Abstract

Phase variation of surface structures occurs in diverse bacterial species due to stochastic, high frequency, reversible mutations. Multiple genes of Campylobacter jejuni are subject to phase variable gene expression due to mutations in polyC/G tracts. A modal length of nine repeats was detected for polyC/G tracts within C. jejuni genomes. Switching rates for these tracts were measured using chromosomally-located reporter constructs and high rates were observed for cj1139 (G8) and cj0031 (G9). Alteration of the cj1139 tract from G8 to G11 increased mutability 10-fold and changed the mutational pattern from predominantly insertions to mainly deletions. Using a multiplex PCR, major changes were detected in ‘on/off’ status for some phase variable genes during passage of C. jejuni in chickens. Utilization of observed switching rates in a stochastic, theoretical model of phase variation demonstrated links between mutability and genetic diversity but could not replicate observed population diversity. We propose that modal repeat numbers have evolved in C. jejuni genomes due to molecular drivers associated with the mutational patterns of these polyC/G repeats, rather than by selection for particular switching rates, and that factors other than mutational drift are responsible for generating genetic diversity during host colonization by this bacterial pathogen.

INTRODUCTION

Simple sequence repeats (SSR) in bacterial genomes provide a mechanism for stochastic variation in expression of specific genes and rapid adaptation to environmental fluctuations. This population-based adaptive process is termed phase variation (PV) and is widespread among bacterial pathogens and commensals (1–4). The phase variable genes drive changes in the expression or structure of surface molecules and hence can influence host adaptation and virulence.

SSR can mediate PV due to their high mutation rates and reversible mutations. Tetranucleotide repeats mediate PV in Haemophilus influenzae and tracts of 17 or more repeat units are known to mutate at high rates (>10−4 mutations/division) with an excess of deletions over insertions (5). Many genes of Neisseria meningitidis and Campylobacter jejuni are subject to PV mediated by polyG/polyC repeat tracts (6,7). The meningococcal mononucleotide repeats generate PV frequencies of between 10−4 and 10−5 with mutability being influenced by tract length and mismatch repair (MMR) (8–10). The mutational patterns of these repeats have not been clearly determined although many switches are constrained as the repeats are present in promoter elements. The mutability of the C. jejuni repeats is known to be high but there are no accurate measurements of the mutation rates or mutational patterns (11–13). Modelling of PV in H. influenzae indicates that mutation rate and mutational patterns are critical determinants of population diversity and hence of adaptation to environmental fluctuations [(5); Palmer et al., in preparation]. Characterization of these facets is, therefore, crucial for understanding adaptation by and evolution of SSR-mediated PV.

Campylobacter jejuni is a Gram negative, spiral-shaped bacterium which occurs as a commensal in the gastrointestinal tract of many species particularly birds (14,15). Campylobacter jejuni causes a severe gastroenteritis in humans and can also trigger autoimmune responses due to molecular mimicry between the lipooligosaccharide (LOS) and host gangliosides (11,16,17). Contaminated chicken meat is a key source of C. jejuni infection for humans and is responsible for a large proportion of the cases of gastroenteritis caused by this bacterial species. Multiple genes of C. jejuni are subject to PV due to polyG/C tracts located within the reading frame and some of these genes are known to contribute to the disease process or to colonization of chickens. For example, cj1139 encodes a glucosyltransferase and mediates PV of LOS epitopes responsible for autoimmunity (11). Another gene, maf4, mediates changes in the glycosylation of the flagella causing alterations in autoagglutination phenotypes, a potential facilitator of host adaptation (18). The phase variable capA gene is required for colonization of chickens but it is unclear if PV of this gene influences this phenotype (19). Variation in the chicken colonization potential of isogenic strains has been noted suggesting a role for PV in this process (20). While selection for motility during colonization of chickens is known to select for changes in short polyA tracts in flgR (21), there is less known about PV due to polyG/C tracts. Changes in the phase variable genes have been observed as C. jejuni adapts to replication in mice (22) and for the G8 tract of cj1139 in broiler chickens (23). There has not however been a comprehensive examination of the changes occurring in multiple phase variable genes during colonization of chickens but there has been speculation that high PV rates in this species may rapidly drive populations to a stable, steady-state combination of ON/OFF states for each gene (13).

In order to understand the contributions of PV to host adaptation by C. jejuni, we determined the mutation rates/mutational patterns of the phase variable loci of C. jejuni using reporter constructs and examined changes in proportions of phase variants during growth of C. jejuni populations subject to differing selective environments. We then utilized the experimentally-derived measurements of PV rates in a stochastic, mathematical model to examine whether high switching rates were solely responsible for driving fluctuations in proportions of phase variants during passage of C. jejuni populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions

A non-motile variant of C. jejuni strain NCTC11168 was obtained from NCTC (6) and grown on Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plates supplemented with vancomycin (10 µg/ml) and trimethoprim (5 µg/ml) in a VA500 Variable Atmosphere Incubator (Don Whitley, UK) using microaerophilic conditions (4% oxygen, 10% carbon dioxide, 86% nitrogen) and at either 37°C or 42°C. A previously isolated hypermotile variant (NCTC11168H; (24)) of this strain was used for inoculation of chickens. A chicken-adapted variant of strain 81–176 was also utilized for inoculation of chickens. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was grown on Luria agar plates supplemented with antibiotics as required: ampicillin 50 µg/ml, kanamycin 50 µg/ml, chloramphenicol 10 µg/ml.

Construction of reporters

A reporter construct for cj1139 was constructed by amplifying either end of this gene with two pairs of primers—5′ GGAATTCCATATTTTACATCTTTACCCAC/5′ CGGTACCAGTATTTGCATTGTAAATTC and 5′ GGT ACCCGGGATCCAAAAATATCAATTCAAATGG/5′ CCTGCAGAGAAGGTAATAATCCTTATG. The upstream primers were designed to fuse a full-length lacZ gene (3.5 kb) to the cj1139 gene at a location 96-bp downstream of the polyG repeat tract resulting in a switching mechanism identical to that of the native gene. The lacZ gene was obtained as a KpnI and BamHI fragment from pGZ-17R (5). A chloramphenicol cassette from pAV35 (25) was inserted into the BamHI site. A similar cj0031 reporter construct was constructed using primers—5′ AACTGCAGAAATTCTCATCACGGGTAG/5′ CGGGATCCGCGGTACCGTGTATTTGTTAGAAGTG and 5′ CGGGATCCAAGATAGAACGCATAGG/5′AGCACCTTGTCCTAAGTGAG. In this case the lacZ gene was located 13-bp downstream of the repeat tract. The G8 tract in the cj1139-lacZ construct was altered to G11 by site-directed mutagenesis using two primers—5′TGGGTGGGGGGGGGGGTAAAATTGATTTGTTGTG and 5′TTTACCCCCCCCCCCACCCATATCCAAAATTTTAA. Constructs were inserted into the chromosome of C. jejuni strain NCTC11168 by electroporation and selection for chloramphenicol resistance as previously described (26). Transformants were tested for insertion of the fusion constructs by PCR using a lacZB1, a primer located at the 5′-end of the lacZ gene (5), and cj1139up (5′GACCTAAAAAAGCATCACTAA), which is located upstream of the cloned fragment of cj1139.

PV assays

Campylobacter jejuni reporter constructs were grown on MHA plates for three days. Serial dilutions of single colonies were prepared in Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) and plated onto MHA plates supplemented with a 1:1000 dilution of a 10 mg/ml X-Gal and IPTG solution (Melford). These plates were incubated for 3–4 days and the total numbers of colonies and numbers of blue and white colonies were counted. These numbers were utilized for calculation of PV frequencies and for derivation of PV rates as described previously (5).

Boiled lysates of initial colonies and phase variants were prepared in 100 µl of distilled water. Repeat tracts were amplified (see below for reaction conditions) with either cj1139for and lacZB1 or cj0031for and lacZB1. These products were then subject to DNA sequencing. PCR products were also subject to a GeneScan analysis, see below, using FAM labelled versions of primers cj1139for or cj0031for and lacZB1.

PV rates for the capA gene were detected by colony immunoblotting (27). Briefly, C. jejuni colonies were transferred to nitrocellulose filters. After blocking for 1 hour with phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), excess colony material was removed and filters were blocked for an additional 30 min. Filters were probed for 2 h with a 1:2000 dilution of an anti-CapA rabbit antiserum (19), washed three times with PBST, probed for 1 h with 1:2000 dilution of a goat anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase conjugate, washed again and developed with a commercial NBT/BCIP solution (PerkinElmer).

Analysis of PV genotypes for C. jejuni

Oligonucleotides were designed for amplification of the repeat tracts of six phase variable genes of strains NCTC11168 and 81–176 (Supplementary Table SI). One primer of each pair was labelled with a fluorescent dye (FAM or VIC) and each amplification product had a unique size of between 100 and 500 bp. Boiled lysates of colonies were prepared and the repeat tracts were amplified using either a combination of either three or six pairs of primers. Each amplification contained 1 µl of lysate, 1 µl of 10 × PCR buffer (from Kapa Biosystems and containing 15 mM MgCl2), 1.8 µl of 25 mM MgCl2, 1 µl of 10 mM dNTPs, 1 µl of a primer mix (i.e. containing each primer at 2 µM), 0.1 µl TAQ DNA polymerase (5 units) and 4.1 µl of distilled water. PCR reactions were subjected to 25 cycles consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 50°C and 1 min at 72°C. After amplification, reactions were subjected to A-tailing. Thus a 4 µl reaction mix (0.4 µl of 10 × PCR buffer, 0.4 µl 25 mM MgCl2, 0.05 µl of 5 U/µl TAQ DNA polymerase, 3.15 µl of distilled water) was added to each reaction and then the reactions were incubated for 45 min at 72°C. These PCR products were analysed using a GeneScan assay (5). Briefly, PCR reactions were diluted 1:5 or 1:10 in distilled water and 0.5 µl of diluted PCR reaction was mixed with 9.25 µl of deionised formamide and 0.25 µl of GSLIZ500 (a size standard from Applied Biosystems). These preparations were subjected to electrophoresis on an ABI3700 and the resultant files were analysed with PeakScanner (Applied Biosystems). The size in base pairs of the highest peak was designated as representative of the sample unless the relative area of this and flanking peaks was <1.2-fold (in most case there was a difference of ≥5-fold). Samples with ratios of <1.2-fold were designated as undetermined and not utilized for genotype analysis unless both tracts lengths had the same phenotype (i.e. both OFF). These samples may represent mixed colonies or replication slippage during PCR amplification.

A sub-set of samples was subjected to DNA sequencing in order to correlate the sizes of the PCR fragments with particular tract lengths. Tract lengths were then converted into an ‘ON’ or ‘OFF’ phenotype based on an analysis of the reading frames for each gene contained in the strain NCTC11168 genome sequence. This expression data was then converted into a binary format using a ‘1’ for an ON phenotype and a ‘0’ for an OFF phenotype. A six-digit binary code was then derived for each colony based on the expression status of the six genes analysed.

Chicken colonization experiments

Two-week-old out bred commercial broiler chickens (PD Hook, UK) were given a 0.1 ml dose of Campylobacter-free gut flora prepared as previously described on the day of hatching (24). Campylobacter strains were grown overnight on sheep blood agar (Oxoid). A sweep from these plates was used to inoculate an MHB culture and grown for 24 h at 37°C. An inoculum was prepared from this culture and inoculated into 2-week-old chickens via the oral route. Dilutions of the inoculum were plated onto Campylobacter selective blood-free agar plates (Oxoid) and incubated for 3 days. Colony counts, immunoblots and boiled lysates of 30–60 colonies were prepared from these plates. The remaining cells in the inoculum culture were concentrated by centrifugation and utilized for preparation of a DNA lysate. Chickens were culled at 1 and/or 14 days post inoculation and caecal material was collected from both caeca. Caecal material was resuspended in PBS and subjected to vigorous mixing using a vortex prior to plating of dilutions on Campylobacter selective blood-free agar plates (24). After incubation, the colonies were subjected to an identical analysis as for the inoculum. For the experiment with strain NCTC11168H, DNA was extracted from the caecal material using a QiaAmp Stool kit (Qiagen). For strain 81–176, the inoculum contained large and small colonies that exhibited identical genotypes for the phase variable genes.

Stochastic model

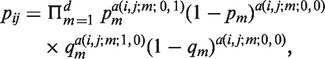

The model was derived assuming a sufficiently large bacterial population with time measured in generations. The model also assumes that switching of each gene is independent of all the other genes. Each bacterium has d genes that can be in an OFF or ON state coded as 0 and 1, respectively, such that each bacterium is represented by the random vector ξ = (ξ1, ξ2, … , ξd), where ξi can take only two values 0 or 1. The random vector ξ has 2d possible values from Ω = {Ai = (a1, a2, … , ad) with aj=0,1}, where we label each element Ai of Ω by a number i from 1 to 2d in the increasing order A1 = (0, 0, … ,0), … , A2d = (1, 1, … ,1). Consider a parent bacterium at time n = 0: x(0) ∈ Ω. At time n = 1 (i.e. after the first division), the parent bacterium produces two offspring: ξ(1;1; x(0)) and ξ(1;2; x(0) from Ω. We assume that ξ(1;1; x(0)) and ξ(1;2; x(0)) are conditionally [conditioned on x(0)] independent random vectors and we introduce the transitional probabilities:

| (1) |

from which we form the 2d × 2d -matrix of transitional probabilities

| (2) |

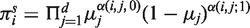

We assume that all pij > 0 and that on/off switching of genes happens independently, i.e. if we introduce 2d transitional probabilities:

| (3) |

then

|

(4) |

where α (i, j; m; l, k) = 1 if Ai has the m-th component equal to l and Aj has the m-th component equal to k, otherwise α(i, j;m; l, k) = 0. We also assume that the transition matrix P does not change with time.

We continue the dynamics so that at time n = 2 the bacteria ξ(1;1; x(0)) and ξ(1;2; x(0)) produce their four offspring and so on. This way we obtain a branching tree as a result of binary fission. Denote by Zk(n| x0), a number of bacteria of type Ak in the population after n divisions starting from the bacterium with x0 = x(0)  Ω. It obviously depends on a realization ω of the branching tree and its more detailed notation is Zk(n| x0) (ω). The collection Z(n| x0) (ω)={Zk(n| x0)(ω), k = 1, 2, … , 2d} gives us a population living on the set {1, 2, … , 2d} and

Ω. It obviously depends on a realization ω of the branching tree and its more detailed notation is Zk(n| x0) (ω). The collection Z(n| x0) (ω)={Zk(n| x0)(ω), k = 1, 2, … , 2d} gives us a population living on the set {1, 2, … , 2d} and  . Now, we randomly (i.e. each time independently) draw a member (i.e. a bacterium) from this population and ask the question with what probability its type is Ak. For a fixed ω (i.e. for a particular realization of the branching tree), the probability to pick a bacterium of the type Ak is equal to ρk(n|x0)(ω) =

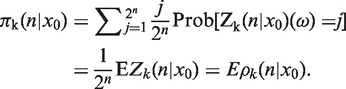

. Now, we randomly (i.e. each time independently) draw a member (i.e. a bacterium) from this population and ask the question with what probability its type is Ak. For a fixed ω (i.e. for a particular realization of the branching tree), the probability to pick a bacterium of the type Ak is equal to ρk(n|x0)(ω) =  Zk(n| x0)(ω). This is a random distribution analogous to the random measure appearing in Wright-Fisher-type models [see e.g. (28)]. Here we consider an average of the distribution ρk(n|x0)(ω). Assume that we can put together all possible realizations of the branching trees Z(n | x0)(ω1), Z(n| x0)(ω2), … occurring during binary fission after n divisions then the proportion of bacteria of the type Ak in this total collection is equal to

Zk(n| x0)(ω). This is a random distribution analogous to the random measure appearing in Wright-Fisher-type models [see e.g. (28)]. Here we consider an average of the distribution ρk(n|x0)(ω). Assume that we can put together all possible realizations of the branching trees Z(n | x0)(ω1), Z(n| x0)(ω2), … occurring during binary fission after n divisions then the proportion of bacteria of the type Ak in this total collection is equal to

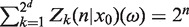

|

(5) |

The meaning of the average πk(n|x0) is as follows. If we take all possible binary trees (this is where we use the near infinite population size assumption) started from x0 and put their results after n-divisions together then this average gives us the proportion of bacteria of the type Ak Obviously, π(n|x0)=[π1(n|x0), π2(n|x0), … , π2d (n|x0)] is a probability measure defined on the set {1, … , 2d}. It is not difficult to compute πk(n|x0) using the earlier assumptions on transition probabilities (1)–(2) and obtain

| (6) |

where the vector π(0) is the initial distribution of x0 = Am for some m, i.e. it is the vector for which all components equal zero except an m-th component which equals 1. Instead of starting with a single bacterium, we can start with an initial population having distribution π(0). The Equation (6) remains valid but it should be kept in mind that in this case we average in Equation (5) both over the initial distribution and over all possible trees growing from each draw from π(0). Furthermore, in the above consideration we assumed that all offspring survive and the population size grows exponentially. Equation (6) remains valid when the number of bacteria of each type Ak dying at time t = n is proportional to πk(n|x0) under the condition that the population remains of a sufficiently large size N. The same modelling approach was used, e.g. in (29), though resulting in a different model within a different biological set-up. The considered model takes into account mutation drift only and does not include selection or bottlenecks.

Stationary distribution

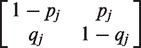

Under our assumption that pij > 0 the distribution π(n| π(0)) has the unique limit πs when n tends to infinity. The stationary distribution πs is independent of the initial distribution π(0) and is the eigenvector of the transition matrix P corresponding to the unit eigenvalue: πs = πs P. Using (3)–(4), we obtain that the components  of πs are equal to

of πs are equal to  , where α(i,j;l ) = 1 if the Ai type has the j-th gene in the state l and α(i,j;l ) = 0 otherwise, and μj = qj /( pj+qj), j=1, … ,d. The speed of convergence of π(n| π(0)) to πs depends on the transition matrix P and on the initial distribution π(0). The number of time steps (i.e. generations) ns required for π(n| π(0)) to reach a proximity of πs can be estimated via the maximum λ of the non-unit eigenvalues λj=1−pj−qj of the matrices Pj =

, where α(i,j;l ) = 1 if the Ai type has the j-th gene in the state l and α(i,j;l ) = 0 otherwise, and μj = qj /( pj+qj), j=1, … ,d. The speed of convergence of π(n| π(0)) to πs depends on the transition matrix P and on the initial distribution π(0). The number of time steps (i.e. generations) ns required for π(n| π(0)) to reach a proximity of πs can be estimated via the maximum λ of the non-unit eigenvalues λj=1−pj−qj of the matrices Pj = formed for each gene j from the transition matrix P. Roughly, ns ≈ ln[ε/||πs − π(0)||]/ln λ, where ||πs − π(0)|| is the (e.g. total variation) distance between the initial distribution π(0) and the stationary distribution πs and ε is the desirable closeness of π(ns| π(0)) and πs. The speed of convergence to the stationary distribution is limited by the gene with the lowest switching rate.

formed for each gene j from the transition matrix P. Roughly, ns ≈ ln[ε/||πs − π(0)||]/ln λ, where ||πs − π(0)|| is the (e.g. total variation) distance between the initial distribution π(0) and the stationary distribution πs and ε is the desirable closeness of π(ns| π(0)) and πs. The speed of convergence to the stationary distribution is limited by the gene with the lowest switching rate.

RESULTS

Conservation and tract lengths of polyG/polyC repeats in C. jejuni genomes

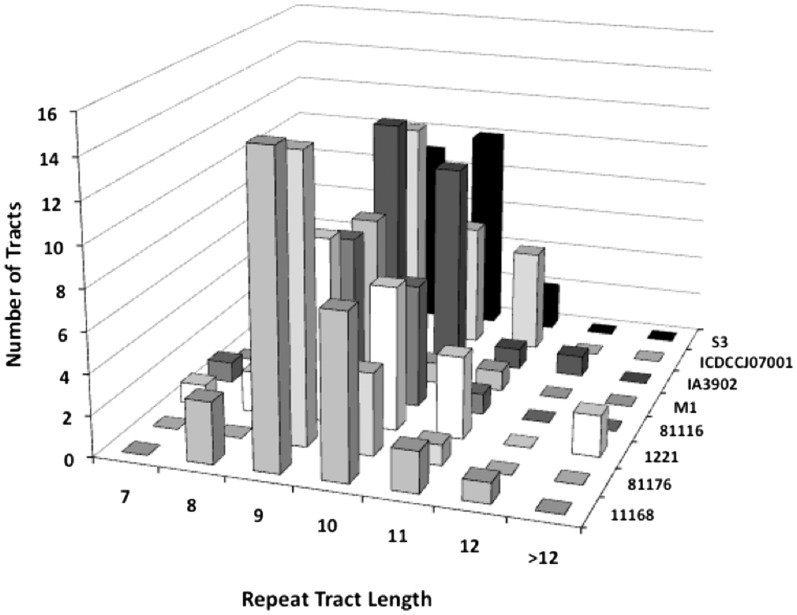

Campylobacter jejuni genomes contain multiple polyG or polyC mononucleotide repeat tracts. Eight genomes were analysed to ascertain the lengths and conservation of these tracts. The genomes contained 11–29 tracts of seven or more repeat units. The modal repeat number for the polyG/polyC tracts in seven of these genomes was nine and in the other was 10 with 64–95% of tracts containing 9 or 10 repeats (Figure 1). This pattern contrasts with the low GC content of these genomes (31%) and a dearth of G5, G6, G7 and G8 tracts (303, 18, 0 and 4 loci in strain NCTC11168, respectively). The four complete genomes (from strains NCTC11168, 81–176, 1221 and 81 116) were analysed to ascertain conservation of these tracts. A total of 55 repeat-associated loci were detected in these four genomes with the majority (80%) of these tracts being polyG repeats present within the reading frames and on the coding strand of genes (Supplementary Table SI). Only five loci were present and contained repeat tracts in all four genomes with only three of these tracts being within genes (Supplementary Figure S1). Overall, C. jejuni exhibits a high number of phase variable genes with a bias towards G9/G10 tracts but paradoxically only weak conservation of the PV mechanism in specific loci.

Figure 1.

Lengths of polyC/G repeat tracts in C. jejuni genomes. Published genome sequences (z-axis) were scanned for simple sequence repeat tracts containing seven or more C or G residues. The x-axis indicates the lengths of the tracts; the y-axis indicates the number of loci containing tracts of a particular length.

Phase variable genes of C. jejuni have high switching rates

The capA gene, encoding a 120-kDa autotransporter, of C. jejuni strain NCTC11168 contains a G11 repeat tract within the reading frame, which is preceded by a polyT tract of six residues depending on the source of the strain [Ashgar et al. (19) report this gene as having T5–G10 tracts]. Both directions of switching of this receptor were measured by colony immunoblotting with a CapA-specific polyclonal antiserum. The ON variants contained a G11 tract while OFF variants contained either G10 or G12 tracts. ON-to-OFF PV occurred at a rate of 1.6 × 10−3 mutations/division while OFF-to-ON PV rates were 1.8-fold higher for G12 variants or 3.3-fold lower for G10 variants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phase variation rates of C. jejuni genes

| Gene (reporter) | Direction of Switching |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| on-to-off |

off-to-on |

|||||

| Tracta (n) | Freq.b (×10−3) | Ratec (×10−4) | Tract (n) | Freq. (×10−3) | Rate (×10−4) | |

| cj1139 (lacZ-cat) | G8 (36) | 3.83 | 4.23 {1.0} (3.0–5.7) | G9 (24) | 1.81 | 2.15 {1.0} (1.4–2.8) |

| G11 (13) | 49.45 | 40.54 {9.5} (35.3–64.6) | G10 (17) | 3.39 | 3.67 {1.7} (3.2–4.8) | |

| cj1139 (lacZ-kan) | G8 (22) | 10.08 | 10.44 {2.5} (6.9–16.6) | G7 (7) | 0.65 | 1.00 {0.5} (2.8–0.5) |

| cj0031 (lacZ-cat) | G9 (15) | 13.52 | 12.30 {2.9} (9.1–22.2) | G10 (22) | 17.82 | 17.88 {8.3} (11.0–40.2) |

| capA (antibody) | G11 (14) | 18.44 | 16.41 {3.9} (11.2–30.9) | G12 (23) | 32.59 | 29.49 {13.7} (22.1–43.0) |

| G10 (11) | 4.29 | 4.88 {2.3} (2.5–8.3) | ||||

aNumbers in brackets indicate number of colonies examined

bMedian frequency

cPV rates were estimated according to (42), numbers in curly brackets are fold increase over shortest tract, numbers in square brackets are 95% CIs calculated according to (43). Statistical tests of differences in PV rates are provided in the Supplementary Data.

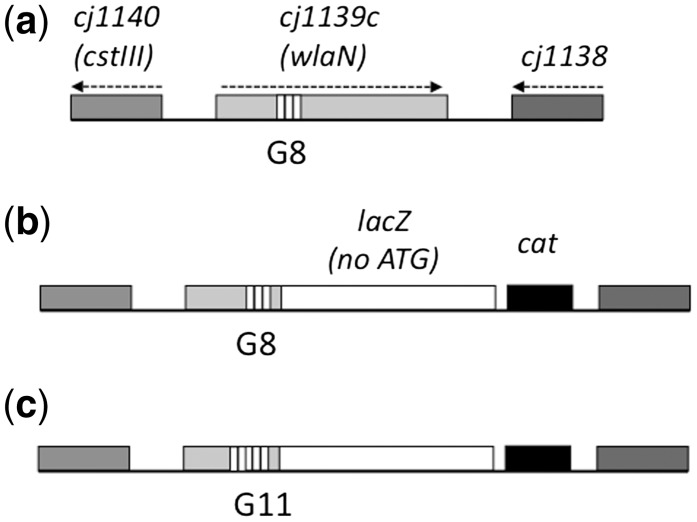

As antisera were not available for other phase variable epitopes or gene products, reporter constructs were created to analyse the PV rates of two other C. jejuni genes, cj1139 and cj0031. In both cases a lacZ gene lacking an initiation codon was fused in frame to the gene, such that changes in repeat number would alter β-galactosidase expression (Figure 2). The cj1139-lacZ reporter construct contains a G8 tract, which was altered by site-directed mutagenesis to a G11 tract (Figure 2). The cj0031-lacZ reporter construct contains a G9 tract at the 3′-end resulting in fusion of cj0031 with cj0032 upon changes in length of this tract. These constructs were recombined into the C. jejuni chromosome resulting in detection of high-level expression of β−galactosidase and phase variable changes in expression when these constructs were plated on MHA plates containing X-Gal (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the reporter constructs for cj1139c. The upper diagram, (a), represents the wild-type locus in C. jejuni strain NCTC11168. The ORFs are represented by shaded rectangles and the direction of transcription by dotted lines. The repeat tract in cj1139c is indicated by a series of small, white rectangles. The middle diagram, (b), represents the reporter construct. In this construct, a lacZ gene lacking a promoter and initiation codon was fused to cj1139c downstream of the repeat tract. A chloramphenicol cassette (cat) was inserted at the 3′-end of the lacZ gene and utilized as a selective marker during insertion of this construct into the chromosome of C. jejuni strain NCTC11168. The lower diagram, (c), shows the reporter construct containing a G11 repeat tract. This construct was derived from the G8 construct by site-directed mutagenesis of the repeat tract prior to recombination into the chromosome.

PV rates were measured for these constructs for both directions of switching. High PV rates were detected for all constructs with a trend for rates to increase as a function of tract length from 1 × 10−4 mutations/division with 11168-cj1139-G7-cat to 4.1 × 10−3 with 11168-cj1139-G11-cat (Table 1). The ON-to-OFF PV rates for the isogenic 11168-cj1139-G8-cat and 11168-cj1139-G11-cat constructs exhibited a significant difference (P < 0.0001; using a Mann–Whitney non-parametric rank sum test, InStat 2.0), with the 9.5-fold higher rate for the G11 construct demonstrating that tract length exerts a major effect on PV rates in this species. The observation of slightly higher PV rates for the 11168-cj1139-G8-kan as compared to 11168-cj1139-G8-cat suggests that PV rates are influenced by the context of the reporter. However, comparable rates were observed for the reporter constructs as compared to immunoblotting (e.g. PV rates for cj1139-G11-cat were 2.7-fold higher than for capA-G11 but similar for cj1139-G10-cat and capA-G10), indicating that the reporter constructs provide an accurate measure of switching rates. These results showed that C. jejuni PV rates are high and increase as a function of tract length.

Mutational patterns of C. jejuni genes vary as a function of tract length

The mutational events responsible for changes in expression in phase variants were examined by either sequencing or sizing of PCR products spanning the repeat tract. All PV events involved changes by a single repeat unit (Table 2). This means that the ON-to-OFF PV rates are measurements of a combination of insertions and deletions of single nucleotides while the OFF-to-ON PV rates measure either insertions (+1) or deletions (−1) of one repeat. Thus the OFF-to-ON PV rates for 11168-cj1139-G9 and 11168-cj0031-G10 provide measurements of −1 deletion rates while 11168-cj1139-G7 and 11168-cj1139-G10 are estimates of +1 rates. In the case of ON-to-OFF rates of the reporter constructs, we observed a preponderance of insertions over deletions for G8 and G9 tracts of 11:1 (11168-cj1139-G8-cat), 24:1 (11168-cj1139-G8-kan) and 6:1 (11168-cj0031-G9) but an opposing prevalence of deletions over insertions for G11 tracts of 23:1 (11168-cj1139-G11) or 2:1 (11168-capA-G11). Using the data for the lacZ reporter constructs, mutation rates (reported as mutations/division × 10−4) were estimated for a range of −1 repeat deletions (G8 to G7, G9 to G8, G10 to G9 and G11 to G10 were 0.4, 2.1, 17.9 and 38.8 respectively) and +1 repeat insertions (G7 to G8, G8 to G9, G9 to G10, G10 to G11 and G11 to G12 were 1.0, 6.9, 10.3, 3.7 and 1.8 respectively). A major difference was observed between these mutational events with a tract length dependent increase in the frequency of −1 deletions for G8 to G11 tracts whereas +1 insertional events exhibited a peak at a tract length of G9 and then decreased in frequency in longer tracts.

Table 2.

Mutational patterns of the phase variable genes of C. jejuni

| Gene (reporter) | Direction of Switching |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| on-to-off |

off-to-on |

|||||||

| Tract | −1 | +1 | Other | Tract | −1 | +1 | Other | |

| cj1139 (lacZ-cat) | G8 | 5 | 54 | 0 | G9 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| G11 | 46 | 2 | 2a | G10 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| cj1139 (lacZ-kan) | G8 | 3 | 73 | 0 | G7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| cj0031 (lacZ-cat) | G9 | 6 | 34 | 0 | G10 | 58 | 0 | 0 |

| capA (antibody) | G11 | 10 | 6 | 0 | G12 | 58 | 0 | 2a |

| G10 | 0 | 4 | 0 | |||||

aAll these variants had −2 deletions

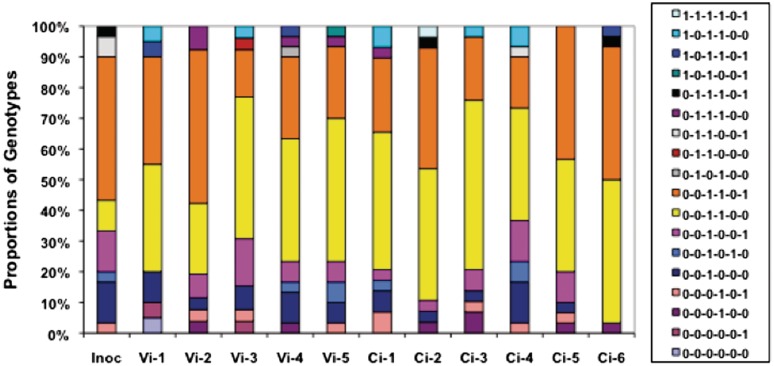

Minor changes in the genotypes of the phase variable genes of C. jejuni occur during in vitro passage

The high PV rates of C. jejuni genes suggested that changes in the proportions of variants for individual genes and for combinations of genes may occur rapidly during growth of populations of this bacterial species even in the absence of selection. To investigate the capacity for change, passage experiments were performed with a laboratory-adapted variant of C. jejuni strain NCTC11168. Six phase variable genes were examined, which included the three genes with determined PV rates (Table 1), a range of tract lengths (G8–G11), alternate positions of repeat tracts in the genes (i.e. start, middle and end; see Supplementary Table S1) and an alternate transcriptional orientation (C8, cj0685). An initial examination of the numbers of variants in single colonies grown on MHA plates only detected a low level of variants in agreement with the observed switching rates (Supplementary Table SII). This strain was then subjected to three rounds of growth in MHB using either a constant or variable initial inoculum (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table SIII). The tract lengths were determined for multiple colonies from the input and the eleven output populations using a multiplex PCR and a GeneScan assay (Supplementary Table SIV). The tract lengths, which were all present within the reading frames of the associated genes, were then converted into ON/OFF phenotypes (Supplementary Table SV). A significant change was observed only in the proportions of ON and OFF variants for capA, which went from 27% OFF in the input to an average of 56% OFF (±0.1) in the output populations. Combined genotypes for all six genes were derived for each colony and utilized for examination of changes in the complexity of the populations (Figure 3). A total of 18 genotypes were detected from a potential of 64 genotypes. The output populations were similar to each other and only differed markedly from the inoculum due to a decrease in 0–0–1–1–0–1 from 47% to 31% (±11.9) and an increase in 0–0–1–1–0–0 from 10% to 41% (±8.4), which correlated with an ON-to-OFF switch in the capA gene. The output populations for the variable inoculum samples were similar indicating that an initial inoculum of >105 cfu had not influenced population structure. In summary, short-term in vitro passage produced only limited genotypic variation in these six genes indicating that C. jejuni phase variable genotypes are relatively stable when passaged in a non-changing environment using large input populations.

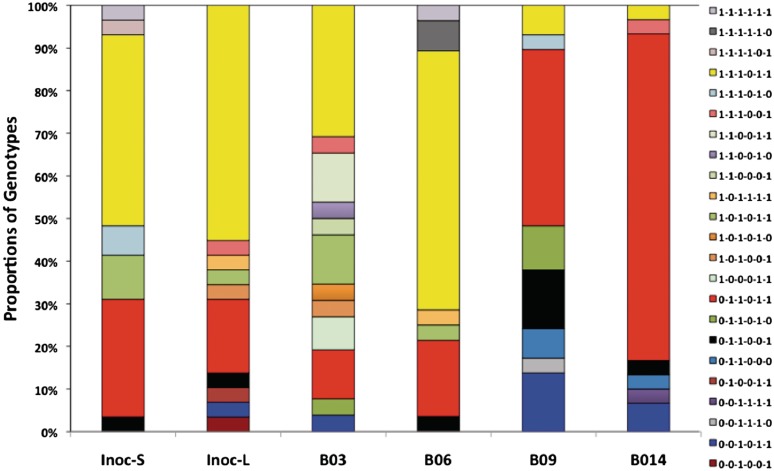

Figure 3.

Changes in the proportions of each genotype following in vitro passage of C. jejuni strain NCTC11168. An initial inoculum of either constant (Ci; 3.5 × 10−8 cfu) or variable (Vi; 3.5 × 10−8 to 3.5 × 10−4 cfu) size was subjected to three passages in 5 ml of MHB (see Supplementary Data for further details). Genotypes were derived from 30 colonies for the inoculum and each ouput sample by assigning a ‘1’ for an ‘on’ or ‘0’ an ‘off’ phenotype to each of six genes (cj1326, cj0031, cj1139, cj0685, cj0045 and capA, respectively) based on the numbers of repeats present within the gene. Inoc, inoculum; Vi-1 to Vi-5, variable inoculum samples; Ci-1 to Ci-6, constant inoculum samples.

Varying patterns of changes in the genotypes of the phase variable genes of C. jejuni occur during in vivo passage

Campylobacter jejuni is a commensal of chickens and colonization leads to high and persistent numbers of bacterial cells in the caecum. To explore the extent of PV occurring during colonization of this natural host, a group of 10 2-week-old chickens were inoculated with a high dose (1 × 108 cfu) of a hypermotile variant of C. jejuni strain NCTC11168. Five birds were sacrificed after 1 day and examined for the presence of C. jejuni in caecal contents. No growth was detected indicating a low level of initial colonization by this strain. Caecal contents from the other five birds were examined 2 weeks after inoculation and high levels of C. jejuni cells were detected (ranging from 1.6 × 107 to 4 × 108 cfu/g caecal contents). A DNA isolation procedure was performed on caecal contents and C. jejuni genes were readily amplified from these extracts. Repeat tracts lengths were determined for six genes for 30 colonies from the inoculum and each bird and for the DNA extracts. Comparisons were performed between the major repeat tract length detected in DNA extracts and the genotype present in the majority of colonies (Supplementary Tables SVI and SVII). For four of the genes (cj0031, cj0685, cj1139 and cj1326) the lengths were identical. Differences were detected for capA in B11 and for cj0045 in the inoculum, B8 and B9 samples but in most of these cases; the ratios between major and minor peaks identified by GeneScan were low indicating that a mixture of variants was present in the sample (Supplementary Table SVI). These results provided evidence that the growth (∼20 generations) required to generate the colonies had not generated large variations in the ON/OFF status of the phase variable genes such that analysis of multiple colonies provides an accurate reflection of in vivo genotypes.

Analysis of the genotypes in the input and output samples for the infections with C. jejuni strain NCTC11168H detected significant changes from the inoculum in the proportions of variants for three genes (Supplementary Table SVIII):- cj0031, switched from OFF (G10) to ON (G9); cj1139 switched from ON (G8) to OFF (G9); and cj0685 switched from OFF (G8) to ON (G9) (P-values of <0.0001 were obtained in a Chi-squared test for each bird for each gene as compared to the inoculum using InStat 1.0). There were also bird-to-bird variations in the ON/OFF variants for cj0045 in birds B8 and B9 (P-values of <0.001 were obtained for comparisons with data from B6 and B11) and for capA in birds B7 and B8 (P-values of <0.01 were obtained for B7 versus B11, B8 versus B9 and B8 versus B11 and 0.04 for B7 versus B9). These differences were reflected in major differences in genotype distributions between the inoculum and output populations (Figure 4). A total of 22 genotypes were detected. Nine genotypes were present in the inoculum but only three of these genotypes were detected in output populations and in each case in only one bird. The bird-to-bird variations were mostly due to differences in the levels of two variants—0–1–0–1–0–0 and 0–1–0–1–0–1—which exhibit opposing ON/OFF phenotypes for capA. The major shift in the genotypes detected during this in vivo passage experiment highlights the significant potential for infection to alter population structure of the C. jejuni phase variable genes.

Figure 4.

Changes in the proportions of genotypes following in vivo passage of a hypermotile variant of C. jejuni strain NCTC11168. Two-week-old out-bred chickens were inoculated with 1 × 108 cfu. Caecal samples were collected 2 weeks after inoculation and C. jejuni was enumerated by growth of dilutions on selective plates. The genotypes for phase variable genes were derived by the same approach as in Figure 3 for the same six genes. Genotypes were derived for 30 colonies from the inoculum and for 23–29 colonies from output populations following growth under identical conditions. Inoc, inoculum; B6–B11, individual birds.

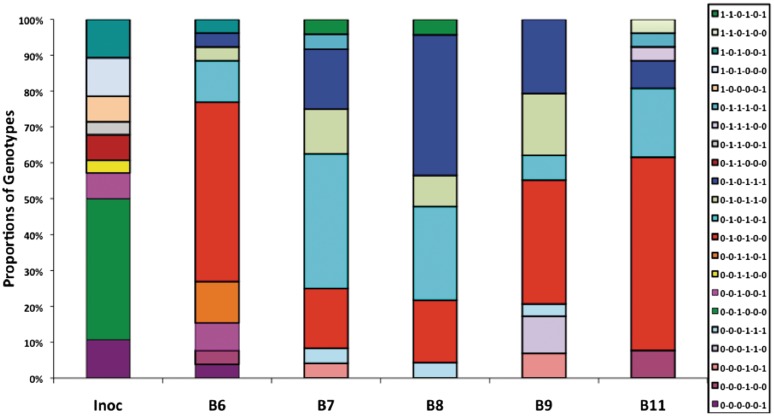

As prior adaptation of a strain to replication in chickens may result in selection of specific ON/OFF phases and in order to examine the patterns of PV in other C. jejuni strains, a second experiment was performed with a chicken-adapted variant of a widely-utilized C. jejuni strain, 81–176. Output populations were again generated 2 weeks after initial inoculation. Four of the genes examined in strain 11 168 were absent or non-phase variable in this strain but homologues of cj0045 (cj81176-0083) and cj0685 (cj81176-0708) were present although cj81176-0083 is a pseudogene. These genes plus four other genes were examined covering C9, G9 and G10 tracts in the start, middle and end of the phase variable genes of strain 81–176. Significant differences were only detected for gene 81176-0083 between the outputs from birds B09 and B014 in comparison to the inoculum and the outputs from birds B03 and B06 (Supplementary Table SX and XI). In this experiment, 23 genotypes were observed (using G11 as an arbitrary ON repeat number for gene 81176-0083) with the major difference being variation in the levels of 1–1–1–0–1–1 and 0–1–1–0–1–1, which differ in the repeat tract lengths of 81176-0083 (Figure 5). This experiment highlighted the potential for bird-to-bird variation in the tract lengths of phase variable genes but otherwise was indicative of the stability of these tracts over a 2-week period of persistence in broiler chickens.

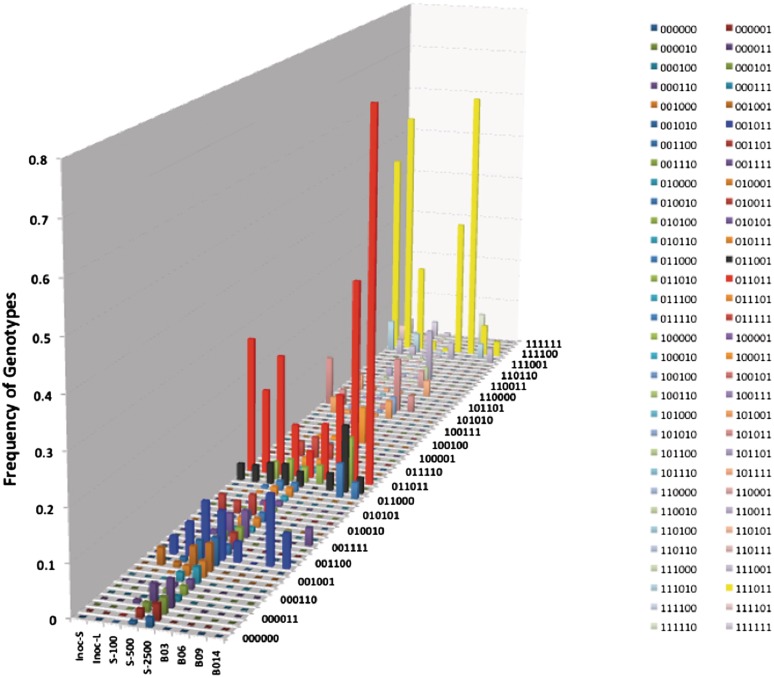

Figure 5.

Changes in the proportions of genotypes following in vivo passage of a chicken-adapted variant of C. jejuni strain 81–176. The genotypes were derived by the same approach as in Figure 4 for the following six genes: 81176-0083, 81176-0646, 81176-0708, 81176-1160, 81176-1312 and 81176-1325. Genotypes for 29 small colonies (Inoc-S) and 29 large colonies of the inoculum were derived following growth on campylobacter selective plates. The genotypes for output populations were derived for 26–30 colonies from dilutions of caecal samples grown under identical conditions. Caecal samples were collected 2 weeks after inoculation of chickens with 1 × 108 cfu. Inoc-S, small colonies in inoculum; Inoc-L, large colonies in inoculum; B03, B06, B09 and B014, individual birds.

Modelling of the impact of mutational drift on the genotypic diversity of a phase variable population

The proportions of phase variants within a population can change due to a combination of mutational drift, population bottlenecks and selection. The high PV rates of the C. jejuni genes suggested that changes in the proportions of genotypes could have occurred solely due to mutational drift. A theoretical model (see its description below in Section ‘Stochastic model’) was developed to examine the impact of mutational drift on population structure. A major assumption of this stochastic model was that each gene was switching independently of all the other genes. This assumption was tested by generating a theoretical distribution of genotypes from the measured number of ON and OFF variants for each gene and performing a comparison to the observed distribution derived from analysis of each colony. For most (>80%) of the major genotypes in both the in vitro and in vivo passage experiments, the proportions of observed genotypes were within the confidence intervals calculated for the theoretical distribution (Supplementary data and Supplementary Table SIX). In contrast, proportions for the minor genotypes observed in 1–2 colonies were outside these error bars. In general these results indicated that the assumption was valid and could be used to evaluate the impact of mutational drift on changes in the populations.

The inputs to the model were the observed PV rates, the initial distribution and the number of generations. Each gene was assumed to switch at the rates determined using the reporter constructs and to oscillate between two tract lengths indicative of an ON and OFF state e.g. G8 (ON) and G9 (OFF) for cj1139. For the in vitro passage assay, the number of generations was estimated as 15–30 depending on inoculum size and viability of the cells after overnight growth. The model predicted the rapid generation of minor genotypes, some of which were observed in output populations (e.g. 0–1–1–1–0–0, 1–0–1–0–0–1, Supplementary Figure S2B), and that equivalence of the 0–0–1–1–0–0 and 0–0–1–1–0–1 genotypes would be reached after 100 generations at a frequency of ∼0.2 (Supplementary Figure S2A). The genotype distributions from individual output populations were not significantly different from the inoculum distribution but significance (P = 0.01) was observed in a comparison between inoculum and the average output of all 11 cultures [using a one-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test]. Using the inoculum population as an input, theoretical output populations diverged from observed outputs as the model was run for 100 or more generations. A switch to a high prevalence (frequencies of >0.3) of the 0–0–1–1–0–0 genotype after 20 generations could only be achieved in the model by increasing the capA ON-to-OFF and cj0685 OFF-to-ON rates by 10-fold resulting in convergence of the model and average output population to a non-significant difference. Overall these analyses indicated that the model was providing a reliable measure of the changes in the experimental populations but also suggests that a low level of selection is acting on PV of capA and cj0685 during in vitro passage.

The in vivo populations were modelled for up to 5000 generations as the actual number of generations can only be roughly estimated. For colonization experiments with strain NCTC11168 (Figure 6), the model predicted the generation of some novel genotypes (e.g. 1–1–0–1–0–0 reached 19% by 5000 generations) but only very low levels of the genotypes actually observed in output populations from chickens (e.g. 0–1–0–1–0–0, 0–1–0–1–0–1 and 0–1–0–1–1–1 were present at 11%, 1% and 0.1%, respectively, in model outputs after 5000 generations but at an average of 34%, 20% and 18%, respectively, in experimental outputs). These distributions were significantly different from the inoculum for each individual output population or using an average of all the outputs from all the birds (P = 0.01 using the KS test). A non-significant difference between model and experimental data could only be attained by significantly altering the PV rates of multiple genes (data not shown), indicating that the differences between these distributions were not solely due to inaccuracies in the switching rates. These results indicated that the genotype profile observed in vivo with strain 11 168 was not due to the mutational drift associated with the high PV rates.

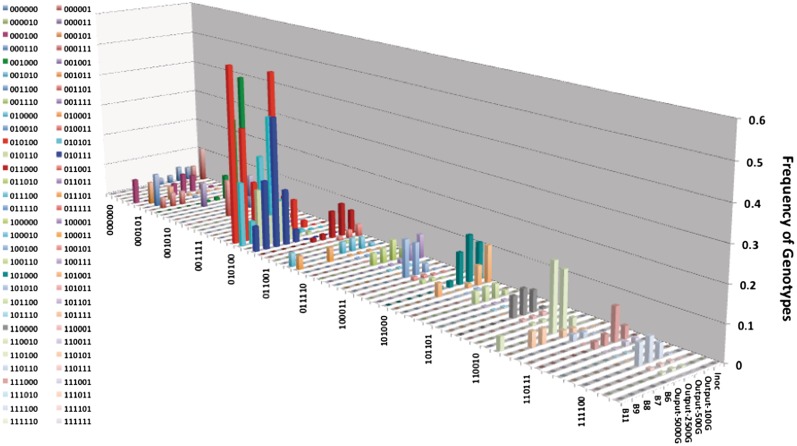

Figure 6.

Comparison of the changes in proportions of phase variable genotypes for theoretical and experimental in vivo passaged populations of strain NCTC11168. The proportions of genotypes for the inoculum were used as input to the theoretical model of PV, which was then run for a varying number of generations. Genotypes were for the six genes with 0 representing an OFF phase variant and 1 an ON variant. The order of the genes and the ON-to-OFF and OFF-to-ON switching rates (×10−4) were as follows: cj1326, 10.3, 17.9; cj0031, 10.3, 17.9; cj1139, 6.9, 2.1; cj0685, 2.1, 6.9; cj0045, 38.8, 3.7; capA, 38.8, 3.7. Inoc, inoculum; Ouput-100 G,-500 G,-2500 G and-5000 G, are output data from the model for runs of 100, 500, 2500 and 5000 generations; B6, B7, B8, B9 and B11 are experimental data for output populations obtained from five different chickens.

For the experiments with strain 81–176 (Figure 7), the model predicted that, the two major input genotypes, 0–1–1–0–1–1 and 1–1–1–0–1–1, would be reduced to 8% and 4%, respectively, after 500 generations and to <5% after 2500 generations whereas these genotypes were present at 11–76% and 3–61% in the different output populations. Low levels of novel genotypes are generated after 2500 generations at varying levels but few of these were seen in output populations and there was little overlap between predicted and observed genotype frequencies (Figure 7). Statistical analyses of these distributions using the KS test detected significant differences between inoculum and outputs from birds B03 and B06 but not from birds B09 and B014. Observed and theoretical output populations exhibited significant divergence after 100 generations (P = 0.01) but convergence in the case of B09 to non-significance by 500 generations. Again, the divergence between the predictions of the model and observed populations suggests that mutational drift is not responsible for observed in vivo genotype profiles.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the changes in proportions of phase variable genotypes for theoretical and experimental in vivo passaged populations of strain 81–176. The proportions of genotypes for the inoculum were used as input to the theoretical model of PV, which was then run for a varying number of generations. Genotypes were for the six genes with 0 representing an OFF phase variant and 1 an ON variant. The order of the genes and the ON-to-OFF and OFF-to-ON switching rates (×10−4) were as follows: 81176-0083, 38.8, 3.7; 81176-0646, 17.9, 10.3; 81176-0708, 10.3, 17.9; 81176-1160, 17.9, 10.3; 81176-1312, 10.3, 17.9; 81176-1325, 10.3, 17.9. Inoc-S, small colonies in inoculum; Inoc-L, large colonies in inoculum; S-100, S-500 and S-2500 are output data from the model for runs of 100, 500 and 2500 generations using Inoc-S as the input to the model; B03, B06, B09 and B014 are experimental data for output populations obtained from four different chickens.

The high switching rates of C. jejuni phase variable genes predict the rapid appearance of a steady state for the frequencies of genotypes. The time required and nature of this steady state was predicted using the model. With six genes switching at the highest rate (i.e. 0.004) and starting with all genes in an OFF state, then 744 generations were required to reach the steady state. A 10-fold reduction in one or both directions of switching for one gene increased the time to 1400 and 7500 generations, respectively. For the actual populations described in this study, the steady state was reached in 6600, 6600 and 2000 generations for the in vitro, in vivo strain NCTC11168 and in vivo strain 81–176 assays, respectively. Comparisons also indicated that the inoculum populations for these experiments were not already at the steady-state (Supplementary Figure S2, Figures 6 and 7). The larger numbers for the former two cases were due to two of the genes, cj1139 and cj0685, exhibiting low ON-to-OFF switching due to a G8 to G9 insertion. Critically, the steady state population contains small numbers of many genotypes rather than a bias to high frequencies of a few genotypes contrasting with the actual distributions observed in the in vivo output populations (Figures 6 and 7).

DISCUSSION

Several important bacterial pathogens utilize SSR-mediated PV to modulate expression of surface molecules and to alter interactions with their hosts (1–4). Campylobacter jejuni, a food-borne pathogen responsible for a large health and economic burden world-wide, contains multiple phase variable genes which exhibit ON/OFF switches in expression due to mutations in mononucleotide repeats of G or C nucleotides located within the reading frames (6). Using chromosomally-located reporter constructs in two phase variable genes, ON-to-OFF PV rates were measured for G8, G9 and G11 tracts and found to have high rates of 4.2 × 10−4, 1.2 × 10−3 and 4.1 × 10−3 mutations/division, respectively. Measurement of the PV rate by colony immunoblotting for the G11 tract of the native capA gene detected an ON-to-OFF switching rate of 1.6 × 10−3 mutations/division. The high switching rates of the C. jejuni genes are similar to the PV rates mediated by tetranucleotide repeats in H. influenzae, which ranged from 1.4 to 5.6 × 10−4 mutations/division for tracts of 17–38 repeats. The C. jejuni PV rates are, however, significantly higher than detected for polyG tracts in N. meningitidis but similar to PV rates detected in MMR mutants of this species (PV frequencies for meningococci rose from 1 to 3 × 10−5 in wild-type strains to 2–8.3 × 10−3 for a mutS mutant for G10 and G12 tracts whereas in C. jejuni a G11 tract has a PV frequency of 1.8 × 10−2 or 5 × 10−2 for the capA and cj1139lacZ genes, respectively). While the absence of homologues of the canonical mutS and mutL MMR genes in C. jejuni may indicate the lack of a functional MMR system, the mutation rates due to point mutations as measured by generation of nalidixic acid or ciprofloxacin resistance are low (1 × 10−8 to 1 × 10−9) for most strains (30,31), suggesting the presence of systems for repair of mismatched base pairs. Contrastingly, the high PV rates in C. jejuni may arise because this species lacks a system for efficient repair of the insertion and deletion mutations associated with polyG/C repeat tracts.

Tract length is a major determinant of the mutability of SSRs. Alteration of the G8 tract in cj1139 to G11 by site-directed mutagenesis increased the switching rate by 10-fold. Tract length is, therefore, a major determinant of PV in C. jejuni as observed for PV in other bacterial species (5,9). Strikingly, a change in the pattern of mutations in the C. jejuni reporter constructs was observed from a bias towards insertions in G8 and G9 tracts to deletions in G10 and G11 tracts. Biases in the correction of insertions and deletions have been detected in other systems (32–36) with an indication of a shift from correction of indels by the proof-reading subunits of DNA polymerase to MMR as mononucleotide tract length exceeds 7–8 nt (35,36). Thus the mutational spectra in the C. jejuni polyG tracts may reflect a transition from relatively efficient repair of −1 deletions in G7/G8 tracts to absence of repair in G10/G11 tracts and hence a shift in the mutational spectra. Alternatively, there may be another repair pathway active in this species. The most intriguing aspect is, however, that these mutational spectra are reflected in the prevalence of G9 and G10 tracts in the phase variable genes of C. jejuni, suggesting that tract length is determined by molecular drivers rather than by selection for a particular switching rate. Repeat numbers for polyG tracts in meningococcal genomes tend to be longer, probably due to selection for PV rate as these tracts have lower mutation rates in meningococci due to the presence of an active MMR system. Other Campylobacter species exhibit larger numbers of and longer polyG/polyC tracts than C. jejuni, e.g. C. upsaliensis contains 89 tracts of G7 or more of which 59 contain 12 or more repeats (37). Our results suggest that divergence between the Campylobacter genomes in the polyG tracts may be driven by differences in the ability of the replicative machinery or repair systems to correct mutations in these tracts rather than selection for heightened PV rates.

Multiple phase variable genes enable bacterial species to rapidly access a significant amount of genetic diversity (38). Six genes switching between ON and OFF results in 64 different genotypes while 27 genes will generate 1.3 × 108 genotypes. However, the high PV rates detected for the C. jejuni genes means that populations of this bacterial species will rapidly reach a steady state combination of genotypes. Utilizing the measured PV rates for different tract lengths and a model of independent switching of each locus, we estimate that C. jejuni populations will reach this steady state in 2000 to 7000 generations for six genes depending on the tract lengths of these genes. These measurements assume that the environments encountered in vivo do not induce a change in the PV rates. The rate of approach to this steady state is limited by the gene with the lowest switching rate. If we assume a replication time of 1 h and a population of sufficient size (>1 × 108 cfu), then this steady state will be reached in 12 to 42 weeks. C. jejuni can persist in the caeca of chickens at high levels for >12 weeks and so this steady state might be achieved in some hosts. Our observations indicate, however, that other factors might prevent C. jejuni populations from reaching this mutation-driven steady state.

Two different patterns were observed in the in vivo experiments. In one case (Figure 4), we observed major differences between the input and output populations in the ON and OFF states of multiple genes. These differences could not be replicated by the model and are strongly suggestive of selection acting on some these loci (although we cannot dismiss the possibility of changes due to other process such as hitch-hiking with a mutation in another part of the genome). In the second case (Figure 5), we observed evidence of bird-to-bird variation in the prevalence of two genotypes and absence of the minor genotypes predicted by the model to start appearing between 100 and 500 generations. The absence of the minor genotypes may be due to the limited numbers of colonies examined but the bird-to-bird variation is suggestive of a random reduction in population size or a ‘bottleneck’. This is particularly likely because the gene, 81176-0083, exhibiting most difference is a pseudogene. Both selection and bottlenecks will prevent C. jejuni populations from reaching the mutational steady state with small bottlenecks resulting in constant re-setting of the genetic diversity of the population back to the major genotypes or indeed oscillation between major genotypes if the bottleneck is small enough. Bottlenecks may arise due to the daily excretion of the caecal material and re-colonization of the new contents by bacterial cells attached to the epithelium of the caeca or from other parts of the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, there are major bottlenecks and selective pressures associated with transmission and initial colonization of birds. Similarly, an adaptive response is elicited during persistence of C. jejuni in birds (24,39) and these immune responses may impose significant levels of selection for variation in the ON/OFF states of phase variable genes.

Finally, a feature of all the observations of the C. jejuni populations is for a significant level of genetic variation due to variations in the ON/OFF status of the phase variable genes. The functions of many of these genes are unknown or poorly characterized but this variation is likely to cause variations in host colonization and persistence between C. jejuni isolates of the same strain. The failure of signature-tagged mutagenesis screens and subsequent evidence of variable colonization levels between isogenic WITS-tagged isolates may be due to differences in the expression status of phase variable genes (20). High levels of genetic variation are generated by the high PV rates of C. jejuni genes and should be of major concern during design of experiments with this bacterial species. This high level of PV-generated phenotypic variation may facilitate survival of this species during adaptation to a range of hosts and environments but may have most impact on survival of the diverse bacteriophage populations known to infect Campylobacter and to attach to phase variable epitopes (40,41).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables I–XI, Supplementary Figures 1–3; Instructions for use of the theoretical model; Theoretical Model.

FUNDING

BBSRC [BB/G003416/1], “Dissecting the role of the Campylobacter haem uptake system in host colonization and disease”; RCUK Fellowship (to C.D.B.). Funding for open access charge: University of Leicester.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Pauline van Diemen and Mark Stevens (Institute for Animal Health, Compton) for provision of in vivo samples of strain 81–176. The authors would also like to thank Richard Haig, Philippe Materne, Isabella Petrovic, Nathalie Ingouf, and Jacques Marlet who contributed to this work. The authors thank Alexander Gorban for useful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayliss CD. Determinants of phase variation rate and the fitness implications of differing rates for bacterial pathogens and commensals. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009;33:504–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deitsch KW, Lukehart SA, Stringer JR. Common strategies for antigenic variation by bacterial, fungal and protozoan pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:493–503. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moxon ER, Bayliss CD, Hood DW. Bacterial contingency loci: the role of simple sequence DNA repeats in bacterial adaptation. Ann. Rev. Genet. 2007;40:307–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Woude MW, Baumler AJ. Phase and antigenic variation in bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004;17:581–611. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.3.581-611.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bolle X, Bayliss CD, Field D, van de Ven T, Saunders NJ, Hood DW, Moxon ER. The length of a tetranucleotide repeat tract in Haemophilus influenzae determines the phase variation rate of a gene with homology to type III DNA methyltransferases. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:211–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkhill J, Wren BW, Mungall K, Ketley JM, Churcher C, Basham D, Chillingworth T, Davies RM, Feltwell T, Holroyd S, et al. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature. 2000;403:665–668. doi: 10.1038/35001088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders NJ, Jeffries AC, Peden JF, Hood DW, Tettelin H, Rappouli R, Moxon ER. Repeat-associated phase variable genes in the complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58. Mol. Micro. 2000;37:207–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson AR, Stojiljkovic I. Mismatch repair and the regulation of phase variation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Micro. 2001;40:645–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson AR, Yu Z, Popovic T, Stojiljkovic I. Mutator clones of Neisseria meningitidis in epidemic serogroup A disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6103–6107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092568699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin P, Sun L, Hood DW, Moxon ER. Involvement of genes of genome maintenance in the regulation of phase variation frequencies in Neisseria meningitidis. Microbiology. 2004;150:3001–3012. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linton D, Gilbert M, Hitchen PG, Dell A, Morris HR, Wakarchuk WW, Gregson NA, Wren BW. Phase variation of a beta-1,3 galactosyltransferase involved in generation of the ganglioside GM1-like lipo-oligosaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;37:501–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlyshev AV, Champion OL, Churcher C, Brisson JR, Jarrell HC, Gilbert M, Brochu D, St Michael F, Li J, Wakarchuk WW, et al. Analysis of Campylobacter jejuni capsular loci reveals multiple mechanisms for the generation of structural diversity and the ability to form complex heptoses. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:90–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wassenaar TM, Wagenaar JA, Rigter A, Fearnley C, Newell DG, Duim B. Homonucleotide stretches in chromosomal DNA of Campylobacter jejuni display high frequency polymorphism as detected by direct PCR analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002;212:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermans D, Van Deun K, Martel A, Van Immerseel F, Messens W, Heyndrickx M, Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F. Colonization factors of Campylobacter jejuni in the chicken gut. Vet. Res. 2011;42:82. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young KT, Davis LM, Dirita VJ. Campylobacter jejuni: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:665–679. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sivadon V, Orlikowski D, Rozenberg F, Quincampoix JC, Caudie C, Durand MC, Fauchere JL, Sharshar T, Raphael JC, Gaillard JL. Prevalence and characteristics of Guillain-Barre syndromes associated with Campylobacter jejuni and cytomegalovirus in greater Paris. Pathol. Biol. 2005;53:536–538. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerry P, Szymanski CM, Prendergast MM, Hickey TE, Ewing CP, Pattarini DL, Moran AP. Phase variation of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176 lipooligosaccharide affects ganglioside mimicry and invasiveness in vitro. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:787–793. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.2.787-793.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Alphen LB, Wuhrer M, Bleumink-Pluym NM, Hensbergen PJ, Deelder AM, van Putten JP. A functional Campylobacter jejuni maf4 gene results in novel glycoforms on flagellin and altered autoagglutination behaviour. Microbiology. 2008;154:3385–3397. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019919-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashgar SS, Oldfield NJ, Wooldridge KG, Jones MA, Irving GJ, Turner DP, Ala'Aldeen DA. CapA, an autotransporter protein of Campylobacter jejuni, mediates association with human epithelial cells and colonization of the chicken gut. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:1856–1865. doi: 10.1128/JB.01427-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coward C, van Diemen PM, Conlan AJ, Gog JR, Stevens MP, Jones MA, Maskell DJ. Competing isogenic Campylobacter strains exhibit variable population structures in vivo. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:3857–3867. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02835-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrixson DR. A phase-variable mechanism controlling the Campylobacter jejuni FlgR response regulator influences commensalism. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:1646–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerome JP, Bell JA, Plovanich-Jones AE, Barrick JE, Brown CT, Mansfield LS. Standing genetic variation in contingency loci drives the rapid adaptation of Campylobacter jejuni to a novel host. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson DL, Rathinam VA, Qi W, Wick LM, Landgraf J, Bell JA, Plovanich-Jones A, Parrish J, Finley RL, Mansfield LS, et al. Genetic diversity in Campylobacter jejuni is associated with differential colonization of broiler chickens and C57BL/6J IL10-deficient mice. Microbiology. 2010;156:2046–2057. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.035717-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones MA, Marston KL, Woodall CA, Maskell DJ, Linton D, Karlyshev AV, Dorrell N, Wren BW, Barrow PA. Adaptation of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168 to high-level colonization of the avian gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:3769–3776. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3769-3776.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Vliet AH, Wooldridge KG, Ketley JM. Iron-responsive gene regulation in a Campylobacter jejuni fur mutant. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:5291–5298. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5291-5298.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood AC, Oldfield NJ, O'Dwyer CA, Ketley JM. Cloning, mutation and distribution of a putative lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis locus in Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiology. 1999;145(Pt 2):379–388. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiser JN, Love JM, Moxon ER. The molecular mechanism of phase variation of H. influenzae lipopolysaccharide. Cell. 1989;59:657–665. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crow J, Kimura M. An introduction to population genetic theory. New York: Harper & Row; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardwick RJ, Tretyakov MV, Dubrova YE. Age-related accumulation of mutations supports a replication-dependent mechanism of spontaneous mutation at tandem repeat DNA Loci in mice. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26:2647–2654. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaasbeek EJ, van der Wal FJ, van Putten JP, de Boer P, van der Graaf-van Bloois L, de Boer AG, Vermaning BJ, Wagenaar JA. Functional characterization of excision repair and RecA-dependent recombinational DNA repair in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:3785–3793. doi: 10.1128/JB.01817-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanninen ML, Hannula M. Spontaneous mutation frequency and emergence of ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:1251–1257. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dornberger U, Leijon M, Fritzsche H. High base pair opening rates in tracts of GC base pairs. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6957–6962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gawel D, Jonczyk P, Bialoskorska M, Schaaper RM, Fijalkowska IJ. Asymmetry of frameshift mutagenesis during leading and lagging-strand replication in Escherichia coli. Mutat. Res. 2002;501:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gragg H, Harfe BD, Jinks-Robertson S. Base composition of mononucleotide runs affects DNA polymerase slippage and removal of frameshift intermediates by mismatch repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:8756–8762. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8756-8762.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroutil LC, Register K, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. Exonucleolytic proofreading during replication of repetitive DNA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1046–1053. doi: 10.1021/bi952178h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran HT, Keen JD, Kricker M, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA. Hypermutability of homonucleotide runs in mismatch repair and DNA polymerase proofreading yeast mutants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:2859–2865. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fouts DE, Mongodin EF, Mandrell RE, Miller WG, Rasko DA, Ravel J, Brinkac LM, DeBoy RT, Parker CT, Daugherty SC, et al. Major structural differences and novel potential virulence mechanisms from the genomes of multiple campylobacter species. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conlan AJ, Coward C, Grant AJ, Maskell DJ, Gog JR. Campylobacter jejuni colonization and transmission in broiler chickens: a modelling perspective. J R Soc. Interface. 2007;4:819–829. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Zoete MR, van Putten JP, Wagenaar JA. Vaccination of chickens against Campylobacter. Vaccine. 2007;25:5548–5557. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sorensen MC, van Alphen LB, Harboe A, Li J, Christensen BB, Szymanski CM, Brondsted L. The F336 bacteriophage recognizes the capsular phosphoramidate modification of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:6742–6749. doi: 10.1128/JB.05276-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coward C, Grant AJ, Swift C, Philp J, Towler R, Heydarian M, Frost JA, Maskell DJ. Phase-variable surface structures are required for infection of Campylobacter jejuni by bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:4638–4647. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00184-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drake JW. A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:7160–7164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kokoska RJ, Stefanovic L, Tran HT, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA, Petes TD. Destabilization of yeast micro- and minisatellite DNA sequences by mutations affecting a nuclease involved in Okazaki fragment processing (rad27) and DNA polymerase delta (pol3-t) Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:2779–2788. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.