Abstract

One of the critical issues in Parkinson disease (PD) research is the identity of the specific toxic, pathogenic moiety. In PD, mutations in alpha-synuclein (αsyn) or multiplication of the SNCA gene encoding αsyn, result in a phenotype of cellular inclusions, cell death, and brain dysfunction. While the historical point of view has been that the macroscopic aggregates containing αsyn are the toxic species, in the last several years evidence has emerged that suggests instead that smaller soluble species - likely oligomers containing misfolded αsyn - are actually the toxic moiety and that the fibrillar inclusions may even be a cellular detoxification pathway and less harmful. If soluble misfolded species of αsyn are the toxic moieties, then cellular mechanisms that degrade misfolded αsyn would be neuroprotective and a rational target for drug development. In this review we will discuss the fundamental mechanisms underlying αsyn toxicity including oligomer formation, oxidative stress, and degradation pathways and consider rational therapeutic strategies that may have the potential to prevent or halt αsyn induced pathogenesis in PD.

Keywords: Alpha-synuclein, Parkinson’s disease, chaperones, oligomers, heat shock proteins, oxidative stress, degradation, neurodegeneration

ALPHA-SYNUCLEIN AGGREGATION AS A THERAPEUTIC TARGET FOR PARKINSON’S DISEASE

There is strong evidence to suggest that alpha-synuclein (αsyn) accumulation is an early step in the pathogenesis of both sporadic and familial Parkinson’s disease (PD). Mutations in the 3syn gene (A30P, E46K, and A53T) are associated with rare familial forms of PD [1–3], and 3syn is abundant in Lewy bodies (LBs) even in sporadic PD [4, 5]. Moreover, increased expression of αsyn in the brain due to the duplication and triplication of the SNCA gene encoding αsyn, results in PD in rare cases [6, 7]. In animal models, overexpression of 3syn in transgenic mice [8, 9], rat and mouse viral vector models [10–14] and Drosophila [15] leads to 3syn aggregation and toxicity in the dopaminergic system. Therefore, an entire class of neurodegenerative diseases, referred to collectively as the “synucleinopathies” [16], appear to result from the accumulation of 3syn in various central nervous system cell populations.

αSyn is a natively unfolded molecule that can self-aggregate to form oligomers and fibrillar intermediates [17–19]. LBs are small, round inclusions found in surviving neurons in PD and DLB brains. They are predominantly localized in the substantia nigra pars compacta, but can also be found in widespread cortical and subcortical regions [20]. αSyn is a major component of LBs and Lewy neurites [5, 21] and the protein is highly amyloidogenic and aggregates in vitro in a concentration-dependent manner to form fibrils reminiscent of those observed in LBs [22, 23]. αSyn is normally localized in the presynaptic compartment, however, in PD and DLB 3syn accumulates in aggregates with various morphologies within neurons [20]. For the most part, these aggregates are densely compact, and can be immunostained for multiple additional components, including the 3syn interacting protein, synphilin-1 [24, 25], ubiquitin, which suggests that protein misfolding or clearance is altered in cells that develop LBs [26], and chaperone proteins like heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), Hsp40 and Hsp27 [27, 28]. As expected, the conformation of 3syn in LBs is significantly different from 3syn in the neuropil, as assessed by Förster resonance energy transfer [29] and fluorescence lifetime imaging studies [30]. However, the conformation of 3syn found in disease tissue remains unknown, although it has been postulated that oligomeric species represent the toxic genus [8, 31–35]

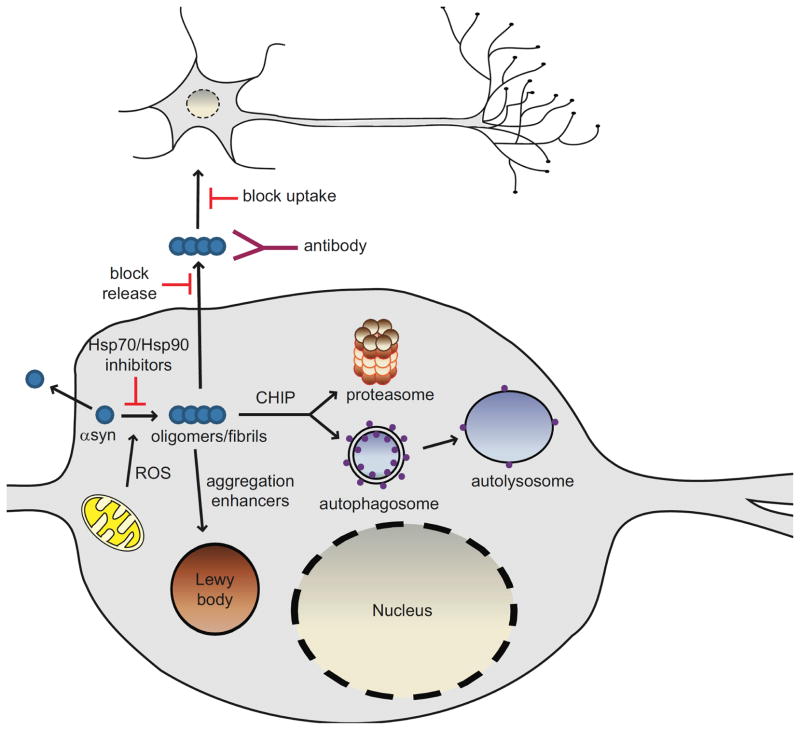

Given that the aggregation process of αsyn is a key factor in the development of PD and related synucleinopathies, molecules that inhibit αsyn oligomerization may lead to therapies to prevent or control these diseases as well as to a better understanding of the disease process (Fig. 1). Oligomerization of αsyn initiates with the dimerization of partially folded monomers [36, 37], followed by the formation of β-sheet rich nonfibrillar, oligomeric intermediates, also known as protofibrils. Protofibrils are transient β-sheet-containing oligomers that are formed during aggregation. Studies have shown that the presence of the disease-associated mutations in αsyn increase rates of self-assembly and fibrillization [23]. Current thinking is that it is the soluble, oligomeric/protofibrillar forms of αsyn that represent the toxic species rather than the insoluble fibrils found in LBs [8, 32–35, 38–44].

Fig. 1. Pathways of αsyn toxicity and potential therapeutic strategies.

Increasing evidence implicates soluble, oligomeric species of αsyn as the toxic genus in the pathogenesis of PD. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can modify αsyn such that it has an increased tendency to aggregate. Interventions that target oligomeric forms of αsyn by inducing degradation, preventing aggregation, or increasing aggregation in favor of less toxic fibrillar species are all being considered as therapeutic strategies. Oligomerization of αsyn can be prevented by Hsp70 overexpression or Hsp90 inhibition. Lewy bodies are thought to be a mechanism by which the cell sequesters abnormal, toxic proteins and as such, aggregation enhancers may offer innovative approaches to reduce αsyn toxicity. The enhancement of clearance of αsyn aggregates via the stimulation of degradation pathways could help mitigate αsyn-induced dysfunction in these pathways. CHIP directs proteins towards degradation via both the proteasome and lysosome making CHIP an extremely attractive therapeutic target. αSyn may also be released from living cells into the surrounding extracellular milieu but the species released (monomer or oligomer) remains to be determined. Extracellular αsyn could act as a seed to promote aggregation of αsyn in neighboring cells, ultimately leading to αsyn toxicity or Lewy body formation. Blocking αsyn release and/or uptake by neighboring cells might halt the spread of αsyn pathology. Lowering the extracellular oligomeric burden by immunotherapy may also be an innovative and novel approach in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

TARGETING αSYN OLIGOMERS AS THE CRITICAL TOXIC MOIETY

In PD, αsyn-misfolding and aggregation is thought to proceed via a seeding-nucleation mechanism. Speculation is that misfolded αsyn acts as a template for the conversion of the native α-helical form to a pathogenic β-sheet structure. Indeed, in vitro studies have revealed that αsyn aggregation is a nucleation-dependent process that initiates with the progression of monomer to oligomers to fibrils [23, 45]. An increasing number of studies now suggest that prefibrillar oligomers and protofibrils of αsyn, rather than mature fibrils, are the pathogenic species [8, 23, 39, 42, 46] and recent investigations have shown that a heterogenous population of αsyn oligomeric species may exist in equilibrium causing cell death either directly or indirectly [47].

αSyn oligomers can be generated in vitro from recombinant protein and many protocols exist describing the production of these oligomers [47–49]. Recently, assays to monitor cell produced αsyn oligomers have been described for living cells in culture [50, 51] and in vivo region-specific αsyn oligomers have been detected. It seems that in vivo composition and conformation of αsyn oligomers are crucial to contribute to neuronal dysfunction [52].

How αsyn oligomers induce cellular toxicity is not fully understood. Most recently, a in vitro study showed that αsyn oligomers can inhibit Hsp70 activity [53] and another study demonstrated that αsyn oligomers are capable of altering both pre- and postsynaptic alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4- isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA)-receptor mediated synaptic transmission [54]. Dysregulation in calcium homeostasis and changes in cell membrane permeability have previously been suggested as consequences of αsyn oligomers [47, 55, 56].

Recent methodological advances in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy have enabled determination of the 3D structure of αsyn fibrils at residue-level resolution. Common thinking is that amyloids constitute parallel β-sheets, in which individual polypeptide chains run roughly perpendicular to the major axis of the fibril and are stacked in-register [57]. However, new studies suggest that a structural disorder exists in amyloids which accommodates destabilizing residues and facilitates secondary interactions between different protofibrils [57]. To date it is still unknown how the structural transition from an initial globular or intrinsically disordered state to a highly ordered regular form in the amyloid occurs. Although αsyn is intrinsically unfolded and uncomplexed it differs from the random coil model. Electrostatic interactions and charged residues in the αsyn sequence may help nucleate the folding of the protein into an 3-helical structure and confer protection from misfolding [58]. Moreover, it is thought that at low pH the N-terminus carries a large positive charge, while at neutral pH it has a balance of positively and negatively charged residues. A locally collapsed C-terminus at low pH, which becomes highly hydrophobic under these conditions, is involved in the earliest stages of 3syn aggregation. These data indicate the importance of the charge distribution in directing both the mechanism and the rates of aggregation [59, 60].

MODIFIERS OF αSYN AGGREGATION AND TOXICITY

Reducing Oxidative Stress to Influence αsyn Aggregation and Related Toxicity

It is thought that, in idiopathic PD, epigenetic rather than genetic events are responsible for initiation of degeneration in dopaminergic neurons, eventually leading to cell death. Although the nature of neurotoxins that cause degeneration in dopaminergic neurons in PD is not well understood, oxidative stress is one of the risk factors that could promote degeneration of these neurons by influencing αsyn toxicity. A critical interaction between αsyn, oxidative stress, and PD is supported by experiments that demonstrate both in vitro and in vivo that oxidative stress promotes the formation of αsyn aggregates and inclusions [61, 62]. Mitochondrial dysfunction has long been implicated in the pathogenesis of PD. Evidence first emerged following the accidental exposure of drug users to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), an environmental toxin that results in acute parkinsonian syndrome. The active metabolite of MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), is an inhibitor of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and a substrate for the dopamine transporter. MPP+ accumulates in dopaminergic neurons causing toxicity [63]. Importantly, complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain is decreased in the substantia nigra of patients with PD, establishing a link between MPTP toxicity and idiopathic PD [64]. Furthermore, MPP+ is capable of inhibiting complex I activity [65, 66] leading to enhanced H2O2 generation and αsyn aggregation [67]. More recent studies in rats have found that administration of the complex I inhibitor rotenone leads to the development of a PD-like syndrome with neuronal degeneration and αsyn immunopositive inclusions [68].

Several PD-associated genes have been identified so far and of them four, αsyn, DJ-1, PINK1, and Parkin have been linked to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [69–71]. A relationship between αsyn and mitochondria has been suggested by several lines of evidence. αSyn null mice are resistant to MPTP-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons [72]. Furthermore, αsyn overexpressing transgenic mice develop significantly greater mitochondrial abnormalities when treated with MPTP than saline-treated controls [73] and overexpression of αsyn impairs mitochondrial function and promotes oxidative stress [74]. Most recently, αsyn has been demonstrated to colocalize with mitochondria in the midbrain of mice [75], and with mitochondrial membranes when overexpressed in cells in culture [76], providing evidence to physically link αsyn to mitochondria. The localization of αsyn to mitochondrial membranes results in the release of cytochrome c and an increase in mitochondrial calcium and nitric oxide [76]. Other studies have identified a cryptic mitochondrial targeting signal in the N-terminal 32 amino acids of αsyn that is responsible for a subsequent reduction in mitochondrial complex I activity [77].

Epidemiological studies also suggest an involvement of heavy metals in the etiology of PD [78]. Several lines of evidence indicate that iron ions play an important role in PD pathogenesis. The neurons that are most severely affected in PD are located in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus. These brain areas are enriched with neuromelanin that sequesters reactive metals, mainly iron (Fe3+). In PD patients, a correlation between increased iron levels and severity of neuropathological changes has been observed [79]. Significantly, high levels of Fe3+ have been found in LBs [80] and recent evidence suggests that an increase in iron levels is an early event in patients at risk for developing PD and precedes loss of dopaminergic neurons [81–83]. Interestingly, iron chelators show neuroprotective activity against proteasome inhibitor-induced, MPTP-induced, and 6-hydroxydopamine-induced nigral degeneration [84–86]. Additionally, it has been suggested that iron can induce the formation of intracellular αsyn aggregates [87–89], accelerate amyloid formation of αsyn, and trigger the generation of oligomeric αsyn forms in vitro [90]. Most recently, iron has also been found to induce pore-forming αsyn oligomers in vitro [91]. Taken together, these findings implicate iron ions in the generation of αsyn aggregates and in disease progression in PD. However, the underlying molecular events have not been elucidated so far.

Reactive oxygen species and toxic quinone species are also produced by dopamine through autoxidation and enzyme catalyzed reactions. These dopamine oxidative metabolites are accumulated in aging and subsequently result in impairment of the functions of dopaminergic neurons [92]. Interestingly, a number of in vitro studies have shown that dopamine can modulate the aggregation of αsyn by inhibiting the formation of or disaggregating amyloid fibrils [93–95]. Recent evidence suggests that dopamine can induce a conformational change in αsyn, which can be prevented by blocking dopamine transport into the cell. Dopamine-induced conformational changes in αsyn are also associated with alterations in oligomeric αsyn species [95]. Together, these results point to a direct effect of dopamine on the conformation of αsyn in neurons, which may contribute to the increased vulnerability of dopamingeric neurons in PD.

If enhanced oxidative stress alters the oligomeric profile of αsyn (Fig. 1) then the properties of antioxidant reagents may make them therapeutically useful. Antioxidants such as vitamin E and coenzyme Q10 are often recommended as nutritional supplements for patients in the early stages of neurodegenerative disorders such as PD and Alzheimer’s disease and curcumin was recently demonstrated to inhibit aggregation of αsyn in vitro [96].

Chaperone-Based Therapies that Target αsyn

Molecular chaperones are a general class of proteins that can help prevent protein misfolding and/or aggregation or direct proteins towards degradation, and thus help maintain normal protein structure and function. Studies have demonstrated that molecular chaperones interact with misfolded 3syn [97, 98]. The hypothesis that molecular chaperones interact with 3syn has a strong parallel in studies of trinucleotide repeat diseases [99]. In in vitro models, transgenic mouse models, and Drosophila models, overexpression of Hsp70 provides protection against aggregation and/or toxicity of multiple types of polyglutamine aggregates and polyalanine aggregates [100–106].

HSPs are prominent in LBs, and are effective in preventing 3syn aggregation in vitro [27, 28, 97]. Thus Hsp70 and related co-chaperones may be important modifiers of 3syn misfolding (Fig. 1). Overexpression of Hsp70 and related molecules can prevent 3syn aggregates from forming in vitro [27], is protective against the toxic effects of 3syn expression in culture [97], and diminishes the high molecular weight smear of 3syn found in Masliah line D transgenic αsyn mice [97]. Most recently, Hsp70, Hsp40 and Hsp27 were all found to be upregulated in substantia nigra following targeted viral vector-mediated overexpression of αsyn in mice [13].

Pharmacological manipulation of the Hsp system with the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin (GA) upregulates Hsp70 and protects against αsyn toxicity in mammalian cell culture [107]. Data in the fly model also indicate that overexpression of the molecular chaperone Hsp70 protects against 3syn-induced degeneration [38, 108], and that GA leads to neuroprotection in the fly [109]. The protective effect of GA occurred in parallel with a decrease in αsyn aggregation in culture, whereas it correlated with an increase in detergent resistant, presumably nontoxic αsyn species in the brains of transgenic flies. GA also protects against dopaminergic neurotoxicity in MPTP-treated mice [110]. The data from these studies support a model in which Hsp90 inhibitors inhibit the formation of toxic protein aggregates by upregulating Hsp70. Taken together, molecular chaperones may represent a promising therapeutic target for synucleinopathies and other neurodegenerative diseases where protein misfolding is central to their pathogenesis.

A number of small molecule inhibitors of Hsp90 have been studied in models of PD and other neurodegenerative diseases. Hsp90 is part of a complex that negatively regulates the activity of the transcription factor, heat shock factor-1 (HSF-1). Inhibition of Hsp90 chaperone function, by reducing its ATPase activity, results in activation of HSF-1 and subsequent increase in expression of protective stress-induced HSPs such as Hsp70 [111, 112]. As mentioned above, the benzoquinone ansamycin antibiotic GA is a naturally occurring Hsp90 inhibitor which binds to an ATP site on Hsp90 and blocks its interaction with HSF-1, leading to enhanced Hsp70 expression. However, GA has poor aqueous solubility, does not cross the blood-brain barrier, and is associated with significant liver toxicity. To overcome these properties which limit its clinical use, numerous GA analogues have been designed including 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG, or tanespimycin) and 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxy-geldanamycin (alvespimycin). These analogs are blood-brain barrier permeable and are much less toxic than GA. They also have higher affinity for Hsp90 than GA. 17-AAG upregulates Hsp70 expression while reducing αsyn protein levels and αsyn-mediated toxicity in a cell-based system [51]. 17-AAG is also neuroprotective in preclinical studies of Huntington’s disease and spinocerebellar ataxia [112, 113]. Currently, 17-AAG is in phase II trials as an anti-tumour compound [114, 115]. However, the clinical utility of 17-AAG and its analog 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxy-geldanamycin (17-DMAG) may be limited because, while much less toxic than GA, they have caused varying degrees of hepatotoxicity in earlier cancer trials. In addition, they have limited oral availability and have been difficult to formulate [116, 117].

A novel class of synthetic small molecule Hsp90 inhibitors which are unrelated in structure and exhibit unique activities relative to GA and its derivatives is SNX-2112 (4-[6,6-dimethyl-4-oxo-3-(trifluoromethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-indazol-1-yl]-2-[(trans-4-hydroxycyclohexyl)amino]benzamide) and its analogues [118, 119]. SNX-2112 was identified in a compound library screen for scaffolds that selectively bind to the ATP pocket of Hsp90. It is orally available and crosses the blood-brain barrier. Recent in vivo pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies demonstrated that SNX-0723, another member of this drug class, also has good brain absorption and excellent oral bioavailability [51]. Furthermore, a group of these novel Hsp90 inhibitors can decrease αsyn oligomerization in vitro and rescue αsyn-induced toxicity [51], supporting further investigation in vivo to determine if Hsp90 inhibition can rescue 3syn-mediated cell death in animal models. With the first phase I clinical trial of SNX-5422, the pro-drug of SNX-2112 which is being developed for cancer therapy [120], the safety and tolerability of these drugs in human subjects is beginning to be assessed.

Other drugs that upregulate Hsp70 and therefore may be candidates for study in PD include radicicol, a naturally occurring antifungal that is structurally unrelated to GA, and its more stable oxime derivatives. Like GA, radicicol and its derivatives are Hsp90 inhibitors but they have up to 50-fold greater affinity for Hsp90 than GA. However, further drug development of radicicol would be required as it has limited oral bioavailability and blood-brain barrier permeability [116, 120]. A number of other synthetic small molecule inhibitors of Hsp90 are currently being studied in clinical trials for cancer and may be potentially useful in PD including IPI-504 (or retaspimycin), which is a GA derivative [121], and STA-9090, which is structurally unrelated to GA [122].

Arimoclomol is an orally administered drug that upregulates expression of Hsp70 not by inhibiting Hsp90 but by activating HSF-1 [123, 124]. It has been studied in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a progressive neurodegene-rative motor neuron disease, resulting in upregulation of Hsp70 with a decrease in the number of protein aggregates in the spinal cord [125]. Also, there was a significant reduction in the degeneration of motor neurons [126]. In phase I and IIa clinical trials, arimoclomol has demonstrated adequate safety and tolerability [124, 127]. Currently, it is being tested in phase II clinical trials for ALS.

Gene therapy strategies to modulate molecular chaperones

In addition to small molecule-based therapies, there is potential for development of large therapeutic molecules for the treatment of PD. The use of proteins, peptides, and nucleic acid therapeutics has been limited by poor stability in vivo and lack of cellular uptake. However, new advances in recombinant viral vector technology have resulted in feasible gene therapy applications for delivery of large therapeutic molecules. Gene therapy may provide strategies to upregulate the expression and/or activity of neuroprotective chaperones in neurons which are vulnerable to neurodegeneration in PD. Preclinical studies in animal models of PD have provided evidence for the potential of viral-mediated Hsp70 expression. One study using the MPTP mouse model demonstrated that Hsp70 gene transfer to striatal dopaminergic neurons by a recombinant adeno-associated virus could protect against MPTP-induced dopaminergic cell death and the associated decline in striatal dopamine levels [128]. Another study using a rat model of PD showed that adeno-associated virus vector-mediated overexpression of Hsp70, but not Hsp40, protected against dopaminergic neurodegeneration [129].

Recombinant viral vector technology has also been used to investigate neuroprotection by exogenous expression of proteins that can upregulate Hsp70 function. Hsp104 is a molecular chaperone in the AAA+ family of ATPases that can disaggregate large protein aggregates and rescue proteins trapped within these structures [130]. Hsp104 is expressed in fungi, plants, and bacteria but not in mammals. Nevertheless, Hsp104 can synergize with the mammalian Hsp70 chaperone system to act as a hybrid chaperone system which rescues trapped and aggregated proteins in human cells [130]. Expression of Hsp104 using a lentiviral vector in a rat model of PD reduced the formation of phosphorylated 3syn inclusions and prevented nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurodegene-ration induced by mutant A30P 3syn [132].

Another strategy to enhance Hsp70 chaperone function is to use gene silencing to inhibit the expression of negative regulators of Hsp70. RNA interference (RNAi) has emerged as a possible method to reduce target gene expression in brain. Short RNA molecules, such as small interfering RNA and short hairpin RNA can be targeted to specific brain regions by stereotactic injection of recombinant viral vectors. Although RNAi has not yet been well studied in models of dopaminergic neurodegeneration, it can theoretically be applied to PD [133]. There is evidence for the use of RNAi to improve the motor and neuropathological findings in a mouse model of SCA1, supporting its possible utility for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Enhancing αsyn Aggregation as a Therapeutic Strategy

It has been previously demonstrated that a novel compound, B2 (5-[4-(4-chlorobenzoyl)-1-piperazinyl]-8-nitroqunoline), can reduce αsyn-induced toxicity in a cell culture model while increasing inclusion size [39], suggesting that the discovery of compounds that promote inclusion formation may be an important therapeutic strategy. Furthermore, novel sirtuin 2 inhibitors AGK2 and AK-1 were found to rescue αsyn-induced toxicity while increasing macroscopic αsyn aggregates in size [134]. It is possible that B2 and the sirtuin 2 inhibitors are shifting the equilibrium from toxic oligomeric αsyn species towards less toxic or innocuous fibrillar αsyn species thus providing a novel therapeutic intervention strategy - making aggregates bigger, not smaller. Other strategies to shift the equilibrium of αsyn oligomeric species towards fibrillar aggregates could include coexpression of synphilin-1, which has been previously demonstrated to facilitate aggregate formation [135], and modifications to the C-terminal region of αsyn such as truncations, which have also been demonstrated to induce aggregation [135, 136].

IS EXTRACELLULAR αSYN A TARGET FOR DRUG THERAPIES?

Because αsyn inclusion body pathology associated with PD occurs in a hierarchical distribution with its epicenter in the brainstem, then extends to the mesolimbic cortex and associated areas, Braak et al. [137] have suggested that αsyn pathology spreads gradually throughout the neuraxis as PD progresses. However, as yet, the underlying mechanisms of disease progression in PD remain to be determined. Recent studies showing that grafted healthy neurons gradually develop the same pathology as the host neurons in PD brains [138, 139] suggest that the pathology arises as a consequence of factors inherent to the PD brain and aging of transplanted cells promotes the propagation of αsyn aggregation from host to graft. The presence of LBs in neurons that were transplanted years previously, but not in recently transplanted neurons have highlighted the possibility αsyn is released from neurons to the extracellular space and is taken up in other cells. The potential release of αsyn into the extracellular space would also be consistent with the fact that measurable quantities of αsyn are detected in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma [42, 140]. In vitro experiments have shown that fibrillar and oligomeric forms of αsyn can be taken up from the extracellular space by neurons, possibly through an endocytic pathway [141] or via an, as yet, undetermined route. Furthermore, αsyn has been reported to be taken up through a RAB5A-dependent endocytosis and form intracytoplasmic inclusions in cultured neurons [142].

With the appearance of aggregated αsyn in naïve transplanted embryonic stem cells in PD brains [138, 139] the possibility of neuron to neuron transmission of misfolded αsyn in PD has been highlighted. Recombinant αsyn oligomers are taken up by neurons in culture and trigger cell death [47, 143]. Furthermore, Desplats et al. [144] recently demonstrated that αsyn can be directly transmitted from neuronal cells overexpressing αsyn to transplanted embryonic stem cells both in tissue culture and in transgenic animals, supporting the idea that a prion-like mechanism could be responsible for the host-to-graft transfer of PD pathology [145]. These data raise the possibility that a specific conformation of αsyn is transmitted from host cells that promotes aggregation of αsyn and triggers toxicity in adjacent neurons. Understanding the sequence of events in the pathological processes underlying the formation and toxicity of αsyn oligomers inside and ouside neurons in PD will be crucial to the development of new therapeutics. However, whether extracellular αsyn represents a new target for therapeutic strategies to halt PD progression has to be determined.

ANTIBODY MEDIATED THERAPIES

Recent studies in a number of transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease have shown that both active immunization with amyloid-beta (Aβ) antibodies or passive transfer of anti- Aβ antibodies are effective in the prevention of Aβ deposition and the clearance of already existing Aβ plaques [146–152]. Moreover, both active and passive immunization approaches prevented and improved, or even reversed, memory deficits in mouse models [153–156]. An amelioration of tau pathology has also been reported following anti- Aβ immunization in several mouse models containing amyloid plaques and neuronal tau aggregates [157–159].

In human trials, post-mortem studies of brains from participants in an Alzheimer’s disease immunization trial also revealed a significant decrease in amyloid pathology [160–164]. Interestingly, as in some earlier animal immunization studies, a recent human study has shown that clearance of amyloid plaques by active anti- Aβ immunization can promote structural changes in neurites and decrease the hyperphosphorylation of tau [165].

Approaches based on antibody-mediated therapies may also have a much wider application in the treatment of neurodegenerative disease. A vaccination approach in a transgenic model of prion disorder has been shown to be effective at reducing the accumulation of prion protein in mice [166]. Furthermore, vaccinations of mice in tauopathy and huntington’s disease models have been reported to ameliorate pathology [167–169]. Interestingly, vaccination with human αsyn in human αsyn transgenic mice also showed a decreased accumulation of aggregated αsyn in neuronal cell bodies and synapses which was associated with reduced neurodegeneration [170]. This effect was most pronounced in mice that produced relatively high-affinity antibodies, indicating a strong correlation between high-affinity antibodies against αsyn and amelioration of αsyn pathology. Furthermore, antibodies produced by immunized mice recognized abnormal αsyn associated with the neuronal membrane and promoted the degradation of αsyn aggregates via proposed lysosomal pathways [170]. Because emerging evidence from several laboratories indicates that 3syn may transfer from one neuron to another [144, 171, 172], both in cell culture models and in vivo, the study by Masliah and colleagues may now be viewed from a different perspective. The potential mechanism of antibody-αsyn recognition and degradation via the lysosomal pathway must now take into account the possibility of antibody-αsyn recognition occurring in the extracellular space (Fig. 1). Considering that 3syn aggregates appear to spread throughout the brains of people with PD in a gradual and stereotypic fashion, as described by Braak and coworkers [137], it is tempting to propose that intercellular 3syn transfer underlies the progression of the neuropathological changes. If trans-cellular propagation of misfolded protein occurs, antibody-based therapies could also be expanded to target protein aggregates that are generated inside a cell and released into the extracellular space. Thus antibody-based therapies for synucleinopathies may target the propagation of αsyn pathology.

TARGETING DEGRADATION PATHWAYS

Impaired proteasomal degradation of 3syn leads to enhanced aggregation and toxicity both in vitro and in vivo after proteasome inhibition [135, 173–175]. Additional support for this idea comes from consideration of another gene implicated in PD: Mutations in parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, underlie juvenile onset PD [176], and a mutation in ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase is a rare cause of inherited PD [177]. HSPs are important in both refolding activities and in directing proteins towards proteasomal degradation [178–180]. The role of HSPs in either refolding or ubiquitination of proteins is partly dependent on interacting proteins. CHIP (carboxyl terminus Hsp70 interacting protein), a tetratricopeptide repeat protein, negatively regulates Hsp70 and Hsp90 mediated refolding of proteins and instead directs proteins towards degradation [181, 182]. CHIP inhibits the ATPase activity of Hsp70 and can also bind to an Hsp90 complex, causing the release of p23 (a necessary co-chaperone for refolding) and, likely at least in part through an interaction with Bag-1, directs the misfolded protein towards degradation. CHIP has been shown to be a U-box containing ubiquitin E3 ligase, and is responsible for ubiquitinating misfolded mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator [183]. CHIP also interacts directly with parkin [184], providing another level of regulation of the cell decision towards refolding or proteasomal degradation, and a direct link to PD phenomenon. CHIP immunoreactivity has been found in LBs in human tissue and an interaction of CHIP with 3syn leads to modified aggregation and increased degradation via both the proteasome and lysosome [98]. Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate that CHIP preferentially targets high molecular weight soluble oligomeric αsyn for degradation in an Hsp70-dependent manner [185]. Specifically, CHIP selectively reduced 3syn oligomerization and toxicity in a TPR domain-dependent, U-box independent manner by specifically degrading toxic 3syn oligomers. This suggests that CHIP preferentially recognizes and mediates degradation of toxic, oligomeric forms of 3syn, thus making CHIP an extremely interesting therapeutic target. Moreover, these data support the hypothesis that pathways involved in handling misfolded proteins play a role in PD and related diseases.

Several studies have investigated a link between αsyn and the proteasome and have found that mutant αsyn can reduce the net proteasomal activity in living cells [186–189]. Importantly, recent studies have suggested that soluble oligomeric intermediates of αsyn may specifically impair the function of the 26S proteasome [190, 191]. However, the mechanisms and the particular species involved remain elusive.

Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is a selective pathway for the degradation of cytosolic proteins in lysosomes (reviewed in [192]). CMA declines with age because of a decrease in the levels of lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP) type 2A, a lysosomal receptor for this pathway [193]. The substrate proteins are recognized by a chaperone-cochaperone complex which delivers them to the lysosomal membrane [194]. Here they bind to LAMP2A [195], and after unfolding, the substrate proteins are translocated across the lysosomal membrane assisted by a lysosomal- resident chaperone, before being degraded in the hydrolase-rich lumen [192]. CMA is unique in that it selectively degrades cytosolic proteins which contain a CMA-targeting motif.

Both cytosolic and lysosomal chaperones are required for completion of CMA. The cytosolic chaperone, Hsc70, recognizes and binds to the targeting motif in the substrates. The interaction between Hsc70 and the substrate is modulated by other cytosolic co-chaperones including Hsp90, Hsp40, Hsp70 interacting protein, Hsp70/Hsp90 organizing protein, and bcl-2 associated -1 [196].

CMA has been predicted to play a role in PD and related synucleinopathies for several reasons. First, wild-type αsyn is efficiently degraded in lysosomes by CMA, but the pathogenic αsyn mutations, A53T and A30P are poorly degraded by CMA despite a high affinity for the CMA receptor [197] and mutant αsyn can block the lysosomal uptake and degradation of other CMA substrates. Furthermore, CMA blockage results in a compensatory activation of macroautophagy which cannot maintain normal rates of degradation under these conditions [197]. Impaired CMA of pathogenic αsyn may favor toxic gains-of-functions by contributing to its aggregation. Second, mutant αsyn also inhibits degradation of other long-lived cytosolic proteins by CMA, which may further contribute to cellular stress, perhaps causing the cell to rely on alternate degradation pathways or to aggregate damaged proteins [198]. Third, recent studies have demonstrated that dopamine-modified αsyn is poorly degraded by CMA and also blocks degradation of other substrates by this pathway [199]. Therefore, dopamine-induced inhibition of autophagy could explain the selective degeneration of PD dopaminergic neurons.

Targeting therapeutics to enhance CMA may prove beneficial for PD therapies. Indeed trehalose, a disaccharide and novel mammalian target of rapamycin-independent autophagy enhancer, was found to enhance the clearance of the autophagy substrates mutant huntingtin and mutant αsyn [200]. Furthermore, trehalose and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor rapamycin together exerted an additive effect on the clearance of these proteins due to increased autophagic activity and protected cells against pro-apoptotic insults. The dual protective properties of trehalose (chemical chaperone and inducer of autophagy) combined with rapamycin may be relevant to the treatment of PD where mutant proteins are autophagy substrates [197].

CONCLUSIONS

A growing body of evidence implicates non-fibrillar, soluble species of αsyn as a critical player in PD pathogenesis and disease progression. As such interventions that target oligomeric forms of αsyn by inducing degradation of toxic, misfolded αsyn or by altering the equilibrium of αsyn species in favor of a less toxic species are important therapeutic strategies under consideration. Building on the body’s own defense mechanisms for handling misfolded and toxic proteins such as cellular degradation pathways and chaperone-mediated pathways may hold promise for therapeutic development, however a major question that needs to be addressed is where αsyn exerts its toxic effect and where it should be targeted. Several recent studies have raised the possibility that αsyn is secreted from cells and undergoes trans-synaptic transmission, seeding subsequent aggregation and toxicity in neighboring cells. It remains to be determined if this occurs only under situations of cellular stress and duress such as in the disease process or whether this is part of the normal biological pathway for αsyn. Ultimately, a full understanding of αsyn biology and what goes awry in the disease process will lead to the development of better therapeutics that ameliorate or halt PD progression.

Acknowledgments

PJM is supported by NIH NS063963 and research grants from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Disease research.

ABBREVIATIONS

- αsyn

Alpha-synuclein

- Aβ

Amyloid-beta

- 17-AAG

17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin

- CHIP

C-terminal Hsp70 interacting protein

- CMA

Chaperone mediated autophagy

- GA

Geldanamycin

- HSF-1

Heat shock transcriptional factor-1

- Hsp

Heat shock protein

- LBs

Lewy bodies

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2-3,6-tetrahyrdopyridine

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- RNAi

RNA interference

- SNX-2112

4-[6,6-dimethyl-4-oxo-3-(trifluoromethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-indazol-1-yl]-2-[(trans-4-hydroxy-cyclohexyl)amino]benzamide

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Krüger R, Kuhn W, Müller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, Kosel S, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Schols L, Riess O. Ala30Pro mutation in the gene encoding a-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 1998;18:106–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Idle SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, Stenroos ES, Chandrasekharappa S, Athanassiadou A, Papaetropoulos T, Johnson WG, Lazzarini AM, Duvoisin RC, Iorio GD, Golbe LI, Nussbaum RL. Mutation in the a-Synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zarranz JJ, Alegre J, Gomez-Esteban JC, Lezcano E, Ros R, Ampuero I, Vidal L, Hoenicka J, Rodriguez O, Atares B, Llorens V, Gomez Tortosa E, del Ser T, Munoz DG, de Yebenes JG. The new mutation, E46K, of alpha-synuclein causes Parkinson and Lewy body dementia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(2):164–173. doi: 10.1002/ana.10795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. a-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6469–6473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irizarry MC, Growdon W, Gomez-Isla T, Newell K, George JM, Clayton DF, Hyman BT. Nigral and cortical lewy bodies and dystrophic nigral neurites in Parkinson’s disease and cortical lewy body disease contain a-synuclein immunoreactivity. J Neuropath Exp Neurol. 1998;57:334–337. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrer M, Kachergus J, Forno L, Lincoln S, Wang DS, Hulihan M, Maraganore D, Gwinn-Hardy K, Wszolek Z, Dickson D, Langston JW. Comparison of kindreds with parkinsonism and alpha-synuclein genomic multiplications. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(2):174–179. doi: 10.1002/ana.10846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, Lincoln S, Crawley A, Hanson M, Maraganore D, Adler C, Cookson MR, Muenter M, Baptista M, Miller D, Blancato J, Hardy J, Gwinn-Hardy K. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302(5646):841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, Takeda A, Sagara Y, Sisk A, Mucke L. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in a-synuclein mice: Implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2000;287:1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giasson BI, Duda JE, Quinn SM, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Neuronal alpha-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2002;34(4):521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo Bianco C, Ridet JL, Schneider BL, Deglon N, Aebischer P. alpha -Synucleinopathy and selective dopaminergic neuron loss in a rat lentiviral-based model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(16):10813–10818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152339799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Burger C, Lundberg C, Johansen TE, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ, Bjorklund A. Parkinson-like neurodegeneration induced by targeted overexpression of alpha-synuclein in the nigrostriatal system. J Neurosci. 2002;22(7):2780–2791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02780.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein RL, King MA, Hamby ME, Meyer EM. Dopaminergic cell loss induced by human A30P alpha-synuclein gene transfer to the rat substantia nigra. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13(5):605–612. doi: 10.1089/10430340252837206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St Martin JL, Klucken J, Outeiro TF, Nguyen P, Keller-McGandy C, Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Grammatopoulos TN, Standaert DG, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Dopaminergic neuron loss and up-regulation of chaperone protein mRNA induced by targeted over-expression of alpha-synuclein in mouse substantia nigra. J Neurochem. 2007;100(6):1449–1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauwers E, Debyser Z, Van Dorpe J, De Strooper B, Nuttin B, Baekelandt V. Neuropathology and neurodegeneration in rodent brain induced by lentiviral vector-mediated overexpression of alpha-synuclein. Brain Pathol. 2003;13(3):364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feany MB, Bender WW. A Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2000;404:394–398. doi: 10.1038/35006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spillantini MG, Goedert M. The alpha-synucleinopathies: Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;920:16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinreb PH, Zhen W, Poon AW, Conway KA, PT, Lansbury J. NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer's disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry. 1996;35(43):13709–13715. doi: 10.1021/bi961799n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto M, Hsu LJ, Sisk A, Xia Y, Takeda A, Sundsmo M, Masliah E. Human recombinant NACP/alpha-synuclein is aggregated and fibrillated in vitro: relevance for Lewy body disease. Brain Res. 1998;799(2):301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uversky VN, Cooper ME, Bower KS, Li J, Fink AL. Accelerated alpha-synuclein fibrillation in crowded milieu. FEBS Lett. 2002;515(1–3):99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez-Tortosa E, Newell K, Irizarry MC, Sanders JL, Hyman BT. alpha-Synuclein immunoreactivity in dementia with Lewy bodies: morphological staging and comparison with ubiquitin immunostaining. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2000;99(4):352–357. doi: 10.1007/s004010051135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388(6645):839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serpell LC, Berriman J, Jakes R, Goedert M, Crowther RA. Fiber diffraction of synthetic alpha-synuclein filaments shows amyloid-like cross-beta conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(9):4897–4902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conway KA, Harper JD, PT, Lansbury J. Fibrils formed in vitro from a-synuclein and two mutant forms linked to Parkinson’s disease are typical amyloid. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2552–2563. doi: 10.1021/bi991447r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelender S, Kaminsky Z, Guo X, Sharp AH, Amaravi RK, Kleiderlein JJ, Margolis RL, Troncoso JC, Lanahan AA, Worley PF, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ross CA. Synphilin-1 associates with a-synuclein and promotes the formation of cytosolic inclusions. Nat Genet. 1999;22:110–114. doi: 10.1038/8820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakabayashi K, Engelender S, Yoshimoto M, Ross CA, Takahashi H. Synphilin-1 is present in Lewy bodies in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(4):521–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuzuhara S, Mori H, Izumiyama N, Yoshimura M, Ihara Y. Lewy bodies are ubiquitinated. A light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical study. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1988;75(4):345–353. doi: 10.1007/BF00687787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLean PJ, Kawamata H, Shariff S, Hewett J, Sharma N, Ueda K, Breakefield XO, Hyman BT. TorsinA and heat shock proteins act as molecular chaperones: suppression of alpha-synuclein aggregation. J Neurochem. 2002;83(4):846–854. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Outeiro TF, Klucken J, Strathearn KE, Liu F, Nguyen P, Rochet JC, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Small heat shock proteins protect against alpha-synuclein-induced toxicity and aggregation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351(3):631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma N, McLean PJ, Kawamata H, Hyman BT. Alpha-synuclein has an altered conformation and shows a tight intermolecular interaction with ubiquitin in Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2001;102(4):329–334. doi: 10.1007/s004010100369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klucken J, Outeiro TF, Nguyen P, McLean PJ, Hyman BT. Detection of novel intracellular alpha-synuclein oligomeric species by fluorescence lifetime imaging. FASEB J. 2006;20(12):2050–2057. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5422com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharon R, Bar-Joseph I, Frosch MP, Walsh DM, Hamilton JA, Selkoe DJ. The formation of highly soluble oligomers of alpha-synuclein is regulated by fatty acids and enhanced in Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2003;37(4):583–595. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conway KA, Lee SJ, Rochet JC, Ding TT, Williamson RE, PT, Lansbury J. Acceleration of oligomerization, not fibrillization, is a shared property of both a-synuclein mutations limked to early-onset Parkinson's disease: Implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(2):571–576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg MS, Lansbury PT., Jr Is there a cause-and-effect relationship between alpha-synuclein fibrillization Parkinson’s disease? Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(7):E115–E119. doi: 10.1038/35017124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gosavi N, Lee HJ, Lee JS, Patel S, Lee SJ. Golgi fragmentation occurs in the cells with prefibrillar alpha-synuclein aggregates and precedes the formation of fibrillar inclusion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(50):48984–48992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300(5618):486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishnan S, Chi EY, Wood SJ, Kendrick BS, Li C, Garzon-Rodriguez W, Wypych J, Randolph TW, Narhi LO, Biere AL, Citron M, Carpenter JF. Oxidative dimer formation is the critical rate-limiting step for Parkinson’s disease alpha-synuclein fibrillogenesis. Biochemistry. 2003;42(3):829–837. doi: 10.1021/bi026528t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uversky VN, Li J, Fink AL. Evidence for a partially folded intermediate in alpha-synuclein fibril formation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(14):10737–10744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Auluck PK, Chan HYE, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY, Bonini NM. Chaperone suppression of a-synuclein toxicity in a Drosophila model for Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2002;295:865–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1067389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bodner RA, Outeiro TF, Altmann S, Maxwell MM, Cho SH, Hyman BT, McLean PJ, Young AB, Housman DE, Kazantsev AG. Pharmacological promotion of inclusion formation: a therapeutic approach for Huntington’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(11):4246–4251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511256103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bucciantini M, Calloni G, Chiti F, Formigli L, Nosi D, Dobson CM, Stefani M. Prefibrillar amyloid protein aggregates share common features of cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(30):31374–31382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bucciantini M, Giannoni E, Chiti F, Baroni F, Formigli L, Zurdo J, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM, Stefani M. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 2002;416(6880):507–511. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Agnaf OM, Salem SA, Paleologou KE, Curran MD, Gibson MJ, Court JA, Schlossmacher MG, Allsop D. Detection of oligomeric forms of alpha-synuclein protein in human plasma as a potential biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 2006;20(3):419–425. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1449com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kayed R, Sokolov Y, Edmonds B, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Hall JE, Glabe CG. Permeabilization of lipid bilayers is a common conformation-dependent activity of soluble amyloid oligomers in protein misfolding diseases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(45):46363–46366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park JY, Lansbury PT., Jr Beta-synuclein inhibits formation of alpha-synuclein protofibrils: a possible therapeutic strategy against Parkinson's disease. Biochemistry. 2003;42(13):3696–3700. doi: 10.1021/bi020604a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wood SJ, Wypych J, Steavenson S, Louis JC, Citron M, Biere AL. a-Synuclein fibrillogenesis is nucleation-dependent: implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19509–19512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dedmon MM, Christodoulou J, Wilson MR, Dobson CM. Heat shock protein 70 inhibits alpha-synuclein fibril formation via preferential binding to prefibrillar species. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(15):14733–14740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danzer KM, Haasen D, Karow AR, Moussaud S, Habeck M, Giese A, Kretzschmar H, Hengerer B, Kostka M. Different Species of {alpha}-Synuclein Oligomers Induce Calcium Influx and Seeding. J Neurosci. 2007;27(34):9220–9232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2617-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong DP, Han S, Fink AL, Uversky VN. Characterization of the non-fibrillar alpha-synuclein oligomers. Protein Pept Lett. 18(3):230–240. doi: 10.2174/092986611794578332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lashuel HA, Grillo-Bosch D. In vitro preparation of prefibrillar intermediates of amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;299:19–33. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-874-9:019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Outeiro TF, Putcha P, Tetzlaff JE, Spoelgen R, Koker M, Carvalho F, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Formation of toxic oligomeric alpha-synuclein species in living cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(4):e1867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Putcha P, Danzer KM, Kranich LR, Scott A, Silinski M, Mabbett S, Hicks CD, Veal JM, Steed PM, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Brain-permeable small-molecule inhibitors of Hsp90 prevent alpha-synuclein oligomer formation and rescue alpha-synuclein-induced toxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;332(3):849–857. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.158436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsika E, Moysidou M, Guo J, Cushman M, Gannon P, Sandaltzopoulos R, Giasson BI, Krainc D, Ischiropoulos H, Mazzulli JR. Distinct region-specific alpha-synuclein oligomers in A53T transgenic mice: implications for neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 30(9):3409–3418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4977-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hinault MP, Cuendet AF, Mattoo RU, Mensi M, Dietler G, Lashuel HA, Goloubinoff P. Stable alpha-synuclein oligomers strongly inhibit chaperone activity of the Hsp70 system by weak interactions with J-domain co-chaperones. J Biol Chem. 285(49):38173–38182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huls S, Hogen T, Vassallo N, Danzer KM, Hengerer B, Giese A, Herms J. AMPA-receptor-mediated excitatory synaptic transmission is enhanced by iron-induced alpha-synuclein oligomers. J Neurochem. 117(5):868–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Esteves AR, Arduino DM, Swerdlow RH, Oliveira CR, Cardoso SM. Dysfunctional mitochondria uphold calpain activation: contribution to Parkinson’s disease pathology. Neurobiol Dis. 37(3):723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng LR, Federoff HJ, Vicini S, Maguire-Zeiss KA. Alpha-synuclein mediates alterations in membrane conductance: a potential role for alpha-synuclein oligomers in cell vulnerability. Eur J Neurosci. 32(1):10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tompa P. Structural disorder in amyloid fibrils: its implication in dynamic interactions of proteins. FEBS J. 2009;276(19):5406–5415. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Croke RL, Patil SM, Quevreaux J, Kendall DA, Alexandrescu AT. NMR determination of pKa values in alpha-synuclein. Protein Sci. 20(2):256–269. doi: 10.1002/pro.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rivers RC, Kumita JR, Tartaglia GG, Dedmon MM, Pawar A, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Christodoulou J. Molecular determinants of the aggregation behavior of alpha- and beta-synuclein. Protein Sci. 2008;17(5):887–898. doi: 10.1110/ps.073181508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu KP, Weinstock DS, Narayanan C, Levy RM, Baum J. Structural reorganization of alpha-synuclein at low pH observed by NMR and REMD simulations. J Mol Biol. 2009;391(4):784–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hashimoto M, Hsu LJ, Xia Y, Takeda A, Sisk A, Sundsmo M, Masliah E. Oxidative stess induces amyloid-like aggregate formation of NACP/a-synuclein in vitro. NeuroReport. 1999;10:717–721. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199903170-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vila M, Vukosavic S, Jackson-Lewis V, Neystat M, Jakowec M, Przedborski S. Alpha-synuclein up-regulation in substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons following administration of the parkinsonian toxin MPTP. J Neurochem. 2000;74(2):721–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nicklas WJ, Vyas I, Heikkila RE. Inhibition of NADH-linked oxidation in brain mitochondria by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine, a metabolite of the neurotoxin, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine. Life Sci. 1985;36(26):2503–2508. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schapira AH, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Jenner P, Clark JB, Marsden CD. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1989;1(8649):1269. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ho PW, Chan DY, Kwok KH, Chu AC, Ho JW, Kung MH, Ramsden DB, Ho SL. Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion modulates expression of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins 2, 4, and 5 in catecholaminergic (SK-N-SH) cells. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81(2):261–268. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Storch A, Ludolph AC, Schwarz J. Dopamine transporter: involvement in selective dopaminergic neurotoxicity and degeneration. J Neural Transm. 2004;111(10–11):1267–1286. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kalivendi SV, Cunningham S, Kotamraju S, Joseph J, Hillard CJ, Kalyanaraman B. Alpha-synuclein up-regulation and aggregation during MPP+-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells: intermediacy of transferrin receptor iron and hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(15):15240–15247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(12):1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCoy MK, Cookson MR. Mitochondrial Quality Control and Dynamics in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4019. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCoy MK, Cookson MR. DJ-1 regulation of mitochondrial function and autophagy through oxidative stress. Autophagy. 7(5):531–532. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.5.14684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu W, Sun Y, Guo S, Lu B. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial dynamics and function in mammalian hippocampal and dopaminergic neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 20(16):3227–3240. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dauer W, Kholodilov N, Vila M, Trillat AC, Goodchild R, Larsen KE, Staal R, Tieu K, Schmitz Y, Yuan CA, Rocha M, Jackson-Lewis V, Hersch S, Sulzer D, Przedborski S, Burke R, Hen R. Resistance of alpha -synuclein null mice to the parkinsonian neurotoxin MPTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(22):14524–14529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172514599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Song DD, Shults CW, Sisk A, Rockenstein E, Masliah E. Enhanced substantia nigra mitochondrial pathology in human alpha-synuclein transgenic mice after treatment with MPTP. Exp Neurol. 2004;186(2):158–172. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00342-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hsu LJ, Sagara Y, Arroyo A, Rockenstein E, Sisk A, Mallory M, Wong J, Takenouchi T, Hashimoto M, Masliah E. alpha-synuclein promotes mitochondrial deficit and oxidative stress. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(2):401–410. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64553-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li WW, Yang R, Guo JC, Ren HM, Zha XL, Cheng JS, Cai DF. Localization of alpha-synuclein to mitochondria within midbrain of mice. Neuroreport. 2007;18(15):1543–1546. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f03db4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parihar MS, Parihar A, Fujita M, Hashimoto M, Ghafourifar P. Mitochondrial association of alpha-synuclein causes oxidative stress. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(7–8):1272–1284. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7589-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Devi L, Raghavendran V, Prabhu BM, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK. Mitochondrial import and accumulation of alpha-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(14):9089–9100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA, Peterson EL, Kortsha GX, Brown GG, Richardson RJ. Occupational exposures to metals as risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1997;48(3):650–658. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gotz ME, Double K, Gerlach M, Youdim MB, Riederer P. The relevance of iron in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1012:193–208. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gaeta A, Hider RC. The crucial role of metal ions in neurodegeneration: the basis for a promising therapeutic strategy. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146(8):1041–1059. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oakley AE, Collingwood JF, Dobson J, Love G, Perrott HR, Edwardson JA, Elstner M, Morris CM. Individual dopaminergic neurons show raised iron levels in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;68(21):1820–1825. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000262033.01945.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Michaeli S, Oz G, Sorce DJ, Garwood M, Ugurbil K, Majestic S, Tuite P. Assessment of brain iron and neuronal integrity in patients with Parkinson’s disease using novel MRI contrasts. Mov Disord. 2007;22(3):334–340. doi: 10.1002/mds.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berg D. Disturbance of iron metabolism as a contributing factor to SN hyperechogenicity in Parkinson’s disease: implications for idiopathic and monogenetic forms. Neurochem Res. 2007;32(10):1646–1654. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ben-Shachar D, Eshel G, Finberg JP, Youdim MB. The iron chelator desferrioxamine (Desferal) retards 6-hydroxydopamine-induced degeneration of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons. J Neurochem. 1991;56(4):1441–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb11444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaur D, Yantiri F, Rajagopalan S, Kumar J, Mo JQ, Boonplueang R, Viswanath V, Jacobs R, Yang L, Beal MF, DiMonte D, Volitaskis I, Ellerby L, Cherny RA, Bush AI, Andersen JK. Genetic or pharmacological iron chelation prevents MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in vivo: a novel therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2003;37(6):899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang X, Xie W, Qu S, Pan T, Wang X, Le W. Neuroprotection by iron chelator against proteasome inhibitor-induced nigral degeneration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333(2):544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hasegawa T, Matsuzaki M, Takeda A, Kikuchi A, Akita H, Perry G, Smith MA, Itoyama Y. Accelerated alpha-synuclein aggregation after differentiation of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2004;1013(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ostrerova-Golts N, Petrucelli L, Hardy J, Lee JM, Farer M, Wolozin B. The A53T alpha-synuclein mutation increases iron-dependent aggregation and toxicity. J Neurosci. 2000;20(16):6048–6054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06048.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hillmer AS, Putcha P, Levin J, Hogen T, Hyman BT, Kretzschmar H, McLean PJ, Giese A. Converse modulation of toxic alpha-synuclein oligomers in living cells by N′-benzylidene-benzohydrazide derivates and ferric iron. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;391(1):461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Uversky VN, Li J, Fink AL. Metal-triggered structural transformations, aggregation, and fibrillation of human alpha-synuclein. A possible molecular NK between Parkinson’s disease and heavy metal exposure. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(47):44284–44296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kostka M, Hogen T, Danzer KM, Levin J, Habeck M, Wirth A, Wagner R, Glabe CG, Finger S, Heinzelmann U, Garidel P, Duan W, Ross CA, Kretzschmar H, Giese A. Single particle characterization of iron-induced pore-forming alpha-synuclein oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(16):10992–11003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Luo Y, Roth GS. The roles of dopamine oxidative stress and dopamine receptor signaling in aging and age-related neurodegeneration. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2(3):449–460. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li J, Zhu M, Manning-Bog AB, Di Monte DA, Fink AL. Dopamine and L-dopa disaggregate amyloid fibrils: implications for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2004;18(9):962–964. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0770fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Follmer C, Romao L, Einsiedler CM, Porto TC, Lara FA, Moncores M, Weissmuller G, Lashuel HA, Lansbury P, Neto VM, Silva JL, Foguel D. Dopamine affects the stability, hydration, and packing of protofibrils and fibrils of the wild type and variants of alpha-synuclein. Biochemistry. 2007;46(2):472–482. doi: 10.1021/bi061871+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Outeiro TF, Klucken J, Bercury K, Tetzlaff J, Putcha P, Oliveira LM, Quintas A, McLean PJ, Hyman BT. Dopamine-induced conformational changes in alpha-synuclein. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e6906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pandey N, Strider J, Nolan WC, Yan SX, Galvin JE. Curcumin inhibits aggregation of alpha-synuclein. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115(4):479–489. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Klucken J, Shin Y, Masliah E, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Hsp70 Reduces alpha-Synuclein Aggregation and Toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(24):25497–25502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shin Y, Klucken J, Patterson C, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. The co-chaperone carboxyl terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) mediates alpha-synuclein degradation decisions between proteasomal and lysosomal pathways. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(25):23727–23734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sakahira H, Breuer P, Hayer-Hartl MK, Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones as modulators of polyglutamine protein aggregation and toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(Suppl 4):16412–16418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182426899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kobayashi Y, Sobue G. Protective effect of chaperones on polyglutamine diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56(3–4):165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wyttenbach A. Role of heat shock proteins during polyglutamine neurodegeneration: mechanisms and hypothesis. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;23(1–2):69–96. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:1-2:069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chai Y, Koppenhafer SL, Bonini NM, Paulson HL. Analysis of the role of heat shock protein (Hsp) molecular chaperones in polyglutamine disease. J Neurosci. 1999;19(23):10338–10347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10338.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Warrick JM, Chan HY, Gray-Board GL, Chai Y, Paulson HL, Bonini NM. Suppression of polyglutamine-mediated neurodegeneration in Drosophila by the molecular chaperone HSP70. Nat Genet. 1999;23(4):425–428. doi: 10.1038/70532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jana NR, Tanaka M, Wang G, Nukina N. Polyglutamine length-dependent interaction of Hsp40 and Hsp70 family chaperones with truncated N-terminal huntingtin: their role in suppression of aggregation and cellular toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(13):2009–2018. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.13.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Krobitsch S, Lindquist S. Aggregation of huntingtin in yeast varies with the length of the polyglutamine expansion and the expression of chaperone proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(4):1589–1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McLean PJ, Klucken J, Shin Y, Hyman BT. Geldanamycin induces Hsp70 and prevents alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321(3):665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bonini NM. Chaperoning brain degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(Suppl 4):16407–16411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152330499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Auluck PK, Bonini NM. Pharmacological prevention of Parkinson disease in Drosophila. Nat Med. 2002;8(11):1185–1186. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shen HY, He JC, Wang Y, Huang QY, Chen JF. Geldanamycin induces heat shock protein 70 and protects against MPTP-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(48):39962–39969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dickey CA, Eriksen J, Kamal A, Burrows F, Kasibhatla S, Eckman CB, Hutton M, Petrucelli L. Development of a high throughput drug screening assay for the detection of changes in tau levels -- proof of concept with HSP90 inhibitors. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2(2):231–238. doi: 10.2174/1567205053585927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fujikake N, Nagai Y, Popiel HA, Okamoto Y, Yamaguchi M, Toda T. Heat shock transcription factor 1-activating compounds suppress polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration through induction of multiple molecular chaperones. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(38):26188–26197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710521200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Waza M, Adachi H, Katsuno M, Minamiyama M, Tanaka F, Sobue G. Alleviating neurodegeneration by an anticancer agent: an Hsp90 inhibitor (17-AAG) Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1086:21–34. doi: 10.1196/annals.1377.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Heath EI, Gaskins M, Pitot HC, Pili R, Tan W, Marschke R, Liu G, Hillman D, Sarkar F, Sheng S, Erlichman C, Ivy P. A phase II trial of 17-allylamino-17- demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2005;4(2):138–141. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2005.n.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ramanathan RK, Trump DL, Eiseman JL, Belani CP, Agarwala SS, Zuhowski EG, Lan J, Potter DM, Ivy SP, Ramalingam S, Brufsky AM, Wong MK, Tutchko S, Egorin MJ. Phase I pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic study of 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17AAG, NSC 330507): a novel inhibitor of heat shock protein 90, in patients with refractory advanced cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(9):3385–3391. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chiosis G, Tao H. Purine-scaffold Hsp90 inhibitors. IDrugs. 2006;9(11):778–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cysyk RL, Parker RJ, Barchi JJ, Jr, Steeg PS, Hartman NR, Strong JM. Reaction of geldanamycin and C17-substituted analogues with glutathione: product identifications and pharmacological implications. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19(3):376–381. doi: 10.1021/tx050237e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chandarlapaty S, Sawai A, Ye Q, Scott A, Silinski M, Huang K, Fadden P, Partdrige J, Hall S, Steed P, Norton L, Rosen N, Solit DB. SNX2112, a synthetic heat shock protein 90 inhibitor, has potent antitumor activity against HER kinase-dependent cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(1):240–248. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Okawa Y, Hideshima T, Steed P, Vallet S, Hall S, Huang K, Rice J, Barabasz A, Foley B, Ikeda H, Raje N, Kiziltepe T, Yasui H, Enatsu S, Anderson KC. SNX-2112, a selective Hsp90 inhibitor, potently inhibits tumor cell growth, angiogenesis, and osteoclastogenesis in multiple myeloma and other hematologic tumors by abrogating signaling via Akt and ERK. Blood. 2009;113(4):846–855. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Taldone T, Gozman A, Maharaj R, Chiosis G. Targeting Hsp90: small-molecule inhibitors and their clinical development. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(4):370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hanson BE, Vesole DH. Retaspimycin hydrochloride (IPI-504): a novel heat shock protein inhibitor as an anticancer agent. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(9):1375–1383. doi: 10.1517/13543780903158934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lin TY, Bear M, Du Z, Foley KP, Ying W, Barsoum J, London C. The novel HSP90 inhibitor STA-9090 exhibits activity against Kit-dependent and -independent malignant mast cell tumors. Exp Hematol. 2008;36(10):1266–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kalmar B, Greensmith L. Activation of the heat shock response in a primary cellular model of motoneuron neurodegeneration-evidence for neuroprotective and neurotoxic effects. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2009;14(2):319–335. doi: 10.2478/s11658-009-0002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lanka V, Wieland S, Barber J, Cudkowicz M. Arimoclomol: a potential therapy under development for ALS. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(12):1907–1918. doi: 10.1517/13543780903357486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kalmar B, Novoselov S, Gray A, Cheetham ME, Margulis B, Greensmith L. Late stage treatment with arimoclomol delays disease progression and prevents protein aggregation in the SOD1 mouse model of ALS. J Neurochem. 2008;107(2):339–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kieran D, Kalmar B, Dick JR, Riddoch-Contreras J, Burnstock G, Greensmith L. Treatment with arimoclomol, a coinducer of heat shock proteins, delays disease progression in ALS mice. Nat Med. 2004;10(4):402–405. doi: 10.1038/nm1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cudkowicz ME, Shefner JM, Simpson E, Grasso D, Yu H, Zhang H, Shui A, Schoenfeld D, Brown RH, Wieland S, Barber JR. Arimoclomol at dosages up to 300 mg/day is well tolerated and safe in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38(1):837–844. doi: 10.1002/mus.21059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Dong Z, Wolfer DP, Lipp HP, Bueler H. Hsp70 gene transfer by adeno-associated virus inhibits MPTP-induced nigrostriatal degeneration in the mouse model of Parkinson disease. Mol Ther. 2005;11(1):80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Jung AE, Fitzsimons HL, Bland RJ, During MJ, Young D. HSP70 and constitutively active HSF1 mediate protection against CDCrel-1-mediated toxicity. Mol Ther. 2008;16(6):1048–1055. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Glover JR, Lindquist S. Hsp104, Hsp70, and Hsp40: a novel chaperone system that rescues previously aggregated proteins. Cell. 1998;94(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mosser DD, Ho S, Glover JR. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp104 enhances the chaperone capacity of human cells and inhibits heat stress-induced proapoptotic signaling. Biochemistry. 2004;43(25):8107–8115. doi: 10.1021/bi0493766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lo Bianco C, Shorter J, Regulier E, Lashuel H, Iwatsubo T, Lindquist S, Aebischer P. Hsp104 antagonizes alpha-synuclein aggregation and reduces dopaminergic degeneration in a rat model of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(9):3087–3097. doi: 10.1172/JCI35781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Manfredsson FP, Lewin AS, Mandel RJ. RNA knockdown as a potential therapeutic strategy in Parkinson’s disease. Gene Ther. 2006;13(6):517–524. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Outeiro TF, Kontopoulos E, Altman S, Kufareva I, Strathearn KE, Amore AM, Volk CB, Maxwell MM, Rochet JC, McLean PJ, Young AB, Abagyan R, Feany MB, Hyman BT, Kazantsev A. Sirtuin 2 Inhibitors Rescue {alpha}-Synuclein-Mediated Toxicity in Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Science. 2007;317(5837):516–519. doi: 10.1126/science.1143780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.McLean PJ, Kawamata H, Hyman BT. a-Synuclein-enhanced green fluorescent protein fusion proteins form proteasomal sensitive inclusions in primary neurons. Neuroscience. 2001;104(3):901–912. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.McLean PJ, Hyman BT. An alternatively spliced form of rodent a-synuclein forms intracellular inclusions in vitro: role of the carboxy-terminus in a-synuclein aggregation. Neurosci Lett. 2002;323(3):219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]