Background: ITAM-harboring DAP12 contributes to functional osteoclast formation.

Results: Siglec-15 is NFAT2-inducible and functions with DAP12 to promote functional osteoclast development.

Conclusion: Siglec-15 links RANKL-RANK-NFAT2 signaling with ITAM-mediated signaling during osteoclast development.

Significance: Our results provide new insights into how DAP12 transduces extracellular signals into osteoclasts.

Keywords: Actin, Bone, NFAT Transcription Factor, Osteoclast, Sialic Acid, DAP12, ITAM, Siglec

Abstract

Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells that reside in osseous tissues and resorb bone. Signaling mediated by receptor activator of nuclear factor (NF)-κB (RANK) and its ligand leads to the nuclear factor of activated T cells 2/c1 (NFAT2 or NFATc1) expression, a critical step in the formation of functional osteoclasts. In addition, adaptor proteins harboring immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs, such as DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa (DAP12), play essential roles. In this study, we identified the gene encoding the lectin Siglec-15 as NFAT2-inducible, and we found that the protein product links RANK ligand-RANK-NFAT2 and DAP12 signaling in mouse osteoclasts. Both the recognition of sialylated glycans by the Siglec-15 V-set domain and the association with DAP12 through its Lys-272 are essential for its function. When Siglec-15 expression was knocked down, fewer multinucleated cells developed, and those that did were morphologically contracted with disordered actin-ring structures. These changes were accompanied by significantly reduced bone resorption. Siglec-15 formed complexes with Syk through DAP12 in response to vitronectin. Furthermore, chimeric molecules consisting of the extracellular and transmembrane regions of Siglec-15 with a K272A mutation and the cytoplasmic region of DAP12 significantly restored bone resorption in cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression. Together, these results suggested that the Siglec-15-DAP12-Syk-signaling cascade plays a critical role in functional osteoclast formation.

Introduction

Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells that resorb osseous tissue and play an essential role in bone homeostasis (1). Osteoclasts form via fusion of mononucleated precursor cells derived from the colony-forming unit granulocyte-macrophage lineage, branching from the monocyte-macrophage lineage early during differentiation (1, 2). Differentiation is triggered by receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL),2 which binds receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) from osteoclast precursor cells (2–4). In addition to RANKL-RANK signaling, the transmembrane adaptor protein DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa (DAP12) and the Fc receptor common γ chain (FcRγ), each of which contains a cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), contribute to functional osteoclast formation (5); DAP12-deficient mice exhibited mild osteopetrosis (6), and mice lacking both DAP12 and FcRγ were severely osteopetrotic (7, 8), although no significant differences were observed between wild-type and FcRγ-deficient mice (7). How DAP12 transmits extracellular signals to the intracellular signaling machinery is not known, however. DAP12 is expressed as a homodimer on the cell surface and is bound to a DAP12-associated receptor (DAR) via complementarily charged amino acid residues in the transmembrane domain of each protein. DAR-DAP12 mediates the activation and maturation of myeloid lineage cells (9, 10). Although several DARs, including TREM2, SIRPβ1, and MDL-1, are expressed in osteoclasts, the precise roles of these receptors need to be clarified (11, 12).

We previously showed that RANKL-induced expression of nuclear factor of activated T cells 2/c1 (NFAT2 or NFATc1) is essential for osteoclast multinucleation (13). Because the transcription factor NFAT2 is also required for the development of functional osteoclasts in vivo (14), NFAT2 may regulate the expression of membrane proteins that control cell fusion and bone resorption. To understand how the RANKL-RANK-NFAT2 signaling cascade contributes to cell fusion and/or bone resorption, here we screened membrane proteins that are expressed under the control of NFAT2 using signal sequence trap by retrovirus-mediated expression (SST-REX) screening (15), and we identified Siglec-15 as a candidate protein.

The Siglec proteins are a family of lectins that recognize sialylated glycans (16). Most Siglec proteins are expressed in immune cells. They are type I membrane proteins containing one N-terminal V-set immunoglobulin domain that recognizes sialylated glycans and variable numbers of C2-set immunoglobulin domains (16). Unlike CD22 and most CD33-related Siglecs, which have one or more cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs, some Siglec proteins, including Siglec-15, associate with DAP12 and the other tyrosine-based motif YINM-harboring DAP10 (16, 17). Siglec-15, which contains one C2-set domain and is conserved among vertebrates, preferentially recognizes Neu5Acα2–6GalNAcα− structures (α(2,6)-linked sialic acid); the biologic functions of Siglec-15 are still unclear however (17). Interestingly, a recent report has suggested that α(2,6)-linked sialic acid in cell surface glycoconjugates contributes to cell fusion and bone resorption in osteoclasts (18). In this study, we examined the role of Siglec-15 as a DAR in mouse osteoclasts and found that Siglec-15 links RANKL-RANK-NFAT2 signaling with ITAM-mediated intracellular signaling cascades during functional osteoclast development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Osteoclastogenesis in Vitro

Primary osteoclast precursors were prepared as described previously (19). In brief, mouse bone marrow cells were cultured in tissue culture dishes with α-minimal essential medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.5% macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)-conditioned medium (obtained from NIH3T3/pCAhMCSF cells) (20). After an overnight incubation, nonadherent cells were harvested and cultured in plastic dishes with 5% M-CSF conditioned medium for 3 days. Adherent bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were used as osteoclast precursors. For osteoclast differentiation, BMMs were plated at a density of 1.8 × 104 cells/cm2 in tissue culture plates and cultured overnight. The cells were then stimulated with 250 ng/ml recombinant GST-RANKL (21) and 30 ng/ml recombinant mouse M-CSF (R&D Systems). After 3 days, the medium was changed to fresh medium containing RANKL and M-CSF. One day later, osteoclasts were fixed using ice-cold methanol and stained on plastic dishes based on tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity as described previously (21). Under the conditions used, we observed that more than 98% of cells were TRAP-positive. TRAP-positive cells containing three or more nuclei were counted as multinucleated cells. To quantify bone resorption, BMMs were plated in an Osteo Assay Plate (Corning Glass) or on dentine slices (MS Labsystem, Japan), and differentiation was induced. Cells were lysed twice using 1% SDS, and the remaining hydroxylapatite was visualized using 5% AgNO3. Dentine slices were stained with 0.1% toluidine blue to visualize bone resorption pits. To generate preosteoclasts, BMMs were cultured with RANKL and M-CSF for 2 days. Preosteoclasts were obtained using 0.02% EDTA in PBS and plated on dishes precoated with 5 μg/ml vitronectin or cultured in suspension for 15 min. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed as described for Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

Assessing Membrane Proteins Expressed in Osteoclasts Using SST-REX Screening

Poly(A)+ RNA was purified from RAW264-derived osteoclasts using a QuickPrep micro mRNA purification kit (GE Healthcare). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the poly(A)+ RNA, random hexamer primers, and a cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was then inserted into the BstXI sites of pMX-SST using BstXI adapters (Invitrogen). Ligated DNA was electroporated into DH5α cells to create a plasmid cDNA library consisting of 1.14 × 106 independent clones. We examined 1.49 × 106 retroviruses from this cDNA library using SST-REX screening as described previously (15).

Preparation of Total RNA and RT-PCRs

Total RNA was purified using an Isogen kit and the manufacturer's instructions (Nippon Gene, Japan). One microgram of total RNA was used as template for cDNA synthesis with a PrimerScript II kit (Takara Bio). Expression of genes of interest was assessed in PCRs using the following primers: 5′-aggccagcgtctacctgttc-3′ and 5′-tggtgatggctgaggagttc-3′ for Siglec-15; 5′-gaagaagactcaccagaagcag-3′ and 5′-tccaggttatgggcagagatt-3 for CTSK; 5′-ctggacagccagacactactaaag-3′ and 5′-ctcgcggcaagtcttcagag-3′ for MMP9; 5′-ctggaaccgtcaccatcactc-3′ and 5′-cgaaactcgatgactcctcgg-3′ for TREM2; 5′-gctcttggtgaacatatctgcc-3′ and 5′-ggggtgaagaccttaccagac-3′ for Sirpβ1; 5′-ccgtggacttcttcgagcc-3′ and 5′-ctgttgaatcaaactcaatgggc-3′ for αv Integrin; 5′-ccacacgaggcgtgaactc-3′ and 5′-cttcaggttacatcggggtga-3′ for β3 Integrin; and 5′-catgttccagtatgactccactc-3′ and 5′-ggcctcaccccatttgatgt-3′ for GAPDH. To amplify Siglec-15 mRNA, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide was added to the reaction mixture.

Plasmids and Retroviral Transduction

Two retroviral vectors encoding mouse Siglec-15-specific shRNA (shSiglec-15-1, 5′-gctcaggagtccaattatgaa-3′; shSiglec-15-3, 5′-gggatcccttgtgaaaactag-3′) were constructed using pCX6#RED (22). A vector designed to knock down GFP expression was used as a control (22). Mouse cDNA sequences encoding Siglec-15 and DAP12 were amplified in RT-PCRs and subcloned into the pBlueScriptII KS+ vector (Stratagene). Silent mutations were introduced into the target sequences of shSiglec-15-1 and shSiglec-15-3 to escape from RNA interference and prepared (5′-gcCcaAgaAtcAaaCtaCgaa-3′ and (5′-gggCtcActGgtAaaaacCCg-3′, respectively). QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kits (Stratagene) were used to create point mutations that resulted in the K272A (KA) mutant of Siglec-15 and D52A (DA) and the Y92F/Y103F (2YF) variants of DAP12. A deletion mutation was introduced into Siglec-15 using a PCR to remove Trp-43 to Thr-165, including the V-set domain. To construct SSD-KA, cDNAs encoding the initial methionine to Gly-258 of Siglec-15 with the K272A mutation and Arg-68 to Arg-114 of DAP12 were amplified in PCRs and ligated using the In-fusion HD cloning system (Clontech). cDNA fragments encoding Siglec-15 with the silent mutations described above were used as a template for mutagenesis. cDNA fragments encoding Siglec-15 and DAP12 were introduced into the pCX4-based retroviral vector pCX4MFgfp and pCX4MHpur vector, respectively (23).

To generate retroviral vectors, plasmids were first introduced into the platinum-E (Plat-E) packaging cell line with the pE-eco and pGP vectors (Takara Bio), and the cells were cultured for 72 h. Retroviral supernatants were harvested every 24 h and filtered through 0.45-μm pore filters before they were used as retrovirus stocks. To generate cells in which Siglec-15 expression was knocked down, BMMs were infected with virus for 24 h, selected in the presence of puromycin for 2 days, and used in experiments as osteoclast precursors. To overexpress Siglec-15, cells were infected with retrovirus in the presence of RANKL and M-CSF, and after 24 h, the medium was changed to fresh differentiation medium.

Preparation and Purification of Anti-mouse Siglec-15 Polyclonal Antibody

cDNA encoding the extracellular region of mouse Siglec-15, a PreScission protease recognition sequence, and the Fc fragment of mouse IgG2a were inserted to the retroviral vector pCXGFP (24). CHO-S EcoR cells (24), which express ecotropic retrovirus receptor, were infected with retrovirus derived from this vector, and cells showing the most robust GFP expression (top 10%) were sorted using a FACSCalibur system (BD Biosciences). Selected cells were cultured with CHO-SFMII (Invitrogen) at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml for 5 days, and conditioned media were collected. The Siglec-15-Fc fusion protein was affinity-purified using protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare), and the extracellular region of Siglec-15 was freed using PreScission protease (GE Healthcare). Incubation with glutathione-Sepharose removed the protease. One milligram of purified recombinant protein was used to immunize a rabbit; blood was collected 1 week after the sixth boost, and sera were prepared using standard methods. Anti-mouse Siglec-15 antibody was obtained using affinity chromatography with immobilized recombinant Siglec-15-Fc.

Western Blotting and Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm NaF, 2 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm β-glycerophosphate, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). After a 30-min incubation on ice, cell lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used as total cell lysate. For immunoprecipitation, total cell lysate was incubated with 1 μg of antibody overnight, followed by a 2-h incubation with protein A- or protein G-Sepharose. Beads were washed with 1 ml of lysis buffer five times and suspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. After an incubation at 100 °C for 4 min, supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE. To purify cell surface proteins, biotinylation analysis was performed using a cell surface protein isolation kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Immunoblotting was performed with an Immobilon Western system (Millipore). Anti-NFAT2 mouse monoclonal antibody (7A6, sc-7294), anti-Syk rabbit polyclonal antibody (sc-1077), and anti-c-Fms rabbit polyclonal antibody (sc-692) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 and anti-β-actin antibody were obtained from Sigma. Anti-HA rat monoclonal antibody (3F10; Roche Applied Science) was also used in some experiments. Horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse, -rat, and -rabbit IgG were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy and Image Analysis

Cells on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. After blocking with 5% BSA for 30 min, cells were incubated with anti-Siglec-15 or control antibody for 1 h, followed by Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody, rhodamine-linked phalloidin, and Hoechst 33342 for 30 min. The plasma membrane was stained with rhodamine-labeled wheat germ agglutinin (Vector Laboratories) before the permeabilization step. Coverslips were mounted in ProLong Gold (Molecular Probes), and fluorescence images were taken under an LSM710 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss).

RESULTS

NFAT2-dependent Expression and Plasma Membrane Localization of Siglec-15 in Osteoclasts

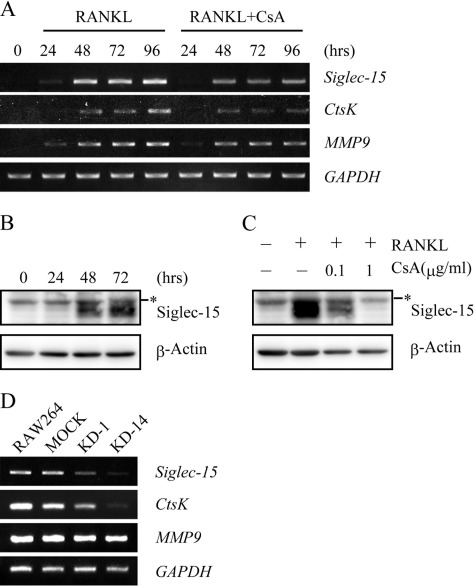

We examined membrane proteins expressed in mouse osteoclasts using SST-REX screening and identified Siglec-15. Siglec-15 was originally identified as a Siglec ortholog (17), although its biological function was unclear. Siglec-15 mRNA and protein expression were detected in mouse BMMs 48 h after RANKL and M-CSF administration (Fig. 1, A and B). RANKL-dependent induction of the expression of Siglec-15 and cathepsin K (ctsK), another NFAT2-regulated gene, was dose-dependently inhibited by cyclosporin A (CsA), an inhibitor of the NFAT2 activator calcineurin (Fig. 1, A and C). However, MMP9 expression, which is independent of NFAT2, was not affected by CsA (Fig. 1A) (25, 26). In addition, Siglec-15 mRNA was observed 48 h after RANKL administration in RAW264 cells, an effect that was significantly suppressed in the KD-1 and KD-14 RAW264 clones, in which NFAT2 expression was knocked down (13, 27) (Fig. 1D). These results suggested that Siglec-15 expression is controlled by NFAT2.

FIGURE 1.

Siglec-15 expression induced by NFAT2. A, expression of Siglec-15 mRNA during in vitro osteoclastogenesis. BMMs were cultured with RANKL and M-CSF in the absence or presence of 1 μg/ml CsA. Siglec-15, cathepsin K (CtsK), and MMP9 mRNA expression levels were analyzed at the indicated time points using RT-PCRs. GAPDH was used as an internal control. B, expression of Siglec-15. BMMs were treated with RANKL and M-CSF as described in A. Expression of Siglec-15 was examined at the indicated time points using immunoblots and anti-Siglec-15 polyclonal antibody. The asterisk indicates nonspecific signals from the antibody. Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody was used to monitor the amount of protein in each sample. C, CsA-mediated suppression of Siglec-15 expression. BMMs were cultured for 72 h in the absence or presence of CsA as indicated, and Siglec-15 and β-actin expression was assessed on immunoblots as described in B. D, expression of Siglec-15 mRNA in RAW264 cells with knocked down NFAT2 expression. Parental RAW264 cells, mock-transfected cells, and two clones expressing shRNA specific for NFAT2 (clone KD1 and KD-14) were cultured with RANKL for 96 h, and the mRNA expression was examined as described in A).

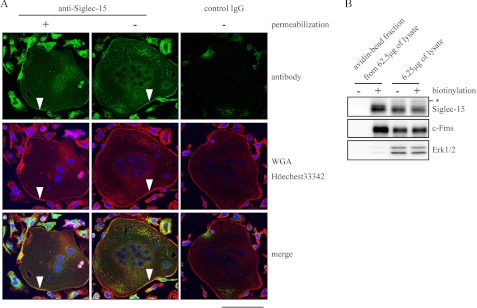

Angata et al. (17) previously reported that Siglec-15 predominantly localizes in intracellular membranes of a subset of macrophages and/or dendritic cells in lymph nodes. We prepared an antibody specific for the extracellular region of Siglec-15 and performed immunofluorescence analysis to evaluate the localization of Siglec-15 in osteoclasts. When the plasma membrane was visualized using rhodamine-labeled wheat germ agglutinin after fixation, signals reflecting anti-Siglec-15 antibody merged with the wheat germ agglutinin-specific signals in multinucleated (marked with arrowheads in Fig. 2A) and mononucleated cells. This staining pattern was also detected without the permeabilization step, whereas control rabbit antibody did not produce notable signals (Fig. 2A). Of note, most of the mononucleated cells developed from BMMs by RANKL and M-CSF treatment for 96 h are TRAP-positive (see Fig. 4, D and E), suggesting that these cells are mononucleated osteoclasts. Thus, Siglec-15 appeared to localize on the plasma membrane of mononucleated and multinucleated osteoclasts. Cell surface biotinylation analysis further confirmed the localization of Siglec-15 on the plasma membrane in osteoclasts, because, unlike the cytosolic/nuclear protein Erk1/2, Siglec-15 was detected in the same avidin-agarose bead fraction as the M-CSF receptor c-Fms (Fig. 2B). The difference in Siglec-15 localization observed in a previous study (17) and our results may reflect the different cell systems.

FIGURE 2.

Localization of Siglec-15 in the osteoclast plasma membrane. A, BMMs were cultured with RANKL and M-CSF for 96 h and subjected to immunostaining with the anti-Siglec-15 antibody with or without cell permeabilization. Normal rabbit IgG was used as a control antibody. Green, antibody-related signals; red, wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-rhodamine; blue, Hoechst 33342. Arrowheads indicate the plasma membranes of multinucleated osteoclasts. B, cell surface biotinylation analysis. BMMs were cultured as described in A and treated with or without the Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin. Cell lysates were prepared, and biotinylated proteins were purified with avidin beads, and elution fractions from 62.5 μg of total cell lysates from mock-treated and biotin-labeled cells were loaded in the left two lanes. Total cell lysates (6.25 μg) before the avidin beads were loaded in the right two lanes to confirm that equal amounts of cell extracts were used in the avidin-bead purification step. c-Fms and Erk1/2 were used as control plasma membrane and cytosolic proteins, respectively. The asterisk indicates nonspecific signals as described for Fig. 1, B and C.

FIGURE 4.

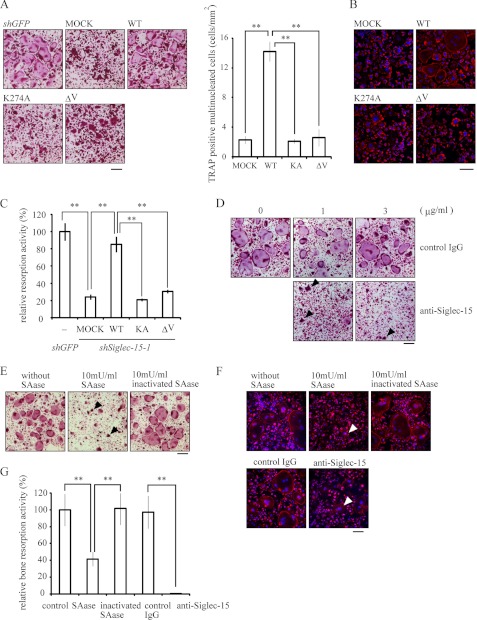

Functional interactions between Siglec-15 and sialylated glycans. A, essential roles of the V-set domain and Lys-272 in Siglec-15 for osteoclast formation. FLAG-tagged wild-type Siglec-15, a variant containing the K272A mutation (KA), and a variant lacking the V-set domain (ΔV) were introduced into shSiglec-15-1-expressing cells. An empty vector (Mock) and a vector encoding shRNA for GFP (shGFP) were used as controls. Cells were stimulated with RANKL and M-CSF and stained for TRAP. Cell morphologies (left panel) and the numbers of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells are shown (right panel). **, p < 0.01. B, actin-ring formation was examined in cells prepared as described in A and stained with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Bar indicates 100 μm. C, resorption assays were performed using hydroxylapatite-coated dishes and cells prepared as described in A. Resorption activities were measured and compared with results observed with shGFP-treated cells. **, p < 0.01. D, anti-Siglec-15 antibody blocked osteoclast formation. BMMs were cultured with RANKL, M-CSF, and the indicated concentrations of anti-Siglec-15 antibody or control rabbit IgG for 96 h, followed by TRAP staining. Bar indicates 200 μm. E, BMMs were treated with the indicated amount of SAase for 24 h after RANKL and M-CSF stimulation, followed by TRAP staining at 96 h. Bar indicates 200 μm. F, actin-ring structures were examined in the antibody- or SAase-treated cells. Osteoclasts generated under the conditions described in D or E were stained with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Bar indicates 100 μm. G, resorption assays were performed using mock-, anti-Siglec-15 antibody-, or SAase-treated cells cultured on hydroxylapatite-coated dishes for 96 h. Arrowheads indicate typical multinucleated cells in D–F. **, p < 0.01.

Siglec-15 Is Essential for Functional Osteoclast Formation

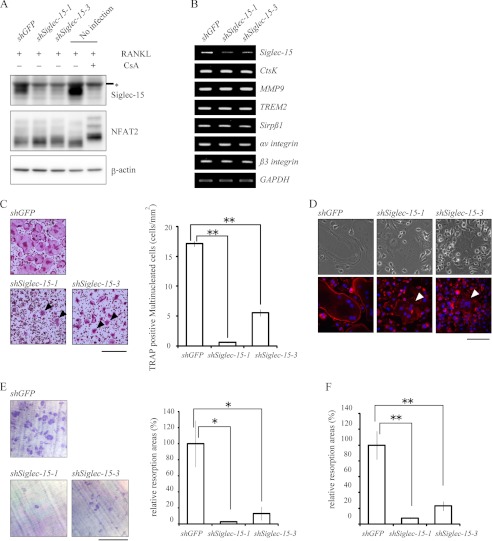

We then generated cells in which Siglec-15 expression was knocked down, and we examined the effects on osteoclastogenesis. Two shRNAs, shSiglec-15-1 and shSiglec-15-3, significantly suppressed Siglec-15 expression 96 h after RANKL stimulation, a time point when mature functional osteoclasts appeared among control cells (Fig. 3A). Dephosphorylation of NFAT2 in response to RANKL was not affected however (Fig. 3A). In fact, the expression levels of osteoclastic marker genes such as ctsK, MMP9, αv and β3 integrins, TREM2, and Sirpβ1 were similar between knockdown and control cells (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of knocking down Siglec-15 expression on multinucleated cell formation, actin-ring structures, and bone resorption. A, cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression. BMMs infected with retroviral vectors encoding control shRNA (shGFP) or either of two shRNAs specific for Siglec-15 (shSiglec-15-1 and shSiglec-15-3) were cultured for 96 h with RANKL and M-CSF. Expression of Siglec-15 (upper panel) and NFAT2 (middle panel) was examined by Western blotting. The asterisk indicates nonspecific signals as described in Figs. 1 and 2. NFAT2 in the rightmost lane showed a phosphorylation-dependent band shift following CsA treatment. Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody was used to monitor the amount of protein in the samples. B, expression of osteoclastic marker genes in cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression. Total RNA was prepared from cells cultured as described in A, and expression levels of osteoclastic marker genes were analyzed using RT-PCRs. GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal control. C, morphology of shRNA-treated cells. Control cells and cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression were cultured for 96 h, followed by TRAP staining (left panel). Bar indicates 500 μm. The numbers of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells are shown (right panel). **, p < 0.01. D, actin-rings in cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression. Cells were prepared as described in C and stained with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Bar indicates 100 μm. C and D, arrows indicate contracted multinucleated osteoclasts. E, resorption assays on dentine slices. shGFP-treated control cells (upper panel) and cells treated with either Siglec-15-specific shRNA (lower panel) were cultured on dentine slices. After 96 h, the slices were stained with 0.1% toluidine blue (left panel), and resorption areas were measured and compared with those observed with control cells (right panel). Bar indicates 500 μm. *, p < 0.05. F, resorption assay on hydroxylapatite-coated dishes. The three types of cells described in E were cultured on hydroxylapatite-coated dishes. Resorption by cells in which Siglec-15 expression was knocked down was measured and compared with results obtained with control cells.

Despite expression of these marker genes, significantly fewer TRAP-positive multinucleated cell formed among cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the cells that did form showed a contracted morphology with disordered actin-ring structures (Fig. 3, C and D). Significantly reduced bone resorption was also noted on dentine slices and dishes coated with synthetic hydroxylapatite (Fig. 3, E and F). The accumulation of actin was also detectable in some of the small cells, but their ordered structures have not been clearly identified. Phenotypes unique to Siglec-15 knockdown cells were rescued by introducing Siglec-15 with silent mutations in shRNA target sequences (Fig. 4, A–C), confirming that these defects were principally caused by the reduced Siglec-15 expression level and not off-target effects.

Sialylated Glycoconjugate Binding Is Essential for Siglec-15 Functions

Siglec family members recognize sialylated glycans via an N-terminal V-set domain (16), and Siglec-15 preferentially binds to Neu5Acα2–6GalNAcα− structures (17). We found that a Siglec-15 variant lacking the V-set domain did not rescue the defective cell morphologies (Fig. 4A), actin-ring structures (Fig. 4B), or bone resorbing activity (Fig. 4C) observed in cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression, suggesting that the Siglec-15 V-set domain is essential for functional osteoclast formation.

We then tested whether antibody specific for the extracellular region of Siglec-15 disrupted functional osteoclast formation. Treatment with the antibody significantly suppressed spreading of multinucleated osteoclasts (Fig. 4D), which confirmed the importance of the Siglec-15 extracellular region. Of note, a previous study showed that desialylation of the cell surface with 100 milliunits/ml sialidase (SAase) inhibits RANKL-induced formation of multinucleated osteoclast, and α(2,6)-linked sialic acid on glycoconjugates contributes to polykaryon formation in osteoclasts (18). Similar to results observed in cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression, treatment with 10 milliunits/ml SAase resulted in TRAP-positive multinucleated osteoclasts that did not spread (Figs. 3C and 4E). Cells treated with either the antibody or SAase did not show the actin-ring structures or resorb bone (Fig. 4, F and G). Together, these results suggested that osteoclast development requires sialylated glycan recognition by Siglec-15.

Siglec-15 Binds DAP12 and Regulates Actin Reorganization

Siglec-15 interacts with the ITAM-bearing protein DAP12 through positively charged Lys-272 in the Siglec-15 transmembrane domain (17). Mice lacking DAP12 developed osteopetrosis (6), and DAP12 null cells showed defects in actin-ring and multinucleated cell formation in vitro (11, 28, 29). Furthermore, retrovirus-mediated transduction of wild-type DAP12 into BMMs lacking DAP12 rescued these defects, but not when a D52A mutation was introduced into the transmembrane domain of DAP12 (30). Osteoclasts with knocked down Siglec-15 expression showed defective formation of spread multinucleated cells, actin-ring formation, and bone resorption (Fig. 3, C–F), and the introduction of a variant harboring a mutation at Lys-272 (K272A) did not rescue these phenotypes. When K272A and D52A mutations were introduced into Siglec-15 and DAP12, respectively, the proteins did not bind each other (supplemental Fig. S1). Together, these results suggest that Siglec-15 and DAP12 interact via Lys-272 in Siglec-15 and Asp-52 in DAP12 to regulate functional osteoclast formation.

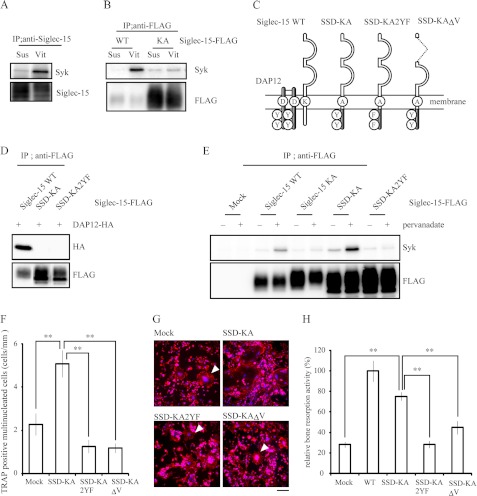

Siglec-15 Regulates DAP12-Syk Signaling

Given the critical role of Lys-272 in Siglec-15 (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S1), Siglec-15 may act as a DAR in osteoclasts. Of note, phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the ITAM of DAP12 provides a docking site for the SH2 domain of Syk and allows vitronectin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk in preosteoclasts (31). To examine the roles of Siglec-15 in DAP12-Syk signaling, we tested whether Syk and Siglec-15 form a complex in preosteoclasts in response to vitronectin. Vitronectin increased the amount of Syk that coimmunoprecipitated with Siglec-15 (Fig. 5A), an association that was dependent on Lys-272, because Syk levels did not increase in immunoprecipitates containing the KA mutant (Fig. 5B). These results suggested that Siglec-15 binds to Syk through DAP12. When we transfected BMMs with FLAG-Siglec-15, we observed differences in anti-FLAG immunoreactivity on the blots of the WT and KA groups (Fig. 5B). This phenomenon was observed repeatedly, even though equal titers of retrovirus were used for the two groups (Fig. 5E, lower panel). The reason for this discrepancy is not presently clear.

FIGURE 5.

Siglec-15 is a DAP12-associated receptor in osteoclasts. A, vitronectin-dependent interaction between Siglec-15 and Syk. BMMs were cultured with M-CSF and RANKL for 48 h. Cells were then lifted and either maintained in suspension (Sus) or plated on vitronectin (Vit) for 15 min. Immunoprecipitates (IP) from each group were probed with anti-Syk and anti-Siglec-15 antibody. B, Lys-272 in Siglec-15 is indispensable for the interaction between Siglec-15 and Syk. BMMs expressing FLAG-tagged wild-type Siglec-15 or the KA mutant were cultured as described in A, and immunoprecipitates pulled down with anti-FLAG antibody were immunoblotted with anti-Syk or anti-FLAG antibody. C, schematic representations of Siglec-15 and DAP12 chimeras. D, HEK293T cells coexpressing HA-tagged DAP12 and FLAG-tagged wild-type Siglec-15, SSD-KA, or SSD-KA2YF were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-HA (upper panel) or anti-FLAG (lower panel) antibody. E, interaction between SSD-KA and Syk was dependent on ITAM phosphorylation. BMMs were infected with retrovirus-encoding FLAG-tagged Siglec-15 and SSD-KA. The cells were cultured for 48 h in the presence of RANKL and M-CSF and treated with 1 mm pervanadate for 5 min. Immunoprecipitates obtained with anti-FLAG antibody were immunoblotted with anti-Syk (upper panel) and anti-FLAG (lower panel) antibody. F–H, SSD-KA partially but significantly rescued the defects observed in osteoclasts with knocked down Siglec-15 expression. Wild-type Siglec-15 and Siglec-15-DAP12 chimeric constructs were introduced into shSiglec-15-1-expressing cells. The cells were stimulated with RANKL and M-CSF, and the number of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (F), rhodamine-phalloidin staining in multinucleated cells (G), and synthetic hydroxylapatite resorption activity (H) were examined. G, arrowheads indicate typical multinucleated cells. The scale bar in G represents 100 μm. **, p < 0.01 in F and H.

Next, we constructed the SSD-KA chimera, consisting of the extracellular and transmembrane region of Siglec-15 with the K272A mutation and the intracellular region of DAP12; this construct should mimic the Siglec-15-DAP12 complex without interacting with endogenous DAP12 (Fig. 5C). Osteoclasts were generated from BMMs after introducing either wild-type Siglec-15, the KA mutant, or SSD-KA. Whereas constructs containing KA mutation did not bind to DAP12 (Fig. 5D), the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor pervanadate induced a Lys-272-dependent interaction between Siglec-15 and Syk and increased binding between SSD-KA and Syk (Fig. 5E). The latter interaction was dependent on tyrosine phosphorylation in the ITAM of SSD-KA, because mutating both ITAM tyrosine residues to phenylalanine (SSD-KA2YF) inhibited the interaction with Syk (Fig. 5E). These results suggested that the chimeric mutant SSD-KA mimicked the Siglec-15-DAP12 complex without the need for endogenous DAP12.

Finally, when we introduced SSD-KA into cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression, RANKL and M-CSF induced mature osteoclast development, including cell multinucleation, actin-ring formation, and bone resorption (Fig. 5, F–H). In contrast, SSD-KA2YF and SSD-KA lacking the V-set domain (SSD-KAΔV) did not rescue actin-ring formation or restore bone resorption in osteoclasts with reduced Siglec-15 expression (Fig. 5, F and G). These results demonstrate that the Siglec-15-DAP12-Syk signaling pathway regulates the formation of functional osteoclasts in vitro.

DISCUSSION

The ITAM-bearing protein DAP12 plays an important role in osteoclast differentiation, and DAP12-deficient mice exhibit mild osteopetrosis (6). Signaling via RANKL-RANK (7), M-CSF-c-Fms (30), and ECM-αvβ3 integrin (31) triggers ITAM signaling, which is mediated by Syk tyrosine kinase, the Rho family guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav3, and phospholipase Cγ (7, 31, 32). How these signals stimulate ITAM signaling is still unclear however. Because DAP12 is thought to associate with DAR partner proteins, identifying DAR(s) is an important first step to elucidate DAP12-mediated signaling cascades. In this study, we identified Siglec-15 as an NFAT2 inducible under RANKL-RANK stimulation and analyzed this DAR in osteoclasts.

We showed that Siglec-15 is required for multinucleated osteoclast formation, actin rearrangement in multinucleated cells, and bone resorbing activity in a DAP12-dependent manner. Differentiation of osteoclasts with reduced Siglec-15 expression appeared normal in terms of NFAT2 expression, the phosphorylation-dependent NFAT2 band shift, and expression profiles of several marker genes. These phenotypes were consistent with DAP12-deficient osteoclasts that express comparable levels of marker genes (8, 11, 28, 30). DAP12-deficient BMMs also do not form functional multinucleated cells and actin-ring structures in vitro even in the presence of RANKL and M-CSF (11, 28), the same as osteoclasts with knocked down Siglec-15 expression. Moreover, actin-ring formation was not observed in an osteoblast coculture system (29). A Siglec-15 variant carrying the K272A mutation failed to rescue the effects of knocked down Siglec-15 expression (Fig. 4). Furthermore, introduction of the SSD-KA chimera significantly rescued multinucleated cell formation, actin-ring formation, and bone resorption in cells with knocked down Siglec-15 expression (Fig. 5). These results support the importance of the interaction between Siglec-15 and DAP12 for functional osteoclast formation. Because Siglec-15 also interacts with the YINM motif-bearing protein DAP10 in a Lys-272-dependent manner (17), the partial rather than full rescue observed with SSD-KA may result from the absence of YINM in the Siglec-15 complex. Additional uncharacterized domain(s) in the cytoplasmic region of Siglec-15 may also be important however.

Specificity of ligand recognition of each DAR may reflect its own characteristic property. Siglec proteins generally recognize sialylated glycans and Siglec-15 preferentially binds Neu5Acα2–6GalNAcα− structures (17). Our results clearly showed that the V-set domain of Siglec-15, which recognizes sialylated glycans, is essential, because a construct lacking the V-set domain did not rescue the defects induced by knocked down Siglec-15 expression. Interestingly, Takahata et al. reported that α(2,6)-linked sialic acid from cell surface glycoconjugates is required for polykaryon formation by osteoclasts (18). Here we showed that culturing BMMs in differentiation media containing 10 milliunits/ml SAase inhibited actin-ring formation in TRAP-positive multinucleated cells. Together, these results suggested that sialic acid binding to Siglec-15 is critical in osteoclast formation. The predominant localization of Siglec-15 on the plasma membrane and the inhibitory effects of antibody raised against the Siglec-15 extracellular domain likely reflect this observation. After we completed this study, Hinuma et al. (33) reported that anti-Siglec-15 antibody inhibited RANKL- and TNF-α-induced osteoclast formation in vitro, not only in mouse but also in human cells. These results suggest the important role of the Siglec-15 extracellular domain in human cells as well.

In addition to Siglec-15, the expression of various DARs, including TREM2, TREM3, Sirpβ1, and MDL-1, has been observed in osteoclasts (11). When BMMs were transfected with siRNA specific for MDL-1 and cultured with RANKL and M-CSF, TRAP-positive multinucleated cell formation was significantly reduced (6). Reduced TREM2 expression in the mouse RAW264 macrophage cell line also suppressed the formation of multinucleated osteoclasts in response to RANKL (34). Furthermore, differentiation of osteoclasts from peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from patients with genetic defects in human TREM2 was reported to be impaired or delayed (35, 36). Of note, genetic defects in human DAP12 and TREM2 result in a rare syndrome characterized by bone cysts and presenilin dementia called polycystic lipomembranous osteodysplasia with sclerosing leukoencephalopathy, also known as Nasu-Hakola disease (37, 38). However, Colonna et al. (39) reported that a lack of TREM2 in mice did not result in osteopetrosis. Histologic and metabolic analyses of bone in Siglec-15-deficient mice may elucidate the physiologic roles of Siglec-15 in vivo and expand our understanding of the roles of DARs.

In conclusion, our results show that Siglec-15 links the RANKL-RANK-NFAT2 signaling with the ITAM signaling and plays an essential role in in vitro functional osteoclast formation. These findings help to elucidate the mechanisms underlying osteoclastogenesis and bone metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Toshio Kitamura for providing plasmids and Platinum-E cells, Dr. Tsuyoshi Akagi for providing pCX4 vectors, and Dr. Tomoyuki Shishido for providing Chinese hamster ovary suspension EcoR cells.

This work was supported by Grants-in-aid from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI 17791000, 19791031, 21791394, and 23592214 (to N. I. K.) and 22791382 (to T. O.), the Foundation for the Nara Institute of Science and Technology (to N. I. K.), and the Nara Institute of Science and Technology Global-Centers of Excellence Program.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- RANKL

- receptor activator of NF-κB ligand

- ITAM

- tyrosine-based activation motif

- RANK

- receptor activator of NF-κB

- NFAT

- nuclear factor of activated T cells

- DAR

- DAP12-associated receptor

- SST-REX

- signal sequence trap by retrovirus-mediated expression

- SAase

- sialidase

- BMM

- bone marrow-derived macrophage

- CsA

- cyclosporin A

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Väänänen H. K., Laitala-Leinonen T. (2008) Osteoclast lineage and function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 473, 132–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suda T., Takahashi N., Udagawa N., Jimi E., Gillespie M. T., Martin T. J. (1999) Modulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the new members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and ligand families. Endocr. Rev. 20, 345–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyle W. J., Simonet W. S., Lacey D. L. (2003) Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boyce B. F., Xing L. (2008) Functions of RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 473, 139–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakashima T., Takayanagi H. (2009) Osteoclasts and the immune system. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 27, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kaifu T., Nakahara J., Inui M., Mishima K., Momiyama T., Kaji M., Sugahara A., Koito H., Ujike-Asai A., Nakamura A., Kanazawa K., Tan-Takeuchi K., Iwasaki K., Yokoyama W. M., Kudo A., Fujiwara M., Asou H., Takai T. (2003) Osteopetrosis and thalamic hypomyelinosis with synaptic degeneration in DAP12-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 323–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koga T., Inui M., Inoue K., Kim S., Suematsu A., Kobayashi E., Iwata T., Ohnishi H., Matozaki T., Kodama T., Taniguchi T., Takayanagi H., Takai T. (2004) Costimulatory signals mediated by the ITAM motif cooperate with RANKL for bone homeostasis. Nature 428, 758–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mócsai A., Humphrey M. B., Van Ziffle J. A., Hu Y., Burghardt A., Spusta S. C., Majumdar S., Lanier L. L., Lowell C. A., Nakamura M. C. (2004) The immunomodulatory adapter proteins DAP12 and Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRγ) regulate development of functional osteoclasts through the Syk tyrosine kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6158–6163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aoki N., Kimura S., Takiyama Y., Atsuta Y., Abe A., Sato K., Katagiri M. (2000) The role of the DAP12 signal in mouse myeloid differentiation. J. Immunol. 165, 3790–3796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gingras M. C., Lapillonne H., Margolin J. F. (2002) TREM-1, MDL-1, and DAP12 expression is associated with a mature stage of myeloid development. Mol. Immunol. 38, 817–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Humphrey M. B., Ogasawara K., Yao W., Spusta S. C., Daws M. R., Lane N. E., Lanier L. L., Nakamura M. C. (2004) The signaling adapter protein DAP12 regulates multinucleation during osteoclast development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 19, 224–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Inui M., Kikuchi Y., Aoki N., Endo S., Maeda T., Sugahara-Tobinai A., Fujimura S., Nakamura A., Kumanogoh A., Colonna M., Takai T. (2009) Signal adaptor DAP10 associates with MDL-1 and triggers osteoclastogenesis in cooperation with DAP12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4816–4821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ishida N., Hayashi K., Hoshijima M., Ogawa T., Koga S., Miyatake Y., Kumegawa M., Kimura T., Takeya T. (2002) Large scale gene expression analysis of osteoclastogenesis in vitro and elucidation of NFAT2 as a key regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41147–41156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asagiri M., Sato K., Usami T., Ochi S., Nishina H., Yoshida H., Morita I., Wagner E. F., Mak T. W., Serfling E., Takayanagi H. (2005) Autoamplification of NFATc1 expression determines its essential role in bone homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1261–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kojima T., Kitamura T. (1999) A signal sequence trap based on a constitutively active cytokine receptor. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 487–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crocker P. R., Paulson J. C., Varki A. (2007) Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Angata T., Tabuchi Y., Nakamura K., Nakamura M. (2007) Siglec-15. An immune system Siglec conserved throughout vertebrate evolution. Glycobiology 17, 838–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takahata M., Iwasaki N., Nakagawa H., Abe Y., Watanabe T., Ito M., Majima T., Minami A. (2007) Sialylation of cell surface glycoconjugates is essential for osteoclastogenesis. Bone 41, 77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ogawa T., Ishida-Kitagawa N., Tanaka A., Matsumoto T., Hirouchi T., Akimaru M., Tanihara M., Yogo K., Takeya T. (2006) A novel role of serine (l-Ser) for the expression of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) 2 in receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL)-induced osteoclastogenesis in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 24, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yogo K., Mizutamari M., Mishima K., Takenouchi H., Ishida-Kitagawa N., Sasaki T., Takeya T. (2006) Src homology 2 (SH2)-containing 5′-inositol phosphatase localizes to podosomes, and the SH2 domain is implicated in the attenuation of bone resorption in osteoclasts. Endocrinology 147, 3307–3317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meiyanto E., Hoshijima M., Ogawa T., Ishida N., Takeya T. (2001) Osteoclast differentiation factor modulates cell cycle machinery and causes a delay in S phase progression in RAW264 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 282, 278–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bao X., Ogawa T., Se S., Akiyama M., Bahtiar A., Takeya T., Ishida-Kitagawa N. (2011) Acid sphingomyelinase regulates osteoclastogenesis by modulating sphingosine kinases downstream of RANKL signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 405, 533–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Akagi T., Sasai K., Hanafusa H. (2003) Refractory nature of normal human diploid fibroblasts with respect to oncogene-mediated transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13567–13572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suzuki J., Fukuda M., Kawata S., Maruoka M., Kubo Y., Takeya T., Shishido T. (2006) A rapid protein expression and purification system using Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing retrovirus receptor. J. Biotechnol. 126, 463–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsumoto M., Kogawa M., Wada S., Takayanagi H., Tsujimoto M., Katayama S., Hisatake K., Nogi Y. (2004) Essential role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in cathepsin K gene expression during osteoclastogenesis through association of NFATc1 and PU.1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45969–45979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsuo K., Galson D. L., Zhao C., Peng L., Laplace C., Wang K. Z., Bachler M. A., Amano H., Aburatani H., Ishikawa H., Wagner E. F. (2004) Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) rescues osteoclastogenesis in precursors lacking c-Fos. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26475–26480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishida N., Hayashi K., Hattori A., Yogo K., Kimura T., Takeya T. (2006) CCR1 acts downstream of NFAT2 in osteoclastogenesis and enhances cell migration. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Faccio R., Zou W., Colaianni G., Teitelbaum S. L., Ross F. P. (2003) High dose M-CSF partially rescues the Dap12−/− osteoclast phenotype. J. Cell. Biochem. 90, 871–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zou W., Zhu T., Craft C. S., Broekelmann T. J., Mecham R. P., Teitelbaum S. L. (2010) Cytoskeletal dysfunction dominates in DAP12-deficient osteoclasts. J. Cell Sci. 123, 2955–2963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zou W., Reeve J. L., Liu Y., Teitelbaum S. L., Ross F. P. (2008) DAP12 couples c-Fms activation to the osteoclast cytoskeleton by recruitment of Syk. Mol. Cell 31, 422–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zou W., Kitaura H., Reeve J., Long F., Tybulewicz V. L., Shattil S. J., Ginsberg M. H., Ross F. P., Teitelbaum S. L. (2007) Syk, c-Src, the αvβ3 integrin, and ITAM immunoreceptors, in concert, regulate osteoclastic bone resorption. J. Cell Biol. 176, 877–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Faccio R., Teitelbaum S. L., Fujikawa K., Chappel J., Zallone A., Tybulewicz V. L., Ross F. P., Swat W. (2005) Vav3 regulates osteoclast function and bone mass. Nat. Med. 11, 284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hiruma Y., Hirai T., Tsuda E. (2011) Siglec-15, a member of the sialic acid-binding lectin, is a novel regulator for osteoclast differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 409, 424–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Humphrey M. B., Daws M. R., Spusta S. C., Niemi E. C., Torchia J. A., Lanier L. L., Seaman W. E., Nakamura M. C. (2006) TREM2, a DAP12-associated receptor, regulates osteoclast differentiation and function. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cella M., Buonsanti C., Strader C., Kondo T., Salmaggi A., Colonna M. (2003) Impaired differentiation of osteoclasts in TREM-2-deficient individuals. J. Exp. Med. 198, 645–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paloneva J., Mandelin J., Kiialainen A., Bohling T., Prudlo J., Hakola P., Haltia M., Konttinen Y. T., Peltonen L. (2003) DAP12/TREM2 deficiency results in impaired osteoclast differentiation and osteoporotic features. J. Exp. Med. 198, 669–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paloneva J., Kestilä M., Wu J., Salminen A., Böhling T., Ruotsalainen V., Hakola P., Bakker A. B., Phillips J. H., Pekkarinen P., Lanier L. L., Timonen T., Peltonen L. (2000) Loss-of-function mutations in TYROBP (DAP12) result in a presenilin dementia with bone cysts. Nat. Genet. 25, 357–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paloneva J., Manninen T., Christman G., Hovanes K., Mandelin J., Adolfsson R., Bianchin M., Bird T., Miranda R., Salmaggi A., Tranebjaerg L., Konttinen Y., Peltonen L. (2002) Mutations in two genes encoding different subunits of a receptor signaling complex result in an identical disease phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 656–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Colonna M., Turnbull I., Klesney-Tait J. (2007) The enigmatic function of TREM-2 in osteoclastogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 602, 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.