Abstract

The antigenic component of a common Lyme disease vaccine is recombinant outer surface protein A (rOspA) of Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb), the causative agent of Lyme disease. Coincidentally, patients with chronic, treatment-resistant Lyme arthritis develop an immune response against OspA, whereas those with acute Lyme disease usually do not. Treatment-resistant Lyme arthritis occurs in a subset of Lyme arthritis patients and is linked to HLA.DRB1*0401 (DR4) and related alleles. Recent work from our laboratory identified T cell crossreactivity between epitopes of OspA and lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1αL chain (LFA-1αL) in these patients. We generated a form of rOspA, FTK-OspA, in which the LFA-1αL/rOspA crossreactive T cell epitope was mutated to reduce the possible risk of autoimmunity in genetically susceptible individuals. FTK-OspA did not stimulate human or mouse DR4-restricted, WT-OspA-specific T cells, whereas it did stimulate antibody responses specific for WT-OspA that were similar to mice vaccinated WT-OspA. We show here that the protective efficacy of FTK-OspA is indistinguishable from that of WT-OspA in vaccination trials, as both C3H/HeJ and BALB/c FTK-OspA-vaccinated mice were protected from Bb infection. These data demonstrate that this rOspA-derived vaccine lacking the predicted cross-reactive T cell epitope, but retaining the capacity to elicit antibodies against infection, is effective in generating protective immunity.

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States, with ≈15,000 new cases each year (1). It is caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto (Bb), which is transmitted through the bite of infected ticks of the Ixodes family, primarily Ixodes scapularis in the Eastern and North central United States (2). Early symptoms of Lyme disease are nonspecific and can include malaise, fever, and chills. Because these symptoms are not specific to Lyme disease alone, combined with the fact that patients often do not recall being bitten (3), individuals may experience debilitating late manifestations of untreated Lyme disease weeks to months later, including musculoskeletal, cardiologic, and neurologic dysfunctions before diagnosis (4–6). Prevention is the best method for avoiding infection and subsequent disease-related complications. However, personal protective strategies have not always proven to be successful (7, 8), indicating a need for an efficacious vaccine.

Lyme disease vaccine development has primarily targeted the outer surface protein A (OspA) of Bb (9). This surface-expressed lipoprotein is significantly up-regulated in the tick midgut, and anti-OspA antibodies can passively protect mice against Bb infection (10). OspA-based vaccines function by killing the bacteria in the tick midgut, thereby blocking transmission of Bb to the human host (11, 12). The first Food and Drug Administration-approved form of the vaccine, LYMErix (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC), consisted of a lipidated recombinant OspA (rOspA) from Bb strain ZS7 adsorbed with aluminum hydroxide adjuvant. Clinical trials in adults showed a 76% efficacy in preventing symptomatic Lyme disease after three doses (13). In children, vaccination efficacy has been shown to be close to 100% (14, 15). A nonadjuvant, lipidated form of rOspA Lyme vaccine, ImuLyme [Pasteur Merieux Connaught USA, Swiftwater, PA (16)], was found to have 92% efficacy after three injections. Thus, vaccination with rOspA is an effective preventative measure against Lyme disease.

A consequence of disseminated Bb infection in up to 10% of infected individuals is a condition described as treatment-resistant Lyme arthritis (TRLA) (17). Arthritis persists in TLRA patients after long-term antibiotic therapy, suggesting that bacterial persistence is not necessary (18). Notably, in these patients, serum IgG reactivity to OspA correlates with the onset of prolonged episodes of arthritis (19). The incidence of TRLA has been correlated with the rheumatoid arthritis-associated MHC class II alleles, which include HLA-DRB1*0401 (DR4) (20). Our laboratory identified human lymphocyte function-associated antigen (hLFA)-1αL326–345 as a possible autoantigen in the context of DR4, based on sequence similarity to a region of OspA spanning amino acid residues 165–173 (OspA165–173) (21). By using an MHC class II DR4 tetramer specific for OspA164–176, we isolated T cells that were also hLFA-1αL326–345-reactive from the synovial fluid of DR4 homozygous patients with TRLA (22). These findings suggested that the pathogenesis of TRLA may be due to an autoimmune response triggered by OspA/hLFA-1αL crossreactivity. The observed T cell crossreaction between hLFA-1αL chain and OspA raised the concern that rOspA-based vaccines may trigger autoimmunity in susceptible individuals.

In this study, we report the generation of an rOspA vaccine, FTK-OspA, in which the putative cross-reactive T cell epitope, Bb OspA165–173, has been altered to resemble the corresponding peptide sequence of Borrelia afzelii. Human and mouse T cells specific for Bb OspA165–173 did not respond to FTK-OspA, whereas FTK-OspA was as effective as WT-OspA in generating protective antibody responses against Bb infection in both C3H/HeJ and BALB/c mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice. Six- to 8-week-old female C3H/HeJ and BALB/c mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. HLA-DR4-IE chimeric transgenic mice (23) were a gift from T. Forsthuber (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland) and were bred in our facility. All animal use protocols are approved by the accredited animal care and use committees at Tufts University and Texas A&M University Health Science Center Institute of Biosciences and Technology, respectively.

Bb. Low-passage Bb N40 or B31 were cultured in complete Barbour–Stoenner–Kelly (BSK) medium (Sigma) at 34°C and counted under darkfield microscopy.

Recombinant OspA Mutagenesis and Protein Production. OspA was amplified from a plasmid containing the OspA sequence from Bb strain B31 by using published primers (24). The 5′ leader sequence and lipidation site were omitted as described (25), and the resulting truncated product was cloned into the pGEX4T.1 GST-fusion expression vector (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed in two separate rounds by using the QuikChange PCR mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). First round primers: P6K-Fwd gctatgttcttgaaggaAAGctTactgctgaaaaaacaacattgg (HindIII); and second round primers P1FP2T-Fwd gaggttttaaaaggcTTCACGcttgaaggaaagcttac. Uppercase letters indicate substituted bases and underlined letters correspond to a restriction endonuclease site that was added. Recombinant FTK-OspA protein and empty vector control lysate (EV-Ctrl) were produced in Escherichia coli BL-21 and purified by using GST-Sepharose 4B bead slurry (Amersham Biosciences). Cleavage with thrombin released the rOspA proteins of ≈28 kDa from the beads and the GST moieties.

Antibody Assays. WT-OspA, FTK-OspA, or EV-Ctrl lysate were plated at 100 ng per well in 50 μl of 0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.2 overnight at 4°C. Plates were blocked with 1% BSA/0.5% Tween 20/0.02% sodium azide/PBS, pH 7.4 for 2 h at room temperature, or overnight at 4°C. Two-fold serial dilutions of mAb LA-2 or H5332 (26, 27) were plated at 100 μl per well and incubated at room temperature for 2.5 h. Antibody binding was detected with Zymax alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Zymed), diluted 1:5,000 in 100 μl per well and allowed to bind for 1 h at 21°C. Plates were developed with 100 μl per well p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) substrate in diethanolamine buffer. Reactions were stopped with 50 μl per well 2M NaOH. Data are expressed as OD405 with the background values subtracted.

LA-2-containing hybridoma supernatant (a generous gift of M. Simon, Max-Planck-Institut fur Immunobiologie, Freiburg, Germany) was purified by using HiTrap rProtein A column (Amersham Biosciences) for use in equivalency assays. The resulting antibody was biotin labeled with the mini-biotin-X-X protein labeling kit (Molecular Probes). mAbs were quantified by using both the BCA protein estimation kit (Pierce Biotechnology) and UV absorbance.

LA-2 equivalency describes the ability of serum antibodies to bind to and block the mAb LA-2 by competitive ELISA (26, 28, 29). In this assay, WT-OspA was bound to plates at 500 ng/ml in 100 μl of 0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.2 overnight at 4°C. Serial twofold dilutions of mouse sera were plated in triplicate overnight at 4°C; serial twofold dilutions of unlabeled LA-2 (starting at 1 μg/ml) were placed on each plate as a standard curve. Plates were washed and biotinylated LA-2 was plated at 300 ng/ml for 30 min at room temperature. Each plate contained positive and negative control pooled sera samples. Plates were washed, and NeutrAvidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Pierce Biotechnology) was added at 0.1 μg/ml in 100 μl for at least 30 min at room temperature. Plates were developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate.

OspA Immunization Vaccination and Bb infection. Six- to 8-week-old Female C3H/HeJ and BALB/c mice were immunized s.c. with 100 μl of containing adjuvant plus WT-OspA, FTK-OspA, EV-Ctrl, or adjuvant alone. Primary immunizations were prepared in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA), whereas subsequent immunizations were made by using incomplete Freund's adjuvant (30). C3H/HeJ mice were immunized on days 0, 14, and 28 with 10 μg of each protein or EV-Ctrl. Two weeks after the last immunization, mice were infected with 104 Bb N40 (passage 2) in the right hind footpad. BALB/c mice were immunized with 20 μg of each protein or EV-Ctrl on days 0 and 28, and were infected with 104 Bb B31 (passage 2) in 100 μl through intradermal injection at the base of the tail 2 weeks after the last immunization (31). Mock-infected controls were injected with 100 μl of BSK media and were not immunized with OspA.

Over the course of three weeks after Bb infection, ankle swelling was monitored by means of caliper measurements of the anterior-posterior tibiotarsal joint thickness. Mice were killed on the fourth week after infection. Bb in the blood or bladder of C3H/HeJ mice were detected by culturing two drops of aseptically harvested blood or whole bladders in 1.5 ml of complete BSK medium (Sigma) at 34°C for 2 weeks and then examining culture supernatant by darkfield microscopy. In experiments using BALB/c mice, vaccine efficacy was determined by harvesting and culturing the blood and tissues (ear, heart, bladder, and joints) 7 and 14 days post infection, respectively. Briefly, 50 μl of blood or tissue samples were cultured in 6 ml of BSK for 2 weeks at 34°C in a CO2-enriched atmosphere by using a GasPak chamber (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and were assessed for the presence of Bb by darkfield microscopy (30).

DNA Isolation and PCR. Genomic DNA extractions were performed on ear tissues harvested from infected C3H/HeJ mice by using a protocol adapted from Morrison et al. (32). Briefly, ear tissue was digested at 37°C for 2–4 h in 300 μl of 0.1% collagenase A in PBS, pH 7.4, then were digested overnight at 55°C after adding 300 μl of 0.2 mg/ml proteinase K/200 mM NaCl/20 mM Tris·HCl/50 mM EDTA/1% SDS. Extraction, ethanol precipitation, and resuspension were followed by digestion with RNase A, and an additional extraction and ethanol precipitation with a final resuspension in 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.5. Primers used for amplification of Bb recA and murine nidogen DNA were as published (32). PCR was performed by using 200, 20, and 2 ng of DNA, 0.5 μM recA primers, or 0.05 μM nidogen primers, and 27 μl of Platinum Taq Supermix (Invitrogen) in a final volume under the following conditions: at 95°C, 5 min to denature, followed by 33 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 69°C for 30 sec. Products were visualized on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels.

Murine T Cell Hybridomas (THys). OspA-specific DR4 (DR4–51 and DR4–38) and DR1 (L3C4)-restricted THy were generated as described (22, 33). For stimulation studies, 3 × 104 THy cells per well were cultured for 48 h in complete RPMI medium 1640/10% FCS with an equal number of antigen-presenting cells (APCs): DAP-DR4 and DAP-DR1 for DR4-and DR1-restricted hybridomas, respectively. Culture supernatants were harvested and relative quantities of IL-2 secretions were determined by sandwich ELISA using standard protocols (BD Pharmingen). Recombinant mouse IL-2 standards were used to determine the linear range of the assay.

Testing of Human T Cell Clones. T cells were isolated and cloned from synovial fluid of a DR4 homozygous patient as described (22, 33). For proliferation assays, autologous Epstein–Barr virus-transformed B cells were treated with mitomycin C (Sigma) for use as APCs. APCs and T cell clones were added at 2 × 104 cells with antigen as indicated. At 48 h, 100 μl of the medium was removed for cytokine analysis, and plates were pulsed with 0.5 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) of 3H-labeled thymidine for 18 h. Plates were counted on a β-plate scintillation counter (Perkin–Elmer, Boston). Data are expressed as Δ cpm, which is the mean cpm of wells with antigen minus the mean cpm of wells with medium alone. Cytokine analysis by using sandwich ELISAs were performed as described (33). Values were determined by comparing OD450 values to the standard curve generated for each plate.

Serum OspA-Specific Antibody Response. WT-OspA was plated at 1 μg/ml in 50 μl of 0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.2 and were allowed to bind overnight at 4°C. Plates were blocked with 200 μl of 1% BSA/0.5% Tween 20/0.02% sodium azide/PBS, pH 7.4 for 2 h at 21°C. Threefold serial dilutions of preinfection-immunized mouse sera were plated at room temperature for 2 h. Alkaline phosphatase-coupled detecting antibodies were plated at 100 μl per well for 1 h. Total IgG was detected with Zymax goat anti-mouse IgG (Zymed) at 1:2,000; isotype-specific detection antibodies were used at 1:500 (clonotyping system, Southern Biotechnology Associates). Plates were developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate as described above. Data are expressed as OD405 with the plate background values subtracted.

Results

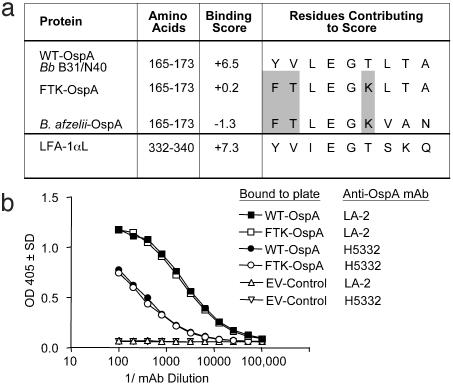

Generation of rOspA. The immunodominant DR4-restricted T cell epitope of Bb OspA, OspA165–173, is located in the thirteenth β-pleat of the central β-sheet structure (34). We designed a modification of this epitope to prevent its association with DR4 and thereby inhibit the activation of T cells specific for this region, by using a DR-binding algorithm (35). FTK-OspA was generated by making the substitutions Y165 to F, V166 to T, and T170 to K in WT-Bb OspA, thus resembling the peptide sequence found in B. afzelii (36), a Borrelia strain not associated with chronic arthritis (Fig. 1a). The DR4-binding algorithm predicted that the MHC-binding score would drop from +6.5 for WT-OspA, and to +0.2 in the FTK-OspA mutant (Fig. 1a). OspA from Bb strain B31, designated WT-OspA, and FTK-OspA were expressed as GST-fusion proteins and were purified by thrombin cleavage from the GST moiety. The resulting recombinant protein preparations were of the anticipated mass (≈28 kDa, data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Mutant FTK-OspA, created by altering MHC-binding OspA epitope, binds mAbs specific for WT-OspA. (a) Amino acid residues (165–173) that contribute to the predicted DR4-binding score for Bb OspA (WT-OspA, from Bb strains B31 or N40), FTK-OspA, B. afzelii OspA, and possible cross-reactive human protein, LFA-1αL (amino acids 332–340), are indicated. The amino acid substitutions used in FTK-OspA (highlighted in gray) were designed to decrease the DR4-binding score of that epitope, as predicted by published algorithms, but maintain a similar three-dimensional structure in the recombinant protein. (b) Serial dilutions of mAbs specific for two different WT-OspA epitopes, H5332 (N terminus-specific, open and filled circles) and LA-2 (C terminus-specific, open and filled squares) were added to WT-OspA and FTK-OspA, and EV-Ctrl-coated wells in a direct-binding ELISA. Data are expressed as the OD405 value of one dilution of antibody. No antibody binding to control lysate was detected.

Because the efficacy of OspA-derived vaccines is contingent on a potent anti-OspA humoral response, it was critical to demonstrate that the changes made in the T cell-reactive domain of FTK-OspA did not significantly alter the protective antibody response. We determined whether FTK-OspA was able to bind a panel of OspA-specific mAbs by ELISA. mAbs specific for either the OspA N terminus, H5332 (27), or the C terminus, LA-2 (26), 9B3D (37), and CIII.78 (38) bound to both the WT-OspA and mutated FTK-OspA in a similar fashion. No reactivity to EV-Ctrl lysate was detected (Fig. 1b and data not shown).

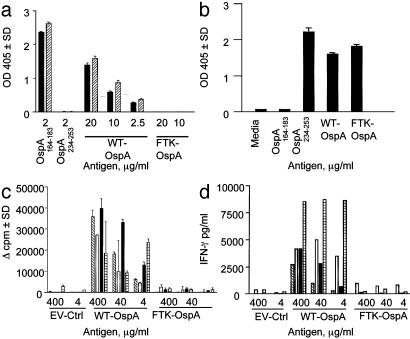

WT-OspA165–173-Specific T Cells Do Not Respond to FTK-OspA. We used a panel of DR4-restricted murine THy and human T cell lines to determine whether we had eliminated the DR4-restricted T cell response to FTK-OspA by mutating the amino acids 165–173 epitope. THy were generated from OspA-immunized murine MHC class II-deficient mice transgenic for chimeric mouse MHC I-Ed with human DR4 α- and β-chains (23). DR4-restricted THy specific for OspA165–173 produced significant levels of IL-2 in response to WT-OspA in a dose-dependent manner, but no IL-2 was detected in response to FTK-OspA or to EV-Ctrl (Fig. 2a). To determine whether FTK-OspA could stimulate L3C4, a DR1-restricted THy specific for an alternate epitope of OspA, amino acids 234–253, THy cells were stimulated with WT-OspA, FTK-OspA, or EV-Ctrl plus APC. L3C4 responded equally well to OspA234–253, WT-OspA, and FTK-OspA, but not to OspA165–173 (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

FTK-OspA does not stimulate OspA165–173-specific murine THy or human T cell clones. (a) Two DR4-restricted THy (filled bars, DR4–38; diagonally hatched bars, DR4–51) were generated from mice with transgenic human-mouse chimeric MHC class II molecules. THy specific for OspA165–173 were stimulated in quadruple with varied concentrations of WT-OspA, FTK-OspA, or OspA peptides 164–183 or 234–253, plus DR4 APC. Secreted IL-2 was measured by ELISA, and positive and negative controls were included on each plate. Data are expressed as OD405. (b) L3C4, a DR1-restricted THy specific for OspA234–253, was stimulated with OspA234–253, WT-OspA, FTK-OspA, EV-Ctrl, or OspA165–173 presented by DR1 APCs. Secreted IL-2 was measured by ELISA. Data are expressed as OD405.(c and d) Four human T cell clones were stimulated with various concentrations of WT-OspA, FTK-OspA, or EV-Ctrl plus autologous LCL APCs. (c) Proliferative response to antigen is measured as increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation. Each bar (diagonally hatched, open, filled, or crosshatched) represents a different T cell clone. The Δ-cpm is calculated by subtracting the mean media-stimulated cpm from the antigen-stimulated cpm. (d) Antigen-stimulated IFN-γ secretion was measured by ELISA from stimulated OspA-specific T cell clones from supernatants harvested at 48 h. IFN-γ values were determined by comparing OD values with a standard curve.

Additionally, we cultured WT-OspA165–173-specific human T cell clones derived from a DR4-homozygous TRLA patient (33) with WT-OspA, FTK-OspA, and EV-Ctrl. We reported (22) that these OspA165–173-specific clones were cross-reactive with hLFA-1αL326–345. WT-OspA stimulated strong proliferation (Fig. 2c) and induced secretion of high levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 2d), whereas neither FTK-OspA nor EV-Ctrl was stimulatory (Fig. 2 c and d). These results indicate that the FTK amino acid substitutions were sufficient to abrogate the response of WT-OspA-specific, DR4-restricted T cells to FTK-OspA.

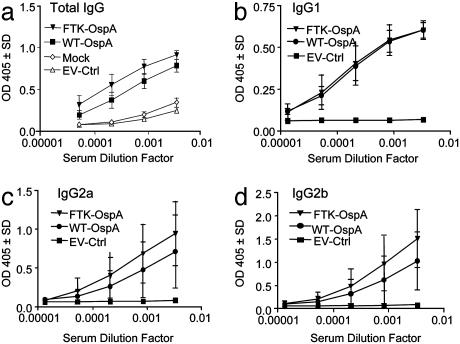

OspA Antibody Response Results in Protection Against Bb Infection. To determine the protective effect of immunization with FTK-OspA, we characterized the anti-OspA antibodies produced in vitro and in vivo. We first determined the level of anti-OspA antibodies produced in C3H/HeJ mice vaccinated with FTK-OspA or WT-OspA, or EV-Ctrl. Both WT- and FTK-OspA induced equivalent levels of WT-OspA-specific total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b (Fig. 3). Negligible antibody responses were detected after vaccination with EV-Ctrl (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

FTK-OspA stimulates anti-OspA serum antibody responses similar to those stimulated by WT-OspA. C3H/HeJ mice were immunized with FTK-OspA, WT-OspA, adjuvant alone (mock), or EV-Ctrl in three doses. Sera were collected 2 weeks after the final vaccine boost, and serial dilutions were assessed for WT-OspA-specific antibodies by isotype-specific ELISA. Data are expressed as OD405.(a) Total IgG. (b) IgG1. (c) IgG2a. (d) IgG2b. Data are combined from two experiments.

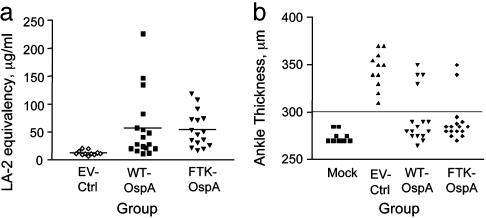

Next, we measured the ability of serum from immunized mice to competitively block binding of the WT-OspA-specific mAb, LA-2, to OspA to determine the “LA-2 equivalency,” an in vitro clinical correlate of a protective anti-OspA response (26). Serum antibodies that can block binding of a known quantity of biotin-labeled LA-2 mAb are quantitated by comparison with a standard curve of unlabeled LA-2. We demonstrated that both FTK- and WT-OspA-immunized mice produced similar levels of LA-2-equivalent antibodies, whereas EV-Ctrl-immunized mice produced background levels of LA-2-equivalent antibodies (Fig. 4a). These data indicate that immunization with FTK-OspA elicits similar LA-2 equivalency and, therefore, protective antibody levels, as WT-OspA.

Fig. 4.

FTK-OspA immunization generates antibodies with protective capacities similar to WT-OspA. (a) C3H-HeJ mice were immunized with FTK-OspA, WT-OspA, and EV-Ctrl as described, and the LA-2 equivalency (26) of serum antibodies was assessed by means of competitive ELISA with labeled LA-2 mAb. Data points indicate the LA-2 equivalency value of individual mice: ⋄, control; ▪, WT-OspA; ▴, FTK-OspA. Data are combined from two independent experiments. (b) FTK-OspA- and WT-OspA-vaccinated mice have reduced ankle swelling after Bb challenge. C3H/HeJ female mice were immunized with FTK-OspA, WT-OspA, or EV-Ctrl. Mice were challenged 2 weeks after the third vaccine dose by injection of Bb (EV-Ctrl, WT, and FTK) or BSK (mock) into the right hind footpad. Ankle swelling was monitored for 3 weeks after challenge. Each point represents the maximum ankle measurement recorded for each mouse after challenge with Bb. Data include results from two independent experiments.

Finally, to prove the in vivo protective efficacy of the FTK-OspA vaccine, C3H/HeJ mice were immunized with FTK-OspA, WT-OspA, or EV-Ctrl followed by intradermal challenge with Bb strain N40. Protection from Bb challenge was determined by maximal ankle thickness after challenge (Fig. 4b). Ankle thickness >300 μm was considered positive ankle swelling. The ability of FTK-OspA to protect mice from Bb infection was similar to that of recombinant WT-OspA, with 86% and 75% of mice protected from ankle swelling, respectively (Table 1). All mice immunized with EV-Ctrl developed ankle swelling >300 μm. Meanwhile, none of the mock-infected (BSK medium alone) mice developed ankle swelling (Fig. 4b and Table 1). Protection from Bb infection was substantiated by culture of spirochetes from blood or bladder tissue and by PCR for Bb RecA DNA. Outgrowth of Bb from tissue samples was positively correlated with ankle swelling data (Table 1). Similarly, PCR products corresponding to the recA gene of Bb were generated only from mice with ankle swelling (Table 1) and were not present when no ankle swelling was observed. No Bb could be cultured from mock-infected mice.

Table 1. WT-OspA- and FTK-OspA-vaccinated C3H/HeJ mice are protected against Bb infection.

| Group | Ankle swelling total* | Protection,† % | Day of onset‡ (n) | Bb outgrowth§ | Bb† PCR¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 4/16 | 75 | 14 (3), 17 (1) | 2/7 | 4/16 |

| FTK | 2/16 | 86 | 14 (2) | 0/6 | 2/16 |

| EV-Ctrl | 11/11 | 0 | 11 (4), 12 (5), 14 (2) | 6/6 | 11/11 |

| Mock | 0/11 | — | — | 0/5 | 0/6 |

The number of mice showing ankle swelling of >300 μm over 3 weeks of observation over total mice per group; C3H/HeJ mice were vaccinated and challenged as described above.

The percent of mice in each group that had no ankle swelling during 3 weeks of observation.

The day after infection that ankle swelling reached at least 300 μm.

The outgrowth of Bb from blood or bladder, expressed as number mice positive for Bb per total mice per group. Mice with confirmed infection or positive PCR results correlated precisely with animals showing ankle swelling.

Genomic DNA from ear tissue was amplified with primers specific for Bb recA and scored on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels, expressed as number of mice with recA product per total mice per group.

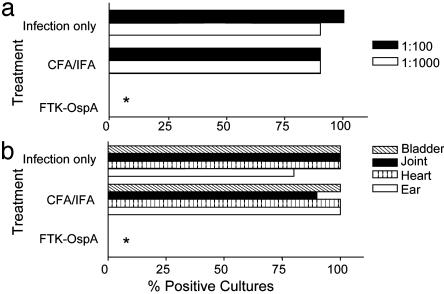

All strains of mice infected with Bb develop arthritis but with marked variations in disease severity. Mice of the H-2k,b,j,r,s (e.g., C3H/Hen) haplotypes develop severe to moderate infection and arthritis, whereas mice of the H-2d haplotype (BALB/c) more efficiently control Bb challenge and experience less severe pathology (39). Previous vaccine studies (40) demonstrated that WT-OspA could protect mice against infection with various Bb strains. To demonstrate that FTK-OspA could elicit protective immunity across different genetic backgrounds, BALB/c mice were vaccinated with FTK-OspA, adjuvant only, or were left untreated before intradermal infection with low-passage B31, a heterologous Bb strain (Fig. 5). Seven days after infection with Bb, blood was drawn, diluted, and cultured for Bb outgrowth. Whereas >75% of cultures from adjuvant (CFA/IFA)-treated and infection only control mice were positive for Bb growth, none of the FTK-OspA-immunized mice were positive (Fig. 5a, P < 0.0001; Fisher's exact test). Fourteen days after infection, mice were killed and tissues were cultured for the presence of Bb. There were no positive cultures from FTK-OspA-vaccinated mice, compared with 75–100% Bb positive ear, heart, bladder, or joint cultures from adjuvant only or infection only control mice (Fig. 5b, P < 0.0001; Fisher's exact test). These data suggest that FTK-OspA is as effective as WT-OspA in the prevention of symptomatic Bb infection in mice of different genetic backgrounds.

Fig. 5.

FTK-OspA vaccination abolishes outgrowth of Bb in BALB/c mice. After vaccination with FTK-OspA (n = 15), adjuvant (CFA/IFA, n = 10), or no treatment (infection only, n = 10), BALB/c mice were challenged with Bb B31. (a) At day 14 postinfection, blood was harvested and diluted 1:100 (filled bar) or 1:1,000 (open bar) and cultured in BSK medium to detect the outgrowth of Bb. (b) Joint (diagonal crosshatched bar), bladder (filled bar), heart (vertical crosshatched bar), and ear tissue (open bar) were harvested and cultured in BSK to detect the outgrowth of Bb. Data are expressed as percent positive Borrelia cultures for each pretreatment group. *, P < 0.0001 by Fisher's exact test.

Discussion

In this report, we describe the generation of FTK-OspA, a recombinant OspA molecule modified from Bb strain N40. FTK-OspA retained its ability to induce protective antibody responses, although lacking a potentially autoreactive T cell epitope. The T cell domain of WT-OspA was modified by substituting three residues from the N40 sequence with residues contained in a nonarthritogenic Bb strain, B. afzelii (Fig. 1a). These amino acid changes in the newly formed FTK-OspA epitope resulted in a significant reduction in antigen presentation by the DR4 APC, as predicted by a published DR4-binding algorithm (35). FTK-OspA did not stimulate epitope-specific, potentially autoreactive human or mouse T cells in vitro, yet it was as effective as WT-OspA in inducing protection against Bb infection (Fig. 2).

The modification of a major T cell epitope in a vaccine agent raises the concern that the necessary T cell help for humoral immunity will be compromised. Although the C3H/HeJ strain of mice has been well established for testing the efficacy of Lyme disease vaccine candidates, this strain cannot address this issue, because the primary T cell epitope in the context of H-2k is OspA179–193 (41). Thus, we used the class II-deficient, HLA-DR4 chimeric transgenic mice to determine whether OspA-specific antibody titers were equivalent with FTK-OspA and WT-OspA vaccination. Our findings that both total IgG and IgG1 subclass titers were similar after WT- and FTK-OspA immunization indicate that the T helper mediated class switching in these mice does not depend on OspA165–173 presentation (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In addition, our previous data indicate that the T cell response to OspA165–173 is predominantly an inflammatory Th1 response (21, 42). Thus, the FTK-OspA modification ablates a proinflammatory epitope in the context of DR4, while preserving structural integrity and remaining Th2 epitopes for the generation of protective immunity.

We generated this modified rOspA vaccine in response to concerns that the WT-OspA sequence used in previously developed vaccines contained an epitope that was cross-reactive with a region of hLFA-1αL. Vaccination of individuals who possess rheumatoid arthritis-associated MHC class II alleles, such as DR4, could potentially elicit autoreactive T cells after WT-OspA exposure. Because LFA-1αL is up-regulated at sites of inflammation, this self-antigen would be readily available to stimulate OspA-primed T cells at various sites in the body, including the vaccination site. Individuals in the clinical vaccine trial reported an increased incidence of localized pain after vaccine administration versus placebo administration; however, this reaction subsided in most recipients within 30 days (13). Further, the broad expression pattern of LFA-1αL could lead to a variety of adverse reactions that are not limited to arthritis.

Several studies have demonstrated an association between immunity to OspA and crossreactivity to hLFA-1αL in individuals of a select MHC background (22, 43, 44). In one report, the data did not support a link between reactivity to hLFA-1αL and clinical status (arthritis); unfortunately, the patient genetic backgrounds were not determined (45). However, in another study, arthritis was reported after vaccination in four males: two adults, and two children (46). By using data compiled from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System database (Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) to identify any unusual patterns of adverse events in OspA-vaccinated individuals, one report indicated a possible link between the DR4 allele and individuals suffering from serious Lyme vaccine-related illnesses (47). This connection may be confounded by bias in self-reporting. In an interesting development, the LYMErix vaccine has been removed from the market.

The incidence of Lyme disease in the United States remains high and this fact underlines the need for additional pharmaceutical approaches to controlling infection. OspA vaccines used in humans have demonstrated a 76% efficacy and function by inducing anti-OspA antibodies that block the transmission of Bb from the tick to the mammalian host. However, if Bb escape killing in the tick and are successfully transferred to the human host, they may escape elimination in the host because Bb down-regulate OspA expression as they make their way from the tick midgut to the salivary gland and into the host (48, 49). To avoid immune evasion in the host, an effective approach is to design a multivalent vaccine. Decorin-binding protein A, in combination with OspA, has been shown to confer a synergistic enhancement of protection against Bb infection (50). Additionally, developing a OspA-based combination vaccination with decorin-binding protein A may allow for an anamnestic response in the event of infection, because decorin-binding protein A is significantly up-regulated in the mammalian host (51). Other Bb proteins examined for vaccine efficacy include OspC (52), p35/Bbk32 (53), and VraA/BB116 (54). Multivalent vaccines may also result in increased protection against heterologous Bb strains (55), because crossprotection with unmodified OspA proteins has been difficult to achieve due to Bb heterogeneity (56). These combined data suggest that an optimal second generation Lyme disease vaccine could consist of FTK-OspA and one or two other vaccine candidates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lia Kim, Suzanne Hurta, Shelley Coulson, Diana Velez, and Monica Betancur for excellent technical assistance; Jennifer Coburn and Lisa Glickstein for reagents and advice; Markus Simon, Fred Kantor, and D. Denee Thomas for mAbs to OspA; and Anne Kane and the Center for Gastroenterology Research on Absorptive and Secretory Processes (GRASP) facility at Tufts for assistance with protein production. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AR45386, a grant from the Arthritis Foundation, the Eshe Fund, the Mathers Foundation, GRASP Grant MO1-RR0054 (to B.T.H.), National Institutes of Health Grant F32 AR08547 (to A.L.M.), and Centers for Disease Control Grant CCU618387 (to E.L.B.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: Bb, Borrelia burgdorferi; EV-Ctrl, empty vector lysate control; TRLA, treatment-resistant Lyme arthritis; OspA, outer surface protein A; rOspA, recombinant OspA; FTK-OspA, recombinant modified OspA; LFA-1αL, leukocyte function-associated antigen 1α, L chain; hLFA, human LFA; THy, T cell hybridoma; APC, antigen-presenting cell.

References

- 1.Orloski, K. A., Hayes, E. B., Campbell, G. L. & Dennis, D. T. (2000) Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. CDC Surveill. Summ. 49, 1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steere, A. C., Grodzicki, R. L., Kornblatt, A. N., Craft, J. E., Barbour, A. G., Burgdorfer, W., Schmid, G. P., Johnson, E. & Malawista, S. E. (1983) N. Engl. J. Med. 308, 733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sigal, L. H. (1997) in Textbook of Internal Medicine, ed. Kelly, W. M. (Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia), pp. 1178–1182.

- 4.Steere, A. C., Gibofsky, A., Patarroyo, M. E., Winchester, R. J., Hardin, J. A. & Malawista, S. E. (1979) Ann. Intern. Med. 90, 896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steere, A. C., Malawista, S. E., Bartenhagen, N. H., Spieler, P. N., Newman, J. H., Rahn, D. W., Hutchinson, G. J., Green, J., Snydman, D. R. & Taylor, E. (1984) Yale J. Biol. Med. 57, 453–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pachner, A. R. & Steere, A. C. (1987) Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. Ser. A 263, 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes, E. B., Maupin, G. O., Mount, G. A. & Piesman, J. (1999) J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 5, 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith, P. F., Benach, J. L., White, D. J., Stroup, D. F. & Morse, D. L. (1988) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 539, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadziene, A. & Barbour, A. G. (1996) Infection 24, 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon, M. M., Schaible, U. E., Kramer, M. D., Eckerskorn, C., Museteanu, C., Muller-Hermelink, H. K. & Wallich, R. (1991) J. Infect. Dis. 164, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Silva, A. M., Telford, S. R., III, Brunet, L. R., Barthold, S. W. & Fikrig, E. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fikrig, E., Telford, S. R., III, Barthold, S. W., Kantor, F. S., Spielman, A. & Flavell, R. A. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 5418–5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steere, A. C., Sikand, V. K., Meurice, F., Parenti, D. L., Fikrig, E., Schoen, R. T., Nowakowski, J., Schmid, C. H., Laukamp, S., Buscarino, C. & Krause, D. S. (1998) N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feder, H. M., Jr., Beran, J., Van Hoecke, C., Abraham, B., De Clercq, N., Buscarino, C. & Parenti, D. L. (1999) J. Pediatr. 135, 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sikand, V. K., Halsey, N., Krause, P. J., Sood, S. K., Geller, R., Van Hoecke, C., Buscarino, C. & Parenti, D. (2001) Pediatrics 108, 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigal, L. H., Zahradnik, J. M., Lavin, P., Patella, S. J., Bryant, G., Haselby, R., Hilton, E., Kunkel, M., Adler-Klein, D., Doherty, T., et al. (1998) N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steere, A. C., Schoen, R. T. & Taylor, E. (1987) Ann. Intern. Med. 107, 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klempner, M. S., Hu, L. T., Evans, J., Schmid, C. H., Johnson, G. M., Trevino, R. P., Norton, D., Levy, L., Wall, D., McCall, J., et al. (2001) N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalish, R. A., Leong, J. M. & Steere, A. C. (1993) Infect. Immun. 61, 2774–2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steere, A. C., Dwyer, E. & Winchester, R. (1990) N. Engl. J. Med. 323, 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross, D. M., Forsthuber, T., Tary-Lehmann, M., Etling, C., Ito, K., Nagy, Z. A., Field, J. A., Steere, A. C. & Huber, B. T. (1998) Science 281, 703–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trollmo, C., Meyer, A. L., Steere, A. C., Hafler, D. A. & Huber, B. T. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 5286–5291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito, K., Bian, H. J., Molina, M., Han, J., Magram, J., Saar, E., Belunis, C., Bolin, D. R., Arceo, R., Campbell, R., et al. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 2635–2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalish, R. A., Leong, J. M. & Steere, A. C. (1995) Infect. Immun. 63, 2228–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunn, J. J., Lade, B. N. & Barbour, A. G. (1990) Protein Expression Purif. 1, 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golde, W. T., Piesman, J., Dolan, M. C., Kramer, M., Hauser, P., Lobet, Y., Capiau, C., Desmons, P., Voet, P., Dearwester, D. & Frantz, J. C. (1997) Infect. Immun. 65, 882–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbour, A. G., Tessier, S. L. & Todd, W. J. (1983) Infect. Immun. 41, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Hoecke, C., Comberbach, M., De Grave, D., Desmons, P., Fu, D., Hauser, P., Lebacq, E., Lobet, Y. & Voet, P. (1996) Vaccine 14, 1620–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong, W., Wiesmuller, K. H., Kramer, M. D., Wallich, R. & Simon, M. M. (1996) Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 2749–2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown, E. L., Wooten, R. M., Johnson, B. J., Iozzo, R. V., Smith, A., Dolan, M. C., Guo, B. P., Weis, J. J. & Hook, M. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 107, 845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanson, M. S., Cassatt, D. R., Guo, B. P., Patel, N. K., McCarthy, M. P., Dorward, D. W. & Hook, M. (1998) Infect. Immun. 66, 2143–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrison, T. B., Ma, Y., Weis, J. H. & Weis, J. J. (1999) J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 987–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer, A. L., Trollmo, C., Crawford, F., Marrack, P., Steere, A. C., Huber, B. T., Kappler, J. & Hafler, D. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11433–11438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, H., Dunn, J. J., Luft, B. J. & Lawson, C. L. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 3584–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammer, J., Bono, E., Gallazzi, F., Belunis, C., Nagy, Z. & Sinigaglia, F. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 180, 2353–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balmelli, T. & Piffaretti, J. C. (1995) Res. Microbiol. 146, 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Comstock, L. E., Fikrig, E., Shoberg, R. J., Flavell, R. A. & Thomas, D. D. (1993) Infect. Immun. 61, 423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bockenstedt, L. K., Fikrig, E., Barthold, S. W., Kantor, F. S. & Flavell, R. A. (1993) J. Immunol. 151, 900–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaible, U. E., Kramer, M. D., Wallich, R., Tran, T. & Simon, M. M. (1991) Eur. J. Immunol. 21, 2397–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fikrig, E., Barthold, S. W., Kantor, F. S. & Flavell, R. A. (1990) Science 250, 533–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bockenstedt, L. K., Fikrig, E., Barthold, S. W., Flavell, R. A. & Kantor, F. S. (1996) J. Immunol. 157, 5496–5502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gross, D. M., Steere, A. C. & Huber, B. T. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 1022–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steere, A. C., Falk, B., Drouin, E. E., Baxter-Lowe, L. A., Hammer, J. & Nepom, G. T. (2003) Arthritis Rheum. 48, 534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steere, A. C., Gross, D., Meyer, A. L. & Huber, B. T. (2001) J. Autoimmun. 16, 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalish, R. S., Wood, J. A., Golde, W., Bernard, R., Davis, L. E., Grimson, R. C., Coyle, P. K. & Luft, B. J. (2003) J. Infect. Dis. 187, 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose, C. D., Fawcett, P. T. & Gibney, K. M. (2001) J. Rheumatol. 28, 2555–2557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lathrop, S. L., Ball, R., Haber, P., Mootrey, G. T., Braun, M. M., Shadomy, S. V., Ellenberg, S. S., Chen, R. T. & Hayes, E. B. (2002) Vaccine 20, 1603–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang, F. T., Nelson, F. K. & Fikrig, E. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 196, 275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohnishi, J., Piesman, J. & de Silva, A. M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 670–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanson, M. S., Patel, N. K., Cassatt, D. R. & Ulbrandt, N. D. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 6457–6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anguita, J., Samanta, S., Revilla, B., Suk, K., Das, S., Barthold, S. W. & Fikrig, E. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 1222–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong, W., Stehle, T., Museteanu, C., Siebers, A., Gern, L., Kramer, M., Wallich, R. & Simon, M. M. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 12533–12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fikrig, E., Barthold, S. W., Sun, W., Feng, W., Telford, S. R., III, & Flavell, R. A. (1997) Immunity 6, 531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Labandeira-Rey, M., Baker, E. A. & Skare, J. T. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69, 1409–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Straubinger, R. K., Dharma Rao, T., Davidson, E., Summers, B. A., Jacobson, R. H. & Frey, A. B. (2001) Vaccine 20, 181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luft, B. J., Dunn, J. J. & Lawson, C. L. (2002) J. Infect. Dis. 185, S46–S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.