK (29), suggesting a feed-forward mechanism that may have augmented the glomerular and tubular expression of VEGF and mediators and facilitated MV proliferation in the stenotic kidney. Administration of VEGF also increased the renal expression of p-Akt, a key prosurvival factor, and Ang-1/Tie-2, which together with VEGF and Akt promote vascular proliferation and the maturation of the newly generated vessels (7, 27) and in turn can stimulate HIF-1α (31). Also, Ang-1 is a powerful stimulus for mobilization (as is VEGF) (1) and homing of cell progenitors to ischemic tissues, which are key steps for neovascularization (24).

After 10 wk of RAS, MV damage and loss in the stenotic kidney affects not only the cortex but also the medulla. This finding reflects a progression of renal injury in the stenotic kidney since at 6-wk MV rarefaction is only observed in the renal cortex (15). A single intrarenal infusion of VEGF after 6 wk of RVD restored cortical and medullary MV density in those vessels with diameters <200 μM, whereas the density of larger microvessels between 200 and 500 μM remained attenuated. This distinct increase suggests augmented MV sprouting from preexisting vessels, a well-known proangiogenic effect of VEGF (2, 12). The increased renal microvasculature in the RAS+VEGF kidney might have also been promoted by increased p-eNOS, which suggests augmented activity and possibly increased NO bioavailability. It has been shown that eNOS-derived NO plays an important role in the initial MV sprouting induced by VEGF (18) and that the NO-VEGF axis provides resistance to injury of tubular epithelial cells and glomerular endothelial cells (20). Therefore, our study indicates that administration of VEGF after established renal injury improved the angiogenic cascade leading to augmented MV proliferation, which was evident throughout the renal compartments.

The potential functional significance of the improved renal vasculature was quantified in vivo in the stenotic kidney using MDCT 4 wk after VEGF administration. The untreated stenotic kidney showed blunted RBF and GFR both at 6 wk and after 10 wk compared with normal controls. SCr was increased at 6 wk and further elevated after 10 wk of RAS, suggesting progression of renal injury. However, intrarenal administration of VEGF restored RBF, GFR, and improved perfusion at 10 wk compared with the 6-wk, pre-VEGF data, indicating a reversal of renal dysfunction and, more importantly, suggesting functionality of the newly generated vessels. In addition, an augmented vasodilatation of the new and preexistent vessels (mainly in the preglomerular vasculature) via an VEGF-induced increased NO may have also contributed to the improvement observed in RAS+VEGF kidneys.

The decreased fibrosis in the RAS+VEGF kidney should be viewed with caution. We recently showed that the stenotic kidney presents significant glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial, and perivascular fibrosis after 6 wk (15) and that these changes were largely prevented by intrarenal administration of VEGF at the onset of RAS. Hence, since we quantified fibrosis at a later time point (10 wk), it is possible that the improvements in tissue damage we observed in the current study compared with untreated time controls are due to a significant slowdown of the progression of renal injury rather than actual reversal of established renal damage. This notion is also underscored by the unchanged SCr in RAS+VEGF between 6 and 10 wk, unlike untreated RAS kidneys which show a progressive increase in SCr. The remaining injury in the stenotic (and contralateral, as we have shown) (15) kidney may partly explain the lack of a decrease in hypertension in RAS+VEGF, which could possibly be sustained via impaired renal water and sodium handling. However, the reasons behind the persistence of hypertension in RAS+VEGF are not entirely clear.

Limitations

We are aware that this study could be considered mainly as observational, and future research is needed to dissect these mechanisms in other experimental platforms or models that allows additional manipulations (e.g., genetically altered mice or rats). On another note, it is possible that some of the newly generated vessels could be shunting preglomerular vessels that may have artifactually increased GFR, and examination with, for example, inulin clearance (16) in RAS+VEGF, will further define the contribution to renal function of the newly generated vessels. Furthermore, the degree of renal fibrosis is still relatively mild at this point, and future studies using this intervention at later stages, with more severe renal scarring, will better define the potential therapeutic use of VEGF. Finally, since the main etiology of human RAS is atherosclerosis, determining the potential of an intrarenal administration of VEGF in a model of atherosclerotic RAS (4, 5) will expand the current observations.

In summary, the current study shows promising therapeutic effects of a targeted renal intervention, using an established clinically relevant large-animal model of RAS that mimics chronic RVD. This study also illustrates the biphasic regulation of VEGF in the kidney under chronic hypoxic conditions and underscores the importance of MV rarefaction on the progression of injury in the stenotic kidney. In turn, it also implies a high level of plasticity of renal microvessels to a single-dose VEGF intervention after established renal injury. More studies are needed to solidify the feasibility and extent of this intervention by applying it at a more advanced stage of disease and also to determine its potential as a treatment for patients in which revascularization is not warranted. Slowing down the progression of renal injury may certainly increase the chances of renal recovery after revascularization. Moreover, these results also offer the potential to consider VEGF as a viable coadjuvant intervention that may improve the responses to established treatments in the stenotic kidney, such as catheter-based interventions, in which improvements in renal function are still observed in only one-third of patients.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL095638 and HL 051971.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.R.C. provided conception and design of research; A.R.C. and S.K. performed experiments; A.R.C. and S.K. analyzed data; A.R.C. interpreted results of experiments; A.R.C. prepared figures; A.R.C. drafted manuscript; A.R.C. edited and revised manuscript; A.R.C. and S.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Asahara T, Takahashi T, Masuda H, Kalka C, Chen D, Iwaguro H, Inai Y, Silver M, Isner JM. VEGF contributes to postnatal neovascularization by mobilizing bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. EMBO J 18: 3964– 3972, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Besse S, Boucher F, Linguet G, Riou L, De Leiris J, Riou B, Dimastromatteo J, Comte R, Courty J, Delbe J. Intramyocardial protein therapy with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-165) induces functional angiogenesis in rat senescent myocardium. J Physiol Pharmacol 61: 651– 661, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chade AR, Kelsen S. Renal microvascular disease determines the responses to revascularization in experimental renovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 3: 376– 383, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Grande JP, Krier JD, Lerman A, Romero JC, Napoli C, Lerman LO. Distinct renal injury in early atherosclerosis and renovascular disease. Circulation 106: 1165– 1171, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Grande JP, Zhu X, Sica V, Napoli C, Sawamura T, Textor SC, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Mechanisms of renal structural alterations in combined hypercholesterolemia and renal artery stenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 1295– 1301, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chade AR, Zhu X, Mushin OP, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Simvastatin promotes angiogenesis and prevents microvascular remodeling in chronic renal ischemia. FASEB J 20: 1706– 1708, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen JX, Stinnett A. Disruption of Ang-1/Tie-2 signaling contributes to the impaired myocardial vascular maturation and angiogenesis in type II diabetic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 1606– 1613, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Daghini E, Primak AN, Chade AR, Krier JD, Zhu XY, Ritman EL, McCollough CH, Lerman LO. Assessment of renal hemodynamics and function in pigs with 64-section multidetector CT: comparison with electron-beam CT. Radiology 243: 405– 412, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dworkin LD, Murphy T. Is there any reason to stent atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis? Am J Kidney Dis 56: 259– 263, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Essafi-Benkhadir K, Pouyssegur J, Pages G. Implication of the ERK pathway on the post-transcriptional regulation of VEGF mRNA stability. Methods Mol Biol 661: 451– 469, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Futrakul N, Butthep P, Patumraj S, Siriviriyakul P, Futrakul P. Microvascular disease and endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney diseases: therapeutic implication. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 34: 265– 271, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gerhardt H. VEGF and endothelial guidance in angiogenic sprouting. Organogenesis 4: 241– 246, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, Cherr GS, Jackson SA, Appel RG, Burke GL, Dean RH. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg 36: 443– 451, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hellwig-Burgel T, Stiehl DP, Katschinski DM, Marxsen J, Kreft B, Jelkmann W. VEGF production by primary human renal proximal tubular cells: requirement of HIF-1, PI3-kinase and MAPKK-1 signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem 15: 99– 108, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iliescu R, Fernandez SR, Kelsen S, Maric C, Chade AR. Role of renal microcirculation in experimental renovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 1079– 1087, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krier JD, Ritman EL, Bajzer Z, Romero JC, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Noninvasive measurement of concurrent single-kidney perfusion, glomerular filtration, and tubular function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F630– F638, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lerman LO, Schwartz RS, Grande JP, Sheedy PF, Romero JC. Noninvasive evaluation of a novel swine model of renal artery stenosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1455– 1465, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lu Y, Xiong Y, Huo Y, Han J, Yang X, Zhang R, Zhu DS, Klein-Hessling S, Li J, Zhang X, Han X, Li Y, Shen B, He Y, Shibuya M, Feng GS, Luo J. Grb-2-associated binder 1 (Gab1) regulates postnatal ischemic and VEGF-induced angiogenesis through the protein kinase A-endothelial NOS pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 2957– 2962, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moore MA, Hattori K, Heissig B, Shieh JH, Dias S, Crystal RG, Rafii S. Mobilization of endothelial and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by adenovector-mediated elevation of serum levels of SDF-1, VEGF, and angiopoietin-1. Ann NY Acad Sci 938: 36– 45, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morita T, Kakinuma Y, Kurabayashi A, Fujieda M, Sato T, Shuin T, Furihata M, Wakiguchi H. Conditional VHL gene deletion activates a local NO-VEGF axis in a balanced manner reinforcing resistance to endothelium-targeted glomerulonephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 4023– 4031, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nakagawa T, Lan HY, Zhu HJ, Kang DH, Schreiner GF, Johnson RJ. Differential regulation of VEGF by TGF-β and hypoxia in rat proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F658– F664, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Hein TW, Olszewska P, Carney DH. Chronic hypoxia attenuates VEGF signaling and angiogenic responses by downregulation of KDR in human endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C1162– C1170, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rudnicki M, Perco P, Enrich J, Eder S, Heininger D, Bernthaler A, Wiesinger M, Sarkozi R, Noppert SJ, Schramek H, Mayer B, Oberbauer R, Mayer G. Hypoxia response and VEGF-A expression in human proximal tubular epithelial cells in stable and progressive renal disease. Lab Invest 89: 337– 346, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saif J, Schwarz TM, Chau DY, Henstock J, Sami P, Leicht SF, Hermann PC, Alcala S, Mulero F, Shakesheff KM, Heeschen C, Aicher A. Combination of injectable multiple growth factor-releasing scaffolds and cell therapy as an advanced modality to enhance tissue neovascularization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 1897– 1904, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schrijvers BF, Flyvbjerg A, De Vriese AS. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int 65: 2003– 2017, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sila-asna M, Bunyaratvej A, Futrakul P, Futrakul N. Renal microvascular abnormality in chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail 28: 609– 610, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Somanath PR, Chen J, Byzova TV. Akt1 is necessary for the vascular maturation and angiogenesis during cutaneous wound healing. Angiogenesis 11: 277– 288, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steegh FM, Gelens MA, Nieman FH, van Hooff JP, Cleutjens JP, van Suylen RJ, Daemen MJ, van Heurn EL, Christiaans MH, Peutz-Kootstra CJ. Early loss of peritubular capillaries after kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1024– 1029, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Swendeman S, Mendelson K, Weskamp G, Horiuchi K, Deutsch U, Scherle P, Hooper A, Rafii S, Blobel CP. VEGF-A stimulates ADAM17-dependent shedding of VEGFR2 and crosstalk between VEGFR2 and ERK signaling. Circ Res 103: 916– 918, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xu J, Liu X, Jiang Y, Chu L, Hao H, Liua Z, Verfaillie C, Zweier J, Gupta K, Liu Z. MAPK/ERK signalling mediates VEGF-induced bone marrow stem cell differentiation into endothelial cell. J Cell Mol Med 12: 2395– 2406, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Youn SW, Lee SW, Lee J, Jeong HK, Suh JW, Yoon CH, Kang HJ, Kim HZ, Koh GY, Oh BH, Park YB, Kim HS. COMP-Ang1 stimulates HIF-1alpha-mediated SDF-1 overexpression and recovers ischemic injury through BM-derived progenitor cell recruitment. Blood 117: 4376– 4386, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhu XY, Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Bentley MD, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Cortical microvascular remodeling in the stenotic kidney: role of increased oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1854– 1859, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zisa D, Shabbir A, Mastri M, Suzuki G, Lee T. Intramuscular VEGF repairs the failing heart: role of host-derived growth factors and mobilization of progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R1503– R1515, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]