Abstract

Context

While young racial/ethnic groups are the fastest growing population in the United States, data on alcohol and drug use disorders among adolescents of various racial/ethnic backgrounds are lacking.

Objective

To examine the magnitude of past-year Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV substance use disorders (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, inhalants, hallucinogens, heroin, analgesic opioids, stimulants, sedatives, tranquilizers) among whites, Hispanics, African Americans, Native Americans, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and multiple-race adolescents.

Design

2005–2008 National Surveys of Drug Use and Health.

Setting

Non institutionalized, household adolescents aged 12–17 years.

Main Measures

Substance use disorders were assessed by standardized survey questions administered by the audio computer-assisted self-interviewing method.

Results

Of all adolescents aged 12–17 (N=72,561), 37% used alcohol or drugs in the past year; 8% met criteria for an alcohol or drug use disorder, with Native Americans having the highest prevalence of use (48%) and disorder (15%). Analgesic opioids were the second most commonly used illegal drugs in all racial/ethnic groups, following marijuana; opioid use was comparatively prevalent among Native Americans (10%) and multiple-race adolescents (9%). Among past-year alcohol or drug users (n=27,705), Native Americans (32%), multiple-race adolescents (25%), whites (23%), and Hispanics (21%) had the highest rates of alcohol or drug use disorders. Marijuana was used by adolescents more frequently than alcohol or other drugs, and 26% of marijuana users met criteria for marijuana abuse/dependence. Controlling for adolescents’ age, socioeconomic variables, population density of residence, self-rated health, and survey year, adjusted analyses of adolescent substance users indicated elevated odds of having alcohol and drug use disorders among Native Americans, multiple-race adolescents, whites, and Hispanics compared with African Americans; the latter group did not differ from Asians/Pacific Islanders.

Conclusions

Substance use is widespread among Native-American, multiple-race, white, and Hispanic adolescents. These groups also are disproportionately affected by alcohol and drug use disorders.

Keywords: drug abuse, drug use disorders, multiple race, multiethnic race, prescription drug abuse, racial and ethnic differences, substance use disorder

Introduction

Problematic alcohol and drug use in adolescence has a negative impact on the affected individuals, their families, and society.1 Because psychoactive drugs alter neurotransmission in the brain, repeated use could have long-lasting adverse effects on brain development and overall health.2–4 Early substance use confers a heightened risk for addiction, psychiatric and medical disorders, poor psychosocial functioning, treatment needs, and mortality.1–9 Adolescence marks the period of life with the highest risk for initiating substance use;10 thus, adolescents constitute a high-risk group requiring research to guide prevention efforts and health policymaking. Furthermore, there is a growing need for understanding alcohol and drug use disorders among adolescents of various racial/ethnic backgrounds to track health statistics, plan for and improve health services, and identify vulnerable subgroups for focused intervention. Non-white children and adolescents are the fastest growing population; by 2030, non-whites are projected to represent more than half of the U.S. population under the age of 18 years.11 Thus, the majority of young people at greatest risk to start alcohol or drug use will most likely be from non-white groups. For example, young Hispanics, the fastest growing group in the United States, have an elevated risk for substance use.11–14

While eliminating racial/ethnic disparities in health problems and their treatment is a mission of the National Institutes of Health, scarce data on substance use disorders (SUDs) exist for young non-white groups. Studies of adolescents have focused primarily on substance use among students, and assessments for SUDs are not included in school-based surveys; when studies have examined SUDs, data are frequently limited to alcohol, marijuana, or cocaine, resulting in a lack of data on other drug use disorders.15–19 Additionally, sample sizes of studies are often inadequate for examining young Asians, Native Americans, and multiple-race groups. The 2000 census was the first U.S. census to include the classification of multiple race,12 and SUD data for this group are lacking. Results on “substance use” also are limited for discerning important differences in substance use problems across groups. An improved measure of substance use problems—such as that provided by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–IV (DSM-IV)20—is needed to better inform research, intervention, and health policymaking.

Further, although studies have reported racial/ethnic differences in substance use, findings on racial/ethnic differences in problems related to various substances are inconsistent and sometimes difficult to interpret.15 These discrepancies relate to various definitions of substance use and at-risk groups (the denominators) used.15 Some studies have examined substance use problems in a total sample, while others have compared them among subgroups of substance users. These variations in study designs complicate efforts to make comparisons of substance use problems between racial/ethnic groups and across substance classes. Moreover, U.S. surveys have shown a shifting pattern of substance use. Since around 1999–2000, nonmedical opioid use has increased to become more prevalent than inhalant use among adolescents; during 2002–2009, past-month nonmedical opioid use ranged from 2.3% to 3.2% compared with 1.0–1.3% for inhalant use.10,21–23 Additionally, marijuana use has been rising recently after a few years of decline; alcohol use and cigarette smoking among adolescents have declined.10,24,25 These changing patterns warrant research to identify racial/ethnic groups disproportionally affected by prescription drug or marijuana use and reveal a need to evaluate the comprehensive patterns of SUDs affecting various groups.10,25

In response to the growing population of non-white adolescents, the scarcity of SUD estimates, and shifting patterns of substance use, we examine data from 2005–2008 National Surveys of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) to fill this critical gap in SUD estimates for young racial/ethnic groups. NSDUH is the largest ongoing survey, serving as the primary source for national estimates of substance use and SUDs for the noninstitutionalized U.S. population.10 The selected years used designs allowing use of pooled data to examine alcohol and nine drug use disorders across racial/ethnic groups and to compare the conditional probability of SUDs among adolescent substance users. Multiple years of SUD data assessed by the same instrument help identify the extent of overlooked SUDs (prescription drug use disorders) for understudied groups (Asian, Native-American, multiple-race). To address the limitation of studies with complicated comparisons of racial/ethnic differences due to various denominators or definitions of substance use, we focus on past-year substance use and SUDs, as they are better indicators of recent or active substance use and treatment needs than lifetime measures.

Additionally, we expand from studies of substance use by examining the frequency of each substance used and conditional probabilities of SUDs to characterize use patterns and identify subsets of adolescent users showing elevated odds of having the disorder to better inform etiological efforts. The conditional prevalence of SUDs takes into account substance-specific variations in use by restricting the denominator for each SUD to adolescent users of the corresponding substance, thereby allowing comparisons across substances. To mitigate for the confounding effects on associations between race/ethnicity and substance use status, adolescents’ age, gender, family income, population density of residence (adjusting for potential effects associated with community economic characteristics, drug-using peers, availability of substances), self-rated health (adjusting for potential effects associated with adolescents’ substance use and health status), and survey year are included as control variables.10,14,26–30

Three main questions are addressed:

Are there racial/ethnic differences in one-year prevalence of alcohol and drug use disorders?

Are there racial/ethnic differences in one-year conditional prevalence of alcohol and drug use disorders among past-year adolescent users of each corresponding substance class?

To what extent is racial/ethnic status associated with each SUD among adolescent substance users after controlling for potentially confounding effects of adolescents’ age, gender, family income, population density of residence, self-rated health, and survey year?

Methods

Data source

Data were from the public-use data file of the 2005–2008 NSDUH, the only survey designed to provide ongoing national estimates of substance use and SUDs in the United States.31,32 The target population includes residents of households from the 50 states (including shelters, rooming houses, and group homes) and civilians residing on military bases. Participants are selected by multistage area probability methods to ensure that each independent cross-sectional sample is representative of persons aged ≥12 years. The design oversampled people aged 12–25 years; because of a large sample size, there was no need to oversample racial/ethnic groups as was done prior to 1999.31,32 Detailed information on sample designs is provided by Morton et al.33

Prospective respondents are assured that their names will not be recorded and their responses will be kept strictly confidential. All study procedures and protections are carefully explained. For adolescents aged 12–17 years, the field interviewer first seeks verbal consent from their parents/guardians. Once parental permission is granted, field interviewers then approach the adolescents and obtain their agreement to participate in the study. Parents are asked to leave the interview setting to ensure the confidentiality of their children’s responses.

The interview uses computer-assisted interviewing to increase the likelihood of valid respondent reports of substance use behaviors.31,32 Sociodemographic questions are administered by interviewers using computer-assisted personal interviewing. Other questions of a sensitive nature (substance use, SUDs, health) are administered with audio computer-assisted self-interviewing, which provides respondents with a highly confidential means of responding to questions to increase honest reporting of sensitive behaviors. Respondents read questions on the computer screen, or questions are read to them through headphones, and they enter responses directly into a computer provided by the interviewer.

From 2005–2008, approximately 67,500 unique persons aged ≥12 years were interviewed annually (weighted interviewing response rates for adolescents aged 12–17: 85–87%).31,32 This study examined adolescents aged 12–17 years (n=18,678 in 2005; n=18,314 in 2006; n=17,727 in 2007; n=17,842 in 2008). Four years of data (N=72,561) were pooled to allow for the detection of differences in SUDs between racial/ethnic groups.

Study variables

Substance use

The survey asked each respondent about his/her use of alcohol and nine drug classes (illicit use of marijuana/hashish, cocaine/crack, heroin, or hallucinogens; inhalant use; nonmedical use of prescription analgesic opioids, stimulants/amphetamines, tranquilizers, sedatives). Nonmedical use was defined as use without a prescription or for the experience or feeling the drugs caused; use of over-the-counter drugs and legitimate use of prescription drugs were not included.22, 31,32 Alcohol and drug classes were assessed by discrete questions in 10 different sections. Each included a detailed description of the substance class and a list of substances belonging to the class. For nonmedical use, respondents were provided with pill cards showing color pictures of tablets for analgesic opioids, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives (the computer screen prompts the respondent to obtain pill cards from the interviewer). To determine the extent of co-usage of alcohol and drugs, users of both alcohol and a drug were categorized.

DSM-IV SUDs (abuse, dependence)

Respondents who reported alcohol or drug use in the past year were asked a set of structured, substance-specific questions designed to operationalize DSM-IV criteria for abuse (role interference, hazardous use, problems with the law, relationship problems) and dependence (tolerance, withdrawal, taking larger amounts/longer, inability to cut down, time spent using the substance, giving up activities, continued use despite problems) in the past year.20,31,32 Dependence on a given substance class included users who met ≥3 dependence criteria for that class in the past year; abuse applied to users who met ≥1 abuse criterion but did not meet criteria for dependence on that substance class; abuse and dependence were mutually exclusive.20,31,32 Assessments were adopted from questions used in the National Comorbidity Survey; as part of an ongoing process to improve the survey, diagnostic questions were cognitively tested to determine how well they were understood by respondents, evaluated by experts to determine how well the questions captured the DSM-IV criteria, and modified for DSM-IV criteria.34 SUD questions were implemented and assessed by the computer-assisted self-interviewing method.

Sociodemographics

Adolescents’ age, gender, self-reported race/ethnicity (white, 59.9%; African-American, 15.3%; Native-American [American Indian/Alaska Native], 0.6%; Asian/Pacific Islander, 4.4%; multiple-race, 1.7%; Hispanic, 18.2%), total family income, population density of residence, and self-rated health were examined.12,26–30,32 Population density was based on 2000 census data and the June 2003 Core-based Statistical Area (CBSA) classifications, and was categorized into large-metro (≥1 million population), small-metro (<1 million population), and non-metro (not in a CBSA). Due to the nature of a national sample, population density of residence, a proxy for community location, was included as a control variable. Self-rated health (fair/poor versus excellent/very good/good) was assessed by the widely supported measure of general health (“Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”), which was associated with substance use.28–30

Data analysis

The distribution of race/ethnicity by survey year and racial/ethnic differences in sociodemographics were determined by χ2. Prevalence rates of substance use and SUDs by race/ethnicity were determined. Conditional prevalence rates of SUDs among adolescent users of each substance class were compared by race/ethnicity. To evaluate conditional rates of SUDs among substance users, the frequency of substance use among past-year users was calculated. Logistic regression analyses estimated associations between race/ethnicity and each SUD among adolescent users of that substance. Age, gender, family income, population density of residence, self-rated health, and survey year were adjusted in the analyses to mitigate for their confounding effects on associations between race/ethnicity and SUD.10,12,26–30 Analyses were conducted with SUDAAN, taking into account NSDUH’s complex designs, such as weighting and clustering.35 All results are weighted figures except for sample sizes (unweighted).

Results

Demographic characteristics

There were no yearly differences in the distribution of racial/ethnic groups (N=72,561). There were more adolescents aged 12–13 years in the multiple-race and Hispanic groups than in the other groups (online-only eTable 1). More African Americans (64%), Native Americans (56%), and Hispanics (57%) were in the lower income group (<$40,000) than other groups (26–38%). The majority of African Americans (64%), Asians/Pacific Islanders (76%), and Hispanics (64%) resided in large-metro areas, while Native Americans were more likely to reside in non-metro areas (34%). More African Americans (5%), Native Americans (7%), and Hispanics (5%) reported poor/fair health than whites (3%).

Prevalence of substance use

Overall, 37% (n=27,705) of adolescents used alcohol or drugs in the past year (any alcohol, 32%; any illicit/nonmedical drugs, 19%; alcohol and drugs, 15%). Of all drug classes, use of marijuana (13% of all adolescents) or analgesic opioids (7%) was more prevalent than use of other drugs (0.1–4%). Native Americans had the highest prevalence of alcohol or drug use (48%); Native Americans (21%), multiple-race adolescents (18%), and whites (16%) had a higher prevalence of using both alcohol and drugs than other groups (Table 1). For all racial/ethnical groups, there was an age-related increase in alcohol and/or drug use (online-only eTable 2).

Table 1.

One-year prevalence (%) of substance use among adolescents aged 12–17 years by race or ethnicity (N=72,561)

| Prevalence, % (95% CI) | White | African- American | Native- American | Asian or Pacific Islander | Multiple-race | Hispanic | χ2 (5)*<.01 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Sample size | N=43,778 | N=10,109 | N=1122 | N=2481 | N=2814 | N=12,257 | |

| Alcohol or drug | 39.2 (38.7–39.7) | 32.2 (30.9–33.5) | 47.5 (42.2–52.9) | 23.7 (21.5–26.0) | 36.4 (33.6–39.3) | 36.7 (35.3–38.0) | 257.1* |

| Alcohol and drug | 16.2 (15.8–16.5) | 11.1 (10.3–12.0) | 20.5 (16.2–25.5) | 6.8 (5.5–8.4) | 18.1 (16.1–20.3) | 13.9 (12.8–14.9) | 240.3* |

| Alcohol | 35.3 (34.8–35.9) | 24.8 (23.6–26.0) | 37.0 (31.3–42.9) | 18.9 (17.2–20.7) | 31.1 (28.8–33.6) | 32.2 (30.8–33.6) | 436.8* |

| Any druga | 20.0 (19.6–20.4) | 18.6 (17.6–19.7) | 31.0 (26.6–35.8) | 11.7 (10.0–13.6) | 23.3 (20.8–26.1) | 18.3 (17.2–19.5) | 125.2* |

|

| |||||||

| Marijuana | 13.9 (13.5–14.4) | 12.2 (11.3–13.1) | 23.5 (19.4–28.2) | 5.7 (4.5–7.2) | 16.3 (14.4–18.4) | 11.8 (10.9–12.7) | 163.8* |

| Inhalants | 4.5 (4.4–4.8) | 2.9 (2.5–3.4) | 5.3 (3.3–8.3) | 2.8 (2.0–4.0) | 4.8 (3.5–6.6) | 4.4 (3.8–5.0) | 61.8* |

| Cocaine | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 3.7 (2.0–6.8) | 0.6 (0.4–1.2) | 2.3 (1.5–3.5) | 1.6 (1.4–2.0) | 285.5* |

| Hallucinogens | 3.2 (3.0–3.4) | 0.7 (0.6–1.0) | 4.5 (2.8–7.1) | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) | 4.6 (3.4–6.1) | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | 304.0* |

| Analgesic opioids | 7.5 (7.2–7.8) | 5.5 (4.9–6.1) | 9.7 (7.4–12.6) | 4.3 (3.3–5.4) | 8.8 (7.2–10.8) | 5.6 (5.0–6.4) | 120.72* |

| Stimulants | 2.2 (2.0–2.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 2.4 (1.5–3.7) | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 1.9 (1.3–2.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 114.5* |

| Tranquilizers | 2.6 (2.4–2.8) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 2.5 (1.6–4.1) | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 2.6 (1.6–4.3) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 262.4* |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Results for heroin and sedative use (less than 1% of the sample) are not reported due to a small sample size of users.

Any drug includes any of the following: marijuana, inhalants, cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, analgesic opioids, stimulants, sedatives, and tranquilizers.

Prevalence of SUDs

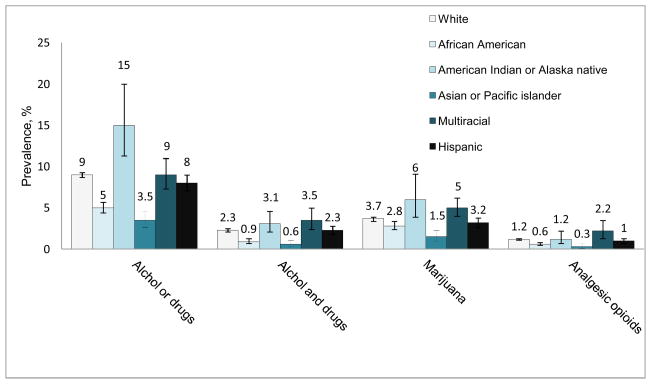

Among all adolescents aged 12–17 years, 8% (n=6166) met criteria for alcohol or drug use disorders, and 2% met criteria for both alcohol and drug use disorders in the past year (any alcohol use disorder, 5%; any drug use disorder, 5%). Marijuana (3.4%) and analgesic opioid (1.2%) use disorders were the most prevalent drug use disorders. Prevalence of various SUDs is summarized in online-only eTable 3. Native Americans had the highest prevalence of alcohol or drug use disorders (15%), followed by whites (9%), multiple-race adolescents (9%), Hispanics (8%), African Americans (5%), and Asians/Pacific Islanders (4%) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

One-year prevalence of substance use disorders (abuse or dependence) among adolescents aged 12–17 years by race or ethnicity (N=72,561). Lines extending from bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimates.

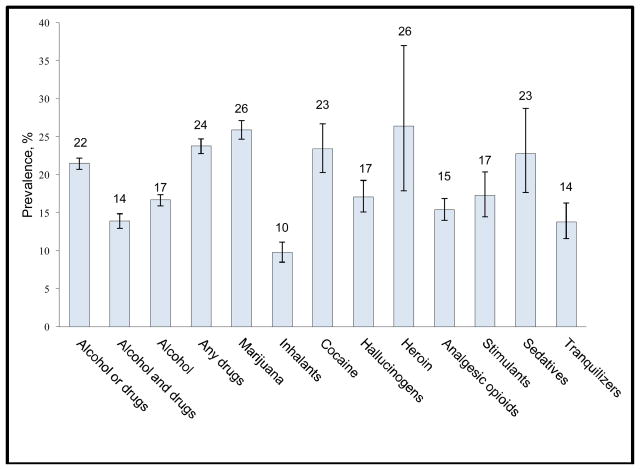

Conditional prevalence of SUDs among substance users

Conditional rates of SUDs (prevalence of SUDs among users of the corresponding substance), suggesting the substance-specific liability for having a SUD among users, showed that 21% of past-year alcohol or drug users met criteria for a SUD (Fig. 2). Marijuana (26% of marijuana users), heroin (26%), cocaine (23%), and sedative (23%) use demonstrated similarly high conditional rates. Among alcohol users, 17% had an alcohol use disorder.

Fig 2.

One-year conditional prevalence of substance use disorders (abuse or dependence) among adolescent substance users aged 12–17 years by substance used (N=27,705). Lines extending from bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimates.

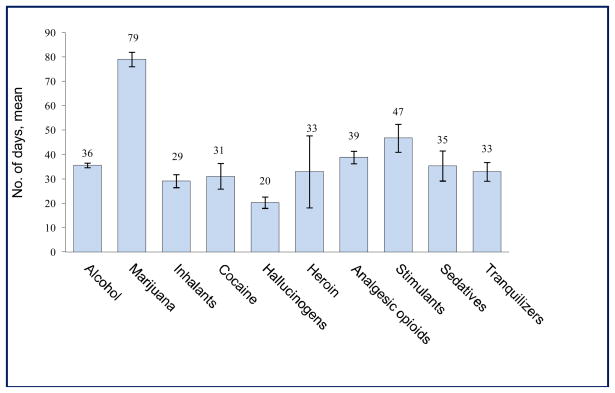

Substance-specific frequency of use helps interpret conditional rates (Fig. 3). Marijuana users on average spent the greatest number of days using the drug (mean=79 days/year), followed by stimulant users (mean=47 days/year), analgesic opioid users (mean=39 days/year), alcohol users (mean=36 days/year), sedative users (mean=35 days/year), heroin users (mean=33 days/year), tranquilizer users (mean=33 days/year), cocaine users (mean=31 days/year), inhalant users (mean=29 days/year), and hallucinogen users (mean=20 days/year). Substance-specific frequency of use by race/ethnicity is reported in online-only eTable 4.

Fig 3.

Mean number of days using the substance in the past year among adolescent past-year users aged 12–17 years by substance used (N=27,705). Lines extending from bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimates.

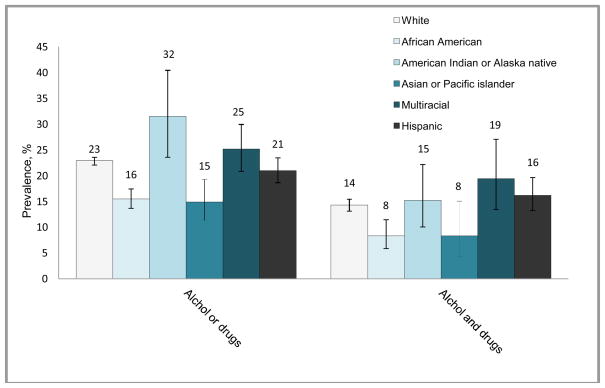

Racial/ethnic differences in conditional prevalence of SUDs

There were notable racial/ethnic differences in the conditional prevalence of various SUDs (online-only eTable 5). Among alcohol or drug users (n=27,705), Native Americans (32%) and multiple-race adolescents (25%) exhibited comparatively high conditional rates of any SUD (Fig. 4). Native-American users had a higher conditional rate of any SUD than whites (23%), Hispanics (21%), African Americans (16%), and Asians/Pacific Islanders (15%). Multiple-race adolescents (19%), Hispanics (16%), and whites (14%) had a higher conditional rate of comorbid alcohol/drug use disorders than African Americans (8%).

Fig 4.

One-year conditional prevalence of substance use disorders (abuse or dependence) among adolescent substance users aged 12–17 years by race or ethnicity (N=27,705). Lines extending from bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimates.

Conditional prevalence of abuse versus dependence among substance users

In response to recent findings showing that nonwhite adults are more likely than whites to have dependence than abuse,36 conditional rates of abuse were distinguished from conditional rates of dependence to discern whether dependence disproportionately affected nonwhites (online-only eTable 6). Among alcohol users, whites (11% vs. 7%, P<.05) and Hispanics (10% vs. 7%, P<.05) were more likely to have alcohol abuse than to have alcohol dependence. Among any drug users, Asians/Pacific Islanders (13% vs. 4%, P<.05) and multiple-race adolescents (18% vs. 9%, P<.05) were more likely to have drug dependence than abuse. White inhalant users were more likely to have inhalant abuse than inhalant dependence (7% vs. 3%, P<.05). Given the scarcity of information about substance-using multiple-race adolescents, their demographic characteristics were explored (online-only eTable 7).

Adjusted odds ratios of SUDs among substance users

Finally, logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether substance-using whites, Native Americans, multiple-race adolescents, or Hispanics showed a higher likelihood of having SUDs than substance-using African Americans while adjusting for age, gender, family income, population density, self-rated health, and survey year (online-only eTable 8). Whites, Native Americans, multiple-race adolescents, and Hispanics had greater odds than African Americans of having alcohol, any drug, and comorbid alcohol/drug use disorders (AOR ranged from 1.35 to 3.36). Multiple-race adolescents (AOR=2.42, 95% CI=1.21–4.81), whites (AOR=1.46, 95% CI=1.02–2.07), and Hispanics (AOR=1.63, 95% CI=1.07–2.49) also had greater odds than African Americans of having an analgesic opioid use disorder. These analyses also showed an age-related increase in alcohol use disorders (AOR=0.45, 95% CI=0.37–0.54 for ages 12–13 years; AOR=0.72, 95% CI=0.66–0.79 for ages 14–15 years) and any drug use disorders (OR=0.36, 95% CI=0.29–0.44 for ages 12–13 years; AOR=0.83, 95% CI=0.74–0.93 for ages 14–15 years) compared with those aged 16–17 years. Poor/fair health was associated with increased odds of any SUD (AOR=1.60, 95% CI=1.39–1.86), comorbid alcohol/drug disorders (AOR=1.36, 95% CI=1.09–1.70), or any drug use disorder (AOR=1.69, 95% CI=1.44–2.00). Large-metropolitan residence was associated with reduced odds of alcohol use disorders compared with non-metropolitan residence (AOR=0.83, 95% CI=0.70–0.99).

Finally, we explored whether the association between race/ethnicity and SUD might be influenced by differences in frequency of use across racial/ethnic groups by adjusting the frequency of use of the corresponding substance for each model. All results showed minimal changes on AORs.

Discussion

This study documents national estimates of past-year SUDs among adolescents aged 12–17 years. The findings should prove useful to concerned citizens, health professionals, researchers, and health policy experts. First, past-year alcohol or drug use is widespread (37%), and about one in 12 adolescents self-reported having a SUD, with Native Americans showing the highest prevalence of use and disorders. Second, analgesic opioids have replaced inhalants as the second most commonly used drug (following marijuana), and analgesic opioid use disorders comprise the second most prevalent illicit drug use disorder. Third, close to one fourth of adolescent alcohol or drug users met DSM-IV criteria for a SUD, and users of marijuana, heroin, cocaine, or sedatives showed an elevated rate of abuse or dependence on these drugs. Fourth, marijuana was used by adolescents more frequently than alcohol or other drugs. Fifth, Native Americans, multiple-race adolescents, whites, and Hispanics are disproportionately affected by SUDs.

High rates of SUDs among multiple-race, Native-American, white, and Hispanic adolescents

Prior school-based studies have not assessed SUDs; prescription drug problems were not a major concern, and data for the multiple-race group were not available.17,18,37 The growing size of racial/ethnic groups plus the elevated rate of prescription drug use problems necessitate updated and systematic research to discern intervention needs across these groups.11,13,38 This study expands from earlier studies by including school dropouts and multiple-race adolescents, examining SUDs to improve measures of substance use burden and presenting new data on all available SUDs to make direct comparisons of indicators of intervention needs across racial/ethnic groups. In addition to supporting a high prevalence of substance use among Native Americans, whites, and Hispanics,17,18,37 multiple-race adolescents were found to have the second highest prevalence of alcohol use (following whites) and any drug use (following Native Americans). Close to one tenth of multiple-race adolescents self-reported having a SUD, and one fourth of substance-using multiple-race adolescents exhibited a SUD. These estimates were as high as those for Native Americans, whites, and Hispanics. These four groups are disproportionately affected by symptoms of SUDs.

When distinguishing abuse from dependence,36 drug-using multiple-race adolescents exhibited a higher prevalence of dependence than abuse, suggesting that substance use problems could be a unique challenge for research and intervention as this population grows.11,12 Particularly, while substance use is influenced by multiple individual (depression, delinquency), family (poor parenting), peer, school (location), and community (neighborhood deterioration) domains,39–42 research also has identified cultural-specific risk (greater acculturation) and protective correlates (cultural pride, racial identity) for substance use, thus suggesting that for interventions to be effective, cultural-specific issues should be addressed.13,14,43–45 However, cultural-related factors have yet to be investigated for multiple-race adolescents. About 2% of the U.S. population are of multiple races, which includes three subgroups of similar size (white/black, white/Native-American, white/Asian) and a very small subgroup self-identifying 3+ races.46 Heterogeneous cultural backgrounds of multiple-race individuals emphasize the need for multi-disciplinary approaches to disentangle cultural-related factors that can guide prevention and treatment.12,14,47

Native-American adolescents require concerted research and intervention efforts

Another concern is the high rate of SUDs among Native Americans. Consistent with earlier studies,17,37,48 Native Americans show the highest prevalence of alcohol or drug use (48%). We found Native Americans reporting the highest rate of SUDs (15%); among substance-using Native Americans, 32% met criteria for a SUD. In a sample of 651 indigenous adolescents aged 13–15 years, Whitbeck et al.49 also found that 12.7% self-reported having a past-year alcohol use disorder, and 15.4% had a past-year marijuana use disorder. However, there is a scarcity of research on young Native Americans who use addiction treatment.50 Given that this population is generally younger (39% are under 20 years) and poorer than other racial/racial groups,51 young Native Americans have great need for intervention to reduce burdens from substance use. There are 562 federally recognized Indian tribes in the United States; the cultural diversity and geographic dispersion of these tribes have important implications for research and service provision that require research and policy support to develop culturally appropriate interventions to improve their health.52–54

Marijuana and opioids constitute the primary drugs of abuse

The results also support rising concerns about adolescent marijuana use.25 Marijuana use disorders constituted 74% of all illicit/nonmedical SUDs, and 26% of marijuana users exhibited a marijuana use disorder, which, along with heroin, cocaine, and sedatives, demonstrated the highest conditional rate of SUD. This high rate can be related to frequency of use as marijuana users, on average, spent the greatest number of days using the drug compared with other substance users. This is the first known study to present such findings for all substance classes, and it reveals cause for concern due to the large number of past-year marijuana users (13% of all adolescents), a recent increase in marijuana use, increased levels of potency, and potential adverse effects on adolescents’ health and subsequent productivity.24, 25,55,56 Research is needed to closely monitor marijuana use and associated disorders among adolescents and identify prevention programs that truly work.

Lastly, analgesic opioids constitute the second most commonly used illicit drug in all racial/ethnic groups, with Native Americans, multiple-race adolescents, and whites showing comparatively high rates of use. The large sample helped identify analgesic opioid-using multiple-race adolescents, whites, and Hispanics exhibiting elevated odds of opioid use disorders. Compared with results from earlier studies, findings support an elevated rate of nonmedical opioid use and opioid-related problems across various racial/ethnic groups.17,37,48 This finding also is consistent with others showing that one fourth of nonmedical analgesic opioid users aged 12–17 years had never used other illicit/nonmedical drugs,22 and that adolescents have generally considered analgesic opioids safer and easier to get than illicit drugs and reported parents’ medicine cabinets, family members, or friends as primary sources.57,58 Unfortunately, opioids are among the most addictive and lethal drugs when used improperly.59,60 Clearly, educational or prevention interventions should incorporate effective messages about health risk for nonmedical use/abuse of prescription drugs, and screening for nonmedical drug use should be considered for high-risk adolescents.

Limitations and strengths

These findings should be interpreted with caution. NSDUH relies on self-reports, which can be influenced by memory error and under-reporting. Like other surveys, SUDs in NSDUH are based on fully standardized questions designed to operationalize DSM-IV criteria for SUDs; these rates are self-reported estimates, not clinical diagnoses. Of note, NSDUH-based past-year prevalence of SUDs (alcohol or drug) among adults in 2000 (6.7%) resembled the prevalence of SUDs (7.4%) among adults in the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey.34 Findings also do not apply to institutionalized or homeless adolescents, who were not included in NSDUH. Nicotine dependence is not included because it was not based on DSM-IV criteria; hence, adolescents’ SUD problems are greater than our findings have suggested. This study also does not address the influence of community-level poverty or intra-ethnic differences (e.g., differences among Hispanic groups) in SUDs as detailed measures are not available.13,39,43,61 Given the increasing cultural diversity of the U.S. population, the availability of specific racial/ethnic groups and community-level poverty in future NSDUH datasets would make it possible to monitor disparities in SUDs for heterogeneous racial/ethnic groups.

NSDUH also has noteworthy strengths. These results have a higher level of generalizability than those of a regional sample due to high response rates and the large sample consisting of students and nonstudents/school dropouts. The proportion of nonstudents/school dropouts among adolescents aged 16–17 in this sample (3.8%) was similar to the proportion of dropouts among U.S. public high school students (3.9%).62 While the U.S. census does not provide detailed information of racial/ethnic groups for adolescents aged 12–17, this study’s distributions of Native-American (0.6% vs. 0.7%), Asian/Pacific Islander (4.4% vs. 4.4%), and multiple-race (1.7% vs. 1.6%) groups resembles distributions of all ages of these groups in the U.S.46

Further, based on continuous research efforts and enhancements to improve national SUD estimates, NSDUH uses the most sophisticated survey methods available to improve the quality of self-reported data (computer-assisted self-administration interviewing and anonymous data collection to enhance privacy, detailed probes, color pictures of prescription drugs to augment assessments for substance use).31 A large reliability study found substantial (for abuse/dependence questions) to nearly perfect (for cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use questions) response agreement for key NSDUH measures;63 another NSDUH validity study revealed high agreement between self-reported use and urine drug test results (tobacco, 84.6%; marijuana, 89.8%; cocaine, 95.5%).64 NSDUH’s trend data on various drug use patterns among adolescents are remarkably consistent with trend data from Monitoring the Future.10,31 Given the growing diversity and size of the young population and the scarcity of SUD indicators, this study makes a unique contribution by providing new information to elucidate the magnitude of illicit/prescription drug use disorders for understudied Asians/Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, Hispanics, and African Americans.

Conclusions

Native Americans have the highest prevalence of substance use and SUDs, adding to evidence that young Native Americans are a very vulnerable group facing numerous stressors, trauma, and health disparities (e.g., highest rate of suicide, underfunded systems of care, lack of access to appropriate care).65 Results highlight a critical need for intervention to reduce their burdens from substance use and for policies to address presently underfunded systems of care and improve infrastructures linking behavioral and primary healthcare services.54,65 Additionally, high rates of substance use and SUDs among multiple-race adolescents provide a rationale for including them in research analysis and reporting findings as appropriate. Further, while healthcare providers who regularly see adolescents for periodic checkups can play a critical role in screening for substance use and early intervention, substantial barriers to recommended practices exist, and research is needed to identify incentives and means to promote screening and timely intervention.66,67 Finally, many addiction treatment programs either exclude adolescents from treatment (e.g., program policies) or integrate adolescents into programs serving adults. Even within adolescent-specific programs, key elements for effective treatment are often inadequately addressed, and a lack of cultural competence is identified as a major gap as insensitivity to cultural differences can limit the ability to treat and retain minority adolescents.14,68–70 Taken together, these findings call for efforts to identify and expand prevention measures that are culturally effective and address the quality and acceptability of treatment for adolescents with substance use problems.67,70

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This article was made possible by grants from the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (R33DA027503, R01DA019623, and R01DA019901 to L-T Wu; HHSN271200522071C to DG Blazer; K05DA017009 and U10DA013043 to GE Woody). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive provided the public use data files for NSDUH, which was sponsored by the Office of Applied Studies of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The National Institutes of Health had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Data analyses were performed by L-T Wu and C Yang. L-T Wu had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We thank Amanda McMillan for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Ethical approval

This work was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Conflicts of interest disclosures

GE Woody is a member of the RADARS post-marketing study scientific advisory group, whose job is to assess abuse of prescription medications. Denver Health administers RADARS, and pharmaceutical companies support its work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, Marlatt GA, Sturge J, Rehm J. Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use. Lancet. 2007;369(9570):1391–1401. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60369-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brick J. Handbook of the Medical Consequences of Alcohol and Drug Abuse. New York: The Haworth Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuckit MA. Comorbidity between substance use disorders and psychiatric conditions. Addiction. 2006;101 (Suppl 1):76–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIH PubNo. 07-5605. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [Accessed January 13, 2011.]. Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/ScienceofAddiction/sciofaddiction.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brook JS, Richter L, Rubenston E. Consequences of adolescent drug use on psychiatric disorders in early adulthood. Ann Med. 2000;32(6):401–407. doi: 10.3109/07853890008995947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark DB, Martin CS, Cornelius JR. Adolescent-onset substance use disorders predict young adult mortality. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(6):637–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Sullivent EE., 3rd Age of alcohol use initiation, suicidal behavior, and peer and dating violence victimization and perpetration among high-risk, seventh-grade adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):297–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandel DB, Johnson JG, Bird HR, Weissman MM, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Regier DA, Schwab-Stone ME. Psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders: findings from the MECA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):693–699. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gfroerer JC, Epstein JF. Marijuana initiates and their impact on future drug abuse treatment need. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54(3):229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NSDUH Series H-39, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4609. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day JC. Population Projections of the United States by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1995 to 2050, US Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1996. pp. 25–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mays VM, Ponce NA, Washington DL, Cochran SD. Classification of race and ethnicity: implications for public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volkow ND. Hispanic drug abuse research: challenges and opportunities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84 (Suppl 1):S4–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szapocznik J, Prado G, Burlew AK, Williams RA, Santisteban DA. Drug abuse in African-American and Hispanic adolescents: culture, development, and behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:77–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galea S, Rudenstine S. Challenges in understanding disparities in drug use and its consequences. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 3):iii5–iii12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner LA, Valdez A, Vega WA, de la Rosa M, Turner RJ, Canino G. Hispanic drug abuse in an evolving cultural context: an agenda for research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84 (Suppl 1):S8–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace JM, Jr, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM. Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use: racial and ethnic differences among U.S. high school seniors, 1976–2000. Public Health Rep. 2002;117 (Suppl 1):S67–S75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beauvais F, Oetting ER. Variances in the etiology of drug use among ethnic groups of adolescents. Public Health Rep. 2002;117 (Suppl 1):S8–S14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kandel D, Chen K, Warner LA, Kessler RC, Grant B. Prevalence and demographic correlates of symptoms of last year dependence on alcohol, nicotine, marijuana and cocaine in the U.S. population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44(1):11–29. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NHSDA Series H-13, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 01-3549. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2001. Summary of Findings from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Patkar AA. Non-prescribed use of pain relievers among adolescents in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1–3):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu LT, Ringwalt CL, Mannelli P, Patkar AA. Prescription pain reliever abuse and dependence among adolescents: a nationally representative study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(9):1020–1029. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eed4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Non-medical Marijuana III: Rite of Passage or Russian Roulette? New York: The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2008. [Accessed January 13, 2011.]. Available at: http://www.casacolumbia.org/articlefiles/380-Non-Medical_Marijuana_III.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman J, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2010. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson JM, Donnermeyer JF. Urbanity, rurality, and adolescent substance use. Crim Justice Rev. 2006;31(4):337–356. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA. A multilevel analysis of neighborhood context and youth alcohol and drug problems. Prev Sci. 2002;3(2):125–133. doi: 10.1023/a:1015483317310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith PM, Glazier RH, Sibley LM. The predictors of self-rated health and the relationship between self-rated health and health service needs are similar across socioeconomic groups in Canada. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(4):412–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vingilis E, Wade TJ, Adlaf E. What factors predict student self-rated physical health? J Adolesc. 1998;21(1):83–97. doi: 10.1006/jado.1997.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker T. Factors associated with American Indian teens’ self-rated health. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2004;11(3):1–19. doi: 10.5820/aian.1103.2004.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. NSDUH Series H-36, DHHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. DHHS Publication No. SMA 07-4293, NSDUH Series H-32. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morton KB, Chromy JR, Hunter SR, Martin PC. Prepared for the 2005 Methodological Resource Book. Prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, under contract no. 283-2004-00022. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2006. 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Sample Design Report. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Epstein JF. DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3642, Analytic Series A-16. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2002. Substance Dependence, Abuse, and Treatment: Findings from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN User’s Manual, Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasin DS, Hatzenbueler M, Smith S, Grant BF. Co-occurring DSM–IV drug abuse in DSM–IV drug dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80(1):117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bachman JG, Wallace JM, Jr, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Kurth CL, Neighbors HW. Racial/ethnic differences in smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use among American high school seniors, 1976–89. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(3):372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manchikanti L. National drug control policy and prescription drug abuse: facts and fallacies. Pain Physician. 2007;10(3):399–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF, Deffenbacher JL. Primary socialization theory. The influence of the community on drug use and deviance. III. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33(8):1629–1665. doi: 10.3109/10826089809058948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jessor R. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. In: Jessor R, editor. New Perspectives on Adolescent Risk Behavior. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. [Accessed January 15, 2010.];National survey of American attitudes on substance abuse XV: teens and parents. Available at: http://www.casacolumbia.org/upload/2010/20100819teensurvey.pdf.

- 43.Delva J, Wallace JM, Jr, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. The epidemiology of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban American, and other Latin American eighth-grade students in the United States: 1991–2002. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(4):696–702. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu M, Stiffman AR. Culture and environment as predictors of alcohol abuse/dependence symptoms in American Indian youths. Addict Behav. 2007;32(10):2253–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaska natives: incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Rep. 2002;117 (Suppl 1):S104–S117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed March 16, 2011.];United States ACS demographic and housing estimates: 2005–2009 data set: 2005–2009 American Community Survey 5-year estimates; survey: American Community Survey. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-qr_name=ACS_2009_5YR_G00_DP5YR5&-ds_name=ACS_2009_5YR_G00_&-_lang=en&-_sse=on.

- 47.Williams DR, Jackson JS. Race/ethnicity and the 2000 census: recommendations for African-American and other black populations in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1728–1730. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller KA, Beauvais F, Burnside M, Jumper-Thurman P. A comparison of American Indian and non-Indian fourth to sixth graders’ rates of drug use. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2008;7(3):258–267. doi: 10.1080/15332640802313239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitbeck LB, Yu M, Johnson KD, Hoyt DR, Walls ML. Diagnostic prevalence rates from early to mid-adolescence among indigenous adolescents: first results from a longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):890–900. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Novins DK, Fickenscher A, Manson SM. American Indian adolescents in substance abuse treatment: diagnostic status. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30(4):275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. [Accessed January 7, 2011.];The American Indian, Eskimo, and Aleut population. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/amerind.html.

- 52.U.S. Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. Federally recognized Indian tribes. [Accessed January 7, 2011.];Federal Register. 2002 Jul 12;67(134) Available at: http://www.artnatam.com/tribes.html. [Google Scholar]

- 53.U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service. [Accessed January 5, 2011.];National NAGPRA: Indian reservations in the continental United States. Available at: http://www.nps.gov/history/nagpra/documents/resmap.htm.

- 54.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Perl HI, Thomas (Tlingit) LR, editors. [Accessed on January 4, 2011.];Methamphetamine and Other Drugs (MOD) in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities (CTN-0033*): Preliminary Report on the Process of MOD Research Partnerships between Community and Institutionally Based Researchers. Available at: http://ctndisseminationlibrary.org/PDF/440.pdf.

- 55.Shapiro GK, Buckley-Hunter L. What every adolescent needs to know: cannabis can cause psychosis. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(6):533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.ProCon.org. [Accessed November 13, 2010.];Should marijuana be a medical option? Available at: http://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/

- 57.Office of National Drug Control Policy. Teens and Prescription Drugs: An Analysis of Recent Trends on the Emerging Drug Threat. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy, Executive Office of the President; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schepis TS, Krishnan-Sarin S. Sources of prescriptions for misuse by adolescents: differences in sex, ethnicity, and severity of misuse in a population-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(8):828–836. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a8130d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(9):618–627. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Veilleux JC, Colvin PJ, Anderson J, York C, Heinz AJ. A review of opioid dependence treatment: pharmacological and psychosocial interventions to treat opioid addiction. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong MM, Klingle RS, Price RK. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among Asian American and Pacific Islander Adolescents in California and Hawaii. Addict Behav. 2004;29(1):127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stillwell R, Hoffman L. Public School Graduates and Dropouts From the Common Core of Data: School Year 2005–2006. National Center for Education Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chromy JR, Feder M, Gfroerer J, Hirsch E, Kennet J, Morton KB, Piper L, Riggsbee BH, Snodgrass JA, Virag TG, Yu F. DHHS Publication No. SMA 09-4425, Methodology Series M-8. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2009. Reliability of Key Measures in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harrison LD, Martin SS, Enev T, Harrington D. DHHS Publication No. SMA 07-4249, Methodology Series M-7. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. Comparing Drug Testing and Self-report of Drug Use among Youths and Young Adults in the General Population. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goodkind JR, Ross-Toledo K, John S, Hall JL, Ross L, Freeland L, Coletta E, Becenti-Fundark T, Poola C, Begay-Roanhorse R, Lee C. Promoting healing and restoring trust: policy recommendations for improving behavioral health care for American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;46(3–4):386–394. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9347-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Winters KC, Kaminer Y. Screening and assessing adolescent substance use disorders in clinical populations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(7):740–744. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817395cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams JF. Adolescent substance abuse and treatment acceptability. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(3):217–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knudsen HK. Adolescent-only substance abuse treatment: availability and adoption of components of quality. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(2):195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mark TL, Song X, Vandivort R, Duffy S, Butler J, Coffey R, Schabert VF. Characterizing substance abuse programs that treat adolescents. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brannigan R, Schackman BR, Falco M, Millman RB. The quality of highly regarded adolescent substance abuse treatment programs: results of an in-depth national survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(9):904–909. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.