Abstract

The popular targeted molecular dynamics (TMD) method for generating transition paths in complex biomolecular systems is revisited. In a typical TMD transition path, the large-scale changes occurring early, and the small-scale changes tend to occur later. As a result, the order of events in the computed paths depends on the direction in which the simulations are performed. To identify the origin of this bias, and to propose a method in which the bias is absent, variants of TMD in the restraint formulation are introduced and applied to the complex Open↔Closed transition in the protein Calmodulin. Due to the global best-fit rotation that is typically part of the TMD method, the simulated system is guided implicitly along the lowest-frequency normal modes, until the large spatial scales associated with these modes are near the target conformation. The remaining portion of the transition is described progressively by higher-frequency modes, which correspond to smaller-scale rearrangements. A straightforward modification of TMD that avoids the global best-fit rotation is the locally restrained TMD (LRTMD) method, in which the biasing potential is constructed from a number of TMD potentials, each acting on a small connected portion of the protein sequence. With a uniform distribution of these elements, transition paths that lack the length-scale bias are obtained. Trajectories generated by steered MD in dihedral angle space (DSMD), a method that avoids best-fit rotations altogether, also lack the length-scale bias. To examine the importance of the paths generated by TMD, LRTMD, and DSMD in the actual transition, we use the finite-temperature string method to compute the free energy profile associated with a transition tube around a path generated by each algorithm. The free energy barriers associated with the paths are comparable, suggesting that transitions can occur along each route with similar probabilities. This result indicates that a broad ensemble of paths needs to be calculated to obtain a full description of conformational changes in biomolecules. The breadth of the contributing ensemble suggests that energetic barriers for conformational transitions in proteins are offset by entropic contributions that arise from a large number of possible paths.

1 Introduction

Many proteins of interest populate multiple conformational states, whose relative stability is modulated by ligands, other biomolecules and the ambient solution environment. Transitions between different conformations of such proteins in response to changes in the environment (e.g. binding of a ligand, interactions with other proteins or DNA) are an essential element in many cellular processes, such as enzyme catalysis,1 DNA replication,2,3 refolding of misfolded proteins,4 ATP synthesis and organelle transport by molecular motors,5,6 and muscle contraction.7 Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a useful tool for the study of biomolecules with known structures that can be performed at atomic spatial and femtosecond temporal resolution, which are typically not accessible in experiments. In principle, conformational transitions can be observed in a sufficiently long MD simulation trajectory. Present-day computer resources, however, limit the duration of typical MD simulations to tens or hundreds of nanoseconds. Since many transitions occur on the scale of microsecond and longer, they are beyond the reach of conventional MD. Many techniques have been developed to extend the conformational sampling beyond that achievable by conventional MD, e.g. Umbrella Sampling,8,9 Metadynamics,10 Adaptive Biasing Force,11 Adiabatic MD,12 Temperature Accelerated MD,13 and Orthogonal Space Random Walk.14 These methods are well-suited for the exploration of phase space, but not for computing physically meaningful transition paths between known conformations.

The finite-temperature string method15,16 can be used to compute transition paths, as well as the associated free energy profiles and transition rates. However, the string method requires an initial path that must be generated independently, e.g. using zero-temperature methods,17–20 or by the methods discussed in the present study. Specialized path-based collective variables have also been devised for use with Umbrella Sampling or Metadynamics to improve upon an initial path, in the spirit of the string method.21 Transition path sampling (TPS)22,23 can improve upon an initial path connecting two structures that correspond to metastable states (although, in principle, only one intermediate configuration is required to start TPS), by performing a “random walk” in trajectory space. However, because TPS relies on the generation of unbiased trajectories by MD, it can be very costly to apply to large biomolecules in which transitions are dominated by diffusive motions.

A simple method for finding transition paths that does not require the specification of collective variables is targeted molecular dynamics (TMD).24,25 In the original TMD implementation,24 the simulation system is initialized from one structure and evolves according to a standard MD potential augmented by an evolving holonomic constraint, which gradually steers the simulation structure toward a specified (target) structure. The constraint guarantees that the root-mean-square difference (RMSD) between the simulation structure and the target structure, typically computed using all atoms in the molecule, is reduced to near zero within the prescribed simulation time. In the standard TMD method, the presence of an evolving constraint implies that the simulation system does not sample an equilibrium ensemble, and therefore TMD cannot be used to compute equilibrium properties, such as free energy profiles along the transition. In addition, because of the constraint, the system may be forced to overcome very high energy barriers.26 Despite these limitations, TMD has been found to generate plausible transition paths, and has been used in studies of allostery and a variety of transitions in large proteins.4,27–30 Transition paths obtained with TMD have also been employed to initialize TPS,31,32 umbrella sampling,33 and the string method.34

Several related methods have been introduced since the original TMD publication. In restricted perturbation (RP) TMD,26 the evolution of the holonomic constraint is modified such that the simulation system is not allowed to undergo a constrained displacement toward the target structure that exceeds a prescribed threshold value. The instantaneous value of the constraint is calculated from the actual displacement. The main feature of RPTMD is that the evolution of the constraint slows down in the regions of large free energy gradients, allowing the simulation trajectories to lengthen naturally and explore more conformational space in such regions. RPTMD also does not restrict spontaneous evolution of the simulated structure toward the target.26

In an alternative formulation of TMD, which we refer to as restrained (R)TMD to distinguish it from the original method, the holonomic constraint is replaced by a restraint potential based on the RMSD between the simulation and target structures.35 The RTMD method is simpler to implement than TMD because it does not require modification of the MD integrator (see Section 2.1). A recent study found that TMD and RTMD generate similar transition paths.36 The difference between the simulation and target structures was measured in terms of the mean-squared inter-atom distance37 (MSID) defined as

| (1) |

where d (t)i j and are the distances between atoms i and j in the simulation and target structures (at time t), respectively, and N is the number of atoms to which restraint forces are applied. To our knowledge, a systematic comparison between TMD and RTMD using the RMSD as the progress coordinate has not been made. We note that the RTMD method is conceptually similar to Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD),38 in that both methods employ a time-dependent restraint potential to guide the simulation from one state to the other. The difference is that, in the original applications of SMD to the unbinding of ligands (e.g. unbinding of the Avidin-Biotin Complex,39,40), the restraint potential was a function of the linear distance between groups of atoms. When the biasing coordinate is the best-fit RMSD, it seems more appropriate to use the term RTMD to emphasize the similarity with TMD. We will use the term SMD for steered dynamics in dihedral angles (see below).

A variant of SMD is biased (B)MD.37 The main difference between BMD and other restraint methods (SMD or RTMD) is that in BMD the biasing potential is “one-sided,” i.e. forces are applied only if the value of the progress coordinate (e.g. MSID) computed from the simulation structure is ahead of the corresponding target value. The target value of the progress coordinate is updated only if it is behind the value computed from the structure. BMD is similar in concept to RP-TMD in that the target value of the progress coordinate evolves more slowly along path segments that correspond to high free-energy gradients as a function of the progress coordinate, and in that spontaneous evolution toward the target structure is not restricted. In the original BMD method,37 the restraint potential is defined based on the MSID. BMD was used to simulate forced unfolding of β-sandwich and α-helical proteins,37,41 and the conformational change in the F1-ATPase. 27 A hybrid method, which combines the use of general progress variables with the one-sided application of the BMD restraint potential was used to generate initial trajectories for use with TPS.32

The TMD class of methods for modeling conformational transitions has been widely applied to large biomolecules due to its algorithmic simplicity, its ability to generate plausible paths within a prescribed simulation time (typically of the order of a nanosecond27,29,30,36,42,43), and the absence of a requirement to specify a reaction coordinate. A particular bias that appears to be shared by all existing TMD algorithms is the tendency of large-scale motions to precede small-scale ones, which we call below the ‘large-scales-first’ feature. Although this feature of TMD has been identified previously,26,29,36,44 to our knowledge, neither the causes, nor a possible modification to remove the bias, have been investigated. Addressing this question, however, is of paramount importance in the modeling of conformational transitions that involve the interplay between small-scale events and large-scale events. Examples are allosteric transitions in proteins that involve the motions of smaller loops due to, e.g., the binding of a ligand, coupled to motions of larger subdomains, such as those occurring in Myosins or ATPases upon nucleotide binding.30,45,46 In the modeling of such transitions by TMD, large-amplitude motions will usually occur before small-amplitude ones, which could disagree with the actual sequence of transition events (e.g. those that would be observed in unbiased dynamical trajectories). A cursory examination of such transition paths might, for example, rule out the induced fit mechanism in favor of a population shift mechanism.47,48 In the latter, ligand binding effectively ‘traps’ the target molecule in a particular conformation that is observed only after certain large-scale motions, shifting the distribution of populations in favor of the ligand-bound conformations.

To investigate the source of the ‘large-scales-first’ feature, and to propose a method in which the feature is absent, we test three biasing methods, two of which are straightforward extensions of the RTMD method, and the other involves biasing in internal coordinates. We then compare the transition paths generated by each method with those obtained from standard TMD. Variants of TMD and RTMD have previously been tested on small systems such as the alanine dipeptide.26,35 The simplicity of such systems implies that paths connecting multiple conformations are few and relatively simple, and will generally lack the broad range of transition length scales that are desirable for the present study. Similarly, although the overall Rigor→Postrigor conformational transition studied by RTMD30 is quite complicated, the domain to which biasing forces were applied was localized and small (~300 atoms), with a relatively simple conformational change. Huang et al. 36 used the catalytic domain of the Src kinase protein Lyn as a test system. However, despite the moderately large size of the Src kinase domains (ca. 300 res.), the conformational transition can be described using only a few parameters, such as the conformation of a 20-residue loop A, the opening of a “lid” domain, and an approximately rigid motion of the αC helix.36

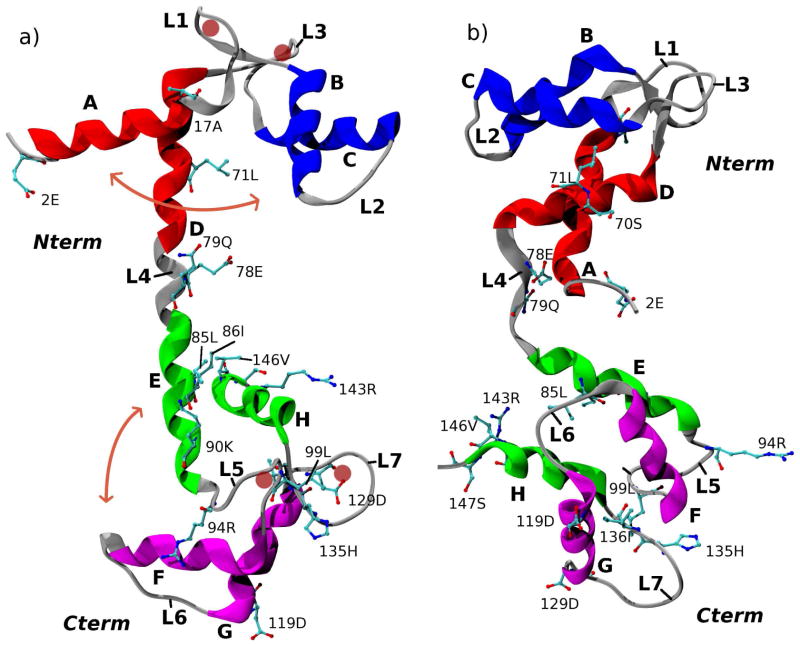

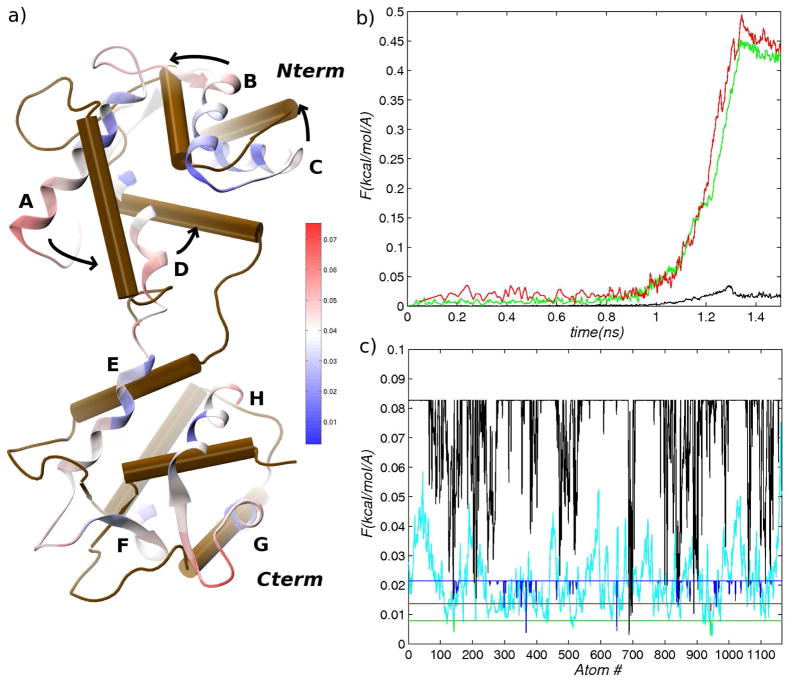

As a test case to compare the various transition paths, we chose the Ca2+-binding protein Calmodulin (CaM), which undergoes a complex Closed↔Open conformational transition.49 The CaM family and its homologs have been studied extensively because of their ubiquity in signal transduction and regulation of many cellular processes (see Refs. 49–55 and references therein). CaM proteins are known to bind to more than 300 target proteins56 in response to changes in the Ca2+ concentration. The broad substrate specificity is made possible by the structure of CaM, in which two globular N-terminal and C-terminal domains are connected by a ~28-residue linker (see Figure 1). Each globular domain is composed of two helix-turn-helix motifs (EF-hands),51 which undergo a closed→open transition upon the binding of Ca2+ ions, partially exposing hydrophobic target-binding pockets. There is strong evidence that the binding of Ca2+ ions to EF-hand loops (see Figure 1) is coupled to the opening of the EF-hand helices54 and that Ca2+-binding occurs in a cooperative fashion.49,54,55 In addition to the Open and Closed EF-hand structures shown in Figure 1, partially open states have been observed in solution experiments57,58 and in MD simulations.59,60 The interdomain linker is known to be flexible in solution,49,57,58,60,61 and, together with the hydrophobic pockets, provides a deformable target-binding interface that permits high-affinity binding to a variety of protein targets.49,57,62 The present state of understanding of the mechanism of CaM function suggests that the Closed↔Open transition involves a delicate interplay between different spatial scales, making CaM a realistic system for testing transition path simulation methods. The Ca2+-bound and the Ca2+-free apo structures of CaM are very different, with the heavy-atom RMSD of ~13Å between the two structures (see also Figure 1). The large RMSD is expected to illustrate clearly the differences between the biasing methods employed in this study. The only TMD simulation of a CaM homologue known to us investigates the Closed→Open transition in the Ca2+-binding protein recoverin.43 Although the order of events in the transition is not discussed from the viewpoint of large vs. small spatial scales, it is evident from the discussion of the transition path that large-scale rearrangements precede smaller-scale ones. The transition was shown to begin with a reorientation of the C-terminal and N-terminal domains, followed by rearrangements of α-helices, ending with the motion of a myristoyl moiety.43 The precedence of large-scale rearrangements is qualitatively consistent with the TMD and RTMD simulations of CaM reported here in Section 3.2.

Figure 1.

Calmodulin in (a) Open form (1EXR) and (b) Closed form (1DMO). Helix-loop-helix (HLH) motifs A-L1-B and C-L3-D comprise two EF-hands in the N-terminal domain (Nterm), and HLH motifs E-L5-F and G-L7-H comprise two EF-hands in the C-terminal domain (Cterm). Loops L1, L3, L5, and L7 form binding sites for Ca2+ ions, which were removed prior to simulation (the location of the ions within the loops is indicated by light red circles). Loop L4 forms the linker between the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. This loop is α-helical in the Open structure and unwound in the Closed structure. Residues that were mutated in the Xenopus laevis sequence are shown in ball-and-stick representation (see text). Residues that comprise the various structural elements are listed in Supporting Table S1. The heavy-atom RMSDs between the Nterm and Cterm domains in the two structures are 5.6Å and 5.5Å, respectively. Images were generated with VMD.94

2 Methods

As mentioned in the Introduction, for conformational transitions in which large-scale motion occurs in response to small-scale rearrangements, such as the binding of a small ligand to a large protein, followed by a rearrangement of protein subdomains, transition paths generated by TMD are likely to show an incorrect order of events. The methods described in this section were used to investigate the origins of the large scale bias, and to provide possible approaches that eliminate the bias, while preserving the modest computational requirements of TMD.

2.1 Scaled-force TMD method

To investigate the extent to which the difference in the biasing force magnitudes per se favor the large-scale motions, here we introduce a scaled-force (SF) TMD method, which limits the magnitude of the targeting force. The algorithm is based on the restrained formulation of TMD,24,35 in which a restraint potential, rather than a holonomic constraint drives the system to the target configuration. It was shown recently36 that the standard TMD and restrained RTMD generate similar transition paths when the MSID progress variable is employed. The present results show that this is also the case if the RMSD progress variable is used (see Section 3.2).

Let be set of N coordinate triplets of the atoms to which targeting forces are applied, and , where mi are the atomic masses. Defining center-of-mass (COM) coordinates by , we apply the following harmonic potential to the simulated structure:

| (2) |

In Eq. (2), kRTMD is the force constant,

| (3) |

is the RMSD function, and r̂ and r̂T represent the current and target atomic coordinates, respectively. ρ0 (t) is the desired equilibrium value of ρ at time t, which in an RTMD simulation is reduced gradually from an initial value, e.g. the RMSD between the initial and target structures, to a target value e.g. 0Å–1Å. A(r̂, r̂T) is a rotation matrix, chosen such that ρ(r̂, A(r̂, r̂T)r̂T) is minimum, i.e. A(r̂, r̂T)r̂T is a “best fit” of r̂T onto r̂63–66 (see Appendix A for an alternative definition). Henceforth, we omit the subscripts on URTMD and kRTMD if the meaning is clear from the context. Explicit time dependence of U and ρ0 is also omitted, and A (r̂, r̂T) is written simply as A. Restraint forces are obtained from Eq. (2):

| (4) |

where rT, j denotes the target coordinate triplet (xT, j, yT, j, zT, j), Ax is the first row of A, and the equation is written for the x-component of the force. Similar expressions hold for the y- and z-components. The simplicity of Eq. (4) comes from the fact that the derivatives of the rotation matrix A make no contribution to the force, as was claimed in Ref. 67. In Appendix A we give a simple proof of this claim, and discuss a special case for which derivatives of A must be included (which are calculated in the supporting information).

Eq. (4) shows that in RTMD (as in TMD24–26,36) the force acting on an atom is proportional to the difference between its current and target positions, so that RTMD is likely to favor the occurrence of large-scale motions before small-scale ones. To remove the bias arising in the RTMD equations, we limit the maximum force that can be applied in Eq. (4):

| (5) |

| (6) |

Eqs. (5) and (6) ensure that the force on all atoms whose current and target positions differ by more than Δrmax will have the same magnitude. Therefore, large-scale motion will not be biased by the magnitude differences of the RTMD forces to occur first. A feature of the modified RTMD equations is that the force in Eq. (5) can no longer be written as the gradient of a potential. This means that the simulations will not follow Hamiltonian dynamics. In particular, free-energy Umbrella Sampling simulations8 that use an RMSD potential68 cannot be used. This drawback, which is present also in constrained TMD, is not important for the present purpose of rapid generation of transition paths between conformations of a molecule. We note that after the simulation structure is sufficiently close to the target structure (i.e. ||ri −AirT,i|| < Δrmax ∀ i ∈ {1,…, N}), Eq. (5) becomes identical to Eq. (4).

In addition, the simulated molecule will now experience a net force and torque. This does not occur in the original RTMD formulation because rotation/translation invariance is implicit in Eq. (2) (see Appendix A). One possible way to remove net force and torque is to apply Eckart constraints.35,69,70 This approach, however, requires modifying the MD integrator, which is difficult to do in some MD packages optimized for speed.71 Since applying external forces is typically easy, we instead compute a minimum-norm force correction f̂ to the forces in Eq. (5) using standard tools in numerical methods,72,73 such that the corrected forces F̂*+ f̂ sum up to zero and generate no net torque on the system. For the SFTMD calculations performed here, the RMS magnitude of f̂ is 5–10% of that of F̂*, indicating that the forces are not changed significantly by the correction. Details of the construction of f̂ are provided as supporting information.

2.2 Locally-restrained TMD method

The locally-restrained TMD method (LRTMD) is one of two methods developed to test the effect of the global best-fit alignment between the simulation and target structures that is used as part of TMD methods (including SFTMD). Although the LRTMD method is similar in implementation to the standard RTMD, it is based on local regions of the protein molecule, each comprised of a small group of residues. The biasing forces are derived from the restraint potential ULRTMD, which is built up from a sum of conventional RTMD potentials acting on subsets of atoms that are, generally, much smaller in size than the molecule itself. The potential has the form

| (7) |

For brevity, we have used An to denote , and the coordinate sets r̂n and correspond to different (possibly overlapping) subsets of the structure. Note that the best-fit rotation matrix An is recomputed for each of the M RMSDs above. Comparing Eqs. (7) and (2), one sees that the RMSD of Eq. (2) is replaced by a generalized distance δ, in which N Cartesian interatomic distances are replaced by M RMSDs between groups of atoms. The ‘hierarchical’ potential of in Eq. (7) is expected to enforce the global conformational transition via a superposition of a number of local small-scale transitions. The fact that the potential is constructed from local (small-scale), and not global (large-scale) transitions, suggests that small-scale rearrangements will occur before large-scale ones. That this is the case is shown in Section 3.4. In analogy to ρ0 (t) in Section 2.1, δ0 (t) is the prescribed equilibrium value of the potential at time t, which is reduced during a simulation from the initial value (computed such that the potential in Eq. (7) vanishes), and the final value (which we set to 0Å). We note that the forces arising from the potential are easily calculated from Eq. (4) and the chain rule. To speed up force calculation in the cases for which the number of component RMSDs M is large (e.g. >50), the contributions to the forces arising from different RMSD components are evaluated on different processors, and subsequently combined using message-passing calls (MPI).

2.3 Steered dynamics in dihedral angles

In addition to targeting dynamics in Cartesian coordinates described in the previous subsections, we investigated steered dynamics with a restraint applied to a set of dihedral angles (DSMD). In this approach, the following restraint potential was used

| (8) |

in which ψj are the

dihedral angles included in the potential, and ε 0 (t) is reduced gradually from an initial value (computed such that the potential vanishes initially) to the final value (which we set to zero radians). To remove the ambiguity in the value of the difference ψj (r̂) − ψj (r̂T), which arises due to the periodicity of torsional angles, we use the value that has the smallest magnitude in the range (−π … π]. The dihedral angles that are included in the potential of Eq. (8) are discussed in Section 2.6 (Biased MD simulations).

dihedral angles included in the potential, and ε 0 (t) is reduced gradually from an initial value (computed such that the potential vanishes initially) to the final value (which we set to zero radians). To remove the ambiguity in the value of the difference ψj (r̂) − ψj (r̂T), which arises due to the periodicity of torsional angles, we use the value that has the smallest magnitude in the range (−π … π]. The dihedral angles that are included in the potential of Eq. (8) are discussed in Section 2.6 (Biased MD simulations).

2.4 Calculation of Free Energy Profiles

The finite-temperature string method (FTS)15,16,74 was used to calculate the free energy (FE) profiles associated with transition paths obtained using RTMD, LRTMD, and DSMD.

A numerical implementation of the FTS algorithm has been described in Ref. 16. The essential difference in its use in the present calculations is that the transition tube is kept centered on the initial path, and is assigned a prescribed width of ~1Å. The two constraints allow one to compare different paths directly on the basis of the associated free energies, since the transition tubes remain restricted to the vicinity of the corresponding paths. A drawback of the second constraint is the requirement to specify a value for the tube width a priori, which may lead to the neglect of important regions of conformational space, effectively overestimating the free energy at corresponding locations along the path. Although such errors may lead to the overestimation in the free energy along a single given path, they are expected to have a smaller effect on the comparison of different paths,34 which is the subject of the present study. The use of this constraint is important for the present calculations so that the conformational space within the tube is small enough to be sampled in relatively short 5-ns MD simulations (see below). The FTS calculation simulation protocol is as follows. Trajectories 1.5 ns in length were generated by RTMD, LRTMD, or DSMD, and were sampled in 1ps intervals. The resulting set of 1500 structures was used to generate a sequence of 128 equispaced structures (string of replicas) using linear interpolation in Cartesian coordinates. To remove bad contacts generated by the interpolation procedure, while maintaining the equal spacing between adjacent replicas, 500,000 iterations of steepest descent minimization combined with a linear interpolation/reparametrization procedure20 were performed. Reparametrization was done after every 20 steps of minimization. The resulting string was used to initialize 128 MD simulations, which were carried out subject to the constraint (here implemented using a restraint potential) that the corresponding MD replicas are only allowed to move in hyperplanes perpendicular to the initial path. In addition, as described above, each MD replica was restrained to stay within ≃1Å of the initial string by using a one-sided restraint potential centered on 0.75Å. Temperature was maintained by use of Langevin Dynamics, as described for the biased simulations (see below). Restraint forces acting on the hyperplanes were averaged for 5 ns, and subsequently integrated to yield the free energy profiles.16 The FTS simulations required about 24 hours for each MD replica running on 32 2.1 AMD MagnyCours CPU cores.

2.5 Preparation of structures

The Xray crystal structure of Ca2+-bound CaM from Paramecium tetraurelia at 1.0Å resolution50 was obtained from the protein data bank (entry 1EXR). No Xray structures of monomeric Ca2+-free apoCaM have been solved. Schumacher et al. 53 reported Xray structures of a domain-swapped75 dimeric apoCam. As a consequence of domain-swapping in these structures, the C-terminal lobes of the two monomers are ‘intertwined’, such that separated monomers do not represent plausible monomeric solution structures. Therefore, we used the first structure from Xenopus laevis obtained by NMR49 (PDB entry 1DMO). Because the CaM sequences from the two organisms differ at 18 residue locations, the following mutations were made to the 1DMO structure: D2E, S17A, T70S, M71L, D78E, T79Q, I85L, R86I, R90K, K94R, Y99L, E119D, N129D, Q135H, V136I, Q143R, T146V, A147S (the first and last characters correspond to residue codes in PDB files 1DMO and 1EXR, respectively). Missing coordinates for atoms in the mutated residues were added using internal coordinate tables in CHARMM.76,77 The mutated residues occur mostly on the surface in the C-terminal domain (see Figure 1).

Ca2+ ions were deleted from the simulation structures. Because the conformational state of CaM is known to depend on the Ca2+ concentration,49,55 and because the binding of Ca2+ to CaM is cooperative,54 reproducing faithfully the dynamics of the Open (1EXR) conformer as well as transitions between the Open and Closed forms would probably require including Ca2+ ions in the simulation. However, the absence of Ca2+ should not affect the relative performance of different TMD methods used in the present study. For both conformers, all histidines were singly-protonated on the δ-nitrogen. The all-atom CHARMM22 topology and parameter files with the CMAP correction were used.78 The FACTS solvation model was employed to approximate the effect of solvent.79 Further details on the preparation of simulation structures and on the equilibration in the presence of restraints are provided in the supporting information.

The structures were equilibrated in the absence of restraints at 300K for 1ns using the Langevin Dynamics thermostat with the friction coefficient γ set to 1ps−1. During the equilibration, two types of conformational change were observed, which resulted in the deviation of the final equilibration structures from the initial structures by ~4.5Å. These changes are quantified in terms of RMSD in Table 1. In the Open structure, from which Ca2+ were deleted prior to simulation (see above), the EF hands in the Nterm domain (see Figure 1) undergo partial closure, which is consistent with the NMR study of Zhang et al. 49, who found that the removal of Ca2+ leads to the closure of EF-hand motifs within CaM. As qualitative validation, we repeated the equilibration simulation of the Open structure in explicit solvent, and observed a similar EF-hand closure. In the explicit water equilibration simulation, this conformational change occurred after 8ns of simulation, consistent with the fact that explicit solvation introduces friction that is typically absent in implicit solvent models (see e.g. Ref. 34 for a discussion). A similar, albeit less pronounced closure was also observed for the Cterm domain. The second type of conformational change observed involves the relative motion of the Nterm and Cterm domains about the linker loop L4 (see Figure 1b). This motion was observed mainly for the Closed structure, in which L4 is unwound, and is consistent with the flexible behavior of solution structures of apoCaM.49,80 To test whether EF-hand closure in the Nterm domain observed in the simulations was due to the removal of Ca2+, we repeated the equilibration simulation in explicit solvent, but with the Ca2+ ions bound to the structure. The EF-hands remained open for the entire 20ns of the simulation trajectory, suggesting strongly that removal of Ca2+ is the cause of the EF-hand collapse (see also Table 1). We note that these results appear to be in conflict with the conclusions of Vigil et al. 59, who proposed that the solution structure of the Nterm domain of Calmodulin exists predominantly in the closed conformation, but visits the open conformation frequently. The conclusions were based largely on the interpretation of ≃2.5-ns MD simulations with Xray scattering data. The radius of gyration in the MD simulations of the Nterm domain decreased from the initial value of ~13Å to 11.7Å–12Å, which the authors interpreted as EF-hand closure. In the present explicit water simulations, the radius of gyration of Nterm decreased over several nanoseconds from 12.9Å to ≃12.5Å, and remained at this value throughout the simulation. In comparison, the radius of gyration of Nterm in the Closed structure is ≃11.5Å. In the simulations performed here in the absence of Ca2+, the radius of gyration of Nterm decreased to ≃11.9. Thus, the present explicit water simulations support a Ca2+-loaded solution structure of Nterm that is more open than closed. This structure appears similar to the solution structure of Ca2+-loaded CaM derived from NMR by Chou et al. 57, whose measurements ruled out a model in which the closed apo conformation is partially populated in the Ca2+-bound state.

Table 1.

Conformational change in the CaM structures after equilibration without restraints as quantified by RMSD quoted in Å (see text).

| Domain | RMSD from X-ray 1EXR (Open) | RMSD from NMR 1DMO (Closed) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Open structure | ||

|

| ||

| heavy atoms | 4.5 | 12.4 |

| Nterm | 4.5 | 3.5 |

| Cterm | 3 | 4.5 |

|

| ||

| heavy atoms† | 4.5 | 13 |

| Nterm† | 4.5 | 3.5 |

| Cterm† | 2.2 | 5.4 |

|

| ||

| heavy atoms‡ | 4 | 13 |

| Nterm‡ | 3 | 4.7 |

| Cterm‡ | 2.2 | 5.4 |

|

| ||

| Closed structure | ||

|

| ||

| heavy atoms | 13.3 | 5 |

| Nterm | 5.5 | 2.7 |

| Cterm | 5.4 | 2.2 |

Equilibration calculation was performed in explicit solvent.

Equilibration calculation was performed in explicit solvent and with four Ca2+ ions bound to CaM.

The relatively large RMSDs between the initial and the equilibrated structures reported in Table 1 appear consistent with the conclusions in Refs. 49 and 50 for the Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound states, respectively, that each static structure represents a large number of conformations in solution. Further discussion is provided as supporting information.

2.6 Biased MD Simulations

The simulations performed in this study are summarized in Table 2. All of the biased simulations described below were initiated from the equilibrated structures. As the corresponding target structure we chose to use the starting energy-minimized Xray or NMR structure, as was done previously in TMD simulations of GroEL.4 With the use of the energy-minimized structures, all of the biasing methods except DSMD were able generate transition paths with final simulation structures within ~2Å of the target structures. The DSMD simulations converged to the target structures only when then equilibrated target structures were used. The reasons for this behavior are discussed in Results (Section 3.5). Using equilibrated (rather than energy-minimized) structures in TMD or RTMD simulations did not produce significant differences in the final RMSD to the target structures, the sequence of events, or in the increase in temperature when the thermostat was switched off. The temperature was kept at 300K using the Langevin Dynamics thermostat with γ =1ps−1. This value of γ was sufficiently high to keep the temperature of the system at 300K during the entire simulation, despite the fact that nonconservative work was performed on the system by the biasing forces. In the absence of the thermostat, the temperature at the end of the simulations increased by 60K–120K depending on the simulations (see Section 3). Additional details specific to each biasing method are given below.

Table 2.

Summary of MD simulations. TMD constraints and RTMD forces were applied only to the heavy atoms (1165 atoms). The number of corresponding simulations of a given type (performed identically but with different random seeds) is given in parentheses next to the simulation type. ρ(tmax) is averaged over identical simulations. The force constants kRTMD and kLRTMD are given in units of kcal/mol/Å2 (applicable to RTMD, SFTMD and LRTMD simulations). The force constant kSMD is given in units of kcal/mol/rad2 (applicable to DSMD simulations). For brevity, ‘O’ and ‘C’ denote the Open (1EXR) and Closed (1DMO) structures of CaM. The RMSD between the heavy atoms in the Open and Closed structures is ≃13Å. tmax corresponds to simulation duration. ρ(tmax) is the RMSD between the simulation and target structures at the end of simulation. Δρ0/Δt, Δδ0/Δt and Δε0/Δt represent the change per simulation timestep in the target values of the variables ρ, δ and ε, respectively (see Methods). Cluster size is given in residues (see Methods); n.a. indicates that the parameter is not applicable to the type of simulation; n.p. indicates that the simulation was not performed. In DSMDeq simulations, the equilibrated Xray and NMR structures were used as the target structures.

| Simulation (No. of traj.) | Δρ0/Δt(Å) *Δδ0/Δt(Å) ‡Δε0/Δt(rad.) | kRTMD * kLRTMD ‡ kSMD | Δrmax(Å) * cluster size ‡ torsions ¶PF(Å) | ρ(tmax)(Å) O→C/C→O | tmax (ns) O→C/C→O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| RTMD(1) | −0.00001 | 500 | n.a. | 1.03/0.93 | 1.5/1.5 |

| RTMD(10) | −0.00001 | 1000 | n.a. | 0.7/0.66 | 1.5/1.5 |

| RTMD(1) | −0.000005 | 1000 | n.a. | 0.7/0.67 | 3.0/3.0 |

| RTMD(1) | −0.00001 | 1500 | n.a. | 0.6/0.53 | 1.5/1.5 |

|

| |||||

| TMD§(10) | −0.00001 | n.a. | n.a. | 1.0/1.0 | 1.14/1.23 |

| TMD†§(1) | −0.00001 | n.a. | n.a. | 1.0/1.0 | 1.14/1.23 |

|

| |||||

| SFTMD(10) | −0.00001 | 1000 | 1 | 1.25/1.26 | 1.5/1.5 |

| SFTMD†(1) | −0.00001 | 1000 | 1 | 1.0/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

| SFTMD(1) | −0.00001 | 1000 | 5 | 0.7/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

| SFTMD(1) | −0.00001 | 1000 | 3 | 0.7/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

| SFTMD(1) | −0.00001 | 2000 | 1 | 0.94/1.05 | 1.5/1.5 |

|

| |||||

| LRTMD(10) | −0.00001 | 1000 | 6 | 0.8/0.5 | 1.5/1.35 |

| LRTMD†(1) | −0.00001 | 1000 | 6 | 0.45/0.95 | 1.5/1.5 |

| LRTMD†(1) | −0.00001 | 200 | 6 | 0.7/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

| LRTMD(1) | −0.00001 | 1000 | 10 | 0.45/0.5 | 1.5/1.5 |

|

| |||||

| DSMD(1) | −6.7×10−7 | 20000 | Φ,Ψ | 7.3/7.7 | 1.5/1.5 |

| DSMD(1) | −9.4×10−7 | 20000 | Φ, Ψ, χ1, χ2 | 4.7/6.25 | 1.5/1.5 |

| DSMD(1) | −9.6×10−7 | 40000 | Φ, Ψ, χ1 − χ5 | 3.8/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

|

| |||||

| DSMD eq(1) | −9.4×10−7 | 20000 | Φ, Ψ, χ1, χ2 | 4.4/5.6 | 1.5/1.5 |

| DSMD eq(1) | −9.6×10−7 | 40000 | Φ, Ψ χ1 − χ5 | 1.1/1.5 | 1.5/1.5 |

| DSMDeq†(1) | −9.6×10−7 | 40000 | Φ, Ψ, χ1 − χ5 | 5.0/1.9 | 1.5/1.5 |

|

| |||||

| BMD§(1) | −0.000333 | 1000 | n.a. | 2.5/2.9 | 6.0/1.5 |

| BMD†§(1) | −0.000333 | 3000 | n.a. | 1.85/2.11 | 1.5/1.5 |

| BMD§(1) | −0.000333 | 5000 | n.a. | 1.80/n.p. | 1.5/1.5 |

|

| |||||

| RPTMD§(1) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.0002 | 4.8/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

| RPTMD§(1) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.001 | 3.0/n.p. | 3.0/n.p. |

| RPTMD†§(1) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.0005 | 4.0/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

| RPTMD†§(1) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.001 | 3.4/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

| RPTMD†§(1) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.003 | 2.1/n.p. | 1.5/n.p. |

Simulation was performed with the thermostat turned off (see text).

Simulation results are shown in the supporting information.

Only for LRTMD simulations.

Only for DSMD simulations.

Only for RPTMD simulations (defined in the supporting information).

Constrained TMD simulations

The target structure was rotated to obtain a minimum-RMSD fit to the simulation structure at each simulation step. The maximum allowed RMSD between the simulation and target structures was decreased by 1 × 10−5Å per timestep (1fs). With the RMSD value of ≃13Å between the two energy-minimized structures and the prescribed final value of 1Å, the duration of each TMD simulation was ≃1,200,000 steps (1.2ns). Ten TMD simulations were performed in each direction (i.e. Open→Closed and Closed→Open) using different random seeds to initialize the thermostat.

Restrained TMD and scaled-force TMD simulations

Structures were initialized as described above for TMD simulations, and the same thermostat was used. The force constant kRTMD was in the range 500–2000 kcal/mol/Å2, which was sufficient to reduce the RMSD between the simulation structure and the target structure to ~1Å (see Figure 2a and Table 2). Using higher values for the force constant results in a smaller value for the RMSD, but does not change the computed paths qualitatively (e.g. the ‘large-scales-first’ order persists regardless of the value of the force constant). The maximum allowed RMSD between the simulation and target structures was decreased by 1 × 10−5Å per timestep, and the duration of each simulation was 1.5ns (in all but one RTMD simulation, in which Δρ0 = 5 × 10−6Å, and tmax=3ns; see Table 2). The maximum allowed RMSD between the simulation and target structures was held fixed after it reached zero (after ~1.3ns of simulation). The value of Δrmax in Eq. (6) was set to 1Å, 3Å and 5Å in different SFTMD simulations. For Δrmax=1Å, which corresponds to the greatest force reduction compared to regular RTMD, ten simulations with different random number seeds were performed in each direction.

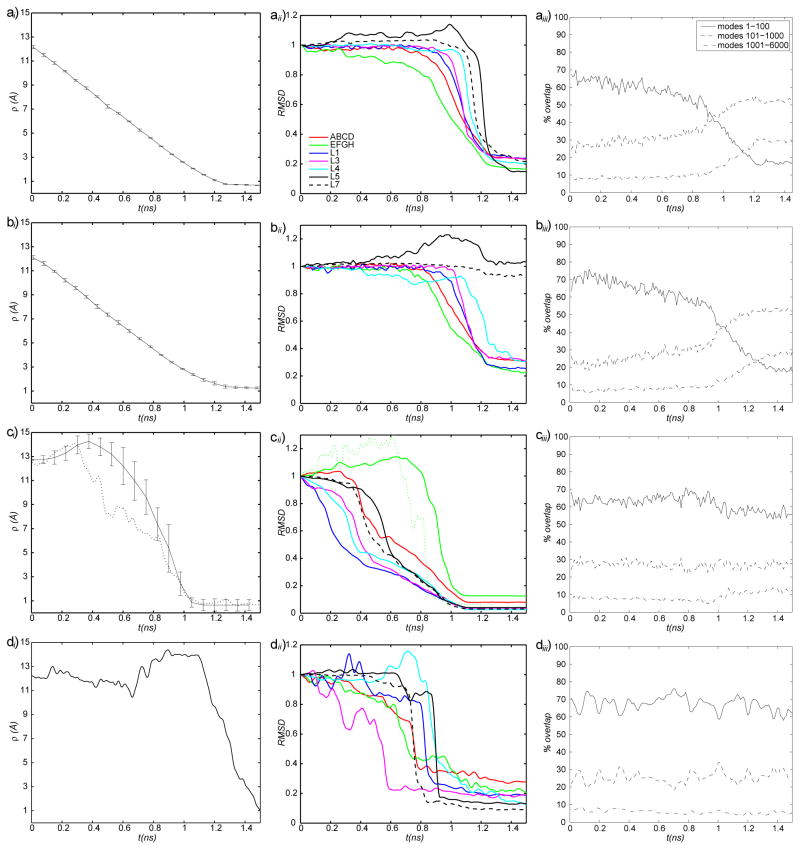

Figure 2.

ai), bi), ci), di) : Evolution of the heavy-atom RMSD between the simulation and target structures (ρ) in ai) RTMD simulations, bi) SFTMD simulations, ci) LRTMD simulations, di) DSMD simulations. Error bars represent standard deviations computed from all trajectories in the corresponding ensemble (results of one DSMD simulation are shown); —— : O→C; -------- : O→C, kLRTMD=200kcal/mol/Å2 (i only). aii), bii), cii), dii) : Evolution of the normalized heavy-atom RMSD computed for different CaM subdomains (see Figure 1). Curve labels are provided in aii). The dotted green curve in cii) corresponds to the portion of one trajectory that was chosen for subsequent free energy analysis. aii) RTMD O→C; bii) SFTMD O→C; cii) LRTMD O→C; dii) DSMD O→C; aiii), biii), ciii), diii) : Evolution of the overlap coefficients between the Normal Mode Vectors (NMV) and trajectory displacements in aiii) RTMD simulations, biii) SFTMD simulations, ciii) LRTMD simulations, diii) DSMD simulations. All curves correspond to the O→C direction. Curve labels are provided in aiii. NMV were computed using the Open structure. The modes corresponding to rigid body motions are not included (i.e. numbering starts from the first mode that has a positive frequency).

Locally-restrained TMD simulations

Each of the M sets of atoms from which the coordinates r̂n, for n ∈ {1, …, M} were computed, was composed of all non-hydrogen atoms in a cluster of six adjacent residues. The clusters were chosen to be rather small to demonstrate clearly the existence of a broad ensemble of paths, in which small-scale motions do not follow, but can even precede the large-scale ones. Each cluster except the first, overlaps with the preceding cluster by about 50%, such that, e.g., cluster 1 corresponds to residues 1–6 and cluster 2 corresponds to residues 4–9, etc. For the 148-residue sequence of CaM studied here, this scheme results in M=49 clusters, with cluster 49 spanning residues 145–148. The use of overlapping clusters is not required, but ensures that the global target conformation is attained at the end of the simulation. Each cluster is composed of approximately 45 atoms. The effect of increasing the cluster size to ten residues is discussed in Section 3.4.

Dihedral SMD simulations

Three sets of protein torsional angles were used. The first set contains all of the Φ and Ψ backbone torsion angles (294 in total), the second set also contains all of the χ1 and χ2 side chain torsion angles (489 in total), and the third set contains additional torsional angles sufficient to specify the conformation of the entire residue (590 in total; the restraints do not involve hydrogen atoms). For example, for Arginine, seven dihedral angles are included, Φ, Ψ, and χ1–χ5; for Phenylalanine, only angles up to χ2 are included because of the rigidity of the aromatic ring. Adding to the restraint set the ω dihedral angles, which specify the orientation of the peptide bonds (typically trans) did not make a significant difference in the results. A comprehensive list of the dihedral angles in the third set is provided in the Supporting Table S2. The squared sum of the dihedral angle difference ε is steered linearly from its initial value (≃0.8 for set 1, and ≃1.1 for sets 2 and 3) to zero over 1,200,000 simulation steps; the restraints are held at the final value for 300 additional steps, for a total of 1.5 ns of simulation at 1fs per step. Initially, target structures for the DSMD simulations were taken to be the corresponding energy-minimized Xray (1EXR) and NMR (1DMO) structures. Because the final structures from the corresponding simulations were quite far from the target structures, the DSMD simulations were repeated using equilibrated target structures, which resulted in a markedly closer approach to the target structures. The reasons for this behavior are discussed in Results (Section 3.5).

2.7 Normal Mode Analysis

Calculation of Normal Modes

Energy-minimized structures from Section 2.5 were subjected to additional minimization in the absence of restraints until the difference in the potential energy at two consecutive steps was less than 10−7. This required ~30000 iterations with the ABNR minimizer in CHARMM. Normal Mode Vectors (NMV) were computed for each structure with CHARMM, as described in Ref. 81, using 2nd-order central finite-difference approximation for second derivatives (the solvation model FACTS, which was employed in the NMA, currently does not provide analytical formulas for the second derivatives). The first six NM represent rigid body motion and were discarded. (The frequencies corresponding to the rigid body modes were scattered around zero with the mean deviation from zero of 0.066cm−1). The remaining 6810 modes were scaled to unit norm and stored for visualization and projection analysis (described below). The lowest non-rigid-body NM frequency was ≃1cm−1.

Normal Mode Projection Analysis

To quantify the extent of the large-scale displacement preference in the simulations, we project the displacements obtained from simulation trajectories onto the NMV computed for the Open and Closed conformations of CaM. This approach, which we call normal-mode projection analysis (NMPA), provides a quantitative measure of the dominant scales of motion. Since large-amplitude motions of biomolecules typically correspond to a low-frequency region of the normal mode spectrum,45,82 and smallest-amplitude modes (such as bond and angle vibrations) correspond to the highest-frequency region, one can infer the size of the dominant scale involved in the trajectory displacement by determining the frequency of the normal modes with which the trajectory displacement vector has the highest overlap.

To reduce computation time, trajectories obtained from TMD and RTMD calculations were sampled in 10ps time increments. To remove rigid-body motion, the trajectory frames were aligned such that any two consecutive structures have minimum mass-weighted RMSD. A normalized displacement vector was calculated between each pair of consecutive trajectory frames, and projected onto the NMV. The normalization was such that the squares of the projections (also called overlap or involvement coefficients82,83) add up to unity. We also tried computing the overlap coefficients after realigning all frames to minimize the mass-weighted RMSD to the corresponding energy-minimized structures; the results were qualitatively similar to those obtained using the first alignment method described.

3 Results

3.1 Overview

The form of the TMD equations (Section 2.1) suggests that the ‘large-scales-first’ phenomenon may be caused by the linear dependence of the atomic force magnitude on the length of the displacement of a given simulation atom from its position in the target structure (see Eq. (4)).

This possibility was investigated by comparing trajectories generated using the standard TMD and RTMD methods with those generated using a scaled-force RTMD method (Section 2.1), in which magnitudes of the forces acting on the simulation atoms are capped at a maximum value. By employing a projection of trajectory displacements onto normal mode vectors (see Section 2.7), we find that TMD and RTMD trajectories tend to follow low-frequency normal modes during the initial ~60% of the transition simulation. In the final portion of the trajectories, most of the motion occurs along higher-frequency modes, with the contribution of such modes increasing rapidly as the target structure is approached. During this stage, a large amount of non-reversible work is dissipated, which accounts for a large temperature increase in the simulations in which the thermostat was switched off. The dissipated work appears to arise from forcing the system to overcome barriers associated with the rearrangements of small loops. Simulation trajectories obtained using the SFTMD method revealed that the ‘large-scale-first’ feature was still present (see below). This result indicated that the direction of the applied forces has a larger influence on the evolution of TMD trajectories than the relative magnitudes of the forces. Two new biasing methods are used to generate additional transition paths. In both methods, the direction of the force vector is not related to global orientation. The first method, LRTMD, is a straightforward generalization of the original RTMD method, in which the bias potential corresponds to an RMS sum of conventional RTMD potentials based on small localized residue clusters in the protein (Section 2.2). In the second method, called dihedral (D)SMD, steering forces are applied to a prescribed set of dihedral angles (see Section 2.3). The ‘large-scales-first’ feature is absent from paths produced by both methods. A direct examination of the corresponding trajectories shows that the transitions in the small scales often (although not always) precede transitions in the large scales. An additional feature of the trajectory ensemble generated by the LRTMD method is that thermostatted trajectories initiated with different random seeds are substantially more diverse than those generated by the standard TMD/RTMD methods. The LRTMD path ensemble (used here to refer to a collection of trajectories rather a thermodynamic ensemble) is therefore broader in comparison to TMD/RTMD ensembles. It is likely that these trajectories correspond to a larger number of physical transition paths. We use the finite-temperature string method15,16,74 (see Section 2.4) to calculate the free energy profiles along a narrow transition tube associated with each path. The free energy barriers along the paths are found to be similar, suggesting that the transitions proceed via paths with similar probabilities.

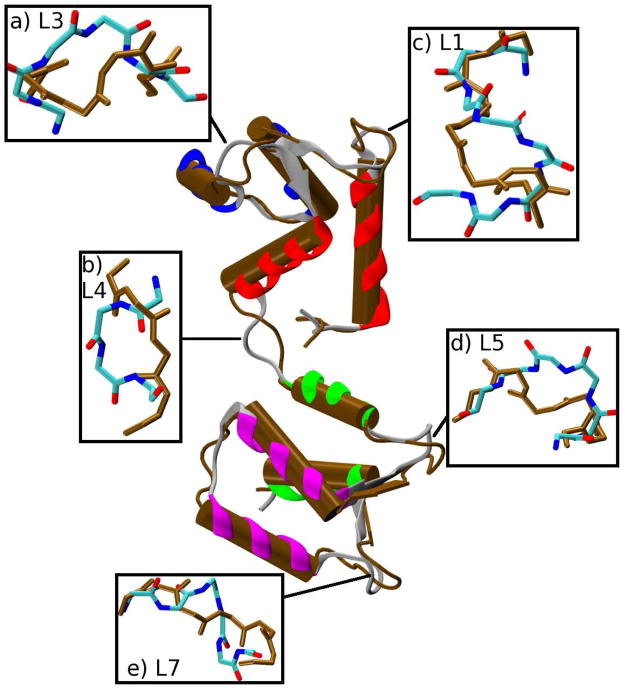

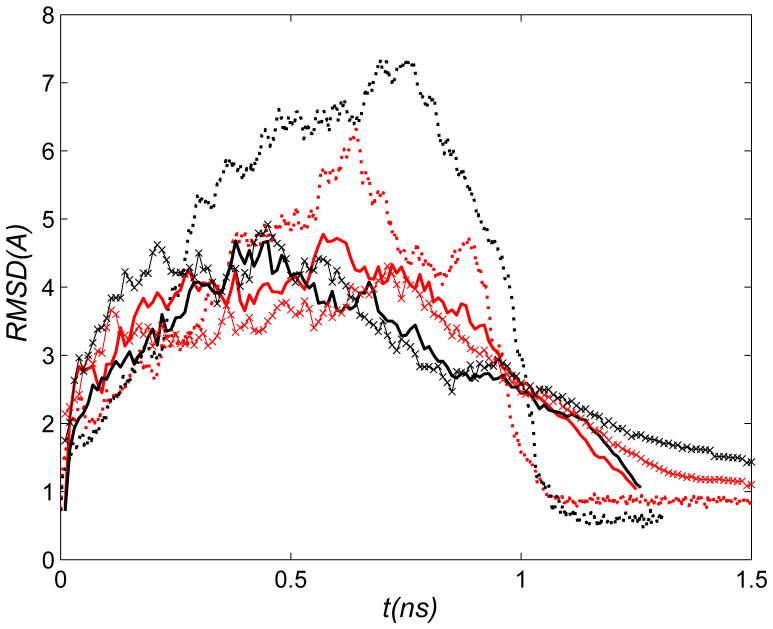

3.2 RTMD simulations

First, we discuss ensembles of transition paths generated with standard TMD and RTMD methods and quantify the ‘large-scales-first’ feature of the paths. We focus on twenty 1.5ns transition path trajectories that were generated with the RTMD method in the Open→Closed direction, as described in Methods and summarized in Table 2. Results are shown in the main text only for the RTMD simulations because trajectories generated using TMD show very similar behavior. Additional results are given in the supporting information. The evolution of the RMSD function ρ(t)≡ρ(r̂(t), Ar̂T) (defined in Eq. (3)) is shown in Figure 2ai for the RTMD simulations. The decrease in ρ is linear, in accordance with the driving protocol outlined in Section 2.6. The small error bars computed from the trajectory ensemble indicate that the actual RMSD ρ remains close to the target value ρ0 throughout the simulations. To examine the order of events in the transitions, seven elements in the CaM structure were selected (see Figs. 1 and 2aii), and the evolution of the normalized best-fit RMSDs between the atoms in each element was computed. The best-fit involved removal of the rigid-body motion, as required to determine whether a given element has reached its target conformation in the sense of RMSD. The normalization ensures that all curves start at unity. The transition of a given element appears as a decrease in the RMSD. Two of the elements are essentially the Nterm and Cterm domains of CaM excluding loops, namely helices A, B, C and D (Nterm) and helices E, F, G and H (Cterm) (the structure of CaM is shown in Figure 1 where the structural elements are indicated; they are defined in the supporting information). The remaining five elements are loops L1, L3–L5 and L7. Loops L2 and L6 are excluded to make the plots clearer. Figure 2aii indicates that the larger elements ABCD and EFGH undergo transition before the remaining loops. It is instructive to examine the simulation structure at t≃1ns for one of the simulations taken from the Open→Closed RTMD ensemble (Figure 3). At this time, the simulation structure is within ≃3Å RMSD of the target structure (relative to the starting value of 12.4Å). Consistent with the plots in Figure 2ai, Figure 3 confirms that the overall conformation of the simulation structure is close to the Closed target structure. The insets in Figure 3 show, however, that the conformation of all of the loops is very different from those in the target structure. The above results collectively illustrate what we call the ‘large-scales-first’ feature of RTMD and TMD simulations, namely the precedence of large-scale conformational motions (e.g. Nterm and Cterm) over small-scale ones (e.g. L1–L7). A more precise analysis can obtained by projecting the RTMD trajectory displacements onto the normal mode vectors (NMV) calculated from the energy-minimized endpoint structures, as described in Section 2.7. The time evolution of the overlap coefficients for the Open→Closed transition is shown in Figure 2aiii. The corresponding plot in the reverse direction is very similar and is not shown. Figure 2c shows that ~50–70% of the motion observed in the first 1ns of the RTMD simulations can be captured by the 100 lowest-frequency NMV computed from the Open conformation (out of 6810 vectors in total); 20–30% of the motion is accounted for by modes 101–1000, and the remaining 10% is captured only by the higher-frequency modes 1001–6000.

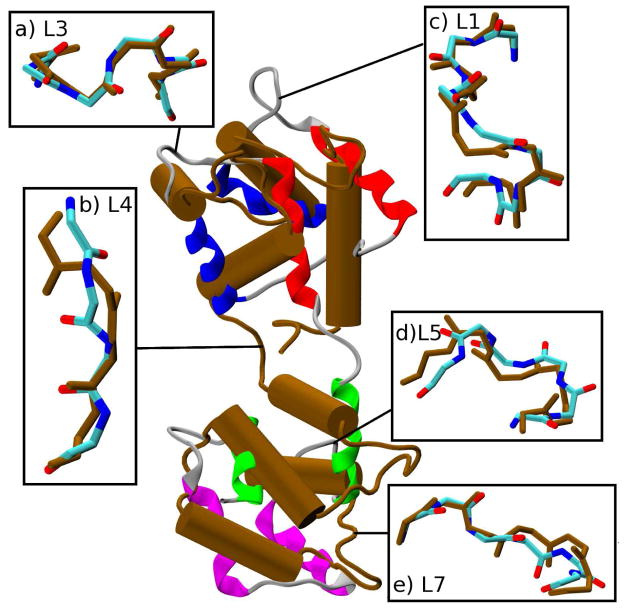

Figure 3.

Superposition of an instantaneous simulation structure from the Open→Closed RTMD ensemble at t = 1ns (colors) onto the target structure (brown). The regions separating the helices in the simulation structure are shown as gray ribbons. (The β-strand of EF-hand 2 [helices C and D in Figure 1] partially blocks the view of helix B, which remains intact in both structures). The insets provide an expanded overlay of loops L1–L7 (L2 and L6 are omitted).

In the portion of the simulations from 1ns to 1.5ns, as the simulated structure approaches the target, the low-frequency NMV from the starting structure provide a progressively worse description of the dynamics (~18% near the end). If the NMV computed from the target structure are used for comparison (see supporting information), the improvement in the overlap is modest (~26% near the end), which indicates that low-frequency modes from neither NMV set describe well the motions in the late stages of TMD simulations. The scalar products between the normalized NMV derived from the two structures are shown in the supporting information. The overlap between the ten lowest-frequency NMV is significantly lower (0.3–0.6) for the CaM conformations than observed for e.g. myosin46 (~0.8) because the two CaM conformations are less similar than the two myosin conformations (whose motor domains differ by ~3.5Å).

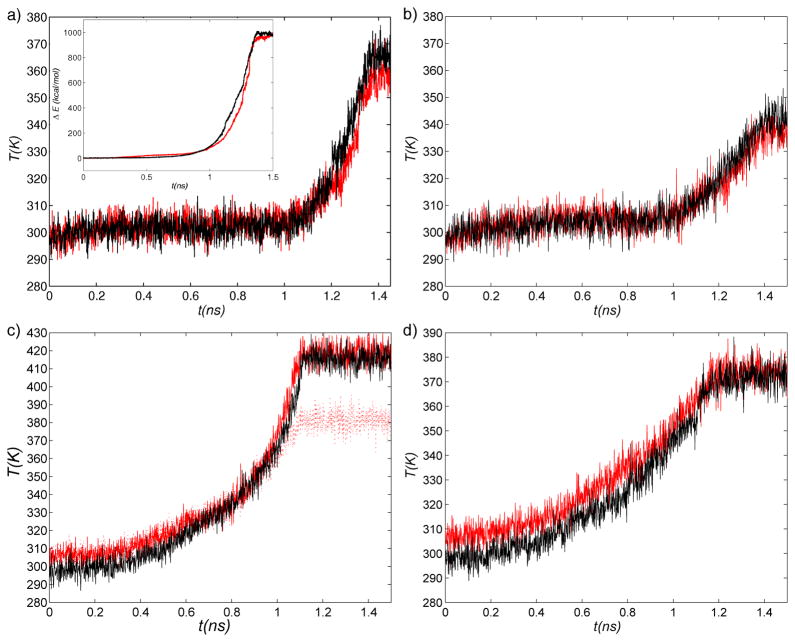

Projection of the displacements generated in the portion of the RTMD trajectories from 1ns to 1.5ns onto the remaining 6710 higher-frequency NMV computed from either conformation results in a progressively better overlap as the simulated structure approaches the target. Thus, the evolution of overlap coefficients in the projection analysis provides a quantitative measure of scale preference in transition paths computed by RTMD. Additional insight into the ‘large-scales-first’ feature of the transition is obtained by monitoring the kinetic temperature in the RTMD simulations performed in the absence of a thermostat (see Table 2). Figure Figure 4a shows that the temperature begins to increase rapidly around 1ns into the simulation, beginning at ~300K and reaching ~360K by the end of the simulation. The inset of Figure 4a shows that the increase of the total energy parallels closely the temperature increase, and reaches ≃1000kcal/mol at the end of the simulation (the kinetic and potential energies contribute approximately 500kcal/mol each to the total increase). The onset of the temperature increase coincides with the increase in the overlap between the trajectory displacements and the higher-frequency NMV (Figure 2aiii), suggesting that the temperature increases due to motions along high-frequency modes. In Normal Mode Analysis the potential energy in the vicinity of a local minimum is approximated to 2nd order as

Figure 4.

Temperature evolution in the absence of thermostatting in (a) RTMD simulations, (b) SFTMD simulations, (c) LRTMD simulations, and d) DSMD simulations. Red, solid: O→C; black, solid: C→O;red, dotted: O→C, kLRTMD=200kcal/mol/Å2 (c only). Inset in (a) shows the difference between the total energy of the simulation and the initial total energy. The energy is averaged over 0.1ns intervals to yield smoother plots.

| (9) |

where V is the eigenvector matrix of the Hessian (∇2E) evaluated at r̂0 (i.e. V contains the normal modes), N is the diagonal frequency matrix, and the atom coordinates r̂ have been scaled by mass ( ), and (·)t denotes matrix transpose. Eq. (9) implies that a displacement of Δr̂ along a given mode requires more energy for high frequency modes than for low-frequency modes. The analysis shows that transition paths generated by RTMD are expected to cross the lowest barriers first, and the highest barriers last. Qualitatively, by following normal modes in the order of increasing frequency, the transitions in RTMD occur along paths that encounter the least local resistance. In the next sections we employ the variants of the RTMD method described in Methods with the aim of removing the ‘large-scales-first’ feature characterized in this section. The above analysis applies equally to the constrained TMD algorithm (see Supporting Fig. S3).

3.3 Scaled-force TMD simulations

As discussed in Methods (Section 2.1), the magnitude of the biasing force acting on an atom in RTMD (or TMD) is proportional to the length of the displacement vector from the current atomic position to the target position. This relationship leads to a distribution of the forces illustrated in Figure 5a, in which the initial (Open) simulation structure is colored according to the total magnitude of the force acting on the corresponding residue. The force magnitude correlates with the approximate distance to the target (Closed) structure. To determine whether such a force distribution can, by itself, cause the observed ‘large-scales-first’ pattern of conformational change, we performed twenty simulations using the SFTMD method, in which the force force cutoff was Δrmax=1Å. Since this value is more than ten times smaller than the RMSD between the initial and the target structure (≃13Å), the level of force scaling will be large during most of the simulation, until the RMSD between the simulation target structures approaches Δrmax. (The high level of force scaling was chosen for a clearer comparison between the SFTMD and conventional RTMD trajectories.) The evolution of the average magnitude of the force acting on the simulation atoms is given in Figure 5b. As expected from the discussion, the average forces in SFTMD are generally lower than those in RTMD due to the force scaling. The atomic distributions of the biasing force magnitudes in the SFTMD method are shown in Figure 5c at t=100ps, 500ps, 1000ps, and 1100ps. For comparison, the distribution of the biasing forces in the RTMD method at t=500ps is also shown. During the first 500ps of the simulations, the atomic forces are approximately equal in magnitude for all atoms. As the simulated structure approached the target and the RMSD target ρ0 approaches Δrmax (e.g. t=1100ps), a nonuniform distribution of force magnitudes is observed, as expected from the discussion of the method (Section 2.1). Figure 2d shows that the final simulation structure approaches the target to within ≃1.25Å, averaged over the ten trajectories in each direction (see also Table 2). This value is slightly higher than the one obtained using standard RTMD (≃0.7Å). In addition, the standard deviations of the final RMSD are higher for the SFTMD case.

Figure 5.

a) Superposition of an instantaneous simulation structure taken from the Open→Closed RTMD ensemble at t = 500ps onto the target structure. The simulation structure is colored by the magnitude of the biasing force, and the target structure is in brown. The direction of the conformational change in the N-terminal EF-hands is indicated by black arrows. b) Evolution of the average force magnitude acting on the simulation atoms; red: RTMD simulation, O→C, kRTMD=1000 kcal/mol; green: SFTMD simulation, O→C, kRTMD=1000 kcal/mol; black: SFTMD simulation (force correction; see Section 2.1). c) Profiles of instantaneous biasing force acting on the simulation atoms; red: SFTMD at t=100ps; green: SFTMD at t=500; blue: SFTMD at t=1000ps; black: SFTMD at t=1100ps; cyan: RTMD at t=500ps. SFTMD were performed with Δrmax=1Å (see text).

The higher mean value and standard deviations are caused by the generally smaller forces in the SFTMD method as a result of force-limiting, despite the use of the same force constant to drive the transition (see Table 2). Although a closer approach to the target structure can be achieved by increasing the force constant, the present focus is on the ‘large-scales-first’ phenomenon, which is still present in the SFTMD trajectories. Figure 2bii is similar to Figure 2aii showing that the smaller loops undergo transition after the larger structures ABCD and EFGH. In addition, because the the forces on loop L5 are relatively small, due to the force-limiting, L5 generally does not reach the target conformation (although the overall RMSD to the target structure is around 1Å). Figure 2biii confirms that the transitions proceed initially along low-frequency modes, and end along high-frequency modes, as was observed for the TMD/RTMD simulations. Evolution of the temperature in an SFTMD simulation performed without the thermostat (Figure 4b) is similar to that obtained for the RTMD simulations, and implies that the simulation system moves along high-frequency/high-energy modes at the end of the simulation. The overall increase in the temperature (from 300K to 340K) is somewhat less than that for the corresponding RTMD simulation (360K) because of the smaller force magnitudes relative to RTMD (see above).

The similarities in the trajectory analysis results obtained for the RTMD and SFTMD simulations show that reducing the magnitudes of the forces applied to simulation atoms, as done in the SFTMD method, is not, by itself, sufficient to produce a significant difference in the trajectory ensembles. As mentioned in the Introduction, the methods have in common the global best-fit alignment procedure,64 which effectively determines the direction (as well as the magnitude) of the applied biasing forces. In the next section, we discuss ensembles of trajectories generated with the locally-restrained TMD method, LRTMD (Section 2.2), which does not use a global alignment. As a consequence, the early large scale motions are absent from these trajectories.

3.4 Locally-restrained TMD simulations

In the LRTMD simulation method, the single global RMSD potential of Eq. (2) is replaced by an RMS sum of a set of local potentials, as described in Section 2.2. Correspondingly, the global best-fit alignment is replaced by a set of alignments, each based on a subset of the structure. The evolution of the RMSD function ρ(computed a posteriori using a global best-fit alignment) shown in Figure 2ci for the LRTMD trajectory ensembles indicates that the final simulation structures are within ~0.6Å of the corresponding target structures. In contrast to the results of the previous simulations, the profiles of ρ are not generally monotonic, e.g. the average ρ for the Open→Closed transition increases in the first 400ps of the transition. The RMSD function ρ computed for the LRTMD trajectory ensemble is much higher in this region than that for the TMD or the RTMD ensembles. This behavior is expected since in RTMD (and TMD24) the bias potential acts to restrain ρ(t) to a monotonically decreasing ρ0, but in LRTMD the simulation value of ρ(t) is determined indirectly by enforcing a different restraint potential. The high standard deviations in Figure 2ci suggest that the corresponding trajectory ensemble has a higher variability than that obtained in TMD and RTMD. For a qualitative measure of the variability in the trajectory ensembles computed in this study, we define the average RMSD between all trajectory frames computed at a particular time t:

| (10) |

where N is the number of trajectories in the ensemble, and A(r̂i(t), r̂j(t)) is a best-fit rotation matrix. Profiles of ρ̄(t) for the ensembles generated with TMD, RTMD and LRTMD are compared in Figure 6. Consistently with the standard deviations in Figure 2ci, the LRTMD ensemble exhibits the highest variability over the first nanosecond; the variability is much smaller in the final 0.5ns portion of the trajectories because the simulation structures are essentially converged to the target structures (to within ≃1Å) after 1ns. This suggests that the ensemble of unbiased transition paths may be more meaningful than those found with standard TMD/RTMD simulations, i.e. the conformational transition can occur via a larger number of paths. The high variability also suggests that the conformational transitions in the small domains that define the LRTMD potential (Eq. (7)), are somewhat independent, and need not follow a particular order. Figure 2cii demonstrates that the precedence of large scales in the transition is no longer present. With the choice of six-residue clusters, transitions in the loops L1–L7 are seen to precede those in the EF-hand pairs ABCD and EFGH. A simulation structure extracted from the Open→Closed LRTMD trajectory ensemble at t=600ps is shown in Figure 7. Although the the global overlap with the target structure is quite poor (~11Å), the individual loops fit to the target structures well (RMSD of ≃1Å).

Figure 6.

Average RMSD between corresponding instantaneous structures computed for the TMD, RTMD, and LRTMD trajectory ensembles (see text).

TMD (O→C); —— TMD (C→O);

TMD (O→C); —— TMD (C→O);

RTMD (O→C); × RTMD (C→O);

RTMD (O→C); × RTMD (C→O);

LRTMD (O→C); -------- LRTMD (C→O);

LRTMD (O→C); -------- LRTMD (C→O);

Figure 7.

Superposition of an instantaneous simulation structure from the Open→Closed LRTMD ensemble at t = 600ps (colors) onto the target structure (brown). The insets provide an expanded overlay of loops L1–L7 (L2 and L6 are omitted).

The evolution of the overlap coefficients between the LRTMD trajectory displacements and the NMV are shown in Figure 2ciii. It is clear that during all stages of the transition, the trajectory motions are described well by the low frequency NMV. In particular, at the end of the conformational transition (1.5ns), the one hundred lowest-frequency NMV computed from the energy-minimized Closed (target) structure account for >70% of the trajectory motion. This behavior is different from that seen in the RTMD/TMD ensembles for the end of the transition, in which the overlap between the lowest-frequency motions falls to 20–30%, and the trajectory motions follow predominantly the remaining high-frequency NMV (Figs. 2aiii and 2biii).

To investigate the effect of the cluster size on the scale precedence in the transition, two LRTMD simulations were performed with the cluster size increased to ten adjacent residues per cluster (see Table 2). The evolution of the RMSD between the simulation and target structures is provided in Supporting Fig. S4; it is qualitatively similar to that described above for the LRTMD simulations with six-residue clusters. The overlap coefficients between the trajectory displacements and the NMV, shown in Figure 8, suggest a slight precedence of larger scales over smaller scales. Larger cluster sizes or more complex cluster composition were not tried. However, in view of the results, we expect that larger clusters will favor the precedence of large-scale motions, and smaller clusters will favor small-scale motions. This clearly raises a concern regarding the most physically meaningful sequence of motions (see Section 3.6)

Figure 8.

Evolution of the overlap coefficients between the NMV and trajectory displacements in the O→C LRTMD simulation with ten-residue clusters (see text). The labeling of traces is the same as in Figure 2ciii.

It was shown in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 that the increase in the high-frequency motions at the end of the trajectories is accompanied by a rather abrupt temperature increase (in the simulations with the thermostat switched off). Two LRTMD simulations using six-residue clusters were performed in the absence of a thermostat (Table 2). The time evolution of the temperature is shown in Figure 4c. In contrast to the RTMD case, the temperature increase is gradual, with a progressively higher slope, and begins near the start of simulation. This behavior appears to be consistent with the explanation that the temperature increase arises due to the crossing of barriers associated with small-scale motions, which, in the LRTMD cases, take place concomitantly with the large-scale motions.

In the RTMD simulations without thermostat, the temperature rises to ~360K, and in the corresponding LRTMD simulations, the final values are ~415K. These differences appear to be due to the use of different biasing potentials in RTMD and LRTMD (Eq. (2) vs. Eq. (7)) with the same forcing constant (k=1000 kcal/mol/Å2). Since the biasing potentials are qualitatively different, using the same force constant does not necessarily produce equivalent biasing conditions. As a test, we performed an additional LRTMD simulation in the Open→Closed direction with the force constant set to 200 kcal/mol/Å2 (Table 2). The final global best-fit RMSD between the simulation and target structures was ~0.7Å, similar to the main LRTMD case (see Figure 2ci), but the final temperature was substantially lower, at ~380K (see Figure 4c). Decreasing the force constant to k=40 kcal/mol/Å2 results in an even smaller temperature increase (~345K), but at the expense of increasing the RMSD between the final simulation and target structures to ~5Å. The results imply that it is difficult to decide based on the evolution of the temperature in the absence of a thermostat which biasing method results in smaller nonconservative work performed on the simulated system. Rather, the temperature evolution in all of the methods underscores the possibility that the transition paths are far from minimum free energy paths. Other methods, e.g. annealing in trajectory space32 or the string method15,16,74 may be used to equilibrate biased trajectories, although for large biomolecular systems such methods are expensive computationally. Biased MD simulations performed in this study (see Table 2 and supporting text and Fig. S6) suggest that obtaining unbiased trajectories using trajectory annealing32 would require extremely long simulation trajectories.

Each free energy calculation using the string method reported here required a hundred thousands CPU-core-hours to obtain converged results (see Section 3.6).

3.5 Dihedral SMD simulations

In the DSMD method, the biasing potential is based on the RMS difference between chosen dihedral angles in the simulation and target structures, and does not involve best-fitting. Three sets of dihedral angles were chosen for the simulations. The first set contained only the backbone angles Φ ad Ψ, the second set also contained the χ1 and χ2 angles, and the third set contained the angles χ1 − χ5 in addition to the backbone dihedral angles, which is sufficient to specify the conformation of all residues (see Section 2.6 and Supporting Table S2). For the initial DSMD simulations, the target structures were the energy-minimized Xray and NMR structures. As shown in Table 2, however, the RMSD between the final simulation structures and the target structures could not be reduced below ≃4Å; an improvement from 7.3Å to 4.7Å was observed for the Open→Closed simulation when dihedral set 2 was used instead of set 1, and a further improvement to 3.8Å resulted from using set 3. In the second set of DSMD simulations, equilibrated Xray and NMR structures were used as the target structures. When dihedral set 3 was used along with the equilibrated target structures, the RMSD between the final simulation and the target structures decreased to 1.1Å and 1.5Å for the Open→Closed and Closed→Open directions, respectively. (However, when the thermostat was switched off to monitor the increase in the temperature, the RMSD was again higher; see Table 2). The reasons for the dependence of the final RMSD on the choice of target structure are explored at the end of this section.

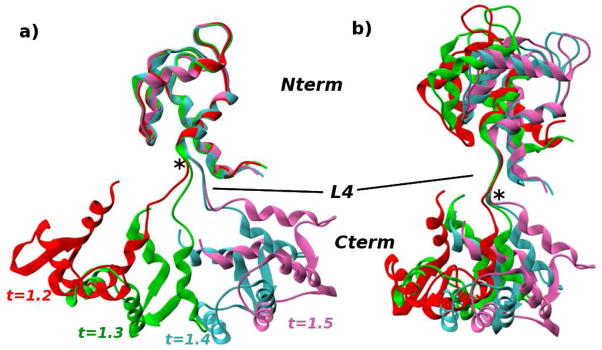

Figures 2di–2diii correspond to the DSMD simulations performed with dihedral set 3 and equilibrated target structures. The simulation behavior is qualitatively more similar to the LRTMD simulations than the RTMD simulations. The projection of trajectory displacements in Figure 2diii shows that the DSMD simulations do not have a length scale bias. (This plots are similar to Figs. 2ciii and 8, which correspond to the LRTMD simulations). Figure 2dii shows that changes in small loops are approximately in tune with the large-scale changes. The increase in the simulation temperature with the thermostat turned off is similar to that in the LRTMD simulations (Figure 4c and d), occurring gradually in the simulation. As in Figure 2ci (LRTMD case), the evolution of the RMSD function ρ is not necessarily monotonic (Figure 2di). An significant difference between the DSMD and the other simulations is in the behavior of the RMSD function in the Open→Closed trajectory. Although the target value of the biasing potential ε0 reaches zero at t=1.2 ns (see Methods), the RMSD between the simulation and the target structures at this time is ≃9Å. This behavior can be understood by considering four simulation snapshots corresponding to 1.2ns, 1.3ns, 1.4ns and 1.5ns, which are shown in Figure 9. The individual subdomains are very close to the corresponding target positions by t=1.2ns (e.g. Nterm in Figure 9a and linker loop L4 in Figure 9b), but the global alignment changes considerably between t=1.2ns and t=1.5ns. In particular, Figure 9 suggests that the structural differences are caused by small changes in the conformation of L4 (marked by asterisks in Figure 9). Although L4 is, essentially, in the target state (see also Figure 2dii), small conformational differences near the termini of L4 (res. 77 and 81; see Supporting Table S1 for subdomain definitions) are amplified into large differences in the relative positions of Nterm and Cterm, which are responsible for the large values of the RMSD (Figure 2di) at t=1.2ns. Additional 300ps of equilibration in the presence of the fixed restraint (from t=1.2ns to t=1.5ns) result in slow relative motion of the Nterm and Cterm subdomains, which reduces the Cartesian RMSD to 1.1Å by t=1.5ns. We examined the evolution of the dihedral angles in the period from t=1.2ns to t=1.5ns, and found that the backbone dihedral angles involving loop L4, were farther from their target values than most of the dihedrals in the forcing set, even though their RMSD sum ε(r̂, r̂T) in Eq. (8) did not change in the trajectory period. The findings indicate that, for highly flexible domains such as loop L4 in CaM, applying restraints in internal coordinates may not be an efficient way to enforce Cartesian positions. For such cases, the LRTMD method, which retains the locality of the restraint inherent in DSMD but employs Cartesian coordinates, appears to be a better-suited alternative. The causes of the higher RMSD between the final simulation and target structures that were observed with the energy-minimized target structures are discussed in the supporting information.

Figure 9.

Four simulation structures from the Open→Closed transition in CaM enforced by DSMD. The structures correspond to t=1.2ns, 1.3ns, 1.4ns, and 1.5ns. The superposition is performed using the Nterm subdomain in (a) and using the L4 loop in (b).

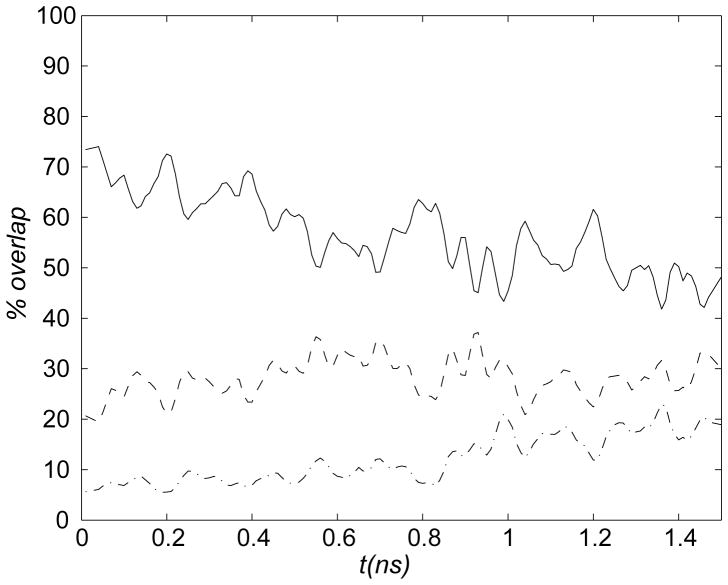

3.6 Free energy profiles along transition paths

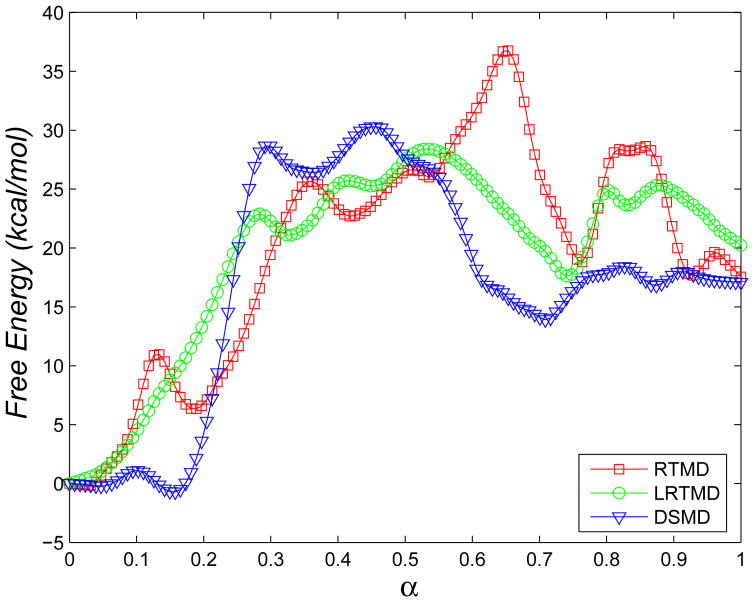

It was demonstrated in the preceding sections that the use of all biasing methods in the absence of a thermostat leads to a large increase in the temperature by the end of the simulations, indicating that a large amount of nonequilibrium work is performed on the simulation system. It was also shown in Section 3.4 (see Figure 4c) that the temperature increase is sensitive to the value of the force constant used in the biased dynamics. Since the values for the force constants cannot be compared directly for different biasing methods, the magnitude of the temperature increase in a simulation is not an accurate indicator of the quality of generated paths, as discussed above. To estimate the relative thermodynamic importance of the transition paths generated using the biasing methods presented in this study, we used the finite-temperature string method,15,16,74 as described in Section 2.4.

The FE profiles corresponding to transition paths generated by RTMD, LRTMD, and DSMD are compared in Figure 10. Although the FE calculations are not sufficiently long to obtain error estimates directly, we found that the FE difference between the endpoint states varies by less than 5 kcal/mol, depending on the transition path used. We therefore take this value as a rough measure of uncertainty in the FE values.

Figure 10.

Free energy profiles associated with a narrow transition tube corresponding to three initial paths (see text). The Open and Closed states correspond to α=0 and α=1, respectively.