Abstract

Heart failure is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in industrialized countries. Although infection with microorganisms is not involved in the development of heart failure in most cases, inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of heart failure1. However, the mechanisms responsible for initiating and integrating inflammatory responses within the heart remain poorly defined. Mitochondria are evolutionary endosymbionts derived from bacteria and contain DNA similar to bacterial DNA2,3,4. Mitochondria damaged by external hemodynamic stress are degraded by the autophagy/lysosome system in cardiomyocytes5. Here, we show that mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy cell-autonomously leads to Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9-mediated inflammatory responses in cardiomyocytes and is capable of inducing myocarditis, and dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiac-specific deletion of lysosomal deoxyribonuclease (DNase) II showed no cardiac phenotypes under baseline conditions, but increased mortality and caused severe myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy 10 days after treatment with pressure overload. Early in the pathogenesis, DNase II-deficient hearts exhibited infiltration of inflammatory cells and increased mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines, with accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deposits in autolysosomes in the myocardium. Administration of the inhibitory oligodeoxynucleotides against TLR9, which is known to be activated by bacterial DNA6, or ablation of Tlr9 attenuated the development of cardiomyopathy in DNase II-deficient mice. Furthermore, Tlr9-ablation improved pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction and inflammation even in mice with wild-type Dnase2a alleles. These data provide new perspectives on the mechanism of genesis of chronic inflammation in failing hearts.

Mitochondrial DNA has similarities to bacterial DNA, which contains inflammatogenic unmethylated CpG motifs2,3,4,7,8. Damaged mitochondria are degraded by autophagy, which involves the sequestration of cytoplasmic contents in a double-membraned vacuole, the autophagosome and the fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome9. Pressure overload induces the impairment of mitochondrial cristae morphology and functions in the heart10,11. We have previously reported that autophagy is an adaptive mechanism to protect the heart from hemodynamic stress5.

DNase II, encoded by Dnase2a, is an acid DNase found in the lysosome12. DNase II in macrophages has an essential role in the degradation of the DNA of apoptotic cells after macrophages engulf them13. In the present study, we hypothesized that DNase II in cardiomyocytes digests mitochondrial DNA in the autophagy system to protect the heart from inflammation in response to hemodynamic stress.

First, we examined the alteration of DNase II activity in the heart in response to pressure overload. In wild-type mice, pressure overload by thoracic transverse aortic constriction (TAC) induced cardiac hypertrophy 1 week after TAC and heart failure 8-10 weeks after TAC5. DNase II activity was upregulated in hypertrophied hearts, but not in failing hearts (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Immunohistochemical analysis showed infiltration of CD45+ leukocytes, including CD68+ macrophages in failing hearts (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Then, we stained the heart sections with PicoGreen14, anti-LAMP2a and anti-LC315 antibodies, which was used for the detection of DNA, lysosomes, and autophagosomes, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d and 2a). We observed PicoGreen- and LAMP2a-positive deposits and PicoGreen- and LC3-positive deposits in failing hearts, but not in hypertrophied hearts, suggesting the accumulation of DNA in autolysosomes in failing hearts.

We crossed mice bearing a Dnase2aflox allele13 with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the α-myosin heavy chain promoter (α-MyHC)16, to produce Dnase2aflox/flox;α-MyHC-Cre+ (Dnase2a−/−) mice. We used Dnase2aflox/flox;α-MyHC-Cre− littermates (Dnase2a+/+) as controls. The resulting Dnase2a−/− mice were born at the expected Mendelian frequency. In Dnase2a−/− mice, we observed 90.1% reduction in the level of Dnase2a mRNA and 95.1% decrease in DNase II activity in purified adult cardiomyocyte preparation (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Physiological parameters and basal cardiac function assessed by echocardiography showed no differences between Dnase2a+/+ and Dnase2a−/− mice (Supplementary Table 1). These results indicate that DNase II does not appear to be required during normal embryonic development or for normal heart growth in the postnatal period.

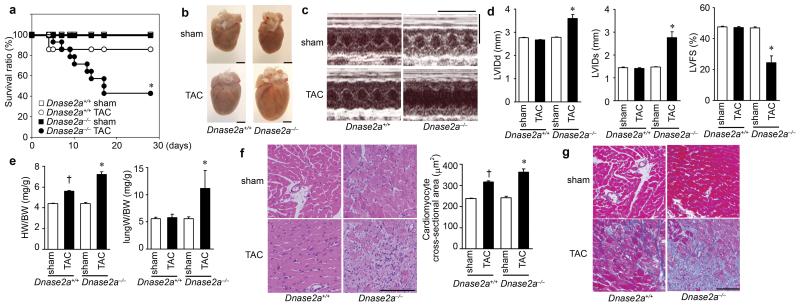

To clarify the role of DNase II in cardiac remodeling, Dnase2a−/− mice were subjected to TAC. DNase II activity was upregulated in response to pressure overload in Dnase2a+/+ hearts and was lower in sham- and TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts than that in the corresponding controls (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Twenty-eight days after TAC, 57.1% of Dnase2a−/− mice had died, whereas 85.7% of Dnase2a+/+ mice were still alive (Fig. 1a). The Dnase2a−/− hearts exhibited left ventricular dilatation and severe contractile dysfunction 10 days after TAC (Fig. 1b, c, d, Supplementary Table 2). The lung-to-body weight ratio, an index of lung congestion, was elevated in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− mice (Fig. 1e). The increases in the heart-to-body weight ratio and cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area by TAC were larger in Dnase2a−/− mice than in Dnase2a+/+ mice (Fig. 1e, f). TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts exhibited massive cell infiltration, (Fig. 1f). Immunohistochemical analysis of the hearts showed infiltration of CD45+ leukocytes, including CD68+ macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The mRNA level of interleukin (IL)-6 (Il6) was upregulated, but not other cytokine mRNAs in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts (Supplementary Fig. 4b). TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts exhibited intermuscular and perivascular fibrosis with increased mRNA expression of α2 Type I collagen (Col1a2) (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 3d). Ultrastructural analysis of TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts showed a disorganized sarcomere structure, misalignment and aggregation of mitochondria, and aberrant electron-dense structures (Supplementary Fig. 4c). The mRNA levels of atrial natriuretic factor (Nppa) and brain natriuretic peptide (Nppb) were higher in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− mice than in TAC-operated Dnase2a+/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 3d). These data suggest that DNase II plays an important role in preventing pressure overload-induced heart failure and myocarditis.

Fig. 1. TAC-induced cardiomyopathy in Dnase2a−/−mice.

a, Survival ratio after TAC (n = 7 – 14/group). b – g, 10 days after TAC. b, Gross appearance of hearts. Scale bar, 2 mm. c, Echocardiography. Scale bars, 0.2 sec and 5 mm. Echocardiographic (d) and physiological (e) parameters (n = 7 – 13/group). LVIDd and LVIDs indicate end-diastolic and end-systolic left ventricle (LV) internal dimension, respectively; LVFS, LV fractional shortening; HW/BW, heart/body weight. Hematoxylin-eosin-stained (f) and Azan-Mallory-stained (g) heart sections. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05 versus all other groups, †P < 0.05 versus sham-operated controls.

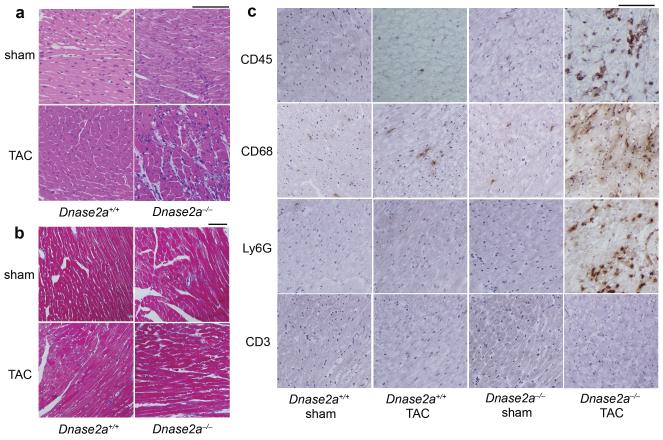

To clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying the cardiac abnormalities observed in Dnase2a−/− mice, we evaluated the phenotypes in the earlier time course after pressure overload. Chamber dilation and cardiac dysfunction developed with time after TAC in Dnase2a−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 5a). We chose to perform the analysis 2 days after TAC to minimize the contributions of operation-related events and phenomena secondary to the initial and essential molecular event that induced cardiomyopathy. TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts exhibited cell infiltration without apparent fibrosis (Fig. 2a, b) and infiltration of CD68+ macrophages and Ly6G+ cells (Fig. 2c). We detected increases in the mRNA levels of IL-1β (Il1b) and Il6, but not interferon β (Ifnb1) and γ (Ifng) or TNFα in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts (Supplementary Fig. 6a). In order to identify the source of IL-1β and IL-6, we performed in situ hybridization analysis in heart sections. Il1b and Il6 mRNA-positive cardiomyocytes were evident in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Fig. 2. Pressure overload-induced inflammatory responses in Dnase2a−/− mice 2 days after TAC.

Mice are analyzed 2 days after TAC (a – c). a, Hematoxylin-eosin-stained heart sections. Scale bar, 100 μm. b, Azan-Mallory-stained sections. Scale bar, 100 μm. c, Immunohistochemical analysis using antibodies to CD45, CD68, Ly6G and CD3. Scale bar, 100 μm.

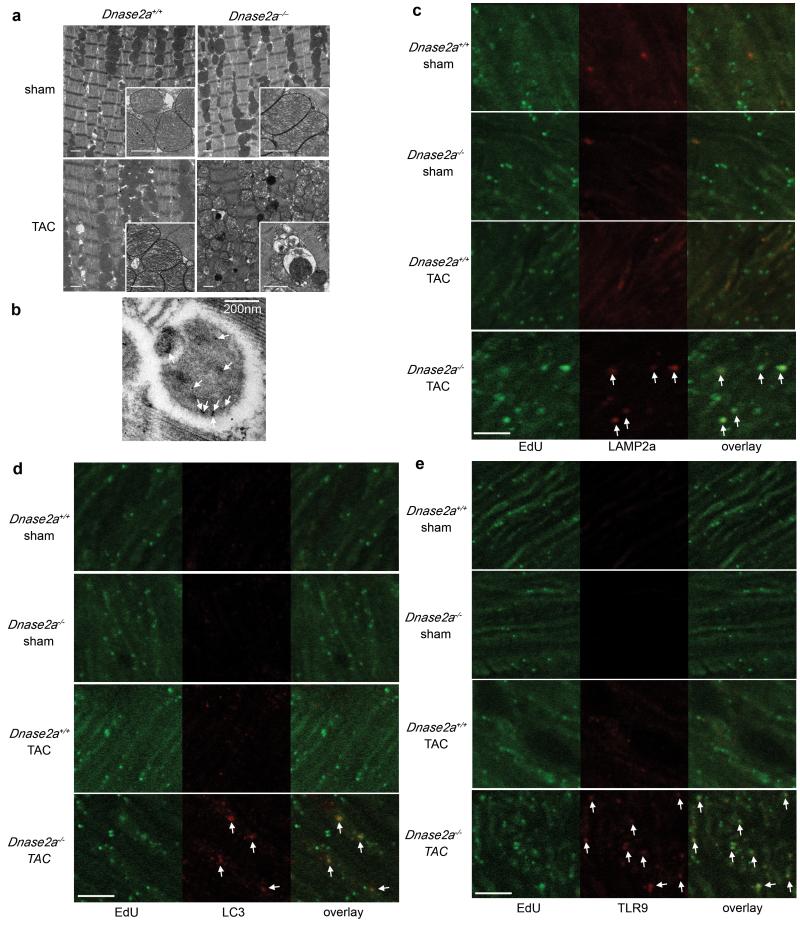

Ultrastructural analysis exhibited aberrant electron-dense deposits without apparent changes in sarcomeric and mitochondrial structures in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts (Fig. 3a). At higher magnification, the electron-dense deposits appeared to be autolysosomes (Fig. 3a). Immunoelectron microscopic analysis using anti-DNA antibody exhibited DNA deposition in autolysosomes (Fig. 3b). In TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts, we observed PicoGreen- and LAMP2a-positive deposits and PicoGreen- and LC3-positive deposits (Supplementary Fig. 6b, c, 2b). The PicoGreen-positive deposits were not TUNEL-positive (Supplementary Fig. 6d), indicating that the DNA was not derived from fragmented nuclear DNA. To label mitochondrial DNA, mice were injected with EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) 5 times before TAC. EdU, a nucleoside analog to thymidine, is incorporated into DNA during active DNA synthesis17. EdU specifically binds to mitochondrial DNA during its active DNA synthesis in non-dividing cardiomyocytes. In TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts, we observed EdU- and LAMP2a-positive deposits and EdU- and LC3-positive deposits (Fig. 3c, d, Supplementary Fig. 2c), indicating that mitochondrial DNA accumulated in autolysosomes.

Fig. 3. Deposition of mitochondrial DNA in autolysosomes in pressure-overloaded Dnase2a−/− hearts.

Mice were analyzed 2 days after TAC (a, e). a, Electron microscopic analysis. Images of mitochondria at higher magnification are shown in subsets. Scale bar, 1 μm. b, Autolysosome after incubation with anti-DNA antibody and 10 nm gold staining. Scale bar, 200 nm. Arrows indicate labeled DNA. Double staining of heart sections with EdU (green) and anti-LAMP2a antibody (red) (c), EdU (green) and anti-LC3 antibody (red) (d) or EdU and anti-TLR9 antibody (red) (e). Arrows indicate EdU-positive and LAMP2a-, LC3- or TLR9-positive structures. Scale bar, 10 μm.

The innate immune system is the major contributor to acute inflammation induced by microbial infection18. TLR9, localized in the endolysosome, senses DNA with unmethylated CpG motifs derived from bacteria and viruses. Mitochondrial DNA activates polymorphonuclear neutrophils through CpG/TLR9 interactions19. Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that TLR9 was colocalized with EdU-positive deposits (Fig. 3e). TLR9 is activated by synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN1668) that contain unmethylatedCpG6, but it is inhibited by inhibitory ligands, such as ODN208820, in which “gcgtt” in ODN1668 is replaced with “gcggg”. ODN1668 induced increases in Il1b and Il6 mRNA levels in wild-type isolated adult cardiomyocytes (data not shown). We, then, examined the effect of ODN2088 on carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) or isoproterenol-induced cell death using isolated adult cardiomyocytes to eliminate the contribution of immune cells5. CCCP, a protonophore, induces dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential. Isoproterenol caused a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in wild-type cardiomyocytes, as indicated by loss of tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) signal (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Incubation with CCCP or isoproterenol induced conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II, an essential step during autophagosome formation and treatment with the lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin A1 led to an even larger increase of LC3-II in CCCP or isoproterenol-treated cells than in control cells, indicating that CCCP or isoproterenol accelerated autophagic flux (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Isolated cardiomyocytes from Dnase2a−/− hearts were more susceptible than those from control hearts to CCCP or isoproterenol in the presence of inactive control oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN2088 control) (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d, e). CCCP upregulated the mRNA expression levels of Il1b and Il6 in Dnase2a−/− cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Fig. 7f). Incubation of Dnase2a−/− cardiomyocytes with ODN2088 attenuated the cell death and cytokine mRNA induction by CCCP treatment. Treatment of the Dnase2a−/− cardiomyocytes with 3-methyladenine, an autophagy inhibitor and rapamycin, an autophagy inducer, inhibited and enhanced the induction of the cytokine mRNA by CCCP treatment, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7g).

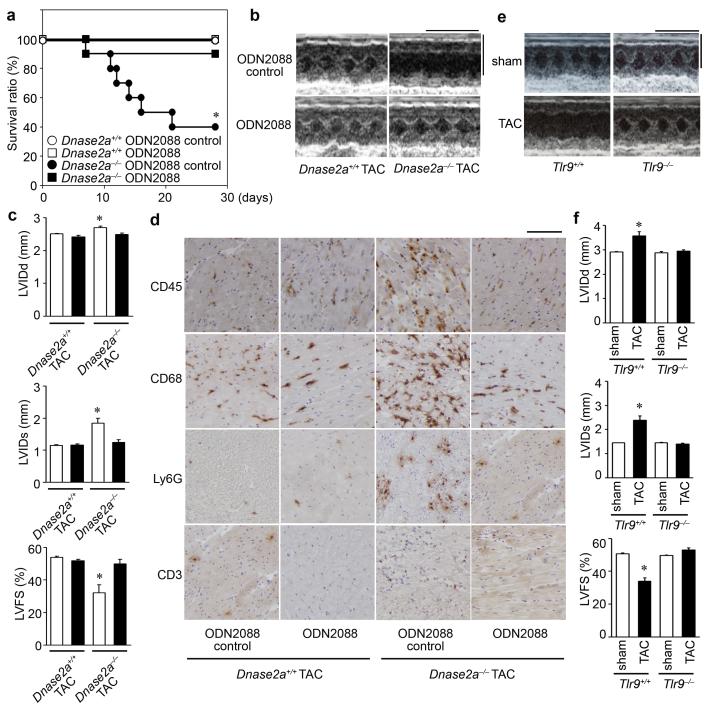

We next examined whether the inhibition of TLR9 can rescue the cardiac phenotypes in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− mice. Administration of ODN2088 resulted in the improvement of survival 28 days after TAC (Fig. 4a). ODN2088 attenuated chamber dilation and cardiac dysfunction compared to the control oligodeoxynucleotides 4 days after TAC (Fig. 4b, c, Supplementary Fig. 8a). In addition, ODN2088 inhibited infiltration of CD68+ macrophages and Ly6G+ cells, fibrosis and upregulation of Il6, Ifng, Nppa and Col1a2 mRNAs in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− hearts (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 8b, c, d, e). ODN2088 prevented cardiac remodeling for a longer time period (LVIDd (mm), 2.74 ± 0.03, 2.76 ± 0.03; LVIDs (mm), 1.37 ± 0.03, 1.34 ± 0.05; LVFS (%), 50.1 ± 0.7, 51.4 ± 1.5, before and 14 days after TAC, respectively, n = 6). Furthermore, ablation of Tlr9 rescued the cardiac phenotypes in TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Fig. 4. Inhibition of TLR9 attenuated TAC-induced heart failure.

a, Survival ratio of TAC-operated ODN-treated mice (n = 6 – 10/group). b - d, 4 days after TAC. b, Echocardiography. Scale bars, 0.2 sec and 5 mm. c, Echocardiographic parameters. Open and closed bars represent ODN2088 control- and ODN2088-treated groups, respectively (n = 5 – 8/group). d, Immunohistochemical analysis. Scale bar, 100 μm. TLR9-deficient mice were analyzed 10 weeks after TAC (e, f). e, Scale bars, 0.2 sec and 5 mm. f, Echocardiographic parameters (n = 6 – 10/group). Data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05 versus all other groups.

To examine the significance of TLR9 signaling pathway in the genesis of heart failure, we subjected TLR9-deficient mice6 to TAC. Ten weeks after TAC, TLR9-deficient mice showed smaller left ventricular dimensions, better cardiac function and less pulmonary congestion than in TAC-operated control mice (Fig. 4e, f, Supplementary Fig. 10a). The extent of fibrosis, the levels of Nppa, Nppb and Col1a2 mRNA, infiltration of CD68+ macrophages were attenuated in TLR9-deficient mice (Supplementary Fig. 10b, c, d, e). We detected no significant differences in the cytokine mRNA levels between TAC-operated groups (Supplementary Fig. 10f). Furthermore, ODN2088 improved survival of wild-type mice in a more severe TAC model (Supplementary Fig. 10g). These data indicate that the TLR9 signaling pathway is involved in inflammatory responses in failing hearts in response to pressure overload and plays an important role in the pathogenesis of heart failure.

In this study, we showed that mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy-mediated degradation cell-autonomously leads to TLR9-mediated inflammatory responses in cardiomyocytes, myocarditis, and dilated cardiomyopathy. Immune responses are initiated and perpetuated by endogenous molecules released from necrotic cells, in addition to pathogen-associated molecular patterns molecules expressed in invading microorganisms21. Cellular disruption by trauma releases mitochondrial molecules including DNA into circulation to cause systemic inflammation19. Depletion of autophagic proteins promotes cytosolic translocation of mitochondrial DNA and caspase-1-dependent cytokines mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome in response to lipopolysaccharide in macrophages22. We observed no significant difference in the amount of mitochondrial DNA in the blood between TAC-operated Dnase2a−/− and Dnase2a+/+ mice (data not shown), excluding a possibility that circulating mitochondrial DNA is causing the majority of the inflammatory responses mediated by TLR9. The mechanisms presented here do not require release of mitochondrial DNA from cardiomyocytes into extracellular space.

Increased levels of circulating proinflammatory cytokines are associated with disease progression and adverse outcomes in chronic heart failure patients1. Mitochondrial DNA plays an important role in inducing and maintaining inflammation in the heart. This mechanism might work in many chronic non-infectious inflammation-related diseases such as atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus.

Methods Summary

Animal study

The study was carried out under the supervision of the Animal Research Committee of Osaka University and in accordance with the Japanese Act on Welfare and Management of Animals (No. 105). The 12-14-week-old mice were subjected to TAC5,23 and severe TAC using 26 and 27 G needles for aortic constriction, respectively.

Biochemical assays

The DNase II activity was determined using the single radial enzyme-diffusion (SRED) method24. The mRNA levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR5.

Histological Analysis

The antibodies used were anti-mouse CD45 (ANASPEC), CD68 (Serotec), Ly6G/6C (BD Pharmingen), CD3 (Abcam), DNA (Abcam), LAMP2a (Zymed), LC325, and TLR9 (Santa-Cruz). The in situ hybridization analysis was performed using DIG RNA Labeling Kit and DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics). Hearts were embedded in the LR White resin for immunoelectron microscopy26. Heart sections were incubated in PicoGreen (Molecular Probes) for 1 hour. Twenty-four hours before TAC, mice were injected i.p. with 250 μg of EdU every 2 hours 5 times and EdU was detected using Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen).

In vitro and in vivo rescue experiments with the TLR9 inhibitor

Cardiomyocytes5 were pretreated with 1 μg/ml inhibitory CpG (ODN2088) or control (ODN2088 control) oligodeoxynucleotides for 5 hours and incubated with 20 nM CCCP or 50 μM isoproterenol for 24 hours20. The cells were loaded with TMRE (Molecular Probe) at 10 nM for 30 minutes. The mice were injected i.v. with 500 μg of the oligodeoxynucleotides 2 hours before and 2 and 4 days after TAC and every 3 days thereafter.

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. Paired data were evaluated using a Student’s t-test. A 1-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. The Kaplan-Meier method with a Logrank test was used for survival analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Shigekazu Nagata and Dr. Kohki Kawane, Kyoto University, for valuable discussions and a generous gift of Dnase2aflox/flox mice and Prof. Yasuo Uchiyama, Juntendo University, for anti-LC3 antibody. We also thank Ms. Kana Takada for technical assistance. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan and research grants from Mitsubishi Pharma Research Foundation and the British Heart Foundation (CH/11/3/29051, RG/11/12/29052).

Appendix

Methods

Animal study

The study was carried out under the supervision of the Animal Research Committee of Osaka University and in accordance with the Japanese Act on Welfare and Management of Animals (No. 105).

We crossed mice bearing a Dnase2aflox allele13 with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the α-myosin heavy chain promoter (α-MyHC)16, to produce cardiac-specific DNase II-deficient mice, Dnase2aflox/flox;α-MyHC-Cre+ (Dnase2a−/−). To generate double knockout mice of Dnase2a and Tlr9, we crossed Dnase2a−/− mice with Tlr9−/− mice6.

The 12-14-week-old male mice were subjected to TAC5,23 and severe TAC using 26 and 27 G needles for aortic constriction, respectively. Noninvasive measurements of blood pressure were carried out on mice anesthetized with 2.5% avertin using a BP Monitor for Rats and Mice Model MK-2000 (Muromachi Kikai, Tokyo, Japan) according to the instructions of the manufacturer5,23. To perform echocardiography on awakened mice, ultra-sonography (SONOS-5500, equipped with a 15-MHz linear transducer, Philips Medical Systems) was used. The heart was imaged in the two-dimensional parasternal short-axis view, and an M-mode echocardiogram of the midventricle was recorded at the level of the papillary muscles. Heart rate, intra-ventricular septum and posterior wall thickness, and end-diastolic and end-systolic internal dimensions of the LV were obtained from the M-mode image.

Measurement of DNase II activity

The DNase II activity was determined using the single radial enzyme-diffusion (SRED) method24. The heart homogenates were applied to the cylindrical wells (radius, 1.5 mm) punched in 1% (w/v) agarose gel, containing 0.05 mg/ml salmon sperm DNA (Type III), 5 μg/ml ethidium bromide, 0.5 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.7) and 10 mM EDTA. After incubation for 48 hours at 37°C, the radius of the dark circle was measured under an UV transilluminator at 312 nm. DNase II activities for the samples were determined using a standard curve constructed from the serial dilution of porcine DNase II (Sigma).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the left ventricle or cultured cardiomyocytes for analysis using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The mRNA levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR5. For reverse transcription and amplification, we used the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems) and Platinum Quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen Life Technologies), respectively. The PCR primers and probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems. The primers used are Nppa Assay ID: Mm01255747_g1, Nppb Assay ID; Mm00435304_g1, Col1a2 Assay ID; Mm01165187_m1, Gapdh Assay ID; 4352339E, Il6 Assay ID; Mm99999064_m1, Il1b Assay ID; Mm01336189_m1, Ifnb1 Assay ID; Mm00439546_s1 ,Ifng Assay ID; Mm99999071_m1, Tnf Assay ID; Mm00443260_g1, and Dnase2a Assay ID; Mm00438463_m1. We constructed quantitative PCR standard curves using the corresponding cDNA and all data were normalized to Gapdh mRNA content.

Histological Analysis

Heart samples were excised and immediately fixed in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm thick sections. Hematoxylin and eosin or Azan-Mallory staining was performed on serial sections5,23. Myocyte cross-sectional area was measured by tracing the outline of 100 to 200 myocytes in each section5,23. For immunohistochemical analysis, frozen 5-μm thick heart sections were fixed in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde. The antibodies used were anti-mouse CD45 (ANASPEC), CD68 (Serotec), Ly6G/6C (BD Pharmingen), CD3 (Abcam), LAMP2a (Zymed), LC325, and TLR9 (Santa-Cruz). For in situ hybridization analysis, the mouse IL-6 (1-636) and IL-1β (1-810) RNA probes were labeled using DIG RNA Labeling Kit and detected using DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics). For immunoelectron microscopy, frozen heart tissue was embedded in the LR White resin and the deposited DNA was detected using anti-DNA antibody (Abcam) and immunogold conjugated anti-mouse IgG (British biocell International)26. For DNA detection, heart sections were incubated in PicoGreen (Molecular Probes) for 1 hour. We used EdU to detect mitochondrial DNA in the heart section. Twenty-four hours before TAC, mice were injected i.p. with 250 μg of EdU every 2 hours 5 times and EdU was detected using Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen).

In vitro and in vivo rescue experiments with the TLR9 inhibitor

Adult mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated from 12-14-week-old male mouse hearts as we previously described5. Cardiomyocytes were pre-treated with 1 μg/ml inhibitory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN2088) (Operon) (5′-tcctggcggggaagt-3′) or control oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN2088 control) (5′-tcctgagcttgaagt-3′) for 5 hours and incubated with 20 nM CCCP or 50 μM isoproterenol for 24 hours20. Cell death was estimated by Trypan blue staining5. To monitor mitochondrial ΔΨ, the cells were loaded with TMRE (Molecular Probe) at 10 nM for 30 minutes before observation. In in vivo study, the mice were injected i.v. with 500 μg of the oligodeoxynucleotides 2 hours before and 2 days after TAC, and mice were analyzed 4 days after TAC. To estimate survival, the mice received additional administration of the oligodeoxynucleotides 4 days after TAC and every 3 days thereafter.

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. Paired data were evaluated using a Student’s t-test. A 1-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. The Kaplan-Meier method with a Logrank test was used for survival analysis.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Mann DL. Inflammatory mediators and the failing heart: Past, present, and the foreseeable future. Circ Res. 2002;91:988–998. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000043825.01705.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollack Y, Kasir J, Shemer R, Metzger S, Szyf M. Methylation pattern of mouse mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:4811–4824. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.12.4811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardon L, Burge C, Clayton DA, Karlin S. Pervasive CpG suppression in animal mitochondrial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3799–3803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial Evolution. Science. 1999;283:1476–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakai A, et al. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med. 2007;13:619–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemmi H, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taanman J-W. The mitochondrial genome: structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochim Biophys Acta - Bioenergetics. 1999;1410:103–123. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins L, Hajizadeh S, Holme E, Jonsso n. I., Tarkowski A. Endogenously oxidized mitochondrial DNA induces in vivo and in vitro inflammatory responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:995–1000. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meerson F, Zaletayeva T, Lagutchev S, Pshennikova M. Structure and mass of mitochondria in the process of compensatory hyperfunction and hypertrophy of the heart. Exp Cell Res. 1964;36:568–578. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(64)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugger H, et al. Proteomic remodelling of mitochondrial oxidative pathways in pressure overload-induced heart failure. Cardiovascl Res. 2010;85:376–384. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans CJ, Aguilera RJ. DNase II: genes, enzymes and function. Gene. 2003;322:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawane K, et al. Chronic polyarthritis caused by mammalian DNA that escapes from degradation in macrophages. Nature. 2006;443:998–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature05245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashley N, Harris D, Poulton J. Detection of mitochondrial DNA depletion in living human cells using PicoGreen staining. Exp Cell Res. 2005;303:432–446. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabeya Y, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi O, et al. Cardiac-specific disruption of the c-raf-1 gene induces cardiac dysfunction and apoptosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:937–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI20317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lentz SI, et al. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) biogenesis: Visualization and duel incorporation of BrdU and EdU into newly synthesized mtDNA in vitro. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:207–218. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.954701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Q, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stunz L, et al. Inhibitory oligonucleotides specifically block effects of stimulatory CpG oligonucleotides in B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1212–1222. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1212::AID-IMMU1212>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bianchi ME. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakahira K, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:222–230. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi O, et al. Targeted deletion of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 attenuates left ventricular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15883–15888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136717100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koizumi T. Deoxyribonuclease II (DNase II) activity in mouse tissues and body fluids. Exp Anim. 1995:169–171. doi: 10.1538/expanim.44.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Z, et al. Participation of autophagy in the degeneration process of rat hepatocytes after transplantation following prolonged cold preservation. Arch Histol Cytol. 2005;68:71–80. doi: 10.1679/aohc.68.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosgoller W, et al. Distribution of DNA in human Sertoli cell nucleoli. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:1487–1493. doi: 10.1177/41.10.7504007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.