Background: ABC transporters are important substrate transport systems in all forms of life.

Results: Residual dipolar coupling (RDCs) and solvent-PRE experiments are employed to characterize structural changes of MalE, induced upon addition of MalF-P2.

Conclusion: MalF-P2 induces an activated structural conformation of the substrate-binding protein MalE, which is required for substrate transport.

Significance: This work gives insight into the activation mechanism of ABC transporters.

Keywords: ABC Transporter, Membrane Proteins, NMR, Receptor Structure-Function, Structural Biology, Residual Dipolar Couplings, Solvent-PRE

Abstract

In a recent study we described the second periplasmic loop P2 of the transmembrane protein MalF (MalF-P2) of the maltose ATP-binding cassette transporter (MalFGK2-E) as an important element in the recognition of substrate by the maltose-binding protein MalE. In this study, we focus on MalE and find that MalE undergoes a structural rearrangement after addition of MalF-P2. Analysis of residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) shows that binding of MalF-P2 induces a semiopen state of MalE in the presence and absence of maltose, whereas maltose is retained in the binding pocket. These data are in agreement with paramagnetic relaxation enhancement experiments. After addition of MalF-P2, an increased solvent accessibility for residues in the vicinity of the maltose-binding site of MalE is observed. MalF-P2 is thus not only responsible for substrate recognition, but also directly involved in activation of substrate transport. The observation that substrate-bound and substrate-free MalE in the presence of MalF-P2 adopts a similar semiopen state hints at the origin of the futile ATP hydrolysis of MalFGK2-E.

Introduction

ATP-binding cassette (ABC)4 transporters are active transporters of substrate that utilize the chemical energy stored in ATP to translocate the substrate across cellular membranes (1). Most ABC transporters are importers of substrate in bacteria and include a substrate-binding protein, two integral membrane components with low sequential homology, and two conserved nucleotide-binding domains (2). One of the best studied systems is the maltose transporter MalFGK2-E of Escherichia coli/Salmonella that consists of the periplasmic maltose-binding protein MalE, the two integral cytosolic membrane proteins MalF and MalG, and two copies of the nucleotide-binding domains MalK (3). A multitude of x-ray structures exists of the maltose transporter in its resting state, a catalytic-intermediate state and most recently in a pretranslocational state (4–7). It has been shown that the rigid-body rotation of the nucleotide-binding domains is confined to ATP binding and hydrolysis, which coincides with the conformational changes during substrate transport (7–9). From structural information together with biochemical data, a model for the substrate translocation process has been developed for the ABC import system, the alternating-access model (10). An adaptation of this model to the MalFGK2-E system is shown in Fig. 1. To date it is not known how the translocation process is initiated. Especially the highly dynamic region of the periplasmic side of the transporter in interaction with the substrate-binding protein MalE has eluded high-resolution information. In a recent study we described the second periplasmic loop P2 of MalF as a key player in the recognition of substrate via MalE (11). In this study we show that MalF-P2 not only is responsible for substrate recognition but also directly involved in activation of the MalFGK2-E complex by inducing structural changes in maltose-bound MalE.

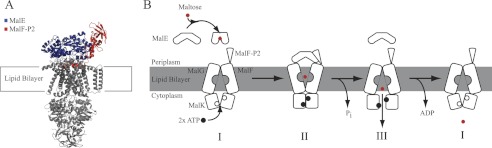

FIGURE 1.

Substrate transport model for MalFGK2-E. A, crystal structures of MalFGK2-E (6), MalE, and MalF-P2 color-coded in blue and red, respectively. B, transport model for ABC importer systems adapted to the MalFGK2-E system (10). The model contains three distinct steps. First, ATP is loaded into the MalK dimer, and the interface closes upon binding of substrate-loaded MalE at the periplasmic surface (II). Upon ATP hydrolysis substrate is released into the binding pocket of MalG,F and is transported into the cytoplasm (III). After substrate transport, ADP is released, and the transporter goes back to its resting-state (I). Amplitudes of motion for the TMDs are exaggerated in the representation to highlight changes. A TMD (MalF,G) rotation from the inward to the outward conformation was determined to be on the order of 22 ° (4). Fig. adapted from Locher (10).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sample Preparation

Unlabeled MalF-P2 and MalE were prepared as described (11) in LB medium. Uniformly 15N,2H-labeled MalE (U-15N,2H MalE) was expressed using M9 minimal medium supplemented with D2O and 15NH4Cl as the sole deuterium and nitrogen source. Protein was stored in 20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl at −80 °C for later use.

NMR Experiments and Analysis

Experiments were performed with 0.3–1 mm U-15N,2H MalE samples at 310 K in 20 mm NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, in 95% H2O/5% D2O. Data were recorded using Bruker 750 and 900 MHz spectrometers (Bruker Biospin, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with triple resonance cryogenic probes. Resonance assignments were transferred from earlier studies (12, 13).

NMR experiments were carried out at equimolar ratio of U-15N,2H MalE and maltose, 500 μm. To investigate the MalE/MalF-P2 complex, a molar ratio of 1:1.2 of U-15N,2H MalE (500 μm) and nonlabeled MalF-P2 (600 μm) in the absence and presence of 500 μm maltose was employed. A 20% molar excess of MalF-P2 was used to assure that the MalE/MalF-P2 complex was observed. The interaction of MalE to maltose in the presence and absence of MalF-P2 was observed by mapping chemical shift perturbations of backbone resonances. Residual dipolar coupling measurements were carried out using liquid-crystalline Pf1 filamentous phages (Profos AG) as an alignment medium. A concentration of 7 mg/ml Pf1 yielded a residual quadrupolar coupling of the D2O resonance of 7.8 Hz (14, 15). 1H-15N HSQC and 1H-15N HSQC TROSY experiments were recorded to obtain the 15N J-coupling for the alignment tensor analysis of MalE (16).

RDC experiments were measured for the maltose-bound MalE in the absence (reference experiment) and presence of MalF-P2, and for the MalE/MalF-P2 complex in the absence of maltose. RDC values were fitted in Module v1.0 (17) using the structures of substrate-free MalE (PDB ID code 1PEB), substrate-bound MalE (PDB ID code 1MPD), and MalE as observed in the MaFGK2-E complex (PDB ID code 2R6G). Alignment tensors of the N- and C-terminal domains of MalE in the presence and absence of maltose were fitted with a 100-step Monte Carlo error analysis in Module (17). Consequently, the alignment tensor was fitted again using a common alignment frame. After rigid-body modulation to obtain the orientations of the N- and C-terminal domains in the common alignment frame, the resulting MalE structure in the MalE/MalF-P2 complex was acquired (17). The procedure was carried out for MalE in the presence and absence of maltose.

Boundaries of the N- and C-terminal domains were set accordingly, N: residues 1–110; 260–313 and C: residues 115–257; 335–370, and the linking domain: residues 314–334. The linking domain was omitted from the RDC fitting. Resulting PDBs and visualization of alignment tensors from the rigid-body modeling were derived from Module v1.0 (17).

Solvent-PRE Measurements

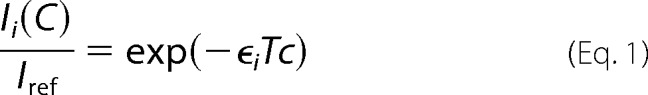

Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) experiments were obtained by quantification of the HSQC peak intensities for maltose-bound MalE in the presence and absence of MalF-P2. Solvent-PREs were measured by the addition of chelated Gd3+ (OmniScan) to the sample buffer. Stock solutions of Gd3+ were prepared in sample buffer, which was titrated into the protein solution to yield a concentration of 0.5–50 mm Gd3+. Spectra were acquired with 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 5.0, 10.0, 25.0, and 50.0 mm Gd3+. Concentration-dependent HSQC cross-peak intensities Ii were fitted according to Equation 1,

|

and evaluated according to Hilty et al. (18). ϵi, T, and c refer to the relative solvation rate, the INEPT, delay and the Gd3+ concentration, respectively. No significant changes in 15N line widths of MalE due to chemical exchange upon addition of MalF-P2 in the presence and absence of maltose were observed.

All NMR spectra were processed with TopSpin v2.0 (Bruker Biospin, Karlsruhe, Germany) and analyzed with CCPN analysis v2.4 (19). Solvent PREs and correlation factors for RDCs were fitted using Prism v5.0b (GraphPad). RDC alignment tensor fitting and rigid-body modulations were accomplished in Module v1.0 (17).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Experiments

MalE and MalF-P2 ITC samples were extensively dialyzed overnight at 7 °C (Spectral/Por, Spectrum Laboratories) either separately or mixed at a 1:1.2 (MalE:MalF-P2) molar ratio, with concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 1 mm in 20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, with light stirring. Maltose stocks were prepared from the dialysis buffer at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 2 mm. MalE, MalF-P2, MalE/MalF-P2, and maltose samples were filtered and degassed before insertion to the injection syringe and calorimeter cell.

High-sensitivity microcalorimetry was performed on a VP-ITC instrument (MicroCal). Experiments of maltose binding to MalE were performed at 5 °C with either MalE only or a 1:1.2 molar ratio of MalE:MalF-P2 in the calorimeter cell and maltose solution in the injection syringe. Time spacings between injections were chosen long enough to allow for complete reequilibration (600 s). Typically, 20–40 injections were performed. Base-line subtraction and peak integration were performed as described by the manufacturer (MicroCal) with Origin 5.0 (OriginLab). Association curves were fitted with a nonlinear one-site binding model, yielding the binding constant and molar ratio of the interaction.

Determination of the dissociation constant for binding of maltose to MalE was performed employing 40 μm MalE in the calorimetry cell and 500 μm maltose in the syringe. For measurement of binding of maltose to the MalE/MalF-P2 complex a solution of 75 μm MalE and 90 mm MalF-P2 was provided in the calorimetry cell and a 500 μm maltose solution in the syringe. Control experiments were performed to find out whether maltose interacts with MalF-P2 alone. Experiments were performed with MalF-P2 (50 μm) in the calorimetry cell and a 500 μm maltose solution in the syringe. No interaction could be detected between maltose and MalF-P2 alone.

Maltose Binding Assay

Binding of [14C]maltose to MalE in the absence and presence of MalF-P2 was monitored by a filtration assay according to Richarme and Kepes (20). Briefly, purified MalE (2.5 μm) was incubated with [14C]maltose (12 μm) in the absence or presence of MalF-P2 (2.5 and 5 μm, respectively) in 20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl at 25 °C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 2 ml of ice-cold saturated (NH4)2SO4, and the mixture was immediately passed through a nitrocellulose filter (0.45-μm pore size). After two washes with 5 ml of the (NH4)2SO4 solution followed by 5 ml of distilled water, the radioactivity retained on the filters was determined in a liquid scintillation counter.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

The MalFGK2-E crystal structure (PDB ID code 2R6G) was taken as the starting point to perform a 50-ns molecular dynamics simulation in GROMACS using the GROMOS force field (ffG53a6) (21) of MalE and MalF-P2. The proteins were placed into a triclinic box. The simulations were done under physiological conditions. For this purpose the proteins and the complex structure were calculated in a 0.1 m NaCl (i.e. ∼15,600 H2O molecules, 45 Na+ and 33 Cl− ions, respectively) solution at 310 K and periodic boundary conditions for the box. Short-range nonbonded interactions were calculated with the Cut-off Lennard-Jones potential up to a distance of 1.2 nm between the interacting atoms. For long-range electrostatic interactions the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) option was used with a grid spacing of 0.12 nm. The bond length of a heavy atom (C, N, O) to an H-atom in protein or water was constrained using a LINCS and SETTLE algorithm, respectively. Every simulation ensemble was energy minimized in a two-step minimization strategy. In a first step steepest descent and in a second a conjugate gradient minimizing routine were used. After equilibration over a period of 500 ps using a positional restraint of 1000 kJmol−1 nm−2 on the backbone of the two proteins molecule, a free simulation was performed for a period of 50 ns for the MalE/MalF-P2 complex. The temperature and pressure (1 bar) were controlled using the Berendsen coupling with a relaxation time of 0.1 ps for temperature and 1 ps for pressure. During the course of the simulation, the actual frame was stored every 5 ps. Visualization of trajectories and arrangement of figures was made with VMD (22).

RESULTS

In an earlier report it was shown that the periplasmic loop P2 of MalF in the MalFGK2 transporter folds independently in solution and can interact with MalE in the presence and absence of maltose (11). Here, the interaction of MalE to MalF-P2 was investigated.

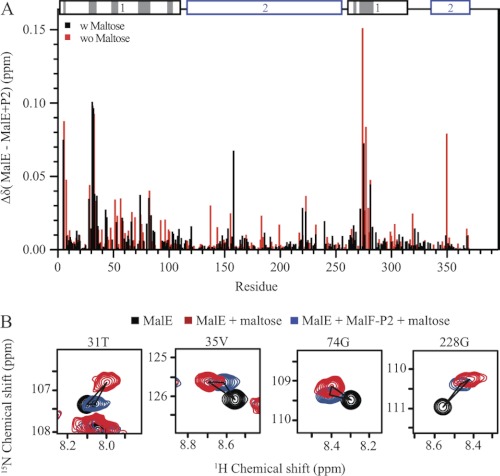

NMR Titration of MalF-P2 to U-15N,2H MalE in Presence and Absence of Maltose

1H-15N correlation spectra were recorded with 500 μm U-15N,2H MalE and 600 μm unlabeled MalF-P2 in the presence and absence of 500 μm maltose. Chemical shift changes are mapped onto the primary sequence in Fig. 2. The largest chemical shift changes (Δδ >0.05 ppm) are located predominantly in the N-terminal lobe of MalE. Surprisingly small but significant chemical shift changes are observed along the full primary sequence of MalE (<0.02 ppm), regardless of proximity to the substrate (Fig. 2). Spectra of maltose-bound and maltose-free MalE were superimposed with spectra of maltose-bound MalE in the presence of MalF-P2. A large number of MalE resonances from the MalE/MalF-P2/maltose complex spectra show chemical shifts that are distinct to either the maltose-free or the maltose-bound state of MalE. The cross-peaks are also not positioned in between the open and closed state of MalE (Fig. 2). Fast exchange between the two states can therefore be excluded. The distinct chemical shifts rather hint at a third conformational state of MalE when bound to MalF-P2.

FIGURE 2.

Chemical shift titration experiments of MalE and MalF-P2 in the presence and absence of maltose. A, resonance-specific 1H-15N chemical shift changes upon titration of MalF-P2 to U-15N,2H MalE, in the presence (black) and absence (red) of maltose. Two distinct binding regions in the N-terminal domain of MalE are observed. These regions match the contacts seen in the crystal structure of MalFGK2-E (PDB ID code 2R6G) (6). MalE and MalF-P2 contacts (with Δ(N, C, O) <5 Å) in the MalFGK2-E crystal structure are highlighted in gray on the primary sequence (top). In addition, small chemical shift changes are observed for residues not directly involved in the interaction. B, 1H,15N correlation spectra for selected residues, not located in the binding interface. Resonances are color coded, MalE (black), MalE/maltose (blue), and MalE/MalF-P2/maltose (red). Chemical shift analysis shows resonances distinct from the maltose-bound and maltose-free MalE, implying that MalE in the presence of MalF-P2 adopts a different conformation.

Effect of Maltose Binding to MalE after Complex Formation with MalF-P2

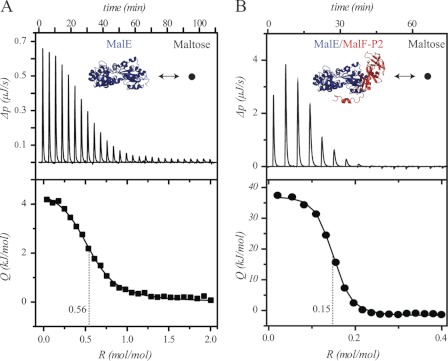

ITC experiments were performed to evaluate whether MalE can bind maltose when complexed to MalF-P2. Reference ITC experiments of maltose binding to MalE show values similar to those earlier reported (23). When titrating maltose into the measurement cell filled with a 1:1.2 molar ratio of MalE:MalF-P2, the fitted binding curve yields comparable binding affinity. However, the stoichiometry, R, is reduced to a fourth, indicating a lower activity of MalE relative to the reference experiment (Fig. 3) and indicating that release and rebinding of maltose to MalE only occur at negligible rates compared with the uncomplexed state.

FIGURE 3.

ITC experiments. A, maltose titrated into MalE; KD = 2.18 ± 0.091 μm, ΔH = 4.467 ± 0.037 kJ, ΔS = 41.8 J/K. B, maltose titrated into MalE and MalF-P2 (1:1.2 molar ratio); KD = 0.121 ± 0.043 μm, ΔH = 37.59 ± 0.849 kJ, ΔS = 166 J/K. All experiments were carried out at 5 °C. In the presence of MalF-P2 the apparent stoichiometry is reduced to ∼25%, indicating that one quarter of all MalE/MalF-P2 complexes are able to coordinate a maltose molecule.

To evaluate whether MalF-P2 can stimulate release of maltose from maltose-bound MalE, radioactive maltose precipitation experiments were performed. Maltose-bound MalE was precipitated in the absence or presence of either equimolar or 2-fold excess of MalF-P2 in solution. Radioactive counts were measured before and after precipitation of proteins in solution, and all experiments were performed in duplicate (Fig. 4). No significant difference in maltose counts was found for the maltose-bound MalE in the absence or presence of MalF-P2 in solution, implying that maltose is maintained bound in the substrate-pocket of MalE in the presence of MalF-P2.

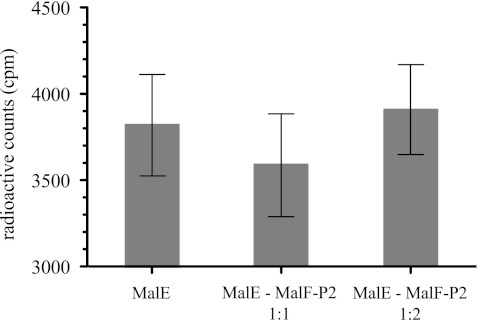

FIGURE 4.

Radioactive maltose precipitation experiments. All experiments were performed with equimolar amounts of MalE and maltose in the presence or absence of MalF-P2 at a 1:1 or 1:2 molar ratio. Radioactive counts from filter assays (20) of [14C]maltose were measured by a liquid scintillation counter. Experiments were performed in duplicate for each sample. No significant difference of free maltose in the supernatant is observed after precipitation of the protein.

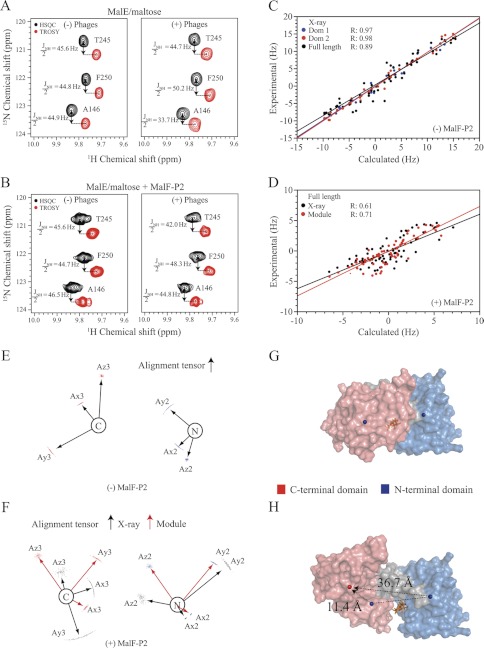

RDC Measurements Elucidate Structural Changes of MalE

HN-N RDCs were extracted from spectra of maltose-bound MalE in the absence and presence of MalF-P2, 182 and 131 respectively. RDCs were analyzed employing the substrate-free, the maltose-bound MalE and the MalE structure in a catalytic intermediate state of MalFGK2-E (PDB ID codes 1PEB, 1MPD, and 2R6G, respectively). Further, the structures were separated into the N-terminal (residues 1–110; 260–313) and C-terminal (residues 115–257; 335–370) domains to further evaluate the relative orientation of the two domains to one another. The linker regions between the N- and C-terminal domains were omitted in the analysis. Reference RDCs of MalE/maltose show a high correlation coefficient for the individual N- and C-terminal domains, R ∼ 0.97, and their relative orientation, r = 0.89 (Table 1), with respect to the x-ray structure (PDB ID code 1MPD). HN-N RDCs were then extracted from the MalE/MalF-P2/maltose complex. The extracted RDCs were fitted to the maltose-free and maltose-bound structures of MalE as well as the MalE structure from the MalFGK2-E vanadate-trapped intermediate state (PDB ID codes 1PEB, 1MPD, and 2R6G, respectively) (Table 1). A correlation coefficient of r = 0.65, 0.76, and 0.61 for the N- and C-terminal domain and the full-length structure, respectively, is observed. The lower correlation coefficient for the individual N- and C-terminal domains can be directly interpreted as a consequence of a conformational rearrangement in the binding interface and the C-terminal domain. Minor structural changes are corroborated by chemical shift changes in the C-terminal domain in the HSQC titration experiments (Fig. 2). The reduced correlation coefficient for the full structure, relative to the individual domains, shows that the relative orientation of the individual domains deviates from all of the previously solved x-ray structures (PDB ID codes 1PEB, 1MPD, and 2R6G).

TABLE 1.

R values of fitted RDC data of substrate-bound MalE/MalF-P2

Correlation factors are calculated with respect to the full structure, the two individual domains for substrate-free and -bound MalE, and the intermediate state in the MalFGK2-E complex. A good correlation is observed for the full-length structure and the individual domains in the reference experiment (MalE/maltose). Fitted HN-N RDCs from the MalE/MalF-P2/maltose complex to known structures of MalE show a decreased correlation factor for the individual domains and the full-length structure. MalE/MalF-P2/maltose-derived RDCs show a better correlation with respect to the full-length structure of MalE with corrected relative orientations of the individual domains by Module (17). A similar dependence is observed for RDCs derived from MalE/MalF-P2 in the absence of maltose.

| Complex | Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Full-length |

|---|---|---|---|

| HN-N RDC MalE/maltose | |||

| MalE with maltose (PDB: 1MPD) | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.89 |

| MalE without maltose (PDB: 1PEB) | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.63 |

| HN-N RDC MalE/MalF-P2/maltose | |||

| MalE with maltose (PDB: 1MPD) | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.61 |

| MalE without maltose (PDB: 1PEB) | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.56 |

| MalE (MalFGK2-E) (PDB: 2r6g) | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.47 |

| MalE/MalF-P2/maltose (Module) | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.71 |

| HN-N RDC MalE/MalF-P2 | |||

| MalE without maltose (PDB: 1PEB) | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.63 |

| MalE/MalF-P2/maltose (Module) | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.68 |

Fitted alignment tensors from the MalE/MalF-P2/maltose complex to the individual domains used a 100-step Monte Carlo analysis in Module v1.0 (17) yielding a good convergence. The obtained alignment tensors for the individual N- and C-terminal domains are on the same order of magnitude, which allows for rigid-body modulation (Fig. 5) (17). The alignment tensors from the N- and C-terminal domains of MalE/MalF-P2/maltose are then set to a common alignment frame and allowed to undergo rigid-body rotations to accommodate the common alignment frame. MalE/MalF-P2/maltose-derived RDCs were then fitted to the resulting full-length structure after rigid-body modulation. This yields the relative orientation of the two domains in the MalE/MalF-P2/maltose complex (Fig. 5). An increase in the correlation factor is now observed (r = 0.71), indicating that an improved relative domain orientation is found (Table 1). The reorientation of the relative domains to each other results in exposure of the binding pocket of MalE to the solvent in the MalE/MalF-P2/maltose complex.

FIGURE 5.

RDC experiments with maltose-bound U-15N,2H MalE in the presence and absence of MalF-P2. A and B, HSQC and TROSY spectra yielding the JNH/2-coupling for selected residues in isotropic (left) and anisotropic (right) buffer for MalE/maltose and MalE/MalF-P2/maltose, respectively. C, experimental and calculated residual dipolar couplings for MalE/maltose and their correlation factors, using the N- (blue) or C-terminal (red) domain or full-length (black) crystal structure of maltose-bound MalE (PDB ID code 1MPD). D, experimental and calculated residual dipolar couplings for MalE/MalF-P2/maltose with respect to the full-length MalE/maltose crystal structure (black) and subsequently to the Module (17)-derived MalE structure. Module uses RDC-derived alignment tensors for individual domains and applies rigid-body modulation to optimize their relative domain orientation. The increased correlation factor in the Module-derived MalE structure from MalE/MalF-P2/maltose RDCs shows that the relative orientation of the individual domains changes in the presence of MalF-P2. E, alignment tensors for the N- and C-terminal domains from MalE/maltose obtained from residual dipolar couplings. F, alignment tensors of the N- and C-terminal domains fitted to the MalE/maltose crystal structure (black) and alignment tensors after correction of the relative domain orientation in Module (red). G and H, surface representation of the MalE/maltose crystal structure and the Module-obtained MalE in the MalE/MalF-P2/maltose complex. The N- and C-terminal domains and their center-of-masses are indicated as blue spheres for the MalE/maltose structure (G). The corrected center-of-mass C-terminal domain is represented by a red sphere (H). Changes in center-of-mass distances from the reference domain orientation to the corrected relative orientation are marked with black dashed lines. Maltose is represented in stick model (orange) in the binding pocket.

Moreover, RDCs extracted for MalE in the MalE/MalF-P2 complex in the absence of maltose yield a similar relative orientation of the N- and C-terminal domains as found in the MalE/MalF-P2/maltose complex. Thus, the domain reorientation of MalE in complex with MalF-P2 seems independent of the substrate.

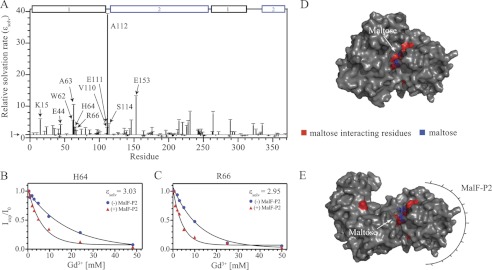

Solvent Exposure of Binding Cleft of MalE by Solvent-PRE Measurements

To assess the solvent accessibility of the binding cleft in maltose-bound MalE qualitatively, in the presence and absence of MalF-P2 (Table 2), solvent-PRE measurements with chelated Gd3+ (OmniScan) in solution were performed. Gd3+ is a paramagnetic ion that drastically increases the relaxation rates of hydrogen atoms in its vicinity. Relaxation rates were measured via 1H-15N HSQC experiments recorded with increasing concentrations of Gd3+ (0.5–50 mm) (Fig. 6). MalE amide 1H,15N cross-peak intensities were fitted with respect to the Gd3+ concentration. In principle, a reduced solvent accessibility is expected for residues in MalE that directly interact with MalF-P2. Residues not interacting with MalF-P2 should not experience any changes. However, the opposite effect was observed in our experiments. We found strongly increased solvation rates for residues Lys15, Glu61, Trp62, Ala63, Arg66, Val110, Glu111, Ala112, and Glu153, located directly in the substrate-binding pocket. As these residues are not directly involved in MalF-P2 binding, a change in the solvent accessibility of the binding cleft must occur. This is corroborated by the conformational changes in the N- and C-terminal domain of MalE, as seen in the changes of the RDC values.

TABLE 2.

Ratio of solvent-PRE relaxation rates for substrate-bound MalE in presence and absence of MalF-P2

Relaxation rates of residues lining the binding pocket and/or directly associated with substrate binding were extracted and compared relatively with each other. A >5-fold increase in relaxation rates of residues located in the vicinity of the maltose-binding pocket is observed after addition of MalF-P2.

| Residue | ϵMalE/MalF-P2/ϵMalE | Residue | ϵMalE/MalF-P2/ϵMalE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lys15 | 5.78 ± 0.28 | Val110 | 1.02 ± 0.43 |

| Glu44 | 4.02 ± 0.20 | Glu111 | 2.96 ± 0.38 |

| Trp62 | 5.33 ± 0.30 | Ala112 | 38.9 ± 0.40 |

| Ala63 | 10.3 ± 0.28 | Ser114 | 4.22 ± 0.31 |

| His64 | 3.03 ± 0.29 | Glu153 | 13.0 ± 0.34 |

| Arg66 | 2.95 ± 0.54 |

FIGURE 6.

Residue-specific solvent accessibility of MalE in the absence and presence of MalF-P2. A, relative solvent accessibility rates ϵsolv determined by solvent-PRE measurements. Conformational changes due to the complex formation of MalE/MalF-P2/maltose induce small changes of solvation rates over the full primary sequence. Residues in the vicinity of the maltose-binding pocket (marked with arrows) show similar or significantly higher solvation ratios in the presence of MalF-P2. B and C, relaxation rates for residues His64 and Arg66, interacting directly with maltose, in the absence (blue spheres) and presence (red triangles) of MalF-P2, respectively. D and E, surface representations of the MalE/maltose structures in the absence (PDB ID code 1MPD) and presence of MalF-P2 (Module-derived), respectively. Maltose (blue stick model) and interacting residues (red) are labeled in the structures.

Surface representations of the MalE/maltose structures, in the absence (PDB ID code 1PEB) and presence of MalF-P2 (Module-derived), highlight the increased solvent exposure of the binding pocket of the MalE/MalF-P2 complex. The increased solvent-accessibility of specific amino acids in the substrate-binding pocket is readily appreciated (Fig. 6).

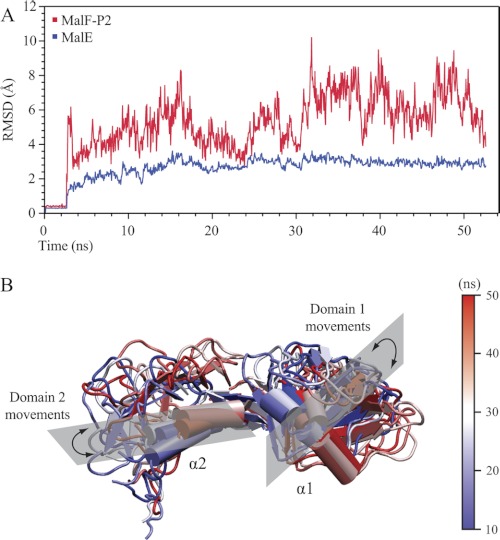

Molecular Dynamics Simulation of MalE/MalF-P2 Complex

To further assess the MalE and MalF-P2 binding interface a GROMACS molecular dynamics simulation (21) was performed. As starting points for the simulated annealing the crystal structures of MalE and MalF-P2 in the MalFGK2 complex were used. The full-length sequence of MalE was calculated for each simulation ensemble. The C-terminal part of MalF-P2, residues 266–275, was discarded as earlier data show no interaction between MalE and MalF-P2 in this region (11). Further, the C-terminal α-helix α3 cannot fold up independently in solution (24). Root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) trajectories were plotted for MalE, MalF-P2, and the MalF-P2/MalE complex (Fig. 7). The molecular dynamics trajectory shows that MalE maintains its initial structure during the course of the simulation. Dynamics is only observed for surface-exposed loops in the C-terminal lobe of MalE. MalE thus behaves as a rigid body with a r.m.s.d. amplitude of 3 Å throughout the simulation. In contrast to MalE, MalF-P2 shows large dynamic variations throughout the simulation. The backbone r.m.s.d. initially rises to accommodate the binding surface to MalE properly. After 25 ns, MalF-P2 is properly positioned on the binding surface of MalE (Fig. 7). The second half of the simulation yields a higher r.m.s.d. trace, as the two domains of MalF-P2 are dynamic in their interaction with MalE. From NMR interaction studies it is known that the interaction between MalF-P2 and MalE particularly involves the two α-helices α1 and α2 (11) (Fig. 8). These α-helices are located in each of the two domains of MalF-P2. During the simulated annealing both domains of MalF-P2 are reorienting to accommodate MalE. After 40–50 ns of the simulated annealing α-helix α1 in domain 1 reorients and moves toward domain 2 of MalF-P2 on the binding surface of MalE (Fig. 7). Whereas the angle between the α-helices at the beginning of the simulation is on the order of 30°, the two domains are oriented almost perpendicular to each other at the end of the trajectory.

FIGURE 7.

50-ns molecular dynamics simulation of the MalE/MalF-P2 complex. A, backbone r.m.s.d. trajectory of the MalF-P2/MalE complex. The first 2.5 ns comprise a waterbox refinement before starting the simulated annealing. The backbone r.m.s.d. trajectory of MalE is represented in blue and MalF-P2 in red. MalE keeps a rigid structure with little dynamics (r.m.s.d. ∼ 3 Å) in the course of the full simulation. A much larger dynamic behavior is observed for MalF-P2 (r.m.s.d. = 4–9 Å). MalF-P2 undergoes large conformational rearrangements initially until the correct conformation with respect to MalE is found. B, representations of MalF-P2 at different time steps of the simulation. Structures are shown at every 10 ns of the simulation with colors shifting from blue to white to red. The two α-helices of MalF-P2, α1 and α2, make up the main interaction with MalE (11). During the course of the simulation they undergo large rearrangements while still maintaining the interaction to MalE.

FIGURE 8.

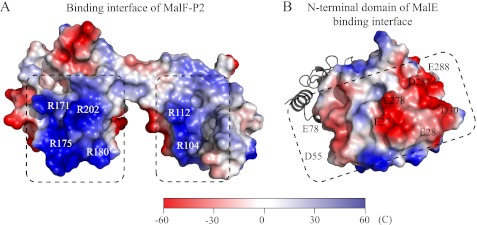

Electrostatic surface representation of the MalE/MalF-P2 binding interface. Highly charged patches with complementary charges (dashed boxes) are located directly at the binding interface of the N-terminal lobe of MalE and the two domains of MalF-P2. Important residues are indicated in MalF-P2 (A) and MalE (B), respectively.

A second 50-ns molecular dynamics simulation was performed to monitor the r.m.s.d. traces from the respective calculations. The two calculations converged and showed similar dependence on the dynamic behavior of the MalF-P2/MalE interaction.

DISCUSSION

In an earlier report we have demonstrated that the periplasmic loop P2 of MalF acts as a receptor that recognizes MalE (11). Here we extend this study and show that MalF-P2 induces an activated conformational state of MalE that precedes substrate transport in MalFGK2. Although x-ray structures have been able to give valuable snapshots of the maltose transporter in three different conformational states (4–6), none could so far explain how the initial activation of MalFGK2 at the periplasmic side is accomplished. A recent molecular dynamics study hints at the dynamic behavior of the association process, but experimental data are so far missing (25).

We found that substrate recognition is mediated by MalF-P2, which causes an alternative active conformation of the two domains of MalE in the presence of MalF-P2. From these new data we propose an adapted activation mechanism for the existing transport model (26) which is represented in (Fig. 9). Here, MalF-P2 first acts as a receptor for MalE (Fig. 9, Ia). In the presence of MalF-P2, a conformational change of MalE is induced. The substrate becomes solvent-exposed in the binding pocket, and concomitantly space is provided for insertion of the periplasmic loop P3 of MalG (Fig. 9, Ib). In the x-ray structure (6), the loop MalG-P3 is fully inserted into the binding pocket, effectively “scooping out” the substrate. So far, however, it is not understood how the MalG-P3 loop gets inserted into the binding cleft of MalE. MalE binds maltose with micromolar affinity (23) and creates a highly stable complex burying the substrate between the two domains (20). In the substrate-bound conformation, solvent does not have access to the binding cleft (23). Conformational changes of MalE triggered by MalF-P2 allow MalG-P3 either to interact directly with the substrate or to insert into the binding pocket, stabilizing the complex during the substrate import cycle (Fig. 9, Ic). ATP hydrolysis drives substrate transport, and much effort has been made to identify the interactions that cause hydrolysis (26). In an earlier study by Grote et al. (27) it was demonstrated that MalF-P2 signals across the lipid bilayer to the cytosolic part of MalFGK2, effectively communicating reciprocally over the cellular membrane during the substrate transport cycle (Fig. 9, Ic).

FIGURE 9.

Activation model of substrate transport in MalFGK2. Based on the alternative-access model (Fig. 1), three additional intermediates are proposed to account for our findings. Ia, MalK subunits in an open state containing bound ATP. Substrate recognition is mediated through binding of MalF-P2. Ib, conformational change of MalE, exposing the substrate to the solvent and allowing insertion of MalG-P3 into the binding pocket (dashed lines MalE). Ic, substrate availability signaled reciprocally across the membrane inducing a closure of the MalK dimer. Subsequently, the transmembrane MalF/G domains switch from an inward-facing to an outward-facing conformation allowing the released maltose to bind into the binding pocket of the transmembrane domains of MalF/G. Amplitudes of motion for the TMDs are exaggerated to highlight changes. A TMD rotation from the inward to the outward conformation was determined to be on the order of 22 ° (4).

The MalE/MalF-P2 interaction is mediated through complementary electrostatic forces (Fig. 8). MalE has two large negatively charged patches at the binding interface to MalF-P2. Complementarily, MalF-P2 has one positively charged patch at each of its two domains around α-helices α1 and α2. In the molecular dynamics simulation, the two domains of MalF-P2 turn out to be highly dynamic. We speculate that the complementary electrostatic patches stabilize the complex, inducing structural changes in MalE, which are required to dock to the MalFGK2-E complex. The molecular dynamics simulations suggest that the interaction of MalF-P2 and MalE is highly dynamic with MalF-P2 “gliding” on the interaction surface of MalE. The dynamics is a necessity to facilitate the binding of MalE when docking to the transmembrane proteins MalF/G. Dynamics enables different kinds of binding modes of MalF-P2 with respect to MalE, which reflect the different states during substrate transport in the MalFGK2-E complex.

As shown here, MalF-P2 also affects the substrate-free MalE, inducing the activated conformation of MalE. This activated state would enable the insertion of MalG-P3 and the stabilization of the MalFGK2-E complex in the absence of substrate. In turn, this would cause ATP hydrolysis and explain the observed futile ATP hydrolysis of the transporter in the absence of substrate (28, 29).

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Oksana Krylova for help with the experimental setup of ITC measurements and fruitful discussions.

This work was supported by the Center for Integrated Protein Science Munich.

- ABC

- ATP-binding cassette

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single-quantum coherence

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- PRE

- paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

- RDC

- residual dipolar coupling

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

- TROSY

- transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eitinger T., Rodionov D. A., Grote M., Schneider E. (2011) Canonical and ECF-type ATP-binding cassette importers in prokaryotes: diversity in modular organization and cellular functions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 3–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Higgins C. F. (1992) ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 8, 67–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bordignon E., Grote M., Schneider E. (2010) The maltose ATP-binding cassette transporter in the 21st century: towards a structural dynamic perspective on its mode of action. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 1354–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khare D., Oldham M. L., Orelle C., Davidson A. L., Chen J. (2009) Alternating access in maltose transporter mediated by rigid-body rotations. Mol. Cell 33, 528–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oldham M. L., Chen J. (2011) Crystal structure of the maltose transporter in a pretranslocation intermediate state. Science 332, 1202–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oldham M. L., Khare D., Quiocho F. A., Davidson A. L., Chen J. (2007) Crystal structure of a catalytic intermediate of the maltose transporter. Nature 450, 515–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oldham M. L., Chen J. (2011) Snapshots of the maltose transporter during ATP hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15152–15156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones P. M., O'Mara M. L., George A. M. (2009) ABC transporters: a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. Trends Biochem. Sci. 34, 520–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oswald C., Holland I. B., Schmitt L. (2006) The motor domains of ABC-transporters - What can structures tell us? Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmakol. 372, 385–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Locher K. P. (2009) Review: structure and mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporters. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 239–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jacso T., Grote M., Daus M. L., Schmieder P., Keller S., Schneider E., Reif B. (2009) Periplasmic loop P2 of the MalF subunit of the maltose ATP-binding cassette transporter is sufficient to bind the maltose-binding protein MalE. Biochemistry 48, 2216–2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Evenäs J., Tugarinov V., Skrynnikov N. R., Goto N. K., Muhandiram R., Kay L. E. (2001) Ligand-induced structural changes to maltodextrin-binding protein as studied by solution NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 309, 961–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gardner K. H., Zhang X. C., Gehring K., Kay L. E. (1998) Solution NMR studies of a 42 kDa Escherichia coli maltose binding protein beta-cyclodextrin complex: Chemical shift assignments and analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 11738–11748 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prestegard J. H., al-Hashimi H. M., Tolman J. R. (2000) NMR structures of biomolecules using field oriented media and residual dipolar couplings. Q. Rev. Biophys. 33, 371–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tjandra N., Bax A. (1997) Direct measurement of distances and angles in biomolecules by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. Science 278, 1111–1114; erratum 1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pervushin K., Riek R., Wider G., Wüthrich K. (1997) Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 23, 12366–12371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dosset P., Hus J. C., Marion D., Blackledge M. (2001) A novel interactive tool for rigid-body modeling of multi-domain macromolecules using residual dipolar couplings. J. Biomol. NMR 20, 223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hilty C., Wider G., Fernández C., Wüthrich K. (2004) Membrane protein-lipid interactions in mixed micelles studied by NMR spectroscopy with the use of paramagnetic reagents. ChemBioChem 5, 467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vranken W. F., Boucher W., Stevens T. J., Fogh R. H., Pajon A., Llinas M., Ulrich E. L., Markley J. L., Ionides J., Laue E. D. (2005) The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins 59, 687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richarme G., Kepes A. (1983) Study of binding protein-ligand interaction by ammonium sulfate-assisted adsorption on cellulose esters filters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 742, 16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Hess B., Groenhof G., Mark A. E., Berendsen H. J. (2005) GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1701–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 14, 33–38, 27–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomson J., Liu Y., Sturtevant J. M., Quiocho F. A. (1998) A thermodynamic study of the binding of linear and cyclic oligosaccharides to the maltodextrin-binding protein of Escherichia coli. Biophys. Chem. 70, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jacso T., Grote M., Schmieder P., Schneider E., Reif B. (2009) NMR assignments of the periplasmic loop P2 of the MalF subunit of the maltose ATP-binding cassette transporter. Biomol. NMR Assign. 3, 21–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bucher D., Grant B. J., McCammon J. A. (2011) Induced fit or conformational selection? The role of the semi-closed state in the maltose binding protein. Biochemistry 50, 10530–10539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Davidson A. L., Dassa E., Orelle C., Chen J. (2008) Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 317–364, table of contents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grote M., Polyhach Y., Jeschke G., Steinhoff H. J., Schneider E., Bordignon E. (2009) Transmembrane signaling in the maltose ABC transporter MalFGK2-E: periplasmic MalF-P2 loop communicates substrate availability to the ATP-bound MalK dimer. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17521–17526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cui J., Qasim S., Davidson A. L. (2010) Uncoupling substrate transport from ATP hydrolysis in the Escherichia coli maltose transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39986–39993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gould A. D., Telmer P. G., Shilton B. H. (2009) Stimulation of the maltose transporter ATPase by unliganded maltose-binding protein. Biochemistry 48, 8051–8061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]