Abstract

A novel bifunctional catalyst derived from BINOL has been developed that promotes the highly enantioselective bromolactonizations of a number of structurally distinct unsaturated acids. Like some known catalysts, this catalyst promotes highly enantioselective bromolactonizations of 4- and 5-aryl-4-pentenoic acids, but it also catalyzes the highly enantioselective bromolactonizations of 5-alkyl-4(Z)-pentenoic acids. These reactions represent the first catalytic bromolactonizations of alkyl-substituted olefinic acids that proceed via 5-exo mode cyclizations to give lactones in which new carbon–bromine bonds are formed at a stereogenic center with high enantioselectivity. We also disclose the first catalytic desymmetrization of a prochiral dienoic acid by enantioselective bromolactonization.

Keywords: bromolactonization, amidine, catalysis, bifunctional, enantioselective synthesis

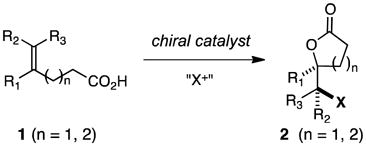

Halolactonization of unsaturated carboxylic acids is an important reaction that has been widely used in organic synthesis, especially for the preparation of molecules of biological relevance.1,2 Accordingly, the development of methods for inducing catalytic, enantioselective halolactonizations in general has become of great interest, and some notable successes have been recorded.3,4 Despite considerable effort, there remain some significant gaps in the area that arise, in part, from the propensity of iodonium and bromonium ions to undergo facile racemization via exchange with olefins prior to cyclization with an internal nucleophile.5 In particular, we are aware of no examples of catalytic, halolactonizations of unsaturated, alkyl-substituted carboxylic acids 1 (n = 1, 2; R1–R3 = H, alkyl) that proceed via 5- or 6-exo modes of ring closure to give lactones 2 in which new carbon-halogen bonds are created at stereogenic centers with high enantioselectivity (eq 1);3h however, enantioselective bromolactonizations of 1 (n = 2, R1 = aryl, and R2 or R3 = alkyl) via 6-exo closures have been recently disclosed.3k The 5-exo cyclizations of unsaturated alcohols to generate stereogenic carbon-halogen bonds by haloetherification are known,6 but the products, which are cyclic ethers, are arguably less versatile as synthetic intermediates than the corresponding lactones. For example, halolactones may be readily converted into halohydrins and epoxides. Finally, we are aware of no examples of catalytic, enantioselective halolactonizations involving prochiral dienes.

|

(1) |

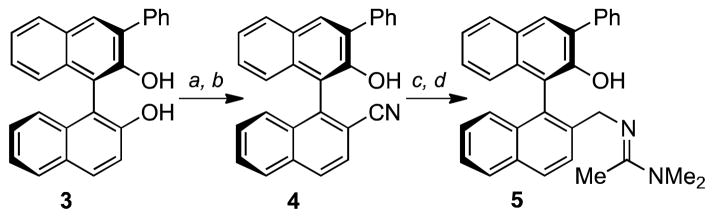

In the context of several ongoing projects in natural product synthesis, we encountered a requirement to induce the enantioselective bromolactonizations of a number of structurally different alkenes. We thus sought to address the existing problems in the field with a novel approach to bifunctional catalyst design.7 Mechanistic considerations suggest that a Lewis base can mediate proton transfer and/or stabilize the intermediate bromonium ion,5c and a Lewis or Brønsted acid can activate the brominating agent.4b These catalytic elements must then be incorporated on a suitable chiral scaffold. There are a number of possibilities, but we decided to use the binaphthyl backbone, which has been widely used as a chiral template for catalyst design.8 Although BINOL-derived catalysts have been used to promote enantioselective iodo–diene cyclizations 9 and haloetherifications,6 binaphthyl-derived ligands do not appear to have been used in halolactonizations. Accordingly, we envisioned that 5, employing a bifunctional partnership of an amidine moiety3e,k and a phenolic –OH group,10 might be an effective catalyst. Bulky groups at the 3- and/or 3′-position of binaphthyl ligands can enhance stereoselectivity, so a 3-phenyl group was incorporated in the first generation catalyst. Catalyst 5 can be readily made on multigram scale in seven steps and 41% overall yield from commercially available material. Monotriflation of 3-phenyl-BINOL (3), which was prepared by the protocol of Shi,11 followed by nickel(0)-catalyzed cyanation provided 4 in 78% yield (2-steps). Reduction of nitrile 4 to the amine and subsequent amidine formation delivered the catalyst 5 in 71% yield (2-steps) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Catalyst Synthesis.

(a) EtN(i-Pr)2, Tf2O, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; 91%. (b) KCN, Ni(PPh3)4, CH3CN, 70 °C; 86%. (c) BH3•THF, 0 °C, Δ; HCl(aq), THF, δ; 92%. (d) CH3C(OMe)2NMe2, CH3CN; 78%.

|

(2) |

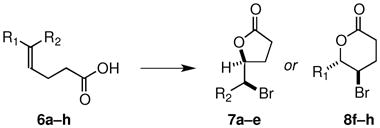

The validity of this new catalyst design was quickly confirmed in preliminary experiments. At the low temperatures required to minimize the background reaction, the commonly used “Br+” sources N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and N,N′-dibromodimethyl hydantoin (DBDMH) gave only trace amounts of product. However, we found that bromolactonizations of a series of 5-alkyl-4(Z)-pentenoic acids 6a–e using 2,4,4,6-tetrabromocyclohexadienone (TBCO) (1.2 equiv) as the brominating agent and 10 mol % of the catalyst 5 proceeded with high regioselectivity to deliver the corresponding γ-lactones 7a–e in excellent yields (eq 2), with enantiomeric ratios (er) between 95:5 – 98:2 for branched alkyl substrates 6b–e and 85:15 for the n-alkyl substrate 6a (Table 1, entries a–e).12 The observation that TBCO is superior to NBS and DBDMH is surprising as in other reports TBCO has been shown to be less efficacious than NBS and DBDMH as a source of electrophilic bromine. 3h,j

Table 1.

Enantioselective Bromolactonizations of 5-Substituted-4-Pentenoic Acids 6 (eq 2)

| Entry | Product | R1 | R2 | % yielda | erb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 7a | H | Et | 90 | 85:15 |

| b | 7b | H | i-Bu | 87 | 95:5 |

| c | 7c | H | i-Pr | 94 | 97:3 |

| d | 7d | H | Cy | 94 | 98.5:1.5 |

| e | 7e | H | t-Bu | 97 | 97:3 |

| f | 8f | Ph | H | 94c | 98:2 |

| g | 8g | 1-Np | H | 97 | 96:4 |

| h | 8h | 2-thienyl | H | 92 | 94:6 |

Isolated yield from the reaction of 1.0 eq of olefinic acid, 1.2 eq TBCO and 0.1 eq catalyst 5 in 1:2 CH2Cl2/tol at −50 °C for 14 h.

er determined by chiral phase HPLC; absolute stereochemistry for 7e was determined by x-ray crystallography and 7a–d are assigned by analogy; 8f–h are assigned based upon correlations of optical rotations with those previously reported.3g

Reaction executed at −60 °C to maximize δ:γ-lactone ratio (20:1).

These reactions represent the first examples of catalytic bromolactonizations of alkyl-substituted olefinic acids that proceed via a 5-exo mode of ring closure to give products in which stereogenic carbon–bromine bonds have been formed with high enantioselectivity. The enantioselectivity for the bromolactonizations of Z-olefins was significantly higher than those for the corresponding E-olefins. For example, E-6c (R1 = i-Pr, R2 = H) underwent cyclization to give the diastereomer of 7c in 98% yield but in 71:29 er. Similar to the findings of Yeung,3g 5-aryl-4(E)-pentenoic acids 6f–h underwent bromolactonization via a 6-endo cyclization mode to give the corresponding δ-lactones 8f–h in uniformly high yield and enantioselectivity (Table 1, entries f–h).

|

(3) |

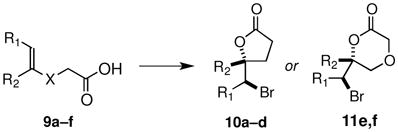

Enantioselective halolactonizations of 4-aryl-4-enoic acid substrates via a 5-exo cyclization mode are well precedented (eq 3), 3b,d–f and we found that 5 also catalyzes the cyclizations of 9a–c in the presence of TBCO to furnish the γ-lactones 10a–c in high yield and er (Table 2, entries a–c). The electronic nature of aryl substituents plays an important role in these reactions; greater electron withdrawing power enhances the enantioselectivity.13 When the 5-substituted-5-eneoic acids 9e,f are used as substrates, the bromolactonization proceeds via a 6-exo mode to give δ-lactones 11e,f (Table 2, entries e,f).3d,e To our knowledge the exo cyclizations of 9d,f are the first examples of a catalytic, enantioselective halolactonization of a trialkyl-substituted olefinic acids to give lactones in which a stereogenic carbon- bromine bond is formed (Table 2, entries d,f), although a related bromolactonization of an aryl-substituted unsaturated acid was recently reported.3k It is noteworthy that the enantioselectivity for the 6-exo cyclization of 9f is somewhat higher than that for the 5-exo cyclization of 9d.

Table 2.

Exo Mode Enantioselective Reactions of 9a–f (eq 3)

| Entry | Product | X | R1 | R2 | % yielda | erb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 10a | –CH2– | H | Ph | 99 | 86:14 |

| b | 10b | –CH2– | H | m-CN-Ph | 89 | 91:9 |

| c | 10c | –CH2– | H | p-CN-Ph | 92 | 94:6 |

| d | 10d | –CH2– | Me | Me | 89 | 71:29 |

| e | 11e | -CH2O- | H | Ph | 98 | 86:14 |

| f | 11f | -CH2O- | Me | Me | 93 | 85:15 |

Isolated yield from the reaction of 1.0 eq of olefinic acid, 1.2 eq TBCO and 0.1 eq catalyst 5 in 1:2 CH2Cl2/tol at −50 °C for 14 h.

er determined by chiral phase HPLC; the absolute stereochemistry of 11a is based on comparison of its optical rotation with that previously reported,3f and other assignments are based upon analogy.

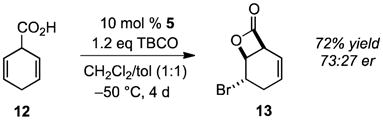

A major challenge to any catalytic, enantioselective transformation is its application to the desymmetrization of prochiral substrates. It is thus significant that 5 catalyzes the bromolactonization of prochiral dienoic acids as exemplified by the conversion of 12 into 13, the absolute stereochemistry of which was established by x-ray analysis, with high regioselectivity and 73:27 er (eq 4). It is noteworthy that similar bromolactonizations to give racemic products have been used as key steps in the syntheses of several naturally occurring compounds.14

|

(4) |

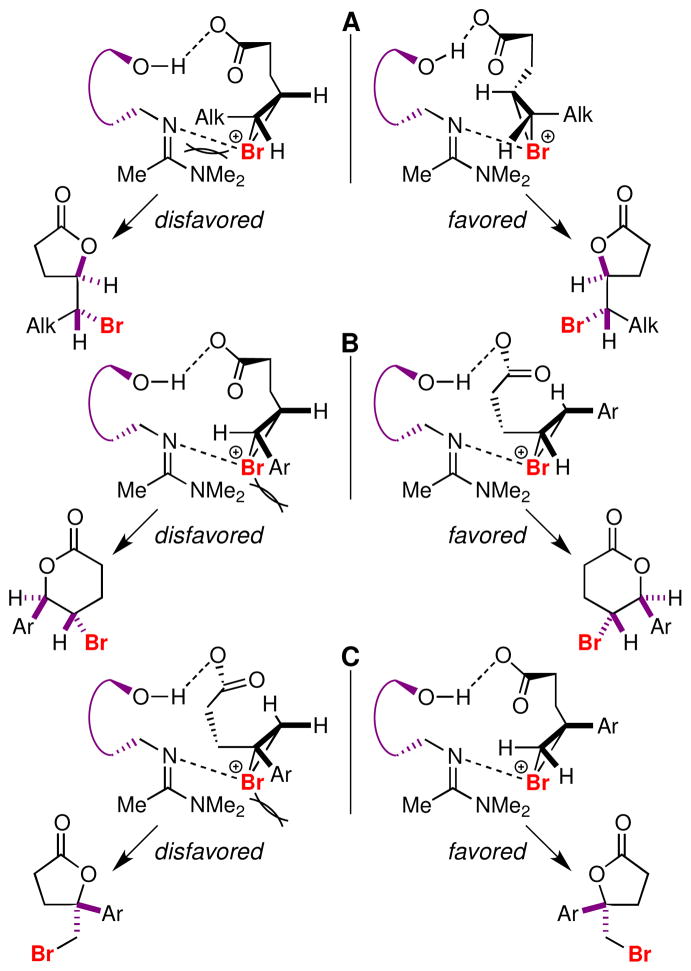

The basic mechanistic features of bromonium ion-initiated cyclizations are reasonably well established.4b,5c Catalyst 5 is unusual in that it contains relatively acidic phenolic- and highly basic amidine-functions, so determining the identities of the Brønsted acid and the Lewis base is somewhat problematic. With this caveat in mind, one tentative working model that is consistent with the stereochemical outcome of bromolactonizations catalyzed by 5 is shown in Figure 1. We assume that hydrogen bonding between the phenolic –OH and the carboxyl group orients the substrate relative to the catalyst and that the substituent on the olefin is directed away from the face of the binaphthyl scaffold in a way that minimizes torsional strain within the substrate and steric interactions with the catalyst. The bromonium ion is presumably then stabilized by interaction with the amidine moiety. Our preliminary analysis suggests that the amidine may be an important stereochemical control element in these reactions, although the 3-phenyl group does appear to help by compressing the substrate toward the amidine moiety. In support of this hypothesis, we performed a test experiment and found that the norphenyl analog of 5 catalyzed the bromolactonization of 9a to give 10a with somewhat lower (81:19 er) enantioselectivity than 5 (Table 2, entry a).

Figure 1.

Tentative stereochemical model for enantioselective bromolactonizations catalyzed by 5. (A) Preferred mode for cyclizations of 6a–e. (B) Preferred mode for cyclizations of 6f–h. (C) Preferred mode for cyclizations of 9a–c; model for 6-exo cyclizations of 9e,f is similar.

In summary, we have developed 5 as a novel bifunctional catalyst to promote highly efficient and enantioselective bromolactonizations of an unusually broad array of structurally distinct, unsaturated acids. Like other known catalysts, 5 promotes highly enantioselective bromolactonizations of 4- and 5-aryl-4-pentenoic acids, but unlike those catalysts, it induces the bromolactonizations of alkyl-4(Z)-pentenoic acids via 5-exo cyclizations to give lactones in which new carbon–bromine bonds have been formed at stereogenic centers with high enantiomeric ratios. Bromolactonizations of trisubstituted olefinic acids that proceed via 5- and 6-exo cyclizations occur with good enantioselectivity. We also disclose the first example of the desymmetrization of a prochiral dienoic acid by a catalytic, enantioselective bromolactonization. Although the enantiomeric ratios observed for the bromolactonizations of more demanding substrates is modest, the chiral framework of 5 offers numerous opportunities for structural modification to improve enantioselectivities and to extend the utility of this class of catalysts to other electrophile-initiated cyclizations, including iodo- and chloro-lactonizations. These developments as well as the use of catalysts related to 5 in key steps in complex molecule synthesis will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM31077) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0652) for generous support of this research. DHP thanks the NIH for a postdoctoral fellowship (GM096557). We are also grateful to Dr. Vincent Lynch (The University of Texas) for x-ray crystallography and Shawn Blumberg (The University of Texas) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Synthesis of catalyst 5, experimental procedures, characterization of new compounds, and x-ray crystal data; this material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Ranganathan S, Muraleedharan KM, Vaish NK, Jayaraman N. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:5273–5308. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lava MS, Banerjee AK, Cabrera EV. Curr Org Chem. 2009;13:720–730. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rodriguez F, Fananas FJ. In: Handbook of Cyclization Reactions. Ma S, editor. Vol. 4. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2010. pp. 951–990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gribble GW. Chem Soc Rev. 1999;28:335–346. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For recent examples of enantioselective halolactonizations, see: Ning Z, Jin R, Ding J, Gao L. Synlett. 2009:2291–2294.Whitehead DC, Yousefi R, Jaganathan A, Borhan B. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3298–3300. doi: 10.1021/ja100502f.Zhang W, Zheng S, Liu N, Werness JB, Guzei IA, Tang W. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3664–3665. doi: 10.1021/ja100173w.Veitch GE, Jacobsen EN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:7332–7335. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003681.Murai K, Matsushita T, Nakamura A, Fukushima S, Shimura M, Fujioka H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:9174–9177. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005409.Zhou L, Tan CK, Jiang X, Chen F, Yeung Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15474–15476. doi: 10.1021/ja1048972.Tan CK, Zhou L, Yeung Y. Org Lett. 2011;13:2738–2741. doi: 10.1021/ol200840e.Tan CT, Le C, Yeung Y. Chem Commun. 2012;48:5793–5795. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31148h.Dobish MC, Johnston JN. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6068–6071. doi: 10.1021/ja301858r.Zhang W, Liu N, Schienebeck CM, Decloux K, Zheng S, Werness JB, Tang W. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:7296–7305. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103809.Murai K, Nakamura A, Matsushita T, Shimura M, Fujioka H. Chem Eur J. 2012 doi: 10.1002/chem.201200647.Jiang X, Tan CK, Zhou L, Yueng Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012 doi: 10.1002/anie.201202079.

- 4.For reviews of enantioselective halocyclizations, see: Chen G, Ma S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8306–8308. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003114.Tan CK, Zhou L, Yeung Y. Synlett. 2011:1335–1339.Snyder SA, Treitler DS, Brucks AP. Aldrichimica Acta. 2011;44:27– 40.

- 5.(a) Brown RS. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:131–137. [Google Scholar]; (b) Denmark SE, Burk MT, Hoover AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1232–1233. doi: 10.1021/ja909965h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Denmark SE, Burk MT. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2010;107:20655–20660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005296107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Huang D, Wang H, Xue F, Guan H, Li L, Peng X, Shi Y. Org Lett. 2011;13:6350–6353. doi: 10.1021/ol202527g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Denmark SE, Burk MT. Org Lett. 2012;14:256–259. doi: 10.1021/ol203033k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hennecke U, Muller CH, Frohlich R. Org Lett. 2011;13:860–863. doi: 10.1021/ol1028805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For reviews, see: Kanai M, Kato N, Ichikawa E, Shibasaki M. Synlett. 2005:1491–1508.Paull DH, Abraham CJ, Scerba MT, Alden-Danforth E, Lectka T. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:655–663. doi: 10.1021/ar700261a.Akiyama T, Itoh J, Fuchibe K. Adv Synth Catal. 2006;348:999–1010.

- 8.(a) Ohkuma T, Kitamura M, Noyori R. In: Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. 2. Ojima I, editor. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2000. pp. 1–110. [Google Scholar]; (b) Berkessel A, Gröger H, editors. Asymmetric Organocatalysis. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakakura A, Ukai A, Ishihara K. Nature. 2007;445:900–903. doi: 10.1038/nature05553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Schenker S, Zamfir A, Freund M, Tsogoeva S. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:2209–2222. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chauhan P, Chimni SS. RCS Adv. 2012;2:737–758. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi M, Chen LH, Li CQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3790–3800. doi: 10.1021/ja0447255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The 6-bromo derivative of 5, recovered from the reaction in 95% yield, gave results identical to those observed for 5 in several test reactions. The structure was confirmed by x-ray crystallography.

- 13.A preliminary experiment using 9 (R1 = H, R2 = p-MeOPh) suggests that electron-donating groups degrade enantioselectivity.

- 14.For examples, see: Ganem B, Holbert GW, Weiss LB, Ishizumi K. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:6483–6491.Inai M, Goto T, Furuta T, Wakimoto T, Kan T. Tetrahedron: Asymm. 2008;19:2771–2773.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.