Background: The four PLC-β subtypes (β1–β4) have different roles in GPCR-mediated signaling despite having similar structures and regulatory modes.

Results: PDZK1 mediates the physical coupling of PLC-β3 to SSTRs using different PDZ domains.

Conclusion: PLC-β3 is specifically involved in SSTR-mediated signaling via its interaction with PDZK1.

Significance: The subtype-specific role of PLC-β is mediated by differential interactions with PDZ proteins and GPCRs.

Keywords: Bioinformatics, Calcium Signaling, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Phospholipase C, Scaffold Proteins, PDZ Protein, PDZK1, Somatostatin

Abstract

Phospholipase C-β (PLC-β) is a key molecule in G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)-mediated signaling. Many studies have shown that the four PLC-β subtypes have different physiological functions despite their similar structures. Because the PLC-β subtypes possess different PDZ-binding motifs, they have the potential to interact with different PDZ proteins. In this study, we identified PDZ domain-containing 1 (PDZK1) as a PDZ protein that specifically interacts with PLC-β3. To elucidate the functional roles of PDZK1, we next screened for potential interacting proteins of PDZK1 and identified the somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) as another protein that interacts with PDZK1. Through these interactions, PDZK1 assembles as a ternary complex with PLC-β3 and SSTRs. Interestingly, the expression of PDZK1 and PLC-β3, but not PLC-β1, markedly potentiated SST-induced PLC activation. However, disruption of the ternary complex inhibited SST-induced PLC activation, which suggests that PDZK1-mediated complex formation is required for the specific activation of PLC-β3 by SST. Consistent with this observation, the knockdown of PDZK1 or PLC-β3, but not that of PLC-β1, significantly inhibited SST-induced intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, which further attenuated subsequent ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Taken together, our results strongly suggest that the formation of a complex between SSTRs, PDZK1, and PLC-β3 is essential for the specific activation of PLC-β3 and the subsequent physiologic responses by SST.

Introduction

Phospholipase C (PLC)2 is an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphates from phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphates, which are implicated in PKC activation and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, respectively (1). As one of six mammalian PLC isotypes (β, γ, δ, ϵ, ζ, and η), PLC-β plays pivotal roles in G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)-mediated signaling. When stimulated, the GTP-bound Gαq subunit interacts with and activates PLC-β. The specific activation of PLC-β2 and -β3 by the Gi/o class βγ subunits has also been characterized (2).

Although all of the PLC-β subtypes (β1–β4) possess the same structure and mode of regulation, their tissue distribution patterns are somewhat different (3). Moreover, the differential expression patterns of the PLC-β subtypes are further reflected by the distinct phenotypes of PLC-β subtype knock-out mice (4, 5), suggesting that PLC-β has subtype-specific roles. Similarly, several GPCRs transmit activation signals to PLC-β in a subtype-specific manner. For example, PLC-β1 is involved in muscarinic acetylcholine receptor signaling, whereas PLC-β4 functions primarily via the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) (6). Specific activation of PLC-β3 by P2Y2 purinergic receptor stimulation has also been reported (7). Thus, it is quite clear that each PLC-β subtype participates in a different GPCR-mediated signaling and serves a different function. However, the underlying molecular mechanism remains to be completely understood. At their C termini, PLC-β subtypes have a short consensus motif known as the postsynaptic dentisty-95/discs larges/ZO-1 (PDZ)-binding motif. The PDZ-binding motif is a well known short linear motif that interacts with the PDZ protein (8). Notably, each PLC-β subtype has a distinct PDZ-binding motif, implying differential interaction with PDZ proteins. Therefore, the organization of each PLC-β subtype into a unique complex mediated by a different PDZ protein would lead to specific roles for each PLC-β subtype.

PDZ domain-containing 1 (PDZK1), also known as NHERF3 and CLAMP, is a typical PDZ protein because it possesses four tandem PDZ domains without any enzymatic activity. So, PDZK1 primarily acts as an adaptor in the formation of diverse molecular complexes with its PDZ domains. For example, PDZK1 is known to interact with scavenger receptor class B (9). Through this interaction, PDZK1 regulates the expression and membrane localization of scavenger receptor class B, thereby affecting plasma cholesterol levels (10). Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is another interacting protein of PDZK1, and upon interaction, PDZK1 facilitates CFTR-CFTR dimerization and potentiates chloride channel activity (11). These studies demonstrate that PDZK1 not only regulates the stability and localization of target proteins, but also affects the subsequent physiologic responses via its specific interactions. Thus, the identification of novel PDZK1-interacting proteins is an interesting issue in terms of physiological signaling. In this regard, GPCRs may be interesting candidates because they are already known to interact with several PDZ proteins, such as PDS-95 (5-HT) (12) and Shank (mGluR) (13). In addition, GPCR-PDZ protein interactions are thought to be significant for downstream signal transduction events including PLC-β activation (14). Therefore, we hypothesized that PDZK1 interacts with various signaling proteins, such as certain GPCRs and PLC-β subtypes, and then regulates downstream signal transduction events upon stimulation of these GPCRs.

Several studies have previously analyzed the interactions between the PDZ domain and the PDZ-binding motif with reasonable accuracy using large scale methods, such as peptide arrays, phage display, and data integrative analysis (15, 16). Thus, these methods may be useful to search for the potential proteins that might interact with PDZK1. In the present study, we first identified PDZK1 as a PDZ protein that interacts with PLC-β3. To elucidate the functional meaning of the interaction between PDZK1 and PLC-β3, we screened for potential interacting proteins of PDZK1 and identified the somatostatin receptors (SSTRs), which thereby assembled as a ternary complex with PDZK1 and PLC-β3. In addition, we showed that formation of this complex was not only essential for the specific activation of PLC-β3, but was also required for subsequent Ca2+ signaling and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in response to somatostatin (SST).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

SST was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA). Fura-2/AM was obtained from Invitrogen. U73122 and pertussis toxin (PTX) were obtained from Calbiochem. Mouse monoclonal HA antibody was generated. Mouse monoclonal antibody against PDZK1 was generously provided by Dr. H. Arai from Tokyo University, Japan. Mouse monoclonal FLAG antibody and FLAG M2-agarose were purchased from Sigma. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against PLC-β1 and -β3 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phospho-ERK1/2 and mouse monoclonal antibody to actin were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA) and ICN Biomedicals (Aurora, OH), respectively. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mouse IgA, IgM, and IgG were obtained from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories (Gaithersburg, MD).

Cell Culture and Transfection

The HEK293 human embryonic kidney cell line was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (BioWhittaker), 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The MCF7 human breast cancer cell line was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For transient transfection, Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) reagent was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmid Constructions and RNA Interference (RNAi)

FLAG-tagged PLC-β and various PLC isotypes in pCMV2 (Sigma) were constructed from the previously isolated cDNA. C-terminal PDZ-binding motif-deleted PLC-β3 and point mutants of the individual residues to Ala in the PDZ-binding motif (NTQL) were generated, as described previously (17). HA-tagged PDZK1 was constructed from the PDZK1 cDNA provided by Dr. H. Arai (Tokyo University, Japan). To express each PDZ domain of PDZK1 in Escherichia coli, the cDNA was used as a template for PCR. The PCR products were digested and inserted into pGEX4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences). HA-tagged NHERF1 and NHERF2 constructs were generated, as described previously (18). FLAG-tagged SSTR5 and its PDZ-binding motif-deleted mutant (SSTR5ΔC) were constructed from pcDNA3.1/SSTR5 generously provided by Dr. H. J. Kreienkamp (Universitätskrankenhaus Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany) (19). FLAG-tagged SSTR isotypes (SSTR1–4) were generated from a total cDNA library of Neuro2A and Min6 cells using PCR. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. For knockdown experiments, small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes against PDZK1 (nucleotides 890–908) and scrambled siRNA duplexes were synthesized by Genolution (Korea). Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against PLC-β1, -β3, and control shRNA were purchased from Sigma.

GST Pulldown Assay

Pulldown assays were performed using recombinant proteins fused to GST. GST fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 by induction with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 4 h at 27 °C. Bacterial lysates were sonicated, and each protein was purified from soluble fractions on glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences). Equal amounts of the HEK293 cell lysates were incubated with Sepharose-bound GST fusion proteins for 4 h at 4 °C. Following incubation, beads were washed three times with a lysis buffer (40 mm HEPES, 1 mm EDTA, 120 mm NaCl, 1 mm PMSF, 1.5 mm Na3VO4, 50 mm NaF, 10 mm β-glycerol phosphate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.4) The bound proteins were eluted with 1× SDS sample buffer supplemented with 50 mm DTT and 30 mm EDTA, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blotting.

Western Blot Analysis and Immunoprecipitation

Cells treated with the conditions indicated were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed with lysis buffer. The lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. For Western blot analysis, the supernatant fractions containing equal amounts of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. A secondary antibody liked to horseradish peroxidase was used at a dilution of 1:5,000. Specific signals were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). For immunoprecipitation, supernatant fractions containing equal amounts of protein were incubated with the appropriate antibodies immobilized onto protein A-Sepharose or α-FLAG M2-agarose for 4 h at 4 °C. The immunocomplexes were collected by centrifugation and then washed three times with lysis buffer. The resulting precipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

Screening of Potential PDZK1 Target Proteins

We used a machine learning algorithm to construct a computational model of ligand selectivity of PDZ domains from experimental data of PDZ domain-peptide interactions. Three types of interaction data were used, including protein arrays of 81 mouse PDZ domains against 217 synthesized peptides (15), collections of individual PDZ domain-ligand interactions (20–22), and high throughput binding assays using phage display (23). From these experimental data, a computational model was built by using a machine learning algorithm, Fisher's linear discriminant analysis, to describe the relationship between pocket residues of PDZ domains and the bound peptides. To extract pocket residues of PDZ domains, a multiple sequence alignment of PDZ domains was generated, using a Hidden Marcov Model for the PDZ domain. To position pocket residues within the PDZ domain sequence, a multiple sequence alignment was used, and the known pocket residue positions of the first PDZ domain from PSD-95 were referenced. The multiple sequence alignment was constructed by using HMMer (24) and a Hidden Marcov Model that is optimized for the PDZ domain from Pfam (25). Subsequently, pocket residues were identified according to pocket definitions described by Wiedemann et al. (26). Pocket residues of PDZ domains were analyzed by using 10 physicochemical properties of amino acids that describe the number of hydrogen bond donors (27), polarity (28), volume (28), bulkiness (29), hydrophobicity (29, 30), isoelectric point (29), positive charge (27), negative charge (27), electron ion interaction potential (31), and free energy in water (32).

To quantify binding potential between PDZ domains and ligands, we adopted an information theory-based positional weight matrix (PWM) method that has been widely used to predict protein-DNA bindings (33–38). Amino acid frequencies were calculated at each ligand position from the four sets of predicted target amino acids, and these frequencies were divided by the background frequency that was expected to be observed in C-terminal residues of the ligands,

|

where PWM(a,i) is the affinity contribution of amino acid a at the ith position, fa,i is the frequency of amino acid a at the ith position in the collected set, and pa,i is the background frequency, defined as the probability of observing amino acid a at the ith position in any ligand protein.

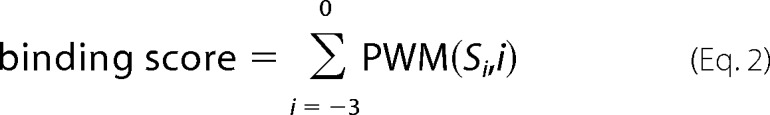

A PWM was used to calculate the binding score of a potential interaction partner with a given sequence by summing the corresponding amino acids for the binding potential of each position. The binding score of each peptide was calculated according to the following equation,

|

where PWM(Si,i) is the binding potential of the amino acid Si at the ith position in the matrix and Si is the amino acid at the ith position of the peptide.

By using this computation selectivity model, the PWMs for the PDZ domains of PDZK1 were generated. The PWMs were used to calculate binding scores between candidate proteins and each PDZ domain of PDZK1. Based on these binding scores, the candidate proteins were prioritized.

To determine C-terminal flexibility of candidate proteins, disorder propensity of each residue in candidate proteins was predicted by the DISOPRED2 program, an algorithm that has been shown to provide a reliable prediction of disordered regions. DISOPRED2 was run for each protein in the human proteome. We used the probability score, which is based on the likelihood of the residue being in a disordered region and the conservation of the disorderedness of the residue among homologous sequences set. C-terminal flexibility of the protein was defined as a fraction of disordered residues within 50 C-terminal residues. The calculation of the C-terminal flexibility of human proteins was performed by a custom script.

Measurement of Total Inositol Phosphates

To measure PLC activity, HEK293 cells were plated at 1 × 106 cells/well in a 6-well plate. The cells were then transfected as indicated. After 24 h, these cells were incubated with 1 μCi of [3H]inositol (NEN Life Science Products) per well in 1 ml of inositol and serum-free DMEM for 18 h at 37 °C. Following incubation with 10 mm LiCl for 10 min, the cells were treated with SST for 30 min and then lysed by adding ice-cold 5% perchloric acid. The accumulated [3H]inositol phosphates were measured as described previously (39).

Measurement of Intracellular Ca2+ Mobilization

Intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in HEK293 cells stably expressing SSTR5 or its PDZ-binding motif deletion mutant (SSTR5ΔC) was measured using Fura-2/AM. Briefly, HEK293 cells were incubated with 1 μm Fura-2/AM for 20 min at 37 °C. After washing twice, the cells were incubated with Locke's solution (158.4 mm NaCl, 5.6 mm KCl, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 2.2 mm CaCl2, 5 mm HEPES, and 10 mm glucose, pH 7.4) and then stimulated with 5 μm SST. Intracellular Ca2+-dependent changes in fluorescence were imaged using an IX81 ZDC microscope in UNIST-Olympus Biomed Imaging Centor (UOBC). Fluorescence changes from 15 to 20 cells were recorded at an emission wavelength of 510 nm for dual excitation wavelength at 340 nm (Fura-2-Ca2+ complex) and 380 nm (free Fura-2). Cell images were produced at a rate of one image/3 s. The changes in the ratio of the Fura-2-Ca2+ complex to free Fura-2 were normalized by intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) as described (40). The dissociation constant Kd of the Fura-2-Ca2+ complex was assumed to be 225 nm (40).

Statistical Analysis

Student's t test was used to calculate p values based on comparisons with the appropriate control samples tested at the same time. p values < 0.05 and < 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Identification of PDZK1 as a PLC-β3-interacting PDZ Protein

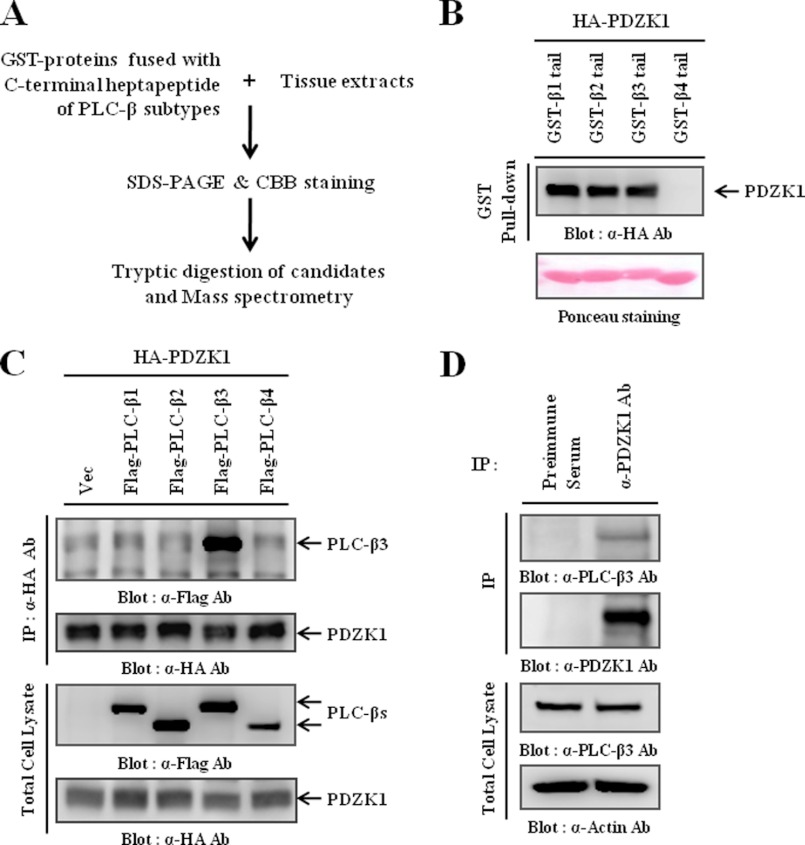

Initially, we used C-terminal heptapeptides of PLC-β (GST-β-tail) in a GST pulldown assay to identify PLC-β-interacting PDZ proteins. The proteins specifically interacting with the heptapeptides were resolved with SDS-PAGE, followed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 1A). As a possible candidate, we found that PDZK1 is a PLC-β-interacting PDZ protein. As shown in Fig. 1B, the C-terminal heptapeptides of the PLC-β subtypes, with the exception of PLC-β4, interacted with PDZK1. To confirm whether PLC-β full-length proteins also interacted with PDZK1, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with HA-PDZK1 and one of the FLAG-PLC-β subtypes, and the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using the HA antibody. Surprisingly, in contrast to the pulldown results, only PLC-β3 full-length protein interacted with PDZK1 (Fig. 1C). Previous studies have shown that additional regions of the target protein, along with the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif, were required for the selective recognition of PDZ proteins (41). Therefore, the differences of our results may suggest that a molecular requirement for the specific interaction of PDZK1 exists within PLC-β3 in addition to the PDZ-binding motif. Next, we examined endogenous interactions using the PDZK1 antibody and found that an interaction between PLC-β3 and PDZK1 also occurred at the endogenous level (Fig. 1D). Previous studies have shown that PDZK1 was primarily expressed in the kidney and that its expression increased in some breast cancer cells (11, 42). So, to further validate the interaction between PLC-β3 and PDZK1 in more physiologically relevant systems, we utilized kidney tissue and MCF7 breast cancer cells, observing similar results (supplemental Fig. 1, A and B). Therefore, these results collectively demonstrate that PDZK1 specifically interacts with PLC-β3 in vivo.

FIGURE 1.

PDZK1 specifically interacts with PLC-β3. A, strategies for identifying PLC-β-interacting PDZ proteins are shown. B, lysates of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with HA-PDZK1 were precipitated with GST fusion proteins containing the C-terminal heptapeptide of each PLC-β subtype (GST-β-tail). The precipitates were then subjected to Western blotting to determine whether the PDZ-binding motif of PLC-β interacts with PDZK1. C, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with HA-PDZK1 and one of the PLC-β subtypes. PDZK1 was immunoprecipitated using the HA antibody, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blotting to detect the co-immunoprecipitated PLC-β subtypes. D, HEK293 cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using the PDZK1 antibody, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blotting to confirm the endogenous interaction between PDZK1 and PLC-β3.

PDZ-binding motif of PLC-β3 and First PDZ Domain of PDZK1 Are Essential for Interaction

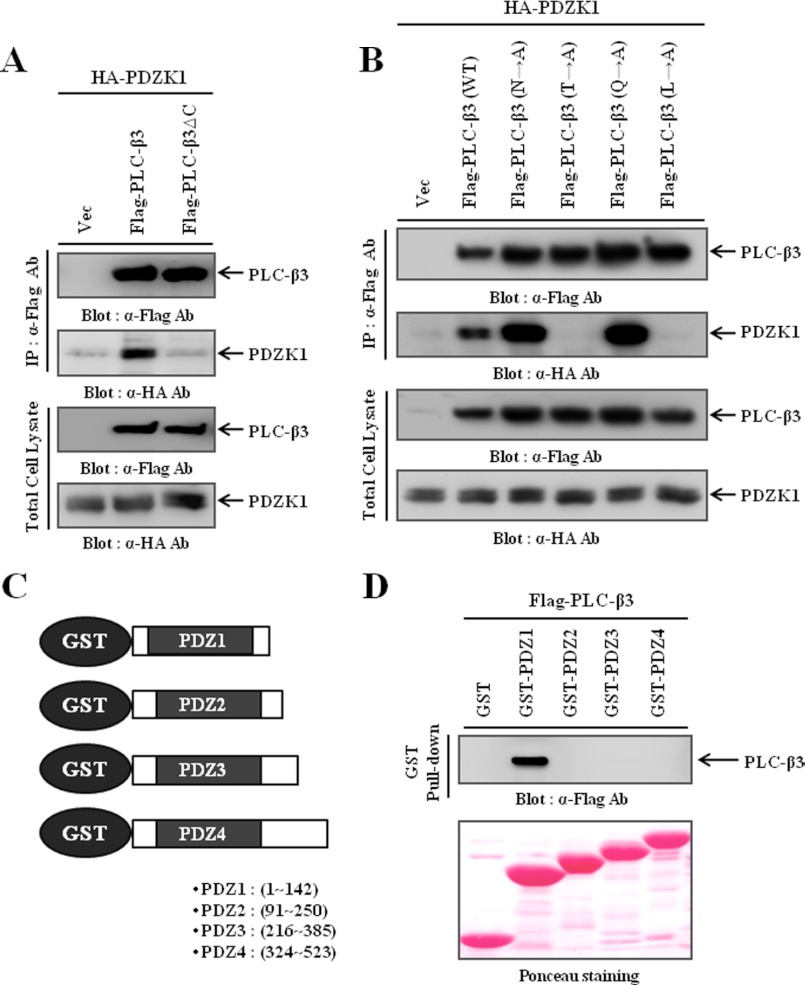

To characterize the interaction between PLC-β3 and PDZK1, we first assessed the significance of the PDZ-binding motif. As shown in Fig. 2A, we found that deleting the PDZ-binding motif from PLC-β3 (PLC-β3ΔC) abrogated the PDZK1 interaction, which suggests that the PDZ-binding motif of PLC-β3 is essential for PDZK1 interaction. Because the −2 and 0 positions of the PDZ-binding motif were critical for the PDZ domain interaction (43), we then examined the binding preference of PDZK1 by mutating each amino acid of the PDZ-binding motif to Ala. Interestingly, mutation of Thr or Leu at the −2 or 0 position to Ala completely abolished interaction, whereas mutations of the other residues had no effect and even potentiated interaction (Fig. 2B). Thus, these results indicate that the Thr and Leu residues of the PDZ-binding motif are critical for the interaction of PLC-β3 with PDZK1. Subsequently, we determined which PDZ domains of PDZK1 were responsible for the interaction with PLC-β3. For this purpose, we generated GST proteins fused to each PDZ domain of PDZK1 (Fig. 2C) and performed pulldown assays. Our results clearly demonstrated that the N-terminal first PDZ domain of PDZK1 specifically interacted with PLC-β3 (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of the interaction between PLC-β3 and PDZK1. A, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with HA-PDZK1 and either wild-type PLC-β3 or its PDZ-binding motif deletion mutant (PLC-β3ΔC). PLC-β3s were immunoprecipitated (IP) using the FLAG antibody, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blotting to detect the co-immunoprecipitated PDZK1. B, each residue of the PDZ-binding motif from PLC-β3 was mutated to Ala. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with HA-PDZK1 and either wild-type PLC-β3 or one of the point mutants. PLC-β3s were immunoprecipitated using the FLAG antibody, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blotting to detect the co-immunoprecipitated PDZK1. C, schematic diagrams GST-fusion proteins containing each PDZ domain of PDZK1. The region of each PDZ domain is indicated. D, lysates of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with FLAG-PLC-β3 were precipitated with various GST fusion proteins containing each PDZ domain of PDZK1, and the precipitates were subjected to Western blotting to determine which PDZ domain interacts with PLC-β3.

Data Integrative Analysis Suggests SSTRs as Potential Targets of PDZK1

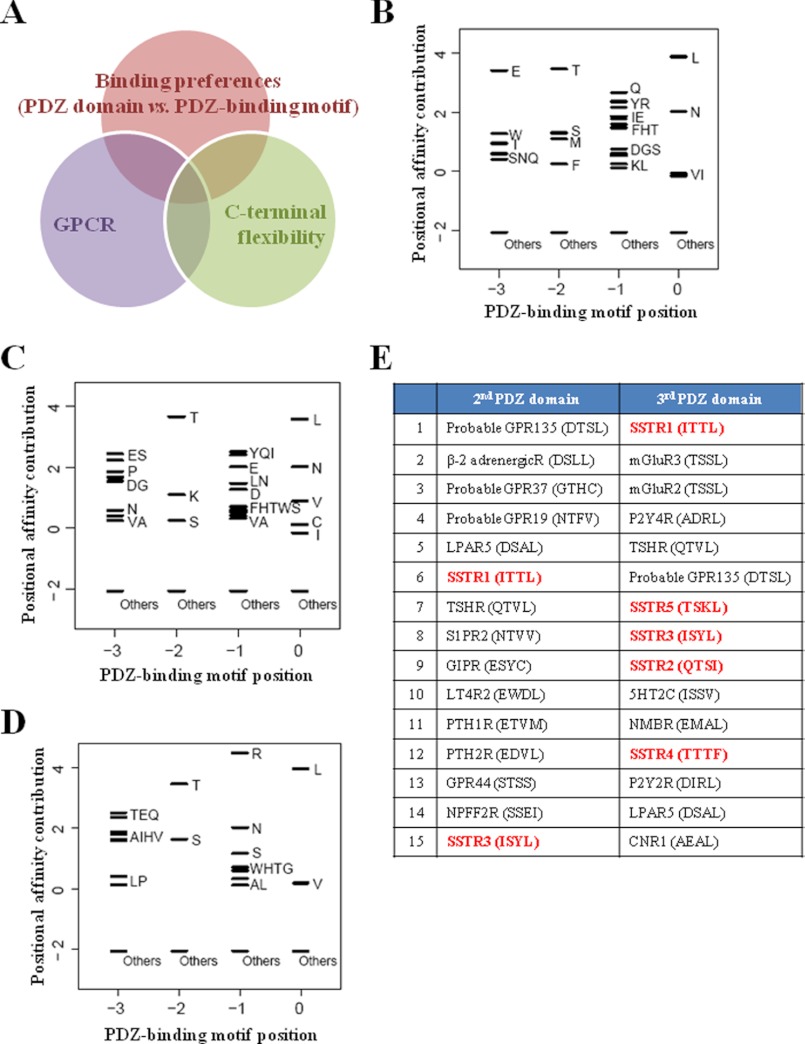

Next, we sought to elucidate the functional meaning of the interaction between PLC-β3 and PDZK1. As suggested by our results, PDZK1 retained empty PDZ domains except for the one that interacts with PLC-β3. Therefore, the identification of additional interacting proteins for PDZK1 might aid further investigation. Initially, we performed a data integrative analysis to screen potential PDZK1-interacting proteins using three parameters (Fig. 3A). The first parameter was the binding preference between the PDZ domain and the PDZ-binding motif. We developed a computational model of PDZ domain binding specificity that was based on various experimental data (44) (for a detailed explanation, see “Experimental Procedures”). This computational model exploited the similarity of the binding pockets of the PDZ domains and the amino acid information of their known interacting proteins and generated PWMs to depict the binding potentials of the amino acids for PDZ domains of interest. Accordingly, by analyzing the amino acids of the binding pockets from the PDZ domains of PDZK1, a potential PDZ-binding motif for each PDZ domain of PDZK1 was generated (Fig. 3, B–D), with the exception of the fourth PDZ domain because of the lack of a dataset. This information was then systematically compared with the C-terminal sequences of ∼20,000 human proteins obtained from UniProt to calculate a binding score for each protein. Subsequently, we considered GPCRs as the second parameter because PLC-β3 is a well known downstream effector of GPCRs, and many PDZ proteins are already known to interact with GPCRs (12, 18, 45). This process allowed us to prioritize the GPCRs according to their binding scores (data not shown). The last parameter exploited was C-terminal flexibility. Short linear motifs that are recognized by peptide-binding domains, such as the SH2, SH3, and PDZ domains, have been shown to be located within intrinsically flexible or disordered regions of the protein rather than structured regions (46–49). Because this location could provide the orientational freedom required for searching and interacting with target proteins, the existence of a flexible region immediately adjacent to a short linear motif has been recently regarded as an important determinant for domain interaction (48, 49). Several studies have shown that this parameter was helpful when searching and characterizing the target proteins of the SH2 and PDZ domains (50). Thus, we measured the C-terminal flexibility of GPCRs using DISOPRED2 to further eliminate candidates. In this manner, we generated a list of potential GPCRs list for the interactions with PDZK1 (Fig. 3E). Of all of the possible candidates, we were most interested in SSTRs because all SSTR isotypes have high binding potentials. Most importantly, SSTRs are known to induce PLC-β/Ca2+ signaling upon stimulation. Therefore, we finally selected SSTRs as the most feasible targets and decided to investigate their roles in the molecular complex mediated by PDZK1.

FIGURE 3.

Data integrative analysis for screening potential PDZK1-interacting GPCRs. A, three parameters utilized in screening potential PDZK1-interacting proteins. B–D, PWM of the first (B), second (C), and third (D) PDZ domains of PDZK1. The black bars represent the affinity contribution of the binding scores to corresponding amino acids. Clusters of amino acids with no preference are labeled “Others.” E, high ranking GPCR candidates for the interaction with the second or third domains of PDZK1. The PDZ-binding motifs of the GPCRs are shown, and all SSTRs are highlighted with red.

PDZK1 Assembles as Ternary Complex with PLC-β3 and SSTRs

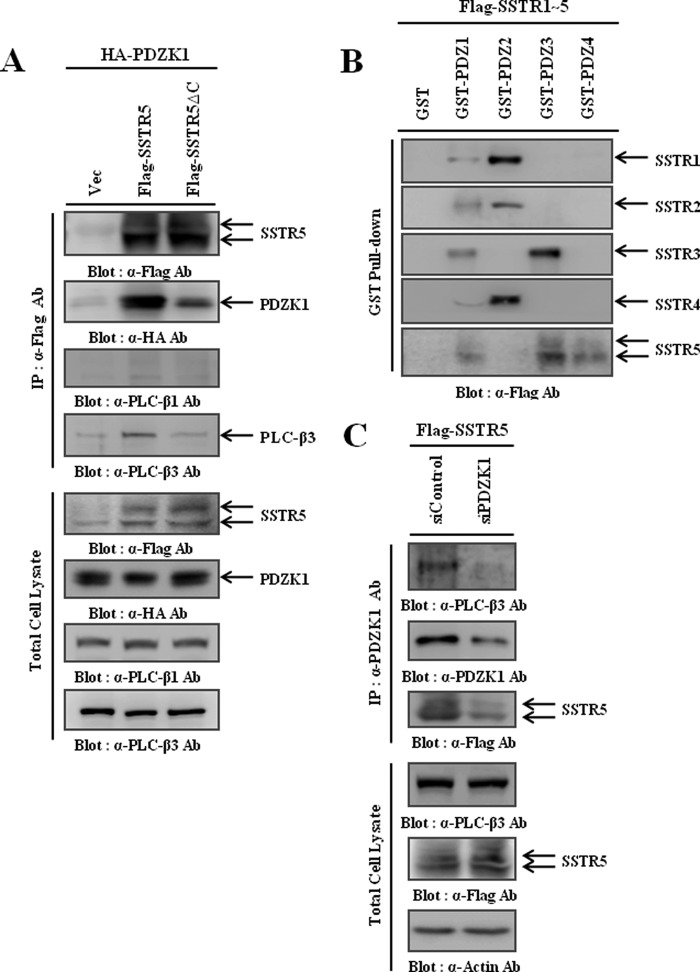

Because SSTRs were the most feasible PDZK1 targets, we sought to validate the interaction between PDZK1 and SSTRs. Of the five isotypes, interaction of SSTR5 with PDZK1 had already been examined (19). So, we first examined whether PDZK1 assembled as a molecular complex with SSTR5 and PLC-β3. For this purpose, HA-PDZK1 was co-transfected with FLAG-SSTR5 into HEK293 cells, and the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using the FLAG antibody. Surprisingly, SSTR5 not only interacted with PDZK1 but also interacted with endogenous PLC-β3, but not with PLC-β1. However, this was not the case when the PDZ-binding motif of SSTR5 was deleted (SSTR5ΔC) (Fig. 4A), which emphasizes the essential role of the PDZ-binding motif of SSTR5 in the formation of the molecular complex. We also confirmed that other SSTR isotypes (SSTR1–4) interact with PDZK1 and form complexes with PLC-β3, which validates the accuracy of our data integrative analysis (data not shown). To characterize the interactions of the SSTRs, GST pulldown assays were performed using GST fusion proteins (Fig. 2C). As shown in Fig. 4B, whereas the second PDZ domain interacted primarily with SSTR1, 2, and 4, the third PDZ domain interacted primarily with SSTR3 and 5. Because the PLC-β3 interaction was occurring through the first PDZ domain of PDZK1 (Fig. 2D), these results collectively suggest that PDZK1 utilizes different PDZ domains to form a ternary complex with PLC-β3 and SSTRs. To further confirm the essential role of PDZK1 in this ternary complex formation, we used PDZK1 siRNA (siPDZK1) and found that knockdown of PDZK1 disrupted the ternary complex formation (Fig. 4C). Therefore, these results clearly demonstrate that PDZK1 mediates the physical coupling of PLC-β3 to SSTRs using its different PDZ domains.

FIGURE 4.

PDZK1 assembles as a ternary complex with PLC-β3 and SSTRs. A, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with HA-PDZK1 and either wild-type SSTR5 or its PDZ-binding motif deletion mutant (SSTR5ΔC). SSTR5s were immunoprecipitated (IP) using the FLAG antibody, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blotting to detect the co-immunoprecipitated PDZK1 and endogenous PLC-β3. B, lysates of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with one of the SSTR isotypes were precipitated with various GST fusion proteins containing each PDZ domain of PDZK1, and the precipitates were subjected to Western blotting to determine which PDZ domain of PDZK1 interacts with SSTR5. C, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-SSTR5 and either scramble (siControl) or PDZK1 siRNA (siPDZK1). PDZK1 was immunoprecipitated using the PDZK1 antibody, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blotting to determine the efficiency of the PDZK1 knockdown and the formation of the ternary complex.

PDZK1-mediated Complex Formation Is Essential for SST-induced PLC-β3 Activation

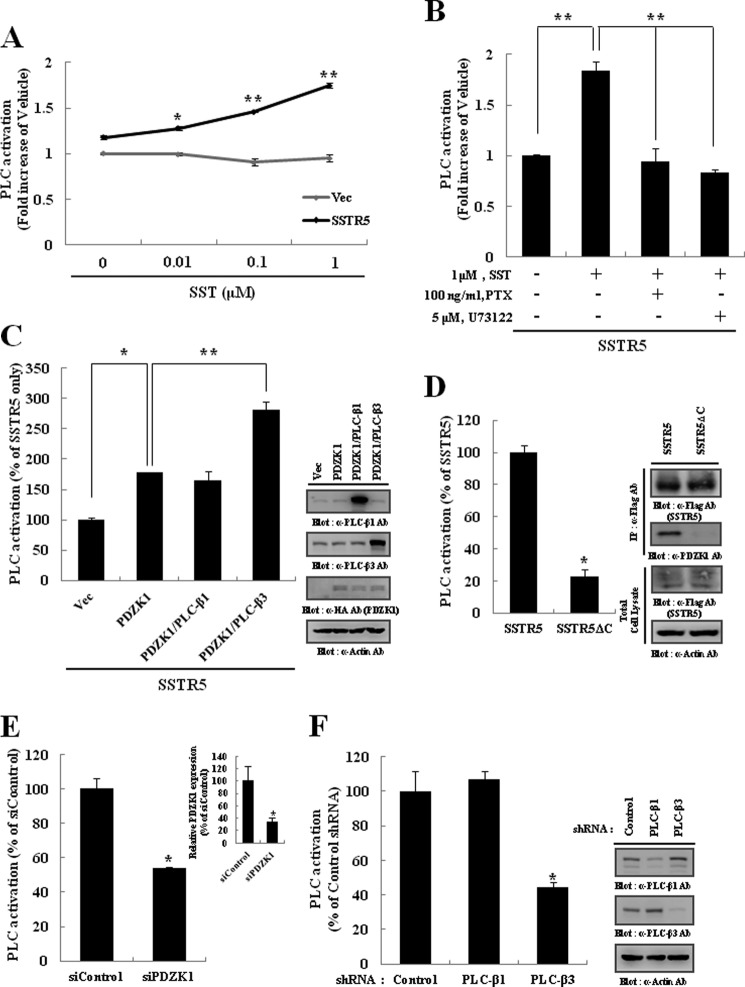

Previously, we reported that PLC-β subtypes participated in different GPCR-mediated signaling via their interaction with different PDZ proteins (51, 52). Thus, the molecular complex mediated by PDZK1 might be essential for SST-induced signaling in which PLC-β3 was specifically involved. To examine this possibility, we measured PLC activity after SST treatment. As shown in Fig. 5A, SST increased the PLC activity in HEK293 cells expressing SSTR5 in a dose-dependent manner. However, this activation was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with PTX or U73122, a PLC inhibitor (Fig. 5B), indicating that SST-induced PLC activation is mediated by the Gαi/o pathway. Based on these results, we next assessed the possible roles of PDZK1 and PLC-β3 in SST-induced PLC activation. As shown in Fig. 5C, SST-induced PLC activation was increased significantly with the expression of PDZK1, which was further potentiated by the co-expression of PLC-β3. However, the expression of PLC-β1 had little effect. These results indicate the essential roles of complex components in SST-induced PLC activation. Regarding the significance of complex formation, we found that by deleting the PDZ-binding motif of SSTR5 (SSTR5ΔC) or PDZK1 knockdown (siPDZK1), either of which sufficiently disrupts the ternary complex (Fig. 4, A and C), the SST-induced PLC activation was significantly attenuated (Fig. 5, D and E). Because only PLC-β3 was physically coupled to the SSTRs via PDZK1 interaction (Fig. 4C), PLC-β3 might participate primarily in SST-induced PLC activation. As expected, the knockdown of PLC-β3, but not PLC-β1, significantly inhibited the SST-induced PLC activation (Fig. 5F). Altogether, these results clearly demonstrate that PDZK1-mediated complex formation is required for the specific activation of PLC-β3 upon SST stimulation.

FIGURE 5.

PDZK1-mediated ternary complex is essential for specific activation of PLC-β3 by SST. A, HEK293 cells transiently transfected with vector (Vec) or FLAG-SSTR5 were labeled with 1 μCi/ml [3H]inositol in inositol- and serum-free medium for 18 h and subsequently stimulated with the indicated concentration of SST for 30 min. The reactions were quenched, and the production of total [3H]inositol phosphates was measured. B, PTX and U73122 were pretreated for 16 h and 30 min, respectively, prior to SST stimulation. C, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected as indicated. The cells were incubated with 1 μm SST for 30 min, and then the production of total [3H]inositol phosphates was measured. The expression levels of PLC-β1, PLC-β3, and PDZK1 were determined by Western blotting. D, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with either wild-type SSTR5 or its PDZ-binding motif deletion mutant (SSTR5ΔC). The cells were incubated with 1 μm SST for 30 min, and then the production of total [3H]inositol phosphates was measured. The expression levels of SSTR5 and SSTR5ΔC and their abilities to interact with PDZK1 were determined by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. E and F, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with SSTR5 and either PDZK1 siRNA (siPDZK1) (E) or PLC-β shRNA (F). The cells were stimulated with 1 μm SST, and then the production of total [3H]inositol phosphates was measured. The specific knockdown of PDZK1 or the PLC-β subtypes was determined by quantitative PCR or Western blotting, respectively. The data represent the means ± S.D. (error bars) (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

PDZK1-mediated Complex Formation Is Required for SST-induced Ca2+ Signaling

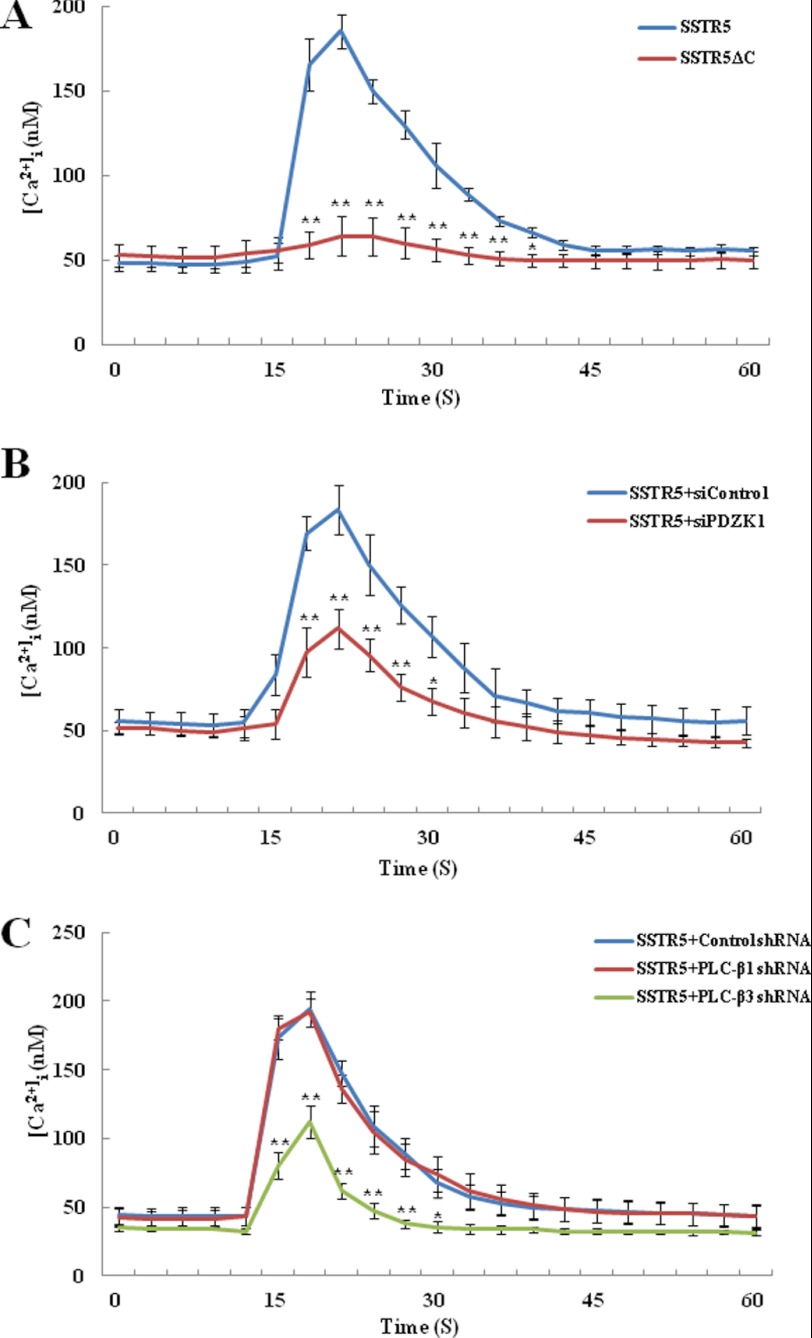

According to our results, the ternary complex formation that is mediated by PDZK1 was required for the specific activation of PLC-β3 by SST. To further confirm the role of the PDZK1-mediated ternary complex formation, we next measured the intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, a well known PLC downstream event (3, 53). For this purpose, we first generated HEK293 cells that stably express SSTR5 or its PDZ-binding motif deletion mutant (SSTR5ΔC). As shown in Fig. 6A, we found that SST increased the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in HEK293 cells stably expressing SSTR5. However, this was not the case when SSTR5ΔC was expressed, which emphasizes the essential role of the PDZ-binding motif of SSTR5 in SST-induced Ca2+ signaling. To assess the role of PDZK1 in this Ca2+ signaling, we next used PDZK1 siRNA (siPDZK1) and found that the knockdown of PDZK1 significantly inhibited the elevation of [Ca2+]i upon SST stimulation (Fig. 6B). Because PLC-β3 was specifically involved in the SST-induced PLC activation (Fig. 5F), we subsequently examined the essential role of PLC-β3 in SST-induced Ca2+ signaling. As shown in Fig. 6C, knockdown of PLC-β3 significantly attenuated the elevation of [Ca2+]i by SST. However, PLC-β1 knockdown had little effect (Fig. 6C). Thus, these results consistently demonstrate that the ternary complex between SSTRs, PDZK1, and PLC-β3 leads to a specific role for PLC-β3 in SST-induced PLC/Ca2+ signaling.

FIGURE 6.

PDZK1-mediated ternary complex is required for PLC-β3-dependent Ca2+ signaling. A, HEK293 cells that stably express SSTR5 or its PDZ-binding motif deletion mutant (SSTR5ΔC) were loaded with Fura-2/AM and subsequently stimulated with 5 μm SST. B, HEK293 cells that stably express SSTR5 were transiently transfected with scrambled (siControl) or PDZK1 siRNA (siPDZK1). The cells were loaded with Fura-2/AM and then stimulated with 5 μm SST. C, HEK293 cells that stably express SSTR5 were transiently transfected with the control, PLC-β1, or PLC-β3 shRNA. The cells were loaded with Fura-2/AM and then stimulated with 5 μm SST. The changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) were monitored. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments, and the data represent the means ± S.D. (error bars) (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

PDZK1 and PLC-β3 Are Required for ERK1/2 Phosphorylation by SST

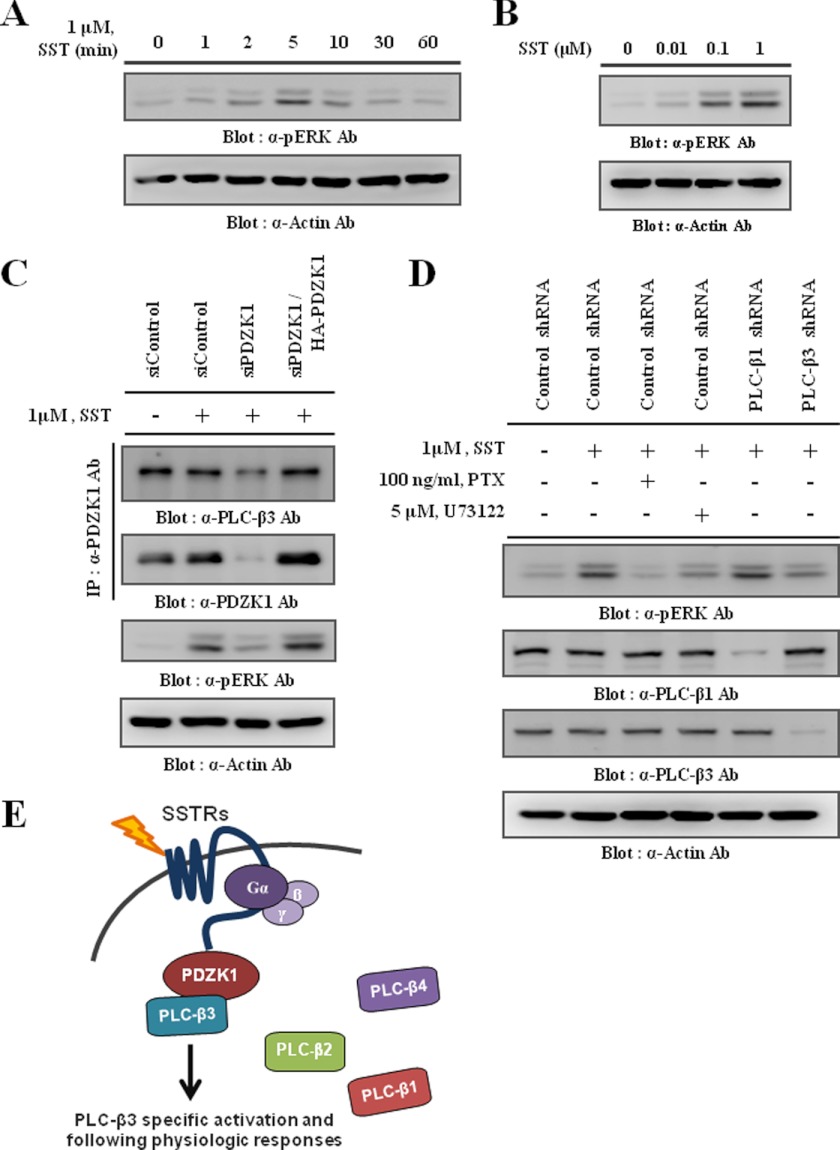

The activation of PLC-β is well known to affect the activation of downstream MAPKs, such as ERK1/2, during GPCR-mediated signaling (18, 39). Therefore, we examined whether SST also activated ERK1/2. As shown in Fig. 7, A and B, SST induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a time- and dose-dependent manner, respectively. Because the SST-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was markedly attenuated by PTX)and by U73122, a PLC inhibitor (Fig. 7D), these results indicate that SST-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation is primarily regulated by the Gαi/o/PLC pathway. Interestingly, our results suggest that PDZK1-mediated complex formation is essential for SST-induced PLC-β3/Ca2+ signaling (Figs. 5 and 6). Thus, disruption of this complex might negatively affect downstream ERK1/2 activation. As expected, the knockdown of PDZK1 abolished the PLC-β3 interaction and consequently, ERK1/2 phosphorylation by SST. However, these effects were dramatically restored by the reexpression of PDZK1 (Fig. 7C). Consistent with these results, knockdown of PLC-β3, but not PLC-β1, specifically inhibited SST-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 7D), suggesting a specific role for PLC-β3 in SST-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that the ternary complex formation mediated by PDZK1 is not only required for PLC-β3/Ca2+ signaling, but that it is also significant for the downstream ERK1/2 activation during SST stimulation.

FIGURE 7.

PDZK1 and PLC-β3 are required for SST-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A and B, following serum starvation for 18 h, HEK293 cells were stimulated with 1 μm SST for the indicated time periods (A) or with the indicated concentration of SST for 5 min (B). The cell lysates were prepared and then subjected to Western blotting to determine the level of phosphorylated ERK1/2. C, HEK293 cells transiently transfected with scrambled (siControl) or PDZK1 siRNA (siPDZK1) with or without HA-PDZK1 were stimulated with 1 μm SST for 5 min. Endogenous PDZK1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) using the PDZK1 antibody, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blotting to detect the co-immunoprecipitated endogenous PLC-β3. The level of phosphorylated ERK1/2 was also determined. D, HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the control, PLC-β1, or PLC-β3 shRNA were stimulated with 1 μm SST for 5 min. PTX and U73122 were pretreated for 16 h and 30 min, respectively, prior to SST stimulation. The levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2, PLC-β1, and PLC-β3 were determined. Actin was blotted as a loading control. E, schematic diagram shows specific roles of PLC-β3 in response to SST by PDZK1-mediated ternary complex formation.

DISCUSSION

Because the four PLC-β subtypes possess similar structures and regulatory mechanisms, the purpose of the multiple subtypes existing in our system is still unclear. Thus far, the answer has involved two possible scenarios. Perhaps the multiple PLC-β subtypes function cooperatively and compensate one another in the presence of unusual mutations of certain PLC-β subtypes. In contrast, each PLC-β subtype might have its own purpose. As to this issue, it is interesting to note that each PLC-β subtype has a different PDZ-binding motif. Because the PDZ proteins determine which protein they interact with primarily on the basis of the PDZ-binding motif (8), each PLC-β subtype may interact with different PDZ proteins. Because GPCRs are known to interact with PDZ proteins, each PLC-β subtype might be assembled into a unique complex to which a specific GPCR is coupled. Our previous studies support this idea. We have shown that Shank2 mediated the specific coupling of PLC-β3 to the mGluR, which is essential for mGluR-mediated Ca2+ signaling (13). We have also reported that another complex consisting of the bradykinin receptor, Par-3, and PLC-β1 was required for the specific activation of PLC-β1 in bradykinin-induced signaling (51). In the present study, we show an additional unique complex with PDZK1-mediated physical coupling of PLC-β3 to the SSTRs (Fig. 7E). Therefore, our series of studies strongly suggests that different interactions among GPCRs, PDZ proteins, and PLC-β subtypes are the underlying molecular mechanism by which each PLC-β subtype is differentially involved in the signaling that is mediated by different GPCRs.

Most studies concerning the role of the PDZ protein are actually initiated following the discovery of its interacting protein. For this purpose, biochemical affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry was conventionally performed because of its advantages for uncovering the physiologically relevant protein-protein interactions. In fact, we identified the PDZK1-PLC-β3 interaction using this method (Fig. 1). However, several limitations to this method have become evident. First, the experimental conditions play critical roles in determining the outcome. For example, the target proteins cannot be identified if they are not expressed in the cells that are utilized. In addition, the biochemical analysis tends to produce a binary result in which the proteins are defined as “interact” or “not interact.” Thus, certain target proteins are frequently regarded as noninteracting proteins because of their relatively weak interaction but have physiological significances nevertheless (54). To circumvent these limitations, data integrative analysis represents a useful alternative. Because data integrative analysis is primarily based on a well established data base, it can minimize false-negatives that are caused by experimental conditions or binary analysis. In addition, because every possible interaction is evaluated, large scale protein interactions can be analyzed (55). One drawback to this method is the existence of false-positives, which must be excluded by additional analytical methods (56). Thus, biochemical and data integrative analysis complement each other, and great synergy can therefore be generated. The present study shows a great example of this synergy. By exploiting data integrative analysis as an initial screening step (Fig. 3), we easily identified the interaction between PDZK1 and SSTRs and subsequently elucidated the functional roles of PDZK1 in SSTR-mediated signaling. Moreover, data integrative analysis provides another possibility that PDZK1 interacts with additional GPCRs because one PDZ domain can interact with multiple targets (56). In this regard, one can speculate that GPCRs other than SSTRs are also physically coupled to PLC-β3 via PDZK1 interaction. Interestingly, several high ranking GPCRs, such as the mGluR, P2Y, and lysophosphoatidic acid (LPA) receptor (Fig. 3E), have already been reported to participate in PLC-β3 specific activation (13, 51, 57). Thus, the potential role of PDZK1 in this coincidental observation remains an unanswered question. Altogether, harmonizing the two different analytical methods presents an attractive study strategy for the discovery of novel targets of PDZ proteins, which will give insight into understanding the complex PDZ interaction network and its related signaling pathway efficiently and accurately.

Because of their linkage to the PTX-sensitive G-protein of Gi/o class, SSTRs can affect various signaling pathways, such as adenylate cyclase inhibition, activation of the G-protein gated inwardly rectifying potassium channel (GIRK), and several enzymes including tyrosine phosphatase, and PLC (58, 59). With regard to physiological functions, SSTRs primarily act as pluripotent regulators of biological processes upon SST binding (60). In particular, SSTR is known to modulate cellular proliferation that is caused by tyrosine phosphatase-dependent inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling (61, 62). However, SSTR also induces cellular proliferation under certain conditions because it can evoke PLC/Ca2+ signaling upon stimulation (63–65). These differing responses are probably caused by the cell type-specific contexts in which the prevalent signaling pathways are determined and thus induce different physiologic responses. In this regard, our finding that PDZK1 mediates SST-induced PLC-β3/Ca2+/ERK1/2 signaling (Figs. 5–7) is noteworthy. Whereas SSTRs and PLC-β3 have a relatively ubiquitous expression pattern, the expression of PDZK1 is highly restricted to the epithelial region, such as the kidney, intestine, and some breast cancer cells (10, 42). Thus, the expression of PDZK1 and following molecular complex formation by PDZK1 are possibly key steps for determining the prevalent SST-induced signaling in a given cell. Therefore, a study to examine whether the expression of PDZK1 is directly linked to activation of PLC-β3/Ca2+/ERK1/2 signaling and to determine the physiological responses of a given cell upon SST stimulation will be interesting.

In summary, the present study is the first to demonstrate the novel roles of PDZK1 in the specific coupling of PLC-β3 to SSTR-mediated signaling. Based on these results and those from our previous studies, we propose that PLC-β has subtype-specific roles in diverse GPCR-mediated signaling via differential interactions with PDZ proteins and GPCRs. The question of which combination is actually made under physiological conditions remains unanswered. To date, ∼250 PDZ proteins have been identified, and 10% of GPCRs possess a PDZ-binding motif; therefore, there are thousands of possible combinations. Thus, solving this complicated jigsaw puzzle will provide more insight into the subtype-specific roles of PLC-β. Our approach in which biochemical and data integrative analysis are well harmonized will shed light on future related studies.

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea Grants KRP-2007-341-C00027 and 2011-0000878 funded by the Korean Government, Fusion Pioneer Project PGB013 from the National Research Foundation of Korea, and Korea Health Technology Research and Development Project A084022, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea and the year of 2010 Research Fund of the UNIST (Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology).

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- mGluR

- metabotropic glutamate receptor

- PDZK1

- PDZ domain-containing 1

- PTX

- pertussis toxin

- PWM

- positional weight matrix

- SST

- somatostatin

- SSTR

- SST receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berridge M. J., Irvine R. F. (1989) Inositol phosphates and cell signalling. Nature 341, 197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bristol J. A., Rhee S. G. (1994) Regulation of phospholipase C-β isozymes by G-proteins. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 5, 402–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suh P. G., Park J. I., Manzoli L., Cocco L., Peak J. C., Katan M., Fukami K., Kataoka T., Yun S., Ryu S. H. (2008) Multiple roles of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isozymes. BMB Rep. 41, 415–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lian L., Wang Y., Draznin J., Eslin D., Bennett J. S., Poncz M., Wu D., Abrams C. S. (2005) The relative role of PLCβ and PI3Kγ in platelet activation. Blood 106, 110–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Han S. K., Mancino V., Simon M. I. (2006) Phospholipase Cβ3 mediates the scratching response activated by the histamine H1 receptor on C-fiber nociceptive neurons. Neuron 52, 691–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim D., Jun K. S., Lee S. B., Kang N. G., Min D. S., Kim Y. H., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G., Shin H. S. (1997) Phospholipase C isozymes selectively couple to specific neurotransmitter receptors. Nature 389, 290–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Strassheim D., Williams C. L. (2000) P2Y2 purinergic and M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors activate different phospholipase C-β isoforms that are uniquely susceptible to protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation and inactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39767–39772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kornau H. C., Schenker L. T., Kennedy M. B., Seeburg P. H. (1995) Domain interaction between NMDA receptor subunits and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95. Science 269, 1737–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ikemoto M., Arai H., Feng D., Tanaka K., Aoki J., Dohmae N., Takio K., Adachi H., Tsujimoto M., Inoue K. (2000) Identification of a PDZ-domain-containing protein that interacts with the scavenger receptor class B type I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6538–6543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kocher O., Krieger M. (2009) Role of the adaptor protein PDZK1 in controlling the HDL receptor SR-BI. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20, 236–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang S., Yue H., Derin R. B., Guggino W. B., Li M. (2000) Accessory protein facilitated CFTR-CFTR interaction, a molecular mechanism to potentiate the chloride channel activity. Cell 103, 169–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xia Z., Gray J. A., Compton-Toth B. A., Roth B. L. (2003) A direct interaction of PSD-95 with 5-HT2A serotonin receptors regulates receptor trafficking and signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21901–21908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hwang J. I., Kim H. S., Lee J. R., Kim E., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G. (2005) The interaction of phospholipase C-β3 with Shank2 regulates mGluR-mediated calcium signal. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12467–12473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Day P., Kobilka B. (2006) PDZ-domain arrays for identifying components of GPCR signaling complexes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 509–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stiffler M. A., Chen J. R., Grantcharova V. P., Lei Y., Fuchs D., Allen J. E., Zaslavskaia L. A., MacBeath G. (2007) PDZ domain binding selectivity is optimized across the mouse proteome. Science 317, 364–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen J. R., Chang B. H., Allen J. E., Stiffler M. A., MacBeath G. (2008) Predicting PDZ domain-peptide interactions from primary sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1041–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hwang J. I., Heo K., Shin K. J., Kim E., Yun C., Ryu S. H., Shin H. S., Suh P. G. (2000) Regulation of phospholipase C-β3 activity by Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16632–16637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oh Y. S., Jo N. W., Choi J. W., Kim H. S., Seo S. W., Kang K. O., Hwang J. I., Heo K., Kim S. H., Kim Y. H., Kim I. H., Kim J. H., Banno Y., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G. (2004) NHERF2 specifically interacts with LPA2 receptor and defines the specificity and efficiency of receptor-mediated phospholipase C-β3 activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5069–5079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wente W., Stroh T., Beaudet A., Richter D., Kreienkamp H. J. (2005) Interactions with PDZ domain proteins PIST/GOPC and PDZK1 regulate intracellular sorting of the somatostatin receptor subtype 5. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32419–32425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beuming T., Skrabanek L., Niv M. Y., Mukherjee P., Weinstein H. (2005) PDZBase: a protein-protein interaction database for PDZ-domains. Bioinformatics 21, 827–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Huizen R., Miller K., Chen D. M., Li Y., Lai Z. C., Raab R. W., Stark W. S., Shortridge R. D., Li M. (1998) Two distantly positioned PDZ domains mediate multivalent INAD-phospholipase C interactions essential for G protein-coupled signaling. EMBO J. 17, 2285–2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wes P. D., Xu X. Z., Li H. S., Chien F., Doberstein S. K., Montell C. (1999) Termination of phototransduction requires binding of the NINAC myosin III and the PDZ protein INAD. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 447–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vaccaro P., Brannetti B., Montecchi-Palazzi L., Philipp S., Helmer Citterich M., Cesareni G., Dente L. (2001) Distinct binding specificity of the multiple PDZ domains of INADL, a human protein with homology to INAD from Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 42122–42130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eddy S. R. (1998) Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14, 755–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sonnhammer E. L., Eddy S. R., Birney E., Bateman A., Durbin R. (1998) Pfam: multiple sequence alignments and HMM-profiles of protein domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 320–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wiedemann U., Boisguerin P., Leben R., Leitner D., Krause G., Moelling K., Volkmer-Engert R., Oschkinat H. (2004) Quantification of PDZ domain specificity, prediction of ligand affinity, and rational design of super-binding peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 343, 703–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fauchère J. L., Charton M., Kier L. B., Verloop A., Pliska V. (1988) Amino acid side chain parameters for correlation studies in biology and pharmacology. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 32, 269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grantham R. (1974) Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science 185, 862–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zimmerman J. M., Eliezer N., Simha R. (1968) The characterization of amino acid sequences in proteins by statistical methods. J. Theor. Biol. 21, 170–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Argos P., Rao J. K., Hargrave P. A. (1982) Structural prediction of membrane-bound proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 128, 565–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cosic I. (1994) Macromolecular bioactivity: is it resonant interaction between macromolecules? Theory and applications. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 41, 1101–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charton M., Charton B. I. (1982) The structural dependence of amino acid hydrophobicity parameters. J. Theor. Biol. 99, 629–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. D'haeseleer P. (2006) What are DNA sequence motifs? Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 423–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berg O. G., von Hippel P. H. (1987) Selection of DNA binding sites by regulatory proteins: statistical-mechanical theory and application to operators and promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 193, 723–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stormo G. D., Hartzell G. W., 3rd (1989) Identifying protein-binding sites from unaligned DNA fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 1183–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stormo G. D., Schneider T. D., Gold L. (1986) Quantitative analysis of the relationship between nucleotide sequence and functional activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 14, 6661–6679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stormo G. D., Schneider T. D., Gold L., Ehrenfeucht A. (1982) Use of the “Perceptron” algorithm to distinguish translational initiation sites in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 10, 2997–3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Staden R. (1984) Computer methods to locate signals in nucleic acid sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 12, 505–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim J. K., Choi J. W., Lim S., Kwon O., Seo J. K., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G. (2011) Phospholipase C-η1 is activated by intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and enhances GPCRs/PLC/Ca2+ signaling. Cell. Signal. 23, 1022–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rubina K., Talovskaya E., Cherenkov V., Ivanov D., Stambolsky D., Storozhevykh T., Pinelis V., Shevelev A., Parfyonova Y., Resink T., Erne P., Tkachuk V. (2005) LDL induces intracellular signalling and cell migration via atypical LDL-binding protein T-cadherin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 273, 33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Valiente M., Andrés-Pons A., Gomar B., Torres J., Gil A., Tapparel C., Antonarakis S. E., Pulido R. (2005) Binding of PTEN to specific PDZ domains contributes to PTEN protein stability and phosphorylation by microtubule-associated serine/threonine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28936–28943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ghosh M. G., Thompson D. A., Weigel R. J. (2000) PDZK1 and GREB1 are estrogen-regulated genes expressed in hormone-responsive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 60, 6367–6375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fanning A. S., Anderson J. M. (1996) Protein-protein interactions: PDZ domain networks. Curr. Biol. 6, 1385–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim J., Kim I., Yang J. S., Shin Y. E., Hwang J., Park S., Choi Y. S., Kim S. (2012) Rewiring of PDZ domain-ligand interaction network contributed to eukaryotic evolution. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jhon D. Y., Lee H. H., Park D., Lee C. W., Lee K. H., Yoo O. J., Rhee S. G. (1993) Cloning, sequencing, purification, and Gq-dependent activation of phospholipase C-β3. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 6654–6661 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fuxreiter M., Tompa P., Simon I. (2007) Local structural disorder imparts plasticity on linear motifs. Bioinformatics 23, 950–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ren S., Uversky V. N., Chen Z., Dunker A. K., Obradovic Z. (2008) Short linear motifs recognized by SH2, SH3, and Ser/Thr kinase domains are conserved in disordered protein regions. BMC Genomics 9, S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Uversky V. N., Oldfield C. J., Dunker A. K. (2005) Showing your ID: intrinsic disorder as an ID for recognition, regulation and cell signaling. J. Mol. Recognit. 18, 343–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Magidovich E., Orr I., Fass D., Abdu U., Yifrach O. (2007) Intrinsic disorder in the C-terminal domain of the Shaker voltage-activated K+ channel modulates its interaction with scaffold proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13022–13027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sánchez I. E., Beltrao P., Stricher F., Schymkowitz J., Ferkinghoff-Borg J., Rousseau F., Serrano L. (2008) Genome-wide prediction of SH2 domain targets using structural information and the FoldX algorithm. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Choi J. W., Lim S., Oh Y. S., Kim E. K., Kim S. H., Kim Y. H., Heo K., Kim J., Kim J. K., Yang Y. R., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G. (2010) Subtype-specific role of phospholipase C-β in bradykinin and LPA signaling through differential binding of different PDZ scaffold proteins. Cell. Signal. 22, 1153–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim J. K., Lim S., Kim J., Kim S., Kim J. H., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G. (2011) Subtype-specific roles of phospholipase C-β via differential interactions with PDZ domain proteins. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 51, 138–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rhee S. G. (2001) Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 281–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaushansky A., Allen J. E., Gordus A., Stiffler M. A., Karp E. S., Chang B. H., MacBeath G. (2010) Quantifying protein-protein interactions in high throughput using protein domain microarrays. Nat. Protoc. 5, 773–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hui S., Bader G. D. (2010) Proteome scanning to predict PDZ domain interactions using support vector machines. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee H. J., Zheng J. J. (2010) PDZ domains and their binding partners: structure, specificity, and modification. Cell Commun. Signal. 8, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mahon M. J., Segre G. V. (2004) Stimulation by parathyroid hormone of a NHERF-1-assembled complex consisting of the parathyroid hormone I receptor, phospholipase Cβ, and actin increases intracellular calcium in opossum kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23550–23558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Patel Y. C., Greenwood M. T., Warszynska A., Panetta R., Srikant C. B. (1994) All five cloned human somatostatin receptors (hSSTR1–5) are functionally coupled to adenylyl cyclase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 198, 605–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kreienkamp H. J., Hönck H. H., Richter D. (1997) Coupling of rat somatostatin receptor subtypes to a G-protein gated inwardly rectifying potassium channel (GIRK1). FEBS Lett. 419, 92–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brazeau P., Vale W., Burgus R., Ling N., Butcher M., Rivier J., Guillemin R. (1973) Hypothalamic polypeptide that inhibits the secretion of immunoreactive pituitary growth hormone. Science 179, 77–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barbieri F., Pattarozzi A., Gatti M., Porcile C., Bajetto A., Ferrari A., Culler M. D., Florio T. (2008) Somatostatin receptors 1, 2, and 5 cooperate in the somatostatin inhibition of C6 glioma cell proliferation in vitro via a phosphotyrosine phosphatase-η-dependent inhibition of extracellularly regulated kinase-1/2. Endocrinology 149, 4736–4746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lopez F., Estève J. P., Buscail L., Delesque N., Saint-Laurent N., Théveniau M., Nahmias C., Vaysse N., Susini C. (1997) The tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 associates with the SST2 somatostatin receptor and is an essential component of SST2-mediated inhibitory growth signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24448–24454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rosskopf D., Schürks M., Manthey I., Joisten M., Busch S., Siffert W. (2003) Signal transduction of somatostatin in human B lymphoblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 284, C179–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Akbar M., Okajima F., Tomura H., Majid M. A., Yamada Y., Seino S., Kondo Y. (1994) Phospholipase C activation and Ca2+ mobilization by cloned human somatostatin receptor subtypes 1–5, in transfected COS-7 cells. FEBS Lett. 348, 192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weckbecker G., Lewis I., Albert R., Schmid H. A., Hoyer D., Bruns C. (2003) Opportunities in somatostatin research: biological, chemical and therapeutic aspects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2, 999–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]