Abstract

The candidate tumor suppressor fragile histidine traid (FHIT) is frequently inactivated in small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Mutations in the p53 gene also occur in the majority of SCLC leading to the accumulation of the mutant protein. Here we evaluated the effect of FHIT gene therapy alone or in combination with the mutant p53-reactivating molecule, PRIMA-1Met/APR-246, in SCLC. Overexpression of FHIT by recombinant adenoviral vector (Ad-FHIT)-mediated gene transfer in SCLC cells inhibited their growth by inducing apoptosis and when combined with PRIMA-1Met/APR-246, a synergistic cell growth inhibition was achieved.

Keywords: Tumor suppressor gene, SCLC, FHIT, p53

INTRODUCTION

Allelic loss of chromosome 3p is a frequent event in lung cancer, implying the presence of one or more potential tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) in this region. Homozygous deletions and loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) are found in more than 90% of all small cell lung cancer (SCLC) tumors and most of the genomic and genetic abnormalities are located in the 3p14–25 chromosomal stretch (1). The fragile histidine traid (FHIT) gene is located on chromosome arm 3p14.2 and encompasses the FRA3B fragile site, which is one of the most fragile sites in the human genome (2). Abnormalities in FHIT mRNA have been found in the majority of SCLC (3), and loss of FHIT expression is associated with a significant worse prognosis in patients with this cancer type (4). There are several lines of evidence suggesting that FHIT is a TSG. For example, overexpression of FHIT in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and head-and-neck carcinoma cells by a recombinant adenoviral vector (Ad-FHIT)-mediated gene transfer has been shown to induce significant tumor cell growth inhibition both in vitro and in vivo (5). Transfection of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells with FHIT plasmid vector induces apoptosis in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in vivo (6). Also, more than 50% of the FHIT-heterozygous (+/−) and homozygous (−/−) knock-out mice spontaneously develop tumors in a broad spectrum of tissues compared with 8% in FHIT (+/+) mice (7). Treatment of FHIT (+/−) mice with FHIT-expressing adenoviral or adeno-associated viral vectors after carcinogen exposure inhibits tumor development compared with untreated control mice (8), suggesting that FHIT gene therapy could constitute a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of various human cancers. However, the FHIT-mediated tumor suppressor function and its therapeutic application for the treatment of SCLC need to be further explored.

In addition to the lost or aberrant FHIT expression, inactive mutations in the p53 gene are also commonly found in more than 90% of SCLC (9). Since inactivation of multiple TSGs has been suggested to lead to lung cancer development (10), combination of two or more TSGs may constitute a more effective strategy in lung cancer treatment compared with single treatment strategy. Indeed, coexpression of p53 and FHIT in NSCLC cells has been shown to synergistically inhibit cancer cell growth both in vitro and in vivo (11). Also, in the NSCLC cell line, Calu-1, lacking both endogenous p53 and FHIT proteins, coexpression of these two genes leads to a more pronounced inhibition on tumor cell growth (12). These results suggest that a similar combination therapy with FHIT and p53 may more effectively induce SCLC cell death. However, due to the presence of high levels of mutant p53 proteins in SCLC cells (13), that may confer dominant-negative effects, therapeutic application with wild-type (wt) p53 gene replacement in SCLC patients may not be effective. Introduction of the novel mutant p53-reactivating small molecule, PRIMA-1Met/APR-246, which we henceforth will refer to only as PRIMA-1Met, into various human cancer cell types (14–24) and SCLC cells (13) has been shown to be effective and thus a clinically relevant therapeutic approach in tumors with a high level of mutant p53 expression.

Here we investigated the effect of FHIT overexpression by a recombinant adenoviral vector (Ad-FHIT)-mediated gene transfer on tumor cell growth and induction of apoptosis in SCLC cell lines with varied FHIT protein expression levels. We also explored the therapeutic effects of a combination treatment with Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met in these SCLC cell lines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

The origin and propagation of the SCLC cell lines used in this study has been previously described in detail (25). The two breast carcinoma cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7, and the human embryonic kidney cell line, HEK293, were obtained from ATCC and the non-small cell lung carcinoma, H1299, was provided by Dr. R. J. Christiano (Houston, TX). The cell lines MDA-MB-293, MCF-7, and H1299 were maintained as monolayer cultures, whereas the SCLC cell lines, DMS273, DMS53, GLC16, and NCIH69, were maintained as monolayer (DMS273 and DMS53) or suspension (GLC16 and NCIH69) cultures. The cell lines were cultured in DMEM (MDA-MB-293 and MCF-7), RPMI (H1299, NCIH69, and GLC16), or Waymouth (DMS273 and DMS53) medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 10 U/mL penicillin, and 10 µg/mL streptomycin. All tissue culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Taastrup, Denmark). All cells were maintained in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Reagent

PRIMA-1Met (APR-246) (2-hydroxy-methyl-2-methoxymethyl-aza-bicyclo[2.2.2]octan-3-one) was kindley provided by Aprea AB (Stockholm, Sweden). Stocks (100 mM) were prepared in DMSO and stored at −20°C. Dilutions were made in PBS.

RT-PCR

Total human RNA from normal tissues was purchased from Clontech (Glostrup, Denmark) and Ambion (Naerum, Denmark). Total RNA from SCLC cell lines and tumor xenografts was isolated using RNAeasy kit according to the manufacturer (Qiagen, Albertslund, Denmark); cDNA was synthesized with Superscript RT II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and amplified using Platinum TaqPolymerase (Invitrogen) with 25 cycles of amplification. Primers were purchased from DNA Technology (Risskov, Denmark).

Primers

FHIT: Sense: 5′-AACTGTCCTTCGCTCTTGTG, Antisence: TGAAAGTCTCCAGCCTTCCT; GAPDH: Sense: 5′-TCCATGCCATCACTGCCACCCA, Antisense: 5′-TCTTGTGCTCTTGCTGGGGCTG.

Adenoviral vector constructs

Three different recombinant adenoviral vectors were used: Ad-CMV-FHIT (Ad-FHIT), Ad-CMV-EV (Ad-EV), and Ad-CMV-eGFP (Ad-GFP). The Ad-FHIT vector has an expression cassette that contains the FHIT gene, whereas Ad-EV has an empty expression cassette and is used as a negative control. The construction of Ad-FHIT and Ad-EV is described elsewhere (5). The Ad-GFP vector, which expresses GFP, was purchased from Gene Transfer Vector Core (Iowa City, IA, USA) and used to study the transduction efficiency of the cell lines by viral vectors.

Western blot analysis

The protein level of FHIT in nontransduced or Ad-FHIT-transduced SCLC cell lines was determined by Western blot analysis. One day prior to transduction, DMS53, GLC16, and NCIH69 cells were plated in 6-well plates at 800.000 cells/well and DMS273 cells were plated at 130.000 cells/well. The cells were then transduced with Ad-FHIT at various multiplicity of infection (MOI, viral particles/cell) and harvested 3 or 5 days after transduction. Whole cell lysates were prepared by sonication in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, 1% NP40, 0.25% Na-deoxyholat, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with 0,1% SDS, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set III, and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail set II (Calbiochem, Herlev, Denmark). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk for 1 hr and subsequently incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary anti-body. The HRP signal was detected using Supersignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Herlev, Denmark) in an Autochemi system (UVP, AAhus, Denmark).

The antibodies used were anti-PARP (Cell Signaling, Glostrup, Denmark), anti-caspase-3 (Santa Cruz, Aarhus, Denmark), anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz), anti-FHIT (Invitrogen), HRP-conjugated swine anti-rabbit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse (Dako).

Cell viability assay

One day prior to transduction, DMS53, GLC16, and NCIH69 cells were plated in 96-well plates at 30.000 cells/well and DMS273 cells were plated at 5000 cells/well in 100 µL medium. The cells were then transduced with Ad-FHIT or Ad-EV at various MOI and either left untreated or treated with PRIMA-1Met at various concentrations. Cell viability was determined after 5 days by 2,3-bis[2-methoxy-4-nitro-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide inner salt (XTT) assay (Roche Diagnostics A/S, Hvidovre, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Median-effect/combination index analysis for determining the combined effects of Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met

The combined effects of Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met drug treatment in SCLC lines were determined by a median-effect principle (MEP) and its extension, combination index (CI) equation, using the CompuSyn software (ComboSyn, Paramus, NJ, USA) developed and described in details by Chou and Talalay (26–29). CI values at given effect levels (Fa) were calculated by actual combination effect data points and their simulated tumor cell growth inhibition curves with nonconstant ratios of Ad-FHIT (MOI) and PRIMA-1Met (µM) combinations, and the Fa-log(CI) plot was generated to quantitatively determine the potential synergism or antagonism on combination drug treatment; CI < 1, = 1, and >1 indicates synergism, additive effect, and antagonism, respectively. In the Fa-log(CI) plot, the synergism is indicated by a negative value (log(CI) < 0), antagonism is indicated by a positive value (log(CI) > 0), and additive effect is indicated by 0 (log(CI) = 0).

RESULTS

FHIT transcript and protein expression in SCLC cells

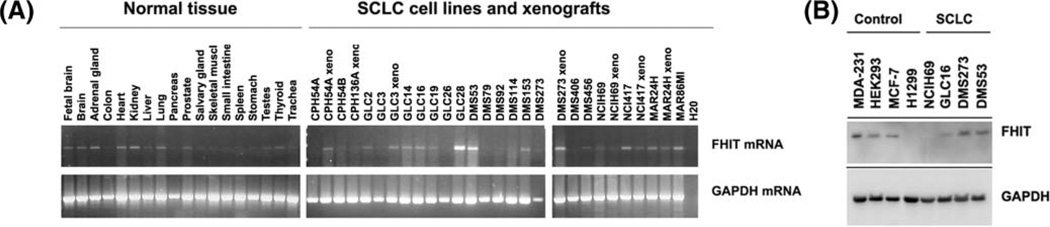

We performed a semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis to determine aberrations and levels of endogenous FHIT gene transcripts in a panel of SCLC cell lines as compared with those in normal tissues [see Figure 1(A)]. A normal sized FHIT mRNA transcript was detected in the majority of the SCLC cell lines, although levels of transcription varied among them. FHIT mRNA was detected in various normal tissues including lung [see Figure 1(A)]. Four SCLC cell lines, GLC16, NCIH69, DMS53, and DMS273, were chosen to further evaluate the expression level of endogenous FHIT protein. The three cell lines, MDA-231, HEK293, and MCF-7, were used as positive controls as they have previously been reported to express endogenous FHIT protein (30–32), whereas the H1299 cell line was included as a negative control due to lack of FHIT protein expression (33) [see Figure 1(B)]. The four SCLC cell lines expressed various levels of endogenous FHIT protein [see Figure 1(B)]. In the NCIH69 cell line, FHIT protein was undetectable despite the presence of FHIT mRNA [see Figure 1(A) and (B)]. These four SCLC cell lines with varied FHIT protein expression status were used to further study the biological effects of FHIT overexpression by Ad-FHIT-mediated gene transfer in vitro.

Figure 1.

FHIT mRNA and protein levels in SCLC. (A) FHIT transcript was analyzed in the indicated cell lines by semiquantitative RT-PCR. GAPDH was included as control for mRNA integrity and cDNA synthesis. (B) Western blot analysis of the level of endogenous FHIT protein in the SCLC cell lines, GLC16, NCIH69, DMS273, and DMS53. H1299 was included as a negative control, whereas MCF-7, HEK293, and MDA-MB-231 were included as positive controls. GAPDH was used as a protein loading control.

Adenoviral-mediated FHIT gene overexpression inhibits the growth of SCLC cells in vitro

We first determined the transduction efficiency of adenovirus in the four SCLC cell lines, GLC16, NCIH69, DMS53, and DMS273, using an adenovirus vector expressing GFP (Ad-GFP) as a reporter. The DMS53 cell line showed the highest transduction efficiency followed by DMS273 and GLC16 cells, whereas the NCIH69 cell line had the lowest transduction efficiency [see Figure 2(A) and (B)].

Figure 2.

Ad-FHIT reduces SCLC cell viability in the transduced cells. (A) The transduction efficiency of the four SCLC cells lines was assessed by transducing the cells with Ad-GFP at various MOIs for 72 hrs. (B) Transduction efficiency was evaluated after 72 hr in the GLC16 and NCIH69 cell lines at higher exposure time compared with (A). (C) The effect of Ad-FHIT on SCLC cell growth was determined by evaluating cell viability after 5 days of transduction at various MOI as compared with Ad-EV.

The effect of FHIT gene overexpression on SCLC cell growth was then investigated by determining cell viability 5 days after transduction. The time point at 5 days postranduction was chosen on the basis of previous studies showing a peak tumor suppressing effect of Ad-FHIT after 5 days of infection (5). As seen in Figure 2(C), the viability of SCLC cell lines, DMS53, DMS273, and GLC16, was substantially reduced with increasing MOI of Ad-FHIT as compared with cells transduced with an empty control adenovirus vector (Ad-EV). In the DMS53 and DMS273 cell lines, Ad-FHIT induced complete cell death at 125 and 500 MOI, respectively, whereas Ad-EV had no effect at a similar MOI. An almost 80% of reduction in cell viability was observed in the GLC16 cell line upon transduction with Ad-FHIT at 500 MOI whereas Ad-EV had a minimal effect. The NCIH69 cell line, however, had to be transduced with Ad-FHIT at a higher than 1000 MOI in order to achieve a similar 80% of cell killing. However, the viability of the NCIH69 cells transduced with the Ad-EV control vector at 1000 MOI or higher was also observed to be reduced [see Figure 2(C)]. Taken together, these results suggest that Ad-FHIT can inhibit SCLC cell growth independent of the presence of endogenous FHIT protein expression and the degree of cell growth inhibition is dependent on the transduction efficiency of the viral vector.

FHIT gene overexpression in the SCLC cells induces apoptosis

To see if the inhibitory effect of FHIT gene overexpression on SCLC cell growth was related to the activation of the apoptotic cell death pathways, we performed Western blot analysis to determine expression and activation of some key mediators in the apoptotic pathway in Ad-FHIT-transduced SCLC cells at different MOIs and time points of viral transduction. The four SCLC cell lines were transduced with Ad-FHIT at various MOIs ranging from 0 to 500 for either 3 or 5 days, and the level of exogenous FHIT protein expression was compared with that of nontransduced cells. Exogenously overexpressed FHIT proteins were detected in all Ad-FHIT-transduced cells compared with the nontransduced controls and showed an increased level of FHIT protein expression with an increased MOI and time points (see Figure 3). Overexpression of FHIT in the four SCLC cell lines induced the cleavage of PARP, which correlated with decreased levels of procaspase-3 (see Figure 3). The degree of PARP cleavage increased with an increased level of ectopic FHIT protein expression in these cells. These results suggest that the growth inhibitory effects of Ad-FHIT in the SCLC cells are mediated by FHIT overexpression and induction of apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of SCLC cells transduced with Ad-FHIT. Total levels of procaspase-3, PARP, and FHIT were evaluated by Western blot analysis in the indicated cells lines after transduction with Ad-FHIT at various MOIs ranging from 0 to 500 for 3 or 5 days. GAPDH was included as control for protein loading.

The combined effects of Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met on SCLC cell growth

Coexpression of FHIT and p53 has been demonstrated to induce a more pronounced inhibition on tumor cell growth both in vitro and in vivo in NSCLC cells compared with FHIT and p53 treatment alone (11, 12). In SCLC cells, p53 is frequently mutated and the mutant p53 proteins tend to accumulate (13) conferring dominant-negative effects in the cells. Ectopic expression of p53 may not efficiently override the dominant-negative effect of mutant p53 and, thus, render the anticancer effectiveness of the exogenous expression of wt p53 by a gene therapy approach in such SCLC cells. Therefore, we explored an alternative approach by combining Ad-FHIT with the small mutant p53-reactivating molecule, PRIMA-1Met, to see if an enhanced growth suppressive activity could be potentially achieved in SCLC cells. Two SCLC cell lines, GLC16 and DMS273, expressing high levels of mutant p53 (13), were transduced with Ad-FHIT or Ad-EV at various MOIs and then treated with different concentrations of PRIMA-1Met. Cell viability was then analyzed 5 days after transduction and drug treatment. As shown in Figure 4, the combination of Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met induced a more prominent cell growth inhibition at certain dose ranges compared with PRIMA-1Met, Ad-FHIT, Ad-EV, or Ad-EV combined with PRIMA-1Met. To see whether the growth inhibitory effect was synergistic, the combined effects of Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met as well as Ad-EV and PRIMA-1Met on tumor cell killing were evaluated by median-effect/CI analysis using averaged data from two independent experiments. Treatment of the SCLC cells with Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met induced a synergistic growth inhibitory effect at certain dose ranges and effect levels in the two SCLC cell lines (see Tables 1, 2, and Figure 5). In the DMS273 cell line, a synergistic effect was achieved when combing 25 µM PRIMA-1Met with Ad-FHIT at 125 MOI (CI value < 0) (see Table 1 and Figure 5). In the GLC16 cell line, a synergistic effect was achieved when combining 25 or 50 µM PRIMA-1Met with Ad-FHIT at 125 MOI or 50 µM PRIMA-1Met with Ad-FHIT at 50 MOI (see Table 2 and Figure 5). No synergistic effect was observed combing Ad-EV with PRIMA-1Met in any of the cell lines. Taken together, these results indicate that the combination of Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met inhibits SCLC cell growth synergistically at certain given effect dose levels and more effectively than either single agent treatment alone.

Figure 4.

The effect of Ad-FHIT and Ad-EV in combination with PRIMA-1Met on SCLC cell growth. The SCLC cell lines GLC16 and DMS273 were transduced with Ad-FHIT or Ad-EV at different MOIs from 0 to 500 and then treated with various concentrations of PRIMA-1Met ranging from 0 to 100 µM. Cell viability was determined 5 days after viral transduction and drug treatment.

Table 1.

Combination index (CI) and log(CI) values for nonconstant combination ratios in GLC16 cells

| Ad-EV + PRIMA-1Met (EV + PM) | Ad-FHIT + PRIMA-1Met (FT + PM) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRIMA-1Met (µM) | Ad-EV (MOI) | Effect (Fa) | CI | log(CI) | PRIMA-1Met (µM) | Ad-FHIT (MOI) | Effect (Fa) | CI | log(CI) |

| 25 | 62.5 | 0.35 | 1.65 | 0.22 | |||||

| 25 | 125 | 0.12 | 7.73 | 0.89 | 25 | 125 | 0.5 | 0.83 | −0.08 |

| 25 | 250 | 0.06 | 19.92 | 1.30 | 25 | 250 | 0.5 | 1.02 | 0.01 |

| 50 | 62.5 | 0.3 | 3.70 | 0.57 | 50 | 62.5 | 0.5 | 1.38 | 0.14 |

| 50 | 125 | 0.26 | 4.74 | 0.68 | 50 | 125 | 0.65 | 0.66 | −0.18 |

| 50 | 250 | 0.26 | 4.74 | 0.68 | 50 | 250 | 0.74 | 0.42 | −0.38 |

Table 2.

Combination index (CI) and log(CI) values for nonconstant combination ratios in DMS273 cells

| Ad-EV + PRIMA-1Met (EV + PM) | Ad-FHIT + PRIMA-1Met (FT + PM) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRIMA-1Met (µM) | Ad-EV (MOI) | Effect (Fa) | CI | log(CI) | PRIMA-1Met (µM) | Ad-FHIT (MOI) | Effect (Fa) | CI | log(CI) |

| 25 | 62.5 | 0.33 | 54.01 | 1.73 | |||||

| 25 | 125 | 0.27 | 71.29 | 1.85 | 25 | 125 | 0.99 | 0.30 | −0.53 |

| 25 | 250 | 0.04 | 605.58 | 2.78 | 25 | 250 | 0.82 | 6.11 | 0.79 |

| 25 | 500 | 0.04 | 605.58 | 2.78 | 25 | 500 | 0.95 | 1.51 | 0.18 |

Figure 5.

Median-effect/combination index analysis of the combined effects of Ad-FHIT and Ad-EV with PRIMA-1Met on tumor cell growth inhibition in the DMS273 and GLC16 cell lines. The combination effects were determined by a median-effect principle and combination index (CI) equation using the CompuSyn software program. The log(CI) values were plotted as a function of the fraction inhibition of cell growth at a given effect level (Fa from 1%–99% inhibition). In the log(CI) plot, synergism is indicated by a negative value, log(CI) < 0, antagonism is indicated by a positive value log(CI) > 0, and additive effect is indicated by 0, log(CI) = 0.

DISCUSSION

Genetic alterations leading to the impairment of several TSGs are critical events in the early developmental steps of lung cancer (10). In SCLC, the TSGs FHIT and p53 are frequently inactivated (10, 34) providing the rationale for studying the biological effects of these genes in these cancer cells.

In the present study, we evaluated the effect of adenoviral transfer of the human FHIT gene into four SCLC cells with varied levels of endogenous FHIT protein expression. Transduction of the SCLC cells with Ad-FHIT inhibited the growth of all four SCLC cell lines independent of the presence of endogenous FHIT protein. However, the effect was most pronounced in the DMS273 and DMS53 cells lines that showed a higher level of exogenous FHIT protein expression compared with that in NCIH69 and GLC16 cells. This is most likely due to a higher transduction efficiency in the DMS273 and DMS273 cells leading to a higher expression level of FHIT.

Several conflicting results have been reported on whether the effect of exogenous FHIT expression is dependent on the status of FHIT protein in the cells. For example, Dumon et al. (35) reported that the effect of ectopically expressed FHIT in pancreatic cells expressing endogenous FHIT protein is less prominent compared with cells lacking FHIT protein expression. Also, two other studies showed that FHIT overexpression has no effect on cell proliferation and growth in the head-and-neck carcinoma cell line, 22B, in normal human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC), and in the adenovirus 5 transformed human kidney cell line (HEK293), all these express endogenous FHIT protein (5, 36). In contrast to these findings, two independent groups failed to show any significant growth suppression of exogenous FHIT expression in various cancer cells either lacking or expressing endogenous FHIT protein, including the human cervical carcinoma cell line, HeLa, and various NSCLC cell lines (37, 38). However, in a study by Ishii and co-workers (30), adenoviral-vector-mediated FHIT expression resulted in tumor cell growth suppression in three out of seven esophageal cancer cell lines expressing no or very low levels of endogenous FHIT protein and of the three Ad-FHIT-responsive cell lines, two lacked endogenous FHIT protein expression. Also in the same study, exogenous expression of FHIT in HeLa cells showed marked apoptosis (30). It was therefore suggested that FHIT-mediated growth inhibition is not restricted to cancer cells with complete loss of FHIT expression but is dependent on the cancer cell type (30, 39), which is in accordance with the observations made in the present study. It seems that the biological effect of FHIT is dependent on the threshold level of the protein in the cells rather than the status of the endogenous FHIT protein expression. Indeed, the frequency of tumor development in FHIT +/− and −/− mice has been shown not to be significantly different, suggesting that FHIT protein may be haploinsufficient for tumor suppression in some tissues (7).

The growth suppressive effect of Ad-FHIT in the SCLC cell seemed to be due to FHIT-mediated induction of apoptosis as evidenced by the decrease in the level of procaspase-3 and induction of PARP cleavage, which are hallmarks of apoptosis. This is consistent with previous reports that FHIT induces apoptosis in cancer cells by activating both the death receptor and mitochondrial pathway (40, 41). Activation of both apoptotic pathways leads to the amplification of the apoptotic response (41). However, this amplification step is not necessary for FHIT activity, as apoptosis can still be achieved by FHIT in cells in which the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is blocked by overexpression of the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-x(L) (41).

It has previously been demonstrated that the adenoviral-vector-mediated cotransfer of FHIT and p53 in NSCLC cells with different p53 status synergistically suppresses the growth of these NSCLC cells in vitro and in vivo (11). Also, simultaneous restoration of FHIT and p53 in the NSCLC cell line, calu-1, using an inducible-gene expression system, leads to a pronounced inhibition of cell growth compared with FHIT and p53 alone (12) Therefore, combining p53 with FHIT could also result in a more effective tumor cell killing in SCLC cells, in which a high rate of p53 mutation is detected (13). However, as mutant p53 proteins tend to accumulate in SCLC cells (13) and confer dominant-negative effects leading to the inactivation of wt p53, we used the small molecule, PRIMA1-Met, which has shown to “reactivate”mutant p53 by restoring its wt conformation and tumor suppressing activity, subsequently resulting in apoptosis (14–24). The combination of Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met synergistically inhibited tumor cell growth at certain dose ranges in the DMS273 and GLC16 cells, while no synergistic effect could be observed when cells were cotreated with Ad-EV and PRIMA-1Met. The mechanism by which Ad-FHIT and PRIMA-1Met mediate a synergistic growth inhibition in the SCLC cells, however, needs to be elucidated. Nishizaki et al. (11) reported that the synergistic growth inhibition mediated by FHIT and wt p53 in NSCLC cells is due to the stabilization and accumulation of p53 as a result of FHIT-mediated down-regulation of MDM2. However, Cavazzoni and co-workers (12) could not detect upregulation of p53 or downregulation of MDM2 upon simultaneous expression of FHIT and p53. Therefore, additional studies on the mutual mechanism of action of FHIT and PRIMA-1Met are needed to clarify how the combination of FHIT and PRIMA-1Met leads to an enhanced SCLC cell death.

In summary, our results demonstrate a FHIT-mediated tumor suppressing activity by induction of apoptosis in SCLC cells when FHIT is overexpressed. When FHIT is combined with the small p53-reactivating molecule, PRIMA-1Met, a more prominent growth suppression is achieved than that when either agent is used alone. These results suggest that FHIT can serve as a potential therapeutic gene in the treatment of SCLC and if combined with small molecules that are capable of restoring the tumor suppressing function of mutant p53, a more effective treatment strategy can be achieved in SCLC, where p53 mutations are highly frequent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, SPORE P50CA70907 (Minna and Roth) and R01CA116322 (Ji), the A. P. Moeller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science, Novo Nordisk Foundation, Danish Cancer Society, Danish Medical Research Council, Aase and Ejnar Danielsen Foundation, Kathrine and Vigo Skovgaards foundation, and VFK Krebsforschung gGmbH in Germany. Roza Zandi was funded by grants from the Fulbright Commission, the Dagmar Marshall foundation, the Lundbeck foundation, and the University of Copenhagen.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackman DM, Johnson BE. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wali A. FHIT: doubts are clear now. Sci. World J. 2010;10:1142–1151. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sozzi G, Veronese ML, Negrini M, Baffa R, Cotticelli MG, Inoue H, Tornielli S, Pilotti S, De Gregorio L, Pastorino U, Pierotti MA, Ohta M, Huebner K, Croce CM. The FHIT gene 3p14.2 is abnormal in lung cancer. Cell. 1996;85:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rohr UP, Rehfeld N, Geddert H, Pflugfelder L, Bruns I, Neukirch J, Rohrbeck A, Grote HJ, Steidl U, Fenk R, Opalka B, Gabbert HE, Kronenwett R, Haas R. Prognostic relevance of fragile histidine triad protein expression in patients with small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji L, Fang B, Yen N, Fong K, Minna JD, Roth JA. Induction of apoptosis and inhibition of tumorigenicity and tumor growth by adenovirus vector-mediated fragile histidine triad (FHIT) gene overexpression. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3333–3339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu RH, Zheng LY, He DL, Tong J, Zheng LP, Zheng WP, Meng J, Xia LP, Wang CJ, Yi JL. Effect of fragile histidine triad gene transduction on proliferation and apoptosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3754–3758. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanesi N, Fidanza V, Fong LY, Mancini R, Druck T, Valtieri M, Rudiger T, McCue PA, Croce CM, Huebner K. The tumor spectrum in FHIT-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10250–10255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191345898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumon KR, Ishii H, Fong LY, Zanesi N, Fidanza V, Mancini R, Vecchione A, Baffa R, Trapasso F, During MJ, Huebner K, Croce CM. FHIT gene therapy prevents tumor development in Fhit-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3346–3351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061020098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen CL, Zandi R, Gjetting T, Cramer F, Poulsen HS. Specifically targeted gene therapy for small-cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:437–452. doi: 10.1586/era.09.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez-Cespedes M. Dissecting the genetic alterations involved in lung carcinogenesis. Lung Cancer. 2003;40:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishizaki M, Sasaki J, Fang B, Atkinson EN, Minna JD, Roth JA, Ji L. Synergistic tumor suppression by coexpression of FHIT and p53 coincides with FHIT-mediated MDM2 inactivation and p53 stabilization in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5745–5752. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavazzoni A, Galetti M, Fumarola C, Alfieri RR, Roz L, Andriani F, Carbognani P, Rusca M, Sozzi G, Petronini PG. Effect of inducible FHIT and p53 expression in the Calu-1 lung cancer cell line. Cancer Lett. 2007;246:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zandi R, Selivanova G, Christensen CL, Gerds TA, Willumsen BM, Poulsen HS. PRIMA-1Met/APR-246 induces apoptosis and tumor growth delay in small cell lung cancer expressing mutant p53. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(9):2830–2841. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bykov VJ, Issaeva N, Shilov A, Hultcrantz M, Pugacheva E, Chumakov P, Bergman J, Wiman KG, Selivanova G. Restoration of the tumor suppressor function to mutant p53 by a low-molecular-weight compound. Nat Med. 2002;8:282–288. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bykov VJ, Zache N, Stridh H, Westman J, Bergman J, Selivanova G, Wiman KG. PRIMA-1(MET) synergizes with cisplatin to induce tumor cell apoptosis. Oncogene. 2005;24:3484–3491. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bykov VJ, Issaeva N, Selivanova G, Wiman KG. Mutant p53-dependent growth suppression distinguishes PRIMA-1 from known anticancer drugs: a statistical analysis of information in the National Cancer Institute database. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:2011–2018. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.12.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen J, Vakifahmetoglu H, Stridh H, Zhivotovsky B, Wiman KG. PRIMA-1MET induces mitochondrial apoptosis through activation of caspase-2. Oncogene. 2008;27:6571–6580. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang T, Lee K, Rehman A, Daoud SS. PRIMA-1 induces apoptosis by inhibiting JNK signaling but promoting the activation of Bax. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Mao Y, Brandt-Rauf PW, Williams AC, Fine RL. Selective induction of apoptosis in mutant p53 premalignant and malignant cancer cells by PRIMA-1 through the c-Jun-NH2-kinase pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:901–909. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert JM, Moshfegh A, Hainaut P, Wiman KG, Bykov VJ. Mutant p53 reactivation by PRIMA-1MET induces multiple signaling pathways converging on apoptosis. Oncogene. 2010;29:1329–1338. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlot JF, Nicolier M, Pretet JL, Mougin C. Modulation of p53 transcriptional activity by PRIMA-1 and Pifithrin-alpha on staurosporine-induced apoptosis of wild-type and mutated p53 epithelial cells. Apoptosis. 2006;11:813–827. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-5876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nahi H, Merup M, Lehmann S, Bengtzen S, Mollgard L, Selivanova G, Wiman KG, Paul C. PRIMA-1 induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukaemia cells with p53 gene deletion. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi H, Lambert JM, Hautefeuille A, Bykov VJ, Wiman KG, Hainaut P, de Fromentel CC. In vitro and in vivo cytotoxic effects of PRIMA-1 on hepatocellular carcinoma cells expressing mutant p53ser249. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1428–1434. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang Y, Besch-Williford C, Hyder SM. PRIMA-1 inhibits growth of breast cancer cells by re-activating mutant p53 protein. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:1015–1023. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedersen N, Mortensen S, Sorensen SB, Pedersen MW, Rieneck K, Bovin LF, Poulsen HS. Transcriptional gene expression profiling of small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1943–1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou TC, Talaly P. A simple generalized equation for the analysis of multiple inhibitions of Michaelis–Menten kinetic systems. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:6438–6442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou TC, Talalay P. Generalized equations for the analysis of inhibitions of Michaelis–Menten and higher-order kinetic systems with two or more mutually exclusive and nonexclusive inhibitors. Eur J Biochem. 1981;115:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chou TC, Talalay P. Applications of the median-effect principle for the assessment of low-dose risk of carcinogens and for the quantitation of synergism and antagonism of chemotherapeutic agents. In: Harrap KR, Connors TA, editors. New Avenues in Developmental Cancer Chemotherapy. New York: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou TC. Quantitation of synergism and antagonism of two or more drugs by computerized analysis. In: Chou TC, Rideout DC, editors. Synergism and Antagonism in Chemotherapy. New York: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishii H, Dumon KR, Vecchione A, Trapasso F, Mimori K, Alder H, Mori M, Sozzi G, Baffa R, Huebner K, Croce CM. Effect of adenoviral transduction of the fragile histidine triad gene into esophageal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1578–1584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelley K, Berberich SJ. FHIT gene expression is repressed by mitogenic signaling through the PI3K/AKT/FOXO pathway. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:62–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popovici C, Basset C, Bertucci F, Orsetti B, Adelaide J, Mozziconacci MJ, Conte N, Murati A, Ginestier C, Charafe-Jauffret E, Ethier SP, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Theillet C, Birnbaum D, Chaffanet M. Reciprocal translocations in breast tumor cell lines: cloning of a t(3;20) that targets the FHIT gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;35:204–218. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jayachandran G, Sazaki J, Nishizaki M, Xu K, Girard L, Minna JD, Roth JA, Ji L. Fragile histidine triad-mediated tumor suppression of lung cancer by targeting multiple components of the Ras/Rho GTPase molecular switch. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10379–10388. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wistuba II, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Molecular genetics of small cell lung carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dumon KR, Ishii H, Vecchione A, Trapasso F, Baldassarre G, Chakrani F, Druck T, Rosato EF, Williams NN, Baffa R, During MJ, Huebner K, Croce CM. Fragile histidine triad expression delays tumor development and induces apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4827–4836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siprashvili Z, Sozzi G, Barnes LD, McCue P, Robinson AK, Eryomin V, Sard L, Tagliabue E, Greco A, Fusetti L, Schwartz G, Pierotti MA, Croce CM, Huebner K. Replacement of Fhit in cancer cells suppresses tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13771–13776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu R, Connolly DC, Dunn RL, Cho KR. Restored expression of fragile histidine triad protein and tumorigenicity of cervical carcinoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:338–344. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.4.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otterson GA, Xiao GH, Geradts J, Jin F, Chen WD, Niklinska W, Kaye FJ, Yeung RS. Protein expression and functional analysis of the FHIT gene in human tumor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:426–432. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.6.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werner NS, Siprashvili Z, Fong LY, Marquitan G, Schroder JK, Bardenheuer W, Seeber S, Huebner K, Schutte J, Opalka B. Differential susceptibility of renal carcinoma cell lines to tumor suppression by exogenous Fhit expression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2780–2785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng WG, Nishizaki M, Fang B, Roth JA, Ji L. Induction of apoptosis by tumor suppressor FHIT via death receptor signaling pathway in human lung cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roz L, Andriani F, Ferreira CG, Giaccone G, Sozzi G. The apoptotic pathway triggered by the Fhit protein in lung cancer cell lines is not affected by Bcl-2 or Bcl-x(L) overexpression. Oncogene. 2004;23:9102–9110. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]