Abstract

Objectives

This study set out to pursue means of reducing mismatch in schoolboy rugby players. The primary objective was to determine whether application of previously reported thresholds of height and grip strength could be used to distinguish those 15-year-old boys appropriate to play under-18 school rugby from their peers. A secondary objective was to obtain normative data for height, weight and grip strength and to assess the variation within that data of current schoolboy rugby players.

Design

Cross-sectional cohort study.

Setting

3 Scottish schools and ‘Regional Assessment Centres’ organised by the Scottish Rugby Union.

Participants

472 rugby playing youths aged 15 years (Regional Assessment Centres) and 382 schoolboys aged between 12 and 18 years (three schools).

Outcome measures

Height, weight and grip strength.

Results

97% of 15-year-olds achieved the height and grip strength thresholds based on previous reported values. Larger mean values and wide variation of height, weight and grip strength were recorded in the schoolboy cohort. However, using the mean values of the cohort of 17-year-olds as a new threshold, only 7.7% of 15-year-olds would pass these thresholds.

Conclusions

Large morphological variation was observed in schoolboy rugby players of the same age. Physical maturity tests described in earlier literature as pre-participation screening for contact sports were not applicable to current day 15-year-old rugby players. New criteria were measured and found to be better at identifying those 15-year-old players who had sufficient physical development to play senior school rugby.

Article summary

Article focus

Potential for physical mismatch between schoolboy rugby players and assessment of established maturity testing methods to try to reduce this mismatch, and modifications based on new population data.

Key messages

Large morphological variation was observed in schoolboy rugby players of the same age.

Previously reported parameters of physical maturity were not suitable to assess the current schoolboy rugby playing population.

New criteria, based on current players, were found to better differentiate 15-year-old players as to their suitability to play senior school rugby, with the aim of reducing physical mismatch.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Evidence that current screening parameters are inadequately sensitive.

Current population data collected to describe cohorts of schoolboy rugby players.

Application of current data allows better assessment of physical maturity to inform the decision of whether an individual could play senior school rugby.

There is an urgent need to establish a robust system for recording injuries in order to substantiate the screening system.

Introduction

Since the advent of professionalism in 1995, injury rates in Rugby Union have increased in the adult game,1 2 and although unproven, the same is suspected in schoolboy rugby.3 4 Serious neck and spinal injuries are thought to be rare in youth rugby.5 In 2010, however, Allan reported an unprecedented increase in the incidence of catastrophic spinal injuries among teenage rugby players admitted to the Queen Elizabeth National Spinal Injuries Unit in Glasgow,6 disproportionate to the school-age playing population when compared with data for the other home nations.7 Physical mismatch between players was highlighted as a possible contributory factor in these injuries.

The avoidance of mismatch is traditionally addressed by playing schoolboys in their year groups; however, year groups combine at 16 to compete in senior (under-18) school rugby. In contrast to the other home nations, Scottish schoolboys aged 15 years are regularly involved in senior school rugby, in part due to the relatively small playing population and also due to the tradition of leaving senior school at an earlier age.

It is well recognised that within any selected year group, a wide spectrum of physical maturity exists,8 and there is evidence that this is at its maximum between the ages of 13 and 15 years, during which peak growth velocity usually occurs. In some American states, a maturity assessment is used as pre-participation screening for some collision sports,9–11 and there is some evidence to suggest that matching athletes for physical maturity is associated with a reduced injury rate.12 Previous studies have correlated specified height and grip strength values with the attainment of physical maturity as defined by the Tanner scale.12–14 A similar maturity assessment was introduced by the Scottish Rugby Union (SRU) in the hope that, by differentiating 15-year-old players by physical maturity, the risk of mismatch in this age group may be reduced.

The aim of this study was to determine whether the application of previously reported threshold measurements of height and grip strength could be used to distinguish those 15-year-olds who might safely play senior (under-18) school rugby. A secondary objective was to obtain normative data for physical characteristics (height, weight and grip strength) and to assess the variation within that data of current day schoolboy rugby players to investigate whether it might give a more sensitive assessment of physical maturity.

Materials and methods

At the beginning of the 2009–2010 season, the SRU ruled that no 15-year old should play in the front row in senior school rugby. Any 15-year old wishing to play senior school rugby in an alternative position was required to undergo a maturity assessment (based on previously reported values).15 This was introduced as part of an intervention to improve safety in the game (‘Are you ready to play rugby’) and had been recommended by a subgroup of the Scottish Committee for Orthopaedics and Trauma in response to the increasing number of serious neck injuries observed in schoolboy rugby in Scotland.

An initial cohort of boys aged 15 years who wished to play senior school rugby was assessed by trained medical personnel, at several SRU-organised Regional Assessment Centres across Scotland. A specific testing protocol was followed for grip strength, height and weight. Grip strength was assessed with hand-held dynamometers (Jamar, Asimow Engineering Co, Los Angeles, California, USA), calibrated as per the manufacturer's recommendations. Testing was undertaken as recommended by the American Association of Hand Surgeons with the subjects seated, the elbow flexed at 90° and the wrist in neutral. After an initial trial, three attempts were made and the mean calculated. Standardised verbal encouragement was given during the test; the boys were blinded to the values achieved until the test had been completed. Both hands were tested and the greater mean value used for analysis. Height and weight were measured using a Leicester Height Measure and Seca 761 Approved Medical Mechanical Floor Scales (Class III), respectively. To be regarded as physically mature, and therefore able to play in the under-18 age group, players had to fulfil the following physical conditions: height >165 cm and grip strength >25 kg.15

In the second part of this study, a cohort of 382 rugby playing boys aged 12–18 years were assessed at three Scottish rugby playing secondary schools between December 2009 and October 2010. Height, weight and grip strength were measured by trained personnel using the same standardised protocol and equipment as in the initial cohort. Ethical approval was obtained from the Fife and Forth Valley Ethics Committee (REC No: 09/S501/62) to undertake this part of the study. Individual consent was obtained from the boys who participated and countersigned by their parents where appropriate. Supervision of the study was by members of the Scottish Committee for Orthopaedics and Trauma subgroup.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS (V.14, IBM). Data were manually assessed for normality with histograms. Descriptive data are reported as means with SDs as a measure of dispersion. Differences between age grades were assessed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, General Linear Model). A Bonferroni correction was applied to reduce the chance of a type 1 error associated with multiple testing. Effect sizes are reported with the Eta2 statistic. Post hoc tests were performed with Tukey's HSD test to assess individual comparisons. Statistical significance was accepted as p<0.05.

Results

Four hundred and seventy-two boys aged 15 years presented to the SRU-arranged Regional Assessment Centres. Their mean height was 177 cm (SD 7 cm, range 156–199 cm), mean weight 74.4 kg (SD 13.1 kg, range 46.0–127.1 kg) and mean grip strength 44.2 kg (SD 7.7 kg, range 20.5–80.0 kg). Using the criteria established from previous studies as an indication of physical maturity (height >165 cm, grip strength >25 kg), 97.2% were deemed physically mature and thus eligible to play in the under-18 age group.

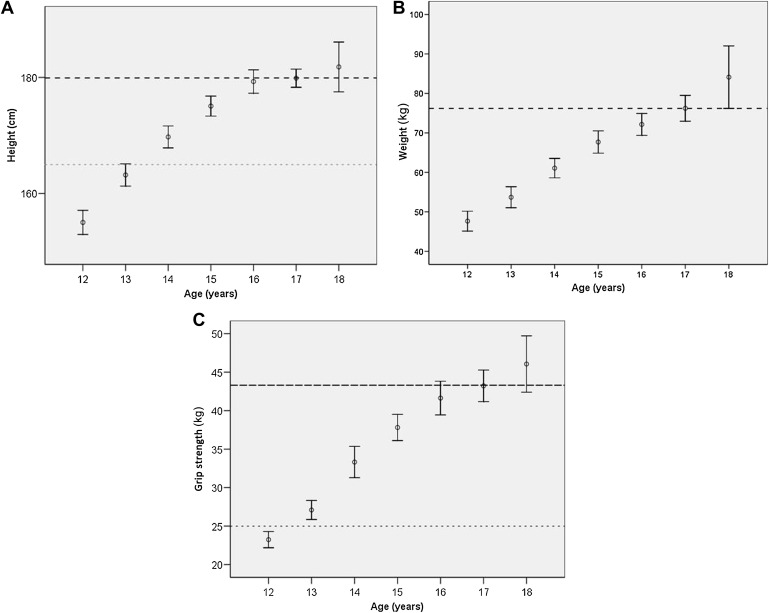

Three hundred and eighty-two schoolboy rugby players aged 12–18 years were similarly assessed in the second cohort study at the three schools. Mean height, weight and grip strength generally increased with age, reflecting growth (table 1 and figure 1).

Table 1.

Physical parameters by age grade, mean (SD)

| Age (years) | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Participants (n) | 54 | 66 | 63 | 65 | 55 | 62 | 17 |

| Height (cm) | 155 (7.6) | 163 (7.8) | 170 (7.5) | 175 (7.0) | 179 (7.5) | 180 (6.2) | 182 (8.1) |

| Weight (kg) | 48 (9.2) | 54 (10.8) | 61 (9.8) | 68 (11.4) | 72 (10.2) | 76 (12.8) | 84 (14.9) |

| Grip strength (kg) | 23 (3.9) | 27 (5.0) | 33 (8.1) | 38 (6.9) | 42 (8.1) | 43 (8.1) | 46 (6.9) |

Figure 1.

Assessed physical parameters with cut-off thresholds. Mean values with 95% CIs for (A) height, (B) weight and (C) grip strength of the 382 schoolboys assessed. The heavy dashed line represents the 17-year-old mean and allows direct comparison of the number of younger boys likely to achieve this value. The lighter dashed line reflects the previously used criteria (height and grip strength only) demonstrating the poor reflection of these previous scores on current day Scottish schoolboy rugby players.

Variation in all physical parameters (height, weight and grip strength) was determined by age group (ANOVA). Modest to large effect sizes were observed for each parameter (table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of age on variance in assessed physical parameters (analysis of variance)

| F (6, 382) | Significance, p value | η2 | |

| Height | 92.27 | <0.001 | 0.597 |

| Weight | 58.14 | <0.001 | 0.483 |

| Grip strength | 73.33 | <0.001 | 0.541 |

Post hoc testing (Tukey's HSD test) demonstrated significant differences between each variable in every age group up to the age of 15 years. No significant differences were observed between the 16, 17 and 18 years age groups for height or grip strength nor between the 15, 16, 17 and 18 years age brackets for weight (table 3).

Table 3.

Inter-age group comparisons, mean difference (95% CI)

| Difference in age | Height | p Value | Weight | p Value | Grip strength | p Value |

| 12–13 | 8.18 (4.21 to 12.15) | 0.000 | 6.05 (0.07 to 12.03) | 0.045 | 3.85 (0.10 to 7.60) | 0.039 |

| 13–14 | 6.55 (2.74 to 10.36) | 0.000 | 7.37 (1.63 to 13.10) | 0.003 | 6.23 (2.63 to 9.82) | <0.001 |

| 14–15 | 5.32 (1.49 to 9.14) | 0.001 | 6.63 (0.87 to 12.39) | 0.013 | 4.50 (0.89 to 8.11) | 0.05 |

| 15–16 | 4.22 (0.26 to 8.19) | 0.028 | 4.45 (−1.52 to 10.42) | 0.292 | 3.82 (0.08 to 7.56) | 0.042 |

| 16–17 | 0.58 (−3.43 to 4.59) | 0.1 | 4.08 (−1.97 to 10.14) | 0.417 | 1.59 (−2.19 to 5.37) | 0.876 |

| 17–18 | 1.94 (−4.13 to 8.01) | 0.964 | 7.90 (−1.26 to 17.05) | 0.142 | 2.84 (−2.88 to 8.56) | 0.763 |

Differences were, however, apparent between the 15 and 17 years age groups for height (difference in mean =4.80, 95% CI 0.97 to 8.65), weight (difference in mean =8.53, 95% CI 2.73 to 14.34) and grip strength (difference in mean =5.41, 95% CI 1.79 to 9.03).

As the median age of boys playing senior school rugby in Scotland was 17 years, we assessed how many 15-year-olds would meet the mean height, weight and grip strength of the 17-year age group: 180 cm height, 76 kg weight and 43 kg grip strength. The numbers meeting each of these criteria, and various combinations of the criteria, are shown in table 4. Only 13.8% of the 15-year-olds had the mean grip strength and height of a 17-year old, while including weight as an additional requirement reduced this figure to 6.2%.

Table 4.

Consequences of testing 15-year-old boys (n=65) against the mean values for 17-year-old boys (n=62; height 180 cm, weight 76 kg and grip strength 43 kg)

| Number above 17-year-old mean | Number below 17-year-old mean | % Meeting requirement | |

| Grip strength + height | 9 | 56 | 13.80 |

| Grip strength + weight | 5 | 60 | 7.70 |

| Grip strength, height + weight | 4 | 61 | 6.20 |

The effect of applying thresholds to the cohort data is highlighted in figure 1, where the heavy dashed line reflects the mean values recorded for the 17-year-old group and the light dashed line the historical values (where appropriate). Of note is that current day 14-year-olds (95% CI of mean) meet the historical height requirement, and 13-year-olds (95% CI of mean) meet the historical grip strength requirement.

Discussion

The popularity of rugby as a sport for teenagers is threatened by concerns about the potential for serious injury.16 17 The professional game has become more physical, and injuries in elite players are commonplace.18 19

It is reasonable to suggest that where younger players compete with older age groups in contact sports they are exposed to higher contact forces that may be compounded if they are not physically matched. This was the reasoning behind incorporating physical assessments as part of the ‘Are you ready to play rugby’ programme introduced by the SRU in 2009 in response to the rising incidence of serious spinal injuries in schoolboy rugby in Scotland. During puberty, there is an increase in body weight, principally due to muscle mass, which can be quantified by measuring grip strength.15 Our analysis focused on 15-year-old boys as this age represents the watershed between junior and senior school rugby with some individuals playing at either or both levels.

The results of applying previous threshold values for height and grip strength failed to discriminate between a large cohort of current day 15-year-old rugby players with almost all (97.2%) deemed as physically mature. It may be that our study population was a more athletic group than that on which the published parameters were based, namely youths in a juvenile correctional facility in Washington State.15 However, our schoolboy cohort results were similar to normative data for American adolescents reported in a previous study.20 In contrast, the cohort of 15-year-olds tested in the SRU Regional Assessment Centres were not comparable to previous normative data and perhaps represent a subset of aspiring athletes likely to be stronger and bigger than average for their year group. The players tested in this group all wished to play at a more senior level and are likely to be self-selecting. Even so, and of more concern, the range of values for height (1.56–1.99 m), weight (46–127 kg) and grip strength (21–80 kg) recorded in this group of 15-year-old boys is remarkable and demonstrates the substantial variability in physical development irrespective of age even within this subgroup of boys. This is supported by the wide SDs in both the SRU Regional Assessment Centre cohort and our schoolboy cohort samples and also the CIs surrounding the mean difference between age groups for all assessed parameters in the schoolboy study (table 3).

Normative data on the physical attributes of adolescent rugby players in the literature are limited, and it was felt that this was fundamental to distinguishing between different players of the same age. While significant differences in height, weight and grip strength are evident across age groups in the schoolboy study (ANOVA, table 2), post hoc testing reveals initial year on year significant differences only up until the age of 15 years. Thereafter, the trend of increasing mean values continues in weight and grip strength, but mean height increases are seen to level off over 16 years (figure 1).

Height was previously recognised21 as an important determinant of physical maturity with the period of peak growth around the ‘growth spurt’ associated with an increased risk of injury. Peak height velocity occurs at a median age of 14 years in North American boys, with the 95% CI extending from 11.5 to 15.5 years.22 It is then not surprising that height is less likely to be a discriminator when the 15-year age group, at the upper limit of the growth spurt, is being assessed. From the normative data obtained, it seemed more logical to compare the height, weight and grip strength of 15-year-olds with the means of those age groups they would encounter if they played in senior school rugby. As 17 years is the median age of senior school rugby (16–18-year group), the mean values for a 17-year old were chosen as threshold values, which a 15-year old should achieve if he were to enjoy a degree of physical compatibility with these older players, hopefully reducing his risk of injury. Table 4 highlights the effect of applying the mean values of the 17-year-old boys to the 15-year-old age group. When the different combinations of height, weight and grip strength were assessed, height proved to be the least discriminatory, as predicted. It has been recorded that there is a group of taller boys who, while regarded as pubertally mature, do not possess the muscular strength of peers of similar height.15 It was therefore decided that grip strength and weight should be selected as the key parameters for testing. Using these parameters alone, 7.7% of 15-year-olds in this cohort achieved the mean weight and grip strength of a 17-year old.

While mismatch is recognised as an issue internationally, neither maturity nor grip strength testing is routinely tested in the major rugby playing countries. In New Zealand, both age and weight are taken into account in banding for youth rugby. Players who are significantly heavier than their peers may play at a more senior grade and underweight individuals may play down an age grade, although variation does exist between different districts. South African youth rugby is banded according to age, with players only able to play within a certain age group if their age falls within 2 years of that group. The BokSmart23 rugby safety initiative was launched by the South African Rugby Union in 2009 to combat a comparatively high rate of catastrophic injuries, both in youth rugby and in senior rugby. This was a similar programme to the RugbySmart initiative in New Zealand,24 which commenced in 2001 and has been shown to reduce the incidence of spinal injuries.25 BokSmart includes comparison of individuals with normative data for age groups, including body mass, fitness tests and some basic strength tests. Guidelines for players wishing to play out with their age group are well defined, requiring full rugby-specific assessments by qualified sports practitioners, letters from conditioning coaches, team doctors and coaches, confirming the suitability of the player. A similar approach exists in Australia with streaming according to age group up to U19 level, and players being unable to compete more than 2 years above their respective age group.26 Those who wish to play up beyond the 2-year window require their coach to fill out an exemption form addressing issues, such as level of experience, playing position, use of strength training, and perceived level of maturity. In none of these countries do any objective criteria exist for physical testing.

Currently, the SRU have adopted the condition that any 15-year old wishing to play under-18 rugby, in a position other than the front row, has to achieve the mean weight and grip strength of 17-year-old players. Front row players aged 15 years are not allowed to play in the under-18 age group; this decision was based on reports in the literature that serious neurological damage was more common following neck injury sustained in the scrum in UK schoolboys rather than the tackle.7 Specified under-16 age group rugby exists in some countries, and the delay this imparts on the progress of 15-year-olds into senior school rugby is logical, particularly as this may coincide with a time in their physical development where there is greatest variation in physical maturity. To date, our focus has been on the 15-year age group. With further data collection, it may be that criteria could be identified for all age bands, with players of similar physical development playing together as they mature at differing rates. Potentially, this could identify more developed individuals who should play in older age groups, thus reducing the risk of injury to their age peers or immature individuals who should play in younger age groups, reducing their own risk of injury.

In the absence of robust injury data, but confronted with an upsurge in serious neck injury in Scotland, it was felt that the introduction of maturity assessment in schoolboy rugby was a valuable adjunct to other measures that have been taken to increase safety. To date since the inception of these measures, no schoolboy rugby player with a serious neck injury has been admitted to the National Spinal Injuries Unit in Glasgow. It is accepted, however, that the screening method we are proposing is hypothetical without any injury data to support its efficacy. It is, however, based on current population data involving schoolboy rugby players, applying concepts established in American schools contact sports, based on the only literature available on this subject.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that maturity testing using previously reported parameters fails to differentiate between current day 15-year old Scottish schoolboy rugby players. Matching schoolboys for weight and grip strength, introducing a safety margin based on current population data, where younger players wish to compete above their age group is more likely to be an effective method of reducing mismatch.

Reducing the risk of injury in contact sports should be a universal aim, and it will only be achieved once we know accurately the size and severity of the problem. Previous authors have expressed concerns regarding the wide variation in shape and size of same-aged schoolboys. We suggest that inclusion of indicators of physical maturity within an injury surveillance framework is important if we are to establish the risks associated with mismatch of age grade players. Until such data are available, it would seem logical to try and minimise mismatch, which is what we have set out to achieve with this initiative.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the staff at the three secondary schools visited, particularly the heads of department for physical education. Thanks must also be paid to the continued support from the Scottish Rugby Union, and in particular to the efforts of Nick Rennie and Dr James Robson. The authors also thank the doctors, physiotherapists, medical students and research personnel for the organisation of testing and gathering of the data. Special thanks must go to Deborah MacDonald, Gavin MacPherson, Sally-Anne Phillips and Robert Wallace.

Footnotes

To cite: Nutton RW, Hamilton DF, Hutchison JD, et al. Variation in physical development in schoolboy rugby players: can maturity testing reduce mismatch? BMJ Open 2012;2:e001149. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001149

Contributors: RWN, DFH, JDH, HS and JGBM were involved in the conception and study design. All authors were involved in data collection. DFH performed the analysis, MJM drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the draft manuscript and approved for submission.

Funding: The first cohort of testing was funded by the Scottish Rugby Union. The second cohort of schools-based testing received support from the Hearts and Balls charity to purchase testing equipment.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Fife and Forth Valley (REC No 09/S501/62).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data are held in a secure database at the University of Edinburgh, any party wishing to access unpublished data should discuss with the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Quarrie KL, Hopkins WG. Changes in player characteristics and match activities in Bledisloe Cup rugby union from 1972 to 2004. J Sports Sci 2007;25:895–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garroway WM, Lee AJ, Hutton SJ, et al. Impact of professionalism on injuries in rugby union. Br J Sports Med 2000;34:348–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haseler CM, Carmont MR, England M. The epidemiology of injuries in English youth community rugby players. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:1093–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntosh AS, McCrory P, Finch CF, et al. Head, face and neck injury in youth rugby: incidence and risk factors. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:188–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emery CA. Injury prevention in paediatric sport-related injuries: a scientific approach. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:64–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allan DB, Brydone AS. Spinal Injuries in Scottish Youth Rugby. Glasgow: Presentation COMOC, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maclean JG, Hutchison JD. Serious neck injuries in U19 rugby union players: an audit of admissions to spinal injury units in Great Britain and Ireland. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:591–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silver JR. The impact of the 21st century on rugby injuries. Spinal Cord 2002;40:552–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caine DJ, Broekhoff J. Maturity assessment: a viable preventive measure against physical and psychological insult to the young athlete? Phys Sportsmed 1987;15:67–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grafe MW, Paul GR, Foster TE. The preparticipation examination for high school and college athletes. Clin Sports Med 1997;16:569–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/vipf2/football.htm (accessed 22 Nov 2011).

- 12.Kreipe RE, Gewanter HL. Physical maturity screening for participation in sports. Pediatrics 1985;75:1076–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Backous DD, Friedl KE, Smith NJ, et al. Soccer injuries and their relation to physical maturity. Am J Dis Child 1988;142:839–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanner JM. Growth of bone, muscle, and fat during childhood and adolescence. In: Lodge ME, ed. Growth and Development of Mammals. London: Butterworths, 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backous DD, Farrow JA, Friedl K. Assessment of pubertal maturity in boys, using height and grip strength. J Adolesc Health Care 1990;11:497–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boufous S, Finch CF, Bauman A. Parental safety concerns - a barrier to sport and physical activity in children? Aust N Z J Public Health 2004;28:482–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicholl JP, Coleman P, Williams BT. The epidemiology of sports and exercise related injury in the United Kingdom. Br J Sports Med 1995;29:232–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooks JH, Kemp SP. Injury-prevention priorities according to playing position in professional rugby union players. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:765–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller CW, Ashton T, Brooks JH, et al. Injury risks associated with tackling in rugby union. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:159–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathieowitz V, Wiemer DM, Federman SM. Grip and pinch strength: norms for 6 to 19 yr-olds. Am J Occup Ther 1986;40:705–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caine DJ, Broekhoff J. Maturity assessment: a viable preventive measure against physical and psychological insult to the young athlete? The Physician and Sports Medicine 1987;15:57–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanner JM, Davies PS. Clinical longitudinal standards for height and height velocity for North American children. J Pediatr 1985;107:317–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boksmart http://www.sarugby.co.za/boksmart/default.aspx (accessed 22 Nov 2011).

- 24.RugbySmart http://www.nzrugby.co.nz/the_game/safety/rugbysmart (accessed 22 Nov 2011).

- 25.Quarrie KL, Gianotti SM, Hopkins WG, et al. Effect of a nationwide injury prevention programme on serious spinal injuries in New Zealand rugby union: ecological study. BMJ 2007;334:1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Australian Rugby Union Policy http://www.rugby.com.au/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=2hjJABFRanE%3d&tabid=1970 (accessed 22 Nov 2011).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.