Abstract

A diverse range of neural cell types is generated from a pool of dividing stem and progenitor cells in an orderly manner during development. Little is known of the molecular and cellular biology underpinning the intrinsic control of this process. We have used a nonbiased method to purify populations of neural progenitor cells from the murine CNS to characterize the gene expression program of mammalian retinal progenitor cells. Analysis of these data led to the identification of a core set of >800 transcripts enriched in retinal progenitor cells compared to both their immediate postmitotic progeny and to differentiated neurons. This core set was found to be shared by progenitors in other regions of the developing CNS, with important regional differences in key functional families. In addition to providing an expression fingerprint of this cell type, this set highlights several key aspects of progenitor biology.

A wide range of neuronal and glial cell types is generated from a pool of multipotent progenitor cells during development in both vertebrates and invertebrates (1–3). Progenitor cells, defined here as cycling cells, of the CNS generate neurons in an order that is typically conserved for a given area of the CNS (4). A second property of CNS progenitor cells is their ability to integrate extracellular signals with their intrinsically defined cellular state to decide, or at least partially direct, the fates of their progeny (5, 6). In addition, the cell fate decisions made by progenitor cells differ at different developmental stages in the same tissue and also between different parts of the nervous system (7). Therefore, for example, retinal progenitor cells make certain cell types early in development, a different set of cell types late in development, and a completely different set of cell types compared to those found in other parts of the nervous system (8, 9). The production of different cell types at different times appears to derive from differences in the intrinsic properties of progenitor cells, referred to as their competency to make different cell types, and provides the basis for our current model of retinal development (6, 7).

Little is known of the cell and molecular biology of progenitor cells, or of the transcriptional networks that define their intrinsic states. Progenitor cells have several major functional differences from their postmitotic neuronal progeny, most notably the absence of neurites and pre- and postsynaptic specializations, and the presence of the machinery for cell division. Therefore, a detailed analysis not just of the genes expressed in progenitor cells, but of the genes preferentially expressed in these cells compared to their neuronal progeny, would shed some light on the underlying molecular biology of the properties outlined above. In addition, the identification of an expression profile characteristic of this cell type is a useful tool for future developmental studies.

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods are available in supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) Purification of Neural Progenitor Cells. Retinal, cortical, and cerebellar progenitor cells were purified by FACS of cells live-stained with the DNA-binding dye Hoechst 33042 into 2N and 4N populations. Total RNA extracted from these cells was reverse transcribed and amplified by PCR (SMART system, Clontech).

Microarray Production and Use. Microarrays were produced with 11,136 clones from the Brain Molecular Anatomy Project clone set (kind gift of B. Soares, University of Iowa, Ames) and 600 additional clones. PCR-amplified inserts were printed on glass slides on a QArray microarrayer (Genetix, Hampshire, U.K.). Pairs of labeled probes were prepared, hybridized, washed, and scanned as described (10).

Data Analysis. Details of microarray data extraction and normalization are included in the supporting information.

In Situ Hybridization. In situ hybridization was carried out as described (11).

Results and Discussion

Gene Expression in Purified Populations of Retinal Progenitor Cells. There are currently few known neural progenitor or stem cell-specific cell surface markers that can be used for sorting neural progenitor cells. Of those available, it is unclear how soon after cell cycle exit they are removed from the cell surface. Almost all dividing cells in neural tissue during development are neural stem and progenitor cells, with a small number of dividing vascular and connective tissue cells. Therefore, we used the nonbiased functional approach of purifying dividing cells from the developing retina based on their DNA content. Cells with twice the normal amount of cellular DNA (4N) are those cells that are in the late S/G2/M stage of the cell cycle, and are herein defined as progenitor cells. The fraction of cells with the normal amount of cellular DNA (2N) includes both postmitotic cells and those progenitor cells in the G1/early S stage of the cell cycle. Using this approach to purify cells from the developing neural retina yielded populations of cells >95% enriched for cells strongly positive for the progenitor marker nestin (Fig. 1; see supporting information for detailed methods).

Fig. 1.

Strategy adopted to identify of retinal progenitor cell-enriched transcripts. Cycling cells of the developing retina were FACS-purified based on DNA content, yielding one population enriched in progenitor cells (4N cells) and a second composed of progenitor cells and postmitotic neurons (2N cells). Gene expression was compared directly between the 2N and 4N populations, and also between the 4N population and adult brain (see text for details). Reproducible differences between progenitor cells and the reference used in each case were identified by using the significance analysis of microarrays algorithm (see text for details), and genes that passed this filter were then hierarchically clustered to visualize the data and confirm differential expression.

RNA was extracted from 2N and 4N cells isolated from three different stages of retinal development (embryonic days E15 and E18 and postnatal day 0). Because the typical yield of purified 4N cells from a single sort was between 5 × 104 and 2 × 105 cells, the extracted RNA was used to synthesize cDNA and this cDNA amplified by PCR (12). We have previously shown that this procedure is highly reproducible, and the expression data generated by this approach are consistent with in vivo expression measured by other methods (10). These cDNA pools were used to study gene expression in retinal progenitor cells by comparing gene expression between 4N cells and the 2N cells isolated from the same sample.

The ratio of progenitor cells to postmitotic neurons in the 2N sample changes over developmental time, with projections of ≈75% progenitor cells at E15, compared with <30% at postnatal day 0, as predicted from data on cycling cells from the rat retina (13). Thus, simply comparing 4N and 2N samples, particularly at earlier developmental stages, is unlikely to identify progenitor-enriched transcripts, although it does provide an informative data set for analysis of cell cycle-regulated genes. Therefore, 4N cell gene expression was also compared to a fixed reference of total adult brain, a tissue composed of neurons and glial cells. To control for dye-dependent biases within this system, four of the hybridizations were repeated with the fluorescent labels reversed. For all experiments, relative gene expression was measured by hybridization of fluorescently labeled samples to cDNA microarrays of ≈12,000 sequenced mouse cDNAs, including 11,136 generated by the Brain Molecular Anatomy Project (see http://trans.nih.gov/bmap/index.htm for details).

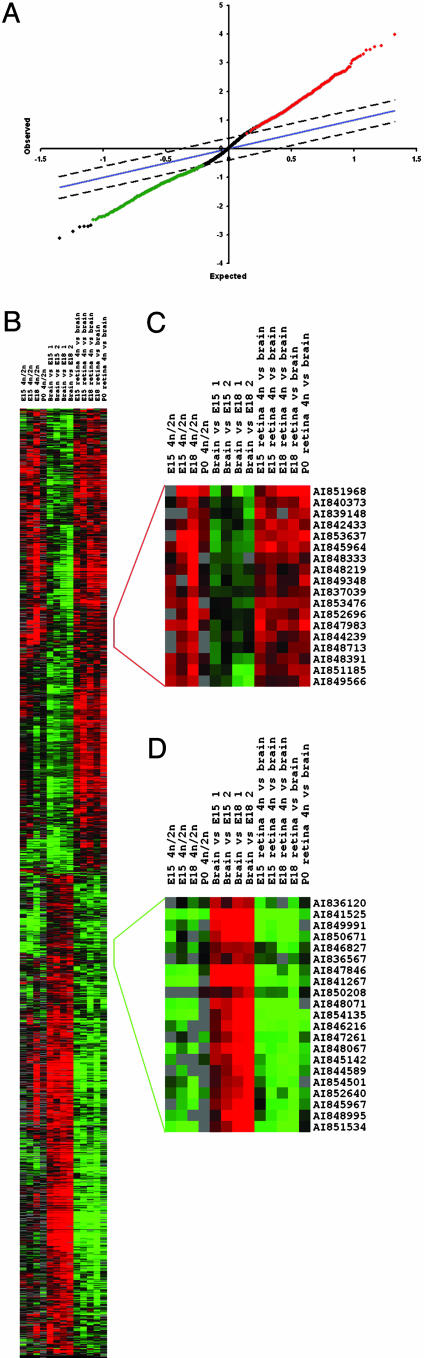

Data were analyzed by using the significance analysis of microarrays algorithm (14) to identify genes that were reproducibly found to be enriched in progenitor cells compared to both 2N cells and adult brain (Fig. 2). This analysis identified a subset of >1,700 genes differentially expressed between these cell types that was then hierarchically clustered to confirm differential expression and to facilitate visualization (Fig. 2). More than 800 genes were identified as progenitor cell-enriched, with the remaining 900 genes enriched in neurons. The progenitor cell-enriched genes include the majority of those known, such as the transcription factors Suppressor of Hairless, Pax6, Lhx2, and Chx10 and the cell cycle regulators Rb and cyclin D1. In contrast, those found enriched in postmitotic neurons include genes typically found in this cell type, such as synapse-associated proteins and ligand-gated ion channels (see supporting information for details).

Fig. 2.

Identification of a set of transcripts enriched in FACS-purified retinal progenitor cells. (A) Significance analysis of microarrays plot of the distribution of expected and observed values for gene expression ratios. Genes found to be reproducibly enriched in expression in 4N (progenitor) cells compared to brain and retinal 2N cells (neurons and progenitors) are highlighted in red, those expressed at a lower level in 4N cells are in green. (B) Hierarchical clustering of the results from A. (C) Detail of the hierarchical cluster analysis from A, showing genes enriched in expression in 4N cells compared to both brain and 2N cells. Note that, in addition to 4N/2N and 4N/brain hybridizations, brain/4N or dye-swap hybridizations were also included both as technical replicates and to control for dye-dependent biases within the hybridizations. In this and subsequent cluster diagrams, each row illustrates the gene expression ratios for a single gene, and each column represents a single array hybridization. The samples used for each hybridization are shown at the top of each column, with the Cy5-labeled sample listed first. By convention, the intensity of the color of each gene expression representation is proportional to the magnitude of the gene expression ratio, with red representing genes expressed at higher levels in the Cy5-labeled sample, green those expressed at a higher level in the Cy3-labeled sample, and black those expressed equally between the samples. (D) Detail of the hierarchical clustering of the results from A, showing genes enriched in expression in brain and 2N cells compared to 4N cells. This cluster includes several genes encoding synapse-associated proteins.

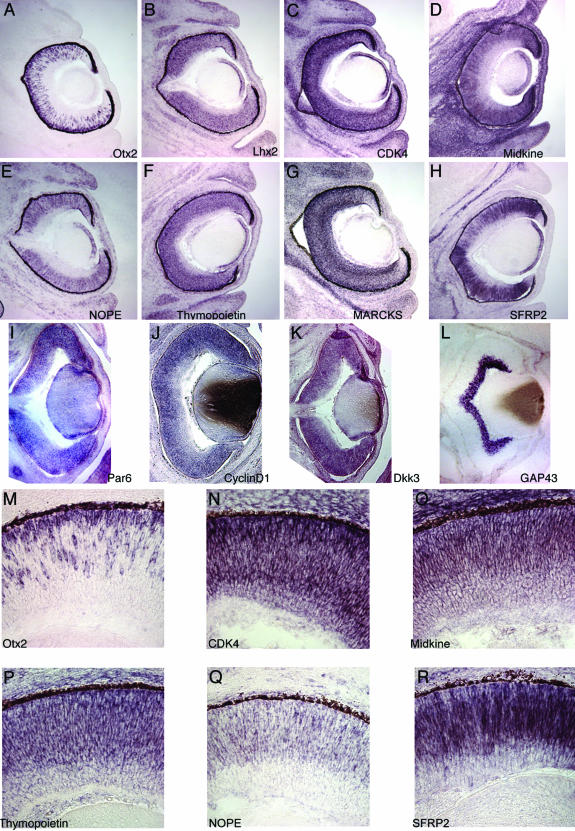

Expression Patterns of Retinal Progenitor Cell-Enriched Transcripts. To independently confirm the array data, the expression of a set of 11 transcripts was studied by in situ hybridization. The majority of these transcripts, 10 of 11, were found to be either highly expressed or enriched in progenitor cells (Fig. 3), with one, MARCKS, expressed in progenitor cells and ganglion cells at the stage studied. Almost all of the progenitor-enriched transcripts were found to be expressed in many, if not all, progenitor cells, although it was difficult to assess the percentage of progenitors expressing a gene by using this method on sections. However, three genes were expressed by noticeably fewer than the majority of progenitor cells (Fig. 3), including NOPE, SFRP2, and, most markedly, Otx2. Such expression may be due to heterogeneity among progenitor cell populations, which may reflect the stage of the cell cycle, or perhaps intrinsic differences that are unrelated to cell cycle.

Fig. 3.

Expression of genes identified as progenitor cell-enriched. In situ hybridization studies of the expression of a subset of the core set of retinal progenitor cell-enriched transcripts. All sections are from the E14.5 mouse retina. (A–L) Low-power views of expression of this subset of genes. Gene identifiers are as shown on each panel. Retinal progenitor cells occupy over three-quarters of the radial thickness of the neural retina at this stage with the innermost cells being ganglion cells, as shown by the neuron-specific GAP-43 staining in L. Note that although most genes are expressed in progenitor cells (for example, in A, B, and D), some genes are expressed in both progenitor cells and neurons (for example, in C and G). (M–R) High-power views of the progenitor cell-specific expression of a selection of genes, as labeled in each panel. Note the lack of expression of five of the six genes on the inner (vitreal) side of the retina populated by ganglion and amacrine cells, with CDK4 expressed at a low level within this region. Examples are also shown of genes with heterogeneous expression within progenitor cells, including Otx2 (M) and NOPE (Q).

Functional Annotation of Progenitor Cell-Enriched Transcripts. The set of genes identified as progenitor cell-enriched is functionally diverse, reflecting different aspects of progenitor cell biology. Of the 832 transcripts identified as progenitor-enriched, 190 have no annotation and do not map to any UniGene clusters. Many of these transcripts have poor quality sequences in GenBank. Of the transcripts that map to UniGene clusters, 386 encode 345 known genes, as indicated by their annotation, and the remaining 256 represent full-length clones or EST cluster assemblies of unknown function.

To take a systematic approach to interpreting the biological significance of this group of transcripts, we made use of the available Gene Ontology annotation (GO) to assign genes to functional classes (see Materials and Methods for details). Of the 439 known genes and full-length mRNAs (RIKEN clones), 353 had annotation in the cellular component branch of the GO structure (biological process and molecular function being the other two). Within the cellular component group, there are several dominant groupings at each level of annotation. At a basic level of annotation, 187 genes (70% of those annotated) were annotated as intracellular, with equal numbers (97 each) annotated as cytoplasmic and nuclear. At a higher level of annotation, 15% of genes were annotated as cytoskeleton, with 14% associated with nucleoplasm and 7% associated with chromatin. Annotation within the molecular function branch of the GO hierarchy reflected this relatively high representation of nuclear proteins, with 95 genes (31% of those annotated at this level of the GO hierarchy) annotated as having nucleic acidbinding activity.

Progenitors from Different Regions of the CNS Share a Common Expression Program. To investigate the similarities and differences in gene expression among progenitor cell populations from different regions of the CNS, a subsequent analysis of gene expression was carried out in purified progenitors from the developing cerebral cortex and cerebellum, using the same approach. Hierarchical cluster analysis of gene expression in cortical, cerebellar, and retinal FACS-purified 4N cells demonstrated that 4N cells from different regions of the developing CNS are highly similar (Fig. 4). Approximately 600 transcripts were identified as enriched in all three progenitor cell types, retinal, cortical, and cerebellar, compared to adult brain, and this set of genes contains almost all of the members of the set identified by the analysis of retinal progenitor cells alone, as discussed above (Fig. 4 and supporting information for details).

Fig. 4.

Identification of a core progenitor cell expression program expressed in diverse regions of the CNS. (A–D) Hierarchical cluster analysis of gene expression in progenitor (4N) cells from three regions of the developing CNS, compared to adult brain: retina, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum. The complete cluster analysis is shown in A. Examples are shown of genes enriched in retinal progenitor cells (B), genes commonly enriched in progenitor cells from all three regions (C), and enriched in brain (D). (E–H) In situ hybridization studies of the developmental expression within the forebrain of a subset of the core set of retinal progenitor cell-enriched transcripts also found enriched in cortical and cerebellar progenitor cells. All images are of coronal sections the E14.5 mouse forebrain. Genes are as marked on each panel. Note the high level of expression of each gene within the ventricular zone (VZ) of the developing cortex (arrowheads) and the sharply localized expression of SFRP2 at the junction between the cortical and subcortical VZs. MARCKS is expressed within postmitotic neurons in the cortical plate, in addition to its expression within cortical VZ progenitor cells.

A small number of genes showed differential expression among progenitor cells from different regions, and these were typically genes within functionally important families. For example, retinal progenitor cells express high levels of cyclinD1, whereas cortical and cerebellar progenitor cells expression cyclinD2, and retinal progenitors express the neurogenic basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor Math3, in contrast with the cortical expression of Math2 (Fig. 4).

In situ hybridization studies confirmed that genes initially identified as retinal progenitor-enriched and subsequently found to be commonly enriched in 4N cells from different regions of the CNS by array analysis, were expressed in cycling progenitor cell populations in those other regions of the developing CNS (in addition to the retina). For example, NOPE, SFRP2, and midkine are all highly expressed in the neocortical ventricular zone (Fig. 4). Furthermore, genes identified as progenitor-enriched in the retina but appearing expressed in both retinal progenitor cells and retinal neurons by in situ hybridization were confirmed as expressed in the neocortical progenitor cells, but also at a lower level in neocortical neurons, such as MARCKS (Fig. 4).

Biological Implications of the Set of Progenitor Cell-Enriched Transcripts. Direct inspection of the composition of the set of progenitor-enriched transcripts, in combination with the GO annotation, identified several groups of functional interest. Cell cycle genes are well represented as progenitor cell-enriched, including a number of cyclins and cyclin kinase inhibitors, as are genes encoding proteins involved in DNA replication, protein synthesis, and protein turnover. Together, these are indicative of cycling cells with relatively high rates of transcription and translation, as would be predicted for cells making and implementing developmental decisions. Consistent with this, this enrichment for cell cycle genes is also found on comparing mitotic fibroblasts (3T3 cells) with adult brain (F.J.L. and C.L.C., unpublished data).

Secondly, the expression of intercellular signaling molecules and receptors from a number of distinct families or pathways indicates the diversity of signaling systems used by progenitor cells. These include the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β family member bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) and the TGF-family antagonist follistatin-like and many distinct components of the Wnt pathway. BMP4 has important functions in dorsoventral patterning and in regulating cell death in the vertebrate retina (15, 16).

Of the Wnt pathway, the Wnt ligands Wnt-4, -7b, and -10a, the Wnt antagonists Dkk3 and SFRP2, and two key components of the intracellular Wnt signal transduction pathway, dishevelled-1 (17) and pygopus-2 (18, 19), are all expressed in retinal progenitor cells. The functions of Wnt signaling during retinal development are currently unclear. However, the Wnt-antagonist SFRP1 has recently been shown to have a role in regulating either progenitor cell fate decisions or cell cycle exit in the developing chick retina (20) and Dkk3 is highly expressed in the developing retina and in few other regions of the CNS (21). Given this coordinate expression of Wnt pathway components within retinal progenitor cells, it will be of interest to investigate further the possible functions of Wnts in regulating cell fate decisions within the retina.

A final noteworthy feature of the data are the large number of nuclear proteins identified. These include transcription factors, such as Pax6, Chx10, Six3 and Lhx2, and proteins involved in chromatin regulation, such as ATRX and chromobox homolog 3 (HP1-γ). The enrichment for the latter class of proteins, as well as the expression in both retinal and neocortical progenitors of the histone methyltransferase, enhancer of zeste-2 (F.J.L. and C.L.C., unpublished data) (22), suggests that active chromatin remodeling may be an important mechanism operating within neural progenitor cells. Overexpression of ATRX leads to aberrant proliferation of CNS progenitor cells, resulting in major abnormalities in cortical anatomy (23). Although epigenetic mechanisms are essential for regulating the multipotency of embryonic stem cells (see ref. 24 for review), and Ezh2, for example, has been shown to be essential for lymphopoiesis (25), the roles of epigenetic mechanisms in later development are less well understood. Histone modification and associated silencing are involved in the repression of neuronal gene expression in nonneural cells (26, 27). Thus, the enrichment of expression of this set of chromatin-associated and remodeling proteins in progenitor cells may indicate a role for epigenetic mechanisms in neural differentiation or in regulating the changing potency of neural progenitor cells over developmental time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Soares for providing the Brain Molecular Anatomy Project clone set, E. Robinson, R. Yung, and N. Smith for technical support, J. Trimarchi for GAP43 in situ hybridization data, members of the Cepko and Tabin laboratories for their constructive input, V. Cheung for initial training in microarray production and use, G. Sherlock for providing xcluster, and A. Dudley, S. Rowan, and E. Scraggs for critical readings of the manuscript. F.J.L. was a Research Associate and C.L.C. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. F.J.L. is a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellow. This work was supported by funds from National Institutes of Health Grant EY0 8064, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and The Wellcome Trust.

Abbreviations: FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; GO, gene ontology; En, embryonic day n.

References

- 1.Caviness, V. S., Jr., & Sidman, R. L. (1973) J. Comp. Neurol. 148, 141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McConnell, S. K. (1989) Trends Neurosci. 12, 342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid, A., Chiba, A. & Doe, C. Q. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 4653–4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlay, B. L. & Darlington, R. B. (1995) Science 268, 1578–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edlund, T. & Jessell, T. M. (1999) Cell 96, 211–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cepko, C. L., Austin, C. P., Yang, X., Alexiades, M. & Ezzeddine, D. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livesey, F. J. & Cepko, C. L. (2001) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaVail, M. M., Rapaport, D. H. & Rakic, P. (1991) J. Comp. Anat. 309, 86–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter-Dawson, L. D. & LaVail, M. M. (1979) J. Comp. Neurol. 188, 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livesey, F. J., Furukawa, T., Steffen, M. A., Church, G. M. & Cepko, C. L. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bao, Z. Z. & Cepko, C. L. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 1425–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matz, M., Shagin, D., Bogdanova, E., Britanova, O., Lukyanov, S., Diatchenko, L. & Chenchik, A. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 1558–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexiades, M. R. & Cepko, C. (1996) Dev. Dyn. 205, 293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tusher, V. G., Tibshirani, R. & Chu, G. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5116–5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakuta, H., Suzuki, R., Takahashi, H., Kato, A., Shintani, T., Iemura, S., Yamamoto, T. S., Ueno, N. & Noda, M. (2001) Science 293, 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trousse, F., Esteve, P. & Bovolenta, P. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 1292–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wharton, K. A., Jr. (2003) Dev. Biol. 253, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson, B., Townsley, F., Rosin-Arbesfeld, R., Musisi, H. & Bienz, M. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belenkaya, T. Y., Han, C., Standley, H. J., Lin, X., Houston, D. W. & Heasman, J. (2002) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 129, 4089–4101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esteve, P., Trousse, F., Rodriguez, J. & Bovolenta, P. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 2471–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monaghan, A. P., Kioschis, P., Wu, W., Zuniga, A., Bock, D., Poustka, A., Delius, H. & Niehrs, C. (1999) Mech. Dev. 87, 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao, R., Wang, L., Wang, H., Xia, L., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P., Jones, R. S. & Zhang, Y. (2002) Science 298, 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berube, N. G., Jagla, M., Smeenk, C., De Repentigny, Y., Kothary, R. & Picketts, D. J. (2002) Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, E. (2002) Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 662–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su, I. H., Basavaraj, A., Krutchinsky, A. N., Hobert, O., Ullrich, A., Chait, B. T. & Tarakhovsky, A. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballas, N., Battaglioli, E., Atouf, F., Andres, M. E., Chenoweth, J., Anderson, M. E., Burger, C., Moniwa, M., Davie, J. R., Bowers, W. J., et al. (2001) Neuron 31, 353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Battaglioli, E., Andres, M. E., Rose, D. W., Chenoweth, J. G., Rosenfeld, M. G., Anderson, M. E. & Mandel, G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41038–41045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.