Abstract

In a complex multicellular organism, different cell types engage in specialist functions, and as a result, the secretory output of cells and tissues varies widely. Whereas some quiescent cell types secrete minor amounts of proteins, tissues like the pancreas, producing insulin and other hormones, and mature B cells, producing antibodies, place a great demand on their endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Our understanding of how protein secretion in general is controlled in the ER is now quite sophisticated. However, there remain gaps in our knowledge, particularly when applying insight gained from model systems to the more complex situations found in vivo. This article describes recent advances in our understanding of the ER and its role in preparing proteins for secretion, with an emphasis on glycoprotein quality control and pathways of disulfide bond formation.

About 11% of full-length ORFs in the human genome encode soluble secretory proteins. Orderly secretion depends on proper targeting and translocation into the ER, folding, glycosylation, disulfide bond formation, and ER exit.

How a cell controls its complex output and ensures that only properly folded and functional proteins reach their correct destination is a question of considerable importance in biology. It has been calculated that the products of 11% of the approximately 25,000 predicted human full-length open reading frames (ORFs) are soluble secretory proteins, with a further 20% being single-pass or multi-pass transmembrane proteins that get targeted to the ER (Kanapin et al. 2003). Many of these proteins can also be alternatively spliced, adding a further layer of complexity (Carninci et al. 2005). To ensure orderly ER exit, protein secretion from the ER is determined by several factors. These include targeting of the nascent protein to the ER by the ribosome, the translocation of the protein into the ER, the provision of sugars for glycoproteins, the folding and quality control of the protein, the availability of cofactors (particularly calcium), and the appropriate formation of disulfide bonds (Braakman and Bulleid 2011). Some proteins require assembly into complexes, and provision of lipids for ER membranes and the regulation of cholesterol content are also important considerations. Here, the focus is on recent advances in our understanding of the glycosylation machinery, the provision of disulfide bonds, and the ER exit strategies used by proteins to ensure their efficient secretion from the ER (Fig. 1).

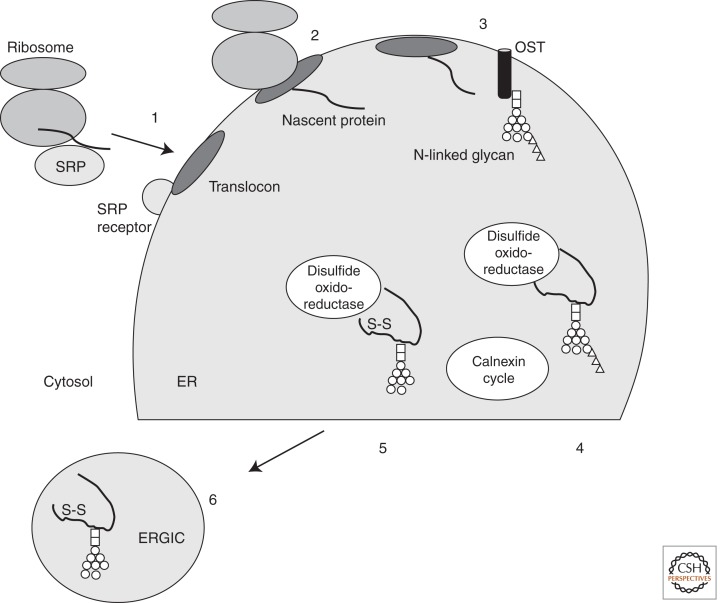

Figure 1.

Overview of protein targeting to the ER and glycoprotein quality control. Six key points in the fidelity of protein secretion are illustrated. (1) Correct targeting of the glycoprotein to the ER as it emerges from the translocon. This is mediated by the signal recognition particle (SRP) and its receptor, which helps position the emerging protein at the translocon. (2) Translocation of the (glyco)protein into the ER by the translocon. (3) Addition of N-glycans to Asn residues of glycoproteins by oligosaccharyl transferase (OST). (4) Correct folding and quality control by the calnexin cycle. (5) Introduction/correction of disulfide bonds by protein disulfide isomerases/oxidoreductases. (6) Directing glycoproteins into ER exit sites followed by packaging into appropriate compartments, for example, the ER Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC). Note that protein folding and disulfide bond formation happen rapidly after the nascent protein emerges from the translocon. (S–S) Disulfide bond; (□) N-Acetyl glucosamine; (○) mannose; (▵) glucose.

TARGETING OF PROTEINS TO THE ER

In eukaryotic cells, most secreted proteins are cotranslationally translocated from ribosomes into the rough ER. However, some proteins, particularly small polypeptides or proteins with “weak” signal sequences, can access the ER posttranslationally (Ng et al. 1996; Shao and Hegde 2011). The cotranslational targeting of secreted proteins to the ER is achieved by an amino-terminal signal sequence of 16–30 amino acids. Signal sequences are quite variable, but generally have 6 to 12 hydrophobic amino acids flanked by one or more positively charged residues. As protein synthesis begins, the signal sequence is recognized by a signal recognition particle (SRP) (Saraogi and Shan 2011). SRP is composed of six proteins (P9/P14, P68/P72, P19, and P54) and a 300-nucleotide RNA scaffold. The P54 subunit of SRP is primarily responsible for binding to the signal sequence. Translation is temporarily halted until SRP54 interacts with the α-subunit of an SRP receptor that is embedded in the ER membrane through its β-subunit. Elongation arrest was first noted in one of Walter and Blobel’s pioneering studies, in which they analyzed secretory protein synthesis using microsomal membranes in vitro (Walter and Blobel 1981). Further analysis and binding studies showed that the SRP9 and SRP14 proteins bind to the Alu domain (a repetitive element) of the SRP RNA as a heterodimer and are required for elongation arrest (Siegel and Walter 1986; Strub et al. 1991). Particles reconstituted with a carboxy-terminal truncation of SRP14 are unable to arrest properly, despite having normal targeting and ribosome-binding capabilities (Thomas et al. 1997; Mason et al. 2000). The observation that changes in SRP RNA tertiary structure occurred upon binding to truncated SRP9/14 led to the proposal that RNA structural features were involved in mediating translation arrest (Thomas et al. 1997). A positively charged patch of predominantly lysine residues was shown subsequently to be essential for mediating the interaction between SRP14 and the SRP RNA (Mary et al. 2010). An impressive cryo-electron microscopy study of a mammalian SRP bound to a ribosome with a signal sequence has revealed the arrangement of these components in an arrested state. In this structure, the Alu domain of the SRP RNA is positioned in the elongation-factor-binding site to bring about translational arrest by direct competition (Halic et al. 2004).

Why translational arrest should be needed during secretory protein synthesis has been food for thought for many years. In 2008, Strub’s group showed that the amount of SRP receptor at the ER membrane was a major limiting factor in determining translation rates (Lakkaraju et al. 2008). Thus translational pausing is necessary because it helps to keep nascent proteins translocation competent, until an SRP receptor becomes available for docking, hence preventing secretory-pathway proteins from being synthesized in the wrong compartment. Further studies will be needed to determine exactly how nascent chain length influences targeting, to explain the molecular sequence of events that lead to resumption of translation upon SRP receptor engagement, and to explain how translationally paused transcripts avoid mRNA degradation by RNA quality-control mechanisms present in the cytosol (Becker et al. 2011).

After the ribosomal/nascent protein/SRP complex has docked to the SRP receptor, GTP hydrolysis releases SRP for another round of nascent polypeptide recruitment. Structural details of the interaction between the eukaryotic SRP, the SRP receptor, and the signal sequence are still awaited, but several structures of bacterial homologs involved in the translocation of polypeptides across their plasma membrane have been solved. For example, the heterodimeric structure of the GTPase domains of Ffh (a bacterial SRP54 homolog) and FtsY (a bacterial SRP receptor α-subunit homolog) is stabilized by the binding of two GTP molecules. This structure reveals how allosteric activation of the two proteins is coordinated (Focia et al. 2004). More recently, a full-length Ffh:FtsY complex in the pre-GTP hydrolysis state (cocrystallized with the GTP analog GMPPCP) has been solved to 3.9 Å (Ataide et al. 2011). This work suggests that a large-scale repositioning event occurs to hand over the signal sequence from the M (methionine-rich) domain of SRP54 (Ffh) to the translocon. It has proved difficult to obtain structures of SRP54 in combination with a signal sequence, but an elegant approach using an Ffh-signal sequence fusion protein has allowed a 3.5 Å crystal structure to be determined from dimers of the fusion protein (Janda et al. 2010). The structure is consistent with previous biochemical experiments, showing that the signal peptide interacts with the M domain of Ffh and that hydrophobic residues in the core are necessary for binding. Further studies using a range of different signal peptides should help explain how Ffh, and ultimately SRP54, can maintain selectivity while tolerating diversity in signal peptide length and sequence.

The docking of SRP to the SRP receptor positions the 60S subunit of the ribosome above the translocon. The translocon is a proteinaceous channel that translocates the nascent polypeptide chain into the ER lumen, and in mammals the translocon is composed of three principal subunits—Sec61α, β, and γ. The translocon is gated on the luminal side by the ER chaperone BiP (grp78), which helps to preserve the barrier function of the ER membrane (Sanders et al. 1992; Alder et al. 2005). The translocon is also associated with signal peptidase, which removes signal peptides posttranslationally from newly synthesized proteins, as the protein enters the ER lumen (Jackson and Blobel 1977). Several additional proteins assist the translocon, including translocating-chain-associated protein (TRAM), translocon-associating protein (TRAP), and RAMP4 (ribosome-associated membrane protein). You are referred to recent reviews for more detail regarding the function and regulation of the translocon (Osborne et al. 2005; Mandon et al. 2009; Park and Rapoport 2012).

THE PROVISION OF GLYCANS

A limiting step in the secretion of glycoproteins is the addition of sugars (Fig. 2). For N-linked glycosylation, this involves building a branching chain of glucose (Glc) and mannose (Man) sugars onto a “stem” of N-acetylglucosamine (NAc). The process of assembling the sugar donor starts in the cytosol rather than the ER. Dolichol (an isoprenylated hydrocarbon with a reactive alcohol group) acts as a carrier lipid that receives two GlcNAc moieties from UDP-GlcNAc and five mannose residues from GDP-mannose. The first GlcNAc residue is linked to dolichol by a high-energy pyrophosphate that can ultimately be transferred to the asparagine side chain of the accepting glycoprotein in the ER. Once the initial synthesis of the dolichol phosphate backbone has been achieved in the cytosol, the entire lipid intermediate, Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichol, must be translocated from the cytosolic face to the luminal face of the ER membrane. The identity of the Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichol “flippase” is still debated. Rft1, an essential ER membrane protein in yeast, was proposed to be the responsible Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichol translocator in 2002 (Helenius et al. 2002). The investigators showed that yeast with a defective RFT1 gene hypoglycosylated the model protein carboxypeptidase Y and accumulated Man(5)GlcNAc(2) precursors, whereas O-mannosylation of chitinase was unaffected. The Rft1 protein fits the bill as a candidate “flippase” because it resides in the ER, spanning the membrane multiple times, and is conserved in eukaryotes that synthesize N-linked sugars. A key role for Rft1 in glycoprotein synthesis is supported by clinical studies, namely, that mutations in the human RFT1 gene lead to diseases of N-glycosylation. Patients present with severe developmental defects, have abnormal glycoprotein profiles on iso-electric focusing gels, and accumulate dolichol-linked Man(5)GlcNAc(2) precursors, with low levels of dolichol-linked Glc(3)Man(9)GlcNAc(2) (Haeuptle et al. 2008). However, the assertion that Rft1 is a stand-alone translocator has been questioned by Mennon and colleagues, who were unable to detect “flippase” activity of the protein when reconstituted vesicles were subjected to in vitro flipping experiments (Frank et al. 2008). Sanyal and Menon (2009) reconstituted “flippase” activity in proteoliposomes and established a tritiated substrate assay to show that the process was ATP dependent and required a protein that sediments at 4S, with high specificity for Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichol. However, it remains possible that the conditions used to prepare the membranes for these in vitro experiments lead to loss of activity of Rft1 or other important translocator components.

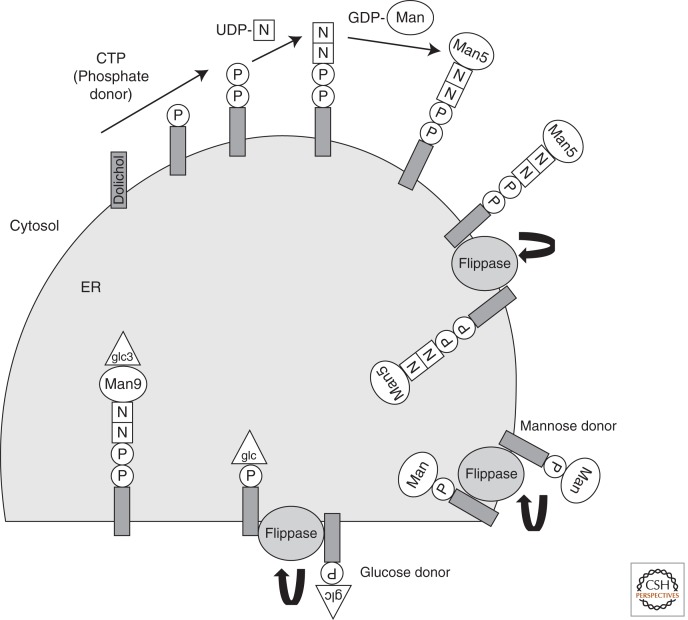

Figure 2.

The N-linked glycosylation pathway. N-linked glycosylation begins in the cytosol. Phosphate (P) from CTP is used to charge dolichol in the lipid bilayer. Dolichol phosphate receives two N-acetyl glucosamine moieties (N) from UDP-N-acetyl glucosamine. Five GDP-mannose (Man) residues are added sequentially before the sugar donor is translocated across the ER membrane by the “flippase.” In the ER lumen, four additional mannose and three glucose residues are added to yield a dolichol-linked Glc(3)Man(9)GlcNAc(2) structure that is transferred to an Asn residue of a nascent glycoprotein by OST. The identity of the “flippases” that translocate Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-P-P-dolichol, Man-P-dolichol, and Glc-P-dolichol are debated (see text for details). (□) N-Acetyl glucosamine; (○) mannose; (▵) glucose.

Once in the ER, the oligosaccharide donor Glc(3)Man(9)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichol is synthesized from Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichol by the sequential addition of four mannose and three glucose residues from dolichol-P-mannose and dolichol-P-glucose. How dolichol-P-glucose and dolichol-P-mannose are flipped from the cytosolic face to the ER side of the membrane is also not known. The protein responsible for dolichol-P-mannose transfer can be distinguished biochemically from the “flippase” that translocates Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichol (Sanyal and Menon 2010). Because phospholipid synthesis occurs in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the ER and “flip-flop” of phospholipids is required to equilibrate the bilayer, members of the phospholipid scramblase (“flippase”) family might be potential candidates for this activity. A combination of in vitro studies, genetics, cell biology, and the development of robust reporters and substrates is likely to be needed to unambiguously identify the sugar-precursor “flippases” involved in the N-glycosylation pathway.

Oligosaccharide transferase (OST) is a multi-subunit protein responsible for transferring the dolichol-linked oligosaccharide to an asparagine residue on an acceptor protein as it enters the ER through the translocon (Dempski and Imperiali 2002). In yeast, five OST subunits are essential: Nlt1p/Ost1p (Ribophorin I in mammals), Ost2p (DAD1), Stt3p, Swp1p (Ribophorin II), and Wbp1p (OST48). A major step forward in understanding OST function has come with the arrival of an X-ray structure of a bacterial periplasmic oligosaccharyl transferase called PglB (Lizak et al. 2011). The active STT3 subunit of Campylobacter lari PglB has two large amino-terminal loops that reach into the periplasm and contain residues required for peptide binding and catalysis. The peptide-binding cleft is formed by both a membrane-binding and a periplasmic domain and sits opposite the catalytic site and the lipid donor-binding site. This arrangement enables the enzyme to accommodate both the lipid and the acceptor protein. The specificity of OST for serine or threonine is explained by the positioning of a Trp-Trp-Asp motif next to the Asn-X-Ser/Thr acceptor sequence. Higher-resolution structures, coupled with further examples of client and product cocrystals, will undoubtedly shed more light on the OST catalytic cycle (Gilmore 2011). It will also be important to decipher the molecular details of how and why the OST complex assembles with different accessory proteins, for example, in response to changes in secretory demand, nutrient availability (Kelleher et al. 2003), and client delivery (Wilson et al. 2008).

THE CALNEXIN/CALRETICULIN CYCLE

One of the landmark developments in the field of glycoprotein folding was the discovery of the calnexin cycle, in which two of the three terminal glucose residues of N-linked glycoproteins are sequentially removed by ER glucosidases (Parodi 2000). Glucose trimming allows monoglucosylated oligosaccharides to bind to the ER lectin-like chaperones, calnexin (membrane bound) and calreticulin (soluble). In collaboration with ERp57, a protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (Zapun et al. 1998), the glycoprotein client is subjected to repeated cycles of folding until a native structure is reached. Glucose trimming by glucosidases competes with glucose addition by glucosyl transferase (GT; also known as UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase 1) until the terminal glucose is removed and the protein is properly folded. In this state, the client no longer has affinity for calnexin/calreticulin or GT (Zapun et al. 1997; Ritter and Helenius 2000; Trombetta and Helenius 2000). Glucosidase II activity is a key regulatory step for entry into the calnexin cycle, because the location and number of glycans on a chain can influence its activity. Trimming of the second glucose by glucosidase II only occurs efficiently when a second glycan is present, at least for model glycopeptides and model substrates such as pancreatic RNase (Deprez et al. 2005).

Various studies have been performed to address the mechanism by which GT identifies misfolded proteins for exchange with the calnexin cycle, using RNase (Ritter et al. 2005), exo-(1,3)-β-glucanase (Taylor et al. 2004), chymotrypsin inhibitor-2 (Caramelo et al. 2003), and MHC class I molecules (Wearsch et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2011b) as substrates. Overall, the closer a glycan is to an unstructured region of its protein, the better it is glucosylated by GT, with GT recognizing hydrophobic solvent-exposed patches. When RNase was tested, GT only reglucosylated the glycans when they were at or close to disordered regions of the protein (Ritter et al. 2005). However, in the case of exo-(1,3)-β-glucanase, an F280S point mutant that retained enzymatic activity and was only locally misfolded was glucosylated at a distant residue, 40 Å away from the site of structural disruption (Taylor et al. 2004). The differences observed between RNase and exo-(1,3)-β-glucanase may reflect substrate-specific differences in recognition by GT. This is supported by the observation that deletion of GT has no effect on the interaction of VSV G-protein with calnexin, but does compromise the folding of other proteins such as BACE501 and influenza HA by calnexin (Solda et al. 2007). More structural and biochemical studies using an expanded range of clients should help to clarify exactly how GT recognizes misfolded proteins. It should be noted that many ER proteins do not just require the calnexin cycle to fold properly and are assisted by various other chaperones, including hsp70s (e.g., BiP/grp78) and hsp90s (e.g., grp94/gp96) resident in the ER (Marzec et al. 2012).

Misfolded proteins that cannot be rescued by the calnexin cycle are removed from the ER and degraded in the cytosol by the proteasome in a pathway known as ER-associated degradation (ERAD). EDEM1, a mannosidase conserved in yeast (Clerc et al. 2009), is a key player in this process. EDEM1 singles out misfolded glycoproteins and works together with BiP and ERdJ5, a PDI family protein with a BiP-binding J-domain. The way in which EDEM1 recognizes misfolded glycoproteins has been subject to debate, but recent structural and biochemical evidence suggests that calnexin can directly hand over at least some substrates (e.g., misfolded α1 antitrypsin) to the ERdJ5/EDEM1 platform for reductive unfolding before removal of the spent client from the ER (Hagiwara et al. 2011). There are three different EDEM variants in mammals, and their exact contribution to glycoprotein quality control remains to be defined. Interestingly, the residues necessary for glycolytic activity are conserved, and it remains possible that one or more EDEM variants retain some mannosidase activity (Olivari and Molinari 2007).

BEYOND THE CALNEXIN CYCLE

Although the calnexin cycle is now well understood, some aspects of calnexin/calreticulin function still have to be clarified. The first crystal structure of calnexin was published in 2001 at 2.9 Å resolution and revealed a globular lectin domain and a P-domain that extended as a 140 Å arm (Schrag et al. 2001). However, further structural and biochemical work was required to reveal how binding of the lectin domain to mono-glucosylated glycans and binding of the arm domain to ERp57 could be reconciled with affinity for a range of client protein surfaces. A recent calreticulin structure has revealed a putative hydrophobic binding domain on the arm and shown that calreticulin can effectively prevent protein aggregation in the ER (Pocanschi et al. 2011). In addition, a high-resolution 1.95 Å structure of calreticulin in complex with a tetrasaccharide ligand has shown the molecular specificity of the lectin domain for glucose. The O2 oxygen of glucose hydrogen bonds with the Lys111 side chain and the backbone of Gly-124 in a pocket that does not permit the entry of mannose (Kozlov et al. 2010b). Structural studies from the same group also support a role for the peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase (PPIase) cyclophilin B in the calnexin cycle (Kozlov et al. 2010a). PPIases are required for proline isomerization, which is often considered to be a rate-limiting step in protein folding. PPIases have been implicated in folding collagen (Steinmann et al. 1991) and have been found associated with multimeric chaperone complexes in the ER (e.g., Meunier et al. 2002). In the clinic, mutations in cyclophilin B result in osteogenesis imperfecta (a cartilage disease), by limiting type I procollagen chain association (Pyott et al. 2011). However, detailed analysis of the ER resident PPIase family and their function in ER quality control is lacking. The Kozlov study suggests that cyclophilin B occupies the same site in the P-domain as ERp57 (Kozlov et al. 2010a). Further work will be required to evaluate the specificity of cyclophilin B as a PPIase for folding mono-glucosylated glycoproteins, and to determine whether the P-domain of calreticulin itself, rich in prolines, requires cyclophilin B for its own quality control.

Both calnexin and calreticulin bind calcium and regulate its availability in the ER. Mice deficient in calnexin have particular problems with their nervous system, leading to dysmyelination (Kraus et al. 2010), whereas mice lacking calreticulin die during embryogenesis because of defective heart development (Mesaeli et al. 1999). The phenotypes of the knockout mice illustrate the physiological importance of these lectin-like ER chaperones (particularly calreticulin) in maintaining calcium homeostasis as well as being chaperones for glycoproteins (Michalak et al. 2009). The interaction between calnexin and its client is not always entirely sugar dependent, and calnexin may recognize different protein conformations, both in vitro and within the cell (Ihara et al. 1999; Danilczyk and Williams 2001; Brockmeier and Williams 2006). There are also two testis-specific homologs of calnexin and calreticulin, called calmegin and calsperin, respectively (Ikawa et al. 1997, 2011). Both proteins are required for male fertility in the mouse and are necessary for the quality control of specific ADAM proteins that mediate binding of sperm to the egg. The molecular basis for the restricted activity of calmegin and calsperin is not known, although calsperin has a divergent P-domain and lacks broad lectin activity (Ikawa et al. 2011).

The influence of O-linked sugars in determining a protein’s capacity for secretion is often overlooked, because this modification occurs after the primary protein-folding events have taken place in the ER and the serine/threonine acceptor sites are hard to predict. Nevertheless, O-linked sugars may have a regulatory role to play for some proteins. Notch is one example. The Notch proteins are important signaling molecules that can control cell fate during development in several tissues. O-Fucosylation of the EGF repeats in the Notch extracellular domain by protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 (Pofut) occurs in the ER and is essential for Notch function. Subsequent modification of O-fucose in the Golgi by β1-3N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (also known as Fringe, from mutational studies in Drosophila) can alter the activity of Notch; mutations in these transferase enzymes can cause skeletal malformations and other diseases of development (for a recent review, see Rana and Haltiwanger 2011). O-Glucosylation of Notch also occurs at EGF repeats, and the gene responsible has been traced to a protein O-glucosyltransferase (Poglut) called Rumi in Drosophila (Acar et al. 2008). Defects in Poglut/Rumi lead to loss of Notch function and Notch misfolding phenotypes in flies and mice. O-Glycosylation can influence protein quality control in more subtle ways. For example, pro-protein convertases like furin can be O-glycosylated close to the Arg-X-X-Arg processing site, and this can inhibit their activity. It has been proposed that the large family of GalNAc transferases responsible for the initial steps of O-glycosylation may therefore indirectly regulate pro-protein processing, and hence the release of some secreted proteins (Gram Schjoldager et al. 2011). Regulation of quality control may also extend beyond the ER. For example, the mannosidase ERMan1 is almost exclusively O-glycosylated in the Golgi apparatus. ERman1, like EDEM, can remove (hydrolyze) terminal mannose from glycoproteins and may therefore direct misfolded glycoproteins into the ERAD system. Further studies will be required to determine the full extent to which the Golgi apparatus contributes to “ER” quality control (Pan et al. 2011).

To fully understand how glycosylation limits protein secretion, better quantitative measurements of how N-linked, O-linked, and other types of glycans contribute to the folding process are required. Methods are now available to determine cellular dolichol phosphate levels, dolichol-linked oligosaccharides, and the glycosylation of individual Asn-X-Ser/Thr sites (Hulsmeier et al. 2011). Using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), it has been shown that congenital diseases of glycosylation have diminished N-glycosylation site occupancy that correlates with disease severity (Hulsmeier et al. 2007), and this approach could be used to determine the variability of site occupancy between proteins in different cell types.

MAKING DISULFIDE BONDS

Most secreted proteins require disulfide bonds for their correct structure and function (Fig. 3). Disulfide bond formation is supported in the oxidizing environment of the ER, which has a relatively low ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH:GSSG between 1:1 and 3:1) (Hwang et al. 1992). The formation of a disulfide bond between two cysteine residues relies on catalysts of oxidative protein folding to enable the protein to reach its native state. In the late 1990s, it was established in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that a disulfide bond relay exists between PDI and endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase (Ero1p in yeast, Ero1α and Ero1β in mammals) (Frand and Kaiser 1998; Pollard et al. 1998; Sevier and Kaiser 2008). During the course of disulfide bond formation, electrons pass in the opposite direction, from substrate to PDI to Ero, and are delivered to oxygen via FAD. In S. cerevisiae, Ero1p may use alternative flavin electron acceptors, such as FMN, under anaerobic conditions (Gross et al. 2006). Crystal structures of Ero1p and human Ero1α have been solved (for review, see Araki and Inaba 2012) and reveal how the Cys-X-X-Cys active site within Ero1 communicates with FAD and transfers disulfides internally to an amino-terminal redox active site, for disulfide transfer to (and electron acceptance from) PDI. Ero–PDI cocrystals are awaited to see exactly how Ero1 transfers its disulfide to PDI; they should provide more detail of how electron exchange is achieved. Eros are under tight regulatory control to prevent hyperoxidation of the ER and to avoid the generation of potentially damaging reactive oxygen species. The mechanisms differ somewhat between Ero1p, Ero1α, and Ero1β, but each protein uses regulatory (noncatalytic) disulfides with a low reduction potential (for review, see Bulleid and Ellgaard 2011).

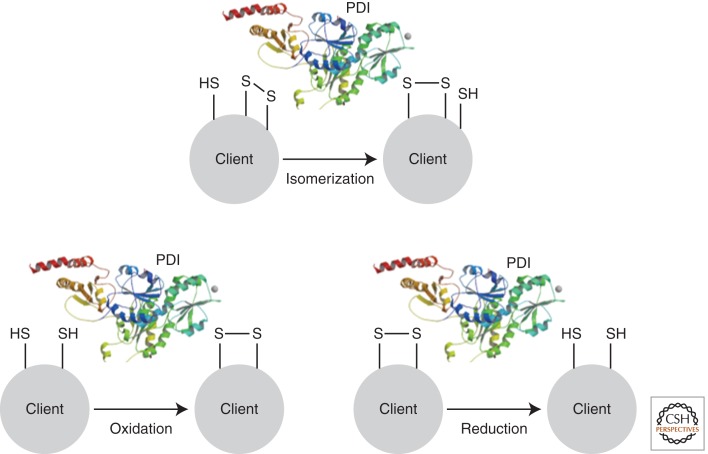

Figure 3.

Disulfide bond formation in the ER. Disulfide bonds form between the –SH groups of two cysteine residues in a protein. The process is mostly confined to the ER in eukaryotes and is catalyzed by enzymes. The most abundant catalyst of disulfide bond formation is PDI, which can introduce (oxidize), remove (reduce), or swap (isomerize) disulfide bonds in a range of client proteins.

In yeast, functional Ero1p is essential for viability, but the situation is more complicated in higher organisms. A clue to potential differences between disulfide bond formation in the ER of yeast and higher eukaryotes came with the phenotype of flies that lacked the Ero1L gene. Drosophila melanogaster Ero1L mutants have a particular defect in the Notch pathway, with misfolded Notch accumulating in the ER (Tien et al. 2008). This phenotype was not expected but may relate to the requirement for complex disulfide bonds in the Lin12–Notch repeats in the extracellular domain of the protein. Mice deficient in Ero1α, Ero1β, or both Ero1α and Ero1β are also viable; the absence of Ero1β results in a mild diabetic phenotype (Zito et al. 2010a), and the absence of Ero1α results in heart abnormalities (Chin et al. 2011). The diabetic phenotype of the Ero1β-deficient mice is likely explained by inefficient production of insulin, which is consistent with the high levels of Ero1β found in the pancreas (Dias-Gunasekara et al. 2005) and the regulation of Ero1β during insulin flux by the pancreatic transcription factor PDX1 (Khoo et al. 2011). How and why Ero1β preferentially controls the oxidative folding of insulin remain open questions. The Ero1α-deficient mice have defective cardiomyocyte calcium signaling, although they were protected to some extent against experimentally induced heart failure (Chin et al. 2011). This study, along with other reports (Wang et al. 2009; Anelli et al. 2012), suggests that Ero1α is important in linking calcium signaling to disulfide bond formation. Taken together with the phenotypes of mice lacking calnexin and calreticulin mentioned above, this highlights the close relationship between calcium homeostasis and protein folding in the ER. This area is likely to attract future interest, particularly with respect to disease, where misfolding and calcium have been linked with conditions as diverse as inflammation (Peters and Raghavan 2011), prion disorders (Torres et al. 2010), and familial hypercholesterolemia (Pena et al. 2010).

The relative well-being of Ero1-deficient mice can be partly explained by compensatory disulfide bond provision from peroxiredoxin IV (Zito et al. 2010b), which is ER localized but can also be secreted. The peroxiredoxin IV enzyme can salvage hydrogen peroxide to drive the oxidation of reduced PDI (Tavender et al. 2010). The source of peroxide for peroxiredoxin IV is likely to come from mitochondrial respiration, NADPH oxidase activity, and Ero1. Although it remains to be seen how peroxiredoxin IV is regulated, this pathway provides a neat solution to the problem of generating potentially harmful oxidants during the course of oxidative protein folding. Nevertheless, additional alternative routes for disulfide bond formation must exist, because peroxiredoxin IV–deficient mice are also viable. Male mice lacking peroxiredoxin IV are fertile, but they show elevated spermatogenic cell death (Iuchi et al. 2009). This suggests that peroxiredoxin IV may have a particular role in protection from oxidative stress during spermatogenesis. In this light, it may be informative to examine whether peroxiredoxin-deficient mice show any age-related phenotypes in other tissues as exposure to reactive oxygen species accumulates.

The difference between yeast and higher eukaryotes in their reliance on Ero proteins probably reflects the sheer range and diversity of proteins that need to be secreted by multicellular species. There are at least 21 human PDIs compared with five in S. cerevisiae, providing potential routes for alternative modes of disulfide bond formation and isomerization (Benham 2012). In addition, yeast Pdi1p is not functionally equivalent to mammalian PDI (Hatahet and Ruddock 2009). In this light, the role of glutathione in supporting disulfide bond formation is being revisited (Appenzeller-Herzog 2011) along with potential roles for other electron carriers (Bánhegyi et al. 2011). Oxidized glutathione (GSSG) was once considered to be the major source of disulfide bond equivalents in the ER, but a substantial fraction of glutathione in the ER is bound to protein as mixed disulfides (Bass et al. 2004). These glutathione–protein mixed disulfides could be clients for PDI isomerase activity and therefore might influence the rate of oxidative protein folding. Although we remain unsure of the true concentration of GSSG in the ER, recent in vitro studies suggest that GSSG could still play a role in the catalytic cycle of PDI at physiologically relevant GSSG levels (Lappi and Ruddock 2011). Advances in our understanding of disulfide bond formation have led to the discovery of alternative pathways. The challenge now is to understand the physiological conditions under which these pathways service different clients.

HOW DOES ER EXIT REGULATE PROTEIN SECRETION?

Once a protein has folded and acquired native disulfide bonds, it is competent for ER exit (Fig. 4). The default pathway for ER exit to the Golgi is via COPII-coated vesicles (for review, see Dancourt and Barlowe 2010). The assembly of COPII-coated vesicles is best understood in yeast, where the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) Sec12p in the donor ER membrane binds inactive, soluble Sar1p-GDP, exchanging its GTP for GDP. The Sar1p-GTP exposes a fatty acid chain that inserts into the membrane and assembles Sec23–Sec24 subunits on the cytoplasmic face of the ER membrane. After recruiting ER cargo, the pre-budding complexes associate with an outer Sec13–Sec31 complex, inducing budding in the ER membrane and formation of the vesicle, which is usually 60–90 nm in diameter. COPII-mediated transport becomes problematic for very large substrates such as collagen molecules, which grow in the ER to diameters of 300–400 nm. This huge topological problem is dealt with by TANGO1 and cTAGE5, two proteins that are required for collagen VII secretion, dimerize at ER exit sites, and bind to Sec23–Sec24 (Malhotra and Erlmann 2011). TANGO1-null mice die at birth and are unable to secrete collagens, lending support to the notion that this protein is largely dedicated to the final steps of collagen quality control (Wilson et al. 2011).

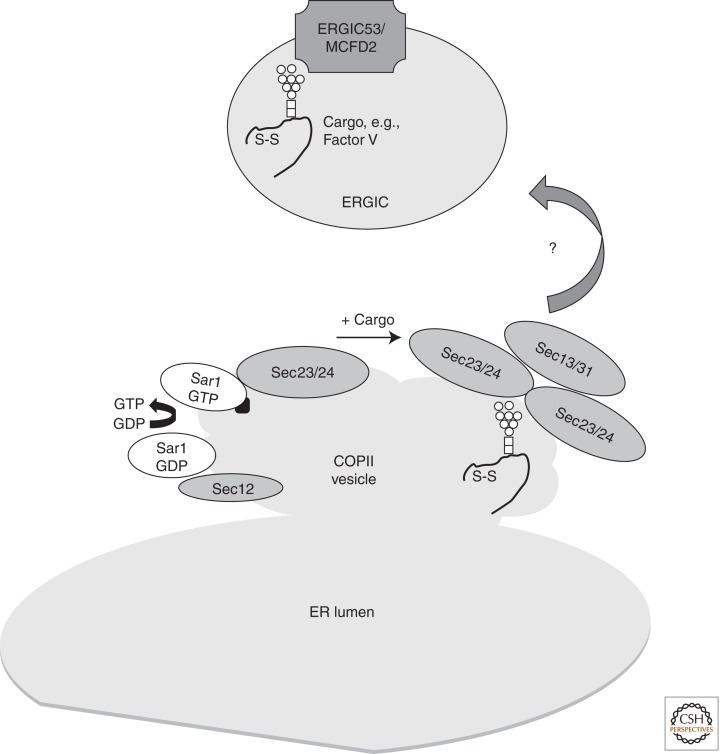

Figure 4.

ER exit, COPII vesicles, and ERGIC. COPII exit vesicles form when Sec12p recruits Sar1p-GDP and exchanges GDP for GTP, enabling Sar1p to insert into the budding membrane. Sar1p facilitates the assembly of Sec23/24 and Sec13/31 at the membrane upon recruitment of cargo. The relationship between COPII vesicles and the ER Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) is not comprehensively defined in higher eukaryotes, and some cargoes may escape the ER directly by bulk flow. ERGIC53 and MCFD2 are required to recruit at least some cargoes to the ERGIC (e.g., Factor V and VIII). (□) N-Acetyl glucosamine; (○) mannose.

COPII-coated vesicles subsequently fuse to form the ER Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC). Although the mechanisms governing ERGIC function are not fully understood, the role of the type I transmembrane protein ERGIC53 in mammals has become clear through studying bleeding disorders. ERGIC53 is a high mannose-binding lectin that cycles between the ER and the ERGIC. ERGIC53 works together with MCFD2, a soluble calcium-dependent protein, to capture its cargo dynamically (Nishio et al. 2010). Various inactivating mutations in the ERGIC53 gene (LMAN1) and in the MCDF2 gene lead to a multiple coagulation factor deficiency called MCFD1 (Nichols et al. 1998) because of a failure to package the heavily glycosylated Factor V and Factor VIII proteins (Zhang et al. 2003). Lman1−/− mice largely replicate human MCFD1 (although there is an unexplained strain-dependent partial lethal phenotype). Vesicles generated from Lman1−/− mice can support COPII-coated vesicle formation (Zhang et al. 2011a), emphasizing that COPII-mediated transport does not depend on ERGIC53’s packaging function. On one hand, the expression of ERGIC53 is ubiquitous, suggesting that it may carry other cargoes. Indeed, it has been proposed that ERGIC53 is also a cargo receptor for α1-antitrypsin in the liver (Nyfeler et al. 2008) and IgM made by antibody-secreting B cells (Anelli et al. 2007). On the other hand, MCFD1 patients do not fail to secrete all of their glycoproteins, suggesting that other cargo receptors may exist. Alternatively, it is possible that ER-to-Golgi transport is only rate-limiting for a few select cargoes such as Factors V and VIII. This would lend support to “bulk flow” theories, which posit that secretion of abundant proteins can be achieved by a default pathway that does not require export signals (for review, see Klumperman 2000). The rate of protein secretion by bulk flow has been estimated in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells using pulse-chase experiments (Thor et al. 2009). The nonglycosylated Semliki Forest virus capsid protein was chosen as a model, because it was unlikely to interact with ER retention factors and cargo receptors. The capsid protein was secreted in a COPII-dependent manner within 15 min of synthesis, with a rate of 155 COPII vesicles per second. Taken together, these studies indicate that cargo receptor–mediated export and secretion by bulk flow are not mutually exclusive and may both coexist, depending on the cell type and its secretory load (Fig. 4).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The last few years have seen major advances in our understanding of the details of quality control in the ER. Some major questions remain to be addressed, such as the identity of the “flippases” for sugar precursors in the ER membrane, the mechanisms for handing over folded glycoproteins to ER exit sites, and understanding what limits disulfide bond formation in different physiological contexts. A major challenge in the field has been quantifying the efficiency of protein secretion. On a sobering note, we are still some way from being able to engineer a cell line to optimally secrete a recombinant protein of choice for the production of a therapeutic. Improved computational strategies and modeling approaches are needed to better understand protein secretion networks, and their key “pinch points,” in a variety of secretory cell types.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the BBSRC, Wellcome Trust, Arthritis Research UK, MRC, Leverhulme Trust, and Royal Society for funding projects in my laboratory.

Footnotes

Editors: John W.B. Hershey, Nahum Sonenberg, and Michael B. Mathews

Additional Perspectives on Protein Synthesis and Translational Control available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Acar M, Jafar-Nejad H, Takeuchi H, Rajan A, Ibrani D, Rana NA, Pan H, Haltiwanger RS, Bellen HJ 2008. Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell 132: 247–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder NN, Shen Y, Brodsky JL, Hendershot LM, Johnson AE 2005. The molecular mechanisms underlying BiP-mediated gating of the Sec61 translocon of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 168: 389–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anelli T, Ceppi S, Bergamelli L, Cortini M, Masciarelli S, Valetti C, Sitia R 2007. Sequential steps and checkpoints in the early exocytic compartment during secretory IgM biogenesis. EMBO J 26: 4177–4188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anelli T, Bergamelli L, Margittai E, Rimessi A, Fagioli C, Malgaroli A, Pinton P, Ripamonti M, Rizzuto R, Sitia R 2012. Ero1α regulates Ca2+ fluxes at the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interface (MAM). Antioxid Redox Signal 16: 1077–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller-Herzog C 2011. Glutathione- and non-glutathione-based oxidant control in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci 124: 847–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki K, Inaba K 2012. Structure, mechanism and evolution of Ero1 family enzymes. Antioxid Redox Signal 16: 790–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataide SF, Schmitz N, Shen K, Ke A, Shan SO, Doudna JA, Ban N 2011. The crystal structure of the signal recognition particle in complex with its receptor. Science 331: 881–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bánhegyi G, Margittai E, Szarka A, Mandl J, Csala M 2011. Crosstalk and barriers between the electron carriers of the endoplasmic reticulum. Antioxid Redox Signal 16: 772–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass R, Ruddock LW, Klappa P, Freedman RB 2004. A major fraction of endoplasmic reticulum-located glutathione is present as mixed disulfides with protein. J Biol Chem 279: 5257–5262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Armache JP, Jarasch A, Anger AM, Villa E, Sieber H, Motaal BA, Mielke T, Berninghausen O, Beckmann R 2011. Structure of the no-go mRNA decay complex Dom34–Hbs1 bound to a stalled 80S ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 715–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham AM 2012. The protein disulfide isomerase family: Key players in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 16: 781–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braakman I, Bulleid NJ 2011. Protein folding and modification in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem 80: 71–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeier A, Williams DB 2006. Potent lectin-independent chaperone function of calnexin under conditions prevalent within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochemistry 45: 12906–12916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulleid NJ, Ellgaard L 2011. Multiple ways to make disulfides. Trends Biochem Sci 36: 485–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramelo JJ, Castro OA, Alonso LG, De Prat-Gay G, Parodi AJ 2003. UDP-Glc:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase recognizes structured and solvent accessible hydrophobic patches in molten globule-like folding intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 86–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N, Oyama R, Ravasi T, Lenhard B, Wells C, et al. 2005. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science 309: 1559–1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin KT, Kang G, Qu J, Gardner LB, Coetzee WA, Zito E, Fishman GI, Ron D 2011. The sarcoplasmic reticulum luminal thiol oxidase ERO1 regulates cardiomyocyte excitation-coupled calcium release and response to hemodynamic load. FASEB J 25: 2583–2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc S, Hirsch C, Oggier DM, Deprez P, Jakob C, Sommer T, Aebi M 2009. Htm1 protein generates the N-glycan signal for glycoprotein degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 184: 159–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancourt J, Barlowe C 2010. Protein sorting receptors in the early secretory pathway. Annu Rev Biochem 79: 777–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilczyk UG, Williams DB 2001. The lectin chaperone calnexin utilizes polypeptide-based interactions to associate with many of its substrates in vivo. J Biol Chem 276: 25532–25540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempski RE Jr, Imperiali B 2002. Oligosaccharyl transferase: Gatekeeper to the secretory pathway. Curr Opin Chem Biol 6: 844–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez P, Gautschi M, Helenius A 2005. More than one glycan is needed for ER glucosidase II to allow entry of glycoproteins into the calnexin/calreticulin cycle. Mol Cell 19: 183–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias-Gunasekara S, Gubbens J, van Lith M, Dunne C, Williams JA, Kataky R, Scoones D, Lapthorn A, Bulleid NJ, Benham AM 2005. Tissue-specific expression and dimerization of the endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase Ero1β. J Biol Chem 280: 33066–33075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focia PJ, Shepotinovskaya IV, Seidler JA, Freymann DM 2004. Heterodimeric GTPase core of the SRP targeting complex. Science 303: 373–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frand AR, Kaiser CA 1998. The ERO1 gene of yeast is required for oxidation of protein dithiols in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell 1: 161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CG, Sanyal S, Rush JS, Waechter CJ, Menon AK 2008. Does Rft1 flip an N-glycan lipid precursor? Nature 454: E3–E5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore R 2011. Structural biology: Porthole to catalysis. Nature 474: 292–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram Schjoldager KT, Vester-Christensen MB, Goth CK, Petersen TN, Brunak S, Bennett EP, Levery SB, Clausen H 2011. A systematic study of site-specific GalNAc-type O-glycosylation modulating proprotein convertase processing. J Biol Chem 286: 40122–40132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Sevier CS, Heldman N, Vitu E, Bentzur M, Kaiser CA, Thorpe C, Fass D 2006. Generating disulfides enzymatically: Reaction products and electron acceptors of the endoplasmic reticulum thiol oxidase Ero1p. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 299–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeuptle MA, Pujol FM, Neupert C, Winchester B, Kastaniotis AJ, Aebi M, Hennet T 2008. Human RFT1 deficiency leads to a disorder of N-linked glycosylation. Am J Hum Genet 82: 600–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara M, Maegawa K, Suzuki M, Ushioda R, Araki K, Matsumoto Y, Hoseki J, Nagata K, Inaba K 2011. Structural basis of an ERAD pathway mediated by the ER-resident protein disulfide reductase ERdj5. Mol Cell 41: 432–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halic M, Becker T, Pool MR, Spahn CM, Grassucci RA, Frank J, Beckmann R 2004. Structure of the signal recognition particle interacting with the elongation-arrested ribosome. Nature 427: 808–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatahet F, Ruddock LW 2009. Protein disulfide isomerase: A critical evaluation of its function in disulfide bond formation. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 2807–2850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius J, Ng DT, Marolda CL, Walter P, Valvano MA, Aebi M 2002. Translocation of lipid-linked oligosaccharides across the ER membrane requires Rft1 protein. Nature 415: 447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsmeier AJ, Paesold-Burda P, Hennet T 2007. N-Glycosylation site occupancy in serum glycoproteins using multiple reaction monitoring liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 6: 2132–2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsmeier AJ, Welti M, Hennet T 2011. Glycoprotein maturation and the UPR. Methods Enzymol 491: 163–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang C, Sinskey AJ, Lodish HF 1992. Oxidized redox state of glutathione in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 257: 1496–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara Y, Cohen-Doyle MF, Saito Y, Williams DB 1999. Calnexin discriminates between protein conformational states and functions as a molecular chaperone in vitro. Mol Cell 4: 331–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikawa M, Wada I, Kominami K, Watanabe D, Toshimori K, Nishimune Y, Okabe M 1997. The putative chaperone calmegin is required for sperm fertility. Nature 387: 607–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikawa M, Tokuhiro K, Yamaguchi R, Benham AM, Tamura T, Wada I, Satouh Y, Inoue N, Okabe M 2011. Calsperin is a testis-specific chaperone required for sperm fertility. J Biol Chem 286: 5639–5646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi Y, Okada F, Tsunoda S, Kibe N, Shirasawa N, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Ikeda Y, Fujii J 2009. Peroxiredoxin 4 knockout results in elevated spermatogenic cell death via oxidative stress. Biochem J 419: 149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RC, Blobel G 1977. Post-translational cleavage of presecretory proteins with an extract of rough microsomes from dog pancreas containing signal peptidase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 74: 5598–5602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda CY, Li J, Oubridge C, Hernandez H, Robinson CV, Nagai K 2010. Recognition of a signal peptide by the signal recognition particle. Nature 465: 507–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanapin A, Batalov S, Davis MJ, Gough J, Grimmond S, Kawaji H, Magrane M, Matsuda H, Schonbach C, Teasdale RD, et al. 2003. Mouse proteome analysis. Genome Res 13: 1335–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher DJ, Karaoglu D, Mandon EC, Gilmore R 2003. Oligosaccharyltransferase isoforms that contain different catalytic STT3 subunits have distinct enzymatic properties. Mol Cell 12: 101–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo C, Yang J, Rajpal G, Wang Y, Liu J, Arvan P, Stoffers DA 2011. Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin-1-like β (ERO1lβ) regulates susceptibility to endoplasmic reticulum stress and is induced by insulin flux in β-cells. Endocrinology 152: 2599–2608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klumperman J 2000. Transport between ER and Golgi. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12: 445–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov G, Bastos-Aristizabal S, Maattanen P, Rosenauer A, Zheng F, Killikelly A, Trempe JF, Thomas DY, Gehring K 2010a. Structural basis of cyclophilin B binding by the calnexin/calreticulin P-domain. J Biol Chem 285: 35551–35557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov G, Pocanschi CL, Rosenauer A, Bastos-Aristizabal S, Gorelik A, Williams DB, Gehring K 2010b. Structural basis of carbohydrate recognition by calreticulin. J Biol Chem 285: 38612–38620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus A, Groenendyk J, Bedard K, Baldwin TA, Krause KH, Dubois-Dauphin M, Dyck J, Rosenbaum EE, Korngut L, Colley NJ, et al. 2010. Calnexin deficiency leads to dysmyelination. J Biol Chem 285: 18928–18938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakkaraju AK, Mary C, Scherrer A, Johnson AE, Strub K 2008. SRP keeps polypeptides translocation-competent by slowing translation to match limiting ER-targeting sites. Cell 133: 440–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappi AK, Ruddock LW 2011. Reexamination of the role of interplay between glutathione and protein disulfide isomerase. J Mol Biol 409: 238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizak C, Gerber S, Numao S, Aebi M, Locher KP 2011. X-ray structure of a bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase. Nature 474: 350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra V, Erlmann P 2011. Protein export at the ER: Loading big collagens into COPII carriers. EMBO J 30: 3475–3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandon EC, Trueman SF, Gilmore R 2009. Translocation of proteins through the Sec61 and SecYEG channels. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21: 501–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary C, Scherrer A, Huck L, Lakkaraju AK, Thomas Y, Johnson AE, Strub K 2010. Residues in SRP9/14 essential for elongation arrest activity of the signal recognition particle define a positively charged functional domain on one side of the protein. RNA 16: 969–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzec M, Eletto D, Argon Y 2012. GRP94: An HSP90-like protein specialized for protein folding and quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823: 774–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason N, Ciufo LF, Brown JD 2000. Elongation arrest is a physiologically important function of signal recognition particle. EMBO J 19: 4164–4174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesaeli N, Nakamura K, Zvaritch E, Dickie P, Dziak E, Krause KH, Opas M, MacLennan DH, Michalak M 1999. Calreticulin is essential for cardiac development. J Cell Biol 144: 857–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier L, Usherwood YK, Chung KT, Hendershot LM 2002. A subset of chaperones and folding enzymes form multiprotein complexes in endoplasmic reticulum to bind nascent proteins. Mol Biol Cell 13: 4456–4469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak M, Groenendyk J, Szabo E, Gold LI, Opas M 2009. Calreticulin, a multi-process calcium-buffering chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J 417: 651–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng DT, Brown JD, Walter P 1996. Signal sequences specify the targeting route to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J Cell Biol 134: 269–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols WC, Seligsohn U, Zivelin A, Terry VH, Hertel CE, Wheatley MA, Moussalli MJ, Hauri HP, Ciavarella N, Kaufman RJ, et al. 1998. Mutations in the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment protein ERGIC-53 cause combined deficiency of coagulation factors V and VIII. Cell 93: 61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio M, Kamiya Y, Mizushima T, Wakatsuki S, Sasakawa H, Yamamoto K, Uchiyama S, Noda M, McKay AR, Fukui K, et al. 2010. Structural basis for the cooperative interplay between the two causative gene products of combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 4034–4039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyfeler B, Reiterer V, Wendeler MW, Stefan E, Zhang B, Michnick SW, Hauri HP 2008. Identification of ERGIC-53 as an intracellular transport receptor of α1-antitrypsin. J Cell Biol 180: 705–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivari S, Molinari M 2007. Glycoprotein folding and the role of EDEM1, EDEM2 and EDEM3 in degradation of folding-defective glycoproteins. FEBS Lett 581: 3658–3664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne AR, Rapoport TA, van den Berg B 2005. Protein translocation by the Sec61/SecY channel. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21: 529–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S, Wang S, Utama B, Huang L, Blok N, Estes MK, Moremen KW, Sifers R.N. 2011. Golgi localization of ERManI defines spatial separation of the mammalian glycoprotein quality control system. Mol Biol Cell 22: 2810–2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Rapoport TA 2012. Mechanisms of Sec61/SecY-mediated protein translocation across membranes. Annu Rev Biophys 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parodi AJ 2000. Protein glucosylation and its role in protein folding. Annu Rev Biochem 69: 69–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena F, Jansens A, van Zadelhoff G, Braakman I 2010. Calcium as a crucial cofactor for low density lipoprotein receptor folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 285: 8656–8664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters LR, Raghavan M 2011. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium depletion impacts chaperone secretion, innate immunity, and phagocytic uptake of cells. J Immunol 187: 919–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocanschi CL, Kozlov G, Brockmeier U, Brockmeier A, Williams DB, Gehring K 2011. Structural and functional relationships between the lectin and arm domains of calreticulin. J Biol Chem 286: 27266–27277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard MG, Travers KJ, Weissman JS 1998. Ero1p: A novel and ubiquitous protein with an essential role in oxidative protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell 1: 171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyott SM, Schwarze U, Christiansen HE, Pepin MG, Leistritz DF, Dineen R, Harris C, Burton BK, Angle B, Kim K, et al. 2011. Mutations in PPIB (cyclophilin B) delay type I procollagen chain association and result in perinatal lethal to moderate osteogenesis imperfecta phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 20: 1595–1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana NA, Haltiwanger RS 2011. Fringe benefits: Functional and structural impacts of O-glycosylation on the extracellular domain of Notch receptors. Curr Opin Struct Biol 21: 583–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter C, Helenius A 2000. Recognition of local glycoprotein misfolding by the ER folding sensor UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase. Nat Struct Biol 7: 278–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter C, Quirin K, Kowarik M, Helenius A 2005. Minor folding defects trigger local modification of glycoproteins by the ER folding sensor GT. EMBO J 24: 1730–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SL, Whitfield KM, Vogel JP, Rose MD, Schekman RW 1992. Sec61p and BiP directly facilitate polypeptide translocation into the ER. Cell 69: 353–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S, Menon AK 2009. Specific transbilayer translocation of dolichol-linked oligosaccharides by an endoplasmic reticulum flippase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 767–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S, Menon AK 2010. Stereoselective transbilayer translocation of mannosyl phosphoryl dolichol by an endoplasmic reticulum flippase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 11289–11294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraogi I, Shan SO 2011. Molecular mechanism of co-translational protein targeting by the signal recognition particle. Traffic 12: 535–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag JD, Bergeron JJ, Li Y, Borisova S, Hahn M, Thomas DY, Cygler M 2001. The structure of calnexin, an ER chaperone involved in quality control of protein folding. Mol Cell 8: 633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevier CS, Kaiser CA 2008. Ero1 and redox homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783: 549–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao S, Hegde RS 2011. A calmodulin-dependent translocation pathway for small secretory proteins. Cell 147: 1576–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel V, Walter P 1986. Removal of the Alu structural domain from signal recognition particle leaves its protein translocation activity intact. Nature 320: 81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solda T, Galli C, Kaufman RJ, Molinari M 2007. Substrate-specific requirements for UGT1-dependent release from calnexin. Mol Cell 27: 238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann B, Bruckner P, Superti-Furga A 1991. Cyclosporin A slows collagen triple-helix formation in vivo: Indirect evidence for a physiologic role of peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans-isomerase. J Biol Chem 266: 1299–1303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strub K, Moss J, Walter P 1991. Binding sites of the 9- and 14-kilodalton heterodimeric protein subunit of the signal recognition particle (SRP) are contained exclusively in the Alu domain of SRP RNA and contain a sequence motif that is conserved in evolution. Mol Cell Biol 11: 3949–3959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavender TJ, Springate JJ, Bulleid NJ 2010. Recycling of peroxiredoxin IV provides a novel pathway for disulphide formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J 29: 4185–4197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SC, Ferguson AD, Bergeron JJ, Thomas DY 2004. The ER protein folding sensor UDP-glucose glycoprotein-glucosyltransferase modifies substrates distant to local changes in glycoprotein conformation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Y, Bui N, Strub K 1997. A truncation in the 14 kDa protein of the signal recognition particle leads to tertiary structure changes in the RNA and abolishes the elongation arrest activity of the particle. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 1920–1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor F, Gautschi M, Geiger R, Helenius A 2009. Bulk flow revisited: Transport of a soluble protein in the secretory pathway. Traffic 10: 1819–1830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tien AC, Rajan A, Schulze KL, Ryoo HD, Acar M, Steller H, Bellen HJ 2008. Ero1L, a thiol oxidase, is required for Notch signaling through cysteine bridge formation of the Lin12–Notch repeats in Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Biol 182: 1113–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M, Castillo K, Armisen R, Stutzin A, Soto C, Hetz C 2010. Prion protein misfolding affects calcium homeostasis and sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress. PLoS ONE 5: e15658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombetta ES, Helenius A 2000. Conformational requirements for glycoprotein reglucosylation in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 148: 1123–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P, Blobel G 1981. Translocation of proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum III. Signal recognition protein (SRP) causes signal sequence-dependent and site-specific arrest of chain elongation that is released by microsomal membranes. J Cell Biol 91: 557–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Li SJ, Sidhu A, Zhu L, Liang Y, Freedman RB, Wang CC 2009. Reconstitution of human Ero1-Lα/protein-disulfide isomerase oxidative folding pathway in vitro. Position-dependent differences in role between the α and α′ domains of protein-disulfide isomerase. J Biol Chem 284: 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearsch PA, Peaper DR, Cresswell P 2011. Essential glycan-dependent interactions optimize MHC class I peptide loading. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 4950–4955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CM, Roebuck Q, High S 2008. Ribophorin I regulates substrate delivery to the oligosaccharyltransferase core. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 9534–9539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DG, Phamluong K, Li L, Sun M, Cao TC, Liu PS, Modrusan Z, Sandoval WN, Rangell L, Carano RA, et al. 2011. Global defects in collagen secretion in a Mia3/TANGO1 knockout mouse. J Cell Biol 193: 935–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapun A, Petrescu SM, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Thomas DY, Bergeron JJ 1997. Conformation-independent binding of monoglucosylated ribonuclease B to calnexin. Cell 88: 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapun A, Darby NJ, Tessier DC, Michalak M, Bergeron JJ, Thomas DY 1998. Enhanced catalysis of ribonuclease B folding by the interaction of calnexin or calreticulin with ERp57. J Biol Chem 273: 6009–6012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Cunningham MA, Nichols WC, Bernat JA, Seligsohn U, Pipe SW, McVey JH, Schulte-Overberg U, de Bosch NB, Ruiz-Saez A, et al. 2003. Bleeding due to disruption of a cargo-specific ER-to-Golgi transport complex. Nat Genet 34: 220–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Zheng C, Zhu M, Tao J, Vasievich MP, Baines A, Kim J, Schekman R, Kaufman RJ, Ginsburg D 2011a. Mice deficient in LMAN1 exhibit FV and FVIII deficiencies and liver accumulation of α1-antitrypsin. Blood 118: 3384–3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wearsch PA, Zhu Y, Leonhardt RM, Cresswell P 2011b. A role for UDP-glucose glycoprotein glucosyltransferase in expression and quality control of MHC class I molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 4956–4961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito E, Chin KT, Blais J, Harding HP, Ron D 2010a. ERO1-β, a pancreas-specific disulfide oxidase, promotes insulin biogenesis and glucose homeostasis. J Cell Biol 188: 821–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito E, Melo EP, Yang Y, Wahlander A, Neubert TA, Ron D 2010b. Oxidative protein folding by an endoplasmic reticulum-localized peroxiredoxin. Mol Cell 40: 787–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]