Abstract

The acute sensitivity to conformation exhibited by amide hydrogen exchange reactivity provides a valuable test for the physical accuracy of model ensembles developed to represent the Boltzmann distribution of the protein native state. A number of molecular dynamics studies of ubiquitin have predicted a well-populated transition in the tight turn immediately preceding the primary site of proteasome-directed polyubiquitylation Lys 48. Amide exchange reactivity analysis demonstrates that this transition is 103-fold rarer than these predictions. More strikingly, for the most populated novel conformational basin predicted from a recent 1 ms MD simulation of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (at 13% of total), experimental hydrogen exchange data indicates a population below 10−6. The most sophisticated efforts to directly incorporate experimental constraints into the derivation of model protein ensembles have been applied to ubiquitin, as illustrated by three recently deposited studies (PDB codes 2NR2, 2K39 and 2KOX). Utilizing the extensive set of experimental NOE constraints, each of these three ensembles yields a modestly more accurate prediction of the exchange rates for the highly exposed amides than does a standard unconstrained molecular simulation. However, for the less frequently exposed amide hydrogens, the 2NR2 ensemble offers no improvement in rate predictions as compared to the unconstrained MD ensemble. The other two NMR-constrained ensembles performed markedly worse, either underestimating (2KOX) or overestimating (2K39) the extent of conformational diversity.

Keywords: Protein ensemble, Hydrogen exchange, Continuum electrostatics, Protein flexibility

1. Introduction

Determination of the most probable conformation of a protein in solution has long been a central focus of structural biology. X-ray diffraction provides the most detailed accurate experimental data, albeit for proteins constrained in a crystal lattice. At the highest resolution, mean positions of most individual heavy atoms are determined to within 0.1 to 0.2 Å, in principle without requiring a priori assumptions about bond geometries or packing interactions, although in practice guided by standard force field parameterizations. Solution NMR methods provide a substantially smaller set of experimental constraints so that the force fields used in the structure determination process provide a proportionately larger contribution to the final set of model conformations. Indeed de novo protein folding algorithms have advanced to the level that limited NMR experimental data, most notably chemical shifts, can be used as an effective filter to weed out incompatible conformations from the search tree of the folding algorithm [1].

In turning from the determination of a single most probable conformation to the problem of structurally characterizing the conformational ensemble, the dilemma of experimental underdetermination becomes dramatically more severe. Nearly all of the relevant experimental data are drawn from measurements of ensemble-averaged parameters, and if the structural interpretation of that data is to go beyond the assumption of a single dominant conformation, a model representation of the correct Boltzmann-distributed conformational ensemble is explicitly or implicitly assumed.

There are three basic approaches to applying specific experimental data to the prediction of a protein conformational ensemble. Most straightforwardly, a model ensemble can be generated independently of these experimental data by molecular dynamics, Monte Carlo or related simulation techniques that is initially assumed to approximate a proper Boltzmann distribution. The resultant set of conformations is then used to predict the experimental data with the expectation that the discrepancies will serve to inform improvements in the conformational modeling technique. Alternatively, such a model ensemble can be assumed to deviate significantly from a proper Boltzmann distribution. A set of experimental data can then be used as a filter to select a subset of conformations from among the initial ensemble so as to engineer a distribution that yields predictions more consistent with those experimental data, a sample-and-select paradigm. The third approach directly incorporates the experimental data into the conformational sampling algorithm, typically by introducing pseudo-energy penalty functions into an MD simulation with the anticipation that the resultant conformational sampling will more closely approach a Boltzmann distribution.

Due to the severely underdetermined character of the experimental ensemble modeling problem, the data filtration and data restraint approaches can only be realistically assessed if a substantial portion of structurally discriminating experimental data is set aside to enable an independent analysis of the final model ensemble. As is well known from protein crystallographic studies, the setting aside of a subset of diffraction data for conducting a Rfree [2] assessment of the final structural model provides a valuable tool for determining the reliability of that model, even for this situation in which the number of experimental constraints are comparable to the number of structural variables.

It is crucial to consider the degree to which the experimental data can discriminate among different model distributions. On one hand, the theoretical interpretation of these data must be sufficiently well determined so that a precise prediction of the experimental data can be derived on the basis of a defined set of protein model conformations. This, in turn, requires any useful conformational sampling approach to specify the individual protein conformations to a precision sufficient to enable prediction of the relevant experimental data. Few types of experimental data are highly sensitive to both the dispersion of a conformational distribution as well as to its averaged structure.

The dependence of the amide exchange reaction on exposure of the amide hydrogen to the solvent phase has long been recognized to provide a sensitivity to rare conformational transitions that is unmatched by any other experimental technique [3]. Protein hydrogen exchange data have conventionally been expressed in terms of “protection factors” in which the observed exchange rates are normalized against the exchange rates of simple model peptides under analogous conditions. Under the commonly observed EX2 kinetic condition, the resultant ratio of rates is then interpreted as the equilibrium constant for the conformational transition that exposes the amide to the solvent phase [4]. Central to this analysis is the implicit assumption that the reactivity of the solvent-exposed amide is insensitive to the protein conformation, an assumption that stands in stark contrast to the basic tenets of chemical enzymology. The often substantial shifts in pK values for enzyme-bound substrates, cofactors and active site sidechains are well recognized to play critical roles in explaining reactivity in acid/base catalyzed reactions. Similarly, protein hydrogen exchange reactivities have been shown to vary exponentially with the electrostatic potential at each amide site, yielding up to billion-fold differences in rates among amide hydrogens that are exposed to solvent in high resolution X-ray structures [5,6]. Charge interactions up to 14 Å distant have been found to significantly modulate protein amide exchange reactivity [5].

The present study draws upon the fact that the conformational dependence of hydroxide-catalyzed peptide exchange reactivity can be predicted by continuum dielectric methods with a reasonably robust degree of accuracy. The quality of these predictions is limited by three distinct sources of uncertainty: the hydrogen exchange rate measurement, the modeling of the Boltzmann-distributed conformational distribution and the prediction of exchange reactivity based on this conformational distribution. The majority of the hydrogen exchange data used for these analyses are derived from magnetization transfer-based NMR exchange experiments in which the 1H water magnetization is selectively excited and then the rate of exchange of these protons onto individual protein amide sites is measured. Using a relaxation compensated version [7] of the CLEANEX-PM [8,9] experiment for samples at a series of pH values, we have reported the hydroxide-catalyzed exchange rate constants kOH− for 56 amide hydrogens that are exposed to solvent in the high resolution structures of ubiquitin, FK506 binding protein (FKBP12), chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 (CI2) and Pyrococcus furiosus rubredoxin [6]. Forty six of these amides are distant from ionizable groups undergoing titration and yield constant log kOH− values at two or more pH values with an overall uncertainty of 0.053. The pH dependence of exchange for the amides near the histidine sidechains of ubiquitin and FKBP12 exhibits a Henderson–Hasselbach modulation that reflects the known pK values of those sidechains. As a result, the amide exchange rate constants for these residues can be determined for the imidazolium and neutral imidazole charge states of the protein [6].

For the ubiquitin exchange analysis considered below, we have determined the hydroxide-catalyzed exchange rate constants for the more slowly exchanging amides using 1H isotope exchange-in measurements [10]. In contrast to the more familiar 1H isotope exchange-out protocol, the exchange rates are measured in a 1H2O solution which eliminates nearly all of the solvent isotope effects that complicate the quantitative interpretation of the conventional isotope exchange experiment. Furthermore, measurement of CLEANEX-PM data on the 1H exchange-in sample facilitates direct comparison to the magnetization transfer-based exchange data sets. The log kOH− values for Thr 22 and Leu 50 of ubiquitin were determined by both the CLEANEX-PM and 1H exchange-in experiments and these independent measurements agreed to within 0.08 [10].

Robust prediction of amide exchange reactivity from a set of Boltzmann-distributed protein conformations takes advantage of the short lifetime of the peptide anion intermediate formed during the exchange reaction. As proposed by Eigen nearly 50 years ago [11], nitrogen- and oxygen-bound hydrogens generally react with hydroxide ion in a diffusion limited process. The fraction of forward-reacting exchange encounters is Ki/(Ki + 1), where Ki is the equilibrium constant for the transfer of a proton from the amide to the hydroxide ion. As a result, the kinetic acidity monitored by the exchange reaction directly indicates the thermodynamic acidity. Alkyl amides have been experimentally demonstrated to react with Eigen ‘normal’ acid kinetics [12,13].

While rare exceptions occur [14], the vast majority of protein amides are less acidic than water so that the peptide anion is quenched by virtually any collision with a water molecule. Direct measurement of the lifetime of a peptide anion is problematic. However, spectroscopic analysis of photoactivated strong acids and bases have demonstrated lifetimes near 10 ps [15–17], which has been argued [15] to be rate-limited by water reorganization. Pure water has a time constant of 8.3 ps at 25 °C for its primary Debye dielectric relaxation mode [18]. As a result, minimal change in protein conformation will occur during the lifetime of the peptide anion and slower conformational reorganization transitions cannot efficiently contribute to the dielectric shielding of that anion. This in turn implies that the hydrogen exchange experiment provides a “snapshot” of the ensemble distribution such that the experimental exchange rates can be directly estimated from averaging the predicted reactivity of each conformation in the model ensemble.

The electrostatic free energy of a low dielectric Born ion suspended in a high dielectric medium is approximately inversely proportional to the internal dielectric value (i.e., ΔGelec = −(1/εint−1/εext)Q2/2R where Q is charge and R is radius [19]). Given the limited contribution from protein conformational transitions, electronic polarizability can be expected to dominate the contribution of the protein interior to the dielectric shielding of the solvent-exposed amide. As a result, continuum dielectric estimations of electrostatic free energy are considerably more robust for predicting peptide ionizations than they are for the more familiar sidechain pK calculations predictions [20–24] in which the protein conformational transitions that shield these long-lived charge states are approximated by a uniform volume dielectric.

Poisson–Boltzmann calculations using the CHARMM22 [25] atomic charge and radius parameters in the DelPhi algorithm [26] were applied to a set of N-acetyl-[X-Ala]-N-methylamides and N-acetyl-[Ala-Y]-N-methylamides in the conformations of these dipeptide sequences as reported in the high resolution Protein Coil Library of Rose and colleagues [27]. For every dipeptide sequence, the peptide acidities predicted for the various conformations spanned approximately a million-fold range [28,29]. With the exception of the N-acetyl-[Ala-Asp]-N-methylamides, the wide range of conformer acidities is dominated by the backbone dihedral angles that determine the relative orientation of the two peptide groups neighboring the site of ionization. An equally large sidechain conformational dependence is predicted for the Ala-Asp dipeptides reflecting the strong interaction between the sidechain carboxylate and the mainchain nitrogen when that carboxylate is oriented gauche to the intraresidue amide. Despite the large range in conformer acidities predicted for the various experimentally observed dipeptide conformations, using the Protein Coil Library as a model for the Boltzmann-distributed distribution, the standard sidechain-dependent hydrogen exchange correction factors [30] for the log rates of the nonpolar model peptides can be predicted within a factor of 0.11 with a correlation coefficient r = 0.91 [28]. This discrepancy between the experimental and predicted log rates may be compared to the average grid error of 0.036 for these Poisson–Boltzmann calculations that arises from variable positioning of the molecules upon the lattice used for the finite difference analysis [29].

A useful test of the assumption that conformational reorganization has a negligible effect on the prediction of peptide exchange reactivity is provided by the Ala-Asn and Asn-Ala dipeptides for which this assumption yields an underestimate of 0.2 for the log kOH− values predicted from the Protein Coil Library distribution. In contrast to the comparatively slow rotamer transitions for sp3 – sp3 hybridized bonds, the transitions around the sp3 – sp2 bond linking the Cβ and Cγ atoms can occur in the ps timeframe for the Asn sidechain [31]. By allowing for conformational relaxation around the χ2 sidechain dihedral angle within each χ1 rotamer state, the exchange reactivity predictions for the Ala-Asn and Asn-Ala dipeptides are markedly improved [28].

The amide hydrogens that are exposed to solvent in high resolution X-ray structures exhibit a far larger range of experimental exchange rates than do the simple model peptides. In analyzing the billion-fold range in backbone amide exchange rates observed for P. furiosus rubredoxin, Poisson–Boltzmann calculations were used to estimate the relative magnitude of various contributions to the differential electrostatic free energies of ionizing the solvent-exposed amides [5]. As could be anticipated from the immediately preceding discussion, structurally constraining the backbone conformation around each site of amide ionization allows for the orientation of the neighboring peptide groups to more strongly modulate the acidity of that amide. However, for most of the static solvent-exposed amides of rubredoxin, a larger contribution to ΔGelec arises from the relative spatial distribution of the protein interior as assessed by setting all atomic charges to zero. The degree to which the low dielectric protein volume surrounding each site of ionization is effectively concave or convex results in variations in predicted electrostatic free energy of up to 6 kcal/mol. The magnitude of the ΔGelec contributions arising from the formal charges of the protein varies markedly among the static solvent exposed amides, and generally the formal charge effects were predicted to be larger than those arising from the other sidechain partial charges.

Using single conformations derived from the crystal structures of ubiquitin, FKBP12, CI2 and rubredoxin, the billion-fold range in kOH− values for the 56 static solvent exposed amides were predicted within an rmsd of 7 [6]. The slope of the correlation between the observed and predicted log exchange rates yielded an empirical estimate of the protein internal dielectric of 3 which agrees quite well with an electronic polarizability contribution of at least 2.5 derived by Mertz and Krishtalik [32] from correcting the familiar value of 2.0 obtained from refractive index measurements on typical organic liquids to the 30–40% higher density within the protein interior [33,34]. Use of the OPLS-AA [35] atomic charge and radius parameters yielded similar results to those obtained with the CHARMM22 parameters as could be expected from the close similarity between the electrostatic parameters of these two force fields [6]. In contrast, the atomic charge and radius parameters of the AMBER ff99 [36] and ff03 [37] force fields yielded considerably less accurate hydrogen exchange predictions. Despite the long-standing assumption that deprotonation of an amide gives rise to an imidate ion [38,39], placing the excess negative charge on the carbonyl oxygen provides a dramatically worse prediction of the exchange behavior of these static solvent-exposed amides as compared to placing the excess charge on the amide nitrogen. Using an atomic charge distribution derived from B3LYP DFT calculations at the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set level yielded a modest improvement over the nitrogen-centered charge analysis [6].

As discussed in detail below for the case of ubiquitin, averaging the conformer reactivities over a realistic model of the Boltzmann-distributed distribution can provide a significant improvement in predicting the exchange behavior of the static solvent-exposed amides, as compared to predictions based on a single structural model. More significantly, such ensemble analysis enables exchange predictions for the occasionally exposed sites that are not directly interpretable from the crystallographic structures. Given the robustness with which the exchange reactivity of each protein conformation can be predicted, when the experimental exchange rate of an amide is markedly above that predicted from a model ensemble, inadequate conformational sampling can be inferred since the conformations that give rise to the majority of the experimentally observed reactivity are necessarily under-represented. Conversely, when the model ensemble-based exchange rate calculations yield a substantial overestimation, the conformations that give rise to that elevated prediction are clearly over-represented relative to the Boltzmann distribution.

Ubiquitin offers an unmatched system for examining the utility of peptide acidity analysis for assessing the robustness of conformational ensemble modeling. A number of studies comparing the predictions of protein conformational dynamics that arise from the use of different force fields in MD simulations have utilized ubiquitin and have often differed significantly in their predictions for that protein. Furthermore, ubiquitin has been the subject for the most sophisticated efforts to date for utilizing experimental constraints to improve the performance of MD-based ensemble predictions in terms of both increased structural accuracy and enhanced conformational sampling. As considered in the present study, peptide acidity analysis provides an unambiguous resolution to an ongoing debate regarding the conformational dynamics of the tight turn immediately preceding the primary site of proteasomal-directed polyubiquitylation — Lys 48.

As unconstrained molecular dynamics simulations of the protein native state have begun to sample conformational space beyond the microsecond timeframe, it has become an increasingly critical challenge to establish experimental approaches to demonstrate the degree to which these more extensive simulations reflect a proper Boltzmann distributed sampling of conformational space. As a further test of the utility of peptide acidity analysis, this approach is applied to the multiple conformational basins of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor that have been predicted on the basis of highly extended molecular simulation studies [40].

2. Experimental and computational methods

2.1. Protein sample preparation

Genes for the G47A variant of human ubiquitin were chemically synthesized (Genscript) as modified from the wild type gene sequence, with codon optimization for expression in Escherichia coli [6]. The genes were cloned into the expression vector pET11a and then transformed into the BL21 (DE3) strain (Novagen) for expression. [2H,15N] labeled ubiquitins were expressed in E. coli and purified as previously described [6].

For the 1H exchange-in experiments, the [U–2H,15N]-enriched protein samples were washed into a deuterated buffer by centrifugal ultrafiltration, and the p2H was adjusted to 10 with a sodium carbonate buffer. 1H–15N 2D NMR correlation experiments were carried out to monitor the loss of the amide 1H resonances. After back exchange was completed, the protein samples were equilibrated into a 2H2O buffer containing 6 mM NaH2PO4 and 14 mM Na2HPO4, with sodium chloride added to a final ionic strength of 150 mM. Aliquots of 500 µl for the protein solution were then lyophilized to dryness. Immediately before NMR data collection, each protein sample was rapidly redissolved in 500 µl of 93% 1H2O–7% 2H2O and transferred to an NMR tube.

For the CLEANEX-PM magnetization transfer experiments, aliquots of a [U–2H,15N]-enriched sample were concentrated and then exchanged into a series of buffers, via centrifugal ultrafiltration, to a final protein concentration of ~2 mM. Acetate (for pH values below 6), phosphate (for pH values between 6 and 8), borate (for pH values up to 10), and carbonate (pH values above 10) buffers at 20 mM concentration in 6% 2H2O were adjusted to a total ionic strength of 150 mM with sodium chloride.

2.2. Amide hydrogen exchange measurements

CLEANEX-PM [9] spectra with relaxation compensation [7] were collected on a Bruker Avance DRX 500 MHz spectrometer at 25 °C with mix times of 6.49, 12.98, 21.41, 32.44, and 51.90 ms as previously described [41]. The intensity of each fully relaxed spectrum was estimated by exponential extrapolation of the intensities from the hard pulse reference experiment using relaxation delays of 2.0, 4.0 and 8.0 s.

For each 1H exchange-in sample, a series of 1H–15N 2D TROSY [42] spectra was collected at 25 °C on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz NMR spectrometer. After the time interval between acquisitions of the 1H exchange-in spectra increased beyond a day, CLEANEX-PM magnetization transfer-based measurements were carried out to enable direct correlation with the pH dependence of the CLEANEX-PM measurements [6]. To maximize internal consistency, the previously reported hydrogen exchange measurements on the wild type ubiquitin [10] were repeated using the same buffer solutions as applied to the G47A variant. The presently determined log kOH− values for the 46 wild type ubiquitin residues monitored by CLEANEX-PM measurements agreed with the previously published values within an rmsd of 0.037. The isotope exchange experiments deviated somewhat more with the 26 amides yielding hydroxide-catalyzed exchange log rate constants that are on average 0.15 larger than previously determined.

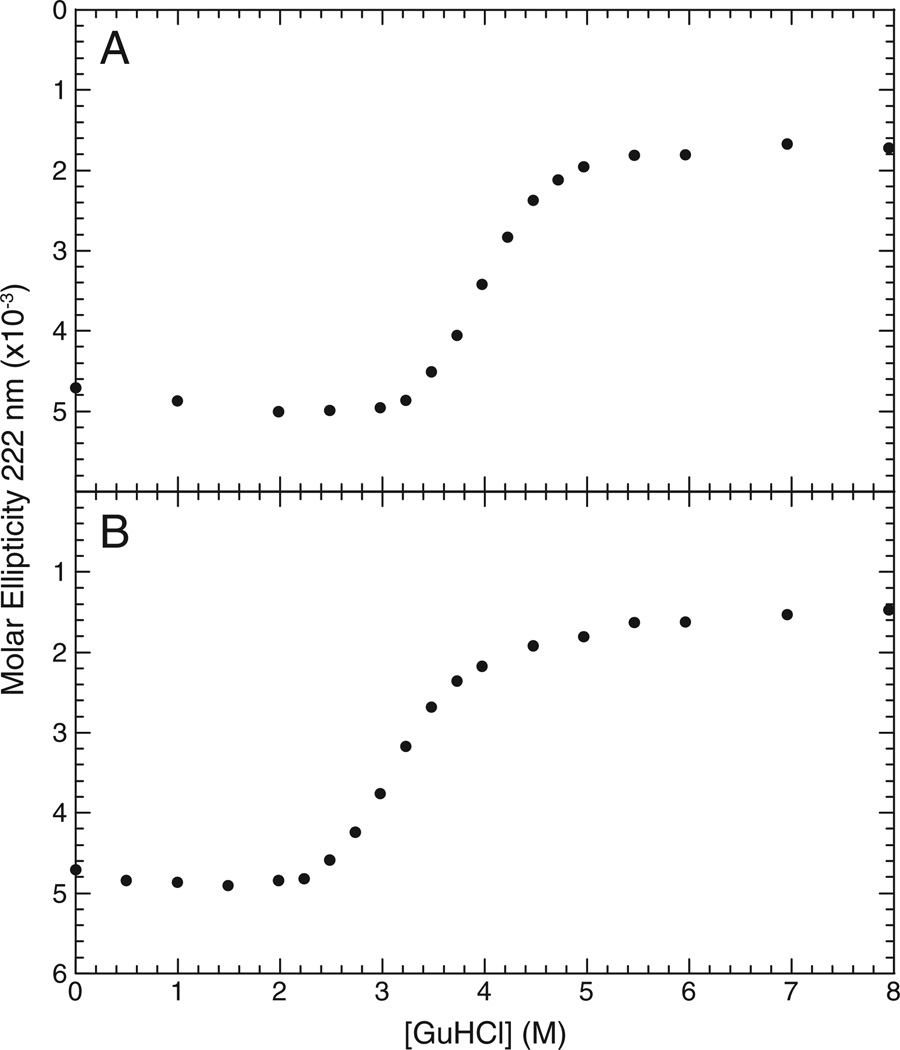

2.3. Circular dichroism measurements

Protein samples were generated by mixing of two solutions of 0 M and 7.95 M guanidine hydrochloride in 10 mM sodium acetate pH 4.0, each containing ubiquitin at 55 µM as determined spectrophotometrically using an extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 1490 M−1 L−1. After several hours of pre-incubation at 25 °C, UV circular dichroism spectra were collected from 300 to 200 nm at 25 °C in a 0.2 cm path length rectangular quartz cuvette using a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier temperature controller. For each sample, a series of five scans was averaged to obtain the ellipticity measurement at 222 nm. Linear baseline correction was applied to the low denaturant range for both the wild type and G47A ubiquitin data, while a shallower linear baseline correction was also applied to the high denaturant range for the G47A ubiquitin data. The data was then analyzed assuming a two-state transition.

2.4. Molecular dynamics simulations

Using the VMD program [43], the X-ray coordinates of the protein and crystallographic waters (PDB code 1UBQ [44]) were imbedded in a water box (52.2 Å × 54.9 Å × 58.0 Å) with at least 10 Å from protein to boundary. VWD was used to add 13 Na+ and 13 Cl− ions for an ionic strength of 150 mM, similar to the experimental conditions. Energy minimization and stepwise heating to 298 K was applied in the NAMD2 simulation package [45] with the CHARMM27 force field [46] and PME electrostatics using a 64 × 64 × 64 grid. The solvent was allowed to equilibrate for 30 ps with the protein heavy atoms and crystallographic waters still constrained using a 5 kcal/mol/Å2 harmonic potential. At this point three separate simulations were initiated with differing random seeds for velocity assignment. After slowly stepping down the harmonic constraints on the protein heavy atoms and crystallographic waters, 30 ns simulations were carried out under NPT conditions using a Langevin temperature damping of 1 ps−1 and a Langevin piston period of 0.1 ps. A 1 fs time-step was applied with switch distance, cutoff and pairlist distances of 10 Å, 12 Å and 14 Å, respectively. The 50 ns BPTI simulation was run under similar conditions starting from the 5PTI X-ray coordinates [47] in a water box (45.9 Å × 48.6 Å × 53.9 Å) with 6 Na+ and 12 Cl− ions added to maintain electroneutrality at an ionic strength near 150 mM.

2.5. Poisson–Boltzmann electrostatic ensemble calculations of backbone amide reactivity

Ensemble electrostatic calculations for the 2NR2 [48] and 2K39 [49] ensembles have been previously described [10,50]. Calculations for the 640 conformations of the 2KOX ensemble [51] were carried out analogously using the SURFV program [52] with the default set of atomic radii [53] to determine the static solvent accessibility. The DelPhi program [26] was used for linear Poisson–Boltzmann predictions of the electrostatic potential of the amide anions for each structure in the ensemble with the CHARMM22 atomic charge and radius values [25] and an internal dielectric value of 3 as previously established by protein hydrogen exchange analysis [6]. The water dielectric equivalence assumption [54] was applied to account for the potentially rapid dielectric response of the sidechain hydroxyl hydrogens of serine and threonine residues.

For all residues in which at least 1% of the conformations exhibit a solvent exposure above 0.5 Å2 for the amide hydrogen, the electrostatic potential was calculated for the individual peptide anions formed by removing the amide hydrogen from the solvent-exposed residue conformations. As internal acidity reference, in each calculation an N-methylacetamide (or N-methylacetamide anion) molecule was added to the continuum dielectric lattice volume distant from the protein molecule [10,28,29]. Using the acidity of water (pKa of 15.7 at 25 °C) and the diffusion-limited reactivity of secondary aliphatic amides with hydroxide ion (2 × 1010 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C [12,13]), the exchange reactivities for each protein amide were then averaged over the conformational ensemble.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Hydrogen exchange analysis of NMR-restrained model conformational ensembles of ubiquitin for well-exposed amides

Several molecular dynamics-based model ensembles of ubiquitin have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank [55] for which the set of conformations are derived so as to predict compatibility with an extensive set of experimental NMR data. To help maintain the conformational distribution close to the most probable state, these ensembles have utilized the highly dense set of 2727 NOE-derived distance restraints reported from the solution structure analysis (PDB code 1D3Z [56]). To shape the magnitude of the predicted local bond vector orientational disorder so as to agree with experimental restraints, these studies have utilized either backbone 15N and methyl 13C NMR relaxation data, that are sensitive to motion faster than overall molecular tumbling, or residual dipolar coupling (RDC) data that are sensitive to a far wider range of frequencies of motion.

De Groot and colleagues (PDB code 2K39 [49]) applied their earlier described CONCOORD algorithm [57] to these NOE restraints so as to generate 500 sets of pairs of ubiquitin structures that together each satisfy the measured NOE data. In their EROS (ensemble refinement with orientational restraints) protocol, a subset of these pairs of structures was selected for predicted consistency with the experimental RDC data. This initial subset was then submitted to multiple rounds of a cycle of simulated annealing followed by re-selection so as to ultimately yield a final set of 116 ubiquitin conformations. Vendruscolo and colleagues introduced the MUMO method for restrained molecular dynamics on ubiquitin in which restraint-derived pseudo-energy terms are used to require the back-calculated NOE effects for pairs of model conformations to monotonically converge toward the experimental values during the course of either 50 or 100 annealing cycles (PDB code 2NR2 [48]). They also introduced 122 NMR relaxation order parameter restraints using a similar protocol so as to generate a model ensemble of 144 conformations. Recently, several of the same authors have reported a 640 member model ubiquitin ensemble utilizing the MUMO protocol for both NOE and RDC restraints (PDB code 2KOX [51]).

With regards to any such experimentally-restrained conformational sampling protocol, the central question is to what degree does the restrained simulation offer a representation that is more consistent with a Boltzmann conformational distribution than that offered by a standard unconstrained molecular simulation. To demonstrate the utility of peptide acidity analysis in providing such an assessment, we carried out a set of three parallel short 30 ns simulations under conditions mimicking the experimental hydrogen exchange measurements starting from the 1UBQ X-ray structure [44] using the CHARMM27 force field [46] in the NAMD2 molecular dynamics package [58] (Cα and heavy atom rmsd as a function of trajectory time — Fig. S1-Supplementary Materials). Following the first 3 ns of the production run, frames were collected every 30 ps and the electrostatic potential at each ionizing amide of the protein was calculated using the DelPhi Poisson–Boltzmann finite difference solver [26]. The exchange reactivity predictions of every frame were averaged to calculate the experimental hydroxide-catalyzed hydrogen exchange rate constant. The analogous calculations were carried out for the 640 conformations in the 2KOX ensemble and the results compared to our [10,50] previously reported calculations on the 2NR2 and 2K39 model ensembles.

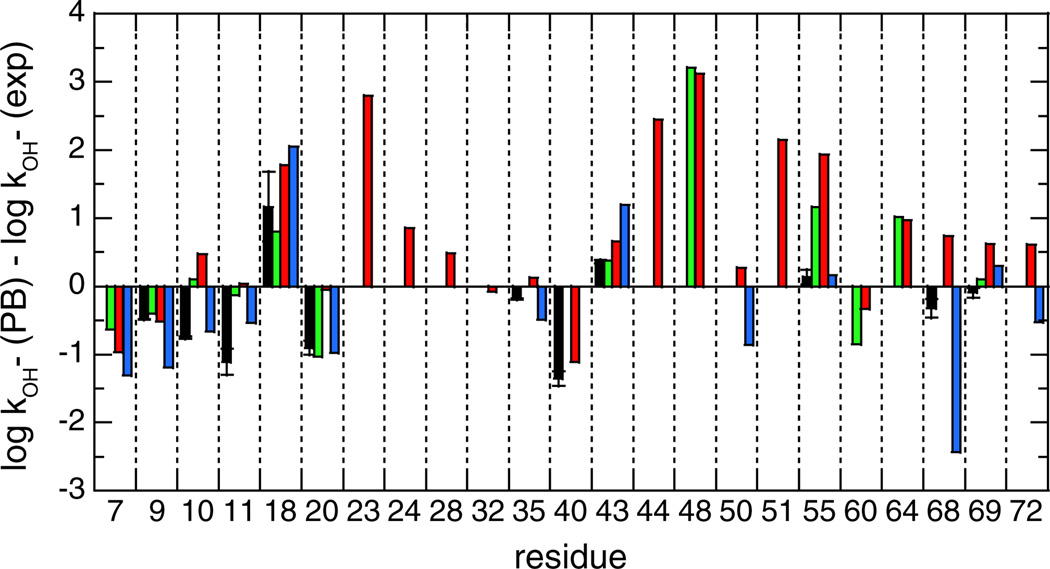

The exchange behavior of the frequently exposed amide hydrogens provide a particularly sensitive monitor of the most probable conformation as standardly assessed by crystallographic or NMR solution structure methods. Excluding the residue adjacent to the N-terminus [6], there are 19 residues for which the amide hydrogen is accessible by at least 0.5 Å2 in over 50% of the trajectory frames of the three unconstrained 30 ns simulations. The continuum dielectric calculations of the electrostatic potential at each solvent-exposed amide were used to predict the exchange reactivity for each of these 19 residues in the three NMR-restrained ensembles as well as for the unconstrained simulations, and the deviations from the experimental hydroxide-catalyzed rate constants kOH− were determined (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Errors in predicting the hydroxide-catalyzed exchange rate constants for the backbone amide hydrogens of ubiquitin that are solvent exposed by >0.5 Å2 in over 50% of the frames in unconstrained MD simulations. Exchange reactivities were predicted from the conformations of the 2NR2 (green), 2K39 (red) or 2KOX (blue) NMR-restrained ensembles as well as an average over conformations from three 30 ns unconstrained MD simulations using the CHARMM27 force field (black). DelPhi [26] was used to carry out Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) predictions of the electrostatic potential at each ionizing amide site. Where large enough to be visible, the error bars indicate the rmsd among predictions from the individual 30 ns simulations.

Readily apparent is the severe underestimation of exchange reactivity of Asp 52 by each of these simulations, strongly indicating that all of these ensembles fail to adequately sample the conformations that give rise to the majority of the observed reactivity. Conversely, the hydrogen exchange rate at Gly 47 is appreciably overestimated from both the restrained and unrestrained simulations. As discussed below, when the more rarely exposed amides are analyzed, a markedly larger overestimate for the adjacent Lys 48 amide is predicted by both the 2NR2 and 2K39 model ensembles.

The rmsd errors in log kOH− values for the other 17 frequently exposed amides in these ensemble-based predictions range from 0.63 for the unconstrained simulations to 0.48 for the 2NR2 ensemble, with an intermediate quality of predictions from the 2K39 and 2KOX ensembles (Table 1). These errors are more than 10-fold above the estimated uncertainty of 0.041 for the experimental ubiquitin log rate constants [10]. Although these rmsd values are appreciably less than those typically reported for analogous continuum dielectric predictions of protein sidechain pK values [20–24], there is an even larger distinction in the statistical significance of these predictions, reflecting the wider range of pK values exhibited by the peptide ionizations. The 105-fold range in peptide acidities for this set of 17 highly exposed amides of ubiquitin results in correlation coefficient r values near 0.93 for each of unconstrained, 2NR2, 2K39 and 2KOX-based calculations (Table 1). This enhanced performance vis-à-vis the analogous sidechain pK predictions clearly demonstrates the practical limitations of ascribing a uniform volume polarizability to model protein conformational reorganizations that occur in the µs–ms time-frame of a protein sidechain ionization.

Table 1.

Ensemble-based log rate predictions for highly (>50% of conformations) and weakly (1% to 50% of conformations) solvent-accessible amides of ubiquitin.

| >50%a | >1%b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rmsd | r | rmsd | r | |

| Unconstrained MD | 0.63 | 0.930 | 0.76 | 0.795 |

| PDB code 2NR2 | 0.48 | 0.948 | 0.71 | 0.808 |

| PDB code 2K39 | 0.56 | 0.935 | 1.20 | 0.729 |

| PDB code 2KOX | 0.58 | 0.918 | 1.16 | 0.656 |

Excluding Gly 47 and Asp 52.

Excluding Lys 48.

For only a few of the residues is the dispersion among the exchange reactivity predictions from the three unconstrained MD ensembles large enough to yield an rmsd that is discernible on the scale illustrated in Fig. 1. In nearly all cases, the precision among the predictions from the repeated unconstrained simulations is substantially greater than their accuracy in predicting the observed exchange rate data.

The NOE and 15N,13C relaxation-restrained 2NR2 ensemble of Vendruscolo and colleagues [48] yield an average error in rate predictions of slightly under a factor of 3, while the ensemble derived from the three unconstrained 30 ns simulations results in an average error of just over a factor of 4. The difference in performance for these two model ensembles is consistent throughout this set of amides. Only for Gln 62 is the error for the 2NR2 prediction both greater than a factor of 3 and larger than that of the unconstrained simulations. The two experimental RDC-derived ensembles provide an intermediate quality of predictions for this set of frequently exposed amides. These results suggest that the application of the 2727 NOE restraints from the solution structure analysis of ubiquitin [56] helps maintain these restrained model ensembles somewhat closer to the most probable conformation in solution than does a standard unconstrained MD run.

3.2. Hydrogen exchange analysis of NMR-restrained model conformational ensembles of ubiquitin for more rarely exposed amides

The situation changes dramatically when the exchange rates of the more rarely exposed amide hydrogens are considered. Here the ability of each simulation to accurately sample the less populated regions of conformational space is more directly tested. In Fig. 2 plotted are the log errors in the hydrogen exchange rate predictions of these ensembles for amides that are well exposed to the aqueous phase in more than 1% but less than 50% of the conformations. This excludes the residues of the 2NR2 (144 models) and 2K39 (116 models) ensembles that are solvent exposed in only a single conformation which we have previously noted gives rise to a systematic biasing in the exchange rate predictions [10]. For the NOE-restrained, RDC-selected 2K39 ensemble of de Groot and colleagues [49], the exchange rates are overestimated by 100- to 1000-fold for five residues. For three of these residues, the other ensembles predict no solvent accessibility at the 1% level. In contrast, the NOE, RDC-restrained 2KOX ensemble of Salvatella and colleagues [51] underestimates the exchange rates by more than 3-fold for 8 of the more rarely exposed amides, while yielding analogous overestimates for only 2 residues.

Fig. 2.

Errors in predicting the hydroxide-catalyzed exchange rate constants for the backbone amide hydrogens of ubiquitin that are solvent exposed by >0.5 Å2 for more than 1% of the conformations in either unconstrained CHARMM27 MD simulations (black) or the 2NR2 (green), 2K39 (red) or 2KOX (blue) NMR-restrained ensembles for residues not analyzed in Fig. 1. DelPhi [26] was used to carry out Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) predictions of the electrostatic potential at each ionizing amide site. Where large enough to be visible, the error bars indicate the rmsd among predictions from the individual 30 ns simulations.

Particularly striking is the case of Lys 48 for which both the 2NR2 and 2K39 ensembles overestimate the experimental exchange rate by more than a factor of 103. In contrast, the 2KOX ensemble and the unconstrained simulations predict no solvent accessibility at the 1% level. In anticipation of a more extensive discussion given below on the impact of different force fields on the ensemble predictions, it should be noted that the 2NR2 ensemble simulation utilized the CHARMM22 force field [25], apparently without inclusion of the previously described CMAP [59] correction of the backbone dihedral angle potentials. The more recent 2KOX ensemble, as well as the unconstrained simulations reported herein, utilized the CHARMM27 force field with the CMAP corrections incorporated. The 2K39 ensemble utilized the OPLS-AA force field [35,60].

Excepting Lys 48, the more rarely exposed amides illustrated in Fig. 2 yield experimental log exchange rate constant predictions from the NOE and 15N,13C relaxation-restrained 2NR2 ensemble with an rmsd of 0.71, similar to that for the unconstrained simulations, with both ensembles yielding r values near 0.80 (Table 1). In marked contrast, the NOE-restrained, RDC-selected 2K39 ensemble and the NOE, RDC-restrained 2KOX ensemble yielded considerably larger rmsd values of 1.20 and 1.16 with r values of 0.729 and 0.656, respectively.

Despite the fact that both the 2K39 and 2KOX ensembles utilized the same set of NOE and RDC experimental restraints and they yielded similar overall statistics for their predictions on both the frequently and more rarely exposed amides, the detailed pattern of their errors is strikingly different (Fig. 3). The 2K39 ensemble predicts a far wider distribution of conformations than do the unconstrained simulations. For 12 of the residues illustrated in Fig. 2, the 2K39 ensemble predicts solvent accessibility when the unconstrained simulations do not, and in nearly every one of those instances the 2K39 ensemble overestimates the experimental value. In no case do the unconstrained simulations predict solvent accessibility above 1% when the 2K39 ensemble does not. As previously discussed [10,50], the 2K39 ensemble exhibits a large divergence of its conformations away from not only the starting NMR solution structure but also away from the full range of available X-ray structures of ubiquitin. Combined with the numerous elevated hydrogen exchange rate predictions illustrated in Fig. 2, this ensemble generally appears to correspond to a drifting away from the proper Boltzmann conformational distribution.

Fig. 3.

Experimental and predicted hydroxide-catalyzed rate constants for the occasionally solvent-exposed backbone amide hydrogens of ubiquitin that are analyzed in differential mode in Fig. 2. Predictions were derived from the unconstrained CHARMM27 MD simulations (A) or the 2NR2 (B), 2K39 (C) or 2KOX (D) NMR-restrained ensembles. The correlations between the predicted and observed exchange for Lys 48 are indicated as open circles.

In contrast, for only 2 residues does the 2KOX ensemble predict solvent accessibility above 1% when the unconstrained simulations do not, while reverse condition applies for only Gln 40. However, despite providing a set of solvent accessible amides that is far more similar to that of the unconstrained simulations, the 2KOX ensemble exhibits a marked tendency to underestimate the experimental exchange rates for the more rarely exposed amides. Only for Gly 10 and Lys 11 in the tight turn T1 does the 2KOX ensemble offers a more accurate prediction than do the unconstrained simulations.

The markedly differing performance of the 2K39 and 2KOX ensembles demonstrates the significant impact arising from applying different methods of filtration vs. restraint using the same set of experimental data. The 2KOX ensemble utilizes a full explicit atom CHARMM27-based molecular dynamics simulation as its conformational sampling technique with the experimental restraints directly integrated into this search via pseudo-energy terms applied over sub-ensemble averages. However, rather than stimulating an enhanced sampling of conformational diversity so as to satisfy the RDC-derived bond vector orientational order parameters, the algorithm applied to the experimental restraints for the 2KOX ensemble appears to have suppressed the degree of conformational sampling, relative to the unconstrained simulations. This conclusion of reduced conformational divergence for the 2KOX ensemble (and enhanced divergence for the 2K39 ensemble) is supported by the rmsd values among the Cα and all heavy atom positions. The unconstrained and NMR-restrained 2NR2 ensembles exhibit highly similar rmsd values of 0.81 Å and 0.80 Å for the Cα atoms and 1.29 Å and 1.33 Å for all heavy atoms (residues 1 to 70), respectively. In contrast, the 2K39 ensemble exhibits substantially larger dispersions of 1.33 Å and 1.98 Å for the Cα and all heavy atom positions, while smaller rmsd values of 0.75 Å and 1.20 Å are obtained for the 2KOX ensemble.

Excepting Lys 48, the performance of the NOE and 13C,15N relaxation-restrained 2NR2 ensemble in predicting the exchange behavior of the more rarely exposed amides is largely indistinguishable from that of the unconstrained simulations, not only in terms of the overall rmsd and correlation coefficient but also in terms of the set of residues with predicted solvent accessibilities and the distribution of errors at those sites. In no case does the sign of the error in predicted rate differ between the 2NR2 and unconstrained ensembles when the magnitude of the errors in the log kOH− value from both ensembles is greater than 0.15. These results suggest that the imposition of 122 relaxation order parameter restraints in a sub-ensemble averaged fashion has not appreciably affected the quality of the Boltzmann distribution prediction over that which is offered by a standard unconstrained simulation.

In contrast to the 2NR2 and 2KOX ensembles which apply the experimentally-derived restraints as perturbations on a full explicit atom CHARMM-based molecular dynamics simulation used to generate the desired conformational sampling, the 2K39 ensemble generates an initial set of ubiquitin conformations using a criterion of compatibility with the experimental NOE constraints by averaging over pairs of structures. The RDC restraints are then used to guide selection of subsets of this initial pool of 500 pairs of structures (allowing for duplications). Since the generation of the initial set of model structures is carried out in a protocol that is not designed to provide a Boltzmann-distributed ensemble, the RDC-guided selection process must serve to impose the desired distribution. As noted above, the number of experimental restraints available is vastly too small to realistically serve this role. The dispersion of the initial pool of CONCOORD-derived [57] ubiquitin structures is quite large, and although imposition of the RDC-selection process does reduce the extent of that dispersion [49], it cannot offer the structural detail needed to enable that reshaping to yield a proper Boltzmann distribution. This study provides further demonstration of the fundamental statistical inadequacy in sample-and-select algorithms that rely upon the experimentally-guided selection process to introduce a proper Boltzmann distribution into an initial sampling of conformational space which lacks that property [50].

3.3. The dependence of bond vector order parameter predictions for ubiquitin as a function of molecular force field

In addition to its utility in testing protocols for experimentally-restrained protein ensemble modeling, ubiquitin has provided a favorite model system for assessment of differing molecular force fields and comparison of molecular simulations with relevant experimental results. Following up on earlier studies which indicated that the original AMBER ff94 force field parameter set tends to overestimate the fraction of α-helicity [61,62], Simmerling and colleagues [63] compared the ability of various AMBER parameter sets to predict the experimental 15N backbone order parameters S2 for ubiquitin. They found that when ff94 force field [64] calculations were used to derive S2 values from averages over 5 ns segments of a 30 ns production trajectory, order parameters near 0.3 were predicted for the tight turn T4 of ubiquitin that immediately precedes Lys 48, the primary site of proteasome-targeted polyubiquitylation (Fig. 4). In marked contrast, the later AMBER ff99 [65], ff99SB [63] and ff03 [37] force fields predicted S2 values for this turn that were near the experimental 15N relaxation values that are above 0.8 [66]. Besides the highly mobile C-terminal tail, the only other segment of ubiquitin predicted to exhibit substantial internal motion on this timescale is around Gly 10 in the first turn T1. Excepting the ff03 force field, the other three AMBER force fields predicted 15N order parameters around 0.5 [63] as compared to the experimental values near 0.7 for this turn.

Fig. 4.

1H–15N bond vector NMR relaxation order parameters experimentally observed (blue on N [66]) and predicted from the AMBER 94 simulations of Simmerling and colleagues (green on Cα [63]), the GROMOS96 43a1 simulations of Nederveen and Bonvin (cyan on C [68]), and the OPLS-AA simulations of Shaw and colleagues (red on O [69]). Order parameters larger than 0.80 are represented by a radius of 0.2, while lower order parameters are represented by a radius of (1 − S2).

In analyzing a considerably longer 0.2 µs simulation of ubiquitin using the GROMOS96 43a1 force field [67], Nederveen and Bonvin [68] noted that the predicted order parameter values for the T1 and T4 tight turns markedly decreased as a function of the increasing length of the trajectory used to predict S2. In particular, the order parameters around the T1 turn dropped to 0.2 over the full 0.2 µs simulation (Fig. 4). In addition, these authors observed a similar trajectory length-dependent decrease in order parameters for the T3 turn that encompasses the Pro 37-Pro 38 dipeptide, with the S2 values dropping to 0.25 during the full 0.2 µs simulation. These authors interpreted their low order parameters for these turn segments as indicating internal motion that is slow on the timescale of the protein rotational diffusion. Molecular tumbling serves to quench the orientational correlations of the 1H–15N bond vectors that provide the experimental sensitivity of NMR relaxation to internal motions that occur more rapidly than the global correlation time (4.09 ns at 27 °C [66]).

Three years later, on the basis of a 1.2 µs molecular simulation using the OPLS-AA force field, Shaw and colleagues [69] drew a similar conclusion regarding segmental backbone fluctuations in ubiquitin that are slow on the timescale of molecular tumbling. Again increased conformational flexibility was predicted for both the T1 and T4 tight turns. However, in contrast to the Nederveen and Bonvin simulation, these authors did not observe markedly decreased order parameters in the T3 turn, but rather they reported increased mobility in the immediately preceding segment, extending back into the last turn of the major α-helix (Fig. 4). The experimental 15N relaxation data [66] indicates that any such conformational flexibility for the residues from the last turn of the helix through the T3 turn must be slow on the global tumbling timescale since the 15N order parameters in the segment between Lys 29 and Gln 41 are all above 0.85, excepting Ile 36 (0.78).

As the conformations giving rise to the reduced order parameters predicted for the residues between Lys 29 and Gln 41 in the GROMOS96 and the OPLS-AA simulations were not reported, a quantitative comparison of the corresponding hydrogen exchange reactivity predictions cannot be made. Nevertheless, several relevant observations can be drawn. The qualitative scale of the local conformational dispersity can be derived by comparison to simple dynamical model analysis of the 1H–15N bond vector. In the GROMOS96 43a1 force field simulation, the order parameter values for the T3 turn drop below 0.25. A two-state jump model of any angle is insufficient to predict such a low S2 value [70]. For the more conservative model of uniform diffusion-in-a-cone, an S2 value of 0.24 implies a 52.5° half angle for the cone of bond vector reorientation. Applying the diffusion-in-a-cone model to the OPLS-AA force field simulation yields a 32° half angle for residues in the last turn of the α-helix.

Over the region of the ubiquitin backbone spanned by these two adjacent sites of proposed enhanced flexibility (Lys 29 to Gln 41) only Asp 39 has its amide hydrogen exposed to solvent in the 1UBQ X-ray structure. Given the magnitude of the angular dispersion of the 1H–15N bond vectors implied by these low predicted order parameters, it would seem unlikely that all of these amide hydrogens would remain inaccessible to solvent throughout the GROMOS96 and OPLS-AA simulations. With the exception of Asp 39, none of the residues in this region has log rate constant kOH− values above 6.0, which is 2.3 units below that of the standard unstructured peptide reference poly-d,l-alanine [30]. Invoking the commonly used peptide normalization assumption, these “protection factors” would imply that all of these amide hydrogens must remain inaccessible to solvent in greater than 99% of all conformations [4]. Proper consideration of the electrostatic interactions of hydrogen exchange reactivity negates this categorical conclusion. Nevertheless, this combination of predicted extensive conformational flexibility and significantly attenuated experimental hydrogen exchange reactivity over a substantial segment of the backbone would seem exceptional.

3.4. Peptide acidity analysis of flexibility in the T4 tight turn of ubiquitin

The unconstrained MD simulations using the GROMOS96 43a1 and OPLS-AA force fields, as well as the AMBER ff94 simulation of Simmerling and colleagues (and the analogous AMBER ff94 ubiquitin simulation of Garcia and colleagues [71]), all predict extensive flexibility in the T4 turn preceding Lys 48. Structural insight into this predicted flexibility is provided by the NMR-restrained 2NR2 and 2K39 ensembles that overestimate the hydrogen exchange rate of Lys 48 by more than 103-fold (Fig. 2). In both of these model ensembles, the T4 turn exhibits substantial conformational heterogeneity. Gly 47 has a positive mainchain ϕ value of + 61.7 in the 1UBQ X-ray structure [44]. Among the 144 ubiquitin model conformations in the 2NR2 ensemble, 83 models have ϕ values for Gly 47 that differ from the crystallographic value by more than 90° (Fig. S2-Supplementary Materials). These conformations have similar shifts in the mainchain ψ angle of Ala 46, corresponding to a flipping of the peptide unit linking the two residues. Similarly, 18 of the 116 conformations in the 2K39 ensemble differ by as much from the X-ray structure at these adjacent dihedral angles. In contrast, none of the 640 conformations of the NMR-restrained 2KOX ensemble and only 1 of nearly 3000 trajectory frames from the three parallel unconstrained 20 ns simulations exhibits a similar flip of the peptide group linking Ala 46 and Gly 47. As noted above, the reduced flexibility of Gly 47 in the latter two ensembles likely reflects the use of the CMAP torsion angle potential corrections to the CHARMM27 force field.

To examine the degree to which the overestimation of Lys 48 exchange reactivity from the 2NR2 and 2K39-based calculations might reflect the predicted conformational transitions of the Ala 46 ψ and Gly 47 ϕ dihedral angles, the reactivity of that amide was recalculated from the 2NR2 and 2K39 ensembles using only the conformations that have Ala 46 ψ and Gly 47 ϕ dihedral angles within 90° of the crystallographic value. For the 2NR2 ensemble, the predicted log rate constant for Lys 48 exchange is 4.56 as compared to the experimental value of 4.93 for log kOH−. Similarly, when the conformations in the 2K39 ensemble having Ala 46 ψ and G47 ϕ values more than 90° from the X-ray structure are removed, the predicted rate constant decreased nearly 100-fold to a log kOH− value of 6.23.

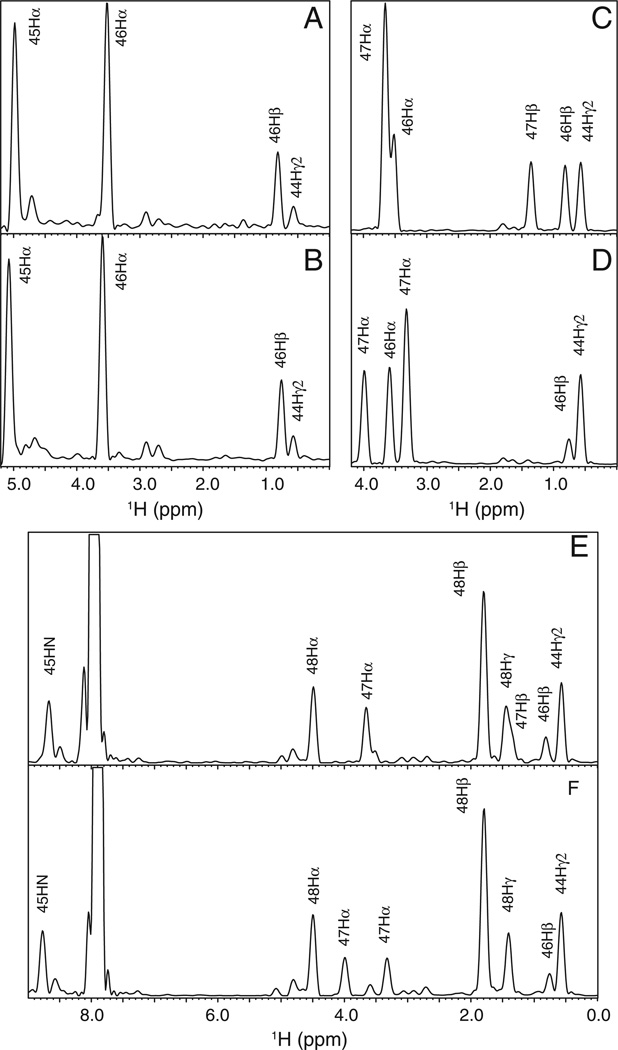

To experimentally test whether transitions of the Gly 47 ϕ dihedral angle might be sufficient to explain the overestimation of the exchange reactivity for Lys 48, the G47A mutational variant was generated with the expectation that introduction of the Cβ methyl group would bias the conformation of that residue toward a negative ϕ value. Surprisingly, when the 1H–15N 2D correlation spectrum was obtained on this sample, its spectrum was strikingly similar to that of the wild type protein (Fig. 5). Although, as expected, substitution of alanine gives rise to a substantial change in the 15N chemical shift of residue 47, the other changes in chemical shifts are limited to the immediately adjacent residues and are quite modest.

Fig. 5.

2D 1H–15N heteronuclear correlation spectra of G47A ubiquitin (panel A) and the wild type protein (panel B).

1H–15N correlation spectra are commonly denoted as the “fingerprint” region, reflecting their acute sensitivity to changes in tertiary structure. The lack of substantial variation in the chemical shift patterns of the G47A and wild type ubiquitins strongly suggests that the conformation in the T4 turn and elsewhere is closely preserved upon mutation. As is typical of highly solvent-exposed tight turn conformations, the NOESY crosspeaks for the amide protons of Ala 46 and Gly/Ala 47 are almost exclusively sequential or intraresidue connectivities (Fig. 6). However, both of these amides form NOE interactions with the γ2 methyl of Ile 44 which exhibit highly similar peak intensities and chemical shifts for both the wild type and G47A variant. In both of the wild type and G47A ubiquitins, the amide proton of Lys 48 form longer range interactions with this same Ile 44 methyl as well as to the amide of Phe 45 and the methyl of Ala 46. Taking into account the effects of the methyl substitution in changing from Gly to Ala at residue 47, the patterns of the Lys 48 amide crosspeaks are strikingly similar for the wild type and G47A ubiquitins.

Fig. 6.

1D slices from the 2D 1H–1H NOESY spectra of G47A (upper) and wild type (lower) ubiquitin protein at the amide 1H frequencies of Ala 46 (panels A and B), Ala/Gly 47 (panels C and D), and Lys 48 (panels E and F) in the T4 turn.

To more directly demonstrate that these data are inconsistent with a flipping of the ϕ dihedral angle at residue 47 in the G47A variant, the backbone conformations of the 2NR2 ensemble having negative ϕ values at this residue (Fig. S2-Supplementary Materials) were compared to the distribution of alanine conformations reported in high resolution X-ray structures. The highly exposed position of residue 47 insures that any such alanyl residue would direct its Cβ methyl out into the solvent phase without forming any nonsequential intramolecular contacts. The backbone conformations of the 2NR2 ensemble having negative ϕ values at Gly 47 predict distances from the amide protons of the T4 turn to the Cγ2 of Ile 44 and the amide of Phe 45 that are inconsistent with the observed NOE patterns of the G47A variant (Table S1-Supplementary Materials).

We conclude that the tertiary structure of ubiquitin stabilizes the conformation of residue 47 in the G47A variant in a locally unfavorable energetic state. Hydrogen exchange analysis potentially offers insight into how this mutation modulates the conformational transitions that give rise to exchange. The hydroxide-catalyzed exchange rate constants for every backbone amide were determined for both the wild type and G47A variant using a combination of magnetization transfer-based CLEANEX-PM [7,9] measurements for the faster exchanging sites and 1H isotope exchange-in experiments for characterizing the slower exchanging amides as previously described [10]. At 25 °C, the most slowly exchanging amides of ubiquitin enter the EX1 kinetic regime only above pH 9.5 [72], over 2 pH units more basic than the isotope exchange measurements of this study. The sole exception to a complete backbone analysis is the conformational exchange-broadened Gly 53 amide for which the resonance in the wild type spectrum at pH 8.72 was sufficient for deriving a rate estimate, while the crosspeak in the analogous spectrum for the G47A variant was too attenuated.

As is apparent from the data of Fig. 7, for the majority of residues the amide exchange rate constants are virtually unaffected by the mutation of glycine to alanine at residue 47. Excluding the residues near the T4 turn as well as several residues on either side of the T6 turn, the 43 other residues with log kOH− values above 3.5 differ between G47A and the wild type protein with an rmsd of 0.045, consistent with our previous estimates of experimental uncertainty in these measurements (0.041 [6]). Slightly elevated exchange rates were observed for residues 59–61 where the aromatic ring of Phe 45 packs against the backbone and near the amide of His 68 that is hydrogen bonded to the carbonyl oxygen of Ile 44.

Fig. 7.

The log rate constants at 25 °C for hydroxide-catalyzed amide exchange in the wild type (+) and the G47A variant (x) of ubiquitin. Residues exhibiting exchange rates consistent with exchange via a global unfolding transition in the G47A variant are highlighted by the dashed ellipse.

3.5. Structural interpretation of the change in the global stability of ubiquitin induced by the G47A mutation

The log exchange rate of Lys 48 increased by 0.97 in the G47A variant as compared to the wild type protein. Similarly, the six slowest exchanging amides, with log kOH− values near 1.2 in wild type ubiquitin, increase their log exchange rates by an average of 1.12. This decrease in the maximal protection factors is consistent with the G47A variant being destabilized by 1.5 kcal/mol, relative to the wild type protein. Three other residues Val 17, Val 26 and Ile 44 also increase their log kOH− values to 2.3 suggesting that the destabilization of the G47A variant results in a larger set of amides that have global unfolding as their most efficient pathway for hydrogen exchange.

To provide independent verification of the conformational destabilization induced by the G47A mutation, guanidinium chloride denaturation measurements on the two proteins were monitored by circular dichroism. Given the widely noted extreme stability of ubiquitin to guanidinium chloride denaturation at neutral pH, we have followed the denaturation conditions at pH 4 described by Sanchez-Ruiz and colleagues [73]. As previously noted by those authors, we observed for the wild type protein an increasingly negative ellipticity at low denaturant concentrations preceding the unfolding transition (Fig. 8). A midpoint was observed at 3.9 M guanidinium chloride with an m-value of 2.2 kcal/mol (Figs. S3 and S4-Supplementary Materials), similar to the values previously reported for these conditions [73]. The unfolding transition of the G47A variant is centered at 3.1 M guanidinium chloride with an m-value of 2.0 kcal/mol (Figs. S2 and S3-Supplementary Materials). Using the difference in free energy of unfolding given by [74]:

the G47A variant was found to be 1.7 kcal/mol less stable than the wild type protein, similar to what was inferred from the changes in the hydrogen exchange rate constants.

Fig. 8.

The molar ellipticity of the wild type (panel A) and the G47A variant (panel B) of ubiquitin as a function of guanidine hydrochloride at 25 °C in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 4.0.

These data are consistent with the interpretation that the tertiary structure of ubiquitin strongly favors a positive ϕ angle at residue 47, while at the same time the kinetically efficient pathway to hydrogen exchange at Lys 48 occurs via a flip of the preceding peptide unit. Furthermore, mutating residue 47 to alanine increases the fractional population of the flipped Ala 46-Gly 47 peptide linkage conformations which, in turn, yields an equivalent decrease in the global stability of the protein. The 2NR2 and 2K39 ubiquitin ensembles predict approximately equal populations of the positive and negative ϕ angles for Gly 47 which results in an overestimation of the exchange rate constant for Lys 48 by a factor of 103. This indicates that negative ϕ conformations for Gly 47 are populated at ~0.1% in the wild type protein, far too rare to give rise to the low order parameters predicted in the molecular dynamics studies considered above.

3.6. Peptide acidity analysis of conformational basins predicted for bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI)

A large number of experimental and molecular simulation studies have also been applied to bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI) to ascertain a detailed understanding of its conformational dynamics. The NMR chemical exchange analysis of the aromatic ring flips in BPTI by Wüthrich and colleagues [75] provided a seminal demonstration of protein conformational dynamics occurring in the millisecond timeframe. Subsequently, his laboratory also characterized a larger scale conformational transition on the millisecond timescale centered around a reversal of chirality in the disulfide bond linking Cys 14 and Cys 38 for which the minor conformation is populated at approximately 2.5% at 25 °C [76,77]. Subsequent NMR studies have reported chemical exchange broadening effects in a large number of proteins that are indicative of conformational transitions occurring in the µs–ms timeframe [78].

Until recently, such slow processes were beyond the practical range of unconstrained molecular dynamics simulations. Shaw and colleagues [40] have published a 1 ms full explicit atom simulation of BPTI at 300 K using a modified version of the AMBER99SB force field. They predicted that BPTI significantly occupies five distinct conformational basins between which transitions occur in the timeframe of 10 µs. These basins are characterized by regions of distinct backbone conformations. The authors note that, apart from low-amplitude high frequency motion, bond orientations within the backbone exhibit little variation for a given basin. Conformational transitions within each basin primarily reflecting sidechain motions which occur over timeframes up to 10 ns.

The two most populated basins are similar in conformation to the X-ray structure (basin 1) and the disulfide chirality-reversed conformation characterized by Wüthrich and colleagues (basin 0). However, in contrast to the experimentally observed ratio of 40 to 1, Shaw and colleagues predict a ratio of 0.49 (27%/55%) for these two basins corresponding to a free energy discrepancy of 2.6 kcal/mol in the relative stability of the disulfide chirality-reversed conformation (basin 0) as compared to the crystallographic-like basin 1. In order of decreasing population, basins 2, 3 and 4 are predicted to occur at approximately 13%, 3% and 3%, respectively. With regards to sampling statistics, there are 30 transitions into and out of basin 2 during the 1.03 ms simulation, as compared to only 22 transitions for the crystallographic-like basin 1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Experimental and predicted populations of BPTI conformational basins.

For each of the five conformational basins, Shaw and colleagues identified a small set of residues that they proposed to most strongly discriminate among the relative stabilities of each basin. Of particular note is Gly 37, adjacent to the site of disulfide chirality reversal, which is reported to provide critical differential stabilization of basin 2. This glycine residue adopts a positive ϕ backbone torsion angle in the various X-ray structures of BPTI. To probe the energetics of this conformation, Woodward and colleagues [79] had several years earlier carried out hydrogen exchange measurements on the wild type and the highly destabilized G37A variant. Their study provides the most complete set of hydrogen exchange data currently available for BPTI with the exchange rates for 41 backbone amides reported at pH 4.6 and 10 °C, although it may be noted that the rates for 22 of these residues were extrapolated from other temperature and pH conditions assuming activation energies of either 30 or 35 kcal/mol.

To provide a basis for predicting the amide exchange behavior of BPTI, the high resolution X-ray structure (PDB code 5PTI [47]) was used to initiate a 50 ns unconstrained MD simulation using the CHARMM27 force field in the NAMD2 simulation package. Although 18 residues have amide hydrogens that are exposed to solvent by more than 0.5 Å2 in over half of the trajectory frames, the Woodward study reports exchange rates for only 9 of these, reflecting the absence of experimental data for the most rapidly exchanging sites. Continuum dielectric predictions of the electrostatic potential at each of these amides were carried out for trajectory frames spanning the last 45 ns of the production run sampled at 50 ps intervals. For the purpose of relating the predicted rate constants (in M−1 s−1 at 25 °C) to the experimental exchange rates (in min−1 at pH 4.6 and 10 °C), we applied the assumptions that the observed exchange was hydroxide-catalyzed and that the exchange at each site exhibited an activation energy of 30 kcal/mol.

For the complete data set for ubiquitin described above, the predicted differential log rate constants ΔkOH− are shifted onto an absolute scale based on a unit slope linear best fit for observed log rate constants of the well-exposed amides. However, only half of the well-exposed amides of BPTI have reported exchange rates. To minimize the number of independently adjustable parameters for this limited data set, the acidity of the internal reference N-methylacetamide molecule predicted from the ubiquitin electrostatics calculation was applied to the BPTI analysis. Despite the extrapolations used to compensate for differing experimental conditions of the various BPTI exchange measurements, the reactivities of the well-exposed backbone amides of BPTI are quite effectively predicted (Fig. 9). With an rmsd of 0.55 and a correlation coefficient of 0.836, the quality of the log kOH− predictions for these 9 residues compares reasonably well with those for the considerably more accurate ubiquitin exchange rate constant measurements. This performance provides further evidence that the practical experimental accuracy of hydrogen exchange measurements is substantially superior to the present ability to model protein conformational distributions and derive electrostatic potential predictions from these conformations.

Fig. 9.

Hydroxide-catalyzed rate constants at 25 °C predicted by Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) continuum dielectric methods for the 9 backbone amides of BPTI that are solvent exposed by >0.5 Å2 in over 50% of the frames in an unconstrained 50 ns MD simulation for which experimental exchange rates have been reported [79]. Under the assumptions of hydroxide catalysis and 30 kcal/mol activation energies, the reported rates (min−1) at pH 4.6 and 10 °C were converted to rate constants (M−1 s−1) via multiplication by 109.10.

Analogous 50 ns MD simulations and electrostatic potential predictions were carried out for each of the five published reference structures for the BPTI conformational basins [40]. Only two of the set of residues identified by Shaw and colleagues as being most structurally discriminative for conformational basin 2 (Cys 14 and Gly 37) have amide hydrogens that are well-exposed throughout the simulation and for which experimental exchange data was reported [79]. The amide hydrogen of Gly 37 is exposed to solvent by more than 0.5 Å2 in all 900 frames examined in the 50 ns basin 2 trajectory. In marked contrast, this amide hydrogen is solvent-inaccessible in every frame of the MD simulations initiated from the 5PTI X-ray structure or from either the basin 0 or basin 1 reference structures. The continual solvent exposure for the Gly 37 amide throughout the basin 2 simulation correlates with the maintenance of a positive backbone ϕ value of the preceding Gly 36 residue. The X-ray structure and the four other reference basin conformations all exhibit negative ϕ values for Gly 36 and maintain that state throughout their 50 ns MD simulations. The local backbone conformation in the basin 2 reference structure results in an electrostatic environment for the Gly 37 amide that predicts an exchange rate near the diffusion limit, and the predicted reactivity of this residue remains near the diffusion limit throughout the 50 ns MD simulation (log kOH− of 10.2). As this is the site of primary focus in the earlier BPTI hydrogen exchange study of Woodward and colleagues [79], it is noteworthy that the exchange rate for Gly 37 was reported as 3 × 10−6 min−1 at pH 4.6 and 10 °C which scales to a log kOH− value of 3.6 at 25 °C. Hence, the exchange rate for this residue predicted from the BPTI simulation is more than a million-fold above the experimentally observed value so that a population for conformational basin 2 that is greater than 10−6 appears inconsistent with proper Boltzmann weighting (Table 2).

Lys 41 is the only residue that Shaw and colleagues identified to be most discriminative for the differential stabilization of basin 3 for which experimental exchange data was reported for an amide hydrogen that is well-exposed in over half of the 50 ns MD simulation of basin 3. The predicted log kOH− value of 8.3 markedly exceeds the experimental log rate constant 4.9, indicating that conformational basin 3 is unlikely to be populated at a level above 10−3, well below the 3% representation predicted by Shaw and colleagues. In fact, conformational basin 3 is almost surely far more rare than that. The Gly 36 amide hydrogen is exposed to solvent in less than 1% of the frames for the MD simulations initiated from either the 5PTI X-ray structure or the basins 0 and 1 reference structures. In contrast, the Gly 36 amide hydrogen is well-exposed to solvent in every sampled frame of the 50 ns MD simulation of basin 3. The predicted log kOH− value of 9.2 markedly exceeds the experimental value of 4.1, indicating that the most probable upper limit for the population of basin 3 is 10−5 (Table 2).

As neither of the two residues identified by Shaw and colleagues as most discriminative for the differential stability of basin 4 have an amide proton (Arg 1 and Pro 2), the published set of hydrogen exchange data [79] is of considerably less use in assessing the population of this proposed conformational basin which primarily involves an unwinding at the N-terminus of BPTI.

4. Conclusion

Quantitative structure-based interpretation of amide hydrogen exchange offers a powerful experimental method for assessing the degree to which a model ensemble of protein conformations is consistent with a corresponding sampling of the proper Boltzmann distribution. In analyzing a recent 1 ms molecular dynamics simulation of BPTI, the thermodynamic stabilities for the two most populated novel conformational basins are shown to be overestimated by at least 6.9 kcal/mol (basin 2) and 4.7 kcal/mol (basin 3), respectively. Structural insight is provided into the basis of divergent predictions of conformational flexibility in ubiquitin that have been reported using different molecular force fields. Hydrogen exchange data indicate that the conformational transition in the tight turn preceding the major site of proteasome-directed polyubiquitylation (Lys 48) is far more rare than previously predicted. This transition is efficiently coupled to the global stability of the protein, while most of the other exchange-efficient conformational transitions in ubiquitin appear to be largely unaffected by the backbone transition in this tight turn.

Ubiquitin offers the premier system for the currently most sophisticated efforts to apply experimental restraints to the ensemble modeling of the protein native state. The three published modeling studies considered here all utilized the extensive experimental NOE restraints reported for this protein. In each case, these model ensembles characterize the most probable region of conformational space in solution somewhat more accurately than do the predictions derived from a standard unconstrained molecular dynamics simulation. However, when the more rarely sampled conformations monitored by hydrogen exchange are considered, one experimentally restrained MD simulation (2NR2) provides no discernible improvement on the unconstrained simulation, while the other two (2K39 and 2KOX) perform substantially more poorly than the reference simulation. It must be emphasized that these studies represent the state-of-the-art in the field of experimentally-restrained conformational ensemble prediction. The vast majority of the model ensembles that have been proposed to represent the conformational distribution of various proteins have utilized far less physically realistic approaches to generating the protein conformations and ensuring their consistency with a Boltzmann distribution. Combined with the statistical insufficiency that is inherent in the ensemble modeling problem, physically meaningful advances in this field will demand the systematic setting aside of a substantial fraction of the structurally discriminating experimental data with which to independently test the final model distribution as has long been the standard practice in protein crystallography.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

-

►

Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) predictions of amide exchange test the consistency of conformational ensembles.

-

►

Hydroxide-catalyzed amide exchange rate constants were determined for ubiquitin and its G47A variant.

-

►

Flipping of the Ala 46 / Gly 47 peptide linkage is 10−3–fold rarer than various MD simulation predictions.

-

►

MD simulations match or exceed published NMR-restrained ensembles in predicting the exchange rates for rarely exposed amides.

-

►

The major novel conformational basin predicted in a 1 ms simulation of BPTI is 105-fold overestimated.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the use of the NMR facility, the Biochemistry core and the Molecular Genetics core at the Wadsworth Center. We thank Leslie Eisele for her technical assistance. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant GM 088214.

Abbreviations

- BPTI

bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor

- PDB

protein data bank

- RDC

residual dipolar coupling

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser enhancement

- MD

molecular dynamics

- PB

Poisson–Boltzmann

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.bpc.2012.02.002.

References

- 1.Shen Y, Lange O, Delaglio F, Rossi P, Aramini JM, Liu GH, Eletsky A, Wu YB, Singarapu KK, Lemak A, Ignatchenko A, Arrowsmith CH, Szyperski T, Montelione GT, Baker D, Bax A. Consistent blind protein structure generation from NMR chemical shift data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:4685–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800256105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brünger AT. Free R-value—a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hvidt A, Nielsen SO. Hydrogen exchange in proteins. Advances in Protein Chemistry. 1966;21:287–386. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai YW, Milne JS, Mayne L, Englander SW. Protein stability parameters measured by hydrogen exchange. Proteins: Structure, Function and Genetics. 1994;20:4–14. doi: 10.1002/prot.340200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JS, Hernández G, LeMaster DM. A billion-fold range in acidity for the solvent-exposed amides of Pyrococcus furiosus rubredoxin. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6178–6188. doi: 10.1021/bi800284y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]