Abstract

The complement cascade is an important part of the innate immune system, but pathological activation of this system causes tissue injury in several autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, including immune complex glomerulonephritis. We examined whether mice with targeted deletion of the gene for factor B (fB−/− mice) and selective deficiency in the alternative pathway of complement are protected from injury in the nephrotoxic serum (NTS) nephritis model of antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis. When the acute affects of the anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody were assessed, fB−/− mice developed a degree of injury similar to wild-type controls. If the mice were presensitized with sheep IgG or if the mice were followed for 5 mo postinjection, however, the fB−/− mice developed milder injury than wild-type mice. The immune response of fB−/− mice exposed to sheep IgG was similar to that of wild-type mice, but the fB−/− mice had less glomerular C3 deposition and lower levels of albuminuria. These results demonstrate that fB−/− mice are not significantly protected from acute heterologous injury in NTS nephritis but are protected from autologous injury in response to a planted glomerular antigen. Thus, although the glomerulus is resistant to antibody-initiated, alternative pathway-mediated injury, inhibition of this complement pathway may be beneficial in chronic immune complex-mediated diseases.

Keywords: glomerulonephritis, innate immune, immune complex

the complement cascade is an important part of the innate immune system, but activation of this system causes tissue injury in several autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. It has been known for decades that complement is activated in the glomeruli of patients with immune complex glomerulonephritis. IgG and IgM immune complexes are typically regarded as activating the classical pathway of complement (24). Substantial complement amplification can proceed through the alternative pathway, however, even when activation is initiated by the classical or mannose-binding lectin pathway (7). Consequently, mice deficient in alternative pathway proteins are protected in several models of antibody-mediated disease, including a model of lupus-like glomerulonephritis (1, 5, 25).

Nephrotoxic serum (NTS) nephritis is a model in which rodents are passively injected with antibodies (typically generated in rabbits or sheep) to glomerular basement membrane (GBM) components. The antibodies cause acute glomerular injury, some of which is mediated by the complement system (8, 16). Acute injury after injection with NTS is sometimes referred to as the heterologous phase of injury (19). If injected mice develop antibodies against immunoglobulin from the species in which the NTS is generated, they will produce antibodies against the NTS, and heterologous immunoglobulin bound to the GBM then acts as a planted antigen. This occurs if sufficient time is allowed to elapse after injection with the NTS (referred to as the autologous phase of injury) or if the animals are presensitized to immunoglobulin from that species (accelerated NTS) (17, 19).

Because the classical pathway facilitates the clearance of injured cells and immune complexes, deficiency of early classical pathway components can actually exacerbate immune complex glomerulonephritis (4, 17). Thus, in immune complex-mediated diseases in which the alternative pathway of complement significantly contributes to tissue injury, selective inhibition of the alternative pathway may be an advantageous therapeutic strategy. Even though complement activation by NTS is initiated through the classical pathway (8), we hypothesized that the alternative pathway would be secondarily activated by NTS and that mice deficient in the alternative pathway would be resistant to injury in this model. To test this hypothesis, we induced acute heterologous NTS nephritis, accelerated NTS nephritis, and autologous NTS nephritis in mice with a targeted deletion of the gene for factor B, an essential component of the alternative pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

NTS was raised in a sheep as previously described (16), and IgG was purified from the sheep serum using protein G (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed using FITC-conjugated antibodies against sheep IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), mouse C3 (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), and mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). For immunofluorescence microscopy of mouse IgG1 and IgG2a, biotinylated antibodies to mouse IgG1 and IgG2a were used, and detection was accomplished with streptavidin-FITC (all from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). An antibody against mouse F4/80 (Life Technologies) was used to detect macrophages. Sheep IgG (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as an antigen in an ELISA to detect mouse antibodies to sheep IgG. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated detection antibodies against mouse IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were also used in the ELISA.

Mice.

Factor B-deficient (fB−/−) mice were generated as previously described (13) and back-crossed seven generations on a C57BL/6 background. Mice with heterozygous deficiency of the complement regulatory protein Crry were generated as previously described (26). The mice were housed and maintained in the University of Colorado Center for Laboratory Animal Care in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. All animal procedures were in adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Colorado, Denver, Animal Care and Use Committee.

NTS nephritis models.

NTS nephritis was induced by three different methods. To induce acute, heterologous disease, we injected C57BL/6 or fB−/− mice via the tail vein with 0.25 or 0.375 mg of antibody purified from the serum of the immunized sheep. The mice were euthanized after 24 h, and tissues were collected. For examination of the chronic effects of NTS, mice were injected with 0.25 mg of NTS IgG and were not euthanized until 160 days after the injection. To induce accelerated autologous NTS, we immunized C57BL/6 or fB−/− mice with 0.5 mg of sheep IgG (Sigma Aldrich) emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant. After 8 days, the mice were injected with 0.25 mg of NTS IgG via the tail vein. The mice were euthanized 6 days after the injection with nephrotoxic antibody, and tissues were collected.

Renal function.

Renal function was assessed by measurement of serum urea nitrogen (SUN) using a Beckman autoanalyzer (Fullerton, CA).

Urine albumin measurement.

Urine albumin was measured by an ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX). Urine creatinine was measured using a Beckman autoanalyzer. For normalization of urine albumin excretion, the values are reported as micrograms of albumin per milligram of creatinine, and values <25 μg/mg were considered normal (16).

ELISA for antibodies to sheep IgG.

ELISA plates were coated overnight with 50 ng of sheep IgG at 4°C. The plates were then washed, and serum samples diluted 1:100–1:1,600 were added to each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were washed again, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody diluted 1:2,000 was added to each well. After 1 h, the plates were washed, and 50 μl of 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (Sigma Aldrich) were added to each well. The absorbance of each well at 405 nm was then measured.

Renal histopathology and immunofluorescence microscopy.

After the kidneys were removed from the mice, sagittal sections were fixed and embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were cut and stained with periodic acid-Schiff. To evaluate renal pathological changes, the kidneys were examined by a renal pathologist (M.H.) in a blinded manner. For each slide, the severity of glomerulonephritis, glomerulosclerosis, crescent formation, and interstitial nephritis was graded in a semiquantitative manner (on a scale of 0–4), as described previously (2). For electron microscopy, cortical samples were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The samples were processed, and images were obtained at the University of Colorado electron microscopy core.

For immunofluorescence, sagittal sections of the kidneys were snap-frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Sections (4 μm) were cut with a cryostat and stored at −70°C. The slides were later fixed with acetone and stained with FITC-conjugated antibodies. For quantitative assessment of IgG and C3 immunofluorescence, high-powered images of 10–15 glomeruli for each kidney were obtained using an inverted fluorescence microscope (model T2000, Nikon). Masks were drawn around the glomeruli, and the total fluorescence was measured using SlideBook software (version 4.0, Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO), and the results for each kidney were averaged. For assessment of macrophages, sections from four wild-type and four fB−/− mice were stained for F4/80 and examined. The number of positive cells per 15 high-powered fields were reported. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) was performed using a TACS XL Blue Label Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). Sections from wild-type and fB−/− mice were examined, and the number of positive cells in 30 glomeruli was counted in each section.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed, and graphs were created using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA). Comparison between two groups was performed by unpaired t-testing. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values are means ± SE.

RESULTS

fB−/− mice are not protected from acute heterologous NTS nephritis.

We injected mice intravenously with NTS and harvested the kidneys after 24 h. To assess whether an intact alternative pathway is necessary for the full development of injury, we compared wild-type mice with fB−/− mice (13). We tested two different doses of NTS: 0.25 mg/mouse (which induces albuminuria) and 0.375 mg/mouse (which induces albuminuria and an elevation in SUN). With both of these doses, no differences in albuminuria, SUN, or histological injury were observed between the fB−/− mice and wild-type controls (data not shown).

It is possible that alternative pathway activation in the glomerulus does not cause significant injury in this acute model because of effective control of this complement pathway by complement regulatory proteins expressed in the glomerulus. In previous studies using the acute NTS model, it was reported that mice with deficient expression of the complement regulatory proteins factor H (15) and decay-accelerating factor (10, 20) show an increased susceptibility to injury. Homozygous deficiency of Crry is lethal in utero (26). Heterozygous mice express decreased levels of this protein in the kidney, however, and display increased susceptibility to ischemic injury of the kidney compared with wild-type controls (22). We tested whether Crry+/− mice would be sensitive to NTS nephritis, but we found that the degree of albuminuria in Crry-deficient mice was not significantly different from that in wild-type controls after injection with NTS (data not shown).

fB−/− mice are protected from renal injury in accelerated NTS nephritis.

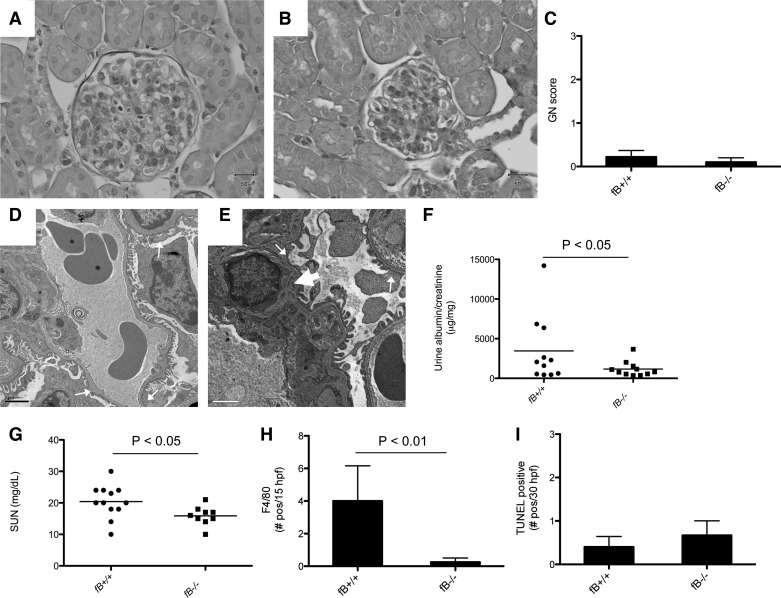

In the accelerated model of NTS nephritis, injury is mediated, in part, by the mouse's immune response to sheep IgG bound within the glomerulus. To test whether the alternative pathway plays a role in the accelerated model of NTS nephritis, we preimmunized fB−/− and wild-type mice with sheep IgG. We injected the mice with NTS 8 days after sensitization and harvested the mice 6 days after injecting them with NTS. By light microscopy, the glomeruli of some wild-type and fB−/− mice demonstrated focal proliferative changes, but there was no difference between the two strains (Fig. 1, A–C). Electron microscopy demonstrated similar findings in kidneys of wild-type and fB−/− mice, including patchy foot process effacement and small deposits (Fig. 1, D and E). Albuminuria and SUN levels were lower in fB−/− mice than in wild-type controls in the accelerated model, although there was also a trend toward lower SUN values in unmanipulated fB−/− mice (Fig. 1, F and G, Table 1). Staining for F4/80-positive cells (as a marker of macrophage infiltration) demonstrated more abundant cells in the kidneys of wild-type than fB−/− mice (Fig. 1H). TUNEL staining demonstrated a similar number of apoptotic cells in the glomeruli of wild-type and fB−/− mice (Fig. 1I).

Fig. 1.

Factor B-deficient (fB−/−) mice are protected from development of accelerated nephrotoxic serum (NTS) nephritis. Wild-type and fB−/− mice were sensitized with sheep IgG and then injected intravenously with NTS. After 5 days, tissues, urine, and serum were collected. A–C: light microscopy shows occasional proliferative changes in glomeruli of wild-type (A) and fB−/− (B) mice, but the degree of injury [glomerulonephritis (GN) score] was similar in the two strains (C). D and E: electron microscopy of wild-type (D) and fB−/− (E) mice demonstrates areas of podocyte effacement (small arrows); small deposits are seen in the mesangium (arrowhead). F and G: urine albumin/creatinine and serum urea nitrogen (SUN) levels were lower in fB−/− mice than wild-type controls. H: immunofluorescence microscopy for F4/80-positive cells; fewer F4/80-positive cells [no. positive per 30 high-power fields (hpf)] were detected in kidneys of fB−/− than wild-type mice (n = 4 for each group). I: terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) was performed to detect apoptotic cells in the glomeruli. Number of TUNEL-positive cells was not significantly different between wild-type (n = 5) and fB−/− (n = 3) mice.

Table 1.

Albuminuria and SUN levels

| Wild-Type |

fB−/− |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Albumin/creatinine, μg/mg | SUN, mg/dl | Albumin/creatinine, μg/mg | SUN, mg/dl |

| Unmanipulated | 46.5 ± 12.0 | 19.1 ± 0.8 | 81.9 ± 71.5 | 15.4 ± 1.7 |

| Accelerated NTS nephritis | 3,460 ± 1,271 | 20.4 ± 1.5 | 1,169 ± 294* | 15.9 ± 1.0* |

| Chronic NTS nephritis | 161.4 ± 32.5 | 20.0 ± 2.0 | 44.7 ± 7.3* | 18.0 ± 2.1 |

Values are means ± SE. SUN, serum urea nitrogen; NTS, nephrotoxic serum.

P < 0.05 vs. wild-type.

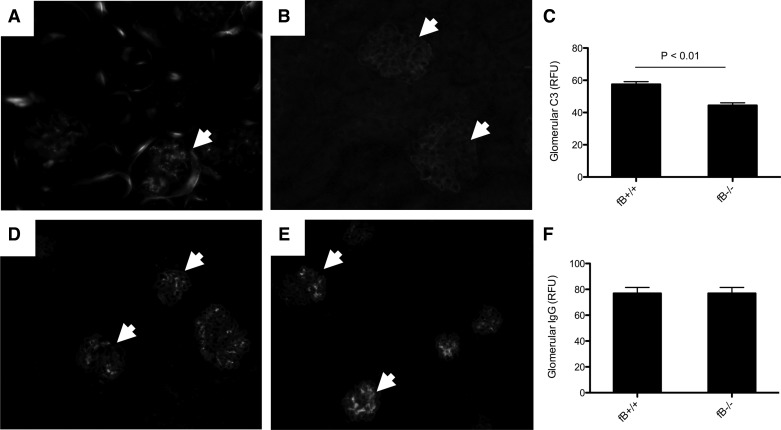

Immunofluorescence microscopy showed granular deposition of C3 in the glomeruli of wild-type mice (Fig. 2A). Staining was seen in the fB−/− mice (Fig. 2B), but quantitative assessment of the glomerular C3 demonstrated less C3 in the glomeruli of fB−/− than wild-type mice (Fig. 2C). Deposits of mouse IgG were similar in the two strains of mice (Fig. 2, D–F).

Fig. 2.

Less C3 is seen in glomeruli of fB−/− than wild-type mice with accelerated NTS nephritis. A: immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrates C3 deposition in glomeruli of wild-type mice. B and C: C3 was also seen in glomeruli of fB−/− mice (B), but levels were significantly lower than in wild-type mice (C). RFU, relative fluorescence unit. D–F: IgG deposits can be seen in glomeruli of wild-type (D) and fB−/− (E) mice, and overall IgG deposition was similar in glomeruli of the two strains of mice (F). Glomeruli are indicated with arrowheads. Original magnification ×200.

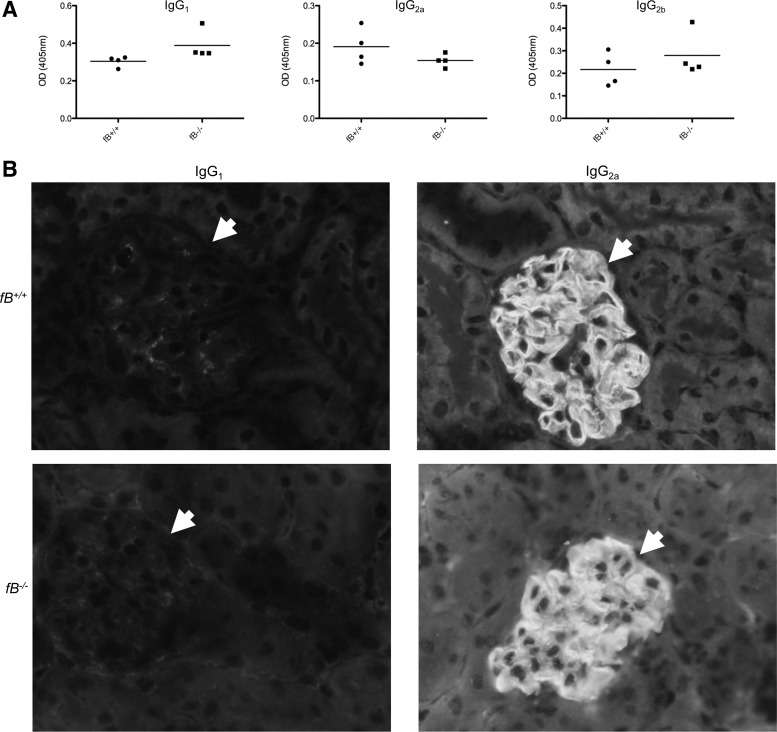

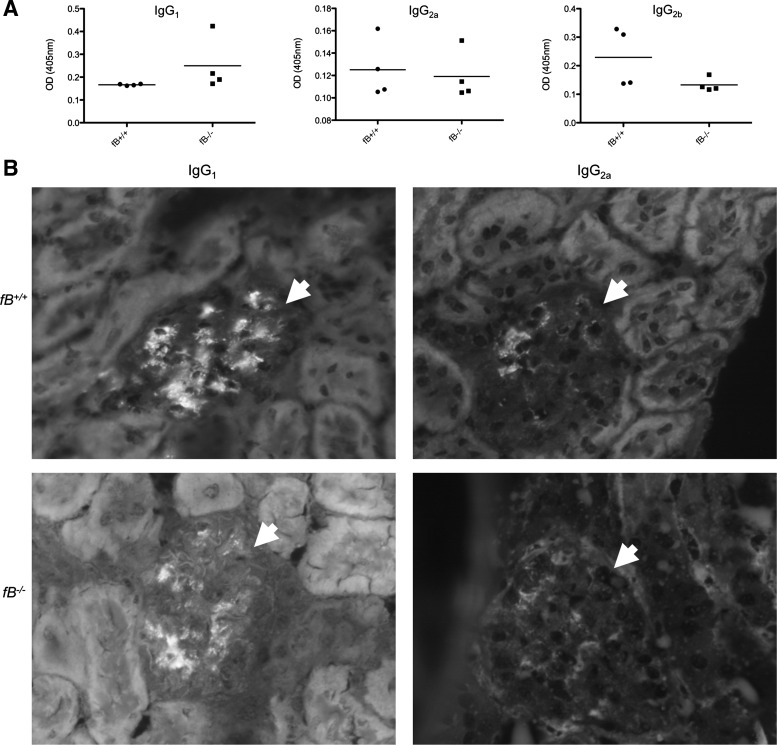

Although glomerular immune complex deposits were similar in the two strains of mice, we sought to determine whether the nature of the immune response against the sheep IgG in fB−/− mice was different from that in control mice. We performed ELISAs to assess the level of mouse anti-sheep IgG in the serum of immunized mice (Fig. 3A). No significant differences in the titers of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b against sheep IgG were detected between the two strains of mice, although there was a trend toward greater IgG1 in the fB−/− mice. Immunofluorescence microscopy for mouse IgG1 and IgG2a demonstrated linear deposition of IgG2a along the GBM of wild-type and fB−/− mice, in a pattern similar to that of the deposited sheep IgG (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

fB−/− and wild-type mice with accelerated NTS nephritis generate similar levels of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibodies against sheep IgG. A: serum levels of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibodies against sheep IgG were measured by ELISA. Levels of each isotype were similar in the two strains of mice. OD, optical density. B: immunofluorescence microscopy of kidneys for IgG1 and IgG2a demonstrates a greater abundance of IgG2a in glomeruli of wild-type and fB−/− mice. IgG2a was detected in a continuous pattern along the glomerular basement membrane. Glomeruli are indicated with arrowheads. At least 20 glomeruli were examined in 4 kidneys of each genotype. Representative images are shown. Original magnification ×400.

fB−/− mice are protected from chronic renal injury after injection with NTS.

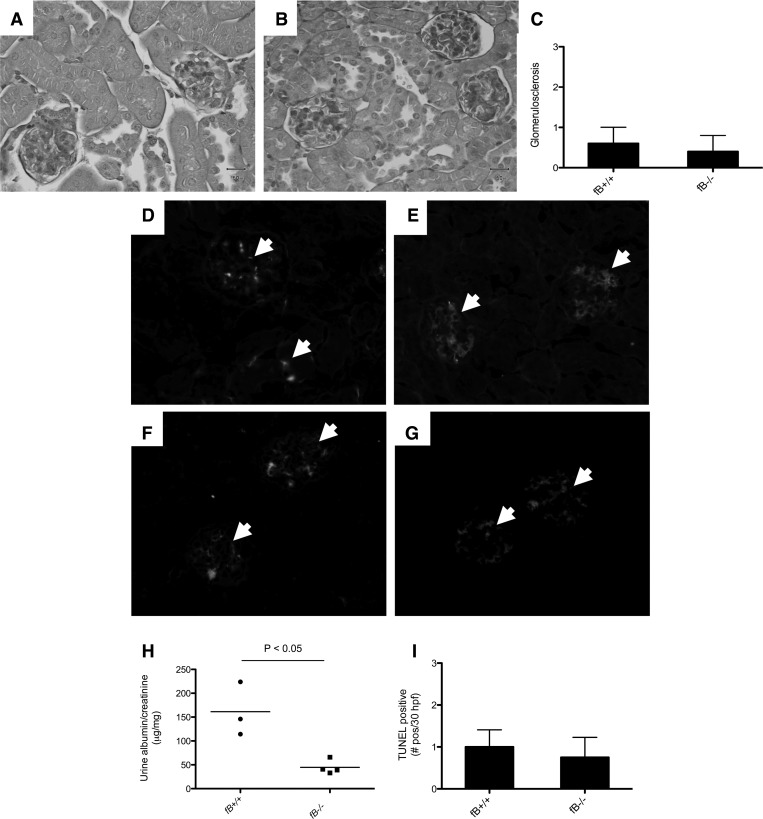

On the basis of the relative protection in fB−/− mice observed in the accelerated NTS model, we examined whether alternative pathway deficiency would protect mice from chronic injury after injection with NTS. Mice were injected with 0.25 mg of NTS and followed for 160 days. By light microscopy, only one mouse in each group demonstrated mild focal proliferative glomerulonephritis. Glomerulosclerosis was observed in some of the wild-type and fB−/− mice, but there was no significant difference between the two strains (Fig. 4, A–C). The kidneys of wild-type mice demonstrated granular C3 deposits in the glomeruli (Fig. 4D). Some glomerular C3 was observed in fB−/− mice, although it was less than in the wild-type mice (Fig. 4E). Deposits of mouse IgG were seen in both strains of mice (Fig. 4, F and G). The degree of albuminuria was significantly less than in wild-type mice at this time point (Fig. 4H). TUNEL staining demonstrated a similar number of apoptotic cells in the glomeruli of wild-type and fB−/− mice (Fig. 4I).

Fig. 4.

fB−/− mice are protected from development of chronic, autologous NTS nephritis. Wild-type and fB−/− mice were injected with NTS. Tissues and urine were collected 160 days after injection. A–C: light microscopy shows glomerulosclerosis in some of the wild-type (A) and fB−/− (B) mice, and overall degree of histological injury was similar in the two strains of mice (C). D and E: immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrates C3 deposition in glomeruli of wild-type (D) and fB−/− (E) mice. F and G: mouse IgG deposits are also detected in glomeruli of wild-type (F) and fB−/− (G) mice. Glomeruli are indicated with arrowheads. H: urine albumin/creatinine levels were lower in fB−/− mice than wild-type controls. I: TUNEL staining demonstrates no significant difference in number of apoptotic cells between the two strains (n = 4 for each group). Original magnification ×200 (A, B, and D–G).

ELISAs were performed to assess the level of mouse anti-sheep IgG in the serum of injected mice (Fig. 5A). No significant differences in the titers of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b against sheep IgG were detected between the two strains of mice. Immunofluorescence microscopy for mouse IgG1 and IgG2a demonstrated granular deposits of both isotypes of antibody in the glomeruli of wild-type and fB−/− mice (Fig. 5B), and no differences in the pattern of immunoglobulin deposition were noted. The magnitude of the albuminuria and the abundance of IgG1 and IgG2a were relatively mild in this model, raising the possibility that the protection in fB−/− mice occurred at an earlier stage of the model and that the reduced albuminuria in fB−/− mice at day 160 was the residual effect of earlier protection.

Fig. 5.

fB−/− and wild-type mice with chronic, autologous NTS nephritis generate similar levels of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibodies against sheep IgG. A: serum levels of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibodies against sheep IgG were similar in the two strains of mice. B: immunofluorescence microscopy of kidneys for IgG1 and IgG2a demonstrates granular deposits of IgG1 and IgG2a in glomeruli of wild-type and fB−/− mice. Glomeruli are indicated with arrowheads. At least 20 glomeruli were examined in 4 kidneys of each genotype. Representative images are shown. Original magnification ×400.

DISCUSSION

Uncontrolled activation of the alternative pathway of complement contributes to glomerular injury in several diseases, including a model of lupus nephritis (5, 25). We found that mice that lack the alternative pathway protein factor B are not protected from heterologous injury after injection with sheep NTS, a complement-dependent model of glomerular injury. Using a model of accelerated NTS nephritis or of chronic (heterologous) NTS nephritis, however, we did see a significant difference in the degree of albuminuria between fB−/− and wild-type mice. This suggests that control of the alternative pathway within the glomerulus is subverted or overwhelmed in these models. In the accelerated NTS model, the SUN was lower in fB−/− mice than in wild-type controls, and fewer macrophages were detected within the kidneys. There was no difference in the degree of histological injury that developed between the strains, although the overall degree of histological injury was fairly mild.

The complement system can enhance the adaptive immune response (3) and performs an important effector function in antibody-mediated immunity. Although less glomerular C3 was seen after induction of accelerated NTS in fB−/− mice than wild-type controls, glomerular IgG deposition was similar between the two strains. Furthermore, the humoral immune response of the fB−/− mice against sheep IgG in the accelerated and chronic models was comparable to that of wild-type mice. Thus the protection that fB−/− mice demonstrated in these models was likely due to reduced glomerular complement activation downstream of the immune complex formation and is less likely due to an altered immune response against the sheep IgG. In models of diseases such as lupus nephritis, on the other hand, the complement system is involved in the development of autoimmunity, so it can be difficult to isolate the effector functions of the complement system experimentally.

Antibodies are traditionally regarded as activating the classical pathway of complement (24). The alternative pathway is secondarily activated by the classical and mannose-binding lectin pathways and forms an amplification loop. Thus, even when complement is activated through one of the other pathways, amplification through the alternative pathway contributes to the generation of proinflammatory fragments. Studies have demonstrated that the contribution of the amplification loop in immune complex-mediated complement activation is greater than was originally thought (7). This may explain why the alternative pathway plays such an important role in some immune complex-mediated diseases. On the other hand, complement regulatory proteins can limit amplification through the alternative pathway on some surfaces upon which the classical pathway is activated (6). Therefore, immune complexes may engage the alternative pathway if local regulation of this pathway is lost.

Our study provides another example in which antibody-induced glomerular injury is mediated, or at least exacerbated, by engagement of the alternative pathway. Our findings also suggest that the glomerular environment is capable of suppressing alternative pathway activation in the acute heterologous model. The relatively unimportant role of the alternative pathway in this acute model may be due to effective local control of the pathway by alternative pathway regulatory proteins expressed within the glomerulus. We did not find that mice that underexpress Crry develop more severe injury, but other groups reported that mice lacking factor H or decay-accelerating factor develop more severe injury after injection with NTS (10, 15). It is possible, therefore, that these other regulatory proteins are more important for controlling complement activation in the glomerular capillary wall. The susceptibility of mice to alternative pathway-mediated injury in the accelerated and chronic models may also indicate that the mechanisms by which the alternative pathway is controlled can be bypassed over time or may be impaired by glomerular injury. We also previously showed that the alternative pathway contributes to glomerular injury in adriamycin-induced injury (a model of toxin-induced glomerular damage) (9). Together, these previous studies and the current work indicate that complement regulatory proteins effectively inhibit alternative pathway amplification of acute antibody deposition within the glomerulus but that various insults or chronic persistence of the antibodies may impair local complement regulation, permitting alternative pathway-mediated amplification of injury.

A therapeutic complement inhibitor, eculizumab, has been used in a number of patients with renal disease (11, 12, 14, 27). Agents that selectively block the alternative pathway of complement have also been developed (21, 23). Such agents could potentially block alternative pathway-mediated tissue injury without impairing some potentially beneficial effects of the classical pathway or impeding the adaptive immune response. Indeed, mice deficient in the early classical pathway component C1q develop more severe injury than wild-type controls in the accelerated NTS model (17), and deficiency of factor B appears to be more protective than deficiency of C3 in a mouse model of lupus nephritis (18, 25). Deficiency of factor B did not fully protect the mice in any of the protocols tested, indicating that other mechanisms of injury were engaged in all these settings. Our findings do, however, provide additional evidence that the alternative pathway is an important mediator of immune complex-mediated injury. Future studies will advance our understanding of how the glomerulus loses the ability to control this pathway and will delineate the role of alternative pathway inhibitors in the treatment of glomerular disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-076690 (J. M. Thurman), AI-052441 (S. A. Boackle), DK-048173 (R. J. Quigg), T32 AR-07534 (V. M. Holers), and AI-31105 (V. M. Holers).

DISCLOSURES

J. M. Thurman and V. M. Holers are consultants for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.T., S.N.T., S.A.B., R.J.Q., and V.M.H. are responsible for conception and design of the research; J.M.T., S.N.T., M.H., S.P., and M.J.G. performed the experiments; J.M.T., S.N.T., M.H., S.P., S.A.B., and V.M.H. analyzed the data; J.M.T., M.H., S.P., S.A.B., R.J.Q., and V.M.H. interpreted the results of the experiments; J.M.T. prepared the figures; J.M.T. drafted the manuscript; J.M.T., S.A.B., R.J.Q., and V.M.H. edited and revised the manuscript; J.M.T. and S.P. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banda NK, Takahashi K, Wood AK, Holers VM, Arend WP. Pathogenic complement activation in collagen antibody-induced arthritis in mice requires amplification by the alternative pathway. J Immunol 179: 4101–4109, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao L, Haas M, Kraus DM, Hack BK, Rakstang JK, Holers VM, Quigg RJ. Administration of a soluble recombinant complement C3 inhibitor protects against renal disease in MRL/lpr mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 670–679, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll MC, Fischer MB. Complement and the immune response. Curr Opin Immunol 9: 64–69, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Einav S, Pozdnyakova OO, Ma M, Carroll MC. Complement C4 is protective for lupus disease independent of C3. J Immunol 168: 1036–1041, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott MK, Jarmi T, Ruiz P, Xu Y, Holers VM, Gilkeson GS. Effects of complement factor D deficiency on the renal disease of MRL/lpr mice. Kidney Int 65: 129–138, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gershov D, Kim S, Brot N, Elkon KB. C-reactive protein binds to apoptotic cells, protects the cells from assembly of the terminal complement components, and sustains an anti-inflammatory innate immune response: implications for systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med 192: 1353–1364, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harboe M, Ulvund G, Vien L, Fung M, Mollnes TE. The quantitative role of alternative pathway amplification in classical pathway induced terminal complement activation. Clin Exp Immunol 138: 439–446, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hebert MJ, Takano T, Papayianni A, Rennke HG, Minto A, Salant DJ, Carroll MC, Brady HR. Acute nephrotoxic serum nephritis in complement knockout mice: relative roles of the classical and alternate pathways in neutrophil recruitment and proteinuria. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 2799–2803, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenderink AM, Liegel K, Ljubanovic D, Coleman KE, Gilkeson GS, Holers VM, Thurman JM. The alternative pathway of complement is activated in the glomeruli and tubulointerstitium of mice with adriamycin nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F555–F564, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin F, Emancipator SN, Salant DJ, Medof ME. Decay-accelerating factor confers protection against complement-mediated podocyte injury in acute nephrotoxic nephritis. Lab Invest 82: 563–569, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Locke JE, Magro CM, Singer AL, Segev DL, Haas M, Hillel AT, King KE, Kraus E, Lees LM, Melancon JK, Stewart ZA, Warren DS, Zachary AA, Montgomery RA. The use of antibody to complement protein C5 for salvage treatment of severe antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant 9: 231–235, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mache CJ, Acham-Roschitz B, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Kirschfink M, Zipfel PF, Roedl S, Vester U, Ring E. Complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1312–1316, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto M, Fukuda W, Circolo A, Goellner J, Strauss-Schoenberger J, Wang X, Fujita S, Hidvegi T, Chaplin DD, Colten HR. Abrogation of the alternative complement pathway by targeted deletion of murine factor B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 8720–8725, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurnberger J, Philipp T, Witzke O, Opazo Saez A, Vester U, Baba HA, Kribben A, Zimmerhackl LB, Janecke AR, Nagel M, Kirschfink M. Eculizumab for atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 360: 542–544, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickering MC, Cook HT, Warren J, Bygrave AE, Moss J, Walport MJ, Botto M. Uncontrolled C3 activation causes membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in mice deficient in complement factor H. Nat Genet 31: 424–428, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quigg RJ, He C, Lim A, Berthiaume D, Alexander JJ, Kraus D, Holers VM. Transgenic mice overexpressing the complement inhibitor Crry as a soluble protein are protected from antibody-induced glomerular injury. J Exp Med 188: 1321–1331, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robson MG, Cook HT, Botto M, Taylor PR, Busso N, Salvi R, Pusey CD, Walport MJ, Davies KA. Accelerated nephrotoxic nephritis is exacerbated in C1q-deficient mice. J Immunol 166: 6820–6828, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekine H, Reilly CM, Molano ID, Garnier G, Circolo A, Ruiz P, Holers VM, Boackle SA, Gilkeson GS. Complement component C3 is not required for full expression of immune complex glomerulonephritis in MRL/lpr mice. J Immunol 166: 6444–6451, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheerin NS, Springall T, Abe K, Sacks SH. Protection and injury: the differing roles of complement in the development of glomerular injury. Eur J Immunol 31: 1255–1260, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sogabe H, Nangaku M, Ishibashi Y, Wada T, Fujita T, Sun X, Miwa T, Madaio MP, Song WC. Increased susceptibility of decay-accelerating factor deficient mice to anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis. J Immunol 167: 2791–2797, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thurman JM, Kraus DM, Girardi G, Hourcade D, Kang HJ, Royer PA, Mitchell LM, Giclas PC, Salmon J, Gilkeson G, Holers VM. A novel inhibitor of the alternative complement pathway prevents antiphospholipid antibody-induced pregnancy loss in mice. Mol Immunol 42: 87–97, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thurman JM, Ljubanovic D, Royer PA, Kraus DM, Molina H, Barry NP, Proctor G, Levi M, Holers VM. Altered renal tubular expression of the complement inhibitor Crry permits complement activation after ischemia/reperfusion. J Clin Invest 116: 357–368, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thurman JM, Royer PA, Ljubanovic D, Dursun B, Lenderink AM, Edelstein CL, Holers VM. Treatment with an inhibitory monoclonal antibody to mouse factor B protects mice from induction of apoptosis and renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 707–715, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walport MJ. Complement. First of two parts. N Engl J Med 344: 1058–1066, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe H, Garnier G, Circolo A, Wetsel RA, Ruiz P, Holers VM, Boackle SA, Colten HR, Gilkeson GS. Modulation of renal disease in MRL/lpr mice genetically deficient in the alternative complement pathway factor B. J Immunol 164: 786–794, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu C, Mao D, Holers VM, Palanca B, Cheng AM, Molina H. A critical role for murine complement regulator Crry in fetomaternal tolerance. Science 287: 498–501, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerhackl LB, Hofer J, Cortina G, Mark W, Wurzner R, Jungraithmayr TC, Khursigara G, Kliche KO, Radauer W. Prophylactic eculizumab after renal transplantation in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 362: 1746–1748, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]