Abstract

Pregnane X receptor (PXR; NR1I2), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, has a major role in the induction of genes involved in drug transport and metabolism. Recent studies in mice have provided insight into a novel function for PXR in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The mechanisms of the protective effect of PXR activation on IBD is not fully established, but is due in part to the attenuation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling that results in lower expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Recent clinical trials with the antibiotic rifaximin, a PXR agonist in the gastrointestinal system, have revealed its potential therapeutic value in the treatment of intestinal inflammation in humans. Thus, PXR may be a novel target for IBD therapy.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. IBD has shown a steep rise in incidence and is now one of the five most prevalent gastrointestinal diseases in the USA1. IBD compromises Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). UC is an inflammatory disease that affects the lining of the colon, whereas CD can affect any part of the digestive tract, with inflammation that extends deeper into the layers of the intestinal wall. While the etiology of IBD is unclear, the prevailing view is that it is triggered by multiple factors, including environment, genetic variations, intestinal microbiota, and disturbances in the innate and adaptive immune response2. The most common symptoms of both UC and CD are recurring abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding and malnutrition. IBD patients have a much higher incidence of colorectal cancer compared to the general population3. Moreover, IBD can cause other health problems that occur outside the digestive system, notably increased inflammation elsewhere in the body, including the joints, eyes, skin, and liver4.

Under normal conditions, the intestinal mucosa is in a state of “controlled” inflammation regulated by a delicate balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. The pathogenesis of IBD involves defects in the intestinal epithelial barrier and mucosal immune system, resulting in active inflammation and tissue destruction. There is a reciprocal crosstalk leading to IBD, with a loss in intestinal epithelial barrier integrity that results in inflammation due to increased diffusion of luminal microbiota. The activation of the mucosal inflammatory response leads to a further compromised intestinal barrier5. This cyclical feed-forward mechanism results in chronic inflammation and tissue injury. Although the primary cause is not completely clear, several risk loci have been identified by genome-wide association studies6–8. These loci map to genes that are involved in key cellular processes such as innate immune recognition9, autophagy10, cell-cell contact11 and aspects of cytokine signaling12. In addition, certain nuclear receptors13–15 are implicated in the etiology of IBD through their roles in controlling the immune responses and hormone-regulated homeostasis.

Nuclear receptors regulate the inflammatory response in several disease states, such as atherosclerosis, obesity and type II diabetes, IBD, Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, and cancer16. Growing evidence in humans and animal models revealed that orphan and adopted orphan nuclear receptors, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α (NR1C1)17, PPARβ (NR1C2)18, PPARγ (NR1C3)19, glucocorticoid receptor (GR; NR3C1)20, liver X receptor (LXR; NR1H2) 21, farnesoid X receptor (FXR; NR1H4)15, vitamin D receptor (VDR; NR1I1)22, RAR-related orphan receptor γ (RORγ; NR1F3)23, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 α (HNF4α; NR2A21)24, estrogen receptor α (ERα; NR3A1)25, and pregnane X receptor (PXR; NR1I2)26 regulate the inflammatory response in IBD. Among these, PXR is the best characterized for its modulation of drug transport and metabolism through the regulation of target genes responsible for the transport and conversion of chemicals into metabolites that are more easily eliminated from the body27. It is activated by xenobiotics, including many drugs; thus, it contributes to drug metabolism and clearance and is involved in drug-drug interactions. PXR is also emerging as an endobiotic receptor that regulates the inflammatory response28. In this review, we summarize the role of PXR as an effective modulator of IBD and discuss the potential therapeutic application of its ligands in the clinical treatment of IBD.

PXR

PXR is well-known for its pivotal function in the control of drug metabolism27. PXR has a flexible ligand binding pocket29 which can bind structurally diverse ligands, including prescription drugs, natural products, dietary supplements, environmental pollutants, endogenous hormones and bile acids27. Similar to other members of the nuclear receptor superfamily, PXR possesses a conserved N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) and C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD), and functions as a heterodimer with the 9-cis retinoic acid receptor, also known as retinoid X receptor α (RXRα; NR2B1), to control gene transcription30. Although the human and mouse PXR share nearly 80% amino acid identity across the LBD, 96% amino acid identity in the DBD, and display similar tissue expression patterns, the differences between the LBD sequences across species influences species-specific responses to ligand activation. For example, rifampicin has virtually no effect on the mouse PXR at typical pharmacological doses, but is a very potent agonist of the human PXR31. Conversely, pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile (PCN) only weakly activates the human PXR but is an efficacious agonist of the mouse PXR32. Human PXRs are expressed in small intestine, colon, liver, and gall bladder, with lower expression in stomach33. The distribution and function of human PXRs in the gastrointestinal system contribute to its emerging role as a modulator of inflammation in the intestinal mucosa barrier.

Role of PXR in the pathogenesis of IBD

PXR agonists in the treatment of IBD

A role for PXR in protection against IBD was revealed by studies using an experimentally-induced IBD model with a PXR agonist in wild-type (WT) and pxr−/− mice. Mice treated with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) developed symptoms of IBD typically seen in humans, including body weight loss, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, shortened colon length, and altered intestinal crypt structure34. Treatment of WT mice with the mouse PXR ligand pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile (PCN) alleviated IBD symptoms, whereas mice lacking PXR expression were not affected35. Activation of PXR also decreased intestinal permeability in WT and not in pxr−/− mice35. The intestinal epithelial assay is considered a direct reflection of epithelial barrier function36 and thus indicates a protective effect on intestinal permeability as a result of PXR activation. These studies also revealed that activation of PXR suppresses expression of the NF-κB target genes including IL-1β, IL-10, iNOS, and TNFα, suggesting that PXR dampens the inflammatory response, although other mechanisms for the PXR protection in IBD cannot be ruled out (see below).

Validation of PXR as a potential target for treatment of IBD in humans was demonstrated through study of rifaximin (Xifaxan), a semi-systemic rifamycin-derived antibiotic that exhibits low gastrointestinal absorption while retaining potent antibacterial activity in the gastrointestinal system. The FDA approved Rifaximin in 2004 for the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea, and in 2011 for hepatic encephalopathy therapy. The minimal absorption of rifaximin is likely due to its self-association tendency in contrast to oral absorption of other rifamycin derivatives (e.g. rifampicin) that enter the body via passive diffusion. Pharmacokinetic studies in animal models revealed that 80–90% of rifaximin is concentrated in the intestine; less than 0.2% of rifaximin is transported into the liver and kidney, and less than 0.01% is distributed in other tissues37. Clinical pharmacokinetics further showed that serum levels of rifaximin were below the limits of detection in healthy adults following oral administration of rifaximin. In addition, there was no evidence for the accumulation of rifaximin in the body following repeated administration37. These studies confirmed that while rifaximin is not suitable for treating systemic bacterial infections, it could have a distinct advantage on direct therapy of intestinal bacteria to protect intestinal barrier function.

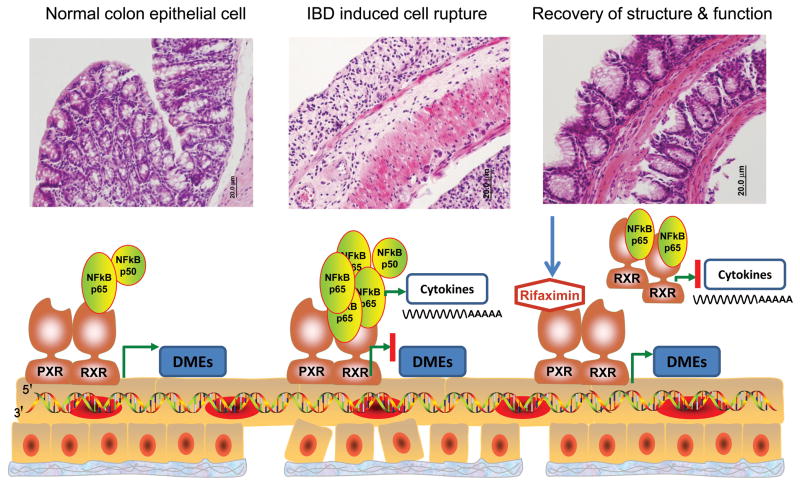

Rifaximin is a intestine-specific human PXR agonist38; treatment of PXR-humanized mice (mice in which the complete human PXR gene was introduced to the pxr−/− mice) with rifaximin resulted in significant induction of PXR target genes in the intestine, but had no significant effect on the induction of hepatic PXR target genes38. In contrast, rifampicin, another related antibiotic with oral bioavailability, was able to activate gene expression in both the intestine and liver. Cell-based reporter gene assays demonstrated that rifaximin activates human PXR but not mouse PXR or other nuclear receptors including constitutive androstane receptor (CAR; NR1I3), PPARα, PPARγ, and FXR. Rifaximin also reduced NF-κB signaling in a PXR-dependent manner in primary human colon epithelial cells as well as in human colon biopsies39. The preventive and therapeutic role of rifaximin in experimental models of IBD was demonstrated in the PXR-humanized mouse where rifaximin not only prevented IBD before an inflammatory insult, as revealed by use of the DSS and 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) mouse models of IBD, but also decreased the symptoms after the onset of colitis40. Conversely, rifampicin had no impact on experimentally-induced IBD. Among the possible reasons that rifampicin cannot protect against IBD is that rifampicin markedly reduces the hepatic expression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD-1) due to its high systemic bioavailability, in contrast to the minimal absorption of rifaximin in the circulation40. Reduced SCD-1 results in lower levels of unsaturated lysophosphatidylcholine in plasma, which is among the most important anti-inflammatory unsaturated fatty acids41. Clinically, rifaximin appears to have more efficacy in the therapy of CD than do traditional medications used to treat IBD such as metronidazole and/or ciprofloxacin42–43, due in part to its well-tolerated and efficient effects in adult CD patients44 as well as for pediatric IBD45. Several clinical trials demonstrated that rifaximin decreased intestinal permeability in adult/pediatric patients with gastrointestinal diseases, such as small intestine bacterial overgrowth46 or tropical enteropathy47. These data provide evidence for the use of rifaximin in intestinal disorders and firmly establish a role for PXR in IBD therapy40 (Figure 1).

Fig 1. Rifaximin repression of IBD via human PXR regulation.

Chemically-induced IBD destroys the structure and function of normal epithelial cells and expression of DMEs (A), due in part to activation of NF-κB and increased proinflammatory cytokines. (B) following an imbalance of the epithelial barrier and mucosal immune system and increase of intestinal permeability. However, upon rifaximin-induced PXR activation in epithelial cells, the NF-κB signaling cascade is repressed and cytokine production is inhibited, associated with suppression of intestinal permeability through PXR activation. This restores the balance between the epithelial barrier and mucosal immune system, resulting in the reconstruction of cell structure and function (C). DMEs: drug metabolism enzymes.

Other evidence for the involvement of PXR in protection against IBD was obtained with curcumin. Curcumin is a spice and dietary supplement that demonstrates preventive effects on IBD in a mouse model48. Among the possible mechanisms proposed for effect of curcumin on IBD is that curcumin activates human PXR, as revealed by increased CYP3A4 promoter luciferase activity in HepG2 cells49. Curcumin significantly reduces the histological signs of colonic inflammation in mdr1a−/− mice50; mdr1a is a gastrointestinal transporter that is induced by PXR50, and thus the protection by curcumin on mdr1a−/− mice is assumed through PXR activation. Solomonsterol A, a newly-reported PXR agonist extracted from the sponge Theonella Swinhoei, also protects against the development of clinical signs and symptoms of colitis through reduction of TNFα in PXR-humanized mice51. These studies suggest that PXR agonists hold promise in the treatment of inflammation-driven immune dysfunction in clinical settings.

PXR role in IBD pharmacotherapy

IBD treatment regimens depend on the level of severity of the disease. Drug treatments include combined administration or administration alone of aminosalicylates, immunosuppressive drugs, antibiotics, and corticosteroids52. Many of the drugs used in the conventional therapy of IBD are metabolized and transported by CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein (P-gp), respectively52. Thus, PXR agonists (e.g. rifaximin, rifampicin31, St John’s wort27 etc.) and PXR antagonists (e.g. ketoconazole, itraconazole, fluvoxamine or grapefruit juice27) would affect the pharmacokinetics of CYP3A4 drug substrates due to its activation or lack of activation27. For example, corticosteroids are the most widely used drugs in IBD treatment due to their immunosuppressive activity and long biological half-life. However, the area under the curve (AUC) of budesonide, an efficient corticosteroid used in IBD treatment, increased by 6.5-fold when co-administrated with ketoconazole, compared to a 3.8-fold increase in the AUC when these two drugs were administered 12 hours apart53. Thus, dosage reductions of the corticosteroids are applied when inhibitors of CYP3A4 metabolism or induction are used concomitantly with corticosteroids.

Altered expression of drug transporters can also impact IBD therapy. For example, mesalazine, an aminosalicylate drug used to treat IBD, is metabolized into N-acetyl-mesalazine that is transported by P-gp. High expression of P-gp was associated with failed treatment of mesalazine in IBD patients54. In addition, cyclosporine, a common immunosuppressive drug sometimes used in IBD, is extensively metabolized by CYP3A4 and transported by P-gp. PXR agonists can increase hepatic clearance of cyclosporine and reduce its bioavailability55.

Clinical reports revealed that rifaximin alone or in combination with other antibiotics appeared to have a significant effect at inducing remission in active IBD56. Because rifaximin is a gut-specific agonist of human PXR38, one plausible mechanism is that rifaximin induces CYP3A4 leading to clinically significant reductions in the bioavailability of established drugs that are CYP3A4 substrates. Coupled with increased clearance, this induction of CYP3A4 may reduce the possibility of drug-induced hepatic or renal toxicity. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether modulation of the pharmacokinetic properties by PXR increases the desired effects and simultaneously reduces the typical systemic adverse effects of IBD drugs, especially when used in combination with other agents.

Mechanisms for the influence of PXR on IBD

Polymorphisms of PXR in IBD

Evidence from several studies suggests that xenobiotic metabolism may play a role in IBD and that low levels of PXR may be associated with disease expression. An Irish cohort including 422 patients with IBD and 350 ethnically matched controls was examined for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and several polymorphisms were identified in the PXR gene that were over-represented in IBD patients as compared with controls57. Moreover, an independent study identified other SNPs in the PXR gene that were associated with CD but not with UC in Caucasian patients58. Evaluation of a Spanish cohort of 365 UC and 331 CD patients, and 550 ethnically matched controls showed significant differences in the overall haplotype of IBD between UC and CD patients59 in PXR SNPs. Although these studies have shown a genetic association of PXR with IBD, it is important to note that others did not find an association between the PXR polymorphism and IBD through the analysis of 187 pediatric IBD patients and 185 controls60. Although the results are mixed, an association of genetic variation in the PXR gene with susceptibility to IBD cannot be rulled out. However, it needs to be emphasized that functional analysis of the roles of any SNPs in and around the PXR gene on PXR expression and activity have not been done to establish a mechanistic basis for the association with IBD.

PXR modulation of NF-κB

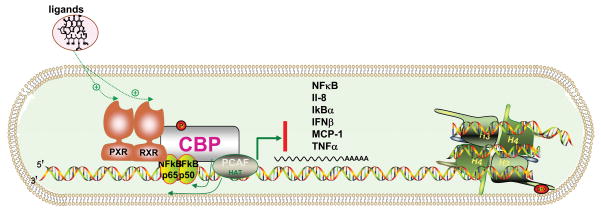

Reciprocal crosstalk between PXR and NF-κB may be the mechanism for the anti-inflammatory properties of PXR28. The NF-κB family comprises five members, namely p65 or Rel A, Rel B, Rel C, p50, and p52, and is a key regulator of inflammation and the innate and adaptive immune responses61. NF-κB normally remains in the cytoplasm bound to the protein inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB). Activating signals, such as proinflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and viral products lead to phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, thus allowing NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus and directly regulate the expression of its target genes62. NF-κB signaling is significantly inhibited following PXR activation63. Consistent with this data, pxr−/− mice showed an increase in NF-κB target gene expression and demonstrated chronic inflammation in the small intestine28. In addition, PXR silencing increased expression of TNF-α, IL-8, and other proinflammatory cytokines, and decreased transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and interferon-gamma-inducible 10 kD protein (IP-10) in primary fetal human colon epithelial cells39 as well as human hepato64-or colon carcinoma cell lines39–40. Exposure to rifaximin caused a robust attenuation of inflammatory mediators and increased the generation of TGF-β39. PXR silencing by siRNA completely abrogated these anti-inflammatory effects of rifaximin, due to less binding of NF-κB with PXR. Additional clues emerged when it was reported that NF-κB can directly interact with RXRα63, an essential dimerization partner for various nuclear receptors such as PXR. PXR binds to response element of target genes as a heterodimer with RXRα63. Because NF-κB interferes with RXRα binding, activated NF-κB could reduce PXR transactivation activity via interference with RXRα. This mechanism of suppression by NF-κB may be extended to other nuclear receptor-regulated systems in which RXRα is a dimerization partner (Figure 2).

Fig 2. The cross-inhibition between PXR and NF-κB.

NF-κB contains two major components, p65 and p50. PXR/RXR heterodimer auto-bind with CBP, PCAF and HAT initially to regulate transcription. NF-κB can directly interact with the RXR. Thus, one possibility to explain the link between NF-κB and PXR is through the binding of p65 and RXR. This binding is triggered upon ligand binding of PXR response element. The binding between p65 and RXR may also interfere with the formation of the p65-p50 complex and subsequent DNA binding. CBP: CREB-binding protein, PCAF: P300/CBP-associated factor, HAT: histone acetyltransferase, H3/H4: histones. Cytokines are IL-8: interleukin 8, IκBα: IκBα-NFκB complex, IFNβ: interferon-beta, MCP-1: monocyte chemotactic protein-1, TNFα: tumor necrosis factors alpha.

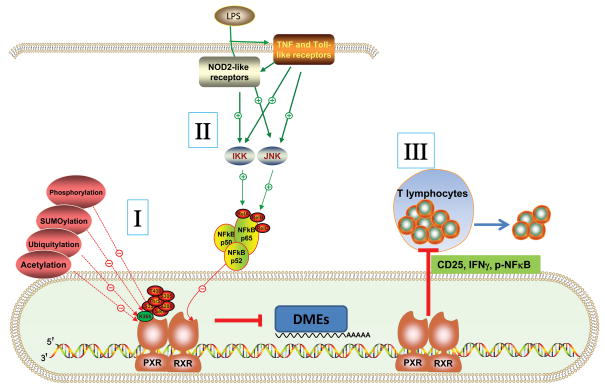

Likewise, the crosstalk between pattern recognition receptors (PRR) and PXR might also be through NF-κB binding to RXRα. The innate immune system, initiated by PRR provides the first line of host defense against invading pathogens65. Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a family of PRR that sense a wide range of microorganisms, are expressed in the intestine and are critical for intestinal homeostasis66–67. Cytoplasmic PRR, such as NOD2-like receptor (NLR), detect pathogens that have invaded the cytosol and are involved in the pathogenesis of CD68. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines activate a variety of cell-signaling kinases including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and NF-κB69. Activation of JNK by LPS results in modification of RXRα, leading to suppression of PXR/RXRα hepatic target genes69. Lipoteichoic acid, a toxic bile acid, can induce TLR2 and the pro-inflammatory cytokines, JNK and NF-κB. Subsequently, PXR and CAR and its target genes are rapidly and significantly repressed70 (Figure 3). In all, the relationship between NF-κB and PXR is likely a mechanism that mediates the protective effects of PXR in inflammatory diseases, thus establishing a signaling network involving PXR with NF-κB as a central hub.

Fig 3. Multiple signaling cascades to repress IBD via PXR modulation.

Crosstalk between PXR and NF-κB, through direct action of PXR by ubiquitylation, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, and acetylation could impact inflammation (I), as well as germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRR, including TLR/NOD2) activation of JNK or IKK by LPS resulting in the modification of RXRα, leading to suppression of PXR/RXRα-dependent hepatic genes (DMEs, drug metabolism enzymes) (II). In addition, PXR inhibits T lymphocyte proliferation by decreasing expression of cytokines of CD25 and IFNγ and decreasing phosphorylation of NF-κB in mouse and human T lymphocytes (III). JNK: c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase, IKK: IκB kinase, CD25:alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor, IFNγ: Interferon-gamma.

Post-translational modulation of PXR

In addition to the possible modulation of NF-κB through RXRα-PXR, post-translational modulation of PXR by ubiquitylation71, phosphorylation72, SUMOylation73, and acetylation74 could impact inflammation (Figure 3). Serological biomarkers in IBD indicate that ubiquitination factor E4A (UBE4A), a U-box-type ubiquitin-protein ligase, is upregulated in IBD. Higher levels of anti-UBE4A IgG were associated with severe syndromes71. Although UBE4A expression is low in the cytoplasm of enterocytes and goblet cells, immunohistological analysis showed that UBE4A expression was highly elevated only in entero-endocrine cells of ileal mucosa from CD patients, and not in normal subjects75. Additionally, PXR and CYP3A4 ubiquitination increases during inflammation in the small intestine76. Thus, repression of PXR through up-regulated ubiquitylation in IBD might raise the activity of NF-κB and thus induce the inflammatory response.

In IBD, cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) signaling is activated77. PXR can serve as a substrate for catalytically-active PKA in vitro, as revealed by the up-regulation of PXR in mouse hepatocytes by the PKA activator 8-bromo-cyclic AMP72. PXR activity can potentially be regulated by phosphorylation at specific amino acid residues within several predicted consensus kinase recognition sequences to differentially affect PXR biological activity. The amino acid residues Thr57, Ser208, Ser305, Ser350, and Thr408 are thought to be critical phosphorylation sites regulating the biological activity of the PXR 68. Mutations at positions Thr57 and Thr408 abolish ligand-inducible PXR activity, whereas mutations at Ser8, Ser305, Ser350, and Thr408 of the extreme N-terminus and in the PXR ligand-binding domain, decrease the ability of PXR to form heterodimers with RXR78. The subcellular localization of the PXR protein is also profoundly affected by mutations at Thr408. Thr57 abolishes transactivation activity and alters nuclear localization pattern of human PXR79. These studies confirm that the activity of PXR is modulated by changes in its overall phosphorylation status80. Determining whether phosphorylation of PXR at specific sites regulates inflammation in IBD remains an open and important question for future studies.

A recent report revealed that SUMOylated PXR directly represses NF-κB in liver73. SUMOylation is a post-translational modification involved in various cellular processes, such as nuclear-cytoplasmic transport, transcriptional regulation, apoptosis, protein stability, response to stress, and progression through the cell cycle. This analysis revealed that the human PXR protein can serve as an effective substrate for human SUMO1, SUMO2, or SUMO3 in the SUMO-conjugation pathway and that the SUMOylation sites serve as a functional link between ligand-activated PXR and its ability to transrepress NF-κB activity73. In addition, the effect of PXR acetylation and metabolic status on ligand-mediated PXR gene activation pathways is observed in patients with morbid obesity, hepatic steatosis, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, although the potential role is not determined74.

Inhibition of T lymphocyte proliferation by PXR

The intestine is the largest lymphoid organ in the body because of the huge antigen load to which it is exposed on a daily basis81. Many studies have shown that activated T cells mediate chronic intestinal inflammation82. PXR is expressed in human CD4, CD8, CD19, and CD14 cells83. 8-Methoxypsoralen (8-MOP), a prototype photochemotherapeutic agent used to repress cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, activates PXR84. Cyclosporine A, a PXR agonist which is intravenously administrated to treat steroid-refractory severe UC, inhibits T-cell function85. Upon immune stimulation, activation of PXR inhibits T lymphocyte proliferation and anergizes T lymphocytes by decreasing the expression of CD25 and IFN-gamma and decreasing phosphorylated NF-κB and MEK1/2 in mouse and human T lymphocytes86. Conversely, pxr−/− mice exhibit an exaggerated T lymphocyte proliferation and increased CD25 expression86. Furthermore, PXR-deficient lymphocytes produce more IFNγ and less anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-1086. Thus, the immune-regulatory role of PXR in T lymphocytes may contribute to the suppression of T lymphocyte proliferation in IBD (Figure 3).

Concluding remarks

In summary, PXR exerts a positive therapeutic role in IBD through mechanisms involving feedback with NF-κB, TLR, NOD2, and modulation of T lymphocytes. The coordinate regulation between PXR and other nuclear receptors may also be important due to similar mechanisms involving modulation of the NF-κB signaling cascade. Rifaximin and other novel candidate drugs as possible novel agents for the treatment of IBS and IBD based on PXR-targeted therapy need further attention. Although rifaximin has shown promise for IBD therapy in clinical trials, concerns have been raised about the development of antibiotic resistance because patients will be administered the drug for long periods of time87. Thus, if the effect of rifaximin on IBD is due to its activation of PXR and not through its bacterial killing properties, other gut-specific PXR ligands that do not have antibiotic activities could be developed. As patients with IBD are six times more likely to develop colorectal cancer, PXR and related drug treatment for IBD might be a target for chemoprevention of colon carcinogenesis. Although a few reports on the role of PXR in colon cancer have been published, the results are still controversial88–89. More studies on the role of PXR in colitis-associated colon cancer are warranted. The importance of PXR in IBD is becoming increasingly clear. A complete understanding of the role and regulation of PXR in IBD is progressing quickly and may be useful for the development of novel strategies to better predict, prevent and treat of IBD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute Intramural Research Program and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (CA148828) to Y.M.S. We thank Caroline Johnson for review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors received rifaximin from Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. There are no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Long MD, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of overweight and obesity in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2162–2168. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeire S, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and colitis: new concepts from the bench and the clinic. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:32–37. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283412e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jawad N, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2011;185:99–115. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-03503-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molodecky NA, et al. Increasing Incidence and Prevalence of the Inflammatory Bowel Diseases With Time, Based on Systematic Review. Gastroenterology. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Bousvaros A. Innate and adaptive immune connections in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:572–577. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833f126d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franke A, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khor B, et al. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson CA, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nat Genet. 2011;43:246–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabbah A, et al. Activation of innate immune antiviral responses by Nod2. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/ni.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rioux JD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:596–604. doi: 10.1038/ng2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danoy P, et al. Association of variants at 1q32 and STAT3 with ankylosing spondylitis suggests genetic overlap with Crohn's disease. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franke A, et al. Sequence variants in IL10, ARPC2 and multiple other loci contribute to ulcerative colitis susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1319–1323. doi: 10.1038/ng.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1330–1334. doi: 10.1038/ng.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darsigny M, et al. Loss of hepatocyte-nuclear-factor-4alpha affects colonic ion transport and causes chronic inflammation resembling inflammatory bowel disease in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nijmeijer RM, et al. Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) activation and FXR genetic variation in inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schupp M, Lazar MA. Endogenous ligands for nuclear receptors: digging deeper. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40409–40415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.182451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azuma YT, et al. PPARalpha contributes to colonic protection in mice with DSS-induced colitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:1261–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollingshead HE, et al. PPARbeta/delta protects against experimental colitis through a ligand-independent mechanism. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2912–2919. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubuquoy L, et al. PPARgamma as a new therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2006;55:1341–1349. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.093484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sidoroff M, Kolho KL. Glucocorticoid sensitivity in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Med. 2011 doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.590521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heimerl S, et al. Alterations in intestinal fatty acid metabolism in inflammatory bowel disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cross HS, et al. Colonic vitamin D metabolism: implications for the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;347:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mudter J, et al. IRF4 regulates IL-17A promoter activity and controls RORgammat-dependent Th17 colitis in vivo. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1343–1358. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn SH, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha in the intestinal epithelial cells protects against inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:908–920. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Looijer-van Langen M, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta signaling modulates epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G621–626. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00274.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng J, et al. Pregnane X receptor- and CYP3A4-humanized mouse models and their applications. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:461–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao J, Xie W. Pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor at the crossroads of drug metabolism and energy metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:2091–2095. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.035568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou C, et al. Mutual repression between steroid and xenobiotic receptor and NF-kappaB signaling pathways links xenobiotic metabolism and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2280–2289. doi: 10.1172/JCI26283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekins S, et al. Challenges predicting ligand-receptor interactions of promiscuous proteins: the nuclear receptor PXR. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ngan CH, et al. The structural basis of pregnane X receptor binding promiscuity. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11572–11581. doi: 10.1021/bi901578n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng J, et al. Rifampicin-activated human pregnane X receptor and CYP3A4 induction enhance acetaminophen-induced toxicity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1611–1621. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostberg T, et al. Identification of residues in the PXR ligand binding domain critical for species specific and constitutive activation. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:4896–4904. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang B, et al. PXR: a xenobiotic receptor of diverse function implicated in pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1695–1709. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.11.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalian M, et al. MR enterography findings of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W810–816. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah YM, et al. Pregnane X receptor activation ameliorates DSS-induced inflammatory bowel disease via inhibition of NF-kappaB target gene expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1114–1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00528.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeMeo MT, et al. Intestinal permeation and gastrointestinal disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:385–396. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ojetti V, et al. Rifaximin pharmacology and clinical implications. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:675–682. doi: 10.1517/17425250902973695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma X, et al. Rifaximin is a gut-specific human pregnane X receptor activator. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:391–398. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mencarelli A, et al. Inhibition of NF-kappaB by a PXR-dependent pathway mediates counter-regulatory activities of rifaximin on innate immunity in intestinal epithelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;668:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng J, et al. Therapeutic role of rifaximin in inflammatory bowel disease: clinical implication of human pregnane X receptor activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:32–41. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.170225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen C, et al. Metabolomics reveals that hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 downregulation exacerbates inflammation and acute colitis. Cell Metab. 2008;7:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, et al. Rifaximin versus other antibiotics in the primary treatment and retreatment of bacterial overgrowth in IBS. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:169–174. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9839-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lauritano EC, et al. Antibiotic therapy in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: rifaximin versus metronidazole. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2009;13:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shafran I, Burgunder P. Adjunctive antibiotic therapy with rifaximin may help reduce Crohn's disease activity. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1079–1084. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muniyappa P, et al. Use and Safety of Rifaximin in Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181a0d269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoffman JT, et al. Probable interaction between warfarin and rifaximin in a patient treated for small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e25. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trehan I, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin, a nonabsorbable antibiotic, in the treatment of tropical enteropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2326–2333. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanai H, Sugimoto K. Curcumin has bright prospects for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:2087–2094. doi: 10.2174/138161209788489177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kluth D, et al. Modulation of pregnane X receptor- and electrophile responsive element-mediated gene expression by dietary polyphenolic compounds. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nones K, et al. The effects of dietary curcumin and rutin on colonic inflammation and gene expression in multidrug resistance gene-deficient (mdr1a-/-) mice, a model of inflammatory bowel diseases. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:169–181. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508009847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sepe V, et al. Total synthesis and pharmacological characterization of solomonsterol A, a potent marine pregnane-X-receptor agonist endowed with anti-inflammatory activity. J Med Chem. 2011;54:4590–4599. doi: 10.1021/jm200241s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor KM, Irving PM. Optimization of conventional therapy in patients with IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:646–656. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seidegard J. Reduction of the inhibitory effect of ketoconazole on budesonide pharmacokinetics by separation of their time of administration. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:13–17. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.106895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farrell RJ, et al. High multidrug resistance (P-glycoprotein 170) expression in inflammatory bowel disease patients who fail medical therapy. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:279–288. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huwyler J, et al. Induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-glycoprotein by the isoxazolyl-penicillin antibiotic flucloxacillin. Curr Drug Metab. 2006;7:119–126. doi: 10.2174/138920006775541534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khan KJ, et al. Antibiotic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:661–673. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dring MM, et al. The pregnane X receptor locus is associated with susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:341–348. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.008. quiz 592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glas J, et al. Pregnane X receptor (PXR/NR1I2) gene haplotypes modulate susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1917–1924. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ho GT, et al. ABCB1/MDR1 gene determines susceptibility and phenotype in ulcerative colitis: discrimination of critical variants using a gene-wide haplotype tagging approach. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:797–805. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martinez A, et al. Role of the PXR gene locus in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1484–1487. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jacobs MD, Harrison SC. Structure of an IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Senftleben U, et al. Activation by IKKalpha of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Science. 2001;293:1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1062677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gu X, et al. Role of NF-kappaB in regulation of PXR-mediated gene expression: a mechanism for the suppression of cytochrome P-450 3A4 by proinflammatory agents. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17882–17889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Axon A, et al. A mechanism for the anti-fibrogenic effects of the pregnane X receptor (PXR) in the liver: inhibition of NF-kappaB? Toxicology. 2008;246:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Henckaerts L, et al. Mutations in pattern recognition receptor genes modulate seroreactivity to microbial antigens in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2007;56:1536–1542. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.125468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wells JM, et al. Epithelial crosstalk at the microbiota-mucosal interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4607–4614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000092107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uematsu S, Fujimoto K. The innate immune system in the intestine. Microbiol Immunol. 2010;54:645–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2010.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Werts C, et al. Nod-like receptors in intestinal homeostasis, inflammation, and cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:471–482. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0411183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ghose R, et al. Differential role of Toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein in Toll-like receptor 2-mediated regulation of gene expression of hepatic cytokines and drug-metabolizing enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:874–881. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.037382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghose R, et al. Regulation of gene expression of hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters by the Toll-like receptor 2 ligand, lipoteichoic acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;481:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li X, et al. New serological biomarkers of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5115–5124. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rodriguez-Lagunas MJ, et al. PGE2 promotes Ca2+-mediated epithelial barrier disruption through EP1 and EP4 receptors in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C324–334. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00397.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu G, et al. Pregnane X receptor is SUMOylated to repress the inflammatory response. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:342–350. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.171744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Biswas A, et al. Acetylation of pregnane X receptor protein determines selective function independent of ligand activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sakiyama T, et al. Autoantibodies against ubiquitination factor E4A (UBE4A) are associated with severity of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:310–317. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Medina-Diaz IM, et al. Arsenite and its metabolites, MMA(III) and DMA(III), modify CYP3A4, PXR and RXR alpha expression in the small intestine of CYP3A4 transgenic mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;239:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bai A, et al. Novel anti-inflammatory action of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside with protective effect in dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute and chronic colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333:717–725. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.164954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lichti-Kaiser K, et al. A systematic analysis of predicted phosphorylation sites within the human pregnane X receptor protein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:65–76. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.157180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pondugula SR, et al. A phosphomimetic mutation at threonine-57 abolishes transactivation activity and alters nuclear localization pattern of human pregnane x receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:719–730. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Staudinger JL, et al. Post-translational modification of pregnane x receptor. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mizrahi M, Ilan Y. The gut mucosa as a site for induction of regulatory T-cells. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:1191–1202. doi: 10.2174/138161209787846784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nair MG, et al. Goblet cell-derived resistin-like molecule beta augments CD4+ T cell production of IFN-gamma and infection-induced intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 2008;181:4709–4715. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schote AB, et al. Nuclear receptors in human immune cells: expression and correlations. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:1436–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang J, Yan B. Photochemotherapeutic agent 8-methoxypsoralen induces cytochrome P450 3A4 and carboxylesterase HCE2: evidence on an involvement of the pregnane X receptor. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:13–22. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wallace K, et al. The PXR is a drug target for chronic inflammatory liver disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;120:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dubrac S, et al. Modulation of T lymphocyte function by the pregnane X receptor. J Immunol. 2010;184:2949–2957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pimentel M. Review of rifaximin as treatment for SIBO and IBS. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:349–358. doi: 10.1517/13543780902780175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang H, et al. Pregnane X receptor activation induces FGF19-dependent tumor aggressiveness in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3220–3232. doi: 10.1172/JCI41514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ouyang N, et al. Pregnane X receptor suppresses proliferation and tumourigenicity of colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1753–1761. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]