Abstract

Background

Up to 25% of patients with untreated Kawasaki Disease (KD) and 5% of those treated with intravenous immunoglobulin will develop coronary artery aneurysms. Persistent aneurysms may remain silent until later in life when myocardial ischemia can occur. We sought to determine the prevalence of coronary artery aneurysms suggesting a history of KD among young adults undergoing coronary angiography for evaluation of possible myocardial ischemia.

Methods and Results

We reviewed the medical history and coronary angiograms of all adults under age 40 who underwent coronary angiography for evaluation of suspected myocardial ischemia at four San Diego hospitals from 2005–2009 (n=261). History of KD-compatible illness and cardiac risk factors (RF’s) were obtained by medical record review. Angiograms were independently reviewed for the presence, size, and location of aneurysms and CAD by two cardiologists blinded to the history. Patients were evaluated for number of RF’s, angiographic appearance of their coronary arteries, and known history of KD. Of the 261 young adults who underwent angiography, 16 had coronary aneurysms. After all clinical criteria were assessed, 5.0% had aneurysms definitely (n=4) or presumed (n=9) secondary to KD as the etiology of their coronary disease.

Conclusions

Coronary sequelae of KD are present in 5% of young adults evaluated by angiography for myocardial ischemia. Cardiologists should be aware of this special subset of patients who may benefit from medical and invasive management strategies that differ from the treatment of atherosclerotic CAD.

Keywords: aneurysm, angiography, coronary artery disease, ischemic heart disease, Kawasaki disease

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute, self-limited vasculitis of unknown etiology that occurs in young children. It presents as a febrile illness with mucocutaneous changes. Diagnosis depends upon recognition of the clinical syndrome since no diagnostic test exists. Although an effective treatment reduces the risk of long-term cardiovascular sequelae,1 KD can be difficult to recognize and many cases go undiagnosed. Approximately 25% of children with untreated KD (and 5% of those treated with intravenous immunoglobulin) will develop coronary aneurysms.2–5 As children with coronary aneurysms due to KD grow older, they are at increased risk for myocardial infarction and other adverse events.3, 6 The first presentation in individuals with missed KD may be an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, due to thrombus formation in the aneurysmal segment of the coronary artery.7 Coronary artery damage during acute KD can also lead to calcification and stenotic lesions associated with myointimal proliferation later in life.6, 8 However, the true impact of coronary aneurysms and coronary artery damage due to KD, and their prevalence among young adults presenting with symptoms of cardiac ischemia, has not been systematically studied. Therefore, we sought to determine the prevalence of coronary artery aneurysms suggesting a history of KD among young adults undergoing coronary angiography for evaluation of possible myocardial ischemia.

Methods

Study Population

All adults under the age of 40 years who underwent coronary angiography for suspected myocardial ischemia between July 1, 2005 and June 30, 2009 at four hospitals in San Diego, California were included. Participating hospitals were: UC San Diego Health System (Hillcrest Medical Center, and Thornton Hospital), Sharp Memorial Hospital, and the Naval Medical Center San Diego. The UC San Diego Health System hospitals and Sharp Memorial Hospital are general hospitals for adults only. Naval Medical Center San Diego is a general hospital with both adult and pediatric departments. Patients with a history of collagen vascular disease, who may also develop coronary aneurysms, were excluded. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions.

Data Acquisition

Demographics, medical history, and laboratory values were obtained via chart review for all included patients. Early family history of coronary artery disease was defined as coronary artery disease in a first degree relative before the age of 60 years or physician-documented positive early family history. Hyperlipidemia was defined as low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol ≥ 160 mg/dL or physician-documented history of hyperlipidemia. Hypertension was defined as a physician-documented history of high blood pressure.

Adjudication of Cases

Coronary angiograms were reviewed by two cardiologists who were blinded to the medical history. The cardiologists assessed each coronary artery for the presence of stenoses (location and percent) and aneurysms (location and size). Characteristics of aneurysms that were considered suggestive of antecedent KD included proximal location and larger size. Clinical characteristics suggestive of antecedent KD in patients with coronary aneurysms included absence of CAD risk factors, age <30 years, Asian or black race, and the absence of significant CAD (stenosis ≥50%) (Table 1).3 CAD risk factors were defined as: diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, current smoking, and family history of premature CAD. Coronary aneurysms were defined based on the Japanese Ministry of Health criteria, as segments for which the internal diameter of a coronary artery segment measured ≥1.5 times that of an adjacent segment.9

Table 1.

Clinical and Angiographic Criteria Suggesting Coronary Aneurysms are Due to Kawasaki Disease

| Criteria: |

|---|

|

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data are presented as percentages; continuous data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were compared using t tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. All statistical tests were two-tailed; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

Over the four year study period, a total of 268 adults under the age of 40 years underwent coronary angiography at one of the 4 study hospitals and met study criteria (n=89 at the two UC San Diego Health System Hospitals; n=111 at Sharp Hospital; and n=68 at Naval Medical Center San Diego). Of these, charts and angiograms were available for review in 261 (97.4%). Demographics of the study population are shown in Table 2. The mean age of patients was 35 years, and 73% were men. About half of the patients had 2 or more CAD risk factors, and nearly 30% had at least 3 risk factors for CAD. Four patients (1.5%) had a known history of KD.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Study Group

| All Subjects | Subjects Unlikely to have KD | Definite or Presumed KD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | (n=261) | (n=248) | (n=13) | p |

| Age (years ± SD) | 35.0 ± 4.6 | 35.1 ± 4.5 | 32.9 ± 4.9 | 0.09 |

| % Male | 72.8 | 71.4 | 100 | 0.02 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | 0.04 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 26.8 | 27.8 | 7.7 | |

| Black | 19.2 | 19.0 | 23.1 | |

| Asian | 8.4 | 7.3 | 30.8 | |

| Hispanic | 19.2 | 20.2 | 0 | |

| Other | 8.0 | 8.5 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 18.4 | 17.2 | 38.5 | |

| Risk Factors (%) | ||||

| Current Smoking | 28.4 | 28.3 | 30.8 | 0.85 |

| Family History of Early CAD | 24.9 | 25.0 | 23.1 | 0.49 |

| Medical History (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 21.8 | 21.8 | 23.1 | 0.96 |

| Hypertension | 46.0 | 48.8 | 30.8 | 0.23 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 46.4 | 46.4 | 46.2 | 0.39 |

| CAD | 14.2 | 13.7 | 23.1 | 0.52 |

| Kawasaki Disease | 1.1 | 0 | 23.1 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory Values (mean ± SD) | ||||

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 112 ± 48 | 111 ± 46 | 149 ± 86 | 0.22 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 38 ± 11 | 39 ± 11 | 32 ± 11 | 0.09 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 156 ± 132 | 157 ± 134 | 137 ± 72 | 0.66 |

Angiographic Findings, CAD Risk Factors, and Prior KD

On review of coronary angiograms, 59% had normal coronary arteries at the epicardial level, 39% had stenosis of at least 50%, and 6% (n=16) had coronary artery aneurysms. One individual had a coronary artery anomaly (anomalous takeoff of the left circumflex coronary artery).

Compared to patients with normal coronary arteries, the 16 patients with aneurysms had a similar prevalence of CAD risk factors (mean number of risk factors 1.9 ± 1.1 in the aneurysm group vs. 1.7 ± 1.3 in the normal group, p=NS). Seven of the 16 patients (44%) with coronary aneurysms had only one or no known CAD risk factors, compared to 50% of those with normal-sized coronary arteries (p=NS). Among the 16 with aneurysms, 5 (31%) had no significant coronary stenosis on angiography.

After all clinical criteria were assessed, 4 of the 16 patients with coronary aneurysms had definite antecedent KD, and 9 had aneurysms presumed to be secondary to KD. Overall, 5.0% of all patients had definite or presumed KD as the etiology of their coronary disease.

Characteristics of the Patients with Coronary Aneurysms

The clinical and angiographic characteristics of the 16 patients with coronary artery aneurysms are shown in Table 3. All 16 of the patients were men, and 4 (25%) had a known childhood history of KD.

Table 3.

Description of 16 Patients with Coronary Aneurysms and Likelihood of Kawasaki Disease (KD) as the Etiology

| # | Age (Yrs) | Sex | Ethnicity | History of KD (Known or Elicited) | # of Cardiac Risk Factors | CAD (≥ 50% Stenosis) | Size of Aneurysm (mm) | Proximal? | Locations of Aneurysms | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21.7 | Male | Asian | Yes | 0 | No | 10 | Yes | All vessels | Definite KD |

| 2 | 29.5 | Male | White | Yes | 1 | Yes | 8 | Yes | LAD, RCA | Definite KD |

| 3 | 34.5 | Male | Asian | Yes | 1 | Yes | 10 | Yes | All vessels; RCA thrombotic | Definite KD |

| 4 | 37.7 | Male | Asian | Yes | 1 | Yes | 7 | Yes | LCx, RCA thrombotic | Definite KD |

| 5 | 33.0 | Male | Black | 1 | No | 12 | Yes | All vessels; LAD thrombotic | Presumed KD | |

| 6 | 36.1 | Male | Black | 2 | Yes | 8 | Yes | LAD, LCx, RCA | Presumed KD | |

| 7 | 34.6 | Male | Unknown | 2 | Yes | 15 | Yes | LM, LAD, LCx | Presumed KD | |

| 8 | 31.0 | Male | Unknown | 4 | Yes | 8 | Yes | LM, LCx | Presumed KD | |

| 9 | 27.8 | Male | Unknown | 1 | No | 7 | No | RCA | Presumed KD | |

| 10 | 38.9 | Male | Black | 2 | No | 7 | Yes | Diagonal, RCA | Presumed KD | |

| 11 | 32.9 | Male | Unknown | 1 | Yes | 7 | Yes | LCx, RCA thrombotic | Presumed KD | |

| 12 | 39.5 | Male | Asian | 2 | Yes | 7 | Yes | LAD, LCx | Presumed KD | |

| 13 | 30.7 | Male | Unknown | 2 | Yes | 6 | Yes | LCx, RCA | Presumed KD | |

| 14 | 33.2 | Male | Hispanic | 3 | Yes | 5 | Yes | All vessels -diffuse | KD Unlikely | |

| 15 | 35.1 | Male | White | 4 | Yes | 6 | Yes | RCA | KD Unlikely | |

| 16 | 38.8 | Male | Iranian | 3 | No | 7 | No | RCA | KD Unlikely |

CAD = coronary artery disease; LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx = left circumflex coronary artery; RCA = right coronary artery.

Cardiac Risk Factors: Diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, current smoking, family history of premature CAD

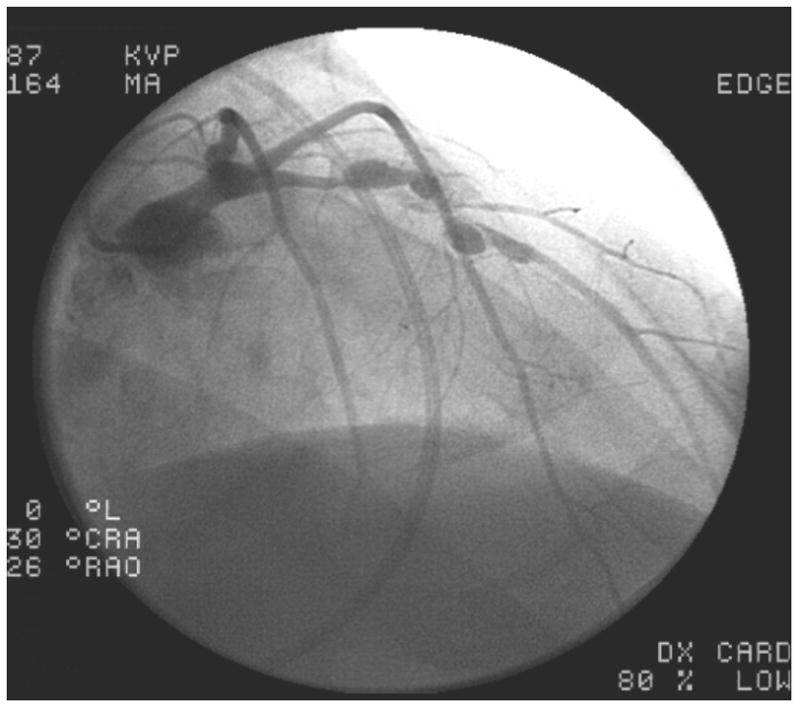

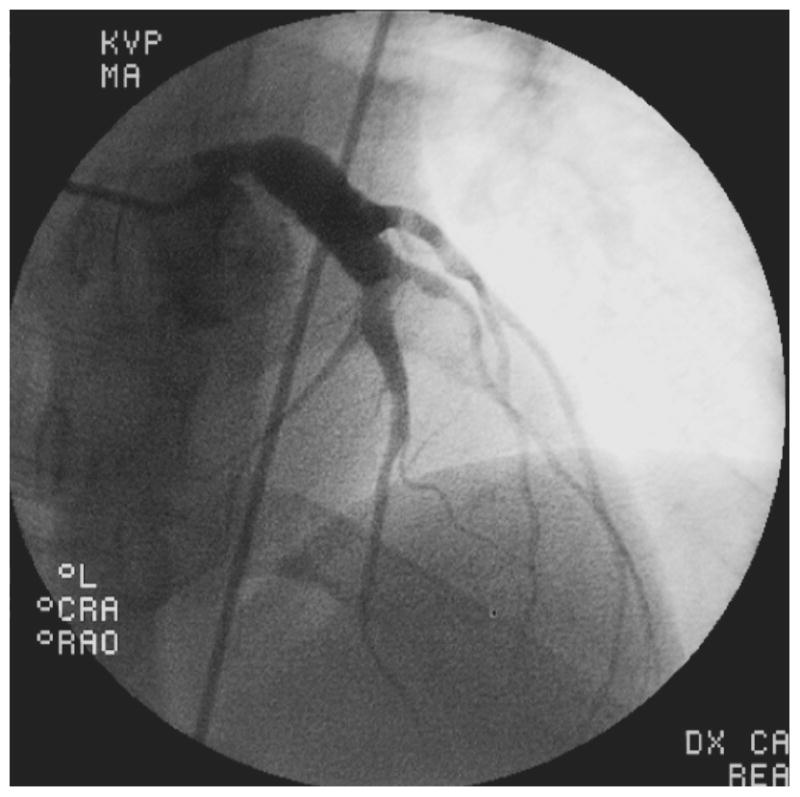

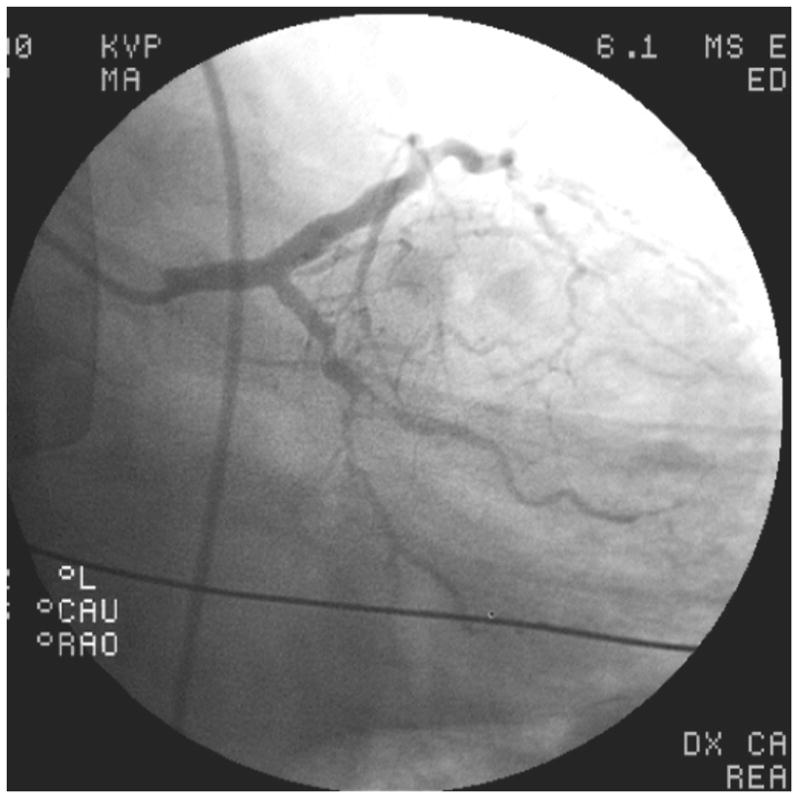

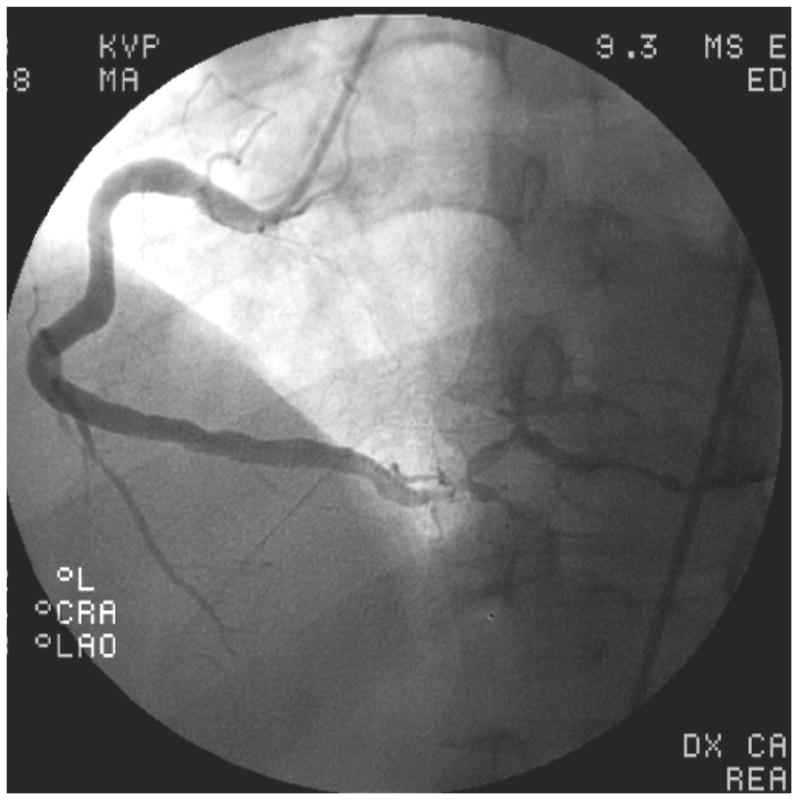

Of the 4 patients with a history of KD, all had coronary aneurysms in two or more vessels, and three had concomitant coronary artery stenosis of at least 50%. These three individuals each had one additional CAD risk factor as well: one patient had a family history of early CAD, one had elevated LDL-cholesterol, and the third smoked cigarettes. Patient #1 was a Vietnamese man with a known history of KD at age 14. He had received IVIG and aspirin on day 13 of illness, and had giant aneurysms already present at the time of diagnosis. A CT angiogram at age 21 raised concerns for arterial occlusion, and he was taken urgently for coronary angiography which revealed patent giant saccular aneurysms of all 3 major epicardial vessels with no stenoses. Left ventriculography revealed moderate left ventricular dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 38%, apical dyskinesis and anterior hypokinesis. Patient #2 was a 29-year old white man with a history of KD at age 3 which was treated with aspirin only since his illness predated the use of IVIG, who presented with symptoms of heart failure and exertional chest pain; he was found to have 4 sequential giant aneurysms of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery with stenoses interspaced between them (Figure 1A). There was a large right coronary artery (RCA) aneurysm as well (Figure 1B). This patient underwent attempted percutaneous coronary intervention for a 90% stenosis of the LAD. He subsequently developed end stage ischemic cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of 10% and ultimately underwent successful cardiac transplantation. Patient #3, a 34-year-old Cambodian man, presented with an acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and had a complete thrombotic occlusion of a giant aneurysm in his proximal RCA; a history compatible with untreated KD at age 6 was elicited retrospectively via parental interview by the interventional cardiologist at the time of angiography. Patient #4 was a 37-year-old Vietnamese man who presented with an acute STEMI with thrombotic occlusion of the RCA. He had giant aneurysms in all 3 major epicardial vessels. Subsequently, a history of KD-compatible illness that went untreated at age 6, while living in a refugee camp in Thailand, was elicited from his parents by the treating team. In addition to the 4 patients with a known history of KD, there were 3 patients in whom antecedent KD was considered highly probable. Patient #5 was a 33-year-old black man with acute chest pain who was found to have giant aneurysms of his left main coronary artery and all 3 major epicardial vessels (Figure 1C & D); there was a large thrombotic occlusion in his mid-LAD which measured 12mm. He had no known history of KD. His only risk factor for CAD was smoking. Patient #6 was a 36-year-old black man with CAD risk factors including hyperlipidemia and hypertension. He presented with chest pain and dyspnea on exertion. Although he had no known history of KD, his angiogram revealed giant aneurysms of the proximal LAD and left circumflex vessels. His RCA was ectatic with a smaller aneurysm of the posterolateral branch measuring 5.2mm. Finally, Patient #7 was a 34-year-old diabetic man with a history of hypertension, who presented with chest pain and was found to have giant proximal aneurysms of his left coronary system. Angiography revealed an 8 mm left main coronary artery, an aneurysmal, calcified left circumflex vessel which was occluded, and a proximal stenosis of the LAD followed by a 15mm aneurysm. His proximal RCA had a smaller aneurysm measuring 5.5mm.

Figure 1.

Images from coronary angiograms of patients with definite or probable Kawasaki Disease as the etiology of their coronary disease. A. Left anterior descending (LAD) artery of Patient #2, showing multiple giant proximal aneurysms, with pre- and post-aneurysm stenotic segments. The distal vessel is spared. B. Right coronary artery (RCA) of Patient # 2, showing a proximal giant aneurysm and sparing of the distal vessel. C. Left coronary arteries of Patient #5, showing giant aneurysmal dilation of the left main artery, extending into the proximal LAD and left circumflex arteries with sparing of the distal vessels. D. RCA of Patient #5, showing aneurysmal segments of the proximal and mid RCA.

In six other patients with coronary aneurysms, antecedent KD was considered possible (Figure 2A). These patients tended to have a higher prevalence of CAD risk factors (mean 2.0 ± 1.1 risk factors per person vs. 1.1 ± 0.7, p=0.11) compared with the patients known or considered to have a history of KD. The mean aneurysm size, though still large, was smaller in this group (6.8 ± 0.7 mm vs. 9.9 ± 2.8 mm, p=0.03), and the aneurysms were less likely to be limited to only the proximal vessels even though most aneurysms did include the proximal vessels.

Figure 2.

Representative images from coronary angiograms of patients with aneurysms considered possibly due to Kawasaki Disease (KD) (A), and unlikely to be due to KD (B–C). A. Left coronary arteries of Patient #10 with possible antecedent KD, showing an aneurysm of the proximal diagonal branch of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery. B. Angiogram of Patient #14, considered unlikely to have antecedent KD, showing proximally dilated left main and LAD arteries with mid-LAD occlusion, and diffuse stenoses in the left circumflex and obtuse marginal arteries. C. Angiogram of Patient #14, considered unlikely to have antecedent KD, showing a diffusely aneurysmal right coronary artery with focal distal stenoses.

The 3 patients with coronary aneurysms who were deemed unlikely to have KD as a causative factor (Figure 2, B and C) had an even higher prevalence of CAD risk factors (mean 3.3 ± 0.6 per person), smaller mean aneurysm size (5.9 ± 0.9 mm), and 2 of 3 had at least 50% narrowing of a coronary vessel.

Discussion

KD was first described in Japanese children by Tomisaku Kawasaki in1967,10 with the first English language publication in 1974.11 Since that time, careful epidemiologic studies in Japan have documented increasing disease incidence.12, 13 The increasing incidence of KD has also been noted in the U.S., but it is difficult to distinguish between increased case ascertainment versus a true increase in numbers of affected children.14–16 Reports of missed KD in young adults began to emerge in the 1980s following Kawasaki’s original publication, but no systematic study of such patients has been published.2, 3 Without a diagnostic test, retrospective diagnosis of missed KD is largely a diagnosis of exclusion.

In the present study, we found that approximately 5% of young adults who undergo coronary angiography to evaluate symptoms concerning for myocardial ischemia may have KD as the underlying cause. Furthermore, all 4 of the patients with a known history of KD had significant aneurysms and a constellation of findings that make it highly probable that their symptoms were due to antecedent KD. Angiographic findings that make antecedent KD likely include proximal aneurysms often with calcification,17 followed by an angiographically normal distal segment.6 Because a history of KD is unknown in many young adults with coronary aneurysms, recent guidelines have recommended that such patients be diagnosed as having sequelae of KD if other diseases causing secondary aneurysms (e.g. collagen vascular disease) are excluded.18 Clinical characteristics that make antecedent KD the likely cause, in addition to a history suggestive of prior KD, include a paucity of traditional cardiac risk factors, a younger age, and an ethnicity known to be at higher risk for KD (Asian or black). Interestingly, smoking has been noted as a prominent additional risk factor among young adults with a history of KD who present with myocardial infarction.7

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate a population of young adults undergoing coronary angiography to estimate the prevalence of KD as a potential etiology. Previously, Kato et al. surveyed adult cardiologists in Japan and retrospectively identified 130 patients ages 20 to 63 with angiographic and clinical findings suggestive of KD.2 Although a definite history of KD could be elicited in only 2, based on their review of the data the authors concluded that all 130 patients likely had KD as the cause of their cardiovascular abnormalities. It should be noted that because KD often occurs in infancy or early childhood, the patient would not have a personal memory of the illness, which could only be obtained through parental interview.

Our finding that 5% of all young adults being evaluated for ischemia may have KD as a cause of their symptoms has important implications for adult cardiologists. The pathology of coronary lesions in patients with a history of KD is very different from the pathology of typical coronary atherosclerosis, and so optimal treatment of each is distinct.19 While typical atherosclerosis is characterized by lipid-laden macrophages, extracellular lipid droplets, and cholesterol crystals, these features are absent in coronary lesions after KD.20 Acutely, KD vasculopathy begins with endothelial cell swelling and subendothelial edema, followed by an intense inflammatory process leading to regions of myointimal proliferation with focal destruction of the internal elastic lamina, medial smooth muscle cell necrosis, and aneurysm formation,21, 22 Over time, myointimal proliferation leads to fibrous scar formation, often with calcification.19, 22

Although optimal therapy of young adults with acute coronary syndromes secondary to KD has not been established, consensus guidelines do exist and the divergent pathology strongly suggests that optimal treatment of KD vasculopathy differs in several key ways from treatment of typical atherosclerosis.18, 23 Acutely, patients with KD who present with myocardial infarction often have a significant thrombus burden in their aneurysmal segments. In the setting of a large thrombus burden, the true diameter of the aneurysmal segment may not be fully appreciated, and intravascular ultrasound is warranted to prevent undersizing of stents. Because some vessels may be heavily calcified, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty may be complicated by the need for very high balloon filling pressures, leading to neoaneurysm formation.24 Rotational atherectomy is the interventional procedure of choice for heavily calcified, stenotic lesions that are not amenable to percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.6, 25 In subacute settings, coronary computed tomography angiography may help as a non-invasive means of identifying the presence and size of aneurysms as well as the presence of thrombus, calcifications, and stenoses. Long-term therapy with systemic anticoagulation, often in addition to antiplatelet agents, is frequently indicated for patients with large coronary aneurysms, and represents another area where treatment differs from that of typical atherosclerosis.18, 26–28

Understandably, most adult cardiologists have little to no experience with treating the complications of KD vasculopathy. KD was not described in the United States until the mid-1970’s.29, 30 Consequently, it is only in the past 10 to 20 years that KD patients have begun to reach young adulthood and come to the attention of adult cardiologists. As more children with a history of KD reach adulthood, adult cardiologists are likely to see increasing numbers of patients with acute and subacute presentations due to coronary sequelae of KD. It has been estimated that there are currently over 24,000 young adults in the United States with a history of KD, including over 8,000 with a history of coronary artery abnormalities; this number is expected to grow by 1,400 individuals each year.6 Thus, increased awareness of the cardiovascular sequelae of KD and their accompanying distinct treatment challenges is more important now than ever before.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. The four hospitals in this study included academic, private, and military institutions, and as such served a diverse population likely to be representative of the population as a whole. In addition, since inclusion criteria were broad and exclusion criteria were very narrow, this study provides an estimate of not just the number of potential cases of cardiac ischemia due to KD, but also of the denominator (i.e. the total number of young adults undergoing evaluation for cardiac ischemia), thereby allowing us to provide a better sense of the magnitude and frequency of this presentation. Our study also has several limitations. San Diego has a relatively high Asian population, which could increase the prevalence of KD compared with other regions. However, there is also a relatively low percentage of African Americans in San Diego, another group with increased propensity to develop KD. Results in other regions could vary, based upon the particular ethnic and racial composition of the population. In addition, the determination of whether the coronary aneurysms and cardiac symptoms in the 16 patients were due to KD was somewhat subjective. However, it was based on known epidemiologic, clinical, and angiographic correlates of KD.2, 3, 7 In addition, our determinations were made in accordance with current guidelines on diagnosing and managing the cardiovascular sequelae of KD, which recommend that young adults with coronary aneurysms be diagnosed as having sequelae of KD in the absence of other known causes of aneurysms.18 Further studies will be needed to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

In summary, coronary sequelae due to KD are responsible for a small but important percentage of young adults who present with myocardial ischemia. Cardiologists should be aware of this special subset of patients who may benefit from medical and invasive management strategies that differ from those used to treat atherosclerotic CAD.

Clinical Summary.

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute, self-limited vasculitis of unknown etiology that occurs most commonly in young children. Diagnosis depends upon recognition of the clinical syndrome since no diagnostic test exists. Thus, the prevalence of individuals with missed KD is unknown. Up to 25% of patients with untreated KD and 5% of those treated with intravenous immunoglobulin will develop coronary artery aneurysms. Persistent aneurysms may remain silent until later in life when myocardial ischemia can occur. The impact of coronary aneurysms and coronary artery damage due to KD, and their prevalence among young adults presenting with symptoms of cardiac ischemia, has not previously been studied. This study systematically evaluated a population of young adults undergoing coronary angiography at 4 hospitals in San Diego to estimate the prevalence of antecedent KD as a potential etiology. The authors found that approximately 5% of young adults who undergo coronary angiography to evaluate symptoms concerning for myocardial ischemia may have coronary artery aneurysms with KD as the underlying cause. Thus, coronary sequelae of KD are responsible for a small but important percentage of young adults who present with myocardial ischemia. As more children with a history of KD reach adulthood, adult cardiologists are likely to see increasing numbers of patients with acute and subacute presentations of coronary sequelae of KD. Cardiologists should be aware of this special subset of patients who may benefit from medical and invasive management strategies that differ from those used to treat atherosclerotic CAD.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported in part by grants from the American Heart Association, National Affiliate (LBD; 09SDG2010231); the National Institutes of Health, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (JCB; RO1-HL69413); and the Macklin Foundation (JCB).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Beiser AS, Burns JC, Bastian J, Chung KJ, Colan SD, Duffy CE, Fulton DR, Glode MP, Mason WH, Cody Meissner H, Rowley AH, Shulman ST, Reddy V, Sundel RP, Wiggings JW, Colton T, Melish ME, Rosen FS. A single intravenous infusion of gamma globulin as compared with four infusions in the treatment of acute Kawasaki syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1633–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106063242305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato H, Inoue O, Kawasaki T, Fujiwara H, Watanabe T, Toshima H. Adult coronary artery disease probably due to childhood Kawasaki disease. Lancet. 1992;340:1127–1129. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93152-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns JC, Shike H, Gordon JB, Malhotra A, Schoenwetter M, Kawasaki T. Sequelae of Kawasaki disease in adolescents and young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato H, Sugimura T, Akagi T, Sato N, Hashino K, Maeno Y, Kazue T, Eto G, Yamakawa R. Long-term consequences of Kawasaki disease. A 10- to 21-year follow-up study of 594 patients. Circulation. 1996;94:1379–1385. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tremoulet AH, Best BM, Song S, Wang S, Corinaldesi E, Eichenfield JR, Martin DD, Newburger JW, Burns JC. Resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin in children with Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2008;153:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon JB, Kahn AM, Burns JC. When children with kawasaki disease grow up myocardial and vascular complications in adulthood. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1911–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuda E, Abe T, Tamaki W. Acute coronary syndrome in adult patients with coronary artery lesions caused by Kawasaki disease: review of case reports. Cardiol Young. 2011;21:74–82. doi: 10.1017/S1047951110001502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senzaki H. Long-term outcome of Kawasaki disease. Circulation. 2008;118:2763–2772. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.749515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Research Committee on Kawasaki Disease. Report of Subcommittee on Standardization of Diagnostic Criteria and Reporting of Coronary Artery Lesions in Kawasaki Disease. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawasaki T. Acute febrile mucocutaneous syndrome with lymphoid involvement with specific desquamation of the fingers and toes in children. Arerugi. 1967;16:178–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawasaki T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, Shigematsu I, Yanagawa H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in Japan. Pediatrics. 1974;54:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, Uehara R, Oki I, Kayaba K, Yanagawa H. Increasing incidence of Kawasaki disease in Japan: nationwide survey. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:287–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, Uehara R, Sadakane A, Chihara I, Aoyama Y, Kotani K, Yanagawa H. Epidemiologic features of Kawasaki disease in Japan: results of the 2007–2008 nationwide survey. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:302–307. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taubert KA, Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Seven-year national survey of Kawasaki disease and acute rheumatic fever. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:704–708. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kao AS, Getis A, Brodine S, Burns JC. Spatial and temporal clustering of Kawasaki syndrome cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:981–985. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31817acf4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holman RC, Curns AT, Belay ED, Steiner CA, Schonberger LB. Kawasaki syndrome hospitalizations in the United States, 1997 and 2000. Pediatrics. 2003;112:495–501. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaichi S, Tsuda E, Fujita H, Kurosaki K, Tanaka R, Naito H, Echigo S. Acute coronary artery dilation due to Kawasaki disease and subsequent late calcification as detected by electron beam computed tomography. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:568–573. doi: 10.1007/s00246-007-9144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of cardiovascular sequelae in Kawasaki disease (JCS 2008)--digest version. Circ J. 2010;74:1989–2020. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-74-0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki A, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Komatsu K, Nishikawa T, Sakomura Y, Horie T, Nakazawa M. Active remodeling of the coronary arterial lesions in the late phase of Kawasaki disease: immunohistochemical study. Circulation. 2000;101:2935–2941. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.25.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naoe S, Takahashi K, Masuda H, Tanaka N. Kawasaki disease. With particular emphasis on arterial lesions. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1991;41:785–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1991.tb01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki A, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Nakazawa M, Yutani C. Remodeling of coronary artery lesions due to Kawasaki disease: comparison of arteriographic and immunohistochemical findings. Jpn Heart J. 2000;41:245–256. doi: 10.1536/jhj.41.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, Shulman ST, Bolger AF, Ferrieri P, Baltimore RS, Wilson WR, Baddour LM, Levison ME, Pallasch TJ, Falace DA, Taubert KA. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;110:2747–2771. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145143.19711.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akagi T. Interventions in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2005;26:206–212. doi: 10.1007/s00246-004-0964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters TF, Parikh SR, Pinkerton CA. Rotational ablation and stent placement for severe calcific coronary artery stenosis after Kawasaki disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;56:549–552. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suda K, Kudo Y, Higaki T, Nomura Y, Miura M, Matsumura M, Ayusawa M, Ogawa S, Matsuishi T. Multicenter and retrospective case study of warfarin and aspirin combination therapy in patients with giant coronary aneurysms caused by Kawasaki disease. Circ J. 2009;73:1319–1323. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suda K, Iemura M, Nishiono H, Teramachi Y, Koteda Y, Kishimoto S, Kudo Y, Itoh S, Ishii H, Ueno T, Tashiro T, Nobuyoshi M, Kato H, Matsuishi T. Long-term prognosis of patients with Kawasaki disease complicated by giant coronary aneurysms: a single-institution experience. Circulation. 2011;123:1836–1842. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.978213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy DM, Silverman ED, Massicotte MP, McCrindle BW, Yeung RS. Longterm outcomes in patients with giant aneurysms secondary to Kawasaki disease. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:928–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melish ME, Hicks RM, Larson E. Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome in the US. Pediatr Res. 1974;8:427A (abstr). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melish ME, Hicks RM, Larson EJ. Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome in the United States. Am J Dis Child. 1976;130:599–607. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1976.02120070025006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]