Abstract

Objective

To assess and estimate the personality changes that occurred before and after the 2009 earthquake in L'Aquila and to model the ways that the earthquake affected adolescents according to gender and sport practice. The consequences of earthquakes on psychological health are long lasting for portions of the population, depending on age, gender, social conditions and individual experiences. Sports activities are considered a factor with which to test the overall earthquake impact on individual and social psychological changes in adolescents.

Design

Before and after design.

Setting

Population-based study conducted in L'Aquila, Italy, before and after the 2009 earthquake.

Participants

Before the earthquake, a random sample of 179 adolescent subjects who either practised or did not practise sports (71 vs 108, respectively). After the earthquake, of the original 179 subjects, 149 were assessed a second time.

Primary outcome measure

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—Adolescents (MMPI-A) questionnaire scores, in a supervised environment.

Results

An unbalanced split plot design, at a 0.05 significance level, was carried out using a linear mixed model with quake, sex and sports practice as predictive factors. Although the overall scores indicated no deviant behaviours in the adolescents tested, changes were detected in many individual content scale scores, including depression (A-dep score mean ± SEM: before quake =47.54±0.73; after quake =52.67±0.86) and social discomfort (A-sod score mean ± SEM: before quake =49.91±0.65; after quake =51.72±0.81). The MMPI-A profiles show different impacts of the earthquake on adolescents according to gender and sport practice.

Conclusions

The differences detected in MMPI-A scores raise issues about social policies required to address the psychological changes in adolescents. The current study supports the idea that sport should be considered part of a coping strategy to assist adolescents in dealing with the psychological effects of the earthquakes on their personalities.

Article summary

Article focus

Dimensions of adolescents' well-being after earthquakes and natural disasters.

‘Before and after’ personality assessment in adolescents through a disrupting disaster like an earthquake affecting an urban environment, using sports practice as the main covariate.

Key messages

Sport as a par of a coping strategy to assist adolescents in dealing with the psychological effects of an earthquake on their personalities.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Before and after study, determined by the occurrence of an unpredictable disaster event.

Restriction of cofactors analysis to gender and sports practice.

Design unfit for adjustment for socioeconomic status.

Introduction

On 6 April 2009, the city of L'Aquila in the Abruzzo region of Italy was devastated by an earthquake. The population suffered injuries, destruction and 308 deaths, with 67 000 persons displaced to the Abruzzo coast or living in tents. Consequently, the entire community was impacted in terms of material, social and psychological damages, and security and normalcy was further undermined by frequent aftershocks.

According to studies on the psychological health of seismic victims,1–3 the consequences of earthquakes on psychological health are long lasting for portions of the population, depending on age, gender, social conditions and individual experiences.4 Earthquakes occur without warning and give the population no opportunity to make psychological adjustments to deal with the calamity, especially in young people.5 The lack of predictability, the reminders of the destruction and the need to move because of destroyed homes may all result in serious mental health issues, for example, by lessening or exacerbating the emotional reactions associated with the trauma.6

Several previous studies addressed specific mental disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)7 or other dimensions of people's well-being after loss determined by earthquake.8 Given the random nature of seismic activity, these studies were not able to perform a pairwise comparison pre- and post-event. Such comparisons would be useful in developing both collective and individual impact assessments9 for determining appropriate interventions.10

Sports activities can be considered a rich context for the construction of personality and may be able to alleviate symptoms of PTSDs, making them a reasonable factor with which to test the overall earthquake impact on individual and social psychological changes in adolescents. However, the literature suggests that more research is required to assess the effectiveness of sports and games in alleviating symptoms of PTSD.11

The current study contributes to the understanding of the personality profile changes that occur in adolescents after disruptive events like earthquakes. The study includes sports practice as a covariate in exploiting the content scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—Adolescents (MMPI-A).12–14 Testing began with a cross-sectional survey carried out before the earthquake in the schools of L’Aquila’ district that compared the MMPI-A content scales' scores for the adolescents based on the adolescents' gender and sports practice factors. The cross-sectional original design changed to a longitudinal design after the earthquake, addressing the need for an assessment of the overall effect of the seism on personality in adolescents.15 In addition to measuring the effects of the earthquake on MMPI-A content scales' scores, it was also possible to study the effects of gender and sport practice on the content scales' profiles.

The goal of the current study is to assess and estimate the personality changes that occurred before and after the 2009 earthquake in L'Aquila and to model the ways that the earthquake affected adolescents according to gender and sport practice.

Methods

Subjects

This study took advantage of a prior cross-sectional survey conducted on adolescents (14–18 years old) that addressed the role of sport in preventing deviant behaviours. A comparison was performed between adolescents who usually practised sports and adolescents who did not practise sports. Sports practice was defined as practising at least twice per week for a minimum of 1 h per session. The sample recruitment and questionnaire administration took place during February 2009. Data analysis had not been performed prior to the earthquake, and the investigation was suspended. The participants were contacted again a few months after the earthquake, and the follow-up questionnaires were administered beginning in early January 2010 and concluded in the second half of May 2010. The questionnaires were administered individually by the same professional psychologists who administered the questionnaires before the earthquake, all of whom received specific training on the MMPI-A.16 Adequate matching of the subjects was ensured by the experimenters. Exclusion criteria consisted of protocols with a VRIN T-score greater than 74 (considered inconsistent) and protocols containing more than 30 unanswered items. In the present study, four girls and seven boys were excluded during the first administration of the questionnaire and were removed from further analysis.17

Initially, 179 adolescent subjects (14–18 years old) were randomly sampled from L'Aquila high schools and were administered the MMPI-A questionnaire in a supervised environment. Participants included 87 boys and 92 girls, who either practiced sports (71 total subjects) or did not usually practice sports (108 total subjects). The sample included 60 girls and 48 boys who did not usually practice sports compared with 32 girls and 39 boys who did practice sports. The original research question for the current study was the assessment of the effects of sports practice on the average MMPI-A content scales' scores. After the earthquake, the research goal was redefined to address the assessment of the earthquake's psychological impact on adolescents according to gender and sports practice. Of the original 179 subjects, 149 (70 boys and 79 girls) were assessed a second time. Of the 149 subjects reassessed, 31 boys and 27 girls continued to practice sports activities. In the absence or presence of sport practice, we recorded, respectively, a follow-up loss in the subgroups of 18.75% and 20.52% for boys, and 13.33% and 15.62% for girls. The post-earthquake groups resulted quite comparable in terms of severe earthquake outcomes, such as the proportion of participants experiencing loss of loved ones or friends, relocation and moving to another home/school.

A written informed consent form was provided to the adolescents' parents or to persons possessing parental rights. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration.

Measures

The subjects' responses were assessed using the Italian version of the MMPI-A content scales using the uniform T-score conversions (see table 1),for boys and girls.13 These conversions allowed comparison of scores obtained from different scales so that, on average, it was possible to see changes in the psychological profile of the population examined.

Table 1.

Average uniform T-scores for the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—Adolescents content scales

| A-anx | A-obs | A-dep | A-hea | A-aln | A-biz | A-ang | A-cyn | A-con | A-lse | A-las | A-sod | A-fam | A-sch | A-trt | ||

| Boys | ||||||||||||||||

| Before the quake | ||||||||||||||||

| Sport practice | ||||||||||||||||

| No | Mean | 47.10 | 45.33 | 45.38 | 43.27 | 48.88 | 50.98 | 48.63 | 43.00 | 48.35 | 45.13 | 47.56 | 49.75 | 51.92 | 44.58 | 50.38 |

| SEM | 1.58 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 1.05 | 1.58 | 1.69 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.42 | 1.55 | 1.13 | 1.27 | 1.43 | 1.68 | 1.84 | |

| Yes | Mean | 41.41 | 50.56 | 45.15 | 46.36 | 45.54 | 48.38 | 42.74 | 44.00 | 49.56 | 42.18 | 46.13 | 43.33 | 45.95 | 39.79 | 45.56 |

| SEM | 1.21 | 1.47 | 1.55 | 1.52 | 1.90 | 2.05 | 1.19 | 1.30 | 1.63 | 1.13 | 1.59 | 1.28 | 1.47 | 1.04 | 1.69 | |

| After the quake | ||||||||||||||||

| Sport practice | ||||||||||||||||

| No | Mean | 54.23 | 50.36 | 50.38 | 46.44 | 48.79 | 57.95 | 48.90 | 45.00 | 52.51 | 48.08 | 53.46 | 52.59 | 55.21 | 49.64 | 47.69 |

| SEM | 1.51 | 1.59 | 1.61 | 1.36 | 1.91 | 1.87 | 1.65 | 1.40 | 1.63 | 1.43 | 1.81 | 1.85 | 1.52 | 2.21 | 1.96 | |

| Yes | Mean | 49.58 | 50.52 | 49.48 | 44.29 | 49.10 | 54.61 | 45.13 | 46.39 | 48.00 | 48.13 | 54.42 | 46.55 | 48.84 | 46.29 | 49.84 |

| SEM | 1.77 | 1.77 | 1.52 | 1.33 | 2.30 | 2.01 | 1.27 | 1.93 | 1.75 | 1.80 | 1.97 | 1.50 | 1.47 | 1.46 | 1.82 | |

| Girls | ||||||||||||||||

| Before the quake | ||||||||||||||||

| Sport practice | ||||||||||||||||

| No | Mean | 46.42 | 46.33 | 50.68 | 52.80 | 49.43 | 53.32 | 50.53 | 44.08 | 48.48 | 45.52 | 52.60 | 48.00 | 50.52 | 49.97 | 49.72 |

| SEM | 1.10 | 1.27 | 1.29 | 1.07 | 1.53 | 1.62 | 1.22 | 1.06 | 1.35 | 1.12 | 1.45 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.45 | 1.43 | |

| Yes | Mean | 45.34 | 49.31 | 47.81 | 53.84 | 48.63 | 54.41 | 43.34 | 45.63 | 49.69 | 51.72 | 53.41 | 48.88 | 46.34 | 47.78 | 49.91 |

| SEM | 1.85 | 1.72 | 1.50 | 1.67 | 2.01 | 2.13 | 1.54 | 1.65 | 1.78 | 2.24 | 2.42 | 1.50 | 1.44 | 1.48 | 2.21 | |

| After the quake | ||||||||||||||||

| Sport Practice | ||||||||||||||||

| No | Mean | 56.00 | 52.04 | 55.56 | 57.40 | 49.52 | 53.58 | 55.56 | 45.40 | 50.88 | 45.87 | 55.48 | 52.13 | 54.02 | 49.17 | 49.21 |

| SEM | 1.53 | 1.37 | 1.64 | 1.12 | 1.58 | 1.45 | 1.31 | 1.54 | 1.49 | 1.17 | 1.52 | 1.14 | 1.21 | 1.58 | 1.77 | |

| Yes | Mean | 47.11 | 54.85 | 54.07 | 51.30 | 46.93 | 56.78 | 48.00 | 48.52 | 50.44 | 46.74 | 48.41 | 55.63 | 49.63 | 50.48 | 45.96 |

| SEM | 1.61 | 1.74 | 1.82 | 1.55 | 2.11 | 1.78 | 1.37 | 1.29 | 1.68 | 1.42 | 2.23 | 1.94 | 2.09 | 2.26 | 2.19 | |

A-anx, Anxiety Scale; A-obs, Obsessiveness Scale; A-dep, Depression Scale; A-hea, Health Concerns Scale; A-aln, Alienation Scale; A-biz, Bizarre Mentation Scale; A-ang, Anger Scale; A-cyn, Cynism Scale; A-con, Conduct Problems Scale; A-lse, Low Self-Esteem Scale; A-las, Law Aspirations Scale; A-sod, Social Discomfort Scale; A-fam, Family Problems Scale; A-sch, School Problems Scale; A-trt, Adolescent-Negative Treatment Indicators Scale.

Features and characteristics measured by the MMPI or MMPI-A in the assessment of adolescents serve to describe the teenagers at the moment of testing. Adolescents' test scores often do not provide the types of data necessary to make accurate long-term predictions concerning personality functioning.13

MMPI profile changes are due to frequent behavioural changes over time because of the ‘transient organisation of the personality’ during adolescence.18 According to the transience perspective, such psychometric changes are more attributable to the sensitivity of the MMPI to ongoing change during adolescence than to test structure problems.

Considering that the current study estimates the average effects on profile changes after an earthquake, the use of MMPI-A in the current study is supported by the literature, which indicates that the MMPI/MMPI-A is best used as a means of deriving an overall estimate and current description of adolescents' psychological profiles with no predictive long-range aims.

Statistical analysis

An unbalanced split plot design19 at a 0.05 significance level was carried out using a linear mixed model20 with earthquake, gender and sports practice as predictive factors. There was no need to adjust for earthquake outcome variables, as the two groups resulted strictly similar with regard to the proportions of affected participants. The unbalanced design permitted accounting for the covariance among the repeated measures. The model was run for each of the response variables predicted by content scales that were significant in terms of overall log likelihood ratio (p<0.05). For each content scale, the intraclass correlation was calculated (see table 2), ranging from a minimum for A-cyn (mean =0.86, SEM =0.02) to a maximum for A-hea (mean =0.96, SEM =0.006).

Table 2.

Uniform T-score response linear mixed models for Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—Adolescents content scales*

| Uniform T-score response | Model coefficients |

||||||

| βquake ± SEM (p > |z|) | βsex ± SEM (p > |z|) | βsport ± SEM (p > |z|) | βquake×sport ± SEM (p > |z|) | βquake×sex ± SEM (p > |z|) | β0 ± SEM (p > |z|) | ICC ± SEM | |

| A-anx | 10.24±0.59 (0.00) | −1.15±1.54 (0.46) | −3.42±1.58 (0.03) | −3.44±0.78 (0.00) | 2.13±0.76 (0.005) | 47.23±1.20 (0.00) | 0.89±0.02 |

| A-obs | 9.24±0.45 (0.00) | −0.10±1.56 (0.95) | 4.12±1.60 (0.01) | −2.63±0.60 (0.00) | −2.28±0.59 (0.00) | 45.93±1.22 (0.00) | 0.94±0.01 |

| A-dep | 7.52±0.53 (0.00) | −4.25±1.60 (0.01) | −1.52±1.63 (0.35) | 0.64±0.71 (0.37) | 0.31±0.70 (0.66) | 50.21±1.24 (0.00) | 0.92±0.01 |

| A-hea | 5.97±0.31 (0.00) | −8.72±1.32 (0.00) | 2.08±1.35 (0.12) | −5.48±0.41 (0.00) | 0.06±0.40 (0.89) | 52.44±1.03 (0.00) | 0.96±0.01 |

| A-aln | 1.96±0.62 (0.002) | −1.56±1.88 (0.002) | −2.09±1.92 (0.28) | 1.54±0.83 (0.07) | 2.98±0.81 (0.00) | 49.88±1.46 (0.00) | 0.92±0.01 |

| A-biz | 3.51±0.45 (0.00) | −3.80±1.90 (0.05) | −0.78±1.94 (0.68) | 1.41±0.60 (0.02) | 6.83±0.58 (0.00) | 53.97±1.48 (0.00) | 0.96±0.01 |

| A-ang | 7.09±0.41 (0.00) | −1.38±1.42 (0.33) | −6.52±1.45 (0.00) | 0.70±0.55 (0.20) | −3.41±0.54 (0.00) | 50.30±1.10 (0.00) | 0.94±0.01 |

| A-cyn | 3.46±0.62 (0.00) | −1.34±1.44 (0.35) | 1.20±1.47 (0.41) | 1.14±0.82 (0.17) | 0.94±0.81 (0.24) | 44.20±1.12 (0.00) | 0.87±0.02 |

| A-con | 5.75±0.40 (0.00) | −0.13±1.62 (0.94) | 1.20±1.65 (0.47) | −3.44±0.53 (0.00) | 0.64±0.52 (0.21) | 48.48±1.26 (0.00) | 0.96±0.01 |

| A-lse | 1.25±0.49 (0.01) | −4.02±1.53 (0.01) | 1.55±1.56 (0.32) | −1.12±0.65 (0.08) | 6.71±0.64 (0.00) | 47.13±1.19 (0.00) | 0.93±0.01 |

| A-las | 3.69±0.65 (0.00) | −5.93±1.73 (0.001) | −0.33±1.77 (0.85) | −1.71±0.87 (0.04) | 6.74±0.85 (0.00) | 52.99±1.35 (0.00) | 0.89±0.01 |

| A-sod | 6.46±0.47 (0.00) | −1.15±1.44 (0.43) | −2.83±1.47 (0.05) | 1.83±0.63 (0.004) | −1.62±0.61 (0.01) | 49.29±1.12 (0.00) | 0.92±0.01 |

| A-fam | 5.41±0.42 (0.00) | 0.69±1.46 (0.64) | −5.08±1.49 (0.001) | 0.07±0.56 (0.89) | 1.12±0.55 (0.04) | 50.83±1.14 (0.00) | 0.94±0.01 |

| A-sch | 2.26±0.66 (0.001) | −6.42±1.69 (0.00) | −3.51±1.73 (0.04) | 1.75±0.88 (0.05) | 5.64±0.85 (0.00) | 50.43±1.32 (0.00) | 0.89±0.02 |

| A-trt | 0.55±0.64 (0.39) | −1.33±1.90 (0.48) | −2.35±1.94 (0.23) | 2.14±0.85 (0.01) | 2.89±0.83 (0.001) | 50.60±1.48 (0.00) | 0.92±0.01 |

The likelihood ratio test has p > χ2 <0.00 in all the scales examined.

A-anx, Anxiety Scale; A-obs, Obsessiveness Scale; A-dep, Depression Scale; A-hea, Health Concerns Scale; A-aln, Alienation Scale; A-biz, Bizarre Mentation Scale; A-ang, Anger Scale; A-cyn, Cynism Scale; A-con, Conduct Problems Scale; A-lse, Low Self-Esteem Scale; A-las, Law Aspirations Scale; A-sod, Social Discomfort Scale; A-fam, Family Problems Scale; A-sch, School Problems Scale; A-trt, Adolescent-Negative Treatment Indicators Scale; ICC, intraclass correlation.

The statistical analysis was carried out using the statistical software STATA V.11.

Results

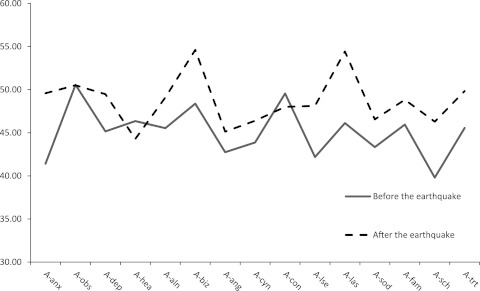

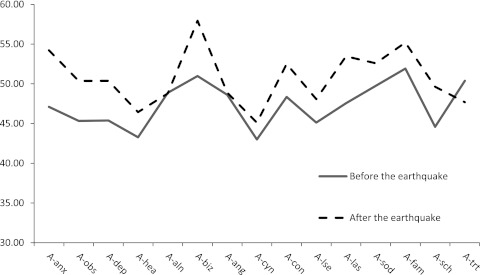

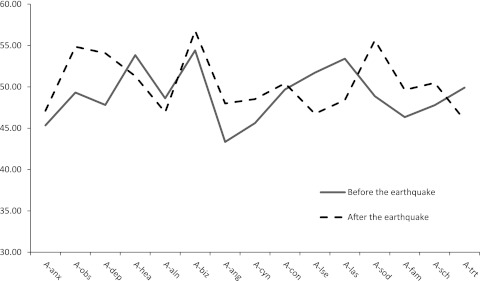

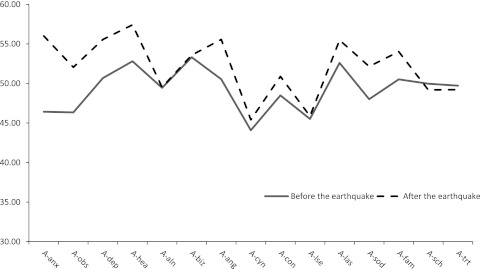

The analysis estimated the impact of the earthquake, gender, sports practice and the two- and three-way interactions on each of the 15 content scales of the MMPI-A questionnaire. Table 2 reports the results of the linear mixed models, which clarify the importance of the earthquake factor on every content scale except for A-trt (Adolescent-Negative Treatment Indication), which is not significant at p=0.387. The profile variations for the factors of gender and sport are shown in figures 1–4 to be parallel to the indications of the estimated effects produced by the model. The sport factor affects the following content scales with statistically significant coefficients: A-anx (−3.42±1.58, p=0.03), A-obs (4.12±1.60, p=0.01), A-ang (−6.52±1.45, p=0.00), A-sod (−2.82±1.47, p=0.05), A-fam (−5.08±1.49, p=0.001) and A-sch (−3.50±1.73, p=0.04). Despite the expected differences among those who practice sports, different response patterns were observed for different content scales and were characterised by different interactions. For A-anx, there were different responses to the quake according to both gender (2.13±0.76, p=0.005) and sports practice (−3.43±0.78, p=0.00). The last observation indicated that boys who practiced sports after the earthquake showed an average reduction of 3.43 points in their A-anx scores compared with the boys who did not usually practice sports. The same protective pattern appears for girls who practiced sports versus those who did not practice sports.

Figure 1.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—Adolescents content scales average profiles before and after the earthquake (boys practicing sport). A-anx, Anxiety Scale; A-obs, Obsessiveness Scale; A-dep, Depression Scale; A-hea, Health Concerns Scale; A-aln, Alienation Scale; A-biz, Bizarre Mentation Scale; A-ang, Anger Scale; A-cyn, Cynism Scale; A-con, Conduct Problems Scale; A-lse, Low Self-Esteem Scale; A-las, Law Aspirations Scale; A-sod, Social Discomfort Scale; A-fam, Family Problems Scale; A-sch, School Problems Scale; A-trt, Adolescent-Negative Treatment Indicators Scale.

Figure 2.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—Adolescents content scales average profiles before and after the earthquake (boys not practicing sport). A-anx, Anxiety Scale; A-obs, Obsessiveness Scale; A-dep, Depression Scale; A-hea, Health Concerns Scale; A-aln, Alienation Scale; A-biz, Bizarre Mentation Scale; A-ang, Anger Scale; A-cyn, Cynism Scale; A-con, Conduct Problems Scale; A-lse, Low Self-Esteem Scale; A-las, Law Aspirations Scale; A-sod, Social Discomfort Scale; A-fam, Family Problems Scale; A-sch, School Problems Scale; A-trt, Adolescent-Negative Treatment Indicators Scale.

Figure 3.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—Adolescents content scales average profiles before and after the earthquake (girls practicing sport). A-anx, Anxiety Scale; A-obs, Obsessiveness Scale; A-dep, Depression Scale; A-hea, Health Concerns Scale; A-aln, Alienation Scale; A-biz, Bizarre Mentation Scale; A-ang, Anger Scale; A-cyn, Cynism Scale; A-con, Conduct Problems Scale; A-lse, Low Self-Esteem Scale; A-las, Law Aspirations Scale; A-sod, Social Discomfort Scale; A-fam, Family Problems Scale; A-sch, School Problems Scale; A-trt, Adolescent-Negative Treatment Indicators Scale.

Figure 4.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—Adolescents content scales average profiles before and after the earthquake (girls not practicing sport). A-anx, Anxiety Scale; A-obs, Obsessiveness Scale; A-dep, Depression Scale; A-hea, Health Concerns Scale; A-aln, Alienation Scale; A-biz, Bizarre Mentation Scale; A-ang, Anger Scale; A-cyn, Cynism Scale; A-con, Conduct Problems Scale; A-lse, Low Self-Esteem Scale; A-las, Law Aspirations Scale; A-sod, Social Discomfort Scale; A-fam, Family Problems Scale; A-sch, School Problems Scale; A-trt, Adolescent-Negative Treatment Indicators Scale.

Girls and boys perform differently with respect to A-dep (−4.25±1.60, p=0.008), that is, depression, as characterised by A-dep, changed in relation to the earthquake and sport factors.

As measured by the MMPI-A, the situation for the adolescents living in L'Aquila is worse 2 years after the earthquake compared with before the earthquake. The factors negatively affected post-earthquake include personality discomfort; low self-esteem; anger; family issues; problems at school, with different grades for boys and girls,21 and decreased sports participation rates.

Social discomfort and family problems, among other scales examined, behaved differently, according to the different interactions of boys and girls with the earthquake impact factor. These factors are sources of concern for decision makers and administrators because they are usually associated with communication problems between the most important actors in the education of adolescents, namely, the family and the school. The problems observed above are expected, given the lack of opportunity to encounter other adolescents as well as lack of important leisure experiences due to the destruction of the urban environment.22

Unexpectedly, anger increased over time (see table 2) but was not moderated by the earthquake–sport interaction (p=0.20). The variable A-cyn, which describes misanthropic beliefs according to MMPI-A, does not show a statistically significant interaction between the earthquake occurrence and sport activity (p=0.17), that is, there is no group-specific trend of adolescents who practice sports compared with the adolescents who do not practice sports. A summary of the sport factor indicates that there is no statistically significant interaction between the earthquake's impact and the sport variable for A-dep, A-aln, A-ang, A-cyn, A-lse or A-fam (see table 2).

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was the public health concern of adolescents' well-being post-earthquake rather than an examination of psychopathologies in adolescents. The study did not include ‘pathological subjects’; thus, the scores of the MMPI-A content scales were not high in magnitude but still presented significant variations in the subjects' personality profiles.23

Despite the unusual context of its use, the current application of the MMPI-A appears to be promising as a method of population analysis after disasters because of the rich psychological profile descriptions obtained and the identification of critical psychological dimensions among the population.24 On the other hand, the use of MMPI-A in studies after disaster can be criticised, as the use of a 478-item questionnaire appears time consuming and inadequate to fit with survivors' need to regain control over their own lives. In these circumstances, shorter instruments should be preferable.

The current analysis suggests that amateur sport practice may have a role in addressing psychological and personality problems that are associated with or exacerbated by the disruption of everyday life due to natural catastrophic events. When based on expectations about one's own time and leisure, choosing to practice sports appears to reveal deep psychological patterns that affect social interaction and personal self-estimation. The comparisons in this study provide evidence that adolescents exposed to sports show a better response to extreme situations such as earthquakes when compared with adolescents not exposed to sports.

The evidence presented above indicates a possible method for coping with the social discomfort and other psychological issues experienced by adolescents who suffer through natural catastrophes.25 The inclusion of sports practice could be a qualifying feature of the catastrophe managing policy for adolescents.

Suggestions for further study include estimation of the ‘elasticity’ of the personality profile changes, that is, identification of the amount of time required to return to the pre-quake mental health condition and the eventual memory effects of the earthquake regarding the items involved in the analysis.26

The limitations of the present study include the restriction of analysis to the factors of gender and sports practice that were chosen at the study onset. Nevertheless, the present study promoted the evaluation of important aspects of adolescent mental health that are not currently being addressed by the healthcare decision makers.

A main drawback of this study is the lack of adjustment for the socioeconomic status of the subjects.27 The cross-sectional survey carried out before the earthquake used the density of inhabitants per room (DIR), or the ratio of people dwelling in a house and the number of rooms occupied including kitchen, living room and bathrooms, as a proxy covariate of socioeconomic status. The inclusion of DIR allowed a basic knowledge of the social condition of all the adolescents interviewed. After the earthquake, DIR was no longer representative of socioeconomic status for most subjects because these subjects were no longer able to precisely indicate their housing status. This consideration forced the authors to discard DIR as a relevant variable. However, it is plausible that this lack of information parallels the behaviour of the factor earthquake. Statistically speaking, socioeconomic status is expected to have some collinearity with the quake factor,28 but this cannot be accounted for exactly in the present study, and it is not possible to suggest a design that accounts for these factors because of the randomness of earthquakes' occurrences.

In conclusion, the results of the current study show an overall positive impact of sports practice on adolescents' psychological response to natural disasters.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Valenti M, Vinciguerra MG, Masedu F, et al. A before and after study on personality assessment in adolescents exposed to the 2009 earthquake in L'Aquila, Italy: influence of sports practice. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000824. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000824

Contributors: MV was the principal investigator, conceived and designed the study protocol and provided the final interpretation of data. MGV participated in designing the study, questionnaire administration and interpretation of data. FM performed the statistical data analysis. ST contributed to the study design and interpretation of results. VS participated in designing the study protocol and interpretation of data. All authors gave substantial contribution to manuscript writing and editing.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board, Department of Mental Health, Health Agency of L'Aquila, Italy.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data from the study are available.

References

- 1.Asarnow J, Glynn S, Pynoos RS, et al. When the earth stops shaking: earthquake sequelae among children diagnosed for pre-earthquake psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:1016–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr VJ, Lewin TJ, Welster RA, et al. A synthesis of the findings from the Quake Impact Study: a two-year investigation of the psychosocial sequelae of the 1989 Newcastle earthquake. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1997;32:123–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casacchia M, Roncone R, Pollice R. The narrative epidemiology of L'Aquila 2009 earthquake. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2012;21:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai K, Chou P, Chou FH, et al. Three-year follow up study of the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and quality of life among earthquake survivors in Yu-Chi, Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res 2007;41:90–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shannon MP, Lonigan CJ, Finch AJ, Jr, et al. Children exposed to disaster: I. Epidemiology of post-traumatic symptoms and symptom profiles. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994;33:80–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, Shi Z, Wang L, et al. One year later: mental health problems among survivors in hard-hit areas of the Wenchuan earthquake. Public Health 2011;125:293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dell'Osso L, Carmassi C, Massimetti G, et al. Full and partial PTSD among young adult survivors 10 months after the L'Aquila 2009 earthquake: gender differences. J Affect Disord 2011;131:79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armenian HK, Morikawa M, Melkonian AK, et al. Loss as a determinant of PTSD in a cohort of adult survivors of the 1988 earthquake in Armenia: implications for policy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;102:58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambrose PA. Challenges for mental health service providers: the perspective of managed care organizations. In: Butcher JN, ed. Personality Assessment in Managed Care: Using the MMPI-2 in Treatment Planning. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997:61–72 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandra A, Acosta JD. Disaster recovery also involves human recovery. JAMA 2010;304:1608–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawrence S, De Silva M, Henley R. Sports and games for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(1):CD007171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butcher JN, Williams CL, Graham JR, et al. Il MMPI per gli adolescenti. Firenze: Giunti OS, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Archer RP. MMPI-A: Assessing Adolescents Psychopathology. London: Lawrence Elbaum Associates Publishers, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butcher JN, Williams CL, Graham JR, et al. Manual for Administration, Scoring, and Interpretation of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory for Adolescents: MMPI-A. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Twisk JWR. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis for Epidemiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allard G, Faust D. Errors in scoring objective personality tests. Assessment 2000;7:119–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hand CG, Archer RP, Handel RW, et al. The classification accuracy of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-Adolescent: effects of modifying the normative sample. Assessment 2007;14:80–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hathaway SR, Monachesi ED. Adolescent Personality and Behavior: MMPI Patterns of Normal, Delinquent, Dropout, and Other Outcomes. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou FH, Wu HC, Chou P, et al. Epidemiologic psychiatric studies on post-disaster impact among Chi-Chi earthquake survivors in Yu-Chi, Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007;61:370–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzmaurice G, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004:188–9 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arbisi PA, Butcher JN. Relationship between personality and health symptoms: use of the MMPI-2 in medical assessments. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2004;4:571–95 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oyama M, Nakamura K, Suda Y, et al. Social network disruption as a major factor associated with psychological distress 3 years after the 2004 Niigata-Chuetsu earthquake in Japan. Environ Health Prev Med 2012;17:118–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piko BF, Keresztes N. Self-perceived health among early adolescents: role of psychosocial factors. Pediatr Int 2007;49:577–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health 2005;27:281–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Samsa GP, et al. Are health-related quality of life measures affected by mode of administration? J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:135–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nivolianitou Z, Synodinou B. Towards emergency management of natural disasters and critical accidents: the Greek experience. J Environ Manag 2011;92:2657–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss JW, Mouttapa M, Cen S, et al. Longitudinal effects of hostility, depression, and bullying on adolescent smoking initiation. J Adolesc Health 2011;48:591–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahern J, Galea S. Social context and depression after a disaster: the role of income inequality. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:766–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.