Abstract

The transition of plant growth from vegetative to reproductive phases is one of the most important and dramatic events during the plant life cycle. In Arabidopsis thaliana, flowering promotion involves at least four genetically defined regulatory pathways, including the photoperiod-dependent, vernalization-dependent, gibberellin-dependent, and autonomous promotion pathways. Among these regulatory pathways, the vernalization-dependent and autonomous pathways are integrated by the expression of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), a negative regulator of flowering; however, the upstream regulation of this locus has not been fully understood. The SYP22 gene encodes a vacuolar SNARE protein that acts in vacuolar and endocytic trafficking pathways. Loss of SYP22 function was reported to lead to late flowering in A. thaliana plants, but the mechanism has remained completely unknown. In this study, we demonstrated that the late flowering phenotype of syp22 was due to elevated expression of FLC caused by impairment of the autonomous pathway. In addition, we investigated the DOC1/BIG pathway, which is also suggested to regulate vacuolar/endosomal trafficking. We found that elevated levels of FLC transcripts accumulated in the doc1-1 mutant, and that syp22 phenotypes were exaggerated with a double syp22 doc1-1 mutation. We further demonstrated that the elevated expression of FLC was suppressed by ara6-1, a mutation in the gene encoding plant-unique Rab GTPase involved in endosomal trafficking. Our results indicated that vacuolar and/or endocytic trafficking is involved in the FLC regulation of flowering time in A. thaliana.

Introduction

Membrane trafficking is a major regulatory system for protein transport in eukaryotic cells. Evolutionary conserved regulatory molecules play substantial roles in regulating the budding of transport vesicles from organelles and the fusion to target membranes. For example, SAR/ARF GTPases regulate budding processes, and RAB GTPases and soluble N-ethyl-maleimide sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) are key regulators of membrane tethering and fusion. The SNARE proteins contain a heptad-repeat called the SNARE motif; according to sequence similarities in SNARE motifs, they are classified into three Q-SNARE groups and one R-SNARE group. In most cases, Q-SNAREs localize on target organelle membranes, and R-SNAREs localize on transport carriers. Typically, four SNARE molecules (or three, in the complex that contains a SNAP25-type SNARE) form a tight, stable complex that promotes membrane fusion between transport carriers and target organelles [1]. It is widely accepted that the combination of four SNARE proteins, in coordination with a particular RAB GTPase, confers specificity in membrane fusion.

SYP22/VAM3/SGR3 is a Q-SNARE that acts in vacuolar and endocytic transport pathways; this gene was originally identified by functional complementation of the yeast vam3 mutant [2]. SYP22 localizes on the endosome/prevacuolar compartment (PVC) and the vacuolar membrane [2], [3], [4], [5]. There, SYP22 forms a complex with VTI11/ZIG, SYP5, and VAMP727 [6], [7], [8]. Loss-of-function SYP22 mutants exhibit a wide spectrum of phenotypes, including wavy leaves, semi-dwarfism, immature leaf vascular tissues, excessive differentiation of idioblasts, and late flowering [9], [10], [11]. These phenotypes were synergistically enhanced by a second mutation in the cognate SNARE gene, VAMP727; conversely, the overexpression of VAMP727 completely suppressed all syp22-1 phenotypes [6]. Thus, syp22-1 phenotypes appeared to result from defects in the endocytic and/or vacuolar transport pathways mediated by the SNARE complex of SYP22 and VAMP727, and not from defects in other unidentified SYP22 functions that are independent of membrane trafficking.

Most phenotypes of syp22 mutants, like wavy leaves, semi-dwarfism, and abnormal leaf vascular tissues, are thought to be caused by a defect in polar auxin transport; the syp22-4 mutation affects the polarized localization of PIN1, an efflux carrier of auxin, and the polar transport of auxin [10]. However, no studies have reported crosstalk between polar auxin transport and flowering regulation; this suggested that the late flowering phenotype of syp22 could be due to a defect in an uncharacterized mechanism that linked flowering regulation to vacuolar/endocytic trafficking. In this study, we examined the mechanism underlying the late flowering phenotype of syp22 to unveil this hidden link.

Upon floral induction, plants in the vegetative stage start producing floral meristems around the shoot apical meristem (SAM). In A. thaliana, the FT gene encodes an important floral inducer that is synthesized in leaves and transported to the SAM to induce expression of other floral inducers, including the SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS1 (SOC1). Expression of FT and SOC1 in A. thaliana is known to be regulated by at least four distinguishable genetic pathways: the photoperiodic-dependent, gibberellin-dependent, vernalization-dependent, and autonomous promotion pathways [12], [13]. The photoperiodic pathway modulates expression of FT in leaves in response to changes in the photoperiod [14]. The gibberellin pathway regulates flowering by controlling expression of SOC1 in the SAM [15]. The vernalization and autonomous pathways cooperatively modulate expression of FLC, which represses the expression of FT and SOC1 by directly interacting with the promoter regions of these genes [16]. Thus, FLC is a key integrator of the vernalization-dependent and autonomous promotion pathways.

To date, many putative nuclear factors have been identified that act in the autonomous pathway, including the RNA-binding or RNA-processing proteins, FCA, FPA, FLK, and FY, and chromatin modifiers, FVE and FLD [13]. However, no studies have reported the involvement of membrane trafficking in the regulation of FLC expression. Our results highlighted an unexpected link between the vacuolar SNARE and autonomous regulation of flowering in A. thaliana.

Results

syp22-1 was Defective in Determination of Floral Meristem Identity

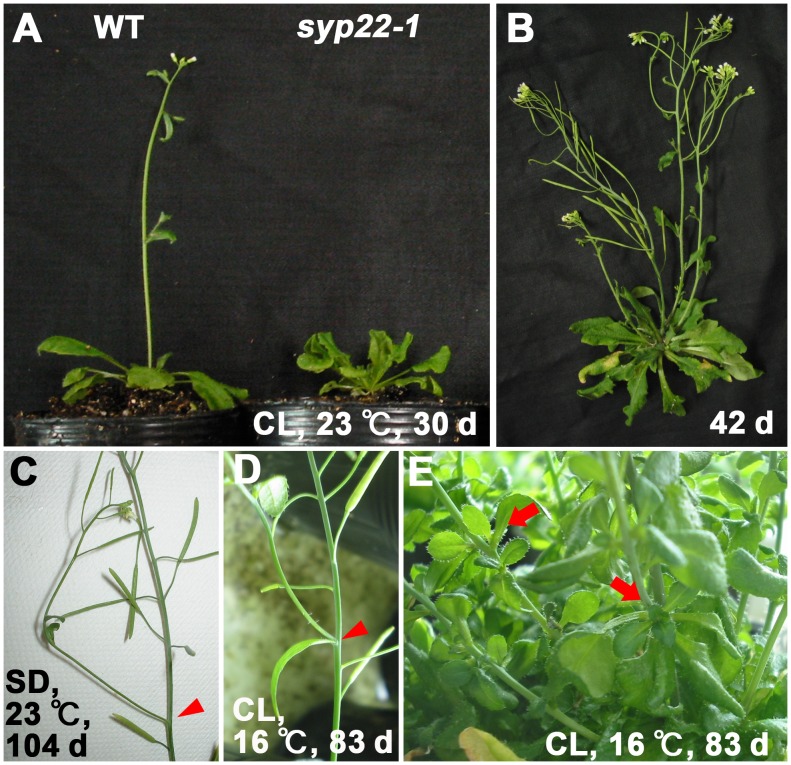

Previously, syp22-1 was reported to exhibit a broad range of phenotypes, including weak late flowering under continuous light (CL) (Fig. 1A) [9]. First, we investigated whether there was a functional link between SYP22 and floral meristem identity determination. Under normal growth conditions (CL, 23°C), determination of the floral meristem identity was not affected in syp22-1 (Fig. 1B). However, when grown under CL at 16°C, or under short-day conditions (SD: 8 h light and 16 h dark) at 23°C, the floral meristems of syp22-1 were frequently converted to inflorescence meristems (Fig. 1C, D), and aerial rosettes were occasionally produced (Fig. 1E). A similar phenotype has been reported for other late flowering mutants, including fld-2, a mutant defective in the autonomous pathway [17].

Figure 1. The syp22-1 mutant plant showed abnormal floral meristem identity.

(A) Wild-type (Columbia, left) and the syp22-1 mutant (right) were grown in continuous light (CL) at 23°C for 30 days; (B) The syp22-1 mutant is shown after 42 days. (C) syp22-1 mutant grown under short-day conditions (SD). (D, E) Phenotypes of syp22-1 grown under low temperature (16°C ) conditions. syp22-1 exhibited conversion of floral meristems to inflorescence meristems under SD or low-temperature conditions (C, D, arrowheads). Aerial rosettes were also observed when grown under low-temperature condition (E, arrows).

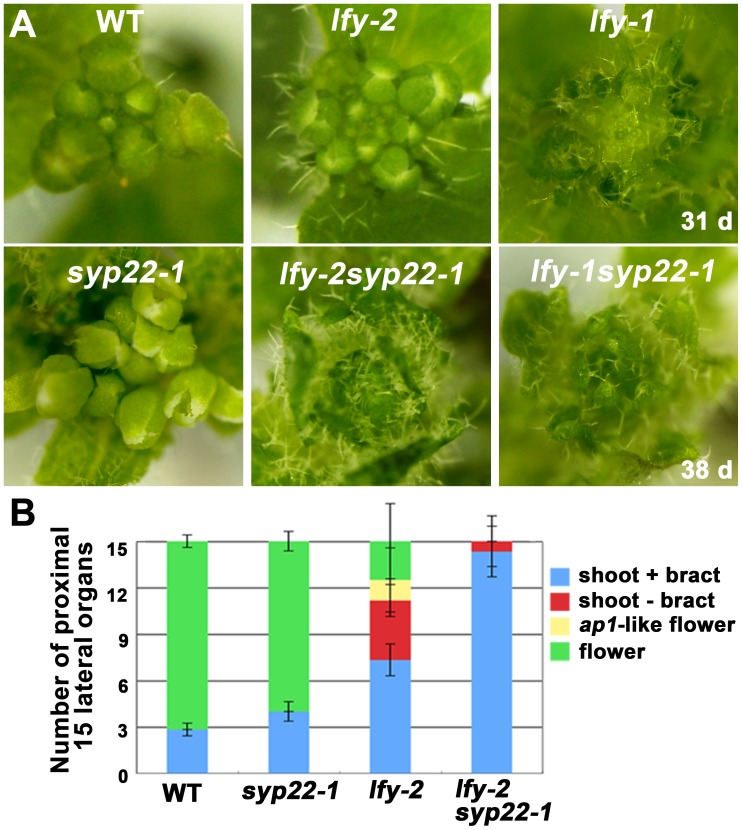

We then examined whether the abnormality in determination of floral meristem identity was related to the regulatory mechanism involving LEAFY (LFY), a key determinant of meristem identity. We generated double mutants between syp22-1 and either a weak (lfy-2) or null (lfy-1) allele. The syp22-1 mutation exaggerated the lfy-2 phenotype, which suggested that the two genes operated in a synergistic manner; the double mutant syp22-1 lfy-2 exhibited an indistinguishable phenotype from lfy-1, even when the double mutant plants were grown at 23°C in CL (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, the double mutant syp22-1 lfy-1 exhibited the same phenotype as lfy-1. Similar synergistic enhancement of weak alleles of lfy mutations was reported in double mutants of lfy combined with other late flowering mutations, ft, fd, and fld [17], [18], [19].

Figure 2. The syp22-1 mutation synergistically aggravated the lfy-2 mutation.

(A) Morphology around shoot apical meristems of wild type (left, top) and mutant plants. The lfy-2 syp22-1 double mutant (middle, bottom) exhibited a phenotype similar to that of lfy-1 (right, top). (B) Numbers of proximal 15 lateral organs in wild type and mutants. Results are presented as the means ±S.D. (n = 12 plants). The syp22-1 mutation alone did not markedly affect lateral organ identity, but it strongly promoted the transformation from flowers to inflorescences, when combined with the lfy-2 mutation.

We then analyzed the morphology of 15 proximal axillary organs that formed along the stems of wild-type and mutant plants. Compared with wild type and syp22-1, the lfy-2 plants generated a larger number of lateral shoots, with or without a bract, instead of flowers. This was also synergistically enhanced in the double mutant, syp22-1 lfy-2 (Fig. 2B, p<0.01, Student’s t-test). These results indicated that impairment of SYP22 function caused a deleterious effect on the determination of meristem identity through a pathway that involved LFY.

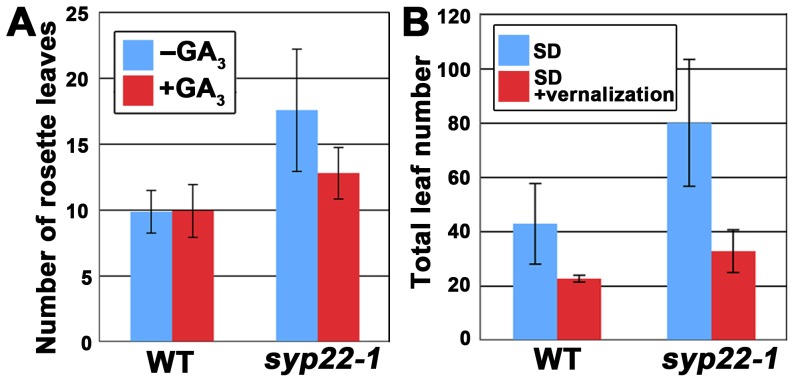

syp22-1 Responded Normally to Gibberellin and Vernalization

The four genetically distinguishable pathways that regulate the flowering time of A. thaliana are integrated by the expression of flowering pathway integrators, including the LFY gene [20]. To examine whether the syp22-1 mutant was defective in these regulatory pathways, we first tested the syp22-1 response to gibberellic acid (GA3). We found that GA3 treatment significantly promoted the flowering of syp22-1 (Fig. 3A and Fig. S1A, p<0.01, Student’s t-test); this indicated that syp22-1 retained responsiveness to gibberellin. Thus, the late flowering phenotype of syp22-1 did not seem to be caused by impairment in the gibberellin-dependent pathway.

Figure 3. The syp22-1 mutant responded normally to gibberellic acid, photoperiodic flowering induction, and vernalization treatment.

(A) The number of rosette leaves in wild type (WT) and syp22-1 mutants treated with (red) or without (blue) GA3. Results are presented as the means ±S.D. (n = 6 plants). (B) The total leaf numbers in wild type and syp22-1 under SD with (red) or without (blue) vernalization. Results are presented as the means ±S.D. (n = 17 plants for SD and n = 10 plants for SD+ vernalization). Flowering of syp22-1 was delayed in SD, which was suppressed by vernalization treatment (8 weeks at 4°C).

Next, we tested the syp22-1 response to the photoperiod. The wild-type plants (Columbia accession) used in this study flowered after generating 12.1±1.1 leaves under CL conditions and after generating 42.7±14.8 leaves under SD. On the other hand, the syp22-1 mutant generated a significantly larger number of leaves (79.8±23.4 leaves) when grown under SD than the wild type plants grown under SD (Fig. 3B and Fig. S1B, p<0.01, Student’s t-test). In contrast, the late flowering mutants defective in the photoperiod-dependent pathway are known to be insensitive to changes in photoperiod [21]; thus, the photoperiodic pathway did not seem to be markedly affected by the syp22-1 mutation.

We then demonstrated that syp22-1 responded normally to vernalization; vernalization treatment for 4 weeks at 4°C promoted flowering of syp22-1 under SD (Fig. 3B, p<0.01, Student’s t-test). These results indicated that SYP22 was involved in the regulation of flowering time through regulatory pathways other than the above three pathways. Furthermore, we confirmed that the late flowering phenotype could be rescued by introducing the GFP-SYP22 chimeric gene into the syp22-1 mutant, under the regulation of its own promoter (Fig. S2); this confirmed that the late flowering phenotype was due to a loss of function in SYP22.

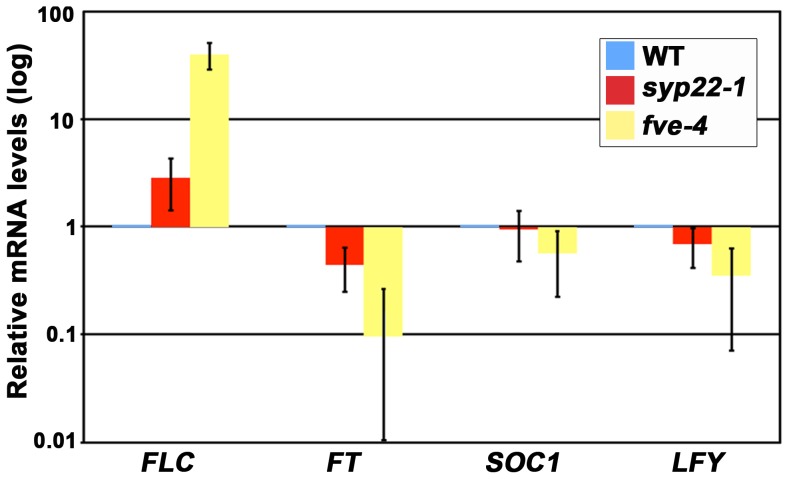

Expression Level of FLC was Elevated in syp22-1

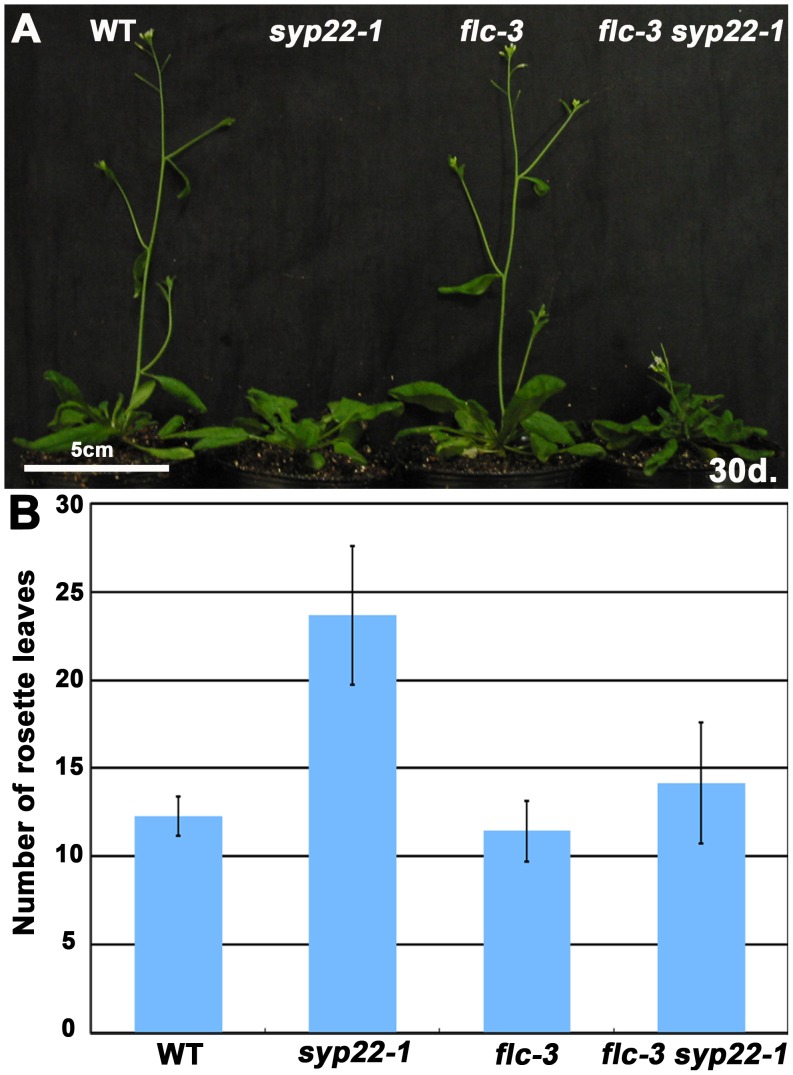

The results mentioned above strongly suggested that the late flowering of syp22-1 was caused by impairment in the last of a series of major regulatory pathways, the autonomous promotion pathway. FLC is a key regulator of the autonomous pathway. FLC encodes a MADS transcription factor that represses the expression of the floral pathway integrators, FT, SOC1, and LFY [13]. Thus, we reasoned that, if delayed flowering of syp22-1 was due to a defect in autonomous flowering promotion, then the mRNA level of FLC might be altered in this mutant. Accordingly, we examined the expression level of FLC and the floral pathway integrators in 14-day-old seedlings of the syp22-1 mutant by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). In syp22-1, FLC mRNA expression exceeded that of wild type by about three-fold (Fig. 4, p<0.01, Student’s t-test). Moreover, the mRNA expression of FT was significantly reduced compared to wild type (Fig. 4, p<0.01, Student’s t-test). In the syp22-1 mutant transformed with GFP-SYP22, accumulation of mRNA for FLC was comparable to that in wild type (Fig. S2C). These results strongly suggested that the late flowering phenotype of syp22-1 could be ascribed to elevated expression of FLC. We also confirmed this genetically; we reasoned that, if the elevated expression of FLC mRNA in syp22-1 had directly caused its late flowering phenotype, then the elimination of FLC activity should suppress this phenotype. To test this, we generated a double mutant of syp22-1 and flc-3, a null allele of flc, in a Columbia background. The endogenous expression of FLC was low in the Columbia accession, and flc-3 exhibited a phenotype similar to wild type when grown in CL (Fig. 5) [22]. On the other hand, as expected, the flc-3 syp22-1 double mutant generated a significantly smaller number of leaves (14.2±3.4 leaves) before flowering than syp22-1 (23.7±3.9 leaves, p<0.01, Student’s t-test) under CL conditions; thus, the double mutant was comparable to the wild type (12.3±1.1 leaves) and flc-3 (11.4±1.7 leaves) plants (Fig. 5). These results clearly demonstrated that the elevated level of FLC mRNA expression conferred a late flowering phenotype on syp22-1. Among the pleiotropic phenotypes of syp22-1, the flc-3 mutation suppressed only the late flowering phenotype; in contrast, other phenotypes, like wavy leaves and semi-dwarfism, were not remedied in the flc-3 syp22-1 double mutant (Fig. 5A). This indicated that the late flowering phenotype of syp22-1 was conferred by a mechanism distinct from that responsible for other phenotypes, which are most likely due to impairments in polar auxin transport.

Figure 4. Expression level of FLC was elevated in syp22-1 mutants.

The expression levels of FLC, FT, LFY, and SOC1 in 14-day-old wild type (WT), syp22-1, and fve-4 seedlings were examined by qRT-PCR. In syp22-1 plants, expression levels of FLC were elevated, which resulted in downregulation of downstream flowering pathway integrators. fve-4, an autonomous pathway mutant, was used as a control. Results are presented as means ±S.D. (n = 3–12).

Figure 5. The late flowering phenotype of syp22-1 was suppressed by flc-3.

(A) Wild type (WT), syp22-1, flc-3, and flc-3 syp22-1 plants were grown in CL for 30 days at 23°C. (B) Numbers of rosette leaves are shown for wild type (WT) and mutant plants grown under the same conditions as those in (A). Results are presented as means ±S.D. (n = 6 or 7 plants). The flc-3 mutation suppressed only the late flowering phenotype of the syp22-1 phenotypes.

Mutations in BIG, a Putative Regulator of Membrane Trafficking, and ARA6 also Altered FLC Expression

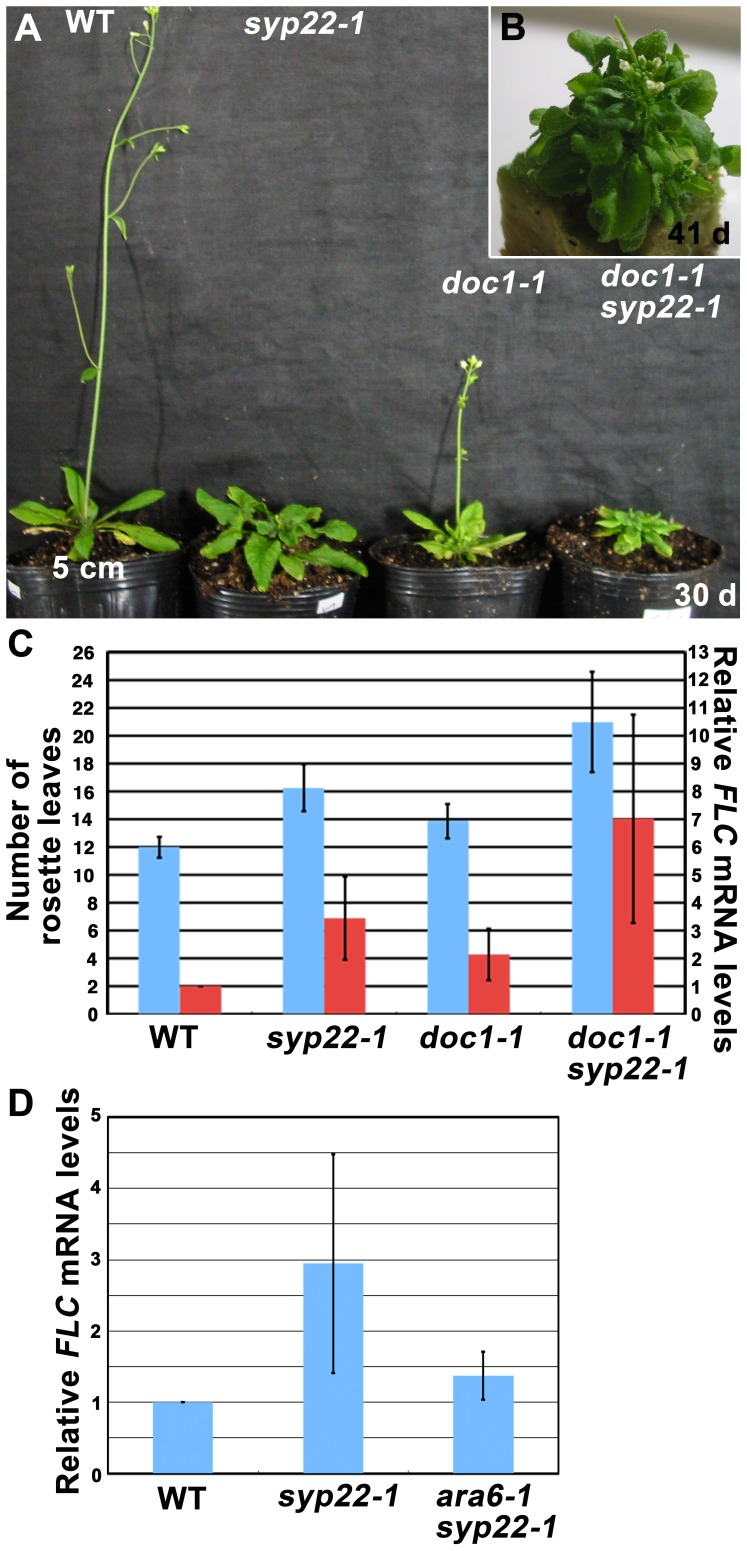

The results described above strongly suggested that vacuolar and/or endocytic trafficking pathways were involved in autonomous regulation of flowering. We then examined whether other membrane trafficking mutants exhibited a similar phenotype. We tested whether a genetic mutant of BIG, which encodes a Calossin-like protein, might also exhibit elevated FLC expression. BIG was originally identified as the gene responsible for the doc1 mutation [23]. BIG was also reported to be required for the auxin-mediated inhibition of endocytosis [24]. Furthermore, treatment with naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA), an inhibitor of polar auxin transport, altered subcellular localization of PIN1 in the doc1 mutant [23]. Based on these results, mutations in BIG were implicated in impairments of membrane trafficking pathways, including the endocytic and/or vacuolar transport pathways. Intriguingly, some mutant alleles of BIG have been also reported to exhibit the late flowering phenotype [25], [26]. These results implied that BIG was also involved in regulation of FLC expression. Among the big mutations, the allele that caused the most severe late flowering phenotype was doc1-1 [26]. Under our CL conditions, doc1-1 exhibited a late flowering phenotype (13.9±1.2 leaves, Fig. 6A, C) compared with wild type (12.0±0.8 leaves); this phenotype was similar to that of syp22-1 (16.3±1.7 leaves, Fig. 6A, C). We then generated a doc1-1 syp22-1 double mutant, which exhibited a more severe late flowering phenotype (21.0±3.6 leaves, Fig. 6A–C, p<0.01, Student’s t-test). A qRT-PCR analysis also indicated that the level of FLC mRNA expression was slightly increased in doc1-1, and this was enhanced in the double mutant, doc1-1 syp22-1 (Fig. 6C). Thus, BIG and SYP22 could be involved in the same regulatory pathway for FLC expression.

Figure 6. Effect of doc1-1 and ara6-1 mutations on expression of FLC in syp22-1.

(A) Wild type (WT), syp22-1, doc1-1, and doc1-1 syp22-1 plants were grown in CL for 30 days at 23°C. (B) doc1-1 syp22-1 plants grown in CL for 41 days at 23°C. (C) Numbers of rosette leaves (blue) and expression levels of FLC (red) are shown for wild type (WT), syp22-1, doc1-1, and doc1-1syp22-1 plants grown in CL at 23°C. Results are presented as means ±S.D. (n = 8 plants, 3 experiments of qRT-PCR). Results of qRT-PCR of FLC were normalized by the expression of TUA3. (D) The elevated expression level of FLC in syp22-1 was suppressed by the ara6-1 mutation. Expression levels of FLC in 14-day-old wild type (WT), syp22-1, and ara6-1syp22-1 seedlings were examined by qRT-PCR. Results are presented as means ±S.D. (n = 5 experiments).

We then examined the effect of a mutation in the other membrane trafficking regulator, ARA6, which is a plant-unique Rab GTPase involved in trafficking between multivesicular endosomes and the plasma membrane [27]. We have already reported that the ara6-1 mutation suppressed the late flowering phenotype of syp22-1. We examined whether the elevated expression level of FLC in syp22-1 is also suppressed by ara6-1, and found that FLC expression was significantly reduced in ara6-1 syp22-1 (Fig. 6D, p<0.05, Student’s t-test). This result also supports a possible link between membrane trafficking and flowering regulation.

Discussion

The syp22 mutants have exhibited pleiotropic phenotypes, including late flowering, semi-dwarfism, waved leaves, immature leaf vascular tissues, and excessive idioblast differentiation. All these phenotypes, except late flowering, have been thought to result from a misdistribution of the phytohormone, auxin [9], [10], [11]. In contrast, the reason that mutations in SYP22 engendered late flowering remained unclear. In the present study, we demonstrated that elevated expression of FLC in the syp22-1 mutant was a direct cause of the late flowering phenotype (Figs. 4 and 5). The syp22-1 mutant was capable of responding to vernalization treatment (Fig. 3D), which suggested that the syp22-1 mutation resulted in impairment in the autonomous promotion pathway. We further demonstrated that the expression level of FLC was elevated in another membrane trafficking mutant, doc1-1 (Fig. 6A–C), and that ara6-1, a mutation in the gene encoding a plant-unique Rab GTPase, suppressed elevated expression of FLC in syp22-1 (Fig. 6D). These results indicated that endocytic and/or vacuolar trafficking pathways were involved in the autonomous promotion of flowering in the Columbia accession of A. thaliana.

Our findings clearly indicated that the vacuolar SNARE, SYP22, was required for proper regulation of FLC, a key regulator of flowering time. This result may elucidate the recent finding that TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1), a homolog of FT, which is required for repression of the transition from the inflorescent meristem to the floral meristem, played a critical role in membrane trafficking to protein storage vacuoles (PSVs) [28]. Based on that finding, the authors proposed a novel function of the PSV: the storage of factors necessary for flowering and meristem maintenance. Other genetic studies indicated that TFL1 acted downstream of FVE and FCA, which are upstream regulators of FLC in the autonomous pathway [19], [29]. In addition, tfl1-1, a loss-of-function mutant of TFL1, exhibited an early flowering phenotype and reduced expression of FLC [30]. Those results suggest that TFL1 may also be involved in autonomous promotion of flowering. In our previous study, we found that the syp22 mutant also exhibited defects in the biogenesis of PSVs in A. thaliana [6]. Taken together, these results suggest the hypothesis that syp22-1 is defective in transport or storage of the flowering factors harbored in PSVs that affect autonomous promotion of flowering via modulation of FLC expression. Our present results clearly indicated that the flowering phenotype of syp22-1 was caused by a mechanism genetically separable from that responsible for other phenotypes, like semi-dwarfism and wavy leaves, which are most likely due to abnormal polar auxin transport. However, the predicted flowering regulators could be transported via the same trafficking pathway as the efflux carriers of auxin, because mutants of both SYP22 and BIG/DOC1 also exhibited abnormalities in polarized localization of the PIN1 protein [10], [23].

Another potential hypothesis is that SYP22 could be involved in transcriptional regulation of FLC via chromatin remodeling. In mammalian cells, an adaptor protein containing PH domain, PTB domain, and leucine zipper motif 1 (APPL1) has been identified as a RAB5 effector, which transmits a signal from the endosomes to the nucleus [31]. APPL1 was also shown to interact with the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex to regulate histone deacetylase (HDAC) 2 activity [32]. The level of FLC expression is tightly regulated, and this depends on the extent of chromatin modification; moreover, FVE and FLD were demonstrated to be components of the HDAC complex responsible for deacetylation of the FLC locus [33], [34]. If similar regulatory mechanisms of endosomal signaling followed by chromatin modification are conserved in plants, the mutation in SYP22 or BIG could affect these machineries, which could lead to elevation of FLC expression. Further study of molecular components that mediate endosomal signaling in plant cells would be required to investigate these hypotheses.

In conclusion, this study revealed a linkage between the fundamental cellular function of membrane trafficking and the higher ordered regulation of plant flowering. Future study of flowering from the viewpoint of organelle functions that are associated with membrane trafficking would elucidate our understanding of this regulatory system.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

A. thaliana (Columbia accession) seeds were sown on MS plates after sterilization. After a 2-day incubation at 4°C, plants were grown at 23°C under CL or SD (8 h light, 16 h dark). After 14 days (CL) or 21 days (SD) of incubation on plates, plants were transferred to the soil. For the vernalization treatment, plants were grown for 3 weeks at 23°C in SD, then incubated at 4°C for 8 weeks in SD.

The lfy-1 and lfy-2 mutants were obtained from ABRC; the fve-4 [33] and flc-3 mutants [22] were kindly provided by T. Araki (Kyoto Univ.). The doc1-1 mutant [35] was a kind gift from S. Sawa (Univ. of Tokyo). syp22-1/vam3-t and ara6-1syp22-1 were described elsewhere [27].

GA3 Treatment

Seeds were sown on MS plates and cultured for 14 days under CL conditions. Plants were transferred to the soil, and then sprayed with 20 µM GA3 (Wako) or water twice per week.

qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted from the aerial parts of 14-day-old plants with the RNAqueous-4 PCR kit (Ambion). Superscript III (Invitrogen) was used for reverse transcription. qRT-PCR was performed on a Light cycler 480 system (Roche) with specific sets of primers, including FLC: FLCf. 5′-gactgccctctccgtgacta-3′ and FLCr. 5′-ttctcaacaagcttcaacatgag-3′; FT: FTf. 5′-ggtggtgaagacctcaggaa-3′ and FTr. 5′-ggttgctaggacttggaacatc-3′; SOC1: SOC1f. 5′-aacaactcgaagcttctaaacgtaa-3′ and SOC1r. 5′-cctcgattgagcatgttcct-3′; LFY: LFYf. 5′-ttgatgctctctcccaagaag-3′ and LFYr. 5′-ttgacctgcgtcccagtaa-3′; TUA3: TUA3f. 5′-aagaagtctaagcttggttttaccat-3′ and TUA3r. 5′-agggaatgcgttgagagaac-3′. Primers and probes were selected according to the Universal Probe Library Assay Design Center (Roche, https://www.roche-applied-science.com/sis/rtpcr/upl/index.jsp?id=uplct_030000).

Accession Numbers

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative locus identifiers for the genes mentioned in this article are: At5g46860 (SYP22/VAM3/SGR3), At5g61850 (LFY), At1g65480 (FT), At2g45660 (SOC1), At5g10140 (FLC), At2g19520 (FVE), At3g54840 (ARA6), and At3g02260 (BIG/DOC1).

Supporting Information

The syp22-1 mutant responded normally to gibberellic acid and photoperiodic flowering induction. (A) The syp22-1 mutant was grown in CL for 30 days at 23°C, with (right) or without (left) GA3 treatment. (B) Wild-type (left) and syp22-1 mutant (right) grown under short-day conditions (SD, 8 h light/16 h dark) for 65 days at 23°C.

(TIF)

Phenotypes of syp22-1 were rescued by expressing GFP-SYP22. (A) Wild type (WT), syp22-1 (-), and two independent transgenic syp22-1 lines (#3-1 and #5-2) rescued with GFP-SYP22 expression under the regulation of the authentic promoter (proSYP22::GFP-SYP22) were grown under SD for 60 days at 23°C. (B) Numbers of rosette leaves are shown for wild type (WT), syp22-1, and syp22-1 rescued with GFP-SYP22 expression. Results are presented as means ±S.D. (n = 6 plants). (C) The expression levels of FLC in wild type (WT), syp22-1, and syp22-1 rescued with GFP-SYP22 were examined by qRT-PCR. Results of qRT-PCR of FLC were normalized by the expression of TUA3. Results are presented as means ±S.D. (n = 3).

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Abe (The University of Tokyo) for valuable comments, and T. Araki (Kyoto University), S. Sawa (Kumamoto University), and Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center for providing A. thaliana mutant plants.

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: KE T. Ueda. Performed the experiments: KE. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: T. Uemura. Wrote the paper: KE T. Ueda. Supervision of research: AN.

Funding Statement

This work is supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and the Targeted Proteins Research Program (TPRP) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (AN and TU), and a research fellowship for young scientists from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KE, 195010). This research was also partly supported by JST, PRESTO. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Saito C, Ueda T (2009) Chapter 4: functions of RAB and SNARE proteins in plant life. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 274: 183–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sato MH, Nakamura N, Ohsumi Y, Kouchi H, Kondo M, et al. (1997) The AtVAM3 encodes a syntaxin-related molecule implicated in the vacuolar assembly in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 272: 24530–24535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanderfoot AA, Kovaleva V, Zheng H, Raikhel NV (1999) The t-SNARE AtVAM3p resides on the prevacuolar compartment in Arabidopsis root cells. Plant Physiol 121: 929–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uemura T, Morita MT, Ebine K, Okatani Y, Yano D, et al. (2010) Vacuolar/pre-vacuolar compartment Qa-SNAREs VAM3/SYP22 and PEP12/SYP21 have interchangeable functions in Arabidopsis. Plant J 64: 864–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uemura T, Yoshimura SH, Takeyasu K, Sato MH (2002) Vacuolar membrane dynamics revealed by GFP-AtVam3 fusion protein. Genes Cells 7: 743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ebine K, Okatani Y, Uemura T, Goh T, Shoda K, et al. (2008) A SNARE complex unique to seed plants is required for protein storage vacuole biogenesis and seed development of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 20: 3006–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sanderfoot AA, Kovaleva V, Bassham DC, Raikhel NV (2001) Interactions between syntaxins identify at least five SNARE complexes within the Golgi/prevacuolar system of the Arabidopsis cell. Mol Biol Cell 12: 3733–3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yano D, Sato M, Saito C, Sato MH, Morita MT, et al. (2003) A SNARE complex containing SGR3/AtVAM3 and ZIG/VTI11 in gravity-sensing cells is important for Arabidopsis shoot gravitropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 8589–8594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ohtomo I, Ueda H, Shimada T, Nishiyama C, Komoto Y, et al. (2005) Identification of an allele of VAM3/SYP22 that confers a semi-dwarf phenotype in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 1358–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shirakawa M, Ueda H, Shimada T, Nishiyama C, Hara-Nishimura I (2009) Vacuolar SNAREs function in the formation of the leaf vascular network by regulating auxin distribution. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1319–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ueda H, Nishiyama C, Shimada T, Koumoto Y, Hayashi Y, et al. (2006) AtVAM3 is required for normal specification of idioblasts, myrosin cells. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 164–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fornara F, de Montaigu A, Coupland G (2010) SnapShot: Control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Cell 141: 550, 550 e551–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michaels SD (2009) Flowering time regulation produces much fruit. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thomas B (2006) Light signals and flowering. J Exp Bot 57: 3387–3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mutasa-Gottgens E, Hedden P (2009) Gibberellin as a factor in floral regulatory networks. J Exp Bot 60: 1979–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Helliwell CA, Wood CC, Robertson M, James Peacock W, Dennis ES (2006) The Arabidopsis FLC protein interacts directly in vivo with SOC1 and FT chromatin and is part of a high-molecular-weight protein complex. Plant J 46: 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chou ML, Yang CH (1998) FLD interacts with genes that affect different developmental phase transitions to regulate Arabidopsis shoot development. Plant J 15: 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abe M, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto S, Daimon Y, Yamaguchi A, et al. (2005) FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309: 1052–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ruiz-Garcia L, Madueno F, Wilkinson M, Haughn G, Salinas J, et al. (1997) Different roles of flowering-time genes in the activation of floral initiation genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 9: 1921–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henderson IR, Liu F, Drea S, Simpson GG, Dean C (2005) An allelic series reveals essential roles for FY in plant development in addition to flowering-time control. Development 132: 3597–3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levy YY, Dean C (1998) The transition to flowering. Plant Cell 10: 1973–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michaels SD, Amasino RM (1999) FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell 11: 949–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gil P, Dewey E, Friml J, Zhao Y, Snowden KC, et al. (2001) BIG: a calossin-like protein required for polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 15: 1985–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Paciorek T, Zazimalova E, Ruthardt N, Petrasek J, Stierhof YD, et al. (2005) Auxin inhibits endocytosis and promotes its own efflux from cells. Nature 435: 1251–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanyuka K, Praekelt U, Franklin KA, Billingham OE, Hooley R, et al. (2003) Mutations in the huge Arabidopsis gene BIG affect a range of hormone and light responses. Plant J 35: 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamaguchi N, Suzuki M, Fukaki H, Morita-Terao M, Tasaka M, et al. (2007) CRM1/BIG-mediated auxin action regulates Arabidopsis inflorescence development. Plant Cell Physiol 48: 1275–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ebine K, Fujimoto M, Okatani Y, Nishiyama T, Goh T, et al. (2011) A membrane trafficking pathway regulated by the plant-specific RAB GTPase ARA6. Nat Cell Biol 13: 853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sohn EJ, Rojas-Pierce M, Pan S, Carter C, Serrano-Mislata A, et al. (2007) The shoot meristem identity gene TFL1 is involved in flower development and trafficking to the protein storage vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 18801–18806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Page T, Macknight R, Yang CH, Dean C (1999) Genetic interactions of the Arabidopsis flowering time gene FCA, with genes regulating floral initiation. Plant J 17: 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Strasser B, Alvarez MJ, Califano A, Cerdan PD (2009) A complementary role for ELF3 and TFL1 in the regulation of flowering time by ambient temperature. Plant J 58: 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miaczynska M, Christoforidis S, Giner A, Shevchenko A, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, et al. (2004) APPL proteins link Rab5 to nuclear signal transduction via an endosomal compartment. Cell 116: 445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Banach-Orlowska M, Pilecka I, Torun A, Pyrzynska B, Miaczynska M (2009) Functional characterization of the interactions between endosomal adaptor protein APPL1 and the NuRD co-repressor complex. Biochem J 423: 389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ausin I, Alonso-Blanco C, Jarillo JA, Ruiz-Garcia L, Martinez-Zapater JM (2004) Regulation of flowering time by FVE, a retinoblastoma-associated protein. Nat Genet 36: 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He Y, Michaels SD, Amasino RM (2003) Regulation of flowering time by histone acetylation in Arabidopsis. Science 302: 1751–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li HM, Altschmied L, Chory J (1994) Arabidopsis mutants define downstream branches in the phototransduction pathway. Genes Dev 8: 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The syp22-1 mutant responded normally to gibberellic acid and photoperiodic flowering induction. (A) The syp22-1 mutant was grown in CL for 30 days at 23°C, with (right) or without (left) GA3 treatment. (B) Wild-type (left) and syp22-1 mutant (right) grown under short-day conditions (SD, 8 h light/16 h dark) for 65 days at 23°C.

(TIF)

Phenotypes of syp22-1 were rescued by expressing GFP-SYP22. (A) Wild type (WT), syp22-1 (-), and two independent transgenic syp22-1 lines (#3-1 and #5-2) rescued with GFP-SYP22 expression under the regulation of the authentic promoter (proSYP22::GFP-SYP22) were grown under SD for 60 days at 23°C. (B) Numbers of rosette leaves are shown for wild type (WT), syp22-1, and syp22-1 rescued with GFP-SYP22 expression. Results are presented as means ±S.D. (n = 6 plants). (C) The expression levels of FLC in wild type (WT), syp22-1, and syp22-1 rescued with GFP-SYP22 were examined by qRT-PCR. Results of qRT-PCR of FLC were normalized by the expression of TUA3. Results are presented as means ±S.D. (n = 3).

(TIF)