Abstract

Two types of stem cells are currently defined in small intestinal crypts: cycling crypt base columnar (CBC) cells and quiescent ‘+4’ cells. Here, we combine transcriptomics with proteomics to define a definitive molecular signature for Lgr5+ CBC cells. Transcriptional profiling of FACS-sorted Lgr5+ stem cells and their daughters using two microarray platforms revealed an mRNA stem cell signature of 384 unique genes. Quantitative mass spectrometry on the same cell populations identified 278 proteins enriched in intestinal stem cells. The mRNA and protein data sets showed a high level of correlation and a combined signature of 510 stem cell-enriched genes was defined. Spatial expression patterns were further characterized by mRNA in-situ hybridization, revealing that approximately half of the genes were expressed in a gradient with highest levels at the crypt bottom, while the other half was expressed uniquely in Lgr5+stem cells. Lineage tracing using a newly established knock-in mouse for one of the signature genes, Smoc2, confirmed its stem cell specificity. Using this resource, we find—and confirm by independent approaches—that the proposed quiescent/‘+4’ stem cell markers Bmi1, Tert, Hopx and Lrig1 are robustly expressed in CBC cells.

Keywords: Lgr5, proteomics, signature, stem cells, transcriptomics

Introduction

The epithelium of the small intestine represents a prototypic example of a mammalian stem cell-driven self-renewing tissue. The epithelium consists of luminal protrusions called villi, and pit-like recessions called crypts. A small number of stem cells reside at crypt bottoms. Daughter cells exit the stem cell compartment into the transit amplifying (TA) compartment. TA cells go through 4–5 divisions of unusually short duration, that is, 12 h (Marshman et al, 2002). During this process, the TA cells move towards the crypt-villus junction and differentiate into enterocytes, goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells. These differentiated cells continue to move upwards towards the tip of the villus. Upon reaching the villus tip after 2–3 more days, the differentiated cells undergo apoptosis and are shed into the gut lumen. A fourth cell type, the Paneth cell, also derives from the stem cells, but migrates towards the crypt bottom where it resides for 6–8 weeks (Bjerknes and Cheng, 2006).

Recently, we have described that small cycling cells located between the Paneth cells, previously termed as crypt base columnar (CBC) cells (Cheng and Leblond, 1974), specifically express the Lgr5 gene (Barker et al, 2007). By lineage tracing, we demonstrated that these Lgr5+ cells generate all cell lineages of the small intestinal epithelium over the lifetime of the animal. Similar data were published utilizing a Prom1/Cd133-based lineage tracing strategy (Zhu et al, 2009). Deletion of adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc), the first hit in colorectal cancer initiation, leads to adenoma formation specifically in Lgr5+ stem cells and thus these cells can be regarded as the cell-of-origin for intestinal cancer (Barker et al, 2009). As further proof of their stem cell identity, we demonstrated that single Lgr5+ cells can be cultured into ever-growing epithelial organoids, which possess all characteristics of the epithelial tissue in the living animal (Sato et al, 2009). In the colon, hair follicle and stomach, Lgr5 also marks stem cells (Barker et al, 2007, 2010; Jaks et al, 2008). Clonal Lgr5-derived colon organoids can be grafted into recipient mice to yield functionally normal epithelium that persists for >6 months (Yui et al, 2012). The related Lgr6 gene is expressed by a population of multipotent skin stem cells (Snippert et al, 2010b).

Potten et al (1974) have previously postulated that a cycling, yet DNA label-retaining cell residing at position +4 relative to the crypt bottom represents a stem cell population. Sangiorgi and Capecchi (2008) have employed lineage tracing based on Bmi1 expression, which reportedly occurred specifically in +4 cells. Long-term lineage tracing was observed with kinetics that were similar to the kinetics obtained in the Lgr5-based tracing experiments. Contrasting with the previous report, we observed that Lgr5+ cells express the highest levels of Bmi1 as determined by cell sorting and qPCR analysis (van der Flier et al, 2009a). Furthermore, single molecule mRNA in-situ hybridization revealed that the Bmi1 transcripts are expressed throughout the entire crypt (Itzkovitz et al, 2011). This broad expression pattern of Bmi1 was also observed in a recent publication analysing in detail the starting position of lineage tracing from the Bmi1 locus (Tian et al, 2011). Three other markers are proposed more recently for the quiescent ‘+4’ cell: Hopx (Takeda et al, 2011), Tert (Montgomery et al, 2011) and Lrig1 (Powell et al, 2012). In an independent study, Lrig1 was found to be expressed highest in CBC cells (Wong et al, 2012). Together, these studies suggest that Lgr5+ cells appear to be the ‘workhorse stem cells’ fuelling the daily self-renewal of the small intestine, while a pool of quiescent ‘reserve’ Lgr5 negative (Lgr5−) stem cells may exist above the crypt base (Li and Clevers, 2010). However, based on the discrepant studies on marker gene expression, it appears of paramount importance to obtain detailed molecular signatures for the two stem cell types before definitive conclusions can be drawn. The availability of a knock-in mouse expressing GFP from the Lgr5 locus allows the isolation of CBC stem cells from the intestine (Barker et al, 2007), providing a unique entry to understand ‘stemness’ (Vogel, 2003) and the in vivo differentiation process of this tissue (Simons and Clevers, 2011). Therefore, we have characterized transcriptomic and proteomic differences between Lgr5+ stem cells and their daughter cells enabling us to define a definitive Lgr5 intestinal stem cell (ISC) signature.

Results

Transcriptomic profile of Lgr5+ stem cells

Transcriptional differences between ISCs and their daughter cells can be explored by use of the Lgr5-EGFP-ires-CreERT2 knock-in (Lgr5-ki) mouse (Supplementary Figure S1A; Barker et al, 2007). In this mouse model, GFP expression is driven from the Lgr5 locus, leading to highest GFP levels in Lgr5+ cells (GFPhigh). Yet, due to the stability of the GFP protein, it is distributed upon cell division to the daughter cells, which form a clearly distinguishable daughter cell population (GFPlow). Previously, we performed a gene expression analysis of intestinal Lgr5+ stem cells, which led to the identification of the transcription factor Ascl2 as a regulator of ISC fate (van der Flier et al, 2009a). Since then, we have systematically optimized the workflow for Lgr5+ cell sorting, resulting in a better separation of different GFP cell fractions and shorter isolation time, minimizing sample manipulation and, ultimately, leading to better RNA quality for transcriptional profiling. Here, two independent microarray platforms (Affymetrix and Agilent) were used to compare ISCs and their daughters (Supplementary Figure S1B). These two expression array platforms were chosen for their distinct configurations (two colours versus one colour) and their ability to complement each other (Patterson et al, 2006). A comparison to our previously published Agilent data set revealed that the average intensity of established stem cell genes (e.g., Lgr5, Ascl2, Olfm4 and Tnfrsf19) in the GFPhigh fraction increased by seven-fold upon using the improved FACS sorting procedure, resulting in a five-fold increase (56 versus 274) in the number of identifiable stem cell-enriched genes.

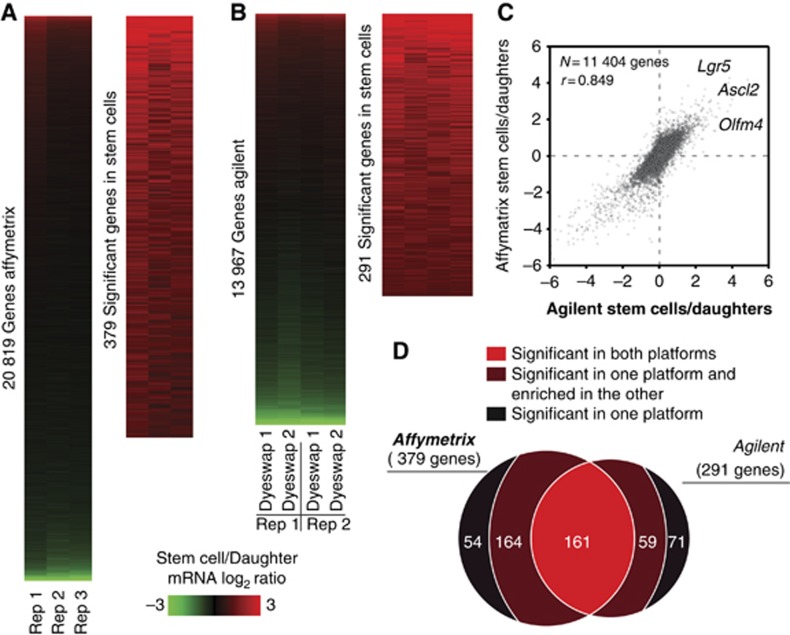

For the Affymetrix platform, ratios for all 20 819 unique genes represented on the arrays were calculated (Figure 1A). Using a combination of statistical significance and fold change (see Materials and methods), a set of 379 stem cell-enriched genes was defined (Figure 1A; Supplementary Table S1). For Agilent arrays, 13 967 unique genes were consistently expressed above background (Figure 1B) from which 291 genes were found to be expressed significantly higher in the stem cells (Figure 1B; Supplementary Table S2). Comparing the two platforms, we found an overall good correlation of r=0.85 (Figure 1C). Nevertheless, a strikingly low overlap (161 genes) was observed when the stem cell signatures of the two platforms were compared (Figure 1D). The subsequent inspection of the non-overlapping genes revealed that a substantial fraction (59 and 164 genes, respectively) was enriched >1.5-fold, although not significantly, in the other platform (Figure 1D). Combining the genes that were significant in both platforms with the genes significant in one and enriched >1.5-fold in the other platform, we could define a high-confidence list of 384 stem cell-enriched transcripts (referred to as the ‘mRNA stem cell signature’; Supplementary Table S3). From the genes that remained to be defined by only one of the two microarray platforms, 72% (51/71) and 57% (31/54) showed a low enrichment (log2 of >0.2 and <0.58) on the other platform (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). Thus, although the two platforms show a high level of concordance, the necessity to define thresholds for the definition of significantly changed genes is the reason for missing a substantial number of stem cell-enriched genes. Our results demonstrate that Agilent and Affymetrix platforms complement each other and may be used in parallel if a high level of comprehensiveness is desired.

Figure 1.

The mRNA stem cell signature. (A) Expression levels for 20 819 unique genes were detected with Affymetrix, from which 379 were found to be statistically significant and >2-fold enriched in the stem cells. (B) Likewise, 291 out of 13 697 genes were found significantly enriched in stem cells with Agilent. (C) Correlation plot of both transcriptomic data sets. Well-known intestinal stem cell markers are annotated. (D) Overlap between the significant genes found by each platform.

Proteomic profile of Lgr5+ stem cells

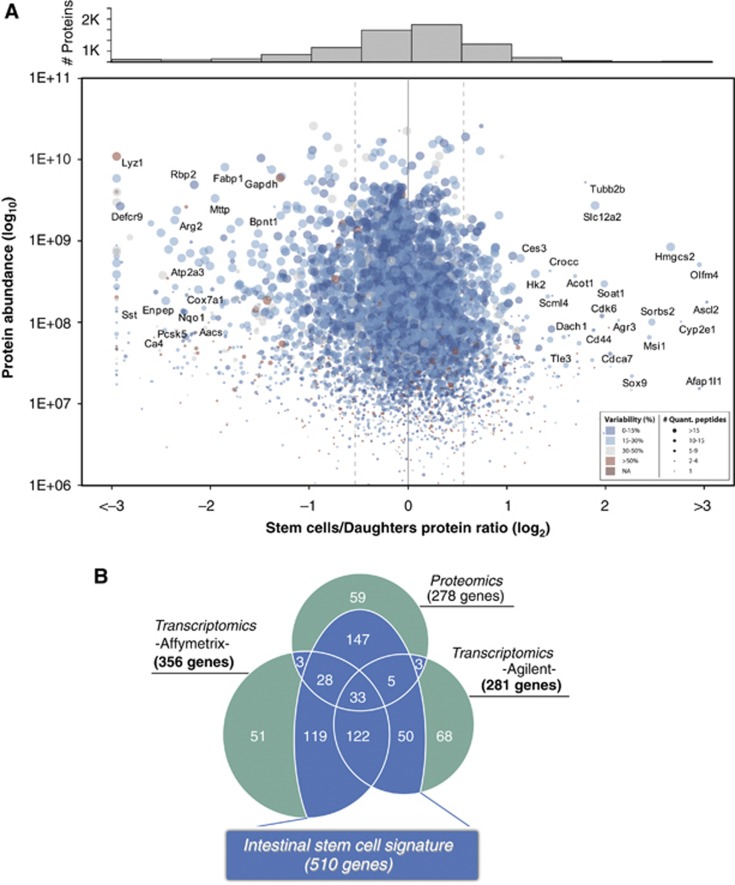

mRNA levels do not always reflect the abundance of the translated protein (Schwanhausser et al, 2011). Therefore, examination of the actual protein content might give further insight into the molecular stem cell signature. We applied a mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics approach to study the protein content of Lgr5+ cells and their daughter cells (Supplementary Figure S1C), confidently identifying 7967 unique protein groups (Supplementary Figure S2; Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). Among them, we obtained an excellent representation of proteins that are known to be expressed at a low-copy number in mammalian cells including 648 transcription factors, 276 protein kinases and 248 signalling molecules. Of note, Lgr5 itself was not identified. The identification of plasma membrane proteins by MS is challenging due to insolubility in standard proteomic sample preparations. Nevertheless, our data set contains 1278 proteins with predicted trans-membrane domains (Krogh et al, 2001), and Gene Ontology analyses detected no underrepresentation of this protein class (plasma membrane; P>0.05). However, Lgr5 encodes a 7-transmembrane (7-TM) receptor expressed at low levels (van der Flier et al, 2009b). Both the high hydrophobicity and low expression probably contributed to its absence in our MS survey. Indeed, Gene Ontology analyses showed a clear underrepresentation of 7-TM proteins in our data set (G-protein coupled receptors; P=8.4E–54). For 92% of the identified proteins, mRNA expression was confirmed in the transcriptomic profiling, demonstrating the confidence of our proteomic data set. Most importantly, 4817 unique proteins were quantified in common in two biological replicates (6075 in total) (Figure 2A; Supplementary Figures S3 and S4; Supplementary Table S8). In all, 278 were found to be enriched >1.5-fold (consistently in both replicates) in stem cells (referred to as the ‘protein stem cell signature’; Supplementary Table S9). Our proteomic data confirmed several proteins previously described to be specific for the Lgr5+ stem cells, such as Ascl2 (van der Flier et al, 2009a), Olfm4 (van der Flier et al, 2009b), Sox9 (Bastide et al, 2007) and Msi1 (Kayahara et al, 2003; Potten et al, 2003) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Proteomic analysis of Lgr5+ cells and the intestinal stem cell signature. (A) The protein stem cell signature. In all, 4817 proteins were quantified in two independent experiments (Supplementary Table S7). The average ratios (log2) are plotted against protein abundance (log10). The number of peptides used for the quantification as well as the variability (calculated as the relative standard deviation of the peptide ratios) is represented in the plot by the spot size and colour scale, respectively. The histogram of frequencies shows the protein densities per bin (size of 0.5). Using a cutoff of >1.5-fold (±0.58 in log2) in both biological replicas, 278 proteins were found to be more abundant in the stem cells. (B) The intestinal stem cell signature. For each method, a list of significantly changed genes (mRNAs or proteins) was established. Genes significant in one method, but not detected or not found enriched in any other method are highlighted in green. Genes that were found significant in one method and could be confirmed by one or both other methods are highlighted in blue and together constitute the intestinal stem cell signature.

Complementary transcriptomic and proteomic profiling define the ISC signature

Having established both the mRNA and protein signatures of ISCs, we next asked if post-transcriptional regulation might play an important role in regulating specific protein levels. The overall correlation between the mRNA and protein data was high (r=0.78 for Agilent and r=0.80 for Affymetrix; Supplementary Figure S5). This result, besides authenticating both the mRNA and the proteomic measurements, suggests that the ISC phenotype as well as the early differentiation process is strongly regulated at the transcriptional level. Of the 278 proteins in the ‘protein stem cell signature’, 72 were found in the ‘mRNA stem cell signature’ (Figure 2B). Additionally, 147 proteins were >1.5-fold enriched in either both or one array platform and were added to the combined signature (Figure 2B). Nevertheless, some genes were found enriched at the mRNA level, but not at the protein level and vice versa. For 27 genes of the ‘mRNA stem cell signature’, no enrichment was found in the Lgr5+ stem cells although the protein product was detected by MS (Supplementary Table S10). As proteins are the main mediators of biological functions, these genes are unlikely to play a specific biological role in stem cells and were therefore subtracted from the signature. Conversely, no array platform could detect a significant enrichment on the mRNA level for 59 proteins within the ‘protein stem cell signature’ (Figure 2B). Nevertheless, 78% (46/59) of these proteins were enriched (yet below the significance level) in at least one of the array platforms (Supplementary Table S11). For only five proteins, no enrichment on mRNA level was found. Therefore, post-transcriptional regulation did not appear to represent a major mechanism regulating protein levels of ISC-related genes. Nevertheless, the MS data allowed us to define a set of 147 proteins, which could be added to the signature due to their consistent enrichment in Lgr5+ cells on both protein and mRNA levels. As a result of the combined proteomic and transcriptomic profiling, we were able to define a set of 510 genes with stem cell-enriched expression, which we termed the ‘intestinal stem cell signature’ (Figure 2B; Supplementary Table S12).

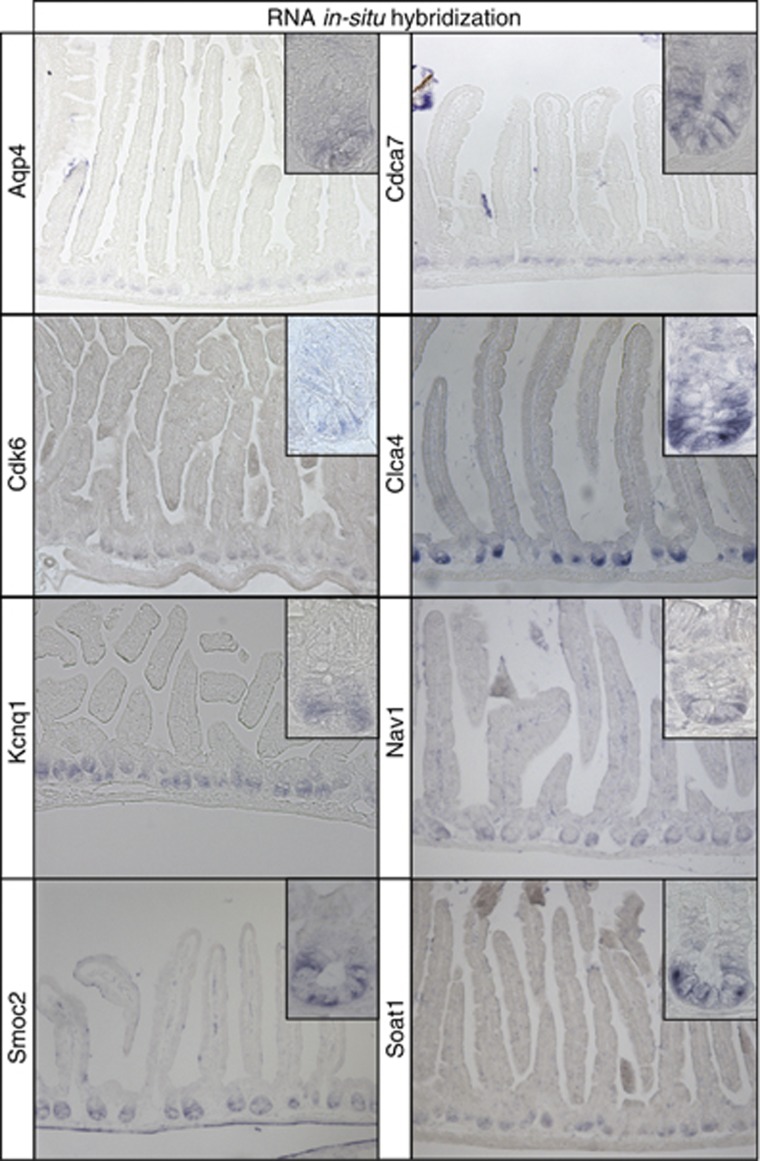

Expression pattern of novel Lgr5 stem cell-enriched genes within the intestinal crypt

Subsequently, we investigated the spatial expression pattern of genes enriched in the intestinal stem cell. Enriched genes may exhibit different expression patterns, that is, they may be entirely CBC restricted or display a more extensive gradient within the crypt (Supplementary Figure S1D). We attempted to perform RNA in-situ hybridization for the 33 genes found in all three data sets (Figure 2B). Of these, no or non-specific staining was obtained for 11 genes, most likely reflecting low-level expression of the pertinent gene. The expression pattern of five genes was already known (Ascl2, Cd44, Msi1, Olfm4 and Sox9). From the remaining 17 genes, 9 showed a gradient within the crypt with highest expression at the crypt bottom (Afap1l1, Agr3, Cnn3, Dach1, Slc12a2, Slco3a1, Sorbs2, Tns3 and Vdr; Supplementary Figure S6). Finally, for eight genes an expression pattern restricted to the very bottom of the crypt in the stem cell zone was observed (Aqp4, Cdca7, Cdk6, Clca4, Kcnq1, Nav1, Smoc2 and Soat1; Figure 3). Thus, these results confirmed the findings derived from the transcriptomic and proteomic screenings and provided additional information on the specificity for Lgr5 stem cells.

Figure 3.

RNA in-situ hybridization screen. An mRNA in-situ hybridization screen was performed for the 33 signature genes in the central overlap (Figure 2B) to explore their spatial expression pattern. A specific expression signal at the very bottom of intestinal crypts in the stem cell zone was detected for eight genes.

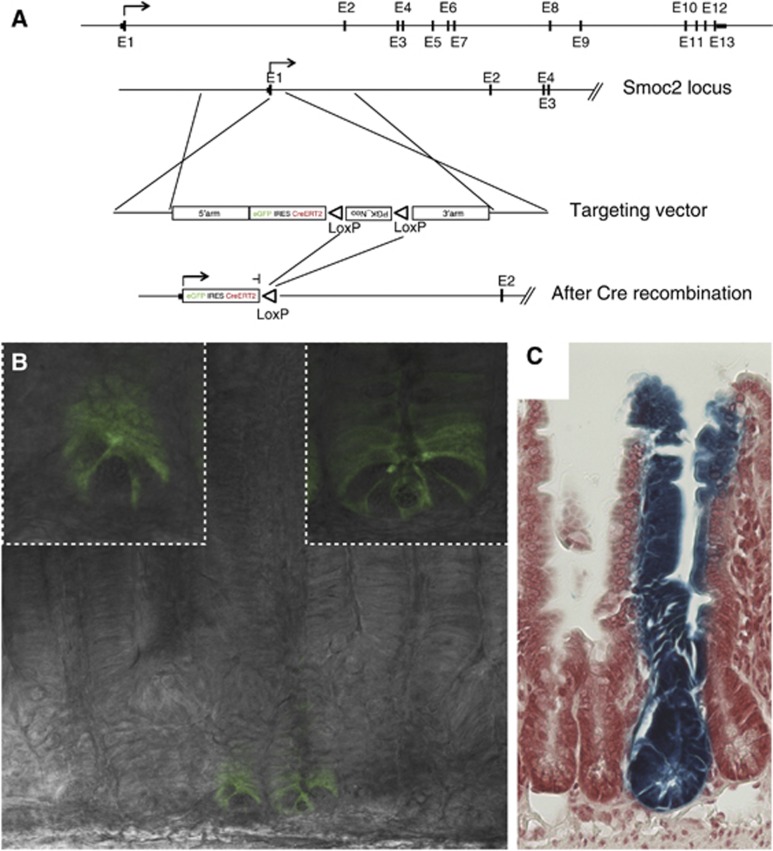

Smoc2 is expressed specifically in ISCs in vivo

To validate the list, we studied one of the novel CBC marker genes, Smoc2, in more detail. The Xenopus laevis orthologue of Smoc1/2 has been described as a BMP signalling inhibitor (Thomas et al, 2009). BMP signalling is active in the intestinal villus compartment where it inhibits de-novo crypt formation (Haramis et al, 2004), and its inhibition by Noggin is essential to maintain intestinal organoid cultures (Sato et al, 2009). As Noggin is not expressed in the intestinal epithelium, Smoc2 expression by ISCs might be a physiological way to block BMP signalling in the stem cell niche. To confirm the stem cell-specific expression of Smoc2, we generated a Smoc2-EGFP-ires-CreERT2 knock-in (Smoc2-ki) mouse model in analogy to the Lgr5-ki (Figure 4A). Homozygous Smoc2-ki mice, constituting functional Smoc2 null mice, did not show any intestinal nor gross non-intestinal phenotype. As expected, GFP expression was detected in CBC cells (Figure 4B). Similarly to the Lgr5-ki, variegated expression of the transgene was detected throughout the small intestine. Lineage tracing performed in Smoc2-ki mice crossed with the R26R-LacZ Cre reporter strain resulted in typical stem cell tracings events: long-lived ‘ribbons’ spanning the entire crypt-villus axis (Figure 4C). This new stem cell-specific mouse model validated the usefulness of the Lgr5 signature for defining stem cell-related genes in vivo.

Figure 4.

Smoc2 marks intestinal stem cells in vivo. (A) An EGFP-ires-CreERT2 cassette was inserted at the translational start site of Smoc2 by homologous recombination, followed by excision of the Neo cassette by Cre mediated recombination. (B) Endogenous GFP expression was readily detectable in crypt base columnar cells, the Lgr5+ stem cells of the small intestine. Of note, the expression of GFP was patchy as in the Lgr5-ki mouse, indicating a silencing in the majority of crypts. (C) Lineage tracing in Smoc2-EGFP-ires-CreERT2/R26RLacZ mice showed long-term labelling (>6 month) of intestinal stem cells and revealed typical intestinal stem cell tracing events.

Expression pattern of proposed quiescent ‘+4’ marker genes in the intestinal crypt

We then interrogated the Lgr5 stem cell signature for the expression behaviour of the quiescent/‘+4’ stem cell markers mentioned above, that is, Bmi1, Tert, Hopx and Lrig1. Of note, all these markers were validated in the initial studies by genetic lineage tracing (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008; Montgomery et al, 2011; Takeda et al, 2011; Powell et al, 2012). Both array platforms detected a slight enrichment of Bmi1 (1.4-fold in Affymetrix and 1.6-fold in Agilent), Tert (1.4-fold and 1.3-fold) as well as of Hopx (1.6-fold and 1.7-fold) in Lgr5+ stem cells. Lrig1 showed a >2-fold enrichment in Lgr5+ stem cells (3.2-fold 2.3-fold). Proteomics did not detect protein expression of Bmi1 and Tert, probably due to their low expression levels. The highly expressed Hopx and Lrig1 were detected by proteomics in Lgr5+ stem cells as well as their daughter cells, with Hopx showing a slight (1.3-fold) and Lrig1 a clear enrichment (2.5-fold) in Lgr5+ stem cells.

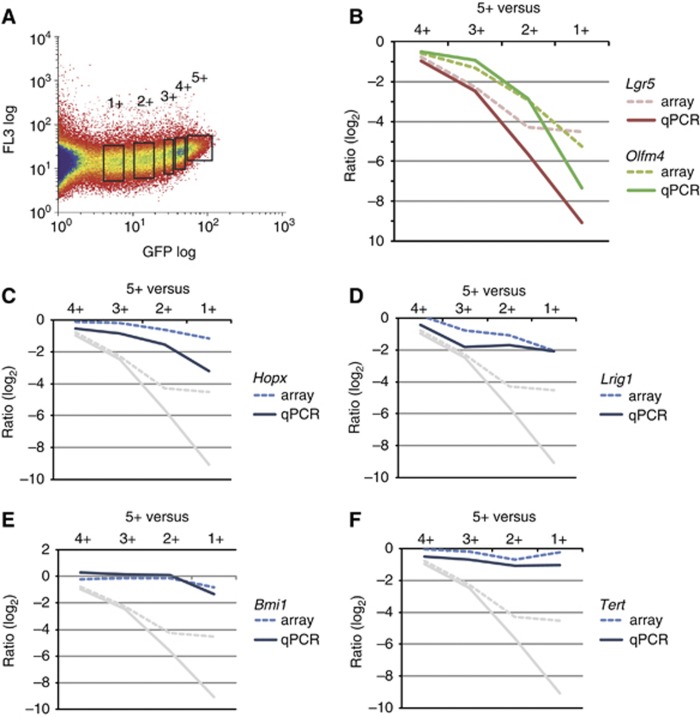

We then documented the expression of these four genes in an independent sorting experiment in which we arbitrarily subdivided all Lgr5-GFP positive cells into five fractions (Figure 5A). The four lower fractions were individually hybridized against the highest (5+) GFP fraction on Agilent arrays, allowing us to draw detailed gradient plots along the crypt axis. In addition, we performed qPCR for the four genes on cDNA obtained in an independent sorting experiment. As expected, the CBC stem cell markers Lgr5 and Olfm4 were strongly enriched in Lgr5+ stem cells (Figure 5B). Of the four proposed quiescent/‘+4’ markers, Hopx and Lrig1 were most highly expressed in the 5+ fraction (Figure 5C and D). Bmi1 showed no difference between the highest four fractions and only then dropped in expression (Figure 5E), while Tert was expressed at rather similar levels throughout the fractions (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Expression profiling along the intestinal crypt axis. (A) GFP-positive cells derived from the small intestine of Lgr5-EGFP-ires-CreERT2 knock-in mice were sorted arbitrarily in five different fractions, ranging from lowest (1+) to highest (5+) GFP expression. (B–F) A gradient plot of the expression along the crypt was generated by plotting the log2 ratio of the 5+ fraction versus the four lower fractions. (B) Gradient plots of the known CBC stem cell markers Lgr5 and Olfm4. (C–F) Gradient plots of the proposed quiescent/+4 marker genes Hopx, Lrig1, Bmi1 and Tert. Dotted lines are based on ratios from the arrays and continuous lines are based on ratios calculated from qPCR analyses. The ratios of Lgr5 are plotted in grey for comparison in (C–F).

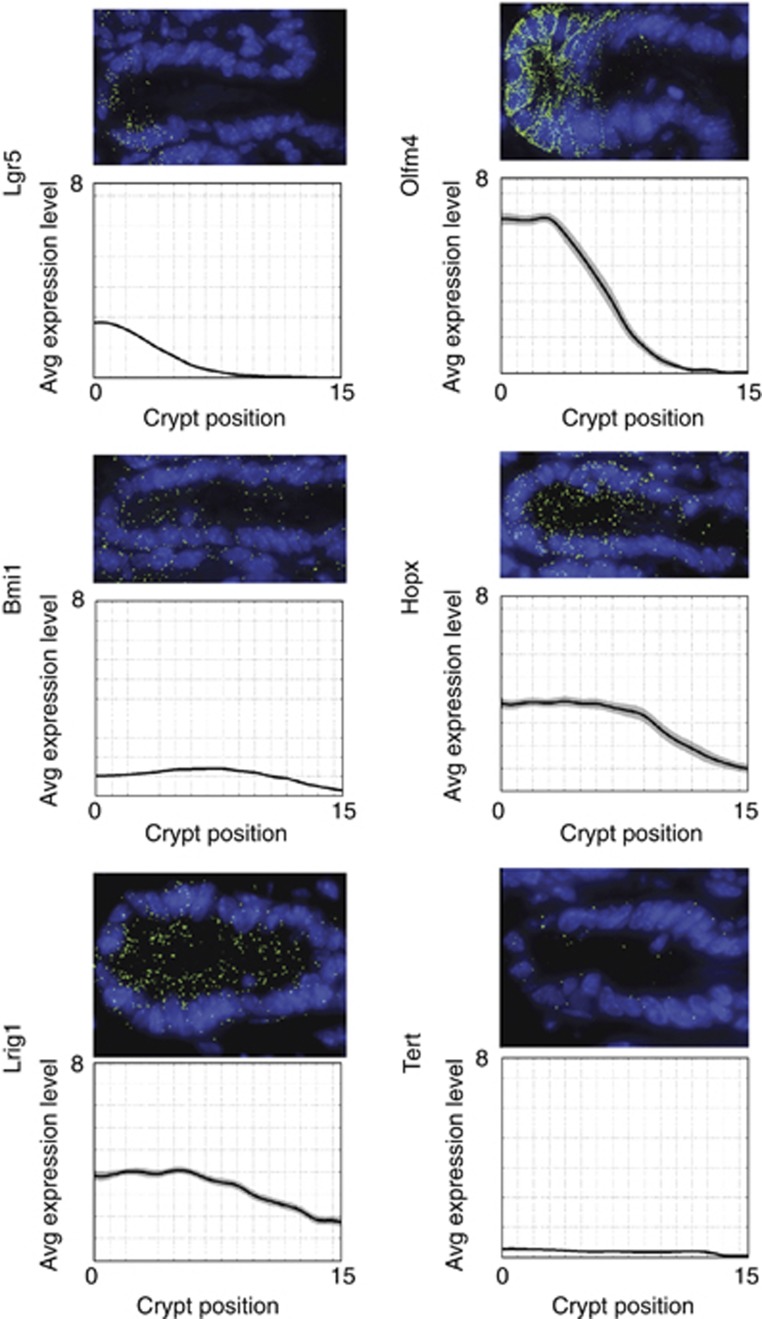

To further validate these expression data on unmanipulated crypts, we performed single molecule mRNA hybridizations for all marker genes, as published before (Itzkovitz et al, 2011; Figure 6). Lgr5 was most exclusively expressed in cells intermingled with Paneth cells. Olfm4, Lrig1 and Hopx were enrichedat the bottom of crypts, but the expression gradient extended to varying degrees above the Paneth cell compartment. Tert and Bmi1 appeared expressed at similar low levels throughout the crypt with the inclusion of the Paneth cell zone. We did not detect specific enrichment of mRNA molecules of any marker at the ‘+4’ position, nor did we detect heterogeneity between crypts, making an enrichment at this position in only a low fraction of crypts unlikely.

Figure 6.

Single molecule transcript counting of intestinal stem cell markers. The top images are representative crypts, the bottom figures show average expression profiles (patches are standard error of the means). At least 30 crypts were analysed. Numbers on the y axis denote the average number of transcripts per crypt cell.

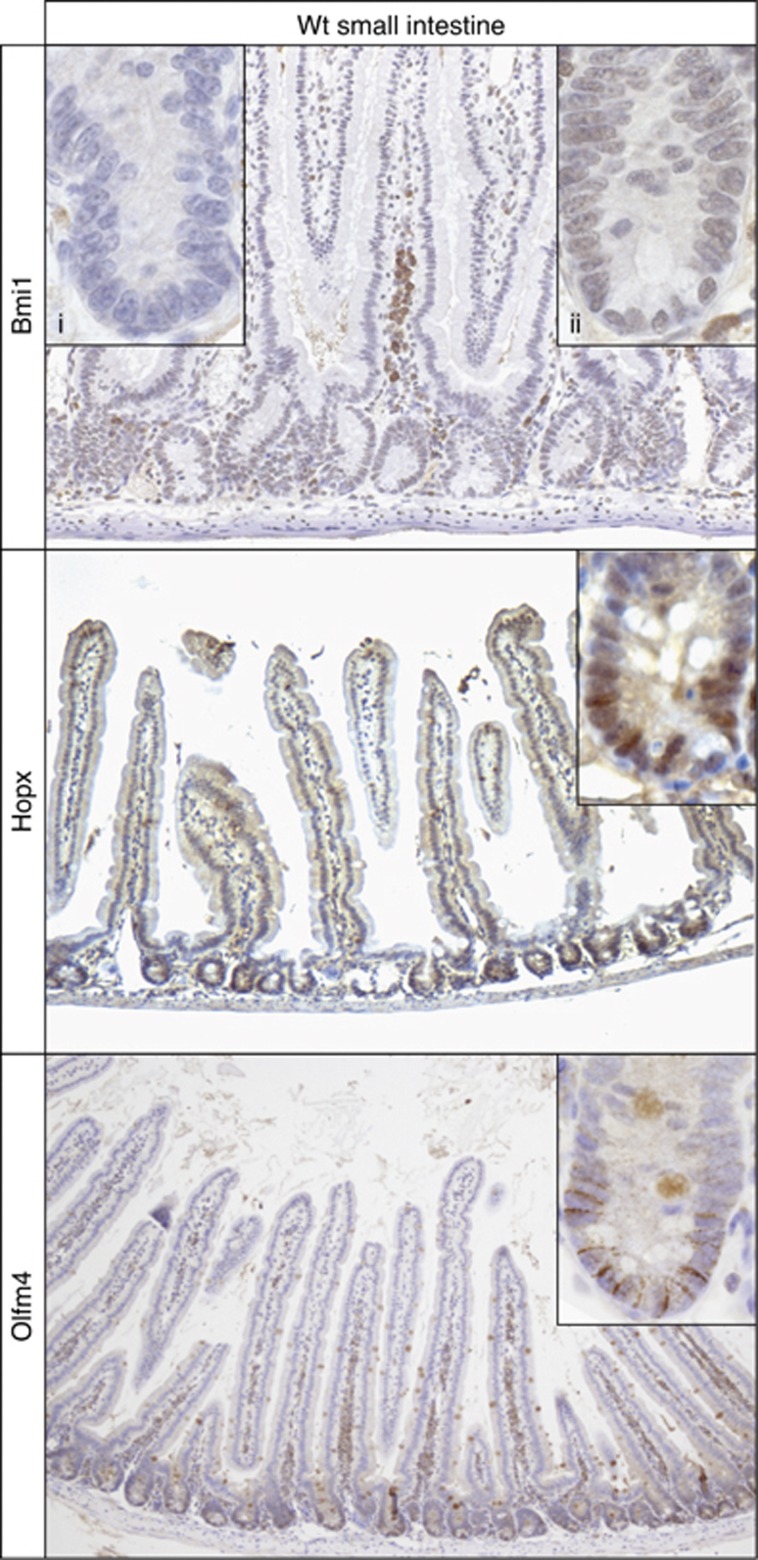

We next addressed the expression pattern of the encoded proteins. A recent study documented that Lrig1 protein expression is highest in Lgr5+ stem cells and forms an extended expression gradient along the crypt axis in perfect accordance to its mRNA expression pattern (Wong et al, 2012). Tert enzymatic activity has been shown to be highest in CBC stem cells (Schepers et al, 2011). Immunohistochemistry for Hopx, Bmi1 (including Bmi1-mutant crypts as negative control) and Olfm4 revealed the expected extended expression domains as observed at the mRNA level (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Protein expression pattern of Bmi1 and Hopx. Immunohistochemistry was performed on small intestine of wild-type mice. Bmi1-stained cells at equal levels throughout the crypt. Control staining (insert i) was performed on small intestine of Bmi1-knockdown mice. A representative crypt is shown in insert (ii). Hopx showed nuclear staining in the bottom half of the crypt. A representative crypt is shown in the insert. Olfm4 expression was restricted to the crypt bottom.

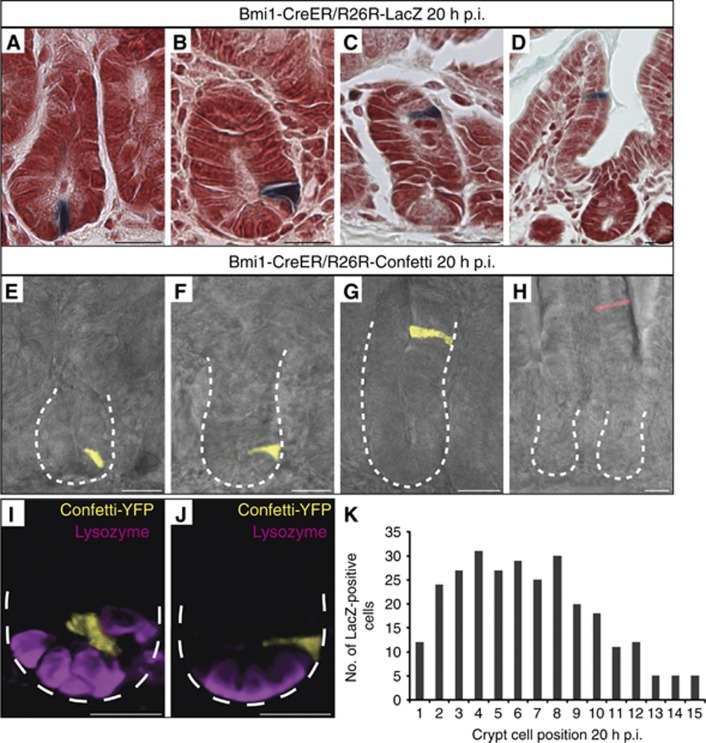

Since these data are in direct disagreement with previous studies, we focused on the prototypic quiescent/‘+4’ marker Bmi1. We next asked, if the reported tracing initiation percentage of 95% (86/91 crypts) at the ‘+4/+5’ position might be a specific feature of the Bmi1-ires-CreER knock-in mouse (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008). To revisit this model, we crossed the single colour R26R-LacZ reporter or the multi-colour R26R-confetti reporter into this strain. Cre activity was induced by a single injection of tamoxifen in adult offspring and the first 10 cm of the small intestine were analysed, exactly as performed previously (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008). In both models, the reporters became visible at 20 h after tamoxifen induced Cre activation (p.i.), as reported (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008; Figure 8). Tracing events at this time point typically presented as single cells. In contrast to the original report, we noted that these single marked cells appeared at any position along the crypt-villus axis, for example, at the CBC location between Paneth cells (Figure 8A, E and I), at the +4 position directly above the Paneth cells (Figure 8B, F and J), higher up in crypts (Figure 8C and G) and even on the villus flanks (Figure 8D and H). When the number of marked cells at each cell position along the crypt axis was quantified, a substantial number of tracing events was found to occur within the CBC compartment (positions 1–4), and that almost 70% of tracing events occurred in TA cells (position +5 and higher). We even noted rare tracing events at 20 h p.i. in fully differentiated Goblet cells (Supplementary Figure S7A and B), as well as Paneth cells at crypt bottoms (Supplementary Figure S7C and D). No tracings were seen in uninduced mice. As predicted from these observations, most tracing events evolved into ‘signature’ tracings from TA cells at 2 and 3 days p.i.: small trains of differentiated cells that move upwards within the crypt (Supplementary Figure S7F, G and J) or already reached the flanks of the villi, to be ‘washed’ out within the next 24–48 h by apoptosis at villus tips (Supplementary Figure S7H, K and L). More rarely, we observed extended tracing within crypts, typically initiating in the Lgr5 stem cell compartment (e.g., Supplementary Figure S7E and I).

Figure 8.

Bmi1 marks individual cells irrespective of position along the crypt villus axis. (A–D) LacZ staining of Bmi1-CreER/R26R-LacZ mice 20 h after induction (p.i.). Positive cells were present at various positions along the crypt-villus axis. (E–H) Confocal imaging of Bmi1-CreER/R26R-Confetti mice 20 h p.i. Crypt outline is shown by a white dotted line. Bmi1-tracing cells are shown in yellow or red and bright field image is shown in grey. (I–J) 3D representations of (E) and (F). Bmi1+ cells are marked by Confetti-YFP (yellow), Paneth cells are visualized by lysozyme staining (purple). Crypt outline is shown by a white dotted line. (K) Quantification of the number of marked cells at each position along the crypt axis.

Discussion

In this study, we have attempted to generate a definite Lgr5 stem cell signature by using two different array platforms, thus measuring both mRNA and protein levels in FACS-sorted, highly pure cell populations. The double transcriptomic approach indeed resulted in an increase (>6-fold) in the number of identified stem cell-enriched genes compared with our previous report (van der Flier et al, 2009a). As a poor correlation between mRNA and protein levels has been documented before in several biological systems including mouse embryonic stem cells (Lu et al, 2009), analyses at both levels appear to be of importance. The proteomic analysis of a limited number of FACS-sorted stem cells necessitates a strategy that balances comprehensive proteome coverage and quantitative precision with sensitive sample preparation. The use of metabolically labelled rodents has been reported (Wu et al, 2004; Krüger et al, 2008). Although precision and sensitivity of the procedure is excellent, it is a high-cost technology considering the large number of animals required to obtain sufficient material. Alternatively, label-free approaches can be used, though multiple replicas are necessary to control technical variability (Luber et al, 2010). Often, such an approach precludes the use of multiple separations, reducing protein identifications and limiting comprehensiveness. Here, we combined a highly sensitive chemical labelling method with a refined SCX fractionation to quantify proteome changes (Munoz et al, 2011). The analysis of 300 000 cells (∼30 μg of total protein) resulted in the quantification of 4817 unique proteins from which 278 showed enrichment in the stem cells.

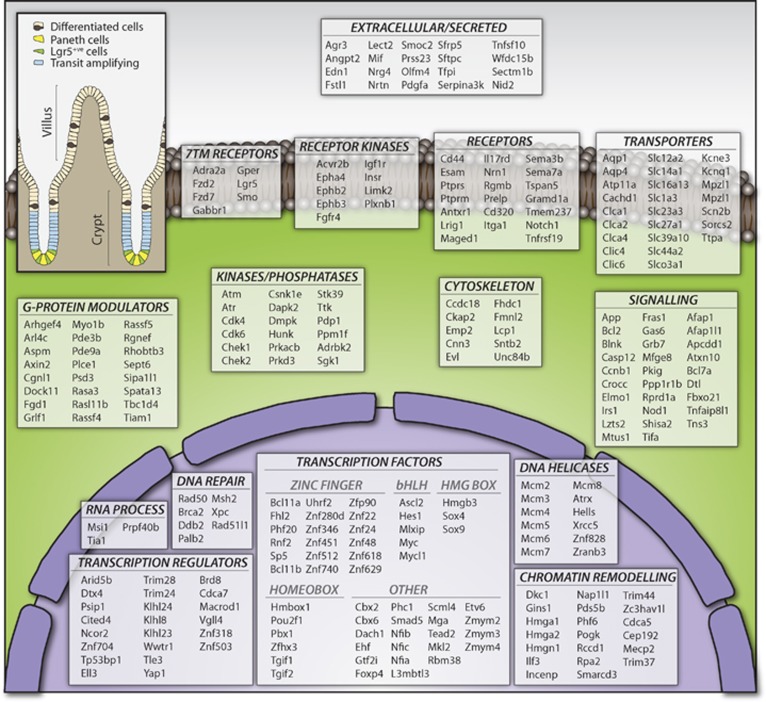

Comparison of the proteomic data with the mRNA data revealed an overall good correlation. Even the most differentially expressed genes such as Olfm4, Nav1 and Hmgsc2 exhibited an excellent agreement between mRNA and protein levels. The combination of the proteomic data with the transcriptomic data further refined the stem cell signature. Genes only enriched at the mRNA level (n=27) could be removed from the list, whereas a substantial number of genes (n=147) could be added to the signature, as a clear enrichment at both mRNA and protein levels was detected. The applied ‘minimum 2 out of 3’ strategy outperformed the use of absolute cutoff values or statistical tests and resulted in the definition of a comprehensive ISC signature comprising 510 genes. An overview of the GO categories in which the Lgr5 signature genes fall is given in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Functional classification of genes from the intestinal stem cell signature. Genes comprising the intestinal stem cell signature were functionally classified with PANTHER (www.pantherdb.org) by molecular function. Annotations were manually checked and, when applicable, re-assigned to a different category based on literature. The figure represents 279 genes for some of the most functionally relevant categories. The complete list containing all 510 genes enriched in stem cells can be found in Supplementary Table S12.

One of the immediate uses of this resource is the definition or validation of stem cell markers. For the alternative stem cell of the small intestinal crypt, the quiescent/‘+4’ cell, the molecular markers Bmi1, Tert, Hopx and Lrig1 have been reported (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008; Montgomery et al, 2011; Takeda et al, 2011; Powell et al, 2012). We readily detect expression of all four genes in Lgr5+ CBC cells and find no evidence for specific enrichment of any of these markers outside the Paneth cell/Lgr5 stem cell zone. Our observations confirm that Bmi1 is expressed at relatively low, yet equal levels in all crypt cells (Itzkovitz et al, 2011). Furthermore, our reassessment of the Bmi1-ires-CreER knock-in mouse does not agree with the originally published observation that this mouse marks a unique population of Lgr5 negative quiescent/‘+4’ cells (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008). Bmi1 tracing can initiate in any cell type in the crypt, as predicted by our expression array, single-molecule marker analysis and immunohistochemistry. Of note, the same observation concerning the initiation of Bmi1-based lineage tracing was reported in Tian et al (2011) and the broad protein expression pattern of Bmi1 has been independently documented in Takeda et al (supporting Figure 7 in Takeda et al, 2011). Lrig1 and Hopx expression is highest in Lgr5high cells and tapers off further up in the crypt. Finally, Tert is expressed at very low levels throughout the crypt, as we published previously (Schepers et al, 2011). From these data, we conclude that lineage tracing or organoid-culturing experiments using these mouse models will report characteristics of Lgr5+ stem cells. While the existence of a quiescent reserve stem cell population should not be excluded (Li and Clevers, 2010), our data imply that Bmi1, Hopx, Tert and Lrig1 cannot be used as a marker for such cells. Finally, de Sauvage and colleagues have shown in an elegant genetic model that selectively killed Lgr5 cells can be replenished from Lgr5–/Bmi1+ cells elsewhere in the crypt (Tian et al, 2011). Both Potten and colleagues (Marshman et al, 2002) and Cheng and Leblond (1974), the discoverers of the CBC cell, have postulated that TA cells above the stem cell zone may display plasticity upon damage, and revert to stem cells. Given our observation that all cells in the crypt express Bmi1, it appears attractive to revive this concept of TA cell plasticity and postulate that they serve as reserve cells upon damage to the stem cell compartment.

In conclusion, the Lgr5+ ISC signature reported in this study represents a rich resource for functional studies of Lgr5 stem cells in the intestine and for comparative studies on other candidate ISC populations.

Materials and methods

Cell sorting

Freshly isolated small intestines of Lgr5-ki mice were incised along their length and villi were removed by scraping. The tissue was then incubated in PBS/EDTA (5 mM) for 5 min. Gentle shaking removed remaining villi and intestinal tissue was subsequently incubated in PBS/EDTA for 30 min at 4°C. Vigorous shaking yielded free crypts that were incubated in PBS supplemented with Trypsin (10 mg/ml) and DNAse (0.8 μg/μl) for 30 min at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were spun down, resuspended in SMEM (Invitrogen) and filtered through a 40-μm mesh. GFP-expressing cells were isolated using an MoFlo cell sorter (DAKO). Approximately 300 000 cells were sorted per population for each experiment.

Transcriptomic analysis

The Affymetrix analysis was performed on a genome-wide mRNA expression platform (Affymetrix HT MG-430 PM Array Plate). Labelled material from clearly distinguishable GFPhigh and GFPlow populations (Lgr5 stem cell and daughter cell populations, respectively) was hybridized individually on single colour arrays. Three independent experiments were performed, resulting in six arrays (three for GFPhigh and three for GFPlow). The expression data extracted from the raw files were normalized with the RMA-sketch algorithm from Affymetrix Power Tools. Data were analysed using the R2 web application, which is freely available at http://r2.amc.nl. In total, 20 819 unique genes are represented on the array. If a gene was represented with multiple probes, we selected the one with the highest average expression level across the six arrays. Expression levels were averaged for the three GFPhigh and GFPlow arrays, respectively, and ratios calculated. ANOVA with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing was applied to all 20 819 genes. An FDR-corrected P-value (ANOVA) of <0.1 together with an expression difference of >2-fold (log2 of 1) as well as an average expression level in the GFPhigh arrays >20 was defined as a threshold for significantly changed genes.

For Agilent arrays, 4 × 44K Agilent Whole Mouse Genome dual color Microarrays (G4122F) were used. Two independent experiments were performed. In the first, GFPhigh and GFPlow populations (Lgr5 stem cell and daughter cell populations, respectively) were hybridized directly against each other on two-colour arrays. Two replicates were performed in dye swaps to compensate for dye bias, resulting in four individual arrays. For the second experiment, GFP-positive cells were arbitrarily sorted in five fractions ranging from highest GFP levels (fraction 5+) to the lowest GFP fraction (1+). The lower GFP fractions 1+ to 4+ were hybridized each against the highest GFP fraction 5+. The experiment was performed with dye swaps, resulting in eight individual arrays. Array data were normalized using Feature Extraction (V.9.5.3, Agilent) and data analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft). Features were flagged and not further analysed, if signal intensities for both the Cy3 and Cy5 channel did not pass the Feature Extraction Filter ‘Significant and Positive’ or ‘Well above Background’. For the first experiment (GFPhigh versus GFPlow), 21 720 features passed this filter and were additionally found in all four arrays. Some genes are contained multiple times within these 21 720 features. To remove redundancy, we selected for each gene the feature with the highest expression level (average of Cy3 and Cy5 channel over all four arrays). This resulted in a list of 13 967 unique genes. The average of all four arrays was used to compare mRNA expression ratios with Affymetrix arrays or protein expression ratios. SAM (Statistical Analysis of Microarrays) analysis was used to calculate q-values (FDR-adjusted P-values) for all 13 967 genes (Tusher et al, 2001). A q-value of <0.05% together with an average expression difference of >2-fold (log2 of 1) was defined as a threshold for significantly changed genes.

Microarray data for the GFPhigh and GFPlow Agilent and Affymetrix arrays are publicly available in the GEO repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under the super-series record GSE33949. The Agilent arrays containing the five fraction data can be found under the record GSE36497.

Proteomic analysis

Lgr5+ stem cells and daughter cells (Supplementary Table S6) were pelleted by centrifugation at 2500 g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell lysis was performed in a buffer containing 8 M urea in a solution of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.2 with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Proteins (∼30 μg) were first reduced/alkylated and digested for 4 h with Lys-C. The mixture was then diluted four-fold and digested overnight with trypsin. Resulting peptides were chemically labelled with stable isotope dimethyl labelling as described previously (Boersema et al, 2009). Briefly, Lgr5+ stem cells peptides were labelled with a mixture of formaldehyde-H2 and sodium cyanoborohydride (‘light’ reagent). For daughter cells peptides, formaldehyde-D2 with cyanoborohydride (‘heavy’ reagent) was used. A second biological replica experiment was performed where labels were swapped. The ‘light’ and ‘heavy’ dimethyl labelled samples were mixed in 1:1 ratio based on total peptide amount, which was determined by running an aliquot of the labelled samples on a regular LC-MS/MS run and comparing overall peptide signal intensities. Prior to the MS analysis, samples were fractionated to reduce the complexity using a strong cation exchange (SCX) system as described earlier (Pinkse et al, 2008). The SCX system consisted of an Agilent 1100 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) using a C18 Opti-Lynx (Optimized Technologies, Oregon OR) trapping cartridge and a Zorbax BioSCX-Series II column (0.8 mm i.d. × 50 mm length, 3.5 μm). The labelled peptides were dissolved in 10% FA and loaded onto the trap column at 100 μl/min and subsequently eluted onto the SCX column with 80% acetonitrile and 0.05% FA. SCX Solvent A consists of 0.05% formic acid in 20% acetonitrile while solvent B was 0.05% formic acid, 0.5 M NaCl in 20% acetonitrile. The SCX salt gradient is as follows: 0–0.01 min (0–2% B); 0.01–8.01 min (2–3% B); 8.01–18.01 min (3–8% B); 18.01–28 min (8–20% B); 28–38 min (20–40% B); 38–44 min (40–90% B); 44–48 min (90% B); 44–74 min (0% B). A total of 50 SCX fractions (1 min each, i.e., 50-μl elution volume) were collected and dried in a vacuum centrifuge.

Nanoflow LC-MS/MS was carried out by coupling an Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies) to an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, Bremen, Germany) as described previously (Frese et al, 2011). Collected SCX fractions were dried, reconstituted in 10% formic acid and delivered to a trap column (AquaTM C18, 5 μm (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA); 20 mm × 100-μm inner diameter, packed in-house) at 5 μl/min in 100% solvent A (0.1 M acetic acid in water). Next, peptides eluted from the trap column onto an analytical column (ReproSil-Pur C18-AQ, 3 μm (Dr Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch, Germany); 40 cm × 50-μm inner diameter, packed in-house) at 100 nl/min in a 90-min or 3-h gradient from 0 to 40% solvent B (0.1 M acetic acid in 8:2 (v/v) acetonitrile/water) depending on sample amount and complexity. Eluted peptides were introduced by ESI into the mass spectrometer that was operated in a data-dependent acquisition mode. After the survey scan (30 000 FHMW), the 10 most intense precursor ions were selected for subsequent fragmentation in a data-dependent decision tree as described before (Frese et al, 2011) using HCD (essentially beam type CID), ETD-IT and ETD-FT activation techniques. In brief, doubly charged peptides were subjected to HCD fragmentation and higher charged peptides were fragmented using ETD. The normalized collision energy for HCD was set to 35%. ETD was enabled with supplemental activation and the reaction time was set to 50 ms for doubly charged precursors.

Raw files were processed with Proteome Discoverer (Beta version 1.3, Thermo). Peptide identification was carried out with Mascot 2.3 (Matrix Science) against a concatenated forward-decoy SwissProt mouse database (version 56.2, 31 862 entries). The following parameters were used: 50 p.p.m. precursor mass tolerance, 0.6 Da fragment ion tolerance for ETD-IT, and 0.02 Da for HCD and ETD-FT modes. Up to three missed cleavages were accepted, carbamidomethylation of cysteines was set up as fixed modification whereas methionine oxidation and ‘light’ and ‘intermediate’ dimethyl labels as variable modifications. Mascot results were filtered afterwards with 10 p.p.m. precursor mass tolerance, Mascot Ion Score >20 and a minimum of 7 residues per peptide. Using these criteria, FDRs were calculated: 1.26% for biological replica 1 (1577 decoy PSMs and 242 439 forward PSMs) and 1.46% for biological replica 2 (1806 decoy PSMs and 247 070 forward PSMs). Panther was used to classify proteins by GO terms. The official gene symbols (HUGO) were used to compare the transcriptomic and proteomic data sets.

The MS data associated with this manuscript can be downloaded from the website ProteomeCommons.org under the Tranche hash:

hbKgQ0wYwJjRbUNEwGnJcANtg7LMLC4l4gDpCySnM4snf7uCT4dy27ReNSI3MTUqJOFLoCYneGOcz7Qn3rKvQdhb9GQAAAAAAAAGfw==

mRNA in-situ hybridization

RNA in-situ hybridization was performed as described before (Gregorieff et al, 2005). The in-situ hybridization probes utilized in this study correspond to Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC) clones obtained through Source BioScience.

Generation of the Smoc2 knock-in mouse

Smoc2-EGFP-ires-CreERT2 knock-in (Smoc2-ki) mice were generated by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells targeting an EGFP-ires-CreERT2 cassette at the translational start site of Smoc2 (Figure 5A). Details of embryonic stem cell targeting are described elsewhere (Barker et al, 2007). In adult mice, Cre-recombinase was activated in Smoc2+/ki;RosaLacZ reporter+/Rep mice by IP injection of tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648). Mice were maintained within the animal facilities at the Hubrecht Institute, and experiments were performed according to the national rules and regulations of the Netherlands.

qPCR analyses

qPCR analyses were performed as described before (van der Flier et al, 2009a). cDNA was synthesized from 0.5 μg of total RNA of five (1+ to 5+) GFP-positive cell fractions (see Transcriptomic Analysis above) from an independent sorting experiment as for the arrays from Lgr5-EGFP-ires-CreERT2 mice using random primers, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Primer sequences are given in Supplementary Table S14.

Single molecule mRNA in-situ hybridization

Single molecule mRNA in-situ hybridization was performed as described before (Raj et al, 2008). Probe libraries consisted of typically 48 probes 20 bp of length complementary to the coding sequence. Probe libraries for Lgr5, Olfm4, Tert and Bmi1 can be found elsewhere (Itzkovitz et al, 2011). Probe libraries for Hopx and Lrig1 can be found in Supplementary Table S13. Each crypt was analysed based on 12 z-stacks spaced 0.3 μm apart and multiple crypts (Lgr5: 337 crypts, Bmi1: 168 crypts, mTert: 30 crypts, Olfm4: 30 crypts, Hopx: 30 crypts, Lrig1: 30 crypts).

Immunohistochemistry

Bmi1 (Abcam, #ab14389) was diluted 1:100 in TBST/10% goat serum. Control staining was performed on small intestine of Bmi1-knockdown mice (Maarten van Lohuizen, NKI, The Netherlands; to be described elsewhere). Hopx (Santa Cruz, #sc-30216) was diluted 1:500 in PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed using citrate buffer. Olfm4 (Abcam, #ab85046) was diluted 1:200 in TBST/5% goat serum.

Bmi1-ires-CreER lineage tracing

Bmi1-ires-CreER (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008), R26R-LacZ (Soriano, 1999) and R26R-Confetti (Snippert et al, 2010a) mice were described previously. Tamoxifen induction was performed according to Sangiorgi and Capecchi (2008). In brief, Bmi1-CreER/R26R-LacZ and Bmi1-CreER/R26R-Confetti mice, 5–9 weeks of age, were injected with 9 mg tamoxifen (20 mg/ml) per 40 g body weight. Standard techniques were applied for immunohistochemistry. Sectioning and staining of Bmi1-CreER/R26R-Confetti was performed according to Snippert et al (2011). Lysozyme antibody used was Polyclonal Rabbit Anti-Human (Dako A0099). Secondary antibody used was Alexa 647, Goat anti-Rabbit (Invitrogen 56834A). Confocal images were acquired using a Leica Sp5 AOBS microscope. Images were processed using ImageJ, Photoshop and Volocity (Perkin-Elmer).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Harm Post and Marco Hennrich for technical support on the SCX and Maaike van den Born as well as Harry Begthel for histological support. DES is supported by a grant from CBG; AGS and JvE by a grant from Ti Pharma/T3-106; MvdW by a grant from EU/Health F4-2007-200720; B-KK by a grant from Advanced ERC 232814. OJS, KM and SR are funded by a Cancer Research UK core grant; AvO, SI and KSK are supported by the NIH/NCI Physical Sciences Oncology Center at MIT (U54CA143874).

Author contributions: All authors performed the experiments under the guidance of AJRH and HC; JM and SM performed the MassSpec; DES, MvdW, RVo, JK and RVe performed the expression profiling; DES and AGS performed the mRNA in-situs; DES performed the qPCR and Hopx IHC; AGS performed the Bmi1-ki experiments; MvdW performed the FACS; B-KK and DES constructed the Smoc2-ki mouse; SI, KSK and AvO performed the single molecule in-situs; JvE performed mouse experiments; SR, KM and OS performed the Bmi1 and Olfm4 IHC; NB constructed the Lgr5-ki mouse; DES, JM, AJRH and HC wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, van de Wetering M, Snippert HJ, van Es JH, Sato T, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, van den Brink S, Korving J, Abo A, Peters PJ, Wright N, Poulsom R, Clevers H (2010) Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 6: 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, Clarke AR, Sansom OJ, Clevers H (2009) Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 457: 608–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H (2007) Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449: 1003–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastide P, Darido C, Pannequin J, Kist R, Robine S, Marty-Double C, Bibeau F, Scherer G, Joubert D, Hollande F, Blache P, Jay P (2007) Sox9 regulates cell proliferation and is required for Paneth cell differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol 178: 635–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerknes M, Cheng H (2006) Intestinal epithelial stem cells and progenitors. Meth Enzymol 419: 337–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersema PJ, Raijmakers R, Lemeer S, Mohammed S, Heck AJR (2009) Multiplex peptide stable isotope dimethyl labeling for quantitative proteomics. Nat Protoc 4: 484–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Leblond CP (1974) Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. V. Unitarian Theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am J Anat 141: 537–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese CK, Altelaar AFM, Hennrich ML, Nolting D, Zeller M, Griep-Raming J, Heck AJR, Mohammed S (2011) Improved peptide identification by targeted fragmentation using CID, HCD and ETD on an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos. J Proteome Res 10: 2377–2388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorieff A, Pinto D, Begthel H, Destrée O, Kielman M, Clevers H (2005) Expression pattern of Wnt signaling components in the adult intestine. Gastroenterology 129: 626–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramis A-PG, Begthel H, van den Born M, van Es J, Jonkheer S, Offerhaus GJA, Clevers H (2004) De novo crypt formation and juvenile polyposis on BMP inhibition in mouse intestine. Science 303: 1684–1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzkovitz S, Lyubimova A, Blat IC, Maynard M, van Es J, Lees J, Jacks T, Clevers H, van Oudenaarden A (2011) Single-molecule transcript counting of stem-cell markers in the mouse intestine. Nat Cell Biol Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22119784[accessed 30 November 2011] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaks V, Barker N, Kasper M, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, Clevers H, Toftgård R (2008) Lgr5 marks cycling, yet long-lived, hair follicle stem cells. Nat Genet 40: 1291–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayahara T, Sawada M, Takaishi S, Fukui H, Seno H, Fukuzawa H, Suzuki K, Hiai H, Kageyama R, Okano H, Chiba T (2003) Candidate markers for stem and early progenitor cells, Musashi-1 and Hes1, are expressed in crypt base columnar cells of mouse small intestine. FEBS Lett 535: 131–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 305: 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger M, Moser M, Ussar S, Thievessen I, Luber CA, Forner F, Schmidt S, Zanivan S, Fässler R, Mann M (2008) SILAC mouse for quantitative proteomics uncovers kindlin-3 as an essential factor for red blood cell function. Cell 134: 353–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Clevers H (2010) Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science 327: 542–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Markowetz F, Unwin RD, Leek JT, Airoldi EM, MacArthur BD, Lachmann A, Rozov R, Ma/’ayan A, Boyer LA, Troyanskaya OG, Whetton AD, Lemischka IR (2009) Systems-level dynamic analyses of fate change in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature 462: 358–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber CA, Cox J, Lauterbach H, Fancke B, Selbach M, Tschopp J, Akira S, Wiegand M, Hochrein H, O’Keeffe M, Mann M (2010) Quantitative proteomics reveals subset-specific viral recognition in dendritic cells. Immunity 32: 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshman E, Booth C, Potten CS (2002) The intestinal epithelial stem cell. Bioessays 24: 91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RK, Carlone DL, Richmond CA, Farilla L, Kranendonk MEG, Henderson DE, Baffour-Awuah NY, Ambruzs DM, Fogli LK, Algra S, Breault DT (2011) Mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase (mTert) expression marks slowly cycling intestinal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 179–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz J, Low TY, Kok YJ, Chin A, Frese CK, Ding V, Choo A, Heck AJR (2011) The quantitative proteomes of human-induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells. Mol Syst Biol 7: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TA, Lobenhofer EK, Fulmer-Smentek SB, Collins PJ, Chu T-M, Bao W, Fang H, Kawasaki ES, Hager J, Tikhonova IR, Walker SJ, Zhang L, Hurban P, de Longueville F, Fuscoe JC, Tong W, Shi L, Wolfinger RD (2006) Performance comparison of one-color and two-color platforms within the MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project. Nat Biotechnol 24: 1140–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkse MWH, Mohammed S, Gouw JW, van Breukelen B, Vos HR, Heck AJR (2008) Highly robust, automated, and sensitive online TiO2-based phosphoproteomics applied to study endogenous phosphorylation in Drosophila melanogaster. J Proteome Res 7: 687–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potten CS, Booth C, Tudor GL, Booth D, Brady G, Hurley P, Ashton G, Clarke R, Sakakibara S, Okano H (2003) Identification of a putative intestinal stem cell and early lineage marker; musashi-1. Differentiation 71: 28–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potten CS, Kovacs L, Hamilton E (1974) Continuous labelling studies on mouse skin and intestine. Cell Tissue Kinet 7: 271–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AE, Wang Y, Li Y, Poulin EJ, Means AL, Washington MK, Higginbotham JN, Juchheim A, Prasad N, Levy SE, Guo Y, Shyr Y, Aronow BJ, Haigis KM, Franklin JL, Coffey RJ (2012) The pan-ErbB negative regulator Lrig1 is an intestinal stem cell marker that functions as a tumor suppressor. Cell 149: 146–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, van den Bogaard P, Rifkin SA, van Oudenaarden A, Tyagi S (2008) Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nat Methods 5: 877–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi E, Capecchi MR (2008) Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nat Genet 40: 915–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H (2009) Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459: 262–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers AG, Vries R, van den Born M, van de Wetering M, Clevers H (2011) Lgr5 intestinal stem cells have high telomerase activity and randomly segregate their chromosomes. EMBO J 30: 1104–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanhausser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M (2011) Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473: 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons BD, Clevers H (2011) Strategies for homeostatic stem cell self-renewal in adult tissues. Cell 145: 851–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, Haegebarth A, Kasper M, Jaks V, van Es JH, Barker N, van de Wetering M, van den Born M, Begthel H, Vries RG, Stange DE, Toftgård R, Clevers H (2010b) Lgr6 marks stem cells in the hair follicle that generate all cell lineages of the skin. Science 327: 1385–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, Schepers AG, Delconte G, Siersema PD, Clevers H (2011) Slide preparation for single-cell-resolution imaging of fluorescent proteins in their three-dimensional near-native environment. Nat Protoc 6: 1221–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T, van Es JH, van den Born M, Kroon-Veenboer C, Barker N, Klein AM, van Rheenen J, Simons BD, Clevers H (2010a) Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143: 134–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P (1999) Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 21: 70–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Jain R, LeBoeuf MR, Wang Q, Lu MM, Epstein JA (2011) Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science 334: 1420–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JT, Canelos P, Luyten FP, Moos M Jr (2009) Xenopus SMOC-1 Inhibits bone morphogenetic protein signaling downstream of receptor binding and is essential for postgastrulation development in Xenopus. J Biol Chem 284: 18994–19005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Biehs B, Warming S, Leong KG, Rangell L, Klein OD, de Sauvage FJ (2011) A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature 478: 255–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G (2001) Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 5116–5121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier LG, Haegebarth A, Stange DE, van de Wetering M, Clevers H (2009b) OLFM4 is a robust marker for stem cells in human intestine and marks a subset of colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology 137: 15–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier LG, van Gijn ME, Hatzis P, Kujala P, Haegebarth A, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, Guryev V, Oving I, van Es JH, Barker N, Peters PJ, van de Wetering M, Clevers H (2009a) Transcription factor achaete scute-like 2 controls intestinal stem cell fate. Cell 136: 903–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel G (2003) Stem cells. ‘Stemness’ genes still elusive. Science 302: 371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VWY, Stange DE, Page ME, Buczacki S, Wabik A, Itami S, van de Wetering M, Poulsom R, Wright NA, Trotter MWB, Watt FM, Winton DJ, Clevers H, Jensen KB (2012) Lrig1 controls intestinal stem-cell homeostasis by negative regulation of ErbB signalling. Nat Cell Biol 14: 401–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CC, MacCoss MJ, Howell KE, Matthews DE, Yates JR 3rd (2004) Metabolic labeling of mammalian organisms with stable isotopes for quantitative proteomic analysis. Anal Chem 76: 4951–4959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yui S, Nakamura T, Sato T, Nemoto Y, Mizutani T, Zheng X, Ichinose S, Nagaishi T, Okamoto R, Tsuchiya K, Clevers H, Watanabe M (2012) Functional engraftment of colon epithelium expanded in vitro from a single adult Lgr5(+) stem cell. Nat Med Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22406745 [accessed 19 March 2012] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Gibson P, Currle DS, Tong Y, Richardson RJ, Bayazitov IT, Poppleton H, Zakharenko S, Ellison DW, Gilbertson RJ (2009) Prominin 1 marks intestinal stem cells that are susceptible to neoplastic transformation. Nature 457: 603–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.