Abstract

Potential roles for lactate in the energetics of brain activation have changed radically during the past three decades, shifting from waste product to supplemental fuel and signaling molecule. Current models for lactate transport and metabolism involving cellular responses to excitatory neurotransmission are highly debated, owing, in part, to discordant results obtained in different experimental systems and conditions. Major conclusions drawn from tabular data summarizing results obtained in many laboratories are as follows: Glutamate-stimulated glycolysis is not an inherent property of all astrocyte cultures. Synaptosomes from the adult brain and many preparations of cultured neurons have high capacities to increase glucose transport, glycolysis, and glucose-supported respiration, and pathway rates are stimulated by glutamate and compounds that enhance metabolic demand. Lactate accumulation in activated tissue is a minor fraction of glucose metabolized and does not reflect pathway fluxes. Brain activation in subjects with low plasma lactate causes outward, brain-to-blood lactate gradients, and lactate is quickly released in substantial amounts. Lactate utilization by the adult brain increases during lactate infusions and strenuous exercise that markedly increase blood lactate levels. Lactate can be an ‘opportunistic', glucose-sparing substrate when present in high amounts, but most evidence supports glucose as the major fuel for normal, activated brain.

Keywords: astrocyte, brain activation, glucose, lactate shuttling, metabolism, neuron

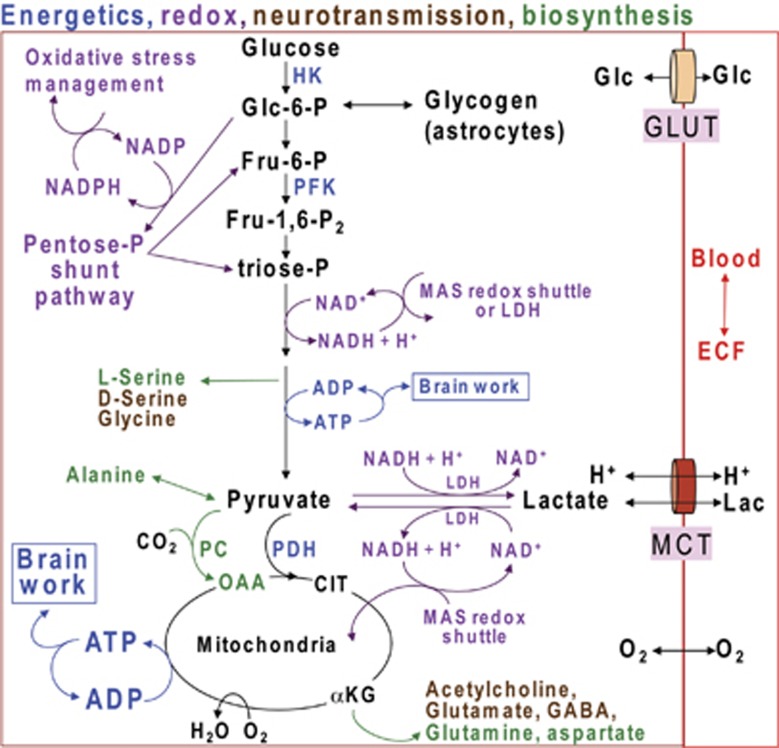

Glucose is the major fuel for the brain, and its metabolism by different pathways has important functions related to energetics, neurotransmission, oxidation–reduction (redox) reactions, and biosynthesis of essential brain components (Figure 1). For many decades, lactate production in the brain was viewed as a consequence of inadequate oxygen delivery, disruption of oxidative metabolism, or mismatch between glycolytic and oxidative rates (Siesjö, 1978), but more recently, the conceptual role of lactate metabolism and function in the normal brain have undergone major changes, shifting from developmental fuel and glycolytic waste product to include its use as a supplemental fuel and signaling molecule. Starting in the 1970s to 1980s studies carried out in different laboratories with diverse experimental interests related to brain function brought attention to upregulation of glycolysis, lactate production, lactate release into the blood, the possibility of lactate shuttling among cell types within the brain, lactate fueling adult brain during exercise, and roles of lactate in the regulation of blood flow; some of these topics are controversial and highly debated. The experimental paradigm and physiologic status of subjects are critical for interpretation of data, and this review first presents a brief historical overview of studies related to brain lactate transport and metabolism, then compares sets of data to provide a perspective and context within which the consistency of similar experiments and their in vivo relevance can be compared and assessed. Space and reference limitations prevent citation of many important studies, and selected initial reports and reviews for specific topics are cited.

Figure 1.

Multifunctional roles of glucose metabolism. Color coding denotes different functional roles of pathways of glucose metabolism. Glucose (Glc) and lactate (Lac) plus H+ are transported into brain cells from blood or extracellular fluid (ECF) by equilibrative transporters, GLUTs and MCTs (monocarboxylic acid transporters), respectively, whereas oxygen diffuses into brain cells. Energetics (blue) involves ATP production by the glycolytic (glucose to pyruvate; Fru=fructose) and oxidative (pyruvate to CO2 + H2O) pathways. Glycolytic rate is modulated by regulation of hexokinase (HK), phosphofructokinase (PFK), and other enzymes. Glucose is stored as glycogen, mainly in astrocytes. Pyruvate enters the oxidative pathway of the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle, with formation of 3 CO2 and regeneration of oxaloacetate (OAA). Neurotransmitters and neuromodulators (brown) are synthesized through the glycolytic and oxidative pathways. Other biosynthetic pathways produce amino acids (green) and sugars (not shown) used to synthesize complex carbohydrates for glycoproteins and glycolipids. Net synthesis of a ‘new' four- or five-carbon compound (aspartate, glutamate, glutamine, GABA) requires pyruvate carboxylase (PC), which is only located in astrocytes. CO2 fixation by PC converts pyruvate to OAA. OAA is transaminated to form aspartate or it condenses with acetyl CoA derived from a second pyruvate molecule by the action of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) to form citrate (CIT). Decarboxylation of this ‘new' six-carbon compound forms α-ketoglutarate (αKG) that can be converted to a new molecule of glutamate, glutamine, and GABA. These compounds can also incorporate label from labeled glucose in neurons and astrocytes by means of reversible exchange reactions, but their net synthesis requires the astrocytic PC reaction. Acetylcholine is also derived from glucose through citrate in neurons. Entry of glucose-6-P into the pentose phosphate shunt pathway (purple) results in oxidative decarboxylation of carbon one of glucose and generates NADPH, which is used to detoxify reactive species that can cause oxidative stress. The nonoxidative branch of pentose shunt produces fructose-6-phosphate (Fru-6-P) and triose-P that reenter the glycolytic pathway; nucleotide precursors are also generated by the pentose shunt pathway. NAD+ is required for glycolysis, and it is regenerated from NADH by the malate–aspartate shuttle (MAS) or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (purple). The MAS redox shuttle transfers reducing equivalents from the cytosol to the mitochondria and is required to generate pyruvate for oxidation by the tricarboxylic acid cycle; it is also required for oxidative metabolism of lactate. Regeneration of NAD+ by LDH removes pyruvate from the oxidative pathway.

Brief Thematic and Historical Perspective of Brain Lactate Metabolism and Trafficking

Compartmentation of Lactate Metabolism in the Brain

During the 1960 to 1970s, in vivo studies of precursors of brain amino acids revealed compartmentation of metabolism in the brain, with identification of different precursors that preferentially labeled the large (neuronal) glutamate pool and the small (astrocytic) glutamate pool that is the precursor for glutamine; pool labeling assignments were based on the ratio of the specific activity of purified glutamate to that of glutamine (reviewed in the volume edited by Balázs and Cremer (1972)). Early studies have shown that glucose (Cremer, 1964) and lactate labeled the large glutamate pool, whereas butyrate and acetate labeled the small pool (O'Neal and Koeppe, 1966). However, lactate is oxidized by cultured cortical and cerebellar neurons and astrocytes (Dienel and Hertz (2001) and references cited therein) and by both neurons and astrocytes in vivo (Zielke et al, 2007; Zielke et al, 2009).

Rapid Lactate Release from the Brain into the Blood

Hawkins et al (1973) showed that an ammonia injection increases the rate of cerebral glucose utilization (CMRglc) and oxygen consumption (CMRO2) in the rat brain and increases lactate release to blood from 3.5% (as glucose equivalents) of glucose uptake at rest to 15% after ammonia. The brain lactate level was less than that in blood, suggesting sites with locally high lactate levels from which lactate diffused into blood. In humans, positron emission tomographic imaging studies using [11C]glucose detected release of 11C-acidic metabolites into blood within 4 minutes (Blomqvist et al, 1990). During spreading cortical depression, release of 14C-lactate was detectable within 2 minutes after pulse labeling of the rat brain with [6-14C]glucose; maximal lactate efflux equaled 20% of glucose uptake, and [14C]lactate accounted for nearly all of the 14C discharged into the blood (Cruz et al, 1999). In humans given stressful mental testing, lactate release corresponded to 7% of glucose uptake (Madsen et al, 1995). The above studies show that the resting brain also releases small amounts of lactate (∼3% to 7% of glucose uptake), and that lactate efflux quickly increases by 3- to 4-fold during activation. A recent positron emission tomographic study in a resting young adult human brain revealed regional heterogeneity in the mismatch between local rates of glucose and oxygen utilization (Vaishnavi et al, 2010), suggesting that lactate release from various brain structures probably differs under basal conditions.

Lactate Release from Brain Cells

Lactate is released in larger quantities from ‘resting' cultured astrocytes than neurons, but both cell types produce lactate under various conditions (Walz and Mukerji, 1988). Dringen et al (1993) discovered that lactate, not glucose, is released from cultured astrocytes during glycogenolysis, and suggested that lactate may function as fuel for neighboring cells. These and related in vitro studies underlie the widely held notion that astrocytes may be the major source of brain lactate, but the cellular origin and cellular metabolic fate of lactate in vivo remain to be experimentally established.

Underestimation of Metabolic Activation with Labeled Glucose and Lactate Release from the Brain

Functional metabolic brain imaging studies in conscious rats (Collins et al, 1987; Ackermann and Lear, 1989; Adachi et al, 1995; Cruz et al, 2007) and humans (Blomqvist et al, 1990) found that the magnitude of increased CMRglc evoked by sensory stimulation, seizures, spreading depression, and voluntary finger tapping was greatly underestimated (by approximately ⩾50%) with labeled glucose compared with labeled deoxyglucose, suggesting upregulation of glycolysis and rapid lactate release (Collins et al, 1987; Lear and Ackermann, 1989; Lear, 1990). Studies that our laboratory designed to understand the neurobiology underlying the above discrepant results obtained with glucose and deoxyglucose showed that brain lactate is quickly labeled by blood glucose, lactate is readily diffusible, and rapid lactate efflux to the blood causes loss of labeled products from the brain (Adachi et al, 1995; Cruz et al, 1999; Dienel and Cruz, 2009). Focal label retention in activated structures is enhanced by blockade of lactate transporters and astrocytic gap junctions (Cruz et al, 2007), and astrocytes have a much higher rate and capacity for lactate uptake from extracellular fluid and for dispersion within the astrocytic syncytium compared with lactate shuttling from astrocytes to neurons (Gandhi et al, 2009). Most lactate derived from glucose microinfused into interstitial fluid is not locally oxidized, and extracellular metabolites are released through perivascular flow into the lymphatic drainage systems (Ball et al, 2010). Taken together, these findings indicate that increased glycolysis during activation is associated with substantial loss of lactate from the brain through vascular and perivascular drainage systems within 5 minutes in normal subjects with low blood lactate levels (∼0.5 to 1 mmol/L) and modest (∼2-fold) or large (>3- to 8-fold) increases in brain lactate level.

‘Uncoupling' of Cerebral Blood Flow, Oxygen Consumption (CMRO2), and CMRglc During Sensory and Mental Stimulation

In the resting brain, nearly all of the glucose metabolized is oxidized, and many, but not all, studies report that the resting CMRO2/CMRglc ratio is close to the theoretical maximum of 6.0 (i.e., 6 O2 are required to oxidize 1 glucose). However, during activation, disproportionately larger increases in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and CMRglc compared with CMRO2 were reported by Fox and Raichle (1986) and Fox et al (1988), and confirmed in humans (Madsen et al, 1995) and rats (Madsen et al, 1999). The CMRO2/CMRglc ratio falls in most, but not all, activation studies by a variable magnitude, showing that nonoxidative metabolism usually increases much more than oxidative metabolism, which can be either unchanged or increased somewhat (∼10% to 25%), depending on the paradigm and brain structures involved (Dienel and Cruz (2008) and cited references). The basis for this phenomenon (sometimes called aerobic glycolysis) remains to be elucidated, and it contrasts the brain's capacity to increase CMRO2 by 2- to 3-fold during seizures and maintain the increase for 2 hours (Meldrum and Nilsson, 1976; Borgström et al, 1976). The activation-induced CMRO2–CMRglc mismatch is consistent with increased glycolysis without local oxidation of the lactate equivalents generated.

Lactate and Neuronal Function in Brain Slices

Levels of lactate transporters at the blood–brain barrier and enzymes that metabolize ketone bodies decrease drastically after weaning (Cremer, 1982; Vannucci and Simpson, 2003), and blood lactate and ketones are not major fuels for the adult brain unless their concentrations increase markedly. However, during hypoxia/ischemia, glucose/glycogen-derived lactate accumulates in brain tissue. The notion that lactate may ‘jump start' neuronal recovery after restoration of blood flow and oxygen delivery was proposed after the discovery that lactate supported electrically evoked action potentials in brain slices (Schurr et al, 1988; Schurr, 2006). However, other investigators previously found that lactate and other alternative substrates cannot substitute for glucose, and evoked action potentials fail even though ATP levels are maintained (see Figure 4 and related text in Dienel and Hertz (2005)). The ability of lactate to support evoked action potentials depends on the speed of slice preparation and other technical issues that are not fully understood (Okada and Lipton, 2007). Moreover, lactate cannot prevent anoxic depolarization in slices from P12 and P28 rats when glycolysis is completely inhibited (Allen et al (2005) and discussion therein). These findings indicate that lactate oxidation can support cellular functions or contribute to brain energetics under specific experimental conditions. However, glycolytic metabolism of glucose satisfies critical functions (Figure 1) that cannot be fulfilled by lactate or mitochondrially generated ATP, and maintenance of specific brain function requires glucose, not lactate, under many experimental conditions.

Extracellular Lactate Levels Increase During Activating and Pathophysiologic Conditions

Microdialysis (Korf and de Boer, 1990) and microelectrode (Hu and Wilson, 1997a, ) technology enabled monitoring of extracellular glucose and lactate levels. Many investigators have reported ∼2-fold increases in extracellular lactate levels during various behaviors or stresses, and these findings are often used to support the idea that glycolytic flux increases. However, lactate concentration changes must be interpreted with caution (Veech, 1991) because metabolite concentration is the net result of input to and output from a pool, and it does not report flux through the pool.

Lactate and Excitatory Neurotransmission

In 1994, Pellerin and Magistretti (1994) reported that glutamate stimulated CMRglc and lactate release in cultured astrocytes, and proposed that glutamate uptake stimulates astrocytic glycolysis and the lactate serves as fuel for nearby neurons. This concept, the astrocyte–neuron lactate shuttle hypothesis, posits that (1) the two ATP required by astrocytes to dispose of the Na+ taken up with glutamate and to convert glutamate to glutamine are satisfied by glycolysis and (2) there is a predominant cellular compartmentation of glycolytic and oxidative metabolism in astrocytes and neurons, respectively, during excitatory neurotransmission, with lactate shuttling to neurons and neuronal oxidation of lactate as major fuel (Hyder et al, 2006; Pellerin et al, 2007; Pellerin, 2008; Magistretti, 2009; Jolivet et al, 2010).

Cerdán et al (2006) proposed a different mechanism and role for astrocyte–neuron lactate trafficking, i.e., redox shuttling in which reducing equivalents are hypothesized to be transferred from astrocytes to neurons. In this model, lactate release from astrocytes and its uptake and oxidation to pyruvate in neurons transfers NADH to neurons. However, the pyruvate is not retained and oxidized in the neurons. Instead, pyruvate is released, taken up by astrocytes, and reduced to lactate to regenerate NAD+ in the astrocyte. This mechanism could thereby support glycolytic metabolism in astrocytes by means of a transcellular redox shuttle cycle instead of the intracellular, malate–aspartate shuttle (MAS) that transfers reducing equivalents from cytoplasmic NADH to the mitochondria for oxidation and ATP generation (Figure 1).

Discordant metabolic effects of glutamate on cultured astrocytes, complex biochemical and cellular responses to activation, oxidation of lactate by both neurons and astrocytes in vitro and in vivo, and rapid, substantial lactate release from the brain during in vivo activation have been cited as evidence against the brain's use of lactate as a major fuel during normal adult brain activation under physiologic conditions (Hertz et al, 1998, 2004, 2007; Chih et al, 2001; Chih and Roberts, 2003; Dienel and Cruz, 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008; Dienel and Hertz, 2001, 2005; Mangia et al, 2009a; Zielke et al, 2009). In addition, major metabolic responses to activation of the cerebellum in vivo are linked to postsynaptic events, with no detectable effect of blockade of astrocytic glutamate uptake on evoked metabolic activity. The AMPA (2-amino-3-(5-methyl-3-oxo-1,2- oxazol-4-yl)propanoic acid) receptor blockade, not astrocytic glutamate transport inhibition, eliminates stimulus-induced increases in extracellular lactate level, CMRglc, CMRO2, and CBF in the cerebellum in vivo (Caesar et al, 2008), separating metabolic activation from glutamate transport.

A contrasting transport-metabolism model that emphasizes concentrations and kinetic properties of cellular glucose and lactate transporters predicts that neurons take up most glucose during activation and release lactate to astrocytes, i.e., a neuron-to-astrocyte lactate shuttle (Simpson et al, 2007; Mangia et al, 2009b, 2011; DiNuzzo et al, 2010a, ). A mechanism that may explain, in part, increased neuronal lactate production during activation comes from in vitro studies of regulation of mitochondrial metabolism by calcium (Bak et al, 2009; Contreras and Satrústegui, 2009). In brief, extramitochondrial Ca2+ binds to the aspartate–glutamate carrier (aralar) that is predominant in neurons and a component of the MAS. The MAS transfers reducing equivalents from cytoplasmic NADH to the mitochondria and regenerates NAD+ to maintain glycolytic flux and produce pyruvate for oxidative metabolism (Figure 1). Small [Ca2+] signals stimulate MAS activity, whereas large [Ca2+] signals arising from Ca2+ entry into the mitochondria via the Ca2+ uniporter activate pyruvate, α-ketoglutarate, and isocitrate dehydrogenases and increase tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle flux (Pardo et al (2006) and cited references). However, Ca2+ activation of the MAS and TCA cycle are competitive, with preferential retention of α-ketoglutarate in the TCA cycle, thereby limiting its role in the MAS; low MAS activity would cause lactate production to increase in activated neurons (Bak et al, 2009; Contreras and Satrústegui, 2009) and it would impair neuronal lactate oxidation (Figure 1).

To sum up, the role of lactate during activation has been a difficult, controversial topic owing, in part, to technical difficulties associated with comprehensive, quantitative in vivo assays of metabolism and metabolite trafficking and to temporal-spatial limitations of current methodology. Brain lactate metabolism is complex and in vivo studies are required to establish its role during brain activation.

Lactate is Fuel for the Human Brain when Exercise Increases Blood Lactate Levels

During strenuous physical work, human plasma lactate increases from ∼0.5 to 1 mmol/L to 20 to 30 mmol/L, and whole-brain studies of metabolic activity during exercise reveal progressive increases in brain lactate uptake and metabolism as work load and plasma lactate levels increase (Ide et al, 1999, 2000). Blood lactate is oxidized in the brain and more glucose is also consumed during exhaustive exercise, but there is also a decline in the oxygen/(glucose+½ lactate) utilization ratio from ∼6 to as low as 1.7, and there is a large, unexplained excess carbohydrate taken up into brain that is not accounted for by oxidative metabolism or tissue metabolite accumulation or release (Dalsgaard, 2006; Quistorff et al, 2008; van Hall et al, 2009).

Lactate can Stimulate Vasodilation

Gap junction-coupled astrocytes can avidly take up lactate from extracellular fluid and are poised to discharge it from their endfeet into perivascular fluid where pulsatile pressure can drive the lactate along the vasculature (Gandhi et al (2009); Ball et al (2007, 2010) and cited references). Several studies have reported that lactate increases vasodilation by different mechanisms (Hein et al, 2006; Yamanishi et al, 2006; Gordon et al, 2008), and continuous lactate release from the activated brain may serve a signaling function to increase blood flow and fuel delivery to the brain. As glucose delivery to the brain exceeds demand for glucose over a wide range of CMRglc (Cremer et al, 1983; Hargreaves et al, 1986), lactate release and its use as a blood flow regulator need not be a ‘waste' of fuel, because lactate can be used by peripheral tissues as fuel or as a gluconeogenic substrate.

Summary

Evidence for increased glycolysis and lactate release from the brain to the blood during brain activation in normal subjects with low plasma glucose levels during normal and pathophysiological conditions has accumulated since the 1970s. Strenuous exercise increases blood lactate levels and floods the brain with an alternative substrate that is oxidized in increased amounts. Flooding experiments in cultured cells and brain slices also show lactate oxidation and reduced glucose utilization, and these assays mimic strenuous exercise, not sedentary subjects. Lactate is generated and oxidized by neurons and astrocytes, but the magnitude and direction of cell-to-cell lactate shuttling coupled to its oxidation or release from the brain remains to be established in vivo. Continuous lactate release may serve an important CBF-regulatory function.

Aspects of Experimental Systems Relevant to Interpretation of Lactate as Brain Fuel

The lactate literature is very extensive and involves many different experimental systems. Experiments often focus on specific aspects of a more complex system, and comparative data interpretation requires a broad perspective, context, and attention to experimental details.

Properties and Physiology of the Experimental System

Assessment of all studies must take into account age, nutritional status, anesthesia, and physiologic state. Brain growth and metabolic and functional development have enormous spurts between 10 and 21 days, with slower increases thereafter (Baquer et al, 1975). Particular care must be taken when translating findings obtained in cells or tissue from prenatal, early postnatal, and weanling subjects to the adult brain owing to downregulation of specific transport and metabolic activities after weaning and to continued brain grown for weeks after weaning. Brain slices obtained from immature or adult brains have cell–cell interactions acquired through normal development, but they are damaged by preparative procedures and postmortem ischemia and have lower metabolic rates than in vivo owing to deafferentation. Slices have no blood flow and are dependent on diffusion of fuel and oxygen from the incubation medium. Cultured cells derived from embryonic and newborn animals have very low levels of metabolic enzymes when the tissue is harvested, and transport and metabolic capability may be geared to the early prenatal or postnatal and suckling stages of development, i.e., for use of lactate and ketone bodies more than glucose. Different cell types and brain regions mature at different ages, and neurons that survive tissue dissociation and multiply in culture are considered to be recently postmitotic neurons that have not developed a lot of processes. Cerebral cortical neuronal cultures obtained from ∼15-day-old embryos are used as a model system for GABAergic neurons (culture conditions apparently select against glutamatergic neurons; Yu et al (1984)), and cerebellar granule neurons obtained from ∼7-day-old postnatal rodents are used as a model system for glutamatergic neurons (Schousboe et al (1985); Hertz et al (1988) and cited references). Harvest age, culture duration, conditions, medium composition, and cellular development during culturing influence characteristics of cultures (Hertz et al (1998), Hertz (2004) and cited references), as well as any acquired pathophysiology during culturing (e.g., 15 to 30 mmol/L glucose causes diabetic complications; Gandhi et al (2010)). The capacity to use glucose or lactate by cultured astrocytes and neurons grown for <2 weeks in vitro need not be equivalent to the adult brain.

Lactate Concentration and Utilization Rates

Brain lactate concentration in normal, carefully handled resting subjects is ∼0.2 to 1 μmol/g, and it approximately doubles during activation. The quantity of lactate that accumulates in the brain during an activation episode is <5% of the pyruvate formed from glucose (Dienel et al, 2007a). The lactate level in a normal resting brain is linearly related to that of pyruvate (Dienel and Cruz, 2008), and its increase during activation probably reflects an increase in pyruvate concentration. The arterial plasma lactate level in resting subjects is often lower than that in the brain, and it increases with physical activity. However, even during exhaustive exercise, human brain lactate does not accumulate above ∼1 mmol/L (Quistorff et al, 2008). Large increases in brain lactate level are abnormal (Siesjö, 1978), and metabolic assays using high, flooding doses of lactate (greater than ∼3 mmol/L) mimic brain pathology or physically active subjects.

Fractional Contribution of Lactate to Overall Metabolism

Lactate is sometimes called a ‘preferred substrate' compared with glucose. Within this context, the notion of ‘equi-caloric' concentrations of glucose and lactate (1 glucose=2 lactate) is sometimes used as a framework for testing relative concentrations of each substrate. However, this is a specious concept because glycolysis is highly regulated (by activation and inhibition) at many steps, whereas lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-mediated formation of pyruvate from lactate is an equilibrative reaction (lactate + NAD+ ↔ pyruvate + NADH + H+) that is not governed by metabolic demand nor fine-tuned by intricate regulation. Lactate concentration is influenced by pyruvate level, pH, NADH/NAD ratio, and other reactions coupled to the NADH–NAD redox system (Veech, 1991). Lactate cannot fulfill many functions of glucose metabolism (Figure 1) and elevated concentrations of lactate reduce glucose utilization in a concentration-dependent manner in cultured astrocytes (Swanson and Benington, 1996; Rodrigues et al, 2009), cultured neurons (Bouzier-Sore et al, 2006), and brain in vivo (Wyss et al, 2011). This feature of lactate utilization is consistent with its use as an opportunistic, glucose-sparing substrate when available in blood in high amounts, as during intense exercise.

Transport of glucose and of lactate plus H+ is equilibrative, and unidirectional uptake rates will increase with substrate concentration until the transporters are saturated. Brain glucose levels are typically ∼20% to 25% that of arterial plasma, and once hexokinase is saturated (its Km for glucose is ∼0.05 mmol/L), further increases in glucose concentration do not increase glucose utilization rate in the rat brain in vivo (Orzi et al, 1988) or in isolated synaptosomes (Bradford et al, 1978) owing to feedback-regulatory mechanisms that coordinate CMRglc with ATP demand and ADP availability as cosubstrate for reactions that produce ATP. In contrast, lactate-pyruvate interconversion is driven by concentration gradients. The higher the lactate level, the more pyruvate plus NADH + H+ will be generated until inhibitory levels of pyruvate are reached or MAS activity to regenerate cytoplasmic NAD+ becomes limiting (Figure 1). It must be noted that the actual metabolic situation in brain tissue is probably much more complex because of compartmentation of intracellular pyruvate/lactate pools and differential fates of pyruvate in different pools that are not considered in this simplified discussion (Cruz et al, 2001; Rodrigues et al, 2009). Utilization of pyruvate derived from either substrate by the oxidative TCA cycle pathways would then be governed by the same regulatory steps that modulate the rates of the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction, TCA cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation.

Different monocarboxylic acid transporter (MCT) and LDH isoforms are present in neurons and astrocytes. These isoforms can influence the concentration dependence of the proportion of lactate taken up and metabolized by either cell type because of differences in their Kms, Vmaxs, and LDH inhibition by pyruvate, but do not govern the direction of lactate flow (see discussions by Veech (1991), Chih et al (2001), Chih and Roberts (2003), Gandhi et al (2009), and Quistorff and Grunnet (2011a, 2011b). Lactate transport and its oxidation to pyruvate generate intracellular H+, and, depending on buffering capacity, reduced intracellular pH may inhibit phosphofructokinase and glycolytic rate. Depletion of NAD+ by the LDH reaction will reduce its availability for glycolysis (Figure 1). Metabolites generated by lactate oxidation (citrate, ATP, and other TCA cycle compounds) can inhibit brain phosphofructokinase in a very complex manner that depends on the levels of many modulators of this enzyme and pH (Passonneau and Lowry, 1963; Lowry and Passonneau, 1966). Of interest is the lack of effect of glutamate (Passonneau and Lowry, 1963), 10 to 100 mmol/L glucose, 2 mmol/L creatine, 0.2 mmol/L pyruvate, 3 mmol/L lactate, 0.06 mmol/L acetyl CoA, and 0.3 mmol/L α-ketoglutarate on the activity of brain phosphofructokinase (Krzanowski and Matschinsky, 1969). In contrast, 5 to 10 mmol/L lactate inhibits skeletal muscle phosphofructokinase (Costa Leite et al, 2007), suggesting that there may be different regulatory mechanisms involving lactate in the muscle compared with the brain, as observed for TCA cycle intermediates that can modulate phosphofructokinase from the rat brain but not the rat heart (Passonneau and Lowry, 1963).

Many investigators have used high-lactate flooding experiments, and a critical issue that is not always addressed in competitive substrate assays is dilution of labeled pyruvate when labeled glucose or lactate is the tracer. This is important because pyruvate concentration is 10- to 13-fold lower than lactate owing to the LDH equilibrium constant. To interpret inhibition of metabolism of pyruvate derived from glucose compared with that derived from lactate, the specific activity or fractional enrichment of pyruvate (i.e., the ratio of the labeled to unlabeled pyruvate) must be determined and used to calculate the effects of different concentrations of lactate or glucose added to the assay. For example, if labeled glucose generates pyruvate with a specific activity of 1, and addition of unlabeled lactate reduces pyruvate specific activity to 0.5 and the amount of glucose oxidized by 50%, then lactate had no effect on glucose oxidation. In other words, lactate only depressed pyruvate specific activity and, therefore, reduced the fraction of labeled pyruvate that entered the oxidative pathway. Increasing the level of unlabeled lactate will overwhelm labeling of pyruvate by glucose, whereas increasing glucose concentration will not have much effect on pyruvate labeled by lactate because of regulated metabolism of glucose.

Summary

High levels of extracellular lactate can ‘flood the system' and provide a nonregulated source of pyruvate, thereby influencing glucose utilization. However, a ‘preference' for lactate that arises from fine-tuned regulation glycolytic enzyme activities by many metabolites is not the same as preferring one of different candies of identical composition and caloric content. If brain-derived lactate was highly ‘preferred' over blood-borne glucose as fuel, why would any lactate be released from the brain? Other factors must be involved in substrate utilization. The apparent simplicity of brain lactate metabolism and trafficking during brain activation in vivo is deceptive, and knowledge of pyruvate specific activity or fractional enrichment is necessary to interpret effects of lactate on glucose utilization. Unresolved issues include the cellular origin of lactate released into the extracellular fluid, flux through lactate pools, routes for dispersal and release of lactate, and the contribution of lactate oxidation to energetics of brain activation in neurons and astrocytes.

Unexplained Discordant Results Underlie Lactate-Related Controversies

When viewed in isolation, various studies may seem to support or oppose a model for brain lactate metabolism, but when evaluated within a broad context of different data sets related to the same issue, each set can ‘speak for itself' and trends or anomalies are easily recognized.

Glutamate Transport-Evoked Glycolysis is not a Robust, Intrinsic Property of all Cultured Astrocytes

Increased CMRglc and lactate production by cultured astrocytes exposed to glutamate in the culture medium is reproducibly observed in some laboratories but not in many others (Table 1). Responsive pure astrocyte cultures have different temporal responses to glutamate compared with astrocytes in mixed astrocyte–neuron cultures (Table 1). The basis for the presence or absence of a glycolytic response to glutamate is unknown (Hertz et al, 1998), but may be related to oxidative metabolism of glutamate, which stimulates astrocytic respiration and is oxidized in greater amounts with increasing extracellular level (Table 1). Use of ATP generated from glutamate oxidation to extrude sodium is consistent with the increase in CMRglc evoked by nonmetabolizable D-aspartate (Table 1). In the cerebellum in vivo, glutamate transport blockade has no effect on metabolic activation and lactate increase, whereas these changes are eliminated by AMPA receptor inhibition (Caesar et al, 2008), ruling out astrocytic glutamate transport-induced glycolysis as a major factor governing blood flow-metabolism upregulation.

Table 1. Discordant metabolic responses of cultured astrocytes to glutamate exposure.

| Preparation | Glutamate concentration (μmol/L) | Glucose utilizationa | Glucose uptakea | Lactate productiona | O2 utilizationa | Metabolite oxidation (substrate)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forebrain, cerebral cortical, or striatal astrocytes | 10–500 | +15 to +180 | +40 to +55 | Pellerin and Magistretti, 1994; Takahashi et al, 1995; Debernardi et al, 1999; Chatton et al, 2003 | |||

| 10–1,000 | +7 to −60 | 0 to −27 | 0 to −60 | −25 to −75 (glucose) | Hertz et al, 1998; Swanson et al, 1990; Peng et al, 2001; Qu et al, 2001; Gramsbergen et al, 2003; Liao and Chen, 2003; Dienel and Cruz, 2004 | ||

| 100 | +55 | Eriksson et al, 1995 | |||||

| 100 → 500 | 15% → 40% (glutamate) | McKenna et al, 1996 | |||||

| 200 | 0b | Prebil et al, 2011 | |||||

| 20,000 | +18b | ||||||

| (D-Aspartate, 500–1,000) | +20 | Peng et al, 2001 | |||||

| Hippocampal astrocytes in mixed astrocyte–neuron cultures | 500 | 2-NBDG, +110c 6-NBDG, +180c | Loaiza et al, 2003 | ||||

| 50, Acute | −20b | +130 | Bittner et al, 2011 | ||||

| 50, 20 minutes | +275b | ||||||

| 5, 20 minutes | +300b | ||||||

| (50, D-Aspartate) | 0b |

NBDG, N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)2-deoxyglucose.

Magnitude of response is expressed as approximate percentage change owing to treatment, 100[(treated−control)/control]. For details, see the original references and Tables 5 and 6 of Dienel and Cruz (2004). Except where noted, glucose utilization was assayed with deoxyglucose. Effects of D-aspartate, a nonmetabolizable substrate for the glutamate transporter, were also tested in some studies.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assays based on nanosensors that bind to intracellular glucose and report glucose concentration; glucose utilization is based on the change in glucose concentration, which does not reveal the pathway(s) that consume the glucose (glycolysis, pentose phosphate shunt pathway, glycogen synthesis, or sorbitol production if glucose levels are high).

Uptake assays were 10 minutes and measured change in fluorescence with time. 6-NBDG reflects only transport, whereas 2-NBDG uptake can reflect both transport and phosphorylation because there was no washout of unmetabolized precursor.

Brain Activation In Vivo Activates Glycogenolysis and Oxidative Metabolism in Astrocytes

Glycogen turnover is very slow under resting conditions, but astrocytes have significant resting oxidative activity, calculated to be ∼15% to 38% of total oxidative metabolism of glucose (Hyder et al, 2006; Duarte et al, 2011; Hertz, 2011). The astrocytic filopodial processes that surround and interact with synaptic structures contain mitochondria (Lovatt et al, 2007; Pardo et al, 2011; Lavialle et al, 2011) and have the potential to oxidize glucose, glycogen, and glutamate during activation. If brain activation stimulated only glycolysis in astrocytes, it would be reasonable to assign the ATP derived from this pathway toward the energetics of glutamate uptake. However, this is not the case. In vivo studies have shown that glycogenolysis, TCA cycle flux, and pyruvate carboxylation (a biosynthetic pathway involving the TCA cycle that also generates NADH and ATP; see Figure 1 and Hertz et al (2007)) are all increased in astrocytes in vivo under activating conditions (Table 2).

Table 2. Stimulus-induced increased metabolism in astrocytes in the rat or human brain in vivo.

| Experimental condition and substrate fuel |

Percentage increase in pathway activity |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycogenolysis (glycolysis) | TCA cycle | ||

| Sensory stimulation-cerebral cortex, conscious rat | |||

| Glycogen consumption (stimulation and recovery) | 14–32 | Cruz and Dienel, 2002 | |

| Release of label from glycogen | 22 | Dienel et al, 2007a | |

| Anesthetized rat | |||

| Acetate oxidation | 14 | Wyss et al, 2009 | |

| Metabolic washout of acetate-derived label | 93 | ||

| Conscious human—washout of acetate label | 62 | Wyss et al, 2009 | |

| Acoustic stimulation-inferior colliculus, conscious rat | |||

| Release of label from glycogen | 12 | Dienel et al, 2007a | |

| Acetate oxidation | 15–18 | Cruz et al, 2005 | |

| Visual stimulation-conscious rat | |||

| Release of label from glycogen, superior colliculus | 13 | Dienel et al, 2007a | |

| Acetate oxidation superior colliculus | 25–30 | Dienel et al, 2007b | |

| Acetate oxidation lateral geniculate | 14–20 | ||

| Operant training, conscious rat | Dienel et al, 2003 | ||

| Acetate oxidation in five brain regions | 15–24 | ||

| Spreading cortical depression-cerebral cortex | |||

| Conscious rat, acetate and butyrate oxidation | 15–40 | Dienel et al, 2001 | |

| Anesthetized rat, glycogen consumption | 10–28 | Krivanek, 1958 | |

| Pyruvate carboxylation, whole brain | |||

| Pentobarbital-anesthetized to awake rat | ∼400 | Öz et al, 2004 | |

TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

Glycogen and pyruvate carboxylase are located predominantly in astrocytes, and acetate is preferentially oxidized by astrocytes. These markers can be used to reveal changes in pathway fluxes in astrocytes in the brain in vivo. The fate of glycogen-derived pyruvate in vivo is not known; hence, glycogenolysis is considered to reflect glycolysis. As (1) calculated TCA cycle rates determined with [13C]acetate and [13C]glucose are similar (Hyder et al, 2006) and (2) calculated [14C]acetate oxidation is within the range of that estimated for astrocytic glucose oxidation (Cruz et al, 2005), it is likely that acetate oxidation rate reflects glucose oxidation rate in astrocytes. Pyruvate carboxylation is part of the anaplerotic pathway located in astrocytes (not neurons) for de novo synthesis of aspartate, glutamate, glutamine, and GABA from glucose (Figure 1). Increased anaplerotic flux generates ATP through NADH formed by pyruvate and isocitrate dehydrogenase reactions.

In our studies of acoustic stimulation of conscious rats that assayed both glucose utilization by all cells and acetate oxidation by astrocytes in the inferior colliculus in vivo, CMRglc increased by 0.49 μmol/g per min (from 0.71 to 1.20 μmol/g per min, or 69%) and acetate oxidation increased a minimal mean value of 0.02 μmol/g per min (from 0.126 to 0.146 μmol/g per min, or 16%) (see Table 5 in Cruz et al (2005)). Assuming 2 ATP produced by glycolysis and 32 ATP from the oxidative pathways (<38 ATP owing to proton leak), the increase in glycolysis in all cells would produce 2 × 0.49=0.98 μmol ATP/g per min, and the increase in astrocytic oxidative metabolism would generate 32 × 0.02=0.64 μmol ATP/g per min. Thus, a minimal estimate of the contribution of increased astrocytic oxidative metabolism (assuming that changes in acetate oxidation reflect those of glucose) is 65% that of total glycolysis in all cells. If half of the glucose is metabolized in astrocytes, then increased oxidative metabolism produces a similar amount of ATP as the increase in glycolysis. If all glycolytic ATP were used to power Na+-K+-ATPase to extrude sodium taken up with glutamate into astrocytes, then other unidentified, upregulated energy-requiring processes consume at least half of the additional ATP generated by the astrocytes. Contributions of glycogenolysis and oxidative flux related to pyruvate carboxylase activity (Table 2) are not included and would increase the total ATP produced by astrocytes further. Although speculative and approximate, this calculation suggests that working astrocytes are not well understood, and that further experiments are required to evaluate the energetics of astrocytic activation in vivo.

Cultured Neurons and Presynaptic Endings from the Adult Brain Increase Glucose Utilization

Arguments used by Jolivet et al (2010) in support of the need of neurons for lactate as fuel during activation include inability of neurons to increase glucose transport (citing Porras et al (2004) and a few other studies) and glycolysis (citing Herrero-Mendez et al (2009)). The Bolaños–Almeida–Moncada group has carried out an elegant series of studies (reviewed by Bolaños and Almeida (2010)) designed to elucidate the basis for high sensitivity of cultured cerebral cortical neurons to respiratory inhibition by nitric oxide (NO) and neuronal inability to increase glycolysis when treated with NO (Table 3). In brief, they showed that the enzyme 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose 2,6-bisphosphatase isoform 3 (Pfkfb3) that makes a potent allosteric activator of 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase (i.e., PFK, see Figure 1) is constantly degraded in cultured cortical neurons but not in cultured cortical astrocytes. Their cortical neurons have a lower glycolytic rate than do astrocytes, and neurons divert glucose-6-phosphate into the pentose phosphate shunt pathway to produce NADPH for management of oxidative stress (Figure 1). The study by Herrero-Mendez et al (2009) extended these findings by showing upregulation of neuronal Pfkfb3 confers to neurons the ability to increase glycolysis and lactate production at the expense of glucose-6-P flux into the pentose shunt pathway (Table 3). Bolaños and Almeida (2010) stated that different regulatory mechanisms may operate in other preparations and brain regions.

Table 3. Metabolic responses of cultured neurons derived from different brain regions to activating conditions.

| Brain region and harvest agea | Treatment | Response magnitudeb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral cortex | (Cortical neurons, a model for GABAergic neuronsa) | ||

| E14 | 5 → 50 mmol/L K+ | 10% ↑ DG phosphorylation | Peng et al, 1994 |

| 20% ↑ [U-14C]glucose to 14CO2 (low rate) | |||

| 20% ↓ [U-14C]lactate to 14CO2 | |||

| 115% ↑ [2-14C]pyruvate to 14CO2 (very low rate) | |||

| E16–17 | 1.4 μmol/L nitric oxide | 85% ↓ O2 uptake, no change in lactate production | Almeida et al, 2001 |

| 100 μmol/L Glutamate | No change in lactate production | Almeida et al, 2004 | |

| Overexpression of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-3 | 550% ↑glycolysis, 190% ↑lactate level, 50% ↓pentose phosphate shunt pathway (PPP) flux (control neurons: PPP flux=200% glycolytic flux) | Herrero-Mendez et al, 2009; Bolaños and Almeida, 2010 | |

| E17 | Hypoxia, 3 days | 200% ↑ glucose utilization | Malthankar-Phatak et al, 2008 |

| 330% ↑ lactate concentration in medium | |||

| E16–17 | Hypoxia for 24 hours | 200% ↑ lactate concentration in medium | Sher, 1990 |

| E15 | 55 mmol/L K+ | 50% ↑ cycling ratio for glutamate=increased TCA cycle activity | Waagepetersen et al, 2000 |

| E18 | 33 μmol/L Glutamate | 200–250% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | Gleichmann et al, 2009 |

| 7–32 μmol/L FCCP | 200–250% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | ||

| E15 | 25 nmol Dinitrophenol | 20% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | Jameson et al, 1984 |

| E17 | 2 μmol/L amyloid-β1–42 , 4 days | 200% ↑ [1-14C]glucose to 14CO2; 155% ↑ [6-14C]glucose to 14CO2; 205% ↑ pentose phosphate shunt pathway | Soucek et al, 2003 |

| Cerebellum | (Cerebellar granule neurons, a model for glutamatergic neuronsa) | ||

| PN7 | 5 → 50 mmol/L K+ | 75% ↑ DG phosphorylation | Peng et al, 1994 |

| 120% ↑ [U-14C]glucose to 14CO2 | |||

| 20% ↑ [U-14C]lactate to 14CO2 | |||

| 110% ↑ [2-14C]pyruvate to 14CO2 | |||

| PN7 | 50 μmol/L Glutamate | 30% ↑ DG phosphorylation | Peng and Hertz, 2002 |

| 500 μmol/L Glutamate | 40% ↑ DG phosphorylation | ||

| 5.4 → 55 mmol/L K+ | 75% ↑ lactate production rate; 75% ↑ [U-14C]glucose to 14CO2 | ||

| PN8 | 25 nmol Dinitrophenol | 43% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | Jameson et al, 1984 |

| PN6–7 | Hypoxia, 7h | 100% ↑ lactate production | Sonnewald et al, 1994 |

| PN8 | 100 μmol/L Glutamate | 115% ↑ DG uptake plus phosphorylation (10 minute assay) | Minervini et al, 1997 |

| 100 μmol/L NMDA | 180% ↑ DG uptake plus phosphorylation (10 minute assay) | ||

| 60 μmol/L Kainate | 220% ↑ DG uptake plus phosphorylation (10 minute assay) | ||

| 100 μmol/L Quisqualate | 55% ↑ DG uptake plus phosphorylation (10 minute assay) | ||

| PN5–7 | Respiration assays in 25 mmol/L K+ 2 μmol/L FCCP | 175% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | Jekabsons and Nicholls, 2004 |

| 250 μmol/L Glutamate + 25 μmol/L glycine | 32–60% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | ||

| 300 μmol/L NMDA | 33–36% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | ||

| PN5–7 | Respiration assays in 3.9 mmol/L K+ 3 μmol/L FCCP | 250–325% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | Yadava and Nicholls, 2007 |

| 100 μmol/L Glutamate + 10 μmol/L glycine | 250–325% ↑ oxygen consumption with glucose substrate | ||

| PN7–8 | DG assays in 3.9 mmol/L K+ | Ward et al, 2007 | |

| 100 μmol/L Glutamate + 10 μmol/L glycine for 10 minutes, then new medium with no glutamate + [3H]DG for 20 minutes | 50% ↑ DG phosphorylation (reflecting ↑ glucose utilization) | ||

| Hippocampus | |||

| Neurons in mixed | 500 μmol/L Glutamate or 20 μmol/L AMPA | 75–80% ↓ 2- or 6-NBDG uptake—fast, reversible | Porras et al, 2004 |

| Neuron–astrocyte | 75 μmol/L veratridine | No change in 6-NBDG uptake for ∼10 minutes, then 70% ↓ | |

| Cultures (PN1–3) | 40 mmol/L KCl | No effect on 6-NBDG uptake | |

| Neurons | 100 μmol/L Glutamate, 10 minutes | No effect on DG uptake | Patel and Brewer, 2003 |

| (E18) | 1 μmol/L FCCP + 10 mg/mL | 200% ↑ DG uptake at 5 minutes | |

| oligomycin 100 μmol/L Glutamate + 1 μmol/L FCCP + 10 mg/mL oligomycin | 135% ↑ DG uptake at 5 minutes | ||

| Neurons | Acute anoxia | 40% ↑ DG uptake | Yu et al, 2008 |

| (PN0) | Acute anoxia after hypoxic preconditioning, 20 minutes/day for 6 days | 90% ↑ DG uptake | |

AMPA, 2-amino-3-(5-methyl-3-oxo-1,2-oxazol-4-yl)propanoic acid; DG, deoxyglucose; NBDG, N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)2-deoxyglucose; TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

The age at which tissue was obtained for cultured cells is denoted by E=embryonic or PN=postnatal, followed by the age in days. Cerebral cortical neuronal cultures obtained from ∼15-day-old embryos are used as a model system for GABAergic neurons, and cerebellar granule neurons obtained from ∼7 day-old postnatal rodents are used as a model system for glutamatergic neurons (Yu et al (1984); Schousboe et al (1985); Hertz et al (1988) cited references). It must be noted that culture conditions and duration, composition of the culture medium, and cellular development during time in culture influence characteristics of the cultures (e.g., Hertz et al (1998); Hertz (2004) cited references).

Magnitude of response is expressed as approximate percentage change owing to treatment, 100[(treated−control)/control)]. DG assays are typically used to measure hexokinase-dependent phosphorylation as a measure of glucose utilization. 2-NBDG is a fluorescent glucose analog that is transported and phosphorylated, whereas 6-NBDG is transported but not phosphorylated. Brief assays (<5 minutes) with DG or 2-NBDG measure mainly transport (uptake), intermediate duration assays (5–10 minutes) can represent transport plus phosphorylation depending on washout of unmetabolized precursor from cells at the end of the assay, and longer assays with DG or 2-NBDG reflect mainly phosphorylation that can be overestimated somewhat if unmetabolized precursor is not completely washed out. 6-NBDG accumulation reflects transport until intracellular and extracellular levels equilibrate. See legend to Table 4 for more details related to sites of action of metabolic inhibitors.

In fact, many laboratories have shown that different types of cultured neurons can substantially upregulate glucose metabolism, whereas a few preparations have no or small responses. Many cerebral cortical neuron preparations (a model for GABAergic neurons) do respond to many treatments (e.g., depolarization, hypoxia, exposure to glutamate, treatment with uncouplers or amyloid-β) with quite large increases in glycolysis and glucose-supported respiration, indicating that glucose transport must increase in parallel (Table 3). Cultured cerebellar granule cell neurons (a model for glutamatergic neurons) also exhibit large metabolic responses to depolarization, uncouplers, hypoxia, glutamate, NMDA, and other conditions (Table 3). Cerebral glucose utilization in cultured hippocampal neurons increases during exposure to uncouplers and anoxia, and is not affected by glutamate (Table 3). Conversely, hippocampal neurons in mixed astrocyte–neuron cultures exhibit reduced NBDG uptake upon glutamate exposure, delayed inhibition of NBDG uptake after veratridine exposure, and no response to depolarization (Table 3). The inability of neuronal cultures to respond to activating conditions by increasing CMRglc, glycolysis, pentose shunt flux, or respiration is an exception, not the rule (Table 3).

Synaptosomes embody the metabolic capabilities of nerve endings from the mature brain, although their capacity may be reduced by losses of soluble enzymes, ATP, Pi, and phosphocreatine during preparative procedures. Synaptosomes isolated from adult brain regions, including the hippocampus and cerebral cortex from different species, have high metabolic capacity and respond with large increases in glucose-supported respiration to depolarization, uncouplers, anoxia, enhanced ion fluxes, and NO donors (Table 4). Inhibition of MAS with aminooxyacetate reduces uncoupler-evoked respiration (Table 4). Glycolysis and glucose-supported respiration in hippocampal and cortical synaptosomes are enhanced by K+ and veratridine (Table 4), sharply contrasting the responses of hippocampal neurons in mixed cultures (Table 3). The magnitude of response to Na+-stimulated glucose oxidation increases with developmental age, and is much higher in synaptosomes isolated from adult compared with the immature brain (Table 4).

Table 4. Metabolic responses of synaptosomes to activating conditions.

| Substratea and treatmentb | Response magnitudec | Tissue source and Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical stimulation | 20–65% ↑respiration rate, 10–70% ↑ glycolysis | Seven brain regions from adult rat, sheep, or rabbit |

| Glucose + 50 mmol/L K+ | 15% ↑ respiration rate, 30% ↑ glycolysis | Bradford, 1975 |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 24 mmol/L KCl | 137% ↑ respiration rate | Cerebral cortex, adult rat |

| 85% ↑ [1-14C]pyruvate decarboxylation | Schaffer and Olson, 1980 | |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 40 mmol/L KCl | 69% ↑ respiration rate | Adult rat forebrain |

| Erecińska et al, 1991 | ||

| 5 mmol/L pyruvate + 40 mmol/L KCl | 63% ↑ respiration rate | |

| 9.5 mmol/L [U-14C]glucose + 72 mmol/L Na+ | 180% ↑ glucose oxidation to 14CO2 | Whole brain from adult or immature rats |

| + 100 μmol/L 2,4-dinitrophenol | 370% ↑ glucose oxidation to 14CO2 | Diamond and Fishman, 1973 |

| Developmental age from 1 to 90 days | 500%↑ Na+-stimulated glucose oxidation to 14CO2 | |

| Developmental age from 10 to 20 days | 200%↑ Na+-stimulated glucose oxidation to 14CO2 | |

| 1 mmol/L [U-14C]glucose + 100 μmol/L veratridine | 290% ↑ glucose oxidation to 14CO2 | Adult rat forebrain |

| Harvey et al, 1982 | ||

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 100 μmol/L veratridine | 300% ↑ respiration rate | Adult rat hippocampal mossy fiber synaptosomes |

| Terrian et al, 1988 | ||

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 0.5 μmol/L FCCP | Immediate 500% ↑ respiration rate | Cerebral cortex, 4–8-week-old guinea pig |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 100 μmol/L veratridine, followed by 0.5 μmol/L FCCP | Immediate veratridine-induced 175% ↑ respiration, followed by an immediate additional 65% FCCP-evoked ↑ respiration | Scott and Nicholls, 1980 |

| 1.5 mmol/L glucose + [3,4-14C]glucose + 100 μmol/L 2,4-dinitrophenol | 120% ↑ glucose oxidation to 14CO2 | Adult rat forebrain Ksiezak and Gibson, 1981a,1981b |

| 1.5 mmol/L glucose, severe hypoxia (O2 tension 19 torr → <1 torr) | 250% ↑ lactate production rate | |

| 5 mmol/L glucose + 1 mmol/L cyanide or 6 μmol/L rotenone | Block respiration, 9-fold increase glycolysis | Cerebral cortex, adult guinea pig Kauppinen and Nicholls, 1986a |

| 5 mmol/L glucose + Nitrogen atmosphere (anoxia ) | Ten-fold increase in glycolysis | |

| 5 mmol/L glucose + A23187 (divalent cation ionophore) | Three-fold stimulation respiration, 5-fold stimulation glycolysis | |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + anoxia | 335% ↑ lactate amount produced | Adult rat forebrain |

| White et al, 1989 | ||

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 1 μmol/L FCCP | 900% ↑ glycolysis maintained for at least 30 minutes 500% ↑ respiration | Cerebral cortex, adult guinea pig Kauppinen and Nicholls, 1986b |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 1 mmol/L arsenite (inhibit pyruvate oxidation) | 35% inhibition respiration, 3-fold increase in glycolysis | |

| 5 mmol/L glucose + 45 mmol/L KCl | 55% ↑ glycolysis, 47% ↑pyruvate decarboxylation | Cerebral cortex, 6–10-week-old guinea pig Kauppinen et al, 1989 |

| 5 mmol/L glucose + 75 μmol/L veratridine | 250% ↑ glycolysis, 290% ↑pyruvate decarboxylation | |

| 5 mmol/L glucose + 1 μmol/L Cl-CCP | 650% ↑pyruvate decarboxylation | |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + anoxia | 2,100% ↑ lactate synthesis rate | Adult rat cerebral cortex |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 10 μmol/L veratridine | 160% ↑ respiration rate, 75% ↓ lactate synthesis rate | Gleitz et al, 1993 |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 1 mmol/L nitroprusside or 100 μmol/L S-nitrocysteine | Aerobic conditions: 20–30% ↑ lactate synthesis rate; 70% ↑ lactate amount at 15 minutes | Adult rat forebrain Erecińska et al, 1995 |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 10 μmol/L rotenone | 900% ↑ lactate synthesis rate | |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 40 μmol/L veratridine, 5 minutes | 210% ↑ respiration, 515% ↑ lactate production | Adult rat forebrain Erecińska et al, 1996 |

| 15 minutes | 135% ↑ respiration, 620% ↑ lactate production | |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 10 μmol/L monensin, 5 minutes | 73% ↑ respiration, 1,100% ↑ lactate production | |

| 15 minutes | 70% ↑ respiration, 580% ↑ lactate production | |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 5 μmol/L nigericin, 5 minutes | 58% ↑ respiration, 465% ↑ lactate production | |

| 15 minutes | 8% ↑ respiration, 200% ↑ lactate production | |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 100 (young rats) or 50 (old rats) μmol/L veratridine | 120 or 110% ↑ respiration in synaptosomes from young or old rats, respectively | Whole brain from 3-month (young) or 24 (old)-month rats Joyce et al, 2003 |

| 10 mmol/L glucose + 240 nmol/L FCCP | 150 or 88% ↑ respiration in synaptosomes from young or old rats, respectively | |

| 15 mmol/L glucose + 4 μmol/L FCCP | 300% ↑ respiration rate | Cerebral cortex, 17–20 day-old mouse |

| 10 mmol/L pyruvate + 4 μmol/L FCCP | 230% ↑ respiration | Choi et al, 2009 |

| 15 mmol/L glucose + 10 mmol/L pyruvate + 4 μmol/L FCCP | 225% ↑ respiration rate | |

| 15 mmol/L glucose + 2–5 μmol/L veratridine | 100–135% ↑respiration, 200–300%, ↑extracellular acidification (i.e., ↑glycolysis with lactate production and release) | |

| 15 mmol/L glucose + 10 mmol/L pyruvate + 2–5 μmol/L veratridine | 210–165% ↑respiration, 180–250% ↑extracellular acidification | |

| 15 mmol/L glucose + 10–100 μmol/L AOAA | No effect on basal respiration rate | |

| 15 mmol/L glucose + 4 μmol/L FCCP + 10 μmol/L AOAA | 15% inhibition of maximal FCCP-evoked rate | |

| + 30 μmol/L AOAA | 30% inhibition of maximal rate | |

| + 100 μmol/L AOAA | 45% inhibition of maximal rate | |

| 15 mmol/L glucose + 10 mmol/L pyruvate + 0.05–1 mmol/L 4-aminopyridine | 35% ↑respiration rate compared with without 4-aminopyridine | |

| 15 mmol/L glucose + 10 mmol/L pyruvate + 4 μmol/L FCCP | Values normalized by number of bioenergetically competent synaptosomes: | Cerebral cortex or striatum from 3 to 4 month-old mice |

| 447 or 452 ↑ respiration rate in dopamine transporter-enriched synaptosomes from the striatum or cortex, respectively | Choi et al, 2011 | |

| 538 or 542 ↑ respiration rate in residual nondopaminergic synaptosomes from the striatum or cortex, respectively |

Synaptosomes are heterogeneous populations of presynaptic nerve endings that contain mitochondria and are capable of glycolytic and oxidative metabolism of glucose and other substrates. Glycolysis generates ATP plus pyruvate when reducing equivalents are transferred from cytoplasmic NADH to the mitochondria by the malate–aspartate shuttle (MAS). NADH can also be oxidized to regenerate NAD+ by production of lactate, which is sometimes used as a surrogate marker for glycolytic pathway flux. Oxidation of pyruvate through the tricarboxylic acid cycle generates NADH and FADH2. The electron transport chain transfers electrons from NADH and FADH2 to oxygen, along with extrusion of protons from the mitochondrial matrix. Proton reentry into the matrix through ATP synthetase drives ATP synthesis. In well-coupled mitochondria, respiration rate (oxygen consumption or uptake) is coupled to ATP synthesis, and ‘respiratory control' is exerted by energy demand, i.e., ADP availability. Respiration in the absence of ATP synthesis is low and arises from proton leakage into the matrix.

Synaptosomal energetics can be modulated by treatment with compounds that inhibit specific metabolic or transport reactions, abolish respiratory control, or increase energy demand. The MAS can be blocked by aminooxyacetate (AOAA), which inhibits pyridoxal-dependent enzymes (e.g., aminotransferases), thereby reducing activity of the malate–aspartate shuttle, preventing reoxidation of cytosolic NADH, and blocking the ability of mitochondria to use glycolytic pyruvate. 4-CIN (α-cyanocinnamate) inhibits monocarboxylic acid transporters and pyruvate transport into the mitochondria. Electron transport can be inhibited at different sites, complex I (NADH dehydrogenase complex) by rotenone; complex II (succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein complex) by 2-nitropropionate, malonate, or methylmalonate; complex III (cytochrome bc1 complex) by antimycin A; and complex IV (cytochrome a1a3 or cytochrome oxidase) by cyanide, azide, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, or anoxia. Oligomycin inhibits proton reentry into the mitochondrial matrix through the ATP synthase and blocks ATP synthesis; the residual respiration reflects the proton leak into the matrix. FCCP (carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone), Cl-CCP (carbonylcyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone), and dinitrophenol are uncouplers or protonophores that allow proton reentry into the mitochondrial matrix and relieve respiratory control by diverting the proton current away from the ATP synthase and reducing the capacity to generate ATP. Uncouplers stimulate respiration, and FCCP treatment can reveal maximal respiratory capacity, i.e., the available capacity of nerve endings or cells for substrate delivery and electron transport to increase ATP synthesis in response to increased ATP demand. Ion movements can also be altered to increase ATP demand and stimulate metabolism. Increased extracellular K+ levels are a consequence of neuronal activity, and depolarization of cells or nerve endings with high concentrations of KCl stimulates energy production. Veratridine prevents inactivation of voltage-activated sodium channels and causes intracellular Na+ to increase, thereby increasing ATP use by Na+-K+-ATPase; veratridine also causes intracellular Ca2+ to increase, followed by glutamate release. 4-Aminopyridine (4-AP) is an inhibitor of A-type K+ channels that causes synaptosomes to fire repetitive action potentials. NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate, is an agonist for a class of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Nigericin and monensin are ionophores that exchange H+ for K+ or Na+, respectively, whereas A23187 exchanges a divalent cation (Ca2+ or Mg2+) for 2H+. For more details regarding synaptosomal bioenergetics and responses to various treatments, see Nicholls (2003, 2009, 2010) and Erecińska et al (1996).

Magnitude of response is expressed as approximate percentage change owing to treatment, 100[(treated−control)/control], or, when indicated (i.e., as ‘–fold' change), treated relative to control ratio.

To summarize, many preparations of cortical, cerebellar, and hippocampal neurons and synaptosomes upregulate various pathways of glucose metabolism under many different conditions. However, cultured neurons derived from different brain regions may not have the same metabolic capacities or responses to the same treatment. Synaptosomes are one structure of adult brain neurons that is readily isolated, and these nerve terminals can increase glycolysis and respiration by 5- to 10-fold in vitro. Glucose transport and glycolytic flux must increase in parallel with glucose-supported respiration. Citation of selected metabolic studies that support a point of view (Jolivet et al, 2010) does not provide an appropriate perspective of the field.

Neurons can Quickly Upregulate Glucose Transport Capacity During Activation

Glutamate inhibits NBDG transport into cultured neurons (Porras et al, 2004; Table 3) and stimulates glucose transport into cultured astrocytes (Loaiza et al, 2003; Table 1). These findings have been interpreted by Pierre et al (2009) as rerouting of glucose from neurons to astrocytes during glutamatergic neurotransmission, so neurons would depend on astrocyte-derived lactate as a fuel, in accordance with the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle hypothesis. However, these results sharply contrast those from other neuronal cultures that exhibit glutamate-induced increases in CMRglc and 2- to 3-fold stimulation of glucose-supported respiration by glutamate in cultured cerebral cortical neurons and cerebellar granule neurons (Table 3). Moreover, nerve endings isolated from both immature and adult brains are capable of large increases in glycolysis and glucose-supported respiration (Table 4). Therefore, neuronal glucose transport must increase simultaneously with stimulation of its utilization.

Neuronal glucose transport capacity is enhanced within minutes by treatment of cultured neurons with glutamate, bicuculline, and a NO donor by increasing cell-surface expression of the neuronal glucose transporter (GLUT)3 throughout the neuronal processes and soma (Table 5). Upregulation of the GLUT3 protein level is slower than cell-surface translocation, and is stimulated in vivo by conditions that affect CMRglc in the brain (Table 5). Glucose transport into neurons is critical for brain function, and in the adult rat brain, GLUT3 is localized in synaptic terminals, small neuronal processes, and postsynaptic structures, with significant intracellular localization (Leino et al, 1997). Glucose transporter-3 deficiency causes serious developmental abnormalities in mice (Table 5). Taken together, the rapid increases in glucose transport capacity by cultured hippocampal, cortical, and cerebellar neurons and synaptosomes plus increased glucose utilization show that neurons require and consume more glucose when activated.

Table 5. Neuronal glucose transporter GLUT3: treatment-evoked changes in cell surface expression and total protein level, and functional abnormalities in mice with GLUT3 deficiency.

| Preparationa | Treatmenta | Duration | Response Magnitude b | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal neurons (E18) | 100 μmol/L Glutamate + 1 μmol/L FCCP + | 5–20 minutes | 60% ↑GLUT3 surface expression 130% ↑DG transport | Patel and Brewer, 2003 |

| 10 mg/mL oligomycin | ||||

| Cerebellar granule neurons (PN7) | 100 μmol/L Glutamate + 10 μmol/L glycine | 30–60 minutes | 30–55% ↑GLUT3 surface expression | Weisová et al, 2009 |

| Cerebral cortical neurons (E18) | 50 μmol/L Bicuculline + 100 μmol/L 4- | 15 minutes | 400% ↑GLUT3 surface expression | Ferreira et al, 2011 |

| Aminopyridine (AP) | 30 minutes | 1,900% ↑GLUT3 surface expression | ||

| 50 μmol/L NOR3 (nitric oxide donor) | 15 minutes | 1,400% ↑GLUT3 surface expression | ||

| Hippocampal neurons (E18) | 50 μmol/L Bicuculline + 100 μmol/L 4-AP | 15 minutes | 300% ↑GLUT3 surface expression | |

| 50 μmol/L Bicuculline + 100 μmol/L 4-AP | 15 minutes | 80% ↑GLUT3 surface expression in dendrites | ||

| 50 μmol/L NOR3 (nitric oxide donor) | 5 minutes | 700% ↑GLUT3 surface expression | ||

| 50 μmol/L Bicuculline + 100 μmol/L 4-AP | 15 minutes | 60% ↑2-NBDG mainly phosphorylation | ||

| Cerebellar granule | 5 → 15 or 25 mmol/L KCl | 8 days | 150–200% ↑GLUT3 protein level | Maher and Simpson, |

| neurons (PN8) | 250–550% ↑DG transport | 1994 | ||

| 15 mmol/L KCl + 150 μmol/L NMDA | 80% ↑GLUT3 protein level versus 15 mmol/L KCl | |||

| 60% ↑DG transport versus 15 mmol/L KCl | ||||

| Adult rat | Repeated hypoglycemia | 4 days | 50% ↑GLUT3 protein level in forebrain | Lee et al, 2000 |

| Water deprivation | 2–3 days | 40–55% ↑GLUT3 protein level in neurohypophysis | Vannucci et al, 1994 | |

| Streptozotocin diabetes | 2 weeks | 50% ↑GLUT3 protein level | ||

| Streptozotocin diabetes + 6 hours/day restraint stress | 7 days | 10–20% ↑GLUT3 protein level in regions of the hippocampus | Reagan et al, 1999 | |

| Heterozygous GLUT3-deficient mice | Tests were carried out with 7-day-old or 2–12-month-old mice | Developmental abnormalities leading to autism spectrum disorders including abnormal spatial learning, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Animals also have EEG seizures and perturbed social behavior | Zhao et al, 2010 |

The age at which tissue was obtained for cultured cells is denoted by E=embryonic or PN=postnatal, followed by the age in days. Bicuculline is a GABA receptor antagonist; see legends to Tables 3 and 4 for more details about actions of inhibitors.

Magnitude of response is expressed as approximate percentage change owing to treatment, 100 [(treated−control)/control]. Deoxyglucose (DG) assays are typically used to measure glucose phosphorylation, but brief assays are also used to measure transport. 2-NBDG is a fluorescent glucose analog that is transported and phosphorylated; the 15 minutes assay in this study probably reflects mainly phosphorylation.

Dendritic Spine Energetics: Is Monocarboxylic Acid Transporter-2 used for Lactate Release?

Neuronal MCT2 and AMPA receptor GluR2/3 are colocalized in postsynaptic densities of glutamatergic synapses between parallel fibers and Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (Bergersen et al, 2001, 2005), and these two proteins are translocated to the cell surface from intracellular stores in parallel under activating conditions (Pierre et al, 2009). Monocarboxylic acid transporter-2 localization and trafficking are claimed to facilitate uptake of astrocyte-derived lactate as oxidative fuel for these glutamatergic spines (Bergersen et al, 2005, 2007; Pierre et al, 2009). However, spines do not contain the mitochondria (Bergersen et al, 2001, 2002); hence, lactate, ADP, and phosphate must diffuse through the spine neck to the mitochondria in the dendritic shaft, followed by lactate oxidation and synthesis of ATP, then diffusion of ATP back to postsynaptic density for its utilization. This scenario does not include glucose transport and metabolism in spines, and to understand the energetics of dendritic structures more fully, it is important to know the relative levels of GLUT3 compared with MCT2 in presynaptic and postsynaptic structures and to evaluate glucose and lactate metabolism in these structures.

Most dendritic spines have very few mitochondria, in contrast to the shafts (Li et al, 2004; Bourne and Harris, 2008). Postsynaptic densities contain glycolytic enzymes that synthesize ATP (Wu et al, 1997), and GLUT3 is localized in synaptic endings and postsynaptic structures (Leino et al, 1997). Calcium clearance in activated cultured cerebellar granule neurons and in Purkinje cells in brain slices relies on glycolysis to power the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase in the soma, dendrites, and spines, and inhibition of mitochondrial ATP generation does not affect operation of this pump (Ivannikov et al, 2010). These findings underscore the importance of glycolysis in neuronal dendritic spines and show that diffusion of ATP from the dendritic shaft into the spine cannot support calcium pumping at the plasma membrane of spines. Therefore, trafficking of MCT2 might be required to release lactate generated by glycolysis in the spine into extracellular fluid, so that high glycolytic flux can be maintained within the spine at the site of the postsynaptic density. Avid lactate uptake by nearby astrocytes could then oxidize or disperse and discharge the lactate to more remote locations (Gandhi et al, 2009).

Net Transport of Lactate Across the Blood–Brain Barrier In Vivo

Arteriovenous differences are used to evaluate brain uptake and release of compounds, but limited access to venous drainage systems restricts these assays to the whole brain, cerebral cortex, and eye. Small amounts of lactate (∼5% of glucose uptake) are released from resting brain, and during activation, lactate release increases to 15% to 22% of glucose influx (Tables 6A and 6B). Importantly, lactate release can occur even when global brain lactate levels are lower than blood (Table 6A), presumably owing to locally high brain lactate levels. Krebs (1972) noted that the eye is highly glycolytic, and lactate release from the eye exceeds that from the brain, ranging from ∼20% to 100% of glucose uptake (Table 6C). Lactate is also released from the human brain during stressful cognitive testing (Table 6E). When blood lactate levels increase during sensory stimulation (Table 6D) or graded exercise (Table 6E), lactate enters the brain in progressively increasing amounts. Activation is associated with lactate release, but strenuous physical activity increases blood lactate level and brain uptake.

Table 6. Lactate release from the brain and eye during activation and lactate uptake during exercise.

| Tissue and experimental condition | Glucose | Lactate | Lactate flux (%glucose influx)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Conscious rat brain, acute ammonia challengeb | Hawkins et al, 1973 | |||

| Before ammonia injection | ||||

| Arterial (A) blood level (mmol/L) | 5.10 | 2.64 | ||

| Cerebral venous (V) blood (mmol/L) | 4.53 | 2.68 | ||

| A–V difference (mmol/L) | 0.57 | −0.04 | −4% | |

| Brain level (μmol/g) | 0.75 | 1.25 | ||

| 4–5 minutes after ammonia injection | ||||

| Arterial blood level (mmol/L) | 5.74 | 3.20 | ||

| Cerebral venous blood (mmol/L) | 4.97 | 3.43b | ||

| A–V difference (mmol/L) | 0.77* | −0.23**b | −15% | |

| Brain level (μmol/g) | 1.05** | 2.39**b | ||

| B. Conscious rat brain, spreading cortical depressionc | Adachi et al, 1995; Cruz et al, 1999 | |||

| Arterial blood level (mmol/L) | 7.32 | 0.87 | ||

| A–V difference (mmol/L) | 0.62 | −0.27* | −22% | |

| Brain level (μmol/g) | 1.2 | 8.5** | ||

| C. Eye, anesthetized animalsd | ||||

| Rabbit retina | ||||

| A–V difference (mmol/L)e | 0.39 | −0.37 | −47% | Krebs, 1972 |

| Rate of consumption or production (μmol/min) | Wang and Bill, 1997 | |||

| Dark | 0.204 | −0.160 | −39% | |

| Light 10 lux | 0.197 | −0.153 | −39% | |

| Light 150 lux | 0.206 | −0.146 | −35% | |

| Light | 0.221 | −0.212 | −48% | |

| 4 Hz flicker | 0.258*** | −0.242** | −47% | |

| Pig outer retina, A–V difference (mmol/L) | Wang et al, 1997a | |||

| Dark | 0.304** | −0.372** | −61% | |

| Light | 0.182 | −0.160 | −44% | |

| Pig inner retina, A–V difference (mmol/L) | Wang et al, 1997b | |||

| Dark | 0.731* | −0.296 | −20% | |

| Light | 0.625 | −0.324 | −26% | |

| Cat outer retina, use or release rate (μmol/min) | Wang et al, 1997c | |||

| Dark | 0.236** | −0.409** | −87% | |

| Light | 0.123 | −0.253 | −103% | |

| D. Conscious rat brain, generalized sensory stimulatione | Madsen et al, 1999 | |||

| Before stimulation | ||||

| Arterial blood (mmol/L) | 6.81 | 0.50 | ||

| A–V difference (mmol/L) | 0.68 | −0.08 | −6% | |

| Brain (μmol/g) | 2.8 | 1.0 | ||

| After 5 minutes of stimulation | ||||

| Arterial blood level (mol/L) | 7.81* | 1.9* | ||

| A–V difference (mmol/L) | 0.60 * | +0.02* | +2% * | |

| Brain level (μmol/g) | 3.1 | 1.9* | ||

| E. Conscious human braine | LactateArterial (mmol/L) | (A−V)Lactate (mmol/L) | ||

| Rest | 0.46 | −0.04 | −5% | Madsen et al, 1995 |

| Cognitive activation + stress | 0.47 | −0.06*** | −7%** | |

| Rest | 0.94 | −0.04 | −4% | Dalsgaard, 2006 |

| Light exercise | 0.99 | −0.05 | −5% | |

| Moderate exercise | 3.16 | +0.12* | +11%* | |

| Maximal exercise | 6.95 | +0.50** | +41%** | |

| Early recovery | 14.9 | +0.71** | +44%** | |

Positive arteriovenous differences (A−V) across the brain indicate uptake into brain, whereas negative values denote efflux from the brain. Tabulated data are mean values from the cited references.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 versus control.

Lactate flux from or to the brain (in glucose equivalents) is expressed as percentage of glucose uptake, i.e., 100[(A−V)lactate/2]/(A−V)glucose.

Note that lactate was released from the brain in ammonia-loaded rats even though the brain lactate level is lower than that in blood. As lactate transport is passive and concentration gradient-driven, these results suggest locally high brain lactate levels that exceed the average value in tissue (see text).

Efflux of 14C-labeled lactate from the brain to blood during spreading cortical depression in the conscious rat was detectable within 2 minutes after an intravenous pulse of [6-14C]glucose, and between 2 and 8 minutes after the pulse of [14C]glucose the efflux of [14C]lactate from brain was equivalent to that of unlabeled lactate indicating rapid equilibration with glycolytic intermediates and efflux of lactate derived from brain metabolism of blood-borne glucose (Cruz et al, 1999).

The retina of the pig and cat is more metabolically active in the dark compared with light (contrasting the rabbit), presumably because light inhibits rod metabolism by inhibiting the dark current (Wang and Bill (1997) and references cited therein).

Under ‘resting' conditions, there is a slight efflux of lactate from the brain to blood as long as the blood lactate is relatively low (A, D; also see Madsen et al (1998); Linde et al (1999); Schmalbruch et al (2002)), in sharp contrast to the eye that releases large amounts of lactate under resting and activated conditions (C). When blood lactate increases above that in the brain during physical movement (D, rat) with moderate and strenuous exercise (E, human), lactate influx increases markedly and it becomes a significant brain fuel (Dalsgaard, 2006; Quistorff et al, 2008; van Hall et al, 2009).

Extracellular Lactate as Fuel During Activation