Abstract

We designed and synthesized a BODIPY-based probe (BAP-1) for the imaging of β-amyloid plaques in the brain. In binding experiments in vitro, BAP-1 showed excellent affinity for synthetic Aβ aggregates. β-Amyloid plaques in Tg2576 mouse brain were clearly visualized with BAP-1. In addition, the labeling of β-amyloid plaques was demonstrated in vivo in Tg2576 mice. These results suggest BAP-1 to be a useful fluorescent probe for the optical imaging of cerebral β-amyloid plaques in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, β-amyloid plaque, BODIPY, optical imaging

The formation of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques is a critical neurodegenerative change in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1,2 Since the imaging of Aβ plaques in vivo may enable the presymptomatic diagnosis of AD, several imaging technologies including positron emission tomography (PET),3−21 single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT),22−24 magnetic resonance imaging,25−28 and optical imaging29−33 have been applied for this purpose. In particular, several PET probes have shown the feasibility of imaging Aβ plaques in AD brains. PET imaging is an established clinical modality that provides good sensitivity deep in tissue. However, it is limited by a time-consuming data acquisition process, exposure to radioactivity, the need for expensive equipment and highly skilled personnel, and a relatively poor spatial resolution.

Conversely, optical imaging with fluorescent probes is a relatively new modality that offers real-time, nonradioactive, and, depending on the technique, high-resolution imaging,34 leading to a rapid, inexpensive, and nonradioactive drug screening system for AD. However, there have been fewer reports regarding the development of fluorescent probes than PET probes despite their significance, although AOI-987,29 NIAD-4,30 CRANAD-2,32 ANCA-11,35 and BMAOI36 have been reported for the imaging of Aβ plaques.

Compounds containing a boron dipyrromethane (BODIPY) scaffold have widespread applications as dyes, fluorescent probes in biological systems, and materials for incorporation into electroluminescent devices.37−40 Their broad utility is due to their high thermal and photochemical stability, chemical robustness, and tunable fluorescence properties. We have previously reported a dual SPECT/fluorescent probe based on the BODIPY scaffold, for the imaging of Aβ plaques in vivo.41 Despite good affinity for synthetic Aβ(1–42) aggregates and the clear labeling of Aβ plaques in sections of the mouse brain, the BODIPY-based probe was not suitable for imaging in vivo due to its poor uptake into the brain. Two other papers have reported BODIPY-based probes targeting Aβ plaques.42,43 However, these derivatives have not been applied to imaging in vivo perhaps due to their low brain uptake and short excitation/emission wavelength, though they showed high affinity for Aβ plaques in vitro. The findings of these previous studies suggested that additional structural changes may modify the properties of BODIPY derivatives to improve their suitability for imaging in vivo.

Many Aβ-imaging probes for PET applied in clinical trials possess a dimethylamino styryl group as a consensus structure as reported previously.3,22,44−46 Then, in the present study, we designed and synthesized a new BODIPY-based Aβ probe (BAP-1) with a dimethyamino styryl group which plays an important role in binding to Aβ aggregates. BAP-1 belongs to a class of dyes that are collectively called molecular rotors, where the dimethyl-aniline is the donor, and the BODIPY unit is the acceptor.47 This motif is typical of Aβ-imaging probes. Here, we report the in vitro and in vivo evaluation of BAP-1 as a new probe for the optical imaging of cerebral Aβ plaques.

Results and Discussion

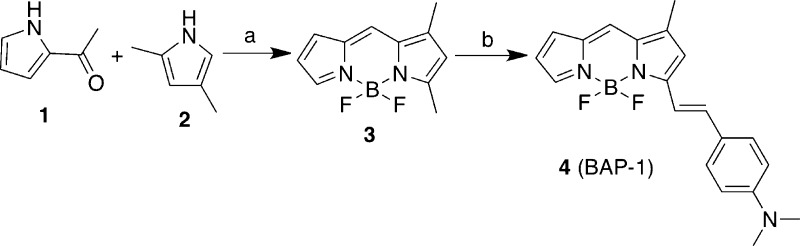

The target BODIPY derivative (BAP-1) was synthesized as shown in Scheme 1. Although the synthetic route for this compound has been reported,37 we made some modifications. The key step in the formation of the BODIPY backbone (3) was accomplished by the condensation of pyrrole 2-carboxyaldehyde (1) and 2,4-dimethylpyrrole (2) at low temperature, followed by the addition of BF3·OEt2 in a yield of 36.1%. Compound 4 (BAP-1) was successfully prepared by the condensation of 3 and 4-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde in the presence of piperidine and acetic acid (50.6% yield).

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route for BAP-1.

Reagents: (a) CHCl3, POCl3, BF3OEt2, Et3N; (b) toluene, 4-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde, piperidine, and AcOH.

First, we evaluated the fluorescent properties including absorption, excitation, emission wavelength, and quantum yield of BAP-1 in CHCl3. BAP-1 exhibited absorption, excitation, and emission wavelengths of 604, 614, and 648 nm, respectively, with a high fluorescent quantum yield (46.8%) (Table 1). Although BAP-1 showed slightly shorter wavelengths of excitation/emission at 614/648 nm than are appropriate for optical imaging in vivo, its high quantum yield was expected to enable the imaging of Aβ plaques in shallow areas of the mouse brain.

Table 1. Fluorescence Characterization of BAP-1a.

| Abs (nm) | Ex (nm) | Em (nm) | quantum yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 604 | 614 | 648 | 46.8 |

Absorbance, fluorescence excitation and emission, and quantum yield of BAP-1 were determined with 10 μM of the compound in CHCl3.

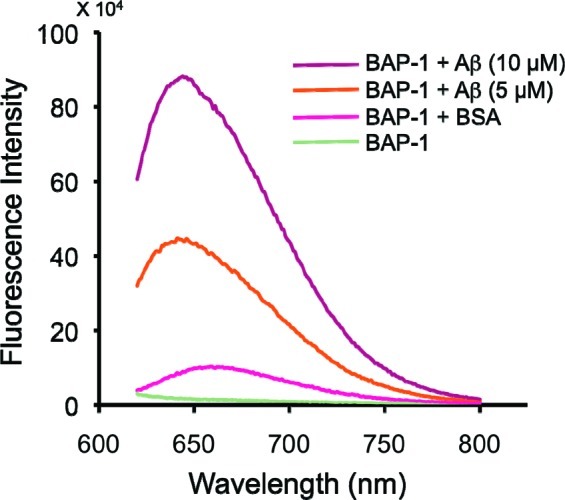

Furthermore, when BAP-1 existed in a solution containing Aβ aggregates or bovine serum albumin (BSA), its fluorescent intensity increased with the concentration of the aggregates, indicating affinity for Aβ aggregates (Figure 1). However, we found no significant change in fluorescence during the incubation with BSA, indicating that there is little interaction between BAP-1 and BSA.

Figure 1.

Fluorescence intensity of BAP-1 upon interaction with Aβ42 aggregates and BSA.

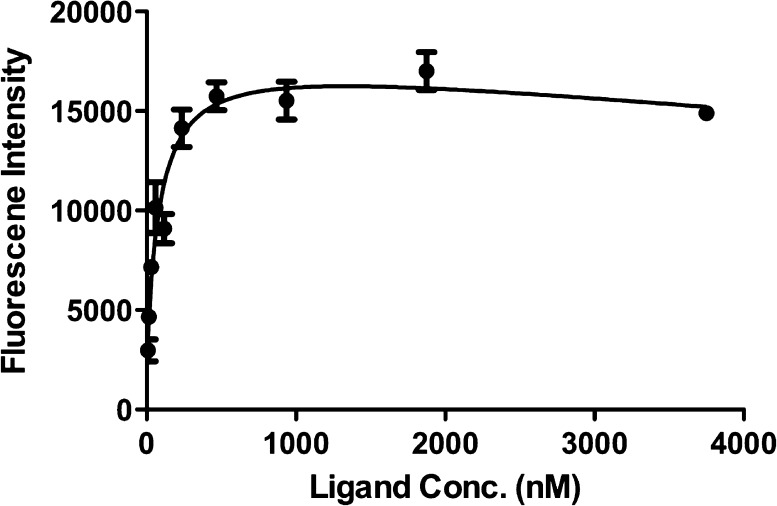

To quantify the affinity for Aβ aggregates, we measured the apparent binding constant (Kd) of BAP-1 by conducting a saturation assay (Figure 2). The fluorescent intensity of BAP-1 increased in a dose-dependent manner and was saturated at the higher concentration. Transformation of the saturation binding data to Scatchard plots provided linear plots, indicating that BAP-1 has one binding site on Aβ aggregates. BAP-1 showed excellent affinity for Aβ aggregates at a Kd value of 44.1 nM.

Figure 2.

Plot of the fluorescence intensity (Em = 673 nm) as a function of the concentration of BAP-1 in the presence of Aβ42 aggregates (2.2 μM) in solutions.

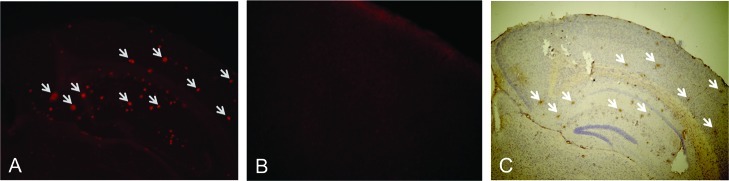

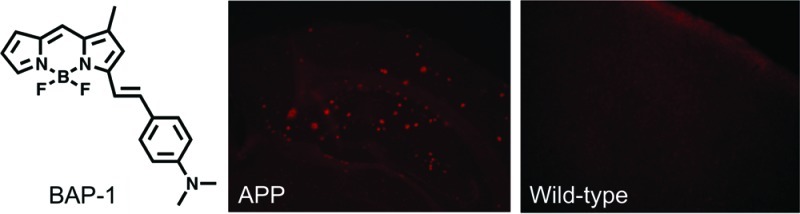

To confirm the affinity of BAP-1 for Aβ plaques in the brain, neuropathological fluorescent staining with BAP-1 was carried out using brain sections from Tg2576 mice (Figure 3). Tg2576 mice have been specifically engineered to overproduce Aβ plaques in the brain48 and frequently used to evaluate the specific binding of Aβ plaques in experiments in vitro and in vivo.49−51 Many fluorescent spots were observed in the brain sections of Tg2576 mice (32-month-old, female) (Figure 3A), while no spots were observed in the wild-type mice (29-month-old, female) (Figure 3B). The staining pattern was consist with that observed with thioflavin S (Figure 3C), a dye commonly used to stain Aβ plaques,52 indicating that BAP-1 shows specific binding to Aβ plaques in the mouse brain.

Figure 3.

Neuropathological staining of BAP-1 in a 10-μm section from a Tg2576 mouse brain (A) and a wild-type mouse brain (B). Labeled plaques were confirmed by staining of the adjacent section with thioflavin-S (C).

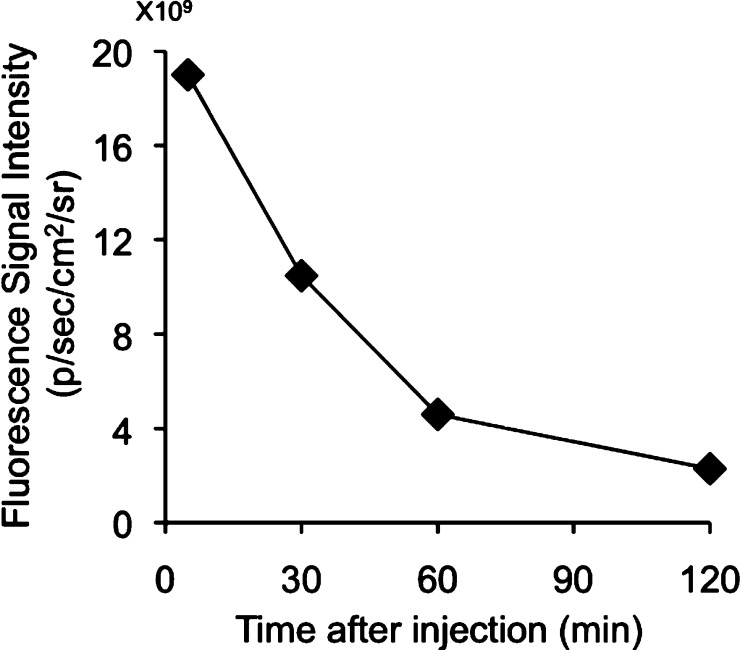

One important prerequisite for a probe for imaging of Aβ plaques in the brain is to penetrate the blood–brain barrier after an i.v. injection. Furthermore, the ideal amyloid-imaging agent should be rapidly washed out from normal brain tissue in addition to having a high brain uptake. Since normal brain tissue has no amyloid plaques to trap the agent, the washout should be fast, providing a higher signal-to-noise ratio in the AD brain. To test the uptake into and washout from the brain, we determined the fluorescent intensity in the brain after the injection of BAP-1 into a normal mouse. BAP-1 showed high initial brain uptake at 2 min postinjection, but the fluorescence that accumulated in the brain was rapidly eliminated, both of which are highly desirable properties for Aβ imaging probes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence intensity after injection of BAP-1 into ddY mice with an IVIS spectrum.

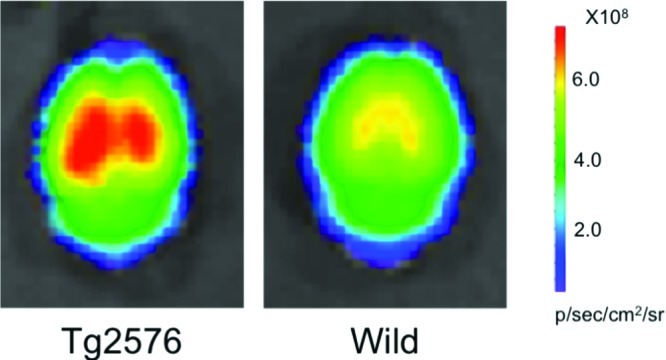

To evaluate the potential of BAP-1 in living brain tissue, we carried out experiments ex vivo using a Tg2576 mouse (25-month-old male) and a wild-type mouse (25-month-old male) as an age-matched control. The fluorescence in whole brains removed at 1 h postinjection of BAP-1 was much higher in the Tg2576 mouse than wild-type mouse (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the fluorescence intensity in the brain after the injection of BAP-1 into a Tg2576 mouse (A) and wild-type mouse (B).

To further evaluate what the higher fluorescence in the Tg2576 mouse brain was derived from, we prepared frozen sections from both brains and observed them with a fluorescence microscope. The brain sections from the Tg2576 mouse showed distinctive staining of Aβ plaques by BAP-1 (Figure 6A), while those from the wild-type mouse showed no such staining (Figure 6B). The staining pattern in the brain sections from the Tg2576 mouse was consistent with that observed on immunohistochemical staining with an antibody specific for Aβ(1–42) (BC05) as shown by arrows in Figure 6C. The results suggest that BAP-1 penetrated the blood–brain barrier and selectively labeled the Aβ plaques in the brain, as reflected by the biodistribution experiments and in vitro binding assays. To our knowledge, this is the first report that BODIPY-based probes can function as Aβ imaging probes in vivo. However, the excitation and emission wavelengths of BAP-1 were still shorter than the ideal wavelengths for optical imaging in vivo. Several BODIPY derivatives with longer wavelengths in the near-infrared region have recently been reported.53−55 On the basis of these findings, we may develop more appropriate BODIPY-based probes for the imaging of Aβ plaques in vivo.

Figure 6.

Ex vivo fluorescence observation of brain sections from a Tg2576 mouse (A) and wild-type mouse (B) after an injection of BAP-1. The presence of Aβ plaques in the section from the Tg2576 mouse was confirmed with immunohistochemical staining using a monoclonal Aβ antibody (C). Arrows show Aβ plaques stained by both BAP-1 (A) and immunohistochemical labeling (C).

We also conducted in vivo imaging experiments using Tg2576 mice and age-matched controls. However, we could not find a significant difference between the two groups, because the fluorescence of BAP-1 accumulated nonspecifically in the scalp in both groups. To improve nonspecific accumulation in the scalp, further modification of the BODIPY scaffold will be needed in the future.

In conclusion, we successfully designed and synthesized a BODIPY-based Aβ probe, BAP-1, for optical imaging in vivo. In binding experiments in vitro, BAP-1 showed high affinity for Aβ aggregates. BAP-1 clearly stained Aβ plaques in the mouse brain, reflecting its affinity for Aβ aggregates in vitro. In animal experiments using normal mice, BAP-1 displayed good uptake into and fast washout from the brain. In addition, ex vivo fluorescent staining of brain sections from Tg2576 mice after the injection of BAP-1 showed selective binding of Aβ plaques with little nonspecific binding. These findings suggest BAP-1 to be a useful molecular probe for the detection of Aβ plaques in AD brains and also provide useful information for the development of new BODIPY-based probes in the future.

Methods

General

All reagents were obtained commercially and used without further purification unless otherwise indicated. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a JEOL JNM-LM400 spectrometer with TMS as an internal standard. Coupling constants are reported in hertz. Multiplicity was defined by s (singlet), d (doublet), and m (multiplet). Mass spectra were obtained on a SHIMADZU GC-2010. HPLC was performed with a Shimadzu system (a LC-20AD pump with a SPD-20A UV detector, λ = 254 nm) using a Cosmosil C18 column (Nacalai Tesque, 5C18-AR-II, 4.6 × 150 mm) and acetonitrile/water (3/2) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The target compound was proven by this method to show >95% purity.

Chemistry

1,3-Dimethyl-4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene (3)

A solution of pyrrole 2-carboxyaldehyde (1) (368 mg, 3.87 mmol) and 2,4-dimethylpyrrole (2) (368 mg, 3.87 mmol) in CHCl3 (10 mL) was cooled to 0 °C. After POCl3 (360 μL) was added with caution, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. BF3·OEt2 (3 mL) and Et3N (3 mL) were added sequentially, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. The solution was washed with H2O and dried with Na2SO4. The solvent was removed, and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate = 2:1) to give 308 mg of 3 (36.1%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.28 (s, 3H), 2.59 (s, 3H), 6.16 (s, 1H), 6.43 (m, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (s, 1H), 7.65 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.3, 15.0, 116.2, 121.2, 124.8, 126.5, 132.5, 136.5, 138.9, 146.0, 163.1. MS m/z 220 (M+).

4,4-Difluoro-3-{(E)-{2-(4-dimethylaminophenyl)ethenyl}}-1-methyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene (4, BAP-1)

Compound 3 (120 mg, 0.55 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde (82 mg, 0.55 mmol) were dissolved in toluene (10 mL) with piperidine (350 μL) and AcOH (350 μL). The mixture was stirred under reflux for 1 h. After the mixture cooled to room temperature, H2O was added and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4 and filtered. The solvent was removed, and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate = 1:2) to give 97 mg of 4 (50.6%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.30 (s, 3H), 3.09 (s, 6H), 6.42 (m, 1H), 6.73 (m, 3H), 6.84 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (s, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.4, 40.1, 111.9, 113.4, 115.2, 117.4, 120.4, 123.4, 123.8, 130.1, 132.6, 136.2, 138.4, 141.9, 144.4, 151.7, 160.6. MS m/z 351 (M+).

Fluorescence Measurements Using Aβ(1–42) and BSA

A solid form of Aβ(1–42) was purchased from Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan). Aggregation was carried out by gently dissolving the peptide (0.25 mg/mL) in PBS (pH 7.4). The solution was incubated at 37 °C for 42 h with gentle and constant shaking. A mixture (100 μM of 10% EtOH) containing BAP-1 (10 μM) and Aβ(1–42) aggregates (0, 5, and 10 μM) or BSA (45 μg/mL) was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. After incubation, fluorescence emission spectra were collected between 645 and 800 nm with excitation at 614 nm.

Measurement of the Constant for Binding of Aβ Aggregates in Vitro

A mixture (100 μL of 10% EtOH) containing BAP-1 (final conc. 0–3.75 μM) and Aβ(1–42) aggregates (final conc. 2.2 μM) or BSA (10 μM) was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Fluorescence intensity at 673 nm was recorded (Ex: 614 nm). The Kd binding curve was generated by GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

In Vitro Fluorescent Staining of Mouse Brain Sections

The experiments with animals were conducted in accordance with our institutional guidelines and approved by the Kyoto University Animal Care Committee. The Tg2576 transgenic mouse (female, 32-month-old) and wild-type mouse (female, 29-month-old) were used as the AD model. After the mouse was sacrificed by decapitation, the brain was removed and sliced into serial sections 10 μm thick. Each slide was incubated with a 50% EtOH solution of BAP-1 (100 μM). Finally, the sections were washed in 50% EtOH for 1 min two times and examined using a microscope (BIOREVO BZ-9000, Keyence Corp., Osaka, Japan) equipped with a Texas Red filter set (excitation filter, Ex 540–580 nm; diachronic mirror, DM 595; barrier filter, BA 600–660). Thereafter, the serial sections were also stained with thioflavin S, a pathological dye commonly used for staining Aβ plaques in the brain, and examined using a microscope equipped with a GFP-BP filter set (excitation filter, Ex 450–490; diachronic mirror, DM 495; barrier filter, BA 510–560).

Ex Vivo Imaging of Brains from Normal Mice

A mixed solution consisting of 20% DMSO and 80% propylene glycol (100 μL) of BAP-1 (500 μM) was injected intravenously directly into the tail of ddY mice (5-week-old). The mice were sacrificed at 2, 10, 30, and 60 min postinjection. The brain was removed and weighed, and fluorescence images of brains were acquired with an IVIS SPECTRUM imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences Inc., Hopkinton, MA, USA) with a 0.1-s exposure (f-stop = 2) and a customized filter set (excitation, 605 nm; emission, 660 nm). The fluorescence intensity in each region of interest covering an entire tissue was expressed as photons/sec per g after the subtraction of background signals obtained in a region of interest set over an area without any tissue.

Ex Vivo Imaging Using a Tg2576 Mouse and an Age-Matched Control

A 25-month-old Tg2576 mouse and a wild-type mouse were intravenously injected with 200 μL of BAP-1 (133 μM, 10% EtOH). After 1 h, the mice were sacrificed, and the brain was removed and frozen in powdered dry ice. Fluorescence images of the brains were acquired with an IVIS SPECTRUM imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences Inc., Hopkinton, MA, USA) with a 0.1-s exposure (f-stop = 2) and a customized filter set (excitation, 605 nm; emission, 660 nm). The frozen blocks were sliced into serial sections, 20 μm thick, and examined using a microscope equipped with a Texas Red filter set. Thereafter, the presence and distribution of plaques in the same sections were confirmed with immunohistochemical staining using a monoclonal Aβ antibody (BC05) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Manami Ishikawa for helping with the synthesis of BAP-1 and Dr. Yoichi Shimizu for helping with the imaging in vivo.

Supporting Information Available

Data for 1H and 13C NMR spectra and HPLC analyses of BAP-1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

M.O. and H.S. designed all experiments. H.W. performed the synthetic chemistry work and in vitro and in vivo experiments. H.K. performed the synthetic chemistry work.

This study was supported by the Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers (NEXT Program) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Japan.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Klunk W. E. (1998) Biological markers of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 19, 145–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. (2000) Imaging Alzheimer’s amyloid. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 823–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Wilson A.; Nobrega J.; Westaway D.; Verhoeff P.; Zhuang Z. P.; Kung M. P.; Kung H. F. (2003) 11C-labeled stilbene derivatives as Aβ-aggregate-specific PET imaging agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Nucl. Med. Biol. 30, 565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff N. P.; Wilson A. A.; Takeshita S.; Trop L.; Hussey D.; Singh K.; Kung H. F.; Kung M. P.; Houle S. (2004) In-vivo imaging of Alzheimer disease β-amyloid with [11C]SB-13 PET. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 12, 584–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis C. A.; Wang Y.; Holt D. P.; Huang G. F.; Debnath M. L.; Klunk W. E. (2003) Synthesis and evaluation of 11C-labeled 6-substituted 2-arylbenzothiazoles as amyloid imaging agents. J. Med. Chem. 46, 2740–2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk W. E.; Engler H.; Nordberg A.; Wang Y.; Blomqvist G.; Holt D. P.; Bergstrom M.; Savitcheva I.; Huang G. F.; Estrada S.; Ausen B.; Debnath M. L.; Barletta J.; Price J. C.; Sandell J.; Lopresti B. J.; Wall A.; Koivisto P.; Antoni G.; Mathis C. A.; Langstrom B. (2004) Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann. Neurol. 55, 306–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo Y.; Okamura N.; Furumoto S.; Tashiro M.; Furukawa K.; Maruyama M.; Itoh M.; Iwata R.; Yanai K.; Arai H. (2007) 2-(2-[2-Dimethylaminothiazol-5-yl]ethenyl)-6-(2-[fluoro]ethoxy)benzoxazole: a novel PET agent for in vivo detection of dense amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Nucl. Med. 48, 553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. E.; Jeppsson F.; Sandell J.; Wensbo D.; Neelissen J. A.; Jureus A.; Strom P.; Norman H.; Farde L.; Svensson S. P. (2009) AZD2184: a radioligand for sensitive detection of β-amyloid deposits. J. Neurochem. 108, 1177–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn B. M.; Wensbo D.; Sandell J.; Sohn D.; Slivo C.; Pyring D.; Malmstrom J.; Arzel E.; Vallin M.; Bergh M.; Jeppsson F.; Johnson A. E.; Jureus A.; Neelissen J.; Svensson S. (2010) Synthesis and evaluation of 2-pyridylbenzothiazole, 2-pyridylbenzoxazole and 2-pyridylbenzofuran derivatives as 11C-PET imaging agents for β-amyloid plaques. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 1976–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agdeppa E. D.; Kepe V.; Liu J.; Flores-Torres S.; Satyamurthy N.; Petric A.; Cole G. M.; Small G. W.; Huang S. C.; Barrio J. R. (2001) Binding characteristics of radiofluorinated 6-dialkylamino-2-naphthylethylidene derivatives as positron emission tomography imaging probes for β-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 21, RC189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoghi-Jadid K.; Small G. W.; Agdeppa E. D.; Kepe V.; Ercoli L. M.; Siddarth P.; Read S.; Satyamurthy N.; Petric A.; Huang S. C.; Barrio J. R. (2002) Localization of neurofibrillary tangles and β-amyloid plaques in the brains of living patients with Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 10, 24–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koole M.; Lewis D. M.; Buckley C.; Nelissen N.; Vandenbulcke M.; Brooks D. J.; Vandenberghe R.; Van Laere K. (2009) Whole-body biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of 18F-GE067: a radioligand for in vivo brain amyloid imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 50, 818–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe R.; Van Laere K.; Ivanoiu A.; Salmon E.; Bastin C.; Triau E.; Hasselbalch S.; Law I.; Andersen A.; Korner A.; Minthon L.; Garraux G.; Nelissen N.; Bormans G.; Buckley C.; Owenius R.; Thurfjell L.; Farrar G.; Brooks D. J. (2010) 18F-flutemetamol amyloid imaging in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment: a phase 2 trial. Ann. Neurol. 68, 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen N.; Van Laere K.; Thurfjell L.; Owenius R.; Vandenbulcke M.; Koole M.; Bormans G.; Brooks D. J.; Vandenberghe R. (2009) Phase 1 study of the Pittsburgh compound B derivative 18F-flutemetamol in healthy volunteers and patients with probable Alzheimer disease. J. Nucl. Med. 50, 1251–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Oya S.; Kung M. P.; Hou C.; Maier D. L.; Kung H. F. (2005) F-18 polyethyleneglycol stilbenes as PET imaging agents targeting Aβ aggregates in the brain. Nucl. Med. Biol. 32, 799–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe C. C.; Ackerman U.; Browne W.; Mulligan R.; Pike K. L.; O’Keefe G.; Tochon-Danguy H.; Chan G.; Berlangieri S. U.; Jones G.; Dickinson-Rowe K. L.; Kung H. P.; Zhang W.; Kung M. P.; Skovronsky D.; Dyrks T.; Holl G.; Krause S.; Friebe M.; Lehman L.; Lindemann S.; Dinkelborg L. M.; Masters C. L.; Villemagne V. L. (2008) Imaging of amyloid β in Alzheimer’s disease with 18F-BAY94–9172, a novel PET tracer: proof of mechanism. Lancet Neurol. 7, 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe G. J.; Saunder T. H.; Ng S.; Ackerman U.; Tochon-Danguy H. J.; Chan J. G.; Gong S.; Dyrks T.; Lindemann S.; Holl G.; Dinkelborg L.; Villemagne V.; Rowe C. C. (2009) Radiation dosimetry of β-amyloid tracers 11C-PiB and 18F-BAY94–9172. J. Nucl. Med. 50, 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Oya S.; Kung M. P.; Hou C.; Maier D. L.; Kung H. F. (2005) F-18 stilbenes as PET imaging agents for detecting β-amyloid plaques in the brain. J. Med. Chem. 48, 5980–5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. R.; Golding G.; Zhuang Z.; Zhang W.; Lim N.; Hefti F.; Benedum T. E.; Kilbourn M. R.; Skovronsky D.; Kung H. F. (2009) Preclinical properties of 18F-AV-45: a PET agent for Aβ plaques in the brain. J. Nucl. Med. 50, 1887–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong D. F.; Rosenberg P. B.; Zhou Y.; Kumar A.; Raymont V.; Ravert H. T.; Dannals R. F.; Nandi A.; Brasic J. R.; Ye W.; Hilton J.; Lyketsos C.; Kung H. F.; Joshi A. D.; Skovronsky D. M.; Pontecorvo M. J. (2010) In vivo imaging of amyloid deposition in Alzheimer disease using the radioligand 18F-AV-45 (flobetapir F 18). J. Nucl. Med. 51, 913–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung H. F.; Choi S. R.; Qu W.; Zhang W.; Skovronsky D. (2010) 18F stilbenes and styrylpyridines for PET imaging of Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: a miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 53, 933–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Z. P.; Kung M. P.; Wilson A.; Lee C. W.; Plossl K.; Hou C.; Holtzman D. M.; Kung H. F. (2003) Structure-activity relationship of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines as ligands for detecting β-amyloid plaques in the brain. J. Med. Chem. 46, 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberg A. B.; Wintering N. A.; Clark C. M.; Plossl K.; Skovronsky D.; Seibyl J. P.; Kung M. P.; Kung H. F. (2006) Use of 123I IMPY SPECT to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease from controls. J. Nucl. Med. 47, 78P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maya Y.; Ono M.; Watanabe H.; Haratake M.; Saji H.; Nakayama M. (2009) Novel radioiodinated aurones as probes for SPECT imaging of β-amyloid plaques in the brain. Bioconjugate Chem. 20, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K.; Higuchi M.; Iwata N.; Saido T. C.; Sasamoto K. (2004) Fluoro-substituted and 13C-labeled styrylbenzene derivatives for detecting brain amyloid plaques. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 39, 573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M.; Iwata N.; Matsuba Y.; Sato K.; Sasamoto K.; Saido T. C. (2005) 19F and 1H MRI detection of amyloid β plaques in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatsubo T.; Yanagisawa D.; Morikawa S.; Taguchi H.; Tooyama I. (2010) Amyloid imaging using high-field magnetic resonance. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 9, 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa D.; Amatsubo T.; Morikawa S.; Taguchi H.; Urushitani M.; Shirai N.; Hirao K.; Shiino A.; Inubushi T.; Tooyama I. (2011) In vivo detection of amyloid β deposition using 19F magnetic resonance imaging with a 19F-containing curcumin derivative in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 184, 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintersteiner M.; Enz A.; Frey P.; Jaton A. L.; Kinzy W.; Kneuer R.; Neumann U.; Rudin M.; Staufenbiel M.; Stoeckli M.; Wiederhold K. H.; Gremlich H. U. (2005) In vivo detection of amyloid-β deposits by near-infrared imaging using an oxazine-derivative probe. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterov E. E.; Skoch J.; Hyman B. T.; Klunk W. E.; Bacskai B. J.; Swager T. M. (2005) In vivo optical imaging of amyloid aggregates in brain: design of fluorescent markers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 44, 5452–5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond S. B.; Skoch J.; Hills I. D.; Nesterov E. E.; Swager T. M.; Bacskai B. J. (2008) Smart optical probes for near-infrared fluorescence imaging of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 35(Suppl 1), S93–S98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran C.; Xu X.; Raymond S. B.; Ferrara B. J.; Neal K.; Bacskai B. J.; Medarova Z.; Moore A. (2009) Design, synthesis, and testing of difluoroboron-derivatized curcumins as near-infrared probes for in vivo detection of amyloid-β deposits. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 15257–15261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran C.; Zhao W.; Moir R. D.; Moore A. (2011) Non-conjugated small molecule FRET for differentiating monomers from higher molecular weight amyloid β species. PLos One 6, e19362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissleder R.; Mahmood U. (2001) Molecular imaging. Radiology 219, 316–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. M.; Dakanali M.; Capule C. C.; Sigurdson C. J.; Yang J.; Theodorakis E. A. (2011) ANCA: a family of fluorescent probes that bind and stain amyloid plaques in human tissue. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2, 249–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Guo T. L., Chojnacki J., Lee H. G., Wang X., Siedlak S. L., Rao W., Zhu X., and Zhang S. (2011) Bivalent ligand containing curcumin and cholesterol as a fluorescence probe for Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease, ACS Chem Neurosci., DOI: 10.1021/cn200122j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. S.; Kang N. Y.; Kim Y. K.; Samanta A.; Feng S.; Kim H. K.; Vendrell M.; Park J. H.; Chang Y. T. (2009) Synthesis of a BODIPY library and its application to the development of live cell glucagon imaging probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10077–10082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojida A.; Sakamoto T.; Inoue M. A.; Fujishima S. H.; Lippens G.; Hamachi I. (2009) Fluorescent BODIPY-based Zn(II) complex as a molecular probe for selective detection of neurofibrillary tangles in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6543–6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. N.; Wang H. L.; Liu F. Q.; Chen Y.; Tam P. K.; Yang D. (2009) BODIPY-based fluorescent probe for peroxynitrite detection and imaging in living cells. Org. Lett. 11, 1887–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. J.; Lee S. C.; Zhai D.; Ahn Y. H.; Yeo H. Y.; Tan Y. L.; Chang Y. T. (2011) Bodipy-diacrylate imaging probes for targeted proteins inside live cells. Chem. Commun. (Cambrideg, U.K.) 47, 4508–4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Ishikawa M.; Kimura H.; Hayashi S.; Matsumura K.; Watanabe H.; Shimizu Y.; Cheng Y.; Cui M.; Kawashima H.; Saji H. (2010) Development of dual functional SPECT/fluorescent probes for imaging cerebral β-amyloid plaques. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 3885–3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parhi A. K.; Kung M. P.; Ploessl K.; Kung H. F. (2008) Synthesis of fluorescent probes based on stilbenes and diphenylacetylenes targeting β-amyloid plaques. Tetrahedron Lett. 49, 3395–3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. W.; Alonso A.; Brown C. M.; Dzyuba S. V. (2010) Triazole-containing BODIPY dyes as novel fluorescent probes for soluble oligomers of amyloid Aβ1–42 peptide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 1455–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Kung M. P.; Hou C.; Kung H. F. (2002) Benzofuran derivatives as Aβ-aggregate-specific imaging agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Nucl. Med. Biol. 29, 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Haratake M.; Mori H.; Nakayama M. (2007) Novel chalcones as probes for in vivo imaging of β-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s brains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 15, 6802–6809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Yoshida N.; Ishibashi K.; Haratake M.; Arano Y.; Mori H.; Nakayama M. (2005) Radioiodinated flavones for in vivo imaging of β-amyloid plaques in the brain. J. Med. Chem. 48, 7253–7260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutharsan J.; Dakanali M.; Capule C. C.; Haidekker M. A.; Yang J.; Theodorakis E. A. (2010) Rational design of amyloid binding agents based on the molecular rotor motif. ChemMedChem 5, 56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K.; Chapman P.; Nilsen S.; Eckman C.; Harigaya Y.; Younkin S.; Yang F.; Cole G. (1996) Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 274, 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Cheng Y.; Kimura H.; Cui M. C.; Kagawa S.; Nishii R.; Saji H. (2011) Novel 18F-labeled benzofuran derivatives with improved properties for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of β-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s brains. J. Med. Chem. 54, 2971–2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Kagawa S.; Nishii R.; Kawashima H.; Saji H. (2010) Fluorinated benzofuran derivatives for PET imaging of β-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease brains. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 1, 321–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Kagawa S.; Nishii R.; Saji H. (2010) A novel 18F-labeled pyridyl benzofuran derivative for imaging of β-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s brains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 6141–6144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovronsky D. M.; Zhang B.; Kung M. P.; Kung H. F.; Trojanowski J. Q.; Lee V. M. Y. (2000) In vivo detection of amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 7609–7614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atilgan S.; Ozdemir T.; Akkaya E. U. (2008) A sensitive and selective ratiometric near IR fluorescent probe for zinc ions based on the distyryl-bodipy fluorophore. Org. Lett. 10, 4065–4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awuah S. G.; Polreis J.; Biradar V.; You Y. (2011) Singlet oxygen generation by novel NIR BODIPY dyes. Org. Lett. 13, 3884–3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y.; Watanabe K.; Nishiyabu R.; Hata R.; Murakami A.; Shoda T.; Ota H. (2011) Near-infrared absorbing boron-dibenzopyrromethenes that serve as light-harvesting sensitizers for polymeric solar cells. Org. Lett. 13, 4574–4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.