Abstract

Little is known about the range and the genetic bases of naturally occurring variation for flavonoids. Using Arabidopsis thaliana seed as a model, the flavonoid content of 41 accessions and two recombinant inbred line (RIL) sets derived from divergent accessions (Cvi-0×Col-0 and Bay-0×Shahdara) were analysed. These accessions and RILs showed mainly quantitative rather than qualitative changes. To dissect the genetic architecture underlying these differences, a quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis was performed on the two segregating populations. Twenty-two flavonoid QTLs were detected that accounted for 11–64% of the observed trait variations, only one QTL being common to both RIL sets. Sixteen of these QTLs were confirmed and coarsely mapped using heterogeneous inbred families (HIFs). Three genes, namely TRANSPARENT TESTA (TT)7, TT15, and MYB12, were proposed to underlie their variations since the corresponding mutants and QTLs displayed similar specific flavonoid changes. Interestingly, most loci did not co-localize with any gene known to be involved in flavonoid metabolism. This latter result shows that novel functions have yet to be characterized and paves the way for their isolation.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, flavonoids, metabolite profiling, natural variation, quantitative trait loci

Introduction

Plants are estimated to contain >200 000 metabolites (Dixon and Strack, 2003; Saito and Matsuda, 2010) of which ∼9000 flavonoids represent a significant proportion (Harborne and Williams, 2000; Williams and Grayer, 2004). These compounds with a C6–C3–C6 carbon framework are subdivided into different classes depending on the linkage of the aromatic ring to the central C3 moiety and its degree of oxidation. The major types of flavonoids are flavonols, anthocyanins, and flavan-3-ols [also called condensed tannins or proanthocyanidins (PAs)].

These metabolites are involved in many physiological mechanisms such as flower or fruit colour (Winkel-Shirley, 2001), UV protection (Veit and Pauli, 1999; Ryan et al., 2001), interactions of plant with microbes, animals, or other plants (Harborne and Williams, 2000), abiotic stresses (Winkel-Shirley, 2002), or auxin transport (Taylor and Grotewold, 2005; Peer and Murphy, 2006; Kuhn et al., 2011). Numerous laboratory and epidemiological studies suggest a beneficial effect of flavonoids for human health, preventing the occurrence of chronic age-related diseases such as cardiovascular diseases or certain cancers (Espin et al., 2007; Butelli et al., 2008; Luceri et al., 2008). These compounds are also responsible for major organoleptic, nutritive, and processing characteristics of feed, food, and beverages, and impact many agronomical crop traits (Winkel-Shirley, 2001, 2002). For instance, high concentrations of astringent PAs can have a negative impact on the nutritive value and palatability of forages. In contrast, the presence of tannins prevents pasture bloat that can be lethal for ruminants (Lee, 1992; Waghorn and McNabb, 2003).

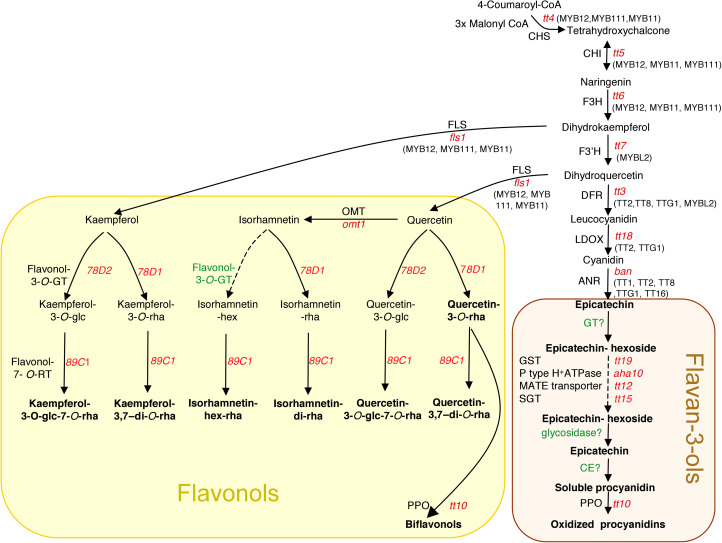

Being a powerful model for many biological questions, flavonoid biosynthesis is thus one of the best-studied metabolic pathways in plants and has been described in detail in numerous species. The common precursors are malonyl-CoA and p-coumaroyl-CoA that are condensed to chalcone intermediates by chalcone synthase (CHS) (Fig. 1 and Lepiniec et al., 2006). Among the enzymes that shape the nature and content of accumulated flavonoids, flavonoid-3'-hydroxylase (F3'H) converts dihydrokaempferol into dihydroquercetin, flavonol synthase (FLS) catalyses flavonol synthesis from dihydroflavonols, and dihydroflavol 4-reductase (DFR) is a common step toward anthocyanidins and PAs. Finally, anthocyanidin reductase (ANR) is the first committed step to PA synthesis (see Fig. 1). Regulatory proteins controlling flavonoid biosynthesis have also been characterized, such as the MYB–bHLH–WDR (MBW) complex that is involved in biosynthesis of PAs and anthocyanins (Baudry et al., 2006; Lepiniec et al., 2006) and the R2R3-MYBs PRODUCTION OF FLAVONOL GLYCOSIDE (PFG1/MYB12, PFG2/MYB11, and PFG3/MYB111) that positively regulate flavonol biosynthesis in root and the aerial part (Dubos et al., 2010; Stracke et al., 2010a, b), whereas single repeat small MYBs CAPRICE (CPC) or MYBL2 can negatively regulate anthocyanin synthesis (Dubos et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2009).

Fig. 1.

The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis seed. The different steps leading to the formation of flavonoids in Arabidopsis seed are indicated by arrows. Major flavonoids are indicated in bold. Mutants for enzymatic steps are indicated in red lower case italic letters. Regulatory proteins are given in parentheses beside their target genes that are shown in upper case letters. ANR, anthocyanidin reductase; ANS, anthocyanidin synthase (LDOX, leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase); CE, condensing enzyme; CHI, chalcone isomerase; CHS, chalcone synthase; DFR, dihydroflavonol-4-reductase; F3H, flavonol 3-hydroxylase, F3'H, flavonoid 3'-hydroxylase, FLS, flavonol synthase; glc, glucose; GST, gluthatione S-transferase; GT, glycosyltransferase; hex, hexose; OMT, methyltransferase; PPO, polyphenol oxydase; rha, rhamnose; RT, rhamnosyltransferase; SGT, UDPglucose:sterol glucosyltransferase. Steps that still need to be characterized are indicated in green with a question mark.

Arabidopsis is a good model species for the identification of genes controlling flavonoid metabolism, because it is amenable to both molecular and classical genetic analysis (Somerville and Koornneef, 2002: North et al., 2010). Several mutants affected in structural or regulatory genes have been shown to display typical flavonoid profiles that are consistent with the function of these genes or could help in their functional characterization (Pourcel et al., 2005; Routaboul et al., 2006; Marinova et al., 2007; Dubos et al., 2008). It is worth noting that most flavonoid genes have been identified by genetic approaches based on the isolation of mutants that do not accumulate coloured compounds such as anthocyanins and oxidized PAs. These previous studies essentially revealed qualitative changes controlled by a single locus, rather than quantitative variations. The functions involved in the metabolism of less coloured compounds (such as flavonols), small quantitative variations, and/or multigenic effects are more difficult to characterize (Toghe et al., 2005; Saito and Matsuda, 2010).

Recently, Arabidopsis flavonoids have been analysed using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and/or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Briefly, anthocyanins and glycosylated kaempferol flavonols are mostly found in leaves (Tohge et al., 2005; Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2008), whereas seeds contain epicatechin, PAs, and larger amounts of glycosylated quercetin flavonols (Kerhoas et al., 2006; Routaboul et al., 2006). Monoglycosylated flavonols and PAs accumulate mainly in the seed coat, whereas diglycosylated flavonols are found in the embryo (Routaboul et al., 2006). PAs that are the most abundant flavonoids (before anthocyanins) in widely consumed fruits such as apples (Zhang et al., 2003; Wojdylo et al., 2008), strawberries (Almeida et al., 2007; Buendia et al., 2010), grapes (Mane et al., 2007), and seeds and grains (Lepiniec et al., 2006; Auger et al., 2010) have often been overlooked and underestimated, since they are not easily extracted (Arranz et al., 2009; Auger et al., 2010). Interestingly, Arabidopsis seed contains large amounts of PAs with structural characteristics that are similar to those found in related crop seeds or fruits (Almeida et al., 2007; Auger et al., 2010; Buendia et al., 2010).

Despite this broad interest, very little is known about the range of natural variation of flavonoids and the genetic bases of such differences. Genetic analysis of natural variation in plants is mainly undertaken by quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping (Trontin et al., 2010) although association genetics comes of age (Atwell et al., 2010). Phenotypic variation is associated with allelic variation at molecular markers segregating in mapping populations that are derived from crosses between parental lines (Alonso-Blanco et al., 2009). Recently, QTLs that govern anthocyanidin accumulation and ripening were detected in raspberry (Graham et al., 2009; Kassim et al., 2009; McCallum et al., 2010), pepper (Chaim et al., 2003), and grape (Fournier-Level et al., 2009). QTL analysis responsible for flavonoid changes was also performed on apical tissues of poplar (Morreel et al., 2006). Regarding seeds, isoflavone content in soybean (Gutierrez-Gonzalez et al., 2010), maysin variation (c- glycosyl flavone) in maize (Zhang et al., 2003; Meyer et al., 2007), or PA changes in beans (Caldas and Blair, 2009) have been investigated. In Arabidopsis, Keurentjes and collaborators (2006) have performed an LC-MS untargeted metabolomic analysis of seedlings and also detected a few flavonol QTLs.

In this study, the metabolite profiling and genetic analysis of 41 Arabidopsis accessions and two RIL (recombinant inbred line) sets were performed to frame the range of natural variation of the major seed flavonoids and the genetic architecture underlying these changes. Studying the variations for these flavonoids among RILs enabled the detection of QTLs that were confirmed and coarsely mapped using heterogeneous inbred families (HIFs). The metabolite profiles of numerous mutants of candidate genes located near these QTLs were analysed. Among them, MYB12 (R2R3 domain transcription factor), TT15 (UDP glucose:sterol-glucosyltransferase), and TT7 (F3'H) genes not only co-localized with the considered QTLs, but their mutants displayed similar specific phenotype variation. These three genes may thus underlie the variation of the studied accessions at these loci. Nevertheless, most of the characterized loci could not be associated with any known gene involved in flavonoid metabolism, showing that combined metabolite profiling and quantitative genetic studies can reveal new loci of interest.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Forty Arabidopsis thaliana accessions from the core collection designed by the Biological Resource Centre in Versailles (McKhann et al., 2004; http://dbsgap.versailles.inra.fr/vnat/) were used to explore species-wide diversity. They were compared with the reference Columbia (Col-0) accession. A subset of 100 lines from the Cvi-0×Col-0 and from the Bay-0×Shahdara RILs sets (obtained from http://dbsgap.versailles.inra.fr/vnat/; Loudet et al., 2002; Simon et al., 2008) optimized for QTL mapping were used to map QTLs. RILs that still segregated only for a limited region around QTLs were used to generate HIFs as previously described (Loudet et al., 2005). HIF seeds were also obtained from http://dbsgap.versailles.inra.fr/vnat/. HIFs enable the comparison of the phenotypic consequences of the two parental alleles at the locus of interest in an otherwise identical (but heterogeneous) background. Tt15-2 (COB16, Ws-4 background) was also obtained from the Versailles Biological Resource Centre. All lines were grown in a controlled growth chamber in long days with a 16 h photoperiod at 170 μE m2 s−1 light intensity, and a 21 °C day/18 °C night temperature cycle, with constant humidity (65%). The GT72B1 mutant (Col-0 background) was obtained from Robert Edwards (Durham University, UK), the 78B2 and 78B3 glycosyltransferase mutants (Col-0 background) from Kazuki Saito (RIKEN Plant Science Center, Japan), the PFG1/Myb12, PFG2/MYB11, and PFG3/MYB111 single and multiple mutants (Col-0 background) from Bernd Weisshaar and Ralph Stracke (Bielefeld University, Germany), and the anl2 (Ler background) mutant from Hiriyoshi Kubo (Shinshu University, Japan)

Flavonoid analysis

Extraction of seed flavonoids was carried out using a modified protocol adapted from Routaboul et al. (2006). Seeds of accessions, RILs, and HIF lines were grown in three biological repeats. For RILs, three representative seed aliquots from the three biological repeats were pooled before flavonoid extraction. All seed samples were ground for 90 s at maximum speed with a ‘FastPrep-24 homogenizer’ (MP Biomedicals, Solon, USA), lines derived from Cvi-0×Col-0 in 1 ml of acetonitrile/water (3/1; v/v), and Bay-0×Shahdara lines in 1 ml of methanol/acetone/water/trifluoroacetic acid (30/42/28/0.05; v/v/v/v) to maximize PA extraction. A 4 μg aliquot of apigenin was added as an internal standard. Following centrifugation the pellet was extracted further with 1 ml of the same solvent mixes overnight at 4°C. The two extracts were pooled. The pellet was preserved for insoluble PA analysis. LC-MS analyses of individual flavonoids were realized as previously described (Kerhoas et al., 2006; Routaboul et al., 2006) using a ‘Quattro LC’ with an ESI ‘Z-Spray’ interface (MicroMass, Manchester, UK), an Alliance 2695 RP-HPLC system, and a Waters 2487 UV detector set at 280 nm (Waters, USA). Flavonol contents were expressed relative to quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside, rutin, and epicatechin (Extrasynthese, France) external standards, or monoglycosylated and di-glycosylated flavonols and flavan-3-ols (PAs), respectively.

PA oligomers and polymers were hydrolysed into coloured anthocyanidin and measured at 550 nm using a calibration curve made with commercial cyanidin chloride (Extrasynthese, France).

QTL analysis

QTL analyses were performed using the Unix version of QTL CARTOGRAPHER 1.14 (Lander and Botstein, 1989; Basten et al., 2000), and standard methods for interval mapping (IM) and composite interval mapping (CIM) (Loudet et al., 2003). First, IM (Lander and Botstein, 1989) was carried out to determine putative QTLs involved in the variation of the trait, and then CIM model 6 of QTL CARTOGRAPHER was performed on the same data: the closest marker to each local LOD score peak (putative QTL) was used as a cofactor to control the genetic background while testing at another genomic position. When a cofactor was also a flanking marker of the tested region, it was excluded from the model. The number of cofactors involved in the models varied between one and three. The walking speed chosen for QTL analysis was 0.1 cM. The global LOD significance threshold (2.3 LOD) was estimated from several permutation test analyses, as suggested by Churchill and Doerge (1994). QTL co-localization was considered only when different QTLs peaked in a window of ≤5 cM (that was a priori chosen because it represents a conservative support interval). Additive effects (‘2a’) of detected QTLs were estimated from CIM results as representing the mean effect of the replacement of the Cvi (or Bay) alleles by Col [or Shahdara (Sha)] alleles at the locus. The contribution of each identified QTL to the total phenotypic variation (R 2) was estimated by variance component analysis, using phenotypic values for each RIL. The model used the genotype at the closest marker to the corresponding detected QTL as random factors in analysis if variance (ANOVA), performed using the aov function in R. Only homozygous genotypes were included in the ANOVA.

Hierarchical clustering was performed using Genesis 1.7.5 (Institute for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Graz University of Technology, http://genome.tugraz.at). Distances were calculated using complete linkage clustering and Pearson correlations.

The flavonoid contents of selected lines of the two RIL sets are given in Supplementary Tables S5 and 6 available at JXB online allowing calculation of minor QTLs that have not been presented in the Results section.

Results

Comparative seed flavonoid analysis between Arabidopsis accessions shows quantitative rather than qualitative differences

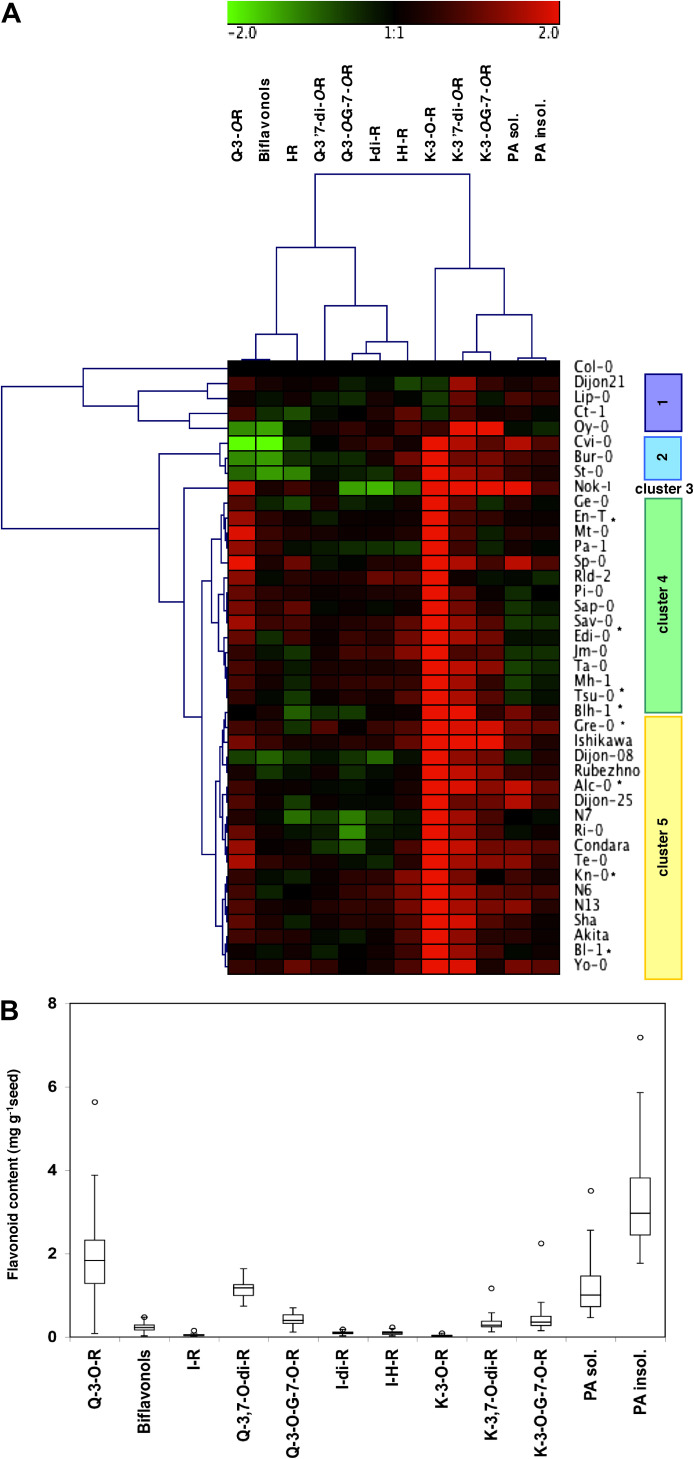

The seed flavonoids accumulated in three widely used accessions, namely Col-0, Ws-4, and Ler, have been characterized previously (Kerhoas et al., 2006; Routaboul et al., 2006). Here this analysis was extended, selecting 40 novel accessions from the Versailles core collection (McKhann et al., 2004), defined to maximize genetic diversity among 265 accessions distributed worldwide (Fig. 2A). Mature seed extracts were analysed using LC-MS to quantify individually the different flavonols. In addition, PA contents were assessed using acid-catalysed hydrolysis (Porter et al., 1986) both on the extract (hereafter called soluble PAs) and on the remaining pellet (hereafter called insoluble PAs). The first observation was that, among the accessions tested, essentially quantitative rather than qualitative variations were observed (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online). All the flavonoids previously characterized in Col-0, Ws-4, or Ler were found in all the accessions. Five accessions illustrated the range of changes observed, namely Col-0, Cvi-0, Nok-1, Sp-0, and Sha (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. S1). Col-0 contained the least kaempferol derivatives and was clearly different from other accessions. Cvi-0 had low quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside content and, consequently, low levels of the derived biflavonols (Pourcel et al., 2005), whereas PAs were 3-fold higher. Interestingly, these three compounds are mainly accumulated in the seed coat (Routaboul et al., 2006). Flavonols and PAs accumulated to the highest levels in the Nok-1 accession in which flavonoids account for 1.7% of dry weight (DW). Sp-0 had the highest quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside content with a concomitant increase in PAs. It should be noted that the largest variations in flavonoids were obtained for some seed coat-specific flavonols, such as quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside (from 0.008% in Cvi-0 up to 0.6% of DW in Sp-0) or PAs (from 0.2% in Sav-0 up to 0.9% DW in Gre-0), or kaempferol derivatives (from 0.04% in Col-0 to 0.3% DW in Nok-1).

Fig. 2.

Natural variation of seed flavonoids in Arabidopsis. (A) Hierarchical clustering analysis of mature seed flavonoid accumulation in 40 accessions compared with Col-0. Log2 % of from three (*or two) independent measurements ±SE. Flavonoid contents for each accession and correlation between the different compounds are given in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively, at JXB online. (B) Boxplot analysis of flavonoid content in accessions giving the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile and outlier, respectively, from bottom to top. G, glucoside; H, hexoside; I, isorhamnetin; insol., insoluble; K, kaempferol; Q, quercetin; PA, proanthocyanidin; R, rhamnoside; sol., soluble.

Analysis of Sha accessions uncovers new biosynthetic step

The Shahdara accession contained three novel flavonol-hexoside-rhamnoside derivatives. They possessed the same glycosylations but a different quercetin, kaempferol, or isorhamnetin aglycone ([M+H]+=611, 595, and 625; [M+H-hexose]+=449, 433, and 463; and [M+H-hexose-rhamnose]+=303, 287, and 317, respectively). These compounds had a retention time of ∼1 min before the corresponding aglycone-3-O-glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside isomers and are thus different from these previously characterized flavonols (Kerhoas et al., 2006; Supplementary Fig. S5 at JXB online). Nevertheless, Sha was also able to synthesize all the flavonols detected in Bay-0. This result suggested that a novel and specific glycosyl transferase that catalyses the production of flavonol-hexoside-rhamnoside is active in Shahdara but not in Bay-0.

Relationships between the contents of different flavonoids in mature seeds

One could expect to observe some correlations between the accumulations of different flavonoids that belong to various subpathways or represent related quantitative traits. Alternatively, the lack of correlation may reveal regulatory steps for which specific QTLs should be detected. These correlations were measured and are depicted as a tree (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Tables S2 – S4 at JXB online). Some of these statistically significant correlations could be foreseen, such as the one between the accumulation of precursor quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside and its derived biflavonol products (Pourcel et al., 2005) (r=0.71, P < 0.0001) or between soluble and insoluble PAs (r=0.84, P < 0.0001). This also shows that some accessions such as Cvi-0 or Bur-0 display a more contrasted quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside/biflavonol ratio relative to that of Sp-0 or Edi-0. However, the correlation between kaempferols and PAs was unexpected (r=0.52, P < 0.0001 and r=0.33, P=0.048 between soluble PA and kaempferol-3,7-di-rhamnoside or kaempferol-3-O-glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside, respectively).

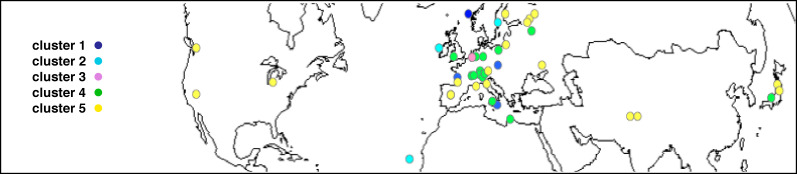

A clustering of accessions based on their flavonoid profile was carried out (Fig. 2A). Five major groups could be distinguished. In Arabidopsis, it is often difficult to associate specific genotypes with geographic origin (Anastasio et al., 2011) since human activities tend to homogenize variation among populations, especially in Europe and North America, and recolonization events from circum Mediterranean glacial refugees have also been proposed to occur (Mitchell-Olds and Schmitt, 2006). The accessions of cluster 1 contained a higher level of phenotypic variation than other clusters (these accessions could be considered as separate clusters) and were characterized by less kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside. Cluster 2 represented western European accessions (Fig. 3) that accumulated less quercetin derivatives and more PAs and kaempferol (such as Cvi-0; see Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). Cluster 3 contained a single accession from The Netherlands, Nok-1, that stood alone away from the other accessions due to its overall high levels of flavonoids. Accessions of cluster 4 included many central European accessions that had, on average, more quercetin derivatives but less PAs (such as Sp-0), whereas cluster 5 is the only group containing Asian and North American accessions that appeared to contain more PAs (such as Shahdara).

Fig. 3.

Geographical distribution of studied accessions (dark blue, light blue, pink, green, and yellow dots correspond to clusters 1–5 of Fig. 2, respectively)

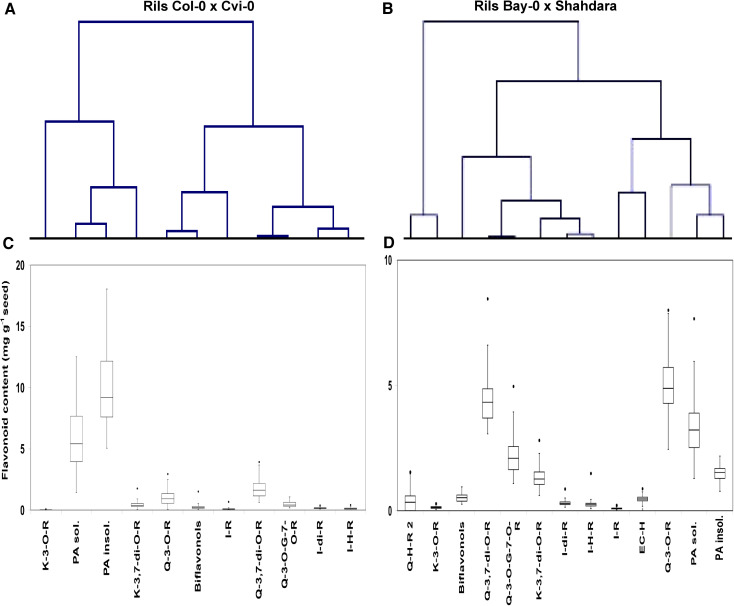

Extended flavonoid variation in two recombinant inbred line sets

To dissect these natural variations genetically, selected progeny of two RIL populations, Cvi-0×Col-0 and Bay-0×Shahdara (Loudet et al., 2002; Simon et al., 2008), were analysed. Correlations between the different flavonoid contents in the Cvi-0×Col-0 RIL set were similar to those observed among the accessions (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Table S3 at JXB online). In contrast, correlations were generally weaker or no longer existent in the Bay-0×Shahdara RIL population, such as that between quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside and one of its products the biflavonols (r= –0.07, P > 0.5), between soluble and insoluble PAs (r=0.48, P < 0.0001) or between PAs and kaempferols (Fig. 4B; Fig. 4A; Supplementary Table S3). Variations in flavonoid content in both RIL populations are presented in Fig. 4C and D. The two RIL populations showed transgressive segregation from their parents for most traits, especially for diglycosylated quercetins and isorhamnetin derivatives that displayed small differences among the parents. This should indicate that all four parents have positive-effect alleles for these compounds and that numerous QTLs are likely to be detected.

Fig. 4.

Natural variation among recombinant inbred lines (RILs) derived from the Cvi-0×Col-0 and Bay-0×Shahdara crosses. Relationships between mature seed flavonoid contents in two RIL populations Cvi-0×Col-0 (A) and Bay-0×Shahdara (B). log2 % of Col-0 or Bay-0 and boxplot analysis for each flavonoid giving the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and outlier, from the bottom to the top (C and D). G, glucoside; H, hexoside; I, isorhamnetin; insol., insoluble; K, kaempferol; Q, quercetin; PA, proanthocyanidin; R, rhamnoside; sol., soluble.

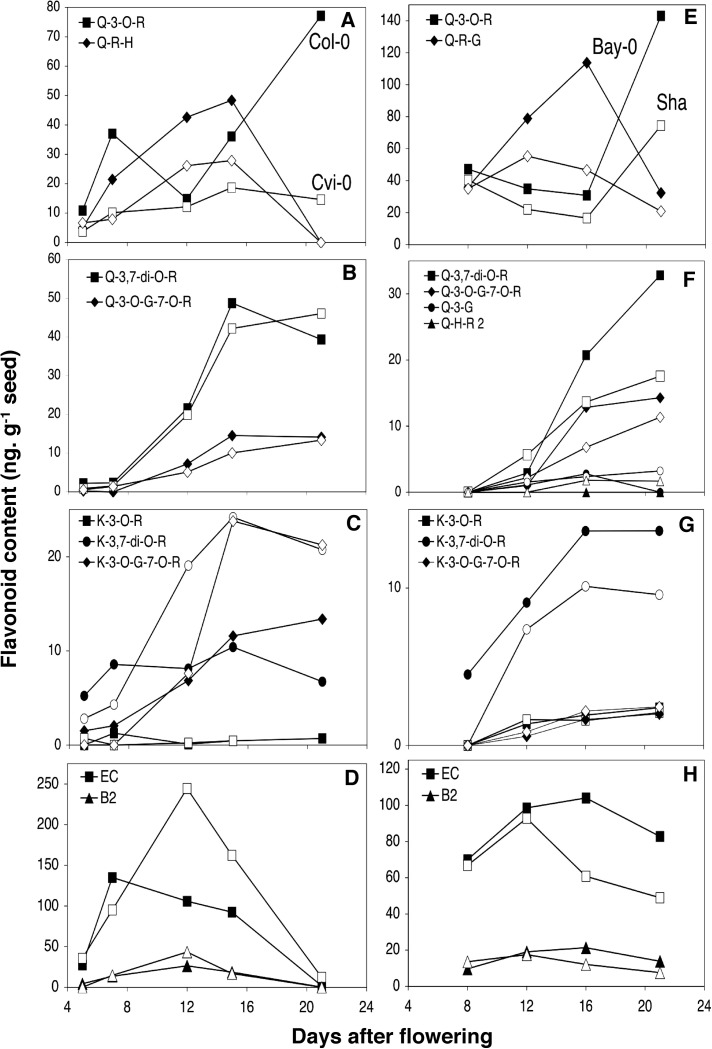

Developing seeds from the four parental accessions were also analysed (Fig. 5) to uncover additional compounds that are not detected in mature seed. All four accessions contained a novel diglycosylated quercetin, namely quercetin-rhamnoside-glucoside, which differs from the two quercetin-glucoside-rhamnosides described above (quercetin-3-O-glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside and quercetin-hexoside-rhamnoside from Shahdara). The accumulation of this new compound could be associated with that of quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside since both compounds were lower in Cvi-0 and Shahdara compared with Col-0 and Bay-0. Additionally, quercetin-hexoside-rhamnoside 2, detected only in Shahdara, accumulated steadily during seed development but at very low levels (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Flavonoid content in developing seed from RIL parental lines: Col-0 (dark) and Cvi-0 (white) (A–D), Bay-0 (dark) and Shahdara (Sha, white) (E–H). Values represent the data obtained from one representative experiment (among experiments). All individual compounds measured with LC-MS. EC, epicatechin; G, glucoside; H, hexoside; I, isorhamnetin; K, kaempferol; Q, quercetin; B2, epicatechin dimer; R, rhamnoside.

QTL analysis uncovers 22 flavonoid QTLs, of which only one is common to the two populations

A total of 22 significant QTLs involved in flavonoid variation (termed ‘FLA’) were detected in the two RIL populations. The chromosome location of each QTL is presented in Table 1 together with its significance (LOD score), additive effects (a), and the percentage of total variance explained for the given flavonoid (R 2). These QTLs represent from 11% to 61% of the flavonoid variation. Most QTLs were detected in only one of the two mapping populations. Nevertheless, one locus involved in kaempferol changes could be common to both RIL populations (FLA5/FLA15, Table 1, located at ∼3 Mb on chromosome 5). The co-localization of QTLs for quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside and biflavonols (FLA1/FLA3 and FLA12/FLA14), PAs and quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside (FLA2/ FLA9 and FLA11/ FLA21), and PAs (FLA20/ FLA22), as well as the direction of their predicted allelic effects are consistent with the phenotypic correlations observed between some flavonoids in parental accessions and RIL populations.

Table 1.

Mapped QTLs that account for variation in flavonoid accumulation in mature seed of two RILs: Cvi-0×Col-0 and Bay-0×Shahdara

| Cvi-0×Col-0 | Col-0 (mg g−1 seed) | Cvi-0 (mg g−1 seed) | QTL name | Chr | Marker | Position [cM (Mb)] | LOD | 2a | R 2 (%) |

| Q-3-O-R | 3.24±0.15 | 0.29±0.02 | FLA1 | 1 | c1_26993 | 121.7 (28) | 4.22 | 0.64 | 25 |

| FLA2 | 2 | c2_17606 | 84.7 (18.5) | 2.76 | 0.50 | 16 | |||

| Biflavonols | 0.39±0.06 | 0.07±0.01 | FLA3 | 1 | c1_26993 | 122.7 (27) | 2.90 | 0.01 | 16 |

| K-3,7-di-O-R | 0.18±0.04 | 0.70±0.08 | FLA4 | 4 | c4_06923 | 39.4 (7.5) | 2.49 | –0.20 | 13 |

| FLA5 | 5 | c5_02900 | 12.9 (3) | 2.91 | –0.22 | 17 | |||

| FLA6 | 5 | c5_07442 | 34.0 (8) | 2.89 | –0.24 | 18 | |||

| PA soluble | 2.73±0.50 | 7.04±0.57 | FLA7 | 2 | c2_11457 | 49.0 (11.5) | 2.74 | –1.80 | 15 |

| FLA8 | 5 | c5_05319 | 24.9 (6) | 2.59 | –1.94 | 17 | |||

| PA insoluble | 7.33±0.90 | 13.68±0.51 | FLA9 | 2 | c2_17606 | 87.0 (19) | 3.13 | –2.40 | 17 |

| Bay-0×Shahdara | Bay-0 (mg g−1 seed) | Shahdara (mg g−1 seed) | Name | Chr | Marker | Position [cM (Mb)] | LOD | 2a | R 2 |

| Q-3-O-R | 5.59±0.28 | 3.94±0.25 | FLA10 | 1 | MSAT1.5 | 69.4 (23) | 2.34 | –0.70 | 11 |

| FLA11 | 4 | MSAT4.18 | 53.8 (15) | 2.52 | 0.78 | 14 | |||

| FLA12 | 5 | MSAT520037 | 69.4 (21) | 5.31 | 1.04 | 25 | |||

| Q-H-R 2 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.63±0.14 | FLA13 | 5 | NGA151 | 21.9 (7) | 14.24 | –0.56 | 61 |

| Biflavonols | 0.44±0.01 | 0.61±0.06 | FLA14 | 5 | MSAT518662 | 65.2 (19.5) | 14.07 | –0.22 | 53 |

| K-3-O-R | 0.10±0.01 | 0.17±0.01 | FLA15 | 5 | NGA249 | 12.1 (3) | 9.87 | –0.06 | 40 |

| I-R | 0.07±0.01 | 0.08±0.01 | FLA16 | 3 | MSAT305754 | 14.4 (7.5) | 3.23 | –0.02 | 19 |

| FLA17 | 4 | MSAT4.15 | 33.5 (9.4) | 2.94 | 0.02 | 14 | |||

| PA soluble | 2.87±0.22 | 3.45±0.18 | FLA18 | 1 | dCAPsAPR2 | 55.4 (18.5) | 2.39 | –1.02 | 13 |

| FLA19 | 4 | MSAT4.39 | 1.0 (0.25) | 5.41 | –1.44 | 24 | |||

| FLA20 | 5 | JV7576 | 79.0 (24) | 3.35 | 1.10 | 15 | |||

| PA insoluble | 1.74±0.11 | 1.34±0.07 | FLA21 | 4 | MSAT4.9 | 56.8 (16) | 3.25 | 0.22 | 16 |

| FLA22 | 5 | JV6162 | 74.9 (23) | 2.96 | 0.22 | 14 |

Flavonoid contents of parental lines are means of four independent experiments ±SE. Chr, chromosome; the position in centiMorgans (cM) is that from the first marker on the chromosome; 2a, the additive effect represents the mean effect in mg g−1 seed of the replacement of Cvi-0 (or Shadara, Sha) alleles by Col-0 (or Bay-0) alleles at a given QTL; R 2, percentage of the total phenotypic variance for a given flavonoid explained by the QTL. G, glucoside; h, hexoside; I, isorhamnetin; insol., insoluble; K, kaempferol; Q, quercetin; PA, proanthocyanidin; R, rhamnoside; sol., soluble.

Sixteen FLA loci are confirmed using HIF lines

HIFs, generated from the residual heterozygosity still segregating in some F6 RILs (Loudet et al., 2005), were used for further characterization (mapping and analysis) of the QTLs. Each HIF contains a short region fixed for one or other parental allele in an otherwise identical genetic background. From the 22 QTLs characterized using the two RIL populations, 16 were confirmed in HIFs that showed the expected variation (for both the direction and amplitude of the variations) (Table 2; Supplementary Figs S2, S3 at JXB online). FLA1, 3, 5, 11, 13, 15, 19, and 21 were validated with at least two independent HIF lines. Metabolite changes within the HIFs provided additional information about the flavonoid phenotypes and, in several cases, explained the occurrence of suggestive loci (1 < LOD < 2.5) detected with the RILs. This validates the quality of the data and the conservative nature of the QTL thresholds. The flavonoid contents of selected lines of the two RIL sets are given in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6.

Table 2.

Confirmation of the major QTLs detected in Cvi-0×Col-0 and Bay-0xShahdara by analysis of the phenotypes segregating in diverse heterogeneous inbred families (HIFs)

| HIF | Chromosome | Locus | Position HIFs (kb) | Q-3-O-R | Q-3-,7- di-O-R | Q-3-O-G-7-O-R | Q-H-R 2 and K-H-R 2 | Biflavonols | K-3-O-R | K-3,7-di-O-R | K-3-O-G-7-O-R | PA soluble | PA insoluble | Candidate gene (position, Mb) |

| 8HV2158HV258 | 1 | FLA1, FLA3 | 26 993–28 66728 454 | 39*26* | 48*24* | |||||||||

| 8HV3448HV218 | 2 | FLA7 | 10 25011 457–12 435 | –37** | ||||||||||

| 8HV411 | 2 | FLA2 | 17 606–18 753 | 40 | 33* | 41* | MYB12 (19.5) | |||||||

| 8HV2238HV301 | 5 | FLA5, FLA8 | 1587–4011576–5319 | −30−94 | −97**−106* | −120*−100* | −82***−15 | F3'H (2.6) | ||||||

| 33HV04433HV068 | 1 | FLA10,FLA18 | 15 927–24 37420 633–24 374 | −18*−5 | −27*−13 | TT15 (1.6) | ||||||||

| 33HV18133HV20333HV312 | 4 | FLA19 | 40789–407407–5629 | −79*−30−175*** | ||||||||||

| 33HV04833HV19133HV196 | 4 | FLA11, FLA21 | 15 790–17 26215 790–18 33615 790–17 262 | 34*29*4 | 8224*28* | 250−16 | ||||||||

| 33HV09333HV10833HV410 | 5 | FLA12,FLA14,FLA20,FLA22 | 14 766–22 52821 425–25 92520 037–21 425 | 24*15−8 | −1720–80*** | −331***2 | −3142 | DFR (17.2), TT10 (19.5), CHI (20.4) | ||||||

| 33HV15733HV21433HV21633HV340 | 5 | FLA13,FLA15 | 274–74994670–842827707498–8428 | ******−6ND | −40*−8−50**−6 | F'3H (2.6), UGT 78D3 and 2 (5.6) |

The HIF name indicates the corresponding recombinant inbred lines from the Cvi-0×Col-0 (8HV) or Bay-0×Shahdara (33HV) sets showing residual heterozygosity in the region of the QTLs. The position of segregating markers as well as some potential candidate genes included in this interval are indicated. Values for each trait indicate the change (%) in trait value when comparing the two alleles fixed in the segregating region for each HIF. Positive (versus negative) values indicate that Col or Bay allele is increasing (decreasing) the trait relative to the alternative allele; numbers in bold show significant changes between HIF alleles, and grey areas indicate when a QTL was detected (see Table 1). The same colour shows the flavonoid change corresponding to a given locus. Significance in t-test at the *5%, **1%, and *** 0.1% level. G, glucoside; h, hexoside; I, isorhamnetin; insol., insoluble; K, kaempferol; Q, quercetin; PA, proanthocyanidin; R, rhamnoside; sol., soluble. Additional information is given in Supplementary Figs S2 and S3 at JXB online.

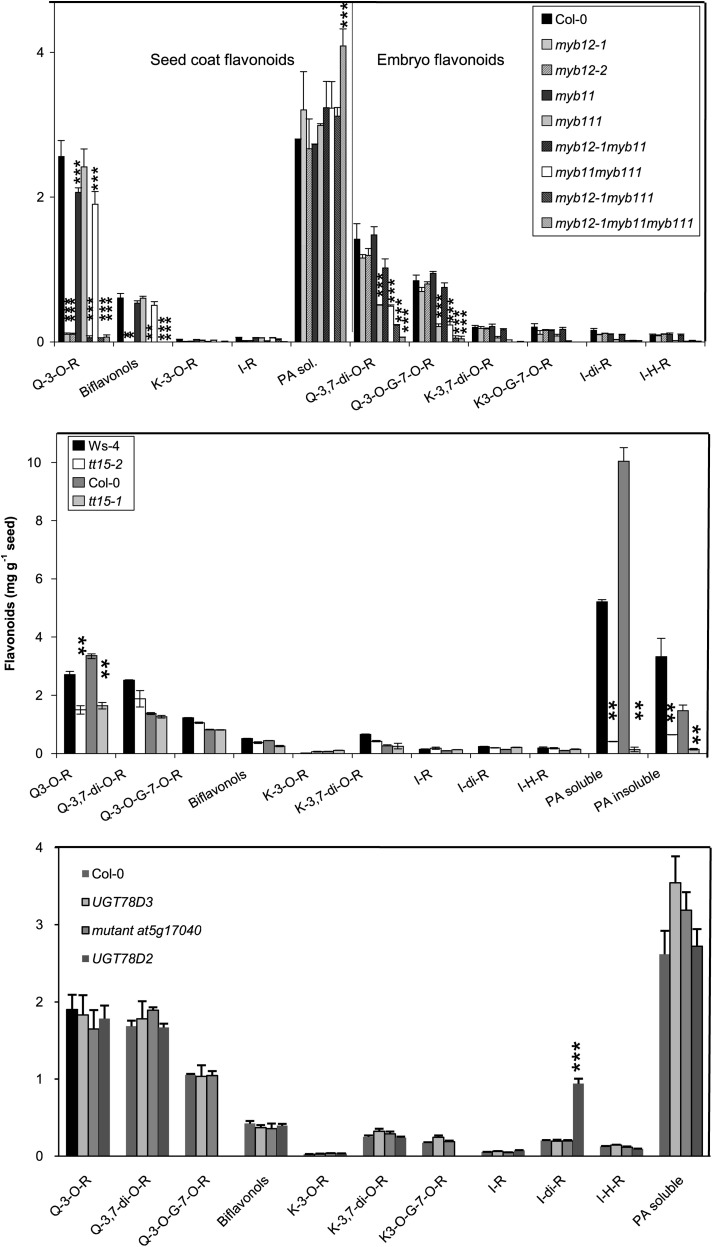

Flavonoid analysis of the myb12 mutant provides a candidate gene for the FLA2 locus and also shows that MYB12 controls flavonol accumulation in the seed coat

PFG1/MYB12, PFG2/MYB11, and PFG3/MYB111 transcriptionally control flavonol biosynthesis in root and aerial parts (Dubos et al., 2010; Stracke et al., 2010a, b), whereas the single repeat R3 MYB CPC can negatively regulate anthocyanin synthesis (Zhu et al., 2009). MYB12 and CPC genes co-localize with the FLA2 locus involved in variation of quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside content (Table 2; Supplemental Fig. S2C at JXB online). The cpc and myb12 mutants as well as single and multiple pfg mutants were analysed (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. S4). The cpc mutant (in Ws-4) did not show any significant flavonol change and is thus less likely to control the FLA2 QTL. The two myb12 mutant alleles (and multiple mutant combinations with myb12 (in the Col-0 background) were mainly affected in quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside and biflavonol accumulation. These two compounds are essentially accumulated in the seed coat and were also controlled by the FLA2 QTL (the QTL for biflavonol was only marginally suggestive with a LOD of 1.1). In addition, myb11 and myb111 mutants and double or triple mutant with myb11 and myb111 alleles had lower diglycosylated flavonol contents, that were essentially accumulated in the embryo. Interestingly, the triple mutant contained more soluble PAs (as previously observed in the fls1 mutant; Routaboul et al., 2006). This specific pattern of accumulation is consistent with a role for these closely related R2R3-MYBs in the control of flavonol accumulation through the early biosynthesis genes, in distinct parts of the seed, as previously observed in seedlings (Stracke et al., 2007, 2010a, b; Dubos et al., 2010). The changes observed in the myb12 mutant suggested that this MYB12 gene is a strong candidate for FLA2. However, the HIF at the FLA2 locus also showed modifications of diglycosylated flavonols (see Supplementary Fig. S2C), and suggestive QTLs (1 < LOD < 2) for these compounds were also detected. These results may thus reveal an additional QTL at the end of chromosome 2. Alternatively, the genetic modification at the FLA2 QTL could be more complex than a simple loss of function of the myb12 gene or the genetic background of the RILs/HIFs could modify its output through epistasis.

Fig. 6.

Flavonoid analysis of mutants for genes located near the FLA loci. G, glucoside; H, hexoside; I, isorhamnetin; K, kaempferol; Q, quercetin; PA, proanthocyanidin; R, rhamnoside; sol., soluble Significance in t-test compared with the wild type at the *5%, **1%, and ***0.1% level.

Neither ANL2 nor 72B1 glycosyltransferase are involved in PA accumulation

ANTHOCYANINLESS (ANL2) is a homeobox gene that affects anthocyanidin distribution in vegetative tissues (Kubo et al., 1999). GT72B1 is a glycosyltransferase which is the most closely related gene to UGT72L1 that is involved in epicatechin-3'-glucoside synthesis in Medicago (Pang et al., 2008). Both genes co-localized with the FLA19 QTL (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S3B at JXB online). Nevertheless, neither anl2 (Ler) nor gt72b1 (Col-0) mutants showed significant variation in seed PAs, suggesting that this variation cannot be explained by a loss-of-function allele of any of these genes in Shahdara.

78D2 glycosyltransferase are implicated in seed flavonol glucosylation

A cluster of three highly homologous glycosyltransferases, namely 78D2, 78D3, and At5g17040, that could be involved in the accumulation of a new flavonol-hexoside-rhamnoside found in Shahdara (Supplementary Fig. S5 at JXB online) is located in the region of the FLA13 locus (Supplementary Fig. S3D). Interestingly, 78D2 has been shown to be involved in anthocyanidin and flavonol glucosylation in leaves (Tohge et al., 2005; Kubo et al., 2007) and 78D3 is a flavonol arabinosyltranferase in leaves (Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2008), whereas the At5g17040 product has not yet been functionally characterized. Unfortunately, neither wild-type Col-0 nor the corresponding Col-0 mutants accumulate the additional quercetin derivative, so their involvement could not be tested (Fig. 6).

However, the 78D2 mutant still contained isorhamnetin 3-O-glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside when kaempferol or quercetin 3-O-glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside was absent. This showed that the 78D2 flavonol-3-glycosyltransferase solely catalyses the addition of a glucose moiety on kaempferol and quercetin aglycone but not on isorhamnetin. This also means that another, still unknown, glycosyltransferase transfers a glucose onto the isorhamnetins. Flavonol-arabinoside could not be detected in the seed, and the 78D3 glycosyltransferase mutant did not show any significant flavonoid changes. Other genes involved in flavonoid synthesis are located close to the FLA13 locus, such as the Bsister MADS domain TT16, the glutathione-s-transferase TT19, or chalcone synthase (CHS); however, their modifications are unlikely to produce such specific variation in a single flavonol.

HIF analysis around the loci FLA12, 14, 20, and 22 suggests a complex genetic basis for the observed variation in flavonoids

The QTLs explaining the variation of quercetin-3-0-rhamnoside, biflavonols, and soluble PA located at the end of chromosome 5 (FLA12, 14, 20 and 22) could be related to the LAC15/TT10 gene. TT10 encodes a laccase-like enzyme involved in oxidation of quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside to biflavonols and of epicatechin monomer and oligomers to oxidized procyanidins in the Arabidopsis seed coat (Pourcel et al., 2005). Indeed, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside and soluble PA contents were higher in plants fixed for the Bay-0 fixed allele [see additive effect (a) in Table 1] when biflavonols are more abundant in plants fixed for the Shahdara allele. However, HIF410, heterozygous around FLA12, only showed an accumulation of biflavonol with the Shahdara allele (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S3E at JXB online). HIF108 on the lower arm of chromosome 5 displayed higher soluble PA content (and perhaps quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside), whereas HIF093 segregated for higher quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside content with the Bay-0 allele (and possibly less biflavonols as observed for HIF410). Finally, these results suggested that the metabolic variations observed for the FLA12, 14, 20, and 22 loci are probably not explained by TT10 (LAC15) polymorphism and that biflavonol and PA variations could be controlled by different loci or are subjected to complex epistatic interactions.

tt7 and tt15 mutants display the same specific flavonoid variations predicted at the FLA5/15 and FLA10/18 loci

HIFs fixed for the Cvi-0 or Shahdara alleles at the FLA5 or FLA15 locus contained more kaempferol derivatives than those fixed for the Col-0 or Bay-0 alleles, respectively, both in seeds and in leaves (Supplementary Fig. S6 at JXB online). Around FLA5, several genes belong to the flavonoid pathway, namely F3'H (TT7), FLS, and CHS. However, CHS alteration should affect the accumulation of all flavonoids (Routaboul et al., 2006). On the same line, the selective reduction of kaempferol derivatives observed both in seeds and in leaves (see Supplementary Fig. S6 at JXB online) is unlikely to be related to a modification of the FLS enzyme that uses both dihydroquercetin and dihydrokaempferol as substrates for quercetin and kaempferol production, respectively. A putative candidate for the FLA5 and FLA15 QTL was the F3'H enzyme that converts dihydrokaempferol into dihydroquercetin, the inhibition of which produces an increase in dihydrokaempferol and a decrease in quercetin derivatives, in the tt7-4 mutant (Routaboul et al., 2006). Finally, TT15 (DeBolt et al., 2009) is involved in PA accumulation and the corresponding gene is located near FLA10 and FLA18. The two tt15 mutant alleles (in the Col-0 and Ws-4 background) had reduced amounts of quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside and PAs (Fig. 6) that could match the observed variation linked to the FLA10 and FLA18 loci, respectively.

Discussion

Large quantitative variations for flavonoids are observed in Arabidopsis seed

The seed flavonoids of 41 accessions grown in controlled conditions have been analysed to gain a first insight into the naturally occurring variation in Arabidopsis. They were chosen among 265 worldwide accessions to maximize genetic diversity (McKhann et al., 2004). These secondary metabolites, at first sight, appear to be mostly dispensable in Arabidopsis, because the CHS mutants (tt4) that lack flavonoids showed limited adverse effects (Ylstra et al., 1996; Brown et al., 2001; Buer and Muday, 2004) at least under laboratory conditions. Nevertheless, all flavonoids, flavonols, and procyanidins were detected in all the accessions that were analysed. However, large quantitative variations were observed for seed flavonoids that were mainly due to quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside and PAs that accumulate in the seed coat. For instance, in Cvi-0, the amount of quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside was ∼1% of that found in the Sp-0 accession. These quantitative variations were amplified, probably due to transgression, in the two RIL populations. Finally, the correlation between the accumulation of different flavonoids observed in accessions or in the two RIL populations were usually conserved. These observations confirmed that this metabolism is highly regulated in Arabidopsis. A notable exception to these quantitative changes are three new flavonol-hexoside-rhamnosides found in the Shahdara accession that are presumably isomers of the known flavonol-3-O-glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside accumulated in the other accessions. This result suggested that a novel and specific glycosyl transferase that catalyses the production of flavonol-hexoside-rhamnoside isomers is active in Shahdara but not in Bay-0.

A limitation of the chemical analysis using quadrupole mass spectrometry [rather than a time-of-flight (TOF); Keurentjes et al., 2006)] is that the characterization is limited to major UV-detected peaks and their derivatives, and thus minor compounds may be overlooked. Nevertheless, in Arabidopsis seedlings, a wider LC-MS untargeted screening of accumulated metabolites has been previously performed, revealing six different flavonols present in the two studied accessions (Ler and Cvi-0). Comparative analysis of seven oilseed rape genotypes (Auger et al., 2010), almond (Frison and Sporns, 2002), or fruit such as apples (Wojdylo et al., 2008), strawberries (Almeida et al., 2007), or grapes (Mane et al., 2007) also revealed essentially quantitative rather than qualitative changes.

Flavonoid accumulation is significantly controlled by a limited number of additive loci, of which only one seems common to both RIL sets

Detected QTLs account for 11–61% of the observed phenotypic variation, suggesting that flavonoid accumulation in seeds is under the genetic control of a few additive loci, similarly to anthocyanin content in grape berry (Fournier-Level et al., 2009). Most loci were validated with two or more independent HIF lines with consistent phenotypic variation related to the segregating alleles at a given locus in different genetic backgrounds. This suggests that epistasis is usually not decisive in determining seed flavonoid content in the materials and conditions used here. In contrast, analysis of isoflavones in soybean seeds revealed QTLs that account for <5% of allelic differences (Melchinger et al., 1998; Gutierrez-Gonzalez et al., 2010). In the present analyses, only one QTL could be common to the two populations. In seedlings of a Cvi-0×Ler population, a QTL for flavonol content was also detected at ∼90 cM on chromosome 1 that was not detected in the populations examined here (Keurentjes et al., 2006). This shows that the studied accessions have retained different genetic variations for shaping flavonoid accumulation (McMullen et al., 1998).

MYB12, TT15, and TT7 genes are candidates for the control of the observed natural flavonoid variations.

In total, three QTLs could be associated with a known candidate gene, MYB12 (R2R3 domain transcription factor), TT15 (UDP glucose:sterol-glucosyltransferase), and TT7 (F3'H, flavonoid-3'-hydroxylase). Further molecular characterization of these candidates, including quantitative expression analysis in HIF lines, promoter GUS reporter gene analysis, and allelic complementation will be needed to assess the mechanisms involved in natural variation.

The most promising candidate for controlling kaempferol contents (around FLA5 and FLA15) was the F3'H gene, which encodes the enzyme converting dihydrokaempferol into dihydroquercetin. Mutations at F3'H led to the accumulation of kaempferol derivatives (Kerhoas et al., 2006; Routaboul et al., 2006). Col-0 compared with Cvi-0 accessions and the two independent HIF lines fixed for the Col allele showed a similar decrease in all kaempferol derivatives, suggesting that the Cvi F3'H allele could be limiting. The FLA5 locus was mapped between 0.0 Mb and 5.3 Mb, and the FLA15 QTL around marker NGA249 at 2.8 Mb, close to the F3'H gene position (2.5 Mb). In maize, the pr1 locus was recently characterized and shown to correspond to a F3'H gene (Sharma et al., 2011). This pr1 locus was detected as a major QTL for the synthesis of C-glycosyl flavones that have insecticidal activity against corn earworm (Lee et al., 1998; Cortes-Cruz et al., 2003).

Most QTLs that have been characterized showed genetic variation in Myb factors regulating transcription. For instance, MYB12 in the present study is possibly involved in the control of flavonol content. The white grape phenotype is also caused by the insertion of a transposable element in the promoter of the VvMYBA transcription factor that regulates a VvUFGT glycosyltransferase needed for anthocyanin accumulation (Kobayashi et al., 2004; Fournier-Level et al., 2009; This et al., 2007). Elsewhere, the P1 locus in maize was governed by two duplicated Myb genes (Zhang et al., 2003). Additional experiments measuring the level of expression—rather than metabolites—in leaves detected PAP1, TTG1, and TTG2 as candidate genes in eQTL studies (Kliebenstein et al., 2006).

Most of the characterized QTLs may correspond to novel functions

Interestingly, although >60 genes involved in flavonoid metabolism have already been characterized, most of the FLA QTLs may correspond to new functions, directly (i.e. new regulators, transporters, etc.) or indirectly (i.e. developmental genes or regulatory genes of higher hierarchical order) involved in this metabolic pathway. This rather unexpected number of new loci involved in the natural variation of flavonoids may be due to the fact that QTL analysis can reveal subtle quantitative and/or additive changes that have been overlooked in previous visual screens (Trontin et al., 2011). Co-localization of different QTLs might also be a first indication that some loci have a pleiotropic effect, due to a common mechanistic basis.

FLA5 and FLA15 co-localize with Flowering Locus C that encodes a transcription factor involved in the repression of flowering (Michaels and Amasino, 1999). Nevertheless, although HIF157 segregated for both (i.e. flowering time and flavonoid) phenotypes, the HIF216 segregated only for flavonoid variations. This indicated that the flavonoid and flowering time changes around the FLC locus have independent genetic bases.

Flavonol and PAs have been proposed to be important for seed quality (i.e. germination, dormancy, and longevity; Debeaujon et al., 2000; Thompson et al., 2010). The variation in flavonoid identified in this study may thus be indirectly related to previously identified QTLs for seed quality. CDG3 and CDG6 that account for germination at low temperature in the dark in the Bay-0×Shahdara population (Meng et al., 2008) may correspond to FLA4, 17, and 19. DOG4 and 5 (Bentsink et al., 2007, 2010) that are related to a delay in germination co-localize with FLA11/21 and FLA5/15. Other loci (e.g. GW1/SSR2, 0SR1, and GW2) involved in the control of germination under moderate osmotic and salt stresses co-localize with FLA12, 17, and 21, respectively (Vallejo et al., 2010). GRS, an enhancer of abi-3-5, that affects seed longevity (Clerkx et al., 2003), co-localized with FLA19 responsible for increased PA accumulation in Sha relative to Bay-0. The flavonoid content of the two RIL sets given in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6 at JXB online will allow a finer comparison of the data with previous QTL analysis for the above flavonoid-related traits or others.

In summary, the metabolic analysis of 41 accessions and two RIL populations revealed the broad variation of seed flavonoid accumulation in Arabidopsis (and three new flavonol derivatives). The characterization of 22 QTLs in the two RIL populations dissected the genetic architecture underlying this natural variation. Most of the traits are controlled by a few additive loci with relatively broad effects. Further studies with the genotypes described here will be required to confirm candidate loci such as TT7, TT15, or MYB12. This work also paves the way for identifying novel genes that correspond to the other QTLs. More broadly, this study shows the potential of combining metabolomics and quantitative genetic for the characterization of new genes and novel markers for crop improvement that have not been revealed by previous qualitative screen.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are avilable at JXB online,

Figure S1. Natural variation of seed flavonoid content in five contrasted accessions of Arabidopsis.

Figure S2. Confirmation of the major QTLs of the recombinant population Cvi-0×Col-0 by comparison of the phenotypes of heterogeneous inbred families (HIFs).

Figure S3. Confirmation of the major QTLs of the recombinant population Bay-0 and Shahdara by comparison of the phenotypes of heterogeneous inbred families (HIFs).

Figure S4. Mutation in 72B1 and ANL2, or CPC cannot explain natural variation corresponding to QTL FLA16 and FLA2, respectively.

Figure S5. Three additional glycosylated flavonols in the Shahdara genotype.

Figure S6. QTLs 5, 13, and 15 are also confirmed in leaves using HIF lines (HIF223 and 301, HIF157 and 216, and HIF157 and 214, respectively).

Table S1. Flavonoid content (mg g−1) in accessions.

Table S2. Correlations (r and P-values) between the different flavonoids in selected accessions.

Table S3 . Correlations (r and P-values) between the different flavonoids in selected recombinant inbred lines of Cvi-0×Col-0.

Table S4 . Correlations (r and P-values) between the different flavonoids in selected recombinant inbred lines of Bay-0×Shahdara.

Table S5 . Flavonoid content in selected Cvi-0×Col-0 RIL lines.

Table S6 . Flavonoid content in selected Bay-0×Shahdara. RIL lines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Commission (FOOD-CT-2004-513960 FLAVO). We thank Alessandra Maia-Grondard and Stéphanie Boutet-Mercey from the Versailles Plant Chemistry Platform for technical help with the flavonoid analyses, Christine Camilleri and the Versailles Arabidopsis Resource Centre for the accessions, RILs, and HIF lines, Nathalie Nesi (INRA, Le Rheu) for initial characterization of the tt15-1 (COB16) mutant, Robert Edwards (Durham University, UK) for the gift of the GT72B1 mutant, Kazuki Saito (RIKEN Plant Science Center, Japan) for the 78B2 and 78B3 glycosyltransferase mutants, Hiriyoshi Kubo (Shinshu University, Japan) for the anl2 (Ler background) mutant, and Bernd Weisshaar and Ralph Stracke (Bielefeld University, Germany) for the PFG1/Myb12, PFG2/MYB11, and PFG3/MYB111 single and multiple mutants.

References

- Almeida JR, D’Amico E, Preuss A, et al. Characterization of major enzymes and genes involved in flavonoid and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis during fruit development in strawberry (Fragaria×ananassa) Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2007;465:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Blanco C, Aarts MG, Bentsink L, Keurentjes JJ, Reymond M, Vreugdenhil D, Koornneef M. What has natural variation taught us about plant development, physiology, and adaptation? The Plant Cell. 2009;21:1877–1896. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasio AE, Platt A, Horton M, Grotewold E, Scholl R, Borevitz JO, Nordborg M, Bergelson J. Source verification of mis-identified Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. The Plant Journal. 2011;67:554–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arranz S, Saura-Calixto F, Shaha S, Kroon PA. High contents of nonextractable polyphenols in fruits suggest that polyphenol contents of plant foods have been underestimated. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2009;57:7298–7730. doi: 10.1021/jf9016652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwell S, Huang YS, Vilhjálmsson BJ, et al. Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature. 2010;465:627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature08800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger B, Marnet N, Gautier V, Maia-Grondard A, Leprince F, Renard M, Guyot S, Nesi N, Routaboul JM. A detailed survey of seed coat flavonoids in developing seeds of Brassica napus L. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58:6246–6256. doi: 10.1021/jf903619v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basten CJ, Weir BS, Zeng ZB. QTL cartographer version 1.14. North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baudry A, Caboche M, Lepiniec L. TT8 controls its own expression in a feedback regulation involving TTG1 and homologous MYB and bHLH factors, allowing a strong and cell-specific accumulation of flavonoids in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 2006;46:768–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentsink L, Hanson J, Hanhart CJ, et al. Natural variation for seed dormancy in Arabidopsis is regulated by additive genetic and molecular pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2010;107:4264–4269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000410107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentsink L, Soppe W, Koornneef M. Genetic aspects of seed dormancy. In: Bradford K, Nonogaki H, editors. Seed development, dormancy and germination. Vol 27. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DE, Rashotte AM, Murphy AS, Normanly J, Tague BW, Peer WA, Taiz L, Muday GK. Flavonoids act as negative regulators of auxin transport in vivo in arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2001;126:524–535. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buendia B, Gil MI, Tudela JA, Gady AL, Medina JJ, Soria C, Lopez JM, Tomas-Barberan FA. HPLC-MS analysis of proanthocyanidin oligomers and other phenolics in 15 strawberry cultivars. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58:3916–3926. doi: 10.1021/jf9030597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buer CS, Muday GK. The transparent testa4 mutation prevents flavonoid synthesis and alters auxin transport and the response of Arabidopsis roots to gravity and light. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:1191–1205. doi: 10.1105/tpc.020313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butelli E, Titta L, Giorgio M, et al. Enrichment of tomato fruit with health-promoting anthocyanins by expression of select transcription factors. Nature Biotechnology. 2008;26:1301–1308. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas GV, Blair MW. Inheritance of seed condensed tannins and their relationship with seed-coat color and pattern genes in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2009;119:131–142. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaim AB, Borovsky Y, De Jong W, Paran I. Linkage of the A locus for the presence of anthocyanin and fs10.1, a major fruit-shape QTL in pepper. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2003;106:889–894. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill GA, Doerge RW. Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics. 1994;138:963–971. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerkx EJ, Vries HB, Ruys GJ, Groot SP, Koornneef M. Characterization of green seed, an enhancer of abi3-1 in Arabidopsis that affects seed longevity. Plant Physiology. 2003;132:1077–1084. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Cruz M, Snook M, McMullen MD. The genetic basis of C-glycosyl flavone B-ring modification in maize (Zea mays L.) silks. Genome. 2003;46:182–194. doi: 10.1139/g02-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeaujon I, Leon-Kloosterziel KM, Koornneef M. Influence of the testa on seed dormancy, germination, and longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2000;122:403–414. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBolt S, Scheible WR, Schrick K, et al. Mutations in UDP-glucose:sterol glucosyltransferase in Arabidopsis cause transparent testa phenotype and suberization defect in seeds. Plant Physiology. 2009;151:78–87. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.140582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Strack D. Phytochemistry meets genome analysis, and beyond. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:815–816. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubos C, Le Gourrierec J, Baudry A, Huep G, Lanet E, Debeaujon I, Routaboul JM, Alboresi A, Weisshaar B, Lepiniec L. MYBL2 is a new regulator of flavonoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 2008;55:940–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubos C, Stracke R, Grotewold E, Weisshaar B, Martin C, Lepiniec L. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends in Plant Science. 2010;15:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espin JC, Garcia-Conesa MT, Tomas-Barberan FA. Nutraceuticals: facts and fiction. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:2986–3008. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier-Level A, Le Cunff L, Gomez C, Doligez A, Ageorges A, Roux C, Bertrand Y, Souquet JM, Cheynier V, This P. Quantitative genetic bases of anthocyanin variation in grape (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. sativa) berry: a quantitative trait locus to quantitative trait nucleotide integrated study. Genetics. 2009;183:1127–1139. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.103929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frison S, Sporns P. Variation in the flavonol glycoside composition of almond seedcoats as determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50:6818–6822. doi: 10.1021/jf020661a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Hackett CA, Smith K, Woodhead M, Hein I, McCallum S. Mapping QTLs for developmental traits in raspberry from bud break to ripe fruit. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2009;118:1143–1155. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-0969-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Gonzalez JJ, Wu X, Gillman JD, Lee JD, Zhong R, Yu O, Shannon G, Ellersieck M, Nguyen HT, Sleper DA. Intricate environment-modulated genetic networks control isoflavone accumulation in soybean seeds. BMC Plant Biology. 2010;10:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harborne JB, Williams CA. Advances in flavonoid research since 1992. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:481–504. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassim A, Poette J, Paterson A, Zait D, McCallum S, Woodhead M, Smith K, Hackett C, Graham J. Environmental and seasonal influences on red raspberry anthocyanin antioxidant contents and identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL) Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. 2009;53:625–634. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerhoas L, Aouak D, Cingoz A, Routaboul JM, Lepiniec L, Einhorn J, Birlirakis N. Structural characterization of the major flavonoid glycosides from Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54:6603–6612. doi: 10.1021/jf061043n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keurentjes JJ, Fu J, de Vos CH, Lommen A, Hall RD, Bino RJ, van der Plas LH, Jansen RC, Vreugdenhil D, Koornneef M. The genetics of plant metabolism. Nature Genetics. 2006;38:842–849. doi: 10.1038/ng1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, West MA, van Leeuwen H, Loudet O, Doerge RW, St Clair DA. Identification of QTLs controlling gene expression networks defined a priori. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:308. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Goto-Yamamoto N, Hirochika H. Retrotransposon-induced mutations in grape skin color. Science. 2004;304:892. doi: 10.1126/science.1095011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo H, Nawa N, Lupsea SA. Anthocyaninless1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a UDP-glucose:flavonoid-3-O-glucosyltransferase. Journal of Plant Research. 2007;120:445–449. doi: 10.1007/s10265-006-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo H, Peeters AJ, Aarts MG, Pereira A, Koornneef M. ANTHOCYANINLESS2, a homeobox gene affecting anthocyanin distribution and root development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 1999;11:1217–1226. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn BM, Geisler M, Bigler L, Ringli C. Flavonols accumulate asymmetrically and affect auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2011;56:585–595. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.175976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Botstein D. Mapping mendelian factors underlying quantitative traits using RFLP linkage maps. Genetics. 1989;121:185–199. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EA, Byrne PF, McMullen MD, Snook ME, Wiseman Widstrom BRNW, Coe EH. Genetic mechanisms underlying apimaysin and maysin synthesis and corn earworm antibiosis in maize (Zea mays L.) Genetics. 1998;149:1997–2006. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.4.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GL. Condensed tannins in some forage legumes: their role in ruminant pasture bloat. Basic Life Sciences. 1992;59:915–934. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3476-1_55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I, Routaboul JM, Baudry A, Pourcel L, Nesi N, Caboche M. Genetics and biochemistry of seed flavonoids. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2006;57:405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudet O, Chaillou S, Camilleri C, Bouchez D, Daniel-Vedele F. Bay-0×Shahdara recombinant inbred line population: a powerful tool for the genetic dissection of complex traits in Arabidopsis. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;104:1173–1184. doi: 10.1007/s00122-001-0825-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudet O, Chaillou S, Merigout P, Talbotec J, Daniel-Vedele F. Quantitative trait loci analysis of nitrogen use efficiency in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2003;131:345–358. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.010785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudet O, Gaudon V, Trubuil A, Daniel-Vedele F. Quantitative trait loci controlling root growth and architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana confirmed by heterogeneous inbred family. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;110:742–753. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luceri C, Giovannelli L, Pitozzi V, Toti S, Castagnini C, Routaboul JM, Lepiniec L, Larrosa M, Dolara P. Liver and colon DNA oxidative damage and gene expression profiles of rats fed Arabidopsis thaliana mutant seeds containing contrasted flavonoids. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46:1213–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mane C, Souquet JM, Olle D, Verries C, Veran F, Mazerolles G, Cheynier V, Fulcrand H. Optimization of simultaneous flavanol, phenolic acid, and anthocyanin extraction from grapes using an experimental design: application to the characterization of champagne grape varieties. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55:7224–7233. doi: 10.1021/jf071301w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinova K, Pourcel L, Weder B, Schwarz M, Barron D, Routaboul JM, Debeaujon I, Klein M. The Arabidopsis MATE transporter TT12 acts as a vacuolar flavonoid/H+-antiporter active in proanthocyanidin-accumulating cells of the seed coat. The Plant Cell. 2007;19:2023–2038. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum S, Woodhead M, Hackett CA, Kassim A, Paterson A, Graham J. Genetic and environmental effects influencing fruit colour and QTL analysis in raspberry. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2010;121:611–627. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann HI, Camilleri C, Berard A, Bataillon T, David JL, Reboud X, Le Corre V, Caloustian C, Gut IG, Brunel D. Nested core collections maximizing genetic diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 2004;38:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen MD, Byrne PF, Snook ME, Wiseman BR, Lee EA, Widstrom NW, Coe EH. Quantitative trait loci and metabolic pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1998;95:1996–2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchinger AE, Utz HF, Schon CC. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping using different testers and independent population samples in maize reveals low power of QTL detection and large bias in estimates of QTL effects. Genetics. 1998;149:383–403. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng PH, Macquet A, Loudet O, Marion-Poll A, North HM. Analysis of natural allelic variation controlling Arabidopsis thaliana seed germinability in response to cold and dark: identification of three major quantitative trait loci. Molecular Plant. 2008;1:145–154. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JD, Snook ME, Houchins KE, Rector BG, Widstrom NW, McMullen MD. Quantitative trait loci for maysin synthesis in maize (Zea mays L.) lines selected for high silk maysin content. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2007;115:119–128. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels SD, Amasino RM. FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. The Plant Cell. 1999;11:949–956. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Olds T, Schmitt J. Genetic mechanisms and evolutionary significance of natural variation in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2006;441:947–952. doi: 10.1038/nature04878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morreel K, Goeminne G, Storme V, et al. Genetical metabolomics of flavonoid biosynthesis in Populus: a case study. The Plant Journal. 2006;47:224–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North H, Baud S, Debeaujon I, et al. Arabidopsis seed secrets unravelled after a decade of genetic and omics-driven research. The Plant Journal. 2010;61:971–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Peel GJ, Sharma SB, Tang Y, Dixon RA. A transcript profiling approach reveals an epicatechin-specific glucosyltransferase expressed in the seed coat of Medicago truncatula. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2008;105:14210–14215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805954105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer WA, Murphy AS. Flavonoids as signal molecules. In: Grotewold E, editor. The science of flavonoids. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 239–268. [Google Scholar]

- Porter LJ, Hrstich LN, Chan BG. The conversion of proanthocyanidins and prodelphinidins to cyanidins and delphinidins. Phytochemistry. 1986;25:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Pourcel L, Routaboul JM, Kerhoas L, Caboche M, Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I. TRANSPARENT TESTA10 encodes a laccase-like enzyme involved in oxidative polymerization of flavonoids in Arabidopsis seed coat. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:2966–2980. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routaboul JM, Kerhoas L, Debeaujon I, Pourcel L, Caboche M, Einhorn J, Lepiniec L. Flavonoid diversity and biosynthesis in seed of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2006;224:96–107. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KG, Swinny EE, Winefield C, Markham KR. Flavonoids and UV photoprotection in Arabidopsis mutants. Zeitschrift Naturforschung C. 2001;56:745–754. doi: 10.1515/znc-2001-9-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Matsuda F. Metabolomics for functional genomics, systems biology, and biotechnology. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2010;61:463–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Cortes-Cruz M, Ahern K, McMullen M, Brutnell TP, Chopra S. Identification of the Pr1 gene product completes the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway of maize. Genetics. 2010;110:126–136. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.126136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, Loudet O, Durand S, Berard A, Brunel D, Sennesal FX, Durand-Tardif M, Pelletier G, Camilleri C. Quantitative trait loci mapping in five new large recombinant inbred line populations of Arabidopsis thaliana genotyped with consensus single-nucleotide polymorphism markers. Genetics. 2008;178:2253–2264. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C, Koornneef M. A fortunate choice: the history of Arabidopsis as a model plant. Nature Review Genetics. 2002;3:883–889. doi: 10.1038/nrg927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R, Favory JJ, Gruber H, Bartelniewoehner L, Bartels S, Binkert M, Funk M, Weisshaar B, Ulm R. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor HY5 regulates expression of the PFG1/MYB12 gene in response to light and ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2010a;33:88–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R, Ishihara H, Huep G, Barsch A, Mehrtens F, Niehaus K, Weisshaar B. Differential regulation of closely related R2R3-MYB transcription factors controls flavonol accumulation in different parts of the Arabidopsis thaliana seedling. The Plant Journal. 2007;50:660–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R, Jahns O, Keck M, Tohge T, Niehaus K, Fernie AR, Weisshaar B. Analysis of production of flavonol glycosides-dependent flavonol glycoside accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana plants reveals MYB11-, MYB12- and MYB111-independent flavonol glycoside accumulation. New Phytologist. 2010b;188:985–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LP, Grotewold E. Flavonoids as developmental regulators. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2005;8:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- This P, Lacombe T, Cadle-Davidson M, Owens CL. Wine grape (Vitis vinifera L.) color associates with allelic variation in the domestication gene VvmybA1. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2007;114:723–730. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EP, Wilkins C, Demidchik V, Davies JM, Glover BJ. An Arabidopsis flavonoid transporter is required for anther dehiscence and pollen development. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:439–451. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T, Nishiyama Y, Hirai MY, et al. Functional genomics by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing an MYB transcription factor. The Plant Journal. 2005;42:218–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trontin C, Tisné S, Bach L, Loudet O. What does Arabidopsis natural variation teach us (and does not teach us) about adaptation in plants? Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2011;14:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo AJ, Yanovsky MJ, Botto JF. Germination variation in Arabidopsis thaliana accessions under moderate osmotic and salt stresses. Anals of Botany. 2010;106:833–842. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veit M, Pauli GF. Major flavonoids from Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Journal of Natural Products. 1999;62:1301–1303. doi: 10.1021/np990080o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waghorn GC, McNabb WC. Consequences of plant phenolic compounds for productivity and health of ruminants. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2003;62:383–392. doi: 10.1079/pns2003245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CA, Grayer RJ. Anthocyanins and other flavonoids. Natural Products Reports. 2004;21:539–573. doi: 10.1039/b311404j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkel-Shirley B. Flavonoid biosynthesis. A colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology. Plant Physiology. 2001;126:485–493. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkel-Shirley B. Biosynthesis of flavonoids and effects of stress. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2002;5:218–223. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojdylo A, Oszmianski J, Laskowski P. Polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of new and old apple varieties. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56:6520–6530. doi: 10.1021/jf800510j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylstra B, Muskens M, Van Tunen AJ. Flavonols are not essential for fertilization in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Molecular Biology. 1996;32:1155–1158. doi: 10.1007/BF00041399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Tohge T, Matsuda F, Nakabayashi R, Takayama H, Niida R, Watanabe-Takahashi A, Inoue E, Saito K. Comprehensive flavonol profiling and transcriptome coexpression analysis leading to decoding gene–metabolite correlations in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2008;20:2160–2176. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Wang Y, Zhang J, Maddock S, Snook M, Peterson T. A maize QTL for silk maysin levels contains duplicated Myb-homologous genes which jointly regulate flavone biosynthesis. Plant Molecular Biology. 2003;52:1–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1023942819106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu HF, Fitzsimmons K, Khandelwal A, Kranz RG. CPC, a single-repeat R3 MYB, is a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant. 2009;2:790–802. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.