Abstract

Objective

While most allergic responses to food are directed against protein epitopes and occur within 30 minutes of ingesting the allergen, recent studies suggest that delayed reactions may occur, sometimes mediated by IgE antibodies directed against carbohydrate moieties. The objective of this review is to summarize the clinical features and management of delayed hypersensitivity reactions to mammalian meat mediated by IgE antibodies to galactose-alpha 1,3-galactose (alpha-gal), an oligosaccharide.

Methods

A PubMed search was conducted with MeSH terms: galactosyl-(1,3) galactose, oligosaccharides, cetuximab, allergy/hypersensitivity, and anaphylaxis. Reported cases with alpha-gal-mediated reactions were reviewed. This research study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of East Tennessee State University.

Results

Thirty-two cases of adults presenting with red-meat induced allergy thought to be related to oligosaccharides have been reported in the literature so far, making this a rare and evolving syndrome. Most of these patients demonstrated delayed reactions to beef, as was seen in the case reported by us in this manuscript. IgE specific to alpha-gal was identified in most patients with variable response to skin testing with beef and pork. Inhibition studies in some cases showed that the IgE antibodies to beef were directed towards alpha-gal in the meat rather than the protein. The patients often reported history of tick bites, the significance of which is unclear at present. Reactions to cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody, are mediated by a similar mechanism, with IgE antibodies directed against an alpha-gal moiety incorporated in the drug structure.

Conclusion

Alpha-gal is an oligosaccharide recently incriminated in delayed anaphylactic reactions to mammalian meats such as to beef, pork, and lamb. It appears that anaphylactic reactions to the anti-cancer biological agent, cetuximab, may be linked mechanistically to the same process. More studies are required to understand the underlying molecular basis for these delayed reactions in specific, and their broader implications for host defense in general.

Keywords: Galactosyl-(1,3) galactose; Oligosaccharides; Cetuximab; Anaphylaxis; Food allergy; Delayed hypersensitivity

Introduction

Beef Allergy and the New Evolving Syndrome

Food allergy remains a well-recognized problem that affects people of different ages and can alter their quality of life [1,2]. Its prevalence and incidence seem to be increasing over the past years [3-7] with more cases of food-induced anaphylaxis being reported [8-11]. Food hypersensitivity reactions are usually mediated by IgE antibodies against the incriminated food allergens such as eggs, seafood, milk, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soy, and rarely beef (Additional file 1: Table S1) [8,10-13]. The development of IgE-mediated reaction to a food that was well tolerated in the past sometimes constitutes a true diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to the patient and the physician [14]. The prevalence of food allergy has been increasing, with up to 4% of children having allergic reactions to one or more foods, of which reactions to peanut, soy, wheat, and seafood are probably most common [8,10-15]. While clinical tolerance to food allergens occurs in many children, some such as peanut and shell fish are characterized by the tenacity of the sensitization and persistence of sensitivity into adulthood [12,13,15-17].

Among food allergies, hypersensitivity to red meat is less common [18-22]. It was not adequately studied until recently, with a few reports emphasizing the probable cross reactivity between beef, cow's milk, and other types of red meat [23-31]. Some of the reactions, referred to as "pork-cat syndrome", involve cross-reactivity between cat epithelial allergens and pork [32-39]. The presentations of allergic reactions to meat, as reported in the literature, are reviewed in Additional file 2: Table S2. These include allergic reactions to meat protein, oral allergy syndrome (food-pollen syndrome), the pork-cat syndrome as explained earlier, and some forms of exercise-induced anaphylaxis [18-41].

It was assumed that reactions to mammalian meats would be immediate, and due to IgE directed against specific protein allergens such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) [22,27,42-46]. However, over the past few years investigators have described a new syndrome characterized by delayed reactions to mammalian meat associated with IgE antibodies directed against oligosaccharides [14,47,48]. Chung et al. first reported on IgE antibodies specific to galactose-alpha 1,3-galactose (alpha-gal), an oligosaccharide present in non-primates [49,50], when studying allergic reactions in cancer patients treated with cetuximab [51]. Commins et al. later reported on the role of oligosaccharides and IgE antibodies to alpha-gal in allergy to red meat [14,47,48]. This article will review 31 cases of delayed beef reactions from around the world [18,48,52,53], along with one case from our clinic. It summarizes the current understanding of this rare, novel, and evolving syndrome.

Historical Perspectives in the Discovery of Alpha-gal-mediated Allergy

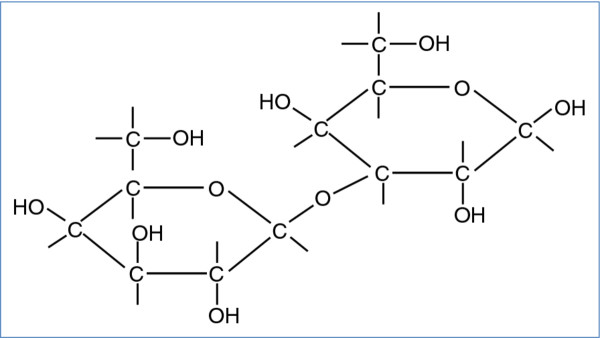

Alpha-gal (Figure 1) is an oligosaccharide found in mammalian cells of non-primates [49,50]. The alpha-gal epitope is present in beef, pork, lamb [14,47-49], and cat dander [54,55], but is absent in chicken and fish [49]. Beta-galactosyl alpha 1,3 galactosyl transferase, the enzyme needed for formation of alpha-gal, is inactivated in humans and higher mammals due to an evolutionary process. As a result, immunocompetent individuals may form IgG isotype antibodies to alpha-gal [49,56]. These antibodies contribute to immediate rejection of xenotransplants such as with "pig organs" in humans (recipients). At the same time, the high immunogenicity of alpha-gal may allow for the generation of anti-viral vaccines, as well as tumor vaccines that also carry the alpha-gal epitope [49].

Figure 1.

Structure of galactose-alpha 1,3-galactose (alpha-gal). Alpha-gal is an oligosaccharide found in mammalian cells of non-primates [49,50]. The alpha-gal epitope is present in beef, pork, lamb [14,47-49], and cat dander [54,55], and absent in chicken and fish [49]. Beta-galactosyl alpha 1,3 galactosyl transferase, the enzyme needed for formation of alpha-gal, is inactivated in humans and higher mammals [49,56].

Exposure to food allergens (including perhaps alpha-gal in mammalian meat) results in the generation of IgG antibodies from B cells and hence development of immune tolerance. In predisposed individuals, due to possible genetic/environmental factors (such as a fatty diet, or tick bites), exposure of antigen presenting cells to alpha-gal leads to Th2 activation and induction of interleukins, leading to IgE formation by B cells. This culminates in mast cell activation, eosinophilia, and the full gamut of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions characterized by urticaria, angioedema, and progression to systemic anaphylaxis in some patients [8,57,58].

Cetuximab; Introduction, Infusion reactions, and Link to Meat Allergy

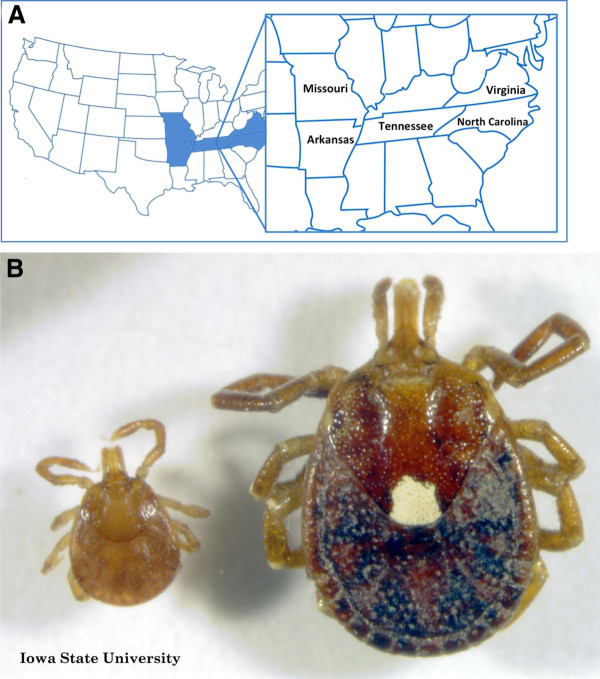

Cetuximab is a recombinant chimeric epidermal growth factor monoclonal antibody approved for treatment of metastatic colorectal and head and neck cancer [51,59-61]. Initial studies on cetuximab started in 2000, when IMC-C225, was shown to inhibit the growth of pancreatic cancer cells [62]. Further studies and clinical trials on this monoclonal antibody, later given the name cetuximab, were conducted [63-66]. It was shown that cetuximab binds to tumor cells, and is able to activate natural killer cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils to target them against these cancer cells [67]. In 2004, cetuximab was approved for the treatment of colon cancer (http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2004/ucm108244.htm) [59], and subsequently for treatment of squamous cell head and neck cancer in 2006 (http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2006/ucm108609.htm). Since 2002, cetuximab has induced severe hypersensitivity reactions [51,68-70] that have led physicians to further study the nature of these reactions, and determine the appropriate management [71-73]. In 2007 and 2008, reports showed that the infusion reactions were more prevalent in Southeastern United States [51,68] (Figure 2A). This distribution is of interest, and may be related to other factors, including diet as well as exposure to the Lone Star Tick [74] (Figure 2B). In 2008, Chung et al. identified IgE antibodies to alpha-gal in patients who developed mild to severe allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, following treatment with cetuximab [51]. Then, in 2009, Commins et al. reported on a similar geographic distribution of patients presenting with delayed allergic reaction to red meat, and studies were able to detect IgE to alpha-gal in these patients as well [48]. More patients with this interesting syndrome were further studied in Europe in 2009 and 2011 [18,52]. Figure 3 summarizes the chronological events starting with the discovery of cetuximab, the allergic reactions reported, the role of alpha-gal in these reactions, and the link to red meat allergy.

Figure 2.

Areas in USA where IgE to alpha-gal is common and the associated tick. A: Map of United States of America with highlights on the south-eastern region in which reactions to cetuximab [51], as well as seropositivity to alpha-gal in delayed red meat allergy [48], are most prevalent. B: Lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), most prevalent in southeast USA and linked to alpha-gal allergy [74-76]. Image used with permission from Iowa State University Entomology department; Credit to John VanDyk.

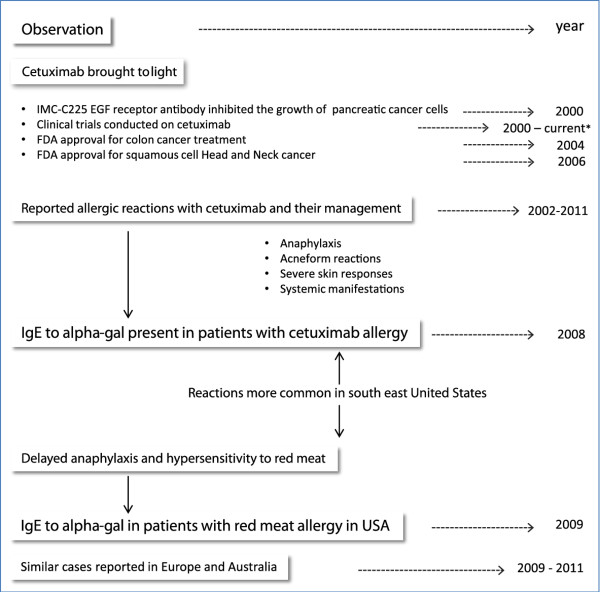

Figure 3.

The events in the understanding of cetuximab and Alpha-gal-mediated hypersensitivity. With the use of cetuximab in treatment of head and neck cancer and colorectal carcinoma, multiple infusion reactions were reported. Chung el al. in 2008 were able to identify IgE to alpha-gal directed to the Fab portion of cetuximab and was related to the allergic reactions. IgE to alpha-gal was later linked to allergic reactions to red meat in America and Europe. Information from references: [18,51,52,59-74].

The Cetuximab Hypersensitivity Syndrome

Reactions to biological agents (and most drugs) can be classified as IgE and non-IgE mediated reactions, and can present in the form of skin, pulmonary, or cardiac manifestations [77-79]. Non-IgE reactions may be secondary to cytokine release and/or tumor lysis syndrome [80-84]. In the case of cetuximab, evidence suggests that these reactions are IgE mediated and represent true anaphylaxis.

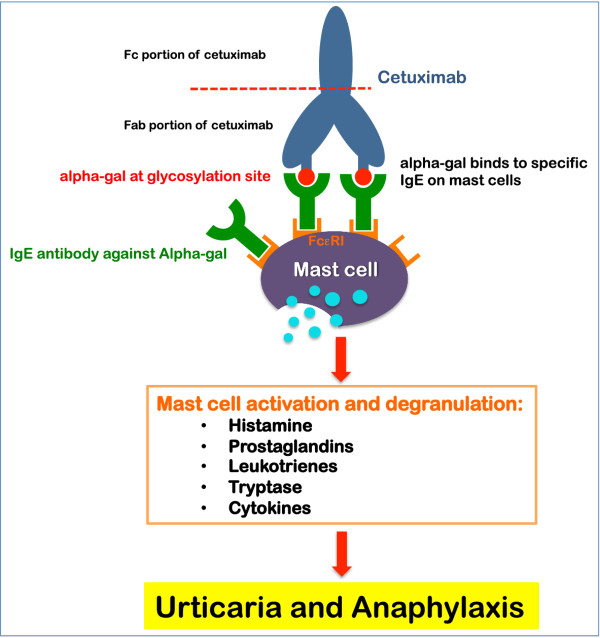

As mentioned earlier, Chung et al. identified IgE antibodies to alpha-gal in patients presenting with severe infusion reactions to cetuximab [51]. In this series, the authors reported on the presence of IgE antibodies against cetuximab in sera from four groups of patients: 76 patients treated with cetuximab in the South-Eastern United States, 72 healthy control subjects in Tennessee, 49 control subjects with cancer in California, 3 treated with cetuximab, and 341 control subjects in Boston. The authors show that 25/76 subjects treated with cetuximab in Tennessee had clinical hypersensitivity to the drug, and samples from 17 of those demonstrated IgE antibodies to cetuximab, compared to only 1/51 in those patients who did not have a hypersensitivity reaction. The IgE antibodies were also found in 15/72 control subjects in Tennessee and only in 3/49 samples in Northern California and 2/341 control samples from Boston. The studies showed that these IgE antibodies are directed against the alpha-gal component of the Fab fragment of cetuximab heavy chain (Figure 4) [51,85]. A recent study by van Bueren et al. [85] reported the presence of alpha-gal epitopes in the Fc portion of several monoclonal antibodies including infliximab, basiliximab, palivizumab, panitumumab, and cetuximab. However, only cetuximab was found to contain alpha-gal in the Fab region of the heavy chain, and interestingly, was the only drug able to bind to IgE specific to alpha-gal (Figure 4) [85]. IgE to alpha-gal failed to bind to the Fc portion of the drugs due to several factors [85]. This might explain the tolerance of some patients to panitumumab after experiencing severe reactions to cetuximab [86-88].

Figure 4.

The possible mechanism behind cetuximab induced allergies. Cetuximab is a recombinant chimeric epidermal growth factor monoclonal antibody approved for treatment of metastatic colorectal and head and neck cancer [51,59-61]. Infusion reactions with cetuximab are linked to the presence of IgE antibodies directed against the alpha-gal component of the Fab fragment of cetuximab heavy chain [51,85]. Each cetuximab molecule contains two alpha-gal epitopes that can cross-link the high affinity receptor for IgE (FcεRI) on mast cells [51] leading to mast cell activation and release of hypersensitivity mediators [57].

Each cetuximab molecule contains two alpha-gal epitopes that can cross-link the high affinity receptor for IgE (FcεRI) on mast cells [51]. IgE crosslinking of FcεRI leads to activation of mast cells and degranulation with release of hypersensitivity mediators including histamine, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, tryptase, and cytokines [57]. The possible mechanisms behind the cetuximab reactions are demonstrated in cartoon format in Figure 4.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Alpha-gal-related Meat Allergy

The clinical presentation of alpha-gal-related red meat allergy is similar to other food allergies, but has many unique characteristics (Additional file 3: Table S3). Upon presentation with suspected food allergy, history taking remains the initial tool for diagnosis [12,18]. Patients with beef allergy related to alpha-gal have symptoms that are common to other food induced hypersensitivity reactions including urticaria, dyspnea, hypotension, angioedema, or even full blown anaphylactic shock [18,48,52,53], but with the caveat that reactions occur hours after the ingestion of an incriminated food. This sometimes makes the diagnosis difficult. A detailed history including type of ingested foods, time to onset of symptoms, the geographic area of residence as well as history of tick bites, can help in achieving the diagnosis. A patient presenting from the South-Eastern United States with allergy to red meat occurring up to 3-7 hours after ingestion, and with a history of tick bites, would be suggestive of alpha-gal allergy.

In general, confirming the diagnosis of a specific food allergy has many components. Although food challenges remain the "gold standard" for definitive diagnosis [12,13], most physicians would start with basic tests including skin prick test (SPT), intradermal testing, or patch testing with the suspected allergen. In some cases where skin tests could not be performed, serum IgE antibody quantification for the suspected allergen/s is safe and easy [12], but there is high number of false positive results, and the IgE level does not necessarily correlate with the severity of the reaction [8,12]. The approach to delayed food reactions however has some caveats. A food challenge may be unnecessary if the history and serological tests are confirmatory, and may in fact be dangerous. Food challenges are best conducted in research environments and their role is yet to be defined in the delayed reactions to mammalian meats.

In the USA, Commins et al. at University of Virginia Health System are the leaders in studying delayed red meat allergy [14,47,48]. They studied 24 patients with IgE to alpha-gal [48]: 4 initially presented with hypersensitivity to beef, 15 identified from a cohort study of 243 patients, and 5 presenting from a clinic in Missouri. All 24 patients had delayed allergic reactions after ingestion of red meat. Patients were between the ages of 18 and 80 years, 14 males and 10 females, and presenting from southeast United States. In addition to IgE to alpha-gal, total IgE levels, and IgE to beef were measured in the studied cases. 22 out of 24 patients had positive (> 0.35 IU/ml) IgE to beef with variable total IgE levels. Skin testing was performed on 18 patients using both commercial and fresh beef extracts, 13 of which gave positive results. 10 patients had intradermal testing to beef and all gave positive results. Although more than 72% of patients had positive SPT to beef and 100% of tested patients had positive intradermal tests to beef, Commins reported that these reactions were not impressive when compared to the IgE to beef, and the severity of reactions they experienced [48]. Studies showed that fresh extracts of beef and pork contain more alpha-gal amounts than commercial extracts, and hence were able to produce better results [18,48]. This is no surprise as multiple reports showed that the allergenicity of beef changes with the method of processing and heat exposure [26,89-92]. The source of meat and the preparation of the extract used in SPT differ between laboratories and even countries. This indeed can attribute to the variability of results in each study. Almost 80% of the studied patients in Commins paper had no further symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions after avoidance of red meat. The others had fewer manifestations. Detailed information of the involved patients and their laboratory results is outlined in Commins and Platts-Mills original paper [48].

Seven other patients studied in Europe presented with delayed allergy to red meat, and had IgE levels positive for alpha-gal and beef [18,52]. In France, investigations on two patients showed mild SPT reactions to raw beef and pork, but significant skin reaction when tested with cetuximab, even with low concentrations [18]. Nunez et al. in Spain also reported on 5 patients with IgE antibodies specific to alpha-gal, all presenting with severe red meat allergy. All five patients tested positive for IgE to beef, pork, lamb, and rabbit. SPT with raw beef and cetuximab were positive in all five as well [52]. Other cases with similar history and presentation to alpha-gal allergy were reported, but to our knowledge testing for alpha-gal was not conducted [14,53]. Clinical presentations of cases with alpha-gal allergy and variable diagnostic tests are summarized in Additional file 4: Table S4.

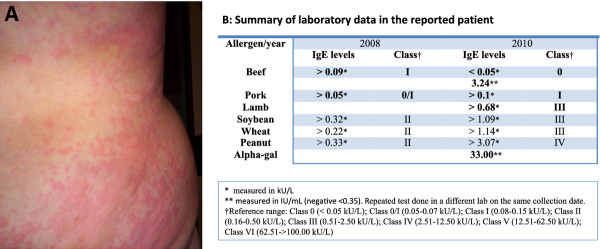

A 48-year old male patient with delayed reaction to beef presented to our clinic in East Tennessee. He experienced recurrent urticarial eruptions (Figure 5A) and dyspnea that occurred 5 to 7 hours after red meat ingestion, including beef and pork. Interestingly, the patient reported a history of tick bites 2 weeks prior to his first reaction. Initial blood work showed negative IgE levels to beef and pork, but repeated testing of the same sample was positive to beef. He also had very elevated levels of IgE specific to alpha-gal. Our patient now avoids red meat products and has not experienced any further reactions with food ingestion. Additional laboratory data and information is summarized in Additional file 4: Table S4 and Figure 5B.

Figure 5.

Urticarial eruptions (A) and laboratory data (B) in a patient with alpha-gal related red meat allergy. A 48 year-old patient presented with recurrent urticarial eruptions and dyspnea 5 to 7 hours after red meat ingestion. Patient reported history of tick bites 2 weeks prior to his first reaction. Initial workup showed negative IgE to beef and pork. SPT to beef was not performed. Repeated testing was positive to beef and alpha-gal. Patient avoids red meat products and symptoms are well controlled.

The Presumed Role of Tick Bites

Although genetic factors may predispose an individual to develop an allergic reaction to beef, Commins provided strong evidence that tick bites likely play an important role in this development [48,74]. Bites from the tick species Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick (Figure 2B)), commonly found in the south east and south central areas of the United States [75], seem to precede the hypersensitivity to alpha-gal[74]. This phenomenon suggests a role in the sensitization process.

The bite of the lone star tick is associated with the development of STARI [76] (southern tick-associated rash illness) usually typified by a large "bulls eye" skin lesion and accompanied by fever, myalgia, and arthralgia. It is important to differentiate this illness from lime disease [76]. How instrumental tick bites are in alpha-gal sensitization, and the mechanism by which this occurs is still unclear.

In a recent study, Commins and James reviewed three patients with known IgE levels to alpha-gal, and documented a significant elevation in these levels after exposure to tick bites [74]. A strong correlation between antibodies to Amblyomma americanum and those to alpha-gal was present. Additionally, they screened several individuals and found that most of those whose serum tested positive for alpha-gal, provided a history of tick bites, irrespective of whether they had developed meat reactions [74].

In other areas of the world, history of tick bites (different than Amblyomma americanum) is associated with development of meat-induced allergy [52,53]. In a study by Van Nunen in Sydney Australia [53], almost all patients (24/25) presenting with the red meat allergy gave a history of tick bites. The suspected tick is Ixodes holocyclus [53], mainly distributed in southeastern Australia [93], and is associated with severe paralysis and cardiovascular problems [94-98]. In Spain 4 of 5 patients with meat allergy expressed history of tick bites prior to the reaction [52]. Although no documented proof of the tick species related to these reactions, the tick common in that area in Spain (north-western) is Ixodes ricinus [52]. Cases with reported history of tick bites and the suspected tick are summarized in Additional file 4: Table S4.

Relationship to Dietary Fat and the Presumed Mechanism of Delay

Another interesting relationship between the areas where alpha-gal allergy is reported in the United States is the obesity rate. The recently reported obesity rates from the Center of Disease Control and Prevention for Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina were higher than those in California and Massachusetts, areas where alpha-gal allergy is uncommon [51]. This raises the question of whether high-fat consumption in diet can be an additional reason for geographical alpha-gal IgE distribution.

The mechanism behind the delayed presentation of symptoms after red meat ingestion in patients with IgE to alpha-gal is still undetermined. A possible explanation suggested by Commins et al. proposes this delay to the time needed for red meat to be digested and presented to circulation [48]. Lipid and glycolipid complexes may mediate delayed absorption and presentation of alpha-gal to antigen presenting cells [14,48]. It only takes about 2 hours for glucose to reach its maximum level in the plasma after a meal. In contrast, it takes about 4-5 hours for dietary triglycerides to reach their peak in circulation [99,100]. In the postprandial state, dietary triglycerides are packaged in the small intestine into very-low density lipoproteins (VLDLs) and chylomicrons, two of the largest lipoprotein particles [101]. Due to their large size, VLDLs (30-80 nm in diameter) and chylomicrons (> 80 nm in diameter) are driven to enter the lymphatic circulation before being emptied into the venous circulation via the subclavian vein. Soluble dietary nutrients, such as amino acids and glucose, directly enter the venous circulation via the superior mesenteric vein/hepatic portal vein. On the other hand, insoluble dietary nutrients including long-chain triglycerides, cholesterol, and lipid-soluble vitamins are packaged by the small intestine into VLDLs and chylomicrons for transport through the lymphatic circulation [102].

Alpha-gal is known to be abundantly present on glycolipids and glycoproteins of non-primate mammals, including the red meat from beef, pork, and lamb [49,50]. Glycolipids and glycoproteins need to be digested in the intestinal lumen before they can be taken up by enterocytes. These alpha-gal-containing digestion products are likely lipid soluble and expected to be transported in VLDLs and/or chylomicrons [48]. The delay of both the allergic reaction and the peak of dietary triglycerides in the circulation, suggests that the allergen from red meat is transported together with dietary triglycerides [48]. Since lipoproteins are made out of a phospholipid monolayer, the alpha-gal containing glycolipids may be inserted into the phospholipid monolayer with the carbohydrate group facing towards the exterior. The "exposed" orientation, rather than "buried", should be optimal for inducing an allergic reaction. Studies should be aimed towards determining the presence of alpha-gal in intestinal lipoproteins. The presence of alpha-gal should only be detected in VLDL/chylomicron fractions from ingestion of red meat from non-primate mammals, and not from other dietary sources, e.g., chicken and vegetarian meals.

Food Anaphylaxis and Hypersensitivity Reaction Management

The delay in appearance of symptoms related to alpha-gal allergy makes it difficult for patients and physicians to identify the trigger [14]. If such an event were to occur, the patient would be advised to go to the nearest hospital or emergency room. Once the diagnosis is suspected on the basis of history and epidemiological setting, appropriate testing should be done to confirm the diagnosis. Following this, preventive measures include avoidance of red meat and the use of injectable epinephrine [40,48,58,103]. Education and instruction on use of injectable epinephrine is vital. Acute management of patients presenting with anaphylaxis, including those related to alpha-gal, is summarized in Additional file 5: Table S5.

Conclusion

Alpha-gal allergy is a new and evolving syndrome related to oligosaccharides, rather than protein, in red meat. The IgE mediated response to alpha-gal tends to occur several hours after antigen exposure. This unique presentation constitutes a challenge to both patients and physicians, making detailed history very important if suspected. Reactions to cetuximab seem to be mediated by an identical mechanism. More studies are required about this unique syndrome, including an explanation for the mechanism of delay in presentation and the possible roles obesity and tick bites play in the predisposition for the disorder.

Abbreviations

Alpha-gal: Galactose-alpha 1,3-galactose; BSA: Bovine serum albumin; SPT: Skin-prick test; FEIA: Fluorescence enzyme immunoassay; VLDLs: Very-low density lipoproteins; FDEIA: Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis; OSA: Ovine serum albumin.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

HS reviewed the literature, generated references, organized the manuscript, and illustrated the figures. SE assisted with manuscript review and corrections. AN assisted in section involving mechanism of delay and role of chylomicrons. SA assisted in section involving mechanism of delay and role of chylomicrons. GK organized the manuscript, edited figures and tables, assisted in discussion, generated references, and participated in the editing and final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Table 1. Common food allergens.

Table 2. Meat Allergy Types and Features.

Table 3. Diagnostic features of alpha-gal-related food allergy.

Table 4. Summary of reported cases with alpha-gal allergy in USA and Europe.

Table 5. Acute Management and Prevention of Anaphylaxis*.

Contributor Information

Hana Saleh, Email: saleh.hana@gmail.com.

Scott Embry, Email: arlo618@yahoo.com.

Andromeda Nauli, Email: naulia@mail.etsu.edu.

Seif Atyia, Email: seifatyia@yahoo.com.

Guha Krishnaswamy, Email: krishnas@mail.etsu.edu.

References

- Lieberman JA, Sicherer SH. Quality of life in food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(3):236–242. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283464cf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrol DJ. Food allergy: an overdiagnosed but underappreciated problem. South Med J. 2011;104(5):308. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318214f7dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter C, Arshad SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(2):327–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.011. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce JA, Assa'a A, Burks AW. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: summary of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel Report. Nutrition. 2011;27(2):253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 Suppl):S1–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koplin JJ, Martin PE, Allen KJ. An update on epidemiology of anaphylaxis in children and adults. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(5):492–496. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834a41a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicherer SH. Food allergy. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(5):683–696. doi: 10.1002/msj.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Vadas P. Anaphylaxis: mechanisms and management. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(7):923–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keet C. Recognition and management of food-induced anaphylaxis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(2):377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.006. x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvinen KM. Food-induced anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(3):255–261. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834694d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food allergies and food intolerances. Both are on the rise--and it's important to know the difference. Harv Womens Health Watch. 2011;18(9):4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siles RI, Hsieh FH. Allergy blood testing: a practical guide for clinicians. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78(9):585–592. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78a.11023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski K, Boxer RW. Food allergies: detection and management. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(12):1678–1686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Allergenicity of carbohydrates and their role in anaphylactic events. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2010;10(1):29–33. doi: 10.1007/s11882-009-0079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain Z, Schwartz RA. Peanut allergy: an increasingly common life-threatening disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;66(1):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MH, Wong WH, Heine RG. et al. Early clinical predictors of remission of peanut allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(3):731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the United States determined by means of a random digit dial telephone survey: a 5-year follow-up study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(6):1203–1207. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(03)02026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquenet S, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Bihain BE. Mammalian meat-induced anaphylaxis: clinical relevance of anti-galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose IgE confirmed by means of skin tests to cetuximab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(3):603–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orhan F, Sekerel BE. Beef allergy: a review of 12 cases. Allergy. 2003;58(2):127–131. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theler B, Brockow K, Ballmer-Weber BK. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of meat allergy in Switzerland and Southern Germany. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(17-18):264–270. doi: 10.4414/smw.2009.12603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, An S, Kim JE. et al. Beef-induced anaphylaxis confirmed by the basophil activation test. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2(3):206–208. doi: 10.4168/aair.2010.2.3.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes MM, Palacios R, Garces MM, Caballero ML, Moneo I. Isolation and characterization of a heat-resistant beef allergen: myoglobin. Allergy. 2004;59(3):327–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamikoglu B. Beef, pork, and milk allergy (cross reactivity with each other and pet allergies) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(4):534–537. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigenmann PA. Anaphylaxis to cow's milk and beef meat proteins. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89(6 Suppl 1):61–64. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli A, De CA, Corvo M, Restani P, Fiocchi A. Beef allergy in children with cow's milk allergy; cow's milk allergy in children with beef allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89(6 Suppl 1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werfel SJ, Cooke SK, Sampson HA. Clinical reactivity to beef in children allergic to cow's milk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(3):293–300. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(97)70045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes AV, Sanchez MI, Perez MA, Baeza ML, de Barrio FM. Allergy to mammal's meat in adult life: immunologic and follow-up study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2005;15(3):228–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restani P, Beretta B, Fiocchi A, Ballabio C, Galli CL. Cross-reactivity between mammalian proteins. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89(6 Suppl 1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano J, Caballero ML, Rodriguez-Perez R. et al. Sensitization to serum albumins in children allergic to cow's milk and epithelia. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(6):503–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restani P, Ballabio C, Tripodi S, Fiocchi A. Meat allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9(3):265–269. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32832aef3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San-Juan S, Lezaun A, Caballero ML, Moneo I. Occupational allergy to raw beef due to cross-reactivity with dog epithelium. Allergy. 2005;60(6):839–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savi E, Rossi A, Incorvaia C. Cat-pork syndrome: a case report with a thee years follow-up. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;38(10):366–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouet M, Sabbah A, Le SJ. et al. Fatal anaphylaxis after eating wild boar meat in a patient with pork-cat syndrome. Allerg Immunol (Paris) 2001;33(4):163–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier P, Basset-Stheme S, Sainte-Laudy J. [Pork-cat syndrome in a 16-month-old child] Allerg Immunol (Paris) 1999;31(2):60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouet M, Sabbah A. The pork/cat syndrome or crossed reactivity between cat epithelia and pork meat. Monogr Allergy. 1996;32:164–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouet M, Lauret MG, Sabbah A. [The pork-cat syndrome: effect of sensitization to cats on sensitization to pork meat. Apropos of a case] Allerg Immunol (Paris) 1994;26(8):305–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouet M, Lauret MG, Sabbah A. [The pork-cat syndrome: effect of sensitivity to cats on that to pork meat. Based on an observation] Allerg Immunol (Paris) 1994;26(7):261–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah A, Rousseau C, Lauret MG, Drouet M. The pork-cat syndrome: RAST inhibition test with Feld One. Allerg Immunol (Paris) 1994;26(7):259–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouet M, Boutet S, Lauret MG. et al. The pork-cat syndrome or crossed allergy between pork meat and cat epithelia (1) Allerg Immunol (Paris) 1994;26(5):166–168. 171-172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CW, Guha B, Krishnaswamy G. Exercise-induced anaphylaxis: a serious but preventable disorder. Phys Sportsmed. 2008;36(1):87–94. doi: 10.3810/psm.2008.12.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann T, Schopf P, Rueff F, Przybilla B. Exertion-induced anaphylaxis after eating pork and beef. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1999;124(15):456–458. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocchi A, Restani P, Riva E. Beef allergy in children. Nutrition. 2000;16(6):454–457. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocchi A, Restani P, Bouygue GR, Martelli A. Beef allergy in adults and children. Allergy. 2005;60(1):126. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori K, Masuda K, Kawarai S. et al. Identification of bovine serum albumin as an IgE-reactive beef component in a dog with food hypersensitivity against beef. J Vet Med Sci. 2007;69(8):865–867. doi: 10.1292/jvms.69.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han GD, Matsuno M, Ito G, Ikeucht Y, Suzuki A. Meat allergy: investigation of potential allergenic proteins in beef. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64(9):1887–1895. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe S, Shibata R, Nishimura T. Hypoallergenic and T cell reactive analogue peptides of bovine serum albumin, the major beef allergen. Mol Immunol. 2004;41(9):885–890. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Anaphylaxis syndromes related to a new mammalian cross-reactive carbohydrate determinant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(4):652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commins SP, Satinover SM, Hosen J. et al. Delayed anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria after consumption of red meat in patients with IgE antibodies specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(2):426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macher BA, Galili U. The Galalpha1, 3Galbeta1, 4GlcNAc-R (alpha-Gal) epitope: a carbohydrate of unique evolution and clinical relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780(2):75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiane Y, Aghayan M, Emonard H. et al. Galactose alpha 1-3 galactose and anti-alpha galactose antibody in normal and pathological pregnancies. Placenta. 1992;13(5):475–487. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(92)90053-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E. et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1109–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez R, Carballada F, Gonzalez-Quintela A. et al. Delayed mammalian meat-induced anaphylaxis due to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose in 5 European patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(5):1122–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nunen SA, O'Connor KS, Clarke LR, Boyle RX, Fernando SL. An association between tick bite reactions and red meat allergy in humans. Med J Aust. 2009;190(9):510–511. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronlund H, Adedoyin J, Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA, van HM. The carbohydrate galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose is a major IgE-binding epitope on cat IgA. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1189–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkestal K, Sibanda E, Thors C. et al. Impaired allergy diagnostics among parasite-infected patients caused by IgE antibodies to the carbohydrate epitope galactose-alpha 1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(4):1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadeh RM, Jarvis GA, Zhou P, Cotleur AC, Griffiss JM. Bacterial enzymes can add galactose alpha 1,3 to human erythrocytes and creates a senescence-associated epitope. Infect Immun. 1996;64(2):528–534. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.528-534.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan BQ, Kemp SF. Pathophysiology of anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(4):319–325. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283481ab6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaswamy G, Ajitawi O, Chi DS. The human mast cell: an overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;315:13–34. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-967-2:013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetuximab approved by FDA for treatment of head and neck squamous cell cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5(4):340–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SF. Cetuximab: an epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Clin Ther. 2005;27(6):684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blick SK, Scott LJ. Cetuximab: a review of its use in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and metastatic colorectal cancer. Drugs. 2007;67(17):2585–2607. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overholser JP, Prewett MC, Hooper AT, Waksal HW, Hicklin DJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor blockade by antibody IMC-C225 inhibits growth of a human pancreatic carcinoma xenograft in nude mice. Cancer. 2000;89(1):74–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000701)89:1<74::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J, Pfister D, Cooper MR. et al. Phase I studies of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor chimeric antibody C225 alone and in combination with cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):904–914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maubec E, Petrow P, Scheer-Senyarich I. et al. Phase II study of cetuximab as first-line single-drug therapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3419–3426. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltz LB, Meropol NJ, Loehrer PJ Sr. et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with refractory colorectal cancer that expresses the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(7):1201–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argiris A, Feinstein TM, Wang L, Invest New Drugs: phase I and pharmacokinetic study of dasatinib and cetuximab in patients with advanced solid malignancies. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patel D, Guo X, Ng S. et al. IgG isotype, glycosylation, and EGFR expression determine the induction of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in vitro by cetuximab. Hum Antibodies. 2010;19(4):89–99. doi: 10.3233/HAB-2010-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neil BH, Allen R, Spigel DR. et al. High incidence of cetuximab-related infusion reactions in Tennessee and North Carolina and the association with atopic history. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3644–3648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DD, Goldberg RM. Cetuximab-associated infusion reactions: pathology and management. Oncology (Williston Park) 2006;20(11):1373–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CH, O'Neil BH. Infusion reactions to monoclonal antibodies for solid tumors: immunologic mechanisms and risk factors. Oncology (Williston Park) 2009;23(2 Suppl 1):14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George TJ Jr, Laplant KD, Walden EO. et al. Managing cetuximab hypersensitivity-infusion reactions: incidence, risk factors, prevention, and retreatment. J Support Oncol. 2010;8(2):72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CH. Managing premedications and the risk for reactions to infusional monoclonal antibody therapy. Oncologist. 2008;13(6):725–732. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saif MW, Syrigos KI, Hotchkiss S. et al. Successful desensitization with cetuximab after an infusion reaction to panitumumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;65(1):107–112. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commins SP, James HR, Kelly LA. et al. The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1286–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalaire KC, Kim TK, Garcia-Rodriguez H, Mulenga A. Amblyomma americanum (L.) (Acari: Ixodidae) tick salivary gland serine protease inhibitor (serpin) 6 is secreted into tick saliva during tick feeding. J Exp Biol. 2011;214(Pt 4):665–673. doi: 10.1242/jeb.052076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters EJ, Grigery CN, Masters RW. STARI, or Masters disease: Lone Star tick-vectored Lyme-like illness. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22(2):361–376. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.010. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bircher AJ, Scherer HK. Drug hypersensitivity reactions: Inconsistency in the use of the classification of immediate and nonimmediate reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;129(1):263–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thien FC. 3. Drug hypersensitivity. Med J Aust. 2006;185(6):333–338. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruchalla RS. 10. Drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(2 Suppl):S548–S559. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Hendrickson AW, Moynihan TJ. Oncologic emergencies: Pathophysiology, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011. in press [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Salit RB, Bishop MR. The evolving world of tumor lysis syndrome. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25(4):378–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard SC, Jones DP, Pui CH. The tumor lysis syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1844–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaud A, Granel F, Waton J, Poreaux C. How to manage hypersensitivity reactions to biological agents? Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21(5):667–674. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy G, Lukacs K, Sziray A. et al. Adverse events during biological therapy-focusing on dermatological side-effects. Orv Hetil. 2011;152(6):212–220. doi: 10.1556/OH.2011.28987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bueren JJ, Rispens T, Verploegen S. et al. Anti-galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose IgE from allergic patients does not bind alpha-galactosylated glycans on intact therapeutic antibody Fc domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):574–576. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heun J, Holen K. Treatment with panitumumab after a severe infusion reaction to cetuximab in a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer: a case report. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2007;6(7):529–531. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2007.n.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen DL, Pfeiffer P, Jensen BV. Six cases of treatment with panitumumab in patients with severe hypersensitivity reactions to cetuximab. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(4):798. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power DG, Shah MA, Asmis TR, Garcia JJ, Kemeny NE. Safety and efficacy of panitumumab following cetuximab: retrospective review of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. Invest New Drugs. 2010;28(3):353–360. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9268-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restani P, Ballabio C, Cattaneo A. et al. Characterization of bovine serum albumin epitopes and their role in allergic reactions. Allergy. 2004;59(Suppl 78):21–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocchi A, Restani P, Riva E. et al. Meat allergy: II-Effects of food processing and enzymatic digestion on the allergenicity of bovine and ovine meats. J Am Coll Nutr. 1995;14(3):245–250. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1995.10718503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocchi A, Restani P, Riva E. et al. Heat treatment modifies the allergenicity of beef and bovine serum albumin. Allergy. 1998;53(8):798–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb03977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han GD, Matsuno M, Ikeuchi Y, Suzuki A. Effects of heat and high-pressure treatments on antigenicity of beef extract. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66(1):202–205. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Beveridge I, Chilton NB, Andrews RH. Distributions of the paralysis ticks Ixodes cornuatus and Ixodes holocyclus in south-eastern Australia. Aust Vet J. 2007;85(10):420–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2007.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Mendelin S, Craig SB, Hall RA. et al. Tick paralysis in Australia caused by Ixodes holocyclus Neumann. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2011;105(2):95–106. doi: 10.1179/136485911X12899838413628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell F, Atwell R, Fenning A, Hoey A, Brown L. Cardiovascular effects of the toxin(s) of the Australian paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus, in the rat. Toxicon. 2004;43(7):743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FE, Atwell RB. Long QT syndrome in dogs with tick toxicity (Ixodes holocyclus) Aust Vet J. 2002;80(10):611–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2002.tb10963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MK. Massive tick (Ixodes holocyclus) infestation with delayed facial-nerve palsy. Med J Aust. 2002;176(6):264–265. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grattan-Smith PJ, Morris JG, Johnston HM. et al. Clinical and neurophysiological features of tick paralysis. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 11):1975–1987. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.11.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drover VA, Ajmal M, Nassir F. et al. CD36 deficiency impairs intestinal lipid secretion and clearance of chylomicrons from the blood. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1290–1297. doi: 10.1172/JCI21514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauli AM, Zheng S, Yang Q. et al. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase release is not associated with chylomicron formation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284(4):G583–G587. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00482.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauli AM, Nassir F, Zheng S. et al. CD36 is important for chylomicron formation and secretion and may mediate cholesterol uptake in the proximal intestine. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(4):1197–1207. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CJ, Trevaskis NL, Charman WN. Lipids and lipid-based formulations: optimizing the oral delivery of lipophilic drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(3):231–248. doi: 10.1038/nrd2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CW, Krishnaswamy N, Johnston C, Krishnaswamy G. Severe asthma and the omalizumab option. Clin Mol Allergy. 2008;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1. Common food allergens.

Table 2. Meat Allergy Types and Features.

Table 3. Diagnostic features of alpha-gal-related food allergy.

Table 4. Summary of reported cases with alpha-gal allergy in USA and Europe.

Table 5. Acute Management and Prevention of Anaphylaxis*.