Abstract

Antagonistic microorganisms against Rhizoctonia solani were isolated and their antifungal activities were investigated. Two hundred sixteen bacterial isolates were isolated from various soil samples and 19 isolates were found to antagonize the selected plant pathogenic fungi with varying degrees. Among them, isolate C9 was selected as an antagonistic microorganism with potential for use in further studies. Treatment with the selected isolate C9 resulted in significantly reduced incidence of stem-segment colonization by R. solani AG2-2(IV) in Zoysia grass and enhanced growth of grass. Through its biochemical, physiological, and 16S rDNA characteristics, the selected bacterium was identified as Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis. Mannitol (1%) and soytone (1%) were found to be the best carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively, for use in antibiotic production. An antibiotic compound, designated as DG4, was separated and purified from ethyl acetate extract of the culture broth of isolate C9. On the basis of spectral data, including proton nuclear magneric resonance (1H NMR), carbon nuclear magneric resonance (13C NMR), and mass analyses, its chemical structure was established as a stereoisomer of acetylbutanediol. Application of the ethyl acetate extract of isolate C9 to several plant pathogens resulted in dose-dependent inhibition. Treatment with the purified compound (an isomer of acetylbuanediol) resulted in significantly inhibited growth of tested pathogens. The cell free culture supernatant of isolate C9 showed a chitinase effect on chitin medium. Results from the present study demonstrated the significant potential of the purified compound from isolate C9 for use as a biocontrol agent as well as a plant growth promoter with the ability to trigger induced systemic resistance of plants.

Keywords: Antagonistic microorganisms, Antifungal compounds, Acetylbuanediol, Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis, Plant pathogenic fungi

Introduction

Soil-borne bacteria that are antagonistic to plant pathogens could make a substantial contribution to prevention of plant diseases, and therefore represent an alternative to the use of chemical pesticides in agriculture [1]. Due to their role in plant health and soil fertility, soil and the rhizosphere have frequently been used as a model environment for screening of putative agents for use in biological control of soil-borne plant pathogens. Among the 20 genera of bacteria, Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Streptomyces spp. are widely used as biocontrol agents and Bacillus spp. has been reported to produce several antibiotics [2].

Non-pathogenic plant growth promoting rhizobacteria, Bacillus sp., form endospores and can tolerate extreme pH, temperature, and osmotic conditions; therefore, they offer several advantages over other organisms. Bacillus sp. was found to colonize the root surface, increase plant growth, and cause lysis of fungal mycelia [3]. They are regarded as safe biological agents and their potential is considered high [4]. As they are bacterial antagonists, the assumption is that their antagonistic effects are due mainly to production of antifungal antibiotics [5], which appear to play a major role in biological control of plant pathogens [6].

Biosynthesis of antibiotics from microorganisms is often regulated by nutritional and environmental factors. El-Banna [7] reported that antimicrobial substances produced by bacterial species were greatly influenced by variation of carbon sources. Several abiotic factors, such as pH and temperature, have been identified as having an influence on antibiotic production from bacteria [8]. Antifungal peptides produced by Bacillus species include mycobacillins [9], surfactins [10], mycosubtilins [11], and fungistatins [5]. It can produce a wide range of other metabolites, including chitinases and other cell wall-degrading enzymes [12, 13], volatiles [13], and compounds that elicit plant resistance mechanisms [14]. Volatile metabolites produced from Bacillus sp. have been reported to inhibit mycelia growth of Fusarium oxysporum, with the highest effect on reduction of Fusarium wilt of onion [15]. Ryu et al. [16, 17] reported on promotion of growth and induction of systemic resistance (ISR) response in Arabidopsis thaliana against Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora by volatile substances (VS) (acetylbuanediol and acetoin, same as the present purified compounds) from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens isolate IN937a and B. subtilis isolate GB03. Therefore, VS-producing bacteria can be used as biocontrol agents for protection against microbial plant diseases.

The present study was aimed at isolation of potential antagonistic soil microorganisms and purification of antifungal components. Analysis of their structure, as well as their effects on growth against tested pathogenic fungi, was conducted.

Materials and Methods

Source of sample and identification of antagonistic microorganisms

Bacterial isolates were collected from agriculture crop fields and antagonistic isolates were selected according to their inhibitory efficacy against R. solani. Standard morphological and 16S rDNA methods were used for identification of isolates. Bacterial isolates were stored at -70℃ in 15% glycerol with Triptic soy broth and pathogenic fungi were maintained in potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 4℃ for use in further studies.

Effect on stem-segment colonization of antagonistic microorganisms

Seedlings of Zoysia grass were inoculated with a mycelial suspension of R. solani AG2-2(IV) and a cell suspension (108 cfu/mL) of antagonistic microorganisms, and kept under greenhouse conditions at 27 ± 2℃, 85% r. h., and 12 hr photoperiods. After three wk of incubation, stem-segment colonization was measured as follows:

Stem-segment colonization (%) = [(0 × A + 2 × B + 3 × C + 5 × D + 8 × E + 10 × F)/{Total number of stems × highest score (10)}] × 100

where, A (0), healthy stem; B (2), normal with little blight; C (3), blight < 10%; D (5), blight = 11~50%; E (8), blight = 51~90%; F (10), blight = 91~100%.

Optimization of nutritional and environmental conditions for antibiotic production

To determine the best carbon and nitrogen sources for antibiotic production, the culture was grown on medium containing different carbon and nitrogen sources. Luria broth was used as a basal medium for optimization of carbon and nitrogen sources (except peptone and in addition with 1% glucose). For determination of optimal nutritional concentrations, 0.5% to 9% of the selected carbon and nitrogen source was used. The culture temperature and initial pH for maximum production of antibiotic substances from antagonistic microorganism was determined by incubation at 20 to 40℃ and 4.0 to 10.0, respectively.

Extraction and purification of antibiotic substances

The crude antibiotic substance was recovered from the culture filtrate of isolate C9 by solvent extraction with ethyl acetate. Ethyl acetate was added to the filtrate at a ratio of 3 : 1 (v/v) and shaken vigorously for 20 min. To obtain a crude extract, the organic layer was collected and evaporated to dryness in a vacuum evaporator at 40℃.

Different chromatographic techniques, including column chromatography, one dimensional ascending thin layer chromatography, and preparative thin layer chromatography, were used according to standard methods for further purification of the crude extract. The selected fractions were further subjected to nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic analysis.

A Bruker advance 400MHz spectrometer (Bruker Co., Billerica, MA, USA) with a 5 mm inverse probe was used to obtain NMR spectra. Proton spectra were run at a probe temperature of 25℃. The sample was dissolved in CDCl3 at a concentration of 5mg/mL (1H NMR) and 20 mg/mL (for 13C NMR). 1H chemical shifts were referenced to internal CDCl3 (4.7 ppm at all temperatures). Structures of the compounds were confirmed by comparison with reference data from available literature matching.

Antifungal activity of purified compounds

Agar well plate assay

The agar well diffusion assay, as reported by Tagg and McGiven [18], was used for determination of antagonistic activity of the crude extract and purified compounds. Briefly, PDA medium (20 mL) was poured into each sterile petri dish, followed by placement of two mycelial mats (5 mm in diameter) of the tested pathogen at the same distance from the center of the plates. A well (5 mm in diameter) was made by punching the agar with a sterile steel borer on the center of the plate and crude extract from isolate C9 or purified compound (different concentration) was poured into the well. The plates were incubated for 72 hr at 27℃ and the inhibitory activity of each concentration was expressed as the percent growth inhibition, compared to the control (solvent only used in the wells), according to the following formula:

Growth inhibition (%) = (DC - DT)/DC × 100

where, DC, diameter of control; and DT, diameter of fungal colony with treatment [19]: Each concentration was replicated three times and three separate tests were performed.

Agar diffusion assay

The agar diffusion technique described by Grover and Moore [20] was used for determination of antagonistic activity of crude antibiotics against the tested pathogen. For measurement of the amount of sterile culture supernatant, 20 mL of PDA was poured into sterilized petri dishes; crude extracts or purified compound was added along with the molten agar in order to obtain the required concentrations. Test fungi were inoculated with (5 mm in diameter) a mycelial plug and growth was recorded after 3 to 5 days of incubation at 27℃. Percentage inhibition was computed after comparison with the control.

Statistical data analysis

Data were subjected to analysis of variance using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mean values were compared using Duncan's multiple range test (DMRT) at the 5% (p < 0.05) level of significance.

Results

Selection and identification of antagonistic isolate C9

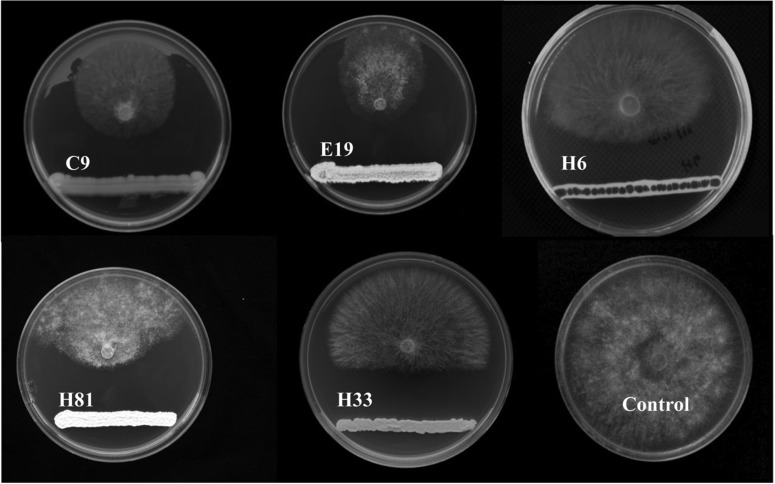

Several soil samples were screened for isolation of antagonistic microorganisms against R. solani; 67 isolates were found to be antagonists against tested fungi. According to their antagonistic efficiency against R. solani AG2-2(IV), 19 isolates were selected for screening under greenhouse conditions. Few of these isolates were found to induce a significant reduction of the severity of disease in infected Zoysia grass. On the basis of in vitro performance, the top five isolates were selected for further concentration-dependent evaluation under greenhouse conditions. According to results from the dual culture assay (Fig. 1) together with in vivo experiments (Figs. 2 and 3), isolate C9 was finally selected as an antagonistic Bacillus sp. with potential for use in control of diseases caused by R. solani AG2-2(IV) in Zoysia grass.

Fig. 1.

Efficacy of in vitro selected antagonistic isolates against Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2(IV) using the dual culture assay. Each plate number represents the antagonistic isolates. Control, culture of R. solani AG2-2(IV) on Triptic soy agar.

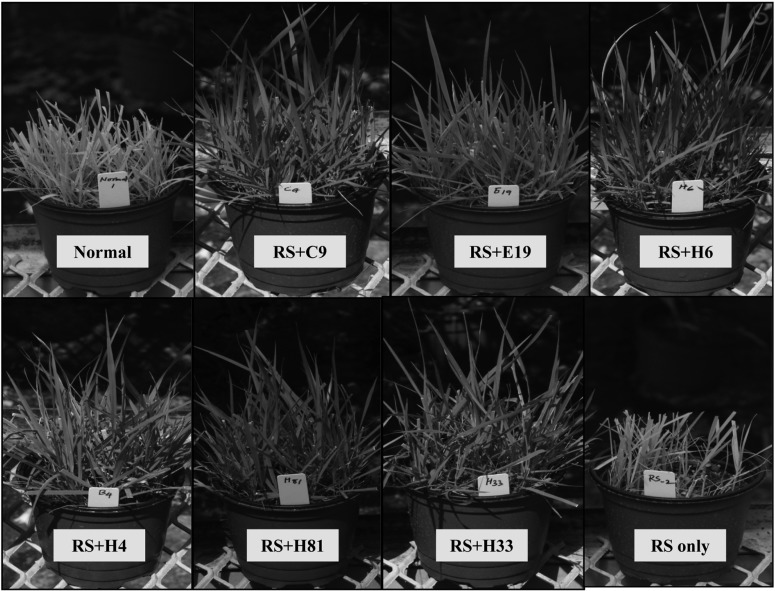

Fig. 2.

Efficiency of in vivo selected antagonistic soil microorganisms for inhibition of stem-segment colonization by Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2(IV) on Zoysia grass in a greenhouse pot experiment. Normal, normal grass pot; middle pots (treated), inoculated with both (RS + C9, E19, H6, B4, H81, and H33) = R. solani AG2-2(IV) + selected isolate; RS only (control), inoculated only R. solani AG2-2(IV).

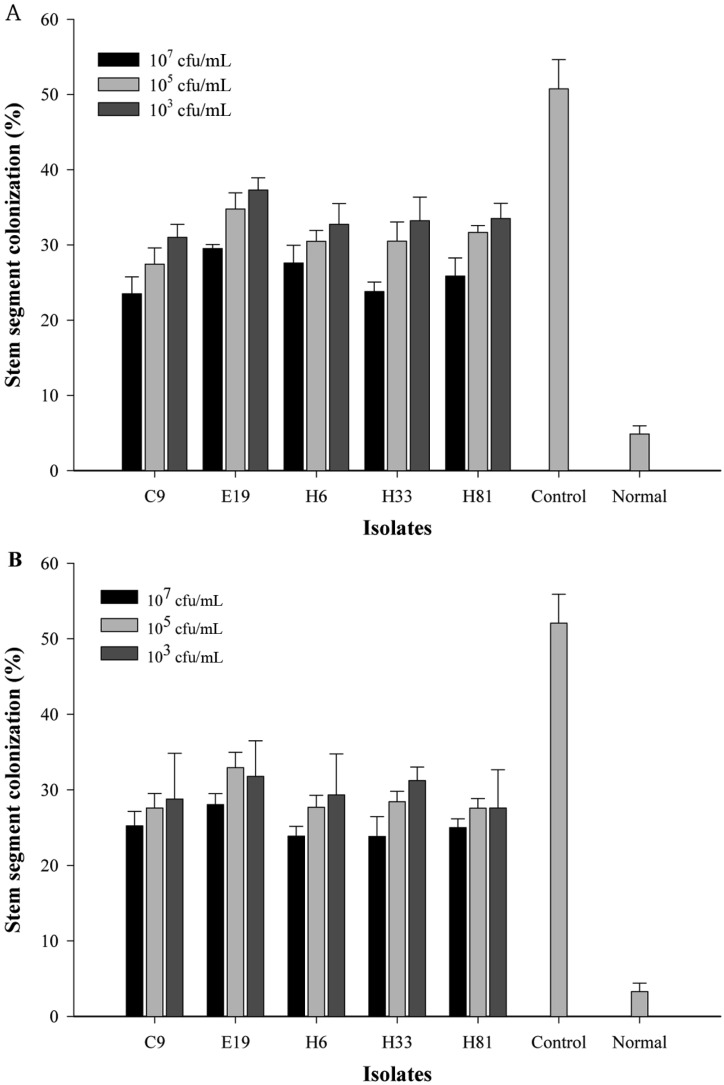

Fig. 3.

Effect of antagonistic isolates on stem-segment colonization of Zoysia grass. A, Inoculation of Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2(IV) before application of isolates for 7 days; B, Inoculation of R. solani AG2-2(IV) after application of isolates for 7 days.

According to Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, isolate C9 was classified as a bacteria belonging to the genus Bacillus. Further sequential analysis of the gene encoding 16S rDNA confirmed the isolate C9 as Bacillus sp. Comparison of the 16S rDNA gene of isolate C9 (1,200 bp) with sequences in the GenBank database revealed that the bacterium was a Bacillus sp. and showed 99% homology with the reference strain Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis (data not shown).

Optimization of nutritional and environmental conditions for isolate C9

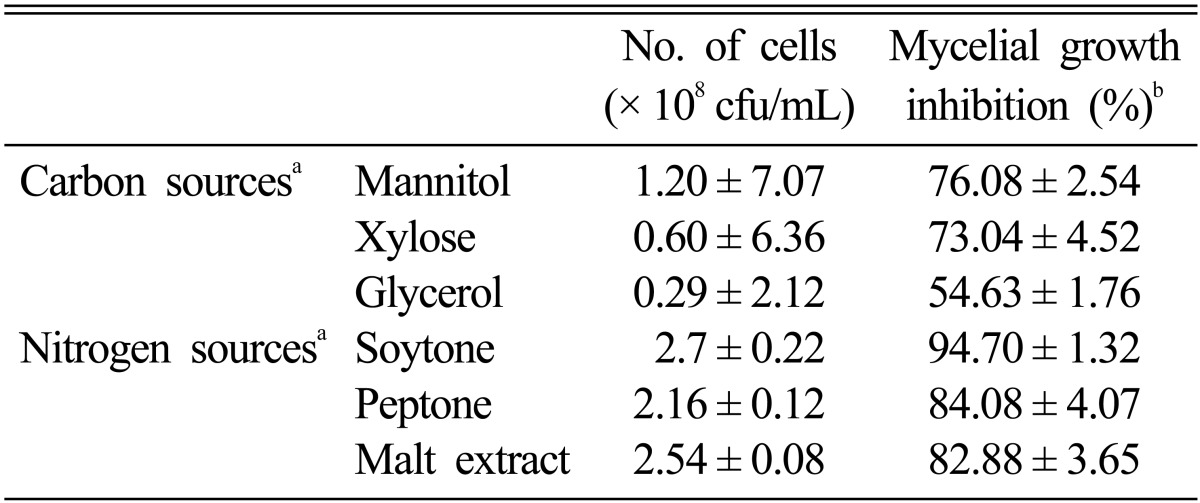

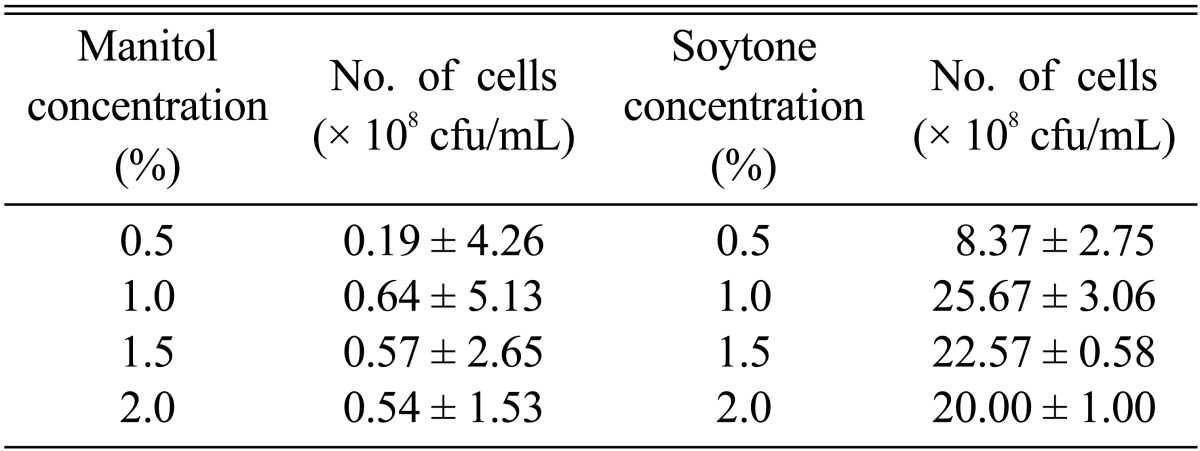

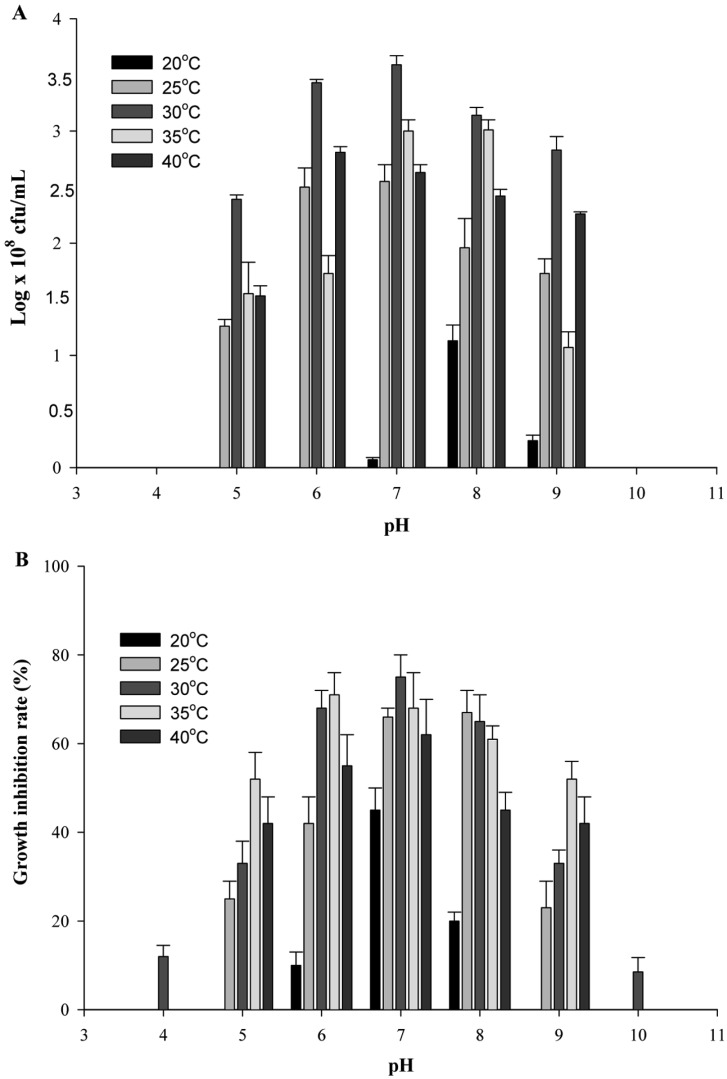

Several carbon and nitrogen sources were used for optimization of nutritional conditions required for antibiotic production from isolate C9. Efficiency was measured on the basis of viable cell number. The maximum viable cell number was achieved when mannitol was used as a carbon source (Table 1); 1% mannitol was also found to be the optimum concentration (Table 2). Production of antibiotics (mycelial growth inhibition by 76.08%) reached optimum level upon supplementation of culture media with 1% mannitol (Table 1). In a similar manner, 1% soytone was selected as the optimum concentration for attainment of maximum growth and antibiotic production (mycelial growth inhibition by 94.70%) (Tables 1 and 2). For isolate C9, the viable cell number and production of antibiotic substances showed a gradual increase from 20℃ until the optimum temperature reached 30℃ and then decreased with increasing culture temperature (Fig. 4A and 4B). pH 7.0 was the best value for antibiotic production (Fig. 4A and 4B).

Table 1.

Effect of different carbon and nitrogen sources on cell growth of Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis C9

aOptimum concentrations of carbon (1.0%) and nitrogen (1.0%) sources were used for culture of B. subtilis subsp. subtilis C9.

bThe agar diffusion technique was used for inhibition of mycelial growth against Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2(IV).

Table 2.

Effect of mannitol and soytone concentration on cell growth of Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis C9

Fig. 4.

Effect of initial pH and culture temperature on cell growth (A) and production of antibiotic substances (B) from Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis C9.

Purification of antibiotic compounds from isolate C9

Purification of antibiotic compounds from isolated C9. The ethyl acetate extract (5 g) was used for purification of antibiotic substances from isolate C9. Silica gel column (230~400 mesh ASTM; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and elution with concentrated dichloromethane/4% methanol gradient were performed. The 18 active fractions were collected and concentrated by evaporation. The major fractions (Fraction 6 and 7) were selected according to antibiotic activity for further purification. These fractions were again passed through a column, and the most bioactive fraction, designated as DG4, was collected.

1H and 13C NMR spectral analysis was performed for identification of DG4 (compound A and B). The 13C NMR spectrum showed 12 carbon signals, including 2 carbonyl carbons, 6 methyl carbons, 2 methane carbons, and 2 quaternary carbons. Of particular interest, an unequal intensity of proton and carbon signals in a ratio (3 : 1) of compound A : compound B was observed on 1H and 13C NMR spectra, evidence of a mixture of the 2 compounds. In addition, the proton and carbon signals of compounds A and B showed similar patterns, except for a difference in chemical shifts, strongly suggesting that compounds A and B are stereoisomers of each other. Based on 1H NMR, 13C NMR, 1H-1H COSY, TOCSY, and HMBC data, as well as mass experiments, the structure of DG4 was identified as a mixture of stereoisomers of 3,4-dihydroxy-3-methyl-2-pentanone.

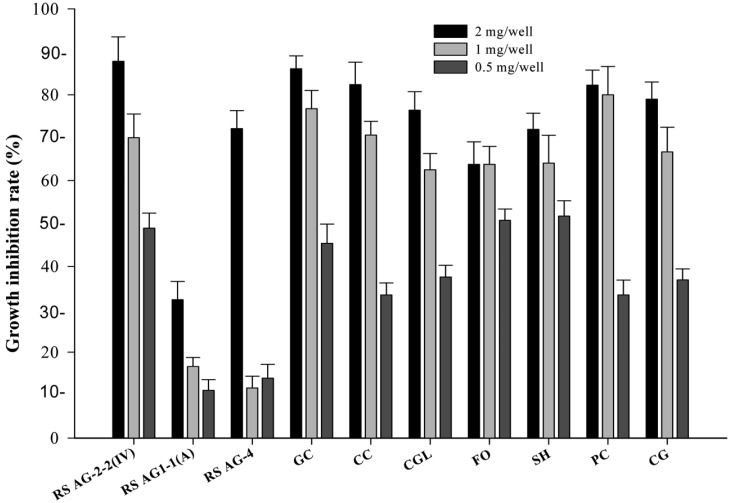

Antifungal activity of ethyl acetate extract from isolate C9

Radial growth of tested fungi was reduced at all (0.5, 1, and 2 mg/well) concentrations of ethyl acetate extract from isolate C9 (Fig. 5). Maximum inhibition of mycelial growth by the crude extract (2 mg/well) was 87.78%, 32.22%, 72.09%, 86.05%, 82.35%, 76.39%, 63.77%, 71.91%, 82.22%, and 78.95% against R. solani AG2-2(IV), R. solani AG1-1(A), R. solani AG-4, G. cingulata, C. cassiicola, C. globosum, F. oxysporum, S. homeocarpa (Dollar spot), P. cactorum, and C. gloeosporioides, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition effect of antibiotic substances extracted with ethyl acetate from Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis C9 on mycelial growth of plant pathogenic fungi. RS AG2-2(IV), Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2(IV); RS AG1-1(A), Rhizoctonia solani AG1-1(A); RS AG-4, Rhizoctonia solani AG4-4; GC, Glomerella cingulata; CC, Corynespora cassiicola; CGL, Chatomium globosum; FO, Fusarium oxysporum; SH, Sclerotinia homeocarpa; PC, Phytophthora cactorum; CG, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides.

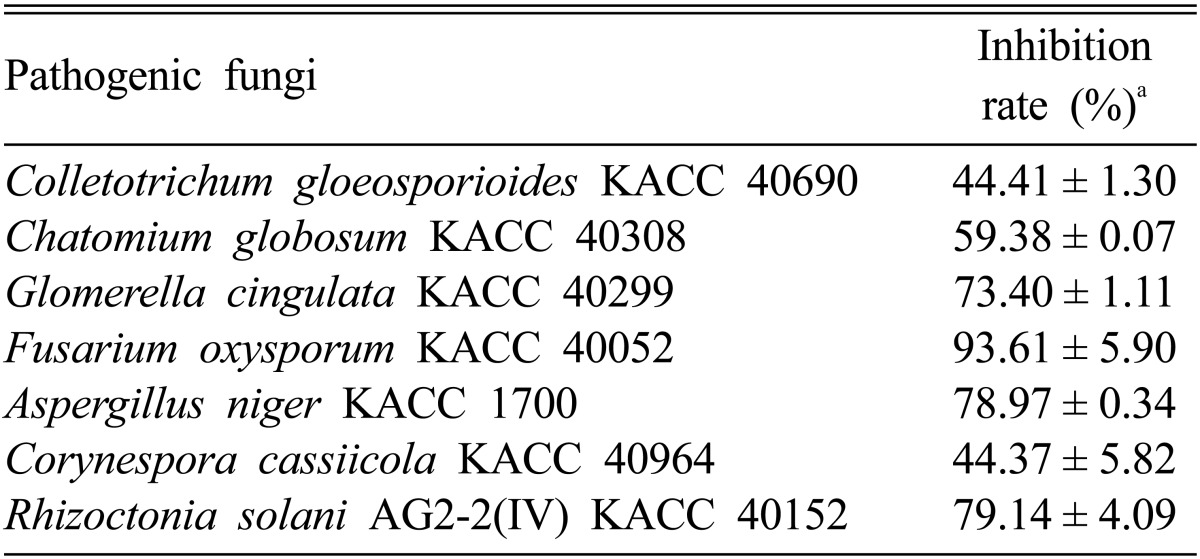

Antifungal activities of purified compound from isolate C9

Using the agar well plate assay, several common plant pathogenic fungi were treated with (5 µg/well) purified compounds produced by isolate C9. Volatile organic compound (VOCs) DG4 (isomer of acetylbuanediol) exhibited strong inhibition of mycelial growth against C. gloeosporioides KACC 40690, C. globosum KACC 40308, G. cingulata KACC 40299, F. oxysporum KACC 40052, A. niger KACC 1700, C. cassiicola KACC 40964, and R. solani AG2-2(IV) KACC 40152 by 44.41%, 59.38%, 73.40%, 93.61%, 78.97%, 44.37%, and 79.14%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Inhibition effect of DG4 (acetylbuanediol) produced by Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis C9 on mycelial growth of Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2(IV)

aThe agar well plate technique was used for inhibition of mycelial growth against various pathogens.

Enzymatic action of isolate C9

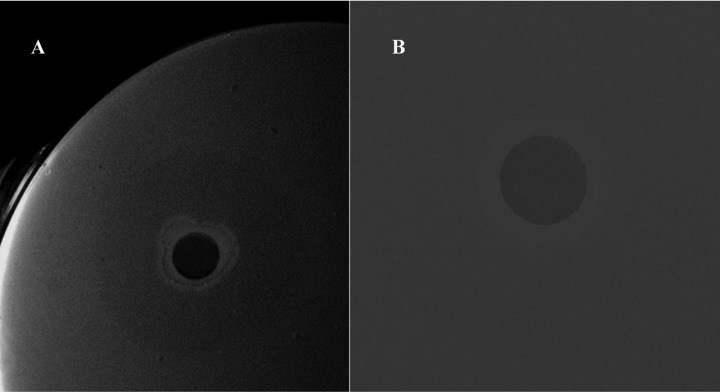

The chitin containing agar assay described by Patil et al. [21] was performed for confirmation of chitinase production from the selected isolate. A significant clear zone (35 mm in diameter) was observed after placement of cell free culture supernatant of isolate C9 by a paper disc (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Clear zone formation in chitin medium by cell free culture supernatant of Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis C9 using the paper disc diffusion method. A, Culture supernatant showed a clear zone around the paper disc; B, Control, (Triptic soy broth media) no clear zone was observed around the paper disc.

Discussion

An efficient antagonistic soil microorganism, C9, isolated from agricultural crop fields and identified as Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis C9, exhibited remarkable antagonistic activity against various plant pathogenic fungi. Most Bacillus spp. produce many kinds of antibiotics, including bacillomycin, fengycin, mycosubtilin, and zwittermicin, which are effective for suppression of the growth of target pathogens [22]. The antagonistic activity of the selected isolate C9 against several pathogenic fungi may be the antibiotic effect.

Many factors play important roles in the process of antibiotic production and consequently affect the antagonistic activity of the bacterial species. In this work, nutritional (carbon and nitrogen) composition and environmental conditions (pH and temperature) influenced consideration of isolate C9 for use in production of antibiotic substances with antifungal actions. Results of this study are consistent with those of previous studies, where the culture media had a significant influence on production of biosurfactant from B. subtilis and the highest levels of growth inhibition occurred in the presence of (2%) glucose [23]. In the present study, mannitol (1%) and soytone (1%) were selected as the optimum sources of carbon and nitrogen, respectively, for use in production of antibiotic substances. A previous study found that mannitol increased inhibition of the pathogen and was the sole carbon source for antibiotic production [24]. This finding is in agreement with that of Besson et al. [25], who reported that mannitol works as a suitable source of carbon for use in synthesis of the antibiotic, iturin A, from Bacillus subtilis. Yu et al. [26] reported that, compared with inorganic nitrogen sources, organic nitrogen sources were associated with relatively higher antifungal antibiotic production from microorganisms. The initial pH and culture temperature are critical factors for microbial growth and metabolic biosynthesis, which affect antibiotic production [27]. Findings from the present study demonstrated that the optimum pH and temperature for production of antibiotic substances from isolate C9 was 7.0 and 30℃, respectively, which was similar to the findings of EL-Abyad et al. [28], and Gong et al. [29].

Ethyl acetate crude extract and fraction DG4 (isomer of acetylbuanediol), which was selected from isolate C9, were found to induce significant inhibition of mycelial growth of various pathogenic fungi (Table 3, Fig. 5). These volatile compounds (acetylbuanediol) were previously isolated from B. subtilis GB03 and B. subtilis IN937a, and were found to induce significant reductions in disease severity of Arabidopsis caused by Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora [17]. In particular, this VOC, acetylbuanediol, was released exclusively from Bacillus spp. [30] and initiated the highest level of growth promotion of plants [16]. Application of (RR) and (SS) isomers of acetylbuanediol, similar to our purified compound DG4 (acetylbuanediol) from isolate C9, was found to trigger ISR and protect the Arabidopsis seedling from pathogen infection [17]. A similar effect was observed when Zoysia grass inoculated with pathogen was drenched with the selected isolate C9. It was found to induce significant suppression of Rhizoctonia stem-segment colonization and to promote grass health under greenhouse conditions. To the best of our knowledge, few reports have been published with regard to stimulation of ISR by VOCs from microorganisms. Findings from the present study demonstrated elicitation of ISR by volatile chemicals released from isolate C9 (plant growth promoting rhizobacteria), as well as a new role for bacterial VOCs in initiation of plant defense responses and suppression of disease severity.

Microbial VOCs may play a role in initiation of biochemical changes of either primary or secondary plant metabolism and can also inhibit protein synthesis (bind with DNA and inhibit transcription processes) of pathogens. The chitinolytic natures of some selected microorganisms are useful for control of microbial pathogens. The inhibitory effect of the present purified compound may be due to its ability to inhibit spore germination, or synthesis of β-(1, 3)-D-glucan, or inhibition of an integral component of fungal cell walls, leading to alteration of the permeability of fungal cell membranes. The chitinolytic enzyme produced by isolate C9 may be involved in biological control of plant pathogens, particularly R. solani AG2-2(IV).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Daegu University research grant, 2009.

References

- 1.Walsh UF, Morrissey JP, O'Gara F. Pseudomonas for biocontrol of phytopathogens: from functional genomics to commercial exploitation. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2001;12:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira JH, Matthee FN, Thomas AC. Biological control of Eutypa lata on grapevine by an antagonistic strain of Bacillus subtilis. Phytopathology. 1991;81:283–287. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner JT, Backman PA. Factors relating to peanut yield increases after seed treatment with Bacillus subtilis. Plant Dis. 1991;75:347–353. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim KJ, Yang YJ, Kim JG. Purification and characterization of chitinase from Streptomyces sp. M-20. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;36:185–189. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2003.36.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korzybski T, Kowszyk-Gindifer Z, Kuryłowicz W. Antibiotics: origin, nature and properties. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phae CG, Shoda M, Kubota H. Suppressive effect of Bacillus subtilis and its products on phytopathogenic microorganisms. J Ferment Bioeng. 1990;69:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.EL-Banna NM. Effect of carbon source on the antimicrobial activity of Corynebactirum kutscheri and Corynebactrium xecroris. Afr J Biotechnol. 2006;5:833–835. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raaijmakers JM, Vlami M, de Souza JT. Antibiotic production by bacterial biocontrol agents. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002;81:537–547. doi: 10.1023/a:1020501420831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majumdar SK, Bose SK. Mycobacillin, a new antinfungal antibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1958;181:134–135. doi: 10.1038/181134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kluge B, Vater J, Salnikow J, Eckart K. Studies on the biosynthesis of surfactin, a lipopeptide antibiotic from Bacillus subtilis ATCC 21332. FEBS Lett. 1988;231:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80712-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peypoux F, Michel G, Delcambe L. The structure of mycosubtilin, an antibiotic isolated from Bacillus subtilis. Eur J Biochem. 1976;63:391–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frändberg E, Schnürer J. Evaluation of a chromogenic chito-oligosaccharide analogue, p-nitrophenyl-beta-D-N,N'-diacetylchitobiose, for the measurement of the chitinolytic activity of bacteria. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;76:259–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadfi N, Chérif M, Fliss I, Boudabbous A, Antoun H. Evaluation of bacterial isolates from salty soils and Bacillus thuringiensis strains for the biocontrol of Fusarium dry rot of potato tubers. J Plant Pathol. 2001;83:101–118. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schönbeck F, Dehne HW, Beicht W. Untersuchungen zur Aktivierung unspezifischer Resistenz-mechanismen in Pflanzen. Z Pflanzenk Pflanzensch. 1980;87:654–666. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharifi Tehrani A, Ramezani M. Biological control of Fusarium oxysporum, the causal agent of onion wilt by antagonistic bacteria. Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci. 2003;68(4 Pt B):543–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryu CM, Farag MA, Hu CH, Reddy MS, Wei HX, Paré PW, Kloepper JW. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4927–4932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730845100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryu CM, Farag MA, Hu CH, Reddy MS, Kloepper JW, Paré PW. Bacterial volatiles induce systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1017–1026. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tagg JR, McGiven AR. Assay system for bacteriocins. Appl Microbiol. 1971;21:943. doi: 10.1128/am.21.5.943-943.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandey DK, Tripathi NN, Tripathi RO, Dixit SN. Fungitoxic and phyototoxic properties of essential oil of Phylis sauvolensis. Pfkrankh Pfschuz. 1982;89:334–346. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover RK, Moore JD. Toxicometric studies of fungicides against brown rot organisms Sclerotinia fructicola and S. laxa. Phytopathology. 1962;52:876–880. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil RS, Ghormade V, Deshpande MV. Chitinolytic enzymes: an exploration. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2000;26:473–483. doi: 10.1016/s0141-0229(00)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pal KK, Gardener BM. Biological control of plant pathogens. The Plant Health Instructor. 2006 http://dx.doi.org/10.1094/PHI-A-2006-1117-02. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee AK, Das K. Correlation between diverse cyclic lipopeptides production and regulation of growth and substrate utilization by Bacillus subtilis strains in a particular habitat. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2005;54:479–489. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernal G, Illanes A, Ciampi L. Isolation and partial purification of a metabolite from a mutant strain of Bacillus sp. with antibiotic activity against plant pathogenic agents. Electron J Biotechnol. 2002;5:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Besson F, Chevanet C, Michel G. Influence of the culture medium on the production of iturin A by Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:767–772. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-3-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu J, Liu Q, Liu Q, Liu X, Sun Q, Yan J, Qi X, Fan S. Effect of liquid culture requirements on antifungal antibiotic production by Streptomyces rimosus MY02. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:2087–2091. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elibol M. Optimization of medium composition for actinorhodin production by Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) with response surface methodology. Process Biochem. 2004;39:1057–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Abyad MS, El-Sayed MA, El-Shanoshowry AR, El-Sabbagh SM. Antimicrobial activities of Streptomyces pulchen, Streptomyces canescens and Streptomyces citriofluorescens against fungal and bacterial pathogens of tomato in vitro. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 1996;41:321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF02814708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gong M, Wang JD, Zhang J, Yang H, Lu XF, Pei Y, Cheng JQ. Study of the antifungal ability of Bacillus subtilis strain PY-1 in vitro and identification of the antifungal substance (iturin A) Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2006;38:233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2006.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ui S, Hosaka T, Watanaba K, Mimura A. Discovery of a new mechanism of 2,3-butanediol stereoisomer formation in Bacillus cereus YUF-4. J Ferment Bioeng. 1998;85:79–83. [Google Scholar]